Abstract

Raptors are carnivorous birds including accipitrids (Accipitridae, Accipitriformes) and owls (Strigiformes), which are diurnal and nocturnal, respectively. To examine the evolutionary basis of adaptations to different light cycles and hunting behavior between accipitrids and owls, we de novo assembled besra (Accipiter virgatus, Accipitridae, Accipitriformes) and oriental scops owl (Otus sunia, Strigidae, Strigiformes) draft genomes. Comparative genomics demonstrated four PSGs (positively selected genes) (XRCC5, PRIMPOL, MDM2, and SIRT1) related to the response to ultraviolet (UV) radiation in accipitrids, and one PSG (ALCAM) associated with retina development in owls, which was consistent with their respective diurnal/nocturnal predatory lifestyles. We identified five accipitrid-specific and two owl-specific missense mutations and most of which were predicted to affect the protein function by PolyPhen-2. Genome comparison showed the diversification of raptor olfactory receptor repertoires, which may reflect an important role of olfaction in their predatory lifestyle. Comparison of TAS2R gene (i.e. linked to tasting bitterness) number in birds with different dietary lifestyles suggested that dietary toxins were a major selective force shaping the diversity of TAS2R repertoires. Fewer TAS2R genes in raptors reflected their carnivorous diet, since animal tissues are less likely to contain toxins than plant material. Our data and findings provide valuable genomic resources for studying the genetic mechanisms of raptors’ environmental adaptation, particularly olfaction, nocturnality and response to UV radiation.

Introduction

Recent phylogenetic analyses have classified raptors into three orders: Accipitriformes, Falconiformes, and Strigiformes1–3. Eagles and hawks are accipitrids belonging to the order Accipitriformes, which encompasses a large number of species ranging from small hawks to eagles4. Hovering and soaring at high altitude is one of the most important techniques employed by accipitrids that hunt in open habitats5. Accipitrids are diurnal, and while they are hunting at altitude they are exposed to intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation from sunlight. UV radiation is more intense at high altitude and could consequently cause damage to DNA. However, little is known of the molecular mechanisms that respond to UV radiation and repair damaged DNA in these diurnal accipitrids.

Although birds are primarily diurnal, one important exception is the nocturnal order Strigiformes (owls). The visual system in owls has undergone substantial evolutionary modification to adapt to nocturnality6. Owls have large and rod-dominant retinas that are extremely sensitive to light and highly useful in their low light hunting environments7. Whereas, diurnal raptors possess color perception and sharp visual acuity in relatively bright environments due to cone-dominant retinas7. Although previous studies in morphology, anatomy and behavior have proposed a relationship between nocturnality and functional diversification of low-light visual sensitivity6–8, the molecular basis underlying the low-light adaptation of owls is still unclear.

Hunting in many species relies on visual acuity but also on olfaction. Previous reviews have summarized the features of a fully functional avian olfactory system and that many species rely heavily on olfaction9–11. Diurnal and nocturnal raptors were previously thought to rely on eyesight for locating prey rather than using olfaction12. However, recent studies have reported that some raptors rely more on olfactory cues than visual acuity13,14. A previous approach to molecular characterization of the avian olfactory system using PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) amplification of olfactory receptor genes (ORs) with degenerate primers15 generated an approximate measurement of OR quantity. The quantity of ORs tended to be over-estimated through PCR with degenerate primers and only incomplete fragments were produced16. By comparison, de novo assembled genomes contributed to a global OR repertoire assessment17 and can therefore be employed to obtain a more accurate OR repertoire estimation.

Raptors also rely on other senses to successfully hunt and consume prey, and to avoid unpalatable and toxic food. For example, the detection of bitter tasting food is reported to protect animals from ingesting poisonous substances18,19. TAS2R genes have been reported as being involved in the animal’s ability to detect bitter and thus potentially poisonous food20–22, occurring more frequently in herbivores than in carnivores23. Herbivores have undergone a stronger selective pressure to retain TAS2R genes because plant tissues are more likely to contain toxins than animal tissues24. With an increasing number of raptor genomes, it is meaningful to compare TAS2R genes in birds with different dietary lifestyles to determine whether detection of bitterness is important to raptors. Thus, analyses of TAS2R variation in select bird species can provide valuable information on the use of taste in hunting raptors, in addition to visual and olfactory cues.

We consequently assembled draft whole-genome sequences of Accipiter virgatus (besra) and Otus sunia (oriental scops owl) to better understand the evolutionary adaptations related to the predatory lifestyle in diurnal accipitrids and nocturnal owls. We aimed to provide an insight into genomic changes affecting physiological functions (response to UV radiation and DNA damage repair) in diurnal accipitrids and retina development in owls. We annotated ORs in 13 bird species to demonstrate the diversification of raptors’ ORs repertoire. Furthermore, we aimed to compare the TAS2R gene number in bird species with varied diets. This work will provide novel insights into the evolutionary history and the genetic basis of adaptations to hunting of diurnal accipitrids and nocturnal owls, and a solid foundation for future raptor genetic and epigenomic studies.

Results

Genome sequencing, assembly and quality assessment

Muscle samples from one male A. virgatus and one female O. sunia were used for genomic sequencing. In total, we generated 168.87 Gb (~143-fold coverage) and 157.04 Gb (~120-fold coverage) of high quality sequences for A. virgatus and O. sunia, respectively, after filtering out low quality and duplicated reads (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). We estimated the genome size of A. virgatus and O. sunia to be 1.18 Gb and 1.30 Gb, respectively, on the basis of K-mer analysis (Supplementary Figs S1 and S2 and Table S3), which was similar to the reported avian genomes (Supplementary Table S4). The total length of all scaffolds was 1.18 Gb and 1.25 Gb, and the scaffold N50 length reached 5.38 Mb and 7.79 Mb for A. virgatus and O. sunia, respectively (Supplementary Table S5). For genome completeness, CEGMA results showed that 72.98% complete and 88.31% partial gene set for A. virgatus, and 83.87% complete and 92.34% partial gene set for O. sunia (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). BUSCO results showed that 81.2% and 90.8% of the eukaryotic single-copy genes were captured for A. virgatus and O. sunia, respectively. (Supplementary Tables S8 and S9).

