Abstract

Background:

Police officers in the New Orleans geographic area faced a number of challenges following Hurricane Katrina.

Aim:

This cross-sectional study examined the effect of social support, gratitude, resilience and satisfaction with life on symptoms of depression.

Method:

A total of 86 male and 30 female police officers from Louisiana participated in this study. Ordinary least-square (OLS) regression mediation analysis was used to estimate direct and indirect effects between social support, gratitude, resilience, satisfaction with life and symptoms of depression. All models were adjusted for age, alcohol intake, military experience and an increase in the number of sick days since Hurricane Katrina.

Results:

Mean depressive symptom scores were 9.6 ± 9.1 for females and 10.9 ± 9.6 for males. Mediation analyses indicates that social support and gratitude are directly associated with fewer symptoms of depression. Social support also mediated the relationships between gratitude and depression, gratitude and satisfaction with life, and satisfaction with life and depression. Similarly, resilience mediated the relationship between social support and fewer symptoms of depression.

Conclusion:

Social support, gratitude and resilience are associated with higher satisfaction with life and fewer symptoms of depression. Targeting and building these factors may improve an officer’s ability to address symptoms of depression.

Keywords: Depression, gratitude, Hurricane Katrina, police, resilience, social support

Introduction

Following a natural disaster, individuals often report feelings of depression (Bernard, Driscoll, Kitt, West, & Tak, 2006; Davidson & McFarlane, 2006; Pietrzak et al., 2012). Rates of depression in police officers are higher than those reported in the general population, partially due to their responsibilities during and after natural disasters (Bernard et al., 2006; West et al., 2008). Although specific protective factors such as social support, gratitude, resilience and satisfaction with life mitigate these symptoms, how these factors may interact with each other to promote positive or reduce negative outcomes is less well understood. Evaluating these relationships in officers who have experienced a hurricane may shed light on how they interact and whether the interactions are associated with fewer symptoms of depression or higher levels of satisfaction with life.

Hurricanes leave physical and psychological destruction in their wake. Hurricane Katrina caused substantial damage when it hits the central Gulf Coast of the United States in 2005, resulting in over 1,200 deaths and 108 billion dollars in property damage (Knabb, Rhome, & Brown, 2011). Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama experienced wind speeds of over 100 miles/h and levee failure in New Orleans resulted in approximately 80% of the city being under water at some point during the hurricane. Similarly, due to storm surge, Alabama and Mississippi also experienced severe flooding. Although a number of these regions were evacuated during and after Hurricane Katrina, police officers were expected to stay and work (Adams & Turner, 2014; West et al., 2008). They were responsible for crowd control, removing bodies, search and rescue (Baum, 2006; Bernard et al., 2006; West et al., 2008). Due to the devastation, loss of electricity and flooding, police officers worked out of temporary offices with little to no communication with coworkers in an often openly hostile environment while trying to ensure the safety and well-being of their own families (Adams & Turner, 2014; Baum, 2006; West et al., 2008). As a result of the stress associated with this work, some police officers experienced symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression (West et al., 2008). PTSD is one of the most common psychological disorders following a natural disaster; however, depression occurs in approximately 37% of individuals (Davidson & McFarlane, 2006). A longitudinal study that evaluated the prevalence of PTSD and depression following Hurricane Ike found that while PTSD symptoms decreased over time, levels of depression remained the same (Pietrzak et al., 2012). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health conducted a health hazard evaluation after Hurricane Katrina and reported that 26% of police officers who worked during or after Hurricane Katrina reported symptoms of depression (Bernard et al., 2006). These results suggest that following natural disasters, depression may be a more problematic and persistent psychological issue than PTSD.

Following a natural disaster, individual characteristics, the level of morbidity and exposure level are all factors that may increase an individual’s risk of physical and psychological sequelae (Davidson & McFarlane, 2006; Weems et al., 2007). Among New Orleans’ police officers, symptoms of depression were associated with having little contact with family, a family member who was injured, a home that was uninhabitable, being injured as a result of an assault or being isolated from coworkers and work (West et al., 2008). Although most research has focused on risk factors associated with depression, factors that may act to protect officers from symptoms of depression are also important. For example, in individuals who suffer from recurrent depression, positive psychological factors such as gratitude, hope and self-forgiveness were associated with greater happiness and fewer symptoms of depression (Macaskill, 2012). What factors may be protective in police officers is not well understood. The broaden-and-build theory asserts that positive emotions extend momentary thought-action repertoires; individuals who experience positive emotions are more likely to engage in positive behaviors, think more creatively and flexibly, as well as seek out personal resources compared to those who are experiencing negative emotions (Fredrickson, 2004,2013). Research suggests that positive factors such as social support, gratitude, resilience and satisfaction with life may work either independently or together to mitigate symptoms of depression in officers. To clarify these relationships, we evaluated social support, resilience, gratitude, satisfaction with life and depression in a number of mediation models. The first two mediation models that we evaluated were based on previous research (McCanlies, Gu, Andrew, Burchfiel, & Violanti, 2017; Wood, Maltby, Gillett, Linley, & Joseph, 2008). The final two models were selected to extend our understanding of the relationships between gratitude, satisfaction with life, social support and symptoms of depression observed in the first two models.

