Abstract

With improvements in breast imaging, mammography, ultrasound and minimally invasive interventions, the detection of early breast cancer, non-invasive cancers, lesions of uncertain malignant potential, and benign lesions has increased. However, with the improved diagnostic capabilities comes a substantial risk of false-positive benign lesions and vice versa false-negative malignant lesions. A statement is provided on the manifestation, imaging, and diagnostic verification of isolated benign breast tumours that have a frequent manifestation, in addition to general therapy management recommendations. Histological evaluation of benign breast tumours is the most reliable diagnostic method. According to the S3 guideline and information gained from analysis of the literature, preference is to be given to core biopsy for each type of tumour as the preferred diagnostic method. An indication for open biopsy is also to be established should the tumour increase in size in the follow-up interval, after recurring discrepancies in the vacuum biopsy results, or at the request of the patient. As an alternative, minimally invasive procedures such as therapeutic vacuum biopsy, cryoablation or high-intensity focused ultrasound are also becoming possible alternatives in definitive surgical management. The newer minimally invasive methods show an adequate degree of accuracy and hardly any restrictions in terms of post-interventional cosmetics so that current requirements of extensive breast imaging can be thoroughly met.

Key Words: Benign breast tumours, Overview, Imaging features, Minimally invasive diagnostics, Therapy

Introduction

With improvements in breast imaging, mammography, ultrasound and minimally invasive interventions, the detection of early breast cancer, non-invasive cancers, lesions of uncertain malignant potential, and benign lesions has increased. However, with the improved diagnostic capabilities comes a substantial risk of false-positive benign lesions and vice versa false-negative malignant lesions.

Whereas ‘Imaging Report and Data System’ (BI-RADS) lesions classified in Group 2 as definitely benign in mammography terms require no further clarification, it is recommended that cases of tumours that are classified as BI-RADS Group 3 in mammography terms should be subjected to a shorter follow-up interval or biopsy in view of their unclear malignant potential [1]. Benign breast tumours include both lesions classified as BI-RADS 2 (such as lipomas) and tumours classified as BI-RADS 3 (such as phyllodes tumours) [2]. A statement is provided on the manifestation, imaging, and diagnostic verification of isolated benign breast tumours that have a frequent manifestation, in addition to general therapy management recommendations.

Papillomas

Papillomas (first described by Warren in 1905 [3]) are found in around 1–3% of all biopsy tissue samples taken from the breast [4,5] (figs. 1, 2). The relevance of milk duct papillomas is not to be underestimated despite this relatively low incidence, as they are deemed to be a risk factor for malignant processes regardless of whether it is a solitary or a multiple manifestation. In pathogenetic terms, the development of papillomas can be explained by a reversal of the proliferation direction. Whereas a mesenchymal induction occurs in all hyperplasias, with papillomas, a strong epithelial autonomy results in the formation of free epithelial masses that then set themselves apart in the mesenchymal proliferation.

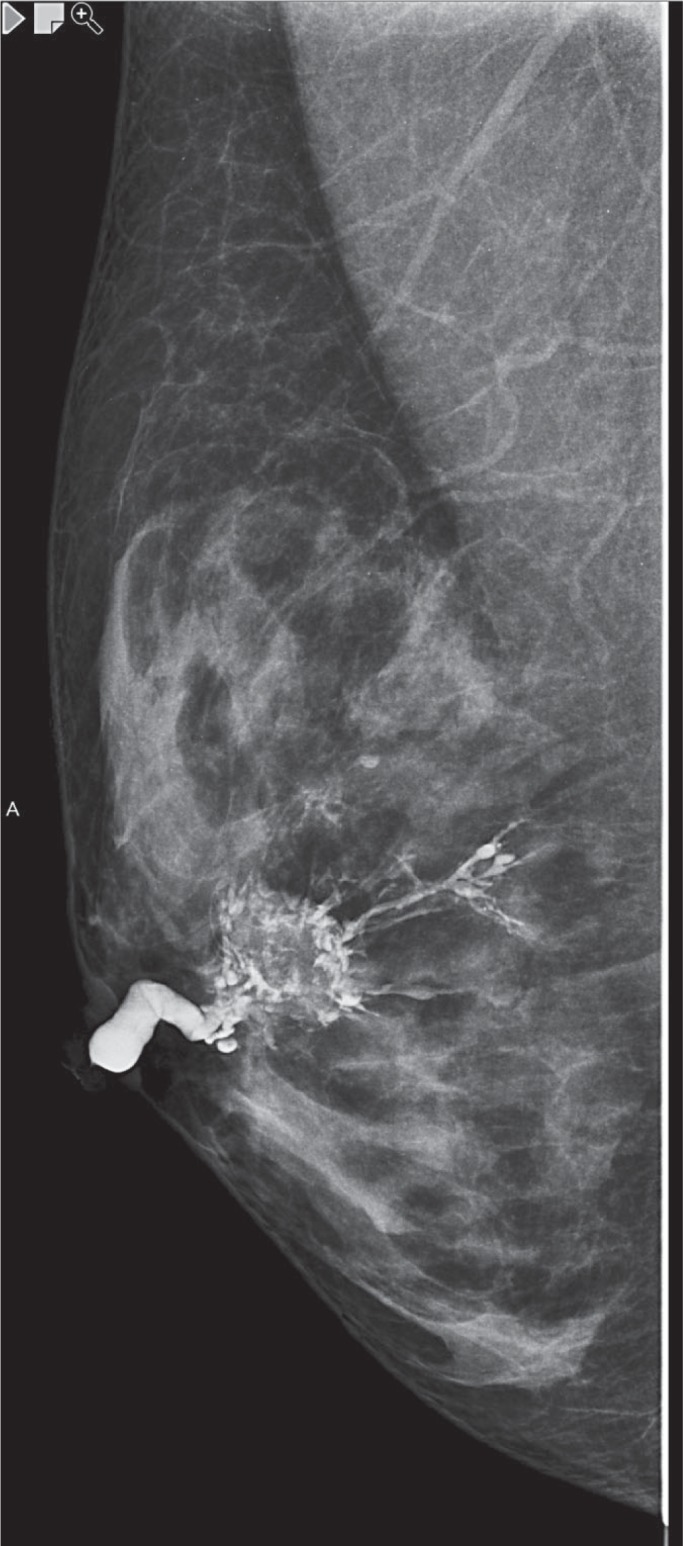

Fig. 1.

Intraductal papilloma - galactography.

Fig. 2.

Sonographic presentation of a papilloma.

Terminology

The papilloma group comprises [6]:

- intraductal solitary papilloma

- intraductal multiple papilloma

- papillomatosis

- juvenile papillomatosis.

The differentiation is made on the basis of the intraductal distribution of the papillomas, with solitary papillomas finding their genesis in the large, segmental, and subsegmental efferent ducts and multifocal localised papillomas originating from the terminal duct lobular units [7]. Papillomatosis is defined as a minimum of 5 papillomas that are clearly separated from each other within a restricted segment of the breast tissue [8]. Juvenile papillomatosis is a neoplasia that effects young females and is characterised by an atypical papillary ductal hyperplasia and numerous cystic formations. This disease is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer [9,10].

