Abstract

Background

Purulent pericarditis is an unusual first manifestation of HIV-infected patients. Co-infections in this scenario are possible and challenging. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a frequent agent in purulent pericarditis related to HIV infection but co-infection with Staphylococcus aureus is rarely reported.

Case presentation

We describe a rare case in otherwise asymptomatic 39-year-old diabetic man with acute purulent pericarditis leading to tamponade due to S. aureus and evidences of M. tuberculosis co-infection. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus was positive.

Conclusion

Primary purulent pericarditis is a rare condition and may indicate underlying HIV infection. In this scenario, coinfection with multiple organisms are possible and patient should be tested for underlying tuberculosis in addition to standard microbiological workup.

INTRODUCTION

Purulent pericarditis is a rare and life threating condition corresponding approximately with 1% of all cases of pericarditis [1, 2]. It generally occurs from adjacent infectious conditions such as like pneumonia, empyema and endocarditis, but also can presents as primary infection, particularly, in oncologic patients, diabetes and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection [3].

In the antibiotic era, the most common causative organism is Staphylococcus aureus [4]. Tuberculosis is a common cause of pericarditis in HIV-endemic areas and carries a worse prognosis in the HIV-infected population [5]. A case of purulent pericarditis due to infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a patient with advanced features of HIV infection has been reported [6], but there are no previous reports of co-infection with S. aureus as first manifestation.

In this report, we present to our knowledge the first case of primary purulent pericarditis with co-infection with M. tuberculosis and S. aureus as first manifestation of HIV infection.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 39-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a 1-week history of isolated episode of fever (axillary temperature: 39°C) and diffuse myalgia. In the 3 next days, he developed pleuritic type precordial chest pain and progressive dyspnea. His past medical records were only remarkable for diabetes mellitus type 1 on insulin treatment. On admission, the patient was apyrexial (36.7°C), dyspneic at rest (respiratory rate of 24/min), with a blood pressure of 160/90 mmHg, pulse rate of 130 beats per minute, distended jugular veins, pericardial friction rub and heart sounds were not muffled. Pulmonary auscultation revealed diminished sounds in bases. Abdominal examination was unremarkable,

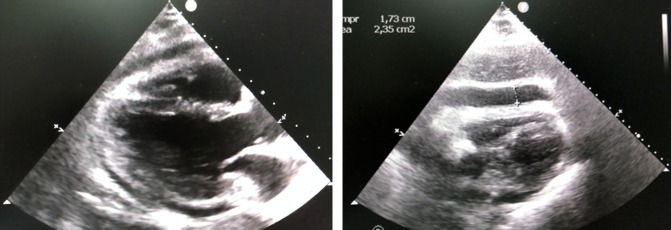

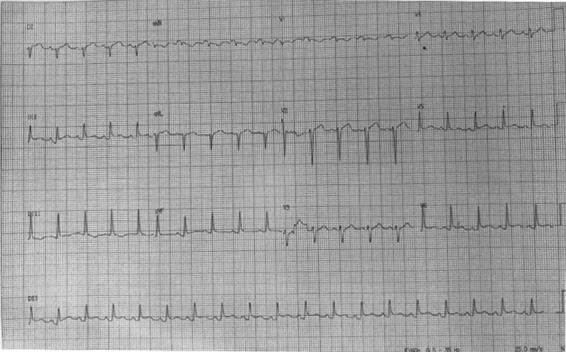

An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus tachycardia, normal amplitude QRS complexes, concaved ST elevation with concordant T waves in DII, DIII, V4, V5 e V6 leads, reciprocal ST depression and PR elevation in lead aVR and PR depression in lead DII (Fig. 1). Chest radiography revealed a massively enlarged globular cardiac shadow and left pleural effusion (Fig. 2).

Figure 1:

ECG revealing typical pericarditis patterns.

Figure 2:

Chest radiography showed cardiomegaly and left pleural effusion.

Laboratory studies revealed a white-blood-cell count of 10 800/μl with 83% segmented cells, and 9% lymphocytes, hemoglobin of 10.5 g/dl, and a platelet count of 182 000/μl. CRP was 192 U/l, renal and liver function tests were normal. NT- proBNP levels was 1155 pg/ml. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. An arterial line was placed and pulsus paradoxus was observed.

