Abstract

Protein movement between different subcellular compartments is an essential aspect of biological processes, including transcriptional and metabolic regulation, and immune and stress responses. As obligate intracellular parasites, viruses are master manipulators of cellular composition and organization. Accumulating evidences have highlighted the importance of infection-induced protein translocations between organelles. Both directional and temporal, these translocation events facilitate localization-dependent protein interactions and changes in protein functions that contribute to either host defense or virus replication. The discovery and characterization of protein movement is technically challenging, given the necessity for sensitive detection and subcellular resolution. Here, we discuss infection-induced translocations of host and viral proteins, and the value of integrating quantitative proteomics with advanced microscopy for understanding the biology of human virus infections.

Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2019, 48:34–43

This review comes from a themed issue on Omics

Edited by Ileana M Cristea and Kathryn S Lilley

For a complete overview see the Issue and the Editorial

Available online 16th October 2018

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.09.021

1367-5931/© 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Movement of proteins across subcellular space is a fundamental aspect of eukaryotic biology. As proteins drive most cellular processes, directing proteins between specialized organelles is critical for cellular homeostasis (Figure 1 ). Changing location can alter protein lifetime or activity and facilitate interactions, thus modulating the functions of both the moving protein and proximal molecules. For example, nucleo-cytoplasmic translocations are required for gene expression in stress responses [1,2], growth and development [3], and immune signaling [4•]. The cytoskeleton and secretory organelles primarily function in translocating cellular proteins to the proper place in coordination with cellular needs, as in insulin secretion [5], development of cell-cell junctions [6], and neurotransmitter release [7]. Additionally, protein movement is required for the formation and maintenance of some organelles, like autophagosomes [8], mitochondria [9••,10••], and peroxisomes [11]. As an essential mechanism at the core of organelle function and cell viability, the dysregulation of protein translocations can cause critical human diseases, including cancers [12], metabolic disorders [13], and neurodegeneration [14•].

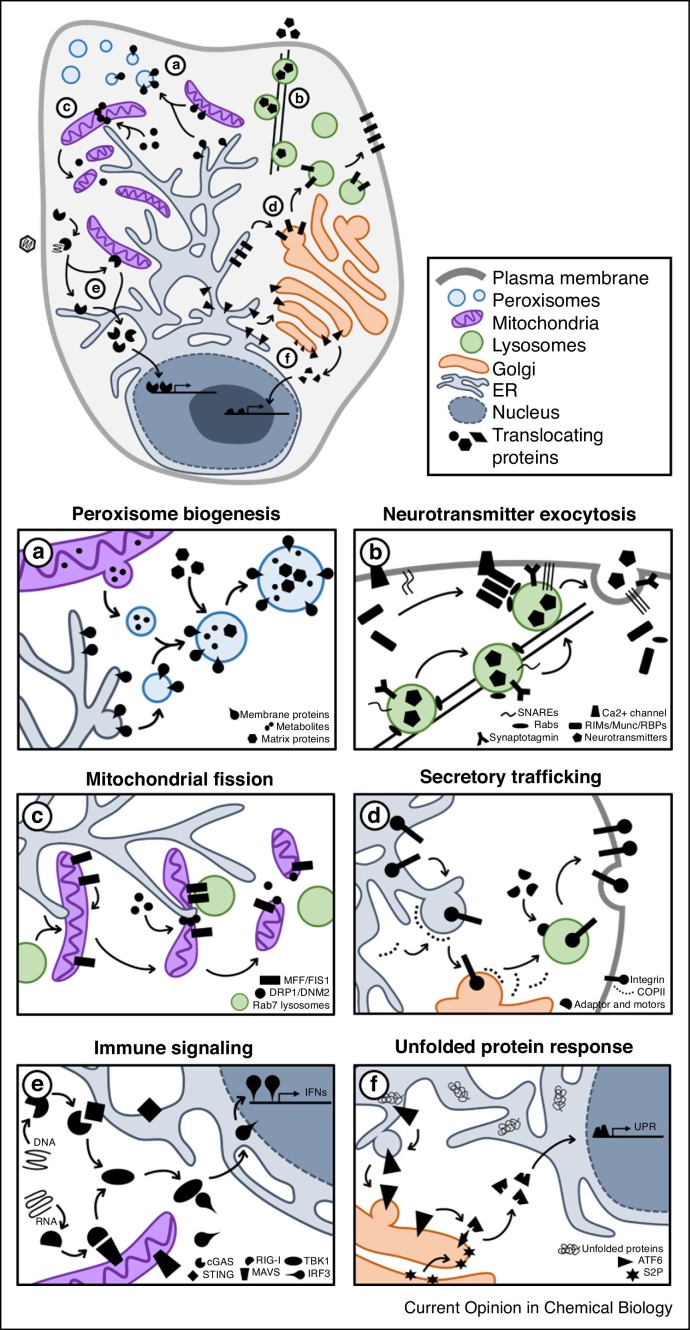

Figure 1.

Movement of proteins across subcellular space is a fundamental aspect of biological processes. Examples of protein translocations necessary for cellular homeostasis and response to biological stimuli: (a)De novo formation of peroxisomes requires movement of ER and mitochondrial factors, and import of matrix proteins from the cytosol. (b) Neurotransmitter release relies on the nanometer-level spatial coordination of secretory, cytoskeletal, trafficking, docking and fusion machineries with calcium triggers. (c) Maintenance of mitochondrial dynamics via fission is a temporally-ordered process that involves contact of sub-mitochondrial domains with the ER and RAB7-coated lysosomes, as well as recruitment of cytosolic fission factors. (d) The synthesis and movement of proteins, such as integrins, through the secretory pathway is dependent on biochemical sorting signals, vesicle fission/fusion machineries, cargo-specific molecular motor adaptors, and cytoskeletal trafficking. (e) Pathogenic DNA and RNA trigger immune response in the cytoplasm to induce the expression of interferon (IFN) genes. (f) An accumulation of unfolded proteins, such as following oxidative stress or viral infection, activates the movement of ATF6 for expression of unfolded protein response (UPR) genes. Abbreviations: Rab3-interacting proteins (RIMs), RIM-binding proteins (RBPs), interferons (IFNs), stimulator of interferon genes (STING), mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS), site-2 protease (S2P).

