Abstract

PURPOSE:

Major pathologic response (MPR) following neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been defined as ≤10% residual viable tumor, without distinguishing between histologic types. We sought to investigate whether the optimal cutoff percentage of residual viable tumor for predicting survival differs between lung adenocarcinoma (ADC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

Tumor slides from 272 patients treated with NAC and surgery for clinical stage II-III NSCLC (ADC, n=192; SCC, n=80) were reviewed. The optimal cutoff percentage of viable tumor for predicting lung cancer–specific cumulative incidence of death (LC-CID) was determined using maximally selected rank statistics. LC-CID was analyzed using a competing-risks approach. Overall survival (OS) was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier methods and Cox proportional hazard analysis.

RESULTS:

Patients with SCC had a better response to NAC (median percentage of viable tumor: SCC vs ADC, 40% vs 60%; P=0.027). MPR (≤10% viable tumor) was observed in 26% of SCC cases versus 12% of ADC cases (P=0.004). The optimal cutoff percentage of viable tumor for LC-CID was 10% for SCC and 65% for ADC. On multivariable analysis, viable tumor ≤10% was an independent factor for better LC-CID (P=0.035) in patients with SCC; in patients with ADC, viable tumor ≤65% was a factor for better LC-CID (P=0.033) and OS (P=0.050).

CONCLUSION:

In response to NAC, the optimal cutoff percentage of viable tumor for predicting survival differs between ADC and SCC. Our findings have implications for the pathologic assessment of resected specimens, especially in upcoming clinical trials design.

Keywords: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, non-small cell lung cancer, viable tumor, pathologic response, prognosis

Introduction

Platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) improves survival in patients with locoregionally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), compared with surgery alone. Available tissue assessment following NAC provides information about treatment effect, which in turn predicts survival and can potentially be used as a surrogate endpoint in clinical trials.1, 2

Junker and colleagues3, 4 demonstrated that a cutoff of 10% of viable tumor was optimal for predicting improved long-term outcomes in patients with locoregionally advanced NSCLC treated with NAC and surgery, and this has been validated in multiple studies.2, 5–8 A more-recent meta-analysis proposed major pathologic response (MPR), defined as ≤10% residual viable tumor, as a surrogate endpoint for survival in patients treated with NAC and surgery.1

With advances in molecular biology and observations of histologic type–specific therapeutic efficacy, treatment strategies for patients with metastatic NSCLC have become highly dependent on histologic type (adenocarcinoma [ADC] and squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]).9–12 In contrast, treatment options for patients with nonmetastatic (early-stage or locoregionally advanced or resectable) NSCLC currently do not differ between histologic types. Of fourteen studies that investigated pathologic response and outcomes following NAC for NSCLC (Supplementary Table S1),2, 4–8, 13–21 three reported treatment responses separately for patients with SCC and ADC (or nonsquamous NSCLC)—the results of these studies demonstrated that SCC was associated with better treatment response than ADC.14, 17, 18 With the exception of one phase II trial,2 no study has addressed whether MPR differs between SCC and ADC.

On the basis of these observations, we hypothesized that the optimal cutoff percentage of viable tumor for predicting survival may differ between SCC and ADC. We sought to comprehensively evaluate histologic findings following NAC in patients with locoregionally advanced (clinical stage II-III) lung ADC and SCC.

Patients and Methods

Study Cohort

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK). We reviewed the MSK Thoracic Service’s prospectively maintained lung cancer database to identify consecutive patients who underwent platinum-based NAC followed by resection (lobectomy or greater) for clinical stage II-III NSCLC at MSK between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2014.

As significant differences in treatment response between NAC with and without radiotherapy have been reported,21 patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy were excluded from analysis. In total, 272$ patients were included in the study (Supplementary Figure S1). Correlative clinical data were retrieved from our prospectively maintained Thoracic Surgery Service Lung Cancer Database.

Histologic Evaluation

All available tumor slides were reviewed by at least three experienced pathologists (Y.Q., K.E., R.G.A., and W.D.T.) blinded to patient treatment and outcomes. An Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a standard 22-m diameter eyepiece was used. Discrepancies in histologic evaluation between the pathologists were resolved by consensus using a multihead microscope. For patients with no residual viable tumor after NAC, histologic subtype was determined by review of biopsy specimens obtained before NAC.

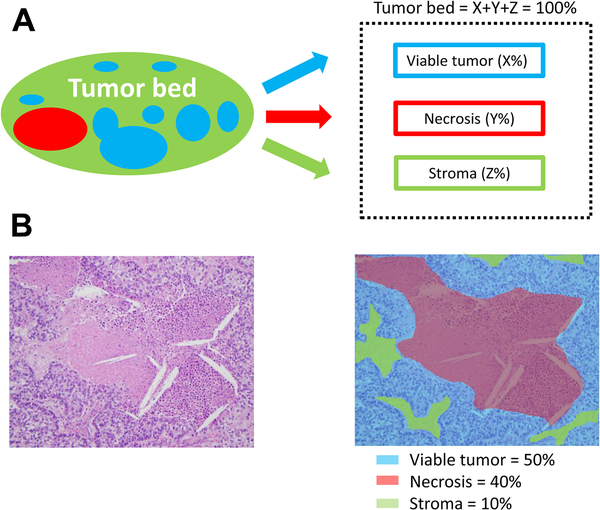

Tumor bed was defined as the area where the original tumor (before NAC) was considered to be located, and it consists of the following components: viable tumor area; necrosis; and stromal tissue, including fibrosis and inflammatory cells. Perilobular fibrous thickening, fibrosis or inflammation due to obstructive pneumonia or interstitial lung disease, and directly involved metastatic lymph nodes were not considered part of the tumor bed. The percentages of viable tumor area, necrosis, and stroma within the tumor bed, across all tumor sections, were estimated in 5% increments so that these components totaled 100% of the tumor bed. To account for fibrosis and inflammatory cells within stromal tissue, the proportion of fibrosis and inflammatory cells among stromal tissue was recorded in 5% increments, and the proportion among the tumor bed was calculated by taking into consideration the proportion of stromal tissue among the tumor bed (Supplementary Figure S2). Figure 1 shows an example of how the three major chemotherapy-related histologic components were evaluated. MPR was defined as ≤10% viable tumor.1 Other histologic components evaluated are shown in Supplementary Figure S3.4, 22, 23 Pleural invasion and lymphovascular invasion (LVI) were evaluated.

