Abstract

B. F. Skinner’s (1957) Verbal Behavior had a limited influence on empirical research in the first few decades following its publication, but an increase in empirical activity has been evident in recent years. The purpose of this article is to update previous analyses that have quantified the influence of Verbal Behavior on the scholarly literature, with an emphasis on its impact on empirical research. Study 1 was a citation analysis that showed an increase in citations to Verbal Behavior from 2005 to 2016 relative to earlier time periods. In particular, there was a large increase in citations from empirical articles. Study 2 identified empirical studies in which a verbal operant was manipulated or measured, regardless of whether or not Verbal Behavior was cited, and demonstrated a large increase in publication rate, with an increasing trend in the publication of both basic and applied experimental analyses throughout the review period. A majority of the studies were concerned with teaching verbal behavior to children with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities, but a variety of other basic and applied research topics were also represented. The results suggest a clearly increasing impact of Verbal Behavior on the experimental analysis of behavior on the 60th anniversary of the book’s publication.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40616-017-0089-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: B. F. Skinner, Citation analysis, Scientometrics, Verbal behavior

On the 60th anniversary of the publication of Verbal Behavior (Skinner, 1957), it is appropriate to take stock of its influence on the current scholarly literature. Skinner’s proposal that all of the complexities of human language could be understood in terms of operant principles suggested a novel framework for empirical investigation. However, a quarter century after its publication, it was clear that the potentially transformative effect of Verbal Behavior on the experimental analysis of language and cognition had not been realized (Michael, 1984). At that time, McPherson, Bonem, Green, and Osborne (1984) conducted the first citation analysis of Verbal Behavior. McPherson et al. identified a total of 836 citations of the book from various sources, including both books and journal articles within psychology and other disciplines, between 1957 and 1983. Although an increasing trend in citation rate was observed throughout the period, only a small percentage (3.7%) of the citations appeared in empirical journal articles. Only 19 citations (2.3% of all citations) appeared in studies that could be characterized as experimental analyses directly influenced by Skinner’s (1957) work. A number of possible reasons for the paucity of verbal behavior research were offered at this time (McPherson et al., 1984; Michael, 1984), including the interpretive rather than experimentally oriented nature of Verbal Behavior, the difficulty level of the text, the lack of an established methodology for studying verbal behavior, and Noam Chomsky’s (1959) influential and scathing (although ultimately misguided; MacCorquodale, 1970) review of Skinner’s (1957) book.

More than 20 years later, Dymond, O’Hora, Whelan, and Donovan (2006) conducted an updated citation analysis for the period of 1984 through 2004. A total of 1,093 citations to Verbal Behavior were found during this period, suggesting that its impact on the literature was increasing, including an increase in empirical activity influenced by Skinner’s (1957) work. Specifically, 20% of the citations identified by Dymond et al. came from empirical articles, and almost one third of them (6.3% of all citations) came from experimental analyses or observational studies in which a verbal operant response class was manipulated or measured. The latter figure represented a 119% increase in empirical research directly influenced by Skinner’s (1957) analysis relative to what was reported by McPherson et al. (1984). After performing an obliteration analysis—that is, a search for additional empirical articles in which verbal operants were manipulated or measured without a citation being provided to Verbal Behavior—that increase rose to 350%. Nevertheless, the empirical database remained small, with a total of 101 articles that met the criterion for direct influence, or an average of 4.8 articles per year during the review period. Dixon, Small, and Rosales (2007) subsequently conducted a further analysis of this set of empirical articles and reported that a majority of them focused on teaching verbal operants to children with developmental disabilities.

Sautter and LeBlanc (2006) provided a comprehensive review of empirical applications of Skinner’s analysis published between 1989 and 2004, updating a previous review by Oah and Dickinson (1989). Articles were included in the review if manipulation or measurement of verbal operants was mentioned in the title or abstract, regardless of whether a citation to Verbal Behavior was provided. The pattern of data was similar to that obtained by Dymond et al. (2006): The empirical database on verbal behavior had grown almost threefold in the 1990s and early 2000s, but the rate of empirical publications remained fairly low, eight being the largest number of empirical articles ever published in a single year.

Only a little over a decade has passed since the publication of the analyses conducted by Dymond et al. (2006) and Sautter and LeBlanc (2006). However, there is evidence that during this time, there has been a substantial further increase in empirical research activity influenced by Skinner’s (1957) analysis. A sharp increase in the number of empirical articles published each year in The Analysis of Verbal Behavior (TAVB) during this period has already been documented (Luke & Carr, 2015; Marcon-Dawson, Vicars, & Miguel, 2009; Presti & Moderato, 2016), and a recent article (Aguirre, Valentino, & LeBlanc, 2016) reported a large increase in empirical research on intraverbal behavior (data on other verbal operant classes were not reported). The purpose of the present study is to provide a more comprehensive analysis of the influence of Verbal Behavior on the scholarly literature from 2005 through 2016. In Study 1, we extended previous citation analyses (Dymond et al., 2006; McPherson et al., 1984) to this most recent period and categorized citing articles similarly to Dymond et al. (2006). In Study 2, we identified additional empirical articles in which verbal operant classes were manipulated or measured but in which Verbal Behavior was not cited, using procedures based on those of Sautter and LeBlanc (2006) and based on Dymond et al.’s obliteration analysis. We then analyzed the populations and verbal operants investigated in a manner similar to previous studies (Dixon et al., 2007; Sautter & LeBlanc, 2006).

