Abstract

Hippocampus-dependent learning processes are coordinated via a large diversity of GABAergic inhibitory mechanisms. The α5 subunit-containing GABAA receptor (α5-GABAAR) is abundantly expressed in the hippocampus populating primarily the extrasynaptic domain of CA1 pyramidal cells, where it mediates tonic inhibitory conductance and may cause functional deficits in synaptic plasticity and hippocampus-dependent memory. However, little is known about synaptic expression of the α5-GABAAR and, accordingly, its location site-specific function. We examined the cell- and synapse-specific distribution of the α5-GABAAR in the CA1 stratum oriens/alveus (O/A) using a combination of immunohistochemistry, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings and optogenetic stimulation in hippocampal slices obtained from mice of either sex. In addition, the input-specific role of the α5-GABAAR in spatial learning and anxiety-related behavior was studied using behavioral testing and chemogenetic manipulations. We demonstrate that α5-GABAAR is preferentially targeted to the inhibitory synapses made by the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP)- and calretinin-positive terminals onto dendrites of somatostatin-expressing interneurons. In contrast, synapses made by the parvalbumin-positive inhibitory inputs to O/A interneurons showed no or little α5-GABAAR. Inhibiting the α5-GABAAR in control mice in vivo improved spatial learning but also induced anxiety-like behavior. Inhibiting the α5-GABAAR in mice with inactivated CA1 VIP input could still improve spatial learning and was not associated with anxiety. Together, these data indicate that the α5-GABAAR-mediated phasic inhibition via VIP input to interneurons plays a predominant role in the regulation of anxiety while the α5-GABAAR tonic inhibition via this subunit may control spatial learning.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT The α5-GABAAR subunit exhibits high expression in the hippocampus, and regulates the induction of synaptic plasticity and the hippocampus-dependent mnemonic processes. In CA1 principal cells, this subunit occupies mostly extrasynaptic sites and mediates tonic inhibition. Here, we provide evidence that, in CA1 somatostatin-expressing interneurons, the α5-GABAAR subunit is targeted to synapses formed by the VIP- and calretinin-expressing inputs, and plays a specific role in the regulation of anxiety-like behavior.

Keywords: GABAA receptor, inhibition, interneuron, somatostatin, synapse, VIP

Introduction

How brain receives and processes information depends largely on the state and distribution of GABAergic inhibitory mechanisms that operate within central circuits. GABAergic inhibition is mostly achieved via ionotropic GABAA receptors (GABAARs) that can be expressed at synaptic sites and mediate fast synaptic inhibition as well as at extrasynaptic sites and activate tonic inhibition. GABAAR is a pentamer, which comprises two α (α1-6), two β (β1-3), and one gamma (γ1-3) subunits (Baumann et al., 2001; Klausberger et al., 2001; Sieghart and Sperk, 2002). In the hippocampus, the α5 GABAA receptor subunit (α5-GABAAR) exhibits a particularly abundant expression (Sperk et al., 1997), reaching ∼25% of hippocampal GABAARs (Wisden et al., 1992; Sur et al., 1998; Pirker et al., 2000) by postnatal day 30 (Yu et al., 2006). For decades, the α5-GABAAR remained one of the most interesting pharmacological targets because blocking this subunit improves the hippocampus-dependent memory, the effect largely attributed to the elimination of tonic inhibition. In addition, the α5-GABAAR is strongly recruited by general anesthetics causing persistent memory deficits (Caraiscos et al., 2004; Saab et al., 2010; Zurek et al., 2012, 2014). However, the improved cognitive performance by the α5-GABAAR-specific inhibitors came at a price of increased anxiety after the drug administration indicating that the α5-GABAAR is involved in anxiolytic effects (Navarro et al., 2002; Behlke et al., 2016; Mohler and Rudolph, 2017), and therefore requiring further investigations into the expression patterns and site-specific functions of this subunit.

Current data indicate that, in hippocampal pyramidal cells, the α5-GABAAR subunit is mainly expressed at extrasynaptic sites (Fritschy et al., 1998; Brünig et al., 2002; Christie et al., 2002; Crestani et al., 2002), where it mediates tonic inhibition (Pirker et al., 2000; Caraiscos et al., 2004; Glykys and Mody, 2006; Serwanski et al., 2006). The membrane anchorage of the α5-GABAAR is regulated through phosphorylation of radixin (Rdx), a cytoskeletal protein that is responsible for the α5-GABAAR membrane site-specific location (Loebrich et al., 2006; Hausrat et al., 2015). In addition, this subunit has been found at inhibitory synapses, where it contributes to phasic inhibition (Ali and Thomson, 2008; Zarnowska et al., 2009; Salesse et al., 2011; Schultz et al., 2018). Activation of the α5-GABAAR at inhibitory synapses onto oriens–lacunosum moleculare cells (OLMs) generates kinetically slow inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs). Consistently, removal of the α5-GABAAR facilitates the firing and the recruitment of these cells to network activity (Salesse et al., 2011). The OLM cells receive local inhibitory inputs from the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and calretinin (CR)-coexpressing type 3 interneuron-specific interneurons (IS3; Acsády et al., 1996; Chamberland et al., 2010; Tyan et al., 2014) and parvalbumin (PV)-positive cells (Lovett-Barron et al., 2012). Whether the α5-GABAAR is expressed at all inhibitory synapses converging onto a given interneuron or is targeted to a specific postsynaptic location remains unknown. As synapse-specific subunit trafficking could provide the means for pointed pharmacological interventions, here we used three optogenetic mouse models, in which a light-sensitive protein Channelrhodopsin 2 (ChR2) was expressed in different populations of hippocampal CA1 interneurons to identify the type of synapse expressing the α5-GABAAR subunit. We provide evidence that the α5-GABAAR is targeted to synapses formed by the VIP- and CR-expressing inputs on different types of somatostatin (SOM)-expressing interneurons. Furthermore, the synapse-specific expression of the α5-GABAAR in interneurons could control the anxiety-like behavior, whereas tonic inhibition of principal cells through this subunit is likely responsible for coordination of spatial learning.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Experiments were performed on heterozygous and homozygous CR-IRES-Cre mice [B6(Cg)-Calb2tm1(cre)Zjh/J; The Jackson Laboratory, stock #10774], VIP-IRES-Cre mice [Viptm1(cre)Zjh/J; The Jackson Laboratory, stock #10908], and Vip-Cre;Ai9 mice obtained by breeding the VIP-Cre mice with the reporter line Ai9-(RCL-tdTomato) [B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J; The Jackson Laboratory, stock #007909], PV-Cre mice [B6;129P2-Pvalbtm1(cre)Arbr/J; The Jackson Laboratory, stock #8069], Gabra5 knock-out mice (Gabra5−/−; Merck/Sharp and Dohme), and wild-type C57BL/6 mice of both sexes maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to rodent diet. For behavioral testing, 4- to 6-month-old animals were used. For some electrophysiological experiments, VIP-IRES-Cre homozygous mice were bred with Ai32 [Ai32(RCL-ChR2(H134R)/EYFP)] homozygous mice [B6;129S-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm32(CAG-COP4*H134R/EYFP)Hze/J; The Jackson Laboratory, stock #12569]. The Université Laval Animal Protection Committee approved all animal experiments.

Stereotaxic surgery.

The Cre-dependent pAAV-Ef1a-DIO-ChR2:mCherry plasmid was provided by K. Deisseroth (Stanford University, USA) and the Cre-dependent pAAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di:mCherry DNA plasmid was provided by B. Roth (University of North Carolina, USA). Viruses were produced at the University of North Carolina Vector Core facility. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (10 mg · kg−1) and secured in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments). After incision, the skull was exposed and two drill holes/hemisphere were made at the following coordinates from bregma: AP −2.0 mm, ML ±1.6 mm, DV −1.3 mm, and AP −2.5 mm, ML ±2.1 mm, DV −1.3 mm. A glass micropipette containing the viral solution and connected to the Nanoinjector (Word Precision Instruments) was used for injections (100 nl) into each site at a rate of 1 nl · s−1. Control mice were injected with the same volume of control virus (pAAV-hSyn-DIO-mCherry). After 5 min, the pipette was retracted and the incision was closed with sterile suture.

Patch-clamp electrophysiology, optogenetics, and pharmacogenetics in vitro.

Following at least 3 weeks after viral injection, acute hippocampal slices were prepared for in vitro electrophysiology recordings. Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, and the brains were quickly removed into ice-cold sucrose cutting solution (in mm: 219 sucrose, 2 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 7 MgSO4, 0.5 CaCl2, and 10 glucose) continuously aerated with carbogen gas mixture (5% CO2, 95% O2). Transversal 300-μm-thick hippocampal slices were cut using a Microm vibratome (Fisher Scientific) in ice-cold cutting solution and transferred to recovery artificial CSF (ACSF; in mm: 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 3 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2, and 10 glucose; mOsm/L 295, pH 7.4 when aerated with carbogen) for 30 min at 33–37°C. They were kept in the same carbogen-aerated solution at room temperature for at least 1 h before recordings. The recording chamber was perfused with carbogenated 32°C recording ACSF (in mm: 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 2 MgSO4, 2CaCl2, and 10 glucose; mOsm/L 295–300, pH 7.4) at a rate of 1.5–2 ml/min. Hippocampal CA1 oriens/alveus (O/A) interneurons were identified using a Zeiss AxioScope microscope with DIC-IR and 40×/0.8N.A objective, and hM4D(Gi)-expressing interneurons were identified by mCherry expression. Patch pipettes had 4–5 MΩ resistance when filled with intracellular solution (in mm: 130 CsMeSO4, 2 CsCl, 10 diNa-phosphocreatine, 10 HEPES, 2 ATP-Tris, 0.2 GTP-Tris, 0.3% biocytin, 2 QX-314, pH 7.2–7.3, 280–290 mOsm/L). Resting membrane potential was measured immediately after forming whole-cell configuration at a holding current of 0 pA. Cell input resistance was calculated from hyperpolarizing current steps (5 mV/200 ms) applied from the resting membrane potential, and recordings were rejected if the access resistance exceeded 30 MΩ. IPSCs were evoked by optical activation of ChR2-expressing terminals with 5 ms pulses of blue light (up to 10 mW optic power; filter set, 450–490 nm) using a wide-field stimulation through microscope objective. The same energy light pulses did not elicit any activity in O/A interneurons from mice not expressing ChR2. Synaptic latency was measured as the time between the onset of blue-light pulse and the onset of synaptic current. Currents were elicited at 20–30 s intervals between successive trials, filtered at 2–3 kHz (MultiClamp 700B amplifier), digitized at 10 kHz (Digidata 1440A, Molecular Devices) and acquired by pCLAMP10 software (Molecular Devices).

