Abstract

Background

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture is a serious injury in patients who are typically young and athletically active, with potential long-term complications including functional limitation, posttraumatic osteoarthritis of the knee, and impaired quality of life. ACL reconstruction is now considered the gold standard of treatment for regaining stability and improving knee function. Conservative treatment is an alternative.

Methods

To compare operative and conservative treatment, we reviewed pertinent publications retrieved by a systematic search in Ovid MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and other databases. PROSPERO registration of the study protocol: CRD42017060462 on 31 March 2017.

Results

13 publications concerning a total of 1246 patients were included in the analysis; only two were reports of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In one of the RCTs, ACL reconstruction was found to yield better functional outcomes than conservative management. The other RCT did not reveal any harm from initial conservative management, although the conservative-to-operative crossover rate in this trial was 51%. The functional outcomes were heterogeneous. In six observational studies, knee function was significantly better after surgery; in seven others, it was not. Five out of nine analyses in which knee-joint stability was restored after surgery showed superior functional outcomes after ACL reconstruction compared to conservative management. Three studies in which no satisfactory postoperative knee-joint stability was found did not show any functional difference between surgery and conservative management.

Conclusion

On the basis of RCTs published to date, it cannot be definitively concluded whether surgery or conservative (expectant) management of ACL rupture yields a better functional outcome. There is a trend in observational studies toward better functional outcomes after ACL reconstruction. As an average across studies, conservative treatment fails in 17.5% (± 15.5%) of patients.

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament is a common injury (incidence: 68.6 per 100 000 patient years) that mostly affects young, physically active patients and can lead to chronic instability (1). The lateral tibial plateau in particular is prone to anterior subluxation (anteroposterior instability), as the ligament no longer restricts movement and the axis of rotation can shift medially. Isolated injury to the posterior cruciate ligament is rarer (incidence: 1.8 per 100 000 patient years) (2).

Chronic anteroposterior instability, which manifests in 8 to 50% of cases after surgical treatment and 75 to 87% after conservative treatment (3– 7), is associated with increased risk of posttraumatic osteoarthritis of the knee (prevalence: 24.5 to 51.2%) (8), restricted knee function with reduced activity level (17% of competitive athletes do not return to competitive level) (9), and reduced quality of life (score of 54 to 77 on the KOOS QOL [Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score: Quality of Life] versus 81 to 92 points in the uninjured population) (10). Despite intensive research into anterior cruciate ligament rupture, there is a lack of high-quality studies to determine clear treatment strategies for anterior cruciate ligament–deficient adults. According to the current S1 Guideline of the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften), anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autologous tendon graft is indicated for associated injuries to the collateral ligaments, meniscal injuries suitable for reconstruction, or a marked feeling of instability or subjective loading requirement. It is the first-line treatment for symptomatically unstable patients, in order to restore passive stability of the knee joint. According to meta-analyses and cohort studies, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction can prevent secondary meniscal and cartilage injuries and restore previous activity levels (11– 13).

Until recently there was only one randomized controlled trial, though this was widely recognized, comparing outcomes following early surgery and following conservative treatment with optional delayed surgery. The findings of this trial indicate that nonsurgical treatment with possible delayed surgery leads to comparable subjective knee function and quality of life (14, 15). On the basis of these findings, coverage in the lay press suggested that anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and conservative treatment were of equal value.

Because the evidence for preferring specific treatment options was limited, the aim of this systematic review was to analyze functional differences between surgical and conservative treatment, dependent upon quality of the surgical process (5, 16). Our hypothesis was that stable quality of surgical care (as measured using passive knee stability) results in better functional outcomes than conservative treatment.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search of the literature based on the PRISMA guidelines was performed concerning functional outcome following surgical or conservative treatment for ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament. The search included Ovid MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ACP Journal Club, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Cochrane Methodology Register, Health Technology Assessment, the NHS Economic Evaluation Database, and PsycINFO. It covered the period from the foundation of these sources to 29 July 2018 (etable 1) (17). The study protocol was registered prospectively with PROSPERO (CRD42017060462, 31 March 2017). The articles to be included were selected by two independent authors (MK and FF) on the basis of abstracts, fulltext versions, and bibliographies.

eTable 1. Search strategy by the example of Ovid Medline.

| Step | Search terms | Number of studies |

| 1 | ((anterior adj2 cruciate* adj2 ligament*) or acl).mp. | 22 238 |

| 2 | Surgical Procedures, Operative/ | 53 971 |

| 3 | Orthopedics/ | 19 821 |

| 4 | Traumatology/ | 3246 |

| 5 | Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction/ | 3499 |

| 6 | Orthopedic Fixation Devices/ | 5020 |

| 7 | Suture Techniques/ | 42 233 |

| 8 | Orthopedic Procedures/ | 23 861 |

| 9 | Arthroscopy/ | 22 300 |

| 10 | (surg* or operat* or reconstruct* or repair* or graft* or arthroscop*).mp. | 3 872 087 |

| 11 | 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 | 3 887 896 |

| 12 | Physical Therapy Modalities/ | 37 140 |

| 13 | orthotic devices/ | 6614 |

| 14 | braces/ | 5523 |

| 15 | (non-surg* or nonsurg* or non-operat* or nonoperat* or conserv* or rehab* or physiotherapy or physical therapy or brace* or exercis* or cast*1).mp. | 1 351 837 |

| 16 | 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 | 1 354 925 |

| 17 | 1 and 11 and 16 | 3797 |

| 18 | Randomized controlled trial.pt. | 917 153 |

| 19 | controlled clinical trial.pt. | 182 849 |

| 20 | randomized.ab. | 819 780 |

| 21 | randomly.ab. | 499 737 |

| 22 | placebo.ab. | 409 265 |

| 23 | clinical trials as topic/ | 217 662 |

| 24 | trial.ti. | 416 417 |

| 25 | cohort studies/ | 233 803 |

| 26 | (random* or RCT or placebo or allocat* or crossover* or ‚cross over‘ or trial or (doubl* adj1 blind*) or (singl* adj1 blind*)).ti,ab. | 2 300 780 |

| 27 | 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 | 2 883 698 |

| 28 | (Animal or Animals* or „not Humans*“ or Human cell* or Nonhuman* or non-human*).mp. | 7 219 240 |

| 29 | 27 not 28 | 2 064 766 |

| 30 | 17 and 29 | 755 |

| 31 | remove duplicates from 30 | 720 |

Inclusion criteria:

Adults with closed epiphyseal plates

Anterior cruciate ligament rupture diagnosed via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or arthroscopy

At least one subgroup receiving conservative as well as surgical treatment, including any injuries to the menisci or collateral ligaments

Use of one of the established scores to evaluate knee function (Lysholm, IKDC [International Knee Documentation Committee], Tegner, or KOOS)

Follow-up period of 12 months or more

Postoperative anteroposterior translation reported (extent of anterior drawer, i.e. anterior translation of lower leg in relation to upper leg with the knee bent at 10 to 20°; measured using arthrometry, for example)

Exclusion criteria:

Posterior cruciate ligament injuries

Suturing of the anterior cruciate ligament

Preclinical laboratory tests

Studies in patients with advanced osteoarthritis of the knee (Kellgren–Lawrence grade III/IV), inflammatory arthropathies

Studies analyzing the same study group at various follow-up times

Other systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Primary and secondary endpoints

Our primary endpoint was knee function, which was evaluated using validated scores, such as Lysholm, KOOS, IKDC, or Tegner, or kinematic parameters. The secondary endpoint was the extent to which preinjury sport or activity level was restored.

Evaluation of knee stability

Quality of the surgical process was evaluated according to Noyes et al. (18) and the recommendation of the International Knee Documentation Committee (19), which rates postoperative anteroposterior translation as follows: mean side-to-side difference of less than 3 mm is optimum stability, 5 mm or less is suboptimum stability, and 6 mm or more is insufficient stability.

Evaluation of study quality

The methodological quality of the studies included in the review was evaluated using the Cochrane Quality Assessment Tool of the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group (20). This awards a maximum of 2 points to each of 12 different aspects of a clinical study. As there were few randomized controlled trials, the criterion of whether or not a power analysis had been performed was also included in evaluation of study quality.

Findings

Search results

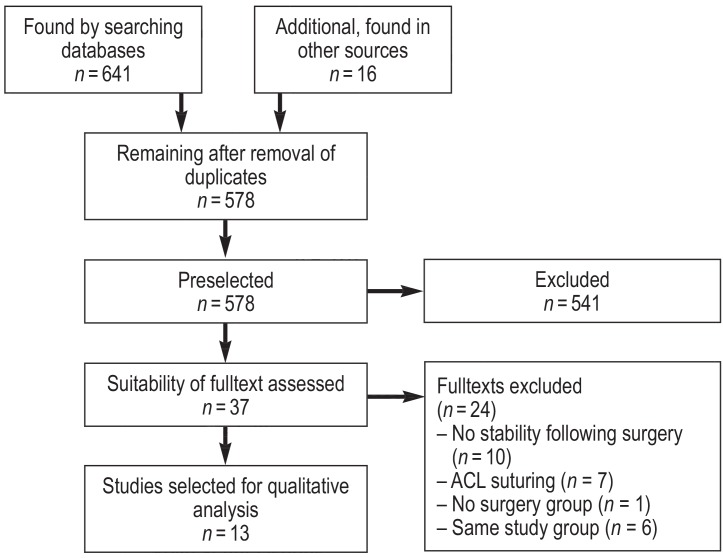

As in an earlier systematic review (5), the 2 studies by Frobell et al. (14, 15) and those by Meuffels et al. (3, 6) were counted as one study each. Eleven studies were excluded due to a lack of data on postoperative knee stability. Other reasons for exclusion were suturing of the anterior cruciate ligament (n = 7) and no allocation to a surgery group (n = 1). A total of 13 studies were included (figure).

Figure.

Flow diagram of systematic search of literature

ACL: anterior cruciate ligament

Study characteristics

This review included 2 prospectively randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (14, 15, 21), 5 nonrandomized prospective cohort studies (22– 26), and 6 retrospective observational studies (3, 4, 6, 7, 27– 29). A total of 1246 patients were investigated (anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: n= 675; conservative treatment: n= 571). The median time from injury to anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction was 5.5 months (1.5 to 44.4). The median time to surgery in the studies that found surgery to be superior was 3.3 months (1.5 to 35.0), versus 6.0 months (2.5 to 44.4) in studies that found surgery and conservative treatment to be of equal value. The mean follow-up period was 117.2 months (12 to 276) (table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics and functional outcomes of studies included in review (surgery/conservative treatment).

|

First author, year (reference), design |

1.

n (surgery/conservative treatment) 2. Age (surgery/ conservative treatment) 3. Follow-up, months |

Anteroposterior stability (side-to-side difference [mm]) (surgery/conservative treatment) |

Lysholm score (surgery/conservative treatment) |

Mean IKDC score: 1. Normal 2. Almost normal 3. Abnormal 4. Very abnormal (surgery/conservative treatment) |

KOOS score (surgery/ conservative treatment): 1. Symptoms 2. Pain 3. ADL 4. Sport 5. QOL |

| Seitz 1994 (4) RCS |

1. 63 / 24 2. Surgery: 27 (15 to 42) Conservative: 28 (18 to 56) 3. 102 (60 to 144) |

