Abstract

Background:

Nonword repetition (NWR) involves the ability to perceive, store, recall and reproduce phonological sequences. These same abilities play a role in word and morpheme learning. Cross-linguistic studies of performance on NWR tasks, word learning, and morpheme learning yield patterns of increased performance on all three tasks as a function of age and language experience. These results are consistent with the idea that there may be universal information-processing mechanisms supporting language learning. Because bilingual children’s language experience is divided across two languages, studying performance in two languages on NWR could inform one’s understanding of the relationship between information processing and language learning.

Aims:

The primary aims of this study were to compare bilingual language learners’ recall of Spanish-like and English-like items on NWR tasks and to assess the relationships between performance on NWR, semantics, and morphology tasks.

Methods & Procedures:

Sixty-two Hispanic children exposed to English and Spanish were recruited from schools in central Texas, USA. Their parents reported on the children’s input and output in both languages. The children completed NWR tasks and short tests of semantics and morphosyntax in both languages. Mixed-model analysis of variance was used to explore direct effects and interactions between the variables of nonword length, language experience, language outcome measures, and cumulative exposure on NWR performance.

Outcomes & Results:

Children produced the Spanish-like nonwords more accurately than the English-like nonwords. NWR performance was significantly correlated to cumulative language experience in both English and Spanish. There were also significant correlations between NWR and morphosyntax but not semantics.

Conclusions & Implications:

Language knowledge appears to play a role in the task of NWR. The relationship between performance on morphosyntax and NWR tasks indicates children rely on similar language-learning mechanisms to mediate these tasks. More exposure to Spanish may increase abilities to repeat longer nonwords. This knowledge may shift across levels of bilingualism. Further research is needed to understand this relationship, as it is likely to have implications for language teaching or intervention for children with language impairments.

Keywords: nonword repetition, bilingual, Spanish

Introduction

Nonword repetition (NWR) is often used to investigate the phonological short-term memory mechanisms underlying language learning in children. In this task, children repeat increasingly longer nonwords comprised of syllables that conform to the phonotactic constraints of the target language (for an in-depth discussion of item development, see Gathercole and Baddeley 1989, and Gathercole et al. 1992). Immediate recall of unmeaningful phonological sequences depends heavily on children’s ability to perceive, store, recall, and reproduce accurately strings of phonological sequences (Baddeley 2003). NWR is of special interest to researchers who study language development and disorders because the skills necessary to repeat nonwords play an important role in learning new words and morphemes. Numerous studies show that performance on NWR tasks predicts vocabulary development (Adams and Gathercole 1995, Roy and Chiat 2004) and, to a lesser degree, syntactic development (Graf Estes et al. 2007, Sahlén et al. 1999).

Nonword difficulty increases as a function of nonword length in syllables, across a number of languages including Italian (Bortolini et al. 2006, D’Odorico et al. 2007), Spanish (Girbau and Schwartz 2007), Swedish (Radeborg et al. 2006, Reuterskiöld-Wagner et al. 2005), Dutch (Gijsel et al. 2006), Greek (Masoura and Gathercole 2005), French (Klein et al. 2006), Portuguese (Santos et al. 2006), and Cantonese (Stokes et al. 2006). In these studies children’s ability to repeat nonwords accurately increases with age and vocabulary size. These results suggest that the skills required to repeat nonwords are universal and may support language learning.

Underlying mechanisms in NWR

The underlying mechanisms employed to repeat nonwords include phonological processing (Bowey 1996, 1997), articulation skills, speech perception (Frisch et al. 2000), and phonological short-term memory (Gathercole et al. 1992, Masoura and Gathercole 2005, Gathercole 2006). Baddeley’s (2003) model of working memory provides a useful framework for thinking about the phonological short-term memory mechanisms that contribute to NWR. The most recent model includes three important components of fluid memory. Two slave systems, the phonological loop and the visual-spatial sketchpad, are controlled by a central executive. The phonological loop holds auditory information for a brief period of time and includes a method of rehearsal to retain that information for longer periods. The central executive controls the use of the slave components through attention and inhibition. This model of working memory also includes crystallized memory systems that store long-term information including language knowledge. The phonological loop interacts with long-term language knowledge in a reciprocal relationship. Repeating nonwords uses both of these. In the phonological loop or phonological working memory, sound segments are held and rehearsed to facilitate repetition. Long-term language knowledge is activated when sound segments resemble lexical representations. Phonotactic rules of a language may additionally mediate the repetition of nonwords because retention and recall processes rely, in part, on rapid activation of well-specified phonotactic knowledge.

Children who are actively engaged in learning two languages might develop particularly strong phonological representation, storage, and retrieval systems as a by-product of requirements for bilingual language learning and use (Bialystok et al. 2003). On the other hand, because input in each language is necessarily distributed across their languages, they may develop relatively weaker representations in both their languages (Gollan et al. 1997). It is also possible that bilingual language development results in unique relationships between the cognitive processes underlying language learning (such as phonological short-term memory) and levels of language knowledge. This study was designed to explore the relationships between language experience and phonological memory skills and language knowledge in children with varying language experiences.

Role of experience in non word repetition

The degree to which NWR interacts with long-term language knowledge is a function of the word-likeness of the nonwords (Dollaghan et al. 1995) and the extent to which they conform to the phonotactic rules of the target language (Archibald and Gathercole 2006, Gathercole et al. 1999). Word-likeness and phonotactic probability are related because words with high phonotactic probability are judged to be more word-like (Frisch et al. 2000). High probability nonwords are repeated more accurately than low probability nonwords demonstrating the role of frequency in NWR task performance. But this frequency effect is usually larger for children with smaller vocabularies and for children with language impairment (Munson et al. 2005). For example, high-word-like (i.e., perplisteronk and glistering) and/or high-probability phoneme sequences within nonwords might invite a greater role for prior language knowledge in a NWR task. In contrast, low-word-like nonwords (i.e., teivak and naib) and nonwords containing low-probability phoneme sequences sound less like real words and invite a lesser role for prior language knowledge. Thus, children’s language knowledge and experience with language(s) can influence their performance on this seemingly non-linguistic task (Edwards et al. 2004, Munson et al. 2005, Frisch et al. 2000).

Phonotactic properties of English and Spanish

Performance on NWR tasks seems to be influenced by the specific phonological and phonotactic structure of the particular language a child is learning. Spanish and English, for example, differ in the number of sounds available to produce contrasting phonotactic structures. Standard American Spanish uses five vowels and 20 consonants but English uses 13 vowels and 24 consonants (Hammond 2001). Thus, at the phonological level there are more possibilities for contrasting sound combinations in English than in Spanish. Furthermore, the child’s language environment provides examples of the word-shapes and phonological patterns of that language in varying degrees. Phonotactic rules govern the possible number of syllables, consonant clusters, stress patterns, and phoneme sequences, and these rules influence the likely arrangement of phonemes in words. As summarized in Table 1, Spanish has more multi-syllable words than does English (Shriberg and Kent 1982, Navarro 1968).