An accumulating body of work has demonstrated the essential nature of temporal protein movement in infections with human viruses. Diverse protein translocations underlie host defense mechanisms against viruses. In turn, viruses can re-organize subcellular proteomes and finely tune protein interactions to coordinate biological mechanisms for their replication. It is well-recognized that many human viruses, regardless of differences in genome type, virion structure, replication timescale, or tropism, manipulate the spatial regulation of organelles and proteins during infection [15••]. Given recent technological advances, the scope of these directional, temporal, and targeted translocations of host and viral proteins has become increasingly evident. These infection-induced translocations engage host processes to the benefit of either virus or host, and encompass cellular processes like immune sensing [16, 17, 18], mitochondrial integrity [19, 20, 21], genetic manipulation [22,23,24•], and trafficking [25••,26,27••,28].

Protein movement continues to emerge as a critical component of infection and, as such, offers an attractive venue for antiviral therapeutics. However, the knowledge of virus-induced translocations remains limited, partly due to technical challenges. Here, we review both host and viral protein translocations with two major themes: virus replication and antiviral response at the virus-host interface. We also discuss advancements in mass spectrometry and microscopy-based technologies that integrate spatial and temporal resolutions with proteomic scope, providing new avenues for discovering dynamic proteins during infection.

Translocations of host and virus proteins drive virus replication and assembly of infectious particles

The dynamic modulation of the host machinery is at the core of all stages of a productive virus infection–entry into the cell, viral genome replication, assembly of new virions, and virion egress en route to a new host (Figure 2 a). Given the diversity of viral pathogens, which can have RNA or DNA genomes, be enveloped or non-enveloped, and replicate in the nucleus or cytoplasm, the temporality and spatial character of these replication cycles vary [15••]. At the basis of this spatial-temporal regulation is the controlled movement of proteins between different subcellular compartments. Required infection-induced translocations of cellular and viral proteins have been documented for diverse viruses (Figure 2b). For example, dengue virus (DENV) replicates at ER membranes yet requires for this process the Golgi-resident exonuclease ERI3, which is translocated to DENV replication centers upon infection [24•]. Other cytoplasmic-replicating RNA viruses, Zika virus (ZIKV) and the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), stabilize the levels of karyopherin alpha-6 (KPNA6), a protein that is required for virus protein nuclear translocation and viral replication [22]. The nuclear-replicating DNA virus Karposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) also relies on finely-tuned nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling events for its replication. KSHV induces the translocation of Hsp70 isoforms, which are cytoplasmic protein-folding chaperones, to nuclear foci and sites of KSHV genome replication [23].

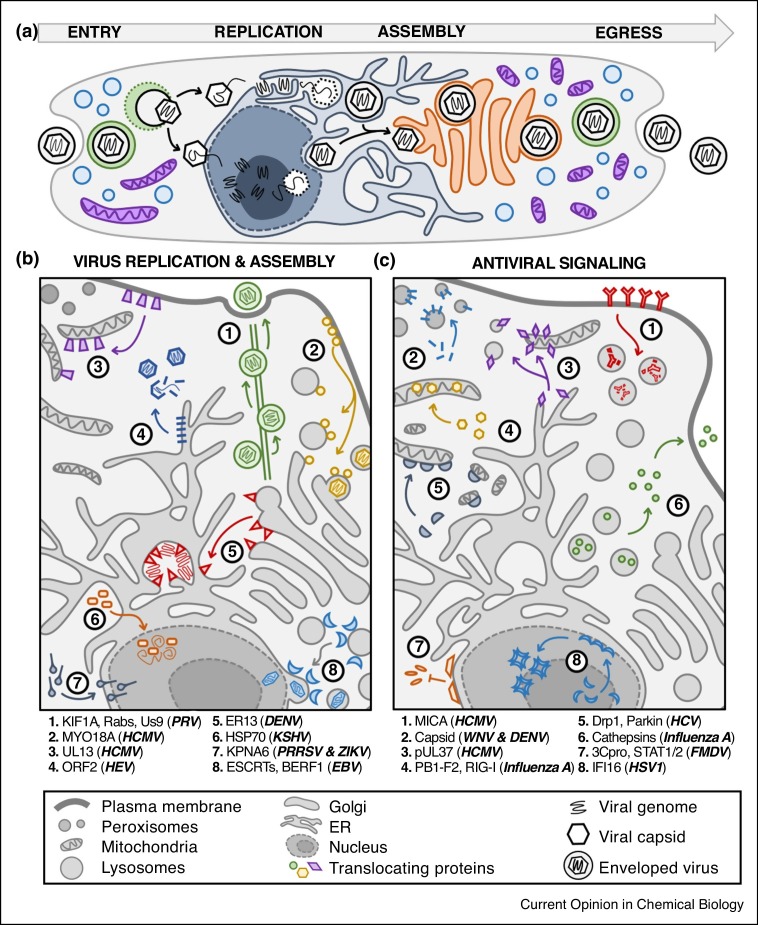

Figure 2.

Virus infection causes the translocations of both host and virus proteins. (a) Viruses have diverse spatial-temporal strategies to enter the cell, replicate their genomes, assemble virions, and egress to infect a new host. (b) Translocations of host and virus proteins are critical for using cellular machineries for virus replication, assembly, and egress. (c) Host antiviral signaling relies on protein translocations between organelles, and viruses can disrupt these movements or translocate viral proteins to attenuate immune response. Abbreviations: endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRTs), MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A (MICA), signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT).