<3 mm category: 86% / 8% |

100 to 91 (49 / 12) 90 to 84 (14 / –) 83 to 65 (– / 6) 64 to 0 (– / 6) |

– | – |

| Wittenberg 1998 (7) RCS |

1. 30 / 30 2. 34.3 (22 to 50) 3. 39 (24 to 36) |

2 / 4*1 | 86 / 72*1 | – | – |

| Fink 2001 (29) RCS |

1. 72 / 41 2. 33.0 (± 9.0) 3. Surgery: 132.1 (± 8.1) Conservative: 140.0 (± 9.6) |

2.0 (± 1.5) / 4.0 (± 2.0)*1 | 96 / 83*1 | 1. 0% / 0% *1 2. 44% / 4% 3. 52% / 52% 4. 4% / 44% |

– |

| Fithian 2005 (22) PCS |

1. 63 (early surgery) / 33 (delayed surgery) / 113 (conservative) 2. 39.0 (16–69) 3. 79 |

High risk: 1.6 (± 1.6) / 3.3 (± 1.5) Moderate risk : 1.7 (± 2.0) / 3.1 (± 2.0) Low risk : 2.0 (± 2.0) / 2.3 (±1.8)* 1 |

92 (± 10)/ 88 (± 14)*1. 2 |

1. 33% / 10% *1. 2 2. 50% / 23% 3. 16% / 66% 4. 1% / 2% |

– |

| Kessler 2008 (27) RCS |

1. 60 / 49 2. 30.7 (12.5 to 54.0) 3. 132 |

3.9 (0 to 12) / 5.7 (0 to 16)*1 | – | 1. 53% / 14% *1 2. 18% / 41% 3. 20% / 31% 4. 8% / 14% |

– |

| Tsoukas 2016 (21) RCT |

1. 17 / 15 2. Surgery: 31 (20 to 36) Conservative: 33 (25 to 39) 3. 123 |

1.5 (± 0.2) / 4.5 (± 0.5)*1 | – | 1. 86.8 (± 6.5)/ 77.5 (± 13)*1 |

– |

| Streich 2011 (28) RCS |

1. 40 / 40 2. 25.8 (17 to 39) 3. 180 (± 17) |

2.0 / 2.1 | 68.0 (± 19.8)/ 75.5 (± 15.9) |

1. 69.9 (± 17.0)/ 75.9 (± 13.1) |

– |

| Grindem 2012 (25) PCS |

1. 69 / 69 2. 27.6 (13 to 60) 3. 12.8 (± 1.2) |

2.7 (± 1.8)/5.6 (± 2.8)*1 | – | 1. 85.0 (± 11.6)/ 88.5 (± 9.2) |

– |

| Markström 2018 (26) PCS |

1. 327/ 34 2. Surgery: 46 (± 4.6) Conservative: 48 (± 5.9) 3. 276 |

2.0 (± 2.7) / 4.9 (± 2.9) | 81 (± 64)/ 73 (± 61) |

– | 1. 84 / 75 2. 82 / 89 3. 89 / 98*1 4. 50 / 75*1 5. 49 / 69*1 |

| Meuffels 2009 (3). van Yperen 2018 (6) RCS |

1. 25 / 25 2. 37.7 (± 6.5) 3. 272 |

>3 mm category (2009): 6 (24%) / 17 (68%)*1 3 mm category (2018): 10 (40%) / 19 (83%)*1 |

2009: 88.0 (80.5 to 91.0)/ 85.0 (77.0 to 90.0) 2018: 86.0 (75.5 to 91.0)/ 89.0 (75.5 to 95.5) |

2009: 1. 77.1 (65.1 to 87.3)/ 77.1 (67.5 to 84.9) 2018: 1. 81.6 (59.8 to 89.1)/ 78.2 (61.5 to 92.0) |

2018: 1. 86 / 93 2. 92 / 97 3. 96 / 99 4. 85 / 85 5. 63 / 69 |

| Myklebust 2003 (23) PCS |

1. 57 / 22 2. Not stated 3. 94 |

>3 mm category: 40% / 41% |

85 (± 13)/ 85 (± 13)*2 |

1. 9% /4% 2. 31% /13% 3. 23% /7% 4. 13% /0% |

– |

| Moksnes 2009 (24) PCS |

1. 52 / 50 2. 27.2 (± 8.6) 3. 12 |

4.1 (± 0.7) / 7.6 (± 0.5)*1 | – | 1. 87.0 (± 1.7)/ 86.1 (± 1.6) |

– |

| Frobell 2013 (14) RCT |

1. 62*3 / 59 2. 26.5 (± 5.0) 3. 62 |

6.6 / 8.3*1 | – | – | 1. 83 (78 to 87) / 87 (79 to 95)*3 2. 91 (88 to 94) / 91 (86 to 96) 3. 95 (93 to 97) / 97 (93 to 100) 4. 76 (70 to 81) / 79 (68 to 90) 5. 71 (65 to 76) / 69 (58 to 80) |

*1p <0.05; *2 copers; *3 including delayed anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

ADL: activities of daily living; IKDC: International Knee Documentation Committee; KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; QOL: quality of life; PCS: prospective cohort study;

RCT: randomized controlled trial; RCS: retrospective cohort study

Evaluation of knee joint stability

Turning first to the 2 RCTs, Tsoukas et al. (21) found better anteroposterior stability following surgery (1.5 ± 0.2 mm) than following conservative treatment (4.5 ± 0.5 mm) after 10 years. In contrast, the data obtained by Frobell et al. (15) indicates insufficient anteroposterior stability following surgery (mean KT-1000 score for side-to-side difference: 6.6 mm) (etable 2c). In total, optimum stability following surgery was achieved in 9 of the 13 studies (eTables 2a, 2b).

eTable 2c. Characteristics and functional outcomes of studies included in review that found no significant difference in knee function between conservative treatment and surgery, with suboptimum knee-joint stability.

|

First author, year (reference) (design) |

n (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

Time to surgery (months) |

Age (years) |

Follow-up (months) |

Anteroposterior stability (side-to-side difference [mm]) (surgery/conservative treatment) | Clinical stability, pivot shift, Lachman (surgery/conservative treatment) (clinical [%]) |