Fig 1.

Histologic components in the tumor bed. (A) Schematic image showing how percentage compositions are assigned. The tumor bed is divided into viable tumor area, necrosis, and stroma. Stroma includes inflammation and fibrosis. (B) A representative hematoxylin & eosin slide image (left; original image, 200× magnification) and a corresponding color illustration of the distribution of histologic components (right). The blue, red, and black areas represent viable tumor, necrosis, and stroma, respectively.

Tumors were classified in accordance with the 2015 WHO classification of Tumors of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus, and Heart (4th edition)24 and the 8th edition of the AJCC TNM staging manual.25–27 Pathologic stage following NAC (ypStage) was determined on the basis of “tumor bed size” and “viable tumor size.” According to the recommendation of the IASLC Staging Committee and the 8th edition TNM classification, viable tumor size was estimated using the following equation25–27:

Statistical Analysis

The associations between clinicopathologic factors and histologic type (ADC vs SCC) were analyzed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test (for categorical variables) and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for continuous variables). The optimal cutoff percentages of histologic components for predicting lung cancer–specific survival were estimated using maximally selected rank statistics with the R package maxstat.28

Interobserver variability in viable tumor estimation was made in a blinded fashion by two pathologists who evaluated 30 tumors (20 ADC and 10 SCC), representing 10% of the study population. Interobserver agreement was quantified by intraclass correlation (ICC), on the basis of single fixed raters model specification. The ICC estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the psych R package in R 3.5.1. ICC values range from 0 to 1; an ICC close to 1 indicates high similarity between the two pathologists. In addition, we present a Bland-Altman plot of between-pathologist assessments at the specimen level.29 The Bland-Altman plot is a graphical method that plots the differences between the two pathologists’ assessments against the averages of the two pathologists’ assessments. This plot can reveal the relationship between the differences and magnitude of measurements to uncover systematic bias and assess repeatability. Horizontal lines are drawn at the mean difference and at the limits of agreement (defined as the mean difference plus and minus 1.96 times the standard deviation of the differences).

The cumulative incidence function was used to estimate lung cancer–specific cumulative incidence of death (LC-CID) and cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) after surgical resection. Death due to non-lung cancer–specific causes and death without recurrence were considered competing risks for LC-CID and CIR, respectively.30–32 Otherwise, patients were censored at the time of the last available follow-up. Differences in CIR or LC-CID between groups were assessed using the Gray method.33 Associations between variables and CIR or LC-CID were estimated using Fine and Gray competing-risk regression models.34 Multivariable models were constructed, starting with variables with P<0.1 in univariable analyses. For overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS), survival curve analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in OS and DFS between groups were evaluated using the log-rank test. Associations between variables and OS or DFS were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model. All significance tests were two-sided, and 0.05 was set as the level of statistical significance.

Results

Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Comparison between ADC and SCC

The study population included 192 patients with ADC (71%) and 80 patients with SCC (29%). The median number of sections submitted per patient was 5 (range, 1–24) (Supplementary Figure S4). Patients with SCC were more likely to have the following: male sex, smoker, higher pack-year index, greater extent of resection (pneumonectomy or bilobectomy), less adjuvant radiotherapy, lower ypN status, lower ypStages (based on both tumor bed size and viable tumor size), and less lymphovascular invasion. MPR occurred more often among patients with SCC (SCC vs ADC, 26% vs 12%; P=0.004). SCC was also associated with a smaller proportion of residual viable tumor area, a greater proportion of necrosis, and more frequent hyalinized stroma (Table 1). Histologic subtypes of ADC are summarized in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic and histologic characteristics of the overall, ADC, and SCC cohorts

| Characteristic | Total (N=272) | ADC (N=192) | SCC (N=80) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66 | (58, 72) | 66 | (58, 71) | 66 | (58, 73) | 0.3 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 140 | (51) | 114 | (59) | 26 | (33) | <0.001 |

| Male | 132 | (49) | 78 | (41) | 54 | (68) | |

| Smoking | |||||||

| Never | 27 | (10) | 25 | (13) | 2 | (3) | 0.005 |

| Former | 213 | (78) | 149 | (78) | 64 | (80) | |

| Current | 32 | (12) | 18 | (9) | 14 | (18) | |

| Pack-years | 32 | (17, 50) | 27 | (12, 45) | 42 | (30, 60) | <0.001 |

| cStage | |||||||

| II | 66 | (24) | 41 | (21) | 25 | (31) | 0.090 |

| III | 206 | (76) | 151 | (79) | 55 | (69) | |

| Resection type | |||||||

| Pneumonectomy | 36 | (13) | 17 | (9) | 19 | (24) | 0.002 |

| Bilobectomy | 21 | (8) | 13 | (7) | 8 | (10) | |

| Lobectomy | 215 | (79) | 162 | (84) | 53 | (66) | |

| R class | |||||||

| R0 | 263 | (97) | 185 | (96) | 78 | (98) | 1 |

| R1 | 9 | (3) | 7 | (4) | 2 | (3) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (n=271) | |||||||

| No | 237 | (87) | 165 | (86) | 72 | (91) | 0.3 |

| Yes | 34 | (13) | 27 | (14) | 7 | (9) | |

| Postoperative radiotherapy (n=271) | |||||||

| No | 174 | (64) | 110 | (57) | 64 | (81) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 97 | (36) | 82 | (43) | 15 | (19) | |

| Tumor bed size, cm | 3.5 | (2.1, 4.8) | 3.5 | (2.1, 4.6) | 3.2 | (2.0, 5.2) | 0.8 |

| Viable tumor size, cm† | 1.4 | (0.6, 2.8) | 1.4 | (0.7, 2.7) | 1.4 | (0.2, 3.0) | 0.5 |