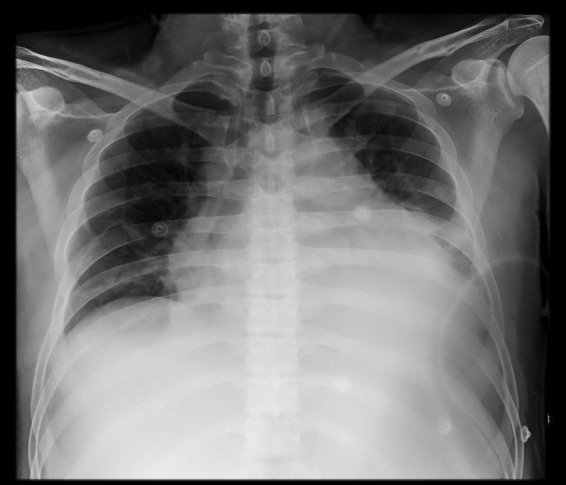

An echocardiogram (Fig. 3) performed on the day after admission demonstrated good left ventricular function, ejection fraction of 78%, no signals of valve dysfunctions, a massive pericardial effusion and right ventricular systolic collapse, features consistent with a diagnosis of cardiac tamponade (Fig. 3). Pericardiocentesis was performed, and hemodynamic stability was achieved after direct aspiration of 160 ml purulent fluid. Laboratory analysis of the pericardial fluid showed 500 000 nucleated cells/μl with 80% segmented cells, 8% lymphocytes, and 2% eosinophils, 1000 red blood cells/μl, lactate dehydrogenase of 19 523 U/l, triglycerides of 90 mg/dl, glucose of 36 mg/dl, protein of 5.9 g/dl and pH of 6.0. Direct microbiological analysis revealed gram-positive cocci and no acid-fast bacilli were present.

Figure 3:

A transthoracic echocardiogram in systolic frame (left) and diastolic frame (right) revealing a large pericardial effusion with right ventricular collapse.

Vancomycin (1 g IV every 12 hours) was started and rapid HIV test was performed with positive result. In the next day a follow-up echocardiogram performed showed a substantial reaccumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac, with right ventricular collapse. An urgent surgical approach was indicated and a drain was placed in the pericardial sac for continuous drainage.

Bacterial, fungal and tuberculous culture from pericardial fluid were set up. Further assessment revealed Methicilin-sensitive S. aureus in two samples (fluid from pericardiocentesis and from surgical drainage) and high levels of adenosine deaminase (ADA), >200 U/l, in the pericardial fluid. After 5 days of antibiotic, the patient developed episodes of fever and continuous drainage of purulent fluid without improvement. Tuberculostatic drugs were initiated, just after the ADA result. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus was positive (Westen Blot test), CD4 count was 28 cells/μl and HIV viral load 347 609 copies/mm3 (log 5.54) Pericardial biopsy revealed non-specific inflammation pattern, but was culture negative. A thoracic drain was also placed for large pleural effusion but with no evidence of empyema. A chest computed tomography (CT) did not reveal any pulmonary parenchymal lesion or lymphadenopathy and abdominal CT scan was normal. After 7 days with tuberculosis treatment, the fluid aspect reduced and the pericardial drain was removed.

The pending pericardial fluid cultures persisted negatives for fungal and tuberculous etiologies all over the time. Cytology for malignant cells of pericardial fluid was negative.

Corticosteroids were not prescribed due to lack of definite indications on literature and possible side effects in this particular case (diabetes, bacterial co-infection and HIV infection).

Another echocardiogram was performed with no fluid reaccumulation, but showed constrictive pericarditis patterns. Rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol were prescribed for 2 months followed by four months of rifampin and isoniazid. The patient is in consideration for elective pericardiectomy.

DISCUSSION

Acute pericarditis is a frequent cause of acute chest pain in young age patients. Viral and idiopathic pericarditis account for 90% of the cases [7]. Purulent pericarditis is rarely encountered in the antibiotherapy era, mainly in immunosupressed patients (cancer, diabetes, chronic kidney disease), after cardiac operations or in septicemia [8].

In bacterial purulent pericarditis, Pneumococcus is more commonly associated with contiguous spread from an intrathoracic site, while S. aureus is more often involved in hematogenous spread [8].

Tuberculosis is a common cause of pericarditis in HIV-endemic areas. Pericardial involvement can occur with a primary infection, reactivation of latent infection, and during appropriate antitubercular therapy. Tuberculous pericardial fluid demonstrates many of the characteristics of tuberculous pleural fluid, with acid-fast smears being rarely positive and cultures being positive in approximately 50% of cases. Pericardial biopsy with histologic examination and culture of the affected tissue has a higher diagnostic yield of 70–83% [9]. The ADA levels have a high sensitivity and in appropriate context, like in this case, can indicate tuberculous etiology and further enhance a trial of antituberculosis treatment [10].

ADA levels in the context of pericardial effusion have a potential role in tuberculous pericarditis diagnosis, particularly in endemic countries. When using ADA value >60 U/l it has a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 90%, predictive positive value of 90% with predictive negative value of 100% [11]. In HIV patients, ADA levels also have excellent correlation with tuberculous pericarditis, particularly when a lymphocytic pericardial fluid is present [12].

