Abstract

Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT) is an evidence-based self-help therapeutic method and over 100 studies demonstrate its efficacy. However, information about the physiological effects of EFT is limited. The current study sought to elucidate EFTs mechanisms of action across the central nervous system (CNS) by measuring heart rate variability (HRV) and heart coherence (HC); the circulatory system using resting heart rate (RHR) and blood pressure (BP); the endocrine system using cortisol, and the immune system using salivary immunoglobulin A (SigA). The second aim was to measure psychological symptoms. Participants (N = 203) were enrolled in a 4-day training workshop held in different locations. At one workshop (n = 31), participants also received comprehensive physiological testing. Posttest, significant declines were found in anxiety (−40%), depression (−35%), posttraumatic stress disorder (−32%), pain (−57%), and cravings (−74%), all P < .000. Happiness increased (+31%, P = .000) as did SigA (+113%, P = .017). Significant improvements were found in RHR (−8%, P = .001), cortisol (−37%, P < .000), systolic BP (−6%, P = .001), and diastolic BP (−8%, P < .000). Positive trends were observed for HRV and HC and gains were maintained on follow-up, indicating EFT results in positive health effects as well as increased mental well-being.

Keywords: anxiety, cortisol, immunity, heart rate variability, Emotional Freedom Techniques

A large body of research identifies associations between physiological and psychological symptoms. A systematic review of 31 studies, including 16 922 patients, found that objective physiological measures of health as well as medical diagnoses were strongly correlated with anxiety and depression.1 A meta-analysis of 244 studies found an association between psychological symptoms and somatic syndromes.2 A large-scale international study of 25 916 patients at 15 primary care centers in 14 countries on 5 continents found a significant association (P = .002) between depression and somatic symptoms in 69% of patients.3 Many other studies of specific conditions identify links between levels of psychological well-being and physiological measures of health.

Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT) is a novel therapy that combines both cognitive and somatic elements (described below). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated its efficacy for both physiological and psychological symptoms.4,5 A current research bibliography lists more than 100 studies published in peer-reviewed journals (Research.EFTuniverse.com). Its efficacy extends across a wide sample of populations, including college students,6 veterans,7,8 pain patients,9,10 overweight individuals,11–13 hospital patients,14,15 athletes,16,17 health care workers,18 gifted students,19 chemotherapy patients,20 and phobia sufferers.21–23 When measured against the standards of the American Psychological Association’s Division 12 Task Force on Empirically Validated Treatments, EFT is found to be an “evidence-based” practice for anxiety, depression, phobias, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).4,5

Emotional Freedom Techniques

Since its inception in 1995, EFT has been a manualized method,7,24 leading to uniform application research, training, and clinical practice. EFT is a brief intervention combining elements of exposure, cognitive therapy, and somatic stimulation of acupressure points on the face and body. Participants typically identify a concern or issue they wish to address with the technique and rate their level of distress on a Likert-type scale out of 10 (10 is the maximum amount of distress and 0 represents the minimum or a neutral state). This is called a Subjective Unit of Distress (SUDS) scale and has long been used as a subjective measure of a participant’s discomfort in therapy.25 Participants then state their concern in a “Setup Statement,” which assists in turning them into their level of distress. This is typically stated in this format “Even though I have this problem (eg, anger), I deeply and completely accept myself.” The first half of the setup statement emphasizes exposure, while the second half frames the traumatizing event in the context of self-acceptance. The participant then engages in the somatic tapping process on acupoints on the body while they repeat a shortened phrase to stay engaged (eg, feel angry). This is called the “Reminder Phrase.” The tapping sequence uses 8 acupoints on the face and upper body and is normally repeated until the SUDS rating is very low (1 or 0).

Anxiety

EFT has been extensively investigated for anxiety and depression. In the first large-scale study of 5000 patients seeking treatment for anxiety across 11 clinics over a 5.5-year period, patients received either traditional anxiety treatment in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), with medication if needed, or acupoint tapping with no medication.26 An improvement was found in 90% of patients who received acupoint tapping therapy compared to 63% of the CBT participants. Only 3 acupoint tapping sessions were needed before an individual’s anxiety reduced, while an average of 15 was needed for CBT to show results. Complete relief of symptoms was seen in 76% of people in the acupoint taping group compared with 51% of people in the CBT group. One year later, the improvements seen were maintained by 78% of the acupoint group compared with 69% of the CBT group. Other studies also indicate equivalence or superiority to CBT.27–29

Similarly, a study of self-applied EFT for anxiety, depression, pain, and cravings in 216 health care workers resulted in significant improvements on all distress subscales and ratings of pain, emotional distress, and cravings following 2 hours of intervention, with gains maintained at follow-up. The severity and range of psychological symptoms was reduced, and greater subsequent use of EFT was associated with a steeper decrease in symptoms, although not in symptom range or breadth.18

A meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials of EFT for anxiety disorders (n = 658) found a very large treatment effect of d = 1.23 (95% CI 0.82-1.64, P < .001), while the effect size for combined controls was 0.41 (95% CI 0.17-0.67, P = .001). EFT treatment was associated with a significant decrease in anxiety scores, even when accounting for the effect size of control treatment.30

Depression

A meta-analysis of EFT for depression examined 20 studies.31 These included 8 outcome studies (n = 461) as well as 12 randomized controlled trials (n = 398). EFT demonstrated a very large effect size in the treatment of depression. Cohen’s d across all studies was 1.31, with little difference between randomized controlled trials and uncontrolled outcome studies. Effect sizes at posttest, less than 90 days, and greater than 90 days were 1.31, 1.21, and 1.11, respectively, indicating durable maintenance of participant gains. EFT was more efficacious than physical interventions such as diaphragmatic breathing and as well as psychological interventions such as supportive interviews.31

The health care workers study also found a significant reduction in depression after EFT.18 A randomized controlled trial with a population of 59 veterans successfully treated for PTSD also identified a significant reduction in depressive symptoms after six 1-hour EFT sessions.32 Church et al6 reported that after brief group intervention using EFT for depression in 18 college students, those who received EFT were found to have significantly less depression than those who did not receive it, with an average depression score in the “nondepressed range” following treatment, compared to the control group who demonstrated no change in depressive symptoms. More recent research comparing EFT to CBT for 10 patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder, found after 8 weeks of group treatment (16 hours), both interventions produced significant reductions in depressive symptoms. The CBT group indicated a significant reduction postintervention, but this was not maintained over time. The EFT group however, showed a delayed effect of significant reductions in symptoms at 3- and 6-month follow-ups.27