Clinic

Age at Manifestation, Size, and Prevalence

Intraductal solitary papillomas have a prevalence of 1.8% of all mammary tumours, and the manifestation is typically identifiable in perimenopausal females [11]. As longitudinal-oval tumours, they generally have a diameter of under 0.5 cm with a maximum length of 4–5 cm [12]. Multiple intraductal papillomas account for around 10% of all intraductal papillomas. Compared to solitary papillomas, the manifestation is most likely in younger patients and more frequently bilateral. Multiple intraductal papillomas are also less likely to cause milk duct secretion. Papillomas frequently cause serosanguinous milk duct secretion [6] and 80–100% of cases present with secretion or bleeding from the nipple. In this context, secretion is a clinical symptom of solitary central papillomas in 64–88% of all cases, whereby this is only 25–35% of all cases of multiple peripheral papilloma [13].

Non-Invasive Diagnostics

Palpation

A tumour can be palpated in 11–57% of cases of solitary papilloma. The detected mass is normally a widened milk duct in which the papilloma is able to extend and cause an obstruction.

Mammography

Intraductal papillomas are not normally detected on mammography due to their small size and the typical location in the central and more compact regions of the breast. Mammographic images related to papillomas include circumscribed retroaleolar nodes that have a benign appearance, a solitary retroaleolar widened milk duct, and seldom microcalcifications [14,15]. Some papillomas can cause sclerosis with the result that the subsequent calcification presents as coarsely flocculated, shell-shaped, or punctiform intraductal calcifications that extend along the milk duct (fig. 2).

Ultrasound

Intraductal papillary neoplasias show different ultrasound presentations depending on their macroscopic appearance. A characteristic feature of papilloma is however a widened milk duct with an intraductal round focus or a cyst with an intracystic solid structure [16] (fig. 2). According to Han et al. [17], intraductal neoplasias are subdivided into 4 categories based on their relationship to the milk duct in the ultrasound examination:

- Type 1: intraluminal mass

- Type 2: extraductal mass

- Type 3: simple solid mass

- Type 4: a combination (fig. 2).

The use of sonographic elastography in combination with conventional ultrasound can improve specificity when it comes to differentiating between benign or atypical or malignant papillary breast lesions [18].

MRI

Intraductal papillomas can present differently on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination. Findings include concealed formations, small luminal structures, or irregular fast growing lesions that cannot be differentiated from invasive malignomas. High costs, limited clinical experience, and suboptimal specificity restrict the use of MRI in this context [19,20,21].

Minimally Invasive Diagnostics

Based on minimally invasive biopsy, intraductal papillomas are classified as B3 lesions in histopathological terms (lesions of unclear biological potential) [22,23,24,25,26].

CB

Core biopsy (CB) has restrictions similar to those of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). There is therefore a general consensus with regard to surgical excision being required for papillomas with atypical features verified by CB [27,28,29,30,31,32].

VAB

Should intraductal papillomas be detectable on mammography and/or ultrasound, a vacuum biopsy (VAB) can be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. This minimally invasive method provides secure and accurate tissue analysis and, with a high degree of possibility, can remedy symptoms in patients suffering from nipple discharge [33].

Ductoscopy

Ductoscopy is an endoscopic technique to examined and evaluated the interior of pathologically secreting milk ducts [34]. The ductoscope can at the same time be used for insufflation, duct lavage, or therapeutic interventions [35]. The use of cytology brushes, small baskets, or microbiopsy forceps ensures targeted sampling. In ductoscopic terms, normal milk duct epithelium is of a pale yellow to pink colour and can have annular folds on the duct wall. Ductoscopy has the advantage that an exact localisation of the pathological finding is possible, ductal lavage can be conducted under direct observation, and intraoperative control is also possible, especially where there is a manifestation of lesions deep within the milk duct system [36]. However, this method only plays a restricted role as it does not provide access to the terminal duct lobular units that are often the origin of malignant lesions. The ductoscopic appearance of intraductal papillomas can range from red to yellow to ashen [37]. Papillomas can extend into the lumen of the milk duct as a polypoid mass where they present as solitary or multiple lesions - a benign mammary tumour in a single milk duct system. In rare cases, papillary lesions can occur in different milk duct systems, both unilateral and bilateral [37].

Therapy

The decision concerning a suitable therapy for intraductal papilloma can be challenging due to the difficult differentiation between intraductal papilloma and carcinoma. Surgical excision is generally recommended in patients with peripheral multiple intraductal lesions and atypical papillomas that are diagnosed based on intraductal breast biopsy [38]. Younger patients with nipple discharge from only 1 milk duct can be successfully treated with a minimal surgical intervention in the form of a microreductomy. In older patients, a radical milk duct excision can be of benefit even if the secretion originates from only 1 milk duct. This gives the opportunity to avoid discharge from other milk ducts and obtain a complete histology.

In keeping with the recommendations made by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie e.V. (AGO Breast Committee, 2018 [38]), no additional measures need to be adopted if papillomas are verified by CB or VAB findings that are not atypical, provided the biopsy material is representative (100 mm2) and findings are consistent. No data currently exists regarding the procedure to be adopted in cases where there is evidence of papilloma in the edges of the resected tissue [39].

Prognosis

The risk of an invasive carcinoma developing in the future in patients with intraductal papilloma (atypical or not) should be evaluated based on the surrounding breast tissue. A benign solitary papilloma without any changes to the surrounding breast tissue indicates only a slightly increased risk of invasive mammary carcinoma developing in the future [38,39]. The relative risk posed by peripheral papillomas can be higher than with central papillomas. Carcinoma risk is based on the ductal and atypical hyperplasias that render the development of carcinoma in the terminal duct lobular units probable in 12% of cases. Recurrences occur in 23% of cases. Papillomas indicate an increased risk of formation of an ipsilateral carcinoma. The percentage rates for atypical papillomas are between 4.6 and 13%. Juvenile papillomatosis appears to be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer simultaneously or in the future [40]. No data currently exists regarding the therapeutic procedure in cases where there is evidence of papilloma in the edges of the resected tissue. Excision should be carried out in the case of juvenile papillomatosis. Close monitoring does not suffice [41].

Mixed Fibroepithelial Tumours

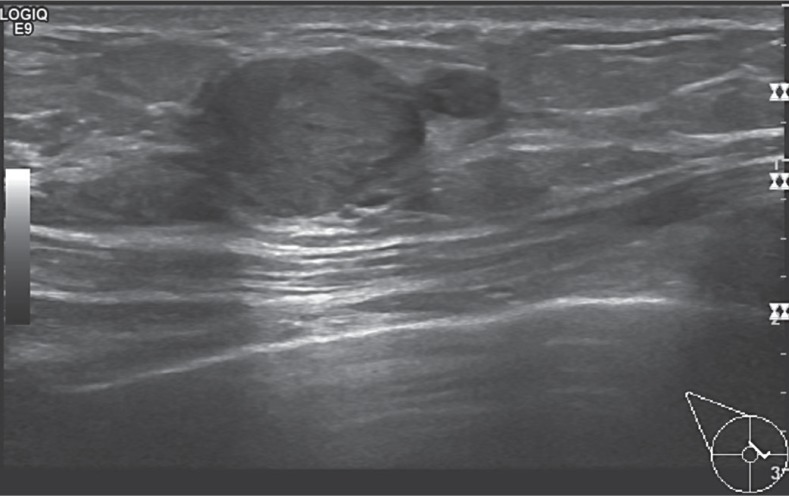

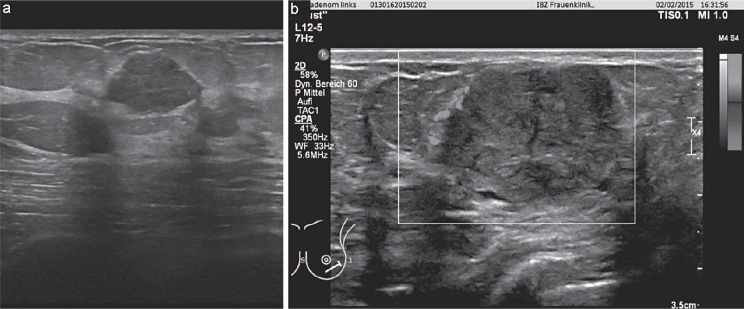

Fibroadenomas

Fibroadenomas are benign biphasic tumours that originate from the terminal duct lobar units as localised tumours and display proliferation of the epithelial and fibrous tissue components (figs. 3, 4) [42,43].

