Abstract

Exposure to chiral polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) has been associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Their hydroxylated metabolites (OH-PCBs) are also potentially toxic to the developing human brain; however, the formation of OH-PCBs by human cytochrome P450 (P450) isoforms is poorly investigated. To address this knowledge gap, we investigated the atropselective biotransformation of 2,2’,3,4’,6-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 91), 2,2’,3,5’,6-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 95), 2,2’,3,3’,4,6’-hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 132), and 2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 136) by different human P450 isoforms. In silico predictions with ADMET Predictor and MetaDrug software suggested a role of CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4 in the metabolism of chiral PCBs. Metabolism studies with recombinant human enzymes demonstrated that CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 oxidized PCB 91 and PCB 132 in the meta position and that CYP2A6 oxidized PCB 95 and PCB 136 in the para position. CYP2B6 played only a minor role in the metabolism of PCB 95 and PCB 136 and formed meta-hydroxylated metabolites. Traces of para-hydroxylated PCB metabolites were detected in incubations with CYP2E1. No hydroxylated metabolites were present in incubations with CYP1A2 or CYP3A4. Atropselective analysis revealed P450 isoform-dependent and congener-specific atropselective enrichment of OH-PCB metabolites. These findings suggest that CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 play an important role in the oxidation of neurotoxic PCBs to chiral OH-PCBs in humans.

TOC GRAPHIC

INTRODUCTION

PCBs are a class of 209 congeners manufactured as complex mixtures containing 150 and more individual PCBs. These technical PCB mixtures were used, for example, in caulking, other building materials, and as lubricants.1,2 PCBs are still used in “totally enclosed” applications, for example as insulating fluids in transformers and capacitors. Their intentional production in the United States was banned in the late 1970s because of their persistence in the environment and evidence of adverse health outcomes associated with human exposures.3 PCBs are still produced unintentionally and, as demonstrated recently, can be detected in paints and polymer resins.4–6 In addition to these non-legacy sources, PCBs are still released from contaminated legacy sites, including hazardous waste sites and contaminated waterbodies. As a result, PCBs can be detected in environmental samples, wildlife, and humans.7,8 Exposure to PCBs has been implicated by laboratory and epidemiological studies in a broad range of adverse health outcomes, including metabolic syndrome, cancer, and developmental neurotoxicity.2,8,9 PCB congeners with multiple ortho chlorine substituents are associated with neurodevelopmental deficits in children following in utero exposure of the mother.10–12 There is also evidence that the levels of ortho chlorinated PCB congeners (i.e., PCB 95) are higher in the brains of individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders compared to normal individuals.13

Like the parent PCBs, their hydroxylated metabolites (OH-PCBs) are detected in the environment and in human samples (reviewed in14–16). A large body of evidence demonstrates OH-PCBs are also linked to adverse health outcomes, including adverse effects on the developing central nervous system. OH-PCBs can be formed by the metabolism of the parent compound by P450 enzymes.14–16 Depending on their substitution pattern, PCB congeners are metabolized by hepatic CYP1A, CYP2A or CYP2B enzymes.14 Rat CYP1A1 oxidizes non-ortho-chlorinated PCBs preferentially in the para position of the biphenyl moiety, whereas rat CYP2B1 preferentially oxidizes ortho-substituted PCB congeners in the meta position.17 PCB 136 is also metabolized by CYP2B enzymes in dogs, rats, and mice, but not rabbits to a meta-hydroxylated metabolite.18–21 A handful of studies have identified human P450 isoforms involved in the metabolism of PCBs, including CYP2A622–24 and CYP2B6.18,25,26 CYP2A6 selectively oxidizes to ortho-substituted PCB congeners, such as PCB 52 (2,2’,5,5’-tetrachlorobiphenyl) and PCB 101 (2,2’,4,5,5’-pentachlorobiphenyl), in the para position.22,23 CYP2B6 is another human P450 isoform that metabolizes ortho-substituted PCBs,25,26 but with regioselectivity that is distinctively different from CYP2A6. PCB 153 (2,2’,4,4’,5,5’-hexachlorobiphenyl) is metabolized by CYP2B6 to 2,2’,4,4’,5,5’-hexachlorobiphenyl-3-ol, a meta hydroxylated metabolite.26 Taken together, the available evidence suggests that CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 are the primary human P450 isoforms involved in the metabolism of ortho-chlorinated PCB congeners.

Seventy-two PCB congeners and 110 OH-PCB derivatives display axial chirality because they can exist as rotational isomers (or atropisomers) that are mirror images of each other.15,16,27,28 These PCB congeners have an unsymmetrical substitution pattern relative to the phenyl-phenyl bond of the biphenyl moiety. However, only nineteen PCB congeners with three or four ortho chlorine substituents form atropisomers that are stable under physiological conditions because of a hindered rotation around the phenyl-phenyl bond. The atropisomers of chiral PCBs and their OH-PCBs metabolites can be separated using gas and liquid chromatographic techniques. These PCB and OH-PCB atropisomers are stable under physiological conditions and at the temperatures used in enantioselective gas chromatographic analyses, a fact that allows studies of the disposition and toxicity of PCB atropisomers. Chiral PCBs are atropselectively oxidized to chiral OH-PCBs,18,25,29 resulting in an atropisomeric enrichment of both the parent PCB and the corresponding OH-PCB metabolites.30–32 This atropisomeric enrichment is significant because chiral PCBs and, likely their metabolites, interact atropselectively with cellular targets, such as P450 enzymes33 or the ryanodine receptor,34,35 and atropselective cause toxic outcomes.35–38

Despite their potential toxicological relevance, the atropselective formation of OH-PCBs from chiral PCBs by specific human P450 isoforms has not been investigated to date. To close this knowledge gap, we sought to identify P450 isoforms involved in the metabolism of chiral PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 and PCB 136 to specific OH-PCB metabolites and to determine if the formation of these metabolites is atropselective. These four PCB congeners were selected because of their environmental relevance15,16 and because their atropselective metabolism in human liver microsomes (HLMs) has been reported previously.29,39,40 Our results demonstrate that chiral PCBs are metabolized in a congener-specific and atropselective manner to OH-PCBs by CYP2A6, CYP2B6, and CYP2E1 in humans.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Recombinant cytochrome P450 enzymes and other materials.

Recombinant human CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2E1 and CYP3A4 co-expressed with human CYP-reductase and supplemented with purified human cytochrome b5 or co-expressed with human CYP-reductase in Escherichia coli (CYP1A2: catalog number CYP001, lot number C1A2R009A; CYP2A6, catalog number CYP064, lot number C2A6BR008; CYP2B6: catalog number CYP041, lot number C2B6BR041; CYP2E1: catalog number CYP036, lot number C2E1BR019; CYP3A4 : catalog number CYP005, lot number C3A4BR040); control bactosomes without P450 expression; and RapidStart NADPH regenerating system were purchased from Xenotech (Lenexa, KS, USA). The synthesis of the OH-PCB metabolite standards used in this study is described in the Supporting Information; for the structures and abbreviations of the OH-PCB metabolites, see Figure 1. Sources of other materials are also summarized in the Supporting Information.

