Abstract

Background

Obesity is a growing public health problem. Obesity increases the risk of requiring total joint arthroplasty (TJA). The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of obesity on the propensity for TJA in patients at our institution. We hypothesized that obese patients would be younger and more likely to be races other than non-Hispanic whites when compared to a normal weight cohort.

Methods

568 consecutive patients undergoing primary TJA were reviewed. Demographic data and World Health Organization Body Mass Index (BMI) class were compared statistically, with age at time of TJA used as the main outcome of interest.

Results

The average age at TKA was 68.3 years, while the average age at THA was 67.5 years (p = 0.447 between procedure groups). Increased BMI class was associated with decreased age at TJA: normal weight patients were 12.2 and 11.4 years older than class III obese patients at the time of TKA and THA, respectively (p < 0.001). Among TKA patients, obese patients, when compared to non-obese patients, were significantly less likely to be non-Hispanic whites (p = 0.016). Among THA patients, class III obese patients were significantly less likely to be non-Hispanic whites (p = 0.007).

Conclusions

Obesity is a risk factor for both TKA and THA at a younger age. For patients in the study, for each unit increase in BMI, the age at TKA decreased by 0.56 years and age at THA decreased by 0.52 years. Obese patients were less likely to be non-Hispanic whites than normal weight patients.

Keywords: Total joint arthroplasty, Age at surgery, BMI, Obesity, Race

1. Introduction

Obesity is a growing problem for healthcare systems in the United States and worldwide. More than one-third of American adults are now classified as obese (BMI > 30), an increase of nearly 25% since 2000.1 Obesity is associated with a myriad of health conditions, including type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and osteoarthritis.2, 3, 4 The economic burden of obesity has been estimated at greater than $215B annually in the United States alone.5 Additionally, obesity does not affect all groups equally: 48.1% of non-Hispanic black and 42.5% of Hispanic adults are obese, as compared to 34.5% of non-Hispanic white adults.1 Obesity also increases the relative risk of requiring lower extremity total joint arthroplasty (TJA). The risk of joint replacement increases substantially with increasing BMI: patients with class I obesity (BMI 30–34.9) are 3.4 times more likely to require total hip arthroplasty (THA), and 8.5 times more likely to require total knee arthroplasty (TKA), when compared with normal weight patients. With a BMI > 40, adults are 8.6 times more likely to require hip replacement and a 32.7 times more likely to require knee replacement.6 The BMI of patients undergoing TJA is increasing along with the prevalence of obesity in the country. An analysis of patients at the Mayo Clinic showed that 41.4% of patients undergoing THA from 2002 to 2005 were obese, as compared to 33.1% of patients from 1993 to 1995.7

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of increasing BMI on the propensity for both TKA and THA with respect to age, as well as to compare the racial composition of patient populations across different BMIs. We hypothesized that obese patients undergoing TJA would be younger and more likely to be non-white than patients with BMI < 25.

2. Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this retrospective analysis of prospectively collected TJA database patient records. Diagnosis codes for primary THA (81.51) or TKA (81.54) were used to identify patients, which correspond with surgical CPT codes 27447 (TKA) and 27130 (THA). Revision surgeries and partial joint replacements were excluded. Underweight patients (BMI < 18.5) and patients undergoing bilateral joint replacement during the same hospitalization were excluded. All patients were operated on at a single referral arthroplasty center within an academic hospital system over a ten-year period from 2005 to 2015. For each patient, data on height, weight, age, self-reported race, length of stay, risk mortality index, and severity of illness index were recorded. All height, weight, and age data was from the time of surgery. Body Mass Index was calculated using the standard formula, weight (kg)/height2 (m2), and patients were grouped according to the WHO classifications of obesity.8

Descriptive statistics were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Comparative statistics were performed using RStudio software (RStudio Inc, Boston, MA). Analysis of variance testing (ANOVA) was used to compare continuous variables across BMI classes. When a significant association was identified, pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni’s correction were used to identify between-groups differences. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s X2 test. For these variables, two comparisons were performed. First, patients with obese BMIs were compared to non-obese patients. Next, patients with BMI > 40 were compared to patients with BMI < 40 to determine whether class III obese patients displayed different characteristics from normal weight, overweight, and class I/II obese patients. A P value of 0.05 was used as the cutoff for statistical significance in all analyses. Patient characteristics were first compared between THA and TKA patients. Between groups, age, sex, average BMI, BMI class, race, diabetes status, and risk scores were also compared. Separate analyses were then performed for THA and TKA patients. Within each group, gender, racial composition, and diabetes status of patient populations with different BMI classes were compared. Length of stay, risk scores, and age were compared across BMI classes.

