Abstract

Although autologous human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) are a promising source for regenerative stem cell therapy in chronic kidney disease (CKD), the barriers associated with pathophysiological conditions limit therapeutic applicability to patients. We confirmed that level of cellular prion protein (PrPC) in serum was decreased and mitochondria function of CKD-derived hMSCs (CKD-hMSCs) was impaired in patients with CKD. We proved that treatment of CKD-hMSCs with tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), a bile acid, enhanced the mitochondrial function of these cells through regulation of PINK1-PrPC-dependent pathway. In a murine hindlimb ischemia model with CKD, tail vein injection of TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs improved the functional recovery, including kidney recovery, limb salvage, blood perfusion ratio, and vessel formation along with restored expression of PrPC in the blood serum of the mice. These data suggest that TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs are a promising new autologous stem cell therapeutic intervention that dually treats cardiovascular problems and CKD in patients.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Mesenchymal stem cell, Tauroursodeoxycholic acid, Cellular prion protein, PINK1, Mitochondria, Mitophagy

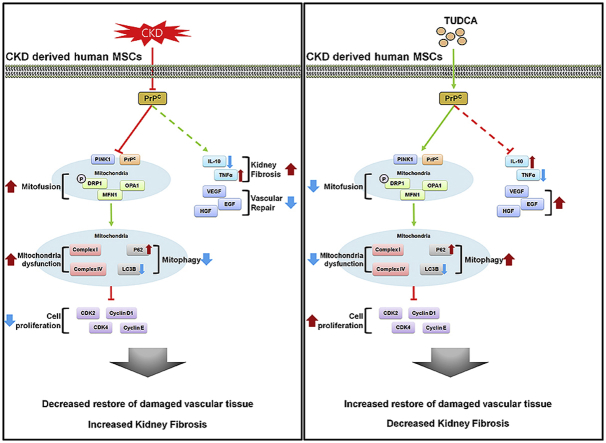

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Despite the advancement of therapeutic research, chronic kidney disease (CKD) remains a huge public health burden, afflicting approximately 7.7% of the US population [1]. Patients with CKD fail to excrete toxic metabolites and organic waste solutes that are normally removed by healthy kidneys, with the resultant accumulation of such toxins in these patients and significantly increased risks of other diseases including anemia, metabolic bone disease, neuropathy, and cardiovascular disease [[2], [3], [4]]. Vascular diseases (VDs) remain a major problem frequently associated with CKD, and mortality among individuals with CKD is attributable more to secondary vascular damage than to actual kidney failure [5]. VDs in patients with CKD are traditionally known to be caused by increased risks of arterial hypertension due to aberrations in CKD, but recent research shows evidence of novel risk factors such as premature senescence, decreased proliferation, and apoptosis of cardiovascular cell types in relevant tissues owing to oxidative stress induced by uremic toxins circulating in the serum of patients with CKD [6]. Despite the overbearing burden, currently available therapies for CKD often lead to adverse side effects and malignant pharmacokinetic changes [7].

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), a subcategory of adult stem cells, possess excellent therapeutic potentials because of their ability to secrete reparative factors and cytokines, their capacity for tissue-specific differentiation, and their self-renewal ability, especially apt for organ regeneration and tissue repair [8]. In particular, some studies have delineated the benefits of MSC therapy as a promising modality targeting VD associated with CKD [9,10]. The paracrine effect of MSCs, include cell migration, homing, and stimulation, and anti-apoptosis, and anti-oxidative factor for repair damaged tissue, as well as the therapeutic potentials of MSCs related to neovascularization, making MSCs a promising cell source with strong regenerative as well as modulatory abilities for alleviation of both renal and vascular complications [8,10,11]. Nonetheless, one of the major drawbacks of MSC therapy is that MSCs obtained from patients with CKD are exposed to endogenous uremic toxins that decrease their viability and therapeutic potential [12].

Tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TDUCA) is a bile acid produced in humans in small amounts and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to be safely used as a drug for human intake [13]. Cellular prion protein (PrPC), a glycoprotein commonly known to pathogenically misfold into PrPSC (which causes neurodegenerative disorders [14,15]) plays vital metabolic roles in the body such as regulation of cell differentiation, cell migration, and long-term potentiation of synapses [[16], [17], [18]]. Furthermore, PrPC possesses a therapeutic function: it increases survival of MSCs, and one study has shown that PrPC is essential for reducing the oxidative stress at the injury site of an ischemia model [13]. More specifically, some studies have suggested that PrPC may play a role in mitochondrial functions involving levels of oxidative stress and mitochondrial morphology [19,20], and TUDCA has been shown to be neuroprotective in a model of acute ischemic stroke via stabilization of the mitochondrial membrane [21,22]. Nevertheless, the precise mechanism by which TUDCA potentiates MSCs via PrPC-dependent enhancement of mitochondrial function is not yet investigated.

In our study, we aimed to elucidate the therapeutic benefits of TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs for targeting VD associated with CKD. We investigated the precise mechanism via which TUDCA enhanced the survival of CKD-hMSCs in CKD-associated VD: through enhancement of mitochondrial activity via the PrPC–PINK1 axis. We hypothesized that PrPC is a protein of interest for the treatment of patients with VD associated with CKD, and that PrPC-mediated mitochondrial recovery from oxidative stress (common in patients with CKD) is a crucial factor for therapeutic targeting of CKD-related VD.

2. Methods

2.1. Serum of patients with CKD and the healthy control

The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from all the study subjects. Explanted serum (n = 25; CKD-patient) and the healthy control fulfilling transplantation criteria (n = 10; Healthy control) were obtained from the Seoul national hospital in Seoul, Korea (IRB: SCHUH 2018-04-035). All CKD diagnoses was defined as abnormalities of kidney function as measure estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 25 ml/min/1.73 m2 over 3 months (stage 3b–5).

2.2. Human healthy MSCs and human CKD MSCs cultures

Human adipose tissue-derived healthy-hMSCs (n = 4) and CKD-hMSCs (n = 4) were obtained from Soonchunhyang University Seoul hospital (IRB: SCHUH 2015-11-017). We defined CKD as impaired kidney function according to estimated [eGFR] <35 ml/(min⋅1.73 m2) for more than 3 months (stage 3b). The supplier certified the expression of MSC surface positive markers CD44, and Sca-1, and negative marker CD45, and CD11b. MSCs were differentiated into chondrogenic, adipogenic, and osteogenic cells under specific differentiation media condition, respectively. Healthy hMSCs and CKD-hMSCs were cultured in α-Minimum Essential Medium (α-MEM; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) of fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco BRL) and a 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco BRL). Healthy-hMSCs and CKD-hMSCs were grown in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C.

2.3. Detection of PrPC in serum or cell media

Concentrations of PrPC in the human healthy control group or CKD patient group, or in a cell lysate of untreated healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs with TUDCA, or in healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs treated with TUDCA were determined with a commercially available ELISA kit (Lifespan Biosciences, Seattle, WA, USA). Next, 100 μL from each serum group or cell media group was used for these experiments. Triplicate measurements were performed in all ELISAs. Expression levels of PrPC were quantified by measuring absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany).

2.4. Mitochondrial-fraction preparation

Harvested healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs were lysed in mitochondria lysis buffer and were subsequently incubated for 10 min on ice. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 3000 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected as a cytosol fraction. The residual pellet was lysed with RIPA lysis buffer and then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm and 4 °C for 30 min.

2.5. Western blot analysis

The whole cell lysates, cytosol fraction lysates, or mitochondrial lysates from healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs (30 μg protein) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in an 8–12% gel, and the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. After the blots were washed with TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20), the membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies: against PrPC, MFN1, or β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), PINK1, OPA1, P62, LC3B, and VDAC1 (NOVUS, Littleton, CT, USA), and p-DPR1 (Cell signaling, Danvers, MA, USA). The membranes were then washed, and the primary antibodies were detected by means of goat anti-rabbit IgG or goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK).

2.6. Immunoprecipitation

The mitochondrial fraction of healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs was lysed with lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100 in 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], containing 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 2.5 mM Na4PO7, 100 mM NaF, and protease inhibitors). Mitochondrial lysates (200 μg) were mixed with an anti-PINK1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The samples were mixed with the Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose Immunoprecipitation Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4 °C for incubation over 4 h, and incubated additionally at 4 °C for 12 h. The beads were washed four times, and the bound protein was released from the beads by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer for 7 min. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by western blotting with an anti-PrPC antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

2.7. Measurement of mitochondrial O2•− production, and mitochondrial membrane potential

To measure the formation of mitochondrial O2•−, the mitochondrial superoxide of healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs was measured by means of MitoSOX™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), or TMRE (abcam, Cambridge, UK). These cells were trypsinized for 5 min and then centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 3 min, washed with PBS twice and then incubated with a 10 μM MitoSOX™ solution or 200 nM TMRE solution in PBS at 37 °C for 15 min. After that, the cells were washed more than 2 times with PBS. Next, we resuspended these cells in 500 μL of PBS, and then detected the signals with MitoSOX™ or TMRE by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS; Sysmex, Kobe, Japan). Cell forward scatter levels were determined in MitoSOX™-positive cells, analyzed by means of the Flowing Software (DeNovo Software, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

2.8. Cell cycle analysis

Healthy-hMSCs, TUDCA-treated healthy-hMSCs, CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs after treatment with si-PRNP, or TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs after treatment with si-Scr were harvested and fixed with 70% ethanol at −20 °C for 2 h. After two washes with cold PBS, the cells were subsequently incubated with RNase and the DNA-intercalating dye propidium iodide (PI; Sysmex) at 4 °C for 1 h. Cell cycle of the PI-stained cells was characterized by flow cytometry (Sysmex). Events were recorded for at least 104 cells per sample. The sample data were analyzed in the FCS express 5 software (DeNovo Software). Independent experiments were repeated 3 times.

