Abstract

Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection is the most frequent infection worldwide and it has been postulated that it predisposes to multiple enteric pathogens and diarrheal diseases. Salmonella infection is common in tropical and under developed communities and is associated with wide range of diseases from gastroenteritis to typhoid fever. This study aimed at detecting the impact of H pylori infection on the incidence of salmonella infections.

The study participants were sampled from cohorts of patients in four university hospitals in different Egyptian Governorates. Their age ranged from 20 to 59 years and followed up for a rising Widal test. Case patients (n = 109) were subjects who visited the outpatient clinic because of diarrhea and typhoid like illness. They were either positive for H pylori stool antigen (n = 53) or negative to it (n = 56). All patients were subjected to thorough history taking, clinical examination, routine laboratory investigations, abdominal ultrasonography, H pylori stool antigen detection, and serial Widal test assay.

The proportion of salmonella-infected subjects was lower among case patients with H pylori infection (22.6%) than among those negative for H pylori (33.9%) albeit not statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.24–1.33; P = .21). The association persisted nonsignificant after adjusting for sociodemographic variables (adjusted OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.18–1.39; P = .18). In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for sex, dietary habits, socioeconomic status, and educational level subjects who eat outdoors were associated with a significantly greater risk of salmonella typhi infection.

Our findings suggest that there is no association between H pylori infection and salmonella infection in patients presented with typhoid fever or typhoid like illness.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, salmonella, Widal test

1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection is the most frequent infection worldwide and it has been postulated that it predispose to salmonella infection.[1] The stomach acidity is considered an important nonspecific barrier against the colonization of enteric pathogens into the gut,[2,3] and hypochlorhydria can predispose to increased risk of diarrheal diseases.[4] Consequently, it was proposed that H pylori infection might increase the risk of diarrheal diseases and enteric infections. Furthermore, several studies have concluded an increased risk for diarrheal diseases in relation to H pylori infection.[5–9] A Gambian case–control study in children demonstrated greater H pylori seropositivity (53%) among children with chronic diarrhea compared with 26% in controls without chronic diarrhea (P = .01).[5]

A study in Bangladesh showed that H pylori infection was associated with a 1.6-fold increased risk of life-threatening cholera.[6] A follow-up study from Peru showed that H pylori seroconversion in children was followed by a slight but significant increase in the risk of diarrheal diseases.[7] Further studies supported these observations with shigellosis[8] and typhoid fever.[9] On the other hand, other studies could not demonstrate such relation[10,11] and several studies from Germany[12,13] and the United States[14] showed inverse association between H pylori infection and diarrheal diseases. Given these controversies, we designed the current cross-sectional observational study to examine the impact of H pylori infection on the incidence of salmonella infections.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design

Cross sectional observational study.

2.2. Patients

Patients were enrolled from outpatient gastroenterology clinics of Zagazig, Kafrelsheikh, and Tanta University Hospitals, and Alexandria Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University, Egypt during the period from September 2017 to January 2018.

H pylori infection: is defined in this study when the patient was positive or negative for H pylori antigen in stool provided that he did not receive any PPI or antibiotics in the last 4 weeks prior to the examination.[15,16]

Salmonellosis: in this study rising Widal test over 1 week period was used to diagnose salmonella infection with titre more than 1/160 was considered significant.[14]

Diarrhea: was defined as passage of at least 3 loose stools in a 24-h period, based on the patients’ self-report in the event questionnaire.

Typhoid like illness: was suspected when the patient presented with a gradual onset of a high fever over several days; weakness, abdominal pain, constipation, and headaches also commonly occur and may be diarrhea.[17]

A case patient was defined as a subject who visited the outpatient clinic with a complaint of diarrhea and/or typhoid like illness. Patients who agreed gave a written informed consent for participation in the study and for performing all labs needed. One hundred and nine patients were enrolled and were assigned into two groups according to their H pylori status: group I H pylori positive group and group II, the H pylori negative group.

