ABSTRACT

In the Arabidopsis stomatal lineage, cells transit through several distinct precursor identities, each characterized by unique cell division behaviors. Flexibility in the duration of these precursor phases enables plants to alter leaf size and stomatal density in response to environmental conditions; however, transitions between phases must be complete and unidirectional to produce functional and correctly patterned stomata. Among direct transcriptional targets of the stomatal initiating factor SPEECHLESS, a pair of genes, SOL1 and SOL2, are required for effective transitions in the lineage. We show that these two genes, which are homologs of the LIN54 DNA-binding components of the mammalian DREAM complex, are expressed in a cell cycle-dependent manner and regulate cell fate and division properties in the self-renewing early lineage. In the terminal division of the stomatal lineage, however, these two proteins appear to act in opposition to their closest paralog, TSO1, revealing complexity in the gene family that may enable customization of cell divisions in coordination with development.

KEY WORDS: Cell cycle, DREAM complex, Stomata, Cell-state transition, Arabidopsis, CXC-Hinge-CXC

Summary: Two Arabidopsis homologs of LIN54, SOL1 and SOL2, regulate cell fate and cell division in the stomatal lineage, and act in opposition to their closest paralog, TSO1.

INTRODUCTION

The development of complex organized tissues requires a careful balance of cell proliferation and differentiation. One such balancing act is found in the leaves of Arabidopsis, where divisions in the stomatal lineage generate the majority of epidermal cells (Geisler et al., 2000). The stomatal lineage is characterized by an early proliferative meristemoid phase, in which cells divide asymmetrically in a self-renewing fashion, followed by a transition and commitment to one of two alternative fates: pavement cell or guard mother cell (GMC). If a cell becomes a GMC, it will divide symmetrically to form two guard cells (GCs). GCs make up the epidermal components of the stomatal complex, a valve-like structure that facilitates plant/atmosphere gas exchange (Fig. 1A).

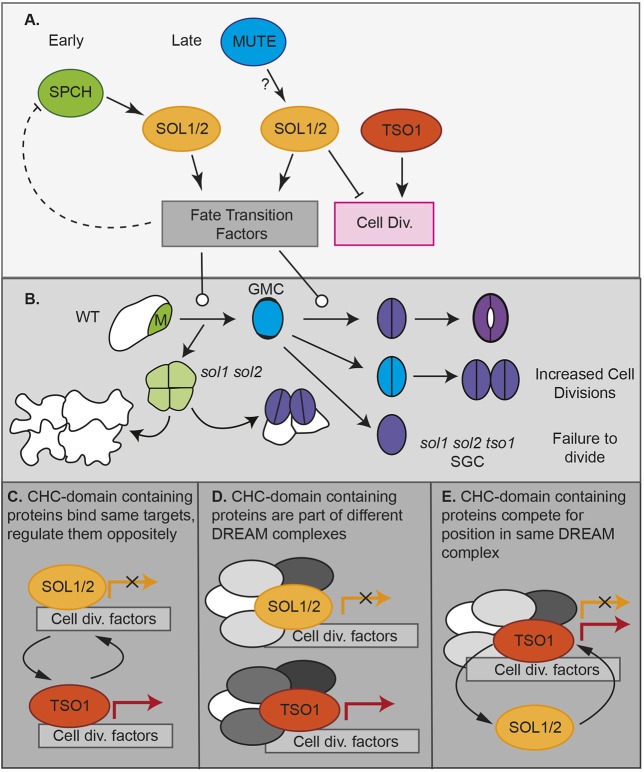

Fig. 1.

SPCH targets SOL1 and SOL2 are expressed in the stomatal lineage. (A) Schematic of stomatal development; each stage is color coordinated with the bHLH transcription factor that regulates it: SPCH (SPEECHLESS) in asymmetrically dividing meristemoid (M) phase; MUTE in guard mother cell (GMC) phase; and FAMA in the guard cell (GC) differentiation phase. (B) Clustal Omega-generated phylogenetic tree of CHC proteins in Arabidopsis, with subjects of this paper highlighted. (C) Evidence that SOL1 and SOL2 transcript levels increase in response to estradiol-mediated induction of SPCH; fold change over estradiol-induced wild-type control (Lau et al., 2014). (D) SPCH ChIP-seq reveals that promoters of SOL1 and SOL2 are bound by SPCH; y-axis represents enrichment value (CSAR), the output score from MACS2 in arbitrary units (from Lau et al., 2014). (E,F) Confocal images of SOL1 and SOL2 transcriptional reporters (green) in 3 dpg abaxial cotyledon, indicating that they are expressed in meristemoids (Ms), guard mother cells (GMCs) and young guard cells (GCs). Cell outlines (purple) are visualized by staining with propidium iodide.

Transcriptional regulation of division and differentiation in the stomatal lineage involves a set of closely related and sequentially expressed basic helix loop helix (bHLH) transcription factors, SPEECHLESS (SPCH), MUTE and FAMA (Fig. 1A), and their more distantly related bHLH heterodimer partners ICE1/SCREAM and SCRM2. These transcription factors regulate both cell fate and cell division. For example, FAMA, in partnership with RETINOBLASTOMA RELATED (RBR) is required to repress GC divisions and to keep these cells in a terminally differentiated state (Lee et al., 2014; Matos et al., 2014). FAMA also directly represses cell-type specific CYCLIN(CYC) D7;1 to prevent over-division of guard cells (Weimer et al., 2018). One stage earlier, MUTE is required to repress the previous meristemoid fate and simultaneously drive cells to adopt GMC fate (Pillitteri et al., 2007). MUTE does so in part by directly regulating CYCD5;1 and other cell cycle factors to ensure the GMC divides symmetrically to form the guard cells (Han et al., 2018).

The earliest phases of the stomatal lineage are complicated because there are three types of asymmetric divisions – entry, amplifying and spacing – that occur an indeterminate number of times (Fig. 1A). Previous studies have sought to understand how SPCH controls entry into the stomatal lineage and how SPCH drives these recurrent and varied asymmetric divisions. From these studies, positive- and negative-feedback motifs emerged, with SPCH inducing its transcriptional partners ICE1 and SCRM2 to locally elevate its activity, while also initiating a longer range negative feedback through secreted signaling peptides to ensure its eventual downregulation (Horst et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2014). Targets that connect SPCH to core cell cycle behaviors and that allow meristemoids to exit the self-renewing stage and progress to GMCs, however, remained elusive.

Here, we have characterized the expression pattern and function of SOL1 and SOL2, two genes encoding proteins containing cysteine rich-repeat (CXC) domains separated by a conserved hinge (CXC-Hinge-CXC, CHC), in the stomatal lineage. Their expression patterns are not identical, but both genes are enriched in the stomatal precursors, and protein reporters accumulate in nuclei in a distinct pattern coincident with cell-cycle progression. We show that SOL1 and SOL2, although initially identified as SPCH target genes, are required for efficient fate transitions through multiple stomatal lineage stages and, in their absence, cell fates are incorrectly specified. Finally, we consider a potentially antagonistic relationship between these two genes and their next closest paralog, TSO1, in the final guard cell-generating division of the stomatal lineage.

RESULTS

SOL1 and SOL2 are stomatal-lineage expressed targets of SPCH

Among the hundreds of genes both bound and upregulated by SPCH, we were particularly drawn to two genes encoding CHC proteins. Animal CHC proteins LIN54 (C. elegans, H. sapiens) and MYB interacting protein (MIP) 120 (D. melanogaster) bind DNA in a sequence-specific manner and are components of DREAM [DP, RBR, E2F and Myb-MuvB (multi-vulval Class B)] complexes. Animal DREAM complexes are implicated in cell-cycle and transcriptional regulation, chromatin remodeling and cell differentiation (Sadasivam and DeCaprio, 2013). Arabidopsis encodes eight CHC-domain proteins (Andersen et al., 2007) (Fig. 1B). TSO1 is the only member of this family functionally characterized, and it is important for properly regulating divisions in the floral meristem (Song et al., 2000). SPCH directly targets At3g22760 and At4g14770, the two genes encoding proteins most similar to TSO1 (Fig. 1B-D). In the literature, At3g22760 and At4g14770 have been given the names SOL1/TCX3 (TCX, TSO1-like CXC; SOL, TSO1-like) and SOL2/TCX2, respectively (Andersen et al., 2007; Liu et al., 1997; Sijacic et al., 2011). We will refer to these genes as SOL1 and SOL2. SOL1 and TSO1 are tandemly arranged in the genome, but TSO1 does not appear to be a SPCH target (Fig. 1C,D).