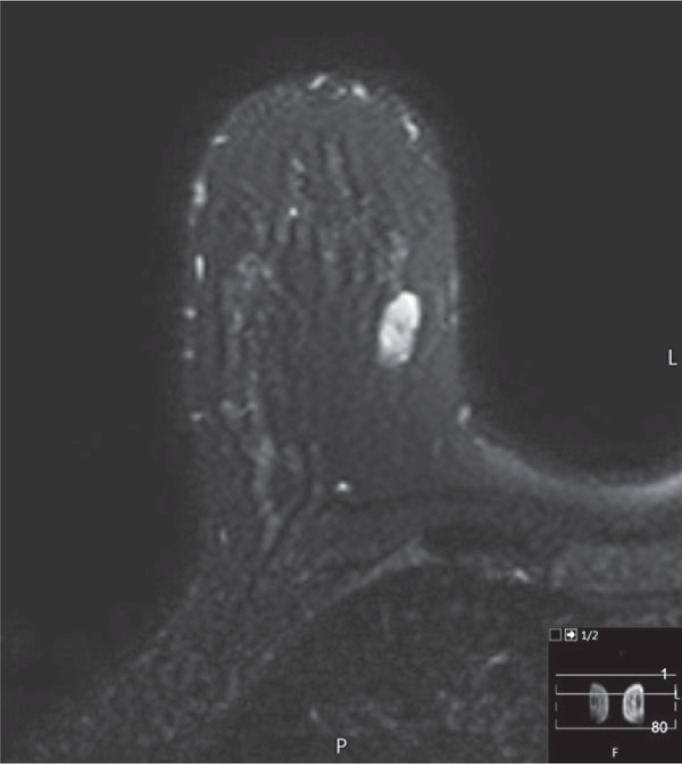

Fig. 3.

a, b Fibroadenoma - sonographic findings.

Fig. 4.

Fibroadenoma - MRI-findings T2-fs sequence; signal intense.

Pathogenesis

It is assumed that fibroadenomas are the result of abnormal proliferation and involution of the breast tissue due to hormonal influences and that they do not present a ‘real’ neoplasia [44].

Terminology

Fibroadenomas are subdivided into [45]:

- adult fibroadenomas that typically manifest in young females

- juvenile fibroadenomas that exist during puberty and in adolescents.

Clinic

Age at Manifestation, Size, and Prevalence

After carcinomas, fibroadenomas are the second most-prevalent neoplasia of the female breast and the most prevalent tumour in females aged under 30 [46]. Their prevalence is reduced to a great extent in the postmenopausal period. The average size is between 1 and 3 cm [45].

Non-Invasive Diagnostics

Palpation

Fibroadenomas present as painless, solitary, solid, smoothly demarcated, slow-growing, and movable nodes.

Mammography

Fibroadenomas normally present on mammography as smooth circumscribed lesions; however, 25% of tumours can include features suspicious for malignancy. Characteristic aspects are complete or almost complete calcification of the fibroadenoma that can have a shell-shaped, popcorn-like, bizarre, or bowl-like form. In the case of pericanalicular fibroadenomas, the calcifications can take a linear, y, or v form. Calcifications in intracanalicular fibroadenomas tend to be rather round or fine-punctiform [47,48,49].

Ultrasound

The classic fibroadenoma has the following ultrasound characteristics [50]:

- an elliptical or slightly lobulated form

- greater elongation in the transversal and craniocaudal image than in the anterior-posterior image

- isoreflective to hyporeflective echotexture when compared with fatty tissue

- completely surrounded by a fine echogenous capsule

- normal or accentuated sonic transmission when compared with the surrounding tissue

- fine boundary shadows

- unrestricted movement during palpation

- easily compressed.

MRI

Fibrosed fibroadenomas uptake only a small quantity of contrast medium or none at all. If a non-cystic tumour presents without any uptake, a T2-weighted pulse sequence should be performed in order to exclude mucinous carcinoma. A fibrous fibroadenoma can therefore be assumed should the signal intensity in the T2-weighted sequence be low. Fibroadenomas with a high water or cell content have a considerable mostly slow but sometimes also fast uptake of the contrast medium and show a smoothly demarcated, oval, and lobulated appearance with low-signal septa. However, peripheral enhancement does not indicate the existence of a fibroadenoma [49].

Minimally Invasive Diagnostics

CB

In the diagnosis of fibroadenoma, CB has the benefit of being able to detect complex changes and epithelial proliferations more easily than FNAC [48,50,51].

VAB

VAB can be a safe and successful alternative when it comes to treating fibroadenomas. In addition to the diagnostic benefits, VAB has therefore also gained importance as a minimally invasive therapeutic method [52,53].

Therapy

It is assumed that fibroadenomas grow over a period of 12 months, increasing in size by around 2–3 cm before remaining unchanged for a number of years. It is also assumed that fibroadenomas tend to regress and lose cell mass the older they become [54]. Should a CB examination therefore detect a fibroadenoma, conservative management with close ultrasound follow-up after 6, 12, and 24 months should be attempted [55,56]. An increase in the size of the fibroadenoma within this interval or the occurrence of symptoms caused by the tumour should serve as an indication for excision biopsy. As the post-interventional cosmetic result plays an important role with benign breast tumours, tumour extirpation is increasingly being carried out using minimally invasive therapeutic procedures as described below [53].

VAB

VAB is an efficient and cost-saving therapeutic procedure with good cosmetic results that is becoming increasingly popular and has developed into the standard management method for the treatment of benign breast tumours. Disadvantages are the probability of recurrence and the possibility that the tumour is not fully extirpated. Complete excision and maximum cosmetic outcome can be achieved with a tumour size of under 3 cm as a standard [57,58].

Cryoablation

This is a method that is almost painless and can be used for superficial lesions. It is therefore the preferred option for patients wishing to have their fibroadenoma treated without surgical intervention. This therapeutic method is deemed to be an effective and safe way of reducing the size and symptoms of the fibroadenoma while achieving excellent cosmetic results. When compared with VAB, it was not possible to detect any recurrences. The analgesic effect of the cold, the procedure-related lack of any changes being discernible on mammographic examination conducted at a later date, and the positive immunostimulatory effect are all deemed to be beneficial [59,60,61,62].

High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is a non-invasive method in which a concentrated ultrasound bundle penetrates and heats the tissue exerting a regional effect. When compared with cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation, this has the advantage that the tissue that is to be destroyed is exactly adapted to the form of the tumour [63,64]. As this is one of the latest therapeutic methods for the treatment of fibroadenomas, a large number of clinical trials are currently being conducted with regard to its effectiveness.