To test the effect of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) on hM4D(Gi) and mCherry-expressing cells, CNO (10 μm) was applied via perfusion system. Spiking was recorded in whole-cell current-clamp configuration before, during and after CNO administration. The recording patch-pipette was filled with intracellular solution (in mm: 130 KMeSO4, 2 MgCl2, 10 diNa-phosphocreatine, 10 HEPES, 2 ATP-Tris, 0.2 GTP-Tris, and 0.3% biocytin (Sigma-Aldrich), pH 7.2–7.3, 280–290 mOsm/L), and spikes were recorded at −45 mV holding potential.

Behavior.

To evaluate hippocampus-dependent spatial learning, we used a water T-maze test (WTM; Rönnbäck et al., 2011; Michaud et al., 2012; Guariglia and Chadman, 2013; Peckford et al., 2013; Spink et al., 2014), in which animals were placed at the stem of a water-filled T-maze and allowed to swim until they could find a submerged platform located in one of the arms. The T-maze (length of stem: 64 cm, length of arms: 30 cm, width: 12 cm, height of walls: 16 cm) was made of clear Plexiglas and filled with water (23 ± 1°C) at the height of 12 cm. A platform (11 × 11 cm) was submerged 1 cm below water level at the end of the target arm. The VIPCre, VIPCre; Ai9 and VIPCre; Ai32 mice were used for all behavior experiments. Mice were handled daily for 3 d before the experiment and trained to find a platform in water-filled T-maze during four trials for 1d. Each mouse swam until it found the hidden platform, after which it was allowed to rest on the platform for 15 s. If the mouse had not found the platform after 60 s, it was gently guided to the platform and stayed there for 30 s before being returned to the cage. On the day of the experiment, each animal was tested in two blocks of eight trials with a 4 h inter-block interval. On the following day, the same protocol was repeated except that the mice were trained to find the new location of the escape platform on the opposite side. The escape time was monitored with a chronometer. Mice exhibiting aberrant behavior, such as corkscrew swimming or floating were removed from further analysis (Weitzner et al., 2015). Depending on the experiment, the AAV-hM4Di-injected mice were receiving CNO (1 mg/kg, i.p.; Tocris Bioscience), L-655,708 (0.5 mg/kg, i.p., Tocris Bioscience) or both. In control experiments, naive mice received saline (0.9% NaCl) injections (see Fig. 7A), or mice injected stereotaxically with a control vector (pAAV-hSyn-DIO-mCherry) received intraperitoneal saline injections (see Figs. 6A,E, 7B–F). All intraperitoneal injections were performed 30 min before the beginning of the behavioral test.

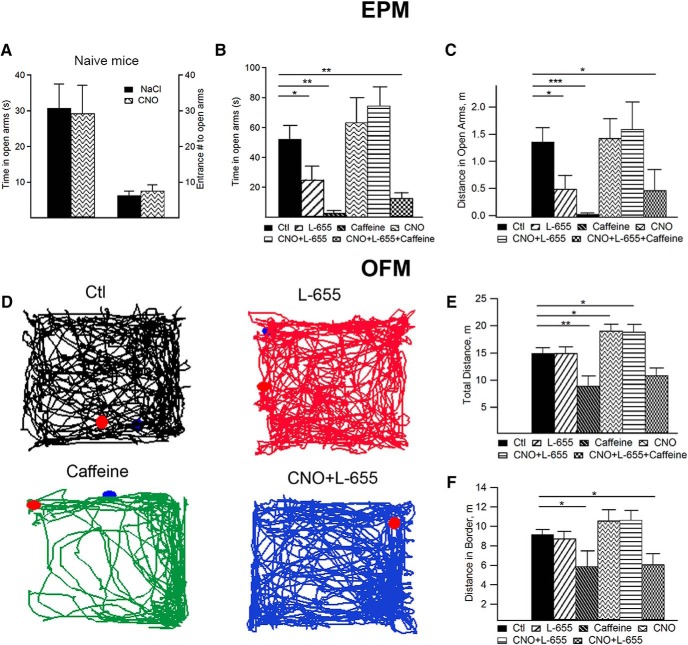

Figure 7.

The α5-GABAAR-containing VIP+ synapses are involved in the modulation of anxiety. A–C, Summary bar graphs showing the time spent in open arms (A, B) and distance in open arms (A, C) upon administration of saline and CNO in naive mice (A; n = 8 mice/group) as well as control virus-injected mice receiving saline (n = 8) or hDM4Gi-injected mice receiving L,655–708 (n = 8), CNO (n = 9), caffeine (n = 7), CNO+L-655,708 (n = 9), and CNO+L-655,708+caffeine (n = 7). A, The administration of saline and CNO on naive mice showed no difference in anxiety (p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA/Mann–Whitney test). B, C, Inhibition of α5-GABAAR subunit alone increased the anxiety with less time spent by mice in the open arms and decreased activity in the open arms (B, C; p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test). D, Representative locomotion tracks for saline- (black), L-655,708- (red), caffeine- (green), and CNO+L-655,708- (blue) receiving mice, showing decreased locomotor and increased thigmotactic behavior in caffeine-treated mice. E, F, Summary bar graphs showing the total distance (E) and distance in periphery (F; border) for mice receiving saline, L,655–708, caffeine, CNO, combination of CNO and L-655,708, and combination of CNO, L-655,708 and caffeine (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; unpaired t test).

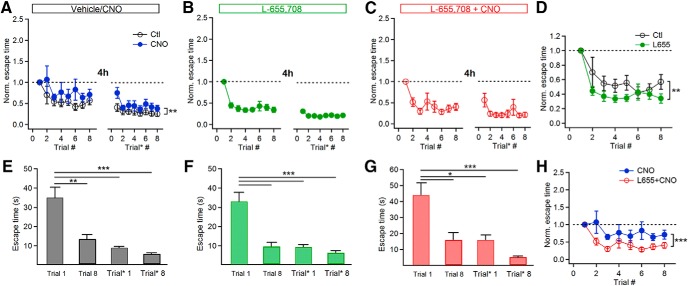

Figure 6.

Spatial memory impaired through inactivation of VIP interneurons is rescued by L-655,708 administration. A–C, Summary plots showing the normalized escape time as a function of the trial number in the WTM test in Ctl- or hDM4Gi-injected mice under different experimental conditions: (A, E) vehicle (black; control-virus injected mice, n = 14, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) or CNO (blue; hDM4Gi mice, n = 9); (B, F) L-655,708 (green; hDM4Gi-injected mice, n = 13, ***p < 0.001); (C, G) L-655,708 administered on top of CNO (red; hDM4Gi mice, n = 9, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001). Note that chemogenetic inactivation of VIP+ interneurons was associated with a poor performance during acquisition learning and the 4 h retention phase (A, H; **p < 0.01 compared with Ctl mice; one-way ANOVA/ Kruskal–Wallis test). Administering the L-655,708 alone shortened escape time during the acquisition phase in hDM4Gi-injected mice (B, D, F; **p < 0.01 compared with Ctl mice; one-way ANOVA/Holm–Sidak test), and rescued the impaired retention when combined with CNO (H; ***p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA/Holm–Sidak test).

For the anxiety test, the elevated plus maze (EPM) was used. The maze was made of beige Plexiglas and consisted of four arms (30 × 5 cm) elevated 40 cm above floor level. Two of the arms contained 15-cm-high walls (enclosed arms) and the other two none (open arms). Each mouse was placed in the middle section facing a close arm and left to explore the maze for 10 min. After each trial, the floor of the maze was wiped clean with EtOH 70% and dried. The open versus closed arm entries and duration of stay within each zone were recorded using the Any-Maze software. The test was run on the same day on naive (no surgery), control (stereotaxic control vector injection), and AAV-hM4Di-injected VIPCre, VIPCre; Ai9 and VIPCre; Ai32 mice that received saline (0.9% NaCl), CNO, L-655,708 or CNO+L-655,708. In some experiments, two separate groups of mice received caffeine (50 mg/kg, i.p.; Tocris Bioscience) alone or in combination with L-655,708 and CNO.

For the open-field maze (OFM) test (Walsh and Cummins, 1976; Seibenhener and Wooten, 2015), animals were allowed to freely explore the open-field arena (45 × 30 cm). The animal track and total distance were recorded using the ANY-maze video tracking system (Stoelting) and analyzed online for distance made on periphery versus total distance.

Immunohistochemistry.

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine and perfused transcardially with ice-cold sucrose followed by 4% paraformaldehyde and 20% picric acid in PBS. Brains were extracted, postfixed overnight, embedded in 4% agar, and sectioned (50 μm). Brain sections were treated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and incubated in the solution containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBS-Tri), 10% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and 4% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C in the solution containing 1% normal donkey serum, 4% bovine serum albumin and primary antibodies [1:300 rabbit Rdx, Abcam, ab52495; 1:200 rat SOM, Millipore, 2885355; 1:1000 mouse PV, Sigma-Aldrich, P3088; 1:3000 guinea pig α5-GABAAR, generous gift from Dr. Jean-Marc Fritschy (University of Zurich, Switzerland); 1:200 rabbit α5-GABAAR, Abcam, ab10098; 1:1000 goat CR, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-11644; 1:500 goat metabotropic glutamate receptor 1α (mGluR1α), Frontier Institute, Af1220; 1:500 mouse vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT), Synaptic Systems, 131011; 1:800 rabbit cholecystokinin (CCK), Sigma-Aldrich, C2581; 1:500 rabbit mCherry, BioVision, 5993-100]. The following day, sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated in different combinations of secondary antibodies (1:200 AlexaFluor 647 donkey anti-rabbit, ThermoFisher Scientific; 1:200 AlexaFluor 647 donkey anti-mouse, Life Technologies; 1:250 AlexaFluor 488 donkey anti-rat, Jackson ImmunoResearch; 1:200 FITC-conjugated, donkey anti-mouse, Jackson ImmunoResearch; 1:1000 AlexaFluor 488 donkey anti-goat, Jackson ImmunoResearch; 1:1000 Cy3 donkey anti-goat, Jackson ImmunoResearch; 1:1000 AlexaFluor 546 donkey anti-rabbit, ThermoFisher Scientific; 1:250 Dylight 650 donkey anti-goat, ThermoFisher Scientific) in blocking solution for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, sections were washed in PBS and mounted with Dako Fluorescence Mounting Medium for image acquisition. Quantification of immunolabeling was performed bilaterally on 6 sections per animal from three animals per condition. Images were collected using a 63× objective (NA 1.4) and a laser-scanning Leica SP5 confocal microscope. For colocalization analysis in single cells (Fig. 1A), z-series images were taken with a 1 μm step and counts were performed from maximal projection images generated in Leica LAS software. For colocalization analysis within dendrites and synaptic structures, z-series images were acquired with a 0.2 μm step, and synaptic boutons defined as small (0.8–1.5 μm) round structure coexpressing VGAT were counted manually using Leica LAS software. For dendritic expression analysis (Fig. 1B), the α5 puncta were only counted on the main dendrite, which was defined by the red mGluR1a staining. The dendrite-containing area was examined in individual focal plans (acquired with a step of 0.2 μm), and the α5 puncta overlapping with red mGluR1a signal were selected and then analyzed for colocalization with VGAT. The puncta outside the dendrite were not analyzed.