To determine the expression patterns of SOL1 and SOL2, we generated transcriptional reporters containing 2457 bp and 2513 bp of 5′ sequence, respectively, driving expression of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). Both SOL1 and SOL2 reporters were expressed in young leaves and were most strongly expressed in young stomatal lineage cells, consistent with SOL1 and SOL2 being targets of SPCH (Fig. 1E-F). To gain insight into SOL protein behaviors, we generated translational reporters consisting of the same 5′ regions as in the transcriptional reporters followed by genomic fragments of SOL1 and SOL2 encompassing exons and introns from the predicted translational start codon to just before the stop codon (2757 bp genomic and 3301 bp, respectively) in frame with sequences encoding YFP downstream. Both translational reporters were restricted to nuclei (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3) and both appeared to be functional, as they rescued the sol1 sol2 mutant phenotypes in the stomatal lineage (described below and in Fig. 4).

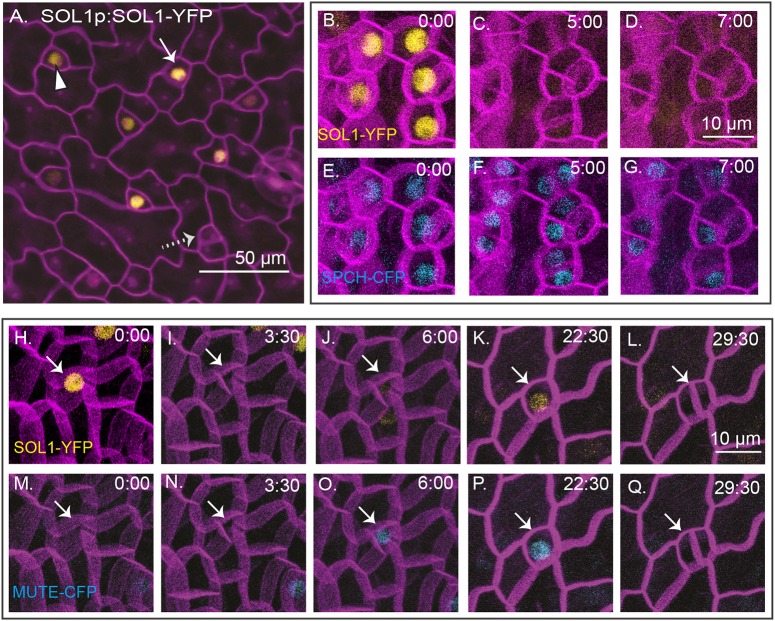

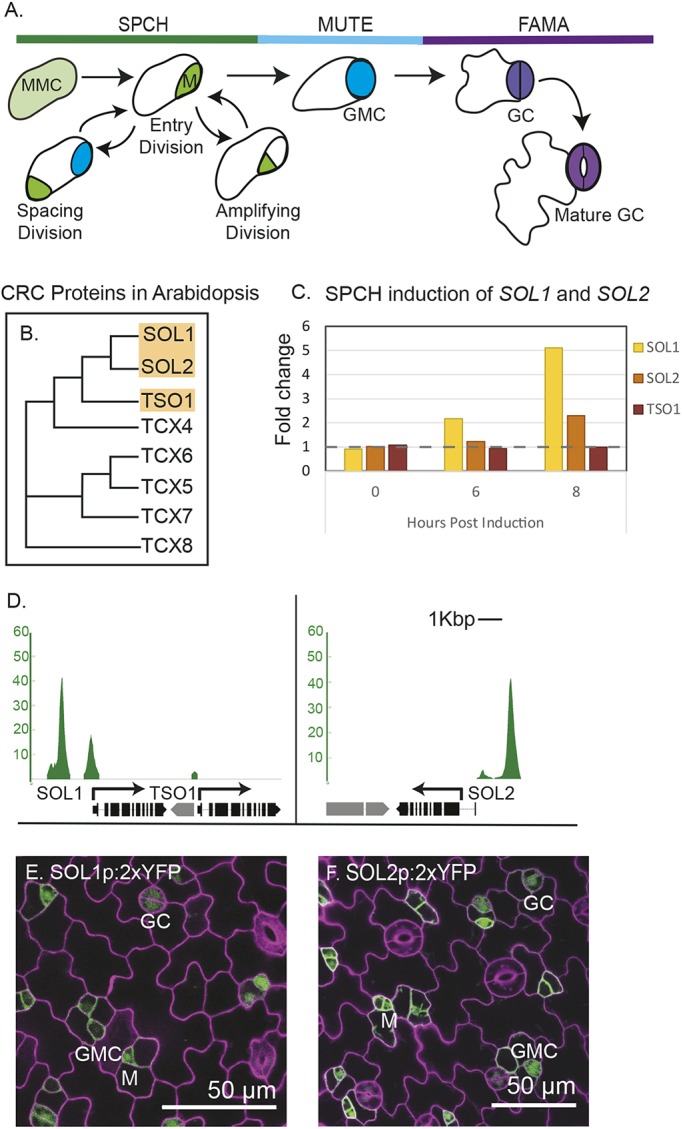

Fig. 2.

SOL1 is co-expressed with SPCH and MUTE prior to asymmetric and symmetric divisions, respectively. (A) A functional SOL1-YFP reporter is expressed in some (white arrow), but not all (dotted arrow), meristemoids and GMCs (arrowhead) in 3 dpg abaxial cotyledons (full genotype: SOL1p:SOL1-YFP; sol1 sol2); cell outlines are visualized using propidium iodide (purple). (B-Q) Time-lapse confocal images; cell outlines (purple) are visualized using ML1pro:RCI2A-mCherry in a wild-type background, time in h:min is noted in the top right of each image. (B-G) SOL1p:SOL1-YFP (yellow, B-D) and SPCHp:SPCH-CFP (blue, E-G). (H-Q) SOL1p:SOL1-YFP (yellow, H-L) and MUTEp:MUTE-CFP (blue, M-Q). Arrows follow a single cell through an asymmetric division (I,N), conversion to a round GMC (K,P) and a symmetric division generating paired guard cells (L,Q).

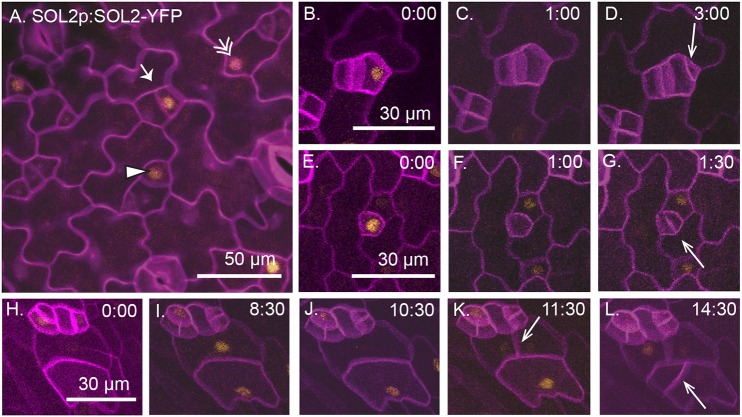

Fig. 3.

SOL2 is expressed in meristemoids, GMCs and pavement cells in a cell cycle-dependent manner. (A) A functional SOL2-YFP reporter is expressed in meristemoids (arrow), GMCs (arrowhead) and pavement cells (double arrow) in 3 dpg abaxial cotyledon (full genotype: SOL2p:SOL2-YFP; sol1 sol2). Cell outlines are stained using propidium iodide (purple). (B-L) Time-lapse images of SOL1p:SOL1-YFP (yellow) with cell outlines marked using ML1p:RCI12A-mCherry (purple) in a wild-type background; time in h:min is noted in the top right of each image. Arrows indicate new cell divisions. (B-D) A meristemoid divides asymmetrically (arrow). (E-G) A GMC divides symmetrically (arrow). (H-L) Pavement cells divide (arrows). In each division, SOL2 expression disappears 1-2 h before cell division.