2.9. Electron microscopy

For this purpose, the cells were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at pH 7.3. Morphometric analyses (the number of mitochondria per cell and mitochondrial size) were performed in ImageJ software (NIH; version 1.43). At least 10 cells from low-magnification images (×10,000) were used to count the number of mitochondria per hMSCs (identified by the presence of lamellar bodies). At least 100–150 individual mitochondria, from 3 different lungs per group at high magnification (×25,000 and ×50,000), were used to assess the perimeter and the area.

2.10. Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was examined by a 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay. MSCs were cultured in 96-well culture plates (3,000 cells/well). BrdU incorporation into newly synthesized DNA of proliferating cells was assessed by an ELISA colorimetric kit (Roche, Basel, Swiss). To perform the ELISA, 100 μg/ml BrdU was added to MSC cultures and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. An anti-BrdU antibody (100 μL) was added to MSC cultures and incubated at room temperature for 90 min. After that, 100 μL of a substrate solution was added and 1 M H2SO4 was employed to stop the reaction. Light absorbance of the samples was measured on a microplate reader (BMG Labtech) at 450 nm.

2.11. Kinase assays of complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities and CKD4/Cyclin D1 activity

The cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Activity of complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ and CDK4 kinase assays were performed by means of each the CKD4 Kinase Assay Kit (Cusabio, Baltimore, USA) and complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ assays (abcam). Total cell lysate (30–50 μg) was subjected to these experiments. Activation of complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ and CDK4 kinase assays quantified by measuring absorbance at 450 nm on a microplate reader (BMG).

2.12. Co-culture of human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells with Healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs

Healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs and THP-1 cells were co-cultured in Millicell Cell Culture Plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), in which culture media are in indirect contact with cells. TH-1 cells were seeded in the lower compartments, and then exposed to P-cresol for 24 h, and then healthy-hMSCs, CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs (TUDCA+CKD-hMSC), TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs treated with si-PRNP (si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC), or TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs treated with si-Scr (si-Scr+CKD-hMSC) were seeded onto the transwell membrane inserts for incubation for 48 h. They were incubated in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% of CO2 at 37 °C. TH-1 cell proliferation, expression of PrPC, MitoSOX, and complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities were assessed as described above for the proliferation assay, ELISAs, and FACS analysis.

2.13. Detection of PrPC in cell lysates

Concentrations of PrPC in TH-1 cells incubated with or without P-cresol alone or co-cultured with one of the following cell types—healthy-hMSCs, CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs, si-PRNP+CKD-hMSCs, or si-Scr+CKD-hMSCs—were determined using a commercially available ELISA kit (Lifespan Biosciences). Total protein (30 μg) from each group of TH-1 cell lysates was subjected to these experiments. Triplicate measurements were performed in all ELISAs. Expression levels of PrPC were quantified by measuring absorbance at 450 nm on a microplate reader (BMG Labtech).

2.14. Ethics statement

All animal care procedures and experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital (IACUC2013-5) and were performed in accordance with the National Research Council (NRC) Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The experiments were performed on 8-week-male BALB/c nude mice (Biogenomics, Seoul, Korea) maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle at 25 °C in accordance with the regulations of Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital.

2.15. The CKD model

Eight-week-old male BALB/c nude mice were fed an adenine-containing diet (0.25% adenine in diet) for 1–2 weeks [23]. Mouse body weight was measured every week. The mice were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 groups consisting of 10 mice in each group. After euthanasia, blood was stored at −80 °C for measurement of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (Supplementary Fig. 1).

2.16. The murine hindlimb ischemia model

To induce vascular disease and to assess neovascularization in the mouse model of CKD, after adenine-loaded feeding for 1 week, the murine hind limb ischemia model was established. Ischemia was induced by ligation and excision of the proximal femoral artery and boundary vessels of the CKD mice. No later than 6 h after the surgical procedure, PBS, CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs treated with si-PRNP, or TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs treated with si-Scr in PBS were intravenously injected into a tail vein (106 cells per 100 μL of PBS per mouse; 5 mice per treatment group) of CKD mice. Blood perfusion was assessed by measuring the ratio of blood flow in the ischemic (left) limb to that in the non-ischemic (right) limb on postoperative days 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 by laser Doppler perfusion imaging (LDPI; Moor Instruments, Wilmington, DE).

2.17. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson's trichrome, and immunohistochemical staining

At 25 days after the operation, the ischemic thigh tissues were removed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma), and each tissue sample was embedded in paraffin. For histological analysis, the samples were stained with H&E, or Masson's trichrome in kidney tissues to determine fibrosis and histopathological features, respectively. Immunofluorescence staining was performed with primary antibodies against CD11b (abcam), CD31 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and α-SMA (alpha-smooth muscle actin; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diaminido-2-phenylindol (DAPI; Sigma), and the immunostained samples were examined by confocal microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

2.18. Detection of human growth factors

Concentrations of VEGF, FGF, and HGF in hindlimb ischemia–associated CKD tissue lysates were determined with commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). On postoperative day 3, 300 μg of total protein from hindlimb ischemia tissue lysates was subjected to these experiments. Triplicate measurements were carried out in all the ELISAs. Expression levels of growth factors were quantified by measuring absorbance at 450 nm on the microplate reader (BMG Labtech).

2.19. Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and evaluated by Two-tailed Student's t-test was used to compute the significance between the groups, or one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Comparisons of three or more groups were made by using Dunnett's or Tukey's post-hoc test. Data were considered significantly different at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patients with CKD have lower levels of serum PrPC, and CKD patient–derived MSCs show decreased mitochondrial activity

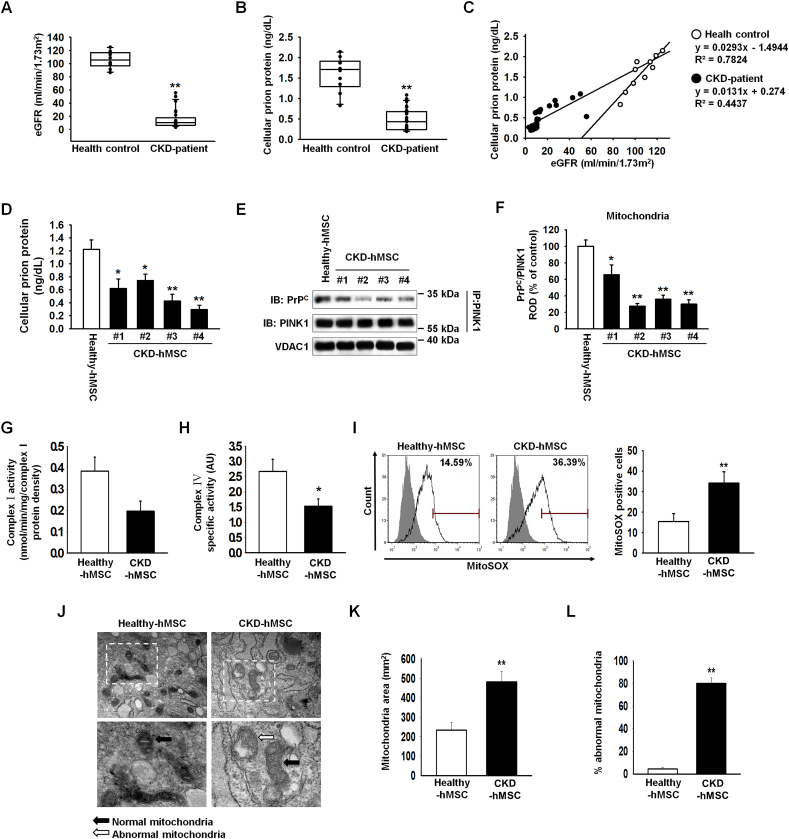

To analyze biomarkers of CKD, we measured estimated glomerular filtration rate in the serum of the patients with CKD (n = 25, Healthy control; n = 10). We confirmed that our patients with CKD were at stage 3b–5 (average estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR): 22.4; Fig. 1A). In patients with CKD, ELISA results revealed a decreased level of PrPC in serum (Fig. 1B). Patients with CKD showed a decreased slope on the eGFR axis against concentration on PrPC axis as compared to the healthy control group (Fig. 1C). Thus, we investigated whether the reduced expression of PrPC may be related to CKD. It has been known that mitochondrial PrPC maintains mitochondrial activity and reduces accumulation of ROS to retain activity of the electron transport chain complex [19,24,25]. To confirm obtained MSCs from healthy and patient group sustained similar normally MSCs, we progressed differentiate into chondrogenic, adipogenic, and osteogenic cells, and measured surface marker CD11b, and CD45-negative control, and CD44, and Sca-1, positive control (Supplementary Fig. 2A–C). In contrast to healthy-hMSCs, CKD-hMSCs (n = 4) showed decreased expression of PrPC by using ELISA (Fig. 1D). CKD-hMSCs (n = 4) also had weaker binding of PrPC to PINK1 (Fig. 1D, F). These results indicate that CKD-hMSCs might mediate mitochondrial dysfunction by decreased binding of PrPC and PINK1. To confirm that mitochondrial dysfunction in CKD-hMSCs (n = 3) is caused by decreased mitochondrial PrPC levels, we analyzed accumulated ROS in mitochondria and complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities by ELISAs and FACS. CKD-hMSCs accumulated more O2•− (superoxide) in mitochondria according to the MitoSOX assay and showed decreased complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities (Fig. 1G–I). We also found that CKD-hMSCs contained increased numbers of abnormal mitochondria and increased mitochondrial area, which indicated greater mitofusion, according to transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Fig. 1J–L). To confirm that mitochondrial dysfunction was dependent on mitochondrial PrPC, we demonstrated that a knockdown of PrPC in healthy-hMSCs increased mitochondrial O2•− (superoxide) amounts and decreased complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities because of decreased PrPC binding to PINK1 (Supplementary Fig. 3A–D). Our results certainly indicate that in patients with CKD, decreased PrPC amounts influenced mitochondrial PrPC, which normally might maintain mitochondrial activity through binding to PINK1.

