Abstract

Sleep is an innate behavior conserved in all animals and, in vertebrates, is regulated by neuronal circuits in the brain. The conventional techniques of forward and reverse genetics have enabled researchers to investigate the molecular mechanisms that regulate sleep and arousal. However, functional interrogation of genes in specific cell subtypes in the brain remains a challenge. Here, we review the background of newly developed gene-editing technologies using engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system and describe the application to interrogate gene functions within genetically-defined brain cell populations in sleep research.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, sleep

Introduction

We spend about one third of life asleep. Sleep is a conserved behavior among all animals and its mechanism is one of the major unanswered questions in biology. Scientists have been attempting to unravel the neuronal and molecular mechanism of sleep for many decades. Optogenetic1 and chemogenetic2 tools have rapidly expanded our understanding of sleep at the neuronal circuit level. Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2), a light-gated cation channel originally discovered in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, is a key tool of optogenetics3,4,5. Neurons expressing ChR2 can be excited by blue light delivered through an fiber-optic implanted into the brain. Chemogenetics utilize genetically engineered receptors and biologically inert ligands to modulate the activity of neurons. Designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD) are modified muscarinic G-protein coupled receptors which are activated by Clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) and the most common chemogenetic tool used in neurosciences6. Controlling the activity of neuronal circuits by cell type-specific expression of optogenetic and/or chemogenetic tools enabled researchers to interrogate the causal relationship between sleep and the activity of specific neurons in hypothalamus7,8,9,10,11, brain stem12,13,14,15,16,17, ventral tegmental area18, basal forebrain19,20.

On the other hand, forward and reverse genetics approaches have expanded our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of sleep regulation in non-mammalian21,22,23,24,25,26 and mammalian organisms27,28. For example, hypocretin/orexin is a neuropeptide expressed in ~10,000 neurons in the lateral hypothalamus29,30,31. Hypocretin-deficient animals exhibit symptoms of narcolepsy, revealing an indispensable role of hypocretin/orexin in the maintenance of arousal32,33. However, the role of other gene transcripts within genetically defined neuronal populations remains a significant challenge. Here, we summarize the background of recently developed gene-editing technologies using engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system and describe the application of these technologies to investigate the gene functions in the specific cell population.

Engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system

CRISPR/Cas system forms an adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea to memorize the viral nucleic acids of previous infections and cleave invading nucleic acids during re-infection34,35. There are three types of CRISPR/Cas systems. The type II system is composed of trans-activating RNA (tracrRNA)36, CRISPR (Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)37 and cas (CRISPR-associated) genes38. CRISPR loci are made of “repeat-spacer” array and adjacent to small clusters of cas genes including Cas9 endonuclease. The CRISPR array is transcribed as a single pre-CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and processed into small pieces of matured crRNAs which has one spacer and one repeat39. While the spacer of matured crRNA is a fragment of the invading DNA integrated into the host genome during the previous infections34, the repeat is complementary to tracrRNA36. The duplex of crRNA and tracrRNA brings Cas9 endonuclease to the target sequence immediately adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) by complementary base pairing with the spacer and then Cas9 cleaves the target DNA40. The PAM sequence is a 2–6 base pair DNA sequence essential for Cas9 binding to the target loci and it varies depending on the bacterial species of the Cas9 gene41. For example, the most popular Cas9 derived from S. pyogenes requires 5’-NGG-3’ as PAM.

