Abstract

Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) is an uncommon neurological complication in pregnancies complicated with hyperemesis due to thiamine deficiency. In women with hyperemesis, inadvertent glucose administration prior to thiamine supplementation triggers the development of neurological manifestations. Delay in the diagnosis can lead to maternal morbidity, and in one-third of cases may lead to persistence of some neurological deficit. With early recognition and thiamine supplementation, complete recovery is reported. We report a case of WE complicating a case of triplet pregnancy with hyperemesis gravidarum, which highlights the importance of early recognition and treatment, resulting in complete recovery as in the index case.

Keywords: obstetrics and gynaecology, pregnancy

Background

Hyperemesis gravidarum complicates 0.3%–2.0% of pregnancies and is characterised by intractable vomiting, leading to dehydration and weight loss.1 Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) is an uncommon neurological complication in these women as a result of thiamine deficiency from a combination of poor nutritional status, frequent vomiting and increased metabolic requirements during pregnancy. We report a case of WE complicating a case of triplet pregnancy with hyperemesis gravidarum who had a complete recovery.

Case presentation

A 20-year-old primigravida with triplets, in her 23rd week of pregnancy, presented to the emergency department with excessive vomiting for 3 weeks. Nausea and vomiting were present since confirmation of pregnancy and were managed in the primary health centre. In spite of receiving antiemetic (promethazine 25 mg every 8 hours), her vomiting became intolerable, which led to weight loss and has affected her routine daily activities for 3 weeks. On admission, she was afebrile and dehydrated, with a pulse rate of 112 beats per minute and blood pressure of 110/70 mm Hg. Obstetric examination showed a uterine fundal height of 32 weeks, and multiple fetal parts were palpable.

She was managed medically with (1) fluid correction (with Hartmann’s solution and sodium chloride 0.9%) and (2) antiemetics (promethazine 25 mg every 8 hours intravenously and ondansetron 4 mg intravenously every 8 hours). In view of the short cervical length (1.5 cm), she received weekly injection of 17 alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate (250 mg intramuscularly). Her urine culture and high vaginal swab sent at the time of admission were reported to have normal flora.

Ten days later, she delivered triplets weighing 508 g, 429 g and 389 g. All succumbed to extreme prematurity-related complications within an hour of birth. She developed vomiting again on the fourth postnatal day and felt numbness and weakness in the extremities. She was given oral glucose, by her relatives, following which she became irritable and started developing weakness in all four limbs. Within a time frame of 4 hours, she was confused and unable to speak, and was noted to have ophthalmoplegia and quadriparesis. Serum electrolytes and blood sugar were normal.

Investigations

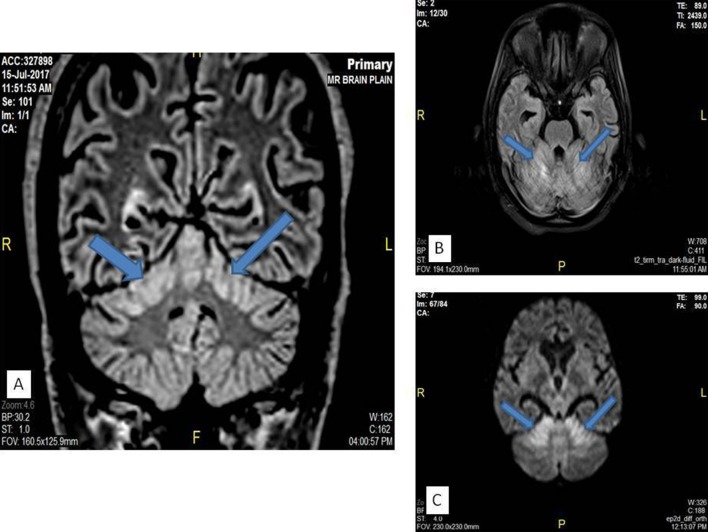

Her blood sugar was 93 mg/dL, serum sodium was 132.7 mEq/dL and serum potassium was 3.5 mEq/dL. Urine ketones were trace. CT venogram, done to rule out cerebrovenous thrombosis, was normal. MRI showed bilateral cerebellar hyperintensities with mild diffusion restriction (figure 1).

Figure 1.

MRI findings in the patient as denoted by the arrows. (A) Coronal FLAIR image showing hyperintensity in the bilateral superior cerebellar hemispheres. (B) Axial FLAIR image showing hyperintensity in the bilateral superior cerebellar hemispheres. (C) Axial diffusion-weighted image showing areas of diffusion restriction in the bilateral superior cerebellar hemispheres. FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery.

Treatment

A diagnosis of WE was made after consultation with the neurologist, in view of the signs suggestive of thiamine deficiency (hyperemesis). She was started on thiamine injection once daily (200 mg in 100 normal saline intravenous infusion). Clinically neurological improvement was noted within 48 hours, and she recovered completely over a week. Septic screen came positive for growth of Escherichia coli in the cervical and blood cultures. She was given amikacin injection (375 mg intravenously 12-hourly for 7 days). Thiamine supplementation was stopped, and she was discharged on the 14th day.

