Abstract

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airway which is often misdiagnosed and undertreated. Early diagnosis and vigilant asthma control are crucial to preventing permanent airway damage, improving quality of life and reducing healthcare burdens. The key approaches to asthma management should include patient empowerment through health education and self-management and, an effective patient-healthcare provider partnership.

Keywords: asthma, acute asthma, stable asthma, written asthma action plan, asthma control

Introduction

Asthma is a common medical condition in adults, with a prevalence of 4.5% in Malaysia, based on the National Health and Morbidity Survey 2006. It is an inflammatory disease of the airway which is triggered by external stimuli in genetically-predisposed individuals, leading to mucus secretion, bronchoconstriction and airway narrowing.

The most common symptom is a chronic cough. Misdiagnoses or underdiagnoses cause persistent airway inflammation, airway remodeling, and subsequently, fixed airway obstruction. Therefore, it is important for healthcare professionals to diagnose and manage asthma confidently.

Risk Factors

Asthma is a multifactorial disease brought about by various familial and environmental influences, as seen in Table 1 below:

Table 1. Risk factors for asthma.

| Genetic factors |

Environmental factors

|

Other risk factors/co-morbidities

|

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of asthma is based on a combination of clinical features suggestive of reversible airway obstruction supported by investigations, as shown in Tables 2 and 3. A response to treatment may support the diagnosis; however, a lack of response does not exclude asthma.

Table 2. Clinical features of asthma.

| Common symptoms |

|

| Symptom variability |

|

| Triggers |

|

| History of atopy |

|

| Family history |

|

| Physical examination |

|

Table 3. Investigations for asthma.

| Investigation | Description |

|---|---|

| Demonstration of airway obstruction | |

| Spirometry |

|

| Demonstration of airway obstruction variability | |

| Bronchodilator reversibility |

|

| Other method |

|

| Peak flow charting |

|

General Principles of Management

The aims of management are to achieve good asthma symptom control and minimise future risk of exacerbations. The partnership between the patients/caregivers and healthcare providers is important in ensuring the success of the management. The patient's preferences for treatment, ability to use an inhaler correctly, side effects and cost of medications should be taken into consideration during the treatment process.

Asthma Self-Management

The patient's active participation is important in asthma management. All patients should be made aware of the components of asthma self-management, which include:

self-monitoring of symptoms and/or PEF

a written asthma action plan (WAAP) for optimisation of asthma control through self- adjustment of medications

a regular medical review by healthcare providers

A home nebuliser should be avoided, as it leads to underestimation of the severity of an acute exacerbation of asthma.

Stable Asthma

Stable asthma is defined as the absence of symptoms, no limitations on activities and not requiring any relievers in the last four weeks.

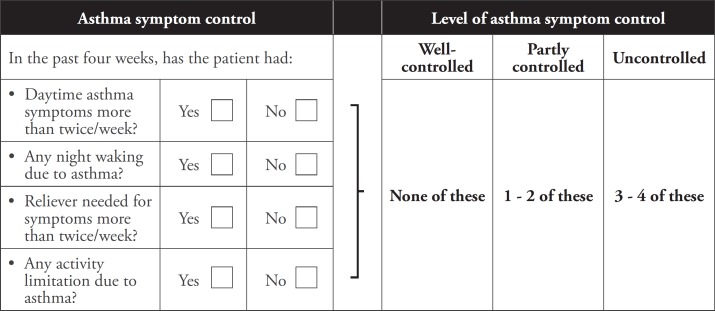

a. Assessment of asthma control

Asthma control can be assessed by using Asthma Control Test (ACT) scores or asking recommended questions, as shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4. Assessment of asthma symptom control.

b. Assessment of the severity of future risks

Assessment of the risk factors for a poor asthma outcome is important in treatment adjustments and prediction of exacerbation. Refer to Table 5 for more details.