Social support is the perception or feeling that one has emotional or financial support (Cohen & Hoberman, 1983; Santos et al., 2013). Furthermore, social networks and social connectivity are associated with positive emotions and well-being and have been shown to be associated with positive mental health. Following a stroke, individuals may experience post-stroke depression; however, individuals who were engaged socially were less likely to experience symptoms of depression compared to those who were not socially engaged (Volz, Möbus, Letsch, & Werheid, 2016). Similarly, individuals whose illness interferes with their ability to engage in social activities are more likely to report symptoms of depression (Simning, Seplaki, & Conwell, 2016). Lower levels of depression are associated with positive emotions and well-being, which are associated with social support (Santos et al., 2013; Simning et al., 2016; Volz et al., 2016). These studies indicate the importance of social interaction in mitigating or preventing depression. Research also suggests that social support is associated with gratitude and resilience, which are also associated with lower levels of depression (Pietrzak et al., 2010; Wood et al., 2008). However, how social support may directly or indirectly affect factors such as gratitude, satisfaction with life and symptoms of depression has not been assessed in police officers.

Resilience is the ability to overcome or adapt to stressful events (Bonanno, 2004). It has been defined as ‘a process to harness resources to sustain well-being’ (Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick, & Yehuda, 2014). Resources, in this case, include hardiness, self-esteem, humor and coping skills (Bonanno, 2004). Cognitive, behavioral and existential factors such as self-care, embracing a personal moral compass, optimism and cognitive flexibility are aspects of resilience that protect against depression (Iacoviello & Charney, 2014; Southwick et al., 2014. In veterans, resilience has been shown to mediate the relationship between military unit support and depression (Pietrzak et al., 2010). In this case, higher unit support was associated with higher resilience, which was associated with lower levels of depression. Other studies have also shown a relationship between resilience or resilient coping and lower levels of depression. Individuals who reported higher personal resiliency were less likely to report symptoms of depression and more likely to report higher satisfaction with life (Smith, Saklofske, Keefer, & Tremblay, 2016). These relationships occur alone and in combination with other factors such as social support, adaptive coping and self-esteem and suggest that resilience may be a good candidate mediator between social support and depression (Gloria & Steinhardt, 2016; Hsieh, Chen, Wang, Chang, & Ma, 2016; Kapikiran & Acun-Kapikiran, 2016; Sinclair, Wallston, & Strachan, 2016).

Gratitude is an expression of appreciation for people or things in one’s life. It is associated with a number of positive traits, including social support, self-esteem and satisfaction with life (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002). Longitudinal analysis shows that gratitude is associated with positive reframing and positive emotions that were, in turn, associated with fewer symptoms of depression (Lambert, Fincham, & Stillman, 2012). Research evaluating the relationship between gratitude, social support and symptoms of depression suggests that social support mediates the relationship between gratitude and symptoms of depression (Wood et al., 2008). In this case, gratitude led to higher levels of social support, which was associated with fewer symptoms of depression. Unexpectedly, social support did not lead to gratitude. We found these results of interest and therefore selected two mediation models to explore the relationships between gratitude, social support, satisfaction with life and symptoms of depression in our population of police officers.

Satisfaction with life is a person’s subjective assessment that overall his or her life is meeting his or her expectations (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). It is positively associated with feelings of well-being, selfesteem and sociability, but negatively associated with neuroticism, impulsivity, emotionality and PTSD (de Terte & Stephens, 2014; McCanlies, Mnatsakanova, Andrew, Burchfiel, & Violanti, 2014). Longitudinal research found that reduced satisfaction with life was associated with a number of chronic illnesses (Feller, Teucher, Kaaks, Boeing, & Vigl, 2013). Improving satisfaction with life, on the other hand, is associated with fewer symptoms of depression (Samaranayake & Fernando, 2011). How satisfaction with life may relate to social support, gratitude and depression symptoms has yet to be explored, particularly among a high-risk population such as police officers.

Research supports the role of positive factors, including gratitude, satisfaction with life, resilience and social support, in lower symptoms of depression. However, much of this research has not evaluated how these factors may modify each other in relation to either lower symptoms of depression or positive outcomes such as satisfaction with life. The aim of this study is to expand previous research by evaluating not only direct relationships between these factors and symptoms of depression but also how these factors may modify each other in police officers who experienced Hurricane Katrina.

Material and methods

Population

Officers from a New Orleans, Louisiana, geographic area police department participated in this cross-sectional study. In 2012, 250 officers in one district were given a packet that contained instructions, a consent form to participate and questionnaires. All the officers were invited to participate; there were no exclusion criteria. The participants completed questionnaires on personal history, work during Hurricane Katrina, health information and medication taken. Psychosocial instruments were used to collect information on depression, social support, resilience, satisfaction with life and gratitude. Participants were told to use Hurricane Katrina as the index event when appropriate while completing the questionnaires. A total of 123 officers (49.2%) completed the consent form and the questionnaires, and returned them in a self-addressed stamped envelope directly to the project officer.

Officers who did not have complete data on the variables of interest were excluded from the analysis, leaving a final sample size of 116. Because we controlled for increase in sick days since Hurricane Katrina in the mediation models, officers who did not work during Hurricane Katrina were excluded from the mediation analysis, leaving a sample size of 93 in the mediation models. All participants signed consent forms. This research was approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Human Subjects Review Board and State University of New York at Buffalo Health Sciences Internal Review Board.

