Abstract

Purpose:

To compare the efficacy of topical 5-fluorouracil 1% (5FU) and interferon alfa-2b 1 MIU/mL (IFN) eye drops as primary treatment modalities for ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN).

Design:

Retrospective, comparative, interventional case series.

Methods:

Fifty-four patients who received 5FU and 48 patients who received IFN as primary therapy for OSSN were included. Primary outcome measures were the frequency of clinical resolution and time to OSSN recurrence by treatment modality. Secondary outcome was the frequency of side effects with each therapy.

Results:

The mean age of patients was 68 years. More Hispanics were treated with 5FU. In a univariable analysis, frequency of OSSN resolution was higher with 5FU (96.3%, n = 52) than with IFN (81.3%, n = 39), p=0.01. In a multivariable analysis, treatment modality did not remain a significant predictor of resolution. In patients whose OSSN resolved, time to resolution was similar with both agents, (5FU - mean 6.6 months, standard deviation (SD) 4.5 versus IFN - mean 5.5 months, SD 2.9, p = 0.17). Of the 52 eyes whose OSSN resolved with 5FU, 11.5 % of lesions (n=6) recurred while of the 39 eyes whose OSSN resolved with IFN, 5.1% of lesions (n = 2) recurred, p=0.46. Kaplan Meier survival curves of OSSN recurrence were similar between groups (log rank=0.16). One-year recurrence rates were 11.4% with 5FU and 4.5% with IFN. Eyelid edema (p=0.04) and tearing (p=0.02) were more significant with 5FU.

Conclusions:

This is the first direct comparison study between 5FU and IFN eye drops as primary treatment modalities for OSSN. Both modalities resulted in a high frequency of tumor resolution and low recurrence rates and are effective treatment options for OSSN.

Introduction

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) is the most common malignancy of the ocular surface.1 It comprises a spectrum of epithelial squamous conditions ranging from dysplasia to invasive carcinoma.2 The strongest risk factors for OSSN include prior history of OSSN, ultraviolet light exposure, prior skin cancer, older age and male gender.3,4 Less strongly associated factors include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human papilloma virus (HPV), and smoking.4,5

Historically, surgical excision using a no-touch technique with adjuvant alcohol and cryotherapy has been the gold standard of treatment for OSSN.6 Surgical excision is often both diagnostic and therapeutic and allows for rapid resolution of lesions.3,7,8 However, there is often subclinical microscopic disease beyond the excised lesion that is not completely addressed, and this can lead to recurrence frequencies as high as 56%.9,10 Surgery can also lead to sequelae such as conjunctival hyperemia, conjunctival scarring and limbal stem cell deficiency.11

Medical management of OSSN has been gaining increasing momentum as the primary therapy for OSSN.12,13 Topical chemotherapeutic agents have the ability to treat the entire ocular surface, which is beneficial in addressing microscopic subclinical disease as well as recurrent and multifocal lesions.14 These agents can be employed as primary treatment or as adjuvant therapy to surgical excision. However, with topical agents there are often longer resolution times and increased out of pocket costs for patients. Associated adverse effects and patient compliance can also limit use.11

The chemotherapeutic agents employed for treatment include interferon alfa-2b (IFN), 5-fluorouracil (5FU), and mitomycin C (MMC). IFN is an endogenous glycoprotein released by various immune cells with antiviral, antimicrobial and antineoplastic activities that is used in recombinant form.15 5-FU is an antimetabolite that inhibits the action of thymidylate synthase, therefore interrupting the synthesis of nucleosides used for DNA formation.16 MMC is an alkylating agent that acts in all phases of the cell cycle and inhibits RNA and protein synthesis.17 All of these agents, despite their differing mechanisms of action, have been shown to be effective in the treatment of OSSN, with varying resolution rates.11,18–20