Physiological Markers

The effect of EFT on medical diagnoses has been the subject of several studies. Chronic disease patients may benefit from a holistic health care and research has begun to consider the physiological changes that occur after EFT. A recent qualitative study that explored practitioners’ experiences of using EFT to support chronic disease patients indicated that while EFT was one technique, “many emotions” emerged and “tapping on the physical” for pain perception, and negative emotions that may increase the perceived intensity and limiting impacts of physical pain were important.33

Other studies of physical conditions responding to EFT have included fibromyalgia,34 psoriasis,35 tension headaches,9 frozen shoulder,10 pulmonary injuries,36 chronic pain,37 chemotherapy side effects,20 traumatic brain injury,38 insomnia,39 and seizure disorders.40 Some studies of psychological symptoms have included a physiological measure. Church and Downs41 examined psychological trauma in athletes and also measured heart rate. Wells et al21 included pulse rate as a measure for phobia sufferers. Church et al42 performed a triple-blind randomized controlled trial comparing EFT to talk therapy and rest in a non-clinical sample of 83 participants. They found significant declines in the stress hormone cortisol. However, a trial with a smaller N did not have sufficient power to identify significant cortisol reductions.9 Two clinical case histories also report cortisol reductions.43,44

The most revealing studies of the physiological aspects of EFT have examined its epigenetic effects. A population of veterans with PTSD received 10 EFT sessions.45 It found regulation of 6 genes associated with inflammation and immunity. A pilot study comparing an hour-long EFT session with placebo in 4 nonclinical participants found differential expression in 72 genes.46 These included genes associated with the suppression of cancer tumors, protection against ultraviolet radiation, regulation of type 2 diabetes insulin resistance, immunity from opportunistic infections, antiviral activity, synaptic connectivity between neurons, synthesis of both red and white blood cells, enhancement of male fertility, building white matter in the brain, metabolic regulation, neural plasticity, reinforcement of cell membranes, and the reduction of oxidative stress. The broad function of this suite of genes is similar to that found in Church et al,10 confirming the association of EFT with the downregulation of inflammation and stress markers and the upregulation of immune markers.

Generalizability

The question of whether EFTs psychological effects are generalizable has been addressed in a number of studies. Wells et al21 original study of EFT for small animal phobias found that EFT produced greater decrease in intense fear of small animals than did a comparison breathing condition. A partial replication and extension by Baker and Sigel22 assessed whether such findings reflected (a) nonspecific factors common to many forms of psychotherapy, (b) some methodological artifact (such as regression to the mean, fatigue, or the passage of time), and/or (c) therapeutic ingredients specific to EFT. For most dependent variables, the EFT condition showed a significant decrease in fear of small animals immediately after, and again 1.38 years after, one 45-minute intervention, whereas a supportive interview and no-treatment condition did not.

The health care workers study18 found no significant difference between five 1-day workshops delivered by 2 different trainers. A replication of that study with EFT delivered by 5 different trainers in heterogenous settings noted the same effect.47 A study explicitly designed to determine EFTs generalizability compared effects in 2 heterogeneous groups.48 It found no significant difference.

EFT has been found efficacious in widely disparate groups, including hospital patients, war veterans, victims of sexual violence, school children, college students, teachers, health care workers, cancer patients, athletes, presurgery patients, mothers, dental patients, psychotherapists, diabetics, and survivors of natural disasters. Treatment time frames ranging from 15 minutes to ten 1-hour sessions have been successful. Studies have delivered EFT in a variety of formats, including online courses for weight loss and cravings (eg, Stapleton et al49) and self-administered EFT for fibromyalgia (Brattberg et al),34 via telephone sessions, in groups, and in individual counseling sessions. The breadth of populations, settings and delivery methods encompassed in these studies provides indication that EFTs effects can be considered generalizable.

Dismantling Studies

Because of the interest in the mechanism of change and active ingredient of EFT, several dismantling studies have been conducted. The first dismantling study included 119 university students and compared EFT points, sham points, and tapping on a doll, and also included a control group who did nothing.50 While significant reductions in self-reported fear occurred for all 3 tapping groups but not the nontapping group, the students used their forefinger to tap, which inadvertently stimulated an acupuncture point. The EFT group also included acupoints not in the typical process and omitted others, and the study did not use valid assessments nor full randomization to the groups.

A study of university students (EFT or a control group who received mindful breathing instead of tapping) found the EFT group reported more significant increases in enjoyment, hope, and pride and more significant decreases in anger, anxiety, and shame than did the breathing control group.51 However, the mindful breathing control group did not use the EFT setup or reminder statements, so while the actual tapping was the major difference to the control group, it was not the only difference.

The next study involved 56 university students who were assessed for stress symptoms and randomly allocated to an EFT group or a control group who tapped on sham points.52 The students reported a 39.3% reduction in stress symptoms in the EFT group but the sham tapping group only reported an 8.1% decrease. This study was, however, limited in that the stress questionnaire they used had not been validated and one of the investigators led both the experimental and control groups, possibly contaminating the results.

A 2015 study involved 126 school teachers (assessed for burnout risk) and is possibly the best dismantling study to date.53 A control group tapped on the left forearm, about an inch above the wrist, with the underside of the fingers of the open right hand. This was important because no finger points were used or unintentionally activated (as in the first study discussed). Everything else was identical. Results indicated the EFT group was superior to the sham points group on the 3 indicators of burnout being tracked (Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Personal Accomplishment).

Finally, a recent meta-analysis of 6 dismantling or partial dismantling studies indicates that the acupuncture component is an essential ingredient, and not due to placebo, nonspecific effects of any therapeutic method, or non-acupressure components, in the rapid outcomes shown in EFT clinical trials.54

The Present Study

While the foregoing studies of physiological markers typically examine a cluster of diagnostic systems with EFT treatment, the current study sought to elucidate EFTs common underlying physiological mechanisms of action. The systems studied included the autonomic nervous system (ANS) by measuring heart rate variability (HRV) and heart coherence (HC); the circulatory system by assessing resting heart rate (RHR) and blood pressure (BP); the endocrine system by evaluating cortisol, and the immune system by examining levels of salivary immunoglobulin A (SigA). After successful training in emotional regulation, HC increases and a reduction (improvement) in HRV is found.55 The current study also assessed psychological symptoms of anxiety, depression, PTSD, pain, cravings, and happiness, and the relationship of psychological symptoms to physiological markers.