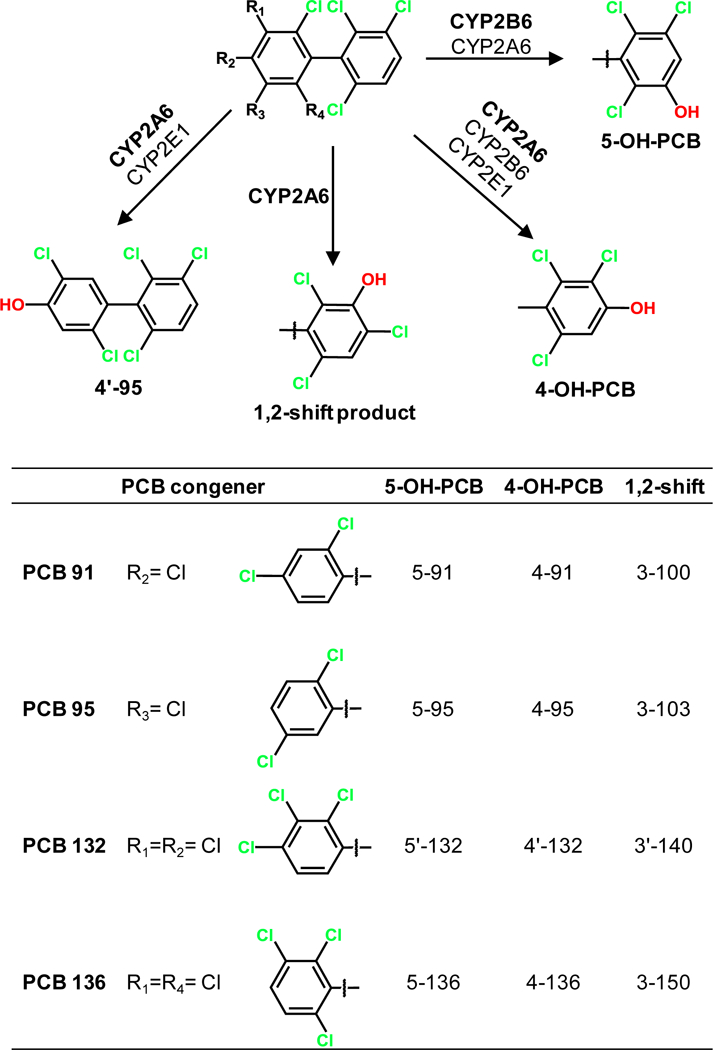

Figure 1.

Simplified metabolism scheme showing the chemical structures and abbreviations of metabolites of PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 and PCB 136 identified in incubations with human P450 enzymes. For the chemical names of the different PCB metabolites, see the Supporting Information.

In silico metabolite predictions with ADMET Predictor.

Predictions of P450 isoforms potentially involved in PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 and PCB 136 oxidative metabolism, as well as possible sites of metabolism, were carried out using ADMET Predictor software (Simulations Plus, Lancaster, CA, USA). The chemical structures were drawn in Mol file format using ChemBioDraw Ultra (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) and imported into ADMET Predictor. The Metabolism Module of ADMET Predictor was used with default settings to classify the PCBs as a substrate or not of nine human P450 Elmer, Waltham, MA) and imported into ADMET Predictor. The Metabolism Module of ADMET isoforms, CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4. The types of reactions encompassed by the models include aliphatic and aromatic carbon hydroxylation, N- and O-dealkylations, sulfoxidation, N-hydroxylation, N-oxide formation, and desulfuration. Epoxidation reactions are currently not included in the models. Also, different atomic sites of metabolic oxidation were predicted and assigned a score from 0–1000, with a higher score indicating a greater propensity of being a site of metabolism (Table S1).

In silico metabolite predictions with MetaDrug.

Predictions of P450 isoforms potentially involved in PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 and PCB 136 oxidative metabolism, as well as possible sites of metabolism, were carried out using MetaDrug (Thompson Reuters, New York, NY, USA), a systems pharmacology suite including CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4. Only four of the nine P450 isoforms used in the ADMET Predictor were included in the MetaDrug software package. PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 and PCB 136 structures were drawn and imported into MetaDrug predictor. The MetaDrug algorithm then calculated the potential of a chemical to be metabolized by the four human P450 isoforms using default settings (Tables S2-S3). Reactions predicted by MetaDrug included aromatic hydroxylation (including first and second hydroxylation) and epoxidation.

PCB biotransformation assays.

Metabolism of PCBs was investigated in incubations containing phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4), magnesium chloride (3 mM), selected recombinant human P450 enzyme (10 pmol P450/mL; see above), and the RapidStart NADPH regenerating system (diluted with 3.5 mL pure water for a final concentration of ~1 mM NADPH) as described previously.41,42 The incubation mixture was preincubated for 5 min and PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 or PCB 136 (final concentration 50 µM; DMSO ≤ 0.5% v/v) was added to start the reaction. The mixtures (2 mL final volume) were incubated for up to 60 min at 37°C. Longer incubation times (i.e., 60 min) were used for the identification of OH-PCB metabolites, whereas metabolites formation rates are reported for the shortest incubation time (i.e., 5 min) that allowed a robust quantification of the respective metabolites. The enzymatic reaction was stopped by adding ice-cold sodium hydroxide (2 mL, 0.5 M) and the incubation mixture was heated at 110 °C for 10 min. These incubations were accompanied by control incubations including phosphate buffer blanks without PCBs, DMSO incubation with control Bactosomes without PCBs, and control Bactosomes incubations with the respective PCB congener. No metabolites were detected in these control samples. The formation of PCB metabolites was linear with time for up to 30 min. If not stated otherwise, all incubations were performed in triplicate.

Extraction of PCBs and metabolites.

Extraction of the parent PCBs and their hydroxylated metabolites was conducted as reported previously.21,40,43 Briefly, samples were spiked with PCB 117 (200 ng) and 4’−159 (68.5 ng) as recovery standards. Hydrochloric acid (6 M, 1 mL) was added, followed by 2-propanol (5 mL). The samples were extracted with hexane-MTBE (1:1 v/v, 5 mL) and hexane (3 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with an aqueous potassium chloride solution (1%, 4 mL). The organic phase was transferred to a new vial, and the KCl mixture was re-extracted with hexane (3 mL). The combined organic layers were evaporated to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen. The samples were reconstituted with hexane (1 mL), derivatized with diazomethane in diethyl ether (0.5 mL) for approximately 16 h at 4 °C,44 and subjected to sulfur and sulfuric acid clean-up steps before gas chromatographic analysis.45,46

Identification of PCB metabolites.

