Abstract

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory gastrointestinal disorder. Genetic association studies have implicated dysregulated autophagy in CD. Among risk loci identified are a promoter single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)(rs13361189) and two intragenic SNPs (rs9637876, rs10065172) in immunity-related GTPase family M (IRGM) a gene that encodes a protein of the autophagy initiation complex. All three SNPs have been proposed to modify IRGM expression, but reports have been divergent and largely derived from cell lines. Here, analyzing RNA-Sequencing data of human tissues from the Genotype-Tissue Expression Project, we found that rs13361189 minor allele carriers had reduced IRGM expression in whole blood and terminal ileum, and upregulation in ileum of ZNF300P1, a locus adjacent to IRGM on chromosome 5q33.1 that encodes a long noncoding RNA. Whole blood and ileum from minor allele carriers had altered expression of multiple additional genes that have previously been linked to colitis and/or autophagy. Notable among these was an increase in ileum of LTF (lactoferrin), an established fecal inflammatory biomarker of CD, and in whole blood of TNF, a key cytokine in CD pathogenesis. Last, we confirmed that risk alleles at all three loci associated with increased risk for CD but not ulcerative colitis in a case-control study. Taken together, our findings suggest that genetically encoded IRGM deficiency may predispose to CD through dysregulation of inflammatory gene networks. Gene expression profiling of disease target tissues in genetically susceptible populations is a promising strategy for revealing new leads for the study of molecular pathogenesis and, potentially, for precision medicine.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Single nucleotide polymorphisms in immunity-related GTPase family M (IRGM), a gene that encodes an autophagy initiation protein, have been linked epidemiologically to increased risk for Crohn’s disease (CD). Here, we show for the first time that subjects with risk alleles at two such loci, rs13361189 and rs10065172, have reduced IRGM expression in whole blood and terminal ileum, as well as dysregulated expression of a wide array of additional genes that regulate inflammation and autophagy.

Keywords: autophagy, inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract that has been proposed to arise from defective mucosal homeostatic responses against infectious and toxic agents (17). CD has pathologic and clinical features that are distinct from those of ulcerative colitis (UC), another inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), suggesting that the two disorders have discrete pathogenesis (51). Although environmental factors such as infection, diet, and smoking have been shown to play a role in CD (1, 42, 53), familial (37) and twin (49, 50) studies indicate an important role for genetic determinants. Indeed, in the past several years, several candidate gene and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have together suggested that at least 231 independent single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within 200 loci associate with IBD risk (29).

Multiple studies have now linked SNPs in autophagy-related genes, including immunity-related GTPase family M (IRGM), ATG16L1, and NOD2, to CD risk (19, 38, 43), collectively suggesting that defective autophagy may be a key driver in CD pathogenesis (51). An evolutionarily conserved process by which cells clear invasive (i.e., pathogens) and endogenous (i.e., defective organelles) agents from the cytosol, autophagy serves an essential homeostatic role in epithelial and other cells, limiting host cell damage, suppressing inflammatory responses, and containing and degrading pathogens (6, 11). Deficient autophagic function has recently been suggested to underlie several cellular defects that contribute to CD, including deficits in clearance of intracellular bacteria, antigen presentation, and Paneth cell function (25).

The IRGM gene, located on chromosome 5q33.1, encodes a protein that is thought to play a central role in autophagy by stabilizing the activation and assembly of several CD-associated core autophagy proteins and coupling them to innate immunity receptors (7). IRGM rs13361189 (−4299T>C), a SNP in perfect linkage disequilibrium (LD) with a presumed causal 20-kb copy number variation deletion upstream of IRGM, has been shown to associate with increased risk for CD (33, 38). A synonymous IRGM exon 2 SNP rs10065172 (+313C>T) that is in high LD with rs13361189 has also been linked to CD in some (15, 39, 41) but not all (27) reports. A third SNP, rs9637876 (−261C>T), has also previously been identified as an IRGM cis-expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) (20) but has been investigated in relation to IBD in only one prior study (3), to our knowledge.