Based on prior research, it was hypothesized that EFT would result in significant decreases in the psychological constructs of anxiety, depression, PTSD, pain and cravings, as well as the physiological markers of HRV, cortisol, RHR, and BP. It was further hypothesized that an increase in happiness, immune response (SigA), HC, and would be identified.

The second hypothesis of the study was that psychological change would be robust and durable across a range of settings and instructors. If EFT effects were due to the intervention of a particularly gifted therapist, they should not be as robust in groups trained by other therapists. If, on the other hand, psychological improvement is found regardless of the individual delivering the training, or the setting in which it is delivered, it can be reasonably concluded that the effects measured are due to the clinical EFT method itself and not to some unique characteristic of a single individual or the stress-reducing effects of a unique setting.

Methods

The study included 203 participants at 6 Clinical EFT workshops. The workshops were taught by a variety of instructors trained and certified in Clinical EFT, the evidence-based form of the technique.7 To measure physiological change, participants at one of these workshops (n = 31) also received a comprehensive battery of medical tests. Psychological testing was similar at all 6 workshops, with pre- and postmeasures, and a follow-up during the subsequent year. Physiological measures were not assessed at follow-up since data collection was performed via email. Table 1 represents the baseline characteristics of study participants at recruitment. The majority of participants were women (65%) older than 50 years.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants at Recruitment.

| Demographic and Baseline Characteristics | Subjects | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 203 | 30 (14.8) | 170 (83.7) |

| Age, years | |||

| Mean | 50.45 | 48.13 | 50.80 |

| Standard deviation | 12.35 | 14.76 | 11.96 |

| Min-Max | 19-81 | 22-75 | 19-81 |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| High school/College | 14 (6.9) | 3 | 11 |

| University | 55 (27.1) | 9 | 46 |

| Postgraduate | 86 (42.4) | 15 | 71 |

| Unknown | 48 (23.6) | 3 | 42 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder feelings | |||

| Mean | 2.54 | 2.57 | 2.51 |

| Standard deviation | 1.24 | 1.50 | 1.17 |

| Min-Max | 1-5 | 1-5 | 1-5 |

| Pain | |||

| Mean | 4.09 | 3.54 | 4.16 |

| Standard deviation | 2.49 | 2.40 | 2.49 |

| Min-Max | 0-10 | 0-8 | 0-10 |

| Happiness | |||

| Mean | 7.28 | 7.39 | 7.30 |

| Standard deviation | 2.10 | 2.41 | 2.03 |

| Min-Max | 0-10 | 0-10 | 1-10 |

| Anxiety | |||

| Mean | 8.35 | 7.31 | 8.54 |

| Standard deviation | 3.85 | 3.95 | 3.82 |

| Min-Max | 0-20 | 1-18 | 0-20 |

| Depression | |||

| Mean | 4.04 | 4.14 | 3.96 |

| Standard deviation | 3.18 | 3.29 | 3.07 |

| Min-Max | 0-14 | 0-13 | 0-13 |

| Cravings | |||

| Mean | 6.47 | 5.71 | 6.64 |

| Standard deviation | 2.53 | 3.03 | 2.37 |

| Min-Max | 0-10 | 0-10 | 0-10 |

Measures

Subjects were assessed for depression and anxiety using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond et al).56 HADS includes 7 questions related to depression and seven questions related to anxiety. Each item is scored from 0 to 3 and the score is totaled. Thus, subjects can score from 0 to 21 for either anxiety or depression. Scores for the HADS were calculated for anxiety and depression separately. A score of >8 for either is considered clinical. Happiness,57 pain,58 and cravings were assessed using an 11-item Likert-type scale (SUDS rating). PTSD was assessed with the 2-item form of the PTSD Checklist (PCL; Lang et al).59 All assessments are reliable and valid.

Blood pressure and heart rate were measured using a standard blood pressure cuff (Omron 3). HRV and HC were assessed using HeartMath Pro Plus hardware and software (HeartMath LLC, Boulder Creek, CA). Cortisol and SigA were assessed using saliva swabs (Sabre Labs, Capistrano, CA). Cortisol samples were collected at the same time pre and post (10 am) to eliminate variability due to circadian rhythms.

Cravings were assessed before and after a 1-hour module on the use of EFT for this topic. Participants were provided with chocolate and self-assessed their pretest level of craving (11-point SUDS rating scale). EFT was then used for several components of the experience of craving. These included the substance itself, emotions associated with the substance, early childhood experiences involving the substance, times at which craving levels increased, and emotional losses associated with the substance.

EFT Intervention

All EFT instructors were trained and certified in Clinical EFT (EFT Universe, Fulton, CA). EFT was applied with fidelity to the third edition of The EFT Manual.60 Twelve hours of the workshop was devoted to clinical demonstrations, practice sessions, and feedback. EFT was delivered as peer-to-peer coaching, and symptoms assessed without attempting to diagnose or treat mental health conditions. A group delivery method known as “Borrowing Benefits” described in The EFT Manual 60 was used, in which EFT is administered to one individual while the remainder of the group simultaneously self-applies EFT. The settings included residential institutes, nonresidential institutes, hotel meeting rooms, and a university campus. The identical curriculum was used at all 6 workshops. Most were conducted over 4 days. Two were conducted at residential institutes in which the curriculum was delivered over the course of 5 days, with 2 half-days off, but the same number of instruction and practice hours.

Results

Participant scores for happiness, anxiety, depression, PTSD, pain, and cravings were compared before and after treatment using the Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired samples. In order to make the least number of assumptions about the data, it was deemed appropriate to use the nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test rather than t tests. Changes in BP, RHR, cortisol, SigA levels, HRV, and HC in a subsample of participants were also determined using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package version 24.

Between the pre- and posttest time points, participants experienced significant decreases in anxiety, depression, PTSD, pain, and cravings, and a significant increase in happiness (see Table 2). Not all participants completed all assessments at all time points, thus the n available for analysis is shown in the relevant rows of the appropriate tables.

Table 2.