Genome characterization

The GC content of the A. virgatus and O. sunia genomes were approximately 41.68% and 41.79%, similar to other bird species such as Gallus gallus (chicken) and Taeniopygia guttata (zebra finch). (Supplementary Fig. S3). We found that about 63.56 Mb and 77.17 Mb sequences (5.37% and 6.19% of the genome assembly) could be attributed to repeats in A. virgatus and O. sunia genomes, respectively. The percentage of long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), long terminal repeats (LTRs), short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), and DNA transposons were 2.97%, 1.74%, 0.13%, and 0.52% in A. virgatus genome, while 4.33%, 1.21%, 0.12%, and 0.51% in O. sunia genome (Supplementary Table S10). Comparison of these four repeat elements in nine raptors demonstrated the dominating role of LINEs in all kinds of repeat elements (Supplementary Figs S4 and S5).

Gene prediction resulted in a total of 16,388 and 15,229 protein-coding genes (PCGs) for A. virgatus and O. sunia genomes, respectively. The average gene and coding sequence lengths were 27,139/1,665 bp and 29,744/1,851 bp for A. virgatus and O. sunia genomes. Additionally, A. virgatus and O. sunia genes had an average of 10 exons and 11 exons per gene, respectively (Supplementary Tables S11 and S12). We found that 14,398 (87.86%) and 14,416 (94.66%) out of 16,388 and 15,299 identified PCGs were well supported by public protein databases (TrEMBL, SwissProt, Nr, InterPro, GO and KEGG) for A. virgatus and O. sunia, respectively. (Supplementary Figs S6 and S7 and Table S13). In addition, the non-PCGs were annotated: 55 5S rRNA, 200 tRNA, 165 microRNA (miRNA), and 153 snRNA genes for A. virgatus (Supplementary Table S14), and 53 5S rRNA, 281 tRNA, 212 microRNA (miRNA), and 207 snRNA genes for O. sunia (Supplementary Table S15).

Bird phylogeny, divergence and evolution of gene families

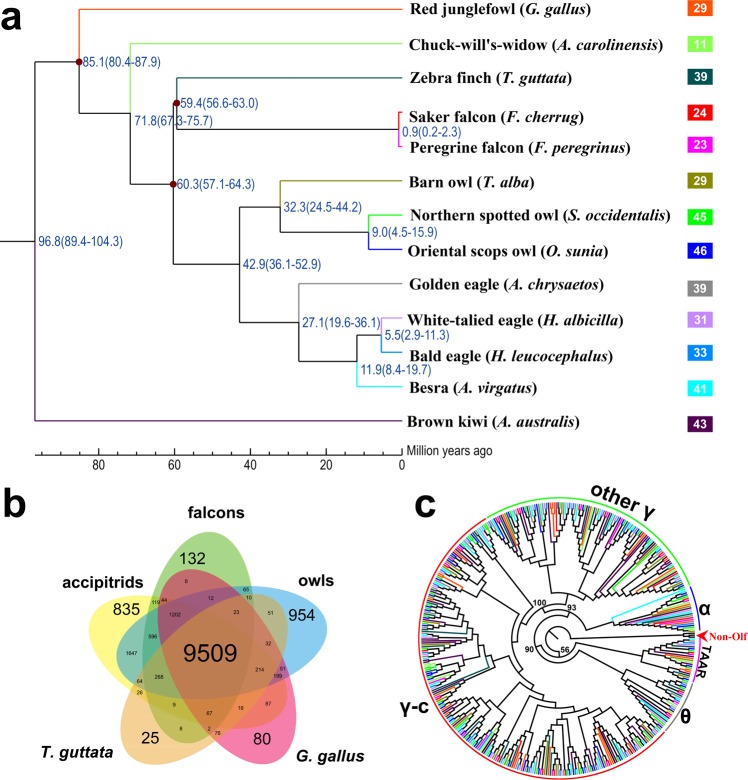

We identified 16,530 gene families for 13 bird species (four accipitrids: (besra (A. virgatus), bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), white-talied eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla), golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos)), three owls (Oriental scops owl (O. sunia), barn owl (Tyto alba), northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis)), two falcons (peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), saker falcon (Falco cherrug)), zebra finch (T. guttata), red junglefowl (G. gallus), chuck-will’s-widow (Antrostomus carolinensis), and brown kiwi (Apteryx australis)) (Supplementary Fig. S8 and Table S16), of which 2,845 represented 1:1 orthologous gene families. Comparison of orthologous gene clusters among accipitrids, falcons, owls, T. guttata, and G. gallus is showed in Fig. 1b. The maximum likelihood phylogeny constructed based on the 1:1 orthologous genes indicated that owls and accipitrids belong to a subclade that was most likely derived from a common ancestor approximately 42.9 million years ago (Mya) (Fig. 1a). The falcons and other predators diverged 60.3 Mya, and Falco peregrinus and F. cherrug diverged 0.9 Mya.

Figure 1.

Comparative genomics in avian species studied. (a) Phylogenetic tree constructed using 1:1:1 orthologous genes. Branch numbers indicate the number of gene families that have expanded (left) and contracted (right) after the split from the common ancestor. The time lines indicate divergence times among the species. (b) Comparison of orthologous gene clusters among accipitrids, falcons, owls, T. guttata, and G. gallus. (c) Maximum likelihood (ML) tree constructed using intact ORs from 13 birds. Three genes (ADRB1, ADRA1A, and HTR6) from family GPCRs were used as outgroup (shown as Non-Olf). ORs of each bird are represented by the same color as the species branch in (a). The insets showing the number of intact ORs in each species that are analyzed using ML tree topology were presented behind each species in (a).