Table 1.

Word frequencies in English and Spanish

| One-syllable words | Two-syllable words | Three-syllable words | Four-syllable words | Five-syllable words | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | 76.92 | 17.05 | 4.55 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Spanish | 7.54 | 25.83 | 19.67 | 6.87 | 1.42 |

Note: n.a., Not available.

These phonological and phonotactic differences in Spanish and English influence rate of acquisition of the sound system in each language. Children learning Spanish master the sounds of the language relatively earlier than do children learning English. In English, fricatives, affricates, liquids, and velars are later developing sounds and are mastered between ages 4 and 5 years (Porter and Hodson 2001). In contrast, children learning Spanish produce most Spanish consonants and sound combinations accurately by age 4 (Goldstein and Iglesias 1996). These differences may be attributed to the number of sounds to be learned and the possible contrasts to be produced. English gains phonotactic complexity by adding syllable final consonants and consonant sequences. Spanish gains phonotactic complexity by adding syllables and consonant vowel sequences.

Differences in the phontactic rules of the English and Spanish languages affect NWR performance. For example, children learning languages in which multi-syllable words are frequent such as Portuguese (Santos and Bueno 2003) and Greek (Masoura and Gathercole 1999) appear to be better at producing longer nonwords (up to five- and six-syllable nonwords, respectively). Because longer words are more frequent in Spanish than English, we would expect that children exposed to Spanish would be able to produce longer nonwords.

Morphosyntactic influences

Morphosyntactic structure may also mediate linguistic tasks and influence performance on NWR across languages. Vitevitch and Stamer (2006) found that in contrast to English, Spanish words from sparse neighbourhoods (i.e., words with few similar sounding words) are produced more quickly than Spanish words from dense neighbourhoods (i.e., words with many similar sounding words). This result contrasts with findings in studies of English that words from dense neighbourhoods were named more quickly than words from sparse neighbourhoods (Gordon and Dell 2001, Vitevitch 2002). Vitevitch and Stamer hypothesized that the opposing patterns in English and Spanish word production rates might be the result of inherent differences between the two languages. Because Spanish is highly inflected in contrast to English, similar Spanish words (e.g., bonita and bonito) may compete more due to their phonological and semantic similarity than words in English (e.g., cat and can) which are phonologically, but not semantically similar.

Vocabulary exposure

Most studies of the relationship between NWR and language focus on vocabulary, although there are some studies that explore NWR and other language domains. The relationship between NWR and vocabulary learning appears to be mediated by language learning experience as indexed by age. Adams and Gathercole (1995) observed weak-to-moderate correlations between NWR and performance on the British Picture Vocabulary Scale (Dunn and Dunn 1982) of 0.21–0.42 for younger and older 3-year-olds, respectively. This is similar to the correlation between receptive vocabulary and NWR (0.42) reported by Roy and Chiat (2004) for children ranging from 2 to 4 years of age. Higher correlations between NWR and receptive vocabulary were found for children between the ages of4 (0.56), 5 (0.52), and 6 (0.56) years (Gathercole et al. 1992). By age 8 the correlation between the two tasks was reported to be 0.28. These findings suggest that phonological working memory plays a larger role in the vocabulary learning process when children have less knowledge. But, the demands on phonological working memory may diminish once children have a larger linguistic base and more practice with vocabulary learning.

Similar patterns of language knowledge and NWR accuracy have been observed for second language learners. For 10-year-old Greek-speaking children, the correlation between Greek NWR and receptive vocabulary was lower (0.33) than the relationship for English nonwords and second language vocabulary (0.66) (Masoura and Gathercole 2005). In a study of 7th-grade Cantonese speakers learning English, Cheung (1996) found that the relationship between NWR and vocabulary in English held for those whose English vocabulary size was below the group mean.

Language experiences

The languages children are exposed to and their varying proficiency in multiple languages may influence their NWR performance. Evidence for this comes from three studies. In one study, Masoura and Gathercole (1999) found that Greek children learning English as a second language were more accurate repeating nonwords in their native language (Greek) than in the second language (English) in two- to five-syllable nonwords. Performance on NWR was mediated by language experiences. In this case, Greek, the language with the most experience and proficiency was the most accurate. In contrast, the children had less exposure to and were less proficient in English resulting in lower NWR scores. Likewise, Thorn and Gathercole (1999) found that English monolinguals scored lower on French nonwords compared to the simultaneous French-English bilingual children who scored similarly in both languages. The patterns of age and language contributions to the nonword scores differed by language. While age and vocabulary knowledge contributed a total of 20% of the variance in the English nonword scores, 38% of the French nonword scores were accounted for by vocabulary knowledge alone without contribution by age. Similarly, Kohnert et al. (2006) compared performance on a NWR task in three groups of children: typical Spanish–English sequential bilinguals, typical monolingual English speakers, and monolingual English speakers with specific language impairments (SLI). The bilingual Spanish–English children produced English-like nonwords less accurately than typically achieving monolingual English children but more accurately than English only children with SLI. It may be that respective English proficiency impacted the bilingual children’s ability to repeat nonwords. Also, using English nonwords only did not fully portray the bilinguals children’s NWR skills

Nonword repetition and other language measures

Some studies have examined the relationship between performance on NWR measures and other language measures. Ebert et al. (2008) did not find a relationship between Spanish NWR and the Preschool Language Scales (Zimmerman et al. 2002a, 2002b) in English or Spanish. Yet, measures of morphosyntax knowledge have been related to NWR. Adams and Gathercole (1995) explored the relationship between NWR and grammatical complexity as indexed by mean length of utterance–morphemes (MLU-m), type-token ratio (TTR), and the Index of Productive Syntax (IPSyn) (Scarborough 1990). A significant correlation (0.364) between NWR and the total IPSyn was found for children between 34 and 37 months old. Follow-up testing 7 months later indicated a significant correlation only between initial IPSyn Noun Phrase subscore and NWR, not the total IPSyn. The authors proposed that this relationship was indicative of the role of short-term phonological memory in learning and then storing grammatical forms. Indeed, children with specific language impairment, whose language is characterized by difficulty in morphology and syntax, also have difficulty on NWR tasks (Graf Estes et al. 2007). In Swedish speakers, NWR performance was correlated to both phonology (0.61) and expressive grammar (0.41) (plural forms, genitives, propositions, negation and verb tense) as measured on a test of grammatical production (Sahlén et al. 1999).

