Abstract

Traditionally, the role of primary care providers (pcps) across the cancer care trajectory has focused on prevention and early detection. In combination with screening initiatives, new and evolving treatment approaches have contributed to significant improvements in survival in a number of cancer types. For Canadian cancer survivors, the 5-year survival rate is now better than it was a decade ago, and the survivor population is expected to reach 2 million by 2031. Notwithstanding those improvements, many cancer survivors experience late and long-term effects, and comorbid conditions have been noted to be increasing in prevalence for this vulnerable population. In view of those observations, and considering the anticipated shortage of oncology providers, increasing reliance is being placed on the primary care workforce for the provision of survivorship care. Despite the willingness of pcps to engage in that role, further substantial efforts to elucidate the landscape of high-quality, sustainable, and comprehensive survivorship care delivery within primary care are required.

The present article offers an overview of the integration of pcps into survivorship care provision. More specifically, it outlines known barriers and potential solutions in five categories:

■ Survivorship care coordination

■ Knowledge of survivorship

■ pcp-led clinical environments

■ Models of survivorship care

■ Health policy and organizational advocacy

Keywords: Survivorship, primary care providers, education

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, the role of primary care providers (pcps) across the cancer care trajectory has focused predominantly on prevention and early detection1. New treatment modalities have contributed to impressive achievements in oncology: the 5-year survival rate for cancer survivors is now better than it was a decade ago, and the survivor population is expected to reach 2 million by 20312. Notwithstanding those triumphs, many cancer survivors experience distressing aftereffects3, and comorbid conditions are increasing in the survivor population4. In view of those observations, and considering the anticipated shortage of oncology providers5, reliance is increasingly being placed on pcps for survivorship care provision6. However, further efforts to elucidate the landscape of high-quality, sustainable, and comprehensive survivorship care delivery within primary care are required7,8.

The present article offers an overview of the integration of pcps into survivorship care provision. More specifically, it outlines known barriers and potential solutions in five categories:

■ Survivorship care coordination

■ Knowledge of survivorship

■ pcp-led clinical environments

■ Models of survivorship care

■ Health policy and organizational advocacy

BARRIERS AND POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

Survivorship Care Coordination

In the first decade of the 2000s, the U.S. Institute of Medicine’s Lost in Transition report promoted the value of pcps in the delivery of comprehensive follow-up care to cancer survivors and recommended the provision of survivorship care plans (scps) to the primary care workforce for patients who had reached treatment completion9. To date, deficits in survivorship care coordination remain unresolved, including suboptimal communication between oncology providers and pcps10 and poorly defined pcp roles in survivorship care delivery11. Moreover, current evidence appears divided on the question of whether scps are beneficial to pcps12.

With respect to communication, evidence has revealed mutual communication gaps between oncology providers and pcps13. Those communication issues might be influenced in part by organizational culture, institutional practice preferences, financial incentives, and availability of management support14. Communication issues can also arise because of poor role definition for pcps in cancer care1,11. In a study from Easley et al.11, health care providers were asked to describe what the role of pcps in cancer care provision should be. Respondents—including pcps, surgeons, medical and radiation oncologists, and general practitioners in oncology (gpos)—described that role as “quarterback” or team leader responsible for cancer care coordination, provision of psychosocial support, and management of comorbid conditions, which differed greatly from the actual pcp role. Expectations concerning the survivorship care provider role also differ between patients, pcps, and oncologists1. Thus, further research exploration is warranted to better define the roles taken by pcps in survivorship.

Lastly, pcps appear to value scps, indicating their usefulness in providing information about cancer regimens, late and long-term effects, and follow-up care recommendations. The scp is also viewed as a helpful tool to improve care coordination with the oncology workforce15,16. Notwithstanding those benefits, concerns about cost-effectiveness and resource limitations have been described as barriers to scp implementation17. Perhaps of even greater importance, current evidence to demonstrate that scps improve the survivorship care delivered by pcps and the health outcomes of cancer survivors is lacking18. Future work in this area should go beyond the aim of providing scps to pcps and should focus on the identification of actionable cancer follow-up information that can be readily integrated into primary care practice, which might in turn lead to improved patient outcomes19.