Positive selection in the accipitrid lineage

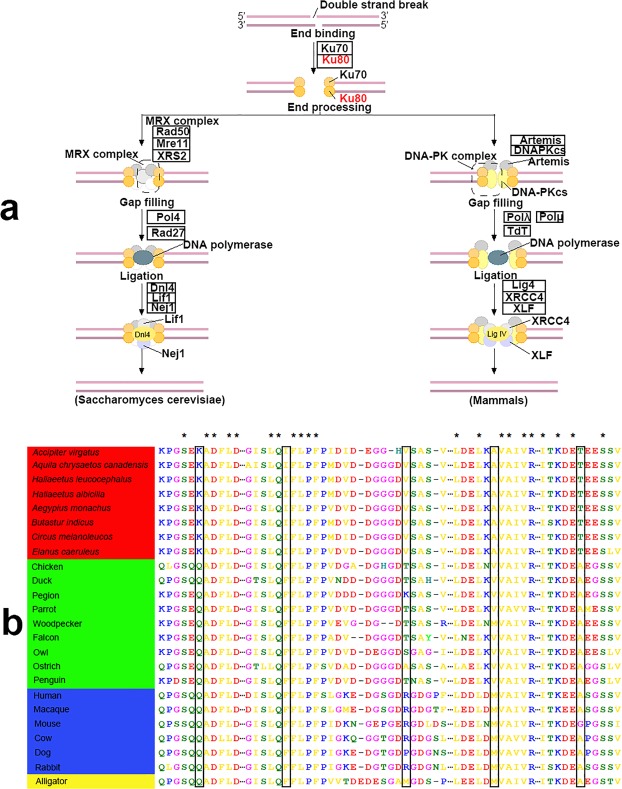

On the accipitrid branch, we found that 4 genes (i.e. XRCC5, SIRT1, PRIMPOL, MDM2) had functional associations with responses to UV radiation and DNA damage repair (Supplementary Table S17). A top gene in our selection scan was XRCC5, which was also called ku80. XRCC5 is important for the repair of DNA ends by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) (Fig. 2a). Deletion of XRCC5 in mice has resulted in immune deficiency, growth retardation, increased chromosomal instability, and cancer25,26. Altered expression of XRCC5 has caused oncogenic phenotypes, such as genomic instability, hyper proliferation and resistance to apoptosis, and tumorigenesis27, and has been detected in various types of sporadic cancer28. We found five missense mutations in XRCC5 in accipitrids (Fig. 2b), of which three missense mutations were predicted to be deleterious by PolyPhen-229 (Table 1). Further validation showed that all accipitrids had the same amino acid type as A. virgatus, H. leucocephalus, H. albicilla and A. chrysaetos at all mutation sites (Fig. 2b). Therefore, it was very clear that the mutations at XRCC5 were accipitrid-specific.

Figure 2.

Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway (KEGG map03450) and multiple amino-acid alignment of XRCC5. (a) Positively selected gene XRCC5 (ku80) was shown in red in the NHEJ pathway. (b) The missense mutations found in this study were marked within rectangle. The asterisk means all species have the same amino acid type at this position. Species in the red box are accipitrids; species in the green box are other birds; species in the blue box are mammals; species in the yellow box is a reptile.

Table 1.

Species-specific missense mutations of positively selected genes.

| Species | Genes | Mutation sites (human) | Amino acids (raptors/human) | Polarity | PolyPhen-2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HumanDiv | HumanVar | |||||||

| Accipitrids | XRCC5 | 104 | K(Lys)/Q(Gln) | polar/polar | 0.27 | benign | 0.055 | benign |

| 163 | I(Ile)/F(Phe) | unpolar/unpolar | 0.89 | possibly damaging | 0.557 | possibly damaging | ||

| 178 | V(Val)/R(Arg) | unpolar/polar | 0.047 | benign | 0.083 | benign | ||

| 389 | A(Ala)/M(Met) | unpolar/unpolar | 0.937 | possibly damaging | 0.967 | probably damaging | ||

| 691 | T(Thr)/A(Ala) | polar/unpolar | 0.919 | possibly damaging | 0.312 | benign | ||

| Owls | ALCAM | 259 | I(Ile)/A(Ala) | unpolar/unpolar | 0.617 | possibly damaging | 0.336 | benign |

| 297 | M(Met)/T(Thr) | unpolar/polar | 0.85 | possibly damaging | 0.557 | possibly damaging | ||

In response to ionizing radiation, SIRT1 was reported to play a vital part in DNA repair30,31. SIRT1 null MEF cells were observed to be more sensitive than control MEF cells in response to UV irradiation, indicating that SIRT1 was possibly involved in UV-induced DNA repair32. Murine double minute 2 (MDM2) was an important component of the response to UV radiation, and cells with decreased levels of MDM2 showed more sensitivity to ionizing radiation33. PRIMPOL played a critical role in damage tolerance to UV irradiation during DNA replication34,35. Decreased levels of PRIMPOL sensitized mammalian and avian cells to UV irradiation36–38, suggesting that PRIMPOL was vital for recovery from UV damage.