| ypN | |||||||

| N0 | 101 | (37) | 61 | (32) | 40 | (50) | 0.008 |

| N1a | 52 | (19) | 36 | (19) | 16 | (20) | |

| N1b | 8 | (3) | 5 | (3) | 3 | (4) | |

| N2a | 75 | (28) | 58 | (30) | 17 | (21) | |

| N2b | 36 | (13) | 32 | (17) | 4 | (5) | |

| ypStage based on tumor bed size | |||||||

| I | 58 | (21) | 33 | (17) | 25 | (31) | 0.038 |

| II | 74 | (27) | 54 | (28) | 20 | (25) | |

| III | 140 | (51) | 105 | (55) | 35 | (44) | |

| ypStage based on viable tumor size | |||||||

| 0 | 2 | (1) | 1 | (1) | 1 | (1) | 0.004 |

| I | 86 | (32) | 54 | (28) | 32 | (40) | |

| II | 67 | (25) | 42 | (22) | 25 | (31) | |

| III | 117 | (43) | 95 | (49) | 22 | (28) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |||||||

| Absent | 88 | (32) | 51 | (27) | 37 | (46) | 0.003 |

| Present | 184 | (68) | 141 | (73) | 43 | (54) | |

| Pleural invasion | |||||||

| PL0 | 215 | (79) | 146 | (76) | 69 | (86) | 0.2 |

| PL1/2 | 49 | (18) | 40 | (21) | 9 | (11) | |

| PL3 | 8 | (3) | 6 | (3) | 2 | (3) | |

| Gene alteration (n=173) | |||||||

| Wild-type | 102 | (59) | |||||

| EGFR | 15 | (9) | |||||

| KRAS | 56 | (32) | |||||

| MPR* | |||||||

| No (>10%) | 228 | (84) | 169 | (88) | 59 | (74) | 0.004 |

| Yes (≤10%) | 44 | (16) | 23 | (12) | 21 | (26) | |

| Viable tumor, % | 50 | (30, 70) | 60 | (30, 70) | 40 | (10, 70) | 0.027 |

| Necrosis, % | 0 | (0, 10) | 0 | (0, 5) | 5 | (0, 15) | <0.001 |

| Stroma (fibrosis + inflammation), % | 35 | (20, 70) | 35 | (20, 63) | 38 | (18, 70) | 0.9 |

| Inflammation, % | 9 | (3, 16) | 9 | (4, 18) | 8 | (3, 14) | 0.3 |

| Fibrosis, % | 24 | (10, 49) | 25 | (11, 49) | 24 | (9, 51) | 0.8 |

| Fibroelastotic scar | 133 | (49) | 101 | (53) | 32 | (40) | 0.063 |

| Hyalinization | 89 | (33) | 50 | (26) | 39 | (49) | <0.001 |

| Reactive giant cells | 151 | (56) | 107 | (56) | 44 | (55) | 1 |

| Cholesterol clefts | 137 | (50) | 96 | (50) | 41 | (51) | 0.9 |

| Foamy macrophages | 121 | (44) | 83 | (43) | 38 | (48) | 0.6 |

| Calcification | 60 | (22) | 48 | (25) | 12 | (15) | 0.079 |

NOTE. Data are shown as no. (%) or median (25th, 75th percentile). ADC, adenocarcinoma; MPR, major pathologic response; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Viable tumor size was estimated by tumor bed size and proportion of viable tumor and invasive component.

Major pathologic response was defined as the percentage of viable tumor ≤10%.

Reproducibility for viable tumor proportion

There was a high degree of interobserver reliability between pathologist assessments for both ADC (ICC=0.97; 95% CI, 0.93–0.99) and SCC (ICC=0.99; 95% CI, 0.96–1.00) (Supplementary Figure S5). On the basis of the Bland-Altman plot, the differences were all close to 0 (indicating no systematic bias). For any future samples, the differences between measurements from two pathologists should lie within the limits of agreement approximately 95% of the time.

Clinical Significance of MPR (≤10% Viable Tumor) in the Overall (ADC + SCC) Cohort

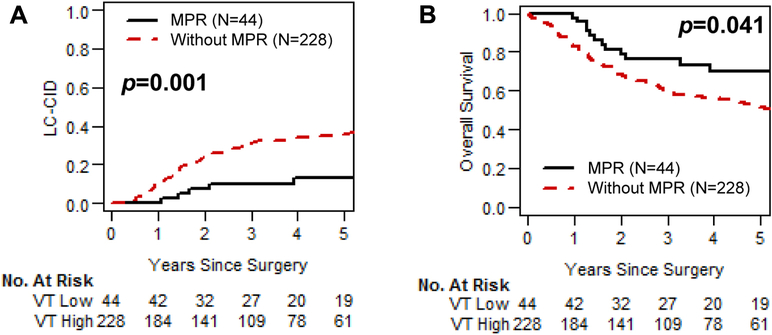

Figure 2 shows LC-CID and OS curves for patients with and without MPR in the overall cohort. MPR was associated with significantly better LC-CID and OS (MPR vs no MPR: 5-year LC-CID, 13% vs 36% [P=0.001]; 5-year OS, 70% vs 51% [P=0.041]) (Fig 2A and 2B).

Fig 2.

Lung cancer–specific cumulative incidence of death (LC-CID) and overall survival for patients with and without major pathologic response (MPR; ≤10% viable tumor). (A) MPR was associated with significantly better LC-CID (P=0.001). (B) MPR was associated with significantly better overall survival (P=0.041). VT, viable tumor.