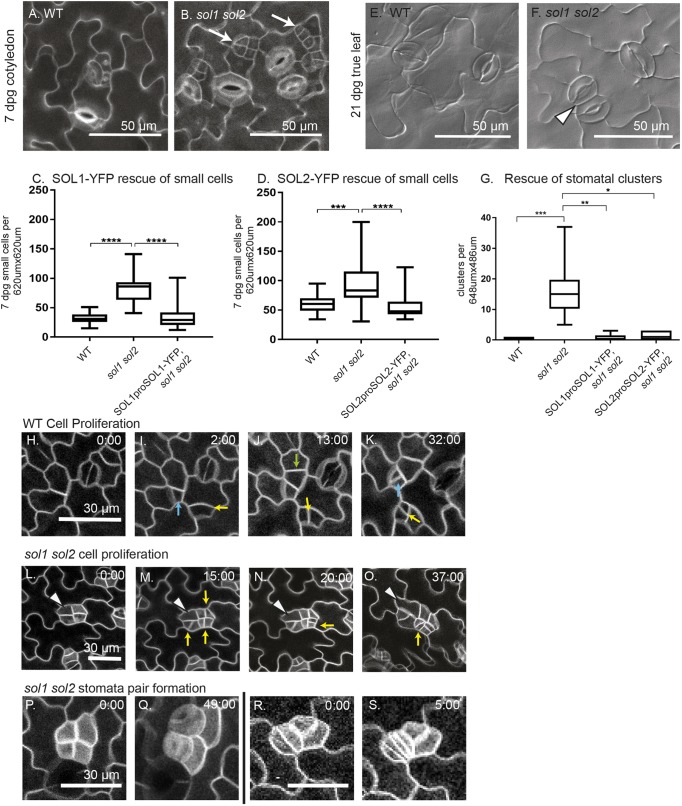

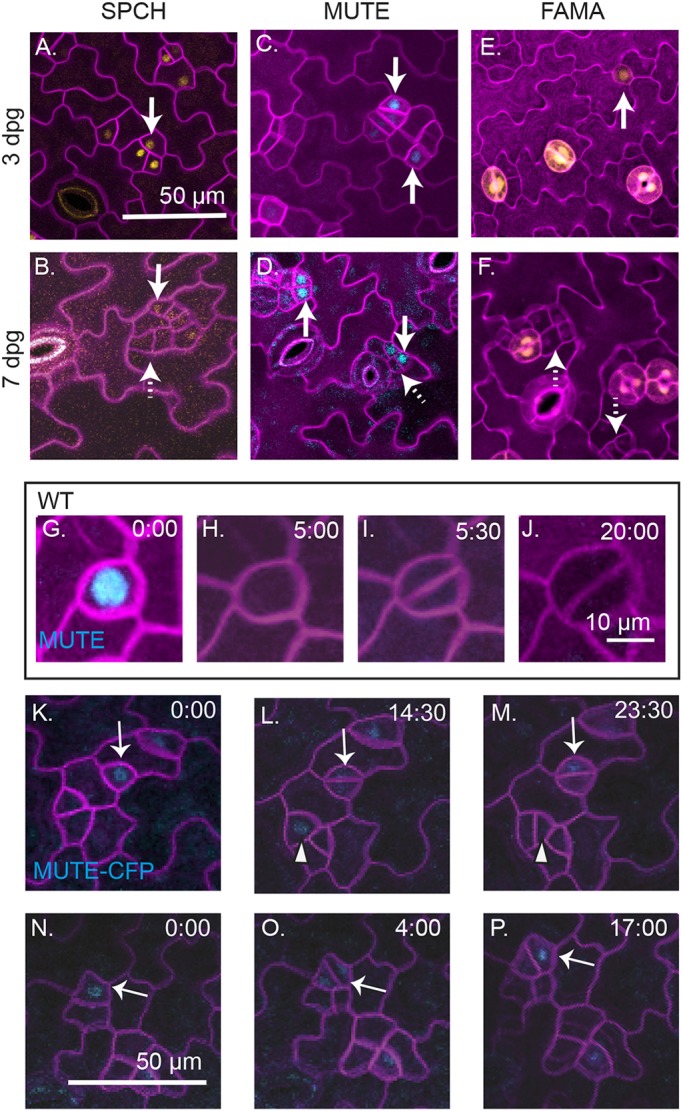

Fig. 4.

SOL1 and SOL2 are redundantly required for control of early and late stomatal cell division behaviors. (A,B) Confocal images of 7 dpg wild-type abaxial cotyledons in wild type (A) and sol1 sol2 (B) with small cells indicated by white arrows. (C,D) Quantification of small-cell phenotype (C) SOL1p:SOL1-YFP rescue (wild type, n=20; sol1 sol2, n=21; SOL1 rescue, n=16) and (D) SOL2p:SOL2-YFP rescue (wild type, n=22; sol1 sol2, n=20; SOL2 rescue, n=22). (E,F) DIC images of 21 dpg adaxial true leaf in wild type (E) and sol1 sol2 (F); a stomatal pair is indicated with an arrowhead. (G) Quantification of pairs and higher-order stomatal clusters, in wild type (n=10), sol1 sol2 (n=10), and both SOL1-YFP (n=5) and SOL2-YFP rescue lines (n=8). (H-S) Time-lapse confocal imaging; cell outlines visualized using ML1p:RCI2A-mCherry, time in h:min is noted in the top right of each image, all images are in a time lapse at the same magnification. (H-K) Cell proliferation in wild type, divisions marked with yellow, blue and green arrows. (L-O) Small cell divisions in sol1 sol2; cell divisions marked with a yellow arrow. One small cell (white arrowhead) begins to lobe. (P,Q) Two neighboring small cells divide to form guard cells. (R,S) Two guard cells each divide symmetrically. For all box and whisker plots, whiskers extend to minimum and maximum; the box indicates interquartile range (25th percentile to 75th percentile) with center line indicating median. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. Dunn's multiple comparison test.

SOL1-YFP was expressed in the meristemoids and GMCs (Fig. 2A). Compared with the corresponding transcriptional reporter, SOL1-YFP showed a somewhat patchy expression pattern. Although it was expressed in nuclei of both GMCs and meristemoids, the brightness varied among populations of these cells (Fig. 2A) and some young stomatal lineage cells did not express it at all (Fig. 2A, dotted arrow). Given the role of SOL1 homologs in the cell cycle, we hypothesized that variation in expression was due to cell cycle-regulated protein abundance. To test this, we performed time-lapse confocal microscopy on SOL1-YFP-expressing plants. We included either SPCH-CFP (meristemoid marker) or MUTE-CFP (GMC marker) and a plasma-membrane marker (RCI2A-mCherry) in the background to allow us to precisely identify the cells in which SOL1 was expressed.

SOL1 was co-expressed with SPCH prior to asymmetric divisions of meristemoids (Fig. 2B,E); however, the SOL1-YFP signal disappears at the division, whereas SPCH-CFP persists initially in both daughter cells (Fig. 2C,F), before fading in the larger daughter cell (Fig. 2D,G). In seedlings co-expressing SOL1-YFP and MUTE-CFP, time-lapse imaging shows SOL1-YFP initially preceding MUTE expression in meristemoids (Fig. 2H,M) and disappearing before these cells divide (Fig. 2 I,N). In cells transitioning to a GMC fate, MUTE-CFP precedes SOL1-YFP expression (Fig. 2J,O), but eventually the two markers are co-expressed (Fig. 2K,P) and both markers are undetectable prior to the symmetric GMC division (Fig. 2L,Q). In summary, SOL1 is expressed in nuclei of cells at the early meristemoid stage, the late meristemoid stage and the GMC stage, but it disappears prior to cell divisions, suggesting that the protein is actively degraded in a cell cycle-dependent manner (see also Fig. S1A-E).