Positive selection on the owl branch

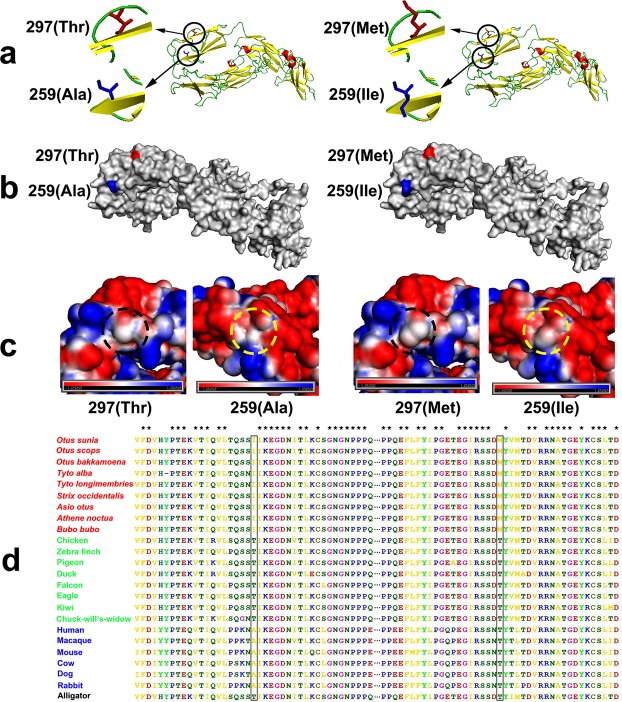

We found one PSG, ALCAM, had direct correlation with retina development in owls (Supplementary Table S17). It has been documented that ALCAM can guide retinal axons in Drosophila and rodents39,40, and ALCAM has a potential role in human retinal angiogenesis41. Angiogenesis is a crucial mechanism in ischemic retinal vasculopathy pathogenesis42, and previous studies have demonstrated that ALCAM might participate in both processes41. The determination of ALCAM’s involvement in these processes is important as ischemic retinal vasculopathies and posterior uveitis have led to vision loss in people in the United States and worldwide43,44. Two owl-specific missense mutations were identified in ALCAM (Fig. 3d), and both missense mutations were predicted to affect the protein function by PolyPhen-2 (Table 1). Further validation, including PCR confirmed that all the owls had the same amino acid type as O. sunia, T. alba and S. occidentalis at both mutation sites, which demonstrated that both mutations at ALCAM were owl-specific. Both missense mutations had a deleterious influence on protein structure (Fig. 3a–c).

Figure 3.

Amino-acid sequence alignment of ALACM and three kinds of visualization of non-mutated and mutated ALACM. (a) Altered amino acids at p259 and p297 are shown in non-mutant and mutant ALCAM protein models. (b) In the surface of non-mutant and mutant ALCAM, mutation sites of p259 and p297 are colored as blue and red, respectively. (c) Electrostatic potential maps on the surface of p259 and p297 residues. Compared with non-mutant ALCAM, the p259 mutation in mutant ALCAM shows a trend of negatively charged region, while p297 mutation tends to be neutral (blue: positive charges; red: negative charges). (d) Two missense mutations in ALCAM were marked within rectangle. The asterisk means all species have the same amino acid type at this position. Species in red are owls; species in green are other birds; species in blue are mammals; species in black is a reptile.

Olfactory Receptor Genes (ORs)

We annotated the ORs in 13 bird species based on putative functionality and seven transmembrane helices (7TM) (Supplementary Table S18). Generally, the number of ORs in raptors varied between orders: owls had the most, accipitrids medium, and falcons least. Overall, the average number of ORs in raptors was not less than in other bird species. Comparative analyses of the OR repertoire showed that most ORs in avian genomes were the γ subgroup of type 1 OR genes, in accordance with previously sequenced avian genomes15. Phylogenetic comparison of OR repertoires suggested that γ ORs in birds did not show an obvious species-specific clustering pattern, which was different from previous studies45. The gene family size of ORs in this study was very likely to have directly caused this contrast. Finally, a few γ ORs of the kiwi were basal to many clades containing γ ORs (Fig. 1c).

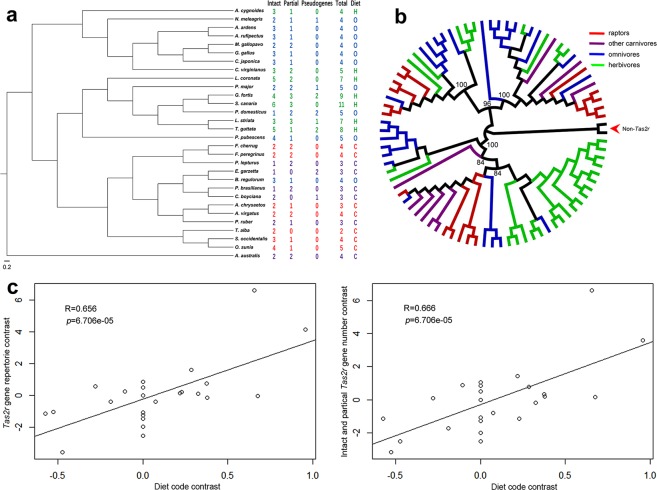

Dietary Lifestyle

The total number of TAS2R genes of accipitrids, falcons, and owls varied little (Fig. 4a). There were no pseudogenes in the TAS2R repertoires in all raptors we studied, and the percentage of pseudogenes in birds was much lower than other vertebrates reported23. Compared to carnivorous birds, omnivorous birds tended to possess more TAS2R genes, while herbivorous birds possessed the most. It was reported that some TAS2R lineages were enriched because of species-specific gene duplications, and other lineages were relatively duplication free46. This phenomenon was also obvious in the phylogenetic tree we constructed (Fig. 4b). The lineages, which were marked with one color, demonstrated a cluster of genes belonging to the same species or group of closely related species. The lineages marked with many colors illustrated genes from distantly related species. There was positive correlation between the phylogenetically independent contrasts (PICs) in the dietary code and the PICs in the TAS2R gene repertoire size (R = 0.656, P = 6.706e-05) (Fig. 4c). Equally, the positive correlation was verified while discarding pseudogenes (R = 0.666, P = 4.859e-05) (Fig. 4c), and the difference between both correlations was not significant.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analyses of TAS2Rs and the impacts of diet to TAS2R repertoire size. (a) The TAS2R gene repertoires of 30 birds identified in this study. The sources of dietary information were shown in Supplementary Table S22. C, carnivorous; H, herbivorous; O, omnivorous. (b) Evolutionary relationships of all 81 intact TAS2R genes from 30 birds. (c) PIC in a total number of TAS2Rs (intact genes, partial genes, and pseudogenes) was positively correlated with PIC in diet codes significantly. PIC in a total number of TAS2Rs (intact genes and partial genes) was positively correlated with PIC in diet codes significantly. The diet code is 0, 0.5, and 1 for the carnivorous birds, the omnivorous birds, and the herbivorous birds, respectively.