Here, extending from prior studies that have largely identified these and other SNPs as associated with IBD at a population level, we analyzed publicly available RNA-Sequencing (Seq) data from human blood and ileum and identified genes that display altered expression in subjects with risk alleles at these loci. In addition to confirming reduced IRGM expression in blood and ileum, we found ileum-specific upregulation in risk allele carriers of a long intergenic noncoding RNA (lincRNA) encoded by ZNF300P1, a locus neighboring IRGM, as well as altered tissue-specific expression of TNF and a range of additional genes previously implicated in colitis and/or autophagy. Last, we tested the association of the IRGM SNPs with self-reported physician-diagnosed IBD in the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Environmental Polymorphisms Registry (EPR), a North Carolina-based repository of DNA and linked health questionnaire data (8, 9), confirming these SNPs to be associated with CD but not UC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

IRGM tissue expression analysis.

RNA-Seq data in the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) portal [https://gtexportal.org/home/; accessed on 9/21/17 (ileum) and 10/4/17 (whole blood)] were analyzed in relation to IRGM genotype at rs13361189, rs10065172, and rs9637876. The racial background of tissues in GTEx is 83.4% White, 13.7% African American, 1.0% Asian, and 1.0% not reported. Tissues in GTEx were generally not screened for nonmalignant conditions. Genotypes at SNPs of interest were taken from the GTEx VCF files for the whole exome sequencing and whole genome sequencing data sets and filtered to accept only variant calls with a genotype quality score of at least 30. RNA-seq data were mapped against the hg19 reference genome (excluding haplotype chromosomes) via STAR v2.5 (13) with the following parameters: –outMultimapperOrder Random–outSAMattrIHstart 0–outFilterType BySJout–alignSJoverhangMin 8. Mapped reads per gene were calculated by Subread featureCounts v. 1.5.0-p1 (28) with parameters “-s0 -Sfr -p.” To normalize gene expression quantification, transcripts per million (TPM) values were calculated per gene per sample. The annotations for this analysis are hg19 RefSeq gene models downloaded from the University of Californa, Santa Cruz Table Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) on September 22, 2017. Gene expression P values between genotypes were calculated in R with the wilcox.test function. Within each tissue of interest, differentially expressed genes were identified by DESeq2 v1.14.1 (30) with false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of 0.05 and no minimum fold change requirement. This differential analysis compared samples homozygous for the major allele at rs13361189 (T/T) to samples either heterozygous or homozygous for the minor allele (T/C or C/C), using racial background as a covariate in the design matrix. Samples for which the allele status at rs13361189 was unavailable were excluded from this analysis.

Study population.

Subjects were recruited from the NIEHS EPR, which is a repository of DNA and associated demographic data from a cohort of >18,000 human subjects (~2/3 non-Hispanic White, ~1/4 non-Hispanic Black, remainder Asian, Hispanic, and Other) in North Carolina (8, 9). The study was approved by the NIEHS Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave informed consent. Of 8,400 EPR participants with available DNA and health questionnaire data, we genotyped all subjects at rs13361189, rs10065172, and rs9637876 who answered “yes” to having a physician diagnosis of at least one of 11 autoimmune diseases (CD, UC, Sjogren’s syndrome, scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, pernicious anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, myositis, psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, and celiac disease; n = 1,055), plus an additional 3,109 patients who answered “no” to all 11 autoimmune diseases. Within this genotyped population of 4,164 subjects, we then conducted a case-control study, aiming to evaluate the association of the three IRGM SNPs with CD and UC. Given that there were very few cases of CD or UC among non-Hispanic Black, Asian, and Hispanic participants (data not shown), we restricted our analysis to non-Hispanic White subjects (n = 45 for CD; n = 94 for UC).

Clinical outcomes.

Subjects answered a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (https://cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes)-adapted health and exposures questionnaire. Personal history of physician-diagnosed CD and UC was assessed with an affirmative answer to the questions: Has a doctor or other healthcare provider ever told you that you have Crohn’s disease? and Has a doctor or other healthcare provider ever told you that you have ulcerative colitis? Controls for CD and UC were defined as subjects answering “no” to CD and UC, respectively.

Covariates.