Several studies have retrospectively reviewed the efficacy of these agents in the primary treatment of OSSN.11 One study compared topical IFN and MMC and found similar response frequencies between both agents (89% IFN and 92% MMC, p=0.67) with shorter resolution times with MMC (1.5 months MMC versus 3.5 months IFN, p <0.005).21 Another study compared IFN therapy to surgical excision and found comparable recurrence rates (3% at 1 year with IFN vs 5% at 1 year with surgery, p =0.80) with the most common complication being mild discomfort in both groups.3 A gap in the literature, however, is a head-to-head comparison between 5FU and IFN as primary treatment modalities for OSSN. As such, the primary purpose of this research study was to compare the efficacy and safety of topical 5FU and IFN as primary treatment modalities for OSSN.

Methods

Study population:

The institutional review board of the University of Miami approved this retrospective study, and the methods adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and were compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. A pharmacy database was used to identify all patients with OSSN that were treated with either topical 5FU or IFN as primary treatment modalities for OSSN at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute between January 2013 and July 2016 (n=346). Retrospective chart reviews were conducted. Patients were excluded if either agent was used as adjuvant surgical therapy, if IFN was administered as a peri-lesional injection, if treatment was not completed, if patients were lost to follow-up, if patients were still in active treatment, or if patients were not primarily managed at our institution. This left 54 patients who received 5-FU as the primary treatment modality and 48 patients who received IFN topically as the primary treatment modality for OSSN for final analysis.

Topical 5 FU:

All patients were treated with topical 5FU at a concentration of 1%. The drops were administered four times daily for one week, followed by a drug holiday for three weeks. This monthly cycle was continued until clinical resolution, after which the drops were discontinued. Patients were initially seen on a two-month basis to assess treatment response.

Topical IFN:

All patients were treated with topical IFN at a concentration of 1 MIU/mL. The drops were administered four times daily continuously without any cessation of therapy. Patients were initially seen on a two-month basis to assess treatment response.

Data extracted:

Patient records were reviewed for demographic information (age, gender, race, ethnicity) and OSSN risk factors (history of skin cancer, HPV, HIV, smoking, sun exposure - defined as patient subjectively noting to spend a large quantity of time outdoors, presence of pterygium or prior pterygium surgery, and prior history of OSSN). Characteristics of the current lesion were also documented including the involved eye, tumor location, tumor size and involved ocular structures (conjunctiva, cornea, limbus, orbit), uni- vs. multi-focality, and appearance (leukoplakic, gelatinous, papillomatous, flat/opalescent) based on descriptions and photographs. The tumor size and location provided the basis for American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) clinical stage of the tumor.22 Of the 24 patients that underwent biopsy, pathologic grading of the tumor (mild, moderate, or severe carcinoma in situ or invasive squamous cell carcinoma) and margin positivity were also recorded. Treatment information documented included the primary modality of treatment, and for medical therapy included the dose, frequency, and length of treatment.

Main outcome measures:

The main outcome measures were the frequency of clinical resolution and time to OSSN recurrence with each treatment modality. A secondary outcome was the frequency of side effects.

Response information was recorded in terms of time to complete resolution of the lesion (defined as disappearance of the lesion clinically and/or by anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT). Not all patients had AS-OCT imaging in both groups. Recurrence was defined as a reappearance of a lesion, either in the same or similar location as the original tumor or on any part of the ocular surface, after complete resolution of the original tumor. Follow up was carried out from the time of clinical resolution of the lesion until the last visit. Documented complications included those volunteered by the patient as well as those elicited by the examiner during the clinic visit; no formal survey was used. The presence of side effects was assessed at each visit and recorded by one author (CLK). Specifically, patients were asked about pain, redness, lid swelling, light sensitivity, tearing, itching, and blurred vision. Side effects evaluated for on examination included hyperemia, keratopathy and limbal stem cell deficiency.