High-resolution gas chromatography with time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC/TOF-MS) was used to identify the hydroxylated metabolites formed in incubations with recombinant P450 enzymes.40,42 In short, extracts from 60 min incubation samples were analyzed on a Waters GCT Premier gas chromatograph (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) combined with a time-of-flight mass spectrometer in the High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Facility of the University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA, USA). Methylated PCB metabolites were separated on a DB-5ms column (30 m length, 250 µm inner diameter, 0.25 µm film thickness; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using instrument parameters described previously.40,42 Analyses were carried out in the presence and in the absence of heptacosafluorotributylamine as internal standard (lock mass) to determine the accurate mass of [M]+ and obtain mass spectra of the metabolites, respectively. Metabolites were identified according to the following criteria:40,42 The average relative retention times (RRT) of the metabolites relative to PCB 204 were within 0.5% of the RRT of the respective authentic standard;47 all experimental accurate mass determinations were typically within 0.003 Da of the theoretical mass of [M+2]+ (Tables S4-S7); and the isotope pattern of [M]+ matched the theoretical abundance ratios of pentachlorinated (1: 1.6: 1 for PCBs 91 and 95) or hexachlorinated (1: 1.9: 1.6:0.7, for PCBs 132 and 136) biphenyl derivatives within a 20 % error. Representative GC-TOF/MS chromatograms of OH-PCB metabolites (as methylated derivatives) and the corresponding analytical standards are shown in the Supporting Information (Figures S1-S23). Fragmentation patterns similar to those observed in this study were reported in earlier studies for meta or para, but not ortho-substituted derivatives of monohydroxylated PCBs.48–51

Quantification of metabolite levels.

To quantify the levels of hydroxylated PCB metabolites (as methylated derivatives), sample extracts were analyzed on an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph with a 63Ni-micro electron capture detector (µECD) and a SPB-1 capillary column (60 m length, 250 µm inner diameter, 0.25 µm film thickness; Supelco, St Louis, MO, USA).20,40,42 PCB 204 was added as internal standard (volume corrector) prior to analysis, and concentrations of hydroxylated metabolites (as methylated derivatives) were determined using the internal standard method.21,43,52 Levels of PCB and its metabolites were not adjusted for recovery to facilitate a comparison with earlier studies.40,52 The average RRTs of the metabolites, calculated relative to PCB 204, were within 0.5% of the RRT for the respective standard.47 Rates of PCB metabolite formation, OH-PCB levels, OH-PCB percent relative to the sum OH-PCBs (ΣOH-PCBs) and QA/QC data are presented in the Supporting Information (Tables S8-S13).

Atropselective gas chromatographic analyses.

Atropselective analyses were carried out with the 60 min incubations described above using an Agilent 6890 or Agilent 7890A GC equipped with the following capillary columns: ChiralDex B-DM (BDM) for PCB 91, 5–91, 4–91, PCB 95, 3–103, 4’−95, 5– 95 and 4–95; Chirasil-Dex (CD) for PCB 132, 5’−132, PCB 136, 3–150, 5–136 and 4–136; ChiralDex G-TA (GTA) for 3–100 and 3’−140; and Cyclosil-B (CB) for PCB 136, 3–150, 4–136 and 5–136 (see Table S14 for column details). Atropisomers of 4’−132 could not be resolved on any of the columns used.43 The helium flow was 3 mL/min. The injectors and detectors were maintained at 250 °C. Temperature programs, enantiomeric fractions (EFs), resolutions and retention times of analytical standards are summarized in Table S15. EF values are summarized in Table S16 and were calculated by the drop valley method53 as EF = Area E1/(Area E1 + Area E2), where Area E1 and Area E2 denote the peak area of the first (E1) and second (E2) eluting atropisomer, to facilitate a comparison with earlier studies.21,39,40 Representative chromatograms are shown in Figures S24-S33.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Prediction of hydroxylated PCB metabolites.

PCBs, such as PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 and PCB 136, can be metabolized either by direct insertion of an oxygen atom into an aromatic C-H bond or via an arene oxide intermediate54,55 to a considerable number of OH-PCB metabolites. For example, PCB 95 can potentially be oxidized to a total of 10 OH-PCB congeners.56 To guide our metabolism studies with recombinant human P450 enzymes, metabolites of these four PCB congeners were initially predicted using ADMET Predictor and MetaDrug, two commercial ADME software packages.

ADMET Predictor suggested that CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2E1 and CYP3A4, but not CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 or CYP2D6 metabolize the four PCB congeners under investigation at the para and meta positions, in particular in the 2,3,6-trichlorophenyl ring (Figure 2, Table S1). As shown in the generic metabolism scheme in Figure 1, the metabolites formed by these P450 isoforms were predicted to be 5–91 and 4–91 for PCB 91; 4–95 and 4’−95 for PCB 95; 5’−132 and 4’−132 for PCB 132; and 4–136 for PCB 136.

Figure 2. In silico predictions and in vitro incubations show that chiral PCBs are metabolized to hydroxylated metabolites by human CYP2A6, CYP2B6, and CYP2E1.

ADMET Predictor and Metadrug software packages were initially used to predict human P450 isoforms involved in the metabolism of chiral PCBs. Metabolism studies with recombinant human P450 enzymes were performed to assess if the P450 isoforms identified in silico indeed form OH-PCBs. In vitro metabolism studies were carried out using the following incubation conditions: 50 µM PCB; 5-minute incubation at 37 ºC; 10 pmol/mL P450 content; see the Experimental Section for additional details.18,40 Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, n = 3. a ✓ indicates that the OH-PCB metabolite was predicted to be formed. b In vitro metabolite formation rate (+) below 80 fmol/pmol P450/min, (++) between 80 and 180 fmol/pmol P450/min, (+++) between 180 and 420 fmol/pmol P450/min and (++++) above 420 fmol/pmol P450/min. c Experimental data for incubation with CYP2E1 for 60 min are shown. d Peak corresponding to this metabolite was below the limit of detection (LOD).

MetaDrug predicted the oxidation of chiral PCBs by CYP1A2 and CYP2B6, but not CYP2D6 or CYP3A4 in para and meta position (Figure 2, Tables S2-S3). Specifically, the metabolites predicted by MetaDrug were 5–91 and 4–91 for PCB 91; 5–95 and 4–95 for PCB 95; 5’−132 and 4’−132 for PCB 132; and 5–136 and 4–136 for PCB 136. In addition, MetaDrug predicted the oxidation of chiral PCBs to arene oxide, dihydrodiol, and other metabolites, thus suggesting more complex metabolic pathways for PCBs than predicted by ADMET Predictor.

Biotransformation assays with recombinant human P450 enzymes.

