Abstract

Background:

In addition to the airway-relaxing effects, β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) agonists are also found to have broad anti-inflammatory effects. The current study is to define the role of β2AR agonists in limiting myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI).

Methods and results:

Adult male wild-type (WT) and IL-10 KO mice underwent 40-min left coronary artery ligation and 60-min reperfusion. A selective β2AR agonist, Clenbuterol at doses of 0.1 μg or 1 μg/per gram weight i.v. 5 min before reperfusion, significantly reduced myocardial infarct size (IS) by 28% and 39% (vs. control, p<0.05) in WT mice, but had no protective effect in IL-10 KO mice. Inhalational therapy with nebulized Clenbuterol, Albuterol, Salmeterol or Arformoterol immediately before ischemia significantly reduced IS (p<0.05) in WT mice respectively. Splenectomy similarly reduced IS as Clenbuterol-treated mice, but intravenous Clenbuterol did not further reduce IS in splenectomized mice. In splenectomized WT mice, acute transfer of isolated splenocytes, not the Clenbuterol-pretreated splenocytes, restored the myocardial IS to the level of intact mice. Intravenous Clenbuterol significantly increased splenic protein levels of β2AR, phosphorylated Akt and IL-10 and plasma IL-10, and inhibited the expression of proinflammatory mRNAs.

Conclusions:

Both intravenous and inhalational β2AR agonists exert a cardioprotective effect against IRI by activating the anti-inflammatory β2AR-IL-10 pathway.

Keywords: β2AR, Clenbuterol, heart, ischemia/reperfusion, myocardial infarction

INTRODUCTION

Recently, β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) agonists were found to exert protective effects against ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) in the kidney1, brain2 and spinal cord3. Several studies have also demonstrated that activation of β2AR can exert cardioprotective effects against ischemia/reperfusion injury4–6. In these studies, the β2AR agonist was administered either before ischemia or before reperfusion and the results suggested that the β2AR agonist acted primarily on cardiomyocytes by activating the cAMP-PKA-pAkt pathway to inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis. However, the anti-inflammatory effect of β2AR in mediating cardioprotection remains unknown. Inflammatory responses during post-ischemic reperfusion play a key role in mediating myocardial reperfusion injury. Innate and adaptive immune systems are both involved in this inflammatory response7, 8. Recently, β2AR agonists have been shown to exert broad anti-inflammatory effects9–11. The present study sought to evaluate the role of β2AR activation in promoting anti-inflammatory responses and in attenuating myocardial IRI. Using an established in vivo mouse model of myocardial IRI, our results demonstrate that β2AR agonist attenuates myocardial infarct size by activating a pathway involving β2AR, Akt phosphorylation and IL-10 in splenic leukocytes.

MATERIALS and METHODS

This study conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (Eighth Edition, revised 2011) and was conducted under protocols approved by the University of Virginia’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Animals and experimental protocols.

C57BL/6 wild type (WT) mice (9–13 weeks of age, purchased from The Jackson Laboratory) and congenic IL-10 knockout (KO) mice (9–13 weeks of age, breeding pairs purchased from The Jackson Laboratory) were randomly assigned to either IR injury groups or sham surgery groups. Compared to the WT mice, the phenotype of IL-10 KO mice showed significantly higher spleen weight (% of body weight, 0.446±0.033% vs. 0.392±0.013%, p<0.05). There was no difference in body weight, heart weight, blood pressure, heart rate. There was no evidence of dermatitis or rectal prolapse as reported in the literature.

In treated mice, Clenbuterol (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administered either as an i.v. bolus 5 min before reperfusion at two different doses, 0.1 μg/g and 1.0 μg/g weight with an injection volume of 2 μl per gram body weight, or nebulized in a solution with 1 mg Clenbuterol in 5 ml saline. Clenbuterol was nebulized using an Ecosonic nebulizer (Medisonic USA Inc., Clarence, NY). The effect of Clenbuterol on heart rate was determined using PowerLab instrumentation (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Additional 3 short acting to long acting β2AR agonists, albuterol, salmeterol and Arformoterol (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), were also tested individually in 3 groups of mice respectively and administered by inhalation before ischemia.

Myocardial IR injury and measurement of infarct size.

In previous work, we established that myocardial infarct size (IS) as measured by late-gadolinium enhanced MRI at 60 minutes of reperfusion attains 95% of the size measured by the same method at 24 hours post-reperfusion in mice12, 13. We therefore used 60 minutes of reperfusion in the present study. The left coronary artery (LCA) of WT or IL-10 KO mice was ligated for a duration of 40 minutes followed by 60 minutes of reperfusion as detailed previously7, 8, 13, 14. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (80mg/kg, i.p.) and orally intubated. An additional dose of pentobarbital (40mg/kg, i.p.) was applied shortly after reperfusion. The adequacy of the anesthesia was confirmed by hind limb pinch reflex every 15 minutes. The heart was exposed through a left thoracotomy. The LCA was identified under a dissecting microscope. An 8–0 Prolene suture was placed around the LCA at a level 1 mm inferior to the left auricle. Ischemia was induced by securing a suture over a piece of PE-60 tubing placed parallel to the LCA, and reperfusion was achieved by removing the tube. Successful ligation of the LCA was confirmed by blanching in the ischemic zone. The mice were euthanized 60 minutes after reperfusion, and the explanted hearts were cannulated through the ascending aorta for perfusion with 3 ml of 1.0% TTC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The LCA was then re-occluded with the same suture used for coronary occlusion prior to perfusion with 10% Phthalo blue to determine risk region (RR), which was statistically similar among all groups. The left ventricle was then cut into 5 to 7 transverse slices that were weighed and digitally photographed to determine IS as a percent of RR7, 8.