Statistical analyses:

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) statistical package. Frequencies of demographic and clinical variables were calculated for each group. Categorical variables were compared using a Chi square analysis or Fisher exact test as appropriate; continuous variables were compared using the student t-test. Time-to-event curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Logistic regression analysis was employed to evaluate factors associated with disease resolution. Cox proportional hazards analysis was employed to evaluate factors associated with disease recurrence. Forward stepwise multivariable analyses were conducted to adjust for potential confounders for primary outcome measures.

Results:

Demographics:

Demographics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients affected with OSSN were white males in their late 60s. There was a higher number of patients of Hispanic ethnicity in the 5FU compared to the INF group, p = 0.04. More tumors were located in the inferior bulbar conjunctiva in the 5FU compared to the IFN group (38.9% vs 18.8%, p=0.03). Mean follow-up was 15.8 months, standard deviation (SD) 9.7 in the 5FU group and 20.9 months, SD 13.3 in the IFN group (p=0.03).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical information of patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia treated with 5-fluorouracil or Interferon alfa 2b eye drops

| Demographic and clinical factors | 5-fluorouracil (n=54) mean (SD) | Interferon alfa-2b (n=48) mean (SD) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 70.0 (12) | 65.0 (14) | 0.09 |

| Gender | |||

| Male gender | 74.1 (40) | 60.4 (29) | 0.20 |

| Race | 0.26 | ||

| White | 70.0 (35) | 70.5 (31) | |

| Black | 10.0 (5) | 2.3 (1) | |

| Other | 20 (10) | 27.3 (12) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 70.6 (36) | 48.9 (22) | 0.04 |

| Current smoker | 9.6 (5) | 11.4 (5) | 0.56 |

| Sun exposure | 87.5 (21) | 75.0 (21) | 0.31 |

| History of pterygium | 22.4 (11) | 21.3 (10) | 0.82 |

| History of OSSN | 20.4 (11) | 12.5 (6) | 0.41 |

| History of skin cancer | 25.0 (10) | 37.8 (14) | 0.33 |

| History of HIV | 2.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.34 |

| History of HPV | 10.8 (4) | 9.7 (3) | 1.00 |

| Area (mm2) | |||

| 47.9 (62.1) | 44.5 (38.1) | 0.74 | |

| Locationa | |||

| Nasal | 51.9 (28) | 54.2 (26) | 0.85 |

| Temporal | 42.6 (23) | 60.4 (29) | 0.08 |

| Superior | 16.7 (9) | 16.7 (8) | 1.00 |

| Inferior | 38.9 (21) | 18.8 (9) | 0.03 |

| Corneal involvement | 79.6 (43) | 75.0 (36) | 0.64 |

| Corneal and conjunctival involvement | 48.1 (26) | 66.7 (32) | 0.08 |

| AJCC clinical stageb | 0.14 | ||

| T1a | 20.8 (11) | 12.8 (6) | |

| T2a | 18.9 (10) | 17.0 (8) | |

| T2b | 11.3 (6) | 2.1 (1) | |

| T3a | 49.1 (26) | 68.1 (12) | |

| Appearancec | |||

| Leukoplakia | 25.9 (14) | 27.7 (13) | 1.00 |

| Papillomatous | 22.2 (12) | 21.3 (10) | 1.00 |

| Gelatinous | 38.9 (21) | 42.6 (20) | 0.84 |

| Flat/Opalescent | 50.0 (27) | 31.9 (15) | 0.07 |

| Pathologic graded | n=13 | n=11 | 1.00 |

| CIS (mild-severe dysplasia) | 24.1 | 22.9 | |

| SCC | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

Data are no. (%) unless otherwise indicated

Tumors could involve more than 1 quadrant; for example, a tumor involving the superior and temporal bulbar conjunctiva would appear in both the superior and temporal location categories.