Prognosis

The breast cancer risk in breasts containing or pretreated for fibroadenomas is low, even if a slightly increased risk has been observed [65]. Cases where fibroadenomas have transformed into malignant phyllodes tumours are described in the literature [66,67]. There is an increased risk of malignant degeneration in cases with proliferative changes in the breast parenchyma adjacent to the fibroadenoma or in females with complex fibroadenomas and a positive family history of breast cancer [68]. The majority of fibroadenomas do not recur after complete surgical excision. In younger women, there is a tendency to develop 1 or more new lesions either at the surgical site or in other parts of the body.

Phyllodes Tumour

Phyllodes tumours (described for the first time by Johannes Muller in 1838 [69]) are rare breast neoplasias that only account for 0.3–1% of all mammary tumours [70,71].

Terminology

Due to its cystic components and fleshy appearance, this tumour was originally referred to as ‘cystosarcoma’ . However, taking into account that these tumours display benign behaviour in the majority of the cases, the World Health Organisation recommended the use of the neutral expression ‘phyllodes tumour’ [72].

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of phyllodes tumours is still not clear. In addition to a de novo genesis in the breast parenchyma, emergence from existing fibroadenomas or malignant transformation of a fibroadenoma after radiotherapy are also discussed. Growth-stimulating factors of phyllodes tumours include trauma, lactation, pregnancy, and elevated oestrogen levels [73].

Clinic

Age at Manifestation, Size, and Frequency

In Western countries, phyllodes tumours account for 2.5% of all fibroepithelial breast tumours. The prevalence is predominantly in middle-aged females (incidence peak between age 40 and 50 years). The mean size is 4–5 cm [74].

Microscopy

The histological picture of the phyllodes tumour resembles that of the intracanalicular fibroadenoma. Longitudinal ductal sections are discernible together with a papillary protuberance of the connective tissue, resulting in the tumour having a leaf-like appearance. The existence of epithelial and connective tissue elements is necessary in order to establish the diagnosis. The stroma hereby represents the neoplastic components and determines the pathological behaviour of the tumour. Only the stroma cells are able to metastasise. The histological differentiation between phyllodes tumour and fibroadenoma is based on the proof of the existence of a stroma with a greater number of cells and mitotic activity. Phyllodes tumours are classified as benign, borderline, or malignant depending on their histological characteristics [75,76].

Immunohistology

Immunohistochemical tests have proven the benefit of CD10 expression in differentiating between benign and other forms of phyllodes tumour in addition to estimating the manifestation of distant metastases in connection with mammary phyllodes tumours [77].

Non-Invasive Diagnostics

Palpation

Phyllodes tumours normally present as fast-growing but clinically benign tumours and are frequently located in the upper outer quadrants with a homogenous distribution in both breasts. The skin above larger tumours can show dilated veins and be of a blue colour; nipple retraction is rare. Palpable axillary lymphadenopathy can be detected in up to 20% of patients, but this is seldom the case with regard to lymph node metastases.

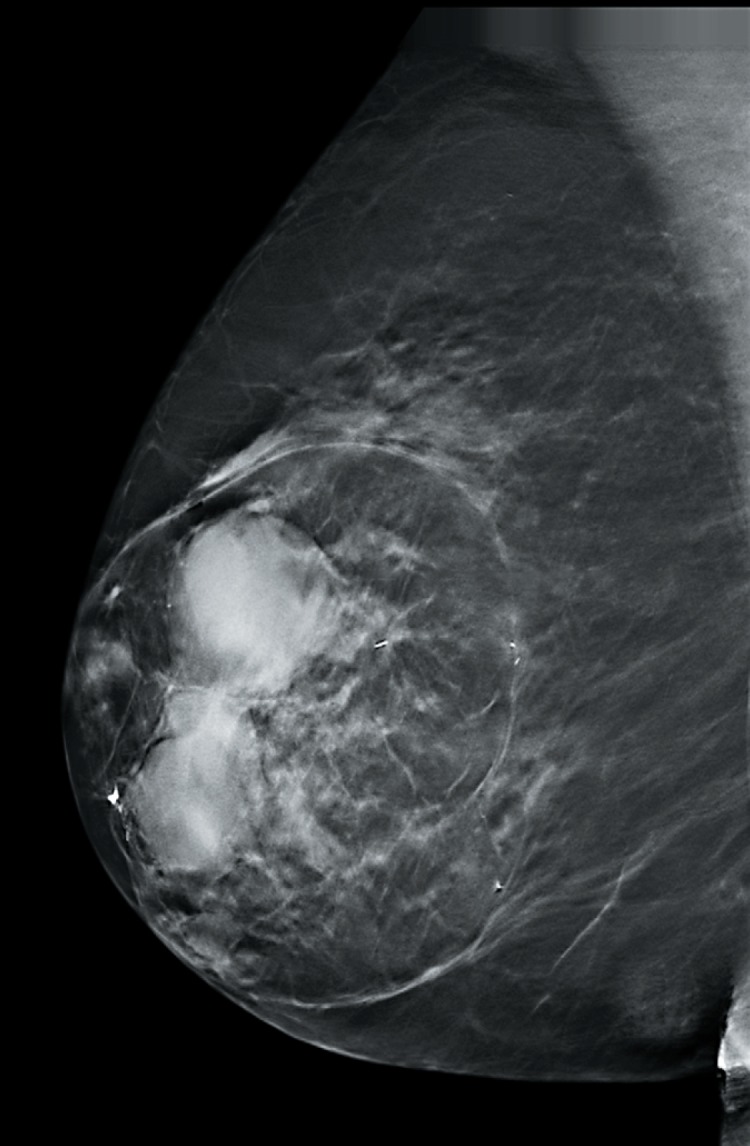

Mammography

On mammography, phyllodes tumours present as smoothly demarcated structures with a smooth and partially lobulated edge [78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86]. A radiotranslucent ring that results from the compression of the surrounding mammary connective tissue can be discerned around the structure [87].

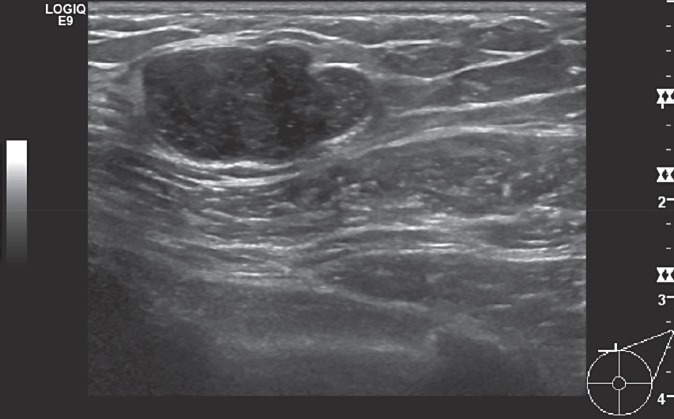

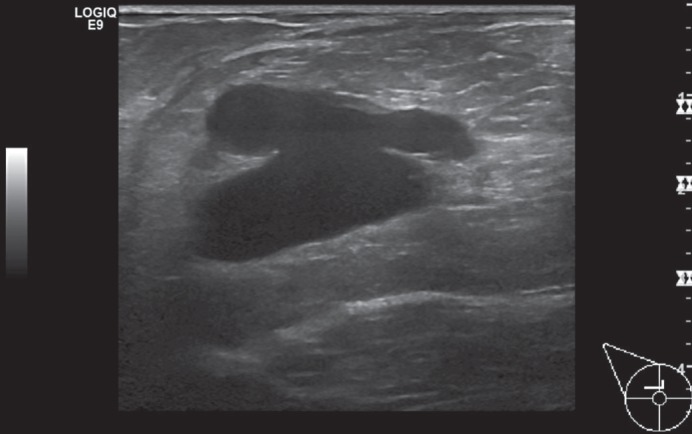

Ultrasound

On ultrasound examination, phyllodes tumours present as solid, smoothly demarcated, and lobulated space-occupying lesions that can include cystic components. However, a reliable differentiation between benign and malignant forms is not possible by ultrasound [88,89] (fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Ultrasound image of a phyllodes tumour in the left breast - sonographic findings.