Participant Outcome Measures Pre- Versus Postintervention.

| Scale | Pretest, Mean ± SD | Posttest, Mean ± SD | Change in Mean | Z Statistic | P | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness (n = 170) | 7.28 ± 2.10 | 8.65 ± 1.72 | 1.37 | −8.389 | <.000 | 18.82 |

| Anxiety (n = 170) | 8.35 ± 3.85 | 4.98 ± 3.43 | −3.37 | −9.963 | <.000 | −40.36 |

| Depression (n = 170) | 4.04 ± 3.18 | 2.30 ± 2.28 | −1.74 | −8.282 | <.000 | −43.07 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (n = 158) | 4.74 ± 2.16 | 3.30 ± 1.49 | −1.44 | −7.793 | <.000 | −30.38 |

| Pain (n = 168) | 4.09 ± 2.49 | 1.63 ± 1.89 | −2.46 | −9.325 | <.000 | −60.15 |

| Cravings (n = 164) | 6.47 ± 2.53 | 1.81 ± 1.81 | −4.66 | −10.766 | <.000 | −72.02 |

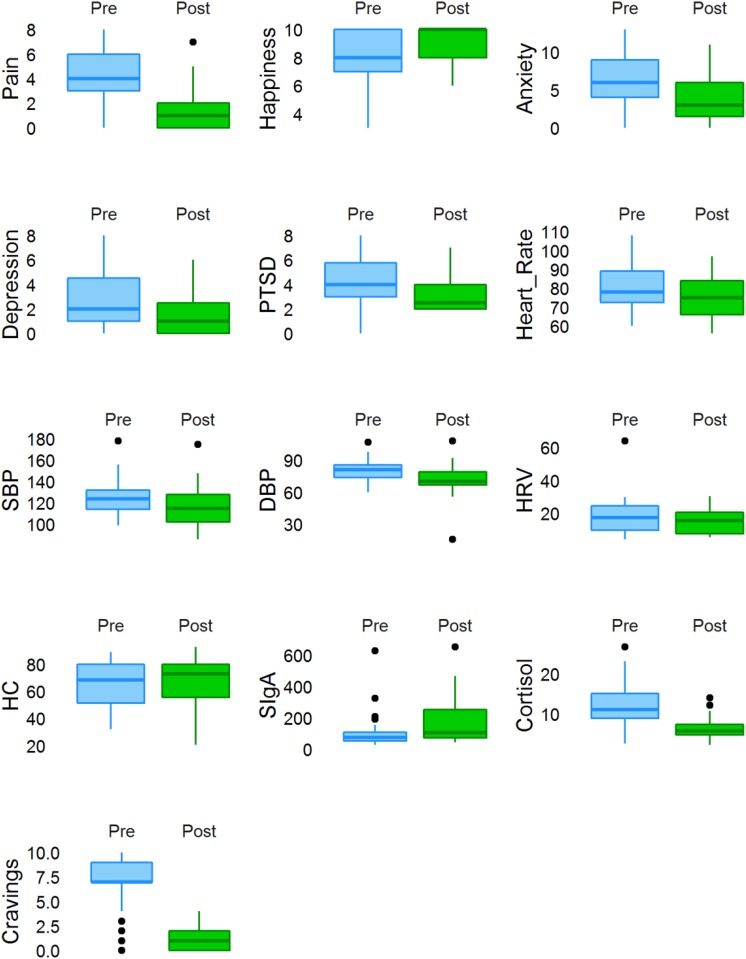

In the subset of participants in whom physiological indicators of health were assessed (n = 31), psychological measurements, including anxiety, depression, PTSD, pain, and cravings all improved. Physiological indicators, including RHR, BP, and cortisol also significantly decreased indicating a functional improvement (see Table 3 and Figure 1). The changes corresponded with an increase in happiness (P = .0004) and immune function in the form of SigA secretion (P = .017). Though not statistically significant, a downward trend was observed for HRV and an upward trend for HC suggesting an improvement in cardiovascular health and ANS function.

Table 3.

Subset of Participants Outcomes Pre- Versus Postintervention (N = 31).

| Scale | Pretest, Mean ± SD | Posttest, Mean ± SD | Change in Mean | Z Statistic | P | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness (n = 29) | 7.9 ± 1.92 | 9.03 ± 1.27 | 1.13 | −2.736 | .006 | 14.30 |

| Anxiety (n = 31) | 6.32 ± 3.89 | 3.84 ± 3.17 | −2.48 | −3.640 | <.000 | −39.24 |

| Depression (n = 31) | 2.68 ± 2.29 | 1.45 ± 1.61 | −1.23 | −2.615 | .009 | −45.89 |

| PTSD (n = 28) | 4.59 ± 2.01 | 3.14 ± 1.46 | −1.45 | −2.934 | .003 | −31.59 |

| Pain (n = 29) | 3.9 ± 2.35 | 1.34 ± 1.69 | −2.56 | −3.856 | <.000 | −65.64 |

| Cravings (n = 25) | 6.72 ± 2.73 | 1.36 ± 1.25 | −5.36 | −4.225 | <.000 | −79.76 |

| Heart rate, beats/min (n = 29) | 80.97 ± 12.04 | 74.59 ± 10.48 | −6.38 | −3.430 | .001 | −7.88 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg (n = 29) | 123.61 ± 16.8 | 116.41 ± 18.46 | −7.2 | −3.376 | .001 | −5.82 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg (n = 29)) | 80.26 ± 9.97 | 73.38 ± 11.18 | −6.88 | −4.124 | <.000 | −8.57 |

| HRV (n = 25) | 16.72 ± 7.58 | 14.54 ± 7.46 | −2.18 | −0.888 | .374 | −13.04 |

| Heart coherence (n = 25) | 65.34 ± 17.55 | 69.75 ± 15.24 | 4.41 | −1.332 | .183 | 6.75 |

| SigA, μg/mL (n = 28) | 112.58 ± 119.37 | 181.73 ± 155.32 | 69.15 | −2.391 | .017 | 61.42 |

| Cortisol, nmol/L (n = 28) | 12.66 ± 5.84 | 6.51 ± 2.81 | −6.15 | −4.213 | <.000 | −48.58 |

Abbreviations: HRV, heart rate variability; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SigA, salivary immunoglobulin A.

Figure 1.

Score changes following treatment in study participants. Outliers within each group are represented by the black dots. DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HC, heart coherence; HRV, heart rate variability; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SigA, salivary immunoglobulin A.

Between the pre and follow-up time points, participants experienced significant decreases in anxiety, depression, PTSD, and pain (see Table 4). All changes were statistically significant with the exception of happiness.

Table 4.

