Short abstract

Objective

To compare the efficacy, safety, and pregnancy outcomes of tamoxifen plus ovarian function suppression (OFS) between Han and Zhuang women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

Methods

A total of 236 Han and 101 Zhuang women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer who received tamoxifen plus OFS were analyzed retrospectively. Long-term disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were evaluated by Kaplan–Meier analysis, and adverse events and pregnancy outcomes were assessed by χ2 and Fisher’s exact-probability tests.

Results

There was no significant difference in DFS or OS between Han and Zhuang women (5-year DFS 74.57% and 77.23%, OS 85.59% and 90.01%, respectively). The incidences of endometrial hyperplasia, ovarian cysts, nausea and vomiting, fatty liver, retinitis, and thrombocytopenic purpura were similar in both groups, but Zhuang women had significantly more allergic reactions (6.93% vs. 2.12%). Pregnancy rates among women who attempted pregnancy were similar (Han, 7/138, 5.07%; Zhuang, 2/46, 4.35%).

Conclusions

OFS plus tamoxifen resulted in similar DFS and OS among premenopausal Han and Zhuang women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. However, Zhuang women were more likely to experience an allergic reaction. For women with fertility concerns, OFS plus tamoxifen was associated with similar pregnancy rates in Zhuang and Han women.

Keywords: Efficacy, adverse event, pregnancy, breast cancer, tamoxifen, ovarian function suppression

Introduction

Recent studies have shown that breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women and is associated with poor survival, particularly among premenopausal women.1 It is therefore important to investigate novel and effective therapeutic treatments for breast cancer.2 Comprehensive therapy currently consists of surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy as mainstream modalities.3 Although adjuvant oral tamoxifen is one of the most effective hormone therapies in hormone receptor-positive premenopausal breast cancer patients,4 fertility concerns remain an important factor affecting treatment strategies in young breast cancer patients.5

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2014 guidelines suggested that tamoxifen alone should be used for an initial 5-year period in premenopausal patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer,6 and a meta-analysis of the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group demonstrated that 5 years of tamoxifen treatment was correlated with a significant reduction in breast cancer mortality.7

Loss of ovarian function and fertility constitute severe side effects of breast cancer treatment protocols, particularly chemotherapy.5 Ovarian function suppression (OFS) has been developed as a suitable strategy to protect ovarian function during chemotherapy, and accumulating evidence suggests that tamoxifen plus OFS results in better survival than tamoxifen alone.8–10 In 2003, the International Breast Cancer Study Group initiated the SOFT trial to determine the value of adding OFS to tamoxifen, and the role of the aromatase inhibitor exemestane plus OFS in hormone receptor-positive premenopausal breast cancer patients, compared with tamoxifen alone.11 The results of the SOFT trial suggested that the addition of OFS to tamoxifen was not beneficial in women with low-risk early-stage breast cancer, but did improve outcomes in women at higher risk of relapse who received adjuvant chemotherapy, but who had no treatment-induced amenorrhea.12 Similar results were observed in the E-3193, INT-0142 trials.13

The SOFT trial is currently the largest study of its kind to investigate the effects of tamoxifen plus OFS, and its results have been accepted worldwide.14 However, the SOFT trial did not investigate correlations between tamoxifen or OFS plus tamoxifen and pregnancy outcomes in patients. According to ASCO and European Society for Medical Oncology guidelines, cryopreservation of oocytes or embryos is a suitable procedure for fertility preservation in cancer patients.15,16 Lambertin17 and colleagues demonstrated that OFS exerted no effect on pregnancy in breast cancer patients; however, the effects of tamoxifen and OFS on pregnancy outcomes remain controversial.

Most recent large and authoritative clinical trials have enrolled few Chinese women, particularly from minority populations, and the efficacy, safety, and pregnancy outcomes following OFS plus tamoxifen in premenopausal Han Chinese women with hormone receptor-positive early breast cancer compared with women from minority Chinese populations are thus unknown. In addition, there are presently no research reports comparing these indices between Han and Zhuang populations in southern China. We therefore designed the present clinical study to explore such issues.

