Abstract

Chronic pain is associated with maladaptive reorganization of the central nervous system. Recent studies have suggested that disorganization of large-scale electrical brain activity patterns such as neuronal network oscillations in the thalamo-cortical system plays a key role in the pathophysiology of chronic pain. Yet, little is known about if and how such network pathologies can be targeted with non-invasive brain stimulation as a non-pharmacological treatment option. We hypothesized that alpha oscillations, a prominent thalamo-cortical activity pattern in the human brain, are impaired in chronic pain and can be modulated with transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS). We performed a randomized, crossover, double-blind, sham-controlled study in patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) to investigate how alpha oscillations relate to pain symptoms for target identification and if tACS can engage this target and thereby induce pain relief. We used high-density electroencephalography to measure alpha oscillations and found that the oscillation strength in the somatosensory region at baseline before stimulation was negatively correlated with pain symptoms. Stimulation with alpha-tACS compared to sham (placebo) stimulation significantly enhanced alpha oscillations in the somatosensory region. The stimulation-induced increase of alpha oscillations in the somatosensory region was correlated with pain relief. Given these findings of successful target identification and engagement, we propose that modulating alpha oscillations with tACS may represent a target-specific, non-pharmacological treatment approach for CLBP. This trial has been registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03243084).

Keywords: chronic low back pain, electroencephalography, alpha oscillations, transcranial alternating current stimulation

Perspective

This study suggests that a rational design of transcranial alternating current stimulation, which is target identification, engagement, and validation, could be a non-pharmacological treatment approach for patients with chronic low back pain.

Introduction

Chronic pain is associated with pathological changes in neuronal activity over somatosensory, insular, cingulate, and prefrontal cortices46. These brain regions play a fundamental role in the processing of pain32,51,57. Several electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies have shown that patients with chronic pain exhibit abnormal neuronal oscillations43,55. In particular, pathologically increased theta oscillations (4–8Hz)34,48,49,53,58 have motivated a conceptual framework of thalamo-cortical dysrhythmia (TCD) in chronic pain33,34. Moreover, the peak frequency of neuronal oscillations measured by EEG and MEG appears lower in patients with chronic pain when compared to healthy control participants48,49,53,56,58. Thus, these findings imply that identifying the relationship between neurophysiological changes and pain severity and engaging the identified target could represent a network-level approach to understand a causal role of chronic pain. Yet, little is known about if and how such network pathologies can be modulated with targeted non-invasive brain stimulation in patients with chronic pain.

Here, we performed a randomized, crossover, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial to investigate how non-invasive brain stimulation can target neuronal oscillations in patients with chronic pain. We chose to investigate target identification and engagement of neuronal oscillations in a sample of patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP), which is the single leading cause of disability worldwide22. We built a model of bifrontal montage to target and modulate the bilateral somatosensory cortex in patients with CLBP since previous studies have shown that abnormal neuronal oscillations in the somatosensory cortex reflect pain perception13,20,45,46,60. In addition, previous brain stimulation approaches such as deep brain stimulation and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) successfully reduced pain severity6,31,47. Inspired by these successful approaches and the fundamental role of somatosensory cortex in pain, we built a model bifrontal montage to target the somatosensory cortex.

We formulated two hypotheses in our study. First, patients with CBP exhibit impaired alpha oscillations. This hypothesis is based on previous findings that pain perception suppresses alpha oscillations23,24,45 and the suppression is correlated with pain severity7,9,25,40,52. Second, transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), which is a non-invasive brain stimulation tool that can modulate neuronal oscillations by applying oscillating electrical currents21,54, can enhance alpha oscillations in the somatosensory cortex and thereby induce pain relief. We recorded alpha oscillations by high-density EEG to investigate the hypothesized association of alpha oscillations with pain severity in patients with CLBP and applied 10Hz-tACS based on the identified target region. We assessed two rating scales for pain severity and perceived disability due to chronic low back pain. We found that alpha oscillations in the somatosensory region were negatively correlated with pain severity. Furthermore, 10Hz-tACS applied in the somatosensory region enhanced alpha oscillations and the enhancement correlated with pain relief. Our findings of successful target identification and engagement with tACS suggests that applying non-invasive brain stimulation to modulate neuronal oscillations may be a non-pharmacological tool to treat CLBP.

Methods

Participants

Both male and female participants (age 18 to 65) were recruited from local pain and physical therapy clinics in Chapel Hill, NC area. Inclusion criteria consisted of a diagnosis of chronic back pain by a licensed clinician, pain severity ≥3 on a 0–10 numerical pain rating scale11, and duration of chronic low back pain for at least five months. (Table 1). All participants signed a consent form. Eligibility of participants was determined by a telephone screening before the first session. Twenty participants participated in two sessions (10Hz-tACS and sham) separated by 1–3 weeks and intervention sequence was randomized and balanced across all participants. Randomization was performed using sequentially numbered assignment. One of the authors (J.H.P) generated the random allocation sequence, enrolled all participants, and assigned the participants to the sequence.

Table 1.