Splenic leukocyte adoptive transfer (SPAT): Splenocytes are purified from WT mice and then transferred into recipient mice 5 minutes before reperfusion via external jugular vein injection at dose of 5×106 splenocytes cells/mouse in 50 μl. In Clenbuterol-treated splenocytes, the splenocytes were treated with Clenbuterol for 10 min at a dose of 0.01 μg in 20×106 splenocytes cells (200 μl). After treatment, these splenocytes were re-suspended in Clenbuterol-free PBS. Splenocytes were counted using Cellometer (Nexcelom, Lawrence, MA).

Several additional groups of mice without IRI were treated either with PBS or Clenbuterol. The plasma, heart and spleen were harvested at 5, 15, 30 min following treatment. The samples were analyzed for ELISA, RT-PCR and Western Blot analysis. Clenbuterol-induced tachyarrhythmia was evaluated in mice treated with both bolus iv injection and nebulization using a PowerLab physiological monitoring system, Colorado Springs, CO).

Western analysis.

Protein levels of β2AR, Akt phosphorylation, CD38, FPR1, IL-1β and IL-10 in the spleen and/or plasma were assessed by Western blot analysis as previous described14. Briefly, left ventricular and splenic tissue were homogenized in PBS. Plasma samples were obtained by centrifuging blood samples at 1600g for 20 minutes. Total protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Twenty micrograms of protein were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE. After transfer, nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were probed with primary antibodies against β2AR, total Akt, phosphorylated Akt (anti-Ser473), CD38, FPR1, IL-1β and IL-10 (ThermoFisher Scientific) at a 1:2,000 dilution and with secondary antibodies (Promega, Madison, WI) at a 1:5,000 dilution in blocking solution (0.5% BSA in TBS-T). Proteins were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific) followed by densitometry using a FluorChem 8900 imaging system (Alpha Innotech, Santa Clara, CA). β-actin was used as a loading control.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis.

Splenic mRNA levels of CD38, Egr2, Fpr1, IL-10, IL-1β and Ncf1 were assessed by qRT-PCR. In brief, total RNA was isolated from cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN USA, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNAs were synthesized using iScript™ cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). qPCR was performed with the SsoAdvanced™ Universal SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and monitored using a CFX Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). GAPDH (Unique Assay ID: qMmuCID0027497) was used as a housekeeping gene. The primers were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories. (Unique Assay ID: qMmuCID0006259 for CD38, qMmuCID0009042 for Egr2, qMmuCID0015439 for Fpr1, qMmuCID0015452 for IL10, qMmuCID0005641 for IL-1β and qMmuCID0006405 for Ncf1). mRNA levels were quantified using the 2(-ΔΔCt) relative quantification method as previously described15.

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). Changes in heart rates were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni pairwise comparisons. All other data were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by t-test for unpaired data with Bonferroni correction.

