Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether greater effusion-synovitis volume and infrapatellar fat pad (IFP) signal intensity alteration differentiate incident accelerated knee OA (KOA) from a gradual onset of KOA or no KOA.

Methods

We classified three sex-matched groups of participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative who had a knee with no radiographic KOA at baseline (recruited 2004–06; Kellgren–Lawrence <2; n = 125/group): accelerated KOA: ⩾1 knee progressed to Kellgren–Lawrence grade ⩾3 within 48 months; common KOA: ⩾1 knee increased in radiographic scoring within 48 months; and no KOA: both knees had the same Kellgren–Lawrence grade at baseline and 48 months. The observation period included up to 2 years before and after when the group criteria were met. Two musculoskeletal radiologists reported presence of IFP signal intensity alteration and independent readers used a semi-automated method to segment effusion-synovitis volume. We used generalized linear mixed models with group and time as independent variables, as well as testing a group-by-time interaction.

Results

Starting at 2 years before disease onset, adults who developed accelerated KOA had greater effusion-synovitis volume than their peers (accelerated KOA: 11.94 ± 0.90 cm3, KOA: 8.29 ± 1.19 cm3, no KOA: 8.14 ± 0.90 cm3) and have greater odds of having IFP signal intensity alteration than those with no KOA (odds ratio = 2.07, 95% CI = 1.14–3.78). Starting at 1 year prior to disease onset, those with accelerated KOA have greater than twice the odds of having IFP signal intensity alteration than those with common KOA.

Conclusion

People with IFP signal intensity alteration and/or greater effusion-synovitis volume in the absence of radiographic KOA may be at high risk for accelerated KOA, which may be characterized by local inflammation.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, synovium, knee, epidemiology, MRI

Rheumatology key messages

Infrapatellar fat pad signal intensity alteration antedates the onset of accelerated knee OA.

Large effusion-synovitis in a knee without radiographic OA predicts accelerated knee OA.

Introduction

Knee OA (KOA) is typically a slowly progressive disorder. However, at least one in five individuals with incident KOA develop a sudden and rapid onset of radiographic advanced-stage disease, often occurring in as little as 12 months [1–3]. Individuals who develop accelerated KOA have greater pain and disability than those with a more gradual onset of KOA as early as 3 years prior to radiographic development of advanced-stage disease [2]. It remains unclear why adults with accelerated KOA experience prodromal joint symptoms and whether accelerated KOA is a distinct entity (e.g. disorder, phenotype) from the common form of gradual KOA.

Effusion-synovitis and synovitis of the infrapatellar fat pad (IFP), a hyperintense signal within the IFP on fluid-sensitive MRI sequences, may be potential early markers of accelerated KOA because both are associated with pain and predict KOA incidence or progression [4, 5]. Furthermore, signal intensity alteration in the IFP correlates with radiographic KOA, bone marrow lesions and histological chronic synovitis [6–10]. An association has also been found between a change by 24 months in IFP signal intensity alteration and radiographic KOA and pain progression [11]. However, it remains unclear whether effusion-synovitis and IFP signal intensity alteration are associated with incident accelerated KOA. Hence, the purpose of this study is to determine whether greater effusion-synovitis volume and IFP signal intensity alteration differentiate adults with incident accelerated KOA from those with a gradual onset of KOA or no KOA.

Methods

We selected individuals from the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI). Staff at four OAI clinical sites (Pawtucket, RI; Columbus, OH; Baltimore, MD; Pittsburgh, PA) recruited 4796 adults with or at risk for symptomatic KOA between 2004 and 2006 [12]. Institutional review boards at all OAI clinical sites and the OAI coordinating center (University of California, San Francisco, CA) approved the study. The OAI has been approved and meets all criteria for ethical standards regarding human and animal studies defined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and all amendments made thereafter. Institutional review boards at each OAI clinical site and the OAI coordinating center approved the OAI study (approval number 10-00532). All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. These participants are well characterized in other manuscripts regarding accelerated KOA (e.g. [1–3, 13]).