Participant Outcome Measures Pre- Versus Follow-up Intervention.

| Scale | Pretest, Mean ± SD | Follow-up, Mean ± SD | Change in Mean | Z Statistic | P | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness (n = 85) | 7.28 ± 2.10 | 7.70 ± 2.09 | 0.42 | −1.581 | .114 | 5.77 |

| Anxiety (n = 84) | 8.35 ± 3.85 | 5.62 ± 3.74 | −2.73 | −5.276 | <.000 | −32.69 |

| Depression (n = 84) | 4.04 ± 3.18 | 2.78 ± 2.93 | −1.26 | −3.083 | .002 | −31.18 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (n = 72) | 4.74 ± 2.16 | 3.64 ± 1.73 | −1.10 | −4.088 | <.000 | −23.21 |

| Pain (n = 85) | 4.09 ± 2.49 | 2.66 ± 2.26 | −1.43 | −4.681 | <.000 | −34.96 |

Dissimilar results were found between post and follow-up time points, with anxiety and pain found to significantly increase, while happiness decreased significantly (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Participant Outcome Measures Post Versus Follow-up Intervention

| Scale | Posttest, Mean ± SD | Follow-up, Mean ± SD | Change in Mean | Z Statistic | P | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness (n = 89) | 8.65 ± 1.72 | 7.70 ± 2.09 | −0.95 | −4.410 | <.000 | −10.98 |

| Anxiety (n = 84) | 4.98 ± 3.43 | 5.62 ± 3.74 | 0.64 | −3.294 | .001 | 12.85 |

| Depression (n = 84) | 2.30 ± 2.28 | 2.78 ± 2.93 | 0.48 | −1.091 | .275 | 20.87 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (n = 77) | 3.30 ± 1.49 | 3.64 ± 1.73 | 0.34 | −1.662 | .097 | 10.30 |

| Pain (n = 87) | 1.63 ± 1.89 | 2.66 ± 2.26 | 1.03 | −3.790 | <.000 | 63.19 |

The correlations among psychological measures were calculated to determine their interaction (see Table 6). Significant positive correlations were found between pre and post intervention measures of happiness, anxiety, depression, pain, and cravings. Significant negative correlations were found between happiness and all measures except cravings at both time points.

Table 6.

Correlation Between Outcome Measures Pre- Versus Postintervention

| Happiness | Anxiety | Depression | PTSD | Pain | Cravings | Happinessa | Anxietya | Depressiona | PTSDa | Paina | Cravingsa | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness | 1 | −.483* | −.589* | −.392* | −.215* | −.009 | .595* | −.417* | −.499* | −.289* | −.091 | −.047 | .013 |

| Anxiety | −.483* | 1 | .515* | .467* | .372* | .050 | −.282* | .652* | .320* | .398* | .249* | .045 | −.109 |

| Depression | −.589* | .515* | 1 | .396* | .218* | −.106 | −.364* | .318* | .646* | .321* | .055 | .003 | −.033 |

| PTSD | −.392* | .467* | .396* | 1 | .366* | −.029 | −.155 | .250* | .239* | .482* | .133 | −.054 | −.034 |

| Pain | −.215* | .372* | .218* | .366* | 1 | .018 | −.125 | .201* | .037 | .220* | .369* | −.013 | .134 |

| Cravings | −.009 | .050 | −.106 | −.029 | .018 | 1 | .007 | .097 | −.027 | .125 | .019 | .384* | .047 |

| Happinessa | .595* | −.282* | −.364* | −.155 | −.125 | .007 | 1 | −.492* | −.523* | −.348* | −.354* | −.051 | .038 |

| Anxietya | −.417* | .652* | .318* | .250* | .201* | .097 | −.492* | 1 | .559* | .501* | .364* | .022 | −.113 |

| Depressiona | −.499* | .320* | .646* | .239* | .037 | −.027 | −.523* | .559* | 1 | .399* | .246* | .012 | −.057 |

| PTSDa | −.289* | 0.398* | .321* | .482* | .220* | .125 | −.348* | .501* | .399* | 1 | .377* | .002 | −.137 |

| Paina | −.091 | .249* | .055 | .133 | .396* | .019 | −.354* | .364* | .246* | .377* | 1 | −.054 | −.036 |

| Cravingsa | −.047 | .045 | .003 | −.054 | −.013 | .384* | −.051 | .022 | .012 | .002 | −.054 | 1 | −.015 |

| Age | .013 | −.109 | −.033 | −.034 | .134 | .047 | .038 | −.113 | −.057 | −.137 | −.036 | −.015 | 1 |

| Mean | 7.28 | 8.35 | 4.04 | 4.74 | 4.09 | 6.47 | 8.65 | 4.98 | 2.30 | 3.30 | 1.63 | 1.81 | 50.45 |

| SD | 2.098 | 3.853 | 3.178 | 2.16 | 2.489 | 2.534 | 1.715 | 3.427 | 2.279 | 1.49 | 1.889 | 1.807 | 12.346 |

| n | 182 | 179 | 179 | 170 | 182 | 165 | 178 | 176 | 176 | 165 | 175 | 165 | 187 |

Abbreviation: PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

a Postintervention.

*P = .01. **P = .05.

The correlations among psychological and physiological measures in the subset of individuals who completed both assessments (n = 31) were also calculated to determine their interaction (see Table 7). Significant positive correlations were found between pre- and postintervention measures of anxiety and cortisol. Significant negative correlations were found between happiness and anxiety, PTSD, pain at preintervention, and only pain at postintervention.

Table 7.

Subset of Participants Correlation Between Outcome Measures Pre- Versus Postintervention (N = 31).

| Happiness | Anxiety | Depression | PTSD | Pain | Cravings | SigA | Cortisol | Happinessa | Anxietya | Depressiona | PTSDa | Paina | Cravingsa | SigAa | Cortisola | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happiness | 1 | −.516* | −.259 | −.708* | −.476* | −.220 | .151 | .291 | .296 | −.183 | .061 | −.174 | −.489* | .169 | .116 | .025 | −.069 |

| Anxiety | −.516* | 1 | .510* | .647* | .441** | .218 | −.062 | .077 | −.422** | .595* | .199 | .427* | .527* | .084 | −.062 | −.038 | .188 |

| Depression | −.259 | .510* | 1 | .343 | .157 | .048 | −.120 | −.059 | −.089 | .227 | .204 | .288 | −.100 | −.197 | −.022 | −.179 | .026 |

| PTSD | −.708* | .647* | .343 | 1 | .451** | .151 | −.052 | −.076 | −.244 | .287 | .073 | .304 | .298 | −.037 | −.073 | −.087 | −.264 |

