ABSTRACT

The marriage of children below 18 is widely recognized in international human rights agreements as a discriminatory global practice that hinders the development and well-being of hundreds of millions of girls. Using a new global policy database, we analyze national legislation regarding minimum marriage age, exceptions permitting marriage at earlier ages, and gender disparities in laws. While our longitudinal data indicate improvements in frequencies of countries with legal provisions that prohibit marriage below the age of 18, important gaps remain in eliminating legal exceptions and gender discrimination.

KEYWORDS: Child marriage, early marriage, minimum marriage age, gender discrimination, gender inequality, comparative law, marriage law, family law, child rights, cross-national analysis, international treaties, conventions

Introduction

The marriage of children below 18 is widely recognized in international human rights agreements as a harmful, discriminatory global practice. International governmental, academic, and advocacy stakeholders have called for countries to establish legislative frameworks that prohibit child marriage and close legal loopholes that permit marriage below the age of 18 (De Silva-De-Alwis 2008; Human Rights Watch 2011, 2013; Jensen and Thornton 2003; Loaiza and Wong 2012; Odala 2013; Raj 2010; UNICEF 2001; Walker 2012). The disproportionately high rate of child marriage among girls compared to boys is recognized by the international community as reflecting gender discrimination (UNICEF 2014). Moreover, because of the well-documented detrimental consequences of child marriage in reduced autonomy, safety, educational attainment, health status, and the long-term negative impacts on girls’ independence and the health and well-being of their children, the practice further perpetuates gender inequalities (Jensen and Thornton 2003) and slows economic development in the nations in which child marriages frequently take place (Vogelstein 2013). Although longitudinal, multilevel research is needed to establish causality, a growing body of research suggests there is an association between protective laws and lower rates of child marriage (Maswikwa et al. 2015), as well as declines in rates of adolescent fertility (Kim et al. 2013).

In this article we examine progress toward universal adherence to the international standard of a legal minimum age of marriage of 18 years old for both girls and boys, the extent to which a range of exceptions permit earlier marriage, as well as gender disparities in laws, through the creation and analysis of new global data based primarily on national legislation. Our findings indicate that despite narrowing gender disparities in legal protections against early marriage over time, widespread discriminatory provisions in legislation that disadvantage girls remain. Furthermore, legal exceptions to minimum age provisions based on parental consent and customary and/or religious laws create loopholes that lower the legal minimum age of marriage below the age of 18 in many countries worldwide.

Background

The practice of child marriage, defined as marriage below the age of 18 years, is deeply gendered. UNICEF (2014) estimates that girls are married before 18 almost five times more than boys. In some countries the gender disparity is much greater: 77 percent of women aged 20–49 were married before 18 in Niger, whereas only 5 percent of men in the same age group were. The disproportionately high rates of child marriage among girls exist not only in countries where prevalence rates are high. In the Republic of Moldova, where child marriage is much less common, the ratio of women aged 20–49 who were married before 18 compared to men is 15 percent versus 2 percent. Of the current global population, UNICEF (2014) estimates that 720 million women were married before the age of 18. More than one-third of those women, approximately 250 million, were married before the age of 15 (UNICEF 2014). Global estimates indicate that almost five million girls are married under the age of 15 each year (Vogelstein 2013).

Several pathways through which the early marriage of girls results in poor outcomes have been identified in the literature. Globally, child brides are often married to men much older than they are. For example, in Mauritania and Nigeria more than half of married girls aged 15–19 are in union with men at least 10 years older than they are (UNICEF 2014). Gaffney-Rhys (2011) suggests that these age gaps create a power imbalance between spouses that is compounded by disparities in educational attainment. While evidence of the impacts of age differences on girls married young is still nascent, researchers suggest that girls with much older partners are likely to lack the ability to establish their position in the household and find it difficult to negotiate with their husbands about their relationship, the household, and family, leaving them with less autonomy and independence, a condition that is likely to persist throughout the marriage (Jensen and Thornton 2003; Mensch 2005). One study using Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data found that women’s autonomy (measured as the ability to go to market or visit family and friends without requiring permission, and as the ability to keep money) and agency/power (measured as the belief that physical abuse was sometimes justified) increase as age of marriage increases (Jensen and Thornton 2003).

There may be additional health impacts due to the relatively unequal status of women married as girls within their marriages. Power differences related to age disparities may hinder girls’ ability to negotiate with their husbands and exert control over their bodies and their sexual and reproductive health. In part because of this limited control and lack of information about options and pressure to begin bearing children, early marriage has been linked to lower contraceptive use (Godha, Hotchkiss, and Gage 2013; Mensch 2005; Nour 2006; Raj et al. 2009; Santhya et al. 2010; Savitridina 1997; UNICEF 2001). Compounded by girls’ lack of control over their sexual lives, this contributes to higher rates of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among women married as children versus those married as adults (Clark 2004; Clark, Bruce, and Dude 2006; Dunkle et al. 2004; Glynn et al. 2001; Hindin and Fatusi 2009; Jain and Kurz 2007; Mathur, Greene, and Malhotra 2003; Murphy and Carr 2007; Nunn et al. 1994; UNICEF 2005, 2014). Furthermore, a substantial body of evidence indicates that women married as children face higher rates of physical, sexual, and emotional violence within marriage than women married as adults (Akmatov et al. 2008; Ebigbo 2003; Erulkar 2013; Gottschalk 2007; Hindin and Fatusi 2009; Hindin, Kishor, and Ansara 2008; Hong Le et al. 2014; Jain and Kurz 2007; Jensen and Thornton 2003; Kishor and Johnson 2004; Mathur, Greene, and Malhotra 2003; Mensch 2005; Muleta and Williams 1999; Ouis 2009; Rahman et al. 2014; Santhya et al. 2010; Speizer and Pearson 2011; UNICEF 2005). There is also evidence that child marriage is associated with an increased risk of poor mental health outcomes, including suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Gage 2013). Using hospital records and survey data, Raj, Gomez, and Silverman (2008) found that in almost one-third of self-immolation cases in three major cities in Afghanistan between 2000 and 2006 for which they had data, forced marriage or engagement during childhood was found to be a cause or precipitating event.

In marriages involving young girls, childbirth tends to occur early (Jensen and Thornton 2003; Maswikwa et al. 2015; UNICEF 2005, 2014; Walker 2012), which is associated with increased health risks resulting in part because of the physical limitations of younger and smaller bodies (Clark, Bruce, and Dude 2006; Ertem et al. 2008; Jain and Kurz 2007; Jensen and Thornton 2003; Loaiza and Wong 2012; Mathur, Greene, and Malhotra 2003; Nour 2006; Raj et al. 2009; Singh and Samara 1996; UNICEF 2005). These include higher rates of complications during labor and delivery such as eclampsia and anemia among others, (Adedoyin and Adetoro 1989; Gaffney-Rhys 2011; Nour 2006, 2009; UNICEF 2001; Zabin and Kiragu 1998), increased morbidity after childbirth (Hindin and Fatusi 2009; Jain and Kurz 2007; Melah et al. 2007; Nour 2006; Onolemhemhem and Ekwempu 1999), and increased risk of mortality for females aged 15–19 versus 20–24 (Nove et al. 2014). Mortality and morbidity are also higher for children born to young mothers (Adedoyin and Adetoro 1989; Ertem et al. 2008; Igwebe and Udigwe 2001; Jain and Kurz 2007; Kumbi and Isehak 1999; Mathur, Greene, and Malhotra 2003; Nour 2006; Raj et al. 2009; Sharma et al. 2008; Shawky and Milaat 2001; UNICEF 2001).