Participant selection

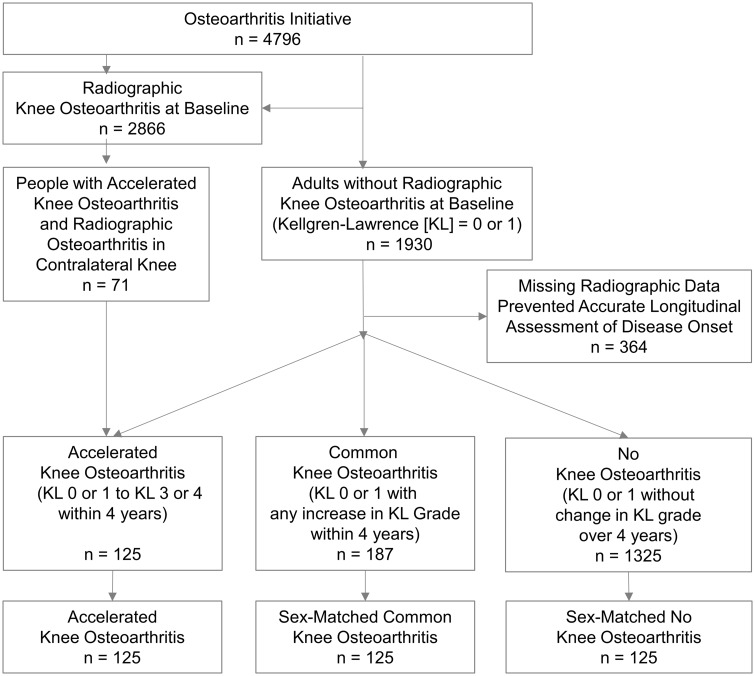

We classified three groups with ⩾1 knee without radiographic KOA [Kellgren–Lawrence (KL) grade <2] at baseline (see Fig. 1 for details): incident accelerated KOA = developed advanced-stage KOA (KL grade 3 or 4) at ⩽48 months [3]; common KOA = increased radiographic scoring at ⩽48 months (i.e. worsening pre-radiographic severity: KL grade 0–1, or incident KOA: KL grade 0 or 1–2); and no KOA = no change in KL grade in either knee from baseline to 48-month follow-up. To match the groups, we first identified adults with common or no KOA with no more than one missing MR image during the first 4 years of the OAI. We then used SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) to assign each male and female a random number from a uniform distribution and used this number to randomly match people with common or no KOA to those in the accelerated KOA group stratified by sex (125 participants/group).

Fig. 1.

Eligibility for participants in the analyses

KL: Kellgren–Lawrence grade.

Index knee

The index knee was the first knee to develop accelerated or common KOA. For individuals with no KOA, the index knee was the same as that person’s matched participant with accelerated KOA.

Index visit

The index visit was the OAI visit when someone met the criteria for accelerated or common KOA. For someone with no KOA, the index visit was the same as that person’s matched participant with accelerated KOA.

Knee radiographs

Blinded central readers read annual bilateral weight-bearing, fixed-flexion posteroanterior knee radiographs and recorded KL grades [0–4; weighted kappa = 0.70–0.80; files: kXR_SQ_BU##_SAS (versions 0.6, 1.6, 3.5, 5.5 and 6.3)] [12].

MRI

MR images were acquired annually with one of four identical Siemens (Erlangen, Germany) Trio 3-Tesla MR systems. Readers performing semi-quantitative scoring received all the OAI sequences [14]. Effusion-synovitis volume was measured using a sagittal intermediate-weighted, turbo-spin echo, fat-suppressed MR sequence: field of view = 160 mm, slice thickness = 3 mm, skip = 0 mm, flip angle = 180 degrees, echo time = 30 ms, recovery time = 3200 ms, 313 × 448 matrix, × resolution = 0.357 mm, and y resolution = 0.511 mm.

Effusion-synovitis volume

We used a customized semi-automatic software, which we developed and validated, to measure knee effusion and synovitis volume (Fig. 2) [13, 15]. The software automatically segmented effusion-synovitis based on a threshold and users adjusted the threshold and removed areas of high-signal intensity that were not effusion-synovitis (e.g. subchondral cysts, blood vessels). The readers were unaware of group assignment and were unblinded to time. Measurements were finalized by the senior reader (J.B.D.; intra-reader reliability ICC3, 1 = 0.96).