Covariates in adjusted models included age, sex, tobacco use, and body mass index (BMI) and were obtained by questionnaire. BMI was measured as weight (pounds) divided by height in inches squared and converted to kilograms per meters squared. Tobacco use is taken from a “yes” or “no” response to the question, In your lifetime, have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes?

Genotyping.

DNA was extracted from blood using the Autopure LS system (Qiagen), and all three IRGM SNPs were genotyped using fluorescence-based allelic TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The following TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays were used for this study: rs10065172, Assay ID C__30593568_10; rs13361189, Assay ID C__31986315_10; and rs9637876, custom assay. Polymerase chain reactions were performed using 30 ng of genomic DNA isolated from whole blood in a 10-μl reaction volume using an Applied Biosystems ViiA-7 Real Time PCR machine. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was confirmed in control populations using the χ2-test. LD between SNPs was calculated using LDlink (https://analysistools.nci.nih.gov/LDlink).

Cell studies.

The IRGM locus was disrupted in HeLa cells using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, resulting in two clones with a ~230-bp deletion in the IRGM open reading frame, as previously described (18). HeLa cells were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2, in Dulbecco’s modified essential medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. The cells were stimulated for 4 h with 50 ng/ml TNF-α (no. 210-TA; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or for 4 and 24 h with 10 μg/ml Escherichia coli 0111:B4 LPS (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA). Human monocyte-derived macrophages were cultured as previously reported (31). TNF-α (Hs02786624_g1) and GAPDH (Hs00174128_m1) mRNA was quantified by RT-qPCR using Taqman gene expression assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific). IRGM protein expression was evaluated by immunoblotting, as previously described (23). In brief, cells were lysed, resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, probed overnight with anti-β-actin-peroxidase antibody (no. A3854; Sigma-Aldrich, 1:15,000) or anti-IRGM antibody (no. ab69494, Abcam, 1:1,000) followed by anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, and then detected on film after treatment with ECL reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Statistical analysis.

Differences in allele, genotype and haplotype frequencies between cases and controls in the EPR study were evaluated using the Pearson χ2-test. Using a recessive model (major plus heterozygous versus minor), we explored associations between genotype and self-reported CD and UC. Odds ratio (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by logistic regression. Covariates in adjusted models included age (at time of questionnaire completion), sex, tobacco use, and BMI. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. To address a possible effect of overrepresentation of autoimmune disease within our study population compared with the overall EPR population, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. In this analysis, participants with any of the 10 (non-CD) autoimmune diseases were weighted to simulate the autoimmune disease prevalence within the overall EPR population, and weighted logistic regression was conducted in models adjusted for age, BMI, sex, and smoking status. Regression analyses were performed using MedCalc for Windows, version 17.4 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium) and SAS, versions 9.3 and 9.4 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Relationship of IRGM SNPs to IRGM expression in human tissues.

IRGM rs13361189 (−4299T>C) and rs10065172 (+313C>T; synonymous) are in essentially perfect LD with each other (r2 = 1.0, LDLink) and also with a 20-kb deletion polymorphism upstream of IRGM that has been proposed to be the causal CD risk variant through impacting IRGM gene expression (33). Leveraging rs10065172 as an exonic tag SNP for the haplotype, it has been shown that mRNA expression of rs10065172 T, the minor (risk) allele, is far lower than that of the major allele (rs10065172 C) in some but not all cell lines surveyed (33). Contrary to this, a recent report has shown that IRGM expression in colonic tissue of CD patients with a rs10065172 C/T genotype is higher than that of rs10065172 C/C subjects (5). IRGM rs9637876 (−261C>T), which is in essentially perfect LD with rs13361189 and rs10065172 in European American subjects (r2 = 1.0) but not in African [Yoruba (YRI), r2 = 0.49] or African American (ASW; r2 = 0.62) subjects, has been little studied in relation to IRGM expression.