Study 1

Method

A cited reference search was conducted on May 11, 2017, using the Thomson Reuters Web of Science Core Collection databases to identify articles published between the beginning of 2005 and the end of 2016 that cited Skinner’s (1957) Verbal Behavior, including all editions of the book (English and other languages) that could be found in the database. The search was restricted to entries classified as articles, book reviews, and editorial material, excluding books, book chapters, and other document types. No other restrictions were placed on the search, such as language of publication. PubMed Central archives (PubMed Central [PMC], 2000) were used to perform a manual search of the reference lists of TAVB articles from 2005 through 2014, as only the 2015 and 2016 volumes of TAVB were indexed in the Web of Science. Additionally, PsycINFO, PMC archives, and journal websites were used to perform a manual search of the reference lists of several journals that were not indexed in the Web of Science but were known by the authors to have published content related to verbal behavior. These journals—Behavior Analysis in Practice, Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice and its predecessor The Behavior Analyst Today, Behavioral Development Bulletin, European Journal of Behavior Analysis, Journal of Speech and Language Pathology – Applied Behavior Analysis, and Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention—all began publication after or shortly prior to the end of the review period covered by Dymond et al. (2006) and were not included in that study. All journal content that was available online and had a reference list was included in manual searches, except for reprinted articles.

Each citing article was coded as nonempirical or empirical based on its abstract, and empirical articles were further divided into four categories following Dymond et al. (2006). An article was coded as empirical if its abstract suggested that it included numerical data on the behavior or biological functioning of human or nonhuman subjects and was coded as nonempirical if it did not. The nonempirical category included mostly conceptual, review, and discussion pieces but also included some studies using qualitative methods (e.g., focus groups and interviews) and archival methods (e.g., content analyses and bibliometric analyses). The four categories of empirical articles were basic experimental analysis, applied experimental analysis, observational study, and other-empirical; the definition of each category is given in Table 1. The first three categories represented articles considered to be directly influenced by Verbal Behavior (Dymond et al., 2006; McPherson et al., 1984) and included only articles in which at least one verbal operant class of the subjects was purportedly manipulated or measured, as indicated in the article title, abstract, or keywords. To qualify as a verbal operant, a manipulated or measured variable had to be labeled by the authors as a mand, a tact, intraverbal, echoic, textual behavior, taking dictation, autoclitic, or another term that has been used in the literature to describe subclasses (e.g., sequelic; Vargas, 1982) or superclasses (e.g., codic; Michael, 1982) of Skinner’s (1957) verbal operant classes. If none of these terms appeared in the title, abstract, or keywords but the abstract gave a strong indication of influence by Skinner’s (1957) analysis or the authors were known to be frequent contributors to the verbal behavior literature, the full text of the article was consulted to determine if the authors had conceptualized or labeled an independent variable or a dependent variable as a verbal operant. If the full text of the article was not accessible or printed in a language that could not be deciphered by the authors, it was categorized as other-empirical based on the absence of verbal operant terms from the accessible record.

Table 1.

Categories of empirical articles

| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Basic experimental analysis | Study included experimental manipulation; one or more verbal operants were manipulated or measured for the subject(s); the primary focus of the study was to identify variables that influenced the subjects’ behavior. |

| Applied experimental analysis | Study included experimental manipulation; one or more verbal operants were manipulated or measured for the subject(s); the primary focus of the study was to bring about an improvement in the subjects’ behavior. |

| Observational study | One or more verbal operants were measured in the study, but there was no experimental manipulation. |

| Other-empirical | Study included original data on human or animal subjects but did not meet the criteria for basic experimental analysis, applied experimental analysis, or observational study. |

The first author conducted the search and coded all empirical articles. The second author independently coded 25% of the empirical articles. The two authors’ records were compared, and each entry was scored as an agreement if it was categorized in the same manner by both observers. Overall, the raters agreed on the classification of 97% of the articles; the authors reviewed the classification of the remaining three articles and other articles with similar characteristics that were not in the reliability sample and changed the coding if needed.

Results and discussion

Citation rates

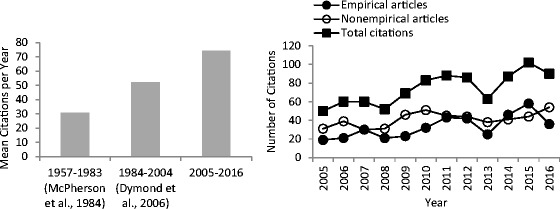

The search yielded a total of 890 citations to Verbal Behavior during the review period (2005–2016), or an average of 74 citations per year. Mean citations per year had increased by 139% from the review period covered by McPherson et al. (1984) and by 42% from the period covered by Dymond et al. (2006; left panel of Fig. 1). It is possible that some of the increase reflects improved coverage by the searched databases relative to previous review periods. However, McPherson et al. (1984) included books, book chapters, and dissertations in their review; therefore, the increase in citations from scholarly journals from the first review period may be even greater than indicated herein.

Fig. 1.

The left panel shows the mean number of annual citations of Skinner’s (1957) Verbal Behavior per year in the study by McPherson et al. (1984), the study by Dymond et al. (2006), and the present study. The right panel shows the total number of citations, citations from empirical articles, and citations from nonempirical articles for each year in the present review period

A total of 396 citations (44%) came from empirical articles, which is more than a twofold increase in proportion from the 20% reported by Dymond et al. (2006). The right panel of Fig. 1 shows the total number of citations each year as well as citations from empirical and nonempirical articles during the review period. An increasing trend in total citations and citations from empirical articles was evident throughout the review period. An increase in citations from nonempirical articles early in the review period was followed by relative stability from 2009 to 2016, such that the frequency of citations from empirical studies began to approach or exceed (2014 and 2015) nonempirical citations.