- Sun exposure was defined as patient noting to spend a large quantity of time outdoors

AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer clinical stage

Tumors could have more than 1 descriptor for appearance

CIS = Carcinoma in situ; SCC = Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Pathologic grade was determined only for biopsied specimens, n =24

Frequency of resolution of OSSN between 5FU therapy and IFN therapy:

Of the 54 eyes treated with 5FU, 96.3% of lesions (n=52) completely resolved (median number of cycles was 4, range 2 to 12, mean 4.2, SD 1.9). Of the 48 eyes treated with IFN therapy, 81.3% of lesions (n = 39) completely resolved (median number of months treated 4, range 2 to 8, mean 4.2, SD 1.5). The difference in frequency of response to each treatment was statistically significant (p=0.01) by univariable analysis.

To evaluate and adjust for potential confounders between the two treatment groups, a multivariable analysis was performed that considered the effects of demographics and tumor characteristics on clinical resolution. While the univariable analysis showed significant superiority of 5FU in clinical resolution (96.3% vs 81.3% p=0.01), the multivariable analysis did not show a significant difference in resolution rates between the two treatments. The only factor found to predict clinical resolution was ethnicity. Patients of Hispanic ethnicity were 7.7 times more likely to respond to medical therapy (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 38.8, p = 0.01) compared to non-Hispanics.

Time to resolution of OSSN between 5FU therapy and IFN therapy:

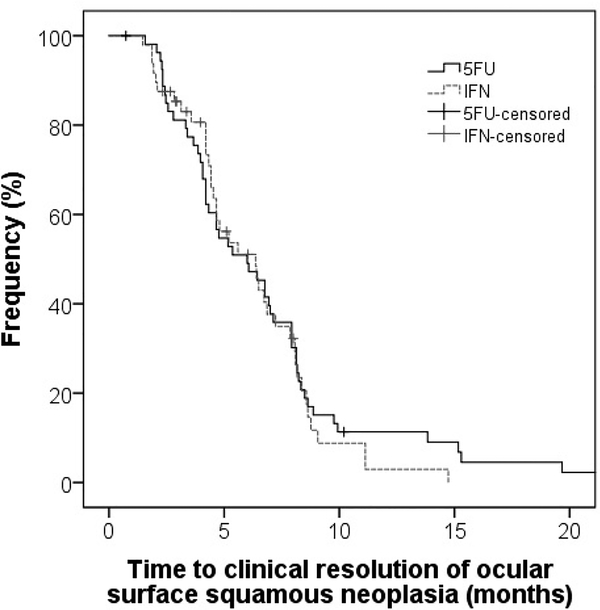

Of the lesions that resolved completely with 5FU and IFN therapy, there was no statistically significant difference in the time to resolution between the two agents (5FU – mean 6.6 months, SD 4.5; IFN – mean 5.5 months, SD 2.9; log rank = 0.62). (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Kaplan-Meyer survival curve: time to clinical resolution.

Kaplan-Meyer survival curve showing differences in time to clinical resolution of OSSN after treatment with 5FU and IFN.

Treatment failures:

Two of 54 patients failed treatment with 5FU of which both were treated for two cycles. One was switched to IFN for three additional cycles and the other to MMC for two cycles. Both patients had resolution of their tumor after the switch of therapy.

Nine of 48 patients failed treatment with IFN after being treated between two to seven months. All nine were subsequently switched to 5FU. Six patients responded the 5FU while three needed additional therapy. Of these, two patients were then switched to MMC and one underwent surgical excision. All patients had complete resolution of their lesions with these alternative therapies.

Recurrences after treatment:

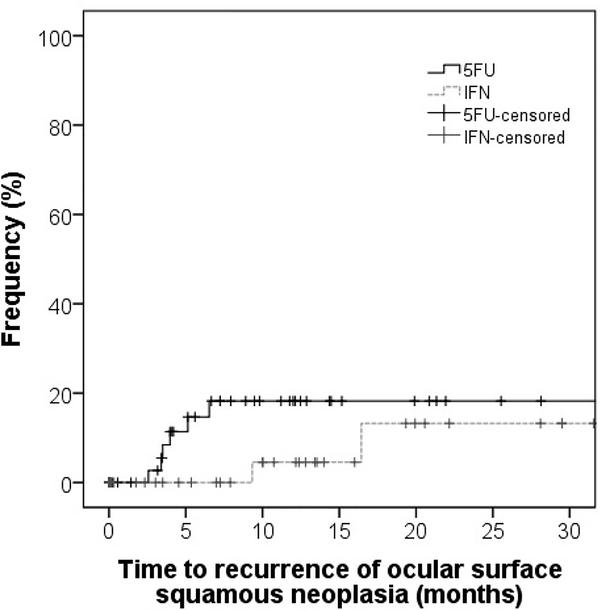

Of the 52 eyes whose OSSN resolved with 5FU therapy, 11.5 % of lesions (n=6) recurred after a mean of 7.7 months, SD 9.1. Of the 39 eyes whose OSSN resolved with IFN therapy, 5.1% of lesions (n = 2) recurred after a mean of 9.9 months, SD 11.4, p=0.46 for frequency of recurrence. With Kaplan Meier survival analysis, at 1 year, recurrence was 11.4% in the 5FU group and 4.5% in the IFN group (log rank = 0.16). (Figure 2). There was no significant difference in frequency of recurrence or time to recurrence by multivariable analysis of demographic factors, tumor characteristics or treatment method.

Figure 2 – Kaplan-Meyer survival curve: time to recurrence.

Kaplan-Meyer survival curve showing differences in time to recurrence of OSSN after treatment with 5FU and IFN.

Treatment side effects:

There were no long-term complications associated with the use of 5FU or IFN. With 5FU, the common side effects were pain (n=12, 22.2%), tearing (n=12, 22.2%), redness (n=11, 20.4%), eyelid edema (n=5, 9.3%) and keratopathy (n=4, 7.4%). Common side effects with IFN also included pain (n=9, 19.6%), redness (n=6, 13.0%) and blurred vision (n=6, 13.0%). Tearing (5FU 22.2% vs IFN 4.3%, p=0.02) and eyelid edema (5FU 9.3% vs IFN 0%, p= 0.04) were notably more common in the 5FU group than the IFN group. One patient stopped 5FU therapy due to eyelid pain. There were no cases of eyelid edema or keratopathy in the IFN group. Limbal stem cell deficiency was not seen in either the 5FU or IFN treatment groups.

Discussion

To conclude, our study showed that both 5FU and IFN were viable and effective treatment modalities for OSSN, with a high frequency of clinical resolution and low recurrence rate in both groups. Topical 5FU was first reported for the treatment of premalignant lesions of the cornea, conjunctiva and eyelid in 1986.23 Since then, several studies encompassing 129 individuals evaluated 5FU for as a primary agent for OSSN, with a high frequency of resolution (average 91%, range 82–100%).18,24–27 Our 96% frequency of resolution fits well within this range. Our cycle parameters (mean of 4 cycles, 7 days on, 21 days off) are also within the reported range of 5FU being used for 2 to 7 days followed by a 30 to 45 day holiday (range of 1 to 6.5 cycles). Our study represents the largest cohort of patients treated with 5FU (n=54) in the literature with a cycled protocol. Recurrences in our and other studies were low, with a range of 0 to 28%, all of which occurred in the first year.24,25,27 Benefits of 5FU are its low cost (approximately $37 per cycle. Downsides include its side effects, most commonly ocular pain, and lid inflammation, but these are generally manageable, and only 1 individual in our cohort stopped therapy due to ocular pain.

