Abstract

Background

Although tourniquets are commonly used during TKA, that practice has long been surrounded by controversy. Quantifying the case for or against tourniquet use in TKA, in terms of patient-reported outcomes such as postoperative pain, is a priority.

Questions/purposes

The purpose of this study was to meta-analyze the available randomized trials on tourniquet use during TKA to determine whether use of a tourniquet during TKA (either for the entire procedure or some portion of it) is associated with (1) increased postoperative pain; (2) decreased ROM; and (3) longer lengths of hospital stay (LOS) compared with TKAs performed without a tourniquet.

Methods

We completed a systematic review and meta-analysis using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines to assess the impact of tourniquet use on patients after TKA. We searched the following databases from inception to February 1, 2015, for randomized controlled trials meeting prespecified inclusion criteria: PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Postoperative pain was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were postoperative ROM and LOS. The initial search yielded 218 studies, of which 14 met the inclusion criteria. For our primary analysis on pain and ROM, a total of eight studies (221 patients in the tourniquet group, 219 patients in the no-tourniquet group) were meta-analyzed. We also performed a subgroup meta-analysis on two studies that used the tourniquet only for a portion of the procedure (from osteotomy until the leg was wrapped with bandages) and defined this as half-course tourniquet use (n = 62 in this analysis). The Jadad scale was used to ascertain methodological quality, which ranged from 3 to 5 with a maximum possible score of 5. Statistical heterogeneity was tested with I2 and chi-square tests. A fixed-effects (inverse variance) model was used when the effects were homogenous, which was only the case for postoperative pain; the other endpoints had moderate or high levels of heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot, and postoperative pain showed no evidence of publication bias, but the endpoint of LOS may have suffered from publication bias or poor methodological quality. We defined the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in pain as 20 mm on the 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

Results

We found no clinically important difference in mean pain scores between patients treated with a tourniquet and those treated without one (5.23 ± 1.94 cm versus 3.78 ± 1.61 cm; standardized [STD] mean difference 0.88 cm; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-1.23; p < 0.001). None of the studies met the MCID of 20 mm in VAS pain scores. There was also no clinically important difference in ROM based on degrees of flexion between the two groups (49 ± 21 versus 56 ± 22; STD mean difference 0.8; 95% CI, 0.4-1.1; p < 0.001). Similarly, we found no difference in mean LOS between groups (5.8 ± 4.4 versus 5.9 ± 4.6; STD mean difference -0.2; 95% CI, -0.4 to 0.1; p = 0.25). A subgroup meta-analysis also showed no clinically important difference in pain between the full-course and half-course tourniquet groups (5.17 ± 0.98 cm versus 4.09 ± 1.08 cm; STD mean difference 1.31 cm; 95% CI, -0.16 to 2.78; p = 0.08).

Conclusions

We found no clinically important differences in pain or ROM between patients treated with and without tourniquets during TKA and no differences between the groups in terms of LOS. In the absence of short-term benefits of avoiding tourniquets, long-term harms must be considered; it is possible that use of a tourniquet improves a surgeon’s visualization of the operative field and the quality of the cement technique, either of which may improve the long-term survivorship or patient function, but those endpoints could not be assessed here. We recommend that the randomized trials discussed in this meta-analysis follow patients from the original series to determine if there might be any long-term differences in pain or ROM after tourniquet use.

Level of Evidence

Level I, therapeutic study.

Introduction

TKA is one of the most widely performed orthopaedic surgical procedures. Tourniquets have been used in TKA since the procedure was first introduced [20]. Tourniquets have been used as a means of achieving a bloodless field for better visualization and bone-cement interdigitation [2, 4], yet the advantage of using a pneumatic tourniquet during TKA to reduce total blood loss is debatable in light of available evidence [22]. In fact, some research has identified adverse effects of tourniquet use such as postoperative pain [21, 32], reactive hyperemia [11, 35], venous thromboembolism [38], and recovery time related to tourniquet use in TKA; therefore, some knee surgeons operate without using a tourniquet [4].

We are aware of no guidelines or recommendations for the use of a tourniquet in TKA or whether it is of benefit [23, 39]. Although longer term endpoints such as durability (which might be influenced by a surgeon’s visualization of the operative field or the quality of the cement technique) would be of interest, to our knowledge, no randomized trials have looked at these questions. By contrast, a number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have disagreed on whether tourniquet use is associated with increased pain [6, 13, 14, 21, 32, 34], decreased ROM [12, 23, 24, 36], or increased length of stay (LOS) in the hospital [14, 24, 33, 35], all of which are important endpoints to clinicians and their patients, and so a meta-analysis of RCTs about tourniquet use during TKA may prove informative.

