ABSTRACT

Objective:

The primary objective of this scoping review was to examine and map the range of neurophysiological impacts of human touch and eye gaze, and consider their potential relevance to the therapeutic relationship and to healing.

Introduction:

Clinicians, and many patients and their relatives, have no doubt as to the efficacy of a positive therapeutic relationship; however, much evidence is based on self-reporting by the patient or observation by the researcher. There has been little formal exploration into what is happening in the body to elicit efficacious reactions in patients. There is, however, a growing body of work on the neurophysiological impact of human interaction. Physical touch and face-to-face interaction are two central elements of this interaction that produce neurophysiological effects on the body.

Inclusion criteria:

This scoping review considered studies that included cognitively intact human subjects in any setting. This review investigated the neurophysiology of human interaction including touch and eye gaze. It considered studies that have examined, in a variety of settings, the neurophysiological impacts of touch and eye gaze. Quantitative studies were included as the aim was to examine objective measures of neurophysiological changes as a result of human touch and gaze.

Methods:

An extensive search of multiple databases was undertaken to identify published research in the English language with no date restriction. Data extraction was undertaken using an extraction tool developed specifically for the scoping review objectives.

Results:

The results of the review are presented in narrative form supported by tables and concept maps. Sixty-four studies were included and the majority were related to touch with various types of massage predominating. Only seven studies investigated gaze with three of these utilizing both touch and gaze. Interventions were delivered by a variety of providers including nurses, significant others and masseuses. The main neurophysiological measures were cortisol, oxytocin and noradrenaline.

Conclusions:

The aim of this review was to map the neurophysiological impact of human touch and gaze. Although our interest was in studies that might have implications for the therapeutic relationship, we accepted studies that explored phenomena outside of the context of a nurse-patient relationship. This allowed exploration of the boundary of what might be relevant in any therapeutic relationship. Indeed, only a small number of studies included in the review involved clinicians (all nurses) and patients. There was sufficient consistency in trends evident across many studies in regard to the beneficial impact of touch and eye gaze to warrant further investigation in the clinical setting. There is a balance between tightly controlled studies conducted in an artificial (laboratory) setting and/or using artificial stimuli and those of a more pragmatic nature that are contextually closer to the reality of providing nursing care. The latter should be encouraged.

Keywords: Gaze, healing, neurophysiological, therapeutic relationship, touch

Introduction

The purpose of the review was to examine the connection between two distinct research fields. The first field is aligned to the social sciences and examines the importance of human interaction and positive therapeutic relationships for healing and the delivery of fundamental care.1 The second research field is aligned to the natural sciences, and investigates the neurophysiological impact of touch and eye gaze during human interaction. Although arising from different research domains, both bodies of work are strongly connected, with touch and gaze being key elements of human interaction that have the potential to influence therapeutic relationships, healing and patients’ experiences of fundamental care delivery. The connection of these bodies of work is further emphasized by the shared variables of trust and positivity as relevant mediators of the impact of human interaction.

Fundamental care refers to the essential elements of care that every patient requires regardless of their clinical condition or the setting in which they are receiving care. These elements of care can be physical (e.g. nutrition, hydration, elimination and hygiene), psychosocial (e.g. respect, dignity, privacy and cultural safety) or relational in nature (e.g. empathy and compassion).1 Given the growing evidence that these fundamentals are being poorly executed globally, there is increasing emphasis on how they can best be delivered in clinical practice.2-10 Research is beginning to acknowledge that a positive, trusting nurse-patient relationship is integral to the delivery of high-quality, person-centered fundamental care.1,11 However, the specific neurophysiological mechanisms through which this positive relationship impacts patient care and experiences is largely unknown and unexplored.

In addition to work on fundamental care, there is a large body of work on the importance of an empathic, therapeutic relationship for healing, patient health, resilience and hope.12-14 This therapeutic relationship might involve multiple “actors”, given that patients can interact with multiple health professionals in any healthcare episode. Specific studies focusing on the therapeutic relationship include studies on connectedness,15 social influences on healing and stress,16,17 meta-analyses of noncontact healing studies18 and reviews of the effect of interpersonal touch on patients19,20 and specific cells.21

There are also studies and literature reviews on the role of trust in health professional (particularly nurse)-patient relationships22,23 and the impact of increasing technological interaction on this therapeutic relationship.24,25 These studies demonstrate the increased capacity for hope displayed by the patient when there is a high trust relationship and personal interaction between the patient and nurse/medical practitioner.26,27 The observed interactions and interconnections that are considered to be relevant for improving the healing capacity of patients in these circumstances include the display of genuine empathy, compassion, direct eye contact and physical touch.

Whilst clinicians, and many patients and relatives, are in no doubt as to the efficacy of a positive therapeutic relationship, much evidence is based on self-reporting by the patient or observation by the researcher.23,24 There is, however, a growing body of work on the neurophysiological impact of human interaction. Physical touch and face-to-face interaction, entailing eye gaze and retinal eye lock, are two types of contact that produce neurophysiological effects on the body.20,28,29

There are a growing number of studies investigating the neurophysiological impact of physical touch. Such studies have examined the cortical dynamics of both discriminative (discrimination of stimuli) and affective (pleasant, gentle stroking) touch,30-34 and the way in which the brain registers (codes) affective touch.35-38 The neurophysiological response to touch includes the release of specific chemicals and neurotransmitters that lead to neuroendocrine effects; vagal stimulation; reduction of stress, pain and depression; and enhancement of immunity.20,39-42 Affective touch also appears to lessen allostatic load (i.e. stress) in critically ill patients,20 due to the positive effects on pathophysiological processes aggravated by stress, such as immune and neuroendocrine derangements and inflammation.28,39 There is recent evidence of an interoceptive effect of affective touch that aids rehabilitation through alterations to the insular cortex and limbic system.43

Affective touch is transmitted primarily through stimulation of the nerve's unmyelinated C-fibers, the impact of which is beneficial to healing.29 Affective touch is represented in areas of the brain that are closely related to the perception of emotion and empathy, and this affective-emotional pathway runs in part through the spinomesencephalic tract, engaging the amygdala, insula and anterior cingulate cortex.29 Resultant neurophysiological reactions can mediate the perception of touch, and are shown to be beneficial to the healing process, as well as having a positive effect on a patient's capacity for pain management29,44 and a number of physiological outcomes, including changes to autonomic innervation through repetition of affective stimulation.20

One of the most powerful human interactions is face-to-face contact involving eye gaze. The interaction between trusted individuals creates a neural duet between brains due to the reciprocal firing of the brain's social networking areas, with a powerful effect on the level of trust and empathy as well as a positive attitudinal shift.45 Face-to-face contact involves the activation of mirror and spindle neurons.33,46-48 When interacting with trusted others a number of chemicals are released including oxytocin and vasopressin,49,50 both of which help to lower the physiological stress response and aid growth and wound healing.51 Social interaction becomes an interactive process of positive feedback whereby increased levels of oxytocin in turn encourage even greater levels of gaze to the eye region of human faces.50 This dynamic further increases the level of trust and empathy between the interacting parties.

When there is sufficient trust and positivity, a positive feedback effect can occur, which stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system and releases immune system chemicals that enable neuroplasticity and neurogenesis to occur.52,53 These same chemicals are involved in immune system strength and changes to hormonal responses triggered by stress, pain signalling and integration. Each of these are directly related to healing and resilience through such mechanisms as modulating the interplay of lymphocytes that produce antibodies54 and triggering hormone and neuropeptide changes that mediate emotions.13,55

Eye gaze and retinal eye lock between an anxious person and a trusted “other” has a direct effect on the synchronization of the right brain hemispheres56,57 and the quietening of the sympathetic nervous system and amygdala,58 increasing the ability to deal with trauma. Thus, it enables the caregiver or trusted “other” to “soothe”.49,58 This “eye contact effect” modulates activity in structures in the social brain network,59 aiding communicative intention and affective arousal. There is growing evidence of the link between these neurophysiological reactions and a decreased level of morbidity and mortality through such changes as an increased capacity for hope,13,60 the capacity to reframe vulnerability and deal with trauma,61,62 and neurophysiological reactions related to the placebo effect.63

In summary, touch and face-to-face interaction with trusted others have a number of neurophysiological effects that are relevant to the therapeutic relationship. These neurophysiological effects are impacted by the quality of the relationship shared by the individuals. Trust and empathy, in particular, appear to be mediators given they have a profound effect on the body's generation and/or secretion of beneficial chemicals, such as serotonin.

This review maps the research literature on interventions that directly or indirectly replicate aspects of a therapeutic relationship using touch and/or eye gaze. This research literature arguably complements the existing body of research, indicating that therapeutic relationships can have a positive impact on patients, particularly in relation to the delivery of fundamental care. Research evaluating objective neurophysiological measures might provide further insight as to why and how this positive impact occurs.

A search of the Cochrane Library, the JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports (JBISRIR) and PubMed revealed a very large number of systematic reviews primarily concerned with the effects of massage and other forms of touch. Typically these reviews were condition specific such as the impact on lower back pain64 or prevention of pressure ulcers.65 These, and many other systematic reviews, typically examined clinical outcomes and not neurophysiological outcomes. One Cochrane systematic review did consider neurophysiological outcomes but was narrowly focused on massage for mental and physical health in infants under the age of six months.66 One scoping review was identified that mapped massage studies that measured neurophysiological impacts, but only in relation to blood pressure.67

The objectives, inclusion criteria and methods of analysis for this review were specified in advance and documented in a protocol.68

Review question/objective

The specific review question for this review was: what are the neurophysiological impacts of human touch and eye gaze that have the potential to influence healing and the therapeutic relationships?

The objective of this scoping review was to examine and map the range of neurophysiological impacts of human touch and eye gaze, and explore possible links to and implications for the therapeutic relationship and healing. Touch and gaze are two central components of human interaction. Understanding the neurophysiological impact of touch and gaze might provide insights in to how these components of interaction can be used to enhance relationships in a therapeutic context. Our intention was not to only include studies that overtly stated a link between touch or gaze and the impact on the therapeutic relationship and healing. This would have been too restrictive. Our objective was to look broadly at studies that measured the neurophysiological impact of touch and gaze and consider: the contexts in which these occurred; who received the touch or gaze and who provided it; what were the variants of touch and gaze; and what was being measured. In keeping with the purpose of a scoping review, this information allowed us to explore and map this emerging research field.

Inclusion criteria

Participants

This scoping review considered studies that included cognitively intact human subjects of any age. Patients who were heavily sedated or unconscious were excluded.

Concept

This scoping review investigated a number of areas related to the neurophysiology of human interaction (e.g. touch, eye gaze) and their potential connection to building a useful therapeutic relationship. The concept/s examined included:

Neurophysiology of touch

Neurophysiology of eye gaze

Neurophysiological impacts on healing

Neurophysiology of care

Therapeutic relationship.

Specifically, we considered who received the touch or gaze and who provided it; what the variants of touch and gaze were; and what outcomes were being measured.

Context

This scoping review considered studies that examined, in either clinical or laboratory settings, the neurophysiological impacts of touch and eye gaze, and which have potential links to the therapeutic relationship. Clinical settings included acute care, long-term care and community care, including the home.

Types of studies

This scoping review considered both experimental and quasi-experimental study designs including: randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, before and after studies and interrupted time-series studies. In addition, analytical observational studies including but not limited to prospective and retrospective cohort studies and case-control studies were considered for inclusion. Only quantitative studies were included as the aim was to examine objective measures of neurophysiological changes as a result of human touch and gaze.

Methods

This scoping review adopted the methodology for Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scoping reviews as described in the JBI Reviewers’ Manual.69,70

Search strategy

A three-step search strategy was utilized for this review. An initial limited search of Scopus, PubMed and CINAHL was undertaken, followed by an analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract, and of the index terms used to describe the articles. A second search using all identified keywords and index terms was then undertaken across all included databases. Thirdly, the reference list of all identified reports and articles were searched for additional studies. Only published studies in English were considered for inclusion in this review. The decision not to search for unpublished papers was due to the large amount of results from searching the databases of published studies, making additional imprecise searches in the gray literature impractical. There were no date restrictions.

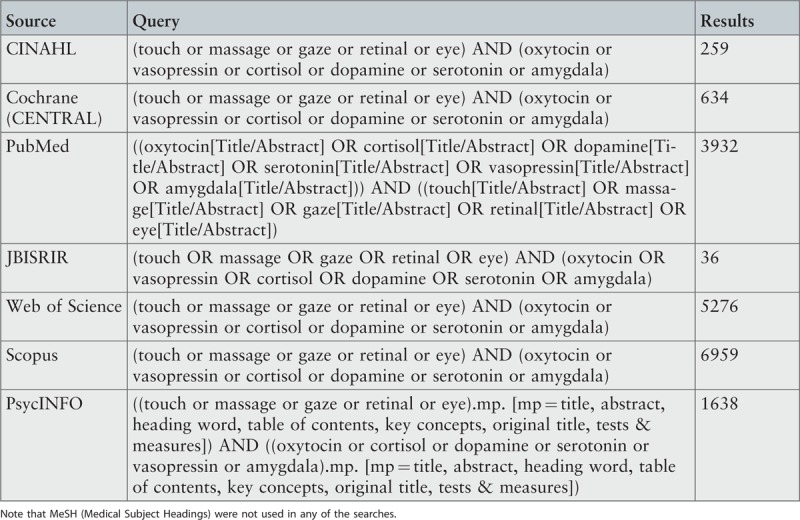

The databases searched included: CINAHL, PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Scopus, PsycINFO and Web of Science. Results of all searches are provided in Appendix I.

Initial keywords used were: gaze, healing, neurophysiological, therapeutic relationship, touch.