3. Results

In total, 337 TKA patients were included in the analysis. The average age at TKA was 68.3 ± 10.8 years (range 24–89). The patients had an average BMI of 35.7 ± 8.4, indicating that the average patient undergoing knee replacement at our center during the study period was class II obese. 74.5% of patients were obese by WHO criteria, while only 10.7% were classified as normal weight. The patient population showed a heavy female predominance, with females representing 70.9% of TKA patients. Additional demographic data are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical profile of total joint arthroplasty patients.

| Total Knee Arthroplasty | Total Hip Arthroplasty | Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 337 (100%) | 231 (100%) | |

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 68.3 ± 10.8 | 67.5 ± 14.3 | P = 0.447 |

| Gender | P < 0.001 | ||

| Female | 239 (70.9%) | 98 (42.4%) | |

| Male | 98 (29.1%) | 133 (57.6%) | |

| Race | P = 0.002 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 144 (42.7%) | 127 (55.7%) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 169 (50.1%) | 87 (40.0%) | |

| Asian | 8 (2.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Hispanic | 8 (2.4%) | 6 (2.6%) | |

| Other | 8 (2.4%) | 8 (3.5%) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.3%) | |

| Risk Scores | |||

| Risk Mortality Index | 1.88 ± 0.83 | 2.06 ± 0.85 | P = 0.009 |

| Severity Illness Index | 2.28 ± 0.73 | 2.45 ± 0.79 | P = 0.011 |

| Diabetes | 139 (41.2%) | 59 (25.8%) | P < 0.001 |

| Length of Stay (days) | 5.0 ± 4.1 | 5.3 ± 3.9 | P = 0.359 |

| BMI | 35.7 ± 8.4 | 30.9 ± 7.5 | P < 0.001 |

| BMI Classification | P < 0.001 | ||

| Normal Weight (BMI 18.5–24.9) | 36 (10.7%) | 53 (22.9%) | |

| Overweight (BMI 25–29.9) | 50 (14.8%) | 57 (24.7%) | |

| Obese Class I (BMI 30–34.9) | 63 (18.7%) | 53 (22.9%) | |

| Obese Class II (BMI 35–39.9) | 79 (23.4%) | 37 (16.0%) | |

| Obese Class III (BMI > 40) | 109 (32.3%) | 31 (13.4%) |

Analysis of patient populations undergoing total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test, while categorical variables were compared using chi-squared tests. All categorical variables are presented as N (% of total undergoing procedure). All continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

231 THA patients were included in the analysis. The average age at THA was 67.5 ± 14.3 years (range 23–98). The patients had an average BMI of 30.9 ± 7.5, indicating that the average patient undergoing knee replacement at our center during the study period was class I obese. 52.4% of patients were obese by WHO criteria, while 22.9% were classified as normal weight. The patient population showed a slight male predominance, with males representing 57.6% of THA patients. Additional demographic data is listed in Table 1.

The patient populations undergoing THA and TKA were compared (Table 1). There were no significant differences in patient age or length of stay. The gender composition of the patient populations was significantly different (X2 = 44.95, P < 0.001), with TKA showing a heavy female predominance while THA patients were more likely to be male. Additionally, the ethnic composition of each population was different: THA patients were more likely than TKA patients to identify as non-Hispanic whites. Risk mortality index and severity of illness index scores were different between the two groups, with THA patients displaying significantly higher risk of mortality (p = 0.009) and severity of illness scores (p = 0.011). Finally, the average BMI and distribution of BMI classifications varied between groups: TKA patients had an average BMI of 35.7, as compared to 30.9 among THA patients (p < 0.001). By extension, the distribution of BMI classifications was also different between the groups, with TKA patients more likely to be obese than THA patients (X2 = 45.02, P < 0.001).