Fig. 1.

Patients with CKD show a decreased level of PrPC, and CKD patient–derived MSCs show decreased mitochondrial functionality. (A, B) Patients with CKD (n = 25) and healthy control groups (Healthy control; n = 10): estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and PrPC in each group in their serum (100 μL samples). Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01 vs. Healthy control. (Student's t-test was used). (C) A graph on eGFR-axis against the concentration on the PrPC-axis. (D) We measured PrPC concentrations of Healthy-hMSCs (n = 4) and CKD-hMSCs (n = 4) by ELISA. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs. (Student's t-test was used). (E) Immunoprecipitates with an anti-PINK1 antibody were analyzed for Healthy-hMSCs (n = 2) and CKD-hMSCs (n = 4) by western blotting using an antibody that recognized PrPC. (F) The level of PrPC, whose binding with PINK1 was normalized to that of VDAC1. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs. (Student's t-test was used). (G, H) Complex Ⅰ and complex Ⅳ activities were analyzed in Healthy-hMSCs and CKD-hMSCs by ELISAs. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs. (Student's t-test was used). (I) The positive signals of MitoSOX were quantified by FACS analysis with staining of Healthy-hMSCs and CKD-hMSCs. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs. (Student's t-test was used). (J) Representative TEM images (n = 3 per group) of Healthy-hMSCs and CKD-hMSCs. Scale bars are shown enlarged on the left. Scale bars: 500 nm. (K) Quantitative analyses of morphometric data from TEM images. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs. (Student's t-test was used). (L) Percentages of abnormal mitochondria that were swollen with evidence of severely disrupted cristae throughout a mitochondrion) obtained from a TEM image. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs. (Student's t-test was used).

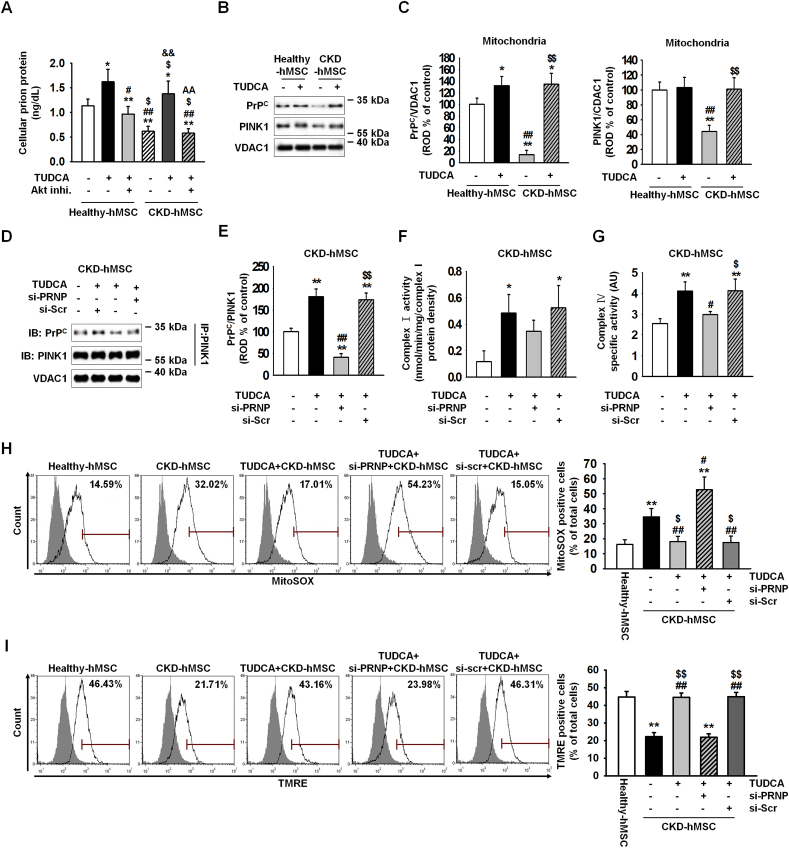

3.2. TUDCA enhances mitochondrial activity via increasing the level of mitochondrial PrPC in CKD-hMSCs

We verified that patients with CKD show low expression of PrPC. This phenomenon suggests that CKD-hMSCs may harbor decreased mitochondrial activity and increased numbers of abnormal mitochondria via a PrPC-dependent mechanism. Thus, increasing the expression of PrPC may effectively influence not only mitochondrial activity but also stem cell viability. In our previous study, we verified that TUDCA-treated MSCs are protected against ROS-induced cell apoptosis via increased Akt-PrPC signaling [13]. Nevertheless, we do not know whether TUDCA affects mitochondrial activity through increased expression of PrPC. To verify our theory, i.e., to increase PrPC expression for enhancing mitochondrial activity and stem cell therapy through treatment with TUDCA, healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs were treated with TUDCA and showed an increased level of PrPC as compared with no treatment with TUDCA. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs, particularly, showed a similar levels relative to healthy-hMSCs (Fig. 2A). However, after pretreatment heathy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs with Akt inhibitor, disappeared expression PrPC protein-induced TUDCA. These results indicate that our theory is correct: stem cell therapy with TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs should be as effective as stem cell therapy with healthy-hMSCs, therefore TUDCA regulated expression of PrPC via Akt signal pathway. We showed that TUDCA-treated healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs harbor similarly increased levels of catalase and SOD activities, which are anti-oxidative enzymes (Supplementary Fig. 4A and B). These results suggest that TUDCA increased the expression of normal cellular prion protein. To confirm that PrPC increased mitochondrial activity via treatment with TUDCA, healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs were treated with TUDCA, and we observed increased expression of PrPC in mitochondria (Fig. 2B and C). To verify mitochondrial activity and mitophagy, we measured expression of PINK1, which regulates mitochondrial membrane potential by increased complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities and is located in the outer mitochondrial membrane for initiation of mitophagy of dysfunctional mitochondria [26]. In contrast to TUDCA-treated healthy-hMSCs, TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs showed significantly increased expression of PINK1 (Fig. 2B and C). TUDCA-treated healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs manifested higher complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities as compared to the group without TUDCA treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4C and D). These results indicate that the key mechanism of TUDCA effectiveness for mitochondrial potential is mitochondrial PrPC (rather than PINK1). To confirm that TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs had better mitochondrial activity via the binding of mitochondrial PrPC to PINK1, we analyzed TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs by immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 2D and E). TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs showed increased complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities and decreased mitochondrial O2•− amounts (Fig. 2F–H). TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs also increased mitochondrial membrane potential (TMRE) by FACS (Fig. 2I). In contrast, the knockdown of PrPC in TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs increased mitochondrial O2•− levels, decreased complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities, and attenuated mitochondrial potential because of decreased binding of PrPC and PINK1 (Fig. 2F–I).

Fig. 2.

TUDCA enhanced mitochondrial membrane potential through increased mitochondrial PrPClevels in CKD-hMSCs. (A) Healthy-hMSCs (n = 3) and CKD-hMSCs (n = 3) were treated with TUDCA, and pretreatment Healthy-hMSCs and CKD-hMSCs with Akt inhibitor were treated with TUDCA. We measured concentrations of PrPC by ELISA. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs, #p < 0.05, and ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA treatment of Healthy-hMSCs, $p < 0.05 vs. after pretreatment with Akt inhibitor, treatment of Nor-hMSCs, &&p < 0.01 vs. untreated CKD-hMSCs, AAp < 0.01 vs. TUDCA treatment of CKD-hMSCs. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (B) Western blot analysis quantified the expression of PrPC and PINK1 after treatment with TUDCA of Healthy-hMSCs and CKD-hMSCs (n = 3 sample/group). (C) The expression levels were determined by densitometry relative to VACD1. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs, ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA treatment of Healthy-hMSCs, $$p < 0.01 vs. untreated CKD-hMSCs. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (D) Immunoprecipitates with anti-PINK1 were analyzed after treatment of TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs with si-PRNP by western blot using an antibody that recognized PrPC (n = 3 sample/group). (E) The level of PrPC, whose binding with PINK1 was normalized to that of VDAC1. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated CKD-hMSCs, #p < 0.05, and ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA treatment of CKD-hMSCs, $p < 0.05, and $$p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (F, G) Complex Ⅰ and complex Ⅳ activities were analyzed by an ELISA after treatment of TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs with si-PRNP. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated CKD-hMSCs, #p < 0.05, and ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA treatment of CKD-hMSCs, $p < 0.05, and $$p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (H and I) The positive signals of MitoSOX (H) and TMRE (I) were quantified by FACS analysis with staining after treatment of TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs with si-PRNP (n = 4 sample/group). Values represent the mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSCs, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA treatment of CKD-hMSCs, $p < 0.05 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test).