Discussion

The evolution of genes associated with the response to UV radiation and DNA damage repair may have helped diurnal raptors cope with flying or soaring at high altitudes. This type of adaptation has also been developed by other animals living at high altitude47. We identified four genes that are under positive selection in the accipitrid lineage, which were XRCC5, MDM2, PRIMPOL, and SIRT1, and conformed to this adaptation strategy. XRCC5 had five accipitrids-specific mutations that possibly affected the protein function. This finding may be related to the increased exposure of accipitrids to UV radiation compared to non-high-altitude birds. It is possible that potentially important reorganization of the radiation resistance system has taken place in the diurnal raptors since their divergence from other bird species, which may be related to the diurnal raptor lifestyle or ecology.

There was a substantial evolutionary modification in the owl visual system6 due to nocturnal adaptation. Owls possess large and rod-dominant retinas that are extremely sensitive to light, providing them with extraordinary night vision6. We found a PSG (ALCAM) associated with retina development, which also had two owls-specific mutations that possibly affected the protein function. This PSG possibly enhances low-light sensitivity, and thus resulted in high visual acuity at night. This gene and gene family expansions related to photoreceptor differentiation or development and retina development possibly worked together to enhance owl nocturnality.

It has long been hypothesized that raptors rely on eyesight for locating prey12. We found that the number of ORs in raptors was not less than other studied bird species, suggesting that raptors possibly have similar levels of olfactory sense. Our finding of the dual use of olfaction and vision in raptors is consistent with previous studies13,14.

It has been reported that each TAS2R gene can discern different bitter compounds and different TAS2R genes have contrasting sensitivities to the same bitter compounds48. Previous studies assumed that TAS2R gains through gene duplication could raise the number of detectable toxins, while the losses of TAS2Rs would decrease this number23. Thus, the herbivores were likely to have more functional TAS2R genes than the carnivores. In this study, the carnivorous birds possessed the least TAS2R genes, while the herbivorous birds the most. Despite our findings being congruent with previous studies, the limited number of avian species and the qualitative dietary codes for species analyzed restricted the statistical power of our analyses, and therefore more species and quantitative dietary information should be employed in the future. Since TAS2R genes are capable of detecting different bitter compounds48, a variety of TAS2R genes should be included in future studies.

In summary, this is the first report describing the complete Otus genome and Accipiter genome. Comparative genomics confirmed the PSGs associated with the response to UV radiation and DNA damage repair were present in diurnal raptors while not in nocturnal raptors and other bird species. Furthermore, the diversification of OR repertoires highlighted the importance of olfaction in the predatory lifestyle of raptors. We also confirmed that the genomic changes present in the owl genomes enhanced nocturnal vision. Analyses of TAS2R gene number in birds with different dietary lifestyles indicated that the TAS2R repertoire diversity was chiefly determined by feeding habits. Our de novo assembled genomes presented here will provide a resource for the future examination of evolution and adaptation of raptors to their environment and diet, and the genomes will eventually be the useful reference in aiding the long-term conservation of raptors and their genetic diversity, such as the investigation of the evolutionary adaptation and polymorphic microsatellite loci development.

Methods

Sampling and sequencing

Muscle samples of a wild male A. virgatus and a wild female O. sunia that both died of natural causes, were collected from Laojunshan National Nature Reserve (Yibin, Sichuan Province, China). Collected muscle samples were used for genomic DNA extraction, isolation and sequencing. We used a whole genome shotgun approach on the Illumina HiSeq. 2000 platform to sequence the genome. We constructed two paired-end libraries with insert sizes of 230 base pairs (bp) and 500 bp, and three mate-paired libraries with insert sizes of 2 kb, 5 kb and 10 kb.

Genome size estimation, genome assembly and completeness assessment

Before assembly, a 17-Kmer analysis was performed for estimating the genome size of A. virgatus and O. sunia genomes with 230 bp libraries, respectively. The assemblies were first performed by SOAPdenovo249 with the parameters set as “all -d 2 –M 2 –k 35”. After using SSPACE50 to build super-scaffolds, Intra-scaffold gaps were then filled using Gapcloser with reads from short-insert libraries. CEGMA51 and BUSCO52 were used to evaluate the genome completeness.

Gene prediction and annotation

We combined the de novo and homology-based prediction to identify PCGs in A. virgatus and O. sunia. The de novo prediction was performed on the assembled genomes with repetitive sequences masked as “N” based on the HMM (hidden Markovmodel) algorithm. AUGUSTUS53 and GENSCAN54 programs were executed to find coding genes, using appropriate parameters. For the homology prediction, proteins of G. gallus, F. cherrug, F. peregrinus, and humans were mapped onto both genomes using TblastN55 with an E-value cutoff of 1E-5. To obtain the best matches of each alignment, the results yielded from TblastN were processed by SOLAR56. Homologous sequences were successively aligned against the matching gene models using GeneWise57. We used EVidenceModeler (EVM)58 to integrate the above data and obtained a consensus gene set. We used Repeatmasker59 to identify the repetitive sequences in the genomes of A. virgatus and O. sunia. tRNA genes were identified by tRNAscan-SE60. A. virgatus and O. sunia genomes were aligned against the rRNAs database to identify rRNA with blastN. We used INFERNAL61 by searching against the Rfam database with default parameters to identify the other ncRNAs, including miRNA and snRNA.

