Abstract

Background

Few studies have assessed smoking and obesity together as risk factors for frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Objective

To study smoking and obesity as risk factors for FTD and AD.

Methods

Ninety patients with FTD and 654 patients with AD were compared with 116 cognitively healthy elderly individuals in a longitudinal design with 15–31 years between measurements of risk factors before the dementia diagnosis.

Results

There were no associations between smoking and FTD (p = 0.218; odds ratio [OR]: 0.990; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.975–1.006). There were significant associations between obesity and FTD (p = 0.049; OR: 2.629; 95% CI: 1.003–6.894). There were significant associations between both smoking (p = 0.014; OR: 0.987; 95% CI: 0.977–0.997) and obesity (p = 0.015; OR: 2.679; 95% CI: 1.211–5.928) and AD.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that obesity is a shared risk factor for FTD and AD, while smoking plays various roles as a risk factor for FTD and AD.

Key Words: Longitudinal studies, Case-control studies, Dementia, Frontal lobe, Neurodegenerative diseases, Epidemiology, Psychiatric symptoms

Introduction

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is considered to be a common cause of dementia in younger adults [1, 2], yet very few studies have investigated modifiable risk factors for FTD [3]. FTD is a neurodegenerative disease leading to loss of neurons in the frontal and/or temporal lobes in the brain [4, 5, 6]. This results in severe neuropsychiatric symptoms such as changes in behavior and personality and changes in language use [7, 8]. About 60% of FTD cases are diagnosed between the ages of 45 and 60 years [1]. No curative treatment for FTD exists today, but identification of modifiable risk factors may lead to viable prevention strategies [9].

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia [10, 11]. Early symptoms are known to be memory deficits, apathy, and depression [11, 12]. Later symptoms include problems in communication, confusion, behavioral changes, and disorientation [11]. For AD, medical treatment may delay the progression of the disease, and modifiable risk factors have been extensively investigated [13].

Some studies have found associations between FTD and diabetes mellitus [14], head trauma [15, 16, 17], education level [18], autoimmune disease [19], and anxiety [20]. When it comes to AD, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, increased body mass index (BMI), lower education, lower socioeconomic status, depression, affective disorders, poor social network, lower social engagement, and smoking are all well-known risk factors [13, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]. To our knowledge, very few studies have investigated modifiable risk factors in FTD compared with AD. It is important to investigate similarities and differences when it comes to modifiable risk factors for these diseases because the findings may aid researchers in exploring new concepts in prevention and treatment.

Tobacco use and obesity are among the leading risks for mortality in the world [26]. Smoking is a well-known risk factor for dementia [25, 27], and it has been hypothesized that it can lead to dementia indirectly through cerebrovascular disease, stroke, heart disease, increased total plasma homocysteine, atherosclerosis, and oxidative stress [25]. A decrease in smoking has been seen in some high-income countries, but the numbers of smokers are still increasing in many low- and middle-income countries [26].

Obesity is associated with an increased risk for dementia [13, 27, 28] by mechanisms that include insulin resistance diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, increased inflammation, and higher levels of cytokines [28]. The prevalence of obesity has been increasing for several years [29], with the highest average BMI in Europe, America, and the eastern Mediterranean countries [26].

The aim of this longitudinal population-based case-control study was to examine modifiable risk factors for FTD and to investigate the role of smoking and obesity as modifiable risk factors in FTD compared with AD.

Methods

Study Population

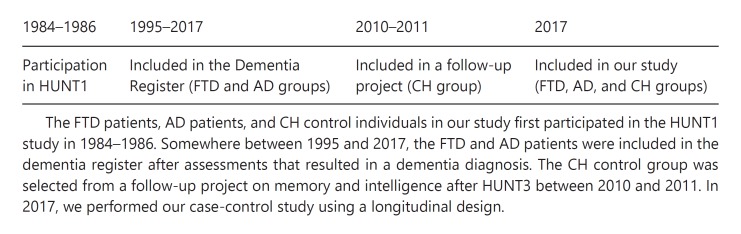

We performed a population-based, longitudinal nested case-control study. The study population consisted of 90 patients with FTD, 654 patients with AD, and a control group of 116 verified cognitively healthy (CH) elderly individuals (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The study population. AD, Alzheimer's disease; CH, cognitively healthy; FTD, frontotemporal dementia.