To confirm which human P450 isoforms are involved in the metabolism of chiral PCBs to OH-PCBs, racemic PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 and PCB 136 were incubated with the recombinant human P450 isoforms identified with ADMET Predictor and MetaDrug. Incubations were initially performed for 60 min to achieve metabolite levels suitable for high-resolution GC-TOF/MS analysis (Figures 3 and S1-S23; Tables S4-S7). Additional metabolism studies were performed to determine the formation rates of individual OH-PCBs (analyzed as methylated derivatives) by individual P450 isoforms using GC-µECD. Detectable levels of OH-PCB metabolites were observed in incubations with CYP2A6, CYP2B6, and CYP2E1, whereas no metabolites were detected in incubations with CYP1A2 or CYP3A4 (Tables S9-S10). Similarly, recombinant CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 did not metabolize PCB 95 or PCB 52, a PCB congener structurally similar to PCB 95 and PCB 136; however, these earlier study also did not observe any oxidation of either PCB congener by CYP2B6 and CYP2E1.22,24 No arene oxide or dihydrodiol metabolites were detected in the GC-TOF/MS or GC-µECD analyses, most likely because the extraction procedure was not designed to capture these metabolites.18 Moreover, no ortho-hydroxylated and dihydroxylated metabolites were observed under the incubation conditions employed in this study. Overall, both ADMET Predictor and MetaDrug identified the two major P450 isoforms involved in the metabolism of chiral PCB congeners; however, both software packages had limitations: For example, ADMET Predictor did not predict PCB metabolism via arene oxide intermediates (discussed below), and MetaDrug did not predict that oxidation of PCBs by CYP2E1. Moreover, the formation of the 1,2-shift products was not predicted by either software package, whereas both ADMET Predictor and Metadrug predicted PCB metabolism by CYP1A2, a P450 isoform that does not metabolize PCB congeners with multiple ortho substituents based on published metabolism studies.17,22,24,29

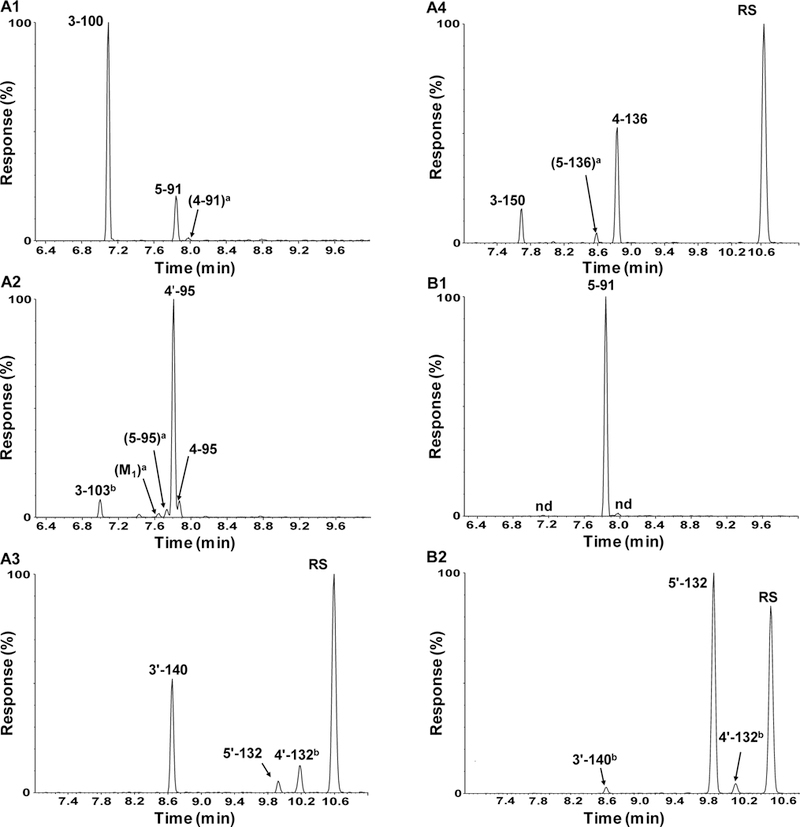

Figure 3. Chiral PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 and PCB 136 are oxidized in a congener-specific manner by human CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 to OH-PCBs.

Representative GC-TOF chromatograms of OH-PCB metabolites (as methylated derivatives) in extracts from incubations of CYP2A6 with (A1) PCB 91; (A2) PCB 95; (A3) PCB 132; and (A4) PCB 136; and in extracts from incubations of CYP2B6 with (B1) PCB 91 and (B2) PCB 132. Incubation conditions were as follow: 50 μM PCB; 60 minutes, 37 ºC; and 10 pmol/mL P450. See the Supporting Information for the corresponding mass spectra. The metabolites were separated on DB5-ms column; see the Experimental Section above for additional details. a No mass spectra were obtained due to low analyte levels. However, the peak was identified by matching the retention time with the authentic standard. b Accurate mass not determined due to background carbon interference. RS, peak corresponding to the recovery standard.

CYP2A6-mediated oxidation of chiral PCBs.

Racemic PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 and PCB 136 were metabolized by CYP2A6. The overall rank order of the metabolite formation by CYP2A6, based on the ΣOH-PCBs, was PCB 91 > PCB 95 > PCB 136 > PCB 132 (Figure 4, Tables S9-S10). PCB 91 was oxidized by CYP2A6 to 3–100 (1,2-shift product), 5–91 and 4–91. The major metabolite of PCB 91 was 3–100, which represented 81 ± 2 % of ΣOH-PCBs of PCB 91 (Table S11). The major PCB 95 metabolite formed by CYP2A6 was 4’−95 (Figure 4B) and represented 74.6 ± 0.2 % of the ΣOH-PCBs of PCB 95 (Table S11). Minor metabolites 3–103 (1,2-shift product), 5–95 and 4–95 were detected in incubations of PCB 95 with CYP2A6, with a rank order of 4’−95 >> 4–95 > 3–103 > 5–95. Besides, an unknown minor metabolite M-95 was detected. Based on earlier metabolism studies with PCB 95, we posit that this metabolite is 3’−95.40,43,56,57 OH-PCBs 3’−140 (1,2-shift product), 5’−132 and 4’−132 were formed from PCB 132 in experiments with recombinant CYP2A6 (Figure 4C). The major metabolite was 3’−140 and represented 67 ± 1% of the ΣOH-PCBs of PCB 132 (Table S11). Metabolites were formed in the rank order 3’−140 >> 4’−132 > 5’−132. PCB 136 was oxidized by CYP2A6 to 3–150 and 4– 136 (1,2-shift product) (Figure 4D). Also, a peak with a retention time matching 5–136 was observed. The major metabolite was 4–136 with 64 ± 2% of the ΣOH-PCBs of PCB 136 (Table S11). The rank order of metabolite formation was 4–136 >> 5–136 ~ 3–150.

Figure 4. Formation rates of PCB metabolites (analyzed as methylated derivatives) reveal that (A) PCB 91; (B), PCB 95, (C) PCB 132 and (D) PCB 136 are metabolized to OH-PCBs by human CYP2A6, CYP2B6, and CYP2E1.

Metabolism studies were performed using the following incubation conditions: 50 µM PCB; 5-minute incubation at 37 ºC; 10 pmol/mL P450 content; NADPH regenerating system.40 c Incubation with CYP2E1 for 60 min. d Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, n = 3.