MRI

The existence of a phyllodes tumour is to be assumed if the following are discernible in the MRI evaluation [90]:

- large structure with a smoothly demarcated edge

- heterogeneous appearance in the T2-weighted sequence

- hyperintense spaces in the T2-weighted fat-saturated and STIR sequences that are filled with fluid

- rapid contrast medium uptake in dynamic imaging without existence of a washout phenomenon

Minimally Invasive Diagnostics

CB

The interdisciplinary S3 Guidelines for the Diagnostic, Therapy and Aftercare of a Mammary Carcinoma recommend classification as ‘B3’ should the punch or vacuum biopsy provide indications for the existence of a phyllodes tumour. In view of the fact that the differentiation from fibroadenoma is impossible, the term ‘fibroepithelial tumour’ should be used in order to avoid a false diagnosis (and in turn an undervaluation of the phyllodes tumour) [91,92]. Although tissue biopsy errors can occur with CB, the selective use of CB is an attractive option when it comes to improving the preoperative diagnosis of phyllodes tumours.

VAB

Only restricted statements on the use of VAB with phyllodes tumours can be found in the current literature. The preoperative diagnosis of phyllodes tumours can be improved by a more frequent use of VAB and CB [93].

Therapy

Local or wide excision is deemed to be the preferred method when treating benign phyllodes tumours. Recurrence of borderline lesions and malignant phyllodes tumours can be reduced by wide excision with tumour-free margins. Diagnostic local excision biopsies or tumour enucleations should be followed up with a definitive wide excision [93]. An annual ultrasound postoperative follow-up examination is generally recommended due to the risk of recurrence.

Prognosis

Phyllodes tumours are classified as benign lesions of uncertain biological potential (B3) [22]. Local recurrences have been described for both benign and malignant phyllodes tumours. The recurring tumour can reflect the histological characteristics of the original tumour or a dedifferentiation (in 75% of cases) [94]. Recurrences generally develop within a period of 2 years. Metastases have been described to occur in almost all inner organs although the majority are detected in the lungs and skeletal system. The highest mortality rate is found during the first 5 years after diagnosis. The frequency of local recurrence and metastasisation correlates with the histological degree of the phyllodes tumours (benign, borderline, malignant). According to published data, the mean value for the general local recurrence tendency of phyllodes tumours is 21%, with 17, 25, and 27% for benign, borderline, and malignant phyllodes tumours, respectively. Metastasisation is generally detected in 10% of cases with a distribution rate of 0, 4, and 22% among benign, borderline, and malignant forms, respectively. Manifestation of local recurrences after surgical excision is heavily dependent on the size of the tumour-free margin zones. Thus, it is recommended that tumour extirpation should be carried out in healthy tissue with a safety margin of 1 cm or preferably even 2 cm [95,96,97,98].

Summary

Phyllodes tumours are rare breast neoplasias that only account for 0.3–1% of all mammary tumours and are mainly occur in middle-aged females. They are classified as being lesions of uncertain biological potential (B3). Up until the late 1970s, mastectomy was the standard surgical procedure for all phyllodes tumours regardless of size and histological type. However, radical surgery did not provide any survival benefits so that conservative surgical methods are used nowadays. A simple intracapsular enucleation (referred to as ‘enucleation of the phyllodes tumour’ ) results in high local recurrence rates regardless of the histological type. Should a diagnosis of phyllodes tumour be established preoperatively, wide excision should be performed with tumour-free margins of at least 1 cm from the normal breast tissue, especially in the case of borderline and malignant tumour forms [98,99,100,101,102,103,104].

However, should the histological picture of a preoperative biopsy not conform with the diagnostic imaging, it is recommended that an open biopsy be initially carried out. It is generally recommended that an annual follow-up with ultrasound examination should be carried out [39].

Benign Mesenchymal Tumours

Hamartoma

Hamartomas (the term was introduced by Arrigoni et al. in 1971 [105]) are localised overgrowths of fibrous, epithelial, and lipoferous elements that normally have an encapsulated appearance [106] (figs. 6, 7).

Fig. 6.

Hamartoma - mammographic findings.

Fig. 7.

Hamartoma - sonographic findings.

Pathogenesis

The genesis of hamartomas is deemed to be a deformity that occurs during embryonic development in the form of inadequate germ tissue differentiation [106,107].

Terminology

The histological variants of hamartoma include [106]:

- adenolipoma

- fibrolipoma

- lipofibroadenoma

- cystadenolipoma.

Clinic

Age at Manifestation, Size, and Frequency

Hamartomas have a predominant manifestation in the perimenopausal age group but may occur at any age. They account for 4.8% of benign breast tumours [108]. Hamartomas present as round or oval lesions and can reach a diameter of up to 20 cm.

Morphology/Microscopy

Hamartomas are encapsulated tumours that can display fibrocystic or atrophic changes; there is a frequent occurrence of pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia [108].

Non-Invasive Diagnostics

Palpation

Hamartomas are frequently asymptomatic and are detected on mammography as an incidental finding. Very large lesions can cause breast deformation.

Mammography

The majority of hamartomas show a characteristic picture in the mammographic examination so that mammography is deemed to be the preferred diagnostic method. They present as smoothly demarcated masses with a different composition of the fat, glandular, and connective tissue content in quantitative terms. The manifestation of the mammographic density varies and depends on the fat/parenchyma ratio [109]. The thin pseudocapsule is fully or partially discernible (fig. 6).

Ultrasound

Ultrasound should only be used for the diagnosis of hamartomas in conjunction with mammographic findings. Breast hamartomas display a wide range of ultrasound features so that ultrasound only plays a minor role in the diagnosis [110]. Frequently, a smoothly demarcated, solid, and poorly echogenic structure with dorsal sound disappearance is discernible (fig. 7).

MRI

On MRI, hamartomas present as compact fatty tissue with a smoothly demarcated, hypointense border and inner heterogenic uptake as characteristic for breast hamartoma [111].

Minimally Invasive Diagnostics

CB

CB is of limited use, especially in cases where clinical and imaging clues do not exist. The existence of connective tissue within the lobuli or a connective tissue and fat content in the stroma, whether with or without pseudoangiomatous changes, should provide the pathologist with grounds for considering the possibility of a hamartoma [111,112].

Therapy

Lesions with a characteristic appearance and typical clinical features of a classic hamartoma can be subjected to conservative therapy. Should the tumour present atypical characteristics however, e.g., an increase in size or specific symptoms, excision or at least a biopsy are recommended [113,114,115].

Prognosis

Hamartomas are benign breast lesions but malignant transformation is possible [116]. The literature describes in situ ductal carcinomas, infiltrating ductal carcinomas, and lobular intraepithelial neoplasias in conjunction with hamartomas [114,115,116,117]. Hamartomas do not tend to recur.

Discussion

Histological evaluation is the most certain diagnostic method for benign breast tumours. According to the S3 Guideline and information gained from the literature analysis, preference is to be given to high-speed biopsy (i.e., CB) in each tumour entity [118]. FNAC should no longer be used as standard.