RESULTS

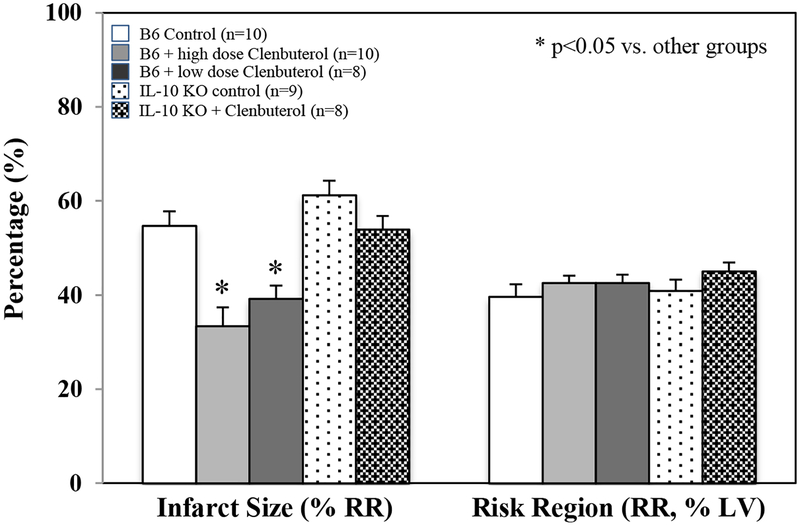

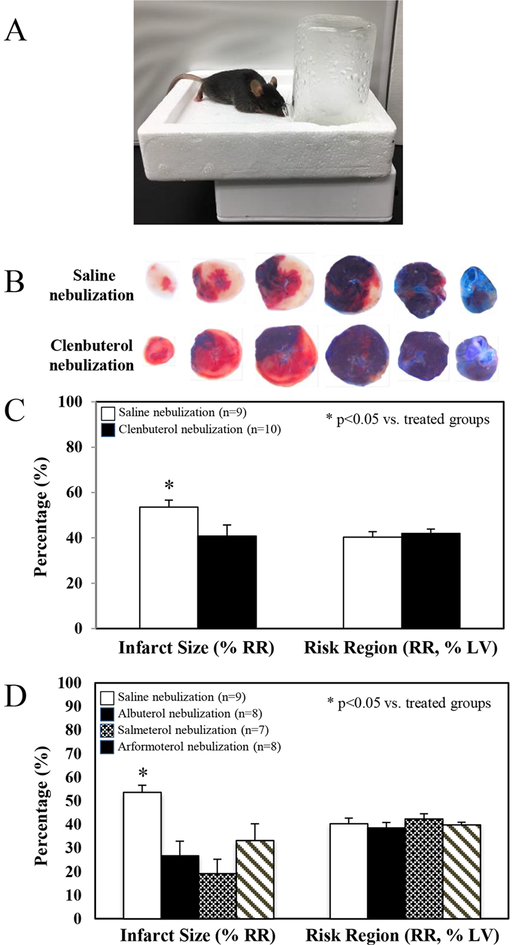

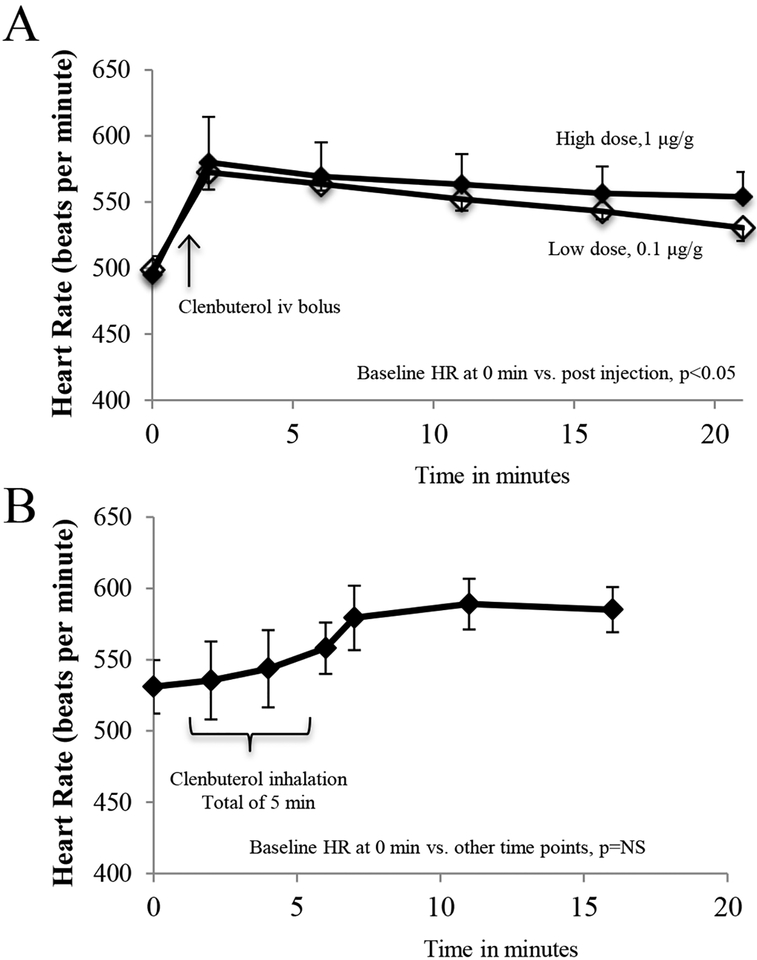

C57BL/6 WT mice and congenic IL-10 KO mice underwent 40 min of LCA occlusion followed by 60 min of reperfusion. A long-acting selective β2AR agonist, Clenbuterol at doses of 0.1 μg and 1 μg per gram weight, was administered as an i.v. bolus 5 min before reperfusion. Clenbuterol at 0.1 μg and 1 μg per gram weight significantly attenuated myocardial IS by 28% and 39% in WT mice, respectively (IS as %RR; 39.2±2.8 and 33.4±4.0 vs. control 54.7±3.4, p<0.05). There was no significant difference in the infarct-sparing effect of Clenbuterol between these two doses. The infarct-sparing effect of Clenbuterol disappeared in IL-10 KO mice, even at the high dose of 1 μg per gram weight. There was no difference in risk region among these groups (Figure 1). Inhalational therapy with nebulized Clenbuterol (1mg in 5 ml normal saline for 5 min) immediately before ischemia significantly reduced infarct size (40.8±4.9 vs. 53.6±3.0, p<0.05) in WT mice (Figure 2A, 2B & 2C). Intravenous bolus administration of Clenbuterol significantly increased heart rate by 36% in both high-dose and low-dose mice (Figure 3, upper panel). However, inhalational therapy with Clenbuterol only increased heart rate by 11% from the corresponding baseline, a modest effect that did not achieve statistical significance (Figure 3, lower panel). Three more selective β2AR agonists were tested to evaluate their roles in attenuating myocardial IRI. Albuterol (short-acting at dose of 300 μg/ml), salmeterol (moderate-acting at a dose of 20 μg/ml) and arformoterol (long-acting at a dose of 10 μg/ml) were nebulized to treat mice for 1 minute before LCA occlusion. All these β2AR agonists exerted similar cardioprotective effect in attenuating myocardial IS (Figure 2D).

Figure 1. Selective β2AR activation attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in wild type but not IL-10 KO mice.