Demographic and lifestyle characteristics

Basic demographic and lifestyle characteristics were collected via questionnaire and included information on age, race, gender, level of education, rank, years served as a police officer, marriage status and number of alcoholic drinks per week. Race was reported as Caucasian, African-American, Asian and Other. The Other category was composed of any officer who reported his or her race as Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander or Native American. Officers who reported their race as White-Hispanic were put in the Caucasian group. Those who reported their race as Black-Hispanic were put in African-American group. Due to small numbers, all the officers who listed Other were combined with Caucasian. Marital status had three categories: single, married and divorced. The level of education ranged from ‘less than or equal to 12 years of education’ to ‘more than or equal to a college degree’. Number of alcoholic drinks per week were divided into four categories of 0–2, 3–4, 5–6, 7+ drinks per week. The officers reported their involvement in Hurricane Katrina as ‘heavy’, ‘moderate’, ‘light’ or ‘did not work during Katrina’. Rank included police officer, sergeant/lieutenant, detective and other. Officers also reported whether the number of sick days since Katrina increased as ‘no change’, ‘increased 1–5 days per year’, ‘increased 6+ days per year’ or ‘did not work during Katrina’.

Psychological assessments

Social support.

Social support was measured using the interpersonal support evaluation list (ISEL; Cohen & Hoberman, 1983). ISEL is used to assess the availability of four different types of support: tangible support, belonging, self-esteem and appraisal support. Tangible support measures the perceived availability of material assistance. Belonging assesses the presence of social connections and availability of people with whom one can spend time. Selfesteem assesses an individual’s ability to think positively about oneself in comparison to others, and the appraisal subscale measures the availability of others with whom one can talk to about issues or problems (Cohen & Hoberman, 1983). The responses were given on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (definitely false) to 3 (definitely true). Sample questions include the following: ‘There are several people that I trust to help solve my problems’, ‘Most of my friends are more interesting than I am’ and ‘I often meet or talk with family or friends’. Twenty questions are reverse coded. An overall score was calculated by summing the scores. Higher scores indicate higher social support.

Depression.

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). It consists of 20 items rated on a 4-point scale according to how often the symptom occurred in the past 7 days: 0 (rarely or none of the times, less than 1 day), 1 (some or little of the time, 1–2 days), 2 (occasionally or a moderate amount of the time, 3–4 days) and 3 (most of the time, 5–7days). Sample questions include the following: ‘I was bothered by things that usually don’t bother me’, ‘I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing’, ‘I felt fearful’ and ‘I felt sad’. Scores for the CES-D range from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate more symptoms of depression. An overall depressive symptoms score is calculated by summing the scores for each question. The mean CES-D symptom scores were 9.6 (standard deviation (SD) = 9.1) for female officers and 10.9 (SD = 9.6) for male officers, with a Cronbach’s α of .89.

Gratitude.

Gratitude was measured using the gratitude questionnaire-6 (GQ-6; McCullough et al., 2002). It is a 6-item Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample questions include the following: ‘I have so much in life to be thankful for’, ‘When I look at the world, I don’t see much to be grateful for’ and ‘Long amounts of time can go by before I feel grateful to something or someone’. To calculate a total score, the scores for questions 1, 2, 4 and 5 are summed and then added to values for questions 3 and 6, which are reverse scored. Higher scores reflect more gratitude and positive emotions such as hope and optimism. The total score was used in this study. The mean gratitude score in this population was 34.7 (SD = 7.3) with a Cronbach’s alpha of .89.

Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale.

The abbreviated version of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC10) was used to assess resilience among the police officers (Connor & Davidson, 2003). CD-RISC10 is a 10-item Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true nearly all the time) and measures the ability to cope with or adapt to adverse situations. Higher scores indicate higher resilience. Sample questions include the following: ‘I am able to adapt when changes occur’, ‘Having to cope with stress can make me stronger’ and ‘I think of myself as a strong person dealing with life’s challenges with difficulties’. An overall score can be calculated by summing the individual scores, which was used in this study. The mean resilience score was 30.3 (SD = 5.9) with a Cronbach’s alpha of .85.

Satisfaction with life.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale was used to assess how satisfied the police officers are with their life (Diener et al., 1985). It is a 5-item Likert scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample questions include the following: ‘In most ways my life is close to my ideal’, ‘I am satisfied with my life’ and ‘If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing’. The scores are summed, and an overall score is then used to evaluate an individual’s satisfaction with life. A score of 30–35 indicates ‘highly satisfied’, 25–29 indicates ‘things are mostly good’, 20–24 indicates ‘generally satisfied’, 15–19 ‘slightly below average life satisfaction’, 10–14 indicates ‘dissatisfied’ and 5–9 indicates ‘extremely dissatisfied’. The overall score was used in this study. The mean satisfaction with life score in this population was 23.2 (SD = 7.5) with a Cronbach’s alpha of .92.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. The potential confounders – age, number of alcoholic drinks per week, military experience and increased sick days since Katrina – were selected based on the literature, or because they were associated with either the dependent or independent variables (Violanti et al., 2011; West et al., 2008). Ordinary least-square (OLS) regression in mediation analysis was used to estimate direct and indirect effects of each predictor on the outcome variable using the PROCESS macro for SAS (Hayes, 2013). We used 10,000 bootstrap samples to estimate the 95% confidence intervals (CI) and to generate our mediation results. A significant result is indicated if the 95% CI does not include 0. A significant result indicates that the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is mediated by one or more of the mediators. Four models were evaluated to better understand the relationship between gratitude, resilience, satisfaction with life and social support on symptoms of depression. The first model evaluated the relationship between social support and symptoms of depression mediated by gratitude, resilience and satisfaction with life. The second model evaluated the relationship between gratitude and symptoms of depression mediated by social support. The third model evaluated the relationship between satisfaction with life and symptoms of depression mediated by social support. The fourth model evaluated the relationship between gratitude and satisfaction with life mediated by social support. Direct and indirect effects were obtained.