| Pain | −.476* | .441** | .157 | .451** | 1 | .218 | .260 | −.056 | −.034 | −.075 | −.368** | −.109 | .227 | .041 | .155 | −.142 | .156 |

| Cravings | −.220 | .218 | .048 | .151 | .218 | 1 | .211 | −.046 | −.249 | .296 | .039 | .302 | .213 | .031 | .469** | .227 | −.008 |

| SigA | .151 | −.062 | −.120 | −.052 | .260 | .211 | 1 | −.073 | .047 | −.143 | −.095 | −.038 | −.179 | .163 | .289 | .326 | −.064 |

| Cortisol | .291 | .077 | −.059 | −.076 | −.056 | −.046 | −.073 | 1 | −.057 | −.072 | .178 | .177 | .000 | .015 | .018 | .381** | −.005 |

| Happinessa | .296 | −.422** | −.089 | −.244 | −.034 | −.249 | .047 | −.057 | 1 | −.626* | −.533* | −.416** | −.704* | .246 | −.034 | −.059 | .156 |

| Anxietya | −.183 | .595* | .227 | .287 | −.075 | .296 | −.143 | −.072 | −.626* | 1 | .596* | .564* | .596* | .073 | .035 | −.085 | −.067 |

| Depressiona | .061 | .199 | .204 | .073 | −.368** | .039 | −.095 | .178 | −.533* | .596* | 1 | .417** | .228 | −.228 | .083 | .021 | −.288 |

| PTSDa | −.174 | .427** | .288 | .304 | −.109 | .302 | −.038 | .177 | −.416** | .564* | .417* | 1 | .350 | .033 | −.120 | .090 | .011 |

| Paina | −.489* | .527* | −.100 | .298 | .227 | .213 | −.179 | .000 | −.704* | .596* | .228 | .350 | 1 | −.007 | −.036 | .007 | .308 |

| Cravingsa | .169 | .084 | −.197 | −.037 | .041 | .031 | .163 | .015 | .246 | .073 | −.228 | .033 | −.007 | 1 | .223 | .050 | .211 |

| SigAa | .116 | −.062 | −.022 | −.073 | .155 | .469** | .289 | .018 | −.034 | .035 | .083 | −.120 | −.036 | .223 | 1 | .237 | .221 |

| Cortisola | .025 | −.038 | −.179 | −.087 | −.142 | .227 | .326 | .381** | −.059 | −.085 | .021 | .090 | .007 | .050 | .237 | 1 | .149 |

| Age | −.069 | .188 | .026 | −.264 | .156 | −.008 | −.064 | −.005 | .156 | −.067 | −.288 | .011 | .308 | .211 | .221 | .149 | 1 |

| Mean | 7.9 | 6.32 | 2.68 | 4.59 | 3.9 | 6.72 | 112.58 | 12.66 | 9.03 | 3.84 | 1.45 | 3.14 | 1.34 | 1.36 | 181.73 | 6.51 | 52.88 |

| SD | 1.92 | 3.89 | 2.29 | 2.01 | 2.35 | 2.73 | 119.37 | 5.84 | 1.27 | 3.17 | 1.61 | 1.46 | 1.69 | 1.25 | 155.32 | 2.81 | 16.05 |

| n | 30 | 31 | 31 | 29 | 30 | 25 | 28 | 28 | 29 | 31 | 31 | 28 | 29 | 25 | 28 | 28 | 26 |

Abbreviations: PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SigA, salivary immunoglobulin A.

a Postintervention.

*P = .01. **P = .05.

Discussion

This study adds to the evidence base for EFT as an effective mental health intervention, as has been demonstrated in many previous studies. It also suggests that EFT simultaneously improves a broad range of health markers across multiple physiological systems. As hypothesized, participants experienced significant decreases in pain, anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Physiological indicators of health such as RHR, BP, and cortisol also significantly decreased, indicating improvement. Happiness levels increased as did immune system function.

The current research findings of each of the physiological measures has potential and far-reaching health consequences. Decreases in cortisol have been associated with a wide spectrum of positive health effects, including increased muscle mass, increased bone density, improved skin elasticity, enhancement of cognitive function especially learning and attention, and enhanced cell signaling61 This was the first study to assess SigA, HRV, HC, BP, and RHR after EFT treatment. The results are consistent with previous research demonstrating improvements in endocrinal and genetic regulation.10,42,46

The 74% reduction in cravings (P < .000) is typical of that found in other EFT research.18,11,13,62 While not statistically significant, the trends toward improvement in HRV and HC allude to possible improvements in cardiovascular health and ANS function. A power analysis was performed, and it was determined that detection of a medium effect size change for HC and HRV at a significance level of .05 and 90% power would require a minimum of 44 participants.

The improvements found in RHR and BP were clinically as well as statistically significant. If these were available to hospital patients as well as therapy group participants, medical services utilizations would be reduced. The savings in terms of financial cost and human suffering would be substantial. For example, outpatient psychotherapy has been shown to be effective in terms of symptom reduction and the improvement of quality of life, and to decrease work disability days, hospitalization days, and inpatient costs.63 A meta-analysis of 91 studies, which examined a range of psychological treatments (various forms of psychotherapy, behavioral medicine, and psychiatric consultation), found the average savings resulting from using psychological interventions was estimated to be about 20%.64 The review also reported that even when the cost of providing the psychological intervention was subtracted, it was still this substantial saving. Clearly, there is something to be gained from including psychological interventions.

While the psychological improvements produced by EFT have been extensively studied (eg, large effect sizes for EFT in the treatment of anxiety [Clond],30 depression [Nelms & Castel],31 and PTSD [Sebastian & Nelms]), the extension of research into their physiological dimensions is relatively new. When approaches such as EFT are noninvasive, nonpharmaceutical, and free of negative side effects are resulting in such profound changes for a person, they may demand further consideration as frontline medical interventions. Users report Clinical EFT can be learned quickly and applied easily, and is well-tolerated in heterogeneous populations, makes a simple nondrug therapy available to a large population. Its use in and outside clinical settings as a safe and reliable method for reducing distress,7 and for a wide range of psychological and physical symptoms, makes it a useful strategy to add to existing protocols. The profound physiological changes that also occur with this technique, is establishing EFT as safe and effective with a variety of populations and conditions.