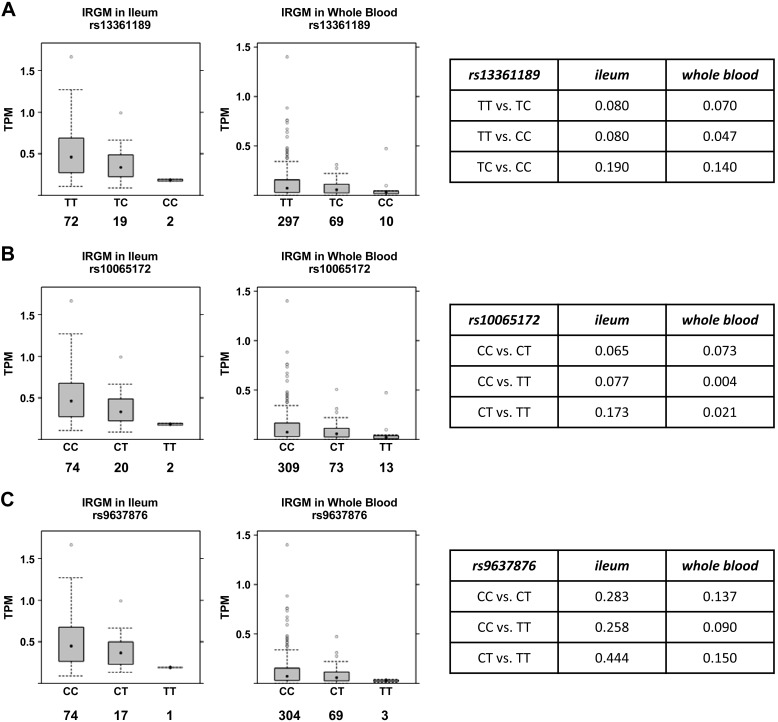

Given these divergent reports and the limited primary human data available, we evaluated the relationship of the three SNPs to IRGM expression in human tissue by analyzing raw RNA-Seq data in GTEx, a human tissue eQTL database (https://gtexportal.org/home/). In both whole blood and terminal ileum, the primary target tissue of CD, a monotonic decrease in IRGM mRNA was seen with increasing copy number of minor alleles at rs10065172 and rs13361189 (Fig. 1, A and B). This was statistically significant by linear regression for both loci in both tissues [rs13361189: ileum (β = −0.504, P = 0.021), whole blood (β = −0.269, P = 0.009); and rs10065172: ileum (β = −0.505, P = 0.017), whole blood (β = −0.312, P = 0.001)]. In pairwise comparison of genotypes, minor allele homozygosity at both loci was associated with significantly reduced IRGM expression in whole blood, whereas this fell marginally short of statistical significance in terminal ileum (Fig. 1, A and B). Subjects with minor allele(s) at rs9637876 had lower IRGM expression in ileum and whole blood, but this fell short of statistical significance by linear regression (data not shown) and by pairwise analysis (Fig. 1C). Results for all three SNP loci were indeterminate in the sigmoid colon, where IRGM expression was inadequate for analysis (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Relationship of immunity-related GTPase family M (IRGM) single nucleotide polymorphism to IRGM expression in human terminal ileum and whole blood. RNA-Seq data in the Genotype-Tissue Expression Project portal (https://gtexportal.org/home/) was analyzed to define the relationship of genotypes at rs13361189 (A), rs10065172 (B), and rs9637876 (C) to IRGM mRNA levels in human terminal ileum and whole blood. Box plots depict median and interquartile ranges of transcripts per million (TPM) for mRNA expression of IRGM defined by RefSeq gene models. Numbers below IRGM genotypes indicate the number of independent human specimens sampled. Tables at right depict P values for intergenotype comparisons.

Relationship of IRGM SNPs to expression of other genes in human tissues.