Knowledge of Survivorship

Previous studies have shown that pcps follow patients during active treatment as well as after treatment completion7,20. Ensuring that pcps have core competencies in survivorship, which in part comprise surveillance for recurrence, screening, management of late and long-term effects, and health promotion interventions, cannot be overstated21 (Table I). However, pcps are often unaware of the specific concerns and surveillance needs of cancer survivors22,23. Moreover, previous studies suggest that pcps have low levels of confidence about survivorship care provision, reporting lack of knowledge as a key factor23–26. Educating the primary care workforce about survivorship should therefore take upmost precedence6.

TABLE I.

Core competenciesa

| Topic | Competencies |

|---|---|

Survivorship

| |

Surveillance

| |

Long-term and late effects

| |

Health promotion and disease prevention

| |

Psychosocial care

| |

Childhood and adolescent-and-young-adult (AYA) cancer survivors

| |

Older adult cancer survivors

| |

Caregivers of cancer survivors

| |

Communication and coordination of care

| |

In recent years, commendable initiatives have been developed to make survivorship training and educational resources available to pcps. Online platforms such as British Columbia’s Family Practice Oncology Network (http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/health-professionals/networks/familypractice-oncology-network), which houses information about online and in-person training opportunities and resources, could serve as an excellent source for pcps. Other examples of useful online resources include those from Cancer Care Ontario (https://archive.cancercare.on.ca/toolbox/qualityguidelines/clin-program/survivorship) and CancerCare Manitoba (https://www.cancercare.mb.ca/For-Health-Professionals/follow-up-care-resources), which host repositories of select survivorship care recommendations. Nonetheless, current resources remain sparse, and further implementation of survivorship education at the postgraduate and continuing medical education levels is critical6.

Programs should put emphasis on describing the key providers involved in survivorship care delivery and foster a culture of collaboration through educational interspecialty offerings. Interspecialty education, which can improve communication and collaboration between providers, benefiting patient safety, cost of care, and resource management, could help to close care coordination gaps between oncologists and pcps27,28. An innovative example is Moving Forward After Cancer: A Learning Suite for Family Medicine and Oncology Postgraduate Trainees (https://www.cpd-umanitoba.com/courses/moving-forwardafter-cancer), designed to communicate, to an audience of postgraduate family medicine and oncology trainees, best practices in the transition of cancer patients to primary care. Other selected educational resources are listed in Table II.

TABLE II.

Selected education resources and tools for primary care providers (PCPs)

Canadian Association of General Practitioners in Oncology (CAGPO)

|

Cancer Care Ontario (CCO)

|

BC Cancer

|

CancerCare Manitoba

|

Foundation for Medical Practice Education and McMaster University collaboration

|

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)

|

Cancer Survivorship E-Learning Series

|

UpToDate

|

Reprinted from Shapiro et al.21, with permission.

Universities and professional associations across Canada should partner to develop and disseminate standardized evidence-based survivorship education programs. Those activities should be integrated into residency curricula and continuing medical education activities for pcps in active practice. Lastly, in addition to providing expert survivorship content, the proposed programs should be embedded into established social cognitive frameworks that promote tangible changes in the clinical behaviours of pcps, which might lead to enhanced survivorship care delivery29.

PCP-Led Clinical Environments

Several factors have been reported as hindrances to the provision by pcps of comprehensive care to cancer survivors. First, on treatment completion, pcps report inadequate receipt of information from oncology providers7,8. Second, the primary care workforce values provision of survivorship guidelines to steer their care30. Considerable progress has been made in developing survivorship guidelines for pcps, such as those for breast31, colorectal32, prostate33, and head-and-neck cancers34. Although being exhaustive in survivorship information that was not readily available prior, many of the guideline recommendations are not currently supported by strong evidence6. Similarly, given the rapid advances in the field of oncology, the long-term sequelae of newer cancer agents are currently unknown35. Third, a recent study published by Rubinstein et al. suggests that the absence of cancer survivorship as a distinct clinical category (comparable to diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) might be a barrier to the provision of comprehensive survivorship care in primary care settings. In the absence of such recognition, survivorship care remains poorly defined, likely contributing to the lack of actionable care strategies and follow-up algorithms geared to pcps for the optimal follow-up of cancer survivors19. Lastly, current health information systems might not be adequately suited to the implementation of population-level survivorship interventions19. Further measures to identify actionable interventions in survivorship care should therefore be prioritized and serve to inform the provision of care to cancer survivors. Additionally, together with identification of actionable interventions, endorsement of survivorship as a distinct category and optimization of current information systems might facilitate the implementation of high-quality survivorship provision by the primary care workforce19.