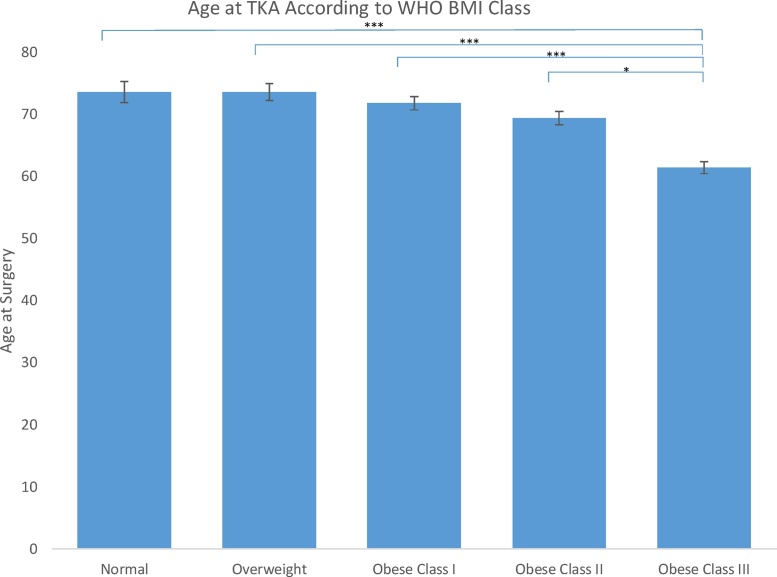

Further analysis of TKA patients (Table 2) revealed a significant negative association between WHO BMI class and age at surgery (p < 0.001, Fig. 1). Post-hoc analysis revealed that class III obese patients were significantly younger than patients in any other group at surgery (p < 0.001 compared to all other groups). While normal weight patients were 73.6 years old, on average, at the time of surgery, the average class III obese patient was 61.4 years old. Linear regression revealed that in this patient series, increasing BMI by 1 kg/m2 decreased the age at TKA by 0.56 years. Increasing BMI classification was not significantly associated with risk of mortality score, severity of illness score, or length of stay (P > 0.05 for all). A comparison of obese patients with non-obese patients revealed a significant difference between the ethnic identities of each patient population (X2 = 12.152, P = 0.016). Obese patients were significantly less likely to be white non-Hispanics than non-obese patients undergoing TKA. In contrast, a comparison of the ethnic identities of patients with BMI > 40 to those of patients with BMI < 40 did not reveal a difference between the two groups (p = 0.48). Finally, increasing WHO BMI class led to an increased proportion of patients with diabetes (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of TKA Patients Grouped by WHO BMI Class.

| Normal Weight (BMI 18.5-24.9) | Overweight (BMI 25-29.9) | Obese Class I (BMI 30-34.9) | Obese Class II (BMI 30-34.9) | Obese Class III (BMI 30-34.9) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Patients | 36 (100%) | 50 (100%) | 63 (100%) | 79 (100%) | 109 (100%) | n/a |

| Age at Surgery | 73.6 ± 10.3 | 73.6 ± 9.6 | 71.8 ± 8.5 | 69.4 ± 9.4 | 61.4 ± 9.8 | <0.001 |

| Length of Stay (Days) | 5.9 ± 7.2 | 5.2 ± 3.3 | 5.2 ± 4.3 | 4.7 ± 4.2 | 4.6 ± 2.4 | 0.07 |

| Risk of Mortality Index | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 0.06 |

| Severity of Illness Index | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 0.17 |

| Diabetes | 4 (11.1%) | 15 (30.0%) | 26 (41.3%) | 44 (55.7%) | 50 (45.9%) | <0.001 |

| Race | Racial Composition X2 Analysis P = 0.016 (obese vs non-obese) P = 0.48 (BMI > 40 vs BMI < 40) |

|||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 18 (50.0%) | 27 (54.0%) | 27 (42.9%) | 30 (38.0%) | 42 (38.5%) | |

| Black, non- Hispanic | 15 (41.7%) | 18 (36.0%) | 32 (50.8%) | 43 (54.4%) | 61 (56.0%) | |

| Asian | 2 (5.6%) | 3 (6.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.5%) | 1 (0.9%) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.8%) | 1 (2.0%) | 2 (3.2%) | 2 (2.5%) | 2 (1.8%) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 2 (3.2%) | 2 (2.5%) | 3 (2.8%) |

Analysis of patient populations undergoing total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty. Continuous variables were compared using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc testing performed using paired t-tests with Bonferroni’s correction, while categorical variables were compared using chi-squared tests. All categorical variables are presented as N (% of total in BMI class). All continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Fig. 1.