Results

The majority of the officers were Caucasian/Other (57.9%) and were, on average, 43.1 (SD±9.0) years old (Table 1). Most of the officers had some college education (60.4%), were married (58.6%) and had fewer than two alcoholic drinks per day (56.6%). Most of the officers reported no change in the number of sick days since Hurricane Katrina (56.1%).

Table 1.

Demographics and lifestyle characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristic | Females (N = 30) |

Males (N = 86) |

Total (N = 116) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian/Other | 15 | 51.7 | 51 | 60.0 | 66 | 57.9 |

| African-American | 14 | 48.3 | 34 | 40.0 | 48 | 42.1 |

| Education | ||||||

| High school/GED | 5 | 16.7 | 7 | 8.1 | 12 | 10.3 |

| College <4years | 13 | 43.3 | 57 | 66.3 | 70 | 60.4 |

| College ≥4years | 12 | 40.0 | 22 | 25.6 | 34 | 29.3 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 9 | 30.0 | 14 | 16.5 | 23 | 20.0 |

| Married | 14 | 46.7 | 53 | 62.3 | 67 | 58.6 |

| Divorced | 7 | 23.3 | 18 | 21.2 | 25 | 21.7 |

| Alcohol drinks per day | ||||||

| ≤1–2 | 22 | 75.9 | 42 | 50.0 | 64 | 56.6 |

| 3 or 4 | 6 | 20.7 | 24 | 28.6 | 30 | 26.6 |

| 5 or 6 | 1 | 3.5 | 12 | 14.3 | 13 | 11.5 |

| ≥7 | 0 | .0 | 6 | 7.1 | 6 | 5.3 |

| Military | ||||||

| Yes | 0 | .0 | 27 | 31.4 | 27 | 23.5 |

| No | 29 | 100.0 | 59 | 68.6 | 88 | 76.5 |

| Increase in sick days since Katrina | ||||||

| No change | 12 | 41.4 | 52 | 61.2 | 64 | 56.1 |

| 1–5 days/year | 4 | 13.8 | 13 | 15.3 | 17 | 14.9 |

| 6+ days/year | 4 | 13.8 | 8 | 9.4 | 12 | 10.5 |

| No work during Katrina | 9 | 31.0 | 12 | 14.1 | 21 | 18.4 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Age | 43.5 (9.1) | 43.0 (9.0) | 43.1 (9.0) | |||

| Years served | 14.3 (7.7) | 18.0 (9.5) | 17.1 (9.2) | |||

| Depression score (CESD) | 9.6 (9.1) | 10.9 (9.6) | 10.6 (9.4) | |||

| Social support score (ISEL) | 87.1 (25.7) | 86.8 (22.0) | 86.9 (22.9) | |||

| Resiliency score | 31.4 (4.8) | 29.9 (6.2) | 30.3 (5.9) | |||

| Satisfaction with life score | 23.9 (6.7) | 23.0 (7.8) | 23.2 (7.5) | |||

| Gratitude score | 36.5 (5.7) | 34.1 (7.7) | 34.7 (7.3) | |||

CESD: Center for Epidemiological Depression scale; GED: general equivalency degree; ISEL: interpersonal support evaluation list; SD: standard deviation.

The mean social support score was 87.1 (SD±25.7) for female officers and 86.8 (SD±22.0) for male officers (Table 1). Mean depression symptoms scores were 9.6 (SD±9.1) for females and 10.9 (SD±9.6) for males. Mean gratitude scores were 36.5 (SD±5.7) for female officers and 34.1 (SD±7.7) for male officers. Mean resiliency scores were 31.4 (SD±4.8) for female officers and 29.9 (SD±6.2) for male officers. Mean satisfaction with life scores were 23.9 (SD±6.7) for female officers and 23.0 (SD±7.8) for male officers.

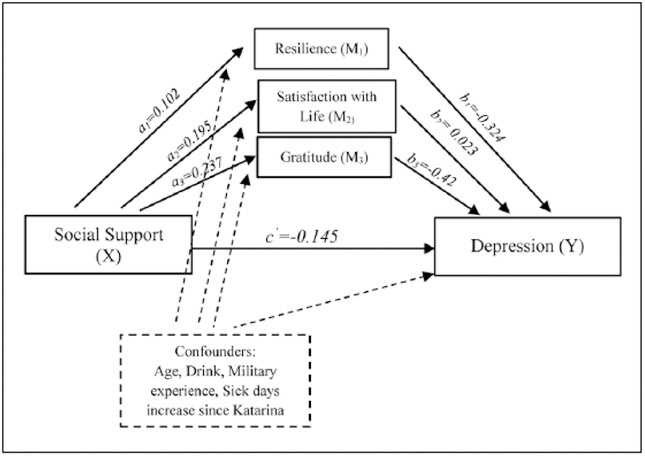

Model 1: the relationship between social support and symptoms of depression mediated by gratitude, satisfaction with life and resilience