Tasks that are less directly related to the lexicon and morphosyntax demonstrate how NWR might be related to language learning more broadly. In a study of Spanish speaking school-age children (8–10 years old) NWR was moderately correlated to grammatical integration (Girbau and Schwartz 2007). For children learning Greek and English, NWR performance correlated with their ability to perform translation tasks (Masoura and Gathercole 2005). These findings indicate that the role of phonological working memory extends beyond initial learning of words and syntactic forms to meta-awareness of language.

Developmental and relational similarities between performance on NWR tasks and language ability across multiple languages indicate that phonological working memory has strong universal characteristics. However, there are also language specific influences. At the level of syntax, Marton et al. (2006) observed cross-linguistic differences in NWR performance when children were asked to recall nonwords in short sentences with simple versus morphologically or syntactically complex constructions. Hungarian-speaking children recalled non-words in simple and short complex sentences. Performance was affected more by morphological complexity. English speakers on the other hand were affected more by syntactic complexity. This demonstrates that performance on NWR tasks is influenced by the particular language a person knows. In addition, the relationship between NWR performance and language depends on the aspect of language under study and the characteristics of that language.

Studying NWR performance in bilingual children provides a way to explore the role of language proficiency, usage and experience on phonological short-term memory. Because bilinguals learn two phonotactic systems, two lexical, and two syntactic systems, demands on their short-term memory and attentional systems may be different. Language learning in bilingual children is not equally divided across two languages. Varying levels of fluency and proficiency may have different relationships to NWR. Here, we were interested in exploring the effects of language knowledge on children’s abilities to represent, store, and produce nonwords, specifically:

What are the patterns of NWR performance in children with varying experience in Spanish and English?

What is the relationship between phonological short-term memory (as assessed by NWR) and performance on semantic and morphosyntax language tasks?

Methods

Participants

Sixty-two children between the ages of 4;6 and 6;5 participated in the study. Parents identified their children as Hispanic in a parent interview. Forty-four parents rated their Spanish as Mexican, two as Venezuelan, and one each as Puerto Rican, Honduran, Cuban, and pure Spanish. The type of Spanish spoken at home was unavailable for ten children. Two children were excluded from analyses due to their participation in a larger study. All children passed a hearing screening. We report on data of 60 children from the original 62 children tested. Fifty-four children were tested in both English and Spanish, one child was only tested in Spanish, and five children were tested in English only. The six children who were only tested in one language were unavailable for testing in the second language.

Parents completed questionnaires in which they reported on their children’s hour-by-hour exposure to (input) and use (output) of Spanish and English. They were also asked what language their child was exposed to at home and at school during each year of their life. From this information, the first year of English exposure was determined for each child.

Measures

Three measures, a NWR task, a semantic task and a morphosyntax task were administered in both English and Spanish. To the extent possible, we wanted to equate the influence of semantic knowledge on the performance on the NWR tasks across the children with differing patterns of experience with Spanish and English. Therefore, the NWR tasks were comprised of a set of low-word-like nonwords for each language. The items from the English NWR task were developed by Dollaghan and Campbell (1998). The Spanish nonwords were developed by Calderón (2003). The English list included twelve nonwords (four nonwords sets of two, three, and four syllables). The Spanish list consisted of 17 nonwords ranging from two- to four-syllables (four two-syllable, five three-syllable, and three four-syllable words). We report the percent of correct phonemes within each syllable length to control for the different numbers of nonwords in each language.

Both nonword lists followed the phonotactic constraints of each language and included only tense vowels. More specifically, Dollaghan and Campbell (1998) created their English nonwords by excluding late developing sounds, consonant clusters, and individual syllables that corresponded to real English words, positioning consonants in the beginning and ending of nonwords (and only in syllable positions where those consonants occur less the 25% of the time), and not using a consonant or vowel more than once in a nonword. Calderón (2003) described the constraints used in the development of the Spanish nonwords. All syllables occurred less than 200 times in the Alameda and Cuetos (1995) corpus of 2 million words. Nonwords did not resemble real words in English or Spanish. Few later developing sounds in Spanish were used (i.e., /s/ and /r/). Finally, stress patterns in the nonwords reflected the Spanish language, the penultimate or last syllable was stressed.

In addition, we wanted to ensure that English and Spanish nonwords were equivalent in their degree of nonword likeness. Ten bilingual adults listened to the 33 nonwords used in the study interspersed by six additional filler nonwords. The nonwords from both lists were randomized and each bilingual adult listened to each nonword once to decide if it sounded more English-like or more Spanish-like. Overall, English nonwords were rated to be English-like 80.5% of the time (standard deviation (SD) = 11.5). Spanish nonwords were rated to be Spanish-like 77.1% of the time (SD = 2.02).

Both English and Spanish nonwords were digitally recorded by a female speaker on a Power Macintosh G3 computer using the Peak 3.11 software. Nonwords were presented on laptop computers (iBook G3, MacBook, or Compaq). Presentation of English and Spanish nonwords was counterbalanced. Participants’ responses were audiorecorded by a microphone (Sony ECM-C115) clipped to a participant’s shirt and recorded on a digital recorder (Sony ICD-P320). The digital recordings were transferred to Dell (Optiplex GX620) computers using Digital Voice Editor 2 (version 2.4) for transcription.

The semantics measure came from the Bilingual English Spanish Assessment (BESA) (Peña et al. 2009). Items included associations, characteristic properties, categorization, functions, linguistic concepts, and similarities and differences (for an in-depth discussion of item development, see Peña et al. 2003). It is important to note that the semantics screener was developed to assess semantic knowledge, rather than receptive or expressive vocabulary. Twelve items from the BESA were selected for the Spanish Semantics Screener. The English semantics screener consisted of ten items for 4-year-old children and eleven items for 5-year-old children (eight of the items were in common across the two screeners). Statistical analyses compared the correlation between the full BESA subtest and the screener items in each language based on normative data for a large sample of 5-year-old children. Correlations were significant for Spanish semantics, r(172) = 0.855, p < 0.001 and for English semantics, r(185) = 0.887, p < 0.001. In addition, the BESA semantics subtest and the semantics screener were independently administered to 20 children (15 of whom also participated in the current study). Results indicated significant positive correlations between the BESA semantics subtest and the semantics screener for Spanish, r(19) = 0.696, p < 0.001 and English r(19) = 0.639, p < 0.001.

The Morphosyntax screener was also created from items on the BESA. Both English and Spanish morphosyntax screeners included cloze task items (e.g., articles, clitics, and subjunctive for Spanish; third-person singular, negation, passives, past tense, progressive -ing, and copula for English) and sentence repetition items (Gutiérrez-Clellen et al. 2006). There were 17 items on the Spanish morphosyntax screener and 16 items on the English morphosyntax screener. Based on normative data for 5-year-old Spanish- and English-speaking children, correlations between the BESA morphosyntax subtest and the screener were statistically significant for Spanish r(140) = 0.826, p < 0.001 and English r(127) = 0.893, p < 0.001. The same 20 children were administered the morphosyntax screener in both languages and the BESA morphosyntax subtest independently. There were large significant correlations between the BESA morphosyntax subtest and the morphosyntax screener for both Spanish r(19) = 0.858, p < 0.001 and English r = 0.754, p < 0.001.