Table 5. Investigations for asthma.

| Risk factors for poor asthma outcome | |

| |

| Independent risk factors | Having one or more of these risk factors increases the risk of exacerbations, even if symptoms are well-controlled:

|

| Risk factors for fixed airflow limitation |

|

| Risk factors for medication side effect |

|

c. Treatment

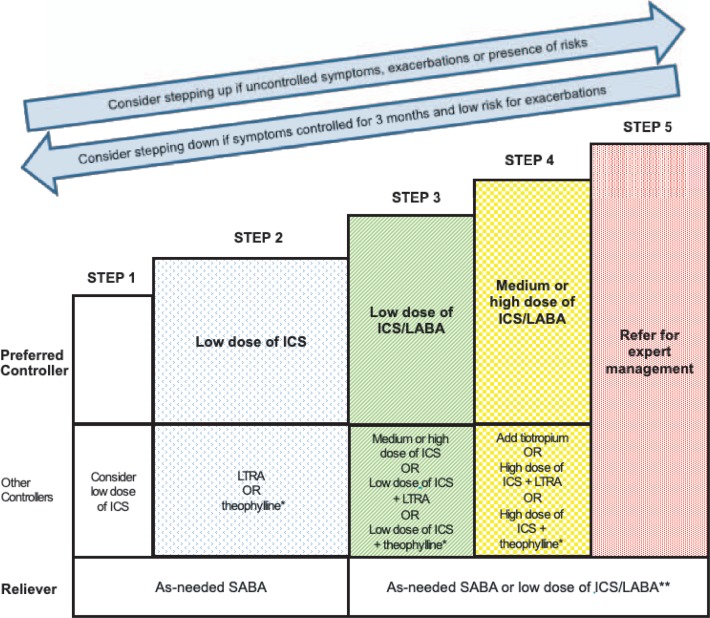

The goal of asthma treatment is to achieve and maintain symptom control. This is done using a stepwise approach, as shown in Figure 1. Any of the following issues should be addressed before considering treatment adjustment:

inhaler technique

adherence to medications

modifiable risk factors

presence of co-morbidities

Figure 1. Stepwise treatment ladder in stable asthma.

- Reliever

- Inhaled SABA are the reliever of choice in stable asthma. Oral SABA should be avoided in asthma due to their side effects.

- A low dose of budesonide/formoterol or beclometasone/formoterol may be used as a single inhalant for maintenance and reliever therapy in moderate to severe asthma.

- Inhaled long-acting β2-agonists without ICS should not be used in reliever monotherapy in stable asthma.

- Controller (in addition to as-needed reliever inhaler)

- ICS are the preferred controller therapy in asthma.

- Initiation of ICS should not be delayed in symptomatic asthma.

- Low-dose ICS should be considered in steroid-naïve, symptomatic asthma.

- Long-acting β2-agonists should not be used as controller monotherapy without ICS in asthma.

- Leukotriene receptor antagonists as add-on can be beneficial in patients with concomitant seasonal allergic rhinitis and asthma.

- The soft-mist inhaler tiotropium may be used as add-on therapy in patients with asthma that is not well-controlled with medium- or high-dose ICS.

- Patients with difficult-to-control asthma should be referred to a respiratory physician.

Non-Pharmacological Treatment

Non-pharmacological treatments may improve symptom control and/or reduce future risk of asthma exacerbation. This includes smoking cessation, vaccination and weight loss management.

Acute Exacerbation of Asthma

Acute exacerbation of asthma is defined as a progressive or sudden onset of worsening symptoms. Status asthmaticus is a life-threatening and medical emergency situation.