The multiple mediator model indicated that about 65% of the variance in symptoms of depression were accounted for by all three mediators and social support (R2 = .66). The total effect (c=−0.273; 95% CI = −0.343, −0.203) and direct effects (c′ = −0.145; 95% CI = −0.244, −0.046) indicated that social support had a direct effect on symptoms of depression independent of gratitude, resilience and satisfaction with life, and that gratitude, resilience and satisfaction with life also mediated the effect of social support on symptoms of depression (Figure 1, Table 2). When the indirect effect of each mediator was evaluated, only resilience was found to mediate the relationship between social support and symptoms of depression (effect=−0.033; 95% CI =−0.079, −0.009). These results indicated that officers with higher social support had higher resilience, which was associated with fewer symptoms of depression. However, these results did not indicate that either gratitude or satisfaction with life mediated the relationship between social support and depression. To better understand the role gratitude and satisfaction with life may play in the development of social support and depression, we selected three more models specifically designed to elucidate the directionality and relationships between these variables, social support and symptoms of depression.

Figure 1.

Model I shows the diagram of the mediator model with resilience, satisfaction with life and gratitude as potential mediators between social support and depression symptoms.

Table 2.

Total direct and indirect effects of social support and symptoms of depression mediated by resilience, satisfaction with life and gratitude.

| Effect | Boot SE | Lower 95% CI |

Upper 95% CI |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect of X on Y(c) | −0.273 | 0.035 | −0.343 | −0.203 | .000 |

| Direct effect of X on Y (c′) | −0.145 | 0.050 | −0.244 | −0.046 | .005 |

| Indirect effects Resilience | −0.033 | 0.017 | −0.079 | −0.009 | |

| Satisfaction with life | 0.005 | 0.033 | −0.071 | 0.059 | |

| Gratitude | −0.099 | 0.055 | −0.202 | 0.009 |

SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval.

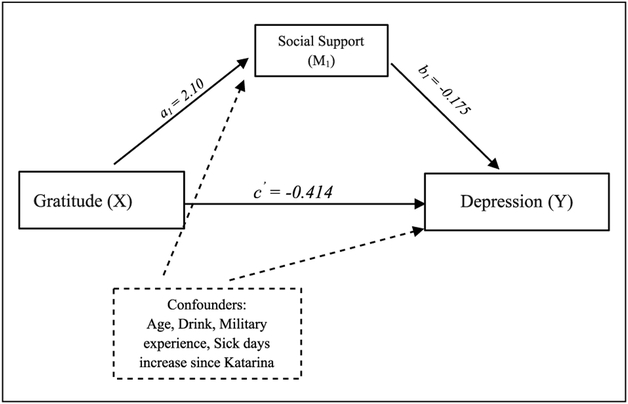

Model 2: the relationship between gratitude and symptoms of depression mediated by social support

Model 2 evaluated the relationship between gratitude and symptoms of depression mediated by social support. This multiple mediation model indicated that gratitude was associated with symptoms of depression, and that this relationship was partially mediated by social support (Figure 2, Table 3). Approximately 60% of the variance in symptoms of depression was accounted for by both gratitude and social support. In this case, higher levels of gratitude were associated with higher levels of social support (a=2.10), which was associated with lower symptoms of depression (b=−0.175). The direct effect (c′=—0.414; 95% CI=−0.695, −0.133) and indirect effect (effect=−0.368; 95% CI=−0.653, −0.191) indicated that gratitude had a direct effect on the level of depression independent of social support. The indirect effect indicated that social support mediated the relationship between gratitude and symptoms of depression. These results showed that officers with higher gratitude had higher levels of social support, and that higher social support was associated with fewer symptoms of depression. These results along with those from Model 1 indicated that while gratitude can lead to social support, social support could not lead to gratitude.

Figure 2.

Model 2 shows the diagram of the mediator model with social support as a potential mediator between gratitude and depression symptoms.

Table 3.

Total direct and indirect effects of gratitude and symptoms of depression mediated by social support.

| Effect | Boot SE | Lower 95% CI |

Upper 95% CI |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect of X on Y (c) | −0.782 | 0.108 | −0.998 | −0.565 | .000 |

| Direct effect of X on Y (c′) | −0.414 | 0.141 | −0.695 | −0.133 | .005 |

| Indirect effect Social support | −0.368 | 0.111 | −0.653 | −0.191 |

SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval.

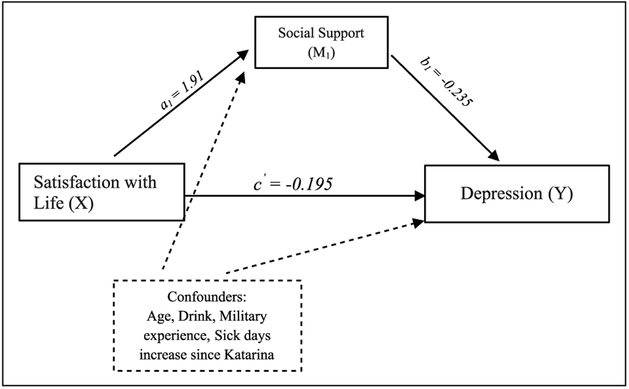

Model 3: the relationship between satisfaction with life and symptoms of depression meditated by social support

Model 3 was chosen to better understand the role of satisfaction with life, social support and depression. In this model, satisfaction with life was not associated with symptoms of depression independent of social support (Figure 3, Table 4). Higher levels of satisfaction with life were associated with higher levels of social support (a =1.91), which, in turn, were associated with lower symptoms of depression (b = −0.235). The direct effect (c′ = −0.195; 95% CI = −0.471, 0.082) and indirect effect (effect = −0.440; −0.752, −0.232) indicated that satisfaction with life influenced symptoms of depression through social support, but that satisfaction with life was not directly associated with lower symptoms of depression. Officers with higher life satisfaction and higher levels of social support had fewer symptoms of depression.