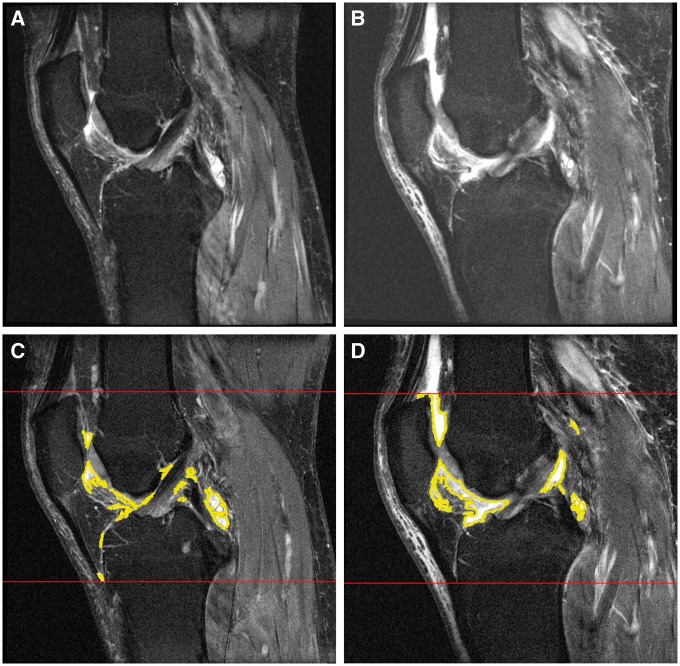

Fig. 2.

Examples of infrapatellar fat pad signal alteration and effusion-synovitis volume

(A, B) Moderate to severe infrapatellar fat pad signal alteration within 24 months. (C, D) Effusion-synovitis software measurements within 24 months.

Infrapatellar fat pad signal intensity alteration

Two musculoskeletal radiologists reviewed MR images (R.J.W.: 255 cases, J.W.M.: 120 cases) to score IFP signal intensity alteration using the Magnetic Resonance Imaging Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS) grading system (Fig. 2) [16]. Readers were blinded to group status but unblinded to time. We considered a score >0 as the presence of signal intensity alteration (kappa = 0.30; agreement = 65%, comparable to prior study [16]).

Patellofemoral OA

Since KL grades focus on the tibiofemoral compartments we determined the presence of patellofemoral OA on MR images to further characterize the study sample. Two readers (J.E.D. and J.B.D.) independently reviewed baseline and 48-month MR images to determine the presence of patellofemoral OA, which was defined by a definite osteophyte and partial or full thickness cartilage loss [17]. After assessing the images, the readers came to a consensus. Prior to consensus, the readers agreed 73% of the time (kappa = 0.36).

Clinical data

Age, BMI, frequent knee pain, days with limited activity in prior month, overall global rating and WOMAC pain were acquired at each visit based on a standard protocol.

Statistical analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics for baseline characteristics of each group. We compared groups using χ2 tests for categorical variables and one-way analyses of variance with post hoc comparisons with a Bonferroni correction.

To explore if effusion-synovitis volume (continuous outcome) differed among groups, we performed linear-mixed models assuming compound symmetry. Independent variables were group and time (up to five levels, categorical variable), which enabled us to also test a group-by-time interaction. Group-by-time interaction is key to our study design since it is important to explore if the accelerated and common KOA groups have a different effusion or synovitis volumes over time, especially during the 2 years prior to meeting the definition of accelerated KOA. Significant interactions (P ⩽ 0.05) led to three post hoc comparisons at each time point. We adjusted for sex (matching variable) and factors related to missing MR data at the next visit (i.e. age, BMI, injury, frequent knee pain, days with limited activity in prior month, overall global rating and WOMAC pain). We calculated the mean change in effusion-synovitis volume during the 2 years that preceded the index visit based on the least-square means.