Demographic information. DVPRS: Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale, ODI: Oswestry Disability Index. Data reported as mean±std.

| Participants (n=20) | |

|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 8/12 |

| BMI | 25.9±4.3 |

| Duration of chronic back pain (months) | 84.8±70 |

| DVPRS (baseline) | 4.4±1.0 |

| ODI (baseline) | 22.7±11.2 |

| Race (Caucasian/African Caucasian) | 18/2 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic/Not Hispanic) | 1/19 |

| Education level | |

| Bachelor’s degree or less | 12 |

| Master’s degree | 6 |

| Doctorate degree | 2 |

Study design

We performed a randomized, crossover, double-blind, sham-controlled, clinical trial with two stimulation conditions (10Hz-tACS and sham). The study was performed at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03243084) and approved by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Behavioral questionnaires were administered before and after the stimulation at each session. All participants completed the Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS)8 and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)18 to assess the severity of chronic low back pain and perceived disability, respectively. The DVPRS comprises a validated numerical rating pain scale (0 to10) with detailed verbal descriptions and facial expressions. We used the back pain specific ODI, which consists of ten questions pertaining to perception of disability in daily life activities. Although participants completed both self-report measures at the beginning of each session by phone, participants only completed the DVPRS after stimulation. Since the ODI encompasses questions about daily living, the follow-up was taken two days after each session for a more valid measure of any disability change. EEG data were recorded from participants with their eyes closed for two minutes before the stimulation and with their eyes open before and after the stimulation for two minutes. EEG signals were recorded using a 128-channel Geodesic EEG system (EGI Inc., Eugene, OR) at a sampling rate of 1kHz. Electrode Cz and one electrode between Cz and Pz were used as the reference and as the ground, respectively. Instructions for the tasks were implemented in Presentation (Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc., Berkeley, CA). Participants were instructed by a computer voice to fixate on a crosshair and open their eyes while staying relaxed for the eyes-open condition. Here we report on the primary and secondary outcome with regards to modulation of alpha oscillations and associated changes in pain symptoms. Results on heart rate variability will be reported elsewhere. The sample size was determined by the amount of funding available for the grant that supported this work. The study was performed between September and November 2017. The trial was ended when the target of 20 participant receiving stimulation was reached. The study protocol will be made available in response to written request to the corresponding author (F.F.)

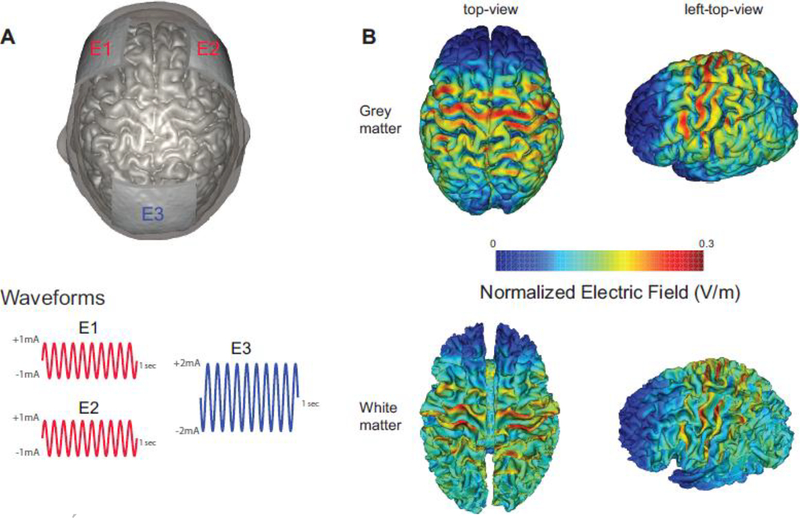

Transcranial alternating current stimulation

We applied three carbon-silicone electrodes to the scalp with Ten20 conductive paste (Bio-Medical Instruments, Clinton Township, MI) and used the XCSITE 100 stimulator (Pulvinar Neuro LLC, Chapel Hill, NC) to administer tACS. Five-digit codes were used to ensure blinding of the study coordinators with regards to the stimulation conditions. The XCSITE 100 device does not display any information that would provide insights into whether verum or sham stimulation is applied. Two of the three electrodes (5×5cm each) were placed at F3 and F4 according to 10–20 international coordinate system and these two electrodes were connected together for 10Hz-tACS. The other electrode (5×7cm) was placed at Pz as a “return” electrode. Stimulation montage and modeling of electric field distribution were calculated with the tES LAB 1.0 software (Neurophet Inc., Seoul, South Korea) as depicted in Figure 1. In this software, we used a T1-weighted MRI (adult male) from the human connectome project14. The MRI data were segmented by 8 tissues (cerebrum gray matter, cerebrum white matter, cerebellar gray matter, cerebellar white matter, ventricels, CSF, skull and skin) and each tissue was assigned isotropic conductivity values29. To obtain electric field distributions, we used the finite element method with tetrahedron volume meshes. The number of tetrahedron mesh was about 4.3 million and the quasi-static Maxwell’s equation was used. The two electrodes placed at the frontal lobe delivered an in-phase sinusoidal waveform with 1mA amplitude each (zero-to-peak). Stimulation duration was 40 minutes for both conditions. Verum stimulation delivered 40 minutes of 10Hz-tACS with 10 seconds of ramp-up and ramp down. Sham stimulation delivered 10 seconds of ramp-up, followed by 60 seconds of 10Hz-tACS, followed by 10 seconds of ramp-down for a total of 80 seconds. The choice of such an “active sham” is an established strategy to enhance blinding of the participants to the stimulation condition. To ensure blinding, participants were asked to fill out a questionnaire how sure they were of receiving stimulation on a visual analog scale (0–100) after each stimulation session. We found no significant difference of the visual analogue scale between the two stimulation conditions (p=0.1555, Wilcoxon signed rank test, supplementary Fig 1). All participants completed the 10Hz-tACS and sham stimulation. On average, the stimulation sessions were spaced by 14.4±6.5 days. During the stimulation, all participants were seated comfortably and watched Reefscapes (Undersea Productions, Queensland, Australia) that displays tropical fish underwater scenes to minimize the phosphenes induced by stimulation. Participants were asked to stay relaxed, watch the video, and keep their eyes open.

Figure 1.

Stimulation montage, waveforms, and distributions of electric field in the brain. (A) Electrodes E1 and E2 delivered in-phase 10Hz-tACS with 1mA amplitude (zero-to-peak). Electrode E3 was used as the return electrode. (B) Normalized electric field distribution (V/m) by bifrontal 10Hz-tACS (top-view and left-top-view) in grey and white matter.