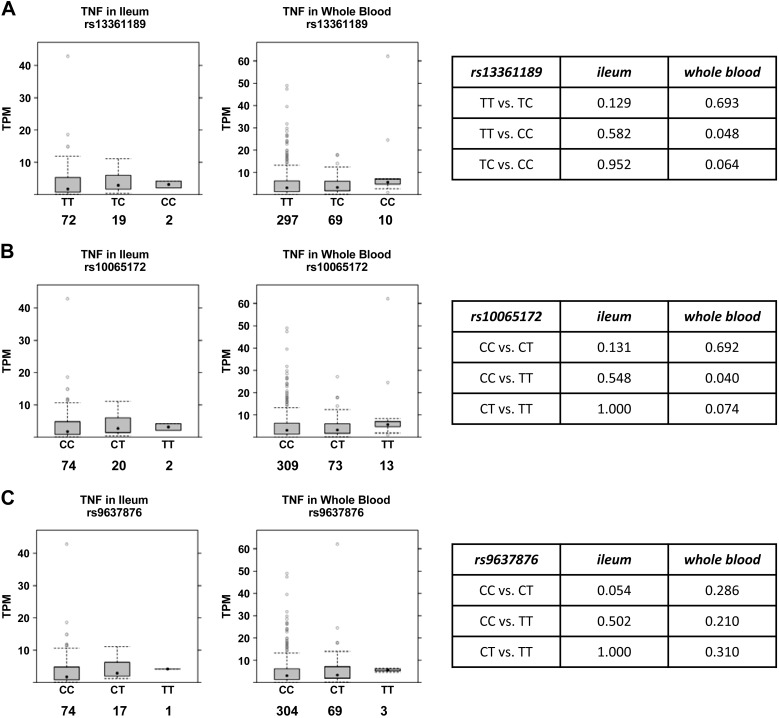

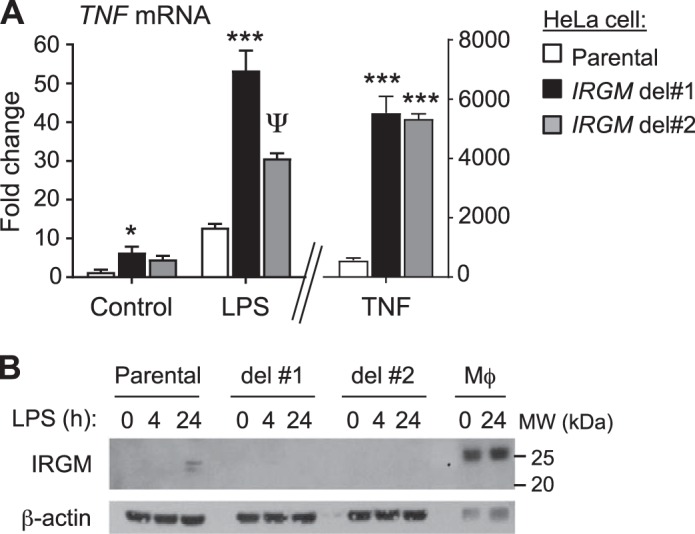

We speculated that expression of other genes that have been implicated in IBD pathogenesis might also be altered in subjects with IRGM risk alleles (i.e., thus representing trans-eQTLs). The proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α plays a central role in IBD pathogenesis and is clinically targeted in IBD treatment (10). Notably, we found that minor allele homozygosity at both rs13361189 and rs10065172 was associated with elevated expression of TNF in whole blood (Fig. 2). Generally consistent with this, two IRGM disruption HeLa cell clones made with CRISPR-Cas9 technology exhibited higher TNF expression than parental control cells in the naïve, lipopolysaccharide-stimulated, and TNF-stimulated state (Fig. 3A), suggesting that IRGM deficiency supports augmented TNF expression in human cells. Of note, LPS exposure, modeling the Gram-negative bacterial microbiota of the intestinal lumen, upregulated IRGM expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 2.

Relationship of immunity-related GTPase family M (IRGM) single nucleotide polymorphism TNF expression in human terminal ileum and whole blood. RNA-Seq data in the Genotype-Tissue Expression Project portal (gtexportal.org) was analyzed to define the relationship of genotypes at rs13361189 (A), rs10065172 (B), and rs9637876 (C) to TNF mRNA levels in human terminal ileum and whole blood. Box plots depict median and interquartile ranges of transcripts per million (TPM) for TNF mRNA expression. Numbers below IRGM genotypes indicate the number of independent human specimens sampled. Tables at right depict P values for intergenotype comparisons.