Of the 396 overall citations from empirical articles, 71 of the articles (8.0% of all citing articles) were classified as basic experimental analyses, 151 (17.0%) as applied experimental analyses, six (0.7%) as observational studies, and 168 (18.9%) as other-empirical. Comparable statistics from Dymond et al. (2006) are 1.4%, 4%, 0.9%, and 13.7%, respectively. Thus, whereas only a small minority of the empirical articles identified by Dymond et al. included manipulation or measurement of a verbal operant, a majority of the empirical articles (57.6%) identified in the present study did, and almost all of them involved experimental analysis. In addition, the mean number of empirical citations per year was 33.0 compared to 10.4 in the analysis by Dymond et al., and a mean of 19.0 citations per year fell into the basic, applied, and observational categories compared to 3.3 in the analysis by Dymond et al.

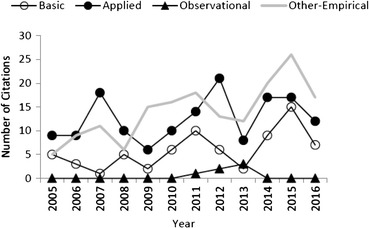

Figure 2 shows citations per year from each of the four categories of empirical articles. The steepest increasing trend was seen in citations from the other-empirical category. The rate of citations from the basic and applied experimental categories was variable, but an increasing trend was evident in the basic category, and a slight trend appeared to be present in the applied category as well. In the first 2 years of the current review period, citation rates from basic and applied experimental analyses (26 citations in 2005 and 2006) may already have been higher than in the last 2 years of the analysis by Dymond et al. (2006; see Fig. 2). We hypothesize that the difference is in large part due to an abrupt increase in the number of empirical research articles published per year in TAVB that coincided with the onset of the review period and has since persisted (Presti & Moderato, 2016); however, improved database coverage may also be partially responsible.

Fig. 2.

The number of citations of Skinner’s (1957) Verbal Behavior per year from basic experimental analyses, applied experimental analyses, observational studies, and other-empirical articles identified in Study 1

Citations to Verbal Behavior appeared in a total of 230 different journals. Table 2 displays the 25 journals in which there were five or more citations to Verbal Behavior. Not surprisingly, the table contains primarily journals dedicated to behavior analysis or other journals that frequently publish basic (e.g., Behavioral Processes) or applied (e.g., Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders) behavior–analytic research. Together, the citations shown in Table 2 accounted for 70% of all citations to Verbal Behavior during the review period. The remaining citations came from journals that spanned a wide range of topics within many disciplines, including psychology, education, business, speech–language pathology, philosophy, linguistics, and neuroscience, among others.

Table 2.

Journals with five or more citations to verbal behavior in study 1

| Rank | Journal | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Analysis of Verbal Behavior | 132 |

| 2 | Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis | 70 |

| 3 | The Psychological Record | 67 |

| 4 | The Behavior Analyst | 63 |

| 5 | European Journal of Behavior Analysis | 37 |

| 6 | Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior | 33 |

| 7 | Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice/The Behavior Analyst Today | 32 |

| 8 | Journal of Speech and Language Pathology – Applied Behavior Analysis | 27 |

| 9 | Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders | 26 |

| 10 | Journal of Organizational Behavior Management | 16 |

| 11 | Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention | 12 |

| 12–13 | Behavior Analysis in Practice | 11 |

| 12–13 | Behavioral Interventions | 11 |

| 14–16 | Behavioral Processes | 9 |

| 14–16 | Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities | 9 |

| 14–16 | Revista Lationamericana de Psicologia | 9 |

| 17 | Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders | 8 |

| 18–19 | Behavioral Development Bulletin | 7 |

| 18–19 | Psicothema | 7 |

| 20–23 | Behavior Modification | 6 |

| 20–23 | International Journal of Psychology | 6 |

| 20–23 | Journal of Mind and Behavior | 6 |

| 20–23 | Review of General Psychology | 6 |

| 24–25 | Language Sciences | 5 |

| 24–25 | Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica | 5 |

Summary

In summary, we found a substantial increase in the overall rate of citations to Verbal Behavior compared to previous citation analyses (Dymond et al., 2006; McPherson et al., 1984). In particular, there was a large increase in citations from empirical articles, including basic and experimental analyses that appeared to be directly influenced by Skinner (1957) in that one or more independent or dependent variables were conceptualized as verbal operants. These results are encouraging for the experimental analysis of verbal behavior and corroborate previous reports of increased empirical research activity related to verbal behavior in the past decade (Aguirre et al., 2016; Luke & Carr, 2015). A citation analysis, however, may not capture all such activity. Both Dymond et al. (2006) and Sautter and LeBlanc (2006) found a number of empirical articles in which verbal operants were manipulated or measured but in which Verbal Behavior was not cited. In addition, the Web of Science does not index all journals in which such work might be published, and although several nonindexed journals were searched manually for citations in Study 1, the search may not have revealed all relevant empirical research. Study 2 was undertaken in an attempt to identify additional empirical research on verbal behavior and to provide an overview of the verbal operants and populations studied during the review period.

Study 2

Method

Study 2 involved two phases. In the first phase, a search was conducted in PsycINFO for peer-reviewed articles that included the terms mand(s), tact(s), echoic(s) (excluding echoic memory), intraverbal(s), textual behavior, textual responding, taking dictation, dictation-taking, or autoclitic(s) in the title, abstract, or keywords and were published from 2005 through 2016 in any language. Articles were selected for inclusion in Study 2 if they met the criteria for a basic experimental analysis, an applied experimental analysis, or an observational study, using the same definitions as in Study 1. The resulting database was then combined with the subset of articles from Study 1 that were classified as basic experimental analyses, applied experimental analyses, or observational studies, and duplicate records were removed.