EEG analysis and statistical testing

Offline processing was performed by EEGLAB12, FieldTrip42, and custom-built scripts in MATLAB. First, all data were downsampled to 250Hz with anti-aliasing filtering and band-pass filtered from 1 to 50Hz. Second, the data were preprocessed by an artifact subspace reconstruction algorithm39 to remove high-variance and reconstruct missing data. Briefly, the algorithm first finds a minute of data that represents clean EEG as a baseline. Then, principle component analysis is applied to the whole data set with a sliding window to find the subspaces in which there is activity that is more than five standard deviations away from the baseline EEG. Once the function has identified the outlier subspaces, it treats them as missing data and reconstructs their content using a mixing matrix that is calculated from the clean data. Third, bad channels that were found in the previous step were interpolated and common average referencing was performed. Fourth and lastly, infomax independent component analysis (ICA)26 was performed to remove eye blinking, eye movement, muscle activity, heartbeats, and channel noise. All ICA components were visually inspected and components were manually selected for rejection. These initial pre-processing steps were carried out on the full EEG dataset before unblinding of the study.

Resting-state EEG data were epoched into 2-second windows. Each epoch was visually inspected in the temporal domain and bad epochs that contained abnormal spikes or high-frequency noise were removed. Power spectral density (PSD) was computed by Welch’s method with a 2-sec window and a 12.5% overlap resulting in a PSD with 0.5Hz frequency bins. Individual alpha frequency (IAF), which we defined as the frequency of peak power in the occipital alpha (8–12Hz) from eyes-closed EEG data, was selected for each participant. The power of the alpha oscillations was obtained by averaging of the PSD around the IAF (IAF − 1Hz ≤ IAF ≤ IAF + 1Hz) and the alpha oscillations were normalized by the average of all electrodes to minimize the inter-subject variability of alpha oscillations1,2. Thirty-eight electrodes outside of the scalp were excluded and the remaining 90 electrodes inside of the scalp were used for topographical representation.

For statistical testing, we used a linear mixed model analysis with fixed factors of “condition” (tACS and sham), “session” (session1, session2), and “sequence” (tACS-sham, sham-tACS), with random factor “participant” written in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). We assumed that no carry-over effect was observed since there were sufficient washout period between the two sessions and outlasting treatment effects of stimulation are negligible. Kenward-Roger approximations were used to perform F-tests for each factor and interaction and obtain p-values. Post-hoc statistical tests were performed using student’s t-test across participants at each electrode and it was corrected by false discovery rate (FDR)5. Changes of measured values over sessions were quantified with a modulation index (MI),

| (1) |

Changes in spatially-normalized alpha oscillations were calculated by (Alphabefore, Alphabefore). In contrast, changes in DVPRS and ODI were calculated by (DVPRSbefore, DVPRSafter) and (ODIbefore, ODIafter), respectively. Given the non-normal distribution of the modulation indices for the assessments, we also performed exploratory analysis using the Wilcoxon sign-rank test.

Results

Pain assessments and endogenous alpha oscillations

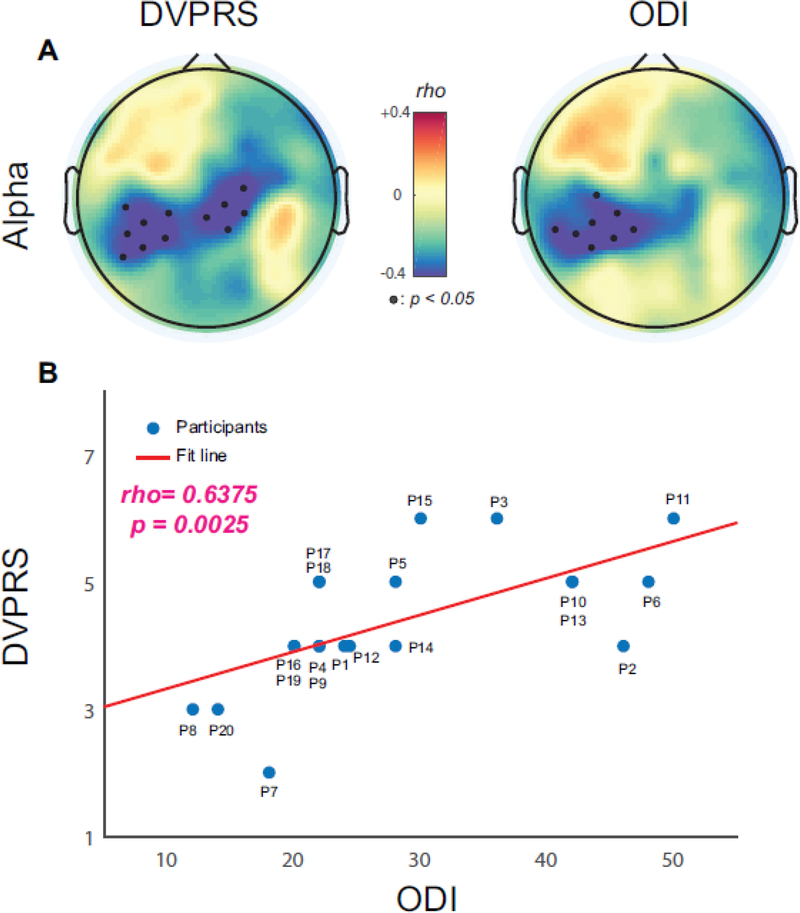

We first examined how endogenous alpha oscillations were correlated with CBP severity measured by the DVPRS and ODI, i.e., target identification. Baseline spatially-normalized alpha oscillations were calculated from 2-minute eyes-open data at the first study session regardless of the stimulation condition for that session. We calculated the Spearman’s rho between the baseline alpha oscillations and the assessments across all participants at each scalp EEG channel. We found significant negative correlations over the bilateral and left somatosensory region for the DVPRS and ODI, respectively (Fig. 2A). The black dots represent EEG channels with statistically significant correlations (p<0.05, FDR corrected). Negative correlations indicate endogenous alpha oscillations were lower for patients with higher pain severity (DVPRS) and higher perceived disability (ODI). Given the similarity in the topographic distribution of these correlations, we confirmed that the DVPRS and ODI scores were positively correlated (r=0.6375, p=0.0025, Fig. 2B). These results suggest that reduced endogenous alpha oscillations could represent the severity of CBP and its impact on the perceived disability.