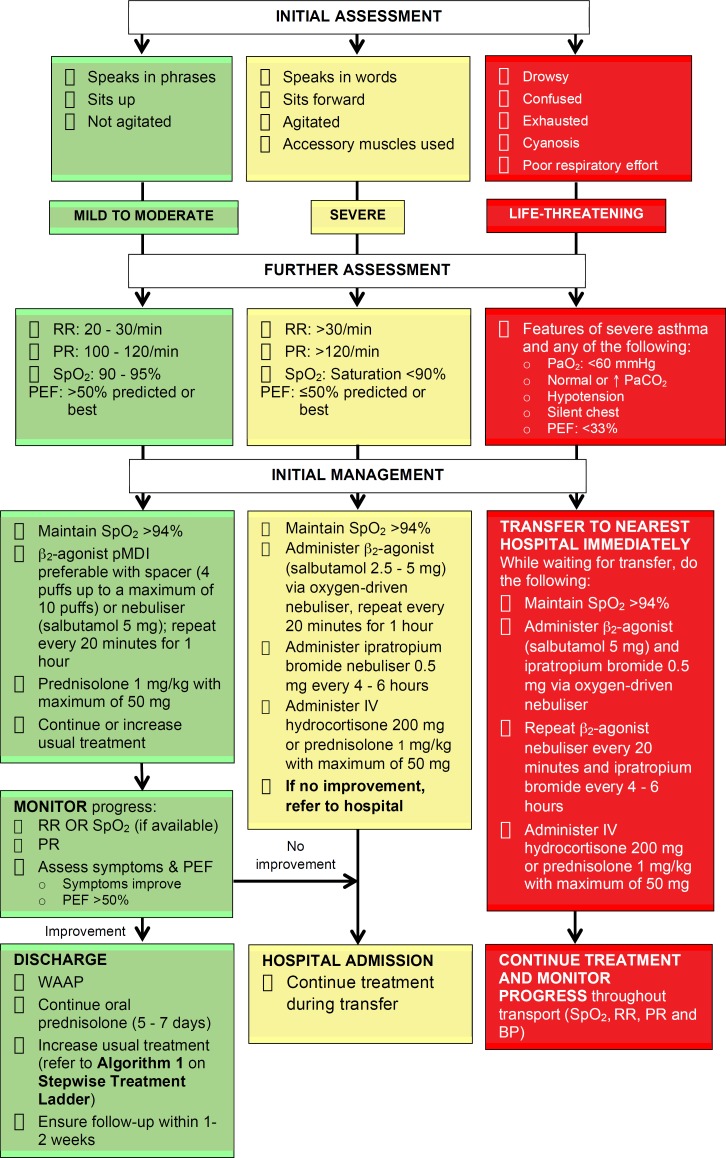

a. Assessment of severity and management

Rapid clinical assessment of severity (refer to Table 6) should be performed in all acute exacerbation of asthma. Treatment should be initiated immediately based on the severity of the asthma (refer to Algorithm 1).

Table 6. Level of severity of acute exacerbation of asthma.

| Severity | Clinical features | Clinical parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Mild to moderate |

|

|

| Severe |

|

|

| Life-threatening | Severe asthma with ANY OF THE FOLLOWING: | |

|

|

|

Algorithm 1. Management of acute asthma in primary care.

In acute exacerbation of asthma, inhaled β2-agonists are the first-line treatment.

In mild to moderate exacerbations, a pressurised metered dose inhaler with a spacer is the preferred method of delivery.

In severe and life-threatening exacerbations, continuous delivery of nebulised oxygen-driven β2-agonists should be used.

Systemic corticosteroids should be given to all patients with acute exacerbation of asthma. They should be continued for 5 to 7 days. Asthma patients prescribed OCS should continue their regular ICS.

b. Criteria for admission/discharge

All patients with severe, life-threatening asthma and those with PEF<75% personal best or predicted one hour after initial treatment should be admitted. The following factors may be considered for admission:

persistent symptoms

pregnancy

previous near-fatal asthma attack

deteriorating PEF

living alone/socially isolated

persisting or worsening hypoxia

psychological problems

exhaustion

physical disability or learning difficulties

drowsiness, confusion or altered conscious state

asthma attack despite recent adequate steroid treatment

respiratory arrest

Patients with resolution of symptoms and PEF >75% personal best or predicted one hour after initial treatment may be discharged home with a WAAP

Referral

A referral to a specialist with experience in asthma should be made for asthma patients with the following conditions:

diagnosis of asthma is not clear

suspected occupational asthma

poor response to asthma treatment

persistent use of high-dose ICS without being able to taper off

symptoms remain uncontrolled with persistent use of high-dose ICS

persistent symptoms despite continuous use of moderate- to high-dose ICS combined with LABA

severe/life-threatening asthma exacerbations

asthma in pregnancy

asthma with multiple co-morbidities

Acknowledgement

Details of the evidence supporting the above statements can be found in the Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Asthma in Adults 2017, available on the following websites: Ministry of Health Malaysia: http://www.moh.gov.my and Academy of Medicine: http://www.acadmed.org.my. Corresponding organisation: CPG Secretariat, Health Technology Assessment Section, Medical Development Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia, contactable at htamalaysia@moh.gov.my