Topical IFN is another commonly used therapy for OSSN, first described in the late 1990s.28–30 Since then, several studies encompassing 332 individuals have evaluated its use as a primary agent in OSSN, again with a high frequency of resolution (average 95%, range 75 to 100%). Similar to 5FU, recurrences were uncommon (range 4–20%) and most occurred in the first year.3,20,28,29,31–37 Our 81% frequency of resolution fits well within this range. Most studies, including ours, used a concentration of 1 million IU/mL administered 4 times daily for a time period of a few months (range 2 to 6 months). Others have used a higher concentration (3 million IU/ml) with one study reporting a 100% resolution frequency after 2 months with no recurrences during a mean 10.2 month follow-up using this higher concentration.31 Other studies, however, found no significant differences in efficacy by IFN concentrations.38,33 An advantage of IFN is its gentleness. A downside of treatment is its cost (approximately $500 dollars per month in the US), need for continuous treatment, and requirement for refrigeration. In addition, some patients, such as those with immunosuppression in the setting of a hematologic malignancy, may do better with 5FU than IFN.39 Perilesional injections of IFN (not included in this study) have been associated with a flu-like syndrome.40

Another treatment modality for OSSN is MMC, first reported in 1994.41 Ten studies, encompassing 212 patients, found an average 90% resolution frequency with MMC.19,35,42–49 In our cohort, MMC was used in 3 patients as a salvage therapy after failure of OSSN to respond to either 5FU or IFN. All 3 patients had clinical resolution after an average of 2 cycles of MMC administered in a cyclical fashion (7 days on, 14 days off). MMC costs approximately $300 dollars per bottle in the US and has a higher frequency of side effects (pain, punctal stenosis and limbal stem cell deficiency) compared to 5FU and IFN.50

In our study, the diagnosis of OSSN was made primarily by clinical examination with AS-OCT imaging used as an adjuvant modality given the distinctive and reproducible features that identify this condition.51 We have previously found that AS-OCT has a high sensitivity (range 94–100%) and specificity (100%) for the diagnosis of OSSN as compared histopathologic diagnosis.52,53

The largest limitation of our study is its retrospective nature. Our two treatment groups were not identical but were sufficiently similar to allow comparisons of efficacy and recurrence rates. It is interesting to note that Hispanics responded more favorably to treatment than non-Hispanics in our cohort. The reasons for this are unclear. As with all studies, unmeasured confounders could have affected our data such as tumor genetics and host immune response. Furthermore, we did not have pathologic grading in all patients, but in the ones available, there were no differences between the groups.

Other limitations included a non-standardized method for evaluating side effects and treatment compliance and a lack of information on out of pocket patient costs. A strength of our study is that there were no systemic biases in choosing treatment modality by demographic or tumor characteristics. We offer all patients both treatments and a final decision is based on other factors (cost, frequency of administration), allowing us to study efficacy in this paper. Ultimately, a prospective study comparing 5FU and IFN will be needed to further validate our retrospective results.

Despite these limitations, our study, with a large cohort of over 100 patients, showed that topical 5FU 1% eye drop is comparable in efficacy to IFN in the treatment of OSSN. Both modalities resulted in a high frequency of tumor resolution and low recurrence rates. The final message from this study is that 5FU, like IFN, is a viable option in the treatment of OSSN.

Acknowledgements

a. Funding/Support: This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Clinical Sciences Research EPID-006-15S (Dr. Galor), R01EY026174 (Dr. Galor), NIH Center Core Grant P30EY014801 and Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant, Dr. Ronald Lepke Grant, The Lee and Claire Hager Grant, The Jimmy and Gaye Bryan Grant, The H. Scott Huizenga Grant, The Grant and Diana Stanton-Thornbrough Grant, The Robert Baer Family Grant, The Emilyn Page and Mark Feldberg Grant, The Gordon Charitable Foundation, The Richard and Kathy Lesser Grant, The Jose Ferreira de Melo Grant and The Richard Azar Family Grant (institutional grants).