Patients and methods

Ethics statement

The study protocols were approved by the ethics committees of the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Guangxi Medical University. All participants in this clinical research study were informed about the goals of the study before being enrolled, and written informed consent was obtained for the storage of patient information in our hospital database.

Patients

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records of patients diagnosed with breast cancer who were included in a prospective database of the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Guangxi Medical University from January 2007 to December 2010. Study participants underwent either mastectomy, modified radical surgery, or breast-conserving surgery followed by radiotherapy. The use of chemotherapy was based on pathologic TNM stage and molecular subtype. Patients who received chemotherapy and remained premenopausal were also included within 8 months of completing chemotherapy, once estradiol (E2) concentrations had been assessed by a local laboratory.12 The standard criteria for menopause were: age ≥60 years; having undergone bilateral ovariectomy; age <60 years, but with natural menopause for ≥12 months, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and E2 levels in the menopausal range, and without chemotherapy, tamoxifen, or OFS; and age <60 years, but having undergone tamoxifen therapy, with FSH and E2 levels in the menopausal range. The same samples were subjected to repeat analysis in the laboratory to confirm the levels. Menopausal patients were then excluded.4,6

Breast cancer patients who underwent their initial treatment at other centers, as well as patients who were postmenopausal, hormone receptor-negative, or who belonged to minorities other than Zhuang, and patients unwilling to receive tamoxifen treatment for personal reasons were also excluded.

Treatment and follow-up

All patients received an oral dose of 20 mg of tamoxifen daily. OFS was achieved voluntarily by either subcutaneous injection of leuprorelin 3.75 mg every 28 days or by bilateral oophorectomy.

After systemic treatment with surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy, all patients underwent regular follow-up involving analysis of serum tumor marker levels, breast and abdominal ultrasonography, and chest radiography every 2–3 months for the first year after systemic treatment, every 6 months for the subsequent 5 years, and every 12 months thereafter. Investigation of breast tissue by magnetic resonance imaging and molybdenum target X-ray, evaluation of head, chest, and abdominal and pelvic cavities by computed tomography, isotopic bone scan, and curettage were carried out once a year.

All adverse events were recorded according to the results of follow-up. Pregnancy was evaluated during follow-up, and “no pregnancy” was defined as either pregnancy not desired or failed attempts. Patients who reported a term or preterm delivery, miscarriage, and/or induced abortion were considered as having undergone a pregnancy.17

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was disease-free survival (DFS), defined as the time from enrollment to the first recurrence of invasive breast cancer (regional, local, or distant), the appearance of contralateral breast cancer, a second primary invasive cancer (non-breast), or death without recurrence. The secondary endpoint was overall survival (OS), defined as the time from enrollment to death from any cause or the end of follow-up.

Statistical analysis

We compared clinical and pathologic characteristics, treatment efficacy and safety, and pregnancy outcomes between Han and Zhuang women using χ2 tests, or Fisher’s exact test if the value in a statistical cell was expected to be < 6. Differences between continuous data were analyzed by t-tests. Survival was analyzed by Kaplan–Meier analysis, and group results were compared using log-rank tests. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