Figure 3.

Model 3 shows the diagram of the mediator model with social support as a potential mediator between satisfaction with life and depression symptoms.

Table 4.

Total direct and indirect effects of satisfaction with life and symptoms of depression mediated by social support.

| Effect | Boot SE | Lower 95% CI |

Upper 95% CI |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect of X on Y (c) | −0.644 | 0.129 | −0.900 | −0.387 | .000 |

| Direct effect of X on Y (c′) | −0.195 | 0.139 | −0.471 | 0.082 | .164 |

| Indirect effect Social support | −0.449 | 0.129 | −0.752 | −0.232 |

SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval.

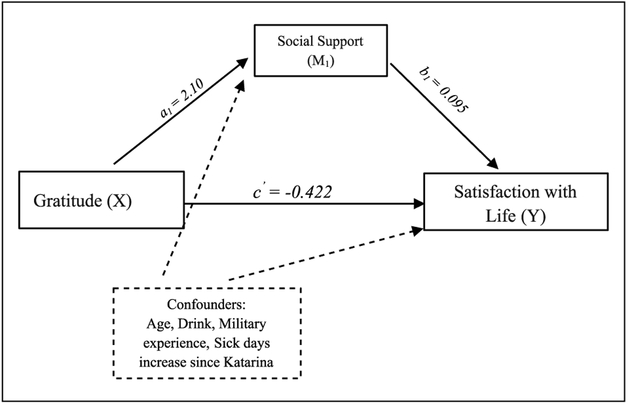

Model 4: the relationship between gratitude and satisfaction with life mediated by social support

The final model evaluated the relationship between gratitude, social support and satisfaction with life. The multiple mediation model indicated that gratitude was directly associated with higher levels of satisfaction with life, and that social support mediated this relationship. Approximately 56% of the variance in symptoms of depression was accounted for by both satisfaction with life and social support. The direct effect indicated that gratitude was directly associated with satisfaction with life (c′ = 0.422; 95% CI = 0.194, 0.645; Figure 4, Table 5). Furthermore, higher levels of gratitude were associated with higher levels of social support, which were associated with higher satisfaction with life (effect=0.199; 95% CI = 0.064, 0.375). These results indicated that gratitude was independently associated with satisfaction with life, as well as associated with satisfaction with life through social support. Higher levels of gratitude were associated with higher levels of social support (a=2.10), which were, in turn, associated with higher levels of satisfaction with life (0.095). Therefore, officers with high gratitude and high social support had higher satisfaction with life.

Figure 4.

Model 4 shows the diagram of the mediator model with social support as a potential mediator between gratitude and satisfaction with life.

Table 5.

Total direct and indirect effects of gratitude and satisfaction with life mediated by social support.

| Effect | Boot SE | Lower 95% CI |

Upper 95% CI |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect of X on Y (c) | 0.620 | 0.084 | 0.453 | 0.787 | .000 |

| Direct effect of X on Y (c′) | 0.422 | 0.1 14 | 0.194 | 0.649 | .0004 |

| Indirect effect Social support | 0.199 | 0.079 | 0.064 | 0.375 |

SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

This study evaluated the role of gratitude, resilience, satisfaction with life and social support in protecting officers who worked during or after Hurricane Katrina from symptoms of depression. The results suggest that resilience, social support and gratitude are associated with lower levels of depression symptoms, and that some of these factors partially mediate the link between gratitude and symptoms of depression, as well as social support and symptoms of depression.

Higher levels of social support were directly associated with fewer symptoms of depression, as well as acted as a mediator between gratitude and depression, satisfaction with life and depression, and gratitude and satisfaction with life. These results show the importance of social support in mitigating symptoms of depression directly and as a mediator. The direct association between social support and depression indicates that higher levels of social support in officers are associated with fewer symptoms of depression, which is consistent with previous research (Crowe, Butterworth, & Leach, 2016; Hallgren, Lundin, Tee, Burstrom, & Forsell, 2017; Rung, Gaston, Robinson, Trapido, & Peters, 2017). For example, officers who perceive organizational support are more likely to seek out psychological services, and for those who receive treatment, positive social relationships predict larger improvements in symptoms of depression (Hallgren et al., 2017; Tucker, 2015). Social support promotes meaningful social roles, positive health behaviors and a sense of well-being, which, in turn, protects against depression (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; Hallgren et al., 2017; Layous, Chancellor, & Lyubomirsky, 2014).