Footnotes

b. Financial Disclosures: All authors have no financial disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shields CL, Demirci H, Karatza E, Shields JA. Clinical survey of 1643 melanocytic and nonmelanocytic conjunctival tumors. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(9):1747–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee GA, Hirst LW. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39(6):429–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nanji AA, Moon CS, Galor A, Sein J, Oellers P, Karp CL. Surgical versus medical treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a comparison of recurrences and complications. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):994–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClellan AJ, McClellan AL, Pezon CF, Karp CL, Feuer W, Galor A. Epidemiology of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia in a Veterans Affairs Population. Cornea. 2013;32(10):1354–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott IU, Karp CL, Nuovo GJ. Human papillomavirus 16 and 18 expression in conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(3):542–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shields JA, Shields CL, De Potter P. Surgical management of conjunctival tumors. The 1994 Lynn B. McMahan Lecture. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(6):808–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peksayar G, Altan-Yaycioglu R, Onal S. Excision and cryosurgery in the treatment of conjunctival malignant epithelial tumours. Eye (Lond) 2003;17(2):228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li AS, Shih CY, Rosen L, Steiner A, Milman T, Udell IJ. Recurrence of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia Treated With Excisional Biopsy and Cryotherapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(2):213–219.e211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erie JC, Campbell RJ, Liesegang TJ. Conjunctival and corneal intraepithelial and invasive neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 1986;93(2):176–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabin G, Levin S, Snibson G, Loughnan M, Taylor H. Late recurrences and the necessity for long-term follow-up in corneal and conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(3):485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nanji AA, Sayyad FE, Karp CL. Topical chemotherapy for ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013;24(4):336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adler E, Turner JR, Stone DU. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a survey of changes in the standard of care from 2003 to 2012. Cornea. 2013;32(12):1558–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone DU, Butt AL, Chodosh J. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a standard of care survey. Cornea. 2005;24(3):297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayed-Ahmed IO, Palioura S, Galor A, Karp CL. Diagnosis and Medical Management of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2017;12(1):11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron S, Tyring SK, Fleischmann WR, Jr., et al. The interferons. Mechanisms of action and clinical applications. JAMA. 1991;266(10):1375–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraham LM, Selva D, Casson R, Leibovitch I. The clinical applications of fluorouracil in ophthalmic practice. Drugs 2007;67(2):237–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abraham LM, Selva D, Casson R, Leibovitch I. Mitomycin: clinical applications in ophthalmic practice. Drugs 2006;66(3):321–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parrozzani R, Frizziero L, Trainiti S, et al. Topical 1% 5-fluoruracil as a sole treatment of corneoconjunctival ocular surface squamous neoplasia: long-term study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(8):1094–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frucht-Pery J, Sugar J, Baum J, et al. Mitomycin C treatment for conjunctival-corneal intraepithelial neoplasia: a multicenter experience. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(12):2085–2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusumesh R, Ambastha A, Sinha B, Kumar R. Topical Interferon alpha-2b as a Single Therapy for Primary Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2015;4(5):279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kusumesh R, Ambastha A, Kumar S, Sinha BP, Imam N. Retrospective Comparative Study of Topical Interferon alpha2b Versus Mitomycin C for Primary Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Cornea. 2017;36(3):327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Keizer RJ, de Wolff-Rouendaal D, van Delft JL. Topical application of 5-fluorouracil in premalignant lesions of cornea, conjunctiva and eyelid. Doc Ophthalmol 1986;64(1):31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeatts RP, Engelbrecht NE, Curry CD, Ford JG, Walter KA. 5-Fluorouracil for the treatment of intraepithelial neoplasia of the conjunctiva and cornea. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(12):2190–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Barrag A, Al-Shaer M, Al-Matary N, Al-Hamdani M. 5-Fluorouracil for the treatment of intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva, and cornea. Clin Ophthalmol 2010;4:801–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parrozzani R, Lazzarini D, Alemany-Rubio E, Urban F, Midena E. Topical 1% 5-fluorouracil in ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a long-term safety study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(3):355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joag MG, Sise A, Murillo JC, et al. Topical 5-Fluorouracil 1% as Primary Treatment for Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(7):1442–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu FR, Wu MJ, Kuo SH. Interferon treatment for corneolimbal squamous dysplasia. American journal of ophthalmology. 