Following viral genome replication, protein translocation events also govern virion assembly, trafficking and egress from the cell. Many viruses package their genomes in higher-order protein assemblies known as capsids, which must be constructed in sync with insertion of the viral genome. Hepatitis E virus (HEV) assembles capsids in the cytoplasm, but the viral major capsid protein, ORF2, is a transmembrane N-linked glycoprotein translated in the ER and primarily found in secretory membranes [29]. Upon initiation of HEV assembly, a portion of the ORF2 protein is retrotranslocated from the ER into the cytosol, where it forms the capsid and packages the viral genome [30•]. Other viruses, such as Influenza A, coat their genomes with proteins before envelopment with membranes containing viral glycoproteins. The Influenza A genome is replicated in the nucleus, while its glycoproteins are translated in the ER and trafficked to the plasma membrane (PM) [31]. Through a feat of global subcellular coordination, the Influenza A genome is exported from the nucleus and translocated to the PM, where it meets viral glycoproteins and exits the cell as a mature viral particle. Alternatively, Epstein Barr virus (EBV) replicates its DNA genome and constructs capsids in the nucleus, but then exports its nucleocapsid to the Golgi for envelopment [28]. To accomplish this, EBV uses its BFRF1 protein to re-localize the ESCRT machinery from endosomal membranes to the nuclear envelope, mediating perinuclear vesicle formation and capsid nuclear egress. The nuclear-replicating human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) also uses a spatially coordinated nuclear capsid egress, and globally rearranges the cellular landscape into a viral assembly complex (AC) of hybrid Golgi and endolysosome membranes and proteins [32]. As a function of endomembrane reorganization, hundreds of proteins move to the AC en masse, including dynein, the chaperone BiP/GRP78, multiple Rabs, mTOR kinase, and HCMV structural proteins [33], while others, many still with unknown functions, are targeted to separate locations across the cell [25••]. For example, the actin-binding motor protein MYO18 A was recently found to translocate from the PM to the AC, localizing to HCMV virions, and is required for HCMV replication, suggesting a repurposing during infection to assist in virus egress [25••]. The axonal transport of pseudorabies virus (PRV), an alphaherpesvirus, is one of the best-studied examples of virus-host protein movement during egress [34]. PRV organizes viral membrane proteins (Us9, gE, and gI), the kinesin-3 motor KIF1A, and multiple secretory Rab GTPases to engage retrograde trafficking mechanisms in neurons [26,27••], thus recruiting intrinsic cellular pathways of protein movement for its infectious cycle.

The host-induced activation and virus-mediated inhibition of antiviral responses rely on protein translocations

The coordinated movement of proteins throughout subcellular space is also essential for signaling cascades underlying host antiviral responses (Figure 2c). Mammalian cells employ sensors to detect the presence of a pathogen (e.g. Figure 1,box d) and activate immune signaling pathways that can induce cytokine expression, inhibit virus replication, and initiate apoptosis. These sensors are located in different subcellular compartments, including PM, ER, mitochondria, peroxisomes, endo-lysosomes, cytoplasm, and nucleus. This diversity provides the means to recognize different virus characteristics (i.e. DNA or RNA genome, glycoproteins, capsid proteins), and signal both in intra- and extra-cellular space. For example, cytoplasmic viral sensors activate transcription factors, such as STATs, NFκB, and interferon regulatory factors (IRFs), which undergo nucleo-cytoplasmic translocation to transcribe immune response genes. Alternatively, host response to influenza A infection, including inflammasome activation, apoptosis, and signaling to neighboring cells, relies on translocation of cathepsin proteins from lysosomes to cytosol and then to extracellular space [35]. Immune transmission can also require sub-organelle translocations. The interferon-inducible protein 16 (IFI16), for example, is a nuclear sensor of viral DNA that undergoes temporal sub-nuclear translocation during infection [4•]. IFI16 moves from a diffuse state to the nuclear periphery to bind incoming viral DNA, engage interferon production, and inhibit virus replication.

As part of the evolutionary ‘arms race’ with their hosts, viruses have acquired mechanisms to combat immune signaling and apoptosis by altering the translocations of host proteins (Figure 2c). For example, Foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) uses its 3C proteinase (3Cpro) to target karyopherin α1 (KPNA1) for degradation, thereby inhibiting STAT1/2 nuclear translocation and the transcription of type I interferon molecules [16]. HSV-1 translocates IFI16 to nucleoplasmic puncta that contain the viral E3 ubiquitin ligase ICP0, thereby targeting IFI16 for degradation and suppressing immune signaling [4•]. Most viruses are known to have mechanisms to suppress apoptosis and cell death. HCMV prevents natural killer cell (NK)-mediated cell death by blocking the cell-surface localization of the NK ligand MHC Class I A (MICA) [17]. This is accomplished by the HCMV proteins pUS18 and pUS20, which translocate MICA from the PM to lysosomes, where MICA is degraded. The RNA virus hepatitis C virus (HCV) disrupts mitochondrial-mediated antiviral response by upregulating translocations of the host proteins dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) and Parkin to the outer mitochondrial membrane, which cause mitochondrial fragmentation and mitophagy, respectively [36]. While these represent homeostatic mechanisms for controlling mitochondrial functions in healthy cells (Figure 1,box c), this over-active protein movement inhibits apoptosis, aids virus production, and is linked to HCV-associated chronic liver disease.

Viral proteins also display dynamic movement through subcellular compartments to attenuate immune signaling. One of the best-studied translocating viral proteins is the multifunctional HCMV protein pUL37, which is synthesized in the ER and translocated to both mitochondria [19] and peroxisomes [37]. pUL37 translocation to sites of ER-mitochondria contact is necessary for its disruption of calcium flux, mitochondrial fragmentation, disruption of mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS), and inhibition of apoptosis [38] (Figure 2c). Strikingly, pUL37 also re-localizes host defense proteins as it moves across subcellular space. Viperin, an interferon-inducible protein, is moved from the ER to mitochondria upon interaction with pUL37 and repurposed to enhance lipid metabolism and support HCMV infection [39]. Bax, a protein required to initiate mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis, is targeted to lipid rafts at ER-mitochondrial contacts by pUL37, thus causing its proteasome-mediated degradation and preventing apoptosis [19]. The capsid proteins of DENV and West Nile virus (WNV) also translocate between multiple organelles during infection (Figure 2c). They are primarily localized to ER-membranes for capsid assembly, but also move to the nucleolus, the surface of lipid droplets, and peroxisomes as infection progresses [40]. While their functions at the nucleolus and lipid droplets remain unclear, their localization to peroxisomes inhibits peroxisome biogenesis and lambda interferon signaling [41]. Viral protein translocations can also be temporally synchronized to compete with host protein translocations. Upon influenza A infection, for example, the host antiviral protein RIG-I, in concert with actin polymers, moves across the cytoplasm to interact with MAVS at mitochondrial membranes and initiate immune response [18] (Figure 1,box e). Influenza A responds by translocating its PB1-F2 protein from the cytoplasm into the mitochondrial inner membrane space, which compromises mitochondrial integrity by decreasing membrane potential, causing mitochondrial fragmentation, inhibiting apoptosis, and suppressing MAVS signaling [20] (Figure 2C). This competition between host and virus protein translocations highlights the spatiotemporal nature and importance of subcellular protein movement during infection.