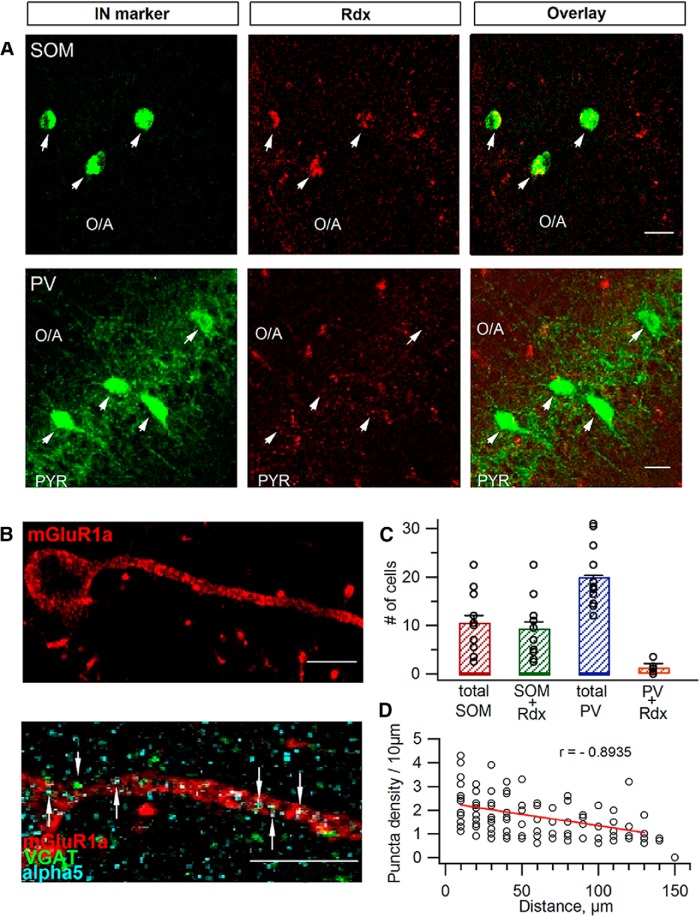

Figure 1.

Cell- and site-specific expression of Rdx and α5-GABAAR. A, Representative CA1 O/A images showing SOM, PV, and Rdx immunoreactivity in the mouse CA1 hippocampal area. Scale bars, 20 μm. B, Representative images showing α5-GABAAR and VGAT immunoreactivity in mGluR1a+ interneuron dendrite. White arrows point to the α5-GABAAR/VGAT puncta colocalizing within the mGluR1a+ dendrite and soma area. Scale bar, 10 μm. C, Summary bar graphs demonstrating the average number of SOM+ and PV+ cells examined within CA1 area per slice and the number of cells coexpressing Rdx. Individual data points correspond to the number of cells examined per slice. D, Quantification of the α5-GABAAR puncta density in the mGluR1a+ interneuron dendrite versus distance from soma (Pearson correlation: r = −0.8935 ± 0.01; n = 10 cells/3 mice). PYR, Pyramidal layer.

Colocalization patterns of VGAT with α5-GABAAR and VGAT with Rdx were compared between O/A and stratum radiatum (RAD) using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Images were first processed with LAS AF software using median filtering (median = 3; iterations = 2) to reduce the noise level. The quantitative analysis was then done using the ImageJ plugin “Colocalization threshold” on 8-bit.tiff files of the processed images. The entire O/A and RAD of the images were analyzed. This returned different coefficients: the thresholded Mander's for each channel (tM1 and tM2) and the Pearson's correlation (R). tM1 being the fraction of VGAT colocalizing with α5-GABAAR or Rdx and tM2 being the fraction of α5-GABAAR or Rdx colocalizing with VGAT. Although R quantifies both co-occurrence and correlation between the two signals, Mander's coefficients measure only co-occurrence (Dunn et al., 2011).

Slices containing the cells filled with biocytin were fixed in 4% PFA overnight, rinsed in phosphate buffer (PB) and kept at 4°C in PB-sodium azide (0.05%). Biocytin was revealed using Streptavidin-AlexaFluor-488 (1:200, Invitrogen) in whole 300 μm slices penetrated with 0.3% Triton in tris-buffered saline. Confocal z-series images of labeled cells were acquired using a 20× objective with a 1 μm step, loaded in Neurolucida software and reconstructed digitally (see Fig. 3).

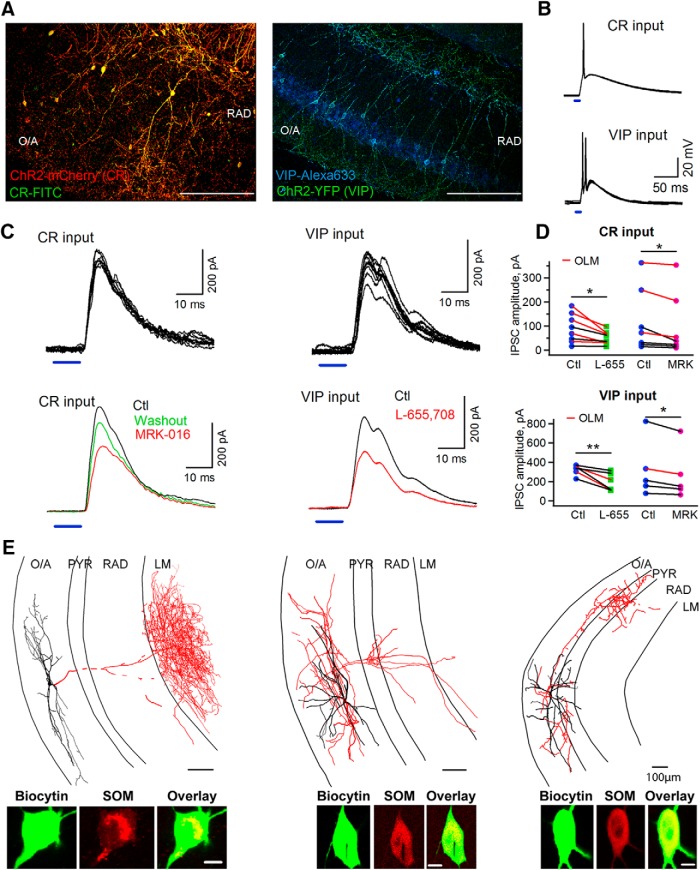

Figure 3.

CR+ and VIP+ interneurons make the α5-GABAAR-containing synapses on SOM+ interneurons. A, Representative confocal images from the hippocampal CA1 showing ChR2-mCherry expression (red) in CR-expressing interneurons (green) after injecting AAV2-DIO-ChR2:mCherry into the CA1 of a CRCre mouse (left) ChR2-YFP expression in the CA1 of a VIPCre:ChR2-YFP mouse (right). Scale bar, 100 μm. B, Action potentials evoked in CR (top) and VIP (bottom) interneurons in response to light stimulation indicated by blue bars. C, Representative individual (top) and average traces (bottom) of synaptic currents evoked in SOM+ interneurons by light stimulation of CR (left) or VIP (right) inputs as indicated by blue bars in control (black), in the presence of the α5-GABAAR subunit inverse agonists MRK-016 (100 nm; left) or L-655,708 (50 nm; right, red) and after the drug washout (green). D, Summary data showing the effects of the α5-GABAAR subunit inverse agonists (green and violet) on light-evoked synaptic currents for a group of cells. Red lines correspond to data obtained for OLM cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. E, Anatomical and neurochemical identification of SOM+ interneurons from which recordings were obtained. Representative examples of the Neurolucida reconstructions of recorded cells are shown on top and confocal images for biocytin and SOM immunolabeling are shown in the bottom to illustrate the three types of SOM+ interneurons: OLM cells (left), bistratified cells (middle), and projecting cells with an axon leaving the CA1 area and being truncated at the level of the CA3 (right). Scale bars, 10 μm.

Experimental design and statistical analysis.

Mice of either sex were randomly assigned to experimental groups, which were matched in terms of numbers of males and females in each group. The experimenters were blinded to the experimental groups during both data acquisition and analysis. In behavior experiments, 5 of 57 animals were excluded from data analysis because post hoc histological examination revealed no viral transduction as indicated by mCherry fluorescence. In addition, two mice were excluded from the behavior analysis because they showed severe alopecia in the past and abnormal behavior (Bechard et al., 2011). In optogenetic patch-clamp experiments, slices from four mice were excluded, because they showed no viral transduction. The following criteria were used for including the data from patch-clamp experiments: stable holding current, no significant change in Rser (<15%), and no run-down of the ChR2-evoked response during 10 min control recording period, before the drug application. Data were analyzed using Excel, IGOR Pro, Clampfit 10.2, Any-Maze, and ImageJ software. Figures were prepared using IGOR Pro and Adobe Illustrator CS5. For statistical analysis, distributions of the data were tested for normality using Shapiro–Wilcoxon test in Statistica and SigmaStat 4.0. Standard paired or unpaired t test, Mann–Whitney or one-way ANOVA (followed by Tukey, Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis, or Holm–Sidak tests, depending on the data distribution) were used. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Error bars correspond to SEM.

Results

Rdx and α5-GABAAR synaptic expression in SOM-interneurons

To investigate the cell-type-specific expression of the α5-GABAAR subunit within the hippocampal CA1 O/A, we first compared the expression of its anchoring protein Rdx (Loebrich et al., 2006; Hausrat et al., 2015) in interneurons that were immunopositive for PV or SOM. A substantial fraction of Rdx labeling was detected within SOM-immunoreactive (SOM+) interneurons (225/254 SOM+ cells, n = 24 slices/3 mice; Fig. 1A,C). Moreover, analysis of the subcellular localization of the α5-GABAAR in SOM+ interneurons coexpressing the metabotropic receptor 1a (mGluR1a), and thus corresponding to the OLM cells, revealed a higher density of the α5-GABAAR puncta in proximal versus distal dendrites (Pearson correlation: r = −0.8935 ± 0.01; n = 10 cells/3 mice; Fig. 1B,D). The latter was consistent with a spatial gradient in the synaptic VGAT distribution (r = −0.86 ± 0.02, n = 8 cells/3 mice; Pearson correlation), indicative of a distance-dependent decline in the number of inhibitory synapses in OLM cells. These data corroborate previous report on the presence of the α5-GABAAR in SOM/mGluR1a-coexpressing OLM cells (Salesse et al., 2011), and highlight the preferential dendritic distribution of this subunit. Only a small fraction of interneurons immunoreactive for PV (PV+) expressed Rdx (27/480 PV+ cells, n = 24 slices/3 mice; Fig. 1A,C).