Models of Survivorship Care

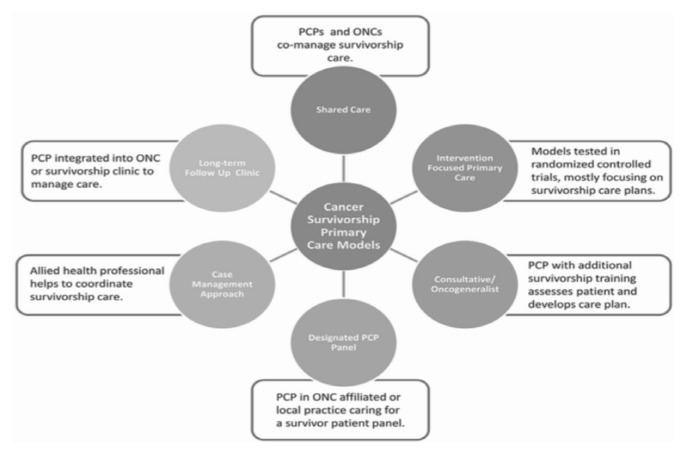

Since about 2010 or so, numerous models for the provision of survivorship care have been developed36, including risk-stratification and chronic care models, to name a few. In risk-stratification models, a shared-care approach between oncology and primary care is adopted based on patients having been categorized into low-, moderate-, or high-risk categories37. Chronic care models for survivorship delivery draw from previously described care models for chronic diseases such as congestive heart failure and diabetes38, which promote self-management interventions. Despite the significant work accomplished to create and evaluate the implementation of those various models, evidence about their effectiveness is scant35. No universal model of survivorship care exists, because such care must be adapted to targeted survivors, the local context, and available resources. Nonetheless, existing models for survivorship share one commonality: they include primary care professionals as key providers of survivorship care, reinforcing the importance of strategic interventions to optimize the integration of pcps into the follow-up care of cancer survivors (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Models of care. Reproduced from Nekhlyudov et al.6, with permission of Lancet Publishing Group in the format journal or magazine via Copyright Clearance Center. PCP = primary care provider; ONC = oncologist.

Many cancer survivors also have common comorbid conditions alongside specific physical and psychosocial needs such as pain, peripheral neuropathy, lymphedema, social role disruption, and fear of recurrence, among others. Comprehensive survivorship care could be optimally provided using an interdisciplinary primary care team approach comprising social services, psychology, nutrition, and other allied health professionals. Interdisciplinary teams are being increasingly relied on for the delivery of primary care39. An interdisciplinary primary care team approach might be favoured by patients and providers40,41, could help to improve health outcomes and management of chronic diseases42,43, and might enhance quality of care and resource use while lessening care fragmentation40. Moreover, the inclusion of gpos, also called onco-generalists, in interdisciplinary primary care teams could help to broaden the receptivity of oncologists for transitioning patients to primary care and optimize collaborations between involved providers6. The gpos might also serve as survivorship expert resources to pcps, contributing to survivorship knowledge enhancement for interdisciplinary primary care teams by actively participating in teaching activities6.

Health Policy and Organizational Advocacy

Key actions from policymakers and advocacy stakeholders are required to support the integration of pcps into survivorship care delivery. First, health-governing agencies must invest in awareness campaigns promoting the value of pcps in survivorship care provision at the population level. Although cancer survivors identify the pcp as one of their survivorship providers (namely, for help with fear of recurrence and adjustment to their “new normal” after treatment44,45), their confidence in the competency of the pcp to provide cancer-specific follow-up care appears low46. Moreover, given that follow-up care was traditionally entrusted to oncology specialists, some cancer survivors might be unaware of pcp contributions to survivorship care delivery46. A better understanding by cancer survivors of the pcp’s expected role might bolster the integration of these important providers into survivorship care provision.