SOL2-YFP resembles SOL1-YFP in its co-expression with SPCH-CFP in nuclei of meristemoids and MUTE-CFP in nuclei of GMCs (Fig. S1F,G). SOL2, however, was often also expressed in the sister cells of meristemoids (stomatal lineage ground cells, SLGCs) and in pavement cells (Fig. 3A, Fig. S1F,G, double arrows). This expression pattern could emerge from a more broadly expressed promoter or because SOL2 is under different cell-cycle regulation from SOL1 and simply persists in these cell types after cell division. Time-lapse imaging revealed that, like SOL1, SOL2-YFP expression disappears prior to asymmetric meristemoid divisions (Fig. 3B-D) and symmetric GMC divisions (Fig. 3E-G). The expanded domain of SOL2, therefore, appears to be due to promoter activity driving expression in pavement cells. In all cell types in which it is expressed, SOL2 is degraded prior to cell divisions (Fig. 3H-L). To further narrow down when in the cell cycle SOL2 was expressed, we time-lapse imaged plants co-expressing SOL2-YFP and the S- and G2-phase marker HTR2pro:CDT1a(C3)-RFP (Yin et al., 2014). SOL2-YFP was visible on average 3 h before CDT1a-RFP (Fig. S1H-L, quantified in M). SOL2-YFP then disappeared 1-2 h before appearance of the new cell plate, consistent with degradation during the G2-M transition (Fig. S1N).

SOL1 and SOL2 are redundantly required for stomatal lineage progression and correct stomatal patterning

To explore the function of these proteins in the stomatal lineage, we identified T-DNA insertion alleles for each and tested their impact on SOL1 or SOL2 expression (Fig. S2A). Two alleles for each gene dramatically reduced expression as assayed by qRT-PCR, although none completely abolished it (Fig. S2B). Double mutants were generated by crossing and genotyping for the relevant mutation by PCR (see Materials and methods). A typical phenotype for disruptions in stomatal lineage signaling, cell fate or polarity is the presence of stomata in pairs or clusters in mature cotyledons, so we counted stomatal pairs on 21 days post germination (dpg) adaxial cotyledons for each single mutant and two double mutant combinations. No SOL1 or SOL2 single mutant had a statistically significant stomatal pairing phenotype, but both double mutant combinations did (Fig. S2C). The strongest stomatal pairing phenotype and lowest expression of SOL1 and SOL2 genes was found in the sol1-4 sol2-2 double mutant, so we focused on this double mutant for more detailed phenotypic analysis. Unless otherwise stated, sol1 sol2 will refer to this specific allelic combination.

To capture the complexity of divisions and fates in the stomatal lineage, we characterized the sol1 sol2 phenotype at 7 dpg, when SPCH-associated amplifying divisions are occurring, and a late stage (21 dpg) when the (wild-type) epidermis has finished development and contains only mature GCs and pavement cells. At 7 dpg in abaxial cotyledons, the most distinctive sol1 sol2 phenotype was the increased number of small cells (here defined as cells less than 200 μm2), often found in clusters (Fig. 4B, white arrows). Wild-type seedlings have some of these small cells (Fig. 4A); however, the number is significantly increased in sol1 sol2 double mutants (Fig. 4B-D) and this small cell phenotype can be rescued by expression of SOL1 or SOL2 reporters (Fig. 4C,D).

We next examined the late-stage stomatal phenotype in first true leaves at 21 dpg. In wild-type seedlings, the adaxial true leaf epidermis consists mostly of GCs and pavement cells (Fig. 4E). In sol1 sol2 double mutants at this stage, the most prominent phenotype was pairs of stomata (Fig. 4F, white arrowhead). Resupplying SOL activity via translational reporter also rescued this late-stage phenotype (Fig. 4G). We scored the adaxial side of the sol1 sol2 true leaf for the end stage stomatal phenotype because cells on the abaxial side were still dividing at 21 dpg, a phenotype in itself. Both abaxial and adaxial sides of sol1 sol2 leaves, however, contained stomatal pairs.

We used time-lapse imaging to pinpoint the origin of the early and late stomatal lineage phenotypes, and the connection between them. We started the time-lapse imaging at 3 dpg, before the small cell phenotype is obvious in the mutant, enabling us to capture the initial events leading to its emergence over the course of the time-lapse. sol1 sol2 cotyledons marked with plasma membrane marker ML1pro:RCI2A-mCherry were tracked for 60 h (images captured every 60 min) and compared with a time-matched series from a wild-type cotyledon. Stomatal lineage progression is asynchronous, and so we followed cells from regions displaying a diversity of precursor and terminal cell types.

In wild type, highly asymmetric divisions occurred in some protodermal cells (e.g. Fig. 4I, blue arrow) and these were followed by additional ‘amplifying’ asymmetric divisions (Fig. 4K, blue arrow). In smaller protodermal cells, divisions were not as obviously asymmetric immediately after division, but over time the daughter cells diverged in size and fate, with one expanding and the other dividing again asymmetrically (e.g. Fig. 4I-K, yellow arrows). We found that small cell clusters in sol1 sol2 could originate from symmetric or asymmetric divisions of protodermal cells (e.g. Fig. S3A-G) and, once formed, divided in a manner similar to that observed in the small protodermal cells from wild type, with slight size asymmetries (Fig. 4L-O, yellow arrows, size quantified in Fig. S3H). In the cluster shown in Fig. 4L-O, one cell did not divide and instead expanded and began to lobe (Fig. 4K-N, white arrowhead), indicating that some small cells differentiate into pavement cells.

The number of small cells in each cluster increased during the sol1 sol2, but not the wild type, time-course, suggesting that sol1 sol2 cells were either dividing faster or failing to expand post division. To evaluate these possibilities, we needed to be able to monitor a cell from its initial ‘birth’ until its next division, which was challenging due to the typical (>16 h) length of plant cell cycles; however, from the time-lapse movies we were able to quantify 24 such divisions in wild type and 22 divisions in sol1 sol2. We calculated cell cycle length as the time (in hours) between one cell division and the next, and areal expansion as the traced 2D area of a cell immediately after its first division compared with immediately before its second division. We found that the cell cycle in sol1 sol2 double mutants was not faster, and was actually slightly slower, than in wild type (4.5 h median difference, P=0.04, Fig. S3I). The percent areal growth per hour, however, was also significantly less (Fig. S3J and Materials and methods). Overall leaf size in sol1 sol2 was not significantly different from wild type at 14 dpg (Fig. S3K), consistent with the smaller cell size balancing out the effect of greater cell numbers observed in the mutants. We conclude that the small cells are the result of slower cell expansion, which allows these small cells to accumulate following otherwise normal divisions. Failure to expand post division is also seen when SPCH or ICE1 are artificially stabilized such that they persist in the larger (SLGC) daughter of an asymmetric division and lead to SLGCs taking on meristemoid behaviors (Kanaoka et al., 2008; Lampard et al., 2008).

SOL1 and SOL2 activity is required at multiple transitions

The late-stage phenotype of stomatal pairs could arise from inappropriate divisions of GCs, or from an earlier cell identity error that enables neighboring cells to act as GC precursors. We observed both of these defects. In Fig. 4O,P, two cells from a cluster of four form adjacent GCs, connecting the early stage phenotype to the late-stage phenotype. However, we also observed two young GCs dividing again to produce four adjacent GCs (Fig. 4Q,R). These defects suggest roles for SOLs in multiple stomatal lineage fate transitions and are consistent with the expression of SOLs just prior to the meristemoid and GMC divisions.

MUTE expression is disconnected from cell fate in sol1 sol2 double mutants

Division behaviors suggested cell identity defects in the stomatal lineage, but to more accurately characterize these defects, we examined SPCH, MUTE and FAMA translational reporters in sol1 sol2 mutants. To capture the earliest stages of the lineage, we imaged cotyledons at 3 dpg as well as at 7 dpg. SPCH is expressed in small cells in sol1 sol2 and wild type at 3 dpg, although there are more of these small cells in the mutant (Fig. 5A and Fig. S4A). At 7 dpg, it is clear that some of the cells have begun to lobe and lose SPCH expression (Fig. 5B), so SOL1 and SOL2 are not absolutely required for SPCH downregulation but may modulate it. Analysis of MUTE expression at these two timepoints revealed a clear deviation from wild type in that the number of cells expressing MUTE did not decrease over time (Fig. 5C-D). Because elevated MUTE can lead to stomatal hyperproduction (Pillitteri et al., 2007), we also imaged a transcriptional reporter (MUTEpro:CFPnls). Like MUTEpro:MUTE-CFP, the transcriptional reporter also persisted longer in sol1 sol2 (Fig. S4G,H). FAMA is mostly expressed in recently divided GCs at 3 and 7 dpg, but is occasionally observed in rounded small cells that are likely to divide symmetrically (Fig. 5E,F), suggesting that most small cells in sol1 sol2 have not entered the later (FAMA) stage of the lineage (wild-type comparisons for all markers are in Fig. S4).