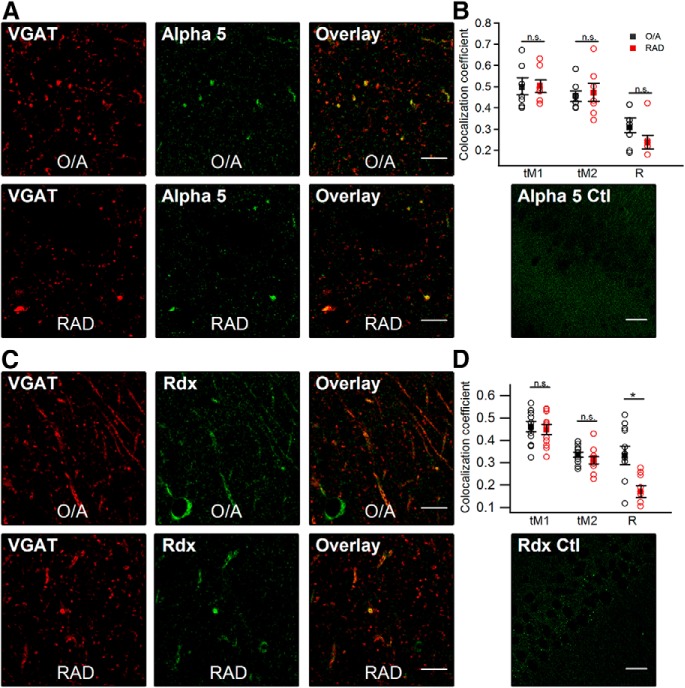

Additional analysis of Rdx and α5-GABAAR synaptic localization in relation to the VGAT within the CA1 O/A and RAD revealed overall similar patterns of expression (Fig. 2). Indeed, both Rdx and α5-GABAAR showed a significant colocalization with VGAT within O/A and RAD (α5-GABAAR: tM1 = 0.51 ± 0.03; tM2 = 0.47 ± 0.04; r = 0.24 ± 0.03; Rdx: tM1 = 0.45 ± 0.02; tM2 = 0.31 ± 0.02; r = 0.17 ± 0.03; Fig. 2B,D), and in SOM/mGluR1a interneuron dendrites in particular (α5-GABAAR+VGAT: r = 0.84 ± 0.02; Pearson correlation; Fig. 1B). Similar co-occurrence of Rdx, α5-GABAAR and VGAT was observed at any level of the RAD (Fig. 2D), although the level of synaptically expressed Rdx was significantly lower in this area compared with O/A. These observations agree with previous studies showing that CA1 pyramidal neurons exhibit synaptic and extrasynaptic expression of the α5-GABAAR (Fritschy et al., 1998; Brünig et al., 2002; Christie et al., 2002; Crestani et al., 2002; Vargas-Caballero et al., 2010; Brady and Jacob, 2015; Schulz et al., 2018). The immunoreactivity for Rdx and α5-GABAAR was similar across the CA1 area, although the expression for the two proteins appeared slightly higher within the CA1 O/A (Fig. 2A,C). No labeling for the α5-GABAAR was detected in control slices obtained from Gabra5−/− mice (Fig. 2B, bottom) or with omitted primary antibody for Rdx (Fig. 2D, bottom).

Figure 2.

Synaptic expression of Rdx and α5-GABAAR subunit in CA1 O/A and RAD. A, C, Representative confocal images of the CA1 O/A and RAD immunoreactivity with antibodies specific for α5-GABAAR subunit (A), Rdx (C), VGAT, and their superimposition. B, D, Top, Quantitative colocalization analysis for synaptic α5-GABAAR (B) and Rdx (D); full squares represent mean values ± SE for each coefficient and each layer, whereas open circles represent individual values from individual slices (*p < 0.05; n.s. p > 0.05). B, D, Bottom, Control images obtained in slices from the Gabra5−/− mice (control for the α5-GABAAR subunit; B) and by omitting the primary antibodies for Rdx (D). Scale bars: A, C: 10 μm; B, D: 20 μm.

α5-GABAAR subunit is targeted to CR+/VIP+ interneuron inputs

Because CR/VIP-coexpressing IS3 cells and PV+ interneurons provide inhibitory synaptic inputs to SOM+ interneurons (Acsády et al., 1996; Chamberland et al., 2010; Lovett-Barron et al., 2012; Tyan et al., 2014), we next examined whether the α5-GABAAR subunit is targeted to specific synaptic connections. For these experiments, CRCre or PVCre mice were injected into the CA1 hippocampus with AAV2-DIO-ChR2:mCherry virus (Figs. 3A, left; 4). In addition, VIPCre:ChR2-YFP mice were generated by crossing the VIPCre and Ai32 (DIO-ChR2-YFP) mice to allow the Cre-dependent expression of ChR2 specifically in VIP interneurons (Fig. 3A, right). A double immunolabeling for mCherry and CR or YFP and VIP in CRCre:ChR2-mCherry and VIPCre:ChR2-YFP mice, respectively, allowed us to conclude that the ChR2 was targeted to the cells that express CR or VIP endogenously (Fig. 3A; Tyan et al., 2014; David and Topolnik, 2017), including CR+/VIP+ coexpressing interneurons. The mCherry- or YFP-labeled axons of targeted interneurons were predominantly concentrated within the O/A border consistent with an axonal pattern of IS3 cells (Acsády et al., 1996; Chamberland et al., 2010; Tyan et al., 2014).

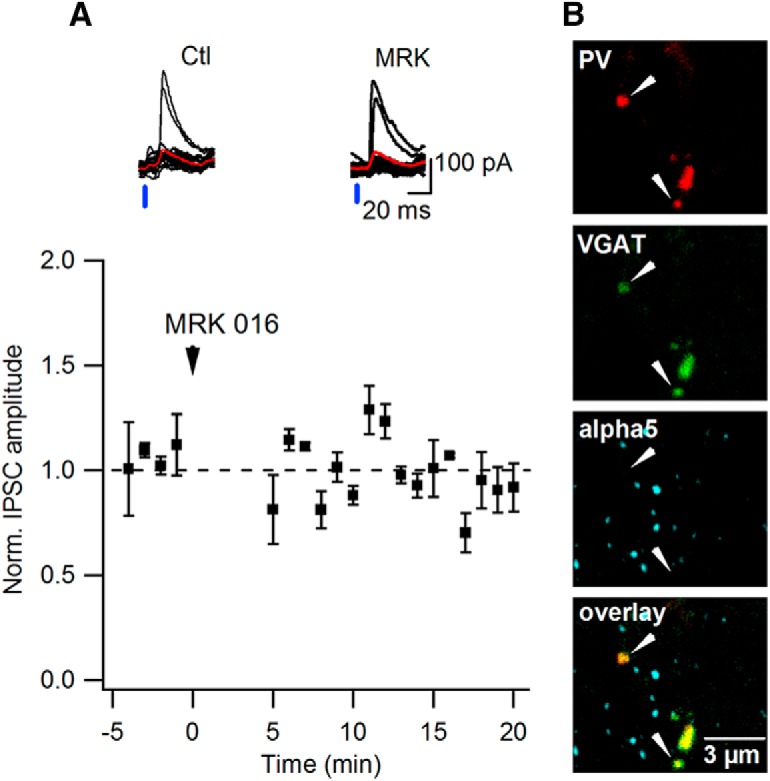

Figure 4.

The α5-GABAAR subunit is not targeted to PV+ inputs. A, Representative traces of synaptic currents evoked by light stimulation with the average trace indicated in red in control (left) and in the presence of the α5-GABAAR subunit inverse agonist MRK-016 (right) at PV–SOM interneuron synapses (top) and summary plot (n = 5 cells) of the normalized amplitude of the light-evoked synaptic currents over time (normalized by the first 5 min of recordings) obtained from ChR2-injected PVCre mice before and after MRK-016 application (bottom). B, Representative confocal images of the hippocampal CA1 O/A layer showing α5-GABAAR subunit expression at the synapses of the PV-interneurons: green (top), VGAT; red (second image), PV-interneurons axonal boutons; blue (third image), α5-GABAAR subunit; bottom image presents overlay. Scale bar, 3 μm.

For electrophysiological recordings, hippocampal slices were obtained from CRCre or PVCre mice injected with Cre-dependent AAV2-DIO-ChR2:mCherry or from VIPCre:ChR2-YFP mice. This preparation allowed excitation of inhibitory projections from CR+, PV+, or VIP+ interneurons, respectively, while recording responses from O/A interneurons (Figs. 3C, 4A). Only SOM+ OLM (Fig. 3E, left), bistratified (Fig. 3E, middle), and long-range projecting (Fig. 3E, right) cells were included in this analysis. SOM+ O/A interneurons in slices from three mouse models had similar resting membrane potential of −61.3 ± 1.7 mV and input resistance of 282.0 ± 38.8 MΩ (n = 25). Photoactivation of the ChR2-expressing fibers (light pulse, 3–5 ms) from CRCre or VIPCre cells within O/A induced 1–2 action potentials in these cells (Fig. 3B), demonstrating that both inputs can be efficiently activated with light to provide inhibition to O/A SOM+ interneurons. Indeed, 5 ms pulses of blue light elicited inhibitory currents in SOM+ cells from both inputs with millisecond latency (range 4–6 ms; Fig. 3C), indicative of monosynaptic connections. Synaptic currents (amplitude 116.0 ± 25.7 and 286.4 ± 30.9 pA for CR and VIP inputs, respectively, Vm holding = +10 mV) from both inputs were partially inhibited by the α5-GABAAR inverse agonists L-655,708 [CR-input: to 65.5 ± 7.3% of control mice (Ctl), n = 8, p < 0.05, paired t test; VIP-input: to 58.7 ± 9.2% of Ctl, n = 6, p < 0.01, paired t test] or MRK-016 (CR-input: to 70.9 ± 6.8% of Ctl, n = 7, p < 0.05, paired t test; VIP-input: to 80.7 ± 2.6% of Ctl, n = 5, p < 0.05, paired t test; Fig. 3C,D); thus, revealing the presence of the α5-GABAAR subunit at these synapses. Of 25 patch-clamped SOM+ interneurons from 6 CRCre mice and 7 VIPCre:ChR2-YFP mice, 22 showed sensitivity to the α5-GABAAR subunit inverse agonists, indicating that most of SOM+ O/A interneurons receive CR+ and VIP+ inhibitory inputs through α5-GABAAR-containing synapses. A significant fraction of these cells were identified as OLM interneurons (Fig. 3D, red lines), but IPSCs recorded in bistratified and long-range projecting SOM+ neurons were also sensitive to the α5-GABAAR inverse agonists. In contrast, of five patch-clamped interneurons from three PVCre mice, with photoactivation of PV+ inputs, only one SOM+ cell showed sensitivity to MRK-016, indicating that α5-GABAAR subunit may be expressed at a subset of PV to SOM+ interneuron synapses (Fig. 4A). Indeed, the α5-GABAAR puncta were co-aligned with a few PV+ synaptic boutons (colocalization ratio = 23.0 ± 3.6%; n = 17 slices/3 mice; Fig. 4B). Altogether, these data demonstrate that SOM+ interneurons in hippocampal CA1 O/A express the α5-GABAAR subunit at synapses made preferentially by the CR+ and VIP+ inhibitory inputs, including those originating from the IS3 cells.