We therefore performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs on tourniquet use during TKA to determine whether use of a tourniquet during TKA (either for the entire procedure or some portion of it) is associated with (1) increased postoperative pain; (2) decreased ROM; and (3) longer LOS compared with TKAs performed without a tourniquet.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Criteria

This study was a systematic review of RCTs and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines for RCTs [26, 27]. The search strategy for RCTs was developed under the guidance of database experts by using MeSH search terms and the following Boolean search string: (replacement OR arthroplasty) AND knee AND tourniquet AND/OR pain. The following databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to February 1, 2015. Publication types were limited to RCTs in the advanced search menu.

Two reviewers (EMD, AA) completed the searches separately and then crossreferenced the results. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion, therefore maximizing the detection of all relevant studies. The title of each article was assessed and if deemed potentially relevant, the article abstract was reviewed to ascertain whether it met the criteria for full article retrieval. The complete article was then critically assessed as to whether it was eligible for inclusion in the systematic review based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Criteria for inclusion in the primary search were (1) a RCT; (2) a study population of any nationality and language with mixed gender > 16 years of age treated with a primary knee arthroplasty under two different tourniquet controls (nontourniquet use being one possibility); and (3) some assessment of postoperative pain. Studies with nonrandomized trials, incomparable groups, or observational data cannot be included in a systematic review because they incur biases that cannot be corrected by meta-analysis. Therefore, we excluded all non-RCTs, retrospective studies, case reports, comments, letters, editorials, protocols, guidelines, unpublished articles, and review papers. Other exclusion criteria left out trials lacking a control group involving revision knee arthroplasty or any cadaveric studies. All authors of included papers were contacted and the complete data and statistical set for their study were requested.

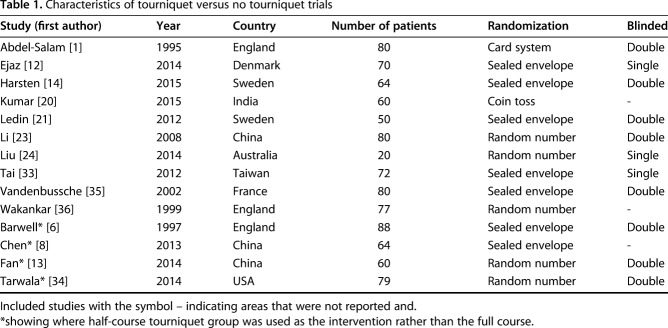

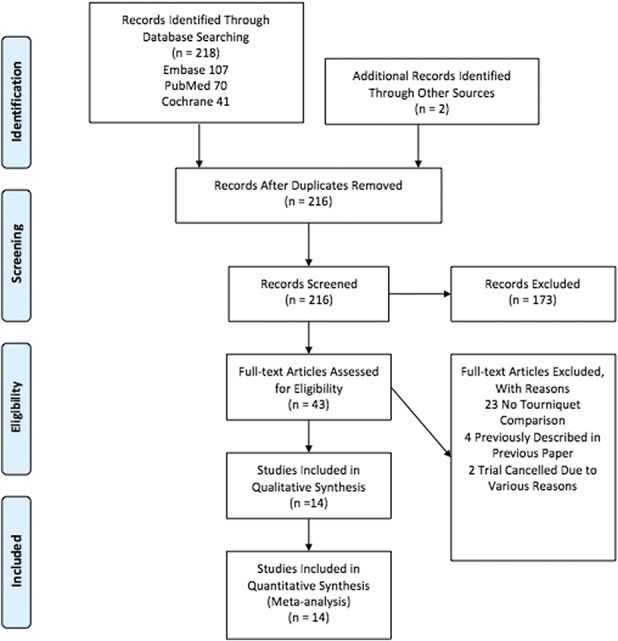

A total of 218 results were obtained relating to the outcome of pain and tourniquet use in TKA (Fig. 1). Additional records identified through reference lists totaled two. After the exclusion of duplicates, 216 records underwent screening for inclusion; 44 full-text studies were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 29 full-text studies were excluded for the following reasons: 23 lacked a nontourniquet comparison cohort; four included a cohort previously described in another study; and two trials were cancelled. A total of 14 studies met the inclusion criteria for the quantitative synthesis (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

The PRISMA 2009 flow diagram shows 14 studies were analyzed.

Table 1.

Characteristics of tourniquet versus no tourniquet trials

Meta-analysis Methodology

Meta-analysis was completed using Review Manager (RevMan, Version 5.3; The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014), thereby combining the relevant effects of interest from our identified studies [16].