Crossover rate (%) |

Lysholm (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

Tegner (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

IKDC (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

KOOS (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

Single-leg hop test (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

RTS/RTPL (surgery/ conservative treatment) (%) |

| Myklebust 2003 (23) (PCS) |

57 / 22 | Not stated | Not stated | 94 | <3 mm category: 40% / 41% |

– | – | 85 (± 13) / 85 (± 13)*1 |

– | Normal: 9% / 4% Almost normal: 31% / 13% Abnormal: 23% / 7% Very abnormal: 13% / 0% |

– | 7 (± 3) / 2 (± 3) (difference in hop between injured & uninjured legs, cm) |

58 / 82 |

| Moksnes 2009 (24) (PCS) |

52 / 50 | 6 (after 3 months’ rehab) |

27.2 (± 8.6) |

12 | 4.1 (± 0.7) / 7.6 (± 0.5)*2 |

– | 16.1 (10 / 62) |

– | – | 87.0 (± 1.7) / 86.1 (± 1.6) |

– | 91.8 (± 1.4) / 95.9 (± 1.4)*2 (hop, % vs. uninjured leg) |

– |

| Frobell 2013 (14) (RCT) |

62*3 / 59 | <2.5 | 26.5 (± 5.0) |

62 | 6.6 / 8.3*2 | 76 / 40 (pivot) 76 / 32 (Lachman) |

51 (30 / 59) |

– | 4 (2 to 7) / 4 (2 to 6.5) |

– | Symptoms: 83 (78 to 87)/ 87 (79 to 95) Pain: 91 (88 to 94) / 91 (86 to 96) ADL: 95 (93 to 97) / 97 (93 to 100) Sport: 76 (70 to 81) / 79 (68 to 90) QOL: 71 (65 to 76)/ 69 (58 to 80) |

– | – |

| Meuffels 2009 (3)/ van Yperen 2018 (6) (RCS) |

25 / 25 | 6 (2 to 258) | 37.7 (± 6.5) |

272 | >3 mm category (2009): 6 (24%) / 17 (68%)*2 (2018): 10 (40%) / 19 (83%)*2 |

2009: 20 / 84 (≥1 + pivot) 2018: 32 / 87 (≥1 + pivot) |

– | 2009: 88.0 (80.5 to 91.0)/ 85.0 (77.0 to 90.0) 2018: 86.0 (75.5 to 91.0) / 89.0 (75.5 to 95.5) |

2009: 6 (4 to 7) / 5 (4 to 7) 2018: 5 (3 to 6) / 4 (4 to 6) |

2009: 77.1 (65.1 to 87.3) / 77.1 (67.5 to 84.9) 2018: 81.6 (59.8 to 89.1) / 78.2 (61.5 to 92.0) |

2018: Symptoms: 86 / 93 Pain: 92 / 97 ADL: 96 / 99 Sport: 85 / 85 QOL: 63 / 69 |

2009: 93.7 (80.0 to 100.7)/ 96.1 (84.2 to 100.9) 2018: 85.9 (68.1 to 101.9) / 95.1 (70.8 to 104.7) (hop, % vs. uninjured leg) |

– |

ADL: activities of daily living; IKDC: International Knee Documentation Committee; KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; PCS: prospective cohort study; QOL: quality of life; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RCS: retrospective cohort study;

RTS: rate of return to sport; RTPL: rate of return to preinjury level; *1 copers; *2 p <0.05; *3 including delayed anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

eTable 2a. Characteristics and functional outcomes of studies included in review that found better function following surgery than following conservative treatment.

|

First author, year (reference) (design) |

n (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

Time to surgery (months) |

Age (years) |

Follow-up (months) |

Anteroposterior stability (side-to-side difference [mm]) (surgery/conservative treatment) |

Clinical stability, pivot shift, Lachman (surgery/ conservative treatment) (clinical [%]) |

Crossover rate (%) |

Lysholm (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

Tegner (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

IKDC (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

KOOS (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

Single-leg hop test (surgery/conservative treatment) |

RTS/RTPL (surgery/conservative treatment) (%) |

| Seitz 1994 (4) (RCS) |

63 / 24 | 4.4 (0.5–12) |

Surgery: 27 (15– 42) Conservative: 28 (18 to 56) |

102 (60 to 144) |

<3 mm category: 86% / 8% |

8 / 83 (pivot) | – | 100 to 91 points: 49 / 12 90 to 84 points: 14 / – 83 to 65 points: – / 6 64 to 0 points: – / 6 |

Tegner equal: 67% / 25% |

– | – | – | 67 / 25 |

| Wittenberg 1998 (7) (RCS) |

30 / 30 | 35 | 34.3 (22 to 50) |

39 (24 to 36) | 2 / 4*1 | 19 / 75 (pivot) 24 / 81 (Lachman) |

– | 86 / 72*1 | 7 to 10*1: 12 / 6 4 to 6: 15 / 19 1 to 3: 3 / 5 |

– | – | – | – |

| Fink 2001 (29) (RCS) |

72 / 41 | 3.3 (± 2.7) |

33.0 (± 9.0) |

Surgery: 132.1 (± 8.1) Conservative: 140.0 (± 9.6) |

2.0 (± 1.5) / 4.0 (± 2.0)*1 |

– | 4.8 (2 / 41) | 96 / 83*1 | – | Normal*1: 0% / 0% Almost normal: 44% / 4% Abnormal: 52% / 52% Very abnormal: 4% / 44% |

– | – | 56 / 30*1 |

| Fithian 2005 (22) (PCS) |

63 (early)/ 33 (delayed) / 113 (conservative) |

<3 | 39.0 (16 to 69) |

79 | High risk: 1.6 (± 1.6)/ 3.3 (± 1.5) Moderate risk: 1.7 (± 2.0)/ 3.1 (± 2.0) Low risk: 2.0 (± 2.0) / 2.3 (± 1.8)* 1 |