Our results also show that social support is associated with higher resilience, which, in turn, is associated with fewer symptoms of depression. Among veterans, unit support was associated with higher resilience, which was associated with fewer symptoms of depression (Pietrzak et al., 2010). In this case, social support may increase feelings of self-efficacy and personal control that fosters active coping, which may help veterans deal with symptoms of depression. Similar research has reported a relationship between higher resiliency and less distress, anxiety, depression and higher satisfaction with life (Smith et al., 2016). Resilient individuals are more likely to report feeling positive emotions such as optimism and hope, as well as to use a variety of coping skills to deal with negative situations (de Terte, Stephens, & Huddleston, 2014; Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh, & Larkin, 2003; Sinclair et al., 2016). Gloria and Steinhardt (2016) found that adaptive coping mediates the relationship between positive emotions and resilience, while resilience mediates the relationship between stress and depressive symptoms. In this study, higher resilience protected postdoctoral students from stress and depressive symptoms (Gloria & Steinhardt, 2016). In individuals who have been previously exposed to trauma, those with high resilient coping had lower depression scores (Sinclair et al., 2016). Furthermore, because resilience is modifiable, increasing resilience may be a valuable resource for treating or reducing depression in officers (Connor & Davidson, 2003).

Gratitude was associated with both reduced symptoms of depression and higher satisfaction with life. Officers with higher gratitude were more likely to have higher social support, which was associated with fewer symptoms of depression and higher satisfaction with life. These results support previous research findings that positive psychological factors such as gratitude, hope and self-forgiveness were associated with social support, higher levels of happiness and lower levels of depression (Macaskill, 2012; Santos et al., 2013; Wood et al., 2008). Prosocial relationships are positively associated with well-being and resilience, as well as with fewer symptoms of depression (Santos et al., 2013). Grateful individuals are more likely to appreciate good in their lives, accept social support when needed, which boosts self-esteem, and engage in self-reassuring behaviors and less likely to be self-critical. All of these are associated with higher satisfaction with life (Kong, Ding, & Zhao, 2015; Petrocchi & Couyoumdjian, 2016). Gratitude is also associated with positive reframing, which consequently increases positive emotions and results in fewer symptoms of depression (Lambert et al., 2012; Petrocchi & Couyoumdjian, 2016). With this in mind, interventions that increase gratitude may help reduce symptoms of depression and increase satisfaction with life in officers following a natural disaster.

A strength of this study is that it is unique; there are few studies that have evaluated the effects of a natural disaster on police officers. However, there are also limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the sample size was relatively small with a response rate of 49%. Police officers who participated in this study may differ from those who did not participate. Unfortunately, we did not have any information on nonresponders. Recall bias is also a potential issue as this was a cross-sectional study using self-report surveys. To mitigate this limitation, Hurricane Katrina was used as the index event. However, confounding variables may have influenced the results. Because both the independent and dependent variables are collected simultaneously, cross-sectional studies preclude the direction of causality. Therefore, it is possible that symptoms of depression can lead to social avoidance and isolation, thus reducing social support or other protective factors such as gratitude. Finally, the sample consisted of police from one geographic area; therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to other police departments or the greater population.

Despite the limitations, this study identifies possible positive psychological factors associated with fewer symptoms of depression in police officers. Gratitude, social support and satisfaction with life are associated either directly or indirectly with fewer symptoms of depression. Thus, this study represents another meaningful step toward understanding how positive psychological factors may reduce symptoms of depression among law enforcement officers. There is limited knowledge about positive psychological factors that may reduce symptoms of depression; this research reduces this knowledge gap, especially as it relates to police officers. Additional research could focus on how it may be beneficial to promote these factors in the lives of those regularly at risk of depression.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The effect of social support, gratitude, resilience and satisfaction with life on depressive symptoms among police officers following Hurricane Katrina was funded by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Grant Number: R03 OH009582-02). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

References

- Adams T, & Turner M (2014). Professional responsibilities versus familial responsibilities: an examination of role conflict among first responders during the Hurricane Katrina disaster. Journal of Emergency Management, 12(1), 45–54. doi: 10.5055/jem.2014.0161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum D (2006, January 9). Deluged: When Katrina hit, where were the police? The New Yorker, pp. 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, & Seeman TE (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine, 51, 843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard BP, Driscoll RJ, Kitt M, West CA, & Tak SW (2006). Health hazard evaluation of police officers and firefighters after Hurricane Katrina-New Orleans, Louisana, October 17–28 and November 30-December 5, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 55, 456–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Hoberman HM (1983). Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13, 99–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1983.tb02325.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KM, & Davidson JR (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe L, Butterworth P, & Leach L (2016). Financial hardship, mastery and social support: Explaining poor mental health amongst the inadequately employed using data from the HILDA survey. SSM-Population Health, 2, 407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, & McFarlane AC (2006). The extent and impact of mental health problems after disaster. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(Suppl. 2), 9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Terte I, & Stephens C (2014). Psychological resilience of workers in high-risk occupations. Stress And Health, 30, 353–355. doi: 10.1002/smi.2627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Terte I, Stephens C, & Huddleston L (2014). The development of a three part model of psychological resilience. Stress And Health, 30, 416–424. doi: 10.1002/smi.2625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, & Griffin S (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feller S, Teucher B, Kaaks R, Boeing H, & Vigl M (2013). Life satisfaction and risk of chronic diseases in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Germany study. PLoS ONE, 8, e73462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactionsof the Royal Society. Series B, Biological Sciences, 359, 1367–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Tugade MM, Waugh CE, & Larkin GR (2003). What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 365–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloria CT, & Steinhardt MA (2016). Relationships among positive emotions, coping, resilience and mental health. Stress and Health, 32, 145–156. doi: 10.1002/smi.2589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren M, Lundin A, Tee FY, Burstrom B, & Forsell Y (2017). Somebody to lean on: Social relationships predict posttreatment depression severity in adults. Psychiatry Research, 249, 261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.06028131948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (Kenney DA Ed.). New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Chen YM, Wang HH, Chang SC, & Ma SC (2016). Association among components of resilience and workplace violence-related depression among emergency department nurses in Taiwan: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25, 2639–2647. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacoviello BM, & Charney DS (2014). Psychosocial facets of resilience:Implications for preventing posttrauma psychopathology, treating trauma survivors, and enhancing community resilience. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5, Article 23970, doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.23970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapikiran S, & Acun-Kapikiran N (2016). Optimism and psychological resilience in relation to depressive symptoms in university students: Examining the mediating role of self-esteem. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 16, 2087–2110. [Google Scholar]