Procedures and analyses

Administration of the tasks took place at each child’s school in a quiet room and were administered by a bilingual speech language pathologist. For all tasks, instructions were provided to the child in the target language, English or Spanish. For the NWR task, the examiner said, ‘You are going to hear some silly words. Listen carefully to each word and then tell me what you heard. Let’s practice.’ The examiner then presented two practice items. If the participant did not respond to the practice items, more items were given for practice. The nonwords were then presented. Every participant attempted the task.

For the Semantics screener, the examiner said, ‘I’m going to show you some pictures and then ask you some questions about my pictures.’ The items were then presented. The Morphosyntax screener began with demonstration items. Each target form for the cloze tasks was preceded by two demonstration items of that form. Feedback was provided to the child during the demonstration items until they understood the task. There were also two sentence repetition examples for that portion of the screener. Again, all instruction and demonstration items were presented in the target language. Every child attempted both the semantics and morphosyntax screeners.

A bilingual research assistant transcribed each nonword by listening to the recording through headphones (Labtex Elite-820) using Digital Voice Editor 2. Each phoneme was scored as correct or incorrect. Scoring procedures followed those used by Dollaghan and Campbell (1998). An incorrect score included an omission or substitution for the target phoneme. Distortions were scored as correct. Additions were not counted as errors. When syllables were omitted, the remaining syllables were matched to the target syllables and scored for phonemes in that target syllable. For each syllable level, the total number of correct phonemes was divided by the total number of phonemes and reported as percent phonemes correct (PPC). PPC is an average score for a syllable level. This allowed us to compare performance at each syllable level regardless of the number of items for each level. A second bilingual research assistant independently transcribed and scored 11% of the samples (13 out of 114). Scores were compared with the scores from the first research assistant on a phoneme by phoneme level to establish scoring reliability. Scoring reliability for the 13 samples ranged from 76% to 89% with an average of 84%.

The semantics and morphosyntax screeners were administered in English and Spanish by bilingual clinicians. Responses were recorded verbatim during administration and later scored as correct or incorrect. Item scores were then entered into an Excel spreadsheet. Percentages for each screener were calculated and entered into the spreadsheet for analysis.

Results

Descriptive results

Table 2 shows the breakdown of NWR and BESA scores by language of testing (English and Spanish) and number of syllables. NWR scores appear to decline as the number of syllables increase. BESA scores are shown separately for Morphosyntax and Semantics. Note however the large standard deviations for all the scores.

Table 2.

Number of participants, means and standard deviations for nonword repetition (NWR) scores and Bilingual English Spanish Assessment (BESA) scores by language and group

| English |

Spanish |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| NWR percentage correct | ||||

| Two syllables | 70.2 | 16.4 | 78.9 | 12.4 |

| Three syllables | 66.3 | 15.9 | 69.5 | 13 |

| Four syllables | 51.7 | 17.8 | 64.3 | 15.3 |

| BESA scales | ||||

| Morphosyntax | 4.5 | 4.6 | 8.5 | 5.3 |

| Semantics | 4.7 | 3.2 | 6.8 | 3.5 |

| Current language experience | ||||

| Percentage input | 38.7 | 31.4 | 61.2 | 31.6 |

| Percentage output | 43.9 | 35.4 | 56.3 | 35.2 |

Note: SD, standard deviation.

Analysis

To address the study’s overall goal of comparing NWR scores by children’s language experience and test language, five statistical models were run using NWR scores as the dependent variable (Table 3) to test the two hypotheses separately for English and Spanish. First, a mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test whether there was a direct effect of nonword length (number of syllables), language experience (input and output), language outcomes (morphosyntax and semantics), and cumulative language exposure (age and age of first English exposure). Second, four mixed-model ANOVAs tested whether NWR scores varied depending on the joint influence of two predictors. These models tested whether the relationship between NWR scores and language outcomes, language experience, and exposure varied depending on nonword length. In addition, the relationship between language experiences and NWR scores was tested whether it varied depending on exposure.

Table 3.

Effects tested in each model and the corresponding research questions

| Model effect | Model 1: Direct effects | Model 2a: Outcomes X syllables | Model 2b: Current experience X syllables | Model 2c: Prior experience X syllables | Model 2d: Prior experience by current experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language output | × | × | × | × | |

| Language input | × | × | × | × | |

| Number of syllables | × | × | × | × | |

| Age | × | × | × | × | |

| First exposure to English | × | × | × | × | |

| Morphosyntax | × | × | × | × | |

| Semantics | × | × | × | × | |

| Language performance interactions | |||||

| Number of syllables X morphosyntax | × | ||||

| Number of syllables X semantics | × | ||||

| Current language exposure | |||||

| Number of syllables X input | × | ||||

| Number of syllables X output | × | ||||

| Cumulative exposure | |||||

| Number of syllables X age | × | ||||

| Number of syllables X age of first English exposure | × | ||||

| Cumulative exposure by current exposure | |||||

| Age X input | × | ||||

| Age X output | × | ||||

Each of the five models utilized a multilevel approach to avoid the possibility of statistically significant differences due to the decreased standard error resulting from non-independence in participant scores within a particular person depending on language (English or Spanish), or NWR word length (two, three, and four syllables) (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). The degrees of freedom for statistical significance tests were calculated using the Kenward–Roger adjustment for degrees of freedom in mixed-models for repeated measures, because it reduces the potential for Type I error (Littel et al. 2002). A random person effect was included to account for individual effect on each language assessed. For the NWR task within-subject effect, the unstructured variance–covariance matrix was used to model the within-person, within-language correlation among scores. Effect sizes are reported as standardized regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals for continuous variables and as pseudo-R2 measures based on proportional reduction in residual error for non-continuous variables such as syllable (Snijders and Bosker 1999). Cohen (1988) provided the following guide for interpretation of standardized coefficients: 0.5 is large, 0.3 is moderate, 0.1 is small, and less than 0.1 is trivial. To help understand the meaning of the standardized regression coefficients, they can be squared to get a measure of explained variance. For example, a coefficient of 0.2 would indicate that 4% of the variance was explained; a coefficient of 0.4 would explain 16% of the variance and so forth.

Research question: direct effects

The first research question concerned direct effects of number of syllables, language experience, language outcomes and language exposure for the English and Spanish nonwords (see Table 4). Results are reported separate for English and Spanish nonwords.

Table 4.