Surgery: significantly better pivot |

22.6 (33 / 146) |

92 (± 10) / 88 (± 14)*1. 2 |

6.0 / 3.0*1, 2 | Normal*1, 2: 33% / 10% Almost normal: 50% / 23% Abnormal: 16% / 66% Very abnormal: 1% / 2% |

– | – | – |

| Kessler 2008 (27) (RCS) |

60 / 49 | Not stated | 30.7 (12.5 to 54.0) |

132 | 3.9 (0 to 12) / 5.7 (0 to 16)*1 |

– | 18 (12 / 68)*3 |

– | 5.3 (2 to 10) / 4.9 (2 to 10) |

Normal*1: 53% / 14% Almost normal: 18% / 41% Abnormal: 20% / 31% Very abnormal: 8% / 14% |

– | – | – |

| Tsoukas 2016 (21) (RCT) |

17 / 15 | 1.5 | Surgery: 31 (20 to 36) Conservative: 33 (25 to 39) |

123 | 1.5 (± 0.2) / 4.5 (± 0.5)*1 |

– | 0 | – | 7 (5 to 7)/ 5 (3 to 7) |

86.8 (± 6.5)/ 77.5 (± 13)*1 |

– | – | – |

IKDC: International Knee Documentation Committee; KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; PCS: prospective cohort study; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RCS: retrospective cohort study; RTS: rate of return to sport; RTPL: rate of return to preinjury level;

*1 p<0.05; *2 coper. *3 excluded before analysis

eTable 2b. Characteristics and functional outcomes of studies included in review that found no significant difference in knee function between conservative treatment and surgery, with optimum knee-joint stability.

|

First author, year (reference) (design) |

n (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

Time to surgery (months) |

Age (years) |

Follow-up (months) |

Anteroposterior stability (side-to-side difference [mm]) (surgery/conservative treatment) | Clinical stability, pivot shift, Lachman (surgery/conservative treatment) (clinical [%]) |

Crossover rate (%) |

Lysholm (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

Tegner (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

IKDC (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

KOOS (surgery/ conservative treatment) |

Single-leg hop test (surgery/conservative treatment) |

RTS/RTPL (surgery/ conservative treatment) (%) |

| Streich 2011 (28) (RCS) |

40 / 40 | 7.3 (± 3.2) | 25.8 (17 to 39) |

180 (± 17) | 2.0 / 2.1 | 50 / 57.5 (pivot) | 10.2 (10 / 59) |

68.0 (± 19.8) / 75.5 (± 15.9) |

4.7 (± 1.8)/ 5.1 (± 1.9) |

69.9 (± 17.0) / 75.9 (± 13.1) |

– | – | – |

| Grindem 2012 (25) (PCS) |

69 / 69 | 5.5 (± 2.3) (after 3 months’ rehab) |

27.6 (13 to 60) |

12.8 (± 1.2) | 2.7 (± 1.8) / 5.6 (± 2.8*) |

– | – | – | – | 85.0 (± 11.6)/ 88.5 (± 9.2) |

– | 90.5 (± 14.0) / 96.3 (± 6.4)* (hop distance, LSI) |

68.1 / 68.1 |

| Markström 2018 (26) (PCS) |

32 / 34 | 44.4 (after 3 months’ rehab) |

Surgery: 46 (± 4.6) Conservative: 48± 5.9 |

276 | 2.0 (± 2.7) / 4.9 (± 2.9) |

– | – | 81 (± 64) / 73 (± 61) |

4 (± 4) / 4 (± 5) |

– | Symptoms: 84 / 75 Pain: 82 / 89 ADL: 89 / 98* Sport: 50 / 75* QOL: 49 / 69* |

0.20 (± 0.04) / 0.17 (± 0.03)* (height of hop, m) |

– |

| Meuffels 2009 (3)/ van Yperen 2018 (6) (RCS) |

25 / 25 | 6 (2 to 258) |

37.7 (± 6.5) |

272 | >3 mm category (2009): 6 (24%) / 17 (68%)* 3 mm category (2018): 10 (40%) / 19 (83%)* |

2009: 20 / 84 (≥1 + pivot) 2018: 32 / 87 (≥1 + pivot) |

– | 2009: 88.0 (80.5 to 91.0)/ 85.0 (77.0 to 90.0) 2018: 86.0 (75.5 to 91.0) / 89.0 (75.5 to 95.5) |

2009: 6 (4 to 7) / 5 (4 to 7) 2018: 5 (3 to 6) / 4 (4 to 6) |

2009: 77.1 (65.1 to 87.3) / 77.1 (67.5 to 84.9) 2018: 81.6 (59.8 to 89.1) / 78.2 (61.5 to 92.0) |

2018: Symptoms: 86 / 93 Pain: 92 / 97 ADL: 96 / 99 Sport: 85 / 85 QOL: 63 / 69 |

2009: 93.7 (80.0 to 100.7)/ 96.1 (84.2 to 100.9) 2018: 85.9 (68.1 to 101.9) / 95.1 (70.8 to 104.7) (hop, % vs. uninjured leg) |

– |

ADL: activities of daily living; IKDC: International Knee Documentation Committee; KOOS: Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; LSI: Limb Symmetry Index; PCS: Prospective cohort study; QOL: quality of life; RCS: retrospective cohort study;