Age (in years) at the time of primary TKA according to BMI Class. Significance thresholds: * – p < 0.05; ** – p < 0.01; *** – p < 0.001.

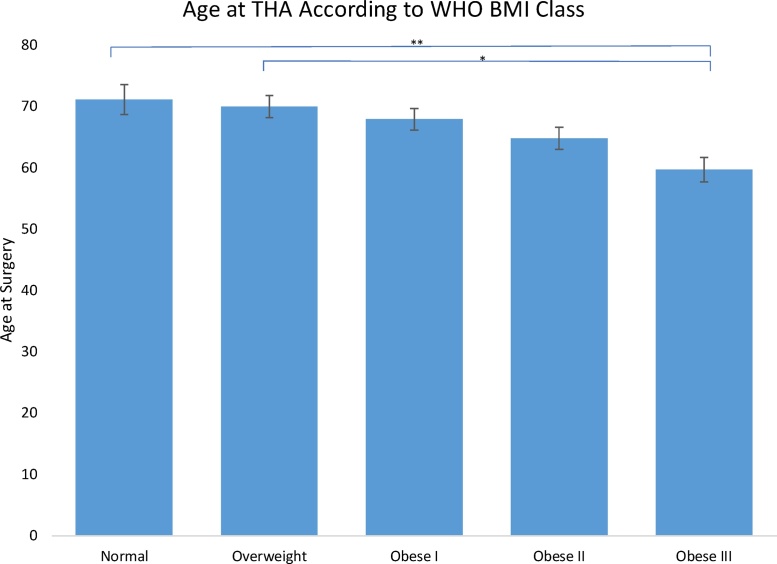

Further analysis of THA patients (Table 3) also revealed a negative association between BMI class and age at surgery (p < 0.001, Fig. 2). Post-hoc analysis revealed that, among THA patients, class III obese patients were significantly younger when they received surgery than normal weight (p = 0.004) and overweight patients (p = 0.016). Class III obese patients were 59.7 years old at surgery, on average, compared to an average age of 71.1 among normal weight patients. In this patient group, patient age at THA decreased by 0.52 years for each 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI. Body Mass Index classification was not significantly associated with risk of mortality score or length of stay (P > 0.05 for all), although it was associated with an increased severity of illness index (p = 0.03). Post-hoc analysis revealed that class III obese patients had significantly higher severity of illness index scores than overweight patients (p = 0.02). A comparison of obese patients with non-obese patients did not reveal a difference in the ethnic identities of THA patients (p = 0.474). In contrast, comparing patients with BMI > 40 to patients with BMI < 40 revealed a difference in ethnic identifies between the two groups (p = 0.007), with class III obese patients significantly less likely to be non-Hispanic white than patients who were not class III obese. Post-hoc analysis did not reveal significant differences between groups. Finally, increasing WHO BMI class led to an increased proportion of patients with diabetes (p = 0.02).

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty grouped by WHO BMI Class.

| Normal Weight (BMI 18.5-24.9) | Overweight (BMI 25-29.9) | Obese Class I (BMI 30-34.9) | Obese Class II (BMI 30-34.9) | Obese Class III (BMI 30-34.9) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Patients | 53 (100%) | 57 (100%) | 53 (100%) | 37 (100%) | 31 (100%) | n/a |

| Age at Surgery | 71.1 ± 17.8 | 70.0 ± 13.5 | 67.9 ± 12.7 | 64.8 ± 10.9 | 59.7 ± 11.0 | <0.001 |

| Length of Stay (Days) | 5.9 ± 3.4 | 5.5 ± 5.6 | 4.9 ± 2.9 | 5.1 ± 2.9 | 4.7 ± 3.5 | 0.13 |

| Risk of Mortality Index | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 0.36 |

| Severity of Illness Index | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 0.03 |

| Diabetes | 6 (11.3%) | 13 (22.8%) | 14 (26.4%) | 14 (37.8%) | 12 (38.7%) | 0.02 |

| Race | Racial Composition X2 Analysis P = 0.474 (obese vs non-obese) P = 0.007 (BMI > 40 vs BMI < 40) |

|||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 32 (60.4%) | 35 (61.4%) | 33 (62.3%) | 15 (40.5%) | 12 (38.7%) | |

| Black, non- Hispanic | 15 (28.3%) | 20 (35.1%) | 16 (30.2%) | 19 (51.4%) | 17 (54.8%) | |