Given the critical contribution of protein movement to both virus replication and host defense mechanisms, translocations offer attractive targets for antiviral drug development. For example, small molecules that inhibit the movement of viral proteins will also block location-dependent interactions with host machinery that are required for virus replication. This strategy has been applied to multiple virus infections. A target for HCMV antiviral therapy is the viral kinase pUL97, which moves to the nucleolus, nuclear envelope, and cytoplasm to phosphorylate and engage host proteins for viral genome replication, nuclear egress, and secondary envelopment [42]. Additionally, a small molecule screen to inhibit infection of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), an arenavirus with an ssRNA genome, found the strongest antiviral effects stemmed from molecules that disrupted movement of ribonucleoproteins from endosomes into the cytoplasm during virus entry, specifically by blocking the LCMV GP2 glycoprotein [43]. Further discovery of molecules that combat infection by either blocking or enhancing translocation events promise to limit the spread and symptoms of important human pathogens.

Spatiotemporal lenses: detection and quantification of translocation events

Sifting through the vast proteome of an infected cell to discover previously unexplored protein movements remains an outstanding technical challenge for biologists. Investigations must distinguish changes in local abundance from localization, employ sufficient depth to uncover translocation events, and simultaneously examine the proteome with both spatial and temporal scope. Mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics and microscopy techniques can provide varying levels of temporal scope (i.e. one versus many infection time points), spatial detail (i.e. whole-cell versus sub-organelle resolution), and depth of analysis (i.e. single proteins versus whole proteome) (Figure 3 a). Here, we discuss approaches that have previously identified translocating proteins and highlight technological developments that can aid future investigations.

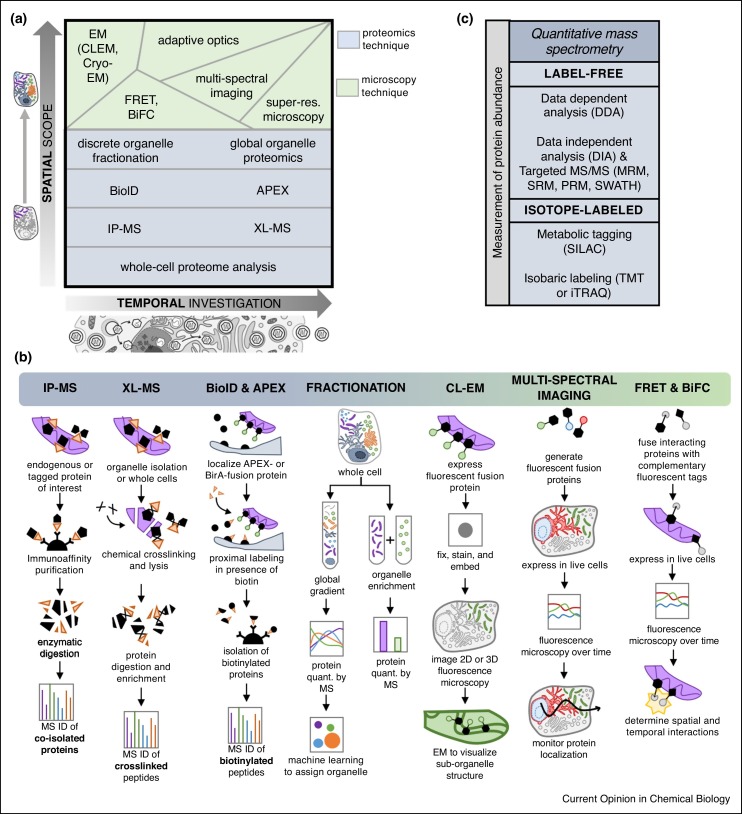

Figure 3.

Mass spectrometry and microscopy methods as tools for detecting and quantifying protein translocations. (a) Varying levels of spatial scope (i.e. single protein versus single organelle versus global cellular analysis) and temporal capability (i.e. one versus many time points of infection) provided by several mass spectrometry and microscopy methods. (b) Schematic representations of selected MS-based proteomic workflows and microscopy methods used in protein translocation studies. (c) Quantitative MS approaches can be used to monitor the abundance of proteins in spatial-temporal proteomic studies. Abbreviations: electron microscopy (EM), correlative light EM (CLEM), Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), bi-molecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC), ascorbate peroxidase (APEX), chemical crosslinking (XL)-MS, immunoaffinity purification (IP)-MS, multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), selected reaction monitoring (SRM), parallel reaction monitoring (PRM), sequential windowed acquisition of all theoretical fragment ion mass spectra (SWATH), stable isotope labeling of amino acids in culture (SILAC), tandem mass tag (TMT), isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ).

MS-based proteomic approaches have significantly contributed to understanding the biology of viral infections [44]. Quantitative MS, including isotope-labeled and label-free methods, have undergone continuous improvements [45,46••], providing the means for detecting thousands of proteins simultaneously, with the accuracy and dynamic range necessary for predicting protein temporal movement across subcellular space (Figure 3b–c). For translocation studies, MS is particularly valuable when coupled with discrete organelle fractionation, pointing to localization-specific changes in protein abundance across infection time. For example, identification of the above-mentioned cathepsin translocation involved a combination of labeling with iTRAQ isobaric tags and fractionation of influenza A-infected macrophages into cytosolic, nuclear, mitochondrial, and secreted proteomes [35]. Metabolic labeling using SILAC and sub-nuclear fractionation was used to distinguish nuclear versus nucleolar translocations to the cytoplasm in both coronavirus [47] and polyomavirus [48] infections, and to discover the role of Hsp70 isoforms in KSHV replication [23]. The further integration of machine-learning algorithms with proteomic data from whole-cell density fractionation expands the spatial information to a global scale [49], and provides a platform for monitoring temporal alterations. To date, this approach has only been applied to HCMV infection [25••], uncovering temporal host protein translocation events needed for virus replication (e.g. MYO18A), as well as the translocation of previously uncharacterized viral proteins (e.g. pUL13). Alternatively, targeted MS methods use unique peptide signatures to detect proteins of interest, including proteins with low abundances or those difficult to isolate (Figure 3c). Targeted MS is thus well suited for sensitive comparisons of proteins between infection states, as demonstrated by the use of selected reaction monitoring (SRM) for the detection of the HIV Gag protein in studies of virus reactivation in patient samples [50]. Although not yet applied to studying protein translocation during infection, if coupled to biochemical fractionation, techniques such as SRM, parallel reaction monitoring (PRM), and sequential window acquisition of all theoretical fragment ion spectra (SWATH) provide excellent tools to quantify proportions of translocating proteins across organelles.