C57BL/6 mice and congenic IL-10 KO mice (n=animals in each group) were treated with a selective β2AR agonist, Clenbuterol, at two different doses as an i.v. bolus 5 min before reperfusion, 0.1 μg/g (low dose) and 1.0 μg/g weight (high dose) using a constant injection volume of 2 μl per g weight. IL-10 KO mice were treated with the high dose of Clenbuterol. Infarct size is presented as percentage of risk region (RR). RR is defined as percentage of left ventricle (LV).

Figure 2. Pretreatment of mice with inhalational β2AR agonist attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury.

After evaluating its intravenous formula in myocardial IR injury, inhalational Clenbuterol as well as other selective β2AR agonists, was further studied. Clenbuterol (long-acting at a dose of 200 μg/ml), Albuterol (short-acting at dose of 300 μg/ml), salmeterol (moderate-acting at a dose of 20 μg/ml) and arformoterol (long-acting at a dose of 10 μg/ml) was individually nebulized to treat mice for 1 minute before LCA occlusion using an Ecosonic nebulizer (2A). Mice received inhalational therapy with saline only or β2AR agonists for 1 min before undergoing 40 min of ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion. Hearts were harvested at the end of 60 min reperfusion and the myocardial infarct zone, ischemic zone and none ischemic zone were delineated using TTC-blue staining (2B). All these β2AR agonists exerted similar cardioprotective effect in attenuating myocardial infarct size (Figure 2C to 2D, n represents animal number in each group). (2A).

Figure 3. Positive chronotropic effect of Clenbuterol in mice.

Panel A: Heart rate was monitored in mice (3–4 animals in each group) following treatment with intravenous Clenbuterol at 2 different doses. Heart rate rapidly increased by 36% within one min following injection and then slowly drifted down over the course of 20 min. The tachycardiac response was slightly less, but without statistical difference, in mice treated with low dose Clenbuterol. Panel B: Tachycardia was reduced in mice treated with inhalational Clenbuterol (3 animals). Note that the increase in heart rate over baseline (11%) was modest and did not reach statistical significance.

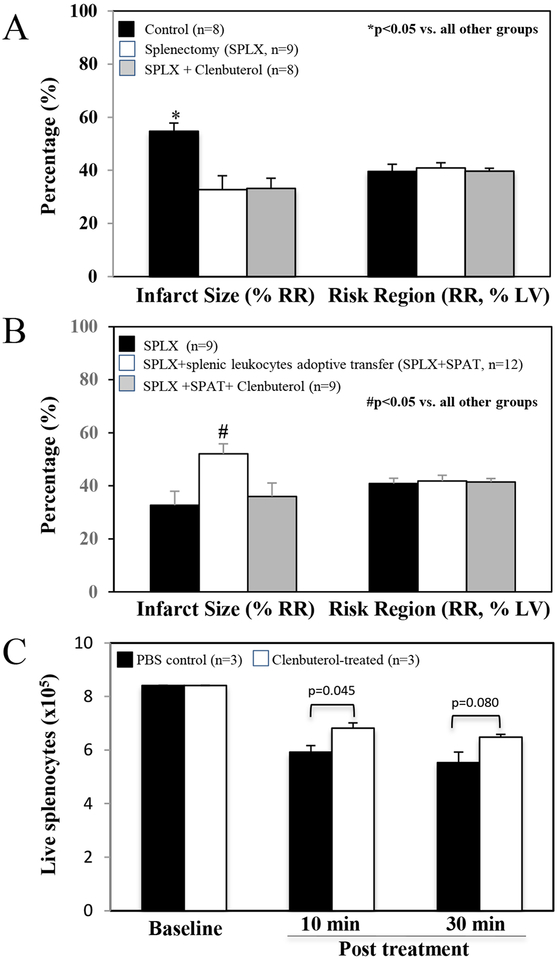

Splenectomy before ischemia attenuated infarct size to a similar extent as in Clenbuterol-treated mice (32.7±4.9 vs. control of 53.6±3.0, p<0.05). However, Clenbuterol at a dose of 1 μg per gram weight did not provide for any additional reduction in infarct size in splenectomized mice (Figure 4A). In splenectomized WT mice, splenic leukocytes adoptive transfer (SPAT) from WT mice 5 min at a dose of 5×106 before reperfusion restored the myocardial infarct size to the level of that of intact mice (52.1±37 vs. intact WT control 53.6±3.0, p<0.05). Clenbuterol-pretreated splenocytes failed to increase the infarct size in splenectomized mice (Figure 4B). Without re-suspension of the isolated WT splenocytes, PBS-treated splenocytes had a 30% loss at 10 minutes and a 34% loss at 30 min, whereas, the Clenbuterol-treated splenocytes had 15% higher live cells than the untreated at both 10 min (p<0.05) and 30 min (p=0.08) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Splenectomy (SPLX) before ischemia attenuates myocardial infarct size. Clenbuterol is ineffective in reducing infarct size in splenectomized mice.

Splenectomy was performed 5 min before occlusion of LCA. Clenbuterol was administered at a dose of 1.0 μg/g weight (i.v.) 5 min before reperfusion or incubated with splenic cell at a dose of 0.01 μg in 20×106 splenocytes cells (200 μl). A: Myocardial infarct size was significantly reduced and to a similar extent in Clenbuterol-treated (Figure 1) and splenectomized mice. However, Clenbuterol did not further reduce infarct size in splenectomized mice (n=animal number). B: splenic leukocytes adoptive transfer (SPAT) from WT mice 5 min before reperfusion restored the myocardial infarct size to the level of that of intact mice. However, Clenbuterol-pretreated splenocytes failed to increase the infarct size in splenectomized mice (n=animal number). C: Treated and control splenocytes without re-suspension were dispensed into 3 vials (n) in each group and evaluated at 10 minutes and 30 minutes using Cellometer (Nexcelom, Lawrence, MA). The live splenocytes were significantly reduced in both control and Clenbuterol-treated groups. But the reduction of cell counts in treated group was significantly less than that in control group.