RTS: rate of return to sport; RTPL: rate of return to preinjury level; *p <0.05

Primary outcome

The 2 RCTs had differing knee function–related findings. Whereas Tsoukas et al. (21) found that reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament was functionally superior to conservative treatment (IKDC score 86.8 ± 6.5 points versus 77.5 ± 13.8 points), Frobell et al. (14, 15) found no significant differences in KOOS or Tegner score between surgery and nonsurgical treatment with optional delayed surgery. Of the 13 studies included in the review, 6 showed significantly better knee function (Lysholm, KOOS, IKDC, Tegner, or kinematic parameters) following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (4, 7, 21, 22, 27, 29). Seven studies described similar functional outcomes in both treatment groups (3, 14, 15, 23– 26, 28). Of the 6 studies that found surgery to be superior, 5 found optimum stability following surgery. Of the 7 studies that yielded no evidence of superiority for either surgical or conservative treatment, only 4 achieved anteroposterior translation of less than 3 mm (eTables 2b, 2c) (3, 14, 23, 24). Although Markström et al. (26) found comparable Lysholm and Tegner scores and better KOOS ADL (activities of daily living) and KOOS Sport scores following conservative treatment, they found evidence of significantly better functional stability in hop tests following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (take-off: R2 = 0.15 to 0.26; landing: R2 = 0.2 to 0.28) after 23 years. This was not confirmed in 2 other studies; in these, either follow-up lasted only one year (25) or patients with time to surgery of more than 20 years were included (3).

Secondary outcome

All the studies, including the 2 RCTs, reported a significant decrease in activity level (Tegner score) following injury to the anterior cruciate ligament (0.55 to 5.25 points) (3, 6, 14, 15, 22, 21, 22, 26– 28).

Whereas Frobell et al. (14, 15) found no significant improvement in activity level following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and Tsoukas et al. (21) provided no specific data, in 4 of the 8 nonrandomized studies anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction led to a significantly higher level of activity (Tegner score: 0 to 1.5 points) than conservative treatment (–2 to –3 points) (4, 7, 21, 22). Seitz et al. (4) and Fink et al. (29) showed higher rates of return to preinjury sporting level after surgery, with optimum stability following surgery. In contrast, Grindem et al. (25) found no significant differences in terms of return to sport, even with optimum stability following surgery. The higher return rates for conservative treatment than surgery found by Myklebust et al. (23) should be interpreted in the context of suboptimum quality of surgical process.

Crossover rates

On average, 17.5 ± 15.5% of patients who initially received conservative treatment switched study group during the studies and underwent surgery. While Tsoukas et al. described a rate of 0% after 10 years, Frobell et al. reported the highest crossover rate, 51% after 5 years (table 1).

Evaluation of study quality

The quality of the studies was generally low (table 2). Only 2 prospective randomized trials were identified (14, 15, 21). Even these RCTs have a high potential for bias, as the outcome assessor was not blinded. Tsoukas et al. (21) did not perform an a priori power analysis. The studies by Frobell et al. (outcome: KOOS [14, 15]) and Markström et al. (outcome: knee flexion [26]) were the only ones in which power analyses were performed to determine the probability of type II errors. There were only 2 studies that included blinding before group allocation (14, 15, 21). Only Frobell et al. (14, 15) described intention-to-treat analysis (point B), only 2 studies included blinding of outcome assessors (point C) (3, 28), and there was no attempt to blind subsequent treatment providers in any of the studies (point F). There were only 2 studies in which the patient groups had identical rehabilitation programs (21, 27) (point G).

Table 2. Summary of methodological quality: Assessment Tool of the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group (20).

| Author, year (reference) | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L |

| Seitz 1994 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Wittenberg 1998 (7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Fink 2001 (29) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Myklebust 2003 (23) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Fithian 2005 (22) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kessler 2008 (27) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Moksnes 2009 (24) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Meuffels & van Yperen 2009, 2018 (3, 6) |

0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Streich 2011 (28) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Grindem 2012 (25) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Frobell 2013, 2010 (14, 15) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Tsoukas 2016 (21) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Markström 2017 (26) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Mean | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 1.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.69 | 1.46 | 1.77 | 2 | 2 | 1.92 |

A Was the assigned treatment adequately concealed prior to allocation?

B Were the outcomes of participants who withdrew described and included in the analysis (intention to treat)?

C Were the outcome assessors blinded to treatment status?

D Were the treatment and control group comparable at entry?

E Were the subjects blind to assignment status after allocation?

F Were the treatment providers blind to assignment status?

G Were care programs, other than the trial options, identical?

H Were the inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly defined?

I Were the interventions clearly defined?

J Were the outcome measures used clearly defined?

K Were diagnostic tests used in outcome assessment clinically useful?

L Was the surveillance active, and of clinically appropriate duration?

Discussion

This systematic review identified only 2 prospectively randomized controlled trials, and these yielded conflicting findings for stability scores. Five of the 9 studies with optimum stability following surgery and one further study that showed suboptimum quality of surgical process found functional superiority in terms of clinical scores (Tegner, Lysholm, KOOS, or IKDC) for surgery versus conservative treatment. In contrast, 3 of the 4 studies that did not find optimum knee joint stability after surgery found no difference between conservative treatment and surgery in terms of functional improvement. This confirmed our initial hypothesis.

A mean of 83% of competitive athletes return to their preinjury sporting level following surgery; this figure varies according to the type of sport in question (9, 30). Similarly, 80% of amateur athletes return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (31). However, without surgery only 19% of patients return to their preinjury sporting level (32). Good outcomes for conservative treatment are primarily correlated with a reduction in activity level and individual motivation (29, 33, 34). Register data on a large group of patients provides evidence that anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction can lead to better quality of life, higher levels of sporting activity, and lower subjective instability than conservative treatment (35). Although the differences were small, they were statistically significant (35). Data on anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions that were subjectively perceived as unstable during studies was not explicitly excluded (35). In addition to exposure to repeat injury and individual risk-factor constellations, surgical technique is an important guarantor of success in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (36). Good stability—and other outcomes—can be achieved only with correct drill-tunnel placement, correct graft selection, and secure graft anchoring, and by addressing associated peripheral instabilities (29, 36). Stable anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction leads to improved proprioception and superior knee-joint kinematics in comparison to conservative treatment. The objectively measurable functional gain is, however, not necessarily reflected in subjective parameters (26, 37).