Study selection

All searches were imported into Endnote X8 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) and all title and abstracts were reviewed by two reviewers independently. Full-text of studies were then retrieved and reviewed by two reviewers independently. All discrepancies in selection were resolved through discussion.

Extraction of results

Data were extracted from papers included in the scoping review by two independent reviewers using the data extraction tool specified in the review protocol.68 The data extracted included specific details about the populations, concept, context and study methods of significance to the scoping review question and specific objectives. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Data mapping

The extracted data are presented in both diagrammatic and tabular form as per scoping review guidelines, including mind-maps of the various aspects of the study and how they interrelate. A narrative summary accompanies the tabulated and diagrammatic results.

Results

Description of studies

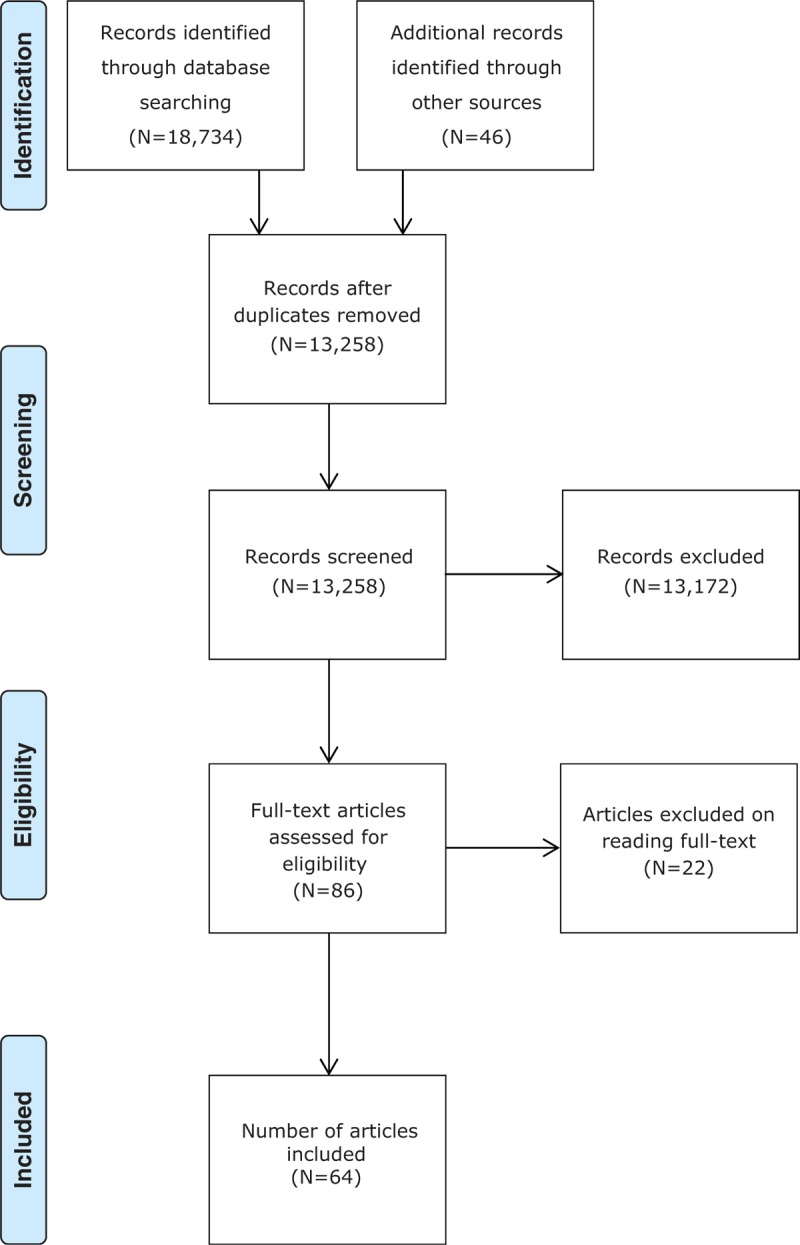

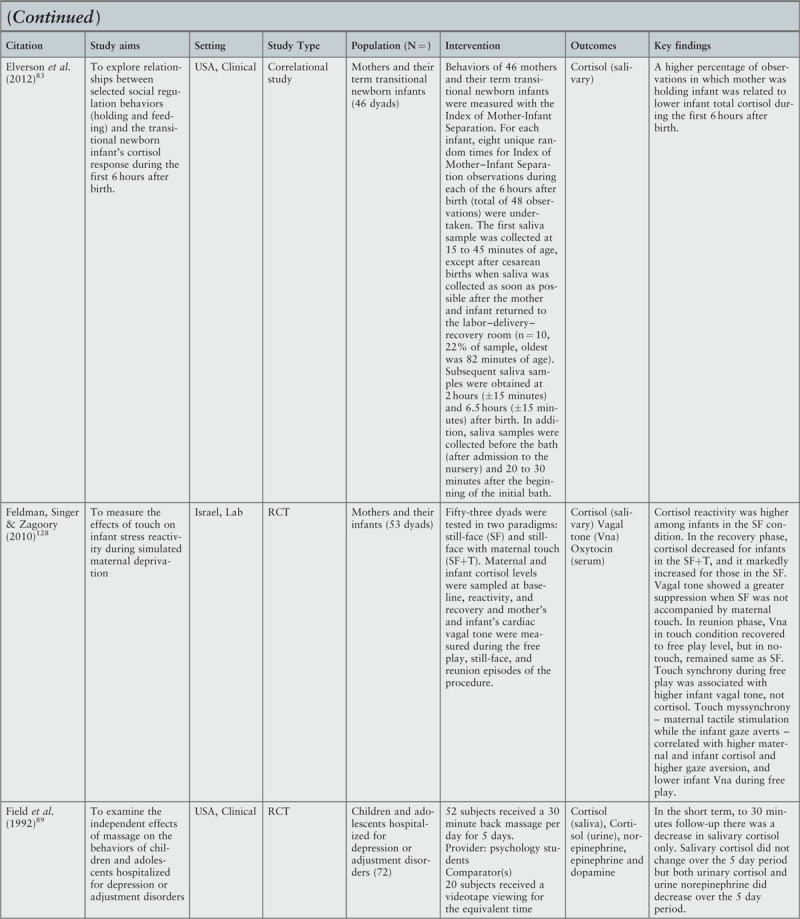

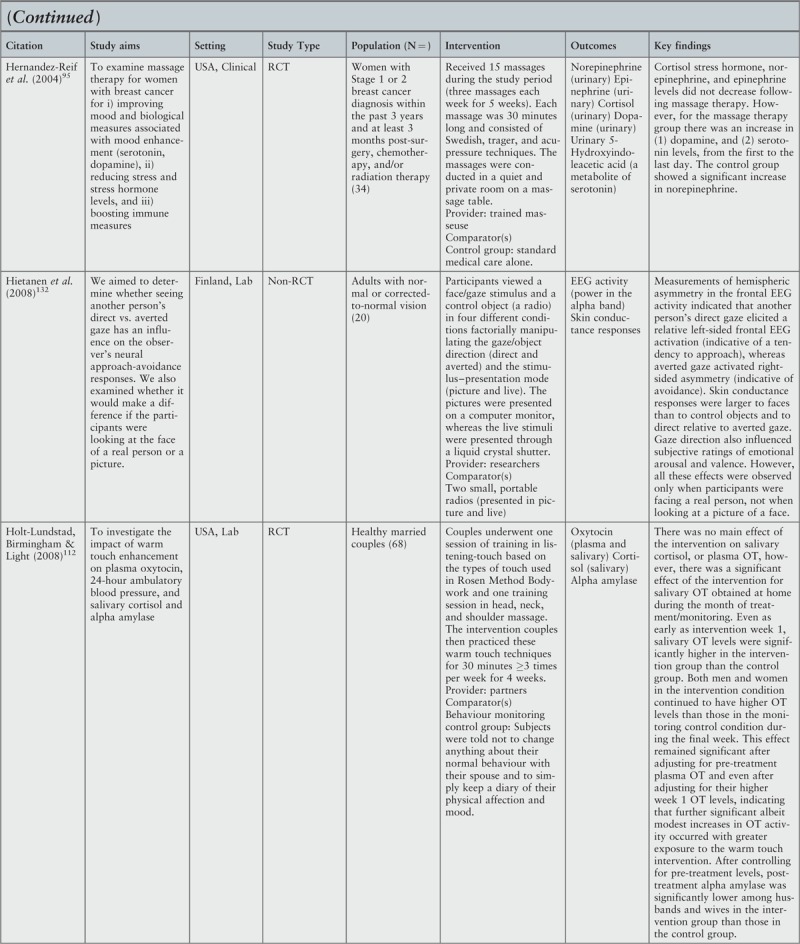

The initial search of all databases was conducted on 12–13 November 2015 and updated in February 2017. The search strategy was deliberately sensitive and therefore resulted in a large number of studies identified. Database searches identified 18,734 records. Other sources, primarily reference lists of included studies, provided a further 46 records. After removal of duplicates and screening of title and abstracts, 86 studies were retrieved in full text and 22 were then excluded based on inclusion criteria (See Appendix II). A total of 64 studies have been included in the review. The PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1 describes the flow of decisions for inclusion of studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for the scoping review process71