Fig. 3.

immunity-related GTPase family M (IRGM) disruption augments TNF expression by human cells. A: TNF mRNA was quantified by RT-qPCR in parental HeLa cells and two HeLa IRGM disruption CRISPR clones after exposure for 4 h to buffer (control), LPS, or TNF. Data are mean ± SE and are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P = 0.03; ψP = 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (comparison to parental cells under same treatment). B: HeLa cells and human monocyte-derived macrophages (Mϕ) were exposed to LPS as shown and then immunoblotted for IRGM and β-actin (loading control).

To evaluate trans-eQTL relationships for the IRGM rs13361189 risk allele in a more global and unbiased fashion that also accounted for multiple comparisons, we performed a transcriptome-wide analysis of differentially expressed genes in GTEx, comparing risk allele carriers to non-carriers. At a FDR of <0.05, three genes were significant in ileum (Table 1), and 29 genes were significant in whole blood (Table 2). These genes are discussed below. Neither IRGM nor TNF met genome-wide significance at FDR < 0.05 in this analysis.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes in ileum of rs13361189 risk allele carriers versus noncarriers

| Gene symbol | Gene Name | Mean TPM (Ref) | Mean TPM (Risk) | Risk Versus Ref FC | Risk Versus Ref P Value | Risk Versus Ref-Adjusted P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZNF300P1 | Zinc finger protein 300 pseudogene 1 | 4.15 | 9.22 | 1.74 | 1.11E−07 | 0.003 |

| LTF | Lactotransferrin | 5.03 | 11.51 | 1.64 | 3.82E−06 | 0.03 |

| MSH4 | mutS homolog 4 | 0.64 | 1.48 | 1.65 | 2.82E−06 | 0.03 |

Differentially expressed genes (false discovery rate < 0.05) in ileum between subjects homozygous major [reference (Ref)] at rs13361189 versus those with a risk allele (heterozygous + homozygous risk). Transcripts per million (TPM) were calculated based on mapped read counts per gene; fold change (FC) and P values of differential genes are as reported by DESeq2.

Table 2.

Differentially expressed genes in whole blood of rs13361189 risk allele carriers versus noncarriers

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Mean TPM (Ref) | Mean TPM (Risk) | Risk Versus Ref FC | Risk Versus Ref P Value | Risk vs. Ref-Adjusted P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADGRV1 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor V1 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 1.80 | 1.34E−08 | 0.0003 |

| ADGRB2 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor B2 | 0.53 | 1.1 | 1.80 | 3.23E−08 | 0.0003 |

| FNDC9 | Fibronectin type III domain containing 9 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 1.70 | 8.88E−08 | 0.0006 |

| LOC101928943 | — | 0.18 | 0.35 | 1.83 | 1.38E−07 | 0.0007 |

| MLLT11 | MLLT11, transcription factor 7 cofactor | 1.87 | 2.57 | 1.36 | 4.97E−07 | 0.0021 |

| RTKN | Rhotekin | 0.68 | 1.08 | 1.62 | 6.82E−07 | 0.0023 |

| P2RY14 | Purinergic receptor P2Y14 | 1.0 | 0.63 | −1.70 | 9.81E−07 | 0.0029 |

| CELSR2 | Cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor 2 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 1.47 | 1.95E−06 | 0.0045 |

| TUBB4A | Tubulin β 4A class IVa | 1.22 | 2.33 | 1.63 | 1.79E−06 | 0.0045 |

| REEP2 | Receptor accessory protein 2 | 0.46 | 0.78 | 1.54 | 2.84E−06 | 0.0059 |

| HIST1H2BN | Histone cluster 1 H2B family member n | 1.11 | 1.54 | 1.54 | 3.46E−06 | 0.0065 |

| ASTN2 | Astrotactin 2 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 1.52 | 4.34E−06 | 0.0075 |

| ADGRB1 | Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor B1 | 0.46 | 0.71 | 1.48 | 1.37E−05 | 0.0202 |

| MSLN | Mesothelin | 1.11 | 0.47 | −1.71 | 1.32E−05 | 0.0202 |

| ATP1A3 | ATPase Na+-K+ transporting subunit α 3 | 1.77 | 2.91 | 1.53 | 2.03E−05 | 0.0280 |