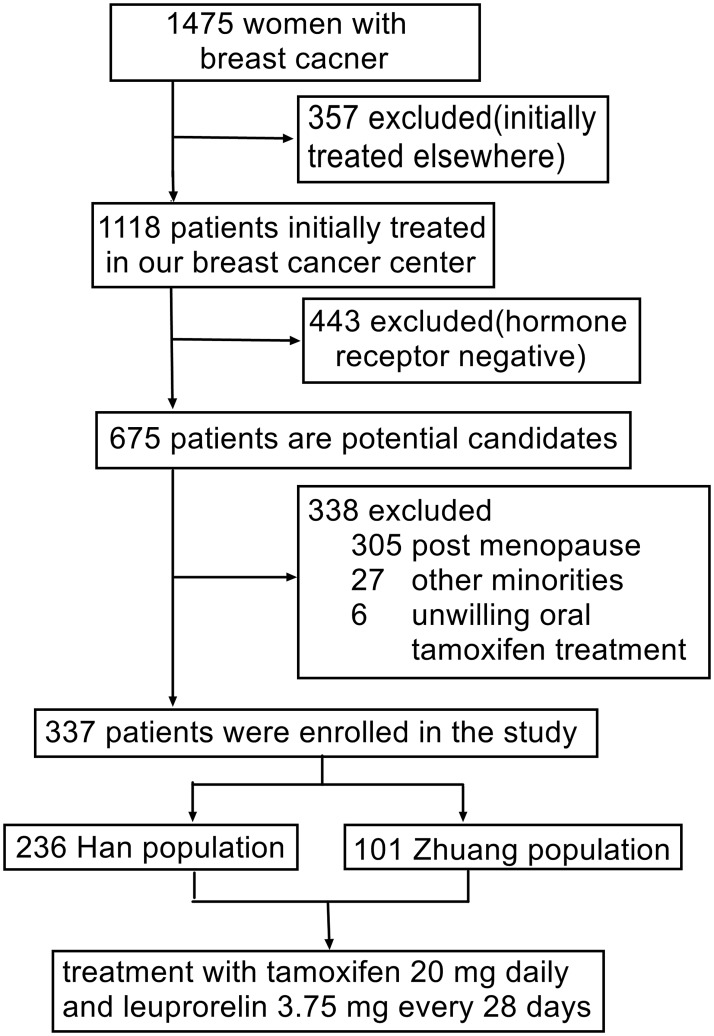

A total of 1475 southern Chinese women with early breast cancer were entered consecutively into the database during the study period. Among these, 357 (24.2%) women who underwent their initial breast cancer therapy at other centers, 443 (30.0%) with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer, 305 (20.7%) postmenopausal women, 27 (1.8%) women from minorities other than Han or Zhuang, and six (0.4%) patients who were unwilling to receive tamoxifen treatment for personal reasons were excluded. The remaining 337 patients (22.8%) were then included in the present study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of study patients.

Among the final cohort of 337 women, 236 were ethnic Han and 101 were ethnic Zhuang. All received oral tamoxifen 20 mg daily and a subcutaneous injection of leuprorelin 3.75 mg every 28 days (Figure 1).

Clinicopathologic data

The clinicopathologic and demographic data of the 337 enrolled patients are summarized in Table 1. Most clinicopathologic features were similar in both population groups at baseline (Table 1), with no significant difference in age, tumor invasion depth, number of metastatic lymph nodes, estrogen receptor status, progesterone receptor status, HER-2 status, or pathological type (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinicopathological characteristics between Han and Zhuang women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

| Variable | Total(n = 337) | Han(n = 236) | Zhuang(n = 101) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.179 | ||||

| Median (range) | 41 (26–50) | 44 (31–52) | |||

| Tumor invasion depth | 0.020 | 0.990 | |||

| ≤2 cm | 72 | 50 | 22 | ||

| >2 cm, ≤5 cm | 241 | 169 | 72 | ||

| >5 cm | 24 | 17 | 7 | ||

| No. of lymph nodes | 1.309 | 0.520 | |||

| 0 | 16 | 10 | 6 | ||

| 1–3 | 185 | 134 | 51 | ||

| ≥4 | 136 | 92 | 44 | ||

| ER status | 0.958 | 0.328 | |||

| Negative | 29 | 18 | 11 | ||

| Positive | 308 | 218 | 90 | ||

| PR status | 0.125 | 0.724 | |||

| Negative | 26 | 19 | 7 | ||

| Positive | 311 | 217 | 94 | ||

| HER-2 status | 0.763 | 0.383 | |||

| Negative | 267 | 184 | 83 | ||

| Positive | 70 | 52 | 18 | ||

| Pathological type | 4.578 | 0.101 | |||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 185 | 138 | 47 | ||