Cases with FTD and AD diagnoses were identified from the dementia register of North-Trøndelag Hospital Trust, Norway (Fig. 1). This dementia register consists of data collected from two registers: the Nursing Home Dementia Register and the Hospital Dementia Register [30]. The CH control group was selected from a follow-up project on memory and intelligence after HUNT3 between 2010 and 2011 [31] (Fig. 1). During this project, individuals were examined by a neuropsychologist and categorized as CH [31]. All cases and controls in this study participated in the first study of the North-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT1) between 1984 and 1986. In the HUNT1 study, participants underwent a brief medical examination and were asked to complete questionnaires including physical and mental health-related items. The HUNT1 study has been described in more detail previously [32].

FTD and AD patients and CH individuals with valid data on smoking habits and obesity were included in our study. Cases and controls with missing data on smoking habits or obesity were excluded.

Dementia Diagnosis

The data on dementia diagnosis in the Hospital Dementia Register were collected retrospectively (1995–2010) and prospectively (2010–2017). The diagnosis was made by spe cialists in geriatric and psychogeriatric medicine according to national and international guidelines. Diagnoses were based on patient history, caregiver history, clinical examinations, neuropsychological assessments, blood samples, and brain imaging [20, 30].

The Nursing Home Dementia Register consists of data on dementia diagnoses collected from nursing homes in North-Trøndelag in 2010–2011. The data were collected by trained nurses who collected the diagnostic data by conducting tests, measuring cognitive function, neuropsychiatric symptoms, depression symptoms, quality of life, caregiver distress, and personal activities of daily living. Two physicians with wide clinical and research experience independently diagnosed mild cognitive impairment, dementia syndromes, and dementia subtypes. A third expert was consulted if there was any discrepancy [20, 30].

Smoking and Obesity Measurements

Data on smoking and obesity were extracted from the HUNT1 study. The participants in HUNT1 completed self-reporting questionnaires with items on smoking status. The questions were never smoked daily, previously daily smoker, and current daily smoker. In our study, previous daily smoker or daily smoker were categorized as “smoking” and never smoked daily as nonsmoking. The participants in HUNT1 were measured for height and weight (height to the nearest cm, weight to the nearest half kg), and BMI was calculated and documented. We classified patients with a BMI ≥30 as obese.

Confounders

Confounding factors were drawn from the HUNT1 study. We selected variables that might confound the associations between smoking/obesity and FTD/AD. Confounders can influence both the dependent and the independent variable, causing a spurious association. The confounders considered relevant for this study were sex, age at participation in HUNT1, heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension. Heart disease was ascertained if participants indicated that they had experienced angina pectoris or a heart attack. Similarly, diabetes was determined if responses were positive. Hypertension was determined if participants had an average diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm Hg.

Statistical Analyses

Datasets from the dementia register of North-Trøndelag Hospital Trust and the HUNT1 study were merged using the personal identification number assigned to all Norwegian citizens. The personal identification number was then replaced with an anonymous project identification number before the merged dataset was made available to the researchers. We evaluated the association between smoking and obesity as measured in HUNT1 and the later development of FTD and AD using multivariable logistic regression. Three analyses were performed independently: (1) analysis of FTD patients versus CH individuals, (2) analysis of FTD patients versus AD patients, and (3) analysis of AD patients versus CH individuals. All of the analyses were performed in four steps: (1) smoking as the only variable, (2) obesity as the only variable, (3) smoking and obesity as the only variables, and (4) smoking and obesity as variables adjusted for the potential confounders of age, sex, heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension. The analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