To determine whether the presence of IFP signal intensity alteration differed between groups we used generalized linear mixed models with a binary outcome, assuming compound symmetry. We used the same independent variables (and interaction), post hoc comparisons and adjustments as described for effusion-synovitis volume.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses that limited the sample size to certain informative subsets and their matched participants in other groups: one group only included people who developed accelerated KOA without contralateral knee at baseline (n = 54/group); one only included individuals who developed accelerated KOA in ⩽12 months (n = 71/group); and one only included those who developed common KOA and had KL = 2 (n = 76/group, matched sample). We also did two sensitivity analyses only adjusting for sex (without matching): one analysis only included those with an index knee KL = 0 at baseline (accelerated KOA n = 42, common KOA = 71, no KOA = 92); and the other only included people with complete MR-based data from all five visits (accelerated KOA n = 12, common KOA n = 29, no KOA n = 25). This sample size was limited because only participants with an index visit at 24 months could have MR data at 2 years before and after index. The sample size was further limited by people who missed one or more of the five visits. We also assessed model diagnostics and reran analyses excluding people with potential influential data (i.e. large Cook’s D or Cook’s D Covariance Parameters).

Finally, we calculated the frequency of having a large effusion-synovitis volume (greater than or equal to the median volume across times and group: 9.43 cm3), IFP signal intensity alterations, neither or both. Statistical analyses were omitted because of the small sample size in certain categories (e.g. only three people with accelerated KOA had neither finding at 2 years after the index visit).

The senior author performed analyses with SAS Enterprise Guide 7.15 (Cary, NC, USA) with input from two statisticians (B.L. and L.L.P.).

Results

Table 1 provides an overview of the descriptive characteristics of the three groups. Overall, the groups were predominantly female (63%), overweight and 24–39% reported frequent knee pain within the prior 12 months. The majority of the no KOA and common KOA groups had KL = 0 at baseline (74 and 57%, respectively), while 34% of the accelerated KOA group had KL = 0 at baseline. Patellofemoral OA was present in 66–75% of the sample.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of adults with accelerated, common, or no knee OA

| Variables at the OA initiative baseline | No KOA (n = 125) | Common KOA (n = 125) | Accelerated KOA (n = 125) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females, n (%) | 79 (63%) | 79 (63%) | 79 (63%) | 1.00 |

| Index knee KL grade = 0, n (%) | 92 (74%) | 71 (57%)a | 42 (34%)a,b | <0.001 |

| Patellofemoral OA (MR-based), n (%) | 80 (66%) | 84 (69%) | 88 (75%) | 0.56 |

| Frequent knee pain in past 12 months, n (%) | 30 (24%) | 49 (39%)a | 44 (35%) | 0.03 |

| Age, years, mean (s.d.) | 57.3 (8.2) | 58.4 (8.4) | 62.5 (8.5)a,b | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (s.d.) | 26.9 (4.4) | 28.1 (4.4) | 29.7 (4.6)a,b | <0.001 |

| Global impact rating, 0–10, mean (s.d.); higher score = greater impact | 0.8 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.5) | 1.7 (1.9)a,b | <0.001 |

| Days limited activities in past 30 days, mean (s.d.) | 1.4 (4.3) | 1.7 (4.8) | 3.2 (7.3)a | 0.03 |

| WOMAC pain index, mean (s.d.) | 1.6 (2.4) | 1.8 (2.3) | 2.3 (3.1) | 0.08 |

KL grade could be 0 or 1.

Post hoc analysis showed statistically significant difference with no KOA (P < 0.017).

Post hoc analysis showed statistically significant difference with common KOA (P < 0.017). KOA: knee OA; KL: Kellgren–Lawrence grade.