A visit to outpatient clinic due to diarrheal episodes involved obtaining stool samples that were examined for H pylori antigen and blood sample for baseline Widal test.

H pylori antigen in stool (On Site H. Pylori Ag Rapid Test, CTK Biotech, San Diego, CA). It is a lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay for qualitative assessment of H pylori antigens depending on the use of monoclonal antibodies against H pylori conjugated with colloid gold. Positive cases were marked with two bands of color changes (one test band and one control band).[14]

Widal test: qualitative slide and semiquantitative tube agglutination methods were done using febrile antigen kits of Salmonella typhi (Chromatest Febrile Antigens Kits, Linear Chemicals, Spain).

Both infections were treated according to the current guidelines.

Sociodemographic variables information was obtained on: age, level of education, socioeconomic status, and dietary habits.

2.3. Exclusion criteria

Patients with these conditions were excluded from the study: chronic diseases, for example, diabetes, renal failure, cirrhosis, patients with malignancy, patients on PPIs, antibiotics intake within 1 month before being enrolled in the study, recent vaccination for typhoid fever, other causes of fever and other organ specific infections with localizing sign and symptoms like UTI and RTI, etc., and those who did not agree with written informed consent to participate in the study.

3. Statistical analysis

Data were checked, entered, and analyzed using SPSS version 20 for data processing and statistic. Data were expressed as number and percentage for qualitative variables. P value of <.05 indicates significant results. Comparison between the two groups was done using Chi square tests.

4. Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee. All patients gave a written informed consent for participating in the study and for performing all relevant interventions. The study protocol was adherent to practice guidelines and declaration of Helsinki.

5. Results

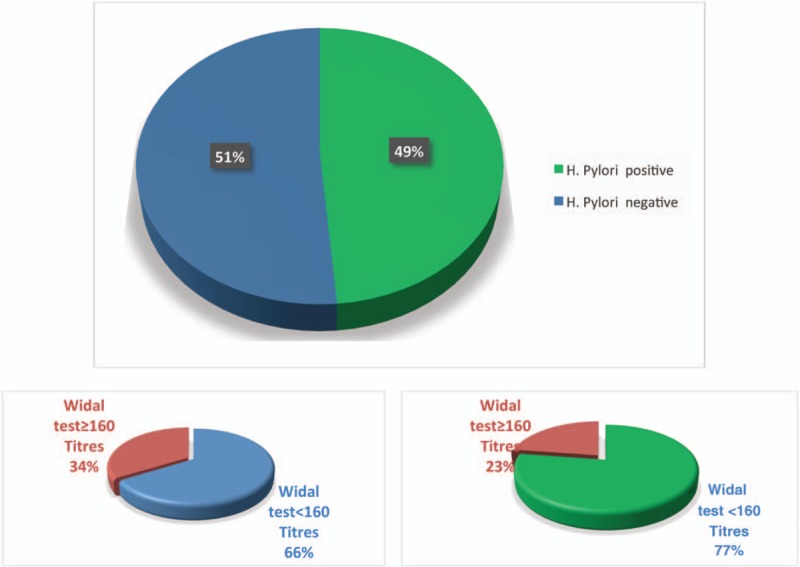

One hundred and nine patients were enrolled. Group I comprised 53 patients with confirmed H pylori infection using the readily available H pylori stool antigen after adequate precautions and preparation, while groups II comprised 56 patients who were negative for H pylori stool antigen. The proportion of salmonella-infected subjects was lower among case patients with H pylori infection (22.6%) than among those negative for H pylori (33.9%) (Fig. 1) albeit not statistically significant (odds ratio [OR], 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.24–1.33; P = .21) as shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The proportion of salmonella-infected subjects among case patients with H pylori infection and those without.

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of association between Helicobacter pylori infection and Salmonella diseases.

The association persisted nonsignificant after adjusting for sociodemographic variables (adjusted OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.18–1.39; P = .18). In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, sex, dietary habits, socioeconomic status, and educational level subjects who eat outdoors were associated with a significantly greater risk of salmonella typhi infection.