Articles in the combined database were coded for verbal operant(s) studied (mand, tact, echoic, intraverbal, autoclitic, textual behavior, taking dictation, and other) and subject population. In human studies, the subject population of each study was coded as clinical, nonclinical, or both. A participant was considered to belong to a clinical population if a diagnosis or a description of a developmental problem or sensory impairment was provided; otherwise, a nonclinical population was coded. If this information was unclear from the abstract or other information was provided in the PsycINFO record, the full text of the article was consulted when possible. The subject population in each study was additionally categorized as children if all participants were under 18 years of age, adults if all participants were 18 or older, or both if participants were both children and adults. The first author conducted the PsycINFO search and coded all articles, and the second author independently coded 26% of the articles. Agreement was 100% on the classification of articles as basic, applied, or observational; 94.9% on verbal operants studied; and 100% on subject populations.

Results and discussion

Articles included

The initial search yielded a total of 340 empirical articles that qualified for inclusion compared to the 228 articles in Study 1 in which a verbal operant was manipulated or measured. One hundred and ninety-nine articles were identical to those identified in Study 1; the remaining 141 were new to Study 2. Twenty-nine additional articles that were identified in Study 1 did not appear in the PsycINFO search but were added to the database for Study 2. Therefore, a total of 369 articles were available for analysis in Study 2 (a full list of the articles is available in the online supplemental material).

Of the 141 articles that were new to Study 2, the reference lists of 138 articles could be accessed. Of these, 122 articles did not cite Verbal Behavior in spite of using verbal operant terms to describe independent or dependent variables. The remaining 16 articles cited Verbal Behavior; 15 appeared in journals that were neither indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection databases nor searched manually in Study 1 (e.g., Acta Comportomentalia, Japanese Journal of Behavior Analysis), and one was not identified in Study 1 despite being indexed in the Web of Science.

Of the 29 articles that were identified as manipulating or measuring verbal operants in Study 1 but were not located in the PsycINFO search for Study 2, 21 articles did not contain verbal operant terms in their titles, abstracts, or keywords. These articles had been identified in Study 1 because verbal operant terms were used to describe independent or dependent variables in the Introduction or Method sections. The titles, abstracts, and keywords of two additional articles contained only verbal operant terms for which we did not search in Study 2; that is, codic (Perez & de Rose, 2010) and sequelic (Lawson & Walsh, 2007). Two articles appeared in a journal that was indexed in the Web of Science but not in PsycINFO (Psikhologicheskaya Nauka i Obrazovanie), and four articles appeared in a journal that was not indexed in either database but had been searched manually in Study 1 (European Journal of Behavior Analysis).

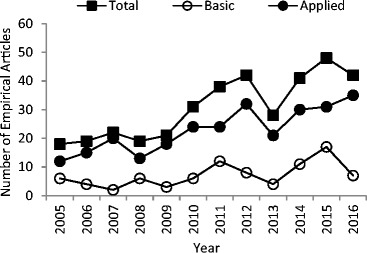

Of the 369 articles in the database, 86 articles (23%) were classified as basic experimental analyses, 275 (75%) were classified as applied experimental analyses, and eight (2%) were classified as observational studies. Observational studies were conducted to answer both basic (e.g., Cruvinel & Costa Hübner, 2013) and applied (e.g., Sundberg & Sundberg, 2011) research questions but were not classified further. Figure 3 shows the total number of articles per year in which a verbal operant was manipulated or measured, as well as the subcategories of basic and applied experimental analysis. Consistent with Study 1, an increase in verbal behavior research activity was seen throughout the review period, and an upward trend in the applied research category was more pronounced than in Study 1.

Fig. 3.

Empirical articles identified in Study 2 as including manipulation or measurement of one or more verbal operants, regardless of whether or not Verbal Behavior was cited. The figure shows the total number of articles per year as well as the subcategories of basic and applied experimental analysis

Subject populations

Not surprisingly, human participants were used in all but one study (Kuroda, Lattal, & García-Penagos, 2014, used pigeons). In one study, it was unclear if the participants belonged to a clinical population. Of the remaining studies, 72% employed participants from clinical populations only, 24% employed participants from nonclinical populations only, and 4% employed both clinical and nonclinical participants. By far the largest clinical population was individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD); one or more participants with this diagnosis appeared in 60% of all studies. Others included individuals with an intellectual disability of specified or unspecified origin (11%), unspecified developmental delays (2%), language delays or language disorders (2%), sensory impairment in the absence of other disabilities (1%), and dementia (1%); other diagnoses in the absence of developmental delay or disability were rarely reported.

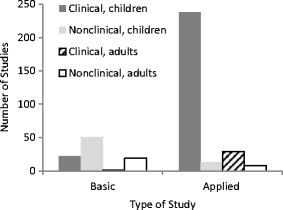

Participant age was reported in all but one human study. All participants were children in 84% of the remaining studies, all were adults in 12%, and both children and adults participated in 4% of the studies. Figure 4 shows participant populations in experimental studies by category of experimental analysis. Consistent with previous reports on participants in verbal behavior research (Dixon et al., 2007; Marcon-Dawson et al., 2009; Normand, Fossa, & Poling, 2000), children from clinical populations were by far the most prevalent category of participants in applied research studies, appearing in a total of 238 studies.

Fig. 4.