For young girls, child marriage often leads to the interruption or end of their education (Clark, Bruce, and Dude 2006; Field and Ambrus 2008; Lloyd and Mensch 2008; UNICEF 2014). Social norms, family expectations, and in some cases legal restrictions force girls to end their schooling upon marriage (Jain and Kurz 2007; Jensen and Thornton 2003; Mensch 2005). In addition, girls are often expected to take on household tasks and family responsibilities, which can make attending school infeasible. Limiting girls’ education has lifelong and intergenerational impacts on women’s earning potential and financial independence (Vogelstein 2013), as well as on their children’s health and educational outcomes (Gakidou et al. 2010; Sekhri and Debnath 2014). Specifically, evidence based on country-level data has found that increased educational attainment in women of reproductive age is associated with lower rates of child mortality (Gakidou et al. 2010). Research using 2005 household survey data from India showed that delaying a mother’s age of marriage by one year increased the probability that her child was able to perform challenging arithmetic and reading tasks, an association that the authors suggested is likely mediated by mothers’ own increased schooling due to later marriage (Sekhri and Debnath 2014).

In response to the many threats posed by child marriage to the health and development of child brides, their children, and their broader communities, as well as the gender discriminatory nature of this practice, numerous international agreements have called for government action. Through the 1962 Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage, and Registration of Marriages, the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and the 1995 Beijing Platform and Declaration for Action, nearly all of the world’s governments have agreed to take measures to eliminate the practice of child marriage. These agreements exhort state governments to take action by establishing legislation that sets a minimum age of marriage. The CEDAW and CRC Committees have recently reiterated and clarified states’ obligations to prevent and eliminate harmful practices, such as child marriage, through their first ever joint General Recommendation. The Committees recommended that States Parties adopt or amend legislation to ensure that “A minimum legal age of marriage for girls and boys is established, with or without parental consent, at 18 years” (Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and Committee on the Rights of the Child 2014). The document further clarifies that when marriage is allowed at an earlier age under exceptional circumstances, the absolute minimum should not be below 16 years old and that marriage should only be permitted by a court of law based on strictly defined grounds and full, free, and informed consent of the intended child spouse(s) (Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and Committee on the Rights of the Child 2014).

Recent studies indicate that protective legislation may indeed be associated with a lower prevalence of child marriage and lower rates of adolescent fertility. Research using DHS data from sub-Saharan Africa found that a consistent minimum marriage age of 18 or older in national laws (general minimum age of marriage, the minimum age with parental consent, and the age of sexual consent) was associated with lower household rates of child marriage (Maswikwa et al. 2015). In addition, a longitudinal study of national-level child marriage laws and adolescent fertility rates found that countries with strict laws that set a minimum marriage age of 18 without exceptions had greater declines in fertility rates among adolescents (Kim et al. 2013). Building on this emerging evidence of the importance of national minimum age of marriage laws and previous work that examined child marriage policies through CRC and CEDAW reports (Melchiorre 2004), this study contributes the first detailed analysis of child marriage laws using data based on original legislation on a global scale. This is an important advance in the literature because it provides comprehensive current and historical data on national-level minimum age of marriage legislation, including analyses of exceptions that permit the minimum age to be lowered in particular circumstances. In CEDAW and CRC reports, countries do not consistently represent the presence and nature of exceptions in their minimum age of marriage laws; therefore, these reports provide a less reliable source of data. Furthermore, countries are expected to submit reports to these human rights committees every four and five years, respectively. Therefore, there is a lag in the availability of this data, while data based on original legislation can be updated annually.

We compare legislative provisions for the minimum age of marriage, exceptions that permit that age to be lowered, and gender disparities in these laws in 191 countries. These findings are disaggregated by geographic region to provide a comparison of the variation in minimum marriage age laws globally and by national income to examine how and whether child marriage legislation, like child marriage rates, varies by level of economic development.

Methods

Data

To capture the legal provisions shaping child marriage around the world, we built a database for 193 United Nations (UN) Member States. 1 We constructed variables for the minimum age of marriage and exceptions that permit marriage at lower ages under particular conditions. We conducted a systematic review of legislation available as of June 2013 through official country websites, the Lexadin World Law Guide, the Foreign Law Guide, the International Labour Organization (ILO)’s NATLEX database, the Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute, the Asian Legal Information Institute, JaFBase, and libraries, such as the Swiss Institute for Comparative Law, the University of California Los Angeles Law Library, the Harvard Law School Library, and the Northwestern University Library. When legislation was not available from these sources, analysts reviewed country reports and committee concluding observations from the Committee on the Rights of the Child and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women.

For each country, two analysts independently conducted a coding process in which they reviewed the full text of the legislation or reports and translated the minimum age provisions found therein into a set of consistent, quantitatively analyzable categories within a database. Double coding was conducted to ensure accuracy based on agreed-upon coding conventions. In three countries where the minimum age of marriage is legislated at a subnational level, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America, we reviewed legislation for subnational jurisdictions and captured the lowest minimum age provisions.

Sample

Two samples were analyzed in this study to provide both a global overview using recent data and an overview of change over time for a subset of countries. The 2013 cross-sectional analysis included data on legislation in the 191 UN Member States for which information was both available and clear. We were unable to code two countries: St. Kitts and Nevis due to unavailable source information and Myanmar because its legislative provisions were ambiguous. The sample for the longitudinal analyses was collected as part of the Maternal and Child Health Equity 2 research program, which aims to examine how key social policies have an impact on the burden of disease among children and women. This sample includes 106 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) included in the DHS and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys for which we were able to collect complete comparable information about minimum age of marriage laws between 1995 and 2013. The LMIC countries in this sample represent the countries with the highest rates of early marriage.

Variables

General minimum age of marriage

The general minimum age of marriage is the legal age of marriage before special circumstances are considered. We capture the minimum age of marriage for girls and boys separately to evaluate gender discrimination in the level of protection.

Minimum age of marriage with parental consent

In many countries, laws state that minors may legally be married younger than the general minimum age with parental permission or consent. Because most child marriages occur with parental consent and involvement, this exception can undermine legal protections against early marriage; therefore, we capture these exceptions separately. This variable was defined as the minimum age for marriage under the parental consent exception, or if there is no exception based on parental consent, the general minimum age for marriage.

Minimum age of marriage under customary and/or religious law

In addition to these provisions in civil law, parallel customary and/or religious legal systems exist alongside the civil legal system in many countries. These laws often set no minimum age of marriage or set it at lower ages than the provisions in civil law, creating loopholes that permit the marriage of children in certain religious and ethnic communities at much younger ages. This variable is defined as the lowest minimum age under customary and/or religious law where these laws exist, or the general minimum age for marriage for countries in which there is no exception based on customary and/or religious law.

Minimum age of marriage under any circumstances

Often the general minimum age of marriage can also or further be lowered with approval from a judge, the court, or a government official. In some laws a lower age of marriage is legally permitted provided that one of the intended spouses is pregnant or has given birth to a child. These exceptions to the general minimum age of marriage may create loopholes that facilitate the marriage of young children. The lowest minimum age under any exceptions was constructed by including the general minimum age of marriage, the minimum age with parental consent, under customary and/or religious law, with court or other government approval, and when a minor is pregnant or has given birth to a child.