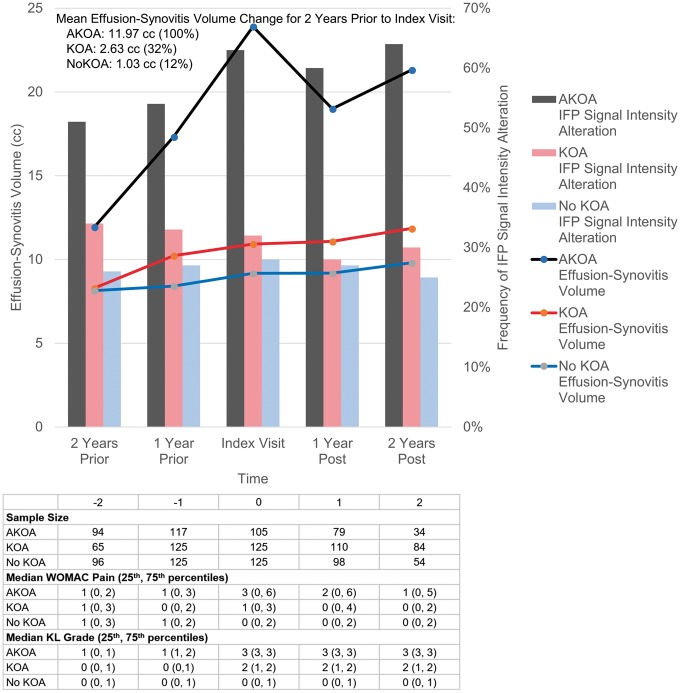

Effusion-synovitis volume

We observed a statistically significant group-by-time interaction (P < 0.001) for effusion-synovitis volume (Fig. 3). When we omitted potential influential observations, the interaction remained statistically significant. Adults who developed accelerated KOA had substantially greater effusion-synovitis volume 2 years or more prior to radiographic onset compared with their peers (vs common KOA: P = 0.015, vs no KOA: P = 0.003; Fig. 3, see Table 2 for least-square means and s.e.s). During the 2 years prior to index visit, adults who developed accelerated KOA had on average a 4.6 and 11.6 times greater increase in effusion-synovitis volume compared with common or no KOA, respectively (Fig. 3). After the index visit, accelerated KOA continued to have significantly greater effusion-synovitis volume when compared with adults with common or no KOA (all P < 0.001). All the sensitivity analyses led to similar patterns described above (see supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online).

Fig. 3.

Effusion-synovitis volume and infrapatellar fat pad signal alteration over time by group

Effusion-synovitis and infrapatellar fat signal intensity alteration among knees with accelerated, common or no knee OA. AKOA: accelerated knee OA; KOA: common knee OA: KL: Kellgren–Lawrence grade; cm3: cubic centimeter.

Table 2.

Adults with accelerated KOA exhibit greater effusion-synovitis than their peers

| LSMeans (s.e.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Visit | Accelerated KOA | Common KOA | No KOA |

| n = 125 | n = 125 | n = 125 | ||

| Effusion-synovitis volume, cm3, mean (s.e.) | −2 | 11.94 (0.90)a,b | 8.29 (1.19) | 8.14 (0.90) |

| −1 | 17.33 (0.83)a,b | 10.23 (0.92) | 8.41 (0.80) | |

| Index | 23.91 (0.82)a,b | 10.92 (0.72) | 9.17 (0.73) | |

| 1 | 19.00 (0.91)a,b | 11.08 (0.75) | 9.18 (0.79) | |

| 2 | 21.32 (1.30)a,b | 11.85 (0.84) | 9.80 (0.99) | |

Significant against KOA.

Significant against no KOA. LSMeans: least square means, which are group means after controlling for a covariate; KOA: knee OA; accelerated KOA: accelerated knee OA; cm3: cubic centimeter.

Infrapatellar fat pad signal intensity alteration

Fig. 2 shows an example of progression from moderate to severe IFP within 24 months. We observed a statistically significant group-by-time interaction (P < 0.001) for IFP signal intensity alteration (Table 3). At 2 years prior to index visit, adults who developed accelerated KOA were more likely to have IFP signal intensity alteration than those with no KOA [odds ratio (OR) = 2.07, 95% CI = 1.14–3.78]. At 1 year prior to disease onset and for the next 3 years, those with accelerated KOA had greater than twice the odds of having IFP signal intensity alteration compared with both common KOA and no KOA (Table 3). We observed no significant differences in IFP signal intensity alteration between knees with common or no KOA.

Table 3.