Participant populations used in basic and applied experimental analyses from 2005 through 2016 (Study 2)

Verbal operants studied

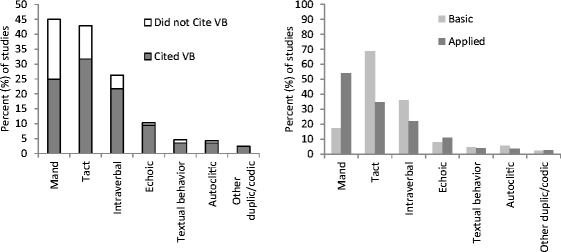

Two hundred and seventy-two studies (74%) focused primarily on a single verbal operant, two verbal operants were manipulated or measured in 70 studies (19%), and three or more were manipulated or measured in 27 studies (7%). The left panel of Fig. 5 shows the percentage of all studies in which each verbal operant was used and the proportion of each that cited Verbal Behavior. As in previous studies (Dymond et al., 2006; Sautter & LeBlanc, 2006), the mand was the most commonly investigated verbal operant, appearing in 166 studies, closely followed by the tact in 158 studies. Next came the intraverbal (97 studies), the echoic (38 studies), textual behavior (17 studies), and the autoclitic (16 studies). The other category in the figure includes dictation taking (e.g., Greer, Yuan, & Gautreaux, 2005) and other forms of duplic or codic behavior (Michael, 1982) that did not fall under the definition of echoic or textual behavior, such as mimetic behavior, referring to motor imitation of manual signs (e.g., Normand, Machado, Hustyi, & Morley, 2011), vocal spelling (e.g., de Souza & Rehfeldt, 2013), and reading musical notation (Perez & de Rose, 2010). Studies on the mand were disproportionally likely to omit a citation to Verbal Behavior.

Fig. 5.

The left panel shows the percentage of all empirical articles (i.e., basic, applied) from 2005 through 2016 (Study 2) that included manipulation or measurement of each verbal operant. The right panel shows the percentage of applied experimental analyses and the percentage of basic experimental analyses that included each verbal operant. VB = Verbal Behavior

The right panel of Fig. 5 shows the percentage of basic and applied experimental analyses that included each verbal operant as an independent variable or a dependent variable. Applied research was most likely to focus on the mand, which was included in 54% of all applied studies. In 115 studies (42% of all applied studies and 31% of the entire database), the mand was the only verbal operant studied, and less than half of these studies included a citation to Verbal Behavior. A third (35%) of all applied studies included the tact, and 22% included the intraverbal. Basic studies, by contrast, were most likely to investigate the tact (69%), followed by the intraverbal (36%). The mand was included in 15 basic research studies, a majority of which also included the tact as an additional variable and investigated transfer between the two operants (e.g., Egan & Barnes-Holmes, 2011).

Publication sources

Empirical research in which verbal operants were manipulated or measured appeared in 44 journals during the review period (Table 2), including 12 journals published in part or in whole in languages other than English. The largest number of articles appeared in TAVB and the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis; together, these journals contained more than half of the articles included in the Study 2 database.

Summary

Study 2 provided additional evidence for an increase in research activity related to Skinner’s (1957) analysis of verbal behavior in the period of 2005 to 2016. A large number of empirical articles were identified that made use of the major concepts introduced in Verbal Behavior without including a citation to the book; a majority of these were applied research articles on the mand. Almost three quarters of all studies were classified as applied experimental analyses, and a large majority of these studies were conducted with young, clinical populations, most commonly children with an ASD diagnosis. In addition, a substantial portion of applied studies (almost a third of the entire database) focused exclusively on the mand, including both studies on establishing and expanding the manding repertoires of individuals at various levels of language functioning (e.g., Carnett & Ingvarsson, 2016; Shillingsburg, Gayman, & Walton, 2016) and studies on the replacement of disruptive behavior with appropriate manding (e.g., Derosa, Fisher, & Steege, 2015). In addition to applied research, a total of 86 basic research studies were identified, or a mean of 7.2 studies per year. The frequency of publication of both basic and applied studies appeared to be on the rise. The findings in Studies 1 and 2 suggest that on the 60th anniversary of the publication of Skinner’s (1957) book, it is generating more empirical research than has ever been documented previously (Dymond et al., 2006; McPherson et al., 1984; Sautter & LeBlanc, 2006).

General discussion

The present data suggest that Verbal Behavior continues to influence the scholarly literature and that in the last decade, there has been a proliferation of both basic and applied research inspired by Skinner’s (1957) work. Study 1 showed increasing citation rates to Verbal Behavior from 2005 through 2016 that included an increase in citations from empirical sources compared to the analysis by Dymond et al. (2006). In Study 2, we identified a total of 369 empirical research articles on verbal operants that were published in the 12-year review period compared to the 60 articles in a 16-year period identified by Sautter and LeBlanc (2006). In addition, over 30 articles have been published per year since 2010, with the exception of 28 articles in 2013, and over 40 articles were published in each of the last 3 years of the review period. As a result, it can no longer be claimed that Verbal Behavior has failed to inspire a vigorous program of empirical research.