Functional annotation

Functional annotation of the A. virgatus and O. sunia genes was undertaken based on the best match derived from the alignments to proteins annotated in SwissProt and TrEMBL databases62. Functional annotation used BLASTP tools with the same E-value cut-off of 1E-5. Descriptions of gene products from Gene Ontology (GO) ID were retrieved based on the results of SwissProt. We also annotated proteins against the NCBI non-redundant (Nr) protein database. The motifs and domains of genes were annotated using InterProScan63 against publicly available databases, including ProDom64, PRINTS65, PIRSF66, Pfam67, ProSiteProfiles68, PANTHER69, SUPERFAMILY70, and SMART71. To find the best match and involved pathway for each gene, all genes were uploaded to KAAS72, a web server for functional annotation of genes against the manually corrected KEGG genes database by BLAST, using the bi-directional best hit (BBH) method.

Analyses of gene family, phylogeny, and divergence

We used orthoMCL73 to define orthologous genes from 13 avian genomes (Supplementary Table S19). Phylogenetic analyses of these 13 birds were constructed using 1:1 orthologous genes. Coding sequences from each 1:1 orthologous family were aligned by PRANK74 and concatenated to one sequence for each species for building the tree. Modeltest (ver. 3.7) was used to select the best substitution model75. RAxML76 was then applied to reconstruct ML phylogenetic trees with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Divergence time estimation was performed by PAML MCMCTREE77.

Positive selection analyses

The above alignments of 1:1 orthologous genes and phylogenetic tree were used to estimate the ratio of the rates of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions (ω) per gene by ML with the codeml program within PAML77 under the branch-site model. We then performed a likelihood ratio test and identified the PSGs of the accipitrid and owl branches, respectively.

Validation of the species-specific missense mutations with protein sequences obtained from Genbank

In order to validate the species-specific missense mutations in genes mentioned above, we downloaded all available protein sequences of birds, 6 mammals (human, macaque, mouse, cow, dog, and rabbit), and one reptile (alligator) of each gene from Genbank. All these protein sequences, together with protein sequences identified in genomes assembled in this study, were aligned using MEGA778 for each gene to validate the species-specific missense mutations.

Transcriptome assembly and gene identification for validating the species-specific missense mutations

To verify the species-specific missense mutations, we downloaded the transcriptome sequencing data of accipitrids (Aegypius monachus: SRR3203236, Butastur indicus: SRR3203233, Circus melanoleucos: SRR3203217, and Elanus caeruleus: SRR3203227), and owls (Otus scops: SRR3203230, Otus bakkamoena: SRR3203243, Tyto longimembris: SRR3203222, Asio otus: SRR3203220, Athene noctua: SRR3203242, and Bubo bubo: SRR3203225) from Genbank. The RNA-seq reads were de novo assembled into contigs using Trinity79 (Grabherr et al. 2011). Based on the Trinity results, we identified genes (XRCC5 and ALCAM) using TBLASTN.

PCR amplification and sequencing for validating the species-specific mutations

Due to the sample availability, we only conducted PCR validation for the owl-specific mutations. Twenty muscle samples of owls (Supplementary Table S20) were collected from the Museum of Sichuan University to verify the owl-specific missense mutation sites in gene ALCAM. Primers (Supplementary Table S21) were designed by comparing gene sequences of G. gallus, T. guttata, A. virgatus, F. peregrinus, and O. sunia with Primer Premier 580. The amplification of genes was carried out with TaKaRa RTaq (TaKaRa Biomedical, Japan) and implemented on a PTC-100 thermal cycler (BioRad, Hercules, CA) in the reaction mixture. The PCR products were sequenced on an ABI PRISM 3730 DNA sequencer in Tsingke Biotechnology Company (Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China) after electrophoresing in 2% agarose gel.

Protein structure determination

The crystal structure of ALCAM was obtained from SWISS-MODEL81. We converted the PDB files to PQR format with PDB2PQR server82. The PDB files were used for visualization of cartoon and surface representations of gene mutants. The visualization of the electrostatic surface potential was conducted using the APBS plugin in PyMOL83.

Analyses of olfactory receptor genes (ORs)

We constructed an OR database based on reference OR protein sequences downloaded from uniprot84. Thirteen studied avian genomes were aligned to the ORs database constructed above with TBLASTN. According to the results, we confirmed the intact olfactory receptor genes by a series of steps85. The OR gene repertoire estimated above and three non-ORs downloaded from Genbank were used for comparative phylogenetic analyses. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method implemented in MEGA7. The reliability of the phylogenetic trees was evaluated with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Analyses of TAS2R genes

TAS2R database was constructed based on reference TAS2R protein sequences downloaded from uniprot84. The genomes of 10 omnivorous birds, 7 herbivorous birds, 7 studied raptors, and another 6 carnivorous birds were aligned to the TAS2R database constructed above with TBLASTN (Supplementary Table S22). We followed a previous study23 in identifying TAS2R genes. A neighbor-joining tree of 81 protein sequences of intact TAS2Rs was constructed using MEGA7 with Poisson-corrected gamma distances. The reliability of the estimated tree was evaluated by the bootstrap method with 1,000 bootstrap replications. The package Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution86 was used to perform the PIC analyses87, and the tree used in this analysis was built with 12 mitochondrial PCGs via RAxML with 1,000 bootstraps.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Key Program of Research and Development, Ministry of Science and Technology (2016YFC0503200); and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31702017).