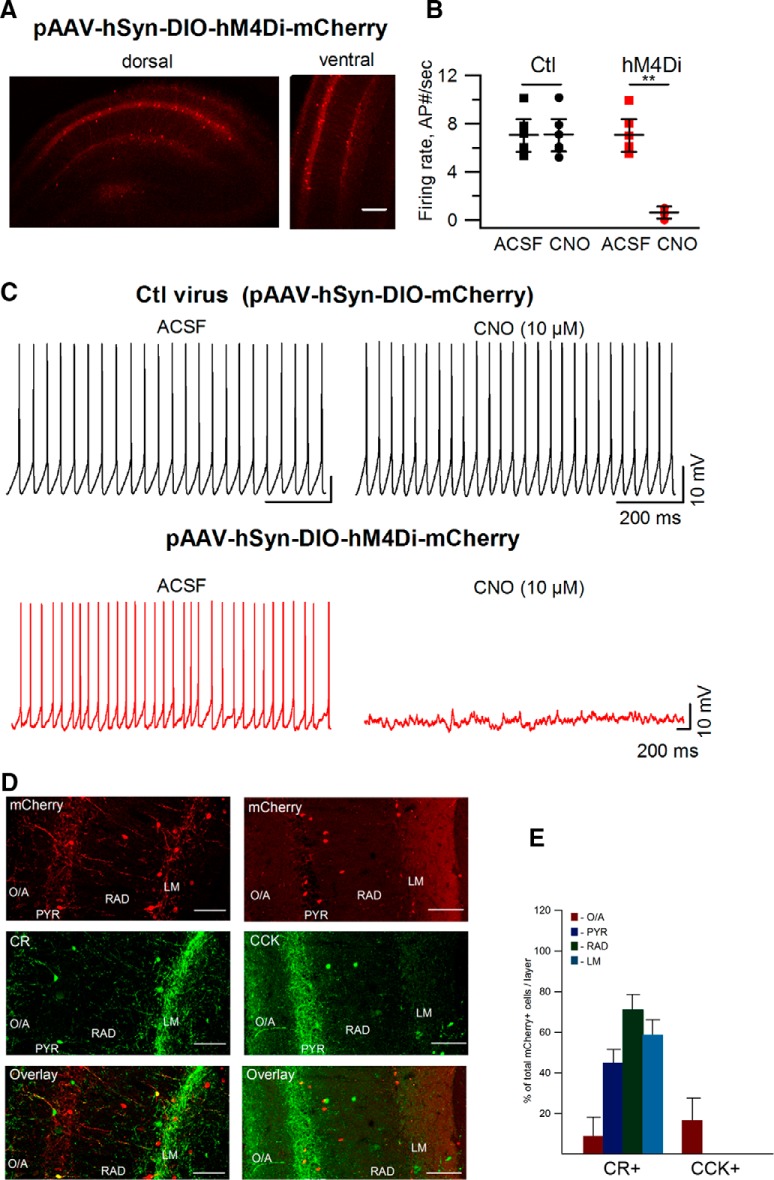

Chemogenetic inactivation of VIP+ interneurons

To investigate the functional role of the α5-GABAAR subunit at VIP+ inputs, we applied a chemogenetic approach allowing selective silencing of VIPCre interneurons by CA1 injection of AAV encoding a Cre-dependent Gi-coupled designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD) fused to the fluorescent protein mCherry (AAV8-DIO-hM4Di:mCherry; Fig. 5). The AAV8 serotype vector was used to provide a high-efficiency transduction for widespread hippocampal delivery (Broekman et al., 2006), which was necessary to target both dorsal and ventral parts of the hippocampus (Fig. 5A). The otherwise inert ligand, CNO, has been shown to activate the hM4Di receptor in vivo and to inhibit different neuronal types (Armbruster et al., 2007; Urban and Roth, 2015). To determine whether CNO is able to silence VIP+ interneurons expressing the hM4Di receptor, electrophysiological analysis was performed on hippocampal brain slices prepared from VIPCre mice that had been injected at least 3 weeks before with AAV8-DIO-hM4Di:mCherry (hM4Di) or with a control virus pAAV-hSyn-DIO-mCherry (bilateral injection, 2 sites/hemisphere, 100 nl/injection site). The spiking of VIP+ cells was recorded in current-clamp at a holding potential of −45 mV (Fig. 5C). In the presence of CNO, IS3 interneurons recorded in hM4Di mice reliably decreased their frequency of firing compared with the pre-drug condition (5 out of 5 cells tested; Fig. 5B,C, bottom). In contrast, CNO had no effect on cells that were targeted with a control vector (Fig. 5B,C, top). To determine the types of VIP+ interneurons (including the CR-coexpressing IS3 and CCK-coexpressing basket cells) that are likely to be targeted with this chemogenetic approach, we performed immunocytochemical analysis of hM4Di-mCherry-expressing VIP+ interneurons (Fig. 5D,E). Our data showed that VIP/CR-coexpressing IS3 cells were making ∼50% of the total VIP+ population targeted with DREADDs, whereas the population of the CCK-coexpressing basket cells reached no >5% across the CA1area, and were concentrated within the CA1 O/A (Fig. 5D,E). Other VIP+ cells targeted for chemogenetic silencing were CR- and CCK-negative and, thus, could correspond to the type 2 IS cells with soma located within stratum lacunosum moleculare (Acsády et al., 1996) or to the subiculum-projecting VIP+ neurons with cell bodies found in different CA1 layers (Francavilla et al., 2018). Together, these data indicate that the CNO administration to VIPCre mice injected into the CA1 with AAV8-DIO-hM4Di:mCherry can be successfully used for silencing VIP+ interneurons, including the IS3 cells.

Figure 5.

Chemogenetic inactivation of VIP+ interneurons via a Gi-coupled receptor. A, Representative confocal images depicting viral targeting sites in coronal sections including the dorsal and the ventral CA1 areas of the mouse hippocampus. Scale bar, 100 μm. B, C, Summary data for a group of cells (B) and representative examples of spiking activity (C) recorded from interneurons in slices obtained from mice injected with a control virus (black) or pAAV-hSyn-DIO-hM4Di:mCherry (red) before and after addition of CNO (10 μm). Application of CNO inhibited firing activity in IS3 cells expressing hM4Di:mCherry (n = 6 cells from two mice; **p < 0.01; paired t test). D, Representative confocal images showing expression of mCherry in CR+/VIP+ interneurons (left) and CCK+/VIP+ interneurons (right) in the hippocampal CA1 area. Scale bars, 50 μm. E, Summary bar graphs showing the relative fraction of CR and CCK coexpressing VIP+ cells targeted with hM4Di:mCherry in different CA1 layers.

Inhibiting the α5-GABAAR improves spatial learning independent of VIP+ input

To examine the role of the α5-GABAAR expressed at VIP+ input in the hippocampus-dependent memory, we next compared the effect of L-655,708 on spatial learning in control mice versus those with CA1 VIP+ interneurons silenced (CA1-VIP-Off). One month after the VIPCre mice underwent bilateral two-site AAV8-DIO-hM4Di:mCherry (experimental group) or control vector (control group) CA1 injections, behavioral experiments to test the spatial memory were executed. Four different groups of mice of either sex were used: Ctl injected with a control viral vector and receiving vehicle intraperitoneal injection (0.9% NaCl; n = 14), and three experimental groups comprising mice injected with hM4Di:mCherry virus and receiving CNO (n = 9), L-655,708 (n = 13), or CNO in combination with L-655,708 (n = 9). We used a WTM, which allows for simultaneous testing of both allocentric and egocentric spatial learning (Rönnbäck et al., 2011; Michaud et al., 2012; Guariglia and Chadman, 2013; Peckford et al., 2013; Spink et al., 2014). During baseline measurements, no spatial preference using WTM were observed in the two groups of mice (data not shown). Animals were then trained to find a hidden platform in one of the WTM arms during eight consecutive trials and the escape time was recorded during each trial as well as 4 h later in a second set of trials. The control mice showed a good learning curve when administered with saline, they could locate the hidden platform with a minimal escape time starting from the third trial and retained the platform location after a 4 h delay period (Fig. 6A, black, E). To silence VIP+ interneurons, the first experimental group of mice received CNO injections (1 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) 30 min before the beginning of each set of trials. Treatment with CNO impaired spatial learning in hM4Di-expressing animals with respect to both acquisition learning and the 4 h retention efficacy (hM4Di mice: n = 9; p < 0.01 compared with Ctl mice; one-way ANOVA followed by Kruskal–Wallis test; Fig. 6A). The CA1-VIP-Off mice spent more time searching for the hidden platform over the course of the experiment and were making a larger amount of mistakes by entering in the opposite arm of the T-maze (Fig. 6A). Administration of L-655,708 alone improved the acquisition learning curve in hM4Di mice (n = 13; p < 0.01 compared with Ctl mice; one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak test; Fig. 6B,D,F). Moreover, administering L-655,708 on top of CNO in hM4Di mice was able to reverse the spatial impairments induced by CNO alone (n = 9; p < 0.01; one-way ANOVA followed by Holm–Sidak test; Fig. 6C,G,H, red), indicating that the memory-enhancing L-655,708 effect occurs independently of the VIP+ interneuron input.