Outcome and follow-up

After 6 weeks, on postnatal follow-up, she was neurologically normal.

Discussion

WE was first described by Carl Wernicke in 1881 as polioencephalitis haemorrhagica superioris with a clinical triad of ataxia, confusion and ophthalmoplegia resulting from thiamine deficiency.1 Thiamine pyrophosphate is an essential cofactor for the enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism (Krebs cycle) in tissues with high metabolic demands, especially those dependent on aerobic respiration. Thus, deficiency in such tissues, such as neural parenchyma, results in cytotoxic oedema, glial cell proliferation, neuronal demyelination, cellular degeneration, and ultimately cell death from necrosis or apoptosis. The daily requirement of thiamine increases to 1.5 mg during pregnancy, and usually the stores last for around 18 days.2

WE secondary to hyperemesis gravidarum is uncommon (0.1%–0.5%).3 It is precipitated by inadequate fluid correction or inadvertent glucose administration prior to thiamine supplementation, leading to neurological manifestations, as seen in the present case. Diagnosis is primarily based on clinical features. As per the European Federation of Neurological Societies guidelines, two of the following four features are required to make a diagnosis: (1) conditions leading to dietary deficiency, such as alcoholism and hyperemesis; (2) eye signs such as nystagmus, gaze palsy or ophthalmoplegia; (3) evidence of cerebellar dysfunction, such as ataxia, unsteadiness or dysdiadokokinesia; and (4) either altered mental state or mild mental impairment.4 This can be supported by MRI findings which include bilateral and symmetrical involvement of the medial thalami, tectum of the midbrain and periaqueductal regions along the third and fourth ventricles.4 5 In our case, hyperemesis would have led to the thiamine-deficient state, with further fall in the stores occurring due to vomiting, possible due to sepsis in the postnatal state. Inadvertent administration of glucose would have led to the development of WE, and the MRI revealed T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensity in the superior portions of the bilateral cerebellar hemispheres. This region is a known area of atypical involvement in WE.6

Optimal dose, number of daily doses or duration of thiamine therapy are still unclear. Intravenous thiamine supplementation is preferred, with the dose ranging from 100 mg to 500 mg tried in non-alcohol-related WE. Since thiamine deficiency is not clinically apparent in hyperemesis, this supplementation needs to be continued until the patient does not have any further improvement clinically.4 5

Complete recovery is reported in cases where early recognition and thiamine supplementation were instituted.7 However, nearly one-third of the cases may persist to have some neurological deficit.8 Others had one or more of residual neurological symptoms, such as nystagmus, ataxia, memory disturbance, coordination difficulties, vertigo or paraesthesia.

Learning points.

In women with hyperemesis, inadvertent glucose administration prior to thiamine supplementation triggers the development of neurological manifestations.

This case highlights the importance of thiamine supplementation to women with prolonged vomiting during pregnancy, especially before starting oral or parenteral nutrition.

High degree of clinical suspicion coupled with timely institution of thiamine supplementation may help in the early and complete recovery from Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Contributors: TA, LC, PPN, DB and AK conceived the idea and performed the search. TA, LC and AK wrote the first draft. LC, DB and PPN reviewed and revised the final draft. AK, DB, PPN and LC reviewed and commented on the final draft.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Goodwin TM. Hyperemesis gravidarum. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2008;35:401–17. 10.1016/j.ogc.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chiossi G, Neri I, Cavazzuti M, et al. Hyperemesis gravidarum complicated by Wernicke encephalopathy: background, case report, and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2006;61:255–68. 10.1097/01.ogx.0000206336.08794.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nelson-Piercy C. Treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. When should it be treated and what can be safely taken? Drug Saf 1998;19:155–64. 10.2165/00002018-199819020-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gascón-Bayarri J, Campdelacreu J, García-Carreira MC, et al. [Wernicke’s encephalopathy in non-alcoholic patients: a series of 8 cases]. Neurologia 2011;26:540–7. 10.1016/j.nrl.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antunez E, Estruch R, Cardenal C, et al. Usefulness of CT and MR imaging in the diagnosis of acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998;171:1131–7. 10.2214/ajr.171.4.9763009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim JE, Kim TH, Yu IK, et al. Diffusion-Weighted MRI in Recurrent Wernicke’s Encephalopathy: a remarkable cerebellar lesion. J Clin Neurol 2006;2:141–5. 10.3988/jcn.2006.2.2.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zara G, Codemo V, Palmieri A, et al. Neurological complications in hyperemesis gravidarum. Neurol Sci 2012;33:133–5. 10.1007/s10072-011-0660-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Di Gangi S, Gizzo S, Patrelli TS, et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy complicating hyperemesis gravidarum: from the background to the present. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25:1499–504. 10.3109/14767058.2011.629253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]