Infrapatellar fat pad signal intensity alteration among adults with accelerated, common or no knee OA

| Frequency n (%) | Visit | Accelerated KOA | Common KOA | No KOA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2 | 47 (51) | 22 (34) | 25 (26) | |

| −1 | 63 (54) | 41 (33) | 33 (27) | |

| Index | 67 (63) | 40 (32) | 35 (28) | |

| 1 | 48 (60) | 31 (28) | 26 (27) | |

| 2 | 23 (64) | 25 (30) | 13 (25) | |

| Primary analysis, OR (95% CI) | Visit | Accelerated KOA vs no KOA | Common KOA vs no KOA | Accelerated KOA vs common KOA |

| −2 | 2.07 (1.14, 3.78) | 1.67 (0.90, 3.08) | 1.24 (0.69, 2.25) | |

| −1 | 3.06 (1.71, 5.48) | 1.46 (0.82, 2.60) | 2.10 (1.19, 3.69) | |

| Index | 3.68 (2.07, 6.57) | 1.18 (0.68, 2.06) | 3.12 (1.79, 5.44) | |

| 1 | 3.66 (2.04, 6.57) | 1.05 (0.60, 1.85) | 3.48 (1.97, 6.16) | |

| 2 | 3.95 (2.09, 7.46) | 1.06 (0.59, 1.92) | 3.72 (2.01, 6.87) | |

Group-by-time interaction: P < 0.001. Bold indicates statistically significant OR. OR: odds ratio; KOA: knee osteoarthritis; accelerated KOA: accelerated knee OA.

Results of the sensitivity analyses are shown in supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online. At 2 years prior to index visit, all of the sensitivity analyses supported the primary results with two exceptions: among adults who had accelerated KOA develop in <1 year (accelerated KOA vs no KOA: OR = 1.75, 95% CI = 0.82–3.74); and among adults with index knee KL grade = 0 (accelerated KOA vs no KOA: OR = 1.70, 95% CI = 0.74–3.90). Starting at 1 year prior to index, all analyses supported the primary results (OR > 2.00 compared with common or no KOA) with two exceptions when adults with accelerated KOA were compared with those with common KOA: among adults who had accelerated KOA develop in less than a year (accelerated KOA vs common KOA: OR = 1.96, 95% CI = 0.97–3.96); and among adults who had common KOA that developed KL = 2 (accelerated KOA vs common KOA: OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 0.86–3.20). Our sensitivity analyses also supported the primary findings that there are no significant differences in IFP signal intensity alteration between knees with common or no KOA, except at 1 year prior to the index visit for knees that developed common KOA with a KL score = 2 (OR = 2.41, 95% CI = 1.17–4.94).

Fig. 3 displays the pattern of greater effusion-synovitis volume and IFP signal intensity alteration among accelerated KOA compared with common and no KOA. Supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online, offers the frequency of large effusion-synovitis (greater than or equal to the median: 9.43 cm3) and IFP signal intensity alterations either in isolation or combination. Qualitatively, adults with accelerated KOA are always less likely to have neither MR finding (2 years prior: 28%, index visit: 8%) than adults with common KOA (2 years prior: 48%, index visit: 31%) or no KOA (2 years prior: 57%, index visit: 47%). Furthermore, adults with accelerated KOA are always more likely to have both MR findings (2 years prior: 30%, index visit: 61%) than adults with common KOA (2 years prior: 11%, index visit: 17%) or no KOA (2 years prior: 7%, index visit: 13%).

Discussion

We found that accelerated KOA was characterized by greater effusion-synovitis volume and/or IFP signal intensity alteration, which were present years before radiographic evidence and persist years after onset. At 2 years prior to the onset of accelerated KOA >50% of adults had IFP signal intensity alteration and averaged 44% greater effusion-synovitis volume than those with common or no KOA. This persisted until at least 2 years after the onset of disease. Hence, MR-based signs of local inflammation may differentiate accelerated KOA as a distinct entity that often develops advanced-stage disease in <12 months compared with typical KOA, which develops advanced-stage disease over years or decades.