Optimal Cutoff Percentage of Viable Tumor

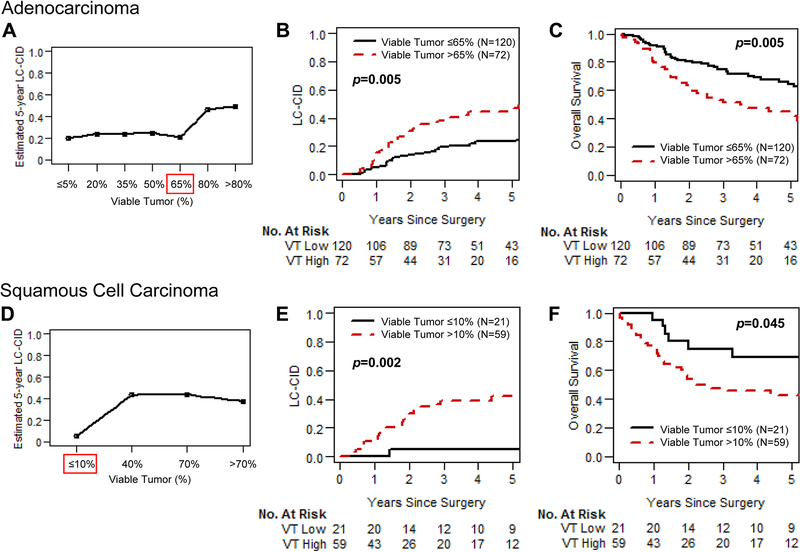

For patients with ADC, the most common percentage of viable tumor (by 10% increment) was 61%−70%, whereas for patients with SCC this was 0%−10%. Supplementary Figures S6A (for ADC) and S6B (for SCC) show the distribution of percentage of viable tumor in 10% increments. The optimal cutoff percentage of histologic components for predicting LC-CID was determined in patients with ADC and SCC separately using maximally selected rank statistics. Survival analysis also showed that the optimal cutoff percentage of viable tumor was markedly different between ADC (65%) and SCC (10%).

Estimated 5-year LC-CID for patients with ADC, by percentage of viable tumor, is shown in Figure 3A. The increase in LC-CID after 65% suggests that 65% is the optimal cutoff percentage of viable tumor to predict prognosis in patients with ADC. Estimated 5-year LC-CID for patients with SCC, by percentage of viable tumor, is shown in Figure 3D. The increase in LC-CID after 10% suggests that 10% is the optimal cutoff percentage for SCC. This matches the previously established definition of MPR from the literature.

Fig 3.

Association between percentage of viable tumor and prognosis for patients with adenocarcinoma (ADC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). (A) Estimated 5-year lung cancer–specific cumulative incidence of death (LC-CID) by percentage of viable tumor for patients with ADC is shown. The Y-axis represents seven groups of patients on the basis of percentage of viable tumor: ≤5% (n=13; 0%−5%), 20% (n=24; 6%−20%), 35% (n=23; 21%−35%), 50% (n=35; 36%−50%), 65% (n=25; 51%−65%), 80% (n=52; 66%−80%), and >80% (n=20; 81%−100%). (B) LC-CID for patients with ADC with high (>65%) and low (≤65%) viable tumor is shown. Patients with high viable tumor had significantly worse LC-CID than those with low viable tumor. (C) Overall survival for patients with ADC with high (>65%) and low (≤65%) viable tumor is shown. Patients with high viable tumor had significantly worse OS than those with low viable tumor. (D) Estimated 5-year LC-CID by percentage of viable tumor for patients with SCC is shown. The Y-axis represents four groups of patients on the basis of percentage of viable tumor: ≤10% (n=21; 0%−10%), 40% (n=21; 11%−40%), 70% (n=21; 41%−70%), and >70% (n=17; 71%−100%). (E) LC-CID for patients with SCC with high (>10%) and low (≤10%) viable tumor is shown. Patients with high viable tumor had significantly worse LC-CID than those with low viable tumor. (F) Overall survival for patients with SCC with high (>10%) and low (≤10%) viable tumor is shown. Patients with high viable tumor has significantly worse OS than those with low viable tumor.

The optimal cutoffs for other histologic components (necrosis and stromal tissue) also differed by histologic type (these were also determined using maximally selected rank statistics). Estimated 5-year LC-CID by percentage of necrosis, stroma, inflammation, and fibrosis are shown in Supplementary Figure S7.

Optimal Cutoff Percentage of Viable Tumor and Prognosis

LC-CID and OS curves for patients with viable tumor higher than the optimal cutoff value (high viable tumor) and equal to or lower than the optimal cutoff value (low viable tumor) are shown in Figure 3. Patients with ADC with low (≤65%) viable tumor had significantly better LC-CID and OS than those with high (>65%) viable tumor (low vs high viable tumor: 5-year LC-CID, 23% vs 47% [P=0.005]; 5-year OS, 64% vs 42% [P=0.005]) (Fig 3B and 3C). Similarly, CIR and DFS were better among patients with ADC with low viable tumor (Supplementary Figure S8A and S8B). We also analyzed the prognostic value of MPR (≤10% viable tumor). In patients with ADC, MPR (≤10% viable tumor) was associated with a nonsignificant trend toward better LC-CID and OS (MPR vs no MPR: 5-year LC-CID, 21% vs 34% [P=0.090]; 5-year OS, 70% vs 54% [P=0.162]).

Patients with SCC with low (≤10%) viable tumor had significantly better LC-CID and OS than those with high viable tumor (low vs high viable tumor: 5-year LC-CID, 5% vs 42% [P=0.002]; 5-year OS, 69% vs 42% [P=0.045]) (Fig 3E and 3F). Similarly, CIR and DFS were better among patients with SCC with low viable tumor (Supplementary Figure S8C and S8D).

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses in Patients with ADC

Table 2 shows the results of univariable and multivariable competing-risk regression analyses for LC-CID in patients with ADC. In the final multivariable model, percentage of viable tumor >65% was associated with higher LC-CID (subhazard ratio [SHR], 1.77 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.05–2.98]; P=0.033), independently of ypN status. Owing to their significant association with ypN status and/or percentage of viable tumor, other tumor stage–related variables (cStage, ypStage, tumor size) and other histologic components (stromal tissue, inflammation, fibrosis) were not included in the final multivariable model. In addition, owing to its significant association with ypN status, adjuvant radiotherapy was not included in the final multivariable model.