Author Contributions

Chuang Zhou and Bisong Yue designed and supervised the project. Chuang Zhou, Jiazheng Jin and Changjun Peng performed the bioinformatics analyses. Chuang Zhou, Guannan Wang, and Xue Jiang conducted the PCR validation. Chuang Zhou wrote the manuscript. Megan Price, Zhaobin Song, Jing Li, Xiuyue Zhang, Zhenxin Fan and Bisong Yue revised the manuscript. Qinchao Wen, Weideng Wei, Kai Cui and Yang Meng participated in discussions and provided valuable advice. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Genome and DNA sequencing data of besra and oriental scops owl have been deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject ID PRJNA420185. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its Supplementary Material or are available from the authors upon request. More detailed information for the approaches has been revealed in the Supplementary Material.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chuang Zhou and Jiazheng Jin contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Zhenxin Fan, Email: zxfan@scu.edu.cn.

Bisong Yue, Email: bsyue@scu.edu.cn.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-38680-x.

References

- 1.Ericson PG. Evolution of terrestrial birds in three continents: biogeography and parallel radiations. Journal of Biogeography. 2012;39:813–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02650.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuri T, et al. Parsimony and model-based analyses of indels in avian nuclear genes reveal congruent and incongruent phylogenetic signals. Biology. 2013;2:419–444. doi: 10.3390/biology2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarvis ED, et al. Whole-genome analyses resolve early branches in the tree of life of modern birds. Science. 2014;346:1320–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.1253451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerner HR, Mindell DP. Phylogeny of eagles, Old World vultures, and other Accipitridae based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution. 2005;37:327–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, Y. D. An Introduction to the Raptors of Southeast Asia. Nature Society (Singapore), Bird Group and Southeast Asian Biodiversity Society, 11–15 (2011).

- 6.Wu Y, et al. Retinal transcriptome sequencing sheds light on the adaptation to nocturnal and diurnal lifestyles in raptors. Scientific reports. 2016;6:33578. doi: 10.1038/srep33578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones MP, Pierce KE, Ward D. Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 2007;16:69–87. doi: 10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanna ZR, et al. Northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) genome: divergence with the barred owl (Strix varia) and characterization of light-associated genes. Genome biology and evolution. 2017;9:2522–2545. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evx158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagelin, J. Odors and chemical signaling. Reproductive behavior and phylogeny of birds: Sexual selection, behavior, conservation, embryology and genetics, 75–119 (2007).

- 10.Caro SP, Balthazart J. Pheromones in birds: myth or reality? Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 2010;196:751–766. doi: 10.1007/s00359-010-0534-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castro I, et al. Olfaction in birds: a closer look at the kiwi (Apterygidae) Journal of Avian Biology. 2010;41:213–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-048X.2010.05010.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Rourke CT, Hall MI, Pitlik T, Fernández-Juricic E. Hawk eyes I: diurnal raptors differ in visual fields and degree of eye movement. PloS one. 2010;5:e12802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lisney TJ, et al. Comparison of eye morphology and retinal topography in two species of new world vultures (Aves: Cathartidae) The Anatomical Record. 2013;296:1954–1970. doi: 10.1002/ar.22815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang S-Y, Walther BA, Weng G-J. Stop and smell the pollen: the role of olfaction and vision of the oriental honey buzzard in identifying food. PloS one. 2015;10:e0130191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiger SS, Fidler AE, Kempenaers B. Evidence for increased olfactory receptor gene repertoire size in two nocturnal bird species with well-developed olfactory ability. BMC evolutionary biology. 2009;9:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preston GM. Cloning gene family members using PCR with degenerate oligonucleotide primers. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2003;226:485. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-384-4:485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu S, et al. De novo transcriptome analysis of wing development-related signaling pathways in Locusta migratoria manilensis and Ostrinia furnacalis (Guenee) PloS one. 2014;9:e106770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia J, Hankins W. The Evolution of Bitter and the Acquisition of Toxiphobia. Olfaction & Taste Symposium. 1975;30:39–45. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-209750-8.50014-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glendinning JI. Is the bitter rejection response always adaptive? Physiology & behavior. 1994;56:1217–1227. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer A, Gilad Y, Man O, Pääbo S. Evolution of bitter taste receptors in humans and apes. Molecular biology and evolution. 2004;22:432-–436. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Go Y, Satta Y, Takenaka O, Takahata N. Lineage-specific loss of function of bitter taste receptor genes in humans and nonhuman primates. Genetics. 2005;170:313–326. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.037523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugawara T, et al. Diversification of bitter taste receptor gene family in western chimpanzees. Molecular biology and evolution. 2010;28:921–931. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li D, Zhang J. Diet shapes the evolution of the vertebrate bitter taste receptor gene repertoire. Molecular biology and evolution. 2013;31:303–309. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Thomas SD, Zhang J. Relaxation of selective constraint and loss of function in the evolution of human bitter taste receptor genes. Human Molecular Genetics. 2004;13:2671–2678. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taccioli GE, et al. Ku80: product of the XRCC5 gene and its role in DNA repair and V (D) J recombination. Science. 1994;265:1442–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.8073286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu Y, et al. Growth retardation and leaky SCID phenotype of Ku70-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;7:653–665. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stark JM, Pierce AJ, Oh J, Pastink A, Jasin M. Genetic steps of mammalian homologous repair with distinct mutagenic consequences. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:9305–9316. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.21.9305-9316.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alshareeda AT, et al. Clinicopathological significance of KU70/KU80, a key DNA damage repair protein in breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2013;139:301–310. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adzhubei IA, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nature methods. 2010;7:248. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeong J, et al. SIRT1 promotes DNA repair activity and deacetylation of Ku70. Experimental & molecular medicine. 2007;39:8. doi: 10.1038/emm.2007.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oberdoerffer P, et al. SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell. 2008;135:907–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang R-H, et al. Impaired DNA damage response, genome instability, and tumorigenesis in SIRT1 mutant mice. Cancer cell. 2008;14:312–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perry ME. Mdm2 in the response to radiation. Molecular Cancer Research. 2004;2:9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bianchi, J. Investigating the role of a novel primase-polymerase, PrimPol, in DNA damage tolerance in vertebrate cells, University of Sussex (2013).