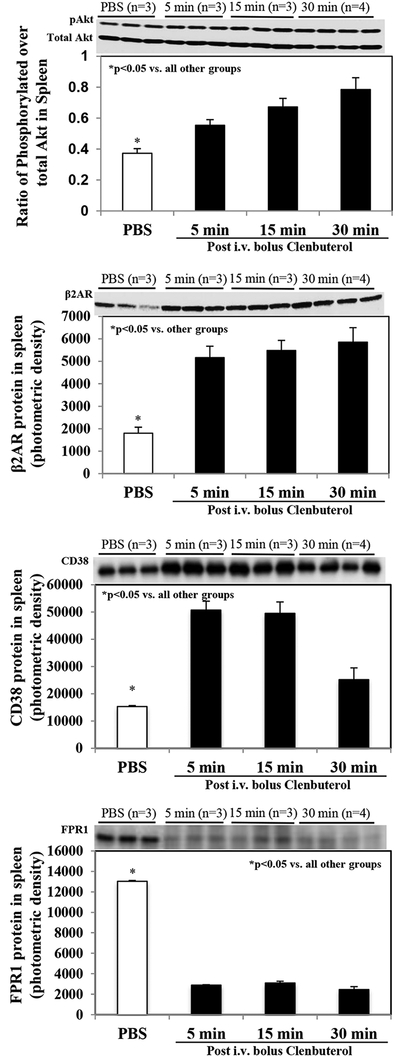

In WT mice without IRI, intravenous Clenbuterol at a dose of 1 μg per gram weight significantly increased splenic protein levels of phosphorylated Akt, β2AR and CD38 as early as 5 min post-administration, and these levels stayed elevated between 5 and 30 min following Clenbuterol treatment (Figure 5 upper 3 panels). FPR1 level was significantly reduced following Clenbuterol treatment (Figure 5 lowest panel). IL-10 levels in the spleen and plasma were only transiently elevated at 5 and 15 min following Clenbuterol treatment and then returned to normal levels at 30 min following treatment (Figure 6). IL-1β level was measured but could not detected in the spleen or the plasma (data not shown).

Figure 5. Protein levels of phosphorylated Akt, β2AR, CD38 and FPR1 in the spleen by Western Blot.

Levels of phosphorylated Akt, β2AR, CD38 and FPR1 in the spleen were serially evaluated in mice following i.v. injection of Clenbuterol at a dose of 1.0 μg/g weight. Phosphorylated Akt and β2AR levels were significantly and steadily increased within the 30-min period following treatment. At the same time, levels of CD38 also significantly elevated in the spleen but started to decline at the 30-min after treatment. Levels of FPR1 was significantly reduced within the 30-min period following treatment. In the Western blots shown at the top of each graph, n = 3 animals per group except for the 30 min group where n = 4 animals. The calculation was based on equal β-lactin levels.

Figure 6. IL-10 levels in the spleen and plasma by Western Blot.

Splenic and plasma IL-10 levels were serially evaluated in mice following i.v. injection of Clenbuterol at a dose of 1.0 μg/g body weight. Both splenic tissue and plasma IL-10 levels were significantly elevated within 5 min following Clenbuterol treatment, and then trended back down to baseline levels at 30 min following treatment. In the Western blots shown at the top of each graph, n = 3 animals per group except for the 30 min group where n = 4 animals.