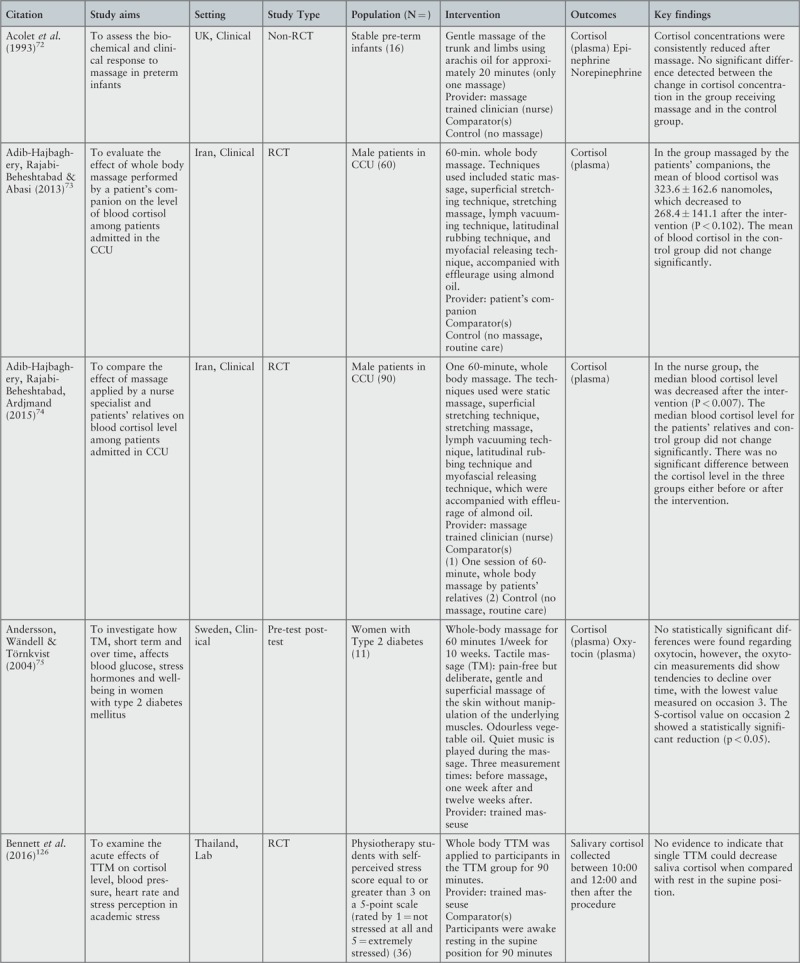

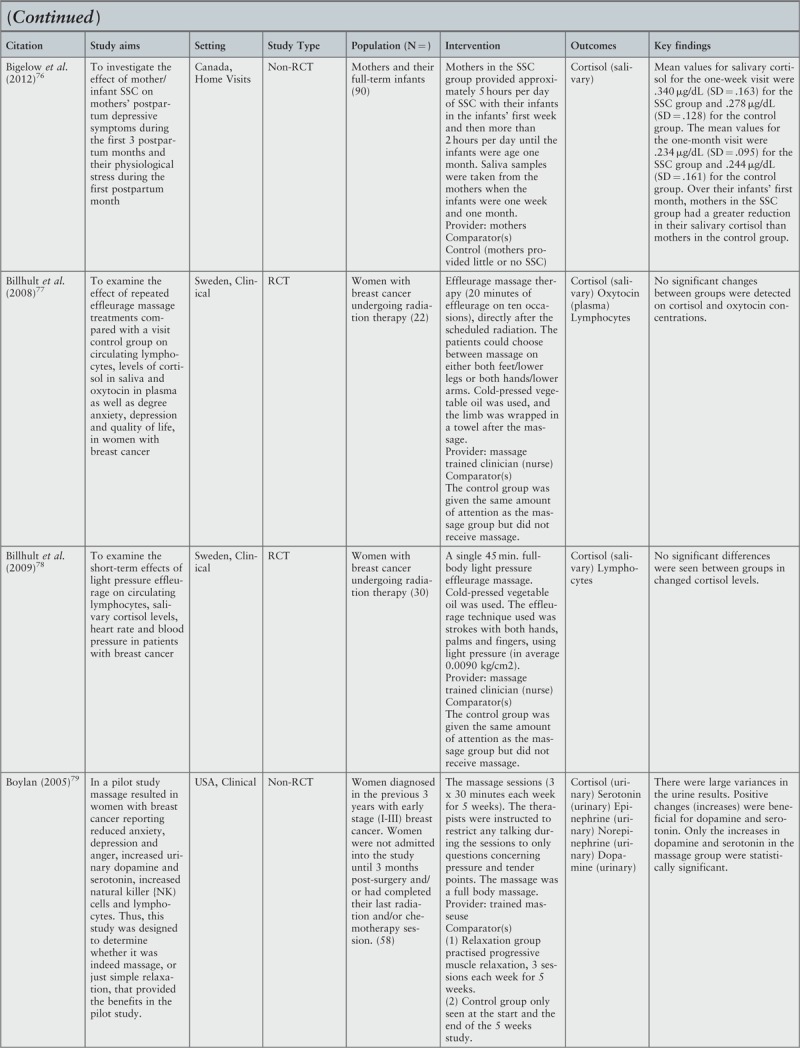

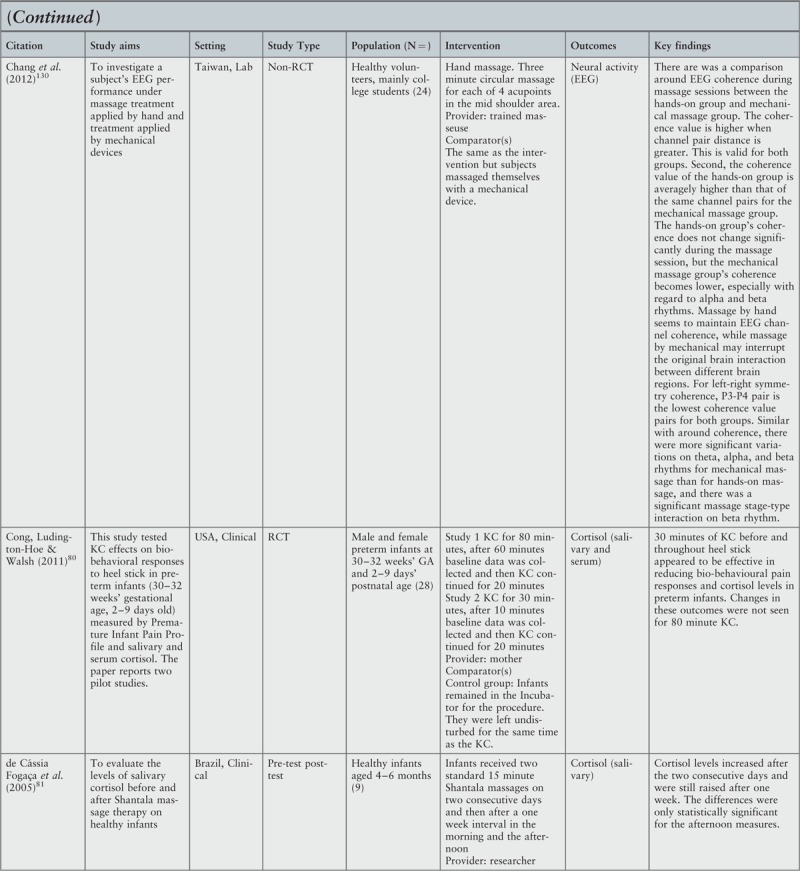

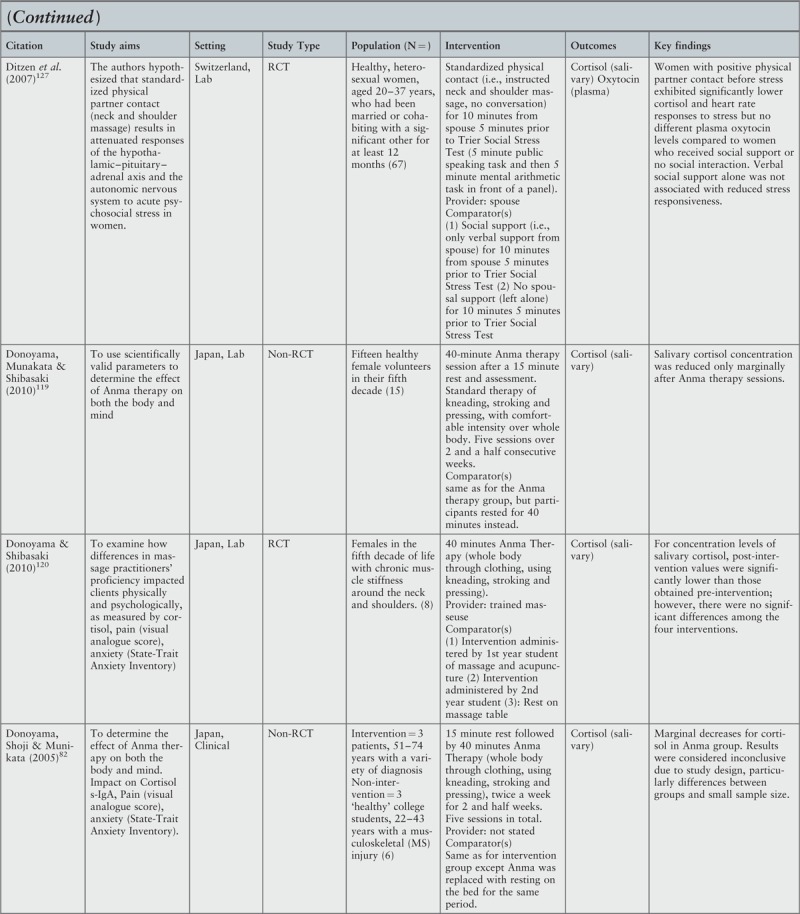

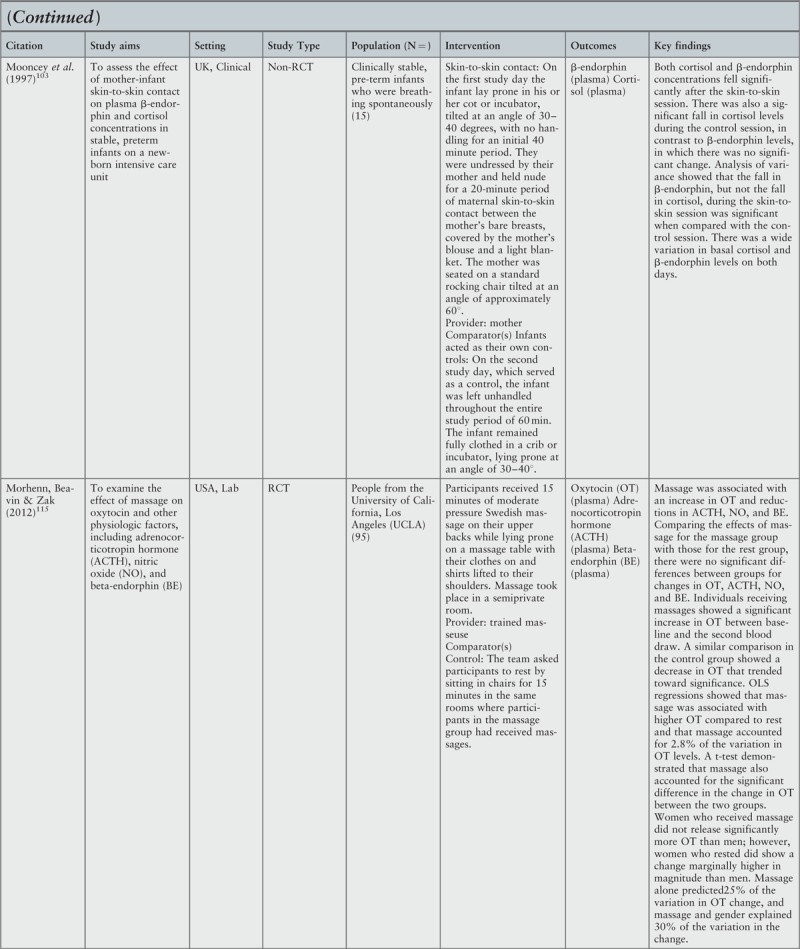

Characteristics of included studies

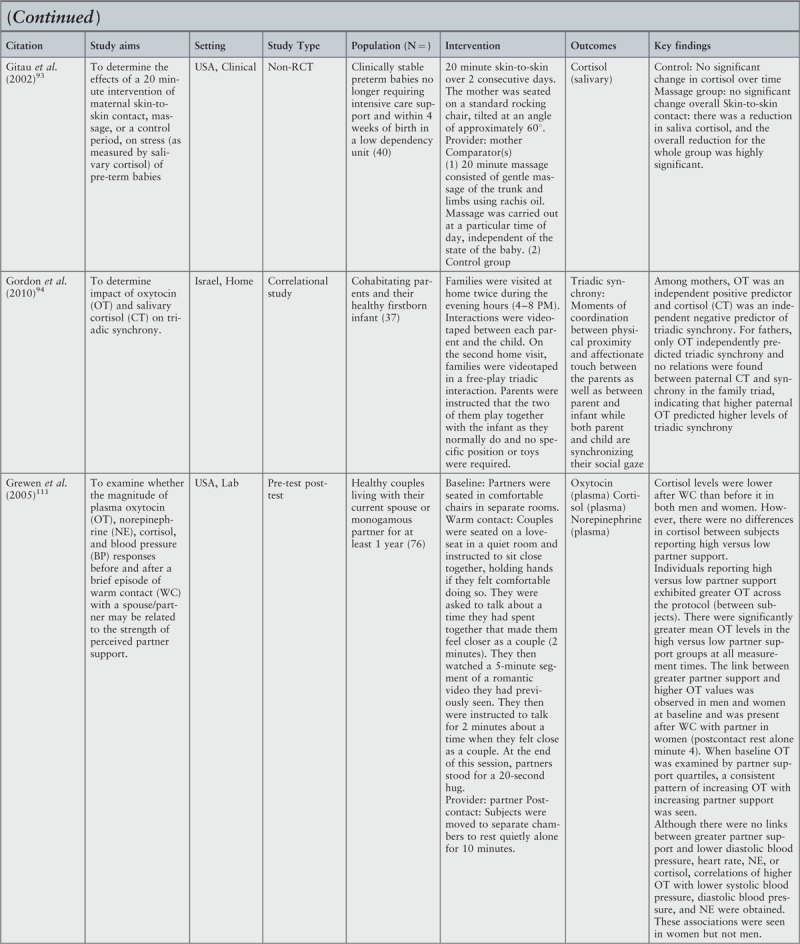

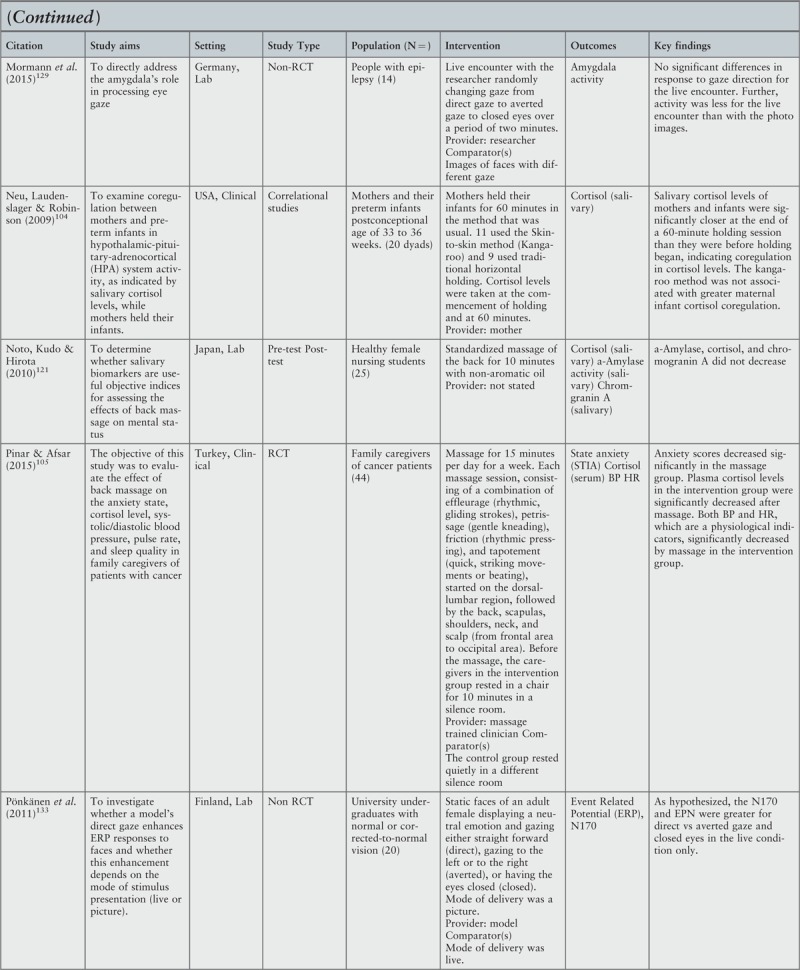

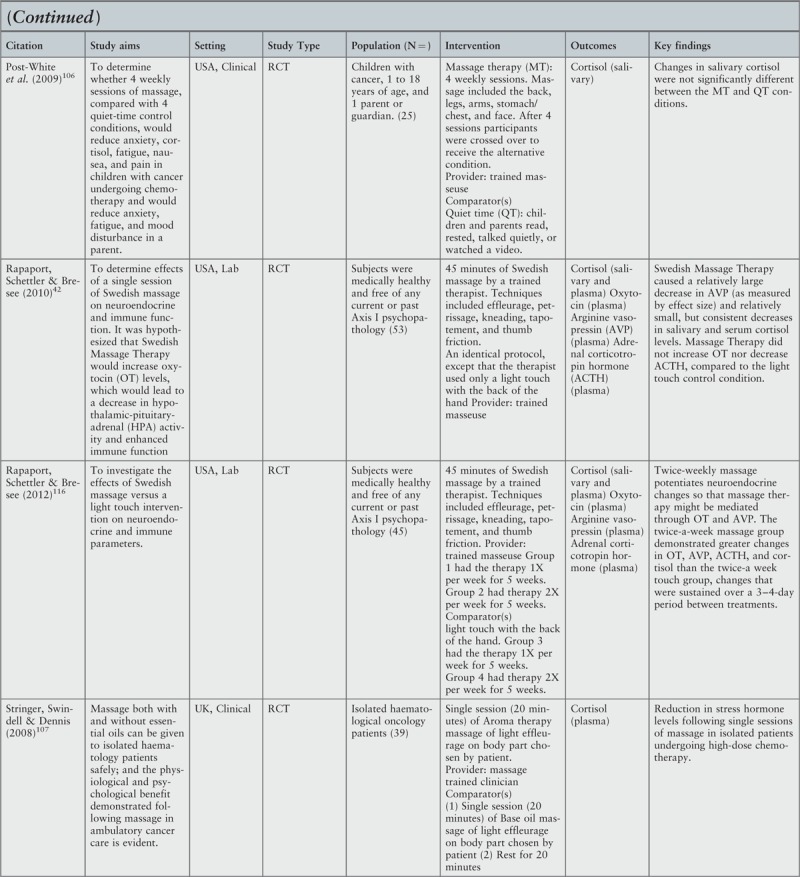

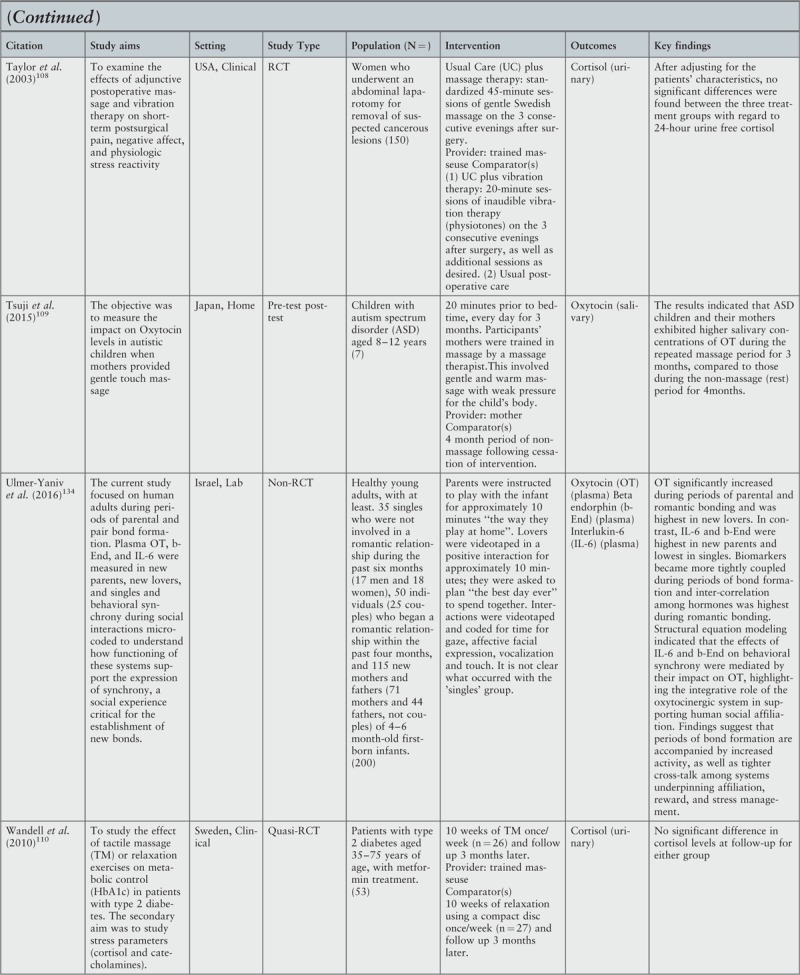

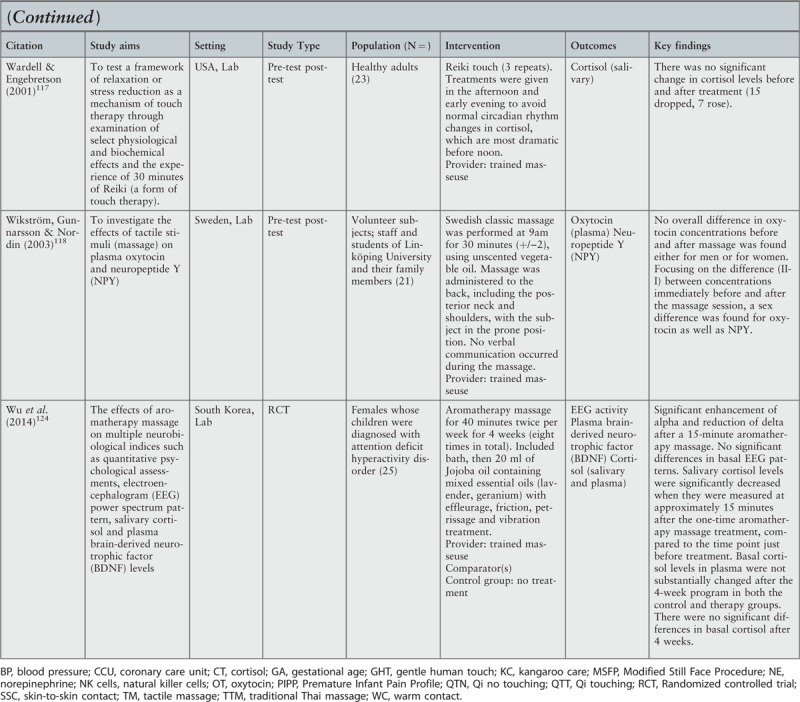

Of the 64 studies included in the review (Table 1), most (61%) were set in the clinical environment,72-110 with the vast majority of studies conducted in the US (39%),42,79,80,83-90,93,95,97,98,104,106,108,111-117 Sweden (13%),75,77,78,99,100,102,110,118 Japan (9%),82,91,109,119-121 South Korea96,122-124 and the UK (6% each).72,103,107,125 Nearly half of the studies were randomized controlled trials,42,73,74,77,78,80,84-90,95,98,99,101,105-108,112,115,116,120,123,124,126-128 and there were slightly fewer studies involving patients (45%)72-75,77-80,82,84-87,89,90,92,95-99,101,103,106-108,110,113,129 as opposed to healthy participants. The largest group of patients were those with cancer.77-79,95,101,106,107 Fifty-seven studies (89%) investigated “touch” as an intervention,42,72-93,95-124,126,127,130,131 four (6%) investigated the effect of “gaze”,125,129,132,133 two (3%) investigated “touch and