6. Discussion

H pylori is the most prevalent worldwide infection mainly in developing countries. Moreover, salmonella infection is very common infection especially in tropical and subtropical communities. Both infections still bear common features beyond the prevalence including the common oral route of infection. Furthermore, both infections are good examples of persistent infections. H pylori inhabit the human gastric mucosa with the infection mostly acquired during childhood and persistence of the infection can be lifelong. Salmonella causes systemic infections that involve colonization of the reticuloendothelial system and some individuals become lifelong carriers of the organism.[18]

Gastric acidity is an important natural barrier against enteric infections.[19] It is known that H pylori infection is associated with hypochlorhydria during both acute and chronic infection. Consequently, reduced acidity and inflammatory changes in the stomach may predispose the host to an increase in the frequency of enteric infections including salmonella infection. This was the assumption that triggered the current study together with some emerging epidemiologic evidence of an association between H pylori infection and salmonella infection.[20]

In the current study H pylori prevalence in the study sample was 48.6% (53/109) which is consistent with prevalence rates reported in previous studies ranging from 30.6% to 74.4% and the infection is common in low socioeconomic status. The same class is more vulnerable to salmonella infection as shown in previous studies.[20,21]

In this study stool antigen test is used for diagnosis of H pylori infection because it is readily available and cheap when compared with urea breath test and it is the commonly used H pylori test in our daily practice. In fact the accuracy of stool antigen test for diagnosis of H pylori infection had been accepted among clinicians both in the local Egyptian literature and also at international level.[20,22]

However, an association between prevalence of H pylori and salmonella have not been confirmed in the current study. And this may reinforce some evidence that H pylori colonization may be protective against some infection. This has been shown in one study.[23] The authors of this study concluded that H pylori is protective against bacterial diarrhea in children and H pylori eradication should be carefully revised.

Also, another study from Indonesia suggested that a common risk of environmental exposure to both bacteria, for example, poor hygiene, rather than a causal relationship via reduced gastric acid production is the common link in between.[24]

This study had its limitations. First, is the use of Widal test in diagnosis of salmonella infection. In fact Widal test has been correlated with culture results in some studies.[25] Another rationale is the lack of culture facility for every suspected case in the developing countries. In fact, Widal test examination is the real-life daily practice and its choice is a mirror image to actual circumstances practiced in the underdeveloped and poor communities. Second, is the small sample size. Third, lack of the follow up. Another study with longer follow up may answer the question, is there a difference in the natural history of both infections in the context of co-infection. Fourth, other confounders including many environmental and genetic factors were not studied and this because we intended to highlight, for the first time, in the Egyptian community, the association between both infections.

In conclusion, it seems that there is no association between H pylori infection and salmonella infection in patients presented with typhoid fever or typhoid like illness.

Acknowledgments

The authors would thank all colleagues who helped in conducting this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Rasha I. Salama, Sherein Mohamed Alnabawy.

Data curation: Rasha I. Salama, Mariam Salah Zaghloul.

Formal analysis: Mariam Salah Zaghloul.

Investigation: Rasha I. Salama, Mariam Salah Zaghloul.

Methodology: Rasha I. Salama, Mariam Salah Zaghloul.

Project administration: Mohamed H. Emara.

Validation: Mohamed H. Emara, Mariam Salah Zaghloul.

Visualization: Mohamed H. Emara.

Writing – original draft: Mohamed H. Emara, Mariam Salah Zaghloul.

Writing – review & editing: Mohamed H. Emara, Hanan M. Mostafa, Sherief Abd-Elsalam, Sherein Mohamed Alnabawy, Samah A. Elshweikh, Mariam Salah Zaghloul.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, H pylori = Helicobacter pylori, OR = odds ratio.

Funding: None

Conflict of interest: The authors have none to declare.

Current Knowledge: H pylori is prevalent.

New: H pylori did not predispose to salmonella.