- 35.Bianchi J, et al. PrimPol bypasses UV photoproducts during eukaryotic chromosomal DNA replication. Molecular cell. 2013;52:566–573. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey LJ, Bianchi J, Hégarat N, Hochegger H, Doherty AJ. PrimPol-deficient cells exhibit a pronounced G2 checkpoint response following UV damage. Cell Cycle. 2016;15:908–918. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1128597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guilliam TA, Bailey LJ, Brissett NC, Doherty AJ. PolDIP2 interacts with human PrimPol and enhances its DNA polymerase activities. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44:3317–3329. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pilzecker B, et al. PrimPol prevents APOBEC/AID family mediated DNA mutagenesis. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44:4734–4744. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramos R, et al. The irregular chiasm C-roughest locus of Drosophila, which affects axonal projections and programmed cell death, encodes a novel immunoglobulin-like protein. Genes & Development. 1993;7:2533–2547. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiner JA, et al. Axon fasciculation defects and retinal dysplasias in mice lacking the immunoglobulin superfamily adhesion molecule BEN/ALCAM/SC1. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2004;27:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith JR, Chipps TJ, Ilias H, Pan Y, Appukuttan B. Expression and regulation of activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule in human retinal vascular endothelial cells. Experimental eye research. 2012;104:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sapieha P, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity: understanding ischemic retinal vasculopathies at an extreme of life. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:3022–3032. doi: 10.1172/JCI42142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suttorp-Schulten M, Rothova A. The possible impact of uveitis in blindness: a literature survey. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1996;80:844. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.9.844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Congdon NG, Friedman DS, Lietman T. Important causes of visual impairment in the world today. Jama. 2003;290:2057–2060. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Duc D, et al. Kiwi genome provides insights into evolution of a nocturnal lifestyle. Genome biology. 2015;16:147. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0711-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi P, Zhang J, Yang H, Zhang Y-P. Adaptive diversification of bitter taste receptor genes in mammalian evolution. Molecular biology and evolution. 2003;20:805–814. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu L, et al. Genomic analysis of snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus) identifies genes and processes related to high-altitude adaptation. Nature genetics. 2016;48:947. doi: 10.1038/ng.3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyerhof W, et al. The molecular receptive ranges of human TAS2R bitter taste receptors. Chemical senses. 2010;35:157–170. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjp092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo R, et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience. 2012;1:18. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics. 2010;27:578–579. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stanke M, et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic acids research. 2006;34:W435–W439. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burge C, Karlin S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA1. Journal of molecular biology. 1997;268:78–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic acids research. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ashburner M, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature genetics. 2000;25:25. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. GeneWise and genomewise. Genome research. 2004;14:988–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.1865504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haas BJ, et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome biology. 2008;9:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smit, A. F., Hubley, R. & Green, P. 2010 RepeatMasker Open-3.0, http://www.repeatmasker.org (1996).

- 60.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic acids research. 1997;25:955. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nawrocki EP, Kolbe DL, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1335–1337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boeckmann B, et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic acids research. 2003;31:365–370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hunter S, et al. InterPro: the integrative protein signature database. Nucleic acids research. 2008;37:D211–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bru C, et al. The ProDom database of protein domain families: more emphasis on 3D. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:D212–D215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Attwood TK, et al. PRINTS-S: the database formerly known as PRINTS. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:225–227. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu CH, et al. PIRSF: family classification system at the Protein Information Resource. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:D112–D114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Finn RD, et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic acids research. 2013;42:D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sigrist CJ, et al. PROSITE: a documented database using patterns and profiles as motif descriptors. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2002;3:265–274. doi: 10.1093/bib/3.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomas PD, et al. PANTHER: a browsable database of gene products organized by biological function, using curated protein family and subfamily classification. Nucleic acids research. 2003;31:334–341. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gough J, Chothia C. SUPERFAMILY: HMMs representing all proteins of known structure. SCOP sequence searches, alignments and genome assignments. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:268–272. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Letunic I, et al. SMART 4.0: towards genomic data integration. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:D142–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35:W182–W185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome research. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Löytynoja A, Goldman N. webPRANK: a phylogeny-aware multiple sequence aligner with interactive alignment browser. BMC bioinformatics. 2010;11:579. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Posada, D. & Crandall, K. Modeltest 3.7. Program and documentation available at, http://darwin.uvigo.es (2005).

- 76.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Molecular biology and evolution. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular biology and evolution. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:644. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lalitha S. Primer premier 5. Biotech Software & Internet Report: The Computer Software Journal for Scient. 2000;1:270–272. doi: 10.1089/152791600459894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schwede T, Kopp J, Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic acids research. 2003;31:3381–3385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Unni S, et al. Web servers and services for electrostatics calculations with APBS and PDB2PQR. Journal of computational chemistry. 2011;32:1488–1491. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.DeLano WL. Pymol: An open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newsletter On Protein Crystallography. 2002;40:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Consortium U. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic acids research. 2016;45:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhan X, et al. Peregrine and saker falcon genome sequences provide insights into evolution of a predatory lifestyle. Nature genetics. 2013;45:563. doi: 10.1038/ng.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:289–290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Felsenstein J. Phylogenies and the comparative method. The American Naturalist. 1985;125:1–15. doi: 10.1086/284325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Genome and DNA sequencing data of besra and oriental scops owl have been deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject ID PRJNA420185. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its Supplementary Material or are available from the authors upon request. More detailed information for the approaches has been revealed in the Supplementary Material.