Figure 2.

Correlations between baseline alpha oscillations and clinical assessments (DVPRS and ODI). (A) Topographical distribution for DVPRS and ODI. Small black dots represent EEG channels with statistical significance (p<0.05, FDR corrected). (B) Scatter plot for correlated ODI and DVPRS (rho=0.6375, p=0.0025).

Enhanced alpha oscillations by 10Hz-tACS

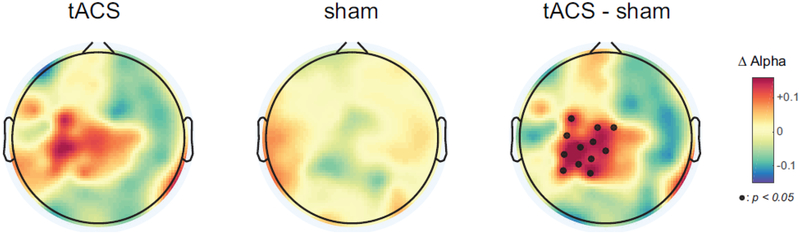

Our finding that a reduction in alpha oscillations is associated with pain severity in CBP suggests that tACS could restore these pathological reduced oscillations. Thus, we next examined modulation, i.e., target engagement, of endogenous alpha oscillations by 40 minutes of bifrontal 10Hz-tACS and sham stimulation. Changes in spatially-normalized alpha oscillations from eyes-open data for 2 minutes were obtained immediately before and after stimulation for conditions. The increase in alpha oscillations was significantly higher in the 10Hz-tACS condition (Fig.3, left) compared to the sham condition (Fig. 3, middle, F1,18=6.5, p=0.02). The black dots in the topographic map (Fig. 3, right) represent the location of EEG channels with statistically significant differences in modulation of alpha oscillation between 10Hz-tACS and sham, (p<0.05, FDR corrected). These results suggest that 10Hz-tACS selectively enhanced endogenous alpha oscillations over the somatosensory region in patients with CBP.

Figure 3.

Averaged topographical distribution of changes in spatially-normalized alpha oscillations for tACS (left), sham (middle), and the difference (right). Individual alpha frequency was used (IAF±1Hz) and small black dots represent EEG channels with statistical significance (p<0.05, FDR corrected).

Changes in pain assessments and alpha oscillations

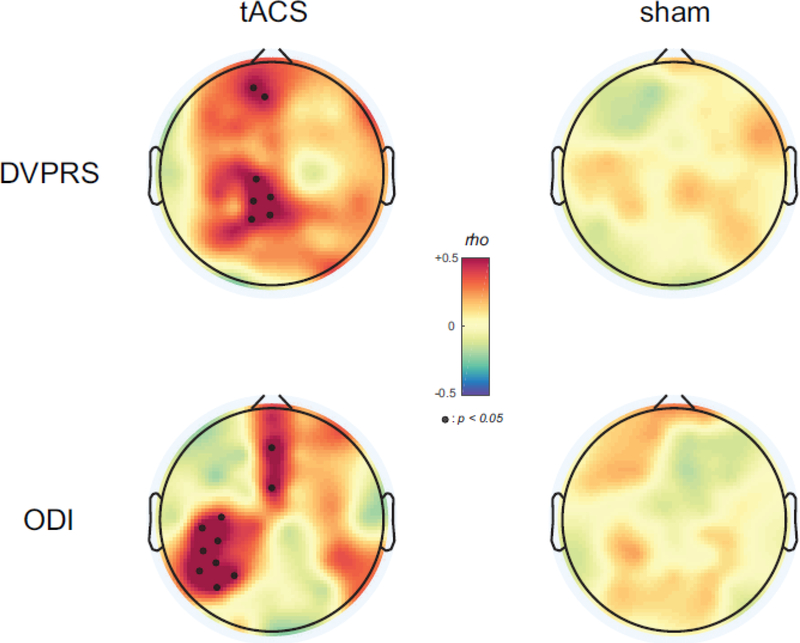

Given the correlation between a reduction of alpha oscillations and pain severity, we next asked if the stimulation-induced changes in alpha oscillations modulated pain severity. We examined how enhanced alpha oscillations by 10Hz-tACS were correlated with changes in pain severity. We calculated the Spearman’s rho between changes in spatially-normalized alpha oscillations, (Alphaafter, Alphabefore), and the two assessments (DVPRSbefore, DVPRSafter), MI(ODIbefore, ODIafter) for each stimulation condition at each EEG channel. We found significant positive correlations over the somatosensory and frontal regions for the DVPRS in the 10Hz-tACS condition (Fig. 4, top row). The black dots in the topographic map represent statistically significant EEG channels (p<0.05, FDR corrected). In contrast, no significant correlations were obtained in the sham condition for the DVRPS. Similarly, for the ODI, we found significant positive correlations over the left somatosensory and frontal regions (p<0.05, FDR corrected) in the 10Hz-tACS condition and no significant correlations in the sham condition. Thus, increasing alpha oscillations improved pain severity and perceived disability, which suggests a causal of pathological reduced alpha oscillations in chronic pain.

Figure 4.

Topographical distribution of correlations between enhanced alpha oscillations and pain symptom changes. Small black dot represent EEG channels with statistical significance (p<0.05, FDR corrected).