Assessment of all outcomes took place within two groups: the first had a tourniquet inflated for the entirety of the surgery and the second group was not given a tourniquet during the procedure. A subgroup analysis of the studies using half-course tourniquets was performed. In using a half-course tourniquet, the tourniquet is inflated from osteotomy until the leg is wrapped with bandages; this is a shorter time course than full-course tourniquets, when the tourniquet is inflated from incision until the leg is wrapped [9].

All articles assessing pain include a numeric value allocated to their pain scale. The visual analog scale (VAS) primarily assesses patient pain in a hospital setting through a numeric and pictorial linear rating between 1 and 10. The VAS is reliable and valid in assessing the intensity of musculoskeletal knee pain states [7]. We considered the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for our primary study endpoint (VAS pain scores) to be ≥ 20 mm on a 100-mm scale [19]. Differences smaller than that were not considered clinically important. A forest plot summarized the combined overall effect of the included studies.

Statistical heterogeneity was tested with I2 and chi-square tests [16]. A fixed-effects (inverse variance) model was used when the effects were assumed to be homogenous (p > 0.05). Statistical heterogeneity is implied when p < 0.05; thus, a random-effects model was used in those circumstances.

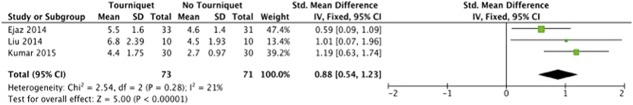

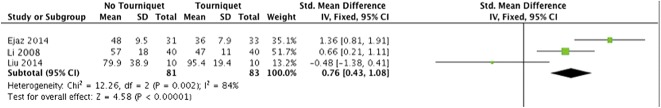

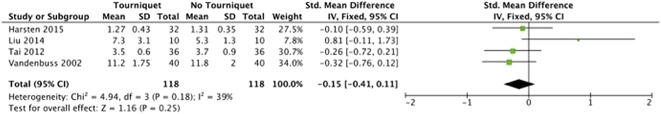

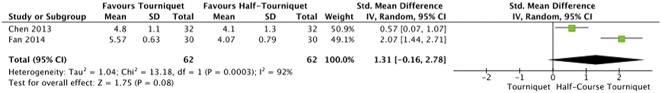

On postoperative pain (Fig. 2), there was a low level of heterogeneity (I2 = 21%). The meta-analysis of ROM (Fig. 3) exhibited a high level of heterogeneity (I2 = 81%). There was a moderate level of heterogeneity (I2 = 39%) within the meta-analysis of LOS (Fig. 4). For half-course tourniquet use, a high level of heterogeneity (I2 = 92%) was seen (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of postoperative pain comparing tourniquet versus no tourniquet (Forest plot) indicating the SD of the mean difference.

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of postoperative ROM comparing tourniquet versus no tourniquet (Forest plot) indicating the SD of the mean difference.

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of postoperative LOS comparing tourniquet versus no tourniquet (Forest plot) with Std. indicating the SD of the mean difference.

Fig. 5.

Meta-analysis of postoperative pain comparing tourniquet versus half-course tourniquet (Forest plot) with Std. indicating the SD of the mean difference.

Methodological Quality Assessment

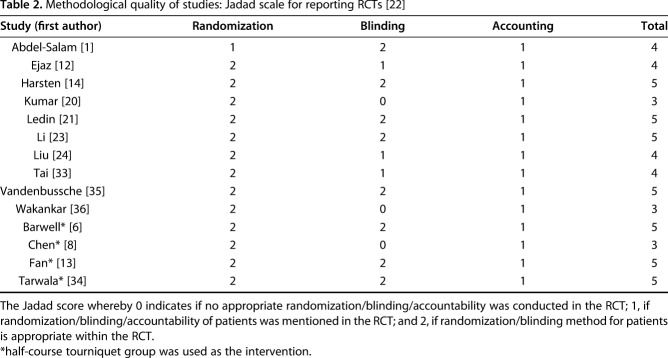

We only included randomized studies (Level I evidence) within our review in keeping with the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool [16]. We evaluated the RCTs with the following key domains: adequate sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding; incomplete outcome data; free of selective reporting and free of other bias; no support by funding; and valid sample size estimation. The Jadad scale for reporting RCTs was used to ascertain the overall methodological quality of the included studies by assessing randomization, blinding, and accounting of each trial [17] (Table 2). As a result of the limited trials available, all manuscripts that included pain as an outcome variable were included.

Table 2.