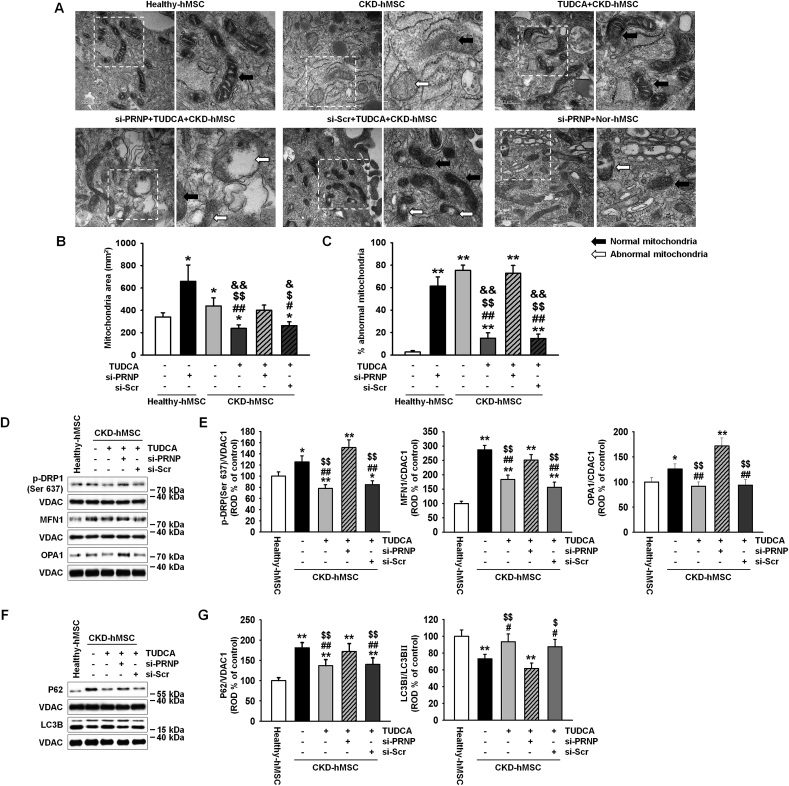

3.3. TUDCA protects CKD-hMSCs against dysfunctional mitochondria via increased mitophagy and increased cell proliferation

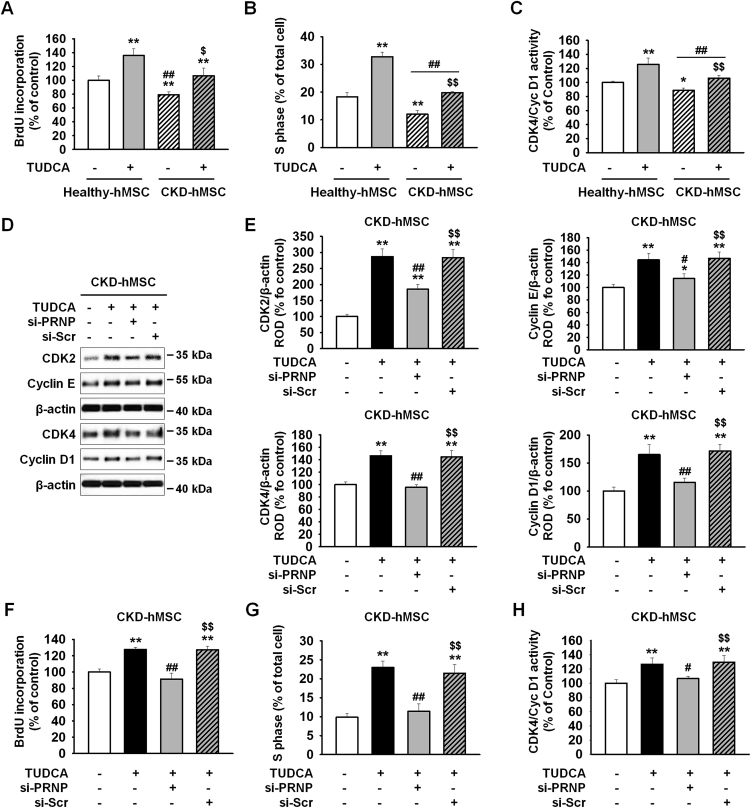

To clarify whether the reduced mitochondrial membrane potential was caused by a decrease in binding of mitochondrial PrPC to PINK1, we measured complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities and mitochondrial O2•− concentrations. These results indicate that TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs had fewer dysfunctional mitochondria. Mitophagy decreased the number of dysfunctional mitochondria, whereas mitofussion may be increased in abnormal conditions, such as CKD, inflammation, and oxidative stress, and reduces mitophagy signaling [6]. We confirmed that CKD-hMSCs contained a larger mitochondria area on cross-sections as well as abnormal mitochondria, whereas TUDCA treatment decreased the mitochondrial area and the number of abnormal mitochondria in CKD hMSCs according to TEM (Fig. 3A–C). These results indicate that the effect of TUDCA reduced dysfunctional mitochondria numbers by decreasing mitofusion and increasing mitophagy. We verified downregulation of mitofission suppressor protein p-DPR1 (phosphorylation Ser 637) and of mitofusion-associated protein MFN1, and OPA1 (regulated by p-DRP1) in TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs by western blot analysis (Fig. 3D and E). TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs also showed increased mitophagy because we analyzed autophagy-regulated proteins, P62 and LC3B, by western blotting of the mitochondrial fraction (Fig. 3D and E). In contrast, knockdown PrPC CKD-hMSCs did not respond to TUDCA and did not show enhancement of mitochondrial function according to TEM (Fig. 3A–C). TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs after a knockdown of PrPC, revealed greater activation of p-DPR1 and expression of MFN1 and OPA1 (Fig. 3D and E), and decreased mitophagy, increased expression P62, and decreased expression of LC3B Ⅱ (Fig. 3F and G). These results supported our argument that the knockdown of PrPC in healthy-hMSCs increased the mitochondrial area and numbers of abnormal mitochondria. These results indicate that TUDCA treatment of CKD-hMSCs reduced mitochondrial fission and increased mitophagy to decrease dysfunction of mitochondria. These data confirmed that TUDCA protects mitochondrial membrane potential and reduces dysfunction of mitochondria through activation of mitophagy. To analyze the increase in cell proliferation by TUDCA treatment of healthy-hMSCs and CKD-hMSCs, we conducted a BrdU assay, cell cycle assay, and evaluation of CDK4–Cyclin D1 activity (Fig. 4A–C). The knockdown of PrPC indicate that the effects of TUDCA downregulated cell cycle–associated proteins, CDK2, cyclin E, CDK4, and cyclin D1, according to western blotting (Fig. 4D and E). To analyze the attenuation of cell proliferation by the dysfunction of mitochondria, we also conducted a BrdU assay and found reduced cellular proliferation as well as the decreased S phase activity according to FACS, and CDK4/cyclin D1 activity (Fig. 4F–H). These results showed that CKD-hMSCs slowed down the proliferation due to deficiency of mitochondrial function under the influence of the PrPC knockdown and increased accumulation of mitochondrial O2•− and decreased complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities.

Fig. 3.

TUDCA regulated mitochondrial fission via increased mitochondrial PrPCamounts in CKD-hMSCs. (A) Representative TEM images (n = 3 per group) after incubation of Healthy-hMSCs with or without si-PRNP or after treatment of TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs with si-PRNP. Scale bars are shown enlarged on the left. Scale bars: 500 nm (n = 3 sample/group). (B) Quantitative analyses of morphometric data from TEM images. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP-treated Healthy-hMSCs, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSCs, &p < 0.05 and &&p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (C) Percentages of abnormal mitochondria, which were swollen with evidence of severely disrupted cristae throughout a mitochondrion) obtained from TEM images. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP-treated Healthy-hMSCs, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSCs, &p < 0.05 and &&p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (D) Western blot analysis quantified the expression of p-DRP1, MFN1, and OPA1 in Healthy-hMSCs, treatment of CKD-hMSCs with or without TUDCA, and after treatment of TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs with si-PRNP (n = 3 sample/group). (E) The expression levels were determined by densitometry relative of VACD1. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSCs, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSCs, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (F) Western blot analysis quantified the expression of P62, and LC3B in Healthy-hMSCs, treatment CKD-hMSCs with or without TUDCA, and after treatment of TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs with si-PRNP. (G) The expression levels were determined by densitometry relative to VACD1. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSCs, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSCs, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test).

Fig. 4.