These indicators provide an overview of the legislative frameworks around the world that determine the legal minimum age of marriage, including the most common legal exceptions that permit that age to be lowered. For all variables, when information could not be found for a particular country, the data point was coded as indeterminate.

Analysis

As noted above, minimum age of marriage laws from 191 countries in 2013 were analyzed for this study. Overall results and results by region are presented. In addition, analyses of changes in laws in 106 countries from 1995 to 2013 were conducted and are presented.

Our coded data sets were analyzed to determine the frequency and percentage of countries that set the general legal minimum age of marriage in the following categories: no minimum age, 9–13 years or at puberty, 14–15 years, 16–17 years, and 18 years of age or over. The frequency and percent of countries with a minimum marriage age in each age category under each of the three most common exceptions were also analyzed. These categories include having parental consent, customary and/or religious law, and a grouping of a number of other common cases: instances when the marriage receives approval from a court or other government office (e.g., the president, a governor, a minister, among others) and/or approval of a medical or other expert official (e.g., a social work center, child welfare authorities, and so forth), as well as pregnancy of the girl and when she has given birth. The frequency distribution of the minimum age of marriage using the age categories above was then calculated by region using the six regions defined by the World Bank, and by national income using the four World Bank income classifications as of 2013 where lower-middle income and upper-middle income are combined into a single middle-income category (World Bank 2013). For the general minimum age of marriage and the minimum age with parental consent we also examined differences in provisions for girls and boys.

These analyses were conducted to construct a global picture of the variation in the legal minimum age of marriage, where and to what extent legal provisions meet international standards and where they fall below, where legislative provisions that comply with international standards are undermined by loopholes that permit child marriage, and to what extent minimum marriage ages differ by gender and the magnitude of difference in ages. Regional disaggregation of these findings permits comparison of policy approaches to marriage age regulation around the world. These comparisons help to identify outliers in particular regions, in terms of leaders in protecting girls and countries that are lagging behind. Analyses by income begin to assess whether the level of national economic development supports or explains the legalization of early marriage.

Results

Circumstances under which the marriage of girls below 18 is permitted

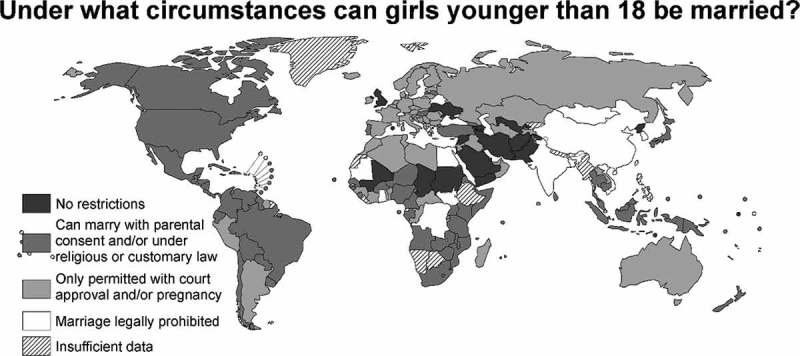

The marriage of girls below 18 is legally permitted in 23 of 191 countries globally based on the general minimum age of marriage (see Figures 1 and 2). When exceptions to civil law provisions for the minimum age of marriage based on customary and/or religious law are considered, our data show that girls may be married below 18 in 30 countries (18 percent). The marriage of girls below the age of 18 is legally permitted in many more countries when considering cases in which parents or guardians provide consent. Ninety-nine countries (52 percent) permit girls under the age of 18 to be married with parental consent.

Figure 1.

Under what circumstances can girls younger than 18 be married?

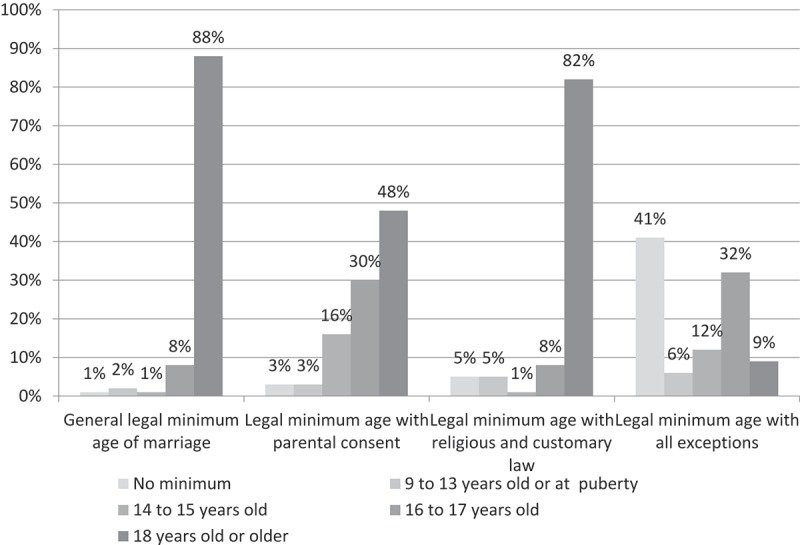

Figure 2.

Legal minimum age of marriage for girls under different circumstances.

Circumstances under which the marriage of girls below the age of 18 is permitted, by region

The frequency with which girls may be married below the age of 18 with parental permission varies by region. A substantially higher percentage of countries in the Americas permit the marriage of girls below the age of 18 with parental consent, 90 percent compared to 62 percent in East Asia and the Pacific, 53 percent in the Middle East and North Africa, 50 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, 38 percent in South Asia, and 26 percent in Europe and Central Asia.

We also find variation by region in the percentage of countries where girls may be married below the age of 18 when customary and religious laws are considered. The Middle East and North Africa has the highest percentage of countries allowing early marriage with these exceptions at 41 percent, compared to 33 percent in South Asia, 26 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, 23 percent in East Asia and the Pacific, 12 percent in Europe and Central Asia, and 3 percent in the Americas.

Circumstances under which the marriage of girls below the age of 18 is permitted, by income

There is no clear gradient in country income for those nations allowing girls to be married below the age of 18 with parental permission. A slightly higher percentage of low- and high-income (57 percent and 58 percent respectively) compared to middle-income countries (40 percent) permit early marriage with parental permission. Low-income countries are least likely to have no minimum age or permit marriage with parental consent between 9 and 13 years of age (0 percent versus 9 percent of middle-income countries and 6 percent of high-income countries).

Across GDP, a large majority of countries prohibit marriage below age 18 when religious and/or customary law exceptions are taken into account, although the percentage increases with income: 71 percent of low-income, 82 percent of middle-income, and 86 percent of high-income countries.