The anxiogenic effect of L-655,708 is prevented by VIP+ input inactivation

The α5-GABAAR inhibition is associated with a significant anxiogenic effect (Navarro et al., 2002; Behlke et al., 2016; Mohler and Rudolph, 2017). To determine whether the α5-GABAAR expressed at VIP+ synapses is involved in the regulation of anxiety, we examined the effect of L-655,708 administration in control (n = 8) versus CA1-VIP-Off mice, which received L-655,708 alone (n = 8) or in combination with CNO injection (n = 9) during EPM behavior task (Fig. 7). First, administering the CNO alone in control naive mice, that did not undergo stereotaxic surgery, did not induce anxiety, because their behavior was similar to their littermates receiving saline injection (n = 8 mice/group; p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 7A). Similarly, administering the CNO in hM4Di mice, which resulted in chemogenetic silencing of CA1 VIP+ interneurons (Fig. 5B), did not induce anxiety when compared with control mice injected with a control vector (p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 7B,C), indicating that this approach can be used for comparison of the anxiogenic effect of L-655,708 in Ctl versus CA1-VIP-Off mice. Second, consistent with previous reports, mice receiving L-655,708 alone were spending less time (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test; Fig. 7B) and were less active in open arms (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test; Fig. 7C), indicative of increased anxiety. Importantly, when administered on top of CNO, L-655,708 failed to increase anxiety (p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test; Fig. 7B,C). To further validate this observation, we administered L-655,708 in combination with CNO and caffeine, a well known anxiogenic agent (El Yacoubi et al., 2000; Patki et al., 2015). In this case, mice that received caffeine alone (n = 7) spent significantly less time (p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 7B) and were less active (p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA followed by Mann–Whitney; Fig. 7C) in open arms of EPM, consistent with an anxiogenic effect of caffeine. Moreover, mice receiving L-655,708 in combination with CNO and caffeine (n = 7) exhibited also a strong anxiety (time in open arms: p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Mann–Whitney; Fig. 7B; distance in open arms: p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test; Fig. 7C). These data indicate that while the anxiogenic effect of L-655,708 is blocked in CA1-VIP-Off mice, these mice are still capable of demonstrating this behavior via alternative mechanisms.

Because decreased activity in open arms can also point to decreased locomotion, we next explored the animals' behavior in the OFM. Administering the L-655,708 had no effect on the total distance (unpaired t test; Fig. 7E), the track pattern (Fig. 7D, red track), or the distance made on periphery (unpaired t test; Fig. 7F), indicating that L-655,708 has no effect on these parameters. These findings were in contrast to those obtained for caffeine, which produced a significant decrease in locomotion (p < 0.01; unpaired t test; Fig. 7E) and pronounced thigmotaxis (Fig. 7D, green track). Administering the CNO alone or in combination with L-655,708 resulted in the increased exploratory activity (Fig. 7D, blue track; p < 0.05; unpaired t test; Fig. 7E,F), which needs to be detailed in future studies. Thus, consistent with the previous report (Fischell et al., 2015), our data indicate that L-655,708 alone does not affect hedonic or open-field behavior. Rather, the anxiogenic effect of L-655,708 is context-specific and can involve α5-GABAAR expressed at VIP+ synapses.

Discussion

We demonstrate that the α5-GABAAR subunit exhibits a cell- and input-specific location in hippocampal CA1 interneurons. It is expressed at synapses made by the VIP+ and CR+ inputs onto dendrites of SOM+ O/A interneurons. We also show that the synapse-specific expression of the α5-GABAAR is involved in the regulation of anxiety, because administering the α5-GABAAR inverse agonist L-655,708 in CA1-VIP-Off mice blocked the anxiogenic effect of this pharmacological agent. In contrast, the memory-enhancing effect of L-655,708 may occur independently of the VIP+ input, because its administration in both control and CA1-VIP-Off mice improved spatial learning. Thus, the α5-GABAAR-mediated phasic inhibition via VIP+ synapses plays a role in the regulation of anxiety, whereas the α5-GABAAR tonic inhibition may control spatial learning.

In the hippocampus, GABAergic inhibitory interneurons are interconnected through synapses containing different combinations of the α GABAAR subunits (Nusser et al., 1998; Patenaude et al., 2001). The α5-GABAAR exhibits a particularly high expression in the mouse and rat hippocampus but also in the olfactory bulb, amygdala, and deep cortical layers (Wisden et al., 1992; Fritschy and Mohler, 1995; Mohler and Rudolph, 2017; Stefanits et al., 2018). Recent transcriptomic analysis revealed the α5-GABAAR subunit mRNA expression in different types of cortical interneurons (Paul et al., 2017). Furthermore, this subunit is highly expressed in the human hippocampal CA1 area and is detected in dendrites of CA1 interneurons (Stefanits et al., 2018). Extending these observations, we found a preferential expression of the α5-GABAAR anchor protein Rdx in CA1 SOM+ cells. In addition, we report a prominent expression of this subunit in dendrites of SOM+/mGluR1a+ OLM cells. Considering the spike initiation and active propagation in dendrites of OLM interneurons (Martina et al., 2000), the α5-GABAAR subunit may control dendritic input-output transformations and the induction of the Hebbian forms of synaptic plasticity in these cells (Camiré et al., 2012; Topolnik, 2012; Sekulić et al., 2015). The density of the α5-GABAAR subunit declined with distance from the soma, consistent with a distance-dependent decline in the number of inhibitory synapses. Such spatial gradient in OLM dendritic inhibition may therefore facilitate the integration of excitatory inputs and local spike initiation in distal dendritic branches (Traub and Miles, 1995; Saraga et al., 2003; Rozsa et al., 2004; Camiré and Topolnik, 2014). It is reported that O/A interneurons receive glutamatergic inputs mostly from the CA1 pyramidal cells (PCs) but also from the CA3 PCs, basolateral amygdala (BLA) and entorhinal afferents (Blasco-Ibáñez and Freund, 1995; Martina et al., 2000; Somogyi and Klausberger, 2005). Although the distance-dependent distribution of the specific excitatory afferents onto OLM dendrites remains to be determined, a higher density of the inhibitory synapses containing the α5-GABAAR in proximal dendrites may participate in input segregation through kinetically slow inhibition (Caraiscos et al., 2004; Salesse et al., 2011).

OLM cells receive their local inhibitory inputs from the PV+ and VIP+ interneurons and a long-range projection from the medial septum (Chamberland et al., 2010; Lovett-Barron et al., 2012). We previously reported that slow IPSCs evoked in OLMs by minimal electrical stimulation were sensitive to the α5-GABAAR inverse agonist (Salesse et al., 2011). Furthermore, unitary IPSCs (uIPSCs) generated at IS3 synapses formed onto OLM cells were also significantly slower than those generated typically at the α1-GABAAR-containing synapses (Bartos et al., 2001; Tyan et al., 2014), consistent with the expression of a different α GABAAR subunit at the IS3 synapses. Our current data build upon these previous findings, showing the presence of the α5-GABAAR subunit at the IS3 synapses. It is to be noted that uIPSCs at the IS3 to basket and to bistratified cell synapses are significantly faster than those at the OLM synapses (Tyan et al., 2014), suggesting different α GABAAR subunit combinations (e.g., α5-GABAAR+α1-GABAAR or α5-GABAAR+α3-GABAAR; Mertens et al., 1993) or distinct dendritic location of synapses (Maccaferri et al., 2000). Furthermore, our finding of a very low expression of the α5-GABAAR subunit at the PV+ inhibitory inputs is in line with fast inhibition reported typically at the PV+ synapses because of a predominant expression of the α1-GABAAR (Nyíri et al., 2001; Klausberger et al., 2002). Such input-specific localization of different GABAAR subunits within the same cell can be controlled by the activity-dependent trafficking mechanisms (Hausrat et al., 2015), which can be tailored to specific pathways depending on transmitted signals.

What can be the functional role of the SOM+ interneuron phasic inhibition brought upon by the VIP+/CR+ inputs containing α5-GABAAR? As OLM cell is the main target of the VIP+/CR+ inputs in the CA1 area (Tyan et al., 2014; Francavilla et al., 2015, 2018), activation of these synapses likely coordinates OLM recruitment in vivo. Inhibition sets rebound firing and theta resonance behavior in OLM cells (Tyan et al., 2014; Sekulić and Skinner, 2017), which, through modulation of the integrative properties of the CA1 PC apical dendrites, shapes the information flow from the entorhinal cortex and the thalamic nucleus reuniens (Klausberger and Somogyi, 2008). In parallel, because OLMs make synapses onto some CA1 interneurons (Chamberland and Topolnik, 2012; Leão et al., 2012), coordination of the OLM activity through the α5-GABAAR-containing synapses may also control the input-specific disinhibition in the CA1, with a direct impact on the input separation and selectivity of sensory gating. Therefore, given a critical role of the OLM cells in coordination of the CA1 microcircuit modules, input-specific modulation of their activity may support the hippocampus-dependent mnemonic and cognitive processes.

Using selective chemogenetic inactivation of CA1 VIP+ interneurons, we show that VIP+ input to interneurons is involved in the regulation of spatial learning. Importantly, the majority of VIP+ cells targeted in these experiments were the interneuron-selective cells, because VIP+ BCs made only a small fraction of VIP+ interneurons (Fig. 5). These data indicate that disinhibited interneurons may be unable to provide precise spatiotemporal coordination of hippocampal cell ensembles during acquisition learning and memory formation. The overall firing of CA1 O/A interneurons in CA1-VIP-Off mice is likely increased, and may result in a higher level of ambient GABA and increased tonic inhibition via extrasynaptically located GABAARs, including the α5-GABAAR (Glykys and Mody, 2007). Pharmacological or genetic removal of the α5-GABAAR improved spatial learning in previous studies (Collinson et al., 2002; Atack et al., 2006). In line with these reports, we provide evidence that impaired spatial learning following chemogenetic inactivation of VIP+ interneurons can be successfully rescued by the administration of the α5-GABAAR inverse agonist L-655,708, pointing to the VIP+ input-independent cognitive effect of L-655,708. This suggests that memory enhancement associated with administration of the α5-GABAAR inhibitors may arise from the removal of tonic (Atack et al., 2006; Braudeau et al., 2011; Soh and Lynch, 2015) and phasic inhibition (Hausrat et al., 2015; Schultz et al., 2018) in CA1 PCs or, alternatively, through modulation of other non-pyramidal cells, including dendrite-targeting interneurons and astrocytes (Rodgers et al., 2015).

The anxiogenic effect of L-655,708 is believed to arise from its nonspecific interactions with other α-GABAAR subunits (Mohler and Rudolph, 2017). In keeping with this view, the α5-GABAAR knock-outs showed no evidence for its role in regulation of anxiety (Collinson et al., 2002; Crestani et al., 2002). However, the cell-specific knock-down of this subunit in central amygdala uncovered the anxiety-related phenotypes (Botta et al., 2015), highlighting the cell- and circuit-specific mechanisms in the α5-GABAAR function. Our data also support this view by showing that phasic inhibition provided by the α5-GABAAR-containing VIP+ inputs onto CA1 interneurons may be involved in regulation of anxiety. This mechanism may preferentially operate in ventral hippocampus, which may control innate anxiety behavior (Jimenez et al., 2018; Schumacher et al., 2018). In this case, disinhibition of CA1 SOM+ interneurons using the α5-GABAAR inverse agonist and, subsequently, increased dendritic inhibition of CA1 PCs may suppress their burst firing (Royer et al., 2012), leading to functional insufficiency. Interestingly, in line with this scenario, recent findings indicate that ventral CA1 inactivation can increase avoidance behavior (Schumacher et al., 2018). In addition, previous reports indicate that the BLA glutamatergic input to the CA1 PCs and interneurons is directly involved in anxiety behavior (Pitkänen et al., 2000; Felix-Ortiz et al., 2013). As CA1 SOM+ interneurons may balance the level of excitation arriving from different sources (Leão et al., 2012; Siwani et al., 2018), we propose a circuit model in which disinhibition of SOM+ interneurons may shift the balance toward enhanced integration of the BLA input, with a direct impact on the recruitment of CA1 PCs in anxiety-like behavior. The circuit and synaptic mechanisms that may be involved in this scenario remain to be determined.