Information about translocating proteins has also been derived from MS-based protein interaction studies, helping to uncover functional protein complexes and localization-dependent changes in interactions relevant for either host defense or virus replication. Immunoaffinity purification (IP)-MS is commonly employed for this purpose and has been instrumental for characterizing infection-induced translocations, such as for Us9 in PRV egress and ERI3 in DENV replication [24•,26]. Use of fluorescent tags for IP–MS in conjunction with isolations at multiple time points during infection helps provide spatial and temporal information of virus-host interactions [51•]. However, the temporal sensitivity and spatial resolution of most IP–MS methods is limited. Techniques that reveal proximity-based interactions provide increased spatial resolution (Figure 3b). Chemical crosslinking (XL) helps to identify inter- or intra-molecular interactions by using crosslinking reagents to form covalent bonds. The integration of XL with MS and use of MS-cleavable protein crosslinkers was shown to be effective for defining sub-organelle protein interactomes [52•], as well as virus-host interactions of the plant pathogen Potato leafroll virus (PLRV) with topological detail [53•]. The proximity-labeling method BioID, while not reaching the spatial resolution provided by XL, increases the scope of detectable interacting proteins by fusing an engineered biotin ligase (BirA) to a protein of interest or a protein marker of subcellular location [54]. Upon treatment with biotin, BirA biotinylates all proteins within a ∼10 nm radius, tagging localization-dependent stable and transient protein interactions. BioID is suited for studying insoluble or difficult-to-purify complexes, and has started to be implemented in viral studies, such as for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Gag protein [55]. The temporal sensitivity of proximity-based tagging was further improved with the introduction of an engineered ascorbate peroxidase (APEX), which requires a brief H2O2 treatment to tag proteins within ∼20 nm of the APEX-protein fusion, decreasing the labeling time to <1 ms [56••]. Although not yet applied to viral infection, APEX provides the power to identify time-sensitive interactions with spatial detail and depth, as shown for signal transduction from G-protein-coupled receptors [56••] and the translocation of ER proteins to ER—PM junctions during calcium entry [57]. However, something that should be considered is that several viruses are known to cause H2O2 imbalance and oxidative stress in the host [58]. For example, host catalase was shown to be packaged within HSV-1 virions to protect viral particles against the reducing environment in the host [59]. Therefore, implementations of this technique must overcome the challenge of promiscuous biotin labeling during infection. Applying compartment and topology-specific controls, such as with APEX fusions to proteins localized at an organelle membrane versus lumen or the cytosol, may provide a filter for the detection of non-specifically tagged proteins.

As the colloquial term states, ‘seeing is believing’, and microscopy can act as either a validation or discovery tool to complement these high-throughput proteomic techniques by visualizing the spatiotemporal dynamics of target proteins in their cellular milieu. Multi-spectral confocal imaging uses fluorescent fusions to track proteins at the organelle-level, in multiple dimensions, and in live cells. This has been the primary method for investigating virus-host protein translocations, leading to discoveries like the nuclear re-localization of ESCRT machinery in EBV infection [28], Golgi-to-ER translocation of ERI3 in DENV infection [24•], and the axonal transport mechanism of PRV [27••], among others. The recent availability of expansive databases of antibodies against human proteins, and their integration with quantitative MS, provides the means to interrogate protein subcellular localization and validate a protein translocation [60••]. Superresolution microscopy further provides sub-organelle, nanometer-level spatial detail of target proteins and has been applied to dynamic infection processes, such as assembly of the pleomorphic Hendra virus (HeV) [61], mitochondrial clustering of the translocating HCMV protein pUL37 [62], and trafficking of the adenovirus genome [63]. Electron microscopy (EM) technologies provide sufficient intracellular spatial resolution to reveal local protein interactions or reorganization of subcellular structures, like membranes or protein complexes [64]. Correlative light EM, for example, demonstrated the hexameric ultrastructure of the herpesvirus nuclear egress complex and its role in remodeling the nuclear envelope [65]. While these microscopy techniques are rich in detail of individual protein dynamics, they are often restricted to single-cell studies of only a few proteins due to limited light channels, diffraction patterns, and genetic roadblocks. Computational advances have begun to address these drawbacks towards high-throughput fluorescence imaging. For example, Valm et al. incorporated a linear unmixing algorithm to distinguish overlapping light spectra, thereby imaging six organelles simultaneously, in three dimensions, and in various conditions (i.e. starvation) [66••]. Alternatively, in silico labeling can identify cellular states (e.g. cell death) and subcellular compartments (e.g. nucleus) from simple bright field images, eliminating the need for fluorescence [67]. Other groups have increased the spatial scope of live-cell fluorescence imaging by coupling adaptive optics to lattice light-sheet microscopy, making it possible to image subcellular dynamics in entire organisms [68••].

Perspectives and concluding remarks

By examining infection cycles with a spatiotemporal lens, we have begun to understand the virus-host relationship as a dynamic process that tailors cellular processes and host response via the coordinated movement of proteins across subcellular space. As MS and microscopy methods continue to improve, investigating infection-induced protein translocations with increased depth of analysis and comprehensive physiological context becomes a reality. Broader contexts for consideration include environmental stresses, host genetics, and co-infection with multiple pathogens, among others. One can envision combining multi-spectral imaging with in silico labeling to increase the proteomic scope of live-cell microscopy studies, employing adaptive optics to track subcellular dynamics during virus transmission across tissues, or using APEX to characterize the trafficking mechanisms of virus egress. Future research must also examine intrinsic protein properties, such as posttranslational modifications, effector molecules, and conformation, to better understand localization-dependent functions and the regulation of a translocating protein. This will be particularly important for proteins that are known to move but have unknown function, such as uncharacterized viral proteins. Translocation studies also promise to aid in the development of novel antiviral therapeutics, as disruption of these critical events, such as by small molecule-mediated inhibition of viral protein movement, can target mechanisms at the core of the virus replication cycle. As the scope of dynamic spatial and temporal coordination during infection becomes more evident, further investigations will have both the opportunity and the challenge to pursue protein translocations as a new perspective for understanding human pathogen infections.