Fig. 5.

Markers of cell fate are inappropriately expressed in sol1 sol2 mutants. (A-F) Confocal images of abaxial cotyledons from sol1 sol2 mutants, at indicated days post germination, with cell fate reporters SPCHp:SPCH-YFP (A,B), MUTEp:MUTE-CFP (C,D) and FAMAp:YFPnls (E,F). Cell outlines (purple) are visualized using propidium iodide. All images are at the same scale. (G-J) Selections from time-lapse images of ML1p:RCI2A-mCherry and MUTEp:MUTE-CFP markers in wild type, showing a MUTE expression in a GMC that will later divide symmetrically. (K-P) Selections from time-lapse recordings of sol1 sol2 mutant expressing ML1pro:RCI2A-mCherry and MUTEp:MUTE-CFP markers; all images are at the same scale. (K-M) Two MUTE-expressing cells (indicated by a solid white arrow and arrowhead) divide. (N-P) A MUTE-expressing cell (indicated by a solid white arrow) divides asymmetrically.

The appearance of MUTE-expressing cells at both 3 dpg and 7 dpg timepoints made us curious about whether the MUTE-positive small cells at 3 dpg progress in the lineage to form GCs or whether they are stuck at an earlier stage. To determine the fate of MUTE-expressing small cells, we performed time-lapse imaging on a MUTE-CFP reporter in sol1 sol2 seedlings (3 dpg abaxial cotyledon). In wild-type plants, MUTE expression begins after the final asymmetric division (Fig. 5G) and it disappears prior to the symmetric division (Fig. 5H,I), therefore MUTE-expressing cells do not normally divide in wild-type plants. In sol1 sol2 lines, however, we found that small cells expressing MUTE-CFP often divide. Sometimes these divisions are visually symmetric, like GMC divisions; however, MUTE expression is still detected long after the division (Fig. 5K-M, white arrow). Other divisions resemble asymmetric meristemoid divisions (Fig. 5L,M, white arrowhead; Fig. 5N-P, white arrow). Thus, in the absence of SOL1 and SOL2, MUTE expression is no longer sufficient to reliably predict GMC fate.

SOL1 and SOL2 may oppose activity of the paralog TSO1 in the stomatal lineage

SOL1 and SOL2 are closely related to TSO1, the CHC-domain protein best characterized in plants (Andersen et al., 2007; Sijacic et al., 2011). We did not originally focus on TSO1 because it is neither bound nor induced by SPCH (Fig. 1B,C; Lau et al., 2014), but we found the recently described TSO1 translational reporter (Wang et al., 2018) to be expressed throughout the epidermis, in meristemoids (Fig. 6A, arrow), GMCs (Fig. 6A, arrowheads) and pavement cells (Fig. 6A, double arrow), although not in guard cells. This led us to speculate that TSO1 could be partially redundant with SOL1 and SOL2.

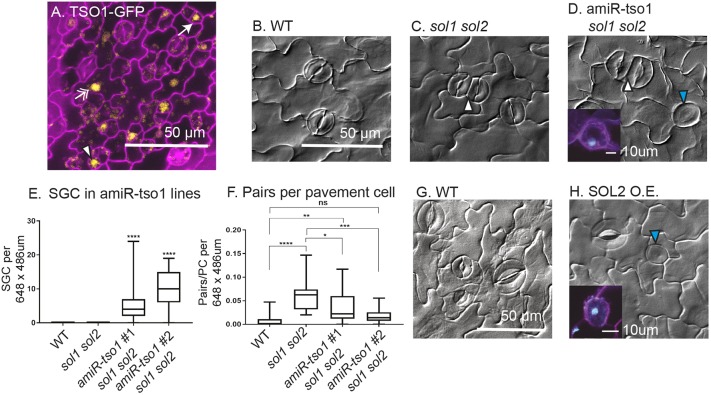

Fig. 6.

Depletion of TSO1 in sol1 sol2 background or overexpression of SOL2 results in similar guard cell division defects. (A) Confocal image of TSO1p:TSO1-GFP reporter in a wild-type background expressed throughout epidermis, in meristemoids (arrow), GMCs (arrowhead) and pavement cells (double arrow). (B-D) DIC images of 21 dpg adaxial true leaves in wild type (B), in sol1 sol2 (stomatal pair indicated by a white arrowhead) (C) and in amiR-tso1 sol1 sol2 (stomatal pair indicated by white arrowhead and SGC by blue arrowhead) (D). (E) Quantification of SGC number per field of view (wild type, n=27; sol1 sol2, n=29; amiR-tso1 #1 sol1 sol2, n=31; amiR-tso1 #2 sol1 sol2, n=19). (F) Number of stomatal pairs in field of view normalized to account for an overall increase in cell number (wild type, n=20; sol1 sol2, n=24; amiR-tso1 #1 sol1 sol2, n=30; amiR-tso1 #2 sol1 sol2, n=18). (G,H) DIC images showing production of SGCs upon SOL2-YFP overexpression (H). Insets in D and H are confocal images of SGCs with stained nuclei (cyan). For all box and whisker plots, whiskers extend to minimum and maximum; box indicates interquartile range (25th percentile to 75th percentile) with center line indicating median. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001, Dunn's multiple comparison test.

The TSO1 gene is adjacent to SOL1 (Fig. 1D), which made generating a triple mutant by crossing unfeasible, so we reduced expression levels of TSO1 in the stomatal lineage by expressing an artificial miRNA (amiRNA) against TSO1 with the TOO MANY MOUTHS (TMM) promoter (Nadeau and Sack, 2002). In the sol1 sol2 background, multiple independent TMMpro:amiRNA-tso1 lines led to an unexpected new phenotype in which GCs failed to divide, and instead formed large round- or kidney-shaped cells with a single nucleus (Fig. 6D, blue arrowhead). We termed this phenotype single guard cell, or SGC, to be consistent with previous literature describing this phenotype (Boudolf et al., 2004; Xie et al., 2010). The SGC phenotype was not described in previous reports on TSO1 (Andersen et al., 2007; Liu et al., 1997), and our own analysis of segregating populations from two previously described alleles (tso1 homozygotes are sterile), tso1-1/sup-5 and tso1-6/+, failed to identify the SGC phenotype (no instances in 18 seedlings from tso1-1/sup-5 plants and 24 seedlings from tso1-6/+). We therefore concluded that in the sol1 sol2 background, TSO1 helps ensure the division of the GMC prior to differentiation.

We quantified SGC phenotypes in two independent sol1 sol2; amiRNA-tso1 lines (Fig. 6E) and confirmed that SGCs were unique to this triple depletion genotype and were not found in sol1 sol2 (Fig. 6E) or due to effects of the TSO1 amiRNA alone (no SGCs observed in four independent amiRNA lines, >30 seedlings/line examined). In doing so, we also noticed that sol1 sol2; amiRNA-tso1 had fewer stomatal pairs than in sol1 sol2, and that the stomata and pavement cells were visibly larger in wild type or sol1 sol2 (Fig. 6D). These phenotypes were the opposite of that produced in sol1 sol2 alone; therefore, we asked whether depletion of TSO1 could ‘rescue’ the stomatal pairing and small cell phenotypes associated with loss of SOL1 and SOL2. When quantified, the sol1 sol2; amiRNA-tso1 lines had fewer cells per field of view than did sol1 sol2 plants (Fig. S5A). Even when normalized for total cell number, the number of pairs was reduced in amiRNA-tso1 sol1 sol2 lines compared with sol1 sol2 mutants (Fig. 6F). The rescue of the sol1 sol2 pairing phenotype, as well as the larger pavement cells and GCs, suggested a repression of cell division in the epidermis.

The phenotypic effects on stomatal lineage cells suggested that TSO1 acts in opposition to SOL1 and SOL2. We overexpressed SOL2, reasoning that if this opposition idea were correct, then more SOL2 would produce the same SGC phenotype as loss of TSO1. We placed SOL2-CFP under the control of a strong, estradiol-inducible promoter and induced 3 dpg seedlings bearing the transgene with estradiol for 8 h, monitored expression of CFP to confirm overexpression of SOL2 (Fig. S5B) and then returned seedlings to plates to grow for an additional 5 days. The SOL2-overexpressing seedlings produced SGCs with single nuclei (Fig. 6H, blue arrowhead; Fig. S5D-E), whereas the equivalent estradiol treatment on a control line did not (Fig. 6G). The majority of SOL2-CFP-expressing seedlings exhibited SGCs on both the adaxial and abaxial surfaces (Fig. S5C). We conclude that at the GMC stage of stomatal lineage development, three closely related CHC proteins could have opposite effects on cell cycle progression, with TSO1 acting as a positive regulator and SOL2 (and SOL1) as negative regulators.