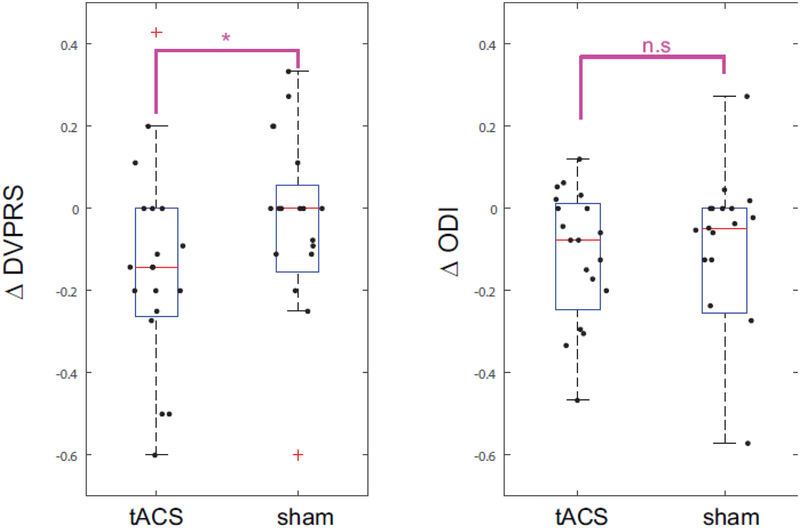

Clinical improvement of chronic low back pain

As secondary outcome, we determined the improved in the DVPRS and ODI scores independent of the neurophysiological changes. We calculated changes of the two assessments (DVPRS and ODI) by using the modulation indices MI (DVPRSbefore, DVPRSafter) and MI (ODIbefore, ODIafter) across the stimulation conditions. Statistical testing with a linear mixed model and Kenward-Roger approximations revealed no significant effect for the simulation conditions, (F1,18=1.13, p=0.3). However, the DVPRS and ODI data were not normally distributed as determined by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for the null hypothesis that the data comes from a standard normal distribution (p=0.005). We thus performed exploratory analysis with the Wilcoxon sign-rank test, a non-parametric test for non-normally distributed data. We found a significant effect only for change in DVPRS (p=0.0488, Fig. 5A) and not or change in ODI (p=0.17, Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Changes in pain assessments (DVPRS and ODI) under stimulation conditions (tACS and sham). Statistical significance was assessed with the non-parametric Wilcoxon sign-rank test (*: p<0.05). Red symbol indicates an outlier.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that patients with chronic pain exhibit abnormal neuronal oscillations46. In particular, alpha oscillations have been hypothesized to be involved in chronic pain9,25,45,52. Yet, to our knowledge we are the first to examine if non-invasive brain stimulation can enhance alpha oscillations and thereby improve symptoms of chronic pain. We performed a randomized, crossover, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial to examine the association between endogenous alpha oscillations and pain severity in patients with CLBP and the modulation of alpha oscillations by 10Hz-tACS. We found that endogenous alpha oscillations in the somatosensory region were negatively correlated with pain severity assessed by the assessments for back pain (DVRPS) and perceived disability due to back pain (ODI). Bifrontral 10Hz-tACS targeting the somatosensory region successfully enhanced alpha oscillations compared to sham stimulation. Further, we found that changes of pain relief were correlated with changes of endogenous alpha oscillations in the frontal and somatosensory regions. Our findings of successful target identification and engagement of alpha oscillations by 10Hz-tACS for patients with CBP demonstrates the potential of tACS for treating pain by modulating neuronal oscillations.

TCD has been proposed as a framework for understanding underlying mechanisms of chronic neurogenic pain34. According to the framework, increased theta oscillations and slowing a dominant peak were consistently observed in previous studies48,49,53,56. A decreased inhibition of the thalamus seems to be linked to increased theta oscillations in patients with chronic neurogenic pain. However, a study failed to replicate these findings in patients with CLBP50. In this study, they recruited patients with CLBP (duration of illness at least 1 year) and compared with age- and gender-matched healthy participants. The authors did not find any significant difference in terms of increased theta oscillations and peak shift to lower frequency and concluded that different pain location may have caused the discrepancy. Interestingly, none of the patients with chronic neurogenic pain suffered from low back pain in previous studies for testing the TCD hypothesis48,49,53,56. In contrast, our study focused on the strength of the alpha oscillation motivated by the inverse correlation between neuronal activity and alpha oscillation power. We hypothesized that alpha oscillations are reduced in CLBP due to disinhibition associated with pathologically increased cortical excitation in chronic pain62, which indicates dysfunction of inhibitory neurotransmitters61. Testing the TCD was not a goal of this study and thus a direct comparison of the results is not possible. Instead, our findings may represent fundamental neurophysiological correlate of pain symptoms in patients with CLBP. In the view of translation to a population with neuropathic pain using our approach, theta oscillations may be targeted by theta-tACS. However, identifying the relationship between theta oscillations and pain intensity should be performed first to target and modulate abnormal theta oscillations. Once the relationship is consistent across patients with neuropathic pain, detailed spatial targeting can be applied based on the identified target region.

Inspired by a previous study19, which found the relationship between peak alpha frequency and pain sensitivity, we investigated this relationship in our data. We found no significant correlation between peak alpha frequency and the two pain assessments (DVRPS and ODI) at baseline (Supplementary Fig. 2). This discrepancy may come from a different population of participants since our study population is patients with chronic low back pain. In addition, patients with long-term chronic pain exhibit some degree of depression as a comorbidity15 thus we assessed Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) from all participants to investigate a relationship pain severity and depression level. We found no significant correlation between HAM-D scores and the two pain assessments (DVPRS and ODI) at baseline (Supplementary Fig 3). We only assessed HAM-D at baseline since tracking depression level was not a goal of this study. This relationship needs to be investigated further in a larger sample with multiple assessments.