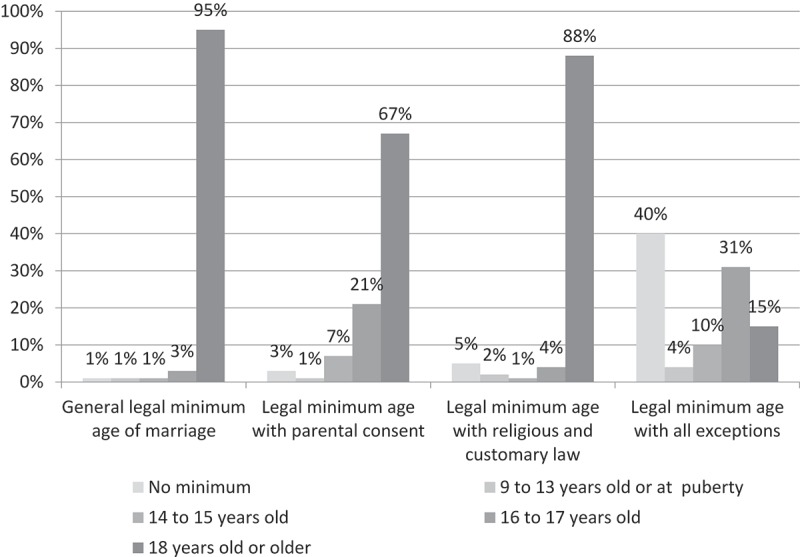

Gender disparities in child marriage laws as of 2013

Figures 2 and 3 present the frequency distribution of the minimum age of marriage across five age groups for girls and for boys separately. Two countries (Saudi Arabia and Yemen) do not set a minimum legal age of marriage for girls or boys. Based on the general legal minimum age of marriage, an additional seven countries (5 percent) set the minimum age below 18 for boys. Boys may be married as young as 13 in Lebanon, at 15 in Iran, at 16 in Andorra and the United Kingdom, and at 17 in Israel, Kuwait, and Timor-Leste. Significantly more countries set a minimum age below 18 for girls. One country (Lebanon) allows girls to be married as young as 9, one permits the marriage of girls at puberty (Sudan), one sets the minimum age for girls at 13 (Iran), two set it at 15 (Chad and Kuwait), and 16 countries set it at 16 or 17. The majority of countries, 168, set a general minimum age of marriage of at least 18 for girls.

Figure 3.

Legal minimum age of marriage for boys under different circumstances.

When parental consent exceptions to the minimum age are included in analyses, the minimum age of marriage distribution is substantially changed (see Figures 2 and 3). In six countries (3 percent), legislation does not explicitly specify a minimum age of marriage if parents provide consent for the marriage. In other words, children of either gender can be married below the general minimum age of marriage with no lower limit stated in law as long as their parents provide consent. The minimum age of marriage for boys, including exceptions based on parental consent, is below 18 in 63 countries (33 percent). In one country (Sudan), boys may be married at 10, in one (Lebanon) they can be married at 13, in 14 (7 percent) they can be married between 14 and 15 years old, and in another 41 countries (21 percent) they may be married at 16 or 17 (see Figure 3). Once again, far more countries allow the early marriage of girls. In six countries (3 percent), girls can be married at ages 9–13 or at puberty, in 30 countries (16 percent) at 14 or 15, and in 57 countries (30 percent) at 16 or 17 (see Figure 2).

When exceptions to civil law provisions for the minimum age of marriage based on customary and/or religious law are included in analyses, our data show that in eight countries there is no explicit minimum age of marriage for girls or boys for at least part of the population for whom customary and/or religious law is valid. In one country (Sudan) boys may be married at 10, in one they may be married at 13 (Lebanon), in one they may be married at 15 (Iran), and in six they may be married at 16 or 17 (see Figure 3). Under customary and religious law, as under other minimum marriage age laws, girls are less protected than boys. In eight countries girls may be married as young as 9–13 or at puberty, in one country they may be married at 15 (Chad), and in 13 countries they may be married at 16 or 17 (see Figure 2).

In total, there are 104 countries in which girls can be married below 18 under parental consent and customary and religious law exceptions and 70 countries in which boys can be married below 18 under these exceptions (see Figures 2 and 3).

There are a number of other common cases in which countries legally permit the minimum age of marriage to be lowered, including, among others, pregnancy, childbirth, approval from a medical or other expert or from a judge or other government official. Including these additional exceptions, we find that only 16 countries worldwide prohibit the marriage of girls below 18. In 71 countries there is no explicit minimum age of marriage under these conditions. In 11 countries girls can be married from 9 to 13 or at puberty, in 21 countries they can be married at 14 or 15, and in 55 countries they can be married at 16 or 17.

Magnitude of the gender differences in minimum age of marriage, by region

Figure 4 shows the difference in the minimum age of marriage with parental consent for girls relative to boys for each country globally. In total, 59 countries have minimum marriage age laws that permit girls to be married younger than boys with parental consent. In South Asia 50 percent of countries set a younger minimum age of marriage with parental consent for girls than boys, as do 41 percent in the Americas, 40 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, 38 percent in East Asia and the Pacific, 32 percent in the Middle East and North Africa, and 9 percent in Europe and Central Asia. In 17 countries the legislated difference is three or four years; this is most common in South Asia (38 percent of countries) and sub-Saharan Africa (21 percent of countries).

Figure 4.

Is there a gender disparity in the minimum legal age of marriage with parental consent?

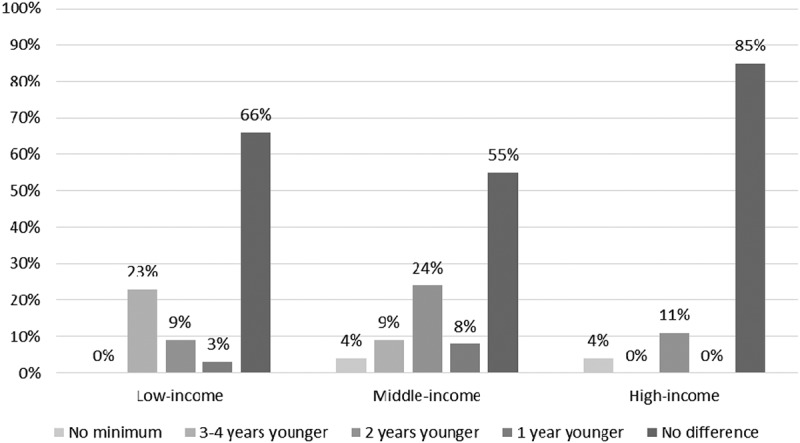

Magnitude of the gender differences in minimum age of marriage, by income

Figure 5 shows the difference in the minimum age of marriage with parental consent for girls relative to boys by national income category. In a majority of countries in each income category there is no difference in the minimum age of marriage with parental consent for girls and boys; however, the percentage of countries with no difference in high-income countries is considerably higher than for low- and middle-income countries: 66 percent for low-income countries, 55 percent for middle-income, and 85 percent for high-income countries. Differences of three to four years are most common in low-income countries compared to middle- and high-income countries and a clear gradient was found (23 percent versus 9 percent and 0 percent, respectively).

Figure 5.

Difference in legal minimum age of marriage with parental consent for girls compared to boys, by income.