While effusion-synovitis and IFP signal intensity alteration have been found to precede radiographic KOA [6, 8], this was the first observation that they presented more frequently among those with accelerated KOA when compared with their more gradually progressing counterparts. Additionally, effusion-synovitis and IFP signal intensity alteration starting the year before radiographic onset have been associated with any type of incident KOA [6, 8]. However, we determined that IFP signal intensity alteration prior to disease onset was associated with incident accelerated KOA but typically not common KOA development. Within the OAI, one in four to five cases of incident disease experience accelerated KOA [1]. Hence, prior findings may have been significantly influenced by adults with accelerated KOA.

Accelerated KOA may be a distinct clinical entity and early structural changes, such as greater effusion-synovitis volume and common presence of early IFP signal intensity alteration, may explain why these individuals report greater pain and dysfunction compared with individuals with common KOA development [2, 18]. Effusion-synovitis has been linked to increased knee pain among adults with KOA [19, 20]. Additionally, effusion-synovitis among individuals with accelerated KOA may contribute to pain that increases the risk of injury [21], which may be a catalyst for accelerated KOA [1, 22]. The greater effusion-synovitis and increased presence of IFP signal intensity alteration among individuals with accelerated KOA builds on the argument that it is a separate entity from commonly progressing KOA and that it deserves greater attention in both clinical and research settings [2, 18, 23–25]. It may be helpful for future studies to test whether modifying local evidence of inflammation (effusion-synovitis and IFP signal intensity alteration) would reduce the risk of accelerated KOA.

Consistent with prior evidence that questionable signs of radiographic KOA (KL grade of 1) predict incident KOA [26, 27] and accelerated KOA [28], we found adults who develop accelerated KOA had greater baseline prevalence of K = 1 (accelerated KOA = 66%, common KOA = 43%, no KOA = 26%). While adults with accelerated KOA were less likely to have definitively no radiographic KOA (KL = 0) at baseline, we found consistent results in this smaller sample of adults that effusion and synovitis were associated with and antedated the onset of accelerated KOA. The signs of local inflammation may explain why people without KOA are more susceptible to accelerated KOA.

While this study is important in adding to the structural characterization of accelerated KOA, we acknowledge that there are limitations. We have missing MR data that could potentially influence the results. However, in our analyses, we adjusted for factors that may have been related to missing imaging data at the following visit (e.g. age, BMI, injury, frequent knee pain). The sensitivity analyses conducted provided additional confidence in our results. We also acknowledge that the OAI does not have contrast-enhanced MR images to assess synovitis. However, for various ethical, safety and financial reasons we believe that non-contrast-enhanced MR images represent a more ideal strategy to assess IFP signal intensity alteration in future studies or in clinical settings. Our study was also limited by our sample size and the OAI is not a population-based study. Nevertheless, the OAI offered an unprecedented opportunity to address this study question among a sample of people at risk for KOA.

As early as 2 years prior to disease onset over 50% of adults with accelerated KOA have IFP signal intensity alteration and/or present with greater effusion-synovitis. The evidence of local inflammation may indicate that accelerated KOA is a distinct entity from the more common gradual onset of KOA and further research is warranted. These findings begin to shed light on the early changes that may antedate radiographic evidence of accelerated KOA. Clinicians should be aware that people with greater effusion-synovitis and/or IFP signal intensity alteration in the absence of radiographic KOA may be at high risk for accelerated KOA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

G.H.L. is supported by K23 AR062127, an NIH/NIAMS funded mentored award, providing support for design and conduct of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data.