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for funding from NIH (R01 GM114141) and Mallinckrodt Scholar Award to IMC, a Princeton Centennial Award to KCC as well as an NIH training grant from NIGMS (T32GM007388).

References

- 1.Baqader N.O., Radulovic M., Crawford M., Stoeber K., Godovac-Zimmermann J. Nuclear cytoplasmic trafficking of proteins is a major response of human fibroblasts to oxidative stress. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:4398–4423. doi: 10.1021/pr500638h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hetz C., Papa F.R. The unfolded protein response and cell fate control. Mol Cell. 2018;69:169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alchini R., Sato H., Matsumoto N., Shimogori T., Sugo N., Yamamoto N. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of histone deacetylase 9 controls activity-dependent thalamocortical axon branching. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4•.Diner B.A., Lum K.K., Toettcher J.E., Cristea I.M. Viral DNA sensors IFI16 and cyclic GMP-AMP synthase possess distinct functions in regulating viral gene expression, immune defenses, and apoptotic responses during herpesvirus infection. MBio. 2016;7:1–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01553-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Discovers dynamic suborganelle movement as a critical aspect of DNA sensing and immune signaling in multiple herpesvirus infections.

- 5.Lopez J.P., Turner J.R., Philipson L.H. Glucose-induced ERM protein activation and translocation regulates insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E772–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00199.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sako-Kubota K., Tanaka N., Nagae S., Meng W., Takeichi M. Minus end-directed motor KIFC3 suppresses E-cadherin degradation by recruiting USP47 to adherens junctions. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:3851–3860. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-07-1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somasundaram A., Taraska J. Local protein dynamics during microvesicle exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2018 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-12-0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamasaki M., Furuta N., Matsuda A., Nezu A., Yamamoto A., Fujita N., Oomori H., Noda T., Haraguchi T., Hiraoka Y., et al. Autophagosomes form at ER–mitochondria contact sites. Nature. 2013;495:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature11910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9••.Lee J.E., Westrate L.M., Wu H., Page C., Voeltz G.K. Multiple dynamin family members collaborate to drive mitochondrial division. Nature. 2016;54o:139–143. doi: 10.1038/nature20555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Powerful use of microscopy techniques for the discovery of sequential events that drive mitochondrial division.

- 10••.Wong Y.C., Ysselstein D., Krainc D. Mitochondria–lysosome contacts regulate mitochondrial fission via RAB7 GTP hydrolysis. Nature. 2018;554:382–386. doi: 10.1038/nature25486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Demonstrates the subcellular coordination of mitochondrial and lysosomal dynamics via multi-spectral imaging.

- 11.Sugiura A., Mattie S., Prudent J., Mcbride H.M. Newly born peroxisomes are a hybrid of mitochondrial and ER-derived pre-peroxisomes. Nature. 2017;542:251–254. doi: 10.1038/nature21375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerard M., Robin T., Perron P., Hatat A.-S., David-Boudet L., Vanwonterghem L., Busser B., Coll J.-L., Lantuejoul S., Eymin B., et al. Nuclear translocation of IGF1R by intracellular amphiregulin contributes to the resistance of lung tumour cells to EGFR-TKI. Cancer Lett. 2018;420:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordts P.L.S.M., Bartelt A., Nilsson S.K., Annaert W., Christoffersen C., Nielsen L.B., Heeren J., Roebroek A.J.M. Impaired LDL receptor-related protein 1 translocation correlates with improved dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14•.Kim H.J., Taylor J.P. Lost in transportation: nucleocytoplasmic transport defects in ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron. 2017;96:285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Discusses nucleocytoplasmic translocations critical for physiological aging and development of neurodegenerative disease.

- 15••.Jean Beltran P.M., Cook K.C., Cristea I.M. Exploring and exploiting proteome organization during viral infection. J Virol. 2017;91 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00268-17. JVI.00268-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Discusses the importance of organelle manipulation by a broad range of human viruses and the methods best suited to study spatial organization during infection.

- 16.Du Y., Bi J., Liu J., Liu X., Wu X., Jiang P., Yoo D., Zhang Y., Wu J., Wan R., et al. 3Cpro of foot-and-mouth disease virus antagonizes the interferon signaling pathway by blocking STAT1/STAT2 nuclear translocation. J Virol. 2014;88:4908–4920. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03668-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fielding C.A., Aicheler R., Stanton R.J., Wang E.C.Y., Han S., Seirafian S., Davies J., McSharry B.P., Weekes M.P., Antrobus P.R., et al. Two novel human cytomegalovirus NK cell evasion functions target MICA for lysosomal degradation. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004058. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohman T., Rintahaka J., Kalkkinen N., Matikainen S., Nyman T.A. Actin and RIG-I/MAVS signaling components translocate to mitochondria upon influenza A virus infection of human primary macrophages. J Immunol. 2009;182:5682–5692. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang A.P., Hildreth R.L., Colberg-Poley A.M. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits apoptosis by proteasome-mediated degradation of Bax at endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrion contacts. J Virol. 2013;87:5657–5668. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00145-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshizumi T., Ichinohe T., Sasaki O., Otera H., Kawabata S., Mihara K., Koshiba T. Influenza A virus protein PB1-F2 translocates into mitochondria via Tom40 channels and impairs innate immunity. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4713. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S.J., Syed G.H., Siddiqui A. Hepatitis C virus induces the mitochondrial translocation of Parkin and subsequent mitophagy. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003285. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang L., Wang R., Yang S., Ma Z., Lin S., Nan Y., Li Q., Tang Q., Y-J Zhang. Karyopherin alpha6 is required for the replication of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and Zika virus. J Virol. 2018 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00072-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baquero-Perez B., Whitehouse A. Hsp70 isoforms are essential for the formation of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus replication and transcription compartments. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005274. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24•.Ward A.M., Calvert M.E., Read L.R., Kang S., Levitt B.E., Dimopoulos G., Bradrick S.S., Gunaratne J., Garcia-Blanco M.A. The Golgi associated ERI3 is a Flavivirus host factor. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34379. doi: 10.1038/srep34379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Characterizes the translocation and repurposing of the host protein ERI3 for DENV replication.