DISCUSSION

As a key regulator of the stomatal lineage, SPCH activates and represses thousands of genes to start the proliferative meristemoid phase of the lineage. Logically, SPCH must also set in place a program that will allow cells to exit this proliferative stage. SPCH directly activates many of its own negative regulators, including BASL, EPF2 and TMM, suggesting the existence of feedback loops that modulate SPCH levels (Horst et al., 2015; Lau et al., 2014). Here, we provide evidence that the SPCH transcriptional targets SOL1 and SOL2 may ensure stable transitions to post-SPCH identities.

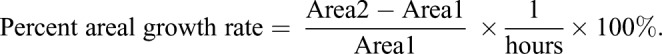

Analysis of SOL1 and SOL2 expression patterns and the double mutant phenotype also revealed roles of SOL1 and SOL2 at post-SPCH stages of stomatal development. Most notably, SOL1, SOL2 and their paralog TSO1, which is not a direct target of SPCH, but is expressed in the epidermis, are then involved in the next fate transition from GMC to guard cell. In wild type, this transition is tied to the symmetric division of the GMC into two GCs. In sol1 sol2 mutants, ectopic GMC-like divisions of young GCs can result in stomatal pairs. The opposite phenotype, in which GMCs fail to divide, occurs in response to both overexpression of SOL2 and knockdown of TSO1 in the sol1 sol2 background, suggesting oppositional roles of SOL1/2 and TSO1 at the GMC division (diagrammed in Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

A model of SOL function in stomatal fate transitions and cell divisions. (A) In meristemoids, SPCH binds to and induces SOL1 and SOL2; their protein products regulate the meristemoid→GMC transition and may downregulate SPCH in a negative-feedback loop. In GMCs, MUTE induces SOL1 and SOL2 to regulate the GMC→GC transition and limit cell divisions. At this stage, SOL1 and SOL2 activities are opposite to that of TSO1. (B) In sol1 sol2 mutants, meristemoids (M) fail to acquire SLGC or GMC identity in a timely manner, although they may eventually become stomata (sometimes forming pairs) or pavement cells. Therefore, stomatal pairs arise from two different defects in fate transition: one early and one late. In the absence of tso1, GMCs fail to divide, forming single guard cells (SGC). (C-E) Models for how SOL1/2 and TSO1 might oppositely regulate GMC divisions alone or as part of a DREAM complex.

How might SOL1, SOL2 and TSO1 modulate multiple fate transitions? One possibility is that, as DNA-binding domain-containing proteins, they regulate expression of SPCH, MUTE or FAMA. In support of this idea, a genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis transcription factor binding found SOL1 and SOL2 associated with sequences immediately upstream of SPCH (O'Malley et al., 2016). Another recent study found that both genes are upregulated in response to MUTE induction (log2 fold changes of 1.60 and 0.83, respectively) (Han et al., 2018). Whether these genes are direct MUTE targets is not known, but the appearance of SOL1 in GMCs shortly following MUTE expression (Fig. 2J,K) is consistent with it being a MUTE target. The broader expression pattern of SOL2 suggests it is likely dependent on other inputs, consistent with the weaker induction of SOL2 relative to SOL1 in both SPCH and MUTE induction experiments (Han et al., 2018; Lau et al., 2014). The inappropriate expression of MUTE in small cells may suggest that SOL1 and SOL2 downregulate MUTE in a negative-feedback loop; however, neither SOL1 nor SOL2 was found to bind upstream of MUTE in large-scale assays of transcription factors (O'Malley et al., 2016). Alternatively, as downstream targets of MUTE, SOL1 and SOL2 could be coordinating divisions with fate transitions (Fig. 7B). In this model, MUTE is expressed in the small cells at the correct time, but in the absence of SOL1 and SOL2, these cells fail to transition to GMCs and continue to undergo meristemoid-like divisions.

Cell fate is intrinsically tied to cell division in the stomatal lineage; therefore, it is not always possible to cleanly separate the two. For example, loss of FAMA expression leads to immature guard cells that recapitulate GMC divisions (Ohashi-Ito and Bergmann, 2006). If SOL1 and SOL2 promote differentiation, then in their absence, young GCs might retain GMC fate long enough to divide a second time. In the absence of tso1 sol1 and sol2, GMCs might differentiate too quickly, bypassing the ability to divide and resulting in SGCs. Alternatively, a direct mechanistic connection between SOLs and cell cycle regulation is hinted at by the cell cycle-dependent protein degradation of the SOLs, and the known roles of animal CHC-domain proteins. In animals, the genomes of which typically encodes a single somatic CHC domain-containing protein, the CHC protein is found in two types of DREAM complexes: the quiescent DREAM complex, the role of which is to repress gene expression in G0; and the MYB-containing ‘permissive’ DREAM complex, which is found in actively proliferating cells (Beall et al., 2004; Beall et al., 2007).

Recent genetic and protein interaction studies have promoted the idea of plant DREAM complexes; however, if plants do have DREAM complexes, their composition would need to differ from the animal complexes, as several core structural proteins are not encoded in plant genomes, and other components are present in different numbers of copies. For example, Arabidopsis has only a single retinoblastoma-like gene, RETINOBLASTOMA RELATED (RBR), which regulates stomatal lineage divisions and binds the regulatory regions upstream of SPCH (Weimer et al., 2012). Reduction in levels of RBR via amiRNA leads to proliferation of small cells in the leaf epidermis as well as extra divisions in the GCs (Borghi et al., 2010; Desvoyes et al., 2006; Matos et al., 2014). Because Arabidopsis has only a single RB-like gene, however, it is difficult to separate its role in a possible DREAM complex from its well-characterized role regulating the G1→S transition. Conversely, families such as the MYB3R proteins and CHC domain-containing proteins, have expanded in Arabidopsis, which may have led to the development of new subcomplexes with different roles from those in animal systems. Supporting this hypothesis, MYB3R1, a MYB with both cell cycle activating and repressive roles (Araki et al., 2004; Ito et al., 2001; Kobayashi et al., 2015), physically interacts with TSO1 and mutations in MYB3R1 suppress the tso1-1 phenotype (Wang et al., 2018). Meanwhile, SOL1 appeared as a partner of the cell cycle repressor MYB3R3 in a proteomics-based analysis (Kobayashi et al., 2015).

One of our most unexpected and interesting findings was that SOL1 and SOL2 expression patterns overlap their homolog TSO1 in the epidermis, but phenotypes associated with their loss or overexpression are opposite. This is a novel situation for DREAM complexes, as there are only single CHC (and MYB) proteins available for the animal somatic complexes. We can imagine three alternative scenarios to explain the differential behaviors of SOL1/2 and TSO1. First, the CHC proteins may regulate gene expression on their own, with SOL1/2 competing with TSO1 for common cell division-promoting targets (Fig. 7C). Second, SOL1/2 and TSO1 may be incorporated into DREAM complexes but, given their published interactions with different MYB3Rs, these DREAM complexes may be comprised of different subunits (Fig. 7D). Alternatively, SOL1, SOL2 and TSO1 may complete with each other for inclusion in a common DREAM complex (Fig. 7E). Finding the precise molecular mechanism for the diverse CHC family roles in cell behaviors will be an intriguing but challenging future goal, as it will require quantitative assays of differential incorporation of CHCs into functional complexes, coupled to measurements of gene expression in response to different complexes in the relevant cell types.