Second, given that pcps report the value of guidelines as tools in survivorship care provision7, optimization of current guidelines to reflect high-quality evidence-based interventions in the primary care setting are warranted6. Endorsement of survivorship as a distinct clinical category, together with utilization of data from electronic medical records, could aid in such guideline optimization. It could also facilitate the creation of electronic medical record–based decision aids and reminders to guide pcps and promote a comprehensive approach to cancer survivors, which is particularly important for survivors presenting with comorbid conditions19. Additionally, a statement of financial compensation to pcps for survivorship care provision, as for other interventions performed throughout the cancer continuum (such as screening for cancers), could give much-needed recognition and visibility to survivorship care within primary care settings19.

Finally, advocacy for research funding to pursue rigorous evaluation of survivorship care models that go beyond quality-of-care outcomes to include assessment of program structure; access to psychosocial, fertility, and rehabilitation services; and cost analysis outcomes are compulsory to elucidate programs capable of providing comprehensive high-quality survivorship care that is resource-effective and financially sustainable47. All the foregoing actions are of paramount importance to optimize pcp-led survivorship care delivery19.

SUMMARY

Primary care providers play a key role in the care of cancer survivors. Despite significant advances, further extensive work is required to pave the road toward optimal integration of the primary care workforce into survivorship care delivery. Pressing investments from academic institutions and professional associations to create and disseminate standardized survivorship education across Canada are warranted. Recognition of survivorship as a distinct clinical category by policymakers and key stakeholders is compulsory: such validation will ultimately ensure the establishment of high-quality and sustainable survivorship care delivery in primary care.

Key Points

■ Primary care providers are key players in survivorship care delivery.

■ The development of evidenced-based survivorship education programs is a priority agenda item for the optimal care of cancer survivors.

■ The endorsement of survivorship as a distinct clinical category by policymakers is critical to the establishment of high-quality and sustainable survivorship care provision by the primary care workforce.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors give their heartfelt thanks to Tristan Williams for the formatting and final preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