Model 1: Direct effects

| English |

Spanish |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Number of d.f. | Den d.f. | F-value | Pr > F | Number of d.f. | Den d.f. | F-value | Pr > F |

| Nonword length | 2 | 50 | 29.16 | <0.0001 | 2 | 45 | 22.52 | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1 | 45 | 2.42 | 0.1270 | 1 | 40 | 4.06 | 0.0506 |

| Age at first English exposure | 1 | 45 | 0.08 | 0.7722 | 1 | 40 | 1.81 | 0.1860 |

| Morphosyntax | 1 | 45 | 5.90 | 0.0192 | 1 | 40 | 11.85 | 0.0014 |

| Semantics | 1 | 45 | 2.10 | 0.1538 | 1 | 40 | 0.31 | 0.5826 |

| Input | 1 | 45 | 0.16 | 0.6880 | 1 | 40 | 1.70 | 0.2003 |

| Output | 1 | 45 | 0.05 | 0.8330 | 1 | 40 | 5.43 | 0.0249 |

Note: Number of d.f. = number of groups - 1; Den d.f. = n - number of groups.

English

The mixed-model analysis showed there were statistically significant main effects for morphosyntax F(1,45) = 5.9, p < 0.05, and nonword length F(2, 50) = 29.2, p < 0.001 (R2 = 0.28). A one unit increase in Morphosyntax score was related to a 1.5% increase in percentage correct standardized coefficient = 0.47, confidence interval (CI) = 0.08–0.86. The means for the nonword length were two syllables = 70.2, three syllables = 65.0, and four syllables = 50.9. The differences between two- and three-syllables with four syllables were significantly different at the p < 0.05 level using Tukey–Kramer adjusted multiple comparison tests.

Spanish

The mixed-model analysis showed there were statistically significant main effects for morphosyntax F(1,40) = 11.8, p < 0.001, language output F(1,40) = 5.4, p < 0.05, and nonword length F(2,45) = 22.5, p < 0.001 (R2 = 0.28). A one unit increase in Morphosyntax score was related to a 1.7% increase in percentage correct (standardized coefficient = 0.51, CI = 0.08–0.86). A 1% increase in Spanish output was related to a 0.3 decrease in percentage correct (standardized coefficient = −0.59, CI = −1.1 to −0.08). The means for the nonword length were two syllables = 77.9, three syllables = 68.9, and four syllables = 62.6. The differences between all three nonword lengths were significantly different at the p < 0.05 level using Tukey–Kramer adjusted multiple comparison tests.

Research question: interaction effects

The second research question concerned interactive effects of nonword length, language experience, language outcomes and language exposure for the English and Spanish nonwords (see Table 5). There was a marginally statistically significant interaction between nonword length and morphosyntax (model 2a) F(2,48) = 3.2, p = 0.052 in English. There were no statistically significant interactions for language experience (model 2b) for either English or Spanish nonwords exposure and language outcomes (model 2d) or language experiences (model 2b) for either English or Spanish nonwords. There were statistically significant interactions between nonword length and age of first exposure to English for both English F(2,48) = 6.1, p < 0.01 (R2 = 0.05) and Spanish nonwords F(2,43) = 7.3, p < 0.01 (R2 = 0.08).

Table 5.

Model 2: Test of interactions

| English |

Spanish |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interactions | Number of d.f. | Den d.f. | F-value | Pr > F | Number of d.f. | Den d.f. | F-value | Pr > F |

| Semantics*Nonword length (Model 2a) | 2 | 48 | 0.47 | 0.6267 | 2 | 43 | 0.20 | 0.8214 |

| Morphosyntax*Nonword length (Model 2a) | 2 | 48 | 3.15 | 0.0516 | 2 | 43 | 0.45 | 0.6376 |

| Input by nonword length (Model 2b) | 2 | 48 | 1.96 | 0.1524 | 2 | 43 | 0.19 | 0.8297 |

| Output by nonword length (Model 2b) | 2 | 48 | 0.90 | 0.4141 | 2 | 43 | 0.80 | 0.4562 |

| Age by nonword length (Model 2c) | 2 | 48 | 0.17 | 0.8404 | 2 | 43 | 1.51 | 0.2333 |

| Age at first English exposure by nonword length (Model 2c) | 2 | 48 | 6.12 | 0.0043 | 2 | 43 | 7.32 | 0.0018 |

| Age*Input (Model 2d) | 1 | 43 | 0.01 | 0.9079 | 1 | 38 | 0.49 | 0.4865 |

| Age*Output (Model 2d) | 1 | 43 | 0.06 | 0.8052 | 1 | 38 | 1.55 | 0.2205 |

Note: Number of d.f. = number of groups - 1; Den d.f. = n - number of groups.

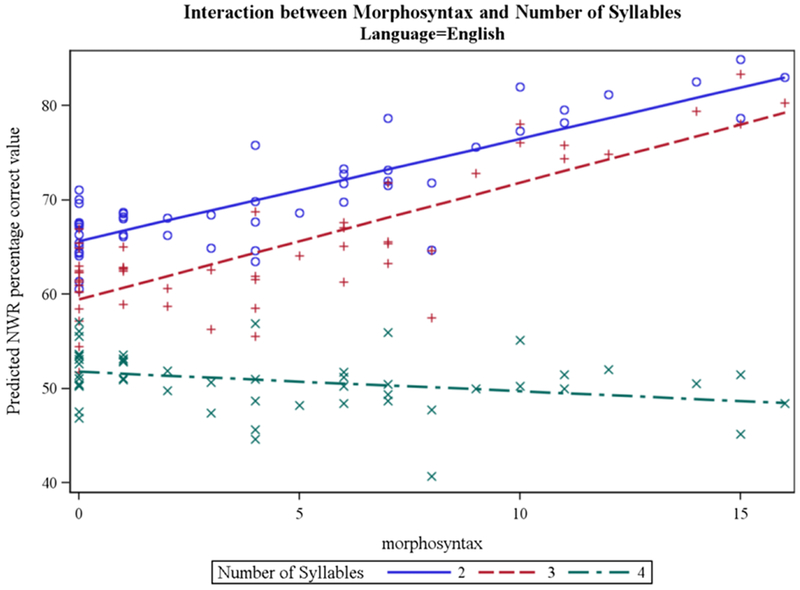

English

Figure 1 shows the interaction between English nonword length and morphosyntax. Ordinary least-squares (OLS) regressions between NWR score and morphosyntax score by number of syllables showed there were positive relationships between morphosyntax and NWR percentage correct for two syllables (r = 0.34, R2 = 0.12) and three syllable (r = 0.41, R2 = 0.17) and minimal relationship for four syllables (r = 0.01, R2 = 0.00).

Figure 1.

English nonword repetition (NWR) score as outcome.