Deep brain stimulation that stimulates periventricular/periaqueductal gray matter, internal capsule, and sensory thalamus has shown promising improvement of pain relief6,47. Due to substantial risks of surgical implantation of electrodes in the brain, non-invasive brain stimulation techniques including rTMS have been investigated for the treatment chronic pain28,31,44. Similar to our study, these studies considered chronic pain as a disorder associated with reorganization of the central nervous system17. The first rTMS study showed that 10Hz-rTMS for 20 minutes applied to the motor cortex decreased pain severity in a sham-controlled clinical trial30. In a follow- area also reduced pain compared to 20Hz-rTMS and sham16. Although these rTMS studies showed a substantial reduction in pain, several similar studies failed to replicate these findings. One study with 20Hz-rTMS found no significant differences between real and sham groups28 and another double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial with 1Hz- and 20Hz-rTMS found no significant treatment effects compared to sham stimulation3. Recent meta-analysis showed that rTMS for treating pain does not achieve the minimum clinically important difference threshold of 15% or greater41. In addition to rTMS, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) has also been investigated. A recent meta-analysis found similar heterogeneity of outcomes as for the tDCS studies41.

It is of note that alpha oscillations have been investigated in depth in the context of pain stimuli in healthy control participants. Most of these studies have provided evidence for pain perception in presence of suppression of alpha oscillations for phasic pain23,36,38,45. Likewise, longer-lasting tonic pain, which may represent a precursor to chronic pain, suppressed alpha oscillations13,24,40,52. In addition, pain severity and alpha oscillations were negatively correlated40,52. These studies are correlational in nature but a recent tACS study with behavioral outcome measures provided the first evidence for a causal role of alpha oscillation in pain processing4 albeit no confirmatory neurophysiological measurements were performed. Our study differed in scope and question since we examined target engagement of tACS by EEG and examined the causal role of alpha oscillations in the context of chronic pain. Such a target-specific approach with EEG may provide a new insight to understand mechanisms of chronic pain.

As any scientific study, our study has several limitations. First, we found a significant reduction for DVRPS only on exploratory analysis and none for ODI. One possible reason for this is that post-stimulation ODI was measured two days after each session since we hypothesized that a single session of tACS may not change disability. It is of note that our study was designed as a target engagement study with physiological changes including the alpha oscillation as primary outcome rather than treating chronic pain by a single session of tACS. The study was not designed or powered to detect meaningful clinical difference. Importantly, a treatment protocol would consist of repeated application of 10Hz-tACS as in our recent treatment clinical trial for auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia37. In a follow-up study, we plan to investigate the treatment effect with lager sample size and more refined target engagement strategies such as individual alpha frequency27,54,59. Second, even though brain stimulation approaches have been used widely to modulate cortical excitability and treat patients, inter- and intra-individual variability for effects still exist10,35. Individualizing stimulation parameters with precise modeling of electric current density may be one approach to minimize variability. In our study, likewise, we fixed stimulation intensity and montage across all participants without individualization. In a follow-up study, individualization of stimulation parameters should be considered as well as multi-session stimulation.

In summary, we report on the first study of target identification and engagement with high-density EEG and tACS for patients with CLBP. Our findings suggest a causal role of alpha oscillations in CLBP. Targeting and modulating neuronal oscillations represents a promising strategy to understand the interaction between pain symptoms and brain oscillations. Potentially, such a target-specific approach to modulate pathologically impaired oscillations with tACS may provide therapeutic benefit for other disorders associated with brain network pathologies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Sureness of stimulation measured by a visual analog scale (0–100) between the two stimulation conditions. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used (p=0.0155, paired test).

Supplementary Figure 2. Scatter plots for correlations between peak alpha frequency and pain assessments (DVPRS and ODI). No significant correlation was found in both pain assessments (rho=−0.2085, p=0.3777 for DVRPS, rho=−0.2821, p=0.2281 for ODI).

Supplementary Figure 3. Scatter plots for correlations between Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and pain assessments (DVPRS and ODI). No significant correlation was found in both pain assessments (rho=−0.1547, p=0.5149 for DVRPS, rho=0.0347, p=0.8845 for ODI).

Highlights.

Target identification of alpha oscillations by EEG in chronic low back pain.

Target engagement of alpha oscillations by 10Hz-tACS.

Target validation of enhanced alpha oscillations linked to clinical improvement.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01MH111889 and R01MH101547, North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute under Award Number NC TraCS 2KR941707 and Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). We gratefully acknowledge the help and support from the Carolina Center for Neurostimulation. The authors specially thank Donghyeon Kim (Neurophet Inc.,) for providing valuable feedback on our stimulation montage and modeling of electric field distribution. S.A., J.H.P, M.L.A, and K.L.M. have no financial conflicts. F.F. is the lead inventor of IP filed by UNC. The clinical studies performed in the Frohlich Lab have received a designation as conflict of interest with administrative considerations. F.F. is the founder, CSO and majority owner of Pulvinar Neuro LLC, a company that markets research tDCS and tACS devices. F.F. has received research funding from the National Institute of Health, the Brain Behavior Foundation, the Foundation of Hope, the Human Frontier Science Program, Tal Medical, and individual donations. F.F. is an adjunct professor in Neurology at the Insel Hospital of the University of Bern, Switzerland. F.F. receives royalties for his textbook Network Neuroscience published by Academic Press.