1998;125(1):118–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vann RR, Karp CL. Perilesional and topical interferon alfa-2b for conjunctival and corneal neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(1):91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maskin SL. Regression of limbal epithelial dysplasia with topical interferon. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112(9):1145–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zarei-Ghanavati S, Alizadeh R, Deng SX. Topical interferon alpha-2b for treatment of noninvasive ocular surface squamous neoplasia with 360 degrees limbal involvement. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2014;9(4):423–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah SU, Kaliki S, Kim HJ, Lally SE, Shields JA, Shields CL. Topical interferon alfa-2b for management of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in 23 cases: outcomes based on American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(2):159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sturges A, Butt AL, Lai JE, Chodosh J. Topical interferon or surgical excision for the management of primary ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1297–1302, 1302e1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shields CL, Kaliki S, Kim HJ, et al. Interferon for ocular surface squamous neoplasia in 81 cases: outcomes based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. Cornea. 2013;32(3):248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Besley J, Pappalardo J, Lee GA, Hirst LW, Vincent SJ. Risk factors for ocular surface squamous neoplasia recurrence after treatment with topical mitomycin C and interferon alpha-2b. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(2):287–293.e282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kusumesh R, Ambastha A, Sinha B, Kumar R. Topical Interferon alpha-2b as a Single Therapy for Primary Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schechter BA, Koreishi AF, Karp CL, Feuer W. Long-term follow-up of conjunctival and corneal intraepithelial neoplasia treated with topical interferon alfa-2b. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1291–1296, 1296.e1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galor A, Karp CL, Chhabra S, Barnes S, Alfonso EC. Topical interferon alpha 2b eye-drops for treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a dose comparison study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(5):551–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashkenazy N, Karp CL, Wang G, Acosta CM, Galor A. Immunosuppression as a Possible Risk Factor for Interferon Nonresponse in Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Cornea. 2017;36(4):506–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poothullil AM, Colby KA. Topical medical therapies for ocular surface tumors. Semin Ophthalmol. 2006;21(3):161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frucht-Pery J, Rozenman Y. Mitomycin C therapy for corneal intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117(2):164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papandroudis AA, Dimitrakos SA, Stangos NT. Mitomycin C therapy for conjunctival-corneal intraepithelial neoplasia. Cornea. 2002;21(7):715–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tseng SH, Tsai YY, Chen FK. Successful treatment of recurrent corneal intraepithelial neoplasia with topical mitomycin C. Cornea. 1997;16(5):595–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen C, Louis D, Dodd T, Muecke J. Mitomycin C as an adjunct in the treatment of localised ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88(1):17–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta A, Muecke J. Treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia with Mitomycin C. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(5):555–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heigle TJ, Stulting RD, Palay DA. Treatment of recurrent conjunctival epithelial neoplasia with topical mitomycin C. American journal of ophthalmology. 1997;124(3):397–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rozenman Y, Frucht-Pery J. Treatment of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia with topical drops of mitomycin C. Cornea. 2000;19(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shields CL, Naseripour M, Shields JA. Topical mitomycin C for extensive, recurrent conjunctival-corneal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(5):601–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson MW, Hungerford JL, George SM, Madreperla SA. Topical mitomycin C for the treatment of conjunctival and corneal epithelial dysplasia and neoplasia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124(3):303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russell HC, Chadha V, Lockington D, Kemp EG. Topical mitomycin C chemotherapy in the management of ocular surface neoplasia: a 10-year review of treatment outcomes and complications. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(10):1316–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas BJ, Galor A, Nanji AA, et al. Ultra high-resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis and management of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ocul Surf. 2014;12(1):46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kieval JZ, Karp CL, Abou Shousha M, et al. Ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography for differentiation of ocular surface squamous neoplasia and pterygia. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(3):481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nanji AA, Sayyad FE, Galor A, Dubovy S, Karp CL. High-Resolution Optical Coherence Tomography as an Adjunctive Tool in the Diagnosis of Corneal and Conjunctival Pathology. Ocul Surf 2015;13(3):226–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]