TUDCA treatment of CKD-hMSCs enhanced cell proliferation through upregulation of PrPC. (A) Cell proliferation of Healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs analyzed after treatment with or without TUDCA (n = 3 sample/group). Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs, ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated Healthy-hMSCs, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs. untreated CKD-hMSCs. (two-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (B) The number of S phase Healthy-hMSCs or CKD-hMSCs was determined by FACS analysis of PI-stained cells. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs, ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated Healthy-hMSCs, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs. untreated CKD-hMSCs. (two-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (C) CKD4/Cyclin D1 activity was analyzed by ELISA. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. untreated Healthy-hMSCs, ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated Healthy-hMSCs, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs. untreated CKD-hMSCs. (two-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (D) Western blot analysis quantified the cell cycle–associated proteins, CDK2, Cyclin E, CDK4, and cyclin D1 after treatment of CKD-hMSCs with or without TUDCA, and after treatment of TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs with si-PRNP (n = 3 sample/group). (E) The expression levels were determined by densitometry relative of β-actin. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSCs, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs, $$p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (F) Cell proliferation of CKD-hMSCs analyzed after treatment of TUDCA-pretreated CKD-hMSCs with si-PRNP by a BrdU assay. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSCs, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs, $$p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (G) The number of S phase CKD-hMSCs was determined by FACS analysis of PI-stained cells. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSCs, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs, $$p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (H) CKD4/Cyclin D1 activity was analyzed by ELISA. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSCs, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs, $$p < 0.01 vs. TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test).

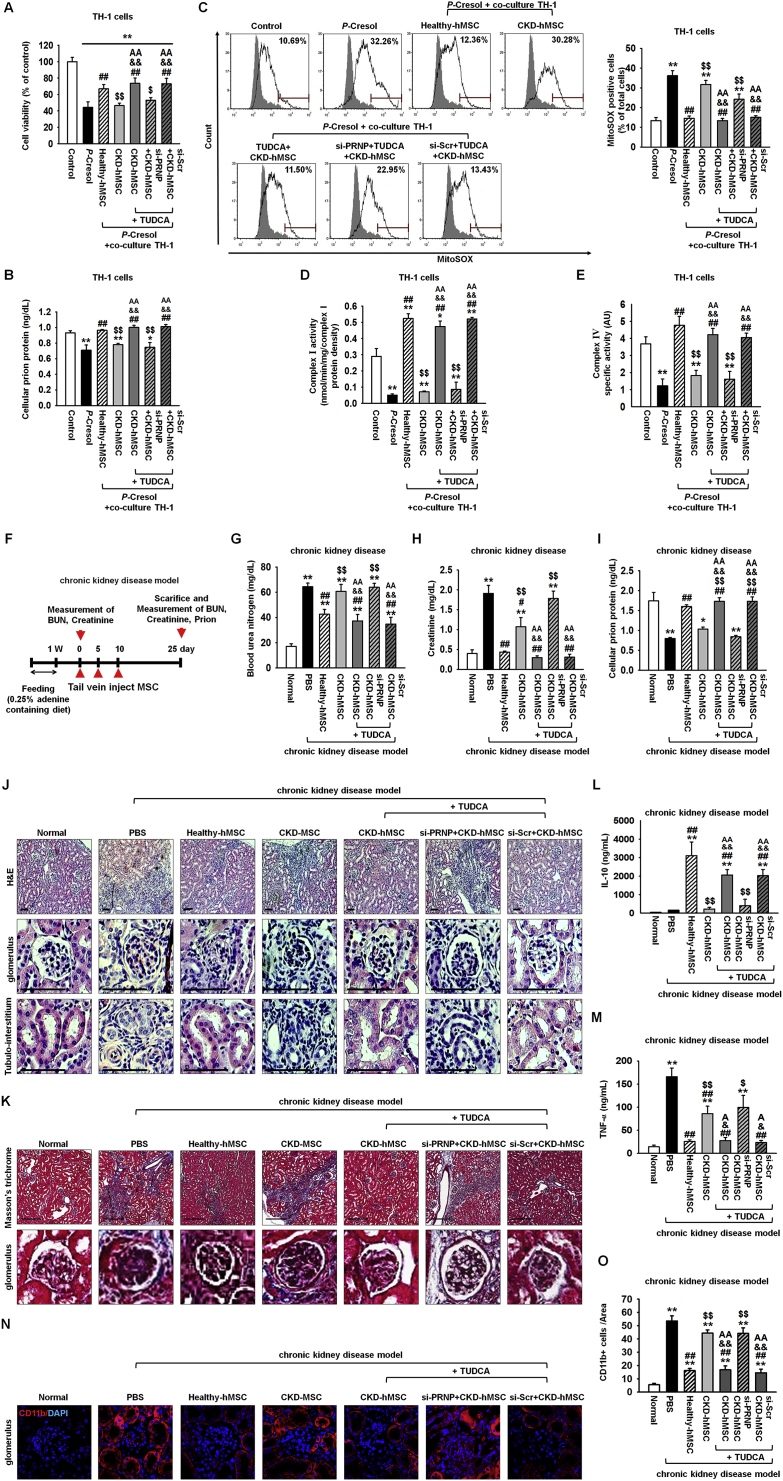

3.4. Increased serum PrPC levels by TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs enhance recovery from kidney fibrosis through downregulation of inflammatory cytokines

First, to confirm the protective effect on TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs on the CKD condition, induced by P-cresol, after renal proximal tubule epithelial (TH-1) cells were exposed to P-cresol for 24 h during co-culture, and then, we carried out co-culture of TH-1 cells with the upper chamber containing one of the following groups: Healthy-hMSCs, CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs (TUDCA+CKD-hMSC), TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP (si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC), and TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-Scr (si-Scr+CKD-hMSC) for 48 h. TH-1 cells showed reduced viability and decreased expression of PrPC during exposure to P-cresol (Fig. 5A and B). Co-culture of TH-1 with the TUDCA+CKD-hMSC group increased cell viability to a level similar to that of the healthy-hMSC group (Fig. 5A). The TUDCA+CKD-hMSC group also showed increased expression of PrPC in TH-1 cells (Fig. 5B). These results showed that TH-1 viability may be increased by PrPC and by the protective effect of TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs. To confirm that the TUDCA+CKD-hMSC group had greater mitochondrial activity, MitoSOX analysis and ELISA were carried out and revealed reduced mitochondrial O2•− concentration and enhanced complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activities (Fig. 5C–E). In contrast, co-culture of TH-1 cells with si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC decreased cell viability and mitochondrial activity. These results pointed to the key mechanism of the protective effect of TUDCA against CKD: an increase in mitochondrial activity through upregulation of PrPC. These data indicate that TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs protect TH-1 cells against the CKD condition by increasing PrPC expression, suggesting that PrPC plays a key role in the mechanism underlying TUDCA-enhanced mitochondrial activity.

Fig. 5.

Transplantation of TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs protects against kidney fibrosis via upregulation of PrPCin the mouse model of adenine-induced CKD. (A) Treatment TH-1 cells with or without P-cresol cultured alone for 24 h, or co-cultured with Healthy-hMSCs, CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs (TUDCA+CKD-hMSC), TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP (si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC), or TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-Scr (si-Scr+CKD-hMSC) using culture inserts for 48 h, after analysis of the proliferation of TH-1 cells (n = 3 sample/group). Values represent the mean ± SEM. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. control, ##p < 0.01 vs. P-cresol group, $p < 0.05, and $$p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC group, && p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC group, AA p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC group. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (B) Treatment of TH-1 cells with or without P-cresol cultured alone or with Healthy-hMSC group, CKD-hMSC group, TUDCA+CKD-hMSC group, si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC group, or si-Scr+CKD-hMSC group using culture inserts; we measured PrPC expression only in lysates of TH-1 by ELISA. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. control, ##p < 0.01 vs. P-cresol group, $p < 0.05, and $$p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC group, && p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC group, AA p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC group. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (C) The positive signals of MitoSOX were counted by FACS analysis with staining after treatment of TH-1 cells with or without P-cresol cultured alone, or with Healthy-hMSC group, CKD-hMSC group, TUDCA+CKD-hMSC group, si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC group, or si-Scr+CKD-hMSC group. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. control, ##p < 0.01 vs. P-cresol group, $p < 0.05, and $$p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC group, && p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC group, AA p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC group. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (D, E) Complex Ⅰ and complex Ⅳ activities were analyzed after treatment of TH-1 cells with or without P-cresol cultured alone, or with Healthy-hMSC group, CKD-hMSC group, TUDCA+CKD-hMSC group, si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC group, or si-Scr+CKD-hMSC group. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. control, ##p < 0.01 vs. P-cresol group, $p < 0.05, and $$p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC group, && p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC group, AA p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC group. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (F) The scheme of the mouse model of CKD. The CKD model mice were fed 0.25% adenine for 1 week, and then we euthanized some mice in each group for validating the CKD model by measurement of BUN and creatinine. Each CKD mouse was injected with PBS or with Healthy-hMSCs, CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs (TUDCA+CKD-hMSC), TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP (si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC), or TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-Scr (si-Scr+CKD-hMSC) at 0, 5, and 10 days via a tail vein (n = 10 mice/group). After 25 days, measurement of BUN, creatinine, or PrPC was carried out. (G–I) At 25 days after discontinued feeding of adenine, we measured BUN, creatinine, and PrPC in each mouse group in their serum samples (100 μL). Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. Normal, #p < 0.05, and ##p < 0.01 vs. PBS, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC group, & p < 0.05 and && p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC group, A p < 0.05 and AA p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC group. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (J and K) Regeneration of kidney tissue in CKD was confirmed by H&E staining (J) or Masson's trichrome (K). Scale bar = 100 μm, 400 μm. (L, M) The level of IL-10 or TNF-α in each serum sample was analyzed by ELISA. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. Normal, #p < 0.05, and ##p < 0.01 vs. PBS, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC group, & p < 0.05 and && p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC group, A p < 0.05 and AA p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC group. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (N) After feeding adenine, macrophage marker (CD11b; red) was analyzed by immunohistochemistry. (O) Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.01 vs. Normal, #p < 0.05, and ##p < 0.01 vs. PBS, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC group, & p < 0.05 and && p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC group, A p < 0.05 and AA p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC group. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test).