Limitations

Despite the positive results, the study had a number of limitations. One was the absence of a control or comparison group. Others included reliance on self-report for psychological measures, the low number of participants who completed follow-up assessments (89 out of 203) and the use of relatively brief assessments. The effects obtained could have been partially due to nonspecifics present in any therapy, to the supportive nature of the group, to demand characteristics, or to sympathetic attention. Completers of the follow-up assessments (44%) might not have been representative of the sample as a whole. Because of the small sample size, statistical significance was not obtained for HC or HRV. The reliable measurement of HRV is also in its infancy and requires further validation to be considered a sound procedure.

Further research should also randomize participants between EFT and an active control treatment such as CBT and include at least 44 persons per group in order to identify statistically significant changes in all physiological markers. EFTs epigenetic effects could be further explored with use of salivary gene assays such as were used in Maharaj46 and similar studies. A larger battery of psychological assessments could be used, and a second follow-up data point included to determine trends over time.

Despite these limitations, this study points to the multidimensional physiological effects of EFT as well as its utility for improving emotional health when delivered in group format. Group therapy is efficient and cost-effective, and similar results were found when different trainers taught Clinical EFT, showing that the improvements measured were not due to the unique gifts of a particular therapist.

Conclusions

Reviews and meta-analyses of EFT demonstrate that it is an evidence-based practice7,44 and that its efficacy for anxiety, depression, phobias and PTSD is well-established. The research investigating physiological improvements after EFT intervention is limited; however, this study adds to the body of literature and suggests that EFT is associated with multidimensional improvements across a spectrum of physiological systems.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: DB and GG collected the data. RS and KB analyzed the data. PS and DC wrote the article with the assistance of RS.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: All authors except RS may occasionally derive income from trainings, clinical services, and workshops in the approach examined in this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Peta Stapleton  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9916-7481

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9916-7481

Dawson Church  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7324-3140

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7324-3140

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1. Katon W, Lin EH, Kroenke K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1329–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Church D. Clinical EFT as an evidence-based practice for the treatment of psychological and physiological conditions. Psychology. 2013. a;4:645–654. doi:10.4236/psych.2013.48092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feinstein D. Acupoint stimulation in treating psychological disorders: evidence of efficacy. Rev Gen Psychol. 2012;16:364–380. doi:10.1037/a0028602 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Church D, De Asis MA, Brooks AJ. Brief group intervention using Emotional Freedom Techniques for depression in college students: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Res Treat. 2012;2012:257172 doi:10.1155/2012/257172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Church D, Hawk C, Brooks AJ, et al. Psychological trauma symptom improvement in veterans using emotional freedom techniques: a randomized controlled trial. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201:153–160. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827f6351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Geronilla L, Minewiser L, Mollon P, McWilliams M, Clond M. EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) remediates PTSD and psychological symptoms in veterans: a randomized controlled replication trial. Energy Psychol Theory Res Treat. 2016;8:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bougea AM, Spandideas N, Alexopoulos EC, Thomaides T, Chrousos GP, Darviri C. Effect of the Emotional Freedom Technique on perceived stress, quality of life, and cortisol salivary levels in tension-type headache sufferers: a randomized controlled trial. Explore (NY). 2013;9:91–99. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Church D, Nelms J. Pain, range of motion, and psychological symptoms in a population with frozen shoulder: a randomized controlled dismantling study of clinical EFT (emotional freedom techniques). Arch Sci Psychol. 2016;4:38–48. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stapleton P, Bannatyne AJ, Urzi KC, Porter B, Sheldon T. Food for thought: a randomised controlled trial of emotional freedom techniques and cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of food cravings. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2016;8:232–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stapleton P, Church D, Sheldon T, Porter B, Carlopio C. Depression symptoms improve after successful weight loss with emotional freedom techniques. ISRN Psychiatry. 2013;2013:573532 doi:10.1155/2013/573532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stapleton P, Sheldon T, Porter B. Clinical benefits of Emotional Freedom Techniques on food cravings at 12-months follow-up: a randomized controlled trial. Energy Psychol Theory Res Treat. 2012;4:13–24. doi:10.9769/EPJ.2012.4.1.PS [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karatzias T, Power K, Brown K, et al. A controlled comparison of the effectiveness and efficiency of two psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder: eye movement desensitization and reprocessing vs. emotional freedom techniques. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boath E, Stewart T, Rolling C. The impact of EFT and matrix reimprinting on the civilian survivors of war in Bosnia: a pilot study. Curr Res Psychol. 2014;5:64–72. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Church D. The effect of EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) on athletic performance: a randomized controlled blind trial. Open Sports Sci J. 2009;2:94–99. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Llewellyn-Edwards T, Llewellyn-Edwards M. The effect of Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) on soccer performance. Fidelity. 2012;47:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Church D, Brooks AJ. The effect of a brief EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) self-intervention on anxiety, depression, pain and cravings in healthcare workers. Integr Med Clin J. 2010;9(5):40–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gaesser A. H., Karan O. C. A randomized controlled comparison of Emotional Freedom Technique and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy to reduce adolescent anxiety: A pilot study. J Alt Comp Medicine. 2017;23(2):102–108. doi:10.1089/acm.2015.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baker BS, Hoffman CJ. Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) to reduce the side effects associated with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitor use in women with breast cancer: a service evaluation. Eur J Integr Med. 2015;7:136–142. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wells S, Polglase K, Andrews HB, Carrington P, Baker AH. Evaluation of a meridian-based intervention, Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT), for reducing specific phobias of small animals. J Clin Psychol. 2003;59:943–966. doi:10.1002/jclp.10189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baker AH, Siegel MA. Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) reduces intense fears: a partial replication and extension of Wells, Polglase, Andrews, Carrington, & Baker (2003). Energy Psychol Theory Res Treat. 2010;2:13–30. doi:10.9769/EPJ.2010.2.2.AHB [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salas MM, Brooks AJ, Rowe JE. The immediate effect of a brief energy psychology intervention (Emotional Freedom Techniques) on specific phobias: a pilot study. Explore (NY). 2011;7:155–161. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Craig G, Fowlie A. Emotional Freedom Techniques: The Manual. Sea Ranch, CA: Authors; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wolpe J. The Practice of Behavior Therapy. 2nd ed New York, NY: Pergamon Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Andrade J, Feinstein D. Energy psychology: theory, indications and evidence In: Feinstein D, Gallo F, Eden D, eds. Energy Psychology Interactive: Rapid Interventions for Lasting Change. Ashland, OR: Innersource; 2004:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chatwin H, Stapleton P, Porter B, Devine S, Sheldon T. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy and emotional freedom techniques in reducing depression and anxiety among adults: a pilot study. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2016;15(2):27–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gaesser AH. Interventions to Reduce Anxiety for Gifted Children and Adolescents. Doctoral Dissertations, Paper 377 2014. http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/377. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nemiro A, Papworth S. Efficacy of two evidence-based therapies, Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for the treatment of gender violence in the Congo: a randomized controlled trial. Energy Psychol Theory Res Treat. 2015;7(2):13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clond M. Emotional freedom techniques for anxiety: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204:388–395. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nelms J, Castel D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized trials of Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) for the treatment of depression. Explore (NY). 2016;12:416–426. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Church D, Brooks AJ. CAM and energy psychology techniques remediate PTSD symptoms in veterans and spouses. Explore (NY). 2014;10:24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kalla M, Simmons M, Robinson A, Stapleton P. Emotional freedom techniques (EFT) as a practice for supporting chronic disease healthcare: a practitioners’ perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:1654–1662. doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1306125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brattberg G. Self-administered EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) in individuals with fibromyalgia: a randomized trial. Integr Med. 2008;7:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hodge PM, Jurgens CY. A pilot study of the effects of Emotional Freedom Techniques in psoriasis. Energy Psychol Theory Res Treat. 2011;3:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Babamahmoodi A, Arefnasab Z, Noorbala AA, et al. Emotional freedom technique (EFT) effects on psychoimmunological factors of chemically pulmonary injured veterans. Iran Journal of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunological Disorders. 2015;14(1):37–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ortner N, Palmer-Hoffman J, Clond M. Effects of Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) on the reduction of chronic pain in adults: a pilot study. Energy Psychol Theory Res Treat. 2014;6(2). doi:10.9769/EPJ.2014.11.2.NO.JH.MC [Google Scholar]