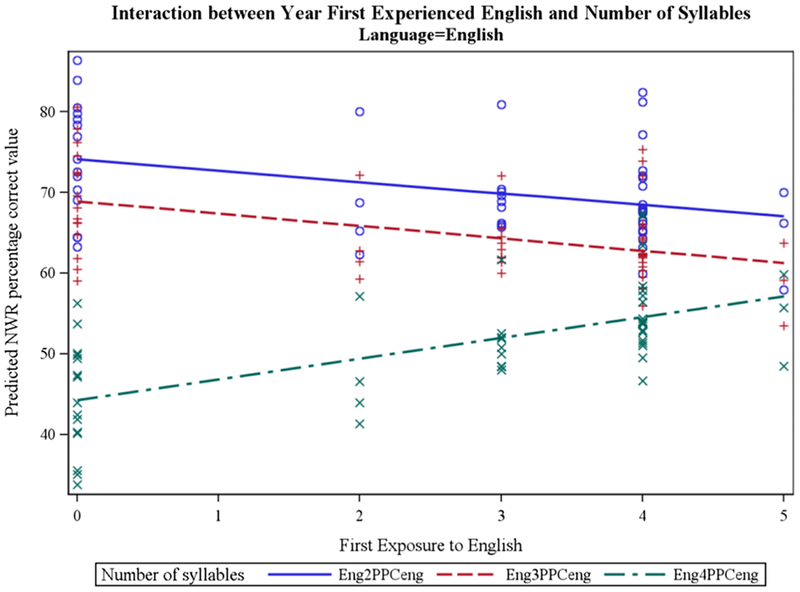

Figure 2 illustrates the interaction between English nonword length and age at first English exposure. OLS regression estimates showed that for two-syllable (r = −0.15, R2 = 0.02) and three-syllable (r = −0.18, R2 = 0.03) nonwords, there is a negative relationship between age at first English exposure and percentage of nonwords correct. For four-syllable length nonwords, later first exposure is related to higher percentage of nonwords correct (r = 0.26, R2 = 0.07).

Figure 2.

English nonword repetition (NWR) score as outcome.

Spanish

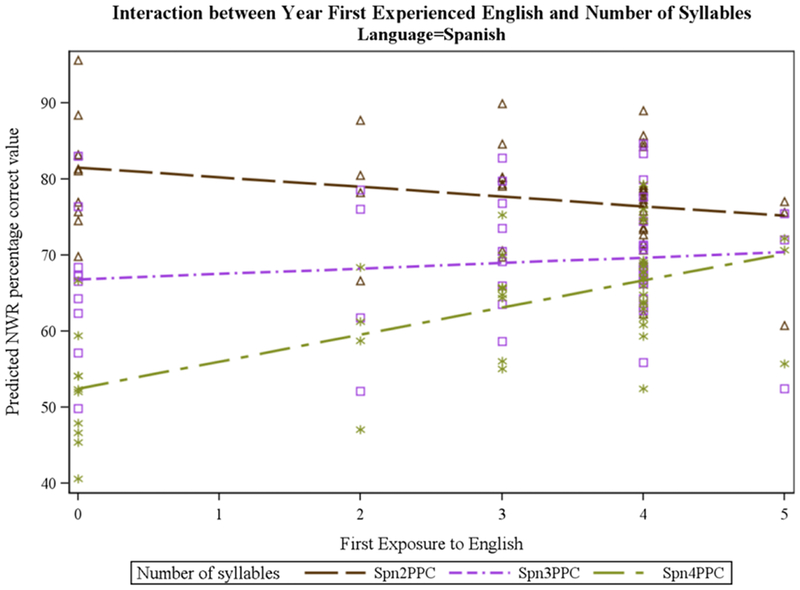

Figure 3 shows the interaction between nonword length and age at first English exposure for Spanish NWR. For two syllable nonwords, there is a negative relationship between age at first English exposure and percentage of nonwords correct (r = −0.16, R2 = 0.03). Later exposure to English is related to higher percentage of nonwords correct for three-syllable (r = 0.08, R2 = 0.01) and four-syllable length nonwords (r = 0.40, R2 = 0.16).

Figure 3.

Spanish nonword repetition (NWR) score as outcome.

Discussion

The process of repeating nonwords involves listening to sounds in a sequence, remembering them, and repeating them back. NWR is routinely considered to be a measure of phonological short-term memory because phonological storage, phonological representation, and speech production play large roles in the process, especially when the syllable sequences are low in word-likeness and the phoneme sequences are low in frequency. In this study, we do not attempt to determine which of these systems plays a bigger role in repeating nonwords. Rather, we examine the performance of children who have knowledge of two language systems and varying experiences with those languages to explore the effects of language knowledge and experience on children’s abilities to represent, store, and produce nonwords. To explore these relationships, we examined how bilingual children performed on two NWR tasks (one English-like and one Spanish-like) with low word-likeness and low phoneme sequence frequencies. Our goals were to assess NWR performance across Spanish and English language learners, and to explore the relationships between NWR performance and performance on measures of semantics and morphosyntax in English and Spanish.

The results from this study reveal two major patterns. First, NWR performance was similar across English and Spanish with differences in performance patterns based on accuracy. NWR performance in both English and Spanish was also significantly correlated to cumulative language experience. Second, there were significant correlations between NWR and morphosyntax in both English and Spanish, and no correlations with semantics.

With respect to overall patterns of NWR performance similarities, children’s accuracy at repeating nonwords in both English and Spanish decreased with word length which is consistent with previous studies (Dollaghan and Campbell 1998, Girbau and Schwartz 2007, Sahlén et al. 1999, Ebert et al. 2008). NWR performance in Spanish was higher than in English overall. Yet, the higher accuracy in Spanish NWR appears to come from differences between the languages and not within the subjects.

Spanish is characterized by frequent multi-syllabic words comprised mainly of CV combinations. Children who have experience with many multisyllabic words in their language(s) have that knowledge in their long-term language memory. Spanish language experience may have helped the children with more experience use their phonological working memory systems more effectively to repeat Spanish nonwords. However, the descriptive pattern of more accurate performance for the Spanish-like items than the English-like items was consistent across all children. Clearly, this pattern of findings is not consistent with an explanation that focuses solely on the role of prior knowledge of Spanish or the nature of Spanish. Recall that the phonological system of Spanish is mastered relatively early compared to English. This earlier mastery may be due to the smaller number of phonemes and contrasts in the sound inventory of Spanish. Fewer phonemes in the system permits longer CV strings because there are relatively fewer options in each position of the CV syllable. Fewer options could decrease memory load in comparison to that of English allowing children to produce longer strings of syllables. Bilingual English/Spanish children have the same level of complexity in their phonetic inventories, as do monolingual children. Yet, their phonetic systems are separate, as demonstrated by variations in their phonetic inventories (Fabiano-Smith and Barlow 2009).