Recently, engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system has been utilized as a gene editing tool42. Engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system contains two components: Cas9 and single guide RNA (sgRNA), a chimeric RNA composed of crRNA (spacer and repeat) and tracrRNA40–43. Cas9, when combined with the sgRNA, can introduce double-strand breaks at target locations in the genome specified by the sgRNA. Researchers can specify the target sequence of Cas9 by simply changing a ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence in the sgRNA43,44,45. Double strand breaks, induced by Cas9, are repaired by either non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway or homology directed repair (HDR) pathway. Although the NHEJ is the most active repair mechanism, it is an error-prone pathway which can introduce small insertions or deletions (indels) at the target loci. These small indels result in amino acid deletions, insertions, or frameshift mutations leading to premature stop codons within the open reading frame of the target gene. Given the NHEJ pathway is active in both proliferating and non-proliferating cells, engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system can be applicable to disrupt genes in post-mitotic neurons in vivo46,47,48. Also, engineered CRISPR/cas9 system accelerates the production of knockout animals by co-injection of the Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA into the embryos49. Funato et al used engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system to show a missense mutation in the sodium leak channel NALCN reduced REM sleep. Also, Sunagawa et al injected Cas9 mRNA and triple sgRNAs targeting the same gene into the embryo to efficiently generate whole-body biallelic knockout mice in a single generation. By using this method, they screened all of the N-methyl- D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor family members and found Nr3a as a short-sleeper gene50. Same group also showed that the amount of REM sleep was dramatically reduced in the mice deficient in chrm1/chrm3 genes51. While NHEJ-mediated DSB can disrupt the gene expression by introducing premature termination codons, HDR can be used to incorporate exogenous DNA into endogenous loci. HDR is a process of homologous recombination relies on a DNA repair template with sufficient homology to the regions flanking the DSB site. Thus, HDR-mediated gene editing requires a DNA repair template, which has the desired sequence flanked by two homology arms, with the sgRNA and Cas952,45.

Cell type-specific gene editing to investigate the mechanism of sleep.

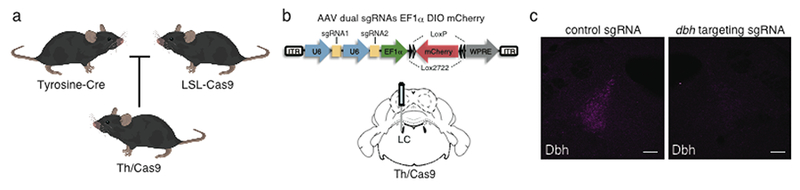

Transitions between wakefulness and sleep are regulated by the brain, which is composed of tremendously diverse cell types. Study of gene function during the last three decades has relied on the generation of systemic and conditional gene knockouts to disrupt gene expression. However, it has been challenging to knockout a gene in specific cell types in the brain. One of the most widely used methods is the Cre/loxP binary system, in which the Cre recombinase disrupt a gene through recombination of target sequences flanked by two loxP sites53. The expression of Cre recombinase driven by unique gene promoters allows researchers to generate cell type-specific gene knockouts. However, recombinase-dependent conditional gene knockouts require time consuming breeding of at least two mouse lines. Even though stereotaxic injections of recombinant Adeno Associated Virus (AAV) expressing a Cre recombinase can mediate spatiotemporal gene knockouts without time consuming breeding54, only a few cell type-specific promoters are compatible with the packaging capability of AAV. in vivo RNAi-based methods can reduce expression levels of multiple genes at a time, but they lack cellular specificity55. Alternatively, a research group led by Feng Zhang showed engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system can disrupt multiple genes in the adult mouse brain by AAV-mediated delivery of Cas9 and sgRNA48. The group also generated Cre-dependent Cas9 knockin mice56. Since hundreds of gene-specific promoter-driven Cre mouse lines are available, researchers can specifically express Cas9 in a wide variety of cell types in the brain by crossing Cre mouse lines with the Cas9 knockin mice and can target a gene by the stereotaxic injection of AAV encoding sgRNA (Fig.1a–b). By mating Agrp (agouti-related peptide)-IRES-cre mice and Cre-inducible Cas9 knockin mice, Xu et al showed that CRISPR/Cas9-mediated ablation of leptin receptor in the adult hypothalamic Agrp neurons caused severe obesity and diabetes57. Tso et al targeted astrocytes in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) using Aldh1L1-cre mice crossed with Cas9 knockin mice. The stereotaxic injection of AAV carrying sgRNA against bmal1 ablated the gene in SCN astrocytes and the mice showed significantly prolonged the circadian period of clock gene expression in the SCN and abnormal locomotor behavior58. Our group recently employed engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system to interrogate the role of norepinephrine (NE) secreted from the LC in the regulation of sleep-wake cycles (Yamaguchi et al Nature Communications in revision). Tyrosine Hydroxylase (Th)-Cre mice were crossed with Cas9 knockin mice to express Cas9 in the locus coeruleus NE neurons of their N1 offspring (Th/Cas9) (Fig 1a). We then packaged AAV carrying dual sgRNA targeting the gene of dopamine beta-hydroxylase (dbh), a key enzyme to produce norepinephrine from dopamine, and injected the virus into the LC of Th/Cas9 mice (Fig 1b). Mice showed reduced wakefulness during the dark phase even in the presence of salient stimuli, indicating that NE from the LC is involved in the maintenance of arousal. Taken together, cell type-specific Cas9 expression combined with AAV-mediated delivery of sgRNA enabled the interrogation of gene functions in the specific cell subtypes in the brain.