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable competing-risk regression analysis for lung cancer-specific death in patients with lung ADC (N=192)

| Risk factor for overall death | No. | (%) | Univariable analysis | Final multivariable model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR | 95% CI | P | SHR | 95% CI | P | |||

| Age (per 1-year increase) | 1.01 | (0.98–1.03) | 0.5 | |||||

| Male sex (vs female) | 78 | (41) | 0.92 | (0.56–1.53) | 0.8 | |||

| Smoking status (vs never) | ||||||||

| Former | 149 | (78) | 0.96 | (0.46–1.98) | 0.9 | |||

| Current | 18 | (9) | 1.09 | (0.36–3.33) | 0.9 | |||

| Pack-years (per 1-pack-year increase) | 1.00 | (0.99–1.01) | 0.7 | |||||

| cStage III (vs II) | 151 | (79) | 3.09 | (1.29–7.43) | 0.012 | * | ||

| Resection type (vs lobectomy) | ||||||||

| Pneumonectomy | 17 | (9) | 0.77 | (0.28–2.16) | 0.6 | |||

| Bilobectomy | 13 | (7) | 1.08 | (0.36–3.26) | 0.9 | |||

| R1 (vs R0) | 7 | (4) | 1.69 | (0.47–6.15) | 0.4 | |||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (vs no) | 27 | (14) | 0.64 | (0.29–1.24) | 0.3 | |||

| Postoperative radiotherapy (vs no) | 82 | (43) | 3.25 | (1.95–5.42) | <0.001 | * | ||

| Tumor bed size (per 1-cm increase) | 1.05 | (0.95–1.15) | 0.3 | |||||

| Viable tumor size (per 1-cm increase) | 1.17 | (1.05–1.30) | 0.005 | * | ||||

| ypN (vs ypN0) | ||||||||

| N1a | 36 | (19) | 1.07 | (0.45–2.54) | 0.9 | 1.08 | (0.46–2.55) | 0.9 |

| N1b | 5 | (3) | 4.24 | (1.16–15.44) | 0.029 | 4.40 | (1.35–14.36) | 0.014 |

| N2a | 58 | (30) | 2.18 | (1.12–4.26) | 0.023 | 2.03 | (1.03–4.00) | 0.042 |

| N2b | 32 | (17) | 3.34 | (1.57–7.14) | 0.002 | 2.88 | (1.32–6.27) | 0.008 |

| ypStage based on tumor bed size (vs I) | ||||||||

| II | 54 | (28) | 1.52 | (0.60–3.87) | 0.4 | |||

| III | 105 | (55) | 2.51 | (1.08–5.84) | 0.033 | * | ||

| ypStage based on viable tumor size (vs III) | ||||||||

| 0 | 1 | (1) | 0.00 | (0.00–0.00) | <0.001 | * | ||

| I | 54 | (28) | 0.42 | (0.21–0.82) | 0.012 | * | ||

| II | 42 | (22) | 0.67 | (0.36–1.23) | 0.2 | |||

| High grade (vs low-intermediate) | 114 | (59) | 0.76 | (0.46–1.24) | 0.3 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion (vs absent) | 141 | (73) | 1.59 | (0.88–2.88) | 0.12 | |||

| Pleural invasion (vs PL0) | ||||||||

| PL1/2 | 40 | (21) | 1.35 | (0.77–2.39) | 0.3 | |||

| PL3 | 6 | (3) | 0.40 | (0.07–2.44) | 0.3 | |||

| Gene alteration (vs wild-type) (n=173) | ||||||||

| EGFR | 15 | (9) | 0.92 | (0.38–2.25) | 0.9 | |||

| KRAS | 56 | (32) | 0.98 | (0.56–1.71) | 0.9 | |||

| No MPR (vs MPR#) | 169 | (88) | 2.28 | (0.83–6.21) | 0.11 | |||

| Viable tumor >65% (vs ≤65%‡) | 72 | (38) | 2.04 | (1.24–3.34) | 0.005 | 1.77 | (1.05–2.98) | 0.033 |

| Necrosis (vs <5%‡) | ||||||||

| 5%–10% | 29 | (15) | 1.56 | (0.80–3.02) | 0.2 | |||

| ≥10% | 44 | (23) | 1.06 | (0.57–1.96) | 0.9 | |||

| Stroma >25% (vs ≤25%‡) | 125 | (65) | 0.53 | (0.32–0.87) | 0.012 | * | ||

| Inflammation >5% (vs ≤5%‡) | 118 | (61) | 0.42 | (0.26–0.69) | 0.001 | * | ||

| Fibrosis >29% (vs ≤29%‡) | 82 | (43) | 0.60 | (0.36–0.99) | 0.046 | * | ||

| Fibroelastotic scar (vs absent) | 101 | (53) | 0.88 | (0.54–1.45) | 0.6 | |||

| Hyalinization (vs absent) | 50 | (26) | 0.97 | (0.55–1.71) | 0.9 | |||

| Reactive giant cells (vs absent) | 107 | (56) | 1.12 | (0.68–1.86) | 0.7 | |||

| Cholesterol clefts (vs absent) | 96 | (50) | 0.76 | (0.46–1.24) | 0.3 | |||

| Foamy macrophages (vs absent) | 83 | (43) | 0.77 | (0.47–1.27) | 0.3 | |||

| Calcification (vs absent) | 48 | (25) | 0.77 | (0.41–1.43) | 0.4 | |||

NOTE. CI, confidence interval; MPR, major pathologic response; SHR, subhazard ratio.

Not included in final multivariable model owing to the association with percentage of viable tumor or ypN status.

Major pathologic response was defined as percentage of viable tumor ≤10%.

Cutoff values were determined using maximally selected rank statistics.

Supplementary Tables S3, S4, and S5 show the results of univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses for OS, competing regression analyses for CIR, and Cox regression analyses for DFS, respectively. In the final multivariable model for OS, similar to the case for LC-CID, percentage of viable tumor >65% was associated with higher risk of overall death (hazard ratio [HR], 1.56 [95% CI, 1.01–2.42]; P=0.050), independently of ypN status. ypN status was an independent risk factor for CIR and DFS on multivariable analysis; percentage of viable tumor was not significantly associated with either.

Univariable and Multivariable Analyses in Patients in SCC

Table 3 shows the results of univariable and multivariable competing-risk regression analyses for LC-CID in patients with SCC. In the final multivariable model, percentage of viable tumor >10% was associated with higher LC-CID (SHR, 9.41 [95% CI, 1.17–75.66]; P=0.035). Owing to their significant association with ypN status and/or percentage of viable tumor, other tumor stage–related variables (cStage, ypStage, tumor size) and histologic variables (necrosis, stromal tissue, inflammation, fibrosis, cholesterol cleft) were not included in the final multivariable model. In addition, owing to its significant association with percentage of viable tumor, lymphovascular invasion was not included in the final multivariable model.