gaze” combined94,128 and one study (2%) investigated touch and gaze with the addition of vocalization and facial expression.134 It should be noted, that although our aim was to identify studies that addressed the neurophysiological impact of touch and gaze in relation to healing there were no studies identified that addressed this directly.

Table 1.

Overview of included studies

| Category | Variable | n | % |

| Setting | Clinical (including acute, long term community and home care) | 39 | 61 |

| Laboratory | 25 | 39 | |

| USA | 25 | 39 | |

| Sweden | 8 | 13 | |

| Japan | 6 | 9 | |

| South Korea | 4 | 6 | |

| UK | 4 | 6 | |

| Israel | 3 | 5 | |

| Australia | 2 | 3 | |

| Country | Finland | 2 | 3 |

| Germany | 2 | 3 | |

| Iran | 2 | 3 | |

| Brazil | 1 | 2 | |

| Canada | 1 | 2 | |

| Switzerland | 1 | 2 | |

| Taiwan | 1 | 2 | |

| Thailand | 1 | 2 | |

| Turkey | 1 | 2 | |

| Randomized Controlled Trials | 31 | 48 | |

| Non-randomized controlled trials | 17 | 27 | |

| Study design | Pre-test post-test | 7 | 11 |

| Case-Series | 7 | 11 | |

| Other | 2 | 3 | |

| Population | Healthy | 35 | 55 |

| Patients | 29 | 45 | |

| Touch | 57 | 89 | |

| Intervention | Gaze | 4 | 6 |

| Touch and gaze | 2 | 3 | |

| Touch, gaze, vocalisation, facial expression | 1 | 2 |

The detailed characteristics of all included studies are provided in Appendix III.