The FTD and AD groups were older at participation in HUNT1 and were more likely to have heart disease and hypertension than the CH group. The FTD group had a lower mean age at the time of dementia diagnosis than the AD group, and 14.4% in the FTD group and 14.7% in the AD group had obesity as a risk factor compared to 6.0% in the CH group, while 47.8% in the FTD group and 39.9% in the AD group had smoking as a risk factor compared to 46.6% in the CH group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| FTD | AD | CH | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of individuals | 90 | 654 | 116 |

| Female, % | 70 | 69 | 52.6 |

| Mean age at participation in HUNT1 | 56.6 | 60.7 | 49.1 |

| Mean age at dementia diagnosis | 74.4 | 79.2 | |

| Risk factors present, % | |||

| Heart disease | 2.2 | 4.1 | 0.9 |

| Diabetes | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.7 |

| Hypertension | 31.1 | 37.3 | 30.2 |

| Smoking | 47.8 | 39.9 | 46.6 |

| Obesity | 14.4 | 14.7 | 6.0 |

AD, Alzheimer's disease; CH, cognitively healthy; FTD, frontotemporal dementia.

All cases in the FTD group received their dementia diagnosis after the year 2000. In the AD group, 26 cases received their dementia diagnosis between 1995 and 1999 and the remainder after the year 2000.

FTD Patients Compared to CH Individuals

In the initial analysis entering only smoking as the variable, no significant association between smoking and FTD development was seen (p = 0.218; odds ratio [OR]: 0.990; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.975–1.006) compared with the CH group. When entering only obesity as the variable, a significant association between obesity and FTD development was seen (p = 0.049; OR: 2.629; 95% CI: 1.003–6.894). When both smoking and obesity were entered as variables, a nearly significant increase in the risk of FTD development was observed for obesity (p = 0.064; OR: 2.496; 95% CI: 0.947–6.582). There was no significant association between smoking and the risk of developing FTD (p = 0.302; OR: 0.992; 95% CI: 0.977–1.007). After adjusting for the potential confounders, there were no associations between smoking or obesity and FTD development (Table 2).

Table 2.

FTD patients versus CH individuals

| p value | OR | 95% CI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lower | upper | |||

| Smokinga | 0.218 | 0.990 | 0.975 | 1.006 |

| Obesityb | 0.049 | 2.629 | 1.003 | 6.894 |

| Smokingc | 0.302 | 0.992 | 0.977 | 1.007 |

| Obesityc | 0.064 | 2.496 | 0.947 | 6.582 |

| Adjusted analysisd | ||||

| Smoking | 0.767 | 0.997 | 0.980 | 1.015 |

| Obesity | 0.200 | 2.046 | 0.685 | 6.107 |

| Age at participation in HUNT1 | 0.000 | 1.106 | 1.063 | 1.151 |

| Sex | 0.227 | 0.672 | 0.352 | 1.281 |

| Heart disease | 0.630 | 1.834 | 0.156 | 21.619 |

| Diabetes | 0.664 | 0.568 | 0.044 | 7.315 |

| Hypertension | 0.351 | 0.719 | 0.359 | 1.438 |

Smoking and obesity as risk factors for FTD compared with CH. CH, cognitively healthy; CI, confidence interval; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; OR, odds ratio. a Smoking entered as variable. b Obesity entered as a variable. c Smoking and obesity entered as variables. d Smoking, obesity, and confounders entered as variables.

FTD Patients Compared to AD Patients

In the initial analysis entering only smoking as the variable, no significant association between smoking and FTD development was seen (p = 0.600; OR: 1.004; 95% CI: 0.990–1.017) compared with the AD group. When entering only obesity as the variable, no significant association between obesity and FTD development was seen (p = 0.953; OR: 0.981; 95% CI: 0.525–6.894) compared with the AD group. When both smoking and obesity were entered as variables, there were no significant associations between smoking and FTD development (p = 0.600; OR: 1.004; 95% CI: 0.990–1.017) or between obesity and FTD development (p = 0.949; OR: 0.980; 95% CI: 0.524–1.833) compared with AD. No significant associations for smoking or obesity were seen after adjusting for potential confounders (Table 3).