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable competing risk regression analysis for lung cancer-specific death in patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma (N=80)

| Risk factor for lung cancer-specific death | N | (%) | Univariable analysis | Final multivariable model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR | 95% CI | P | SHR | 95% CI | P | |||

| Age (per 1-year increase) | 0.97 | (0.93–1.02) | 0.2 | |||||

| Male sex (vs female) | 54 | (68) | 1.10 | (0.47–2.58) | 0.8 | |||

| Smoking status (vs never) | ||||||||

| Former | 64 | (80) | 0.35 | (0.03–4.72) | 0.4 | |||

| Current | 14 | (18) | 0.43 | (0.03–6.58) | 0.5 | |||

| Pack-years (per 1-pack-year increase) | 1.00 | (0.98–1.01) | 0.6 | |||||

| cStage III (vs II) | 55 | (69) | 0.59 | (0.26–1.34) | 0.2 | |||

| Resection type (vs lobectomy) | ||||||||

| Pneumonectomy | 19 | (24) | 1.02 | (0.40–2.60) | 1 | |||

| Bilobectomy | 8 | (10) | 0.91 | (0.23–3.62) | 0.9 | |||

| R1 (vs R0) | 2 | (3) | 1.30 | (0.34–4.95) | 0.7 | |||

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (vs no) | 7 | (9) | 1.57 | (0.51–4.82) | 0.4 | |||

| Postoperative radiotherapy (vs no) | 15 | (19) | 1.82 | (0.80–4.13) | 0.15 | |||

| Tumor bed size (per 1-cm increase) | 1.07 | (0.97–1.18) | 0.2 | |||||

| Viable tumor size (per 1-cm increase) | 1.11 | (0.98–1.25) | 0.093 | * | ||||

| ypN (vs N0) | ||||||||

| N1a | 16 | (20) | 2.48 | (0.87–7.07) | 0.089 | 1.87 | (0.65–5.36) | 0.2 |

| N1b | 3 | (4) | 4.61 | (0.85–24.86) | 0.076 | 2.75 | (0.49–15.42) | 0.2 |

| N2a | 17 | (21) | 1.93 | (0.67–5.57) | 0.2 | 1.51 | (0.51–4.48) | 0.5 |

| N2b | 4 | (5) | 2.71 | (0.60–12.15) | 0.2 | 1.62 | (0.35–7.46) | 0.5 |

| ypStage based on tumor bed size (vs I) | ||||||||

| II | 20 | (25) | 2.58 | (0.62–10.66) | 0.2 | |||

| III | 35 | (44) | 4.02 | (1.12–14.45) | 0.033 | |||

| ypStage based on viable tumor size (vs III) | ||||||||

| 0 | 1 | (1) | 0.00 | (0.00–1.00) | 0.001 | * | ||

| I | 32 | (40) | 0.35 | (0.10–1.15) | 0.084 | |||

| II | 25 | (31) | 1.57 | (0.67–3.68) | 0.3 | |||

| Subtype (vs keratinizing)† | ||||||||

| Nonkeratinizing | 26 | (33) | 0.34 | (0.11–1.06) | 0.062 | |||

| Basaloid | 3 | (4) | 0.82 | (0.14–4.65) | 0.8 | |||

| Lymphovascular invasion (vs absent) | 43 | (54) | 5.84 | (1.91–17.83) | 0.002 | * | ||

| Pleural invasion (vs PL0) | ||||||||

| PL1/2 | 9 | (11) | 1.26 | (0.35–4.56) | 0.7 | |||

| PL3 | 2 | (3) | 1.60 | (0.27–9.60) | 0.6 | |||

| Viable tumor >10% (vs ≤10%‡#) | 59 | (74) | 11.29 | (1.49–85.78) | 0.019 | 9.41 | (1.17–75.66) | 0.035 |

| Necrosis ≥5% (vs <5%‡) | 55 | (69) | 3.57 | (1.03–12.33) | 0.045 | * | ||

| Stroma >65% (vs ≤65%‡) | 22 | (28) | 0.19 | (0.04–0.83) | 0.027 | * | ||

| Inflammation >12% (vs ≤12%‡) | 23 | (29) | 0.42 | (0.14–1.25) | 0.12 | |||

| Fibrosis >55% (vs ≤55%‡) | 18 | (23) | 0.24 | (0.05–1.07) | 0.061 | * | ||

| Fibroelastotic scar (vs absent) | 32 | (40) | 0.91 | (0.42–1.99) | 0.8 | |||

| Hyalinization (vs absent) | 39 | (49) | 0.97 | (0.44–2.16) | 0.9 | |||

| Reactive giant cells (vs absent) | 44 | (55) | 0.52 | (0.23–1.15) | 0.11 | |||

| Cholesterol clefts (vs absent) | 41 | (51) | 0.38 | (0.17–0.88) | 0.023 | * | ||

| Foamy macrophages (vs absent) | 38 | (48) | 1.58 | (0.71–3.54) | 0.3 | |||

| Calcification (vs absent) | 12 | (15) | 0.80 | (0.23–2.76) | 0.7 | |||

NOTE. CI, confidence interval; MPR, major pathologic response; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SHR, subhazard ratio.

Not included in final multivariable model owing to association with percentage of viable tumor or ypN status.

Subtype was not evaluated in 4 patients without residual tumor; therefore this variable was not included in the multivariable analysis.

Major pathologic response was defined as percentage of viable tumor ≤10%.

Cutoff values were determined by maximally selected rank statistics.

Supplementary Tables S6, S7, and S8 show the results of univariable multivariable Cox regression analyses for OS, competing regression analyses for recurrence, and Cox regression analyses for DFS, respectively. ypN status was an independent risk factor for OS, recurrence, and DFS on multivariable analysis; percentage of viable tumor was not significantly associated with any outcome.

Discussion

Our comprehensive histologic assessment of clinical stage II-III lung NSCLC following NAC demonstrated that the pathologic features and the cut-offs for pathologic response to predict favorable outcomes differ significantly between ADC and SCC. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to investigate pathologic response following NAC (Supplementary Table S1) and the first to comprehensively assess pathologic response separately in ADC and SCC. Our significant findings are as follows: (1) MPR (≤10% viable tumor) predicted survival in the overall (ADC + SCC) and SCC cohorts, thus validating its use for these patients; (2) however, MPR (≤10% viable tumor) was not significantly associated with survival in the ADC cohort; and (3) the optimal cutoff for predicting lung cancer–specific death differed between histologic types—10% in SCC and 65% in ADC—and these cutoffs independently stratified patients by prognosis in multivariable analyses.