Given the large numbers of behavior analysts who provide services to children diagnosed with ASD, it was unsurprising to find that the majority of the studies were applied in nature and focused on improving the verbal repertoires of individuals from this population. In the past, concern has been raised that the influence of Verbal Behavior on empirical research has been selectively limited to research that falls into this category. Dixon et al. (2007) concluded that

although the invaluable clinical significance of this research is not questioned, this alone cannot sustain the reliance on Verbal Behavior as a conceptualization of human language. Consequently, there is a need to expand basic research on verbal behavior to typically developing individuals and to more advanced forms of language. (p. 204; see also Dymond & Alonso-Alvarez, 2010)

Although this is a worthy concern, other types of research were represented as well—for example, applied studies addressed the use of equivalence-based instruction in higher education (e.g., O’Neill, Rehfeldt, Ninness, Muñoz, & Mellor, 2015) and teaching second-language learners (e.g., May, Downs, Marchant, & Dymond, 2016). In addition, the number of basic research studies identified was nontrivial and suggests that at least some of the need referenced by Dixon et al. (2007) is beginning to be filled. An analysis of the specific research questions addressed is beyond the scope of this article, but it is clear that the large number of studies identified represent not only advances in the development of assessment methods (e.g., Gross, Fuqua, & Merritt, 2013; Lerman et al., 2005), intervention techniques (e.g., Brodhead, Higbee, Gerencser, & Akers, 2016; Lechago, Howell, Caccavale, & Peterson, 2013), and curricula (e.g., McKeel, Rowsey, Belisle, Dixon, & Szekely, 2015) but also explorations of variables that influence verbal behavior (e.g., Sautter, LeBlanc, Jay, Goldsmith, & Carr, 2011; Stocco, Thompson, & Hart, 2014) and investigations on the role of verbal repertoires in other complex behavior (e.g., Carp & Petursdottir, 2015; Miguel et al., 2015). Verbal Behavior, although itself based on extrapolation from nonhuman research, suggests a large number of potential research topics (Sundberg, 1991), and although many of them likely remain unexplored at this time (see Presti & Moderato, 2016), the increasing trend in both basic and applied research activity is cause for optimism.

Although we used an operational distinction between basic and applied research consistent with previous citation analyses (Dymond et al., 2006; McPherson et al., 1984), this distinction is not necessarily straightforward and ignores the translational nature of many studies. We classified studies liberally as applied whenever improvement in societally relevant participant behavior appeared to be sought, regardless of whether or not the studies constituted applied behavior analysis as defined by Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968). Thus, some studies that were categorized as applied also sought answers to more basic questions regarding the variables that influence verbal and nonverbal repertoires (e.g., Causin, Albert, Carbone, & Sweeney-Kerwin, 2013; Drasgow, Martin, Chezan, Wolfe, & Halle, 2016). Likewise, some studies categorized as basic sought to produce information of practical value (e.g., Ribeiro, Miguel, & Goyos, 2015). Such translational research efforts may be particularly important to evaluating the utility of Skinner’s (1957) conceptualization.

Another limitation is that similar to previous studies (Dymond et al., 2006; McPherson et al., 1984; Sautter & LeBlanc, 2006), identification of direct influence by Verbal Behavior in Study 2 was based on whether a verbal operant was manipulated or measured and labeled as such by the investigators. It is, however, entirely possible to study the classes of controlling variables that Skinner (1957) described without making use of his invented labels (e.g., mand, tact), and it might even be argued that these labels constitute jargon that may be unhelpful for communication outside of behavior analysis (e.g., Becirevic, Critchfield, & Reed, 2016). During the review period, Verbal Behavior was cited in 168 empirical research articles that fell outside of the categories of basic and applied experimental analysis and observational studies. The other-empirical category in Study 1 was broad and included many types of research from within and outside of behavior analysis. We did not undertake a systematic analysis of studies in this category, but it is clear that although the other-empirical category included a large number of studies in which Verbal Behavior was cited for relatively trivial reasons, it also included studies that appeared to be substantially influenced by Skinner’s (1957) ideas—or at least invoked them in the interpretation of results—even though a verbal operant was not studied or was not labeled as such (e.g., Cortez, de Rose, & Miguel, 2014; Esch, Carr, & Grow, 2009). As a result, it is possible that the data on basic and applied experimental analyses shown in Figs. 2 and 3 underestimate the direct influence of Verbal Behavior on empirical research. Conversely, in some of the articles identified, the direct influence of Verbal Behavior may have been minimal in the sense of being limited to the use of a verbal operant term to label a variable (e.g., some studies on functional communication training or alternative and augmentative communication).

The major difference between the methods used to identify direct influence in Study 1 (Fig. 2) and Study 2 (Fig. 3) is that, similar to Dymond et al. (2006) and McPherson et al. (1984), Study 1 relied on citations to Verbal Behavior to identify potential influence, whereas Study 2 considered all articles in which verbal operant terms were used to describe manipulated or measured variables, as in the analysis by Sautter and LeBlanc (2006). Study 2 identified 122 articles that met this criterion but did not cite Verbal Behavior, whereas Sautter and LeBlanc (2006) identified 14 and Dymond et al.’s (2006) obliteration analysis identified 34. As shown in Fig. 5, citation omissions were most likely to occur in studies on the mand but also occurred for other verbal operants, particularly the tact and the intraverbal. These data suggest that the scholarly community no longer perceives the use of the terms mand, tact, and intraverbal to require a citation to Verbal Behavior. In other words, obliteration has occurred in the sense that Skinner’s (1957) verbal operant terms may be increasingly thought of as common knowledge within behavior analysis, similar to reinforcement and stimulus control. One implication of these findings is that future attempts to quantify the influence of Verbal Behavior on the scholarly literature should use methods similar to those used in Study 2—instead of simply counting citations as we did in Study 1—in order to capture the full range of articles influenced by Skinner’s (1957) conceptual system.