Key regulators of three separate stomatal cell states have been known for many years; here, we add an important feature to the developmental trajectory: CHC-domain proteins that can enforce transitions between these fates and can regulate their associated cell cycle behaviors. New technologies enabling measures of transcriptomes and chromatin accessibility in individual cells have reinvigorated the idea of ‘transitional states’, and although there are computational methods to identify where and when these states occur (Farrell et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2018), how they are resolved will require experimental analysis of regulators like the SOLs. We focused on the stomatal lineage and found multiple fate transitions are regulated by the same factors, leading to the interesting possibility that CHC proteins and the DREAM complex will be used repeatedly for cell fate transitions in other tissues, organs and stages of plant development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia (Col-0) was used as wild type in all experiments. Seedlings were grown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Caisson Labs) at 22°C in an ARR66 Percival Chamber under 16 h light/8 h dark cycles and were examined at the indicated times. The following previously described mutants and reporter lines were used in this study: SPCHpro:SPCH-CFP and MUTEpro:MUTE-YFP (Davies and Bergmann, 2014); FAMAproYFPnls (Ohashi-Ito and Bergmann, 2006); HTR2pro:CDT1a(C3)-RFP (Yin et al., 2014); TSO1pro:TSO1-GFP (Wang et al., 2018); and tso1-6 (SALK_074231C) (Andersen et al., 2007). The following lines were obtained from the ABRC stock center: sol1-3(SAIL_742_H03), sol1-4 (WiscDsLoxHs033_03E), sol2-2 (SALK_021952) and sol2-3 (SALK_031643).

Vector construction and plant transformation

Constructs were generated using the Gateway system (Invitrogen). Appropriate genome sequences (PCR amplified from Col-0 or from entry clones) were cloned into Gateway-compatible entry vectors, typically pENTR/D-TOPO (Life Technologies), while promoter sequences were cloned into pENTR-5′TOPO (Life Technologies) to facilitate subsequent cloning into plant binary vectors pHGY (Kubo et al., 2005) or R4pGWB destination vector system (Nakagawa et al., 2008).

Transcriptional reporters for SOL1 and SOL2 were generated by cloning a 5′ regulatory region spanning 2500 bp or to the 3′ end of the upstream gene or (whichever was shorter) to the ATG translational start site into pENTR5′ and recombining with pENTR YFP into R4pGWB540 (Nakagawa et al., 2008). For the SOL1 and SOL2 translational fusions, the genomic fragments corresponding to SOL1 and SOL2 (excluding stop codon) were amplified by PCR then cloned in pENTR D/TOPO (Life Technologies). LR Clonase II was then used to recombine the resulting pENTR clone and pENTR 5′ promoters (SOL1p, SOL2p) into R4pGWB540. For the estradiol-inducible lines, the UBQ10 promoter was amplified by PCR and subcloned into pJET, then digested out using AscI XhoI double digest and ligated into p1R4:ML-XVE (Siligato et al., 2016). P1R4:UBQ10-XVE was recombined with SOL2 pENTR and R4pGWB443 (Nakagawa et al., 2008). The TSO1 amiRNA was generated as described previously (Sijacic et al., 2011).

Transgenic plants were generated by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (Clough, 2005), and transgenic seedlings were selected by growth on half-strength MS plates supplemented with 50 mg/l Hygromycin (pHGY-, p35HGY-, pGWB1-, pGWB540-based constructs), 100 mg/l kanamycin (pGWB440-based constructs) or 12 mg/l Basta (pGWB640-based constructs). Primer sequences used for entry clones are provided in Table S1.

Estradiol induction

3 dpg seedlings grown on agar-solidified half-strength MS media were flooded with 10 μM estradiol (Fluka Chemicals) or a vehicle control. At 8 h post induction, liquid was removed and plates were allowed to dry before being returned to the incubator for 5 more days. Tissue was collected at 8 dpg and cleared in 7:1 ethanol:acetic acid.

Nuclear staining

Seedlings were permeabilized by incubating in 0.5% w/v Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 15 min, rinsed and incubated in 0.1 mg/ml Hoescht 33342 in water for 30 min, then rinsed and incubated in 0.02 mg/ml FM4-64 dye (Invitrogen) to visualize the cell membranes and imaged by confocal microscopy.

Confocal and differential interference contrast microscopy

For confocal microscopy, images were captured using a Leica SP5 microscope and processed in ImageJ. Cell outlines were visualized by 0.1 mg/ml propidium iodide in water (Molecular Probes). Seedlings were incubated for 10 min in the staining solution and then rinsed once in H2O. For differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, samples were cleared in 7:1 ethanol:acetic acid, treated for 30 min with 1 N potassium hydroxide, rinsed in water and mounted in Hoyer's medium. DIC images were obtained on a Leica DM2500.

Statistical analysis

Image J was used to blind images and then count clustering events within a defined field of view. One field of view was used per seedling in all analyses; therefore, n indicated in legends refers to both number of seedlings and number of fields of view. Statistical analysis was completed in Graphpad Prism. For clustering and cell counts, data were generally not normally distributed (based on D'Agostino-Pearson test) so analysis was completed with default settings for nonparametric tests. The Mann–Whitney test was used, where indicated, to compare two sets of data; to compare multiple groups against one another, the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test (which adjusts for multiple comparisons) was used as indicated in figure legends.

RT-qPCR analysis

RNA was extracted from 9 dpg whole seedlings (sol1-3, sol1-4, sol2-2, sol2-3 and sol1-4 sol2-2 double mutants, and wild-type controls) using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNAse digestion. cDNA was synthesized with iSCRIPT cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad), followed by amplification with the SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) using gene specific primers on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Data were normalized to ACTIN2 gene controls using the ΔΔCT method. Three biological replicates were assayed per genotype. Primers are listed in Table S1.

Time-lapse imaging

After growth on half-strength MS media, seedlings were transferred to a sterilized perfusion chamber at the indicated days post germination for imaging on a Leica SP5 confocal microscope following protocols described previously (Davies and Bergmann, 2014). The chamber was perfused with one-quarter strength 0.75% (w/v) sucrose (or glucose) liquid MS growth media (pH 5.8) at a rate of 2 ml/h. Z-stacks through the epidermis were captured with Leica software every 30 or every 60 min over 12-60 h periods and then processed with Fiji/ImageJ (NIH). Areal growth was calculated by determining the 2D area immediately after one division (Area1) and immediately prior to the next division of the same cell (Area2) using ImageJ.

|

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank lab members Nathan Cho for constructing the SOL2-YFP, CDT1a-RFP line, Yan Gong and Dr Heather Cartwright (Carnegie) for imaging advice, and Dr Annika Weimer and Dr Camila Lopez-Anido for detailed feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: A.R.S., K.A.D., D.C.B.; Methodology: A.R.S., K.A.D., D.C.B.; Validation: A.R.S.; Formal analysis: A.R.S., K.A.D.; Investigation: A.R.S., K.A.D.; Resources: W.W., Z.L.; Writing - original draft: A.R.S., K.A.D., D.C.B.; Writing - review & editing: A.R.S., K.A.D., W.W., Z.L., D.C.B.; Visualization: A.R.S., K.A.D.; Supervision: D.C.B.; Project administration: D.C.B.; Funding acquisition: D.C.B.

Funding

A.R.S. was supported by the Donald Kennedy Fellowship and a National Institutes of Health graduate training grant (NIH5T32GM007276) awarded to Stanford University. K.A.D. was an National Science Foundation Graduate research fellow. D.C.B. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.171066.supplemental