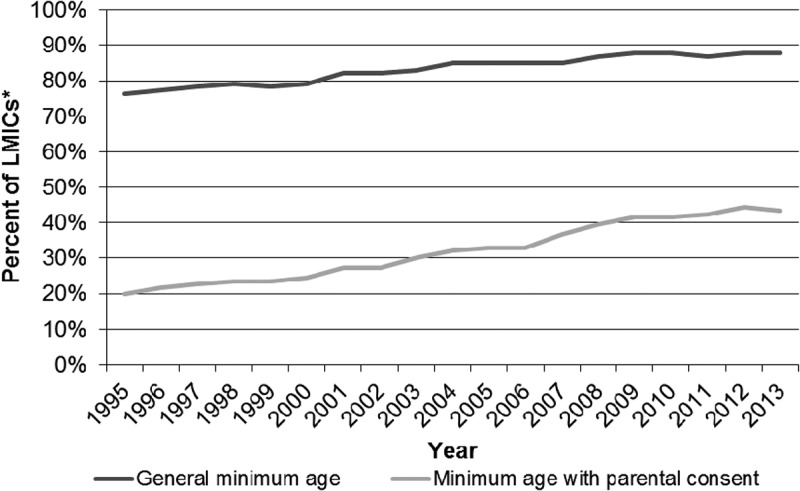

Changes in the legal minimum age of marriage for girls between 1995–2013

Analysis of the 106 LMICs in our longitudinal sample shows that between 1995 and 2013 the percentage of countries in which girls were legally permitted to be married below 18 years old under the general minimum marriage age fell from 24 percent to 12 percent (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

From 1995 to 2013, what percentage of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) set a legal minimum age of marriage for girls of at least 18?

There was a more marked decline in the proportion of countries that permitted girls to marry before 18 with parental consent (see Figure 6). In 1995, 80 percent of the 106 countries in our longitudinal sample permitted girls under 18 to be married if their parents gave consent. This proportion fell to 75 percent in 2000, 67 percent in 2005, 58 percent in 2010, and 57 percent in 2013 (see Figure 6). Over the 18 years from 1995 to 2013, 31 percent of countries increased the legal minimum age of marriage for girls with parental consent; however in 5 percent of those countries, the minimum age remained under 18. Forty-eight percent permitted marriage below 18 with parental consent in 1995 and did not change their laws as of 2013. Moreover, in two countries, Azerbaijan and Sri Lanka, wording in legislation was modified in a way that could allow an earlier age of marriage for girls with parental consent, while Yemen removed any explicit minimum age requirements for marriage.

Within the overall increase in the minimum legal age of marriage with parental consent demonstrated by our longitudinal sample, there were increases in five of six geographic regions. In the Middle East and North Africa the average age increased from 12.7 in 1995 to 15.4 in 2013, while in sub-Saharan Africa it rose from 14.7 to 16.7, in South Asia it increased from 13.9 to 15.1, in Europe and Central Asia it rose from 16.9 to 17.6, and in the Americas the average age changed slightly from 14.2 in 1995 to 14.6 in 2013. In one region, East Asia and the Pacific, the average age remained relatively constant throughout this time period but lowered marginally from 17.2 to 17. The largest increase in the average minimum legal age of marriage for girls with parental consent occurred in the Middle East and North Africa with an increase of 2.7 years, followed by sub-Saharan Africa at 2 years, and South Asia at 1.2 years.

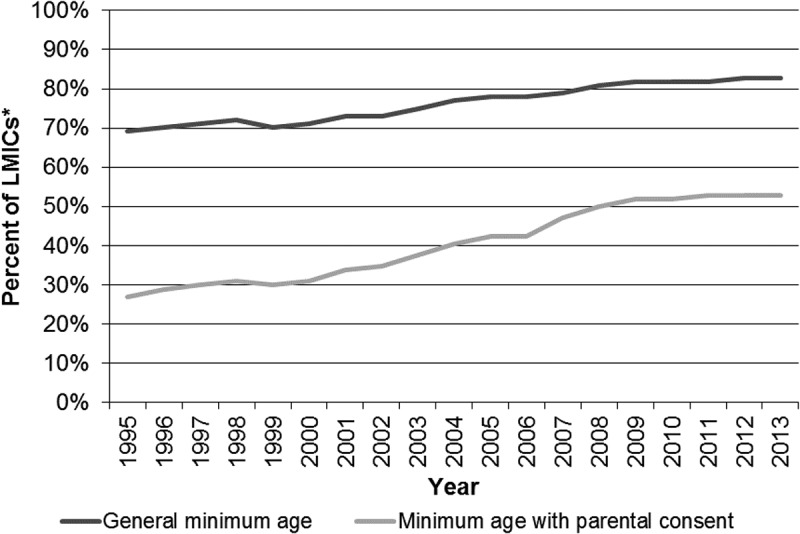

Gender disparities in child marriage laws between 1995–2013

The steady increase in minimum marriage age has been accompanied by a narrowing of the gender gaps in the legislated minimum age, though substantial differences remain (see Figure 7). Between 1995 and 2013 the percentage of countries that prohibited marriage below 18 with parental consent for boys increased 10 percentage points, from 59 percent to 69 percent, while the percentage with the same prohibition for girls rose 24 percentage points, from 20 percent to 43 percent. In 1995 the general minimum marriage age for girls was between one and four years younger than that for boys in 28 percent of the 106 countries in our longitudinal sample; by 2013 this proportion had fallen to 16 percent. The percentage of countries in which the minimum age of marriage with parental consent was lower for girls than boys fell from 66 percent in 1995 to 44 percent in 2013. Further evidence of a narrowing of gender disparities is found in an analysis of the magnitude of the difference in age by gender. The percentage of countries with a difference of three to four years in the minimum age of marriage with parental consent fell from 27 percent in 1995 to 15 percent in 2013, and those with a difference of one to two years fell from 39 percent in 1995 to 29 percent in 2013.

Figure 7.

From 1995 to 2013, how did the percentage of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with no gender disparities in the legal minimum age of marriage change?

Discussion and conclusion

Child marriage is widely recognized within international agreements as a violation of the human rights of children to health, education, equality, non-discrimination, and to live free from violence and exploitation enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). Because of its long-term consequences, child marriage also violates the rights of women who were married as children, with serious implications for their health, income, work, autonomy, and life choices. The CRC and CEDAW Committees recently reiterated recommendations that States Parties amend or adopt laws setting the legal minimum age of marriage at 18.

Despite these conventions, high rates of child marriage in many countries indicate that a range of views regarding definitions of childhood and marriage across countries and communities continue to exist. Moreover, girls are far more likely than boys to be forced into child marriage, reflecting widespread discrimination. The significant and long-term negative consequences for those affected by child marriage result in further solidifying women’s unequal status. A practice that violates girls’ human rights and impedes their full participation in education, the economy, politics, and policymaking has important implications not only for women’s equality but for the broader well-being and development of local, national, and global communities. The adoption of laws establishing a minimum age of marriage of 18 for girls and boys are a first step toward eliminating this harmful practice. On the basis of national legislation, we examined progress toward universal establishment of a legal minimum marriage age of 18 for both girls and boys, the extent to which a range of exceptions permit earlier marriage, and gender disparities in laws, providing important information about what kinds of gaps remain and where.

Analyses reveal widespread gender discriminatory provisions in legislation regulating the minimum age of marriage. Fifty-nine countries around the world currently permit girls to be married at younger ages than boys with parental consent. Laws allowing girls to be married at younger ages than boys reflect a general pattern of gender discrimination and a gendered understanding of the roles and capacities of women. Moreover, these legal frameworks compound, rather than combat, gender disparities in rates of child marriage and the detrimental impacts of this practice on girls. While these gender gaps appear to have narrowed over the past two decades, considerable changes will be required before minimum age of marriage legislation will achieve gender parity.