References

- [1].King CC, Chen CJ, You SL, et al. Community-wide epidemiological investigation of a typhoid outbreak in a rural township in Taiwan, Republic of China. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18:254–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Giannella RA, Broitman SA, Zamcheck N. Gastric acid barrier to ingested microorganisms in man: studies in vivo and in vitro. Gut 1972;13:251–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gilman RH, Partanen R, Brown KH, et al. Decreased gastric acid secretion and bacterial colonization of the stomach in severely malnourished Bangladeshi children. Gastroenterology 1988;94:1308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chang AH, Haggerty TD, de Martel C, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on symptoms of gastroenteritis due to enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in adults. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:457–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sullivan PB, Thomas JE, Wight DG, et al. Helicobacter pylori in Gambian children with chronic diarrhoea and malnutrition. Arch Dis Child 1990;65:189–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Clemens J, Albert MJ, Rao M, et al. Impact of infection by Helicobacter pylori on the risk and severity of endemic cholera. J Infect Dis 1995;171:1653–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Passaro DJ, Taylor DN, Meza R, et al. Acute Helicobacter pylori infection is followed by an increase in diarrheal disease among Peruvian children. Pediatrics 2001;108:E87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shmuely H, Samra Z, Ashkenazi S, et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with Shigella gastroenteritis in young children. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:2041–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bhan MK, Bahl R, Sazawal S, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and increased risk of typhoid fever. J Infect Dis 2002;186:1857–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Isenbarger DW, Bodhidatta L, Hoge CW, et al. Prospective study of the incidence of diarrheal disease and Helicobacter pylori infection among children in an orphanage in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;59:796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rahman MM, Mahalanabis D, Sarker SA, et al. Helicobacter pylori colonization in infants and young children is not necessarily associated with diarrhoea. J Trop Pediatr 1998;44:283–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rothenbacher D, Blaser MJ, Bode G, et al. Inverse relationship between gastric colonization of Helicobacter pylori and diarrheal illnesses in children: results of a population-based cross-sectional study. J Infect Dis 2000;182:1446–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bode G, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori colonization and diarrhoeal illness: results of a population-based cross-sectional study in adults. Eur J Epidemiol 2001;17:823–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Perry S, Sanchez L, Yang S, et al. Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastroenteritis. J Infect Dis 2004;190:303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Emara MH, Salama RI, Salem AA, et al. Demographic, endoscopic and histopathologic features among stool H. pylori positive and stool H. pylori negative patients with dyspepsia. Gastroenterology Res 2017;10:305–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Manes G, Balzano A, Iaquinto G, et al. Accuracy of the stool antigen test in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection before treatment and in patients on omeprazole therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Newton AE. 3 Infectious Diseases Related To Travel. CDC Health Information for International Travel, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ng KM, Ferryeyra JA, Higginbottom SK, et al. Microbiota-liberated host sugars facilitate post-antibiotic expansion of enteric pathogens. Nature 2013;502:96–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Giannella RA, Broitman SA, Zamcheck N. Influence of gastric acidity on bacterial and parasitic enteric infections: a perspective. Ann Int Med 1973;78:271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Butcher JG. Getting into trouble: the diaspora of Thai trawlers, 1965–2002. Int J Maritime History 2002;14:85–121. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ali S, Vollaard AM, Widjaja S, et al. PARK2/PACRG polymorphisms and susceptibility to typhoid and paratyphoid fever. Clin Exp Immunol 2006;144:425–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sabbagh P, Mohammadnia-Afrouzi M, Javanian M, et al. Diagnostic methods for Helicobacter pylori infection: ideals, options, and limitations. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019;38:55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Monajemzadeh M, Abbasi A, Tazifi P, et al. The relation between Helicobacter pylori infection and acute bacterial diarrhea in children. Int J Pediatr 2014;2014:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Vollaard AM, Verspaget HW, Ali S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and typhoid fever in Jakarta, Indonesia. Epidemiol Infect 2006;134:163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chowdhury MAY, Haque MG, Karim AMMR. Value of Widal test in the diagnosis of typhoid fever. Med Today 2015;27:28–32. [Google Scholar]