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 90 | 60 | 30 | ||

| Other | 62 | 38 | 24 |

HER-2 positive indicates positive for HER-2 by fluorescence in situ hybridization or chromogenic in situ hybridization test or (+++) in immunohistochemistry test according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines 2011. Positivity for ER and PR defined according to American Society of Clinical Oncology and College of American Pathologists 2010 guidelines, which recommended positivity criteria for ER and PR as ≥1% of positive nuclear staining.

HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; PR, progesterone receptor; ER, estrogen receptor.

Efficacy and survival

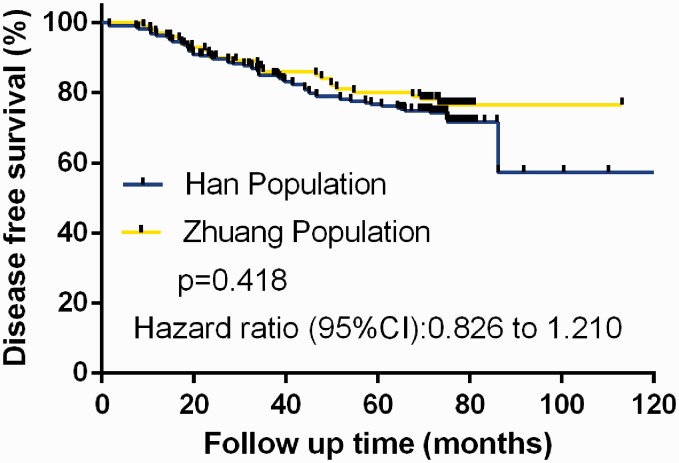

DFS was compared between the two groups using Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test. There was no significant difference between the ethnic groups in terms of DFS (Figure 2). Among the 83 DFS events analyzed, Han women accounted for 60 events and Zhuang women for 23. The estimated 5-year DFS rates were 74.57% (95% confidence interval [CI], 65.87–86.23%) for Han versus 77.23% (95% CI, 67.08–89.46%) for Zhuang women. Neither population attained the median DFS.

Figure 2.

Comparison of disease-free survival between Han (n=236) and Zhuang women (n=101) with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer treated with oral tamoxifen 20 mg daily and ovarian function suppression with subcutaneous injection of leuprorelin 3.75 mg every 28 days.

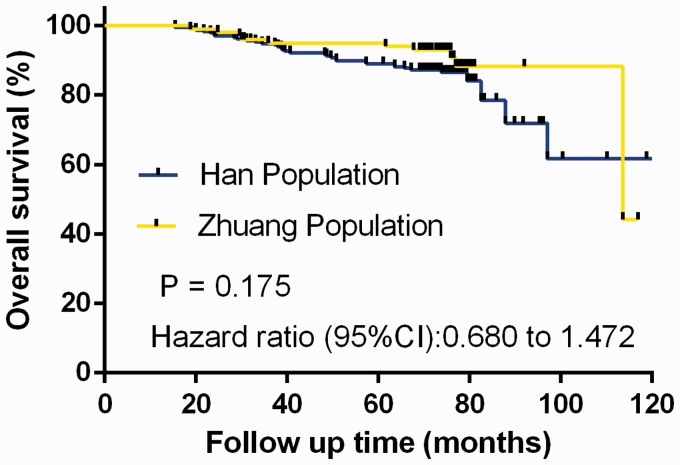

Similar to DFS, there was no significant difference between the groups in terms of OS, as demonstrated by Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank test (Figure 3). In the final analysis, 34 (14.4%) deaths were observed in the Han population versus 10 (9.90%) in the Zhuang population. The median OS for Han women was 113.63 months, but the median was not reached in the Zhuang population. The 5-year estimated OS rates for the Han and Zhuang populations were 85.59% (95% CI, 80.03–91.26%) and 90.01% (95% CI, 85.87–94.51%), respectively.