Review findings

Interventions and intervention sub-types

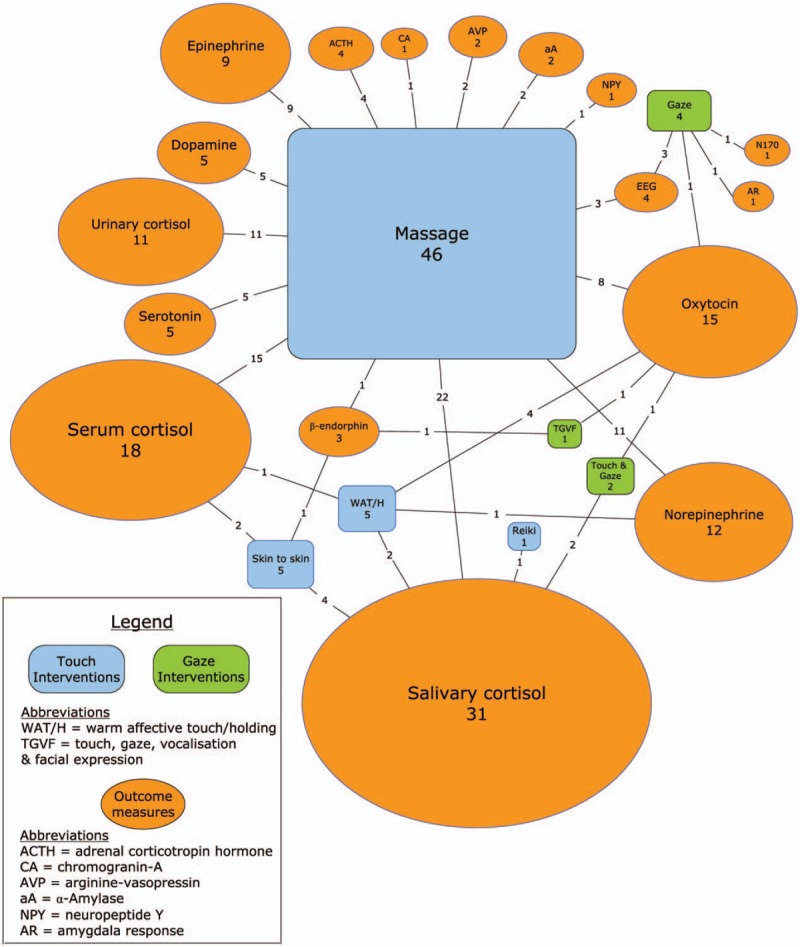

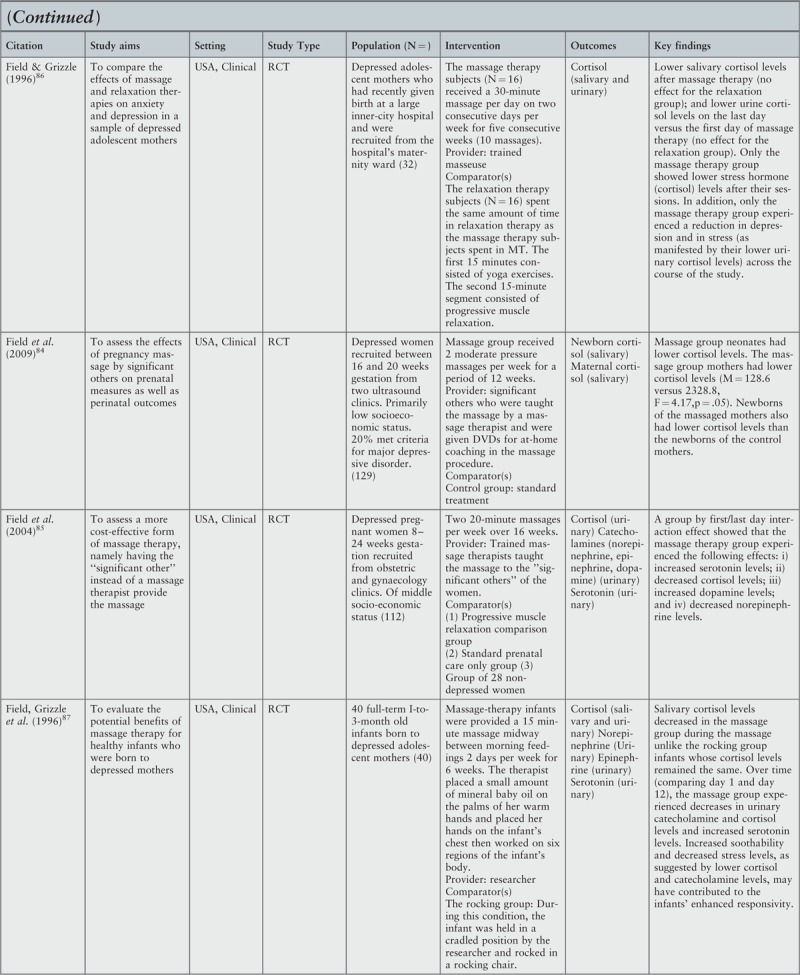

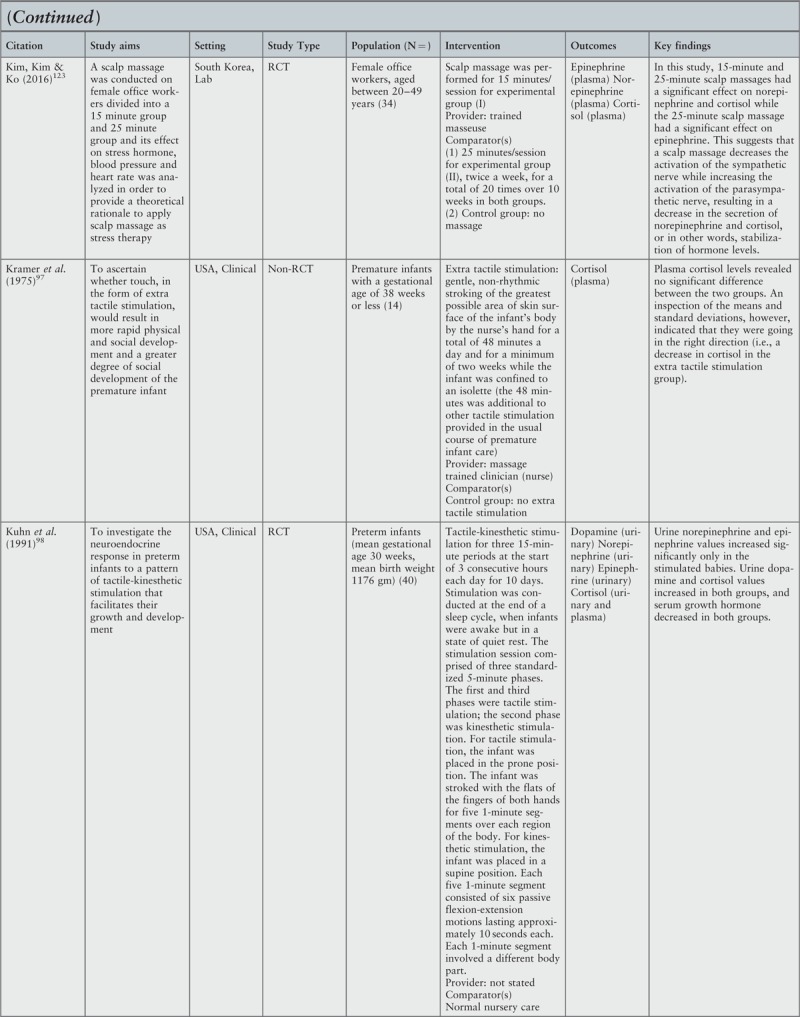

Figure 2 maps the included studies showing the numbers of studies investigating each of the intervention types, and for each of the intervention sub-types. The sub-types were derived iteratively as part of the mapping process.

Figure 2.

Mapping of intervention types and outcome measures (values correspond to the number of studies as does the relative size of each component of the figure)

For studies of touch, the most prominent sub-type was “massage” (46 studies, 81% of touch studies),42,72-75,77-79,81,82,84-92,95-101,105-110,113,115,116,118-124,126,127,130,131 followed by “skin-to-skin” (also known as “kangaroo care”) (5 studies, 9%),76,80,93,103,104 “warm affective touch/holding” (5 studies, 9%)83,102,111,112,114 and “Reiki touch” (1 study, 2%).117

In the “skin-to-skin” care studies most involved pre-term infants,80,93,103,104 with only one study involving full-term infants;76 all with the mother providing the contact. The studies of “warm affective touch/ holding” included mother and infant dyads83,102 or couples in a relationship.111,112,114 The “Reiki touch” study involved healthy participants with a trained Reiki practitioner.117 Characteristics of the massage studies are provided in more detail later.

For studies of gaze, one intervention sub-type (“direct and averted”) was represented by two studies,129,132 others sub-types (“direct, averted and closed” and “still face”)125,133 were investigated in one study each. One study involved mothers and infants.125 The other three studies involved women and men viewing the gaze of either the researcher,129 or of live models.132,133 For the two studies of touch and gaze (combined), the intervention sub-types were “free play”94 and “still face and touch”.128 Both studies involved parents and their children. One study focused on the combined intervention of “touch, gaze, vocalisation and facial expression”, and examined the intervention sub-type of “social interaction”. This study included a variety of participants including couples and parents with children.134

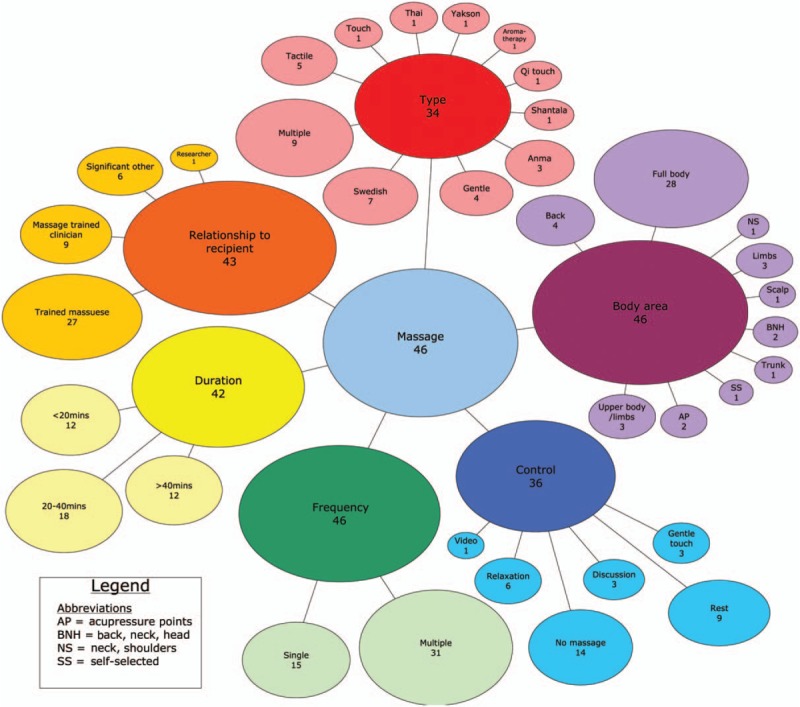

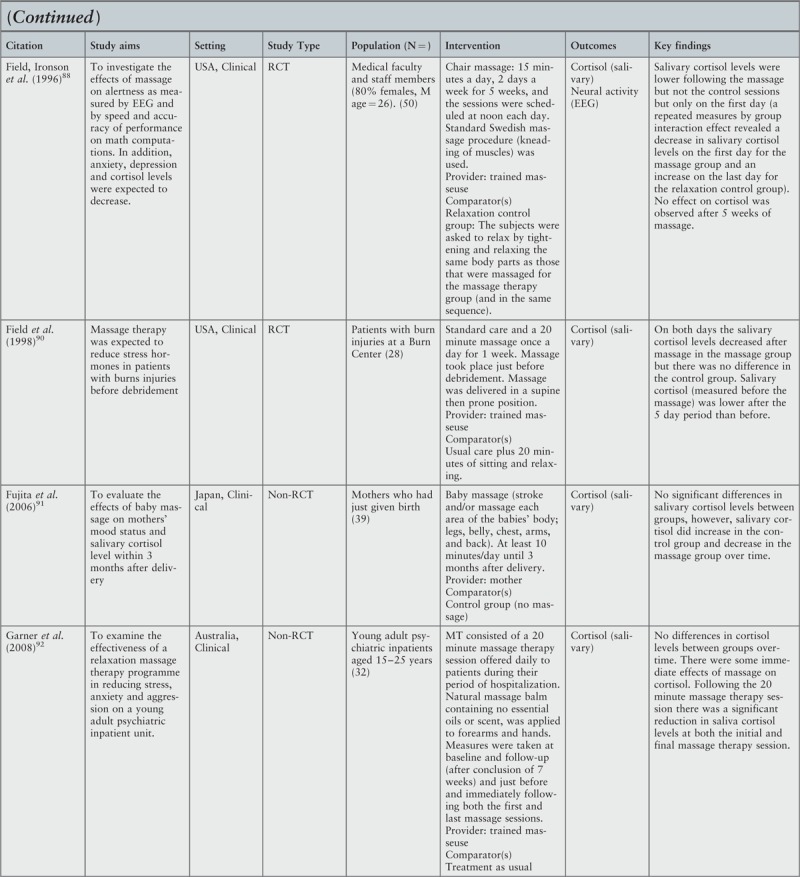

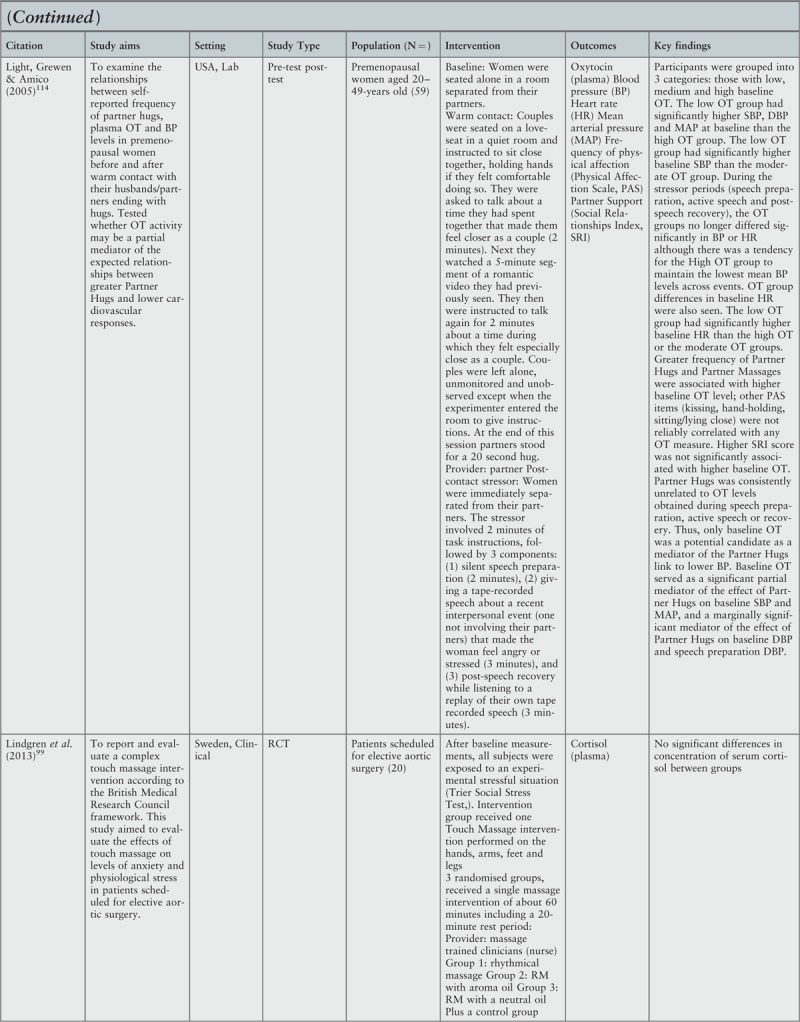

Figure 3 presents a detailed analysis of the key characteristics of “massage”, the most frequently measured intervention sub-type. Many studies failed to provide various details of these characteristics; therefore, the totals for some characteristics in Figure 3 are less than 46.

Figure 3.

Mapping of “massage” intervention study characteristics (values correspond to the number of studies as does the relative size of each component of the figure)

Six aspects of massage apparent from the literature are presented:

-

(i)

Body area: The different amounts/locations of the body being massaged, including: full body (n = 28);42,73-75,78,79,81,82,84-87,90,91,95,97-99,106,108,110,113,116,119,120,124,126,131 back (n = 4);89,115,118,121 back, neck and head (n = 2);101,105 limbs (n = 3);77,92,100 neck and shoulders (n = 1);127 scalp (n = 1);123 trunk (n = 1);96 upper body and limbs (n = 3);72,88,109 acupressure points (n = 2);122,130 and self-selected (n = 1).107

-

(ii)

Type: The style of massage being provided, ranging from gentle/tactile (n = 9),72,75,77,78,98,100,109,110 and Swedish (n = 7),88,90,101,108,115,118,131 to other forms such as anma (n = 3),82,119,120 shantala,81 Thai126 and Yakson.96 Nine studies used multiple types of massage,42,73,74,95,105-107,113,116 and a further 12 did not specify the type of massage used.79,84-87,89,91,92,121,123,127,130

-

(iii)

Relationship to provider (where stated): The provider was either a trained masseuse (n = 27) or researcher/research assistant (n = 1) that had no existing relationship with the recipient;42,75,78,79,81,86-90,92,95,101,106,108,110,113,115,116,118-120,122-124,126,130,131 a trained clinician involved in the subject's care (all nurses: n = 9);72,74,77,96,97,99,100,105,107 or a significant other (a person in a relationship with the receiver) (n = 6).73,84,85,91,109,127

-

(iv)

Duration: The duration of the massage, ranging from less than 20 minutes (n = 12),81,87,88,91,96,98,105,115,121,123,127,130 20–40 minutes (n = 18)72,77,79,82,85,86,89,90,92,95,99,101,107,109,118,120,124 to greater than 40 minutes (n = 12).42,73-75,78,97,100,108,113,116,126,131

-

(v)

Frequency: Whether the massage was conducted once (n = 14)42,72-74,99,100,107,115,118,120,122,126,127,130 or multiple times (n = 31).75,77-79,81,82,84-92,95-98,101,105,106,108-110,113,116,119,123,124,131

-

(vi)

Control: If a control group was used, the most frequently occurring comparator was no massage (n = 14),72,73,84,91,92,95,97,98,105,109,113,123,124,131 followed by rest (n = 9)82,99-101,106,115,118,119,126 and then relaxation (n = 6).79,85,86,88,90,110 A small number of studies used gentle touch (n = 3)42,96,116 and attentive discussion (n = 3).77,78,127 One study used video viewing.89 Due to study design, three studies had no comparator.75,81,121

Outcomes

Figure 2 also presents the outcomes measured for all of the included studies. The most common outcome measure was cortisol accounting for 83% (n = 53) of studies. This included salivary cortisol in 48% (n = 31),42,76-78,80-84,86,88-94,100,104,106,112,113,116,117,119-121,124,126,128 serum cortisol in 28% (n = 18)42,72-75,80,97,99,101,103,105,107,111,116,122-124,131 and urinary cortisol in 17% (n = 11) of studies.79,85-87,89,95,96,98,108,110,113 It should be noted that in a number of studies, two sources of cortisol were sampled. None of the studies with gaze as a sole intervention measured cortisol. Oxytocin was measured in 23% (n = 15) of studies and this was mostly serum oxytocin.42,75,77,94,102,109,111,112,114-116,118,125,127,134 The next most frequent group of outcome measures were the catecholamines: dopamine, epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) in 19% (n = 12) of studies.72,79,85,87,89,95,96,98,110,111,113,123 Serotonin was measured in only 8% (n = 5) of studies.79,85,87,95,101 Neural activity including EEG, amygdala response and N170, a component of event related potential (stimulus in response to viewing faces), were measured in a small number of studies involving gaze129,132 and massage.88,124,130

It should be noted that the inclusion criteria also addressed studies in regard to the neurophysiology of healing, care and the therapeutic relationship. Although many included studies made inferences about the potential for the various neurophysiological measures and we have explored this potential, no studies were identified that directly measured the neurophysiological impact on these concepts. This issue is elaborated in the following discussion.