It may seem odd for scientific theory to lie dormant for decades before it begins to influence empirical science to an appreciable extent. However, many examples exist in the sciences of theories that began to gain acceptance or generate programs of research long after their initial introduction (Wolinsky, 2008), in some cases because practical need became pressing. In the case of Verbal Behavior, demand for effective behavioral interventions for young children diagnosed with ASD began to rise in the 1990s, leading many behavior analysts to work with children whose language delays required effective programming. Operant conditioning methods had long been used to teach language skills to this population (e.g., Lovaas, Berberich, Perloff, & Schaeffer, 1966; Sailor & Taman, 1972). However, Skinner’s (1957) analysis eventually came to be promoted as a conceptual foundation upon which this work could rest and from which it could be advanced further (e.g., Sundberg & Michael, 2001). These developments may have driven a large part of the increase in empirical research documented in the present study, both directly by directing researchers and practitioners to Skinner’s (1957) analysis for solutions to practical problems and indirectly through an increase in the number of behavior analysts being trained in graduate programs worldwide. The ability to distinguish between Skinner’s (1957) elementary verbal operants and to implement mand, tact, intraverbal, and echoic training is included in the current behavior analyst task list of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB, 2012). In addition, the new edition, which goes into effect in 2022, specifies that behavior analysts should be able to “use Skinner’s analysis to teach verbal behavior” (BACB, 2017, p. 4). As a result, current and future generations of behavior analysis graduate trainees are continuing to be exposed to Skinner’s (1957) work in large numbers, which is likely to generate additional interest in its empirical study.

Skinner (1978, p. 122) predicted that Verbal Behavior would ultimately prove to be his most important work. Although Skinner did not specify how he expected its importance to be assessed, a reasonable guess might be that he hoped for future research to demonstrate the utility of the analysis for predicting and controlling verbal behavior and for mainstream acceptance to follow. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the influence of Verbal Behavior is largely contained within the field of behavior analysis at this time. However, an experimental analysis of verbal behavior has clearly taken off, and in the area of establishing elementary verbal operants, the utility of the analysis for prediction and control seems evident. But although diverse topics were studied during the review period, much unexplored territory remains. For example, few studies directly addressed the topic of multiple control over verbal behavior, which was one of Skinner’s (1957) primary analytical tools (Michael, Palmer, & Sundberg, 2011), and the only topics we encountered from Parts IV and V of Verbal Behavior were autoclitics and grammar, which were addressed in a handful of studies. Thus, the data do not suggest that Skinner’s prediction has been fully realized at this time. However, the increase in empirical activity that has occurred in the last decade may well be signaling the dawn of a new era.

Table 3.

Journals with five or more empirical articles in study 2

| Rank | Journal | Articles |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Analysis of Verbal Behavior | 97 |