Figure 3.

Comparison of overall survival between Han (n=236) and Zhuang women (n=101) with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer treated with oral tamoxifen 20 mg daily and ovarian function suppression with subcutaneous injection of leuprorelin 3.75 mg every 28 days.

Safety

We investigated the safety profiles and adverse events in the two populations. The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were endometrial hyperplasia (simple hyperplasia and atypical hyperplasia),18–20 ovarian cysts,21 nausea and vomiting,22 fatty liver,23 retinitis,24,25 thrombocytopenic purpura,26 and allergy,27 as reported previously. We found no significant differences between the Han and Zhuang populations in terms of non-endometrial hyperplasia (31.78% vs. 32.67%), ovarian cysts (17.38% vs. 13.86%), nausea and vomiting (3.39% vs. 1.98%), fatty liver (16.95% vs. 17.82%), retinitis (6.36% vs. 3.96%), or thrombocytopenic purpura (6.36% vs. 8.91%) (Table 2). However, the Zhuang population exhibited a significantly higher rate of allergic events (6.93%) compared with the Han population (2.12%) (P = 0.048) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Occurrence of grade 3 or 4 adverse events in Han and Zhuang women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen plus ovarian function suppression.

| Adverse event, n (%) | Total(n = 337) | Han(n = 236) | Zhuang(n = 101) | χ2 | P-value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 0.026 | 0.872 | 0.960 | 0.583–1.579 | |||

| Yes | 108 (32.05) | 75 (31.78) | 33 (32.67) | ||||

| No | 229 (67.95) | 161 (66.82) | 68 (67.33) | ||||

| Ovarian cyst | 0.639 | 0.424 | 1.307 | 0.677–2.521 | |||

| Yes | 55 (16.32) | 41 (17.38) | 14 (13.86) | ||||

| No | 282 (83.68) | 195 (82.62) | 87 (86.14) | ||||

| Nausea and vomiting | 0.488 | 0.729 | 1.737 | 0.362–8.326 | |||

| Yes | 10 (2.97) | 8 (3.39) | 2 (1.98) | ||||

| No | 327 (97.03) | 228 (96.61) | 99 (98.02) | ||||

| Fatty liver | 0.038 | 0.846 | 0.941 | 0.510–1.737 | |||

| Yes | 58 (17.21) | 40 (16.95) | 18 (17.82) | ||||

| No | 279 (82.79) | 196 (83.05) | 83 (82.18) | ||||

| Retinitis | 0.763 | 0.451 | 0.549 | 0.144–2.088 | |||

| Yes | 19 (5.64) | 15 (6.36) | 4 (3.96) | ||||

| No | 318 (94.36) | 221 (93.64) | 97 (96.04) | ||||

| Thrombocytopenic purpura | 0.698 | 0.403 | 1.646 | 0.532–5.088 | |||

| Yes | 23 (6.82) | 15 (6.36) | 9 (8.91) | ||||

| No | 313 (93.18) | 221 (93.64) | 92 (91.09) | ||||

| Allergy | 4.769 | 0.048 | 0.291 | 0.090–0.939 | |||

| Yes | 12 (3.56) | 5 (2.12) | 7 (6.93) | ||||

| No | 325 (96.44) | 231 (97.88) | 94 (93.07) | ||||

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Pregnancy

We also investigated the incidences of pregnancy in both ethnic groups, excluding 98 (41.52%) Han and 55 Zhuang women (54.46%) who did not attempt pregnancy. Among the remaining participants, the pregnancy rates were similar in the two groups, with seven pregnancies (5.07%) among 138 Han women and two (4.35%) among 46 Zhuang women (Table 3). No congenital abnormalities or preterm deliveries occurred among the nine offspring.

Table 3.