- Knabb RD, Rhome JR, & Brown DP (2011). Hurricane Katrina: August 23 – 30, 2005 (Tropical Cyclone Report). Retrieved from http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL122005_Katrina.pdf

- Kong F, Ding K, & Zhao J (2015). The relationships among gratitude, self-esteem, social support and life satisfaction among undergraduate students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 477–489. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9519-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert NM, Fincham FD, & Stillman TF (2012). Gratitude and depressive symptoms: The role of positive reframing and positive emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 26, 615–633. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.595393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layous K, Chancellor J, & Lyubomirsky S (2014). Positive activities as protective factors against mental health conditions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123(1), 3–12. doi: 10.1037/a0034709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaskill A (2012). A feasibility study of psychological strengths and well-being assessment in individuals living with recurrent depression. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7, 372–386. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2012.702783 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCanlies EC, Gu JK, Andrew ME, Burchfiel CM, & Violanti JM (2017). Resilience mediates the relationship between social support and post-traumatic stress symptoms in police officers. Journal of Emergency Management, 15, 107–116. doi: 10.5055/jem.2017.0319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCanlies EC, Mnatsakanova A, Andrew ME, Burchfiel CM, & Violanti JM (2014). Positive psychological factors are associated with lower PTSD symptoms among police officers: Post Hurricane Katrina. Stress and Health, 30, 405–415. doi: 10.1002/smi.2615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Emmons RA, & Tsang JA (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrocchi N, & Couyoumdjian A (2016). The impact of gratitude on depression and anxiety: The mediating role of criticizing, attacking, and reassuring the self. Self and Identity, 15,191–205.doi: 10.1080/15298868.2015.1095794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Rivers AJ, Morgan CA, & Southwick SM (2010). Psychosocial buffers of traumatic stress, depressive symptoms, and psychosocial difficulties in veterans of operations enduring freedom and Iraqi freedom: The role of resilience, unit support, and postdeployment social support. Journal of Affective Disorder, 120, 188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Tracy M, Galea S, Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Hamblen JL, … Norris FH (2012). Resilience in the face of disaster: prevalence and longitudinal course of mental disorders following hurricane Ike. PLoS ONE, 7, e38964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D Scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rung AL, Gaston S, Robinson WT, Trapido EJ, & Peters ES (2017). Untangling the disaster-depression knot: The role of social ties after Deepwater Horizon. Social Science & Medicine, 177, 19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaranayake CB, & Fernando AT (2011). Satisfaction with life and depression among medical students in Auckland, New Zealand. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 124(1341), 12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos V, Paes F, Pereira V, Arias-Carrion O, Silva AC, Carta MG, … Machado S (2013). The role of positive emotion and contributions of positive psychology in depression treatment: Systematic review. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 9, 221–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simning A, Seplaki CL, & Conwell Y (2016). The association of an inability to form and maintain close relationships due to a medical condition with anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 193, 130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair VG, Wallston KA, & Strachan E (2016). Resilient coping moderates the effect of trauma exposure on depression. Research in Nursing & Health, 39, 244–252. doi: 10.1002/nur.21723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MM, Saklofske DH, Keefer KV, & Tremblay PE (2016). Coping strategies and psychological outcomes: The moderating effects of personal resiliency. The Journal of Psychology, 150, 318–332. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2015.1036828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, & Yehuda R (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5, Article 25338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JM (2015). Police officer willingness to use stress intervention services: The role of Perceived Organizational Support (POS), confidentiality and stigma. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 17, 304–314. [Google Scholar]

- Violanti JM, Slaven JE, Charles LE, Burchfiel CM, Andrew ME, & Homish GG (2011). Police and alcohol use: A descriptive analysis and associations with stress outcomes. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 36, 344–356. doi: 10.1007/s12103-011-9121-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volz M, Möbus J, Letsch C, & Werheid K (2016). The influence of early depressive symptoms, social support and decreasing self-efficacy on depression 6 months poststroke. Journal of Affective Disorders, 206, 252–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Watts SE, Marsee MA, Taylor LK, Costa NM, Cannon MF, … Pina AA (2007). The psychosocial impact of Hurricane Katrina: Contextual differences in psychological symptoms, social support, and discrimination. Behavior Research and Therapy, 45, 2295–2306. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West C, Bernard B, Mueller C, Kitt M, Driscoll R, & Tak S (2008). Mental health outcomes in police personnel after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 50, 689–695. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181638685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Maltby J, Gillett R, Linley PA, & Joseph S (2008). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 854–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]