Future research with Spanish NWR needs to include five syllable nonwords for the trajectory of accuracy across syllable lengths to look similar to English. Other studies have included longer nonwords in multi-syllabic languages including Portuguese (Santos et al. 2006), Swedish (Sahlén et al. 1999), and Spanish (Girbau and Schwartz 2007).

The significant interaction between word lengths and age of first exposure to English was consistent for both English and Spanish. The later a child was first exposed to English, the more accurate they were at repeating four-syllable nonwords. In English, later exposure to English resulted in slightly lower performance on two- and three-syllable nonwords. In Spanish, later exposure to English was not related to performance on two- and three-syllable nonwords. These interactions may reveal an effect of long-term experience and practice with a language that results in more ingrained, automatic production. Those children who have more cumulative experience with Spanish (as noted by later exposure to English) repeat longer nonwords more accurately. Although these interactions require replications in larger samples, the findings reflect the multi-syllabic nature of the Spanish language. Spanish is a highly inflected language in which linguistic complexity is gained by producing longer words. More practice with this inflected system leads to better performance on NWR. Children with more cumulative experience with multi-syllabic words, are more efficient at repeating longer nonwords regardless of the language they reflect.

Children who had more output in Spanish were slightly less accurate at repeating Spanish nonwords. This finding has limited practical significance given that a 1% increase in Spanish output was related to a 0.3% decrease in PPC. The measure of Spanish output reflects a child’s current language use. Children often have shifts in their current output depending on context, knowledge, and preference. In contrast, the age of first exposure to English reflects a child’s cumulative language experience. In this case, cumulative language experience was more important in determining NWR performance than current language experience. This experience with manipulating more syllables in Spanish influences the ability to manipulate more syllables in nonwords.

Another explanation of the possible influence on performance is that the nonwords in one language may appear word-like in the other languages. Here for example, nonword-like stimuli were used in both languages. The English nonwords such as veitachaidoip have many open syllables, are comparable in length to Spanish words, and the consonants are all permissible in Spanish. Spanish words conform to Spanish phonotactic rules but they include low frequency closed syllables that are less frequent in Spanish (e.g., merfas). The vowels are specific to the target language in each case. While this drift may be inevitable, it is important to monitor whether or not the nonwords of one language contain morphemes of the other that might inadvertently recruit linguistic knowledge of the other language. Recall that adults judged the nonwords in this study to be like the target language.

The second finding that emerged in this study was the relationship between morphosyntax and NWR in both English and Spanish. Our analysis demonstrates that NWR was positively related to the morphosyntax scores. Effect sizes revealed these relationships to be strong. Morphosyntax scores accounted for 22% of the variance in PPC for English and 26% for Spanish. This relationship is consistent with previous work (Adams and Gathercole 1995, Sahlén et al. 1999). Children tapped into similar skills to complete NWR and morphosyntax tasks. It appears that the better children are at manipulating morphemes, the better they are at repeating nonwords.

The interaction trend between morphosyntax and syllable length in English showed that better performance on English morphosyntax yielded better performance on two- and three-syllable nonwords. Yet, the same pattern was not seen for four-syllable nonwords. There was no relationship between morphosyntax and nonword performance for four-syllable nonwords in English. This suggests that children were tapping into the same mechanisms to repeat two- and three-syllable nonwords as they did to mediate morphosyntax tasks. However, four-syllable English nonword results did not demonstrate the same relationship. Possible sources of difference could be greater practice producing multi-syllabic words or lessoned articulatory or memory demands with Spanish four-syllable words due to the consonant vowels patters that predominate in Spanish. Recall that overall children had more exposure and practice with Spanish. Their scores on both the semantics and morphosyntax screeners were higher in Spanish.

These results provide further evidence that children may be demonstrating a practice effect. The more they are able to manipulate morphemes, the more accurate they are at repeating nonwords. The interaction between first exposure to English and syllable length provides converging evidence that the more practice a child has manipulating syllables, the better they are able to repeat four-syllable nonwords in both Spanish and English.

Overall, differences in NWR performance were not dependent on the test. Rather, children’s knowledge and experience with language(s) affected performance. The children demonstrated higher scores in Spanish semantics than in English semantics. Exposure and experience with English is increasing for all children but, as a group, they had more experience in Spanish than in English. Thus, these children are in a state of transition as they become more familiar and productive with the English language.

Conclusion

This study of NWR with both languages of bilingual children adds important information concerning the interaction of phonological working memory and language experience. Children’s knowledge and familiarity with language(s) interact with the structure of the language(s). Phonological short-term memory skills as measured by NWR performance rely on the child’s adeptness as a learner and on their language experience. Children’s language experiences may affect their abilities to mediate morphosyntactic tasks during assessment and in academic settings as shown by strong effect sizes. Different relationships are observed with NWR depending on language experiences. This has implications for language teaching as bilingual children constantly shift their language dominance between their two languages. Their performance on tasks that use phonological short-term memory skills may vary as their dominance shifts. These results should be interpreted cautiously due to the overall small sample size. Further research with bilingual children will help interpret the relationship between language experience and phonological working memory.

What this paper adds.

What is already known on this subject

The ability to repeat nonwords increases with age and language experience across languages. This relationship holds for bilingual children as well, but in several studies bilingual performance falls below monolingual performance. Most studies with bilingual children have used only nonwords based on one language. This study explores nonword repetition and language performance in English and Spanish with children who have been exposed to both languages.

What this study adds

Children’s performance varied as a function of language exposure across languages, but they demonstrated higher accuracy in their production of Spanish nonwords. Semantics and morphosyntax have different relationships with nonword repetition in children with varying language experiences.

Acknowledgements

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Adams A-M and Gathercole SE, 1995, Phonological working memory and speech production in preschool children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 38, 403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alameda JR and Cuetos F, 1995, Diccionario de frequencies de las unidades linguisticas del castellano (Oviedo: Universidad de Oviedo; ). [Google Scholar]

- Archibald LMD and Gathercole SE, 2006, Nonword repetition: a comparison of tests. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 49, 970–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A, 2003, Working memory and language: an overview. Journal of Communication Disorders, 36, 189–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E, Majumder S and Martin MM, 2003, Developing phonological awareness: is there a bilingual advantage? Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolini U, Arfé B, Caselli MC, Degasperi L, Deevy P. and Leonard LB, 2006, Clinical markers for specific language impairment in Italian: The contribution of clitic and non-word repetition. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 41, 695–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowey JA, 1996, On the association between phonological memory and receptive vocabulary in five-year-olds. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 63, 44–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowey JA, 1997, What does nonword repetition measure? A reply to Gathercole and Baddeley. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 67, 295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón J, 2003, Working memory in Spanish–English bilinguals with language impairment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California, San Diego and Sad Diego State University. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung H, 1996, Nonword span as a unique predictor of second-language vocabulary language. Developmental Psychology, 32, 867–873. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, 1988, Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; ). [Google Scholar]