This series is brought to you in partnership with the Canadian Association of General Practitioners in Oncology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, Cook EF, Earle CC. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2489–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2017. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (cpac) Sustaining Action Toward a Shared Vision: 2012–2017 Strategic Plan. Toronto, ON: cpac; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leach CR, Weaver KE, Aziz NM, et al. The complex health profile of long-term cancer survivors: prevalence and predictors of comorbid conditions. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:239–51. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, Bruinooge S, Goldstein M. Future supply and demand for oncologists: challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nekhlyudov L, O’Mal ley DM, Hudson SV. Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: gaps in evidence and future opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e30–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sussman J, Bainbridge D, Evans WK. Towards integrating primary care with cancer care: a regional study of current gaps and opportunities in Canada. Healthc Policy. 2017;12:50–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaput G, Kovacina D. Assessing the needs of family physicians caring for cancer survivors. Montreal survey. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(suppl 1):S18. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewitt ME, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantsiper M, McDonald E, Geller G, Shockney L, Snyder C, Wolff A. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):S459–66. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Easley J, Miedema B, O’Brien MA, et al. on behalf of the Canadian Team to Improve Community-Based Cancer Care Along the Continuum. The role of family physicians in cancer care: perspectives of primary and specialty care providers. Curr Oncol. 2017;24:75–80. doi: 10.3747/co.24.3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobsen PB, DeRosa AP, Henderson TO, et al. Systematic review of the impact of cancer survivorship care plans on health outcomes and health care delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2088–100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.7482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis RA, Neal RD, Hendry M, et al. Patients’ and health-care professionals’ views of cancer follow-up: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:e248–59. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X453576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fennell ML, Das IP, Clauser S, Petrelli N, Salner A. The organization of multidisciplinary care teams: modeling internal and external inf luences on cancer care quality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:72–80. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rushton M, Morash R, Larocque G, et al. Wellness Beyond Cancer Program: building an effective survivorship program. Curr Oncol. 2015;22:e419–34. doi: 10.3747/co.22.2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donohue S, Sesto ME, Hahn DL, et al. Evaluating primary care providers’ views on survivorship care plans generated by an electronic health record system. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e329–35. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.003335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennan ME, Gormally JF, Butow P, Boyle FM, Spillane AJ. Survivorship care plans in cancer: a systematic review of care plan outcomes. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1899–908. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boekhout AH, Maunsell E, Pond GR, et al. on behalf of the fupii trial investigators. A survivorship care plan for breast cancer survivors: extended results of a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:683–91. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubinstein EB, Miller WL, Hudson SV, et al. Cancer survivorship care in advanced primary care practices: a qualitative study of challenges and opportunities. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1726–32. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollack LA, Adamache W, Ryerson AB, Eheman CR, Richardson LC. Care of long-term cancer survivors: physicians seen by Medicare enrollees surviving longer than 5 years. Cancer. 2009;115:5284–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shapiro CL, Jacobsen PB, Henderson T, et al. ReCAP: asco core curriculum for cancer survivorship education. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:145, e108–17. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, et al. Caring for cancer survivors: a survey of primary care physicians. Cancer. 2009;115(suppl):4409–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sima JL, Perkins SM, Haggstrom DA. Primary care physician perceptions of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:118–24. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carver JR, Shapiro CL, Ng A, et al. on behalf of the asco Cancer Survivorship Expert Panel. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical evidence review on the ongoing care of adult cancer survivors: cardiac and pulmonary late effects. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3991–4008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against her2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses her2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bovelli D, Plataniotis G, Roila F on behalf of the esmo Guidelines Working Group. Cardiotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents and radiotherapy-related heart disease: esmo clinical practice guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 5):v277–82. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine SA, Chao SH, Brett B, et al. Chief resident immersion training in the care of older adults: an innovative interspecialty education and leadership intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1140–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kutner JS, Westfall JM, Morrison EH, Beach MC, Jacobs EA, Rosenblatt RA. Facilitating collaboration among academic generalist disciplines: a call to action. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:172–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Légaré F, Freitas A, Turcotte S, et al. Responsiveness of a simple tool for assessing change in behavioral intention after continuing professional development activities. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, Piliotis E, Verma S. Primary care physicians’ views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3338–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sisler J, Chaput G, Sussman J, Ozokwelu E. Follow-up after treatment for breast cancer. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62:805–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Shami K, Oeffinger KC, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society colorectal cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:428–55. doi: 10.3322/caac.21286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen EE, LaMonte SJ, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society head and neck cancer survivorship care guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:203–39. doi: 10.3322/caac.21343. [Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:351] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skolarus TA, Wolf AM, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobs LA, Shulman LN. Follow-up care of cancer survivors: challenges and solutions. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e19–29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobs LA, Vaughn DJ. In the clinic. Care of the adult cancer survivor. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:ITC6–1. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-01006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCabe MS, Partridge AH, Grunfeld E, Hudson MM. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;40:804–12. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wranik WD, Haydt SM, Katz A, et al. Funding and remuneration of interdisciplinary primary care teams in Canada: a conceptual framework and application. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:351. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2290-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez HP, Rogers WH, Marshall RE, Safran DG. Multidisciplinary primary care teams: effects on the quality of clinician-patient interactions and organizational features of care. Med Care. 2007;45:19–27. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000241041.53804.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drew P, Jones B, Norton D. Team effectiveness in primary care networks in Alberta. Healthc Q. 2010;13:33–8. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2010.21813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferrante JM, Balasubramanian BA, Hudson SV, Crabtree BF. Principles of the patient-centered medical home and preventive services delivery. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:108–16. doi: 10.1370/afm.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willens D, Cripps R, Wilson A, Wolff K, Rothman R. Inter-disciplinary team care for diabetic patients by primary care physicians, advanced practice nurses, and clinical pharmacists. Clin Diabetes. 2011;29:60–8. doi: 10.2337/diaclin.29.2.60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoekstra RA, Heins MJ, Korevaar JC. Health care needs of cancer survivors in general practice: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nyarko E, Metz JM, Nguyen GT, Hampshire MK, Jacobs LA, Mao JJ. Cancer survivors’ perspectives on delivery of survivorship care by primary care physicians: an Internet-based survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:143. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0367-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayer DK, Nasso SF, Earp JA. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e11–18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30573-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halpern MT, Argenbright KE. Evaluation of effectiveness of survivorship programmes: how to measure success? Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e51–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30563-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]