- 25••.Beltran P.M.J., Mathias R.A., Cristea I.M., Beltran P.M.J., Mathias R.A., Cristea I.M. A Portrait of the human organelle proteome in space and time during Cytomegalovirus infection. Cell Syst. 2016;3:361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.08.012. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First use of spatial proteomics and machine learning to gain temporal information of organelle organization during virus infection.

- 26.Kramer T., Greco T.M., Taylor M.P., Ambrosini A.E., Cristea I.M., Enquist L.W. Kinesin-3 mediates axonal sorting and directional transport of Alphaherpesvirus particles in neurons. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:806–814. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27••.Hogue I.B., Scherer J., Enquist L.W. Exocytosis of Alphaherpesvirus virions, light particles, and glycoproteins uses constitutive secretory mechanisms. MBio. 2016;7:e00820–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00820-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Elegant integration of confocal microscopy and biochemical techniques for investigating the spatial coordination of PRV cellular egress in neurons.

- 28.Lee C.P., Liu P.T., Kung H.N., Su M.T., Chua H.H., Chang Y.H., Chang C.W., Tsai C.H., Liu F.T., Chen M.R. The ESCRT machinery is recruited by the viral BFRF1 protein to the nucleus-associated membrane for the maturation of Epstein-Barr Virus. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002904. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Oya N.J., Escribano-romero E., Blázquez A., Lorenzo M., Martín-acebes M.A., Blasco R., Saiz J. Characterization of hepatitis E virus recombinant orf2 proteins expressed by vaccinia viruses. J Virol. 2012;86:7880–7886. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00610-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30•.Surjit M., Jameel S., Lal S.K. Cytoplasmic localization of the ORF2 protein of hepatitis E virus is dependent on its ability to undergo retrotranslocation from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol. 2007;81:3339–3345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02039-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An early demonstration of a viral protein translocation as a key step in virus assembly.

- 31.Lakdawala S.S., Wu Y., Wawrzusin P., Kabat J., Broadbent A.J., Lamirande E.W., Fodor E., Altan-Bonnet N., Shroff H., Subbarao K. Influenza A virus assembly intermediates fuse in the cytoplasm. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das S., Vasanji A., Pellett P.E. Three-dimensional structure of the human cytomegalovirus cytoplasmic virion assembly complex includes a reoriented secretory apparatus. J Virol. 2007;81:11861–11869. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01077-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das S., Ortiz D.A., Gurczynski S.J., Khan F., Pellett P.E. Identification of human cytomegalovirus genes important for biogenesis of the cytoplasmic virion assembly complex. J Virol. 2014;88:9086–9099. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01141-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor M.P., Enquist L.W. Axonal spread of neuroinvasive viral infections. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lietzen N., Ohman T., Rintahaka J., Julkunen I., Aittokallio T., Matikainen S., Nyman T.A. Quantitative subcellular proteome and secretome profiling of influenza A virus-infected human primary macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001340. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim S., Syed G.H., Khan M., Chiu W., Sohail M.A., Gish R.G. Hepatitis C virus triggers mitochondrial fission and attenuates apoptosis to promote viral persistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:6413–6418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321114111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magalhães A.C., Ferreira A.R., Gomes S., Vieira M., Gouveia A., Valença I., Islinger M., Nascimento R., Schrader M., Kagan J.C., et al. Peroxisomes are platforms for cytomegalovirus’ evasion from the cellular immune response. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26028. doi: 10.1038/srep26028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bozidis P., Williamson C.D., Colberg-Poley A.M. Mitochondrial and Secretory Human Cytomegalovirus UL37 Proteins Traffic into Mitochondrion-Associated Membranes of Human Cells. J Virol. 2008;82:2715–2726. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02456-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seo J.-Y., Yaneva R., Hinson E.R., Cresswell P. Human cytomegalovirus directly induces the antiviral protein viperin to enhance infectivity. Science (80-) 2011:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1202007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Byk L.A., Gamarnik A.V. Properties and functions of the dengue virus capsid protein. Annu Rev Genet. 2016;3:263–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.You J., Hou S., Malik-Soni N., Xu Z., Kumar A., Rachubinski R.A., Frappier L., Hobman T.C. Flavivirus infection impairs peroxisome biogenesis and early antiviral signaling. J Virol. 2015;89:12349–12361. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01365-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldberg M.D., Honigman A., Weinstein J., Chou S., Taraboulos A., Rouvinski A., Shinder V., Wolf D.G. Human cytomegalovirus UL97 kinase and nonkinase functions mediate viral cytoplasmic secondary envelopment. J Virol. 2011;85:3375–3384. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01952-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ngo N., Henthorn K.S., Cisneros M.I., Cubitt B., Iwasaki M., de la Torre J.C., Lama J. Identification and mechanism of action of a novel small-molecule inhibitor of Arenavirus multiplication. J Virol. 2015;89:10924–10933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01587-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 44.Jean Beltran P.M., Federspiel J.D., Sheng X., Cristea I.M. Proteomics and integrative omic approaches for understanding host–pathogen interactions and infectious diseases. Mol Syst Biol. 2017;13:922. doi: 10.15252/msb.20167062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schubert O.T., Röst H.L., Collins B.C., Rosenberger G., Aebersold R. Quantitative proteomics: challenges and opportunities in basic and applied research. Nat Protoc. 2017;12:1289–1294. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46••.Mulvey C.M., Breckels L.M., Geladaki A., Britovšek N.K., Nightingale D.J.H., Christoforou A., Elzek M., Deery M.J., Gatto L., Lilley K.S. Using hyperLOPIT to perform high-resolution mapping of the spatial proteome. Nat Protoc. 2017;12:1110–1135. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Advancement in quantitative mass spectrometry offering assessment of subcellular protein localization on a global scale with suborganelle resolution.