| DNAJB5 | DnaJ heat shock protein family member B5 | 0.94 | 1.26 | 1.40 | 2.32E−05 | 0.0281 |

| ST5 | Suppression of tumorigenicity 5 | 0.5 | 0.60 | 1.45 | 2.24E−05 | 0.0281 |

| HRH4 | Histamine receptor H4 | 0.51 | 0.23 | −1.68 | 2.48E−05 | 0.0284 |

| LINC00623 | Long intergenic nonprotein coding RNA 623 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 1.68 | 3.14E−05 | 0.0324 |

| SAMD9L | Sterile α motif domain containing 9 like | 8.94 | 6.74 | −1.38 | 3.12E−05 | 0.0324 |

| FEZ1 | Fasciculation and elongation protein zeta 1 | 2.11 | 3.51 | 1.55 | 4.68E−05 | 0.0434 |

| GBP1 | Guanylate binding protein 1 | 14.84 | 10.65 | −1.47 | 5.62E−05 | 0.0434 |

| IFI44 | Interferon induced protein 44 | 8.63 | 3.96 | −1.54 | 6.09E−05 | 0.0434 |

| KCNJ5 | Potassium voltage-gated ch. subfamily J memb 5 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 1.62 | 5.56E−05 | 0.0434 |

| MANEAL | Mannosidase endo-α like | 0.34 | 0.48 | 1.37 | 5.13E−05 | 0.0434 |

| S100B | S100 calcium binding protein B | 5.7 | 11.80 | 1.53 | 5.74E−05 | 0.0434 |

| SCARNA17 | Small Cajal body-specific RNA 17 | 7.62 | 11.07 | 1.56 | 4.67E−05 | 0.0434 |

| SMIM18 | Small integral membrane protein 18 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 1.65 | 6.07E−05 | 0.0434 |

| TYRO3 | TYRO3 protein tyrosine kinase | 0.22 | 0.35 | 1.49 | 5.54E−05 | 0.0434 |

Differentially expressed genes (false discovery rate < 0.05) in whole blood between subjects homozygous major (reference) at rs13361189 versus those with a risk allele (heterozygous + homozygous risk). Transcripts per million (TPM) were calculated based on mapped read counts per gene; fold change (FC) and P values of differential genes are as reported by DESeq2.

Relationship of IRGM SNPs to CD and UC.

Aiming to confirm the relationship reported by others of these three IRGM SNPs to IBD, we conducted a case-control study of IBD within the NIEHS EPR. Given that there were very few cases of IBD among non-Hispanic Black, Asian, and Hispanic subjects in the EPR population (not shown), we focused our analysis upon non-Hispanic White subjects. Control subjects for CD and UC were nonidentical given that they were defined through answering “no” to a doctor diagnosis of CD or UC, respectively. Our study population, depicted in Table 3, included 45 subjects with CD (n = 2,716 controls) and 94 subjects with UC (n = 2,671 controls). Cases and controls were generally similar for demographic variables and smoking status, with the exception of UC controls, which were modestly younger than UC cases.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the study population

| CD | Controls | P value | UC | Controls | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 24 | 2,716 | 94 | 2,671 | ||

| Age, yr [mean (SD)] | 49.73 (12.41) | 52.04 (16.43) | 0.35 | 55.66 (15.21) | 51.88 (16.4) | 0.03 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male subjects, n (%) | 12 (27) | 1,103 (41) | 0.06 | 30 (32) | 1,087 (41) | 0.09 |

| Female subjects, n (%) | 33 (73) | 1,613 (59) | 64 (68) | 1,584 (59) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 [mean (SD)] | 26.94 (5.76) | 27.65 (6.19) | 0.44 | 27.21 (6.22) | 27.65 (6.18) | 0.5 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Smoker, n (%) | 21 (47) | 1,179 (44) | 0.68 | 40 (43) | 1,158 (44) | 0.92 |

| Nonsmoker, n (%) | 24 (53) | 1,526 (56) | 53 (57) | 1,503 (57) |

Subjects (4,125) responded “yes” or “no” to Crohn’s disease (CD) and/or ulcerative colitis (UC). Participant numbers in table categories vary due to nonresponse/missing data for specific variables. BMI, body mass index; IRGM, immunity-related GTPase family M.