In conclusion, our data provide new insights regarding the cellular location and the functional role of the α5-GABAAR subunit in the mouse CA1 hippocampus. In particular, we report that expression of the α5-GABAAR at synapses formed by the VIP+ inputs onto O/A SOM+ interneurons is involved in the regulation of anxiety-like behavior. Together, our results on the synapse-specific expression and role of the α5-GABAAR highlight the circuit mechanisms as an important variable to consider when designing pharmacological interventions for cognitive therapy.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. We thank Dr. Jean-Marc Fritschy for providing the α5 GABAAR antibody, Drs. K. Deisseroth and B. Roth for plasmids, Dr. Serge Rivest for giving access to the behavior research equipment. Olivier Camiré for help with Neurolucida reconstructions and critical comments on the paper. Sarah Côté, Stéphanie Racine-Dorval and Dimitry Topolnik for technical assistance, and colleagues from the Topolnik laboratory for fruitful discussions.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Acsády L, Görcs TJ, Freund TF (1996) Different populations of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-immunoreactive interneurons are specialized to control pyramidal cells or interneurons in the hippocampus. Neuroscience 73:317–334. 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00609-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali AB, Thomson AM (2008) Synaptic alpha 5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors mediate IPSPs elicited by dendrite-preferring cells in rat neocortex. Cereb Cortex 18:1260–1271. 10.1093/cercor/bhm160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL (2007) Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:5163–5168. 10.1073/pnas.0700293104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atack JR, Bayley PJ, Seabrook GR, Wafford KA, McKernan RM, Dawson GR (2006) L-655,708 enhances cognition in rats but is not proconvulsant at a dose selective for alpha5-containing GABAA receptors. Neuropharmacology 51:1023–1029. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Vida I, Frotscher M, Geiger JR, Jonas P (2001) Rapid signaling at inhibitory synapses in a dentate gyrus interneuron network. J Neurosci 21:2687–2698. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02687.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann SW, Baur R, Sigel E (2001) Subunit arrangement of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. J Biol Chem 276:36275–36280. 10.1074/jbc.M105240200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechard A, Meagher R, Mason G (2011) Environmental enrichment reduces the likelihood of alopecia in adult C57BL/6J mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 50:171–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behlke LM, Foster RA, Liu J, Benke D, Benham RS, Nathanson AJ, Yee BK, Zeilhofer HU, Engin E, Rudolph U (2016) A pharmacogenetic “restriction-of-function” approach reveals evidence for anxiolytic-like actions mediated by alpha5-containing GABAA receptors in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology 41:2492–2501. 10.1038/npp.2016.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco-Ibáñez JM, Freund TF (1995) Synaptic input of horizontal interneurons in stratum oriens of the hippocampal CA1 subfield: structural basis of feed-back activation. Eur J Neurosci 7:2170–2180. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta P, Demmou L, Kasugai Y, Markovic M, Xu C, Fadok JP, Lu T, Poe MM, Xu L, Cook JM, Rudolph U, Sah P, Ferraguti F, Lüthi A (2015) Regulating anxiety with extrasynaptic inhibition. Nat Neurosci 18:1493–1500. 10.1038/nn.4102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady ML, Jacob TC (2015) Synaptic localization of α5 GABA(A) receptors via gephyrin interaction regulates dendritic outgrowth and spine maturation. Dev Neurobiol 75:1241–1251. 10.1002/dneu.22280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braudeau J, Delatour B, Duchon A, Pereira PL, Dauphinot L, de Chaumont F, Olivo-Marin JC, Dodd RH, Hérault Y, Potier MC (2011) Specific targeting of the GABA-A receptor alpha5 subtype by a selective inverse agonist restores cognitive deficits in down syndrome mice. J Psychopharmacol 25:1030–1042. 10.1177/0269881111405366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekman ML, Comer LA, Hyman BT, Sena-Esteves M (2006) Adeno-associated virus vectors serotyped with AAV8 capsid are more efficient than AAV-1 or -2 serotypes for widespread gene delivery to the neonatal mouse brain. Neuroscience 138:501–510. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünig I, Scotti E, Sidler C, Fritschy JM (2002) Intact sorting, targeting, and clustering of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor subtypes in hippocampal neurons in vitro. J Comp Neurol 443:43–55. 10.1002/cne.10102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camiré O, Topolnik L (2014) Dendritic calcium nonlinearities switch the direction of synaptic plasticity in fast-spiking interneurons. J Neurosci 34:3864–3877. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2253-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camiré O, Lacaille JC, Topolnik L (2012) Dendritic signaling in inhibitory interneurons: local tuning via group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. Front Physiol 3:259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraiscos VB, Elliott EM, You-Ten KE, Cheng VY, Belelli D, Newell JG, Jackson MF, Lambert JJ, Rosahl TW, Wafford KA, MacDonald JF, Orser BA (2004) Tonic inhibition in mouse hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons is mediated by alpha5 subunit-containing gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:3662–3667. 10.1073/pnas.0307231101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberland S, Topolnik L (2012) Inhibitory control of hippocampal inhibitory neurons. Front Neurosci 6:165. 10.3389/fnins.2012.00165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberland S, Salesse C, Topolnik D, Topolnik L (2010) Synapse-specific inhibitory control of hippocampal feedback inhibitory circuit. Front Cell Neurosci 4:130. 10.3389/fncel.2010.00130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie SB, Miralles CP, De Blas AL (2002) GABAergic innervation organizes synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptor clustering in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 22:684–697. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00684.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson N, Kuenzi FM, Jarolimek W, Maubach KA, Cothliff R, Sur C, Smith A, Otu FM, Howell O, Atack JR, McKernan RM, Seabrook GR, Dawson GR, Whiting PJ, Rosahl TW (2002) Enhanced learning and memory and altered GABAergic synaptic transmission in mice lacking the α5 subunit of the GABAA receptor. J Neurosci 22:5572–5580. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05572.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crestani F, Keist R, Fritschy JM, Benke D, Vogt K, Prut L, Blüthmann H, Möhler H, Rudolph U (2002) Trace fear conditioning involves hippocampal α5 GABA(A) receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:8980–8985. 10.1073/pnas.142288699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David LS, Topolnik L (2017) Target-specific alterations in the VIP inhibitory drive to hippocampal GABAergic cells after status epilepticus. Exp Neurol 292:102–112. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH (2011) A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300:C723–742. 10.1152/ajpcell.00462.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Yacoubi M, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Costentin J, Vaugeois JM (2000) The anxiogenic-like effect of caffeine in two experimental procedures measuring anxiety in the mouse is not shared by selective A(2A) adenosine receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology 148:153–163. 10.1007/s002130050037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz AC, Beyeler A, Seo C, Leppla CA, Wildes CP, Tye KM (2013) BLA to vHPC inputs modulate anxiety-related behaviors. Neuron 79:658–664. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischell J, Van Dyke AM, Kvarta MD, LeGates TA, Thompson SM (2015) Rapid antidepressant action and restoration of excitatory synaptic strength after chronic stress by negative modulators of alpha5-containing GABAA receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 40:2499–2509. 10.1038/npp.2015.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francavilla R, Luo X, Magnin E, Tyan L, Topolnik L (2015) Coordination of dendritic inhibition through local disinhibitory circuits. Front Synaptic Neurosci 7:5. 10.3389/fnsyn.2015.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francavilla R, Villette V, Luo X, Chamberland S, Muñoz-Pino E, Camiré O, Wagner K, Kis V, Somogyi P, Topolnik L (2018) Connectivity and network state-dependent recruitment of long-range VIP-GABAergic neurons in the mouse hippocampus. Nat Commun 9:5043. 10.1038/s41467-018-07162-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Mohler H (1995) GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J Comp Neurol 359:154–194. 10.1002/cne.903590111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Johnson DK, Mohler H, Rudolph U (1998) Independent assembly and subcellular targeting of GABA(A)-receptor subtypes demonstrated in mouse hippocampal and olfactory neurons in vivo. Neurosci Lett 249:99–102. 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00397-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Mody I (2006) Hippocampal network hyperactivity after selective reduction of tonic inhibition in GABA A receptor alpha5 subunit-deficient mice. J Neurophysiol 95:2796–2807. 10.1152/jn.01122.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Mody I (2007) Activation of GABAA receptors: views from outside the synaptic cleft. Neuron 56:763–770. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guariglia SR, Chadman KK (2013) Water T-maze: a useful assay for determination of repetitive behaviors in mice. J Neurosci Methods 220:24–29. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausrat TJ, Muhia M, Gerrow K, Thomas P, Hirdes W, Tsukita S, Heisler FF, Herich L, Dubroqua S, Breiden P, Feldon J, Schwarz JR, Yee BK, Smart TG, Triller A, Kneussel M (2015) Radixin regulates synaptic GABAA receptor density and is essential for reversal learning and short-term memory. Nat Commun 6:6872. 10.1038/ncomms7872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez JC, Su K, Goldberg AR, Luna VM, Biane JS, Ordek G, Zhou P, Ong SK, Wright MA, Zweifel L, Paninski L, Hen R, Kheirbek MA (2018) Anxiety cells in a hippocampal-hypothalamic circuit. Neuron 97:670–683.e6. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Somogyi P (2008) Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: the unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science 321:53–57. 10.1126/science.1149381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Ehya N, Fuchs K, Fuchs T, Ebert V, Sarto I, Sieghart W (2001) Detection and binding properties of GABA(A) receptor assembly intermediates. J Biol Chem 276:16024–16032. 10.1074/jbc.M009508200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Roberts JD, Somogyi P (2002) Cell type- and input-specific differences in the number and subtypes of synaptic GABAA receptors in the hippocampus. J Neurosci 22:2513–2521. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02513.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leão RN, Mikulovic S, Leão KE, Munguba H, Gezelius H, Enjin A, Patra K, Eriksson A, Loew LM, Tort AB, Kullander K (2012) OLM interneurons differentially modulate CA3 and entorhinal inputs to hippocampal CA1 neurons. Nat Neurosci 15:1524–1530. 10.1038/nn.3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebrich S, Bähring R, Katsuno T, Tsukita S, Kneussel M (2006) Activated radixin is essential for GABAA receptor alpha5 subunit anchoring at the actin cytoskeleton. EMBO J 25:987–999. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett-Barron M, Turi GF, Kaifosh P, Lee PH, Bolze F, Sun XH, Nicoud JF, Zemelman BV, Sternson SM, Losonczy A (2012) Regulation of neuronal input transformations by tunable dendritic inhibition. Nat Neurosci 15:423–430, S1–3. 10.1038/nn.3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, Roberts JD, Szucs P, Cottingham CA, Somogyi P (2000) Cell surface domain specific postsynaptic currents evoked by identified GABAergic neurones in rat hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol 524:91–116. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-3-00091.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina M, Vida I, Jonas P (2000) Distal initiation and active propagation of action potentials in interneuron dendrites. Science 287:295–300. 10.1126/science.287.5451.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens S, Benke D, Mohler H (1993) GABAA receptor populations with novel subunit combinations and drug binding profiles identified in brain by alpha 5- and delta-subunit-specific immunopurification. J Biol Chem 268:5965–5973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud JP, Richard KL, Rivest S (2012) Hematopoietic MyD88-adaptor protein acts as a natural defense mechanism for cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's disease. Stem Cell Rev 8:898–904. 10.1007/s12015-012-9356-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler H, Rudolph U (2017) Disinhibition, an emerging pharmacology of learning and memory. F1000Res 6:101. 10.12688/f1000research.9947.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro JF, Burón E, Martín-López M (2002) Anxiogenic-like activity of L-655,708: a selective ligand for the benzodiazepine site of GABA(A) receptors which contain the alpha-5 subunit, in the elevated plus-maze test. Prog NeuroPsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 26:1389–1392. 10.1016/S0278-5846(02)00305-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Hájos N, Somogyi P, Mody I (1998) Increased number of synaptic GABA A receptors underlies potentiation at hippocampal inhibitory synapses. Nature 395:172–177. 10.1038/25999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyíri G, Freund TF, Somogyi P (2001) Input-dependent synaptic targeting of alpha(2)-subunit-containing GABA(A) receptors in synapses of hippocampal pyramidal cells of the rat. Eur J Neurosci 13:428–442. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01407.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patenaude C, Nurse S, Lacaille JC (2001) Sensitivity of synaptic GABA(A) receptors to allosteric modulators in hippocampal oriens-alveus interneurons. Synapse 41:29–39. 10.1002/syn.1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patki G, Salvi A, Liu H, Atrooz F, Alkadhi I, Kelly M, Salim S (2015) Tempol treatment reduces anxiety-like behaviors induced by multiple anxiogenic drugs in rats. PLoS One 10:e0117498. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Paul A, Crow M, Raudales R, He M, Gillis J, Huang ZJ (2017) Transcriptional architecture of synaptic communication delineates GABAergic neuron identity. Cell 171:522–539.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckford G, McRae SM, Thorpe CM, Martin GM, Skinner DM (2013) Rats' orientation at the start point is important for spatial learning in a water T-maze. Learn Motiv 44:1–15. 10.1016/j.lmot.2012.06.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G (2000) GABA(A) receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience 101:815–850. 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00442-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A, Pikkarainen M, Nurminen N, Ylinen A (2000) Reciprocal connections between the amygdala and the hippocampal formation, perirhinal cortex, and postrhinal cortex in rat: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 911:369–391. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06738.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers FC, Zarnowska ED, Laha KT, Engin E, Zeller A, Keist R, Rudolph U, Pearce RA (2015) Etomidate impairs long-term potentiation in vitro by targeting alpha5-subunit containing GABAA receptors on nonpyramidal cells. J Neurosci 35:9707–9716. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0315-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnbäck A, Zhu S, Dillner K, Aoki M, Lilius L, Näslund J, Winblad B, Graff C (2011) Progressive neuropathology and cognitive decline in a single arctic APP transgenic mouse model. Neurobiol Aging 32:280–292. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer S, Zemelman BV, Losonczy A, Kim J, Chance F, Magee JC, Buzsáki G (2012) Control of timing rate and bursts of hippocampal place cells by dendritic and somatic inhibition. Nat Neurosci 15:769–775. 10.1038/nn.3077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozsa B, Zelles T, Vizi ES, Lendvai B (2004) Distance-dependent scaling of calcium transients evoked by backpropagating spikes and synaptic activity in dendrites of hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci 24:661–670. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3906-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saab BJ, Maclean AJ, Kanisek M, Zurek AA, Martin LJ, Roder JC, Orser BA (2010) Short-term memory impairment after isoflurane in mice is prevented by the alpha5 gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor inverse agonist L-655,708. Anesthesiology 113:1061–1071. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f56228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salesse C, Mueller CL, Chamberland S, Topolnik L (2011) Age-dependent remodelling of inhibitory synapses onto hippocampal CA1 oriens-lacunosum moleculare interneurons. J Physiol 589:4885–4901. 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.215244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraga F, Wu CP, Zhang L, Skinner FK (2003) Active dendrites and spike propagation in multicompartment models of oriens-lacunosum/moleculare hippocampal interneurons. J Physiol 552:673–689. 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz JM, Knoflach F, Hernandez MC, Bischofberger J (2018) Dendrite-targeting interneurons control synaptic NMDA-receptor activation via nonlinear α5-GABAA receptors. Nat Commun 9:3576. 10.1038/s41467-018-06004-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher A, Villaruel FR, Ussling A, Riaz S, Lee ACH, Ito R (2018) Ventral hippocampal CA1 and CA3 differentially mediate learned approach-avoidance conflict processing. Curr Biol 28:1318–1324.e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibenhener ML, Wooten MC (2015) Use of the open field maze to measure locomotor and anxiety-like behavior in mice. J Vis Exp 96:e52434. 10.3791/52434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekulić V, Chen TC, Lawrence JJ, Skinner FK (2015) Dendritic distributions of I h channels in experimentally-derived multi-compartment models of oriens-lacunosum/moleculare (O-LM) hippocampal interneurons. Front Synaptic Neurosci 7:2. 10.3389/fnsyn.2015.00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekulić V, Skinner FK (2017) Computational models of O-LM cells are recruited by low or high theta frequency inputs depending on h-channel distributions. eLife 6:e22962. 10.7554/eLife.22962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwanski DR, Miralles CP, Christie SB, Mehta AK, Li X, De Blas AL (2006) Synaptic and nonsynaptic localization of GABAA receptors containing the alpha5 subunit in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 499:458–470. 10.1002/cne.21115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W, Sperk G (2002) Subunit composition, distribution and function of GABA(A) receptor subtypes. Curr Top Med Chem 2:795–816. 10.2174/1568026023393507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siwani S, França ASC, Mikulovic S, Reis A, Hilscher MM, Edwards SJ, Leão RN, Tort ABL, Kullander K (2018) OLMα2 cells bidirectionally modulate learning. Neuron 99:404–412.e3. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh MS, Lynch JW (2015) Selective modulators of alpha5-containing GABAA receptors and their therapeutic significance. Curr Drug Targets 16:735–746. 10.2174/1389450116666150309120235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Klausberger T (2005) Defined types of cortical interneurone structure space and spike timing in the hippocampus. J Physiol 562:9–26. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.078915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperk G, Schwarzer C, Tsunashima K, Fuchs K, Sieghart W (1997) GABA(A) receptor subunits in the rat hippocampus I: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits. Neuroscience 80:987–1000. 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00146-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spink A, van den Broek EL, Loijens L, Woloszynowska-Fraser M, Noldus L (2014) Proceedings of Measuring Behavior 2014: 9th international conference on methods and techniques in behavioral research (Wageningen, The Netherlands, August 2014). Noldus Information Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanits H, Milenkovic I, Mahr N, Pataraia E, Hainfellner JA, Kovacs GG, Sieghart W, Yilmazer-Hanke D, Czech T (2018) GABAA receptor subunits in the human amygdala and hippocampus: immunohistochemical distribution of 7 subunits. J Comp Neurol 526:324–348. 10.1002/cne.24337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur C, Quirk K, Dewar D, Atack J, McKernan R (1998) Rat and human hippocampal alpha5 subunit-containing gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors have alpha5 beta3 gamma2 pharmacological characteristics. Mol Pharmacol 54:928–933. 10.1124/mol.54.5.928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topolnik L. (2012) Dendritic calcium mechanisms and long-term potentiation in cortical inhibitory interneurons. Eur J Neurosci 35:496–506. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07988.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Miles R (1995) Pyramidal cell-to-inhibitory cell spike transduction explicable by active dendritic conductances in inhibitory cell. J Comput Neurosci 2:291–298. 10.1007/BF00961441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyan L, Chamberland S, Magnin E, Camiré O, Francavilla R, David LS, Deisseroth K, Topolnik L (2014) Dendritic inhibition provided by interneuron-specific cells controls the firing rate and timing of the hippocampal feedback inhibitory circuitry. J Neurosci 34:4534–4547. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3813-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban DJ, Roth BL (2015) DREADDs (designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs): chemogenetic tools with therapeutic utility. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 55:399–417. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Caballero M, Martin LJ, Salter MW, Orser BA, Paulsen O (2010) α5 Subunit-containing GABAA receptors mediate a slowly decaying inhibitory synaptic current in CA1 pyramidal neurons following Schaffer collateral activation. Neuropharmacology 58:668–675. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh RN, Cummins RA (1976) The open field test: a critical review. Psychol Bull 83:482–504. 10.1037/0033-2909.83.3.482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzner DS, Engler-Chiurazzi EB, Kotilinek LA, Ashe KH, Reed MN (2015) Morris water maze test: optimization for mouse strain and testing environment. J Vis Exp 100:e52706. 10.3791/52706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W, Laurie DJ, Monyer H, Seeburg PH (1992) The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain: I. Telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon. J Neurosci 12:1040–1062. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01040.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu ZY, Wang W, Fritschy JM, Witte OW, Redecker C (2006) Changes in neocortical and hippocampal GABAA receptor subunit distribution during brain maturation and aging. Brain Res 1099:73–81. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarnowska ED, Keist R, Rudolph U, Pearce RA (2009) GABAA receptor alpha5 subunits contribute to GABAA,slow synaptic inhibition in mouse hippocampus. J Neurophysiol 101:1179–1191. 10.1152/jn.91203.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurek AA, Bridgwater EM, Orser BA (2012) Inhibition of alpha5 gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors restores recognition memory after general anesthesia. Anesthesia Analgesia 114:845–855. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824720da [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurek AA, Yu J, Wang DS, Haffey SC, Bridgwater EM, Penna A, Lecker I, Lei G, Chang T, Salter EW, Orser BA (2014) Sustained increase in alpha5GABAA receptor function impairs memory after anesthesia. J Clin Invest 124:5437–5441. 10.1172/JCI76669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]