- 47.Emmott E., Rodgers M.A., Macdonald A., McCrory S., Ajuh P., Hiscox J.A. Quantitative proteomics using stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture reveals changes in the cytoplasmic, nuclear, and nucleolar proteomes in Vero cells infected with the coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1920–1936. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900345-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Justice J.L., Verhalen B., Kumar R., Lefkowitz E.J., Imperiale M.J., Jiang M. Quantitative proteomic analysis of enriched nuclear fractions from BK polyomavirus-infected primary renal proximal tubule epithelial cells. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:4413–4424. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christoforou A., Mulvey C.M., Breckels L.M., Geladaki A., Hurrell T., Hayward P.C., Naake T., Gatto L., Viner R., Arias A.M., et al. A draft map of the mouse pluripotent stem cell spatial proteome. Nat Commun. 2016;7:1–12. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlatzer D., Haqqani A.A., Li X., Dobrowolski C., Chance M.R., Tilton J.C. A targeted mass spectrometry assay for detection of HIV gag protein following induction of latent viral reservoirs. Anal Chem. 2017;89:5325–5332. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b05070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51•.Cristea I.M., Carroll J.W.N., Rout M.P., Rice C.M., Chait B.T., MacDonald M.R. Tracking and elucidating Alphavirus-host protein interactions. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30269–30278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603980200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First integration of IP-MS and microscopy for studying temporal virus-host interactions.

- 52•.Schweppe D.K., Chavez J.D., Lee C.F., Caudal A., Kruse S.E., Stuppard R., Marcinek D.J., Shadel G.S., Tian R., Bruce J.E. Mitochondrial protein interactome elucidated by chemical cross-linking mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:1732–1737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1617220114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Demonstrates the value of XL-MS for mapping suborganelle organization of protein complexes.

- 53•.DeBlasio S.L., Chavez J.D., Alexander M.M., Ramsey J., Eng J.K., Mahoney J., Gray S.M., Bruce J.E., Cilia M. Visualization of host-polerovirus interaction topologies using protein interaction reporter technology. J Virol. 2015;90:1973–1987. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01706-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First application of XL-MS to a viral infection study.

- 54.Varnaitė R., MacNeill S.A. Meet the neighbors: mapping local protein interactomes by proximity-dependent labeling with BioID. Proteomics. 2016;16:2503–2518. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ritchie C., Cylinder I., Platt E.J., Barklis E. Analysis of HIV-1 gag protein interactions via biotin ligase tagging. J Virol. 2015;89:3988–4001. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03584-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56••.Lobingier B.T., Hüttenhain R., Eichel K., Miller K.B., Ting A.Y., von Zastrow M., Krogan N.J. An approach to spatiotemporally resolve protein interaction networks in living cells. Cell. 2017;169:350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.022. e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Demonstrates the ability of APEX to characterize inherently dynamic cellular processes.

- 57.Jing J., He L., Sun A., Quintana A., Ding Y., Ma G., Tan P., Liang X., Zheng X., Chen L., et al. Proteomic mapping of ER-PM junctions identifies STIMATE as a regulator of Ca 2+ influx. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1339–1347. doi: 10.1038/ncb3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ivanov A.V., Bartosch B., Isaguliants M.G. Oxidative stress in infection and consequent disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1–3. doi: 10.1155/2017/3496043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Newcomb W.W., Brown J.C. Internal catalase protects herpes simplex virus from inactivation by hydrogen peroxide. J Virol. 2012;86:11931–11934. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01349-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60••.Thul P.J., Åkesson L., Wiking M., Mahdessian D., Geladaki A., Ait Blal H., Alm T., Asplund A., Björk L., Breckels L.M., et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science. 2017;80-:1–12. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Powerful integration of immunofluorescence microscopy and quantitative mass spectrometry for defining protein localization on a global scale.

- 61.Monaghan P., Green D., Pallister J., Klein R., White J., Williams C., McMillan P., Tilley L., Lampe M., Hawes P., et al. Detailed morphological characterisation of Hendra virus infection of different cell types using super-resolution and conventional imaging. Virol J. 2014;11:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12985-014-0200-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colberg-Poley A.M., Patterson G.H., Salka K., Bhuvanendran S., Yang D., Jaiswal J.K. Superresolution imaging of viral protein trafficking. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2015;204:449–460. doi: 10.1007/s00430-015-0395-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang I.H., Suomalainen M., Andriasyan V., Kilcher S., Mercer J., Neef A., Luedtke N.W., Greber U.F. Tracking viral genomes in host cells at single-molecule resolution. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:468–480. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Boer P., Hoogenboom J.P., Giepmans B.N.G. Correlated light and electron microscopy: ultrastructure lights up! Nat Methods. 2015;12:503–513. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hagen C., Dent K.C., Zeev-Ben-Mordehai T., Grange M., Bosse J.B., Whittle C., Klupp B.G., Siebert C.A., Vasishtan D., Bäuerlein F.J.B., et al. Structural Basis of Vesicle Formation at the Inner Nuclear Membrane. Cell. 2015;163:1692–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66••.Valm A.M., Cohen S., Legant W.R., Melunis J., Hershberg U., Wait E., Cohen A.R., Davidson M.W., Betzig E., Lippincott-Schwartz J. Applying systems-level spectral imaging and analysis to reveal the organelle interactome. Nature. 2017;546:162–167. doi: 10.1038/nature22369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A significant development in the capability of live-cell multi-spectral imaging systems, and direct application to the study of subcellular organization and dynamics.

- 67.Christiansen E.M., Yang S.J., Ando D.M., Javaherian A., Skibinski G., Lipnick S., Mount E., O’Neil A., Shah K., Lee A.K., et al. In silico labeling: predicting fluorescent labels in unlabeled images. Cell. 2018;173:792–803. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68••.Liu T., Upadhyayula S., Milkie D.E., Singh V., Wang K., Swinburne I.A., Mosaliganti K.R., Collins Z.M., Hiscock T.W., Shea J., et al. Observing the cell in its native state: Imaging subcellular dynamics in multicellular organisms. Science (80-) 2018;360 doi: 10.1126/science.aaq1392. eaaq 1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Technological advancement in lattice light-sheet microscopy and its application to subcellular organization and dynamics in whole-organism studies.