Though a majority of UN Member States provide girls with legal protections against early marriage through the establishment of the general minimum age of marriage, 23 countries still permit girls to be legally married below the age of 18 without requiring any special permissions or concessions. In these countries there are effectively no national institutional protections that comply with the standards set by international human rights institutions and agreed to by the vast majority of nations. Yet the global picture is substantially worse when considering laws permitting marriage before 18 when parental permission is provided. Just over half of all nations, 99 of 191, have laws that allow a girl to be married before 18 if her parents provide consent. Because child marriages often occur with parental permission and involvement and are in fact often arranged by the parents themselves (Jensen and Thornton 2003), these exceptions may be considered to be a better reflection of the minimum age in practice.

In many countries, national legal provisions for the minimum age of marriage can be superseded by customary and religious laws, which often do not set a minimum age of marriage that complies with global agreements, or any minimum at all. In many religious and ethnic communities these laws provide weaker protections against child marriage for girls (Maswikwa et al. 2015; Odala 2013). Our findings show that girls in 30 countries around the world may not be legally protected from marriage before the age of 18 when exceptions under customary and religious law are considered. Overall, our analyses show that when the legal exceptions of parental permission and parallel customary and religious laws are considered marriage is permitted below 18 in 104 countries worldwide.

Regional patterns in minimum age of marriage legislation vary considerably between different measures, as demonstrated by our findings. Exceptions that permit marriage below 18 with parental consent for girls are highest in the Americas (90 percent), followed by the Middle East and North Africa (53 percent), sub-Saharan Africa (50 percent), and South Asia (38 percent). The proportion of countries in which girls may be married below 18 when exceptions based on customary and/or religious law are considered is highest in the Middle East and North Africa (41 percent), followed by South Asia (33 percent), sub-Saharan Africa (26 percent), and East Asia and the Pacific (23 percent). South Asia was the region with the greatest percentage of countries with gender disparities in minimum age of marriage laws (50 percent), followed by the Americas (41 percent), sub-Saharan Africa (40 percent), and East Asia and the Pacific (38 percent). Longitudinal policy and legal data extending to before the first international agreement on child marriage is needed to enable research that will deepen our understanding of the drivers of regional differences in minimum age of marriage legislation.

Findings on the association between legal measures and economic development were mixed. Higher income countries are more likely to set 18 as the minimum age of marriage when religious and customary law exceptions are allowed, but no such association exists for the legal age of marriage with parental consent or the general legal age of marriage. While an income gradient exists for gender differences of three or four years in the minimum age of marriage, no trend was found in the percentage of countries with no gender differences. There are countries at all income levels that have strong child marriage laws, demonstrating that it has been feasible regardless of income to pass this type of legislation.

Our longitudinal data from 1995 to 2013 indicate that child marriage laws have been passed and strengthened over time. Consistent with the world polity theory on how changes in international institutions and norms influence outcomes and laws at the national and local level (Boli and Thomas 1999), our analysis of the 106 LMICs in our longitudinal sample reveals greater adherence to the international standard of a legislated minimum marriage age of 18 over time. The proportion of countries in our longitudinal sample that permitted girls to marry before 18 with parental consent fell markedly, from 80 percent to 57 percent between 1995 and 2013. During that time period, gender gaps in the legislated minimum age narrowed. For example, the percentage of countries in which the minimum age of marriage with parental consent was lower for girls than boys fell from 66 percent in 1995 to 44 percent in 2013. The percentage of countries with a difference of three to four years in the minimum age of marriage with parental consent fell from 27 percent in 1995 to 15 percent in 2013. Gender differences in the level of legal protections remain, however. Further analysis and longitudinal data are needed to explore the role of international treaties as norm-setting mechanisms and their interplay with national factors in shaping national policy reforms.

Establishing legislation that sets a minimum age of marriage at 18 is recognized in international agreements as an essential component of efforts to eliminate the practice of child marriage. Legislative provisions can encourage government follow-through and provide levers for civil society advocates to hold leaders accountable to national and international commitments (UNICEF 2001). National laws that prohibit the marriage of girls below the internationally accepted standard of 18 could influence public attitudes and political debates. Laws signal to the public and policymakers that the issue is important, and the process of examining legal provisions and updating them where relevant acts as a first step toward broader change (Jensen and Thornton 2003; UNICEF 2001). For these reasons it is equally important that legal exceptions do not create loopholes that undermine protections against child marriage and continue to normalize the practice (Raj 2010).

Moreover, evidence indicating that protective laws may be associated with lower rates of marriage before 18 (Maswikwa et al. 2015) is beginning to emerge. Using DHS data from 12 sub-Saharan African countries from 2010 or later, Maswikwa et al. found a significant association between consistent minimum age laws (the general minimum age of marriage, the minimum age with parental consent, and the age of sexual consent for girls all set at or above 18) and rates of marriage below 18 among female respondents 15–26 years old. Specifically, the prevalence of child marriage was 40 percent lower in countries with consistent laws against child marriage than countries with inconsistent laws (Maswikwa et al. 2015). This study takes an important first step in analyzing the relationship between minimum age of marriage laws and the practice of child marriage. However, detailed longitudinal data on marriage rates among children younger than 18 are needed to determine whether protective laws influence rates of child marriage, taking into consideration broader social, political, economic, and cultural factors.

In calling for protective legislative provisions to combat child marriage, international conventions and reports on child marriage also call for enforcement of those provisions (Loaiza and Wong 2012; Human Rights Watch 2013). Further analysis is needed to better understand the relationship between legal frameworks that set a minimum age of marriage, enforcement and implementation monitoring mechanisms, and rates of early marriage around the world. A combination of qualitative research, case studies, and quantitative longitudinal studies of the social, political, and economic conditions that have influenced changes in laws over time and their impact on the practice of child marriage is crucial.

There is considerable evidence that the practice of child marriage perpetuates gender discrimination and jeopardizes the health and life chances of girls and women around the world. Combined with effective enforcement mechanisms, legal instruments are widely recognized in international agreements as an important tool in reducing the burden of child marriage globally. While progress has been achieved in setting a legislative floor protecting girls under 18 from marriage, considerable gaps remain in establishing laws that achieve gender parity and effectively make marriage below 18 illegal.

Biographies

Megan Arthur is currently a doctoral researcher in social policy within the Global Public Health Unit at the University of Edinburgh. She previously conducted research in global health and global social policy within Global Health Programs, McGill University and at the WORLD Policy Analysis Center, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

Alison Earle is a principal research scientist at the WORLD Policy Analysis Center, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

Amy Raub is a principal research analyst at the WORLD Policy Analysis Center, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

Ilona Vincent is a senior research analyst at the Institute for Health and Social Policy at McGill University. She is responsible for the development and management of a longitudinal database on the state of social policies around the world as well as providing research support to a multinational team of researchers and partners.

Efe Atabay is a research analyst at the Institute for Health and Social Policy at McGill University. He is responsible for the development of a longitudinal database on the state of social policies around the world as well as providing research support to a multinational team of researchers and partners.

Isabel Latz has received a Bachelor of Health Sciences and Health Sciences Research Master at Maastricht University. She is currently a doctoral student in Interdisciplinary Health Sciences at the University of Texas at El Paso.