Pregnancy rates in Han and Zhuang women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen plus ovarian function suppression.

| Pregnancy occurrence, n (%) | Total(n = 184) | Han(n = 138) | Zhuang(n = 46) | χ2 | P-value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy | 9 (4.89) | 7 (5.07) | 2 (4.35) | 0.039 | >0.95 | 0.851 | 0.170–4.248 |

| No pregnancy | 175 (95.11%) | 131 (94.93) | 44 (95.65) |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

China’s population includes 56 ethnic groups, with Han individuals constituting 96% of the population and the autonomous region of Guangxi Province in southern China having the largest Zhuang population. Increasing evidence has shown oncogenic variations among different minorities in China that may be associated with differences in cancer morbidities;28 however, there has been scant research comparing health outcomes among different populations undergoing the same treatment modalities. We therefore compared health issues between different ethnic groups, on the basis of the identity cards presented by the patients at their first hospital attendance.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study represents one of the largest studies to investigate the efficacy and safety of adjuvant tamoxifen plus OFS in Han and Zhuang women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer living in southern China. The results demonstrated that DFS and OS rates were similar in women from both ethnic groups following treatment with tamoxifen and OFS. The rates of adverse events were also similar, except for allergic reactions, which were more common among Zhuang women. Furthermore, the current results provide the first evidence indicating similar pregnancy rates in the two groups after treatment.

For more than two decades, endocrine therapy for breast cancer has included tamoxifen, letrozole, anastrozole, and exemestane, all of which have made significant contributions to breast cancer therapy.29–31 Large clinical trials have focused on investigating and comparing the efficacies of each endocrine drug. SOFT and TEXT clinical trials demonstrated that exemestane plus OFS and tamoxifen plus OFS exhibited better outcomes than tamoxifen alone in breast cancer patients with a high composite risk.32,33 The ABCSG-12 clinical trial compared tamoxifen plus goserelin with anastrozole plus goserelin for > 3 years and showed that, although OS was higher with tamoxifen compared with anastrozole, there was no significant difference in DFS between the two treatment arms.34 Most large clinical trials have not considered the effects of ethnicities or minority participants. However, we accordingly compared the treatment effects of OFS plus tamoxifen in Han and Zhuang cohorts in southern China. The 5-year DFS survival rates were similar in both ethnic groups (74.57% in Han and 77.23% in Zhuang), indicating that OFS plus tamoxifen provided similar therapeutic efficacies with respect to preventing recurrence in both populations. A similar phenomenon was observed for OS (85.59% in Han and 90.01% in Zhuang). Guangxi is a Zhuang autonomous region in southern China and home to millions of Zhuang residents.35 The results of the current study indicated similar long-term outcomes in Han and Zhuang patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer treated with OFS plus tamoxifen, suggesting that Zhuan ethnicity is not a critical factor influencing survival, and the same endocrine strategies (OFS plus tamoxifen) can therefore be used in both Han and Zhuang populations. Given that recent research efforts have focused on oncogene expression or clinical characteristics in different minorities rather than on differences in outcomes of the same treatment strategy,36,37 the current study represents a novel area of investigation.

Tamoxifen therapy is associated with adverse events including endometrial hyperplasia (simple or atypical hyperplasia), ovarian cysts, nausea and vomiting, fatty liver, retinitis, thrombocytopenic purpura, and allergy. Although previous large clinical trials have reported adverse event rates,38 data regarding differences in these rates between/among different races and minorities are lacking. We detected similar adverse events to previous studies,38 and found no difference between Han and Zhuang women in terms of endometrial hyperplasia, ovarian cysts, nausea and vomiting, fatty liver, retinitis, or thrombocytopenic purpura. In contrast, however, Zhuang women exhibited a significantly higher rate of allergic reactions than Han women (6.93% vs. 2.12%), suggesting that the Zhuang population was hypersensitive to tamoxifen plus OFS. On the basis of these results, routine treatments for adverse events are suitable for both Han and Zhuang women, but additional anti-allergen treatment may be beneficial in Zhuang patients. The current results were analyzed using small-sample statistics, and further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm our conclusions.