Methodological quality of studies: Jadad scale for reporting RCTs [22]

The methodological quality scores using the Jadad scale of the included studies ranged from 3 to 5 with a maximum possible score of 5 (Table 2). The median score was 4 with six studies considered good quality, that is, a score of 5. The majority of studies scored poorly as a result of inadequate blinding of some staff, who would have a major impact on the patient undergoing TKA postoperatively such as physiotherapists and nurses. On occasion, even the patients themselves had not been blinded to the use or nonuse of a tourniquet as a result of the varieties in preparation and setup of the operation. The lack of blinding permitted the potential for type II statistical errors regarding postoperative pain and ROM outcomes. Most studies had an adequate amount of randomization through various approved methods.

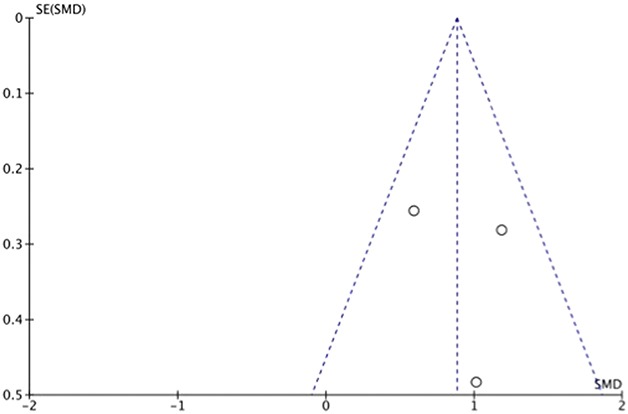

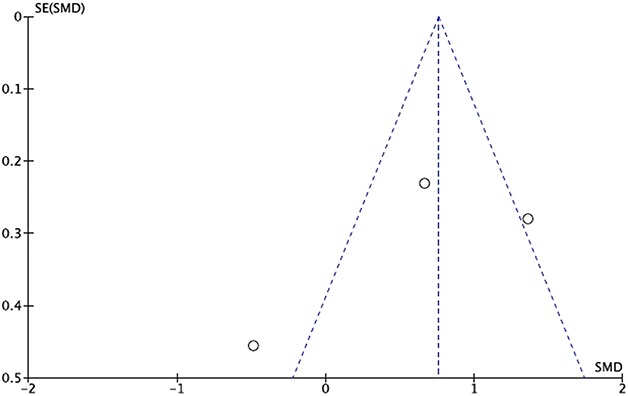

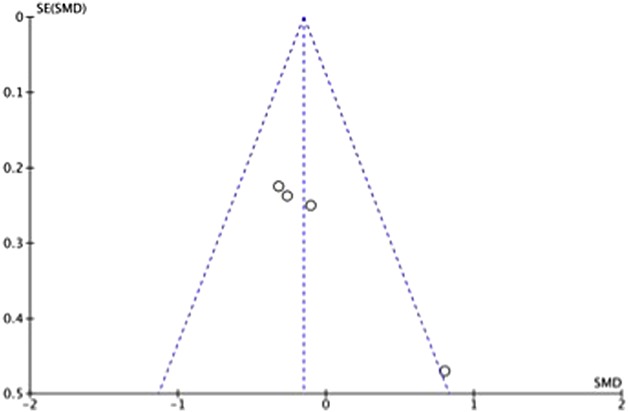

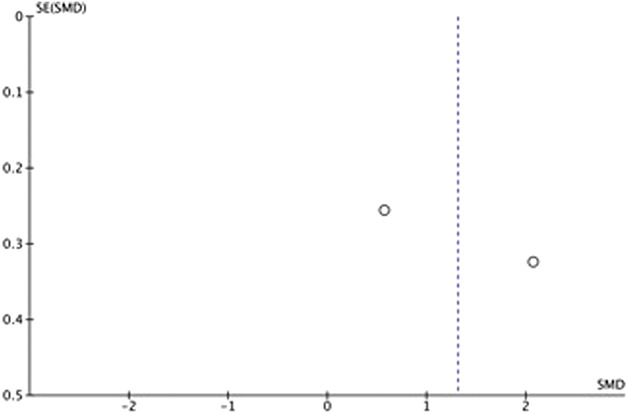

Manuscripts reporting on pain were assessed for publication bias using a funnel plot. The funnel plot on postoperative pain under visual inspection appeared to be symmetrical (Fig. 6), decreasing the likelihood of publication bias. As for ROM, the funnel plot under visual inspection appeared to be somewhat symmetrical (Fig. 7). In contrast, the funnel plot on LOS under visual inspection did not appear to be symmetrical (Fig. 8), which could be a sign of publication bias or poor methodological quality being present in the manuscripts. The subgroup meta-analysis for pain with half-course tourniquet use was also observed to be symmetrical (Fig. 9).

Fig. 6.