Discussion

As this is a scoping review, the included studies have not been subjected to critical appraisal. There is therefore no attempt to address the effectiveness of the interventions.

The impetus for this review was the growing body of work on the neurophysiological impact of touch and eye gaze during direct human interaction and the benefits of a positive, trusting therapeutic relationship as the central element in the delivery of high-quality, person-centered fundamental care.11,135 This review, therefore, aimed to identify research that evaluated neurophysiological measures as a response to touch and gaze, given they are essential elements of establishing and maintaining therapeutic relationships. We considered the nature of the interventions in terms of what intervention was delivered, who administered the intervention and who received it.

Although we identified a large body of research, arguably only a small number of studies measured relevant neurophysiological responses and were contextually specific to what could be described as the development and maintenance of a clinician-patient relationship. These studies involved patients and clinicians (all nurses) in the clinical setting.72,74,77,96,97,99,100,105,107 However, to restrict the review to these studies alone would have prevented exploration of a number of aspects of touch and gaze. For example, the effect of gaze was not addressed in any of the studies involving nurses.

The scoping review methodology allows, even encourages, the exploration of the boundaries of a concept. We would assert that therapeutic relationships are not restricted to a nurse and patient. These relationships can and often do include relatives of patients, with nurses often including them in therapeutic activities. In the case of infants, this would include encouraging mothers to have skin-to-skin contact. We established our boundary at the point where objective measurement of direct human to human touch and gaze occurred. Regarding the types of touch and the inclusion of massage, there is a continuum from light or gentle affective touch to firm even forceful touch of deep tissue massage. There is no natural cut-off point within this range. We recognize that gentle affective touch would occur when a nurse is giving comfort to a patient. At the other end of the spectrum nurses will touch patients more firmly when technical care is provided and it is this boundary which we aimed to explore.

The actions of nurses when caring for patients involve a great deal of touch.136,137 This includes touch that would be intended to comfort (gentle touch) and, as part of an intervention, technical or instrumental touch.138 In considering touch in the context of nursing practice, a bed-bound patient requiring washing by a nurse might also be provided with gentle massage, which would closely approximate some studies in the current review where a back massage was the intervention. There were a small number of included studies involving holding; warm, affective touch; and skin-to-skin contact, and once again these studies would contextually relate to the use of touch by nurses to comfort a patient.76,80,83,93,102-104,111,112,114 Other aspects related to touch that were reflected in the studies included the skill level of the masseur/therapeutic provider and the relationship they had to the person receiving touch.

Trust is considered foundational in any therapeutic relationship.23,135 A trusting relationship is considered to be “dynamic and ongoing”,23(p506) suggesting that those who form this relationship are known to each other and have multiple interactions. The majority of studies had massage provided by a trained masseuse, with the next largest group massaged by a significant other, most often a spouse or life partner, and half as many again from a trained clinician. Whilst only four studies reported clinicians providing touch on more than three occasions,77,96,97,105 the trust engendered by an ongoing relationship with a nurse or other type of clinician during therapy (either in a hospital or undergoing regular treatment) might offer potential benefits in regard to the therapeutic relationship and patient recovery/healing.

In the present review, the decision was made to only include studies with “live” gaze, and not the presentation of photos or videos, due to the body of evidence indicating a difference in the neurophysiological reaction to “live” gaze as opposed to gaze that is intermediated by technology (i.e. interaction over a screen, images of faces).132,133 As a result, only seven studies addressing gaze (with or without touch) were included.94,125,128,129,132,134 These studies measured both the effect of direct and averted gaze. This is relevant for the nurse-patient relationship as a more intense physiological response from the stimulus of direct gaze might result in a greater level of cognitive social network engagement which could lead to interpersonal neural synchronization and an increase in empathy.133 It might also result in an increase in neuro-chemicals that strengthen the endocrine system and modulate the stress response. However, no studies that involved gaze between a patient and nurse were identified in the search.

The majority of included studies measured a single intervention, either touch or gaze. In the studies that involved touch, it is reasonable to assume that those providing touch might be making eye contact with the subjects; however, only a small number of studies noted the potential for, or effect of, direct eye gaze as a mediating factor on results. This appears to be due to the lack of awareness of the potential neurophysiological impact of direct eye gaze and therefore, the lack of recognition of its role in moderating or mediating outcomes. Only three studies explicitly involved interventions of both touch and gaze.94,128,134 Notably one recent study included an intervention involving the synchrony codes of touch, gaze, vocalization and facial expression, and its “pragmatic” design meant it was one of the few studies to attempt to control for the reality of the complexity of human-to-human interaction.134

A number of different population groups received interventions. Approximately half of the studies involved the intervention being administered to patients with a variety of medical conditions; the largest group being people with cancer.77-79,95,101,106,107 Many studies aimed to use touch to reduce anxiety and stress, which is common in patient population groups. A few of the studies focusing on healthy individuals used a range of mechanisms to induce stress in the subjects before or after the intervention process, which included touch, gaze and proximity to a trusted or significant other.99,114,127 A number of these studies reported results that can potentially inform how to mediate stress via the therapeutic relationship.

The environment in which the intervention was provided was also a consideration in a number of the studies. Approximately half of the studies were undertaken in a non-clinical environment where conditions could be well-controlled in terms of stimuli not directly related to the human-to-human interaction, such as light and noise. Although the studies undertaken in a clinical setting might be considered more relevant, there was no direct attempt to control for such environmental stimuli.

For the majority of studies (n = 53), the major impact marker tested was cortisol,42,72-101,103-108,110-113,116,117,119-124,126-128,131 with 15 studies measuring oxytocin.42,75,77,94,102,109,111,112,114-116,118,125,127,134 Cortisol levels were measured in serum, saliva and/or urine. In the nine studies that involved patients with nurses providing (gentle) touch, cortisol levels were measured as an indicator of stress.72,74,77,96,97,99,100,105,107 In many cases, the purpose of touch therapy was to reduce stress in patients, and in some it was to explore beneficial neurophysiological effects (including immunological), particularly when the patient was undergoing treatment. Direct eye gaze was also indicated as a de-stressor in the studies that examined at it as an intervention.94,125,128,129,132-134 This highlights the potential for touch and eye gaze, as part of the nurse-patient relationship, to positively impact patients, as supported by findings showing an integrative role of the oxytocinergic system in supporting social affiliation, and an associated rise in immune biomarkers.134

Cortisol was shown to be a complex indicator, as a number of variables are involved, including relationship, gender, age, baseline/resting level, type of touch, type of cortisol (salivary, plasma and urinary) and collection method. For example, massage involving firm pressure (such as Swedish massage) was reported to increase cortisol (due to pressure sensors in the skin); yet, it had other beneficial physiological impacts such as stimulation of oxytocin and immune system function. In many of the studies that had oxytocin as an outcome measure, it was used as an indicator of bonding and/or synchrony. Though not part of this review's objectives, there was a consistent link reported between raised oxytocin and an increase in immunological activity, and this warrants further research in terms of the potentially beneficial outcomes from direct interaction with the clinician. It also raises the potential of using oxytocin as a measure of the development of a therapeutic relationship; however, in the studies with nurses, only one measured oxytocin levels and the rationale was that it was an anxiolytic.77

A small number of studies measured neurological changes including amygdala and other neural activity, changes in nervous system activity and vagal tone, and the presence of various neurochemicals/transmitters in response to study interventions.128-130,132,133 The reported results were consistent with the body of research work regarding the beneficial neurophysiological effects of direct human interaction.30-41

Nursing interventions are often complex with many confounders. Qualitative research investigating touch as part of nurse-patient interaction reports that gentle touch can result in comfort or distress depending on a range of contextual issues, such as the gender of the nurse, the environment in which the touch is administered, and the simple but important act of explaining what is happening before the touch is administered.136,138 Looking for objective evidence about the impact of a good therapeutic relationship is challenging, confounded by the iterative and synergistic neurophysiological nature of direct interaction on both parties.99 The majority of studies that we identified aimed to measure the impact of a single intervention, most commonly massage, often ignoring the additional moderation/mediation of direct eye gaze. The interventions were rarely within the context of the nurse-patient relationship.

Limitations

One potential limitation of this review is that we focused specifically on touch and gaze as central elements of human interaction, including as part of a therapeutic relationship, in studies that quantifiably measured neurophysiological outcomes of such interaction. Human interaction is much more complex than touch and gaze, as shown in those studies that included related aspects such as social synchrony, convergence of biomarkers during bonding and affiliation, and the interplay of such things as allostasis and trust. There are also many studies that explore the neurophysiological impact of other aspects of human interaction, either inclusive or exclusive of touch and gaze, using qualitative methodologies. Such studies, when robust, should also inform this area of research as the complex interplay cannot be measured by quantitative measures alone.

Regarding gaze, the decision was made to only include “live” faces and this restricted the literature we accessed. A further limitation is that, due to the complexity of cultural differences in regard to direct gaze and touch, this review has not included cultural difference as a criterion. This was compounded by only including English language studies. Future research in this area would be valuable in terms of informing nurses and other clinicians on the complex mediating effects.

Finally, it should be noted that we did not search for unpublished literature. In preparation for this review we deemed a comprehensive search for unpublished papers impractical. As this is a scoping review without critical appraisal we make no specific judgments of effect which would be an issue in relation to publication bias.

Conclusion

The aim of this review was to identify studies that evaluated two important elements of human interaction, touch and gaze, and their impact on a range of neurophysiological measures. An important consideration was the relevance of the studies in regard to the nurse-patient relationship, interpreted through the wider lens of the therapeutic relationship. Although small in number, there were studies that did involve nurses and patients, but most did not address the complexity of human interaction as would be seen in the clinical setting. However, there was sufficient consistency in trends evident across many studies regarding the beneficial impact of touch and eye gaze to warrant investigation in the clinical setting. There is a balance here between studies that are tightly controlled and those of a more pragmatic nature that are contextually closer to the reality of providing nursing care. The latter should be encouraged.

Recommendations for research

Given the growing evidence that fundamental care is being poorly executed globally,2-10 there is increasing emphasis on understanding how such care can be delivered effectively and safely and on elucidating the positive impact for patients when such care is delivered well. Fundamental care involves multiple opportunities for touch (as part of routine activities, such as bathing, or intended to comfort) and gaze, and is positively influenced by a trusting nurse-patient relationship. Systematic reviews of effectiveness could help to elucidate the specific neurophysiological mechanisms though which nurses’ routine work and fundamental care result in positive care experiences for patients and improved patient healing. These reviews would range from those considering the neurophysiological effect of massage as a standalone intervention, likely to include a large number of studies, to a review on the effectiveness of comforting touch by nurses, likely to include only a small number of studies. There is also potential for reviews in a number of other areas including neural engagement and synchronization and immunological change.

In regard to primary research, most of the included studies were designed to control for a single stimulus. Very few studies were conducted in the clinical setting with the multiple stimuli that would represent the reality and complexity of nurse-patient interaction. However, these studies demonstrated the feasibility of this type of pragmatic research. Studies in which nurses are the providers of the intervention should be undertaken in the clinical area, to further explore the impact of the relationship between patient and nurse, and it would be relevant to further explore such an impact on both parties, as informed by studies regarding the reciprocal nature of the neurophysiological impacts of direct human interaction. The study by Ulmer-Yaniv et al.134 provides a methodological example of quantifying multiple convergent elements and outcomes of human interaction. Other studies have also used video and accompanying software to code interactions between individuals in both the clinical and simulated environments, also demonstrating feasibility of this approach.139,140 In the early 1990 s, Estabrooks and Morse used a grounded theory approach to investigate how intensive care nurses learn to touch.136 This raises the potential of using both neurophysiological measures and technological intermediation and/or imaging as interventions or aids to teach nurses how to use touch and gaze in order to develop therapeutic relationships.

This review has research implications for the positive use of massage, and for differentiating the type of massage dependent on the required therapeutic outcome desired, as well as controlling for duration, timing, frequency, expertise, relationship and amount of body.

A research area that is currently under-developed is the inclusion of direct eye gaze as a contributing variable in both research studies and practice. Whilst there were only a small number of studies directly related to the role of eye gaze, in a therapeutic context there was evidence that the opportunity for, and effect of, eye gaze is also a potential mediator for a positive interactive outcome, and may have an additive effect when touching is also involved.