| 2 | Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis | 95 |

| 3 | The Psychological Record | 26 |

| 4 | Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders | 21 |

| 5 | Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior | 12 |

| 6–7 | Behavioral Interventions | 11 |

| 6–7 | Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities | 11 |

| 8 | Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention | 10 |

| 9 | Journal of Speech and Language Pathology – Applied Behavior Analysis | 9 |

| 10–11 | Behavior Modification | 7 |

| 10–11 | Research in Developmental Disabilities | 7 |

| 12 | Journal of Behavioral Education | 5 |

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 93 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank James R. Mellor for providing assistance with the development of inclusion criteria and definitions in the initial stages of this project.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguirre AA, Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA. Empirical investigations of the intraverbal: 2005–2015. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2016;32:139–153. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0064-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becirevic A, Critchfield TS, Reed DD. On the social acceptability of behavior-analytic terms: Crowdsourced comparisons of lay and technical language. The Behavior Analyst. 2016;39:305–317. doi: 10.1007/s40614-016-0067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) BCBA/BCaBA Task List. 4. Author: Littleton, CO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) BCBA/BCaBA Task List. 5. Author: Littleton, CO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brodhead MT, Higbee TS, Gerencser KR, Akers JS. The use of a discrimination-training procedure to teach mand variability to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49:34–48. doi: 10.1002/jaba.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnett A, Ingvarsson ET. Teaching a child with autism to mand for answers to questions using a speech-generating device. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2016;32:233–241. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp CL, Petursdottir AI. Intraverbal naming and equivalence class formation in children. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;104:223–240. doi: 10.1002/jeab.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causin KG, Albert KM, Carbone VJ, Sweeney-Kerwin EJ. The role of joint control in teaching listener responding to children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013;7:997–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. A review of B. F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. Language. 1959;35:26–58. doi: 10.2307/411334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez MD, de Rose J, Miguel CF. The role of correspondence training on children’s self-report accuracy across tasks. The Psychological Record. 2014;64:393–402. doi: 10.1007/s40732-014-0061-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cruvinel AC, Costa Hübner MM. Analysis of the acquisition of verbal operants in a child from 17 months to 2 years of age. The Psychological Record. 2013;63:735–750. doi: 10.11133/j.tpr.2013.63.4.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derosa NM, Fisher WW, Steege MW. An evaluation of time in establishing operation on the effectiveness of functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48:115–130. doi: 10.1002/jaba.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza AA, Rehfeldt RA. Effects of dictation-taking and match-to-sample training on listing and spelling responses in adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:792–804. doi: 10.1002/jaba.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Small SS, Rosales R. Extended analysis of empirical citations with Skinner’s Verbal Behavior: 1984–2004. The Behavior Analyst. 2007;30:197–209. doi: 10.1007/BF03392155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drasgow E, Martin CA, Chezan LC, Wolfe K, Halle JW. Mand training: An examination of response-class structure in three children with autism and severe language delays. Behavior Modification. 2016;40:347–376. doi: 10.1177/0145445515613582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Alonso-Alvarez B. The selective impact of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior on empirical research: A reply to Schlinger (2008) The Psychological Record. 2010;60:355–360. doi: 10.1007/BF03395712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, O’Hora D, Whelan R, Donovan A. Citation analysis of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior: 1984–2004. The Behavior Analyst. 2006;29:75–88. doi: 10.1007/BF03392118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan CE, Barnes-Holmes D. Examining antecedent control over emergent mands and tacts in young children. The Psychological Record. 2011;61:127–140. doi: 10.1007/BF03395750. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esch BE, Carr JE, Grow LL. Evaluation of an enhanced stimulus–stimulus pairing procedure to increase early vocalizations of children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:225–241. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer RD, Yuan L, Gautreaux G. Novel dictation and intraverbal responses as a function of a multiple exemplar instructional history. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:99–116. doi: 10.1007/BF03393012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, A. C., Fuqua, R. W., & Merritt, T. A. (2013). Evaluation of verbal behavior in older adults. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 29, 285–299. 10.1007/BF03393126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kuroda T, Lattal KA, García-Penagos A. An analysis of an autoclitic analogue in pigeons. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2014;30:89–99. doi: 10.1007/s40616-014-0019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson TR, Walsh D. The effects of observational training on the acquisition of reinforcement for listening. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention. 2007;4:430–452. doi: 10.1037/h0100383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lechago SA, Howell A, Caccavale MN, Peterson CW. Teaching “how?” mand-for-information frames to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:781–791. doi: 10.1002/jaba.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman DC, Parten M, Addison LR, Vorndran CM, Volkert VM, Kodak T. A methodology for assessing the functions of emerging speech in children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:303–316. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.106-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovaas OI, Berberich JP, Perloff BF, Schaeffer B. Acquisition of imitative speech by schizophrenic children. Science. 1966;151:705–707. doi: 10.1126/science.151.3711.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke MM, Carr JE. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior: A status update. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2015;31:153–161. doi: 10.1007/s40616-015-0043-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCorquodale K. On Chomsky’s review of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1970;13:83–99. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1970.13-83. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcon-Dawson A, Vicars SM, Miguel CF. Publication trends in The Analysis of Verbal Behavior: 1999–2008. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2009;25:123–132. doi: 10.1007/BF03393076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May RJ, Downs R, Marchant A, Dymond S. Emergent verbal behavior in preschool children learning a second language. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49:711–716. doi: 10.1002/jaba.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeel AN, Rowsey KE, Belisle J, Dixon MR, Szekely S. Teaching complex verbal operants with the PEAK relational training system. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8:241–244. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0067-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson A, Bonem M, Green G, Osborne JG. A citation analysis of the influence of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. The. Behavior Analyst. 1984;7:157–167. doi: 10.1007/BF03391898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael J. Skinner’s elementary verbal relations: Some new categories. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1982;1:1–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03392791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael J. Verbal behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1984;42:363–376. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1984.42-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael J, Palmer DC, Sundberg ML. The multiple control of verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2011;27:3–22. doi: 10.1007/BF03393089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel CF, Frampton SE, Lantaya CA, LaFrance DL, Quah K, Meyer CS, Fernand JK. The effects of tact training on the development of analogical reasoning. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;104:96–118. doi: 10.1002/jeab.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normand MP, Fossa JF, Poling A. Publication trends in The Analysis of Verbal Behavior: 1982–1998. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2000;17:167–173. doi: 10.1007/BF03392963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normand MP, Machado MA, Hustyi KM, Morley AJ. Infant sign training and functional analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:305–314. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oah S, Dickinson AM. A review of empirical studies of verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1989;7:53–68. doi: 10.1007/BF03392837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J, Rehfeldt RA, Ninness C, Muñoz BE, Mellor J. Learning Skinner’s verbal operants: Comparing an online stimulus equivalence procedure to an assigned reading. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2015;31:255–266. doi: 10.1007/s40616-015-0035-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez WF, de Rose JC. Recombinative generalization: An exploratory study in musical reading. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2010;26:51–55. doi: 10.1007/BF03393082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presti G, Moderato P. Verbal behavior: What is really researched? An analysis of the papers published in TAVB over 30 years. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2016;17:166–181. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2016.1249259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- PubMed Central (PMC) (2000). PubMed central archives. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/

- Ribeiro DM, Miguel CF, Goyos C. The effects of listener training on discriminative control by elements of compound stimuli in children with disabilities. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2015;104:48–62. doi: 10.1002/jeab.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sailor W, Taman T. Stimulus factors in the training of prepositional usage in three autistic children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1972;5:183–190. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1972.5-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sautter RA, LeBlanc LA. Empirical applications of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior with humans. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2006;22:35–48. doi: 10.1007/BF03393025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sautter RA, LeBlanc LA, Jay AA, Goldsmith TR, Carr JE. The role of problem solving in complex intraverbal repertoires. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:227–244. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillingsburg MA, Gayman CM, Walton W. Using textual prompts to teach mands for information using “who? ”. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2016;32:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s40616-016-0053-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Verbal Behavior. Acton, MA: Copley; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Reflections on behaviorism and society. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Stocco CS, Thompson RH, Hart JM. Teaching tacting of private events based on public accompaniments: Effects of contingencies, audience control, and stimulus complexity. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2014;30:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s40616-014-0006-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML. 301 research topics from Skinner’s book Verbal Behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1991;9:81–96. doi: 10.1007/BF03392862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML, Michael J. The benefits of Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior for children with autism. Behavior Modification. 2001;25:698–724. doi: 10.1177/0145445501255003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML, Sundberg CA. Intraverbal behavior and verbal conditional discriminations in typically developing children and children with autism. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2011;27:23–43. doi: 10.1007/BF03393090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas EA. Intraverbal behavior: The codic, duplic, and sequelic subtypes. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1982;1:5–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03392792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolinsky H. Paths to acceptance: The advancement of scientific knowledge is an uphill struggle against ‘accepted wisdom. EMBO Reports. 2008;9:416–418. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 93 kb)