Funnel plot of postoperative pain comparing tourniquet versus no tourniquet with standardized mean difference (SMD) on the x-axis plotted against the standard error (SE) on the y-axis.

Fig. 7.

Funnel plot of postoperative ROM comparing tourniquet versus no tourniquet with standardized mean difference (SMD) on the x-axis plotted against the standard error (SE) on the y-axis.

Fig. 8.

Funnel plot of postoperative LOS comparing tourniquet versus no tourniquet with standardized mean difference (SMD) on the x-axis plotted against the standard error (SE) on the y-axis.

Fig. 9.

Funnel plot of postoperative pain comparing tourniquet versus half-tourniquet with standardized mean difference (SMD) on the x-axis plotted against the standard error (SE) on the y-axis.

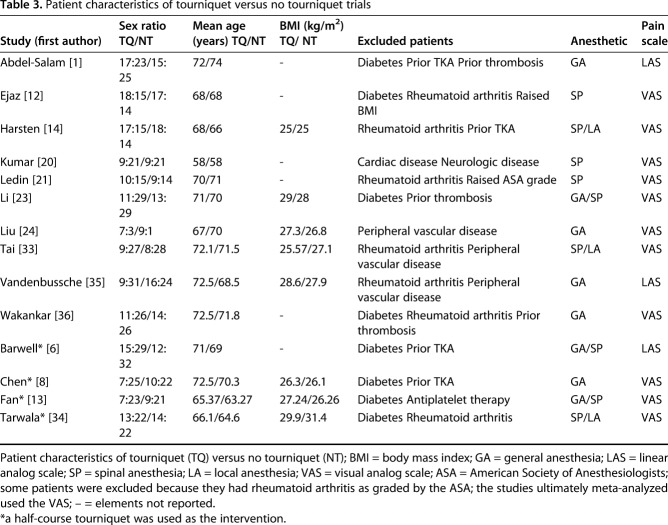

Methodological Characteristics

All studies analyzed reported the total number of patients included along with the comparison groups’ breakdown of patient numbers, mean age, and sex ratio (Table 3). A total of 14 RCTs involving 939 knees were analyzed in this systematic review, 10 of which were reviewed for postoperative pain and ROM assessment and four for our subgroup meta-analysis on half-course tourniquet use. In all, the tourniquet group included 471 knees, whereas the no-tourniquet group included 468 knees. However, as a result of a lack of postoperative pain analyses and SDs in seven of the 10 RCTs, our investigation of postoperative pain included a total of three RCTs with 144 patients. A lack of postoperative ROM analyses, SDs, and ROM-reporting consistencies, that is, two studies reported the number of days taken to reach a set degree of flexion rather than the degree of flexion reached at set time points as was classically done, meant that three RCTs with 164 patients were available for ROM analysis. For our investigation of LOS, only four RCTs with 236 patients had documented LOS and so were available for analysis. Subgroup meta-analysis took place within the remaining four RCTs. Of the four RCTs identified, only two with a total of 124 TKAs were comparable based on their use of a half-course tourniquet versus full tourniquet use. A total of 10 RCTs compiled outcomes of 564 patients (10 rather than 11 because one study was used for both pain and ROM analysis) when reviewing tourniquet use compared with no-tourniquet use during TKA. Overall, the standardization and reporting of outcomes were extremely variable. Blinding in three studies was not apparent.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics of tourniquet versus no tourniquet trials

Patient Characteristics

The patient sex data and mean patient age were well recorded in all studies (Table 3). Patient age ranged from 58 to 74 years and was comparable between tourniquet and no-tourniquet groups in each study. The male-to-female ratio in each RCT was well proportioned between the two study groups. Mean patient age and sex ratios were also found to be comparable in the subgroup meta-analysis of half-course tourniquet use. Mean body mass index (BMI) data reporting was variable among the studies, whereby six studies did not report mean BMI data or patient height and weight from which the mean BMI may have been calculated. Excluded patients in each individual study were well documented and consistent with common methodology. Anesthetic use for each study varied among general, spinal, and local anesthetic based on individual anesthetic team preferences, which accurately reflects daily practice. Pain was measured using the VAS and recorded as numbers.