Table 3.

FTD patients versus AD patients

| p value | OR | 95% CI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lower | upper | |||

| Smokinga | 0.600 | 1.004 | 0.990 | 1.017 |

| Obesityb | 0.953 | 0.981 | 0.525 | 6.894 |

| Smokingc | 0.600 | 1.004 | 0.990 | 1.017 |

| Obesityc | 0.949 | 0.980 | 0.524 | 1.833 |

| Adjusted analysisd | ||||

| Smoking | 0.789 | 1.002 | 0.988 | 1.015 |

| Obesity | 0.658 | 1.163 | 0.595 | 2.274 |

| Age at participation in HUNT1 | 0.000 | 0.940 | 0.915 | 0.966 |

| Sex | 0.522 | 0.847 | 0.510 | 1.407 |

| Heart disease | 0.523 | 0.653 | 0.176 | 2.417 |

| Diabetes | 0.957 | 1.062 | 0.120 | 9.392 |

| Hypertension | 0.305 | 0.771 | 0.468 | 1.268 |

Smoking and obesity as risk factors for FTD compared with AD. AD, Alzheimer's disease; CI, confidence interval; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; OR, odds ratio.

Smoking entered as variable.

Obesity entered as a variable.

Smoking and obesity entered as variables.

Smoking, obesity, and confounders entered as variables.

AD Patients Compared to CH Individuals

In the initial analysis entering only smoking as the variable, a significant association for developing AD was seen (p = 0.014; OR: 0.987; 95% CI: 0.977–0.997). When entering only obesity as the variable, a significant association for developing AD was also seen (p = 0.015; OR: 2.679; 95% CI: 1.211–5.928). When both smoking and obesity were entered as variables, a significant increase in the risk of developing AD was observed both for smoking (p = 0.011; OR: 0.987; 95% CI: 0.976–0.997) and obesity (p = 0.013; OR: 2.736; 95% CI: 1.233–6.069). The significant associations disappeared after adjusting for potential confounders (smoking: p = 0.227; OR: 0.992; 95% CI: 0.979–1.005; obesity: p = 0.156; OR: 1.954; 95% CI: 0.775–4.929) (Table 4).

Table 4.

AD patients versus CH individuals

| p value | OR | 95% CI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lower | upper | |||

| Smokinga | 0.014 | 0.987 | 0.977 | 0.997 |

| Obesityb | 0.015 | 2.679 | 1.211 | 5.928 |

| Smokingc | 0.011 | 0.987 | 0.976 | 0.997 |

| Obesityc | 0.013 | 2.736 | 1.233 | 6.069 |

| Adjusted analysisd | ||||

| Smoking | 0.227 | 0.992 | 0.979 | 1.005 |

| Obesity | 0.156 | 1.954 | 0.775 | 4.929 |

| Age at participation in HUNT1 | 0.000 | 1.158 | 1.126 | 1.191 |

| Sex | 0.108 | 0.678 | 0.422 | 1.089 |

| Heart disease | 0.525 | 1.868 | 0.272 | 12.831 |

| Diabetes | 0.243 | 0.345 | 0.058 | 2.063 |

| Hypertension | 0.884 | 0.963 | 0.583 | 1.592 |

Smoking and obesity as risk factors for AD compared with CH. AD, Alzheimer's disease; CH, cognitively healthy; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Smoking entered as a variable.

Obesity entered as a variable.

Smoking and obesity entered as variables.

Smoking, obesity, and confounders entered as variables.

Discussion

This study investigated the association between smoking and obesity and the risk of developing FTD or AD. When patients with FTD were compared with CH individuals, obesity was more likely to be measured at baseline in HUNT1 among those who later developed FTD.