In our case, pericardial fluid is clearly neutrophilic probably due to S. aureus co-infection, which can limit the diagnosis field. However, it also can illustrate possible co-infections in the appropriate scenario, especially with high ADA levels, HIV infection and poor response to antibiotics but prompt response to tuberculostatic treatment.

Tubercular-bacterial co-infection is challenging and needs to be considered, especially if tuberculosis occurs in atypical pulmonary or extrapulmonary locations in an immunosuppressed patient [13]. In our case, we have a patient that already can be classified as AIDS (low CD4 count and tuberculous infection). Moreover, the diabetes has a potentially role alongside the immunosuppression status in this scenario contributing both for purulent pericarditis and for the co- infection [14].

Although it is known that extrapulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients has a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, tuberculous pericarditis occurs with higher frequency in these individuals. Generally occurs in patients with pronounced imunodepression status and it is not common presenting as first manifestation of HIV infection. It can rise to 30% annual risk in those with advanced immunosuppression [15].

Co-infection with M. tuberculosis is the leading cause of death in individuals infected with HIV-1. It has long been known that HIV-1 infection alters the course of M. tuberculosis infection and substantially increases the risk of active tuberculosis (TB). It has also become clear that TB increases levels of HIV-1 replication, propagation and genetic diversity [16]. In this context, specific defects in host defense, particularly humoral immunity make HIV-1 seropositive individuals particularly susceptible to serious infection of multiple etiologies like our case have demonstrated.

We highlight some particular aspects of this case that are not common in clinical practice. HIV diagnosis was made in the acute setting. Despite the pronounced laboratory immunosuppression status (CD4 conut 28 cells/μl and HIV viral load 347 609 copies/mm3), the patient had no past clinic features of suspected immunosuppression. We hypothesized that this acute atypical presentation is due to possible subclinical symptoms not valued by the patient and by the bacterial co-infection.

In conclusion, this rare case illustrates the importance of rapid recognition and treatment of this fatal condition. It is prudent the consideration for tuberculous infection even if there is no direct evidence, especially in HIV-endemic areas. And finally, the possibility for tubercular-bacterial co-infection in immunosuppressed population like HIV and diabetic patients can be present and demands appropriate treatment.

‘Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images’.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

FUNDING

No funding was obtained.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Hospital ethics committee has approved this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1. Maisch B, Seferović PM, Ristić AD, Erbel R, Rienmüller R, Adler Y, et al. . Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pricardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J 2004;25:587–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M. Evaluation and treatment of pericarditis: a systematic review. JAMA 2015;314:1498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parsons R, Argoud G, Palmer DL. Mixed bacterial infection of the pericardium. South Med J 1983;76:1046–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rubin RH, Moellering RC Jr. Clinical, microbiologic and therapeutic aspects of purulent pericarditis. Am J Med 1975;59:68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mayosi BM, Wiysonge CS, Ntsekhe M, Volmink JA, Gumedze F, Maartens G, et al. . Clinical characteristics and initial management of patients with tuberculous pericarditis in the HIV era: the Investigation of the Management of Pericarditis in Africa (IMPI Africa) registry. BMC Infect Dis 2006;6:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Louw A, Tikly M. Purulent pericarditis due to co-infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a patient with features of advanced HIV infection. BMC Infect Dis 2007;7:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lange RA, Hillis LD. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis [published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 2005;352:1163]. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Permanyer-Miralda G, Sagrista-Sauleda J, Soler-Soler J. Primary acute pericardial disease: a prospective series of 231 consecutive patients. Am J Cardiol 1985;56:623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cherian G. Diagnosis of tuberculous aetiology in pericardial effusions. Postgrad Med J 2004;80:262–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burgess LJ, Reuter H, Carstens ME, Taljaard JJ, Doubell AF. The use of adenosine deaminase and interferon gamma as diagnostic tools for tuberculous pericarditis. Chest 2002;122:900–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cubero GI, Rubin J, Martín M, Rondan J, Simarro E. Pericardial effusion: clinical and analytical parameters clue. Int J Cardiol 2006;108:404–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reuter H, Burgess L, van Vuuren W, Doubell A. Diagnosing tuberculous pericarditis. QJM 2006;99:827–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schleicher GK, Feldman C. Dual infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis in HIV-seropositive patients with community acquired pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003;7:1207–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee HH, Chu CY, Su HM, Lin TH, Voon WC, Lai WT, et al. . Purulent pericarditis, multi-site abscesses and ketoacidosis in a patient with newly diagnosed diabetes: a rare case report. Diabet Med 2014;31:e25–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ntsekhe M, Mayosi BM. Tuberculous pericarditis with and without HIV. Heart Fail Rev 2013;18:367–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bell LCK, Noursadeghi M. Pathogenesis of HIV-1 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis co-infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018;16:80–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].