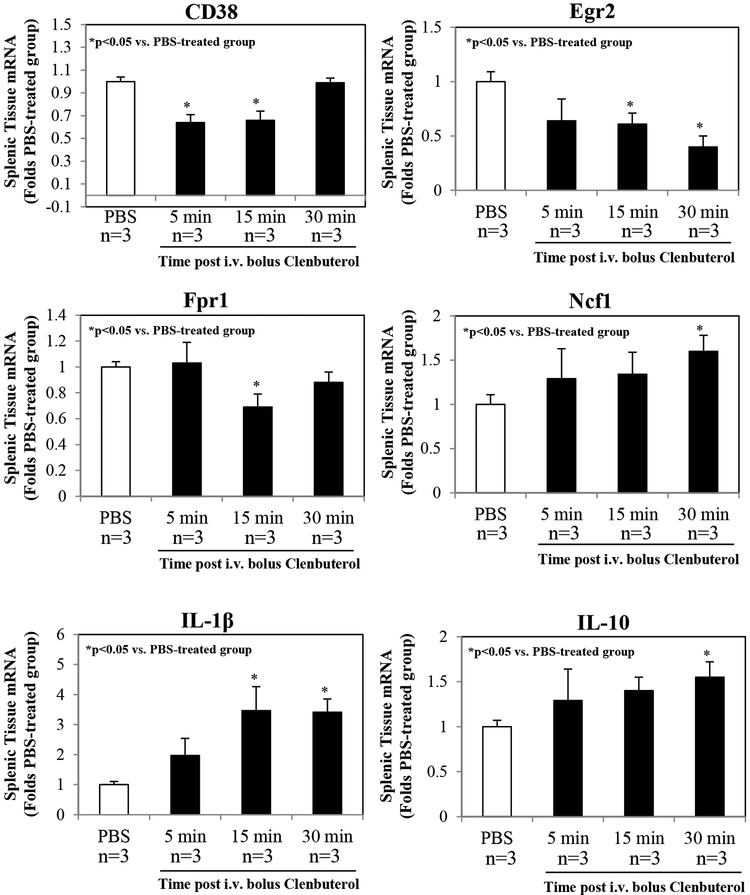

The qRT-PCR assays demonstrated that Clenbuterol reduced the expression of CD38, Egr2 and Fpr1 mRNAs in splenic tissue at 15 min following treatment, but that CD38 and Fpr1 mRNAs returned to baseline levels by 30 min after treatment. In contrast, Clenbuterol enhanced the expressions of mRNAs for Ncf1, IL-1β and IL-10 at 30 min following treatment (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis of splenic tissue following β2AR activation.

Splenic mRNA expression was serially evaluated in mice following i.v. injection of Clenbuterol at a dose of 1.0 μg/g weight. Clenbuterol decreased the levels of CD38 and Fpr1 mRNAs within 15 min following treatment, but these levels recovered to baseline by 30 min after treatment. Clenbuterol enhanced the expression of mRNAs encoding Ncf1, IL-1β and IL-10 by 30 min following treatment. Three mice per group were used.

DISCUSSION

Our work and others have demonstrated that the inflammatory response contributes importantly to post-ischemic reperfusion injury in mice8, 16. The present study investigated the effects of β2AR activation in inhibiting inflammatory responses and thereby reducing myocardial infarct size. We found that treatment with Clenbuterol, a long-acting β2AR agonist just prior to reperfusion attenuates myocardial infarct size by inhibiting inflammatory responses in the spleen through the activation of a pathway involving β2AR, Akt and IL-10. Furthermore, our results show that individual inhalational therapy with 4 β2AR agonists with different acting durations exerts similar cardioprotection against IRI as intravenous treatment. Since the inhalational therapy has significantly less chronotropic effect, this might enhance its translational potential for patients with acute coronary syndromes.

Recently, several studies have demonstrated that activation of β2AR attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury4–6. These studies explore the direct effect of β2AR agonist on cardiomyocytes. However, the anti-inflammatory effects of β2AR in mediating cardioprotection remain to be explored. β2ARs are extensively expressed in the pulmonary system, cardiac muscle and immune cells. Among the adrenergic receptors in immune cells, T and B cells exclusively express β2ARs instead of β1ARs17. In immune cells, β2AR stimulation of CD4+ T cells is known to inhibit T cell proliferation via the cAMP-dependent inhibition of nuclear factor κB activation9, 18, 19 and thus favors a Th2 polarization. β2ARs are also the predominant β-adrenergic receptors in macrophages and neutrophils. β2AR stimulation on macrophages induces an M2 phenotype among other anti-inflammatory effects9, 20, 21. β2AR agonists also inhibit neutrophils by increasing cAMP levels and reducing the production of ROS and pro-inflammatory cytokines22, 23. Thus activation of β2AR exerts a broad spectrum of inhibition of inflammatory cells and this inhibitory mechanism is entirely distinct from the direct inhibition of bronchoconstriction23. In the current study, by administering a selective β2AR agonist (Clenbuterol) upon reperfusion, we found that Clenbuterol attenuated myocardial infarct size by 30% and its infarct-limiting effect was not due to its effect on cardiomyocytes but rather to its inhibitory effect on inflammatory responses. This conclusion is supported by evidence that: 1) Clenbuterol did not afford additional reduction of myocardial infarct size in mice without spleen (Figure 4A), and 2) Clenbuterol did not reduce myocardial infarct size in IL-10 knockout mice (Figure 1). Splenic leukocytes adoptive transfer before reperfusion restored the myocardial infarct size in splenectomized mice to the level of that in intact mice. However, Clenbuterol-treated splenocytes before transfer abolished this infarct exacerbating effect of the splenocytes (Figure 4B). As the Clenbuterol washed away from the splenocytes, the systemic role of the Clenbuterol was avoided. The results indicate that the infarct-limiting effect of β2AR agonist is likely mediated by way of the spleen. Clenbuterol enhanced protein expressions of CD38, IL-10 and p-Akt and decreased expression of FPR1 (Figure 6) support the notion that activation of β2ARs modify the spleen into an anti-inflammatory phenotype. In light of previous work from our lab and others showing that CD4+ T-cells play an equally critical role in acute reperfusion injury8, 24, 25, these results suggest a pathway by which β2AR agonists stimulate β2ARs on CD4+ T-cells (probably regulatory T-cells), thus enhancing the release of IL-10, which in turn dampens the activation of immune cells (primarily neutrophils) in the spleen. This pathway then suffices to inhibit the mobilization of neutrophils into the circulatory system, followed by their homing to the infarct zone where they exacerbate infarct size during reperfusion.

Interestingly, we found that ex vivo treatment of the splenocytes with Clenbuterol, the reduction in splenocytes was significant less than that in PBS-treated splenocytes (Figure 4C). Thus, activation of β2ARs increased the tolerance of the splenocytes to anoxic injury.