To the best of our knowledge, no other studies have investigated the associations between obesity and FTD compared with a CH control group. In our earlier study, we used the cases and controls as in the present study, but data on risk factors were collected from the HUNT2 study (1995–1997). The aim of that study was to assess anxiety and depression as risk factors for FTD and AD. Obesity was added as a potential confounder in the adjusted analyses. In the adjusted analyses in that study, a significant association was seen between obesity and FTD compared with CH individuals [20].

When FTD patients were compared with CH individuals in our present study, there were no significant associations between smoking and FTD in the adjusted analyses. This finding is in line with one other study assessing tobacco consumption in FTD outpatients and 151 controls, which found no significant associations for tobacco use [33].

When FTD patients were compared to AD patients, no significant associations were found between obesity or smoking and FTD. To our knowledge, only one other study has assessed smoking as a risk factor for FTD compared with AD. In a study performed by Atkins et al. [34], significant associations were found between obesity and smoking in cases with early-onset FTD compared with a control group of early-onset AD. The individuals with early-onset FTD were more likely to be current smokers (OR: 3.12; 95% CI: 1.04–9.09) and to have a higher body weight (OR: 1.03; 95% CI: 1.01–1.06).

A possible explanation for the differences in the findings between the present study and the study by Atkins et al. [34] may be that the mean age for the onset of dementia in both groups in their study was 56 years, while in our study it was 74.4 years for FTD and 79.2 years for AD. The smoking variable was also grouped into “never,” “ex,” or “current” in the study of Atkins et al. [34]. In our study, the smoking variable was grouped into “no” (never smoked) or “yes” (current smoker or ex-smoker). Another possibility for the difference is that the FTD population in our study was smaller.

When AD patients were compared with CH individuals, smoking and obesity were more likely to be reported at baseline in HUNT1 among those who later developed AD than in the CH control group. This is in line with findings in other studies, where both smoking and obesity were identified as risk factors for AD [27, 35, 36, 37].

Strengths and Limitations of This Study

The main strength of our study is its design. A longitudinal, population-based, nested case-control design allowed us to assess risk factors 15–31 years before diagnosis. Another strength is the use of a validated dementia diagnosis from the dementia register and data on obesity and smoking from HUNT1. In addition, the CH control group consisted of verified CH individuals.

There were limitations to our study regarding some of the dementia diagnoses. Some dementia diagnoses from the Hospital Dementia Register were recorded retrospectively. Most patients were examined by multiple doctors who implemented standard routines, but some files had missing data. This may have reduced the validity of some diagnoses [30].

The dementia diagnoses in the Nursing Home Dementia Register were based on a review of data collected from patients, their family members, and their caregivers. Two physicians with extensive clinical and research experience found the data sufficient to make the dementia diagnosis based on the data [30]. Diagnosing FTD in patients living in nursing homes is more difficult than in those attending hospital outpatient clinics. AD patients often develop symptoms and behavior similar to FTD patients late in the course of the disease, which may lead to an incorrect FTD diagnosis [20, 30]. A possible misclassification of dementia type may therefore have affected the findings in our study [20].

Finally, since the data on smoking were self-reported, there is a possibility that the scoring may be biased. Differences in understanding and interpretation of the smoking items may be subject to individual variation. Filling out a self-reported questionnaire may be problematic for individuals with cognitive impairment. It is not likely that FTD or AD cases had developed cognitive impairment before participation in HUNT1, but the possibility cannot be excluded.

Interpretations

One of the findings of our study is that smoking is a risk factor for AD, but not for FTD. Smoking is a well-known risk factor for AD [11, 12] that is thought to be mediated through cardiovascular risk factors [11, 12, 25]. The role of cardiovascular risk factors in FTD has been investigated less [3, 14]. It is possible that cardiovascular risk factors have less of an impact on FTD than on AD.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the only one that has assessed smoking as a risk factor for FTD, with a span of 15–31 years between measurement of smoking and the time of dementia diagnosis. The findings regarding smoking are interesting and should be further investigated in future studies.