Funding: These analyses were financially supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 AR065977. The OAI is a public–private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2-2258; N01-AR-2-2259; N01-AR-2-2260; N01-AR-2-2261; N01-AR-2-2262) funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Merck Research Laboratories; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline; and Pfizer, Inc. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. This manuscript was prepared using an OAI public-use data set and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the OAI Investigators, the NIH or the private funding partners. This work is supported in part with resources at the VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (#CIN 13-413), at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, TX. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Driban JB, Eaton CB, Lo GH. et al. Association of knee injuries with accelerated knee osteoarthritis progression: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1673–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Driban JB, Price LL, Eaton CB. et al. Individuals with incident accelerated knee osteoarthritis have greater pain than those with common knee osteoarthritis progression: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:1565–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Driban JB, Stout AC, Lo GH. et al. Best performing definition of accelerated knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2016;8:165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roemer FW, Guermazi A, Felson DT. et al. Presence of MRI-detected joint effusion and synovitis increases the risk of cartilage loss in knees without osteoarthritis at 30-month follow-up: the MOST study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1804–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang X, Blizzard L, Halliday A. et al. Association between MRI-detected knee joint regional effusion-synovitis and structural changes in older adults: a cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Atukorala I, Kwoh CK, Guermazi A. et al. Synovitis in knee osteoarthritis: a precursor of disease? Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hill CL, Hunter DJ, Niu J. et al. Synovitis detected on magnetic resonance imaging and its relation to pain and cartilage loss in knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1599–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roemer FW, Kwoh CK, Hannon MJ. et al. What comes first? Multitissue involvement leading to radiographic osteoarthritis: magnetic resonance imaging-based trajectory analysis over four years in the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:2085–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernandez-Madrid F, Karvonen RL, Teitge RA. et al. Synovial thickening detected by MR imaging in osteoarthritis of the knee confirmed by biopsy as synovitis. Magn Reson Imaging 1995;13:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Han W, Aitken D, Zhu Z. et al. Signal intensity alteration in the infrapatellar fat pad at baseline for the prediction of knee symptoms and structure in older adults: a cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1783–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Collins JE, Losina E, Nevitt MC. et al. Semiquantitative imaging biomarkers of knee osteoarthritis progression: data from the foundation for the national institutes of health osteoarthritis biomarkers consortium. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2422–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eckstein F, Wirth W, Nevitt MC.. Recent advances in osteoarthritis imaging–the osteoarthritis initiative. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8:622–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stout AC, Barbe MF, Eaton CB. et al. Inflammation and glucose homeostasis are associated with specific structural features among adults without knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study from the osteoarthritis initiative. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018;19:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peterfy CG, Schneider E, Nevitt M.. The osteoarthritis initiative: report on the design rationale for the magnetic resonance imaging protocol for the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:1433–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Harvey WF. et al. Effect of intra-articular triamcinolone vs saline on knee cartilage volume and pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317:1967–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hunter DJ, Guermazi A, Lo GH. et al. Evolution of semi-quantitative whole joint assessment of knee OA: mOAKS (MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:990–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hunter DJ, Arden N, Conaghan PG. et al. Definition of osteoarthritis on MRI: results of a Delphi exercise. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:963–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davis J, Eaton CB, Lo GH. et al. Knee symptoms among adults at risk for accelerated knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:1083–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yusuf E, Kortekaas MC, Watt I, Huizinga TWJ, Kloppenburg M.. Do knee abnormalities visualised on MRI explain knee pain in knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:60–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baker K, Grainger A, Niu J. et al. Relation of synovitis to knee pain using contrast-enhanced MRIs. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1779–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Driban JB, Lo GH, Eaton CB. et al. Knee pain and a prior injury are associated with increased risk of a new knee injury: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. J Rheumatol 2015;42:1463–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davis JE, Price LL, Lo GH. et al. A single recent injury is a potent risk factor for the development of accelerated knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Rheumatol Int 2017;37:1759–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Driban JB, McAlindon TE, Amin M. et al. Risk factors can classify individuals who develop accelerated knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. J Orthop Res 2018;36:876–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Driban JB, Stout AC, Duryea J. et al. Coronal tibial slope is associated with accelerated knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Driban JB, Ward RJ, Eaton CB. et al. Meniscal extrusion or subchondral damage characterize incident accelerated osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Clin Anat 2015;28:792–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kerkhof HJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Arden NK. et al. Prediction model for knee osteoarthritis incidence, including clinical, genetic and biochemical risk factors. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:2116–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leyland KM, Hart DJ, Javaid MK. et al. The natural history of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a fourteen-year population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Riddle DL, Stratford PW, Perera RA.. The incident tibiofemoral osteoarthritis with rapid progression phenotype: development and validation of a prognostic prediction rule. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:2100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.