Figure 1.

Cre-dependent gene editing of dbh in the locus coelureus using engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system. (a) Design for expressing Cas9 in LC-NE (b) Schematic of the AAV vector encoding dual sgRNA targeting dbh and experimental design. (c) Representative immunofluorescence images of the LC from Th/Cas9 mice injected with AAV encoding control sgRNA (left) or sgRNA targeting dbh (right). Scale bar, 100 μm.

Despite the benefits of engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system to disrupt genes in the specific neuronal subtypes, there are some limitations (Table 1). First, since CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene disruption depends on the random small indels by error-prone NHEJ, the target neuronal population could become mosaic composed of cells have non frame-shift monoallelic and/or biallelic mutations. However, multiple sgRNA strategy might circumvent this problem. Sunagawa et al simulated the efficiency of gene disruption using multiple sgRNA targeting a same gene and exploited triple CRISPR strategy to knockout a gene50. We also adopted the dual sgRNA strategy to improve the efficiency of gene disruption in the LC NE neurons (Fig 1b) (Yamaguchi et al Nature Communications in press). We collected genomic DNA from the tissue punch of dual sgRNA-infused LC, and then sequenced dbh loci and revealed the percentages of frameshift mutations in all mutated dbh loci were 82.6% and 85.4%, respectively (Yamaguchi et al Nature Communications in press). We then found the 85% reduction in dbh immunoreactivity in sgRNA-infected LC cells (Fig 1c). Another limitation of using engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system is its off-target effects59,60,61,62. Since Cas9 tolerate mismatches of sgRNA and DNA complex, it is possible that Cas9 cleaves the open reading frame of other genes which has homology with the target sequence. Akcakaya et al actually showed that engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system with promiscuous sgRNAs induces substantial off-target mutations besides on-target mutations in vivo63. On the other hand, they also showed on-target indel mutations and no off-target mutations using sgRNAs which have relatively few closely matched sites. Therefore, it is essential to design sgRNAs with the lowest number of closely matched sites using in silico tools64,65.

Table 1,

Comparison of methods for cell-type specific gene disruption in the brain

| Method | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cre/loxp conditional KO | AAV-Cre/loxp conditional KO | RNAi | CRISPR/Cas9 | |

| Cell-type specificity |

High | High | Low | High |

| limitations | Time-consuming breeding Leaky expression of Cre in non-target cells |

Cell type-specific promoters are not always available | Off-target effects |

Off-target effects Mosaicism |

Future direction and conclusion

The CRISPR/Cas9 toolbox is rapidly expanding since the first application to gene editing. For example, epigenome-editing tools using a nuclease deficient Cas9 (dCas9) fused to the catalytic domain of DNA methytransferases66,67,68 or histone modification enzymes69,70 has been recently developed. It allows researchers to control epigenetic modifications in target loci. Sleep deprivation impairs cognitive functions such as learning and memory and its impact on the epigenome has been studied71. Thus, it will be interesting to investigate if modulations of epigenetic modification using dCas9-based tools in specific neuronal population mimics or dampen the detrimental effect of sleep deprivation on cognitive functions. Also, engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system enabled genetic modification in animals other than rodents. Therefore, researchers may investigate the gene functions in sleep regulation using animals (e.g marmosets) which have similar sleep patterns and characteristics to humans.

In summary, engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system may shed light on our understanding of gene functions within the genetically-defined brain cell types in sleep research. Also, we anticipate the future application of expanding CRISPR/Cas9 toolbox will open a new avenue of sleep research.

Highlights.