Pataer and colleagues investigated 192 NSCLC tumors following NAC and 166 NSCLC tumors that did not undergo preoperative treatment: ≤10% viable tumor was observed only in tumors treated with NAC.5 Assessing the association between percentage of viable tumor (10%−20% increments) and hazard of overall death, the authors demonstrated that, among the 192 patients who underwent NAC followed by surgery, ≤10% viable tumor was significantly associated with reduced hazard of overall death, compared with >10% viable tumor.5 On multivariable analysis, percentage of viable tumor was an independent predictor of OS and DFS as both a continuous5 and dichotomized variable (≤10% vs >10% viable tumor) in a follow-up report using the same cohort.35 In a prospective trial of NAC with bevacizumab in patients with nonsquamous NSCLC, the association between pathologic response and patient survival was investigated to determine whether MPR (≤10% viable tumor) could serve as a surrogate endpoint. Of 41 resected patients, 11 (27%) had MPR, and these patients had significantly better OS (MPR vs no MPR: 3-year OS, 100% vs 49%).2 On the basis of these and other results, MPR (≥90% pathologic response or ≤10% viable tumor) was proposed as a surrogate endpoint for predicting survival following NAC in patients with resectable NSCLC.1

The results of the present study, using a large retrospective series of patients with ADC and SCC, validate the prognostic value of MPR. However, we found that the optimal cutoff percentage of viable tumor differed between ADC and SCC. In patients with ADC, the risk of lung cancer–specific death remained largely the same from very low viable tumor (≤5%) up to 65% viable tumor (Figure 3A). The finding that a significantly improved prognosis appears to occur at the 35% level, instead of 90% as previously stipulated, has major implications for the prognosis of patient outcomes and for the design of future clinical trials of NAC.36 This also has bearing on how pathologists should assess resected specimens in the NAC setting—the current recommendations from both the College of American Pathologists and the Royal College of Pathologists use 10% as the threshold for viable tumor37, 38 or complete response.38 According to the results of our study, there is value in assessing the percentage of viable tumor in 5%−10% increments, rather than with a fixed threshold of 10%, which appears to be appropriate for SCC but not ADC.

Mouillet and colleagues investigated the prognostic value of pathologic complete response (pCR; 0% viable tumor) following NAC in patients with cStage IB-II NSCLC across two phase III trials. They found that pCR was independently associated with better OS and DFS.18 Of importance, pCR was strongly associated with SCC histologic type (13% of patients with SCC had pCR vs 3% of patients with non-SCC NSCLC). In addition, SCC histologic type was associated with better OS, independently of pCR.18 Liao and colleagues conducted a prospective trial to investigate the efficacy of NAC for c-stage III N2 NSCLC and made similar findings (28% of patients with SCC had pCR vs 5% of patients with non-SCC NSCLC, and SCC was an independent predictor of better DFS).17 Moreover, a review of the literature reveals the incidence of MPR following NAC increases with a higher percentage of patients with SCC among the study population (Supplementary Figure S9). These findings suggest that SCC is associated with better pathologic response and, subsequently, better survival following NAC, compared with ADC, and they further suggest a potential need for a differential interpretation of pathologic response on the basic of histologic type.

The present study included 22 patients with ADC who underwent NAC with bevacizumab followed by surgery and adjuvant bevacizumab in the above mentioned phase II trial.2 Consistent with the previously reported findings, MPR (≤10% viable tumor) was significantly associated with better LC-CID, compared with no MPR (Supplementary Figure S10). The finding that the 10% threshold appears to be significant for bevacizumab but not for the other chemotherapy agents used to treat the majority of patients with ADC raises the possibility that the clinically relevant thresholds for pathologic response may also vary by type of neoadjuvant therapy administered. We also checked the effect of mutational status on the optimal cutoff of 65%; this value was not driven by specific mutational status (Supplementary Figure S11). As additional forms of preoperative therapy are increasingly being used, including various forms of molecular targeted therapy and immunotherapy, it is possible that similar careful evaluation of pathologic responses may be needed for each therapeutic intervention, as well as for histologic type, to determine optimal cutoff values.

The limitations of the present study include its retrospective design, with the inherent potential selection bias between SCC and ADC cohorts; this might have affected our results. In addition, the SCC cohort was relatively small. Another limitation of the retrospective nature of this study was that we could review only available slides processed in a routine fashion for surgically resected specimens. We were not able to apply our current method of comprehensive histologic sampling of resected neoadjuvant lung cancers using a mapping technique with sampling of all small (≤3 cm) tumors and a cross-section of larger tumors. It is anticipated that such an approach will be included in future recommendations from the IASLC pathology panel.39

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that pathologic response following NAC and subsequent survival outcomes differ between histologic types of NSCLC. MPR (≤10% viable tumor) predicts better survival in patients with SCC; however, in patients with ADC, the optimal cutoff percentage of viable tumor may be higher than 10%. These findings have major implications for the pathologic assessment of resected specimens, for the prognosis of patient outcomes and for patient management in the NAC setting, and for the design of future clinical trials. Prospective studies designed to determine the prognostic importance of percentage of viable tumor between ADC and SCC separately, and according to different neoadjuvant treatment modalities, are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Joe Dycoco of the MSK Thoracic Surgery Service for his help with the Thoracic Service lung cancer database and David Sewell of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Thoracic Surgery Service for editorial assistance.