Another important finding in our study was that obesity is a risk factor for both AD and FTD. The findings in our earlier study [20] and in the present study suggest that obesity may be a risk factor for FTD from midlife onwards. Still, it is important to consider whether obesity in FTD may be due to the prodromal phase, as changes in eating habits with preferences of sweets and carbohydrates are a common symptom of FTD [4, 7, 8, 20].

An important consideration for the findings in our study is that we do not have any genetic data on the FTD or AD cases in the population. It is possible that some of the FTD and AD cases developed a dementia disease due to hereditary predisposition.

Conclusion

The findings in our study suggest that smoking is a risk factor for AD, but not FTD. Further, they suggest that obesity is a risk factor for both FTD and AD. The differences and similarities between FTD and AD should be considered in future research, which requires studies with longitudinal designs. Future research on modifiable risk factors for FTD should also separate genetic and sporadic cases of FTD. This would provide a clearer understanding of the roles of modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors of FTD.

Statement of Ethics

The study was performed at Namsos Hospital, North-Trøndelag Health Trust, with approval from the Regional Ethics Committee and the Norwegian Ethics Committee. Participating patients gave written consent to take part in the HUNT1 and HUNT3 studies [29, 32].

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The North-Trøndelag Health Study (the HUNT study) is a collaboration between the HUNT Research Center (Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology), the North-Trøndelag County Council, the Central Norway Regional Health Authority, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