The formation of the 1,2-shift product of PCB 91 and PCB 132 demonstrates that the oxidation of both PCB congeners by CYP2A6 involves an arene oxide intermediate in the 2,3,6-trichloro substituted phenyl ring that subsequently rearranges to a hydroxylated 1,2-shift product. Although both PCB 95 and PCB 136 are also metabolized by CYP2A6, the site of hydroxylation and the resulting metabolite profiles were drastically different compared to PCB 91 and PCB 132. It is possible that the oxidation of PCB 95 and PCB 136 by CYP2A6 occurs via different arene oxide intermediates, thus resulting in different OH-PCB rearrangement products. Alternatively, interactions within the active site may affect the rearrangement of the arene oxide, leading to preferential para-oxidation for PCB 95 and PCB 136.

CYP2B6-mediated oxidation of chiral PCBs.

Based on the ΣOH-PCB, CYP2B6 metabolized the four PCB congeners investigated with a rank order PCB 91 >> PCB 132 >> PCB 95 > PCB 136. Except for PCB 91, ΣOH-PCB formation rates were lower with CYP2B6 compared to CYP2A6. PCB 91 was metabolized by CYP2B6 to 3–100 (1,2-shift product), 5–91 and 4–91 (Figure 4A, Table S12). The major metabolite formed by CYP2B6 was 5–91 and accounted for 98.4 ± 0.1 % of the ΣOH-PCBs of PCB 91 (Table S11). Only traces of 3–100 and 4–91 were detected in incubations with CYP2B6. Interestingly, CYP2B6 oxidized PCB 95 in the meta position to yield 5–95; however, the formation rates of 5–95 by CYP2B6 were 2-times lower compared to CYP2A6 (Table S12). PCB 132 was metabolized by CYP2B6 to 3’−140 (1,2-shift product), 5’−132 and 4’−132, with a rank order 5’−132 >> 3’−140 > 4’−132 (Figure 4C). The major metabolite, 5’−132, represented 81 ± 7 % of the ΣOH-PCBs (Table S11). PCB 136 formed 3–150 (1,2-shift product), 5–136 and 4–136 in experiments with CYP2B6, albeit with relatively low formation rates (Figure 4D). The major metabolite was 5–136 and accounted for 94 ± 0.3 % of the ΣOH-PCBs.

CYP2E1-mediated oxidation of chiral PCBs.

Recent studies suggest that CYP2E1 bioactivates PCB to mutagenic metabolites.58,59 Consistent with these observations and the in silico predictions (Figure 2), CYP2E1 metabolized PCB 91 to 4–91, PCB 95 to 4–95 and 4’−95, and PCB 136 to 4–136 (Figure 4). However, the OH-PCB formation rates were low and longer incubation times 60 minutes were needed to form detectable levels of metabolites of PCB 91, PCB 95 and PCB 136. No OH-PCB metabolites were detected in incubations of PCB 132 with CYP2E1.

Comparison of OH-PCB profiles formed by HLMs vs. recombinant P450 isoforms.

The metabolism of PCB 91, PCB 95, PCB 132 and PCB 136 with pooled HLMs has been reported previously.29,39,40,55 These studies revealed congener-specific differences, but also similarities in the metabolism of these four PCB congeners. PCB 91 was primarily metabolized by HLMs to the 1,2-shift product, 3–100. The other metabolites, 5–91, 4–91 and 4,5–91, were only minor metabolites. The present study suggests that 3–100 is most likely formed by CYP2A6, whereas both CYP2B6 and CYP2A6 contribute to the formation of 5–91. It is likely that several P450 isoforms are involved in the formation of 4–91. Analogously, PCB 132 was also metabolized by HLMs to the 1,2-shift product, 3’−140, and 5’-132; while 4’−132 was a minor metabolite formed from PCB 132 in studies with HLMs. Based on our study, 3’−140 and 4’−132 are primarily formed by CYP2A6, whereas both CYP2B6 and CYP2A6 likely contribute to the formation of 5’−132 in metabolism studies with HLMs.

The metabolite profiles of PCB 95 and PCB 136 observed in metabolism studies with HLMs were distinctively different from those observed for PCB 91 and PCB 132. Briefly, PCB 95 was primarily metabolized to 4’−95 in studies with HLMs, with several other OH-PCBs being minor metabolites.40 The ratio of 3–103: 5–95: 4–95: 4’−95 observed with HLMs were comparable to the profile observed with recombinant CYP2A6 (0.11: 0.06: 0.12: 1 vs. 0.11: 0.04: 0.19: 1, respectively). Thus, CYP2A6 appears to be the main P450 isoform involved in the metabolism of PCB 95 to 3–103, 4–95 and 4’−95 in HLMs, possibly with some contribution of other P450 isoforms, including CYP2B6 and CYP2E1. Similar to PCB 95, PCB 136 was metabolized by HLMs to 4–136, with 5–136 being a minor metabolite.29 The ratio of 5–136: 4–136 reported in one study29 (0.39: 1) was somewhat similar to the ratio formed with CYP2A6 (0.3: 1), whereas a different 5–136: 4–136 ratio (1.3: 1) has been observed in an earlier study.55 Based on our results, CYP2A6 is involved in the formation of 4–136, and both CYP2B6 and CYP2A6 likely contribute to the formation of 5–136 by HLMs. Differences in the CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 levels in HLMs likely explain the different 5–136: 4–136 ratios observed in metabolism studies with different HLM preparations.29,55

Atropselective formation of OH-PCBs by CYP2A6.

Atropselective analyses revealed congener and P450 isoform-specific differences in the formation of OH-PCB metabolites and allowed a comparison with EF values of OH-PCBs observed in incubations with HLMs (Table S17). A pronounced enrichment of the first eluting atropisomer (E1) of the 1,2-shift products was observed in incubations of CYP2A6 with PCB 91, PCB 95 or PCB 132, with EF values of 0.92, 0.99 and 0.96 for 3– 100, 3–103 and 3’−140, respectively (Figure 5; Table S16). Analogously, E1-3–100, E1-3–103 and E1-3’-140 were formed atropselectively in incubations of these three PCB congeners with HLMs.39 The EF values of 3–100 and 3’−140 formed in incubations with HLMs were 0.85 and 0.84, respectively. In contrast, the second eluting atropisomer (E2) of 3–150, the 1,2-shift product formed from PCB 136, was enriched in incubations with CYP2A6 (EF = 0.01) (Figure 5D). E2-3–150 was also enriched in incubations with HLMs (EF = 0.01, Table S16). Overall, the atropisomeric enrichment of the 1,2-shift products observed in incubation with HLMs is consistent with their formation by CYP2A6.

Figure 5. OH-PCB metabolites are formed atropselectively from (A) PCB 91, (B) PCB 95, (C) PCB 132 and (D) PCB 136 in incubations with recombinant human CYP2A6 (dark red), CYP2B6 (orange) and CYP2E1 (light green) enzymes.