Breast cancer therapy (especially chemotherapy) is associated with significant side effects in premenopausal women, including the possible loss of ovarian function and fertility.5,14,39 Although fertility and pregnancy are thus of intense importance to young women with breast cancer, considerable controversy remains regarding how fertility and pregnancy concerns affect fertility preservation or treatment decision strategies at the time of the initial cancer diagnosis. Kathryn5 and colleagues focused on fertility concerns and breast cancer treatment and suggested that many young women with newly diagnosed breast cancer had concerns about fertility, which could substantially affect their treatment decisions. However, despite their comprehensive research studies regarding fertility concerns and breast cancer treatment, the authors could not demonstrate how the choice of treatment regimens might influence pregnancy rates or ascertain which type of treatment decision strategies were suitable for breast cancer patients concerned about fertility. Lambertini et al.17 investigated the correlations among chemotherapy, OFS, and pregnancy and showed that treatment regimens comprising chemotherapy plus OFS had no effect on pregnancies in women with breast cancer compared with chemotherapy alone. Despite these clinical studies, no previous studies have investigated differences in the effects of OFS plus tamoxifen on pregnancy rates between minority races or ethnicities. The results of the current study revealed similar pregnancy rates of 5.07% and 4.35%, respectively, in Han and Zhuang women in southern China with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer following OFS plus tamoxifen therapy. This suggests that fertility preservation or treatment decision strategies at the time of initial breast cancer diagnosis may not need to take account of the patient’s ethnicity.

In conclusion, the current study showed that premenopausal Han and Zhuang women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer experienced similar DFS and OS rates following OFS plus tamoxifen. The incidences of endometrial hyperplasia, ovarian cysts, nausea and vomiting, fatty liver, retinitis, and thrombocytopenic purpura were similar in both ethnic groups, but the incidence of allergic reactions was significantly higher among Zhuang compared with Han women. Notably, in relation to fertility concerns, OFS plus tamoxifen treatment was associated with similar pregnancy rates in Zhuang and Han women.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81760481).