Funding Support

P.S.A.’s laboratory work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA217169, R01CA236615, and P30 CA008748), the U.S. Department of Defense (BC132124, LC160212, and CA170630), the Joanne and John DallePezze Foundation, the Derfner Foundation, and the Mr. William H. Goodwin and Alice Goodwin, the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research, and the Experimental Therapeutics Center of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: J.E.C. has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Merck, Genentech, and BMS and research funding from AstraZeneca, Genentech, and BMS. M.G.K. has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, and Regeneron. W.D.T. has served in a nonpaid consulting role for Genentech. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hellmann MD, Chaft JE, William WN Jr., et al. Pathological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable non-small-cell lung cancers: proposal for the use of major pathological response as a surrogate endpoint. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:e42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaft JE, Rusch V, Ginsberg MS, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant bevacizumab plus chemotherapy and adjuvant bevacizumab in patients with resectable nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:1084–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Junker K, Langner K, Klinke F, et al. Grading of tumor regression in non-small cell lung cancer : morphology and prognosis. Chest 2001;120:1584–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Junker K, Thomas M, Schulmann K, et al. Tumour regression in non-small-cell lung cancer following neoadjuvant therapy. Histological assessment. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1997;123:469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pataer A, Kalhor N, Correa AM, et al. Histopathologic Response Criteria Predict Survival of Patients with Resected Lung Cancer After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2012;7:825–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefani A, Alifano M, Bobbio A, et al. Which patients should be operated on after induction chemotherapy for N2 non-small cell lung cancer? Analysis of a 7-year experience in 175 patients. J Thorac Cardiov Sur 2010;140:356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Li ZN, Yu LC, et al. Association of expression of MRP1, BCRP, LRP and ERCC1 with outcome of patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Lung Cancer 2010;69:116–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee HY, Lee HJ, Kim YT, et al. Value of combined interpretation of computed tomography response and positron emission tomography response for prediction of prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scagliotti G, Hanna N, Fossella F, et al. The differential efficacy of pemetrexed according to NSCLC histology: a review of two Phase III studies. Oncologist 2009;14:253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strizzi L, Catalano A, Vianale G, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is an autocrine growth factor in human malignant mesothelioma. J Pathol 2001;193:468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2542–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009;361:947–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appel S, Goldstein J, Perelman M, et al. Neo-adjuvant Chemo-Radiation to 60 Gray Followed by Surgery for Locally Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients: Evaluation of Trimodality Strategy. Isr Med Assoc J 2017;19:614–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Betticher DC, Hsu Schmitz SF, Totsch M, et al. Mediastinal lymph node clearance after docetaxel-cisplatin neoadjuvant chemotherapy is prognostic of survival in patients with stage IIIA pN2 non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1752–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betticher DC, Hsu Schmitz SF, Totsch M, et al. Prognostic factors affecting long-term outcomes in patients with resected stage IIIA pN2 non-small-cell lung cancer: 5-year follow-up of a phase II study. Br J Cancer 2006;94:1099–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coroller TP, Agrawal V, Huynh E, et al. Radiomic-Based Pathological Response Prediction from Primary Tumors and Lymph Nodes in NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:467–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao WY, Chen JH, Wu M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with docetaxel-cisplatin in patients with stage III N2 non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2013;14:418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mouillet G, Monnet E, Milleron B, et al. Pathologic complete response to preoperative chemotherapy predicts cure in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: combined analysis of two IFCT randomized trials. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pottgen C, Stuschke M, Graupner B, et al. Prognostic model for long-term survival of locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy and resection integrating clinical and histopathologic factors. BMC Cancer 2015;15:363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Remark R, Lupo A, Alifano M, et al. Immune contexture and histological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy predict clinical outcome of lung cancer patients. Oncoimmunology 2016;5:e1255394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas M, Rube C, Hoffknecht P, et al. Effect of preoperative chemoradiation in addition to preoperative chemotherapy: a randomised trial in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncology 2008;9:636–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamane Y, Ishii G, Goto K, et al. A novel histopathological evaluation method predicting the outcome of non-small cell lung cancer treated by neoadjuvant therapy: the prognostic importance of the area of residual tumor. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ofek E, Sato M, Saito T, et al. Restrictive allograft syndrome post lung transplantation is characterized by pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis. Modern Pathol 2013;26:350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amin MB, Springer, 2016 Cancer. AJCo: AJCC Cancer Staging manual (ed 8th). New York: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travis WD, Asamura H, Bankier AA, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Coding T Categories for Subsolid Nodules and Assessment of Tumor Size in Part-Solid Tumors in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification of Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Travis WD, et al. Lung cancer - major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:138–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lausen B, Sauerbrei W, Schumacher V. Classification and regression trees (CART) used for the exploration of prognostic factors measured on different scales. Contr Stat 1994:483–496. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bland JM, Altman DG. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Statistical methods in medical research 1999;8:135–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hristov B, Eguchi T, Bains S, et al. Minimally Invasive Lobectomy Is Associated With Lower Noncancer-specific Mortality in Elderly Patients: A Propensity Score Matched Competing Risks Analysis. Ann Surg 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan KS, Eguchi T, Adusumilli PS. Competing risks and cancer-specific mortality: why it matters. Oncotarget 2018;9:7272–7273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eguchi T, Bains S, Lee MC, et al. Impact of Increasing Age on Cause-Specific Mortality and Morbidity in Patients With Stage I Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Competing Risks Analysis. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:281–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gray RJ. A Class of K-Sample Tests for Comparing the Cumulative Incidence of a Competing Risk. Ann Stat 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 35.William WN Jr., Pataer A, Kalhor N, et al. Computed tomography RECIST assessment of histopathologic response and prediction of survival in patients with resectable non-small-cell lung cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:222–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng H, Zeltsman M, Zauderer MG, et al. Chemotherapy-induced immunomodulation in non-small-cell lung cancer: a rationale for combination chemoimmunotherapy. Immunotherapy 2017;9:913–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butnor KJB MB; Dacic S; Berman M; Flieder D; Jones K; Okby NT; Roggli VL; Suster S; Tazelaar HD; Travis WD Protocol for the Examination of Specimens From Patients With Primary Non-Small Cell Carcinoma, Small Cell Carcinoma, or Carcinoid Tumor of the Lung, College of American Pathologists. Available at http://www.cap.org/ShowProperty?nodePath=/UCMCon/Contribution%20Folders/WebContent/pdf/cp-lung-17protocol-4000.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2018 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Nicholson AK K; Gosney J Dataset for lung cancer histopathology reports, The Royal College of Pathologists. Available at https://www.rcpath.org/resourceLibrary/g048-lungdataset-sep16-pdf.html. Accessed August 6, 2018 2018.

- 39.Blumenthal GM, Bunn PA Jr., Chaft JE, et al. Current Status and Future Perspectives on Neoadjuvant Therapy in Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.