References

- Andersen S. U., Algreen-Petersen R. G., Hoedl M., Jurkiewicz A., Cvitanich C., Braunschweig U., Schauser L., Oh S. A., Twell D. and Jensen E. O. (2007). The conserved cysteine-rich domain of a tesmin/TSO1-like protein binds zinc in vitro and TSO1 is required for both male and female fertility in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 3657-3670. 10.1093/jxb/erm215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki S., Ito M., Soyano T., Nishihama R. and Machida Y (2004). Mitotic cyclins stimulate the activity of c-Myb-like factors for transactivation of G2/M phase-specific genes in tobacco. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32979-32988. 10.1074/jbc.M403171200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall E. L., Bell M., Georlette D. and Botchan M. R. (2004). Dm-myb mutant lethality in Drosophila is dependent upon mip130: positive and negative regulation of DNA replication. Genes Dev. 18, 1667-1680. 10.1101/gad.1206604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall E. L., Lewis P. W., Bell M., Rocha M., Jones D. L. and Botchan M. R. (2007). Discovery of tMAC: a Drosophila testis-specific meiotic arrest complex paralogous to Myb-Muv B. Genes Dev. 21, 904-919. 10.1101/gad.1516607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghi L., Gutzat R., Futterer J., Laizet Y., Hennig L. and Gruissem W (2010). Arabidopsis RETINOBLASTOMA-RELATED is required for stem cell maintenance, cell differentiation, and lateral organ production. Plant Cell 22, 1792-1811. 10.1105/tpc.110.074591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudolf V., Barroco R., Engler Jde A., Verkest A., Beeckman T., Naudts M., Inze D. and De Veylder L. (2004). B1-type cyclin-dependent kinases are essential for the formation of stomatal complexes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 16, 945-955. 10.1105/tpc.021774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J. (2005). Floral dip: agrobacterium-mediated germ line transformation. Methods Mol. Biol. 286, 91-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K. A. and Bergmann D. C. (2014). Functional specialization of stomatal bHLHs through modification of DNA-binding and phosphoregulation potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15585-15590. 10.1073/pnas.1411766111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvoyes B., Ramirez-Parra E., Xie Q., Chua N. H. and Gutierrez C (2006). Cell type-specific role of the retinoblastoma/E2F pathway during Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant Physiol. 140, 67-80. 10.1104/pp.105.071027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell J. A., Wang Y., Riesenfeld S. J., Shekhar K., Regev A. and Schier A. F. (2018). Single-cell reconstruction of developmental trajectories during zebrafish embryogenesis. Science 360, eaar3131 10.1126/science.aar3131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler M., Nadeau J. and Sack F. D. (2000). Oriented asymmetric divisions that generate the stomatal spacing pattern in Arabidopsis are disrupted by the too many mouths mutation. Plant Cell, 12, 2075-2086 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S.-K., Qi X., Sugihara K., Dang J., Endo T. A., Miller K., Kim E.-D., Miura T. and Torii K (2018). MUTE directly orchestrates cell state switch and the single symmetric division to create stomata. Dev. Cell 45, 303-315.e5. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst R. J., Fujita H., Lee J. S., Rychel A. L., Garrick J. M., Kawaguchi M., Peterson K. M. and Torii K. U. (2015). Molecular framework of a regulatory circuit initiating two-dimensional spatial patterning of stomatal lineage. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005374 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M., Araki S., Matsunaga S., Itoh T., Nishihama R., Machida Y., Doonan J. H. and Watanabe A (2001). G2/M-phase-specific transcription during the plant cell cycle is mediated by c-Myb-like transcription factors. Plant Cell 13, 1891-1905. 10.1105/tpc.13.8.1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaoka M. M., Pillitteri L. J., Fujii H., Yoshida Y., Bogenschutz N. L., Takabayashi J., Zhu J.-K. and Torii K. U. (2008). SCREAM/ICE1 and SCREAM2 specify three cell-state transitional steps leading to arabidopsis stomatal differentiation. Plant Cell 20, 1775-1785. 10.1105/tpc.108.060848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Suzuki T., Iwata E., Nakamichi N., Suzuki T., Chen P., Ohtani M., Ishida T., Hosoya H., Muller S. et al. (2015). Transcriptional repression by MYB3R proteins regulates plant organ growth. EMBO J. 34, 1992-2007. 10.15252/embj.201490899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M., Udagawa M., Nishikubo N., Horiguchi G., Yamaguchi M., Ito J., Mimura T., Fukuda H. and Demura T (2005). Transcription switches for protoxylem and metaxylem vessel formation. Genes Dev. 19, 1855-1860. 10.1101/gad.1331305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampard G. R., MacAlister C. A. and Bergmann D. C. (2008). Arabidopsis stomatal initiation is controlled by MAPK-mediated regulation of the bHLH SPEECHLESS. Science 322, 1113-1116. 10.1126/science.1162263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau O. S., Davies K. A., Chang J., Adrian J., Rowe M. H., Ballenger C. E. and Bergmann D. C. (2014). Direct roles of SPEECHLESS in the specification of stomatal self-renewing cells. Science 345, 1605-1609. 10.1126/science.1256888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E., Lucas J. R., Goodrich J. and Sack F. D. (2014). Arabidopsis guard cell integrity involves the epigenetic stabilization of the FLP and FAMA transcription factor genes. Plant J., 78, 566-577. 10.1111/tpj.12516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Running M. P. and Meyerowitz E. M. (1997). TSO1 functions in cell division during Arabidopsis flower development. Development 124, 665-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos J. L., Lau O. S., Hachez C., Cruz-Ramirez A., Scheres B. and Bergmann D. C. (2014). Irreversible fate commitment in the Arabidopsis stomatal lineage requires a FAMA and RETINOBLASTOMA-RELATED module. Elife 3 10.7554/eLife.03271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau J. A. and Sack F. D. (2002). Control of stomatal distribution on the Arabidopsis leaf surface. Science 296, 1697-1700. 10.1126/science.1069596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T., Nakamura S., Tanaka K., Kawamukai M., Suzuki T., Nakamura K., Kimura T. and Ishiguro S (2008). Development of R4 gateway binary vectors (R4pGWB) enabling high-throughput promoter swapping for plant research. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 72, 624-629. 10.1271/bbb.70678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi-Ito K. and Bergmann D. C. (2006). Arabidopsis FAMA controls the final proliferation/differentiation switch during stomatal development. Plant Cell 18, 2493-2505. 10.1105/tpc.106.046136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley R. C., Huang S. C., Song L., Lewsey M. G., Bartlett A., Nery J. R., Galli M., Gallavotti A. and Ecker J. R. (2016). Cistrome and epicistrome features shape the regulatory DNA landscape. Cell 165, 1280-1292. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillitteri L. J., Sloan D. B., Bogenschutz N. L. and Torii K. U. (2007). Termination of asymmetric cell division and differentiation of stomata. Nature 445, 501-505. 10.1038/nature05467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadasivam S. and DeCaprio J. A. (2013). The DREAM complex: master coordinator of cell cycle-dependent gene expression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 585-595. 10.1038/nrc3556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijacic P., Wang W. and Liu Z (2011). Recessive antimorphic alleles overcome functionally redundant loci to reveal TSO1 function in Arabidopsis flowers and meristems. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002352 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siligato R., Wang X., Yadav S. R., Lehesranta S., Ma G., Ursache R., Sevilem I., Zhang J., Gorte M., Prasad K. et al. (2016). MultiSite gateway-compatible cell type-specific gene-inducible system for plants. Plant Physiol. 170, 627-641. 10.1104/pp.15.01246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J. Y., Leung T., Ehler L. K., Wang C. and Liu Z (2000). Regulation of meristem organization and cell division by TSO1, an Arabidopsis gene with cysteine-rich repeats. Development 127, 2207-2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Sijacic P., Xu P., Lian H. and Liu Z (2018). Arabidopsis TSO1 and MYB3R1 form a regulatory module to coordinate cell proliferation with differentiation in shoot and root. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E3045-E3054. 10.1073/pnas.1715903115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer A. K., Nowack M. K., Bouyer D., Zhao X., Harashima H., Naseer S., De Winter F., Dissmeyer N., Geldner N. and Schnittger A (2012). Retinoblastoma related1 regulates asymmetric cell divisions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24, 4083-4095. 10.1105/tpc.112.104620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimer A. K., Matos J. L., Sharma N., Patell F., Murray J. A. H., Dewitte W. and Bergmann D. C. (2018). Lineage- and stage-specific expressed CYCD7;1 coordinates the single symmetric division that creates stomatal guard cells. Development 145 10.1242/dev.160671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Hill M. C., Zhang M., Martin T. J., Morikawa Y., Wang S., Moise A. R., Wythe J. D. and Martin J. F. (2018). Hippo signaling plays an essential role in cell state transitions during cardiac fibroblast development. Dev. Cell 45, 153-169 e156. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z., Lee E., Lucas J. R., Morohashi K., Li D., Murray J. A., Sack F. D. and Grotewold E (2010). Regulation of cell proliferation in the stomatal lineage by the Arabidopsis MYB FOUR LIPS via direct targeting of core cell cycle genes. Plant Cell 22, 2306-2321. 10.1105/tpc.110.074609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin K., Ueda M., Takagi H., Kajihara T., Sugamata Aki S., Nobusawa T., Umeda-Hara C. and Umeda M (2014). A dual-color marker system for in vivo visualization of cell cycle progression in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 80, 541-552. 10.1111/tpj.12652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.