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (5.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 3 (5.7%) | 1 (1.8%) | 2 (3.8%) | 2 (5.4%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Analysis of patient populations undergoing total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty. Continuous variables were compared using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc testing performed using paired t-tests with Bonferroni’s correction, while categorical variables were compared using chi-squared tests. All categorical variables are presented as N (% of total in BMI class). All continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Fig. 2.

Age (in years) at the time of primary THA according to BMI Class. Significance thresholds: * – p < 0.05; ** – p < 0.01; *** – p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

Our analysis revealed differences between knee and hip replacement patients, the effect of obesity on the age at joint replacement, higher rates of diabetes in obese patients undergoing TJA, and the differing racial backgrounds among TJA patients in different BMI classes. We confirmed our hypothesis that obese patients would undergo TJA earlier than non-obese patients and that obese patients had a different racial composition than non-obese patients, with obese patients less likely to be non-Hispanic whites.

An analysis of the populations of obese and non-obese patients undergoing TJA revealed a highly significant association between obesity and earlier joint replacement. This trend is well established in the literature, and this study further confirms the association. In this study, we determined that an increase of BMI by 1 kg/m2 decreased the age at TKA by 0.56 years and decreased the age at THA by 0.52 years. The average age at surgery for TKA replacement was 73.6 among normal weight patients, as opposed to 61.4 among class III obese patients – a 12.2-year difference. Among THA patients, the average age was 71.1 among normal weight patients and 59.7 among class III obese patients, meaning class III obese patients received hip replacements 11.4 years earlier than those in the normal weight BMI range.

These results align with those of past studies of BMI and age at joint replacement. Changulani et al.9 studied 1,025 THA and 344 TKA patients and reported that class III obese THA patients had surgery 10 years younger than normal weight patients, and the difference was 13 years for TKA patients. Similarly, Gandhi et al.10 found that THA and TKA patients with BMI > 35 had surgery 7.1 and 7.9 years earlier, respectively, than the same procedure in patients with BMIs in the normal range. Recently, Vulcano et al.11 studied 4,718 TKA patients and found that class III obesity patients were having surgery 7 years earlier than those of normal weight. While the magnitude of the effect has varied slightly between trials, the link between increased BMI and earlier TJA is strongly supported by the data.

Our study has socioeconomic implications. These data suggest that a significantly higher proportion of obese patients undergoing BMI will still be of a working age when they undergo surgery. Age at surgery has been identified as a major predictor of return to work following TJA, with a younger age at the time of surgery strongly associated with increased return to work.12 Currently, the average age at retirement in the United States is 64 for men and 62 for women, both of which are higher than the age at TJA in class III obese patients.13 Thus, these patients could be more likely than older patients to return to the labor market following their surgery. A few investigators have examined the effects of BMI on return to work following TJA. One study reported a lower rate of return to work following TJA in obese patients,14 while two others reported no association between BMI and return to work.12,15 This area warrants further investigation, as the labor market activity of obese patients following TJA is of important societal consequences.

We found that a substantial majority of the patients undergoing TKA were female, which aligns with the literature.11,16 A possible explanation of this finding is suggested by the epidemiology of obesity. In the United States, obesity is more prevalent among women than among men,1 and the rate of class III obesity is nearly twice as high in women as in men.17 Since class III obesity increases the relative risk of TKA by a factor of 32.7,6 the higher prevalence of class III obesity in women as compared to men could explain the higher rates of TKA. In our cohort, 74.5% of patients undergoing TKA were obese, as opposed to 52.4% of those undergoing THA. Obesity increases the risk of TKA by significantly more than it increases the risk of THA,6 suggesting a plausible explanation for this finding.