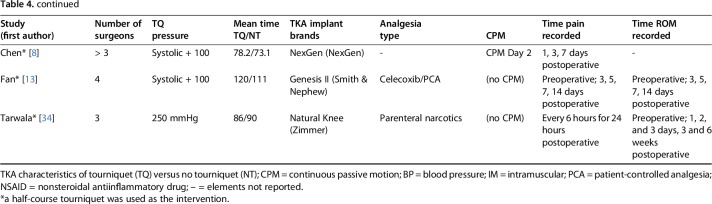

TKA Characteristics

Tourniquet and no-tourniquet groups within studies appeared to follow comparable surgical plans: operating times and anesthesia type were similar if not the same (Table 4). This was found to be true for the studies using half-course tourniquets as well. Three studies stated that a single orthopaedic surgeon performed the TKAs during the trial, whereas four had a mixture of three or more operating surgeons perform the TKAs. Six studies did not provide information on the participating number of surgeons involved. Tourniquet pressure was documented in all studies with no existing standardization. Mean tourniquet time was recorded for all studies except one. TKA implant brands were documented in all studies except two with major variation noted between studies as is common in clinical practice. Analgesia type was listed in every study except one. Continuous passive motion (CPM) was only used in four studies with no CPM use in the remaining seven studies and no documentation of the same in three studies.

Table 4.

TKA characteristics of tourniquet versus no tourniquet trials

All studies had some variation around when pain and ROM were assessed (Table 4). Most studies recorded pain preoperatively—an important prognostic factor for ROM after TKA [5]—and then assessed pain after surgery, typically to approximately 3 days after the operation. Only two studies [1, 6] recorded postoperative pain 4 hours after surgery, whereas one study [36] went so far as to assess for pain 4 months after surgery. All studies except one [35] assessed ROM preoperatively. Postoperatively, ROM generally was assessed at 1 week, 6 weeks, and 1 year. One study [21] went as far as measuring ROM 2 years after surgery. Because of the variation and the limited availability of ROM data, we used ROM measurements in degrees of flexion taken at 2 days from Ejaz et al. [12] because the next available data would have been at 8 weeks, which would be less comparable with data from Li et al. [23] (in that study, ROM measurements were taken at 1, 3, and 7 days). ROM data at 2 weeks were also used from Liu et al. [24] because this was the earliest measurement available.

Results

Pain

We found no clinically important difference in mean pain scores (Fig. 2) between patients treated with a tourniquet and those treated without one (5.23 ± 1.94 cm versus 3.78 ± 1.61 cm; standardized [STD] mean difference 0.88 mm; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-1.23; p < 0.001). None of the studies met the MCID of 20 mm in VAS pain scores.

ROM

We found no clinically important difference in ROM (Fig. 3) between patients treated with a tourniquet and those treated without one (49° ± 21° versus 56° ± 21°; STD mean difference 0.8; 95% CI, 0.4-1.1; p < 0.001).

LOS

We found no difference in mean LOS (Fig. 4) between patients treated with a tourniquet and those treated without one (5.8 ± 4.4 days versus 5.9 ± 4.6 days; STD mean difference -0.2; 95% CI, -0.4 to 0.1; p = 0.25).

Comparison of Full-course and Half-course Tourniquet Use

A subgroup meta-analysis showed no clinically important difference in pain (Fig. 5) between full-course and half-course tourniquet groups (5.17 ± 0.98 cm versus 4.09 ± 1.08 cm; STD mean difference 1.31 cm; 95% CI, -0.16 to 2.78; p = 0.08). None of the studies met the MCID of 20 mm in VAS pain scores.

Discussion

TKA remains one of the most widely performed orthopaedic surgical procedures, and tourniquet use has been considered an important element of the operation since it first was developed. More recently, however, the once highly regarded advantages of tourniquet use—achieving a bloodless field for visualization and cement interdigitation [3, 10, 25, 28, 30, 31] —have come under great scrutiny in light of its potential disadvantages. Indeed, avoiding the use of a tourniquet in TKA (so as to prevent complications such as pain and improve on important patient outcomes like ROM and LOS) has been proposed and debated heavily [23, 32]. There have been very few RCTs on tourniquet use and ROM; and tourniquet-related pain has been poorly assessed by prior studies in patients undergoing TKA [32]. We therefore performed a systematic review to determine whether performing TKA without a tourniquet results in less postoperative pain, greater ROM, and shorter LOS compared with performing TKA with a tourniquet.

This systematic review is limited by the quality and sample size of the available studies. Small sample sizes related to the small number of RCTs published was a limitation of this analysis. We sought to remedy this by conducting an extensive search strategy to ensure all potentially relevant papers were identified and reviewed. The definition of postoperative pain and ROM along with their reporting varied greatly or lacked standardization in the included studies. This can likely be attributed to the limited number of trials available, which prompted us to include all manuscripts that included pain as an outcome variable. This is also why we included in the analysis all studies that met our inclusion criteria so as to minimize the bias from the studies with underreporting (Table 1). Moreover, we managed to study diversity by performing a subgroup analysis (Fig. 5). There was generally a poor description of specific details pertaining to the application and settings of the tourniquet. In light of this, it is important to note that any lack in standardization might be the result of the fact that the study period spanned three decades making it more likely that heterogeneity would be apparent. Only one of the authors we contacted from the list of included studies responded [24]; however, he was also the only author who did not report data needed for one of our endpoints of interest (ROM) and so after his response, we were confident that all data that met our inclusion criteria and PRISMA reporting guidelines for the meta-analysis of RCTs had been reviewed.