- D’Odorico L, Assanelli A, Franco F and Jacob V, 2007, A follow-up study on Italian late talkers: development of language, short-term memory, phonological awareness, impulsiveness, and attention. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Dollaghan CA, Biber ME and Campbell TF, 1995, Lexical influences on nonword repetition. Applied Psycholinguistics, 16, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Dollaghan CA and Campbell TF, 1998, Nonword repetition and child language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41, 1136–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM and Dunn LM, 1982, British Picture Vocabulary Scale (Windsor: NFER-Nelson; ). [Google Scholar]

- Ebert KD, Kalanek J, Cordero KN and Kohnert K, 2008, Spanish nonword repetition: stimuli development and preliminary results. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 29, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Beckman ME and Munson B, 2004, The interaction between vocabulary size and phonotactic probability effects of children’s production accuracy and fluency in nonword repetition. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 47, 421–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano-Smith L and Barlow JA, forthcoming 2009, Interaction in bilingual phonological acquisition: Evidence from phonetic inventories. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch SA, Large NR and Pisoni DB, 2000, Perception of wordlikeness: effects of segment probability and length on the processing of nonwords. Journal of Memory and Language, 42, 481–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, 2006, Nonword repetition and word learning: the nature of the relationship. Applied Psycholinguistics, 27, 513–543. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE and Baddeley AD, 1989, Evaluation of the role of phonological STM in the development of vocabulary in children: a longitudinal study. Journal of Memory and Language, 28, 200–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Frankish CR, Pickering SJ and Peaker S, 1999, Phonotactic influences on short-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 25, 84–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Willis CS and Emslie H, 1992, Phonological memory and vocabulary development during the early years: a longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 28, 887–898. [Google Scholar]

- Gijsel MAR, Bosman AMT and Verhoeven L, 2006, Kindergarten risk factors, cognitive factors, and teacher judgments as predictors of early reading in Dutch. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39, 558–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girbau D and Schwartz RG, 2007, Non-word repetition in Spanish-speaking children with Specific Language Impairment (SLI). International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 42, 59–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BA and Iglesias A, 1996, Phonological patterns in normally developing Spanish-speaking 3- and 4-year-olds of Puerto Rican descent. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie, 45, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Forster KI and Frost R, 1997, Translation priming with different scripts: masked priming with cognates and noncognates in Hebrew-English bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 23, 1122–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JK and Dell GS, 2001, Phonological neighbourhood effects: evidence from aphasia and connectionist modeling. Brain and Language, 79, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Graf Estes K, Evans JL and Else-Quest NM, 2007, Differences in the nonword repetition performance of children with and without specific language impairment: a meta-analysis. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 50, 177–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen VF, Restrepo MA. and Simón-Cereijido G, 2006, Evaluating the discriminant accuracy of a grammatical measure with Spanish-speaking children. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 49, 1209–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond R, 2001, The Sounds of Spanish: Analysis and Application (Somerville, MA: Cascadilla; ). [Google Scholar]

- Klein D,Watkins KE, Zatorre RJ and Milner B, 2006, Word and nonword repetition in bilingual subjects: a PET study. Human Brain Mapping, 27, 153–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert K, Windsor J and Yim D, 2006, Do language-based processing tasks separate children with language impairment from typical bilinguals? Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 21, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Littel RC, Stroup WW and Freund RJ, 2002, SAS for Linear Models (Cary, NC: SAS Institute; ). [Google Scholar]

- Marton K, Schwartz RG, Farkas L and Katsnelson V, 2006, Effect of sentence length and complexity on working memory performance in Hungarian children with specific language impairment (SLI): a cross-linguistic comparison. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 41, 653–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoura EV and Gathercole SE, 1999, Phonological short-term memory and foreign language learning. International Journal of Psychology, 34, 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Masoura EV and Gathercole SE, 2005, Contrasting contributions of phonological short-term memory and long-term knowledge to vocabulary learning in a foreign language. Memory, 13, 422–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson B, Kurtz BA and Windsor J, 2005, The influence of vocabulary size, phonotactic probability, and wordlikeness on nonword repetition of children with and without specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 48, 1022–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro T, 1968, Studies in Spanish Phonology (Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Peña ED, Bedore LM and Rappazzo C, 2003, Comparison of Spanish, English, and bilingual children’s performance across semantic tasks. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 34, 5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña ED,Gutiérrez-Clellen VF, Iglesias A,Goldstein BA. andBedore LM, forthcoming 2009, Bilingual English Spanish Assessment (in press).

- Porter JH and Hodson BW, 2001, Collaborating to obtain phonological acquisition data for local schools. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 32, 165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radeborg K, Barthelom E, Sjoberg M and Sahlén B, 2006, A Swedish non-word repetition test for preschool children. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47, 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW and Bryk AS, 2002, Hierarchical Linearm Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; ). [Google Scholar]

- Reuterskiöld-Wagner C, Sahlén B. and Nyman A, 2005, Non-word repetition and non-word discrimination in Swedish preschool children. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 19, 681–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy P and Chiat S, 2004, A prosodically controlled word and nonword repetition task for 2- to 4-year-olds: evidence from typically developing children. Journal of Speech, Language, and hearing Research, 47, 223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahlén B, Reuterskiold-Wagner C, Nettelbladt U. and Radeborg K, 1999, Non-word repetition in children with language impairment—pitfalls and possibilities. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 34, 337–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos FH and Bueno OFA, 2003, Validation of the Brazilian children’s test of pseudoword repetition in Portuguese speakers aged 4 to 10 years. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 36, 1533–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos FH, Bueno OFA and Gathercole SE, 2006, Errors in nonword repetition: bridging short- and long-term memory. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 39, 371–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough HS, 1990, Index of Productive Syntax. Applied Psycholinguistics, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD and Kent RD, 1982, Clinical Phonetics (New York, NY: Macmillan; ). [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB and Bosker R, 1999, Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; ). [Google Scholar]

- Stokes SF, Wong AMY, Fletcher P and Leonard LB, 2006, Nonword repetition and sentence repetition as clinical markers of specific language impairment: the case of Cantonese. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 219–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn ASC and Gathercole SE, 1999, Language-specific knowledge and short-term memory in bilingual and non-bilingual children. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A: Human Experimental Psychology, 52, 303–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitevitch MS, 2002, The influence of phonological similarity neighourhoods on speech production. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 28, 735–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitevitch MS and Stamer MK, 2006, The curious case of competition in Spanish speech production. Language and Cognitive Processes, 21, 760–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman IL, Steiner VG and Pond RE, 2002a, Preschool Language Scale, Fourth Edition—Spanish Edition (San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; ). [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman IL, Steiner VG and Pond RE, 2002b, Preschool Language Scale, Fourth Edition—English Edition (San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; ). [Google Scholar]