We also found an association between obesity at the time of TJA and the proportion of patients with diabetes. Among TKA patients, 11.1% of normal weight patients had diabetes, while 55.7% and 45.9% of class II and III obese patients, respectively, were diabetic. Among THA patients, 11.3% of normal weight patients had diabetes, while 37.8% and 38.7% of class II and III obese patients, respectively, were diabetic. Vulcano et al. reported similar results among their population of TKA patients.11 This result is not surprising, as obesity and diabetes are strongly linked throughout the medical literature.18

Since obesity does not affect all groups equally, it follows that groups with more obesity may require more joint replacements. However, it is well established that significant racial and ethnic disparities exist in the healthcare system.19 In the face of increased discussion about the relative risk/benefit ratio of performing joint replacements in patients with especially high BMI,20 it is important to understand the patients affected by these decisions. BMI cutoffs have been imposed on TJA in the past (albeit not in the United States),21 and if such policies were implemented, health disparities might be exacerbated. Another finding in our analysis was the link between BMI and the racial composition of patients undergoing TJA. In our population of TKA patients, we found that obese patients had significantly different racial backgrounds than non-obese patients by chi-squared analysis. However, we found no difference between the racial composition of the class III obese patient population and patients who were not class III obese. By contrast, among THA patients, we found no differences between the racial composition of obese and non-obese patient populations, but class III obese patients were significantly more likely than all other patients to be races other than non-Hispanic white. While the results were not perfectly uniform, overall we corroborate the analysis of Vulcano et al.11 who found a positive relationship between BMI and non-white race among TKA patients. Our findings among TKA patients may be explained, in part, by the increased prevalence of obesity among non-white Americans as compared to white Americans.1 Among THA patients, we only found a significant association between BMI and non-white race when comparing class III obese patients to all other patients. These findings may have been limited by our sample size, and they warrant validation in a larger cohort. However, our database suggests differences in the racial composition of obese and non-obese patients undergoing TJA, as well as suggesting that these differences may not be the same for TKA and THA.

This study examined the relationship between BMI and demographic variables with respect to age at the time of TJA. These findings have implications for access to care. A growing body of literature is emerging linking increased BMI, particularly class II/III BMI, to increased complication rates following TJA.20,22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 As such, physicians are increasingly cautious about performing surgery on class III obese patients, with patients being counseled to lose weight prior to joint replacement.20,29 While these patients clearly face higher surgical risk, studies have also found that delaying arthroplasty can lead to increased costs and decreased physical function prior to surgery.30 Additionally, obese patients tend to have worse pain and function scores prior to surgery, but they improve more dramatically than non-obese patients following joint replacement.31,32 Taken together, obese patients are more likely to be of working age at the time they undergo surgery and more likely to be non-white. These patient groups may stand to benefit equally from joint replacement, and the influence on socioeconomic variables, including return to work, must be closely examined in future studies.

5. Conclusions

Obesity is a risk factor for both TKA and THA at a younger age. For patients in the study, for each unit increase in BMI, the age at TKA decreased by 0.56 years, and age at THA decreased by 0.52 years. On average, a class III obese patient underwent TKA 12.2 years earlier or THA 11.4 years earlier than a normal weight patient. Obese patients undergoing THA and TKA were more likely to have diabetes than normal weight patients. Obese TJA patients were less likely to be non-Hispanic whites than non-obese patients.

Conflict of interest statements

Mr. Brock reports personal fees and other from EDGe Surgical Inc., personal fees and other from Innoblative Designs, Inc. outside the submitted work.