The increase in technology in health care requires decisions to be made about the level of human or technological intervention in the care of patients. However, there is currently very little research evidence to guide these choices to maximize benefits to patients, clinicians and the medical institution involved. Recognizing the therapeutic impact of touch and gaze may redefine the way nurses choose to interact with their patients and the future delivery of health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Micah Peters (Joanna Briggs Institute) who provided guidance on the conduct of scoping reviews.

Appendix I: Search strategies

All searches conducted in February 2017

Appendix II: Excluded studies based on eligibility criteria

Busch M, Visser A, Eybrechts M, van Komen R, Oen I, Olff M, et al. The implementation and evaluation of therapeutic touch in burn patients: an instructive experience of conducting a scientific study within a non-academic nursing setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(3):439–46.

Reason for exclusion: No skin-to-skin contact

Chatel-Goldman J, Congedo M, Jutten C, Schwartz JL. Touch increases autonomic coupling between romantic partners. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:95.

Reason for exclusion: No reporting of neurophysiological measures

Currin J, Meister EA. A hospital-based intervention using massage to reduce distress among oncology patients. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(3):214–21.

Reason for exclusion: No reporting of neurophysiological measures

Gordon I, Voos AC, Bennett RH, Bolling DZ, Pelphrey KA, Kaiser MD. Brain mechanisms for processing affective touch. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34(4):914–22.

Reason for exclusion: No skin-to-skin contact

Groer M, Mozingo J, Droppleman P, Davis M, Jolly ML, Boynton M, et al. Measures of salivary secretory immunoglobulin A and state anxiety after a nursing back rub. Appl Nurs Res. 1994;7(1):2–6.

Reason for exclusion: No reporting of neurophysiological measures

Helminen TM, Kaasinen SM, Hietanen JK. Eye contact and arousal: the effects of stimulus duration. Biol Psychol. 2011;88(1):124–30.

Reason for exclusion: Only measured skin conductance response

Henricson M, Berglund AL, Maatta S, Ekman R, Segesten K. The outcome of tactile touch on oxytocin in intensive care patients: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(19):2624–33.

Reason for exclusion: Patients semi-conscious or unconscious

Hodgson NA, Lafferty D. Reflexology versus Swedish Massage to Reduce Physiologic Stress and Pain and Improve Mood in Nursing Home Residents with Cancer: A Pilot Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:Article ID:456897.

Reason for exclusion: Some participants not capable of providing consent so surrogate was used

Kanitz JL, Reif M, Rihs C, Krause I, Seifert G. A randomised, controlled, single-blinded study on the impact of a single rhythmical massage (anthroposophic medicine) on well-being and salivary cortisol in healthy adults. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23(5):685–92.

Reason for exclusion: No detailed reporting of salivary cortisol

Kujala MV, Carlson S, Hari R. Engagement of amygdala in third-person view of face-to-face interaction. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33(8):1753–62.

Reason for exclusion: Subject not directly involved in interaction but observing others

Lee MS, Rim YH, Kang CW. Effects of external qi-therapy on emotions, electroencephalograms, and plasma cortisol. Int J Neurosci. 2004;114(11):1493–502.

Reason for exclusion: No skin-to-skin contact

Lee YH, Park BN, Kim SH. The effects of heat and massage application on autonomic nervous system. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52(6):982–9.

Reason for exclusion: No skin-to-skin contact

Listing M, Krohn M, Kim I, Reisshauer A, Peters E, Liezmann C, et al. The Influence of Classical Massage Therapy on Stress Perception, Mood Disturbances, Body Image, Cortisol and Oxytocin Levels 2011. 389- p.

Reason for exclusion: Conference paper unable to access full-text

Okvat HA, Oz MC, Ting W, Namerow PB. Massage therapy for patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. Altern Ther Health Med. 2002;8(3):68–70, 2, 4–5.

Reason for exclusion: Cortisol only raised in discussion

Peled-Avron L, Wagner S, Perry A, Shamay-Tsoory S. Get in touch: the role of oxytocin in social touch2013. S90-S p.

Reason for exclusion: Conference paper unable to access full-text

Pierno AC, Becchio C, Turella L, Tubaldi F, Castiello U. Observing social interactions: the effect of gaze. Soc Neurosci. 2008;3(1):51–9.

Reason for exclusion: Not live faces

Ponkanen LM, Hietanen JK, Peltola MJ, Kauppinen PK, Haapalainen A, Leppanen JM. Facing a real person: an event-related potential study. Neuroreport. 2008;19(4):497–501.

Reason for exclusion: Unable to access full-text

Rapaport M, L. Hale K, Koury M, Shubov A, J. Bresee C. The role of oxytoncin, vasopressin and cortisol in the beneficial effects of massage therapy 2008. 1S-S p.

Reason for exclusion: Conference paper unable to access full-text

Sato W, Kochiyama T, Uono S, Toichi M. Neural mechanisms underlying conscious and unconscious attentional shifts triggered by eye gaze. Neuroimage. 2016;124(Pt A):118–26.

Reason for exclusion: Not live faces

Sato W, Kochiyama T, Uono S, Yoshikawa S. Amygdala integrates emotional expression and gaze direction in response to dynamic facial expressions. Neuroimage. 2010;50(4):1658–65.

Reason for exclusion: Not live faces

Sato W, Yoshikawa S, Kochiyama T, Matsumura M. The amygdala processes the emotional significance of facial expressions: an fMRI investigation using the interaction between expression and face direction. Neuroimage. 2004;22(2):1006–13.

Reason for exclusion: Not live faces

Sauer A, Mothes-Lasch M, Miltner WH, Straube T. Effects of gaze direction, head orientation and valence of facial expression on amygdala activity. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9(8):1246–52.

Reason for exclusion: Not live faces

Appendix III: Characteristics of included studies

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Author RW is an associate editor of the JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports.

References

- 1.Kitson A, Conroy T, Kuluski K, Locock L, Lyons R. Reclaiming and redefining the fundamentals of care: nursing's response to meeting patients’ basic human needs. Adelaide, South Australia: School of Nursing, The University of Adelaide; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bureau of Health Information. Adult Admitted Patient Survey 2013 Results. Snapshot Report NSW Patient Survey Program. NSW: BHI, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Care Quality Commission. The state of health care and adult social care in England. An overview of key themes 2010/11. UK: The Stationery Office Limited on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust public inquiry. London: Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office; Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garling P. Final report of the Special Commission of Inquiry Acute Care Services in NSW Public Hospitals. Sydney, Australia: Special Commission of Inquiry: Acute Care Services in New South Wales Public Hospitals; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill A, Kuluski K, Jaakkimainen L, Naganathan G, Upshur R, Wodchis WP. Where do we go from here?” Health system frustrations expressed by patients with multimorbidity, their caregivers and family physicians. Healthc Policy 2014; 9 4:73–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalisch BJ. Missed nursing care: a qualitative study. J Nurs Care Qual 2006; 21 4:306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalisch BJ, Landstrom G, Williams RA. Missed nursing care: errors of omission. Nurs Outlook 2009; 57 1:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalisch BJ, Tschannen D, Lee H, Friese CR. Hospital variation in missed nursing care. Am J Med Qual 2011; 26 4:291–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SA Health. Measuring Consumer Experience. SA Public Hospital Inpatient Annual Report, March 2012. Adelaide, SA: Safety and Quality; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitson AL, Muntlin Athlin A, Conroy T. Anything but basic: Nursing's challenge in meeting patients’ fundamental care needs. J Nurs Scholarsh 2014; 46 5:331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folkman S. Carr BI, Steel J. Stress,Coping,and Hope. Psychological Aspects of Cancer. US: Springer; 2013. 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groopman J. The anatomy of hope: How people prevail in the face of illness. New York: Random House; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woolley J, Perkins R, Laird P, Palmer J, Schitter MB, Tarter K, et al. Relationship-based care: implementing a caring, healing environment. Medsurg Nurs 2012; 21 3:179–182. 84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miner-Williams D. Connectedness in the nurse-patient relationship: a grounded theory study. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2007; 28 11:1215–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Detillion CE, Craft TK, Glasper ER, Prendergast BJ, DeVries AC. Social facilitation of wound healing. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004; 29 8:1004–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeVries AC, Craft TK, Glasper ER, Neigh GN, Alexander JK. 2006 Curt P. Richter award winner: Social influences on stress responses and health. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2007; 32 6:587–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roe CA, Sonnex C, Roxburgh EC. Two meta-analyses of noncontact healing studies. Explore (NY) 2015; 11 1:11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallace A, Spence C. The science of interpersonal touch: an overview. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2010; 34 2:246–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papathanassoglou ED, Mpouzika MD. Interpersonal touch: physiological effects in critical care. Biol Res Nurs 2012; 14 4:431–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monzillo E, Gronowicz G. New insights on therapeutic touch: a discussion of experimental methodology and design that resulted in significant effects on normal human cells and osteosarcoma. Explore (NY) 2011; 7 1:44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold E, Boggs K. Interpersonal Relationships Professional Communication Skills for Nurses. London: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dinc L, Gastmans C. Trust in nurse-patient relationships: a literature review. Nurs Ethics 2013; 20 5:501–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster T, Hawkins J. The therapeutic relationship: dead or merely impeded by technology? Br J Nurs 2005; 14 13:698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turley J. Ball M, Hannah K, Newbold S, Douglas J. Nursing's Future: Ubiquitous Computing, Virtual Reality, and Augmented Reality. Nursing informatics: Where technology and caring meet. 2nd Ed ed. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media; 1995. 320–330. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Georgiou E, Papathanassoglou E, Pavlakis A. Nurse-physician collaboration and associations with perceived autonomy in Cypriot critical care nurses. Nurs Crit Care 2015; 22 1:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vouzavali FJ, Papathanassoglou ED, Karanikola MN, Koutroubas A, Patiraki EI, Papadatou D. ’The patient is my space’: hermeneutic investigation of the nurse-patient relationship in critical care. Nurs Crit Care 2011; 16 3:140–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Field T. Touch for socioemotional and physical well-being: A review. Dev Rev 2010; 30 4:367–383. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linden D. Touch: The Science of Hand, Heart, and Mind. New York: Penguin; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guest S, Dessirier JM, Mehrabyan A, McGlone F, Essick G, Gescheider G, et al. The development and validation of sensory and emotional scales of touch perception. Atten Percept Psychophys 2011; 73 2:531–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hertenstein MJ, Holmes R, McCullough M, Keltner D. The communication of emotion via touch. Emotion 2009; 9 4:566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hertenstein MJ, Weiss SJ. The handbook of touch: Neuroscience, behavioral, and applied perspectives. New York: Springer Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerr CE, Wasserman RH, Moore CI. Cortical dynamics as a therapeutic mechanism for touch healing. J Altern Complement Med 2007; 13 1:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGlone F, Wessberg J, Olausson H. Discriminative and Affective Touch: Sensing and Feeling. Neuron 2014; 82 4:737–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ackerley R, Backlund Wasling H, Liljencrantz J, Olausson H, Johnson RD, Wessberg J. Human C-tactile afferents are tuned to the temperature of a skin-stroking caress. J Neurosci 2014; 34 8:2879–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjornsdotter M, Loken L, Olausson H, Vallbo A, Wessberg J. Somatotopic organization of gentle touch processing in the posterior insular cortex. J Neurosci 2009; 29 29:9314–9320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loken LS, Wessberg J, Morrison I, McGlone F, Olausson H. Coding of pleasant touch by unmyelinated afferents in humans. Nat Neurosci 2009; 12 5:547–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrison I, Bjornsdotter M, Olausson H. Vicarious responses to social touch in posterior insular cortex are tuned to pleasant caressing speeds. J Neurosci 2011; 31 26:9554–9562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diego MA, Field T. Moderate pressure massage elicits a parasympathetic nervous system response. Int J Neurosci 2009; 119 5:630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. Int J Neurosci 2005; 115 10:1397–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kutner JS, Smith MC, Corbin L, Hemphill L, Benton K, Mellis BK, et al. Massage therapy versus simple touch to improve pain and mood in patients with advanced cancer: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149 6:369–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rapaport MH, Schettler P, Bresee C. A preliminary study of the effects of a single session of Swedish massage on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and immune function in normal individuals. J Altern Complement Med 2010; 16 10:1079–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmerman A, Bai L, Ginty DD. The gentle touch receptors of mammalian skin. Science 2014; 346 6212:950–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sandkuhler J, Gruber-Schoffnegger D. Hyperalgesia by synaptic long-term potentiation (LTP): an update. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2012; 12 1:18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goleman D. Social intelligence: The new science of social relationships. New York: Bantum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elfenbein HA. Druskat VU, Sala F, Mount G. Team Emotional Intelligence: What It Can Mean and How It Can Affect Performance. Linking emotional intelligence and performance at work: Current research evidence with individuals and groups. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2006. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kerr F. Creating and leading adaptive organisations: the nature and practice of emergent logic [Research Thesis]. Adelaide: University of Adelaide; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizzolatti G, Sinigaglia C. The functional role of the parieto-frontal mirror circuit: interpretations and misinterpretations. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010; 11 4:264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gouin JP, Carter CS, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Glaser R, Malarkey WB, Loving TJ, et al. Marital behavior, oxytocin, vasopressin, and wound healing. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010; 35 7:1082–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guastella AJ, Mitchell PB, Dadds MR. Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 63 1:3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uvnas-Moberg K, Petersson M. [Oxytocin, a mediator of anti-stress, well-being, social interaction, growth and healing]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother 2005; 51 1:57–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boyatzis R. An overview of intentional change from a complexity perspective. Journal of Management Development 2006; 25 7:607–623. [Google Scholar]