References

- 1.Onyike CU, Diehl-Schmid J. The epidemiology of frontotemporal dementia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013 Apr;25((2)):130–7. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2013.776523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finger EC. Frontotemporal Dementias. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016 Apr;22((2 Dementia)):p. 464–489. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.RRRasmussen H Stordal E, and Rosness TA Risk factors for frontotemporal dementia. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2018;138((14)) doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.17.0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerami C, Scarpini E, Cappa SF, Galimberti D. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: current knowledge and future challenges. J Neurol. 2012 Nov;259((11)):2278–2286. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karageorgiou E, Miller BL. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a clinical approach. Semin Neurol. 2014 Apr;34((2)):189–201. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1381735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torralva T, Sposato LA, Riccio PM, Gleichgerrcht E, Roca M, Toledo JB. Role of brain infarcts in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: Clinicopathological characterization in the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center database. Neurobiol Aging. 2015 Oct;36((10)):2861–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bang J, Spina S, Miller BL. Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet. 2015 Oct;386((10004)):1672–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00461-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bott NT, Radke A, Stephens ML, Kramer JH. Frontotemporal dementia: diagnosis, deficits and management. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2014;4((6)):439–454. doi: 10.2217/nmt.14.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007 Jul;3((3)):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International AsD, World Alzheimer Report 2015 . London: International: A.s.D; 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia. An analysis of prevalence, incidence, costs and trends; p. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crous-Bou M, Minguillón C, Gramunt N, Molinuevo JL. Alzheimer's disease prevention: from risk factors to early intervention. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017 Sep;9((1)):71. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0297-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.association A . Alzheimers Association; 2017. 2017 Alzheimers disease facts and figures. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Povova J, Ambroz P, Bar M, Pavukova V, Sery O, Tomaskova H. Epidemiological of and risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: a review. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2012 Jun;156((2)):108–14. doi: 10.5507/bp.2012.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golimstok A, Cámpora N, Rojas JI, Fernandez MC, Elizondo C, Soriano E. Cardiovascular risk factors and frontotemporal dementia: a case-control study. Transl Neurodegener. 2014 Jun;3((1)):13. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosso SM, Landweer EJ, Houterman M, Donker Kaat L, van Duijn CM, van Swieten JC. Medical and environmental risk factors for sporadic frontotemporal dementia: a retrospective case-control study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003 Nov;74((11)):1574–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.11.1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalkonde YV, Jawaid A, Qureshi SU, Shirani P, Wheaton M, Pinto-Patarroyo GP. Medical and environmental risk factors associated with frontotemporal dementia: a case-control study in a veteran population. Alzheimers Dement. 2012 May;8((3)):204–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deutsch MB, Mendez MF, Teng E. Interactions between traumatic brain injury and frontotemporal degeneration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2015;39((3-4)):143–53. doi: 10.1159/000369787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borroni B, Alberici A, Agosti C, Premi E, Padovani A. Education plays a different role in Frontotemporal Dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008 Aug;23((8)):796–800. doi: 10.1002/gps.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller ZA, Rankin KP, Graff-Radford NR, Takada LT, Sturm VE, Cleveland CM. TDP-43 frontotemporal lobar degeneration and autoimmune disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013 Sep;84((9)):956–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen H. RTA, Bosnes O., Salvesen Ø., Knutli M., Stordal E., Anxiety and depression Plays different roles as risk factors in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. The HUNT study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2018 doi: 10.1159/000493973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burton C, Campbell P, Jordan K, Strauss V, Mallen C. The association of anxiety and depression with future dementia diagnosis: a case-control study in primary care. Fam Pract. 2013 Feb;30((1)):25–30. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fratiglioni L, Winblad B, von Strauss E. Prevention of Alzheimer's disease and dementia. Major findings from the Kungsholmen Project. Physiol Behav. 2007 Sep;92((1-2)):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, Reynolds CF., 3rd Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2013 May;202((5)):329–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.118307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.da Silva J, Gonçalves-Pereira M, Xavier M, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. Affective disorders and risk of developing dementia: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2013 Mar;202((3)):177–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Organization WH. WHO tobacco knowledge summaries. Alzheimers Disease International; 2014. Tobacco and dementia. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumgart M, Snyder HM, Carrillo MC, Fazio S, Kim H, Johns H. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: A population-based perspective. Alzheimers Dement. 2015 Jun;11((6)):718–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anjum I, Fayyaz M, Wajid A, Sohail W, Ali A. Does Obesity Increase the Risk of Dementia: A Literature Review. Cureus. 2018 May;10((5)):e2660. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Midthjell K, Lee CM, Langhammer A, Krokstad S, Holmen TL, Hveem K. Trends in overweight and obesity over 22 years in a large adult population: the HUNT Study, Norway. Clin Obes. 2013 Feb;3((1-2)):12–20. doi: 10.1111/cob.12009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergh S, Holmen J, Gabin J, Stordal E, Fikseaunet A, Selbæk G. Cohort profile: the Health and Memory Study (HMS): a dementia cohort linked to the HUNT study in Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2014 Dec;43((6)):1759–68. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosnes O, Troland K, Torsheim T. A Confirmatory Factor Analytic Study of the Wechsler Memory Scale-III in an Elderly Norwegian Sample. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2016 Feb;31((1)):12–7. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acv060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K, Holmen T, Midthjell K, Stene T. Cohort Profile: the HUNT Study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ije/dys095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tremolizzo L, Bianchi E, Susani E, Pupillo E, Messina P, Aliprandi A. Voluptuary Habits and Risk of Frontotemporal Dementia: A Case Control Retrospective Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60((2)):335–40. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atkins ER, Bulsara MK, Panegyres PK. Cerebrovascular risk factors in early-onset dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012 Jun;83((6)):666–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.202846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer's disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011 Sep;10((9)):819–28. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Bruijn RF, Ikram MA. Cardiovascular risk factors and future risk of Alzheimer's disease. BMC Med. 2014 Nov;12((1)):130. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0130-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deckers K, van Boxtel MP, Schiepers OJ, de Vugt M, Muñoz Sánchez JL, Anstey KJ. Target risk factors for dementia prevention: a systematic review and Delphi consensus study on the evidence from observational studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015 Mar;30((3)):234–46. doi: 10.1002/gps.4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]