Dr. Kamath reports grants and personal fees from Zimmer Biomet, grants and personal fees from DePuy Synthes, outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Ogden C.L., Carroll M.D., Fryar C.D., Flegal K.M. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2015. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief, No 219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon J.B. The effect of obesity on health outcomes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316(2):104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kushner R.F., Kahan S. The state of obesity in 2017. Med Clin North Am. 2017;102:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Upadhyay J., Farr O., Perakakis N., Ghaly W., Mantzoros C. Obesity as a disease. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:13–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammond R.A., Levine R. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2010;3:285–295. doi: 10.2147/DMSOTT.S7384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourne R., Mukhi S., Zhu N., Keresteci M., Marin M. Role of obesity on the risk for total hip or knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;465(465):185–188. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3181576035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh J.A., Lewallen D.G. Increasing obesity and comorbidity in patients undergoing primary total hip arthroplasty in the U.S.: A 13-year study of time trends. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15(441) doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2000. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report on a WHO consultation (WHO technical report series 894) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Changulani M., Kalairajah Y., Peel T., Field R.E. The relationship between obesity and the age at which hip and knee replacement is undertaken. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2008;90(3):360–363. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B3.19782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandhi R., Wasserstein D., Razak F., Davey J.R., Mahomed N.N. BMI independently predicts younger age at hip and knee replacement. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(12):2362–2366. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vulcano E., Lee Y.Y., Yamany T., Lyman S., Della Valle A.G. Obese patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty have distinct preoperative characteristics: an institutional study of 4718 patients. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1125–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott C.E.H., Turnbull G.S., MacDonald D., Breusch S.J. Activity levels and return to work following total knee arthroplasty in patients under 65 years of age. Bone Jt J. 2017;99-B(8):1037–1046. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B8.BJJ-2016-1364.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Average retirement age leveling off.” ThinkAdvisor, March 4 2015. General OneFile. http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A404009097/ITOF?u=upenn_main&sid=ITOF&xid=2e6ab60d. Accessed 12 December, 2017.

- 14.Kuijer P.P.F.M., Kievit A.J., Pahlplatz T.M.J. Which patients do not return to work after total knee arthroplasty? Rheumatol Int. 2016;36(9):1249–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3512-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leichtenberg C.S., Tilbury C., Kuijer P.P.F.M. Determinants of return to work 12 months after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98(6):387–395. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guenther D., Schmidl S., Klatte T. Overweight and obesity in hip and knee arthroplasty: evaluation of 6078 cases. World J Orthop. 2015;6(1):137. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flegal K.M., Carroll M.D., Kit B.K., Ogden C.L. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg S.K., Maurer H., Reed K., Selagamsetty R. Diabetes and cancer: two diseases with obesity as a common risk factor. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(2):97–110. doi: 10.1111/dom.12124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2002. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryan D., Parvizi J., Austin M. Obesity and total joint arthroplasty: a literature based review. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(5):714–721. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coombes R. Rationing of joint replacements raises fears of further cuts. BMJ. 2005;331(7528):1290. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7528.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deakin A.H., Iyayi-Igbinovia A., Love G.J. A comparison of outcomes in morbidly obese, obese and non-obese patients undergoing primary total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Surgeon. 2017:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stickles B., Phillips L., Brox W.T., Owens B., Lanzer W.L. Defining the relationship between obesity and total joint arthroplasty. Obes Res. 2001;9(3):219–223. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu W., Wahafu T., Cheng M., Cheng T., Zhang Y., Zhang X. The influence of obesity on primary total hip arthroplasty outcomes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101(3):289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali A.M., Loeffler M.D., Aylin P., Bottle A. Factors associated with 30-day readmission after primary total hip arthroplasty: analysis of 514,455 procedures in the UK National Health Service. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(12):e173949. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3949. [Epub 2017 Dec 20] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodnough L.H., Finlay A.K., Huddleston J.I., Goodman S.B., Maloney W.J., Amanatullah D.F. Obesity is independently associated with early aseptic loosening in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(3):882–886. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.George J., Piuzzi N.S., Ng M., Sodhi N., Khlopas A.A., Mont M.A. Association between body mass index and thirty-day complications after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(3):865–871. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zusmanovich M., Kester B.S., Schwarzkopf R. Postoperative complications of total joint arthroplasty in obese patients stratified by BMI. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(3):856–864. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wooten C., Curtin B. Morbid obesity and total joint replacement: is it okay to say no? Orthopedics. 2016;39(4):207–209. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20160628-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fielden J.M., Cumming J.M., Horne J.G., Devane P.A., Slack A., Gallagher L.M. Waiting for hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(8):990–997. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collins R.A., Walmsley P.J., Amin A.K., Brenkel I.J., Clayton R.A.E. Does obesity influence clinical outcome at nine years following total knee replacement? J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2012;94(10):1351–1355. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B10.28894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li W., Ayers D.C., Lewis C.G., Bowen T.R., Allison J.J., Franklin P.D. Functional gain and pain relief after total joint replacement according to obesity status. J Bone Jt Surg. 2017;99(14):1183–1189. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]