Considerable evidence demonstrates that acute inflammatory responses contribute importantly to reperfusion injury7, 8, 26, 27. Furthermore, the spleen plays a central role in mediating this inflammatory response12, 16. The current study demonstrates that activation of β2AR exerts a potent anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting splenic inflammatory responses. As the Clenbuterol was administered shortly before reperfusion, the infarct-limiting effect of Clenbuterol is most likely due to its effect in inhibiting inflammatory response during post-ischemic reperfusion, rather than to its effect on the heart or on preconditioning.

A number of clinical studies have included studies on the effect of β2AR agonists in patients with ACS28, 29. However, the positive chronotropic effect of β2AR agonists might argue against its acute application in the setting of ACS30. In the present study, we found that intravenous administration of Clenbuterol increased heart rate by 36% in mice. This led us to examine the alternative administration route that has previously been used in humans with asthma (inhalational administration). Using this approach, Clenbuterol had only a modest effect on heart rate, yet with a comparable reduction in myocardial infarct size (Figures 1–3). These results raise the question of whether there might be potential for the clinical application of β2AR agonists in ACS patients. Towards this end, additional studies may be warranted to investigate the potential of inhalational therapy of β2AR agonists against myocardial IRI in animal models of different species, and perhaps human beings. Of note, β1AR is the most abundant receptor subtype31 in cardiomyocytes. Activation of β1ARs exerts pro-apoptotic effects, while activation of β2AR on cardiomyocytes produces preconditioning4–6 and anti-apoptotic effects5, 32, 33. In the current study, inhalational therapy of individual Clenbuterol, Albuterol, Salmeterol and Arformoterol was administered before index ischemia. Thus it is possible that the cardioprotective effects of inhalational β2AR agonist in the current study may involve both the preconditioning of cardiomyocytes and inhibition of pro-inflammatory responses.

Although we found that Clenbuterol inhibited the exacerbation of infarct size by splenic leukocytes and reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNAs, such as Egr2 and Fpr1, it also enhanced the expression of other pro-inflammatory mRNAs like Ncf1 and IL-1β (Figure 7). We found consistent expression of protein and mRNA in FPR1 and IL-10. However, opposite trend of changes was found in CD38 and IL-1β (Figures 6 & 7). IL-1β protein in the splenic tissue and the plasma was not detectable (data not shown). Of note, all these changes in mRNA levels were transient. It is also important to mention that these results are limited by small sample sizes. The overall net effect of Clenbuterol administration was anti-inflammatory in nature given the reduction in infarct size. Since both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine mRNAs were enhanced, it is possible that Clenbuterol might have differential effects on different inflammatory cell populations residing in the spleen.

In summary, using a mouse model of acute myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, the present study shows that a selective β2AR agonist, Clenbuterol, attenuates myocardial infarct size when it is administered just prior reperfusion. We propose that Clenbuterol inhibits pro-inflammatory responses during post-ischemic reperfusion by promoting the release of IL-10, thereby attenuating the activation of the splenic leukocytes that exacerbate infarct size upon reperfusion. The bio-effects of Clenbuterol were also evidenced by the overexpression of β2ARs on the splenic leukocytes and activation of pAkt via IL-10. Mice treated with inhalational Clenbuterol have significantly less positive chronotropic effect than with intravenous Clenbuterol, but show a similar attenuation in myocardial infarct size. These results underscore the potential for β2AR agonists in inhibiting the pro-inflammatory responses that contribute importantly to reperfusion injury. The study also has potential clinical implications because it suggests the possibility of using inhalational β2AR agonists to reduce infarct size in patients suffering acute myocardial infarction.

Acknowledgments:

This study was funded in part by University of Virginia Department of Surgery Startup Funds and an NIH R01 HL 130082 to ZY and a National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant (81400213) and a key program from Selected Overseas Chinese scholar Foundation of Tianjin to YT.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