Only a small amount of information or no information at all could be found in the literature regarding the use of VAB, especially for the very rare tumours; hence, the future significance of this method in the diagnosis of rare benign tumours remains to be seen. In the case of certain tumours such as adenomyoepitheliomas, the use of VAB is recommended before CB [119]. Milk duct papillomas play a special role here as not only standard biopsy methods are used for diagnosis and possibly therapy but also ductoscopy. It can be determined from the literature that intraductal papilloma, phyllodes tumour, neurofibroma, and solitary fibrous tumour are the most frequently occurring tumours with a tendency to transform or metastasise. Whereas there is a trend in the literature toward surgical therapy of all forms of phyllodes tumour (benign, borderline, or malignant), the literature regarding intraductal papillomas continues to point toward a possible follow-up behaviour versus operative therapy [120]. The AGO recommends conservative management of solitary papillomas without any atypical characteristics (if biopsy is conclusive and conforms with the imaging) and the performance of an open biopsy for atypical papillomas.

With regard to solitary fibrous tumours, operative therapy is the preferred method due to the possible malignant potential [121].

A general recommendation for an open biopsy should therefore be made in cases of benign solid tumours of the breast with a known increased tendency to transform and metastasise or an unclear biological behaviour (B3 lesions). This excludes solitary papillomas without atypical characteristics. In the case of all other benign breast tumours, management could be in the form of a conservative procedure with annual ultrasound follow-up examinations after a clinical examination, use of corresponding imaging procedures, and last but not least the performance of a punch biopsy to verify the diagnosis. The indication for an open biopsy is also to be established should the tumour increase in size in the follow-up interval, after recurring discrepancies in the punch or vacuum biopsy results, or at the request of the patient. As an alternative, minimally invasive procedures such as therapeutic VAB, cryoablation, or HIFU are also becoming possible alternatives in the definitive surgical management.

The newer minimally invasive methods show an adequate degree of accuracy and hardly any restrictions in terms of post-interventional cosmetics, so that current requirements of extensive breast imaging can be thoroughly met.