Sleep is regulated by the brain composed of tremendously diverse cell types.

Gene-editing technologies using engineered CRISPR/Cas9 system was recently developed

Engineered CRISPR technologies enabled the interrogation of gene functions within genetically-defined brain cell populations in sleep research.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of L.d.L. lab for discussions in the preparation of this manuscript. H.Y. was supported by Uehara memorial foundation research fellowship. L.d.L. is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AG047671, MH087592, MH102638.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests

References

- 1.Kim CK, Adhikari A & Deisseroth K Integration of optogenetics with complementary methodologies in systems neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 18, 222–235 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sternson SM & Roth BL Chemogenetic Tools to Interrogate Brain Functions. Annu. Rev. Neurosci 37, 387–407 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagel G et al. Channelrhodopsin-2, a directly light-gated cation-selective membrane channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 100, 13940–13945 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G & Deisseroth K Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat. Neurosci 8, 1263–1268 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X et al. Fast noninvasive activation and inhibition of neural and network activity by vertebrate rhodopsin and green algae channelrhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 102, 17816–17821 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S & Roth BL Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 104, 5163–5168 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamantidis AR, Zhang F, Aravanis AM, Deisseroth K & De Lecea L Neural substrates of awakening probed with optogenetic control of hypocretin neurons. Nature 450, 420–424 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung S et al. Identification of preoptic sleep neurons using retrograde labelling and gene profiling. Nature 545, 477–481 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen KS et al. A Hypothalamic Switch for REM and Non-REM Sleep. Neuron 97, 1168–1176.e4 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jego S et al. Optogenetic identification of a rapid eye movement sleep modulatory circuit in the hypothalamus. Nat. Neurosci 16, 1637–1643 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsunematsu T et al. Optogenetic Manipulation of Activity and Temporally Controlled Cell-Specific Ablation Reveal a Role for MCH Neurons in Sleep/Wake Regulation. J. Neurosci 34, 6896–6909 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter ME et al. Tuning arousal with optogenetic modulation of locus coeruleus neurons. Nat. Neurosci 13, 1526–1533 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter ME et al. Mechanism for Hypocretin-mediated sleep-to-wake transitions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, E2635–44 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi Y et al. Cells of a common developmental origin regulate REM/non-REM sleep and wakefulness in mice. Science (80-. ). 350, 957–961 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber F et al. Control of REM sleep by ventral medulla GABAergic neurons. Nature 526, 435–438 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anaclet C et al. The GABAergic parafacial zone is a medullary slow wave sleep-promoting center. Nat. Neurosci 17, 1217–1224 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Dort CJ et al. Optogenetic activation of cholinergic neurons in the PPT or LDT induces REM sleep. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 112, 584–589 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eban-Rothschild A, Rothschild G, Giardino WJ, Jones JR & de Lecea L VTA dopaminergic neurons regulate ethologically relevant sleep–wake behaviors. Nat. Neurosci 19, 1356–1366 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozen Irmak S & de Lecea L Basal Forebrain Cholinergic Modulation of Sleep Transitions. Sleep 37, 1941–1951 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu M et al. Basal forebrain circuit for sleep-wake control. Nat. Neurosci 18, 1641–1647 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen A et al. QRFP and Its Receptors Regulate Locomotor Activity and Sleep in Zebrafish. J. Neurosci 36, 1823–1840 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiu CN et al. A Zebrafish Genetic Screen Identifies Neuromedin U as a Regulator of Sleep/Wake States. Neuron 89, 842–856 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee DA et al. Genetic and neuronal regulation of sleep by neuropeptide VF. Elife 6, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appelbaum L et al. Sleep-wake regulation and hypocretin-melatonin interaction in zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 106, 21942–21947 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cirelli C et al. Reduced sleep in Drosophila Shaker mutants. Nature 434, 1087–1092 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donlea JM et al. Recurrent Circuitry for Balancing Sleep Need and Sleep. Neuron (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Funato H et al. Forward-genetics analysis of sleep in randomly mutagenized mice. Nature 539, 378–383 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tafti M Quantitative genetics of sleep in inbred mice. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci 9, 273–278 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Lecea L et al. The hypocretins: Hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 95, 322–327 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peyron C et al. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J. Neurosci 18, 9996–10015 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakurai T et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: A family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 92, 573–585 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chemelli RM et al. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: Molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell 98, 437–451 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin L et al. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell 98, 365–376 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrangou R et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science (80-. ). 315, 1709–1712 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marraffini LA & Sontheimer EJ CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science (80-. ). 322, 1843–1845 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deltcheva E et al. CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature 471, 602–607 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishino Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M & Nakata A Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J. Bacteriol 169, 5429–5433 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jansen R, Embden JDA van, Gaastra W & Schouls LM Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol. Microbiol 43, 1565–1575 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carte J, Wang R, Li H, Terns RM & Terns MP Cas6 is an endoribonuclease that generates guide RNAs for invader defense in prokaryotes. Genes Dev. 22, 3489–3496 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jinek M et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science (80-. ). 337, 816–821 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mojica FJM, Díez-Villaseñor C, García-Martínez J & Almendros C Short motif sequences determine the targets of the prokaryotic CRISPR defence system. Microbiology 155, 733–740 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doudna JA & Charpentier E The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu PD et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol 31, 827–832 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cong L et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–23 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mali P et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science (80-. ). 339, 823–826 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Straub C, Granger AJ, Saulnier JL & Sabatini BL CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knock-down in post-mitotic neurons. PLoS One 9, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Incontro S, Asensio CS, Edwards RH & Nicoll RA Efficient, Complete Deletion of Synaptic Proteins using CRISPR. Neuron 83, 1051–1057 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swiech L et al. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 102–106 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell 153, 910–918 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sunagawa GA et al. Mammalian Reverse Genetics without Crossing Reveals Nr3a as a Short-Sleeper Gene. Cell Rep. 14, 662–677 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niwa Y et al. Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors Chrm1 and Chrm3 Are Essential for REM Sleep. Cell Rep. 24, 2231–2247.e7 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang H et al. Resource One-Step Generation of Mice Carrying Reporter and Conditional Alleles by CRISPR / Cas-Mediated Genome Engineering. Cell 154, 1370–1379 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsien JZ et al. Subregion- and cell type-restricted gene knockout in mouse brain. Cell 87, 1317–1326 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaspar BK et al. Adeno-associated virus effectively mediates conditional gene modification in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 99, 2320–2325 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia H, Mao Q, Paulson HL & Davidson BL Sirna-mediated gene silencing in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol 20, 1006–1010 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Platt RJ et al. CRISPR-Cas9 knockin mice for genome editing and cancer modeling. Cell 159, 440–455 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu J et al. Genetic identification of leptin neural circuits in energy and glucose homeostases. Nature 556, 505–509 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tso CF et al. Astrocytes Regulate Daily Rhythms in the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus and Behavior. Curr. Biol 27, 1055–1061 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fu Y et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol 31, 822–826 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsai SQ et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 187–198 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X et al. Unbiased detection of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas9 and TALENs using integrase-defective lentiviral vectors. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 175–179 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Frock RL et al. Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 179–188 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akcakaya P et al. In vivo CRISPR editing with no detectable genome-wide off-target mutations. Nature 561, 416–421 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bae S, Park J & Kim JS Cas-OFFinder: A fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics 30, 1473–1475 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Labun K, Montague TG, Gagnon JA, Thyme SB & Valen E CHOPCHOP v2: a web tool for the next generation of CRISPR genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W272–W276 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mcdonald JI et al. Reprogrammable CRISPR/Cas9-based system for inducing site-specific DNA methylation. Biol. Open 5, 866–874 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vojta A et al. Repurposing the CRISPR-Cas9 system for targeted DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 5615–5628 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu XS et al. Editing DNA Methylation in the Mammalian Genome Resource Editing DNA Methylation in the Mammalian Genome. Cell 167, 233–235.e17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hilton IB et al. Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 510–517 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kearns NA et al. Functional annotation of native enhancers with a Cas9-histone demethylase fusion. Nat. Methods 12, 401–403 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gaine ME, Chatterjee S & Abel T Sleep Deprivation and the Epigenome. Front. Neural Circuits 12, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]