No metabolites were detected in experiments with CYP1A2 and CYP3A4. Open circles (○), diamonds (◇) and squares (□) indicate 1,2-shift, meta- and para-substituted metabolites, respectively. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3; error bars are typically hidden behind the symbols. Metabolism studies were performed using the following incubation conditions: 50 μM PCB; 60 min incubation at 37 ºC; 10 pmol/mL P450 content; and ~1 mM NADPH regenerating system. Metabolites were separated on BDM (5–91, 4–91, 3–103 and 4’−95); GTA (3–100, 3’−140) or CD columns (5’−132, 3–150, 5– 136 and 4–136). EF value of 5–95 and 4–95 could not be calculated due to co-elution of E1-5–95 and E1-4–95.

An enrichment of E2-5–91, E2-5’−132 and E2-5–136 was observed in incubations with CYP2A6, with EF values of 0.35, 0.28 and 0.44, respectively (Figure 5, Table S16). EF values of 5–95 could not be determined because of the co-elution of E1-5–95 with E1-4–95; however, an enrichment of E2-5–95 was observed (Figure S27). The enantiomeric enrichment was less pronounced compared to the enrichment observed with the 1,2-shift metabolites, with E2-5–136 being near racemic. Consistent with studies with recombinant CYP2A6, an enrichment of the E2-atropisomer of the 5-hydroxylated metabolites of PCB 91, PCB 132 and PCB 136 was also observed in metabolism studies with HLMs, with EF values following the order 5’−132 (EF = 0.19) > 5–136 (EF = 0.31) > 5–91 (EF = 0.47).29,39

E2-4–91, E2-4’−95 and E2-4–136 were formed preferentially in experiments with CYP2A6. The corresponding EF values were 0.39 for 4–91, 0.09 for 4’−95 and 0.10 for 4–136. Although an EF value could not be determined for 4–95, an enrichment of E2-4–95 was observed (Figure S27). An enrichment of E2-4–95, E2-4’−95 and E2-4–136 was also present in incubations with HLMs. In contrast, enrichment of E1-4–91 was observed in studies with HLMs (EF = 0.75). Because 4’−95 is the major metabolite formed by CYP2A6, the enrichment of E2-4’−95 likely explains the enrichment of aR-PCB 95 [(−)-PCB 95] reported by an earlier metabolism study with CYP2A6;24 however, metabolism studies with pure PCB 95 atropisomers are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Atropselective formation of OH-PCBs by CYP2B6 and CYP2E1.

The most pronounced enrichment in incubations with CYP2B6 was observed for E2-5’−132 (EF 0.32), whereas 5–91 and 5–136 were near-racemic, with EF values of 0.49 and 0.50, respectively (Figure 5, Table S16). This atropisomeric enrichment is consistent with a more pronounced enrichment of E2-5–132 in experiments with HLMs (Table S17). Additional studies are needed to assess if the enrichment of E2-5’−132 explains the more rapid elimination of E1-PCB 132 [(−)-PCB 132] observed in an earlier study with recombinant CYP2B6.25 E1-5–95 was enriched in incubations with CYP2B6 (Figure S27). E1-4–91 (EF = 0.60) was enriched in CYP2B6 incubations with PCB 91. In metabolism studies with CYP2E1, E1-4–91 and E2-5– 91 were enriched in incubations with PCB 91 (Figure 5, Table S16). E1-4’−95 and E1-4–136 were formed preferentially by CYP2E1 from PCB 95 and PCB 136, respectively.

Implications for future environmental and human studies.

This study demonstrates the enantioselective formation of OH-PCBs by human CYP2A6, CYP2B6, and CYP2E1 and suggests that CYP2A6 is the major P450 enzyme driving the atropselective metabolism of PCBs in HLMs. Importantly, the metabolism of chiral PCB congeners by CYP2A6 appears to involve arene oxide intermediates, as suggested by the formation of 1,2-shift products as major metabolites. In contrast, 1,2-shift products are only minor PCB metabolites formed in rodents, with CYP2B enzymes being major P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of chiral PCBs.15 As such, this study provides novel insights into the metabolism of PCBs to potentially neurotoxic OH-PCBs by human P450 enzymes and adds to the available evidence that there are significant differences in the OH-PCB profiles formed in humans vs. other, toxicologically relevant species (i.e., mice and rats). At the same time, this study raises several fundamental questions. It is still unknown if the formation of other OH-PCBs observed in this study also involves an arene oxide intermediate or occurs by direct insertion of an oxygen atom into an aromatic C-H bond. Moreover, the metabolic fate of PCB arene oxides in humans remains unknown. Specifically, it is unclear to which extent arene oxide intermediates are metabolized to dihydrodiols, conjugated with glutathione and other cellular nucleophiles; and if these reactions are atropselective. Moreover, PCB can atropselectively change the expression of hepatic P450 enzymes,36,60,61 most likely by mechanisms involving pregnane X receptor (PXR) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR).62 Finally, the activity of CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 in the human liver displays considerable inter-individual variability, and both P450 enzymes are highly polymorphic.63,64 Systematic studies of the atropselective metabolism of PCBs by polymorphic P450 enzymes are therefore warranted. Indeed, limited studies with single donor HLMs demonstrate considerable inter-individual variability in the formation of specific OH-PCBs.39,40 Finally, because of the complex metabolite profiles formed in vivo, future studies of the metabolism of PCBs should employ not only conventional approaches but also expand state-of-the-art non-targeted metabolomics approaches to include enantioselective analyses.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Lynn Teesch and Mr. Vic Parcell from the High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry facility, University of Iowa for help with the chemical analysis. We thank Drs. Sudhir Joshi, Sandhya Vyas and Huimin Wu for the synthesis of the PCB metabolite standards used in this study.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported by grants ES027169, ES013661, and ES005605 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. Moreover, the findings and conclusions in this presentation have not been formally disseminated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry and should not be construed to represent any agency determination or policy.

REFERENCES

- 1.EPA Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) https://www.epa.gov/pcbs (accessed 12/03/2018),

- 2.ATSDR Toxicological profile for polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) U.S. Dept. Health Services, Public Health Service; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.EPA EPA Bans PCB Manufacture; Phases Out Uses https://archive.epa.gov/epa/aboutepa/epa-bans-pcb-manufacture-phases-out-uses.html (accessed 2/13/2018),