ClinicalTrials.gov: Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation in Back Pain- Pilot Study, NCT03243084

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ahn S, Ahn M, Cho H, Chan Jun S: Achieving a hybrid brain–computer interface with tactile selective attention and motor imagery. J Neural Eng 11:066004, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn S, Nguyen T, Jang H, Kim JG, Jun SC: Exploring Neuro-Physiological Correlates of Drivers’ Mental Fatigue Caused by Sleep Deprivation Using Simultaneous EEG, ECG, and fNIRS Data. Front Hum Neurosci 10:219, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.André-Obadia N, Peyron R, Mertens P, Mauguière F, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L: Transcranial magnetic stimulation for pain control. Double-blind study of different frequencies against placebo, and correlation with motor cortex stimulation efficacy. Clin Neurophysiol 117:1536–44, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arendsen LJ, Hugh-Jones S, Lloyd DM: Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation at Alpha Frequency Reduces Pain When the Intensity of Pain is Uncertain. J Pain, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B 57:289–300, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bittar RG, Kar-Purkayastha I, Owen SL, Bear RE, Green A, Wang S, Aziz TZ: Deep brain stimulation for pain relief: a meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci 12:515–9, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boord P, Siddall PJ, Tran Y, Herbert D, Middleton J, Craig A: Electroencephalographic slowing and reduced reactivity in neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 46:118–23, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckenmaier CC, Galloway KT, Polomano RC, McDuffie M, Kwon N, Gallagher RM: Preliminary Validation of the Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS) in a Military Population. Pain Med 14:110–23, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camfferman D, Moseley GL, Gertz K, Pettet MW, Jensen MP: Waking EEG Cortical Markers of Chronic Pain and Sleepiness. Pain Med 18:pnw294, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chew T, Ho K-A, Loo CK: Inter- and Intra-individual Variability in Response to Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) at Varying Current Intensities. Brain Stimul 8:1130–7, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM: Responsiveness of the Numeric Pain Rating Scale in Patients with Low Back Pain. Spine 30:1331–4, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delorme A, Makeig S: EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods 134:9–21, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dowman R, Rissacher D, Schuckers S: EEG indices of tonic pain-related activity in the somatosensory cortices. Clin Neurophysiol 119:1201–12, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Essen DC, Smith SM, Barch DM, Behrens TEJ, Yacoub E, Ugurbil K: The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project: An overview. Neuroimage 80:62–79, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS: Chronic pain-associated depression: antecedent or consequence of chronic pain? A review. Clin J Pain 13:116–37, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fregni F, DaSilva D, Potvin K, Ramos-Estebanez C, Cohen D, Pascual-Leone A, Freedman SD: Treatment of chronic visceral pain with brain stimulation. Ann Neurol 58:971–2, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fregni F, Freedman S, Pascual-Leone A: Recent advances in the treatment of chronic pain with non-invasive brain stimulation techniques. Lancet Neurol 6:188–91, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ: A Comparison of a Modified Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Phys Ther 81:776–88, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furman AJ, Meeker TJ, Rietschel JC, Yoo S, Muthulingam J, Prokhorenko M, Keaser ML, Goodman RN, Mazaheri A, Seminowicz DA: Cerebral peak alpha frequency predicts individual differences in pain sensitivity. Neuroimage 167:203–10, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross J, Schnitzler A, Timmermann L, Ploner M: Gamma Oscillations in Human Primary Somatosensory Cortex Reflect Pain Perception. PLoS Biol 5:e133, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helfrich RF, Schneider TR, Rach S, Trautmann-Lengsfeld SA, Engel AK, Herrmann CS, Ruffini G, Miranda PC, Wendling F: Entrainment of Brain Oscillations by Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Curr Biol 24:333–9, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, Williams G, Smith E, Vos T, Barendregt J, Murray C, Burstein R, Buchbinder R: The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 73:968–74, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu L, Peng W, Valentini E, Zhang Z, Hu Y: Functional Features of Nociceptive-Induced Suppression of Alpha Band Electroencephalographic Oscillations. J Pain 14:89–99, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huishi Zhang C, Sohrabpour A, Lu Y, He B: Spectral and spatial changes of brain rhythmic activity in response to the sustained thermal pain stimulation. Hum Brain Mapp 37:2976–91, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen MP, Sherlin LH, Gertz KJ, Braden AL, Kupper AE, Gianas A, Howe JD, Hakimian S: Brain EEG activity correlates of chronic pain in persons with spinal cord injury: clinical implications. Spinal Cord 51:55–8, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung T-P, Makeig S, Humphries C, Lee T-W, McKeown MJ, Iragui V, Sejnowski TJ: Removing electroencephalographic artifacts by blind source separation. Psychophysiology 37:163–78, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasten FH, Herrmann CS: Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) Enhances Mental Rotation Performance during and after Stimulation. Front Hum Neurosci 11:2, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khedr EM, Kotb H, Kamel NF, Ahmed MA, Sadek R, Rothwell JC: Longlasting antalgic effects of daily sessions of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in central and peripheral neuropathic pain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76:833–8, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D, Seo H, Kim, Jun SC, Baron J: Computational Study on Subdural Cortical Stimulation - The Influence of the Head Geometry, Anisotropic Conductivity, and Electrode Configuration. Lytton WW, editor. PLoS One 9:e108028, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lefaucheur J, Drouot X, Nguyen J.: Interventional neurophysiology for pain control: duration of pain relief following repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex. Neurophysiol Clin Neurophysiol 31:247–52, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leo RJ, Latif T: Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in experimentally induced and chronic neuropathic pain: a review. J Pain 8:453–9, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI: The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex is selective for pain: Results from large-scale reverse inference. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A National Academy of Sciences; 112:15250–5, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Llinás R, Urbano FJ, Leznik E, Ramírez RR, van Marle HJF: Rhythmic and dysrhythmic thalamocortical dynamics: GABA systems and the edge effect. Trends Neurosci Elsevier; 28:325–33, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Llinás RR, Ribary U, Jeanmonod D, Kronberg E, Mitra PP: Thalamocortical dysrhythmia: A neurological and neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by magnetoencephalography. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96:15222–7, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.López-Alonso V, Cheeran B, Río-Rodríguez D, Fernández-del-Olmo M: Inter-individual Variability in Response to Non-invasive Brain Stimulation Paradigms . Brain Stimul 7:372–80, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.May ES, Butz M, Kahlbrock N, Hoogenboom N, Brenner M, Schnitzler A: Pre- and post-stimulus alpha activity shows differential modulation with spatial attention during the processing of pain. Neuroimage 62:1965–74, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mellin JM, Alagapan S, Lustenberger C, Lugo CE, Alexander ML, Gilmore JH, Jarskog LF, Fröhlich F: Randomized trial of transcranial alternating current stimulation for treatment of auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 51:25–33, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mouraux A, Guérit J, Plaghki L: Non-phase locked electroencephalogram (EEG) responses to CO2 laser skin stimulations may reflect central interactions between A∂- and C-fibre afferent volleys. Clin Neurophysiol 114:710–22, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mullen T, Kothe C, Chi YM, Ojeda A, Kerth T, Makeig S, Cauwenberghs G, Tzyy-Ping Jung: Real-time modeling and 3D visualization of source dynamics and connectivity using wearable EEG. 35th Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc page 2184–7, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nir R-R, Sinai A, Moont R, Harari E, Yarnitsky D: Tonic pain and continuous EEG: Prediction of subjective pain perception by alpha-1 power during stimulation and at rest. Clin Neurophysiol 123:605–12, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Connell NE, Marston L, Spencer S, DeSouza LH, Wand BM: Non-invasive brain stimulation techniques for chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oostenveld R, Fries P, Maris E, Schoffelen J-M: FieldTrip: Open Source Software for Advanced Analysis of MEG, EEG, and Invasive Electrophysiological Data. Comput Intell Neurosci 2011:e156869, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinheiro ES dos S, Queirós FC de, Montoya P, Santos CL, Nascimento MA do, Ito CH, Silva M, Nunes Santos DB, Benevides S, Miranda JGV, Sá KN, Baptista AF: Electroencephalographic Patterns in Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Schalk G, editor. PLoS One 11:e0149085, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pleger B, Janssen F, Schwenkreis P, Völker B, Maier C, Tegenthoff M: Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex attenuates pain perception in complex regional pain syndrome type I. Neurosci Lett 356:87–90, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ploner M, Gross J, Timmermann L, Pollok B, Schnitzler A: Pain Suppresses Spontaneous Brain Rhythms. Cereb Cortex 16:537–40, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ploner M, Sorg C, Gross J: Brain Rhythms of Pain. Trends Cogn Sci 21:100–10, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rasche D, Rinaldi PC, Young RF, Tronnier VM: Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of various chronic pain syndromes. Neurosurg Focus 21:1–8, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sarnthein J, Jeanmonod D: High thalamocortical theta coherence in patients with neurogenic pain. Neuroimage 39:1910–7, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarnthein J, Stern J, Aufenberg C, Rousson V, Jeanmonod D: Increased EEG power and slowed dominant frequency in patients with neurogenic pain. Brain 129:55–64, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt S, Naranjo JR, Brenneisen C, Gundlach J, Schultz C, Kaube H, Hinterberger T, Jeanmonod D: Pain Ratings, Psychological Functioning and Quantitative EEG in a Controlled Study of Chronic Back Pain Patients. Oreja-Guevara C. PLoS One 7:e31138, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Segerdahl AR, Mezue M, Okell TW, Farrar JT, Tracey I: The dorsal posterior insula subserves a fundamental role in human pain. Nat Neurosci 18:499–500, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shao S, Shen K, Yu K, Wilder-Smith EPV, Li X: Frequency-domain EEG source analysis for acute tonic cold pain perception. Clin Neurophysiol 123:2042–9, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stern J, Jeanmonod D, Sarnthein J: Persistent EEG overactivation in the cortical pain matrix of neurogenic pain patients. Neuroimage 31:721–31, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vossen A, Gross J, Thut G: Alpha Power Increase After Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation at Alpha Frequency (α-tACS) Reflects Plastic Changes Rather Than Entrainment. Brain Stimul 8:499–508, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Vries M, Wilder-Smith O, Jongsma M, Van den Broeke E, Arns M, Van Goor H, Van Rijn C: Altered resting state EEG in chronic pancreatitis patients: toward a marker for chronic pain. J Pain Res 6:815, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vuckovic A, Hasan MA, Fraser M, Conway BA, Nasseroleslami B, Allan DB: Dynamic Oscillatory Signatures of Central Neuropathic Pain in Spinal Cord Injury. J Pain 15:645–55, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wager TD, Atlas LY, Botvinick MM, Chang LJ, Coghill RC, Davis KD, Iannetti GD, Poldrack RA, Shackman AJ, Yarkoni T: Pain in the ACC? Proc Natl Acad Sci 113:E2474–5, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walton KD, Dubois M, Llinás RR: Abnormal thalamocortical activity in patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) type I. Pain 150:41–51, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zaehle T, Rach S, Herrmann CS, Schurmann M, Marshall L: Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation Enhances Individual Alpha Activity in Human EEG. Aleman A: PLoS One 5:e13766, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang ZG, Hu L, Hung YS, Mouraux A, Iannetti GD: Gamma-band oscillations in the primary somatosensory cortex--a direct and obligatory correlate of subjective pain intensity. J Neurosci 32:7429–38, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhuo M: Canadian Association of Neuroscience review: Cellular and synaptic insights into physiological and pathological pain. EJLB-CIHR Michael Smith Chair in Neurosciences and Mental Health lecture. Can J Neurol Sci 32:27–36, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhuo M: Cortical excitation and chronic pain. Trends Neurosci 31:199–207, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Sureness of stimulation measured by a visual analog scale (0–100) between the two stimulation conditions. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used (p=0.0155, paired test).

Supplementary Figure 2. Scatter plots for correlations between peak alpha frequency and pain assessments (DVPRS and ODI). No significant correlation was found in both pain assessments (rho=−0.2085, p=0.3777 for DVRPS, rho=−0.2821, p=0.2281 for ODI).

Supplementary Figure 3. Scatter plots for correlations between Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) and pain assessments (DVPRS and ODI). No significant correlation was found in both pain assessments (rho=−0.1547, p=0.5149 for DVRPS, rho=0.0347, p=0.8845 for ODI).