Disclosure Statement

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.D'Orsi CJ, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013. ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madjar C, Seabert J, Fisseler-Eckhoff A. Relevance of B3 lesions in breast diagnosis - frequency and therapeutic consequences. Senologie. 2018;15:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warren JC. The surgeon and the pathologist. JAMA. 1905;45:149–165. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liberman L, Bracero N, Vuolo MA. Percutaneous large-core biopsy of papillary breast lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:331–337. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.2.9930777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutman H, Schachter J, Wasserberg N. Are solitary breast papillomas entirely benign? Arch Surg. 2003;138:1330–1333. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.12.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Sarakbi W, Worku D, Escobar PF, Mokbel K. Breast papillomas: current management with a focus on a new diagnostic and therapeutic modality. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2006;3:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohuchi N, Abe R, Takahashi T, Tezuka F. Origin and extension of intraductal papillomas of the breast: a three-dimensional reconstruction study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1984;4:117–128. doi: 10.1007/BF01806394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guray M, Sahin AA. Benign breast diseases: classification, diagnosis, and management. Oncologist. 2006;11:435–449. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-5-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen PP, Holmes G, Lesser ML. Juvenile papillomatosis and breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1985;55:1345–1352. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850315)55:6<1345::aid-cncr2820550631>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bazzocchi F, Santini D, Martinelli G. Juvenile papillomatosis (epitheliosis) of the breast. A clinical and pathologic study of 13 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1986;86:745–748. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/86.6.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muttarak M, Lerttumnongtum P, Chaiwun B, Peh WC. Spectrum of papillary lesions of the breast: clinical, imaging and pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:700–707. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter D. Intraductal papillary tumors of the breast: a study of 78 cases. Cancer. 1977;39:1689–1692. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197704)39:4<1689::aid-cncr2820390444>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods ER, Helvie MA, Ikeda DM. Solitary breast papilloma: comparison of mammographic, galactographic, and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:487–491. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.3.1503011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardenosa G, Eklund GW. Benign papillary neoplasms of the breast: mammographic findings. Radiology. 1991;181:751–755. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.3.1947092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piccoli CW, Feig SA, Vala MA. Breast imaging case of the day. Benign intraductal papilloma with focal atypical papillomatous hyperplasia. Radiographics. 1998;18:783–786. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.3.9599399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganesan S, Karthik G, Joshi M, Damodaran V. Ultrasound spectrum in intraductal papillary neoplasms of breast. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:843–849. doi: 10.1259/bjr/69395941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han BK, Choe YH, Ko YH. Benign papillary lesions of the breast: sonographic-pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 1999;18:217–223. doi: 10.7863/jum.1999.18.3.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi JJ, Kang BJ, Kim SH. Role of sonographicelastography in the differential diagnosis of papillary lesions in breast. Jpn J Radiol. 2012;30:422–429. doi: 10.1007/s11604-012-0070-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniel BL, Gardner RW, Birdwell RL. Magnetic resonance imaging of intraductal papilloma of the breast. Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;21:887–892. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(03)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mokbel K, Elkak AE. Magnetic resonance imaging for screening of woman at high risk for hereditary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4184. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.21.4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Son EJ, Kim EK, Kim JA. Diagnostic value of 3D fast low-angle shot dynamic MRI of breast papillomas. Yonsei Med J. 2009;50:838–844. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2009.50.6.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee AHS, Carder P, Deb R. London: The Royal College of Pathologists; 2016. Guidelines for Non-Operative Diagnostic Procedures and Reporting in Breast Cancer Screening; pp. pp.18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amendoeira I, Apostolikas N, Bellocq JP, Wells CA, Quality assurance guidelines for pathology . Cytological and histological non-operative procedures. In: Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis, editors. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2006. pp. pp. 221–255. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leithner D, Kaltenbach B, Hödl P. Intraductal papilloma without atypia on image-guided breast biopsy: upgrade rates to carcinoma at surgical excision. Breast Care (Basel) 2018;13:364–368. doi: 10.1159/000489096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bekes I, deGregorio A, deWaal A. Review on current treatment options for lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3 lesions) of the breast: do B3 papillary lesions need to be removed in any case by open surgery? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4985-0. DOI: 10.1007/s00404-018-4985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosen EL, Bentley RC, Baker JA, Soo MS. Imaging-guided core needle biopsy of papillary lesions of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1185–1192. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.5.1791185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Philpotts LE, Shaheen NA, Jain KS. Uncommon high-risk lesions of the breast diagnosed at stereotactic core-needle biopsy: clinical importance. Radiology. 2000;216:831–837. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00se31831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agoff SN, Lawton TJ. Papillary lesions of the breast with and without atypical ductal hyperplasia: can we accurately predict benign behaviour from core needle biopsy? Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:440–443. doi: 10.1309/NAPJ-MB0G-XKJC-6PTH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sydnor MK, Wilson JD, Hijaz TA. Underestimation of the presence of breast carcinoma in papillary lesions initially diagnosed at core-needle biopsy. Radiology. 2007;242:58–62. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2421031988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renshaw AA, Derhagopian RP, Tizol-Blanco DM, Gould EW. Papillomas and atypical papillomas in breast core needle biopsy specimens: risk of carcinoma in subsequent excision. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:217–221. doi: 10.1309/K1BN-JXET-EY3H-06UL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rizzo M, Lund MJ, Oprea G. Surgical follow-up and clinical presentation of 142 breast papillary lesions diagnosed by ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1040–1047. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9780-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dennis MA, Parker S, Kaske TI. Incidental treatment of nipple discharge caused by benign intraductal papilloma through diagnostic Mammotome biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1263–1268. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.5.1741263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohlinger R, Grunwald S. Duktoskopie: Lehratlas zur endoskopischen Milchgangsspiegelung. In: Römer T, Ebert AD, Frauenärztliche Taschenbücher, editors. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter; 2009. pp. pp. 13–488. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mokbel K, Escobar PF, Matsunaga T. Mammary ductoscopy: current status and future prospects. Eur J Sur Oncol. 2005;31:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dietz JR, Crowe JP, Grundfest S. Directed duct excision by using mammary ductoscopy in patients with pathologic nipple discharge. Surgery. 2002;132:582–588. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.127672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen KW, Wu J, Lu JS. Fiberoptic ductoscopy for breast cancer patients with nipple discharge. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1340–1345. doi: 10.1007/s004640080108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsunaga T, Kawakami Y, Namba K, Fujii M. Intraductal biopsy for diagnosis and treatment of intraductal lesions of the breast. Cancer. 2004;101:2164–2169. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liedtke C, Jackisch C, Thill M. AGO recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with early breast cancer: update 2018. Breast Care (Basel) 2018;13:196–208. doi: 10.1159/000489329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiaer HW, Kiaer WW, Linell F, Jacobsen S. Extreme duct papillomatosis of the juvenile breast. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1979;87:353–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1979.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohlinger R, Schwesinger G, Schimming A. Juvenile papillomatosis (JP) of the female breast (Swiss cheese disease) - role of breast ultrasonography. Ultraschall in Med. 2005;26:42–45. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-813122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cooper A. Illustrations of the diseases of the female breast. Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. 1829;32:17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan PH, Tse G, Lee A, et al. Fibroepithelial tumours. In: Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, et al.WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast, editors. ed 4. Lyon: IARC; 2012. pp. pp. 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dent DM, Cant PJ. Fibroadenoma. World J Surg. 1989;13:706–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01658418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Remmele W, Bässler R, Dallenbach-Hellweg G, et al. Pathologie 4: Weibliches Genitale . Endokrine Organe. Berlin: Springer; 1997. Mamma. Pathologie der Schwangerschaft, der Plazenta und des Neugeborenen. Infektionskrankheiten des Fetus und des Neugeborenen. Tumoren des Kindesalters; pp. pp. 209–212. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu XF, Zhang JX, Zhou Q. A clinical study on the resection of breast fibroadenoma using two types of incision. Scand J Surg. 2011;100:147–152. doi: 10.1177/145749691110000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pistolese CA, Tosti D, Citraro D. Probably benign breast nodular lesions (BI-RADS 3): correlation between ultrasound features and histologic findings. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.09.004. DOI: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bottles K, Chan JS, Holly EA. Cytologic criteria for fibroadenoma. A step-wise logistic regression analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;89:707–713. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/89.6.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heywang-Köbrunner S, Schreer I, editors. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme; 2015. Bildgebende Mammadiagnostik: Untersuchungstechnik, Befundmuster, Differenzialdiagnose und Interventionen; pp. pp. 292–360. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stavros AT, Rapp CL, Parker SH. Breast Ultrasound. Philadelphia, PA Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004:p. 1015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuijper A, Mommers EC, van der Wall E, van Diest PJ. Histopathology of fibroadenoma of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115:736–742. doi: 10.1309/F523-FMJV-W886-3J38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathew J, Crawford DJ, Lwin M. Ultrasound-guided, vacuum-assisted excision in the diagnosis and treatment of clinically benign breast lesions. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:494–496. doi: 10.1308/003588407X187621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lakoma A, Kim ES. Minimally invasive surgical management of benign breast lesions. Gland Surgery. 2014;3:142–148. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2014.04.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greenberg R, Skornick Y, Kaplan O. Management of breast fibroadenomas. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:640–645. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.cr188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haagensen CD. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 1996. Disease of the Breast; pp. pp. 267–283. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pruthi S, Jones KN. Nonsurgical management of fibroadenoma and virginal breast hypertrophy. Semin Plast Surg. 2013;27:62–66. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1343997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vlastos G, Verkooijen HM. Minimally invasive approaches for diagnosis and treatment of early-stage breast cancer. Oncologist. 2007;12:1–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luo HJ, Chen X, Tu G. Therapeutic application of ultrasound-guided 8-gauge Mammotome system in presumed benign breast lesions. Breast J. 2011;17:490–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Littrup PJ, Freeman-Gibb L, Andea A. Cryotherapy for breast fibroadenomas. Radiology. 2005;234:63–72. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341030931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaufman CS, Littrup PJ, Freeman-Gibb LA. Office-based cryoablation of breast fibroadenomas with long-term follow-up. Breast J. 2005;11:344–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hahn M, Pavlista D, Danes J. Ultrasound guided cryoablation of fibroadenomas. Utraschall Med. 2013;34:64–68. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bland KL, Gass J, Klimberg VS. Radiofrequency, cryoablation, and other modalities for breast cancer ablation. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mahnken AH, König AM, Figiel JH. Current technique and application of percutaneous cryotherapy. Rofo. 2018;190:836–846. doi: 10.1055/a-0598-5134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Papathemelis T, Heim S, Lux MP. Minimally invasive breast fibroadenoma excision using an ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted biopsy device. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77:176–181. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-100387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dupont WD, Page DL, Parl FF. Long-term risk of breast cancer in women with fibroadenoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:10–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407073310103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pacchiarotti A, Selman H, Gentile V. First case of transformation for breast fibroadenoma to high-grade malignant phyllodes tumor in an in vitro fertilization patient: misdiagnosis of recurrence, treatment and review of the literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2495–2498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abe M, Miyata S, Nishimura S. Malignant transformation of breast fibroadenoma to malignant phyllodes tumor: long-term outcome of 36 malignant phyllodes tumors. Breast Cancer. 2011;18:268–272. doi: 10.1007/s12282-009-0185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Greenberg R, Skornick Y, Kaplan O. Management of breast fibroadenomas. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:640–645. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.cr188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levi F, Randimbison L, Te VC, La Vecchia C. Incidence of breast cancer in women with fibroadenoma. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:681–683. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Müller J. Ueber den feinern Bau und die Formen der krankhaften Geschwülste. In: Reimer G, editor. Berlin. 1838. pp. pp. 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosewell MD, Perry RR, Hsju JG, Barranco SC. Phyllodes tumors. Am J Surg. 1983;165:376–379. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80849-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Komenaka IK, El-Tamer M, Pile-Spellman E, Hibshoosh H. Core needle biopsy as a diagnostic tool to differentiate phyllodes tumor from fibroadenoma. Arch Surg. 2003;138:987–990. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.9.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.International histological classification of tumours histologic types of breast tumours Geneva, WHO. 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tavassoli FA. ed 2. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 1999. Pathology of the Breast; p. p. 573. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Elston CW, Ellis IO. Fibroadenoma and related conditions. In: Elston CW, Ellis IO, The Breast, editors. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Parker SJ, Harries SA. Phyllodes tumours. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:428–435. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.909.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fernandez BB, Hernandez FJ, Spindler W. Metastatic cystosarcoma phyllodes, a light and electron microscopic study. Cancer. 1976;37:1737–1746. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197604)37:4<1737::aid-cncr2820370419>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Al-Masri M, Darwazeh G, Sawalhi S. Phyllodes tumor of the breast: role of CD10 in predicting metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;19:1181–1184. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aranda FI, Laforga JB, Lopez JL. Phyllodes tumor of the breast. An immunhistochemical study of 28 cases with special attention to the role of myofibroblast. Pathol Res Pract. 1994;190:474–481. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jacklin RK, Ridgway PF, Ziprin P. Optimising preoperative diagnosis in phyllodes tumour of the breast. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:454–459. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.025866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chua CL, Thomas A, Ng BK. Cystosarcoma phyllodes: a review of surgical options. Surgery. 1989;105:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stebbing JF, Nash AG. Diagnosis and management of phyllodes tumour of the breast: experience of 33 cases at a specialist centre. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1995;77:181–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Umpleby HC, Moore I, Royle GT. An evaluation of the preoperative diagnosis and management of cystosarcoma phyllodes. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1989;71:285–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bartoli C, Zurrida S, Veronesi P. Small sized phyllodes tumor of the breast. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1990;16:215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reinfuss M, Mitus J, Duda K. The treatment and prognosis of patients with phyllodes tumor of the breast: an analysis of 170 cases. Cancer. 1996;77:910–916. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960301)77:5<910::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Norris HJ, Taylor HR. Relationship of histological features to behavior of cystosarcoma phyllodes. Cancer. 1967;20:2090–2099. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196712)20:12<2090::aid-cncr2820201206>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vorherr H, Vorherr UF, Kutvirt DM, Key CR. Cystosarcoma phyllodes: epidemiology, pathohistology, pathobiology, diagnosis, therapy and survival. Arch Gynecol. 1985;236:173–181. doi: 10.1007/BF02133961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Buchberger W, Strasser K, Heim K. Phylloides tumor: findings on mammography, sonography and aspiration cytology in 10 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:715–719. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.4.1654022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Page JE, Williams JE. The radiological features of phyllodes tumour of the breast with clinico-pathological correlation. Clin Radiol. 1991;44:8–12. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goel NB, Knight TE, Pandey S. Fibrous lesions of the breast: imaging-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2005;25:1547–1559. doi: 10.1148/rg.256045183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Balaji R, Ramachandran KN. Magnetic resonance imaging of a benign phyllodes tumor of the breast. Breast Care (Basel) 2009;4:189–191. doi: 10.1159/000220604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Patrascu A, Popescu CF, Plesea IE. Clinical and cytopathological aspects in phyllodes tumors of the breast. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2009;50:605–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jacklin RK, Ridgway PF, Ziprin P. Optimising preoperative diagnosis in phyllodes tumour of the breast. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:454–459. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.025866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ouyang Q, Li S, Tan C. Benign phyllodes tumor of the breast diagnosed after ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted biopsy: surgical excision or wait-and-watch? Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1129–1134. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4990-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sotheran W, Domjan J, Jeffrey M. Phyllodes tumours of the breast - a retrospective study from 1982–2000 of 50 cases in Portsmouth. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87:339–344. doi: 10.1308/003588405X51128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grimes MM. Cystosarcoma phyllodes of the breast: histologic features, flow cytometric analysis, and clinical correlations. Mod Pathol. 1992;5:232–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moffat CJ, Pinder SE, Dixon AR. Phyllodes tumours of the breast: a clinico-pathological review of thirty two cases. Histopathology. 1995;27:205–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1995.tb00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barth RJ., Jr Histologic features predict local recurrence after breast conserving therapy of phyllodes tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;57:291–295. doi: 10.1023/a:1006260225618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen WH, Cheng SP, Tzen CY. Surgical treatment of phyllodes tumors of the breast: retrospective review of 172 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:185–194. doi: 10.1002/jso.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dyer NH, Bridger JE, Taylor RS. Cystosarcoma phylloides. Br J Surg. 1966;53:450–455. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800530517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maier WP, Rosemond GP, Wittenberg P, Tassoni EM. Cystosarcoma phyllodes mammae. Oncology. 1968;22:145–158. doi: 10.1159/000224446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cohn-Cedermark G, Rutqvist LE, Rosendahl I, Silfverswärd C. Prognostic factors in cystosarcoma phyllodes. A clinicopathologic study of 77 patients. Cancer. 1991;68:2017–2022. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911101)68:9<2017::aid-cncr2820680929>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Contarini O, Urdaneta LF, Hagan W, Stephenson SE., Jr Cystosarcoma phylloides of the breast: a new therapeutic proposal. Am Surg. 1982;48:157–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hajdu SJ, Espinosa MH, Robbins GF. Recurrent cystosarcoma phyllodes: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases. Cancer. 1976;38:1402–1406. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197609)38:3<1402::aid-cncr2820380346>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mangi AA, Smith BL, Gadd MA. Surgical management of phyllodes tumors. Arch Surg. 1999;134:487–492. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Arragoni MG, Dockerty MB, Judd ES. The identification and treatment of mammary hamartoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1971;133:577–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Choi N, Ko ES. Invasive ductal carcinoma in a mammary hamartoma: case report and review of the literature. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11:687–691. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2010.11.6.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lanyi M. Berlin: Springer; 2003. Brustkrankheiten im Mammogramm; pp. pp. 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schrager CA, Schneider D, Gruener AC. Clinical and pathological features of breast disease in Cowden's syndrome: an under recognized syndrome with an increased risk of breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Charpin C, Mathoulin MP, Andrac L. Reappraisal of breast hamartomas. A morphological study of 41 cases. Pathol Res Pract. 1994;190:362–371. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wahner-Roedler DL, Sebo TJ, Gisvold JJ. Hamartomas of the breast: clinical, radiologic and pathologic manifestations. Breast J. 2001;7:101–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2001.007002101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Adler DD, Jeffries DO, Helvie MA. Sonographic features of breast hamartomas. J Ultrasound Med. 1990;9:85–90. doi: 10.7863/jum.1990.9.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tse GM, Law BK, Ma TK. Hamartoma of the breast: a clinicopathological review. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:951–954. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.12.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Heywang-Köbrunner SH, Heinig A, Hellerhoff K. Use of ultrasound-guided percutaneous vacuum-assisted breast biopsy for selected difficult indications. Breast J. 2009;15:348–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mester J, Simmons RM, Vazquez MF, Rosenblatt R. In situ and infiltrating ductal carcinoma arising in a breast hamartoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:64–66. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.1.1750064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Anani PA, Hessler C. Breast hamartoma with invasive ductal carcinoma. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 1996;192:1187–1194. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(96)80149-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Barbaros U, Deveci U, Erbil Y, Budak D. Breast hamartoma: a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2005;105:658–659. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2005.11679798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Coyne J, Hobbs FM, Boggis C, Harland R. Lobular carcinoma in a mammary hamartoma. J ClinPathol. 1992;45:936–937. doi: 10.1136/jcp.45.10.936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Albert U-S. Stufe-3-Leitlinie Brustkrebs-Früherkennung in Deutschland. München-Wien-New York, W. Zuckschwerdt. 2008:pp. 1–353. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yahara T, Yamaguchi R, Yokoyama G. Adenomyoepithelioma of the breast diagnosed by a mammotome biopsy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2008;38:144–146. doi: 10.1007/s00595-007-3591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rozentsvayg E, Carver K, Borkar S. Surgical excision of benign papillomas diagnosed with core biopsy: a community hospital approach. Radiol Res Pract Epub. 2011:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2011/679864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Van Kints MJ, Tham RT, Klinkhamer PJ, van den Bosch HC. Hemangiopericytoma of the breast: mammographic and sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:61–63. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.1.8010249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]