- 38. Church D, Sparks T, Clond M. EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) and resiliency in veterans at risk for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. Explor J Sci Heal. 2016;12:355–365. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee JH, Chung SY, Kim JW. A comparison of Emotional Freedom Techniques-Insomnia (EFT-I) and Sleep Hygiene Education (SHE) for insomnia in a geriatric population: a randomized controlled trial. Energy Psychol. 2015;7:22–29. doi:10.9769/EPJ.2015.07.01.JL [Google Scholar]

- 40. Swingle PG, Pulos L, Swingle MK. Neurophysiological indicators of EFT treatment of posttraumatic stress. Subtle Energies Energy Medicine. 2004;15:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Church D, Downs D. Sports confidence and critical incident intensity after a brief application of Emotional Freedom Techniques: a pilot study. Sport J. 2012;15. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Church D, Yount G, Brooks AJ. The effect of emotional freedom techniques on stress biochemistry: a randomized controlled trial. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200:891–896. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e31826b9fc1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Church D, Geronilla L, Dinter I. Psychological symptom change in veterans after six sessions of EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques): an observational study. Int J Healing Caring. 2009;9:1. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Church D, Feinstein D, Palmer-Hoffman J, Stein PK, Tranguch A. Empirically supported psychological treatments: the challenge of evaluating clinical innovations. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:699–709. doi:10.1097/nmd.0000000000000188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Church D, Yount G, Rachlin K, Fox L, Nelms J. Epigenetic effects of PTSD remediation in veterans using clinical emotional freedom techniques: a randomized controlled pilot study. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32:112–122. doi:10.1177/0890117116661154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maharaj ME. Differential gene expression after Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) treatment: a novel pilot protocol for salivary mRNA assessment. Energy Psychol Theory Res Treat. 2016;8(1):17–32. doi:10.9769/EPJ.2016.8.1.MM [Google Scholar]

- 47. Palmer-Hoffman J, Brooks AJ. Psychological symptom change after group application of Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT). Energy Psychol. 2011;3:33–38. doi:10.9769.EPJ.2011.3.1.JPH [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boath E, Carryer A, Stewart A. Is Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) generalizable? Comparing effects in sport science students versus complementary therapy students. Energy Psychol. 2013;5:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stapleton P, Roos T, Mackintosh G, Sparenburg E, Carter B. Online delivery of emotional freedom techniques for food cravings and weight management. J Psychosom Res. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Waite LW, Holder MD. Assessment of the emotional freedom technique: an alternative treatment for fear. Sci Rev Ment Health Pract. 2003;2:20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fox L. Is acupoint tapping an active ingredient or an inert placebo in emotional freedom techniques (EFT)? A randomized controlled dismantling study. Energy Psychol Theory Res Treat. 2013;5:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rogers R, Sears SR. Emotional Freedom Techniques for stress in students: a randomized controlled dismantling study. Energy Psychol Theory Res Treat. 2015;7:26–32. doi:10.9769/EPJ.2015.11.1.RR [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reynolds AE. Is acupoint stimulation an active ingredient in Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT)? A controlled trial of teacher burnout. Energy Psychol Theory Res Treat. 2015;7:14–21. doi:10.9769/EPJ.2015.07.01.AR [Google Scholar]

- 54. Church D, Stapleton P, Yang A, Gallo F. Is tapping on acupuncture points an active ingredient in emotional freedom techniques (EFT)? A review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206:783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McCraty R, Atkinson M, Lipsenthal L, Arguelles L. New hope for correctional officers: an innovative program for reducing stress and health risks. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2009;34:251–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Abdel-Khalek A. Measuring happiness with a single-item scale. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal. 2006;34:139–150. doi:10.2224/sbp.2006.34.2.139 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Matheson LN, Melhorn JM, Mayer TG, Theodore BR, Gatchel RJ. Reliability of a visual analog version of the QuickDASH. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2006;88:1782–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lang AJ, Wilkins K, Roy-Byrne PP, et al. Abbreviated PTSD Checklist (PCL) as a guide to clinical response. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2012;34:332–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Church D. The EFT Manual. 3rd ed Santa Rosa, CA: Energy Psychology Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Church D. The Genie in Your Genes: Epigenetic Medicine and the New Biology of Intention. Santa Rosa, CA: Energy Psychology Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Stapleton P, Stewart M. Comparison of the effectiveness of two modalities of group delivery of emotional freedom technique (EFT) intervention for food cravings: Online versus in-person. paper under review; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Altmann U, Zimmermann A, Kirchmann HA, et al. Outpatient psychotherapy reduces health-care costs: a study of 22,294 insurants over 5 years. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:98 doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chiles J, Lambert M, Hatch A. The impact of psychological interventions on medical cost offset: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol. 2006;6:204–220. doi:10.1093/clipsy.6.2.204 [Google Scholar]