REFERENCE

- 1.Jesinkey SR, Funk JA, Stallons LJ, Wills LP, Megyesi JK, Beeson CC, et al. Formoterol restores mitochondrial and renal function after ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;25:1157–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semkova I, Schilling M, Henrich-Noack P, Rami A, Krieglstein J. Clenbuterol protects mouse cerebral cortex and rat hippocampus from ischemic damage and attenuates glutamate neurotoxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons by induction of NGF. Brain Res 1996;717:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen B, Zhang Y, Chen L, Huang S, Li S, Yao J. Dose-effects of aorta-infused clenbuterol on spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury in rabbits. PLoS One 2013;8:e84095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhushan S, Kondo K, Predmore BL, Zlatopolsky M, King AL, Pearce C, et al. Selective beta2-adrenoreceptor stimulation attenuates myocardial cell death and preserves cardiac function after ischemia-reperfusion injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012;32:1865–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Q, Xiang J, Wang X, Liu H, Hu B, Feng M, et al. Beta(2)-adrenoceptor agonist clenbuterol reduces infarct size and myocardial apoptosis after myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion in anaesthetized rats. Br J Pharmacol 2010;160:1561–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu P, Xiang JZ, Zhao L, Yang L, Hu BR, Fu Q. Effect of beta2-adrenergic agonist clenbuterol on ischemia/reperfusion injury in isolated rat hearts and cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by hydrogen peroxide. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2008;29:661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Z, Day YJ, Toufektsian MC, Ramos SI, Marshall M, Wang XQ, et al. Infarct-sparing effect of A2A-adenosine receptor activation is due primarily to its action on lymphocytes. Circulation 2005;111:2190–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Z, Day YJ, Toufektsian MC, Xu Y, Ramos SI, Marshall MA, et al. Myocardial infarct-sparing effect of adenosine A2A receptor activation is due to its action on CD4+ T lymphocytes. Circulation 2006;114:2056–2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noh H, Yu MR, Kim HJ, Lee JH, Park BW, Wu IH, et al. Beta 2-adrenergic receptor agonists are novel regulators of macrophage activation in diabetic renal and cardiovascular complications. Kidney Int 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keranen T, Hommo T, Moilanen E, Korhonen R. beta2-receptor agonists salbutamol and terbutaline attenuated cytokine production by suppressing ERK pathway through cAMP in macrophages. Cytokine 2017;94:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosmann M, Grailer JJ, Zhu K, Matthay MA, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of beta2 adrenergic receptor agonists in experimental acute lung injury. FASEB J 2012;26:2137–2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian Y, French BA, Kron IL, Yang Z. Splenic leukocytes mediate the hyperglycemic exacerbation of myocardial infarct size in mice. Basic Res Cardiol 2015;110:39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Z, Linden J, Berr SS, Kron IL, Beller GA, French BA. Timing of adenosine 2A receptor stimulation relative to reperfusion has differential effects on infarct size and cardiac function as assessed in mice by MRI. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008;295:H2328–2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Z, Tian Y, Liu Y, Hennessy S, Kron IL, French BA. Acute hyperglycemia abolishes ischemic preconditioning by inhibiting Akt phosphorylation: normalizing blood glucose before ischemia restores ischemic preconditioning. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013;2013:329183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian Y, Zhang W, Xia D, Modi P, Liang D, Wei M. Postconditioning inhibits myocardial apoptosis during prolonged reperfusion via a JAK2-STAT3-Bcl-2 pathway. J Biomed Sci 2011;18:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tian Y, Pan D, Chordia MD, French BA, Kron IL, Yang Z. The spleen contributes importantly to myocardial infarct exacerbation during post-ischemic reperfusion in mice via signaling between cardiac HMGB1 and splenic RAGE. Basic Res Cardiol 2016;111:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanders VM. The beta2-adrenergic receptor on T and B lymphocytes: do we understand it yet? Brain Behav Immun 2012;26:195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman RD, Hunninghake GW, McArdle WL. Beta-adrenergic-receptor-mediated suppression of interleukin 2 receptors in human lymphocytes. J Immunol 1987;139:3355–3359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loop T, Bross T, Humar M, Hoetzel A, Schmidt R, Pahl HL, et al. Dobutamine inhibits phorbol-myristate-acetate-induced activation of nuclear factor-kappaB in human T lymphocytes in vitro. Anesth Analg 2004;99:1508–1515; table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grailer JJ, Haggadone MD, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, Ward PA. Induction of M2 regulatory macrophages through the beta2-adrenergic receptor with protection during endotoxemia and acute lung injury. J Innate Immun 2014;6:607–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamkin DM, Ho HY, Ong TH, Kawanishi CK, Stoffers VL, Ahlawat N, et al. beta-Adrenergic-stimulated macrophages: Comprehensive localization in the M1-M2 spectrum. Brain Behav Immun 2016;57:338–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bloemen PG, van den Tweel MC, Henricks PA, Engels F, Kester MH, van de Loo PG, et al. Increased cAMP levels in stimulated neutrophils inhibit their adhesion to human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol 1997;272:L580–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasui K, Kobayashi N, Yamazaki T, Agematsu K, Matsuzaki S, Nakata S, et al. Differential effects of short-acting beta2-agonists on human granulocyte functions. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2006;139:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathes D, Weirather J, Nordbeck P, Arias-Loza AP, Burkard M, Pachel C, et al. CD4+ Foxp3+ T-cells contribute to myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2016;101:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofmann U, Frantz S. Role of T-cells in myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2016;37:873–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bainey KR, Armstrong PW. Clinical perspectives on reperfusion injury in acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2014;167:637–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Appleyard RF, Cohn LH. Myocardial stunning and reperfusion injury in cardiac surgery. J Card Surg 1993;8:316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rorth R, Fosbol EL, Mogensen UM, Iversen K, Iversen M, Kelbaek H, et al. The importance of beta2-agonists in myocardial infarction: Findings from the Eastern Danish Heart Registry. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016;5:551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brook RD, Anderson JA, Calverley PM, Celli BR, Crim C, Denvir MA, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with an inhaled beta2-agonist/corticosteroid in patients with COPD at high cardiovascular risk. Heart 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Vries F, Pouwels S, Bracke M, Lammers JW, Klungel O, Leufkens H, et al. Use of beta2 agonists and risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with hypertension. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;65:580–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brodde OE. Beta-adrenoceptors in cardiac disease. Pharmacol Ther 1993;60:405–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang MH, Wu Y, Nguyen V, Rastogi S, McConnell BK, Wijaya C, et al. Heart protection by combination therapy with esmolol and milrinone at late-ischemia and early reperfusion. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2011;25:223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibanez B, Cimmino G, Prat-Gonzalez S, Vilahur G, Hutter R, Garcia MJ, et al. The cardioprotection granted by metoprolol is restricted to its administration prior to coronary reperfusion. Int J Cardiol 2011;147:428–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]