Gabriella Kranz is program coordinator for the Quebec Population Health Research Network based at the Institute for Health and Social Policy at McGill University.

Arijit Nandi is an associate professor jointly appointed at the Institute for Health and Social Policy and the Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Occupational Health at McGill University. His research, focusing on the impact of public policies on population health, is supported by a Canada Research Chair in the Political Economy of Health.

Jody Heymann is dean of the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and founding director of the WORLD Policy Analysis Center. Heymann is a distinguished professor of health policy and management at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health; distinguished professor of public policy at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs; distinguished professor of medicine at the UCLA Geffen School of Medicine; and honorary professor at the University of Witwatersrand.

Notes

This database can be more fully explored on our website: http://worldpolicycenter.org/topics/marriage/policies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Willetta Waisath for her work in preparing a thorough and comprehensive review of the literature on child marriage and interpersonal violence.

References

- Adedoyin M. A., and Adetoro Olalekan. 1989. “Pregnancy and Its Outcome among Teenage Mothers in Ilorin, Nigeria.” East African Medical Journal 66 (7):448–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akmatov Manas K., Mikolajczyk Rafael T., Labeeb Shokria, Dhaher Enas, and Khan Mobarak. 2008. “Factors Associated with Wife Beating in Egypt: Analysis of Two Surveys (1995 and 2005).” BMC Women’s Health 8 (1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boli John, and Thomas George M.. 1999. Constructing World Culture: International Nongovernmental Organizations since 1875. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark Shelley. 2004. “Early Marriage and HIV Risks in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Studies in Family Planning 35 (3):149–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2004.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Shelley, Bruce Judith, and Dude Annie. 2006. “Protecting Young Women from HIV/AIDS: The Case against Child and Adolescent Marriage.” International Family Planning Perspectives 32 (2):79–88. doi: 10.1363/3207906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and Committee on the Rights of the Child 2014. “Joint General Recommendation/General Comment No. 31 of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women and No. 18 of the Committee on the Rights of the Child on Harmful Practices.” http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/TBSearch.aspx?Lang=en&SymbolNo=CEDAW/C/GC/31/CRC/C/GC/18 (December 19, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- De Silva-De-Alwis Rangita. 2008. Child Marriage and the Law: Legislative Reform Initiative Paper Series. New York: UNICEF Division of Policy and Planning; http://www.unicef.org/policyanalysis/files/Child_Marriage_and_the_Law%281%29.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle Kristin L., Jewkes Rachel K., Brown Heather C., Gray Glenda E., McIntryre James A., and Harlow Siobán D.. 2004. “Gender-Based Violence, Relationship Power, and Risk of HIV Infection in Women Attending Antenatal Clinics in South Africa.” The Lancet 363 (9419):1415–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebigbo Peter O. 2003. “Child Abuse in Africa: Nigeria as Focus.” International Journal of Early Childhood 35 (1):95–113. doi: 10.1007/BF03174436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ertem Melikşah, Saka Günay, Ceylan Ali, Değer Vasfiye, and Sema Çiftçi.. 2008. “The Factors Associated with Adolescent Marriages and Outcomes of Adolescent Pregnancies in Mardin Turkey.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 39 (2):229–39. [Google Scholar]

- Erulkar Annabel. 2013. “Early Marriage, Marital Relations, and Intimate Partner Violence in Ethiopia.” International Perspectives on Sexual & Reproductive Health 39 (1):6–13. doi: 10.1363/3900613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field Erica, and Ambrus Attila. 2008. “Early Marriage, Age of Menarche, and Female Schooling Attainment in Bangladesh.” Journal of Political Economy 166 (5):881–930. doi: 10.1086/593333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney-Rhys Ruth. 2011. “International Law as an Instrument to Combat Child Marriage.” The International Journal of Human Rights 15 (3):359–73. doi: 10.1080/13642980903315398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gage Anastasia J. 2013. “Association of Child Marriage with Suicidal Thoughts and Attempts among Adolescent Girls in Ethiopia.” Journal of Adolescent Health 52:654–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gakidou Emmanuela, Cowling Krycia, Lozano Rafael, and Murray Christopher J.L.. 2010. “Increased Educational Attainment and Its Effect on Child Mortality in 175 Countries between 1970 and 2009: A Systematic Analysis.” The Lancet 376 (9745):959–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn Judith R., Caraël Michel, Auvert Bertran, Kahindo Maina, Chege Jane, Musonda Rosemary, Kaona F., and Anne Buvé.. 2001. “Why Do Young Women Have a Much Higher Prevalence of HIV than Young Men?.” Aids 15 (Supplement 4):S51–S60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godha Deepali, Hotchkiss David R., and Gage Anastasia J.. 2013. “Association between Child Marriage and Reproductive Health Outcomes and Service Utilization: A Multi-Country Study from South Asia.” Journal of Adolescent Health 52 (5):552–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk Noah. 2007. “Uganda: Early Marriage as a Form of Sexual Violence.” Forced Migration Review 27:51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hindin Michelle J., and Fatusi Adesegun O.. 2009. “Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Developing Countries: An Overview of Trends and Interventions.” International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 35 (2):58–62. doi: 10.1363/3505809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindin Michelle J., Kishor Sunita, and Ansara Donna L.. 2008. Intimate Partner Violence among Couples in 10 DHS Countries: Predictors and Health Outcomes (DHS Analytical Studies No. 18). Calverton, MD: Macro International Inc: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AS18/AS18.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Hong Le Minh Thi, Tran Thach D., Nguyen Huong T., and Fisher Jane. 2014. “Early Marriage and Intimate Partner Violence among Adolescents and Young Adults in Viet Nam.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 29 (5):889–910. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch 2011. ‘How Come You Allow Little Girls to Get Married?’ Child Marriage in Yemen. New York: Human Rights Watch; http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/yemen1211ForUpload_0.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch 2013. This Old Man Can Feed Us, You Will Marry Him.’: Child and Forced Marriage in South Sudan. New York: Human Rights Watch: http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/southSudan0313_forinsertWebVersion_0.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Igwebe Anthony O., and Udigwe Gerald Okanandu. 2001. “Teenage Pregnancy: Still an Obstetric Risk.” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 21 (5):478–81. doi: 10.1080/01443610120072027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain Saranga, and Kurz Kathleen. 2007. New Insights on Preventing Child Marriage: A Global Analysis of Factors and Programs. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women; https://www.icrw.org/files/publications/New-Insights-on-Preventing-Child-Marriage.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Jensen Robert, and Thornton Rebecca. 2003. “Early Female Marriage in the Developing World.” Gender and Development 11 (2):9–19. doi: 10.1080/741954311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Minzee, Longhofer Wesley, Boyle Elizabeth Heger, and Brehm Hollie Nyseth. 2013. “When Do Laws Matter? National Minimum-Age-of-Marriage Laws, Child Rights, and Adolescent Fertility, 1989–2007.” Law & Society Review 47 (3):589–619. doi: 10.1111/lasr.12033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishor Sunita, and Johnson Kiersten. 2004. Profiling Domestic Violence: A Multi-Country Study. Calverton, MD: Measure DHS+ www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/OD31/OD31.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Kumbi Solomon, and Isehak Abdulhamid. 1999. “Obstetric Outcome of Teenage Pregnancy in Northwestern Ethiopia.” East African Medical Journal 76 (3):138–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd Cynthia B., and Mensch Barbara S.. 2008. “Marriage and Childbirth as Factors in Dropping Out of School: An Analysis of DHS Data from Sub-Saharan Africa.” Population Studies 62 (1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/00324720701810840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loaiza Edilberto, and Wong Sylvia. 2012. Marrying Too Young: End Child Marriage. New York: United Nations Population Fund: http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/MarryingTooYoung.pdf (June 5, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Maswikwa Belinda, Richter Linda, Kaufman Jay, and Nandi Arijit. 2015. “Minimum Marriage Age Laws and the Prevalence of Child Marriage and Adolescent Birth: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa.” International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 41 (2):58–68. doi: 10.1363/4105815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur Sanyukta, Greene Margaret, and Malhotra Anju. 2003. Too Young to Wed: The Lives, Rights, and Health of Young Married Girls. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women: http://www.icrw.org/sites/default/files/publications/Too-Young-to-Wed-the-Lives-Rights-and-Health-of-Young-Married-Girls.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Melah G. S., Massa A. A., Yahaya U. R., Bukar M., Kizaya D. D., and El-Nafaty A. U.. 2007. “Risk Factors for Obstetric Fistulae in North-Eastern Nigeria.” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 27 (8):819–23. doi: 10.1080/01443610701709825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchiorre Angela. 2004. “At What Age?” In Right to Education Project. 2nd ed., London. http://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/RTE_IBE_UNESCO_At%20What%20Age_Report_2004.pdf (January 16, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Mensch Barbara S. 2005. “The Transition to Marriage” In Growing up Global: The Changing Transitions to Adulthood in Developing Countries, ed. Lloyd Cynthia B. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 416–505. [Google Scholar]