References

- 1.DeSantis CE, Fedewa SA, Goding SA, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2015: Convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA Cancer J Clin 2016; 66: 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welch HG, Prorok PC, O'Malley AJ, et al. Breast-cancer tumor size, overdiagnosis, and mammography screening effectiveness. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1438–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ, Balneaves LG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67: 194–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambertini M, Falcone T, Unger JM, et al. Debated role of ovarian protection with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists during chemotherapy for preservation of ovarian function and fertility in women with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 804–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruddy KJ, Gelber SI, Tamimi RM, et al. Prospective study of fertility concerns and preservation strategies in young women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 1151–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burstein HJ, Temin S, Anderson H, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 2255–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2011; 378: 771–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burstein HJ, Lacchetti C, Anderson H, et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update on ovarian suppression . J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 1689–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips KA, Regan MM, Ribi K, et al. Adjuvant ovarian function suppression and cognitive function in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2016; 114: 956–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain S, Santa-Maria CA, Gradishar WJ. The role of ovarian suppression in premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive early-stage breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2015; 29: 473–478, 481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan MM, Pagani O, Fleming GF, et al. Adjuvant treatment of premenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: design of the TEXT and SOFT trials. Breast 2013; 22: 1094–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francis PA, Regan MM, Fleming GF. Adjuvant ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tevaarwerk AJ, Wang M, Zhao F, et al. Phase III comparison of tamoxifen versus tamoxifen plus ovarian function suppression in premenopausal women with node-negative, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (E-3193, INT-0142): a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 3948–3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambertini M, Del ML, Viglietti G, et al. Ovarian function suppression in premenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2017; 18: 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 2500–2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peccatori FA, Azim HA, Orecchia R, et al. Cancer, pregnancy and fertility: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2013; 24(Suppl 6): vi160–vi70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambertini M, Boni L, Michelotti A, et al. Ovarian suppression with triptorelin during adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy and long-term ovarian function, pregnancies, and disease-free survival: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314: 2632–2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satyaswaroop PG, Zaino RJ, Mortel R. Estrogen-like effects of tamoxifen on human endometrial carcinoma transplanted into nude mice. Cancer Res 1984; 44: 4006–4010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boccardo F, Guarneri D, Rubagotti A, et al. Endocrine effects of tamoxifen in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Tumori 1984; 70: 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nomikos IN, Elemenoglou J, Papatheophanis J. Tamoxifen-induced endometrial polyp. A case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1998; 19: 476–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mourits MJ, de Vries EG, Willemse PH, et al. Ovarian cysts in women receiving tamoxifen for breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1999; 79: 1761–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rutqvist LE, Cedermark B, Glas U, et al. The Stockholm trial on adjuvant tamoxifen in early breast cancer. Correlation between estrogen receptor level and treatment effect. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1987; 10: 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole LK, Jacobs RL, Vance DE. Tamoxifen induces triacylglycerol accumulation in the mouse liver by activation of fatty acid synthesis. Hepatology 2010; 52: 1258–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Lippman ME. Tamoxifen retinopathy. Cancer Treat Rep 1978; 62: 315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vinding T, Nielsen NV. Retinopathy caused by treatment with tamoxifen in low dosage. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1983; 61: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enck RE, Rios CN. Tamoxifen treatment of metastatic breast cancer and antithrombin III levels. Cancer 1984; 53: 2607–2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berstein LM, Wang JP, Zheng H, et al. Long-term exposure to tamoxifen induces hypersensitivity to estradiol. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 1530–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan L, Strasser-Weippl K, Li JJ, et al. Breast cancer in China. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: e279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bourgier C, Kerns S, Gourgou S, et al. Concurrent or sequential letrozole with adjuvant breast radiotherapy: final results of the CO-HO-RT phase II randomized trial. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 474–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nerich V, Saing S, Gamper EM, et al. Cost-utility analyses of drug therapies in breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016; 159: 407–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alba E, Calvo L, Albanell J, et al. Chemotherapy (CT) and hormonotherapy (HT) as neoadjuvant treatment in luminal breast cancer patients: results from the GEICAM/2006-03, a multicenter, randomized, phase-II study. Ann Oncol 2012; 23: 3069–3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Regan MM, Francis PA, Pagani O, et al. Absolute benefit of adjuvant endocrine therapies for premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative early breast cancer: TEXT and SOFT trials. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 2221–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pagani O, Regan MM, Walley BA, et al. Adjuvant exemestane with ovarian suppression in premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gnant M, Mlineritsch B, Stoeger H, et al. Zoledronic acid combined with adjuvant endocrine therapy of tamoxifen versus anastrozol plus ovarian function suppression in premenopausal early breast cancer: final analysis of the Austrian breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group trial 12. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu J, Fang M, Zhou X, et al. Paraoxonase 1 gene polymorphisms are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer in a population of Chinese women. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 25362–25371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Y, Hu W, Zhuang W, et al. Interleukin-10 -1082 promoter polymorphism and gastric cancer risk in a Chinese Han population. Mol Cell Biochem 2011; 347: 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Y, Li N, Zhuang W, et al. p53 Codon 72 polymorphism and gastric cancer risk in a Chinese Han population. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2010; 14: 829–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forbes JF, Sestak I, Howell A, et al. Anastrozole versus tamoxifen for the prevention of locoregional and contralateral breast cancer in postmenopausal women with locally excised ductal carcinoma in situ (IBIS-II DCIS): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 866–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Partridge AH, Ruddy KJ, Gelber S, et al. Ovarian reserve in women who remain premenopausal after chemotherapy for early stage breast cancer. Fertil Steril 2010; 94: 638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]