To further confirm the protective effect of TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs in CKD mice, we established the CKD model in mice by feeding them with 0.25% adenine for 1 week, and then injected each group, healthy-hMSCs, CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs (TUDCA+CKD-hMSC), TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP (si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC), and si-Scr-pretreated TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs (si-Scr+CKD-hMSC) by intravenous (IV) tail injection on days 0, 5, and 10. At 25 days after discontinuation of adenine feeding, group TUDCA+CKD-hMSC had similar levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine compared with donor healthy-hMSCs (Fig. 5F–H). TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs also increased serum PrPC, which indicated increased repair of CKD damage to kidney cells through enhanced mitochondrial activity (Fig. 5I). Confirming aggravation of kidney fibrosis, a decrease of fibrosis on glomeruli and an increase of tubulo-interstitium were observed in mouse group TUDCA+CKD-hMSC according to H&E, and Masson's trichrome staining (Fig. 5J and K). Kidney fibrosis could be aggravated by deficient IL-10, and by upregulation of TNF-α, a macrophage-secreted inflammation factor [27]. We confirmed by ELISA that injection of TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs into mice upregulated IL-10 and downregulation TNF-α in the serum of the mouse model of CKD (Fig. 5L, M). We also measured the macrophage marker CD11b at day 25 after feeding adenine by immunohistochemistry. The fluorescence of macrophage marker CD11b decreased at glomerulus in the TUDCA+CKD-hMSC group (Fig. 5N, O). In contrast, injection of si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC showed the opposite results, increasing BUN and creatinine levels (Fig. 5G and H). These results indicate that the protective effect of TUDCA was attenuated by decreased serum PrPC concentration (Fig. 5I). Injection of si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC, as expected, increased macrophage number, downregulated IL-10, and upregulated TNF-α, which curtailed the increased kidney fibrosis and necrosis of kidney tissue (Fig. 5J–O). There was a notable consequence: an increase in serum PrPC by treatment with TUDCA enhanced CKD-hMSC stem cell therapy in the mouse model of CKD.

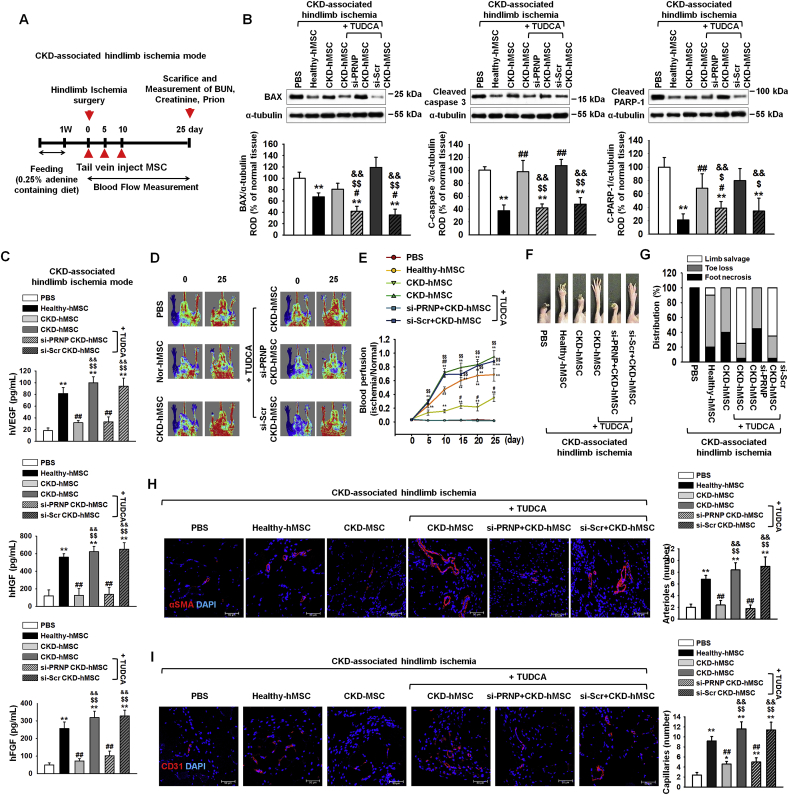

3.5. Increased serum PrPC concentration by TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs enhanced recovery from CKD-associated VD

After feeding of 0.25% adenine to mice for 1 week, we set up CKD-associated VD in mice by hindlimb ischemia surgery (Fig. 6A). At postoperative day 3, injection with TUDCA+CKD-hMSC intravenously decreased levels of apoptosis-associated proteins—BAX, cleaved caspase 3, and cleaved PARP-1—and increased expression of neovascularization cytokines: hVEGF, hHGF, and hFGF (Fig. 6A–C). These results indicate that TUDCA effectively treated CKD-associated VD through decreasing tissue apoptosis and upregulating neovascularization cytokines. At postoperative day 25, the blood perfusion ratio was analyzed by laser Doppler perfusion imaging and was found to be increased in the TUDCA+CKD-hMSC group to levels similar to those in the healthy-hMSC group (Fig. 6D and E). Moreover, the TUDCA+CKD-hMSC group showed a reduction in limb loss and foot necrosis (Fig. 6F and G). To investigate neovascularization, we performed immunofluorescence staining for CD31 or α-SMA on postoperative day 25. Capillary density and arteriole density increased in the TUDCA+CKD-hMSC group (Fig. 6H and I). By contrast, group si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC showed reduced neovascularization, according to measurement of neovascularization cytokines on postoperative day 3, and capillaries and arterioles had lower levels of CD31 and/or α-SMA on day 25, and increased necrosis of the foot, after we detected increased expression of apoptosis-associated proteins and decreased blood perfusion. These data indicate that TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs promoted neovascularization and functional recovery in kidney fibrosis-and-ischemia–injured tissue, and that regulation of mitochondrial PrPC levels by TUDCA is important for the functionality of transplanted CKD-hMSCs in this tissue. These data indicate that TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSC enhanced neovascularization in the mouse model of CKD-associated VD through increased levels of PrPC.

Fig. 6.

TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs enhanced neovascularization in the mouse model of CKD-associated hindlimb ischemia through upregulation of mitochondrial PrPC. (A) The scheme of the mouse model of CKD-associated hindlimb ischemia. CKD-associated hindlimb ischemia mouse model was fed with 0.25% adenine for 1 week, and then we administered hindlimb ischemia in each mouse group surgically. Each CKD-associated hindlimb ischemia mouse model was injected with PBS or Healthy-hMSCs, CKD-hMSCs, TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs (TUDCA+CKD-hMSC), TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-PRNP (si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC), or TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs pretreated with si-Scr (si-Scr+CKD-hMSC) at 0, 5, and 10 days via a tail vein (n = 10 mice/group). To measure tissue apoptosis and neovascularization at postoperative day 3, we euthanized some mice in each group. (B) At postoperative day 3, western blot analysis quantified the cell apoptosis associated protein in each their hindlimb ischemia tissue. The expression levels were determined by densitometry relative of α-tubulin. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. PBS, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC, $p < 0.05, and $$p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC, && p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (C) Expression of hVEGF, hHGF, and hFGF in each their hindlimb ischemia tissue lysis group was analyzed by ELISA. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. PBS, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC, $p < 0.05, and $$p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC, && p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (D) The CKD associated hindlimb ischemia mouse model improved in blood perfusion by laser Doppler perfusion imaging analysis of the ischemic-injured tissues of PBS, Healthy-hMSC, CKD-hMSC, TUDCA+CKD-hMSC, si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC, and si-Scr+CKD-hMSC at 0 day, and 25 days postoperation. (E) The ratio of blood perfusion (blood flow in the left ischemic limb/blood flow in the right non-ischemic limb) was measured in each mouse of the five groups. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. PBS, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC, $p < 0.05, and $$p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC, && p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test). (F) Representative image illustrating the different outcomes (foot necrosis, toe loss, and limb salvage) of CKD-associated ischemic limbs injected with five treatments at postoperative 25 days. (G) Distribution of the outcomes in each group at postoperative day 25. (H, I) At postoperative 25 days, capillary density (αSMA; Red), and arteriole density (CD31; Red) were analyzed by immunofluorescence staining, respectively. Scale bar = 50 μm, 100 μm. Capillary density was quantified as the number of human αSMA or CD31 positive cells. Values represent the mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. PBS, #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01 vs. Healthy-hMSC, $p < 0.05, and $$p < 0.01 vs. CKD-hMSC, && p < 0.01 vs. si-PRNP+CKD-hMSC. (One-way ANOVA, using Tukey's post-hoc test).