- Muleta Mulu, and Williams Gordon. 1999. “Postcoital Injuries Treated at the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital.” The Lancet 354 (9195):2051–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy Elaine, and Carr Dara. 2007. Powerful Partners: Adolescent Girlsʼ Education and Delayed Childbearing. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau: http://www.prb.org/pdf07/powerfulpartners.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Nour Nawal M. 2006. “Health Consequences of Child Marriage in Africa.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 12 (11):1644–49. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nour Nawal M. 2009. “Child Marriage: A Silent Health and Human Rights Issue.” Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology 197 (1):51–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nove Andrew, Matthews Zoe, Neal Sarah, and Camacho Alma Virginia. 2014. “Maternal Mortality in Adolescents Compared with Women of Other Ages: Evidence from 144 Countries.” The Lancet Global Health 2 (3):e155–e164. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn Andrew J., Kengeya-Kayondo Jane F., Malamba Sam S., Seeley Janet A., and Mulder Daan W.. 1994. “Risk Factors for HIV-1 Infection in Adults in A Rural Ugandan Community: A Population Study.” Aids 8 (1):81–86. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odala Violet. 2013. “How Important Is Minimum Age of Marriage Legislation to End Child Marriage in Africa?” http://www.girlsnotbrides.org/how-important-is-minimum-age-of-marriage-legislation-to-end-child-marriage-in-africa/ (August 21, 2014).

- Onolemhemhen Durrenda Ojanuga, and Ekwempu C. C.. 1999. “An Investigation of Sociomedical Risk Factors Associated with Vaginal Fistula in Northern Nigeria.” Women and Health 28 (3):103–16. doi: 10.1300/J013v28n03_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouis Pernilla. 2009. “Honourable Traditions? Honour Violence, Early Marriage and Sexual Abuse of Teenage Girls in Lebanon, the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Yemen.” International Journal of Children’s Rights 17 (3):445–74. doi: 10.1163/157181808X389911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Mosfequr Md., Hoque Md Aminul., Mostofa Golam, and Makinoda Satoru. 2014. “Association between Adolescent Marriage and Intimate Partner Violence: A Study of Young Adult Women in Bangladesh.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health 26 (2):160–68. doi: 10.1177/1010539511423301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj Anita. 2010. “When the Mother Is a Child: The Impact of Child Marriage on the Health and Human Rights of Girls.” Archives of Disease in Childhood 95 (11):931–35. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.178707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj Anita, Gomez Charlemagne, and Silverman Jay G.. 2008. “Driven to a Fiery Death: The Tragedy of Self-Immolation in Afghanistan.” New England Journal of Medicine 358 (21):2201–03. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0801340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj Anita, Saggurti Niranjan, Balaiah Donta, and Silverman Jay G.. 2009. “Prevalence of Child Marriage and Its Effect on Fertility and Fertility Control Outcomes of Young Women in India: A Cross-Sectional, Observational Study.” The Lancet 373 (9678):1883–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhya Kidangamparampil G., Ram Usha, Acharya Rajib, Jejeebhoy Shireen J., Ram Faujdar, and Singh Abhishek. 2010. “Associations between Early Marriage and Young Women’s Marital and Reproductive Health Outcomes: Evidence from India.” International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 36 (3):132–39. doi: 10.1363/3613210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitridina Rini. 1997. “Determinants and Consequences of Early Marriage in Java, Indonesia.” Asia-Pacific Population Journal 12 (2):25–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhri Sheetal, and Debnath Sisir. 2014. “Intergenerational Consequences of Early Age Marriages of Girls: Effect on Children’s Human Capital.” The Journal of Development Studies 50 (12):1670–86. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2014.936397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma Vandana, Katz Joanne, Mullany Luke C., Khatry Subarna K., LeClerq Steven C., Shrestha Sharada R., Darmstadt Gary L., and Tielsch James M.. 2008. “Young Maternal Age and the Risk of Neonatal Mortality in Rural Nepal.” Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 162 (9):828–35. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.9.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawky Sherine, and Milaat Waleed. 2001. “Cumulative Impact of Early Maternal Marital Age during the Childbearing Period.” Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 15 (1):27–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Susheela, and Samara Renee. 1996. “Early Marriage among Women in Developing Countries.” International Family Planning Perspectives 22 (4):148–57. doi: 10.2307/2950812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Speizer Ilene S., and Pearson Erin. 2011. “Association between Early Marriage and Intimate Partner Violence in India: A Focus on Youth from Bihar and Rajasthan.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 26 (10):1963–81. doi: 10.1177/0886260510372947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF 2001. Early Marriage: Child Spouses. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre: http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/digest7e.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF 2005. Early Marriage: A Harmful Traditional Practice. New York: UNICEF: http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Early_Marriage_12.lo.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF 2014. Ending Child Marriage: Progress and Prospects. New York: UNICEF Division of Policy and Research: http://www.unicef.org/media/files/Child_Marriage_Report_7_17_LR.pdf (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein Rachel B. 2013. Ending Child Marriage. New York: Council on Foreign Relations: http://www.cfr.org/children/ending-child-marriage/p30734 (December 1, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Walker Judith-Ann. 2012. “Early Marriage in Africa: Trends, Harmful Effects and Interventions.” African Journal of Reproductive Health 16 (2):231–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank 2013. “Country Classification: A Short History.” http://go.worldbank.org/U9BK7IA1J0/ (November 21, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zabin Laurie Schwab, and Kiragu Karungari. 1998. “The Health Consequences of Adolescent Sexual and Fertility Behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Studies in Family Planning 29 (2):210–33. doi: 10.2307/172160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]