Although tourniquet time, pressure, and time of postoperative pain evaluation were variable across studies, we found that all included RCTs had controlled for these factors within their own tourniquet and nontourniquet groups (Table 4). Because these factors were comparable between experimental and control groups—that is, time of pain evaluation was the same—endpoints like postoperative pain, ROM, and LOS could still be properly assessed. Finally, it is important to note that we excluded analysis of some important patient outcomes—namely, venous thromboembolism and muscle ischemia—because these two main complications of tourniquet use in TKA have been extensively researched [15, 29], whereas short-term outcomes, especially postoperative pain, have been traditionally difficult to analyze and have been poorly assessed by prior studies. This is despite the fact that pain is a common complaint during the early postoperative period after tourniquet use [37] and can result in delayed rehabilitation [38].

We found no clinically important differences between the groups in terms of pain or ROM. It is important to note that the results represent early postoperative ROM because we used ROM measurements in degrees of flexion taken at 2 days from Ejaz et al. [12], 3 days from Li et al. [23], and 2 weeks from Liu et al. [24]. Given that these short-term endpoints did not favor the avoidance of the tourniquet, we believe surgeons should decide whether the potential benefits of tourniquet use—perhaps including better visualization or improved bone-cement interdigitation—may justify the use of a tourniquet, and future studies should look at survivorship of the TKAs performed in the randomized trials we assessed here.

The third objective of our study was to assess whether tourniquet use adversely affected LOS. We found no difference in mean LOS between patients treated with a tourniquet and those treated without one. This finding seems logical given that we found no adverse effect on patient outcomes such as pain and ROM with tourniquet use. It is also in keeping with previous studies; for example, Jiang et al. [18] conducted a systematic review of 26 RCTs showing no measurable effect on duration of hospital stay with tourniquet use compared with without.

As part of the analysis of our first objective on postoperative pain, we also conducted a subgroup assessment comparing half-course tourniquet use with full-course use. In contrast to previous literature [9], we found that half-course use was not clinically superior to full-course use in terms of pain reduction. This finding might validate the use of the tourniquet for the entire procedure, at least in that it does not lead to more postoperative pain compared with half-course use—and especially if there may be greater potential benefit with full-course use (such as reduced intraoperative blood loss and operative time).

This systematic review and meta-analysis found no clinically important differences in pain or ROM between patients treated with and without tourniquets during TKA and no differences between the groups in terms of LOS. In the absence of short-term benefits of avoiding tourniquets, long-term harms must be considered; it is possible that use of a tourniquet improves a surgeon’s visualization of the operative field and the quality of the cement technique, either of which may improve the long-term survivorship or patient function, but those endpoints could not be assessed here.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following: Ms Grainne McCabe, RCSI librarian, for assistance in formulating the search string; Mr Patrick Dicker, RCSI statistician, for assistance in statistical meta-analyses; and Mr Olaf Almqvist for assistance in proofreading.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that neither he or she, nor any member of his or her immediate family, has funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

This work was performed at the Royal College of Surgeons, Dublin, Ireland.