- 4.Herkert NJ; Jahnke JC; Hornbuckle KC Emissions of tetrachlorobiphenyls (PCBs 47, 51, and 68) from polymer resin on kitchen cabinets as a non-Aroclor source to residential air. Environ. Sci. Technol 2018, 52, 5154–5160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu D; Hornbuckle KC Inadvertent polychlorinated biphenyls in commercial paint pigments. Environ. Sci. Technol 2010, 44, 2822–2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anezaki K; Nakano T Concentration levels and congener profiles of polychlorinated biphenyls, pentachlorobenzene, and hexachlorobenzene in commercial pigments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int 2014, 21, 998–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hornbuckle KC; Carlson DL; Swackhamer DL; Baker JE; Eisenreich SJ, Polychlorinated biphenyls in the Great Lakes. In: Hites R (Ed.), The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry, j: Persistent Organic Pollutants in the Great Lakes, Springer: 2006; pp 13–70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robertson LW; Hansen LG, PCBs: Recent Advances in Environmental Toxicology and Health Effects University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen L, The ortho side of PCBs: Occurrence and disposition Kluwer Academic Publishers: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen YC; Yu ML; Rogan WJ; Gladen BC; Hsu CCA 6-year follow-up of behavior and activity disorders in the Taiwan Yu-cheng children. Am. J. Public Health 1994, 84, 415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haijima A; Lesmana R; Shimokawa N; Amano I; Takatsuru Y; Koibuchi N Differential neurotoxic effects of in utero and lactational exposure to hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyl (OH-PCB 106) on spontaneous locomotor activity and motor coordination in young adult male mice. J. Toxicol. Sci 2017, 42, 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otake T; Yoshinaga J; Enomoto T; Matsuda M; Wakimoto T; Ikegami M; Suzuki E; Naruse H; Yamanaka T; Shibuya N; Yasumizu T; Kato N Thyroid hormone status of newborns in relation to in utero exposure to PCBs and hydroxylated PCB metabolites. Environ. Res 2007, 105, 240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell MM; Woods R; Chi LH; Schmidt RJ; Pessah IN; Kostyniak PJ; LaSalle JM Levels of select PCB and PBDE congeners in human postmortem brain reveal possible environmental involvement in 15q11-q13 duplication autism spectrum disorder. Environ. Mol. Mutagen 2012, 53, 589–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimm FA; Hu D; Kania-Korwel I; Lehmler HJ; Ludewig G; Hornbuckle KC; Duffel MW; Bergman A; Robertson LW Metabolism and metabolites of polychlorinated biphenyls. Crit. Rev. Toxicol 2015, 45, 245–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kania-Korwel I; Lehmler HJ Chiral polychlorinated biphenyls: absorption, metabolism and excretion--A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int 2016, 23, 2042–2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehmler HJ; Harrad SJ; Huhnerfuss H; Kania-Korwel I; Lee CM; Lu Z; Wong CS Chiral polychlorinated biphenyl transport, metabolism, and distribution: A review. Environ. Sci. Technol 2010, 44, 2757–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaminsky LS; Kennedy MW; Adams SM; Guengerich FP Metabolism of dichlorobiphenyls by highly purified isozymes of rat liver cytochrome P-450. Biochemistry 1981, 20, 7379–7384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu Z; Kania-Korwel I; Lehmler H-J; Wong CS Stereoselective formation of mono- and di-hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls by rat cytochrome P450 2B1. Environ. Sci. Technol 2013, 47, 12184–12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waller SC; He YA; Harlow GR; He YQ; Mash EA; Halpert JR 2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-Hexachlorobiphenyl hydroxylation by active site mutants of cytochrome P450 2B1 and 2B11. Chem. Res. Toxicol 1999, 12, 690–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu X; Kania-Korwel I; Chen H; Stamou M; Dammanahalli KJ; Duffel M; Lein PJ; Lehmler HJ Metabolism of 2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 136) atropisomers in tissue slices from phenobarbital or dexamethasone-induced rats is sex-dependent. Xenobiotica 2013, 43, 933–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X; Pramanik A; Duffel MW; Hrycay EG; Bandiera SM; Lehmler HJ; Kania-Korwel I 2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-Hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 136) is enantioselectively oxidized to hydroxylated metabolites by rat liver microsomes. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2011, 24, 2249–2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimada T; Kakimoto K; Takenaka S; Koga N; Uehara S; Murayama N; Yamazaki H; Kim D; Guengerich FP; Komori M Roles of human CYP2A6 and monkey CYP2A24 and 2A26 cytochrome P450 enzymes in the oxidation of 2,5,2’,5’-tetrachlorobiphenyl. Drug Metab. Dispos 2016, 44, 1899–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGraw JE Sr.; Waller DP Specific human CYP 450 isoform metabolism of a pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB-IUPAC# 101). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2006, 344, 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagayoshi H; Kakimoto K; Konishi Y; Kajimura K; Nakano T Determination of the human cytochrome P450 monooxygenase catalyzing the enantioselective oxidation of 2,2’,3,5’,6-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 95) and 2,2’,3,4,4’,5’,6-heptachlorobiphenyl (PCB 183). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int 2018, 25, 16420–16426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warner NA; Martin JW; Wong CS Chiral polychlorinated biphenyls are biotransformed enantioselectively by mammalian cytochrome P-450 isozymes to form hydroxylated metabolites. Environ. Sci. Technol 2009, 43, 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ariyoshi N; Oguri K; Koga N; Yoshimura H; Funae Y Metabolism of highly persistent PCB congener, 2,4,5,2’,4’,5’-hexachlorobiphenyl, by human CYP2B6. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1995, 212, 455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhakal K; Gadupudi GS; Lehmler HJ; Ludewig G; Duffel MW; Robertson LW Sources and toxicities of phenolic polychlorinated biphenyls (OH-PCBs). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int 2018, 25, 16277–16290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konig WA; Gehrcke B; Runge T; Wolf C Gas-chromatographic separation of atropisomeric alkylated and polychlorinated-biphenyls using modified cyclodextrins. J. High Res. Chrom 1993, 16, 376–378. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu X; Kammerer A; Lehmler HJ Microsomal oxidation of 2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 136) results in species-dependent chiral signatures of the hydroxylated metabolites. Environ. Sci. Technol 2014, 48, 2436–2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu X; Barnhart C; Lein PJ; Lehmler HJ Hepatic metabolism affects the atropselective disposition of 2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 136) in mice. Environ. Sci. Technol 2015, 49, 616–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kania-Korwel I; Barnhart CD; Stamou M; Truong KM; El-Komy MH; Lein PJ; Veng-Pedersen P; Lehmler HJ 2,2’,3,5’,6-Pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 95) and its hydroxylated metabolites are enantiomerically enriched in female mice. Environ. Sci. Technol 2012, 46, 11393–11401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kania-Korwel I; Vyas SM; Song Y; Lehmler HJ Gas chromatographic separation of methoxylated polychlorinated biphenyl atropisomers. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1207, 146–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kania-Korwel I; Hrycay EG; Bandiera SM; Lehmler HJ 2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-Hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 136) atropisomers interact enantioselectively with hepatic microsomal cytochrome P450 enzymes. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2008, 21, 1295–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pessah IN; Lehmler HJ; Robertson LW; Perez CF; Cabrales E; Bose DD; Feng W Enantiomeric specificity of (−)-2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-hexachlorobiphenyl toward ryanodine receptor types 1 and 2. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2009, 22, 201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng W; Zheng J; Robin G; Dong Y; Ichikawa M; Inoue Y; Mori T; Nakano T; Pessah IN Enantioselectivity of 2,2’,3,5’,6-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 95) atropisomers toward ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and their influences on hippocampal neuronal networks. Environ. Sci. Technol 2017, 51, 14406–14416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pencikova K; Brenerova P; Svrzkova L; Hruba E; Palkova L; Vondracek J; Lehmler HJ; Machala M Atropisomers of 2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 136) exhibit stereoselective effects on activation of nuclear receptors in vitro. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int 2018, 25, 16411–16419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang D; Kania-Korwel I; Ghogha A; Chen H; Stamou M; Bose DD; Pessah IN; Lehmler HJ; Lein PJ PCB 136 atropselectively alters morphometric and functional parameters of neuronal connectivity in cultured rat hippocampal neurons via ryanodine receptor-dependent mechanisms. Toxicol. Sci 2014, 138, 379–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lehmler HJ; Robertson LW; Garrison AW; Kodavanti PR Effects of PCB 84 enantiomers on [3H]-phorbol ester binding in rat cerebellar granule cells and 45Ca2+-uptake in rat cerebellum. Toxicol. Lett 2005, 156, 391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uwimana E; Li X; Lehmler HJ Human liver microsomes atropselectively metabolize 2,2’,3,4’,6-pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 91) to a 1,2-shift product as the major metabolite. Environ. Sci. Technol 2018, 52, 6000–6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uwimana E; Li X; Lehmler HJ 2,2’,3,5’,6-Pentachlorobiphenyl (PCB 95) is atropselectively metabolized to para hydroxylated metabolites by human liver microsomes. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2016, 29, 2108–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erratico CA; Szeitz A; Bandiera SM Biotransformation of 2,2’,4,4’-tetrabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-47) by human liver microsomes: identification of cytochrome P450 2B6 as the major enzyme involved. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2013, 26, 721–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uwimana E; Maiers A; Li X; Lehmler HJ Microsomal metabolism of prochiral polychlorinated biphenyls results in the enantioselective formation of chiral metabolites. Environ. Sci. Technol 2017, 51, 1820–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kania-Korwel I; Duffel MW; Lehmler HJ Gas chromatographic analysis with chiral cyclodextrin phases reveals the enantioselective formation of hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls by rat liver microsomes. Environ. Sci. Technol 2011, 45, 9590–9596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kania-Korwel I; Zhao H; Norstrom K; Li X; Hornbuckle KC; Lehmler HJ Simultaneous extraction and clean-up of polychlorinated biphenyls and their metabolites from small tissue samples using pressurized liquid extraction. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1214, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kania-Korwel I; Shaikh NS; Hornbuckle KC; Robertson LW; Lehmler HJ Enantioselective disposition of PCB 136 (2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-hexachlorobiphenyl) in C57BL/6 mice after oral and intraperitoneal administration. Chirality 2007, 19, 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kania-Korwel I; Hornbuckle KC; Peck A; Ludewig G; Robertson LW; Sulkowski WW; Espandiari P; Gairola CG; Lehmler HJ Congener-specific tissue distribution of Aroclor 1254 and a highly chlorinated environmental PCB mixture in rats. Environ. Sci. Technol 2005, 39, 3513–3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.European Commission, Commission decision EC 2002/657 of 12 August 2002 implementing Council Directive 96/23/EC concerning the performance of analytical methods and the interpretation of results, Off. J. Eur. Communities: Legis 2002, 221, 0008–0036. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bergman A; Klasson WE; Kuroki H; Nilsson A Synthesis and mass-spectrometry of some methoxylated PCBs. Chemosphere 1995, 30, 1921–1938. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jansson B; Sundström G Mass spectrometry 536 of the methyl ethers of isomeric hydroxychlorobiphenyls—potential metabolites of chlorobiphenyls. Biol. Mass Spectrom 1974, 1, 386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Joshi SN; Vyas SM; Duffel MW; Parkin S; Lehmler HJ Synthesis of sterically hindered polychlorinated biphenyl derivatives. Synthesis 2011, 7, 1045–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li X; Robertson LW; Lehmler HJ Electron ionization mass spectral fragmentation study of sulfation derivatives of polychlorinated biphenyls. Chem. Cent. J 2009, 3, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu X; Lehmler HJ Effects of thiol antioxidants on the atropselective oxidation of 2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-hexachlorobiphenyl (PCB 136) by rat liver microsomes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int 2016, 23, 2081–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asher BJ; D’Agostino LA; Way JD; Wong CS; Harynuk JJ Comparison of peak integration methods for the determination of enantiomeric fraction in environmental samples. Chemosphere 2009, 75, 1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Preston BD; Miller JA; Miller EC Non-arene oxide aromatic ring hydroxylation of 2,2’,5,5’-tetrachlorobiphenyl as the major metabolic pathway catalyzed by phenobarbital-induced rat liver microsomes. J. Biol. Chem 1983, 258, 8304–8311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schnellmann RG; Putnam CW; Sipes IG Metabolism of 2,2’,3,3’,6,6’-hexachlorobiphenyl and 2,2’,4,4’,5,5’-hexachlorobiphenyl by human hepatic microsomes. Biochem. Pharmacol 1983, 32, 3233–3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma C; Zhai G; Wu H; Kania-Korwel I; Lehmler HJ; Schnoor JL Identification of a novel hydroxylated metabolite of 2,2’,3,5’,6-pentachlorobiphenyl formed in whole poplar plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int 2016, 23, 2089–2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stamou M; Uwimana E; Flannery BM; Kania-Korwel I; Lehmler HJ; Lein PJ Subacute nicotine co-exposure has no effect on 2,2’,3,5’,6-pentachlorobiphenyl disposition but alters hepatic cytochrome P450 expression in the male rat. Toxicology 2015, 338, 59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Y; Hu K; Jia H; Jin G; Glatt H; Jiang H Potent mutagenicity of some non-planar tri- and tetrachlorinated biphenyls in mammalian cells, human CYP2E1 being a major activating enzyme. Arch. Toxicol 2017, 91, 2663–2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang C; Lai Y; Jin G; Glatt H; Wei Q; Liu Y Human CYP2E1-dependent mutagenicity of mono- and dichlorobiphenyls in Chinese hamster (V79)-derived cells. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 1908–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Püttmann M; Mannschreck A; Oesch F; Robertson L Chiral effects in the induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes using synthetic atropisomers of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Biochem. Pharmacol 1989, 38, 1345–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodman LE; Shedlofsky SI; Mannschreck A; Püttmann M; Swim AT; Robertson LW Differential potency of atropisomers of polychlorinated biphenyls on cytochrome P450 induction and uroporphyrin accumulation in the chick embryo hepatocyte culture. Biochem. Pharmacol 1991,41, 915–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wahlang B; Falkner KC; Clair HB; Al-Eryani L; Prough RA; States JC; Coslo DM; Omiecinski CJ; Cave MC Human receptor activation by Aroclor 1260, a polychlorinated biphenyl mixture. Toxicol. Sci 2014, 140, 283–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zanger UM; Schwab M Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther 2013, 138, 103–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guengerich FP, Human cytochrome P450 enzymes. In: Ortiz de Montellano PR (Ed.), Cytochrome P450, Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp 523–785. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.