- 53.WW Norton & Company, Erikson E, Erikson J. The life cycle completed (extended version). 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davidson RJ, Sutton SK. Affective neuroscience: the emergence of a discipline. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1995; 5 2:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Damasio A. Human behaviour: brain trust. Nature 2005; 435 7042:571–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Babar S, Khare GD, Vaswani RS, Irsch K, Mattheu JS, Walsh L, et al. Eye dominance and the mechanisms of eye contact. J AAPOS 2010; 14 1:52–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schore AN. The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). W W Norton; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lux M. The Magic of Encounter: The Person-Centered Approach and the Neurosciences. Person-Centered Exp Psychother 2010; 9 4:274–289. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Senju A, Csibra G, Johnson MH. Understanding the referential nature of looking: infants’ preference for object-directed gaze. Cognition 2008; 108 2:303–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lawn JE, Mwansa-Kambafwile J, Horta BL, Barros FC, Cousens S. ’Kangaroo mother care’ to prevent neonatal deaths due to preterm birth complications. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39 Suppl 1:i144–i154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall, Echterling LG, Presbury JH, McKee JE. Crisis Intervention: Promoting Resilience and Resolution in Troubled Times. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Presbury J, Echterling L, McKee J. Beyond Brief Counseling and Therapy: An Integrative Approach. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wager TD, Atlas LY. The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat Rev Neurosci 2015; 16 7:403–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Furlan AD, Giraldo M, Baskwill A, Irvin E, Imamura M. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet] 2015. 9.Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001929. [Accessed 13 November 2015]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Q, Sun Z, Yue J. Massage therapy for preventing pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet] 2015. 6.Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010518. [Accessed 13 November 2015]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bennett C, Underdown A, Barlow J. Massage for promoting mental and physical health in typically developing infants under the age of six months. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 4:CD005038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nelson NL. Massage therapy: understanding the mechanisms of action on blood pressure. A scoping review. J Am Soc Hypertens 2015; 9 10:785–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kerr F, Wiechula R, Feo R, Schultz T, Kitson A. The neurophysiology of human touch and eye gaze and its effects on therapeutic relationships and healing: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep 2016; 14 4:60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peters MC, Godfrey P, McInerney C, Baldini Soares H, Khalil DP. Aromataris E. Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute, The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015. Adelaide: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015; 13 3:141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6 7:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Acolet D, Modi N, Giannakoulopoulos X, Bond C, Weg W, Clow A, et al. Changes in plasma cortisol and catecholamine concentrations in response to massage in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child 1993; 68 (1 SecNo):29–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Adib-Hajbaghery M, Rajabi-Beheshtabad R, Abasi A. Effect of Whole Body Massage by Patient's Companion on the Level of Blood Cortisol in Coronary Patients. Nurs Midwifery Stud 2013; 2 3:10–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adib-Hajbaghery M, Rajabi-Beheshtabad R, Ardjmand A. Comparing the effect of whole body massage by a specialist nurse and patients’ relatives on blood cortisol level in coronary patients. ARYA Atheroscler 2015; 11 2:126–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Andersson K, Wändell P, Törnkvist L. Tactile massage improves glycaemic control in women with type 2 diabetes: A pilot study. Pract Diabetes Int 2004; 21 3:105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bigelow A, Power M, MacLellan-Peters J, Alex M, McDonald C. Effect of mother/infant skin-to-skin contact on postpartum depressive symptoms and maternal physiological stress. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2012; 41 3:369–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Billhult A, Lindholm C, Gunnarsson R, Stener-Victorin E. The effect of massage on cellular immunity, endocrine and psychological factors in women with breast cancer -- a randomized controlled clinical trial. Auton Neurosci 2008; 140 (1–2):88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Billhult A, Lindholm C, Gunnarsson R, Stener-Victorin E. The effect of massage on immune function and stress in women with breast cancer--a randomized controlled trial. Auton Neurosci 2009; 150 (1–2):111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boylan M. Massage boosts immunity in breast cancer patients. J Aust Tradit-Med So 2005; 11 2:59–95. 5p. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cong X, Ludington-Hoe SM, Walsh S. Randomized crossover trial of kangaroo care to reduce biobehavioral pain responses in preterm infants: a pilot study. Biol Res Nurs 2011; 13 2:204–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Cássia Fogaça M, Carvalho WB, de Araújo Peres C, Lora MI, Hayashi LF, do Nascimento Verreschi IT. Salivary cortisol as an indicator of adrenocortical function in healthy infants, using massage therapy. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123 5:215–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Donoyama N, Shoji S, Munakata T. Effect of traditional Japanese massage, Anma therapy on body and mind: a preliminary study. J Jpn Soc Balneol Climatol Phys Med 2005; 68 4:241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Elverson CA, Wilson ME, Hertzog MA, French JA. Social Regulation of the Stress Response in the Transitional Newborn: A Pilot Study. J Pediatr Nurs 2012; 27 3:214–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, Deeds O, Figueiredo B. Pregnancy massage reduces prematurity, low birthweight and postpartum depression. Infant Behav Dev 2009; 32 4:454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Massage therapy effects on depressed pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2004; 25 2:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Field T, Grizzle N. Massage and relaxation therapies’ effects on depressed adolescent mothers. Adolescence 1996; 31 124:903–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Field T, Grizzle N, Scafidi F, Abrams S, Richardson S, Kuhn C, et al. Massage therapy for infants of depressed mothers. Infant Behav Dev 1996; 19 1:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Field T, Ironson G, Scafidi F, Nawrocki T. Massage therapy reduces anxiety and enhances EEG pattern of alertness and math computations. Int J Neurosci 1996; 86 (3–4):197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Field T, Morrow C, Valdeon C, Larson S, Kuhn C, Schanberg S. Massage reduces anxiety in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992; 31 1:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Field T, Peck M, Krugman S, Tuchel T, Schanberg S, Kuhn C, et al. Burn injuries benefit from massage therapy. J Burn Care Rehabil 1998; 19 3:241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fujita M, Endoh Y, Saimon N, Yamaguchi S. Effect of massaging babies on mothers: pilot study on the changes in mood states and salivary cortisol level. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2006; 12 3:181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Garner B, Phillips LJ, Schmidt HM, Markulev C, O’Connor J, Wood SJ, et al. Pilot study evaluating the effect of massage therapy on stress, anxiety and aggression in a young adult psychiatric inpatient unit. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2008; 42 5:414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gitau R, Modi N, Gianakoulopoulos X, Bond C, Glover V, Stevenson J. Acute effects of maternal skin-to-skin contact and massage on saliva cortisol in preterm babies. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2002; 20 2:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gordon I, Zagoory-Sharon O, Leckman JF, Feldman R. Oxytocin, cortisol, and triadic family interactions. Physiol Behav 2010; 101 5:679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hernandez-Reif M, Ironson G, Field T, Hurley J, Katz G, Diego M, et al. Breast cancer patients have improved immune and neuroendocrine functions following massage therapy. J Psychosom Res 2004; 57 1:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Im H, Kim E. Effect of Yakson and Gentle Human Touch versus usual care on urine stress hormones and behaviors in preterm infants: A quasi-experimental study. Int J Nurs Stud 2009; 46 4:450–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kramer M, Chamorro I, Green D, Knudtson F. Extra tactile stimulation of the premature infant. Nurs Res 1975; 25 5:324–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kuhn CM, Schanberg SM, Field T, Symanski R, Zimmerman E, Scafidi F, et al. Tactile-kinesthetic stimulation effects on sympathetic and adrenocortical function in preterm infants. J Pediatr 1991; 119 3:434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lindgren L, Lehtipalo S, Winso O, Karlsson M, Wiklund U, Brulin C. Touch massage: a pilot study of a complex intervention. Nurs Crit Care 2013; 18 6:269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lindgren L, Rundgren S, Winso O, Lehtipalo S, Wiklund U, Karlsson M, et al. Physiological responses to touch massage in healthy volunteers. Auton Neurosci 2010; 158 (1–2):105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Listing M, Krohn M, Liezmann C, Kim I, Reisshauer A, Peters E, et al. The efficacy of classical massage on stress perception and cortisol following primary treatment of breast cancer. Arch Womens Ment Health 2010; 13 2:165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Matthiesen AS, Ransjo-Arvidson AB, Nissen E, Uvnas-Moberg K. Postpartum maternal oxytocin release by newborns: effects of infant hand massage and sucking. Birth 2001; 28 1:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mooncey S, Giannakoulopoulos X, Glover V, Acolet D, Modi N. The effect of mother-infant skin-to-skin contact on plasma cortisol and beta-endorphin concentrations in preterm newborns. Infant Behav Dev 1997; 20 4:553–557. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Neu M, Laudenslager ML, Robinson J. Coregulation in salivary cortisol during maternal holding of premature infants. Biol Res Nurs 2009; 10 3:226–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pinar R, Afsar F. Back Massage to Decrease State Anxiety, Cortisol Level, Blood Prsessure, Heart Rate and Increase Sleep Quality in Family Caregivers of Patients with Cancer: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015; 16 18:8127–8133. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Post-White J, Fitzgerald M, Savik K, Hooke MC, Hannahan AB, Sencer SF. Massage therapy for children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2009; 26 1:16–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stringer J, Swindell F, Dennis M. Massage in patients undergoing intensive chemotherapy reduces serum cortisol and prolactin. Psycho-Oncology 2008; 17 10:1024–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Taylor AG, Galper DI, Taylor P, Rice LW, Andersen W, Irvin W, et al. Effects of adjunctive Swedish massage and vibration therapy on short-term postoperative outcomes: a randomized, controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med 2003; 9 1:77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tsuji S, Yuhi T, Furuhara K, Ohta S, Shimizu Y, Higashida H. Salivary oxytocin concentrations in seven boys with autism spectrum disorder received massage from their mothers: A pilot study. Front Psychiatry 2015. 6.ArtID 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wandell PE, Carlsson AC, Andersson K, Gafvels C, Tornkvist L. Tactile massage or relaxation exercises do not improve the metabolic control of type 2 diabetics. Open Diabetes J 2010; 3:6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Grewen KM, Girdler SS, Amico J, Light KC. Effects of partner support on resting oxytocin, cortisol, norepinephrine, and blood pressure before and after warm partner contact. Psychosom Med 2005; 67 4:531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Holt-Lunstad J, Birmingham WA, Light KC. Influence of a “warm touch” support enhancement intervention among married couples on ambulatory blood pressure, oxytocin, alpha amylase, and cortisol. Psychosom Med 2008; 70 9:976–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ironson G, Field T, Scafidi F, Hashimoto M, Kumar M, Kumar A, et al. Massage therapy is associated with enhancement of the immune system's cytotoxic capacity. Int J Neurosci 1996; 84 (1–4):205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Light KC, Grewen KM, Amico JA. More frequent partner hugs and higher oxytocin levels are linked to lower blood pressure and heart rate in premenopausal women. Biol Psychol 2005; 69 1:5–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Morhenn V, Beavin LE, Zak PJ. Massage increases oxytocin and reduces adrenocorticotropin hormone in humans. Altern Ther Health Med 2012; 18 6:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rapaport MH, Schettler P, Bresee C. A Preliminary Study of the Effects of Repeated Massage on Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal and Immune Function in Healthy Individuals: A Study of Mechanisms of Action and Dosage. J Altern Complement Med 2012; 18 8:789–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wardell DW, Engebretson J. Biological correlates of REIKI TOUCH healing. J Adv Nurs 2001; 33 4:439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wikstrom S, Gunnarsson T, Nordin C. Tactile stimulus and neurohormonal response: A pilot study. International J Neurosci 2003; 113 6:787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Donoyama N, Munakata T, Shibasaki M. Effects of Anma therapy (traditional Japanese massage) on body and mind. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2010; 14 1:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Donoyama N, Shibasaki M. Differences in practitioners’ proficiency affect the effectiveness of massage therapy on physical and psychological states. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2010; 14 3:239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Noto Y, Kudo M, Hirota K. Back massage therapy promotes psychological relaxation and an increase in salivary chromogranin A release. J Anesth 2010; 24 6:955–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Jung M, Shin BC, Kim YS, Shin YI, Lee M. Is there any difference in the effects of qi therapy (external Qigong) with and without touching? A pilot study. Int J Neurosci 2006; 116 9:1055–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kim IH, Kim TY, Ko YW. The effect of a scalp massage on stress hormone, blood pressure, and heart rate of healthy female. J Phys Ther Sci 2016; 28 10:2703–2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wu JJ, Cui Y, Yang YS, Kang MS, Jung SC, Park HK, et al. Modulatory effects of aromatherapy massage intervention on electroencephalogram, psychological assessments, salivary cortisol and plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2014; 22 3:456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kim S, Fonagy P, Koos O, Dorsett K, Strathearn L. Maternal oxytocin response predicts mother-to-infant gaze. Brain Res 2014; 1580:133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bennett S, Bennett MJ, Chatchawan U, Jenjaiwit P, Pantumethakul R, Kunhasura S, et al. Acute effects of traditional Thai massage on cortisol levels, arterial blood pressure and stress perception in academic stress condition: A single blind randomised controlled trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2016; 20 2:286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ditzen B, Neumann ID, Bodenmann G, von Dawans B, Turner RA, Ehlert U, et al. Effects of different kinds of couple interaction on cortisol and heart rate responses to stress in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2007; 32 5:565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Feldman R, Singer M, Zagoory O. Touch attenuates infants physiological reactivity to stress. Dev Sci 2010; 13 2:271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mormann F, Niediek J, Tudusciuc O, Quesada CM, Coenen VA, Elger CE, et al. Neurons in the human amygdala encode face identity, but not gaze direction. Nat Neurosci 2015; 18 11:1568–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Chang KM, Luo SY, Chen SH, Wang TP, Ching CTS. Body Massage Performance Investigation by Brain Activity Analysis. Evid-Based Compl Alt 2012; 2012:Article ID 252163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]