References

- 1.Abdel-Salam A, Eyres KS. Effects of tourniquet during total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:250-253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aglietti P, Baldini A, Vena LM, Abbate R, Fedi S, Falclani M. Effect of tourniquet use on activation of coagulation in total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2000;371:169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed I, Fraser L, Sprowson A, Wall P. Tourniquets for the use of total knee arthroplasty: are patients aware of the risks? Ann Orthop Rheumatol. 2016;4:1071. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alcelik I, Pollock RD, Sukeik M, Bettany-Saltikov J, Armstrong PM, Fismer P. A comparison of outcomes with and without a tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27:331-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bade M, Kittelson J, Kohrt W, Stevens-Lapsley J. Predicting functional performance and range of motion outcomes after total knee arthroplasty. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93:579-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barwell J, Anderson G, Hassan A, Rawlings I. The effects of early tourniquet release during total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized double-blind study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:265-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boeckstyns ME, Backer M. Reliability and validity of the evaluation of pain in patients with total knee replacement. Pain. 1989;38:29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen LB, Tan Y, Al-Aidaros M, Wang H, Wang X, Cai SH. Comparison of functional performance after total knee arthroplasty using rotating platform and fixedbearing prostheses with or without patellar resurfacing. Orthop Surg. 2013;2:112–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S, Li J, Peng H, Zhou J, Fang H, Zheng H. The influence of a half-course tourniquet strategy on peri-operative blood loss and early functional recovery in primary total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2013;38:355-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke D. Necessity of a tourniquet during cemented total knee replacement; let the debate continue. Orthopedics and Rheumatology Open Access Journal. 2018;10:322‒323. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke MT, Longstaff L, Edwards D, Rushton N. Tourniquet-induced wound hypoxia after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ejaz A, Laursen AC, Kappel A, Laursen MB, Jakobsen T, Rasmussen S, Nielsen PT. Faster recovery without the use of a tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized study of 70 patients. Acta Orthop. 2014;85:422-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan Y, Jin J, Sun Z, Li W, Lin J, Weng X, Qiu G. The limited use of a tourniquet during total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Knee . 2014;21:1263-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harsten A, Bandholm T, Kehlet H, Toksvig-Larsen S. Tourniquet versus no tourniquet on knee-extension strength early after fast-track total knee arthroplasty; a randomized controlled trial. Knee . 2015;22:126-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez AJ, de Almeida AM, Favaro E, Sguizzato GT. The influence of tourniquet use and operative time on the incidence of deep vein thrombosis in total knee arthroplasty. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;9:1053–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.2. The Cochrane Library, Issue 4. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. [cited May 10, 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang FZ, Zhong HM, Hong YC, Zhao GF. Use of a tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20:110-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz N, Paillard F, Ekman E. Determining the clinical importance of treatment benefits for interventions for painful orthopedic conditions. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar N, Yadav C, Singh S, Kumar A, Vaithlingam A, Yadav S. Evaluation of pain in bilateral total knee replacement with and without tourniquet; a prospective randomized control trial. J Clin Orthop Trauma . 2015;6:85-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ledin H, Aspenberg P, Good L. Tourniquet use in total knee replacement does not improve fixation, but appears to reduce final range of motion. Acta Orthop. 2012;83:499-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li B, Wen Y, Wu H, Qian Q, Lin X, Zhao H. The effect of tourniquet use on hidden blood loss in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop . 2008;33:1263-1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Yin L, Chen ZY, Zhu L, Wang HL, Chew W, Yang G, Zhang YZ. The effect of tourniquet use in total knee arthroplasty: grading the evidence through an updated meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol . 2014;24:973–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu D, Graham D, Gillies K, Gillies RM. Effects of tourniquet use on quadriceps function and pain in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res . 2014;26:207-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majkowski RS, Bannister GC, Miles AW. The effect of bleeding on the cement–bone interface. An experimental study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:293–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet . 1999;354:1896-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med . 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozkunt O, Sariyilmaz K, Gemalmaz H, Dikici F. The effect of tourniquet usage on cement penetration in total knee arthroplasty. Medicine . 2018;97:e9668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer SH, Graham G. Tourniquet-induced rhabdomyolysis after total knee replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl . 1994;6:416–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfitzner T, von Roth P, Voerkelius N, Mayr H, Perka C, Hube R. Influence of the tourniquet on tibial cement mantle thickness in primary total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc . 2016;24:96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sculco P, Gruskay J, Nodzo S, Carrol K, Shanaghan K, Haas S, Gonzalez Della Valle A. The role of the tourniquet and patella position on the compartmental loads during sensor-assisted total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty . 2018;33:S121-S125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith TO, Hing CB. Is a tourniquet beneficial in total knee replacement surgery? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Knee . 2010;17:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tai TW, Lin CJ, Jou IM, Chang CW, Lai KA, Yang CY. Tourniquet use in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:1121–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarwala R, Dorr LD, Gilbert PK, Wan Z, Long WT. Tourniquet use during cementation only during total knee arthroplasty: a randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2014;472:169-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vandenbussche E, Duranthon LD, Couturier M, Pidhorz L, Augereau B. The effect of tourniquet use in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop . 2002;26:306–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wakankar HM, Nicholl JE, Koka R, D’Arcy JC. The tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br . 1999;81:30–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Worland RL, Arredondo J, Angles F, Lopez-Jimenez F, Jessup DE. Thigh pain following tourniquet application in simultaneous bilateral total knee replacement arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:848–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zan PF, Yang Y, Fu D, Yu X, Li GD. Releasing of tourniquet before wound closure or not in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty . 2015;30:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang W, Li N, Chen S, Tan Y, Al-Aidaros M, Chen L. The effects of a tourniquet used in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]