4. Discussion

In our study, we reported that transplantation of TUDCA-treated patient-derived autologous MSCs reverses kidney fibrosis and increases neovascularization in a CKD VD model. In addition, we demonstrate that cellular PrPC is a key molecule involved: we showed that a decreased level of PrPC in the serum of the patients with CKD VD leads to reduced functionality of autologous MSCs derived from the patients with CKD. We have shown that TUDCA rescues MSCs derived from patients with CKD by increasing the amount of PrPC in CKD-hMSCs, thus increasing the binding of PrPC to PINK1 within mitochondria, restoring mitochondrial activity in MSCs and inducing complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activation. In addition, we showed in vivo that the transplantation of TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs enhances therapeutic effects of MSC transplantation targeting CKD and associated conditions such as VD by increasing the PrPC level. Our results suggest that therapeutic transplantation of CKD-hMSCs treated with TUDCA could lead to further studies as a potent therapy for patients who have both CKD and VD.

Cardiovascular disease (CD) such as peripheral ischemic disease is a common problem among patients with CKD, caused by hyperhomocysteinemia, oxidant stress, dyslipidemia, and elevated inflammatory markers after initiation of CKD [5,28]. We show that a CKD biomarker, eGFR, is lower in patients' serum at stages 3b–5 (average eGFR: 22.4), indicating that levels of BUN and creatinine circulate in blood serum. In addition, we discovered that levels of PrPC are decreased in the serum of the patients with CKD-associated VD. One study has shown have shown that CKD in patients is accompanied by several mitochondrial aberrations such as high levels of ROS, inflammation, and a cytokine imbalance [6]. These results suggest that CKD-hMSCs possess decreased amounts of mitochondrial PrPC (which binds to PINK1); this aberration causes mitochondrial dysfunction and damages cellular metabolism of CKD-hMSCs, potentially deprecating their therapeutic utility.

PrPC is known to perform an integral function in bone marrow reconstitution, tissue regeneration, self-renewal, and recapitulation in stem cells [29,30]. PrPC has been known to induce an abundant environment for stem cells to thrive, by providing niche-like conditions for stem cells to get activated and to proliferate [29,31,32]. In addition, our team has reported that the increased level of PrPC inhibits oxidative stress, reducing cellular apoptosis through enhancement of SOD and catalase activity thereby increasing the therapeutic effectiveness in a hindlimb ischemia model [13]. Similarly, our results suggested that TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs produce more PrPC, and that PrPC binds to mitochondrial protein PINK1 as an integral pathway in TUDCA-initiated protection of CKD-hMSCs. Previous study proved PINK1 binds with TOM complex, thereby regulates of parkin affects the mitochondria potential, and another study concluded mitochondrial PrPC may be transported to TOM70 [33,34]. Taken together, we suggest that binging PrPC with PINK1 might increase mitochondrial potential.

PINK1 is well known recruit parkin to depolarized mitochondria, then to increase activation of parkin E3 ligase activity, resulting in ubiquitination of multiple substrates at the outer mitochondrial membrane. It takes a role in critical upstream step mitophagy, destruction of damage mitochondria [33,35]. PINK1 also regulated mitochondrial respiration driven by electron transport chain (ETC) complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activity [36]. Recent studies revealed that downregulation of PINK1 disrupts the regulation of mitochondrial mitophagy in CKD, and mitochondria in the CKD model undergo impairment of mitochondrial fission thereby enlarged, dysfunctional mitochondria are formed [37,38]. Impairment of mitochondrial fission causes cellular damage by decreasing the ability of mitochondria to remove damaged components; this observation suggests that PINK1-mediated mitochondrial fission is critical for healthy renal function [37,39]. In our study, we demonstrate that the TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs have greater mitofission according to western blot analysis of mitofission-inhibitory protein p-DPR1 (phosphorylation of Ser637) and mitofusion proteins MFN1 and OPA1 as well as increased stabilization of mitochondrial membrane potential and a decrease in the number of abnormal mitochondria. More specifically, we indicate that PrPC binding to PINK1 is crucial for retaining stability of the inner mitochondrial membrane and for enhancing the mitochondrial membrane potential according to TEM imaging. These results suggest that the mitochondrial dysfunction in CKD-hMSCs is exacerbated due to decreased stability of PINK1 bound to PrPC, and that TUDCA counters these limitations by protecting CKD-hMSCs via upregulation of PrPC, thereby repairing downstream mitochondrial membrane potential and cellular proliferation.

We aimed to verify in CKD-hMSCs that TUDCA enhanced mitochondrial membrane potential and increased the amount of PrPC, which has protective effects, thus possibly recovering other damaged kidney cells through TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs using human TH-1 cells. We developed a CKD conditional model where TH-1 cells are exposed to P-cresol for 24 h, and then seeded in the upper chamber for co-culture with respective MSC groups for 48 h. The TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs group, as expected, increased TH-1 cell viability by increasing PrPC. These data support our theory, that effective upregulation of PrPC could lead to regulate mitochondrial membrane potential and that despite the use of damaged cells, stem cell therapy can be enhanced by treatment with TUDCA. In contrast, co-culture of TH-1 cells with si-PRNP+CKD-hMSCs group decreased viability of TH-1 cells, because the impossible uptake of PrPC blocked the protective effect of TUDCA, resulting in increased mitochondrial O2•− levels and decreased complex Ⅰ & Ⅳ activity. These findings indicate that TUDCA increases cell proliferation through enhancement of mitochondrial membrane potential and restores CKD-damaged kidney tubular cells via an increased level of PrPC.

Finally, we showed in vivo that TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs are a potent tool for tackling CKD and for combating its associated kidney fibrosis and neovascularization in a mouse model of CKD-associated hindlimb ischemia. We directly examined the restored kidneys of the mice, resulting that CKD fibrosis, necrosis, and glomerulus swelling was decreased and tubule interstitium was increased in the TUDCA+CKD-hMSC-injected group. Other studies have shown that increased inflammatory factors are crucial for determining the development of renal dysfunction and fibrosis [27,40]. In our mouse model of CKD-associated hindlimb ischemia, injected TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs caused significant changes in the inflammatory cytokines such as increased levels of IL-10 and decreased levels of TNF-α, which suggest that inflammation was lowered. In addition, we aimed to evaluate similar therapeutic effects at the ischemic injury site of the mice. We observed that injected TUDCA+CKD-hMSCs in a mouse group saved vascular functions via downregulation of apoptosis-related proteins and upregulation of neovascularization proteins on postoperative day 3, with the increased blood perfusion ratio, limb salvage, and vessel formation, such as development of arteries and capillary vessels on postoperative day 25 in a PrPC-dependent pathway. Injection of si-PRNP+CKD-hMSCs increased kidney fibrosis and thereby induced a decrease of IL-10 and increase of TNF-α levels and attenuated the functional recovery and neovascularization in the mouse model of CKD-associated hindlimb ischemia by blocking expression of PrPC.

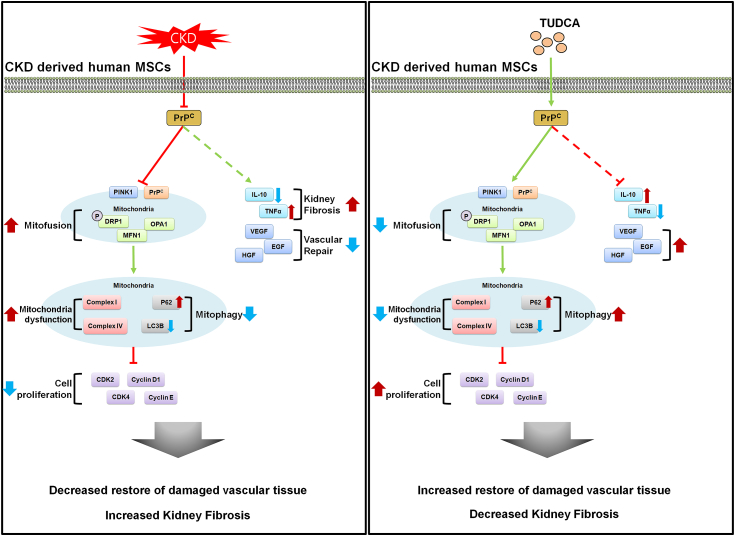

In our study, we demonstrated a novel finding that CKD patient–derived MSCs manifest reduced functionality because of the decreased level of PrPC in serum. In addition, we propose that TUDCA effectively potentiates autologous CKD-hMSCs to exert therapeutic effects by targeting CKD-associated hindlimb ischemia in the mouse model and a fibrotic cell population, thus overcoming the obstacles of compromised stem cell function of CKD-hMSCs. We also demonstrated the mechanistic pathway via which TUDCA enhanced mitochondrial activity: by enhancing the expression of PrPC thereby promoting the binding of PrPC to PINK1 in the stem cells and increasing the supply of blood serum PrPC (Fig. 7). These results suggest that TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs could offer a novel approach to targeting CKD-associated hindlimb ischemia via the use of a safe, feasible autologous cell source via intravenous injection of protected MSCs into the patients via precise regulation of PrPC.

Fig. 7.

The scheme of autologous therapy with TUDCA-treated CKD-hMSCs: hMSC enhancement via increased concentration of PrPC. Reduction of mitochondrial functionality leads to decreased cellular proliferation and function, including decreased repair of damaged vascular tissue, ultimately unable to restore of kidney fibrosis. Increased in mitochondrial functionality leads to increased cellular proliferation, which enhances vascular repair of damaged cells. Healthier cellular state leads to increased autologous therapy of kidney fibrosis.