Tsoukas et al. (21), whose trial was the only randomized prospective trial with confirmed optimum knee-joint stability following surgery, found better functional outcomes following surgery than following conservative treatment, and the difference was statistically significant. These findings are limited because of the small case number and the absence of a power analysis to validate their level of certainty. In contrast, in the other RCT Frobell et al. (14, 15) found no evidence of superior function following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. However, this study’s data on postoperative stability indicates that the quality of the surgical process was poor. KT-1000 stability scores of 6.6 mm 2 years after surgery correspond clinically to persistent anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency; the aim of surgery, a postoperatively stable knee joint with typical stability scores between –0.1 and 2.3 mm, was not achieved (18, 19, 38).

Furthermore, it is misleading to interpret the findings of Frobell et al. as being those of a study of superiority (15). Although they found no difference between the 2 treatment groups, it is not correct to conclude the reverse, i.e. that the 2 treatment options are of equal value (absence of evidence is not evidence of absence; [39]). Rather, a noninferiority analysis is required. In addition, the as-treated analysis—which is different from the intention-to-treat analysis—has a high risk of bias. Patients who chose surgery during the study may have been more severely injured than those who received conservative treatment. The individual comparison of groups was no longer protected by randomization. Even if assuming that around 49% of patients could have avoided anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, the study provides no indication of which patients would cope without surgery. This is critical in that according to data from observational studies delayed surgery leads to a statistically significantly increased risk of subsequent associated injuries such as meniscal ruptures and of increased prevalence of osteoarthritis of the knee (22). The RCTs, however, do not find this increased risk. Conservative treatment is a clear treatment option. However, there are currently no clear criteria to identify which patients will cope without surgery. One suitable way would be to explain to patients that in half of cases surgery will still be needed. Conservative treatment or delayed surgery may even be inferior to early surgery because of the potentially higher risk of secondary injuries, particularly in young, physically active patients; nevertheless, the RCTs found only weak evidence of this. Frobell et al. could not confirm that the 2 treatment options were of equal value, but neither do the primary endpoints indicate that early surgery is superior.

Of the 4 studies that found optimum stability following surgery but no advantages in terms of functional improvement, one nevertheless found significantly better functional stability in hop tests in the group that had undergone surgery (26). The 3 other studies had quality-related shortcomings. One other study found high rates of persistent rotational instability (50%) despite optimum anteroposterior stability, which limits the conclusion that the two treatment options are of equal value (28). While the follow-up period in the third study is only 12 months (25), the fourth includes patients with time to surgery of up to 21.5 years (3).

The RCTs included in this review found no evidence of a protective effect of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in terms of secondary associated lesions (meniscus or cartilage) or secondary arthritis. However, this was not the subject addressed by our review. Other scientific literature published on this subject to date is conflicting.

The major limitation of this systematic review was the low level of evidence of the studies included in it. It was only possible to include 2 RCTs, and even these were of poor quality (16). There were also substantial differences between times from injury to surgery. Despite the lack of prospectively randomized trials, early surgery—within 10 to 12 weeks—seems to be superior in terms of rotational stability, functional outcome, secondary injury to the menisci or cartilage, and general cost-efficiency (14, 15, 22, 40). Only 3 of the studies included in this review examined patients who underwent early surgery (less than 12 weeks postinjury). Studies that found no difference between surgical and conservative treatment generally examined anterior cruciate ligament ruptures that received delayed surgery, including as late as 21.5 years postinjury (3). As a result, a group of patients for whom conservative treatment had failed, including cases of secondary associated injury, were compared with patients who had undergone successful conservative treatment.

Summary

As proposed in our initial hypothesis, a majority of studies in which postoperative knee-joint stability was optimum found better knee function following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction than following conservative treatment, although the latter is an alternative treatment option.

The design of future studies should make a clear distinction between anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction for acute or subacute anterior cruciate ligament injuries on the one hand and surgery for patients for whom conservative treatment has failed on the other. Because potential differences between groups can only be detected with very high patient numbers if the distinction made between subjective functional parameters is insufficiently clear, a standardized method should be used to examine surgical technique and outcome of surgery, with sufficient power determined in advance.

Key messages.

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament can lead to persistent functional limitations, posttraumatic osteoarthritis of the knee, and reduced quality of life.

Conservative/expectant treatment is an option (not inferior to early surgery in one RCT). In the authors’ view it is more suitable for patients who have neither a high activity level nor associated lesions.

In the authors’ view, the premise that conservative treatment is of equal value to surgery is not confirmed. Conservative treatment fails in a mean of 17.5% of cases.

Functional improvement following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction seems to be greater than that following conservative treatment. It is dependent upon the quality of surgery.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Shimakawa-Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Frosch has received lecture fees and reimbursement of participation fees from Arthrex GmbH.

Prof. Petersen has received royalties, consultancy fees, lecture fees, and reimbursement of travel costs for participation in continuing education events from Storz and Otto Bock. He has received consultancy fees and reimbursement of travel costs from Ossür.

Dr. Akoto has received reimbursement of participation fees for a conference or continuing education event from Conmed and Smith & Nephew and reimbursement of travel or accommodation costs from Conmed, Arthrex, Smith & Nephew, and Mathys.