Author contributions

Y.M.Y. contributed to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. S.M.K, Y.S.H, C.W.Y, and J.H.L provided interpretation of data, statistical analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. H.J.N. developed the study concept and drafting of the manuscript. S.H.L. developed the study concept and design, and performed acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, procurement of funding, and study supervision.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund, a National Research Foundation grant funded by the Korean government (NRF-2017M3A9B4032528). The biospecimens for this study were provided by the Seoul National University Hospital Human Biobank, a member of the Korea Biobank Network, which is supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare. All samples derived from the National Biobank of Korea were obtained with informed consent under institutional review board-approved protocols. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection or analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2019.101144.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Castro A.F., Coresh J. CKD surveillance using laboratory data from the population-based National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009;53:S46–S55. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Hooge R., Van de Vijver G., Van Bogaert P.P., Marescau B., Vanholder R., De Deyn P.P. Involvement of voltage- and ligand-gated Ca2+ channels in the neuroexcitatory and synergistic effects of putative uremic neurotoxins. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1764–1775. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meijers B.K., Claes K., Bammens B., de Loor H., Viaene L., Verbeke K., Kuypers D., Vanrenterghem Y., Evenepoel P. p-Cresol and cardiovascular risk in mild-to-moderate kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;5:1182–1189. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07971109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabriele S., Sacco R., Altieri L., Neri C., Urbani A., Bravaccio C., Riccio M.P., Iovene M.R., Bombace F., De Magistris L., Persico A.M. Slow intestinal transit contributes to elevate urinary p-cresol level in Italian autistic children. Autism Res. 2016;9:752–759. doi: 10.1002/aur.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarnak M.J., Levey A.S., Schoolwerth A.C., Coresh J., Culleton B., Hamm L.L., McCullough P.A., Kasiske B.L., Kelepouris E., Klag M.J., Parfrey P., Pfeffer M., Raij L., Spinosa D.J., Wilson P.W. American heart association councils on kidney in cardiovascular disease HBPRCC, epidemiology, prevention, kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American heart association councils on kidney in cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure research, clinical cardiology, and epidemiology and prevention. Circulation. 2003;108:2154–2169. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095676.90936.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlieper G., Schurgers L., Brandenburg V., Reutelingsperger C., Floege J. Vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease: an update. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016;31:31–39. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velenosi T.J., Urquhart B.L. Pharmacokinetic considerations in chronic kidney disease and patients requiring dialysis. Expert Opin. Drug Metabol. Toxicol. 2014;10:1131–1143. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2014.931371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uccelli A., Moretta L., Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:726–736. doi: 10.1038/nri2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little M.H. Regrow or repair: potential regenerative therapies for the kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17:2390–2401. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J.H., Ryu J.M., Han Y.S., Zia M.F., Kwon H.Y., Noh H., Han H.J., Lee S.H. Fucoidan improves bioactivity and vasculogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in murine hind limb ischemia associated with chronic kidney disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016;97:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang X., Ding Y., Zhang Y., Tse H.F., Lian Q. Paracrine mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy: current status and perspectives. Cell Transplant. 2014;23:1045–1059. doi: 10.3727/096368913X667709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klinkhammer B.M., Kramann R., Mallau M., Makowska A., van Roeyen C.R., Rong S., Buecher E.B., Boor P., Kovacova K., Zok S., Denecke B., Stuettgen E., Otten S., Floege J., Kunter U. Mesenchymal stem cells from rats with chronic kidney disease exhibit premature senescence and loss of regenerative potential. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon Y.M., Lee J.H., Yun S.P., Han Y.S., Yun C.W., Lee H.J., Noh H., Lee S.J., Han H.J., Lee S.H. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid reduces ER stress by regulating of Akt-dependent cellular prion protein. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:39838. doi: 10.1038/srep39838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prusiner S.B., Scott M.R., DeArmond S.J., Cohen F.E. Prion protein biology. Cell. 1998;93:337–348. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prusiner S.B. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hornshaw M.P., McDermott J.R., Candy J.M., Lakey J.H. Copper binding to the N-terminal tandem repeat region of mammalian and avian prion protein: structural studies using synthetic peptides. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;214:993–999. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Besnier L.S., Cardot P., Da Rocha B., Simon A., Loew D., Klein C., Riveau B., Lacasa M., Clair C., Rousset M., Thenet S. The cellular prion protein PrPc is a partner of the Wnt pathway in intestinal epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2015;26:3313–3328. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinheiro L.P., Linden R., Mariante R.M. Activation and function of murine primary microglia in the absence of the prion protein. J. Neuroimmunol. 2015;286:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lobao-Soares B., Bianchin M.M., Linhares M.N., Carqueja C.L., Tasca C.I., Souza M., Marques W., Jr., Brentani R., Martins V.R., Sakamoto A.C., Carlotti C.G., Jr., Walz R. Normal brain mitochondrial respiration in adult mice lacking cellular prion protein. Neurosci. Lett. 2005;375:203–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miele G., Jeffrey M., Turnbull D., Manson J., Clinton M. Ablation of cellular prion protein expression affects mitochondrial numbers and morphology. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;291:372–377. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soares R., Ribeiro F.F., Xapelli S., Genebra T., Ribeiro M.F., Sebastiao A.M., Rodrigues C.M.P., Sola S. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid enhances mitochondrial biogenesis, neural stem cell pool, and early neurogenesis in adult rats. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018;55:3725–3738. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0592-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sola S., Brito M.A., Brites D., Moura J.J., Rodrigues C.M. Membrane structural changes support the involvement of mitochondria in the bile salt-induced apoptosis of rat hepatocytes. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2002;103:475–485. doi: 10.1042/cs1030475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin W., Zhang Q., Liu L., Yin S., Liu Z., Cao W. Klotho restoration via acetylation of Peroxisome Proliferation-Activated Receptor gamma reduces the progression of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017;92:669–679. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown D.R., Nicholas R.S., Canevari L. Lack of prion protein expression results in a neuronal phenotype sensitive to stress. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;67:211–224. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stella R., Cifani P., Peggion C., Hansson K., Lazzari C., Bendz M., Levander F., Sorgato M.C., Bertoli A., James P. Relative quantification of membrane proteins in wild-type and prion protein (PrP)-knockout cerebellar granule neurons. J. Proteome Res. 2012;11:523–536. doi: 10.1021/pr200759m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narendra D.P., Youle R.J. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction: role for PINK1 and Parkin in mitochondrial quality control. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2011;14:1929–1938. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sziksz E., Pap D., Lippai R., Beres N.J., Fekete A., Szabo A.J., Vannay A. Fibrosis related inflammatory mediators: role of the IL-10 cytokine family. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/764641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarnak M.J., Levey A.S., Schoolwerth A.C., Coresh J., Culleton B., Hamm L.L., McCullough P.A., Kasiske B.L., Kelepouris E., Klag M.J., Parfrey P., Pfeffer M., Raij L., Spinosa D.J., Wilson P.W. American heart association councils on kidney in cardiovascular disease HBPRCC, epidemiology, prevention, kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American heart association councils on kidney in cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure research, clinical cardiology, and epidemiology and prevention. Hypertension. 2003;42:1050–1065. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000102971.85504.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang C.C., Steele A.D., Lindquist S., Lodish H.F. Prion protein is expressed on long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells and is important for their self-renewal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:2184–2189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510577103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka E.M., Reddien P.W. The cellular basis for animal regeneration. Dev. Cell. 2011;21:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin-Lanneree S., Halliez S., Hirsch T.Z., Hernandez-Rapp J., Passet B., Tomkiewicz C., Villa-Diaz A., Torres J.M., Launay J.M., Beringue V., Vilotte J.L., Mouillet-Richard S. The cellular prion protein controls notch signaling in neural stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cell. 2017;35:754–765. doi: 10.1002/stem.2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haddon D.J., Hughes M.R., Antignano F., Westaway D., Cashman N.R., McNagny K.M. Prion protein expression and release by mast cells after activation. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;200:827–831. doi: 10.1086/605022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lazarou M., Jin S.M., Kane L.A., Youle R.J. Role of PINK1 binding to the TOM complex and alternate intracellular membranes in recruitment and activation of the E3 ligase parkin. Dev. Cell. 2012;22:320–333. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faris R., Moore R.A., Ward A., Race B., Dorward D.W., Hollister J.R., Fischer E.R., Priola S.A. Cellular prion protein is present in mitochondria of healthy mice. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:41556. doi: 10.1038/srep41556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gladkova C., Maslen S.L., Skehel J.M., Komander D. Mechanism of parkin activation by PINK1. Nature. 2018;559:410–414. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0224-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu W., Acin-Perez R., Geghman K.D., Manfredi G., Lu B., Li C. Pink1 regulates the oxidative phosphorylation machinery via mitochondrial fission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:12920–12924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107332108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forbes J.M., Thorburn D.R. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018;14:291–312. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2018.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li W., Du M., Wang Q., Ma X., Wu L., Guo F., Ji H., Huang F., Qin G. FoxO1 promotes mitophagy in the podocytes of diabetic male mice via the PINK1/parkin pathway. Endocrinology. 2017;158:2155–2167. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhan M., Brooks C., Liu F., Sun L., Dong Z. Mitochondrial dynamics: regulatory mechanisms and emerging role in renal pathophysiology. Kidney Int. 2013;83:568–581. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodell C.B., Rai R., Faubel S., Burdick J.A., Soranno D.E. Local immunotherapy via delivery of interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor beta antagonist for treatment of chronic kidney disease. J. Contr. Release. 2015;206:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.