The other authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Sanders TL, Maradit Kremers H, Bryan AJ, et al. Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears and reconstruction: a 21-year population-based study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:1502–1507. doi: 10.1177/0363546516629944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders TL, Pareek A, Barrett IJ, et al. Incidence and long-term follow-up of isolated posterior cruciate ligament tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:3017–3023. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4052-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meuffels DE, Favejee MM, Vissers MM, Heijboer MP, Reijman M, Verhaar JA. Ten year follow-up study comparing conservative versus operative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures A matched-pair analysis of high level athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:347–351. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.049403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seitz H, Chrysopoulos A, Egkher E, Mousavi M. [Long-term results of replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament in comparison with conservative therapy] Chirurg. 1994;65:992–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith TO, Postle K, Penny F, McNamara I, Mann CJ. Is reconstruction the best management strategy for anterior cruciate ligament rupture? A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction versus non-operative treatment. Knee. 2014;21:462–470. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Yperen DT, Reijman M, van Es EM, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Meuffels DE. Twenty-year follow-up study comparing operative versus nonoperative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in high-level athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:1129–1136. doi: 10.1177/0363546517751683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittenberg RH, Oxfort HU, Plafki C. A comparison of conservative and delayed surgical treatment of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures A matched pair analysis. Int Orthop. 1998;22:145–148. doi: 10.1007/s002640050228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris KP, Driban JB, Sitler MR, Cattano NM, Balasubramanian E, Hootman JM. Tibiofemoral osteoarthritis after surgical or nonsurgical treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a systematic review. J Athl Train. 2017;52:507–517. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai CC, Ardern CL, Feller JA, Webster KE. Eighty-three per cent of elite athletes return to preinjury sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review with meta-analysis of return to sport rates, graft rupture rates and performance outcomes. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(21):28–38. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filbay SR, Culvenor AG, Ackerman IN, Russell TG, Crossley KM. Quality of life in anterior cruciate ligament-deficient individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1033–1041. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mall NA, Chalmers PN, Moric M, et al. Incidence and trends of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2363–2370. doi: 10.1177/0363546514542796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brambilla L, Pulici L, Carimati G, et al. Prevalence of associated lesions in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: correlation with surgical timing and with patient age, sex, and body mass index. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2966–2973. doi: 10.1177/0363546515608483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajuied A, Wong F, Smith C, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament injury and radiologic progression of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2242–2252. doi: 10.1177/0363546513508376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, Roemer FW, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS. Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial. BMJ. 2013;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:331–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monk AP, Davies LJ, Hopewell S, Harris K, Beard DJ, Price AJ. Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011166.pub2. CD011166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Revision anterior cruciate surgery with use of bone-patellar tendon-bone autogenous grafts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:1131–1143. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wera JC, Nyland J, Ghazi C, et al. International knee documentation committee knee survey use after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a2005-2012 systematic review and world region comparison. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:1505–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cochrane Bone Joint and Muscle Trauma Group. Resources for developing a review. http://bjmt.cochrane.org/resources-developing-review (last accessed 24 April 2018) 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsoukas D, Fotopoulos V, Basdekis G, Makridis KG. No difference in osteoarthritis after surgical and non-surgical treatment of ACL-injured knees after 10 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:2953–2959. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3593-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Stone ML, et al. Prospective trial of a treatment algorithm for the management of the anterior cruciate ligament-injured knee. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:335–346. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myklebust G, Holm I, Maehlum S, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Clinical, functional, and radiologic outcome in team handball players 6 to 11 years after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:981–989. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310063901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moksnes H, Risberg MA. Performance-based functional evaluation of non-operative and operative treatment after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19:345–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grindem H, Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. A pair-matched comparison of return to pivoting sports at 1 year in anterior cruciate ligament-injured patients after a nonoperative versus an operative treatment course. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2509–2516. doi: 10.1177/0363546512458424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markström JL, Tengman E, Hager CK. ACL-reconstructed and ACL-deficient individuals show differentiated trunk, hip, and knee kinematics during vertical hops more than 20 years post-injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(2):358–367. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4528-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler MA, Behrend H, Henz S, Stutz G, Rukavina A, Kuster MS. Function, osteoarthritis and activity after ACL-rupture: 11 years follow-up results of conservative versus reconstructive treatment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:442–448. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0498-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streich NA, Zimmermann D, Bode G, Schmitt H. Reconstructive versus non-reconstructive treatment of anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency A retrospective matched-pair long-term follow-up. Int Orthop. 2011;35:607–613. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fink C, Hoser C, Hackl W, Navarro RA, Benedetto KP. Long-term outcome of operative or nonoperative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture–is sports activity a determining variable? Int J Sports Med. 2001;22:304–309. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-13823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohtadi NG, Chan DS. Return to sport-specific performance after primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0363546517732541. 363546517732541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1543–1552. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurd WJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A 10-year prospective trial of a patient management algorithm and screening examination for highly active individuals with anterior cruciate ligament injury: part 1, outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:40–47. doi: 10.1177/0363546507308190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konrads C, Reppenhagen S, Belder D, Goebel S, Rudert M, Barthel T. Long-term outcome of anterior cruciate ligament tear without reconstruction: a longitudinal prospective study. Int Orthop. 2016;40:2325–2330. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roessler KK, Andersen TE, Lohmander S, Roos EM. Motives for sports participation as predictions of self-reported outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament injury of the knee. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25:435–440. doi: 10.1111/sms.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ardern CL, Sonesson S, Forssblad M, Kvist J. Comparison of patient-reported outcomes among those who chose ACL reconstruction or non-surgical treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27:535–544. doi: 10.1111/sms.12707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Group M, Wright RW, Huston LJ, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of the multicenter ACL revision study (MARS) cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1979–1986. doi: 10.1177/0363546510378645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Relph N, Herrington L, Tyson S. The effects of ACL injury on knee proprioception: a meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2014;100:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C, Lu H, Hu J, et al. Anatomic reconstruction of anterior talofibular ligament with tibial tuberosity-patellar tendon autograft for chronic lateral ankle instability. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2018;26 doi: 10.1177/2309499018780874. 2309499018780874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altman DG, Bland JM. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ. 1995;311 doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7003.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mather RC, Hettrich CM, Dunn WR, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of early reconstruction versus rehabilitation and delayed reconstruction for anterior cruciate ligament tears. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1583–1591. doi: 10.1177/0363546514530866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]