The three IRGM SNPs were all confirmed to be in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium in both CD controls (P > 0.5) and UC controls (P > 0.8). As shown in Tables 4 and 5, genotype and minor allele frequencies were calculated for the three SNPs in CD and UC cases and respective controls. For all three SNPs, in both CD and UC, the minor allele frequencies were not statistically different between cases and controls. Inspection of the distribution of genotype frequencies, however, indicated a approximately sevenfold higher frequency of homozygous minor allele subjects among CD cases than controls (Table 4).

Table 4.

Genotype and allele frequencies for IRGM SNPs in CD study population

| Genotype, n (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | MAF | P Value | |||

| rs10065172 | CC | CT | TT | ||

| Cases | 40 (88.9) | 3 (6.7) | 2 (4.4) | 0.078 | 0.84 |

| Controls | 2,276 (83.8) | 423 (15.6) | 17 (0.6) | 0.084 | |

| rs13361189 | TT | TC | CC | ||

| Cases | 40 (88.9) | 3 (6.7) | 2 (4.4) | 0.078 | 0.84 |

| Controls | 2,274 (83.7) | 425 (15.7) | 17 (0.6) | 0.084 | |

| rs9637876 | CC | CT | TT | ||

| Cases | 40 (88.9) | 3 (6.7) | 2 (4.4) | 0.078 | 0.89 |

| Controls | 2,284 (84.1) | 415 (15.3) | 16 (0.6) | 0.082 | |

IRGM, immunity-related GTPase family M; CD, Crohn’s disease; MAF, minor allele frequency; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Table 5.

Genotype and allele frequencies for IRGM SNPs in UC study population

| Genotype, n (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | MAF | P Value | |||

| rs10065172 | CC | CT | TT | ||

| Cases | 76 (80.9%) | 17 (18.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.101 | 0.38 |

| Control | 2,244 (84.0) | 409 (15.3) | 18 (0.7) | 0.083 | |

| rs13361189 | TT | CT | CC | ||

| Cases | 76 (80.9) | 17 (18.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0.101 | 0.38 |

| Control | 2,243 (84.0) | 410 (15.4) | 18 (0.7) | 0.083 | |

| rs9637876 | CC | CT | TT | ||

| Cases | 76 (80.9) | 17 (18.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0.101 | 0.33 |

| Control | 2,252 (84.3) | 401 (15.0) | 17 (0.6) | 0.081 | |

IRGM, immunity-related GTPase family M; CD, Crohn’s disease; MAF, minor allele frequency; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; UC, ulcerative colitis.

To better define the relationship of IRGM genotypes at these three loci with IBD risk, we performed logistic regression. A recessive model (homozygous minor versus heterozygous + homozygous major) was applied. As shown in Table 6, minor homozygous status at all three loci was associated with significantly increased risk for CD, in both unadjusted models and after adjustment for age, sex, tobacco use, and BMI. By contrast, there was no significant relationship between the IRGM SNPs and UC diagnosis.

Table 6.

Unadjusted and adjusted ORs for the relationship between IRGM SNP minor alleles and inflammatory bowel disease

| CD |

UC |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | OR (95% CI) unadjusted | OR (95% CI) adjusted* | OR (95% CI) unadjusted | OR (95% CI) adjusted* |

| rs10065172 | 7.38 (1.65–32.96) | 7.71 (1.71–34.80) | 1.58 (0.21–12.00) | 1.59 (0.21–12.10) |

| rs13361189 | 7.38 (1.65–32.96) | 7.71 (1.71–34.80) | 1.58 (0.21–12.00) | 1.59 (0.21–12.10) |

| rs9637876 | 7.85 (1.75–35.18) | 8.20 (1.80–37.24) | 1.68 (0.22–12.74) | 1.76 (0.23–13.45) |

Logistic regression of risk associated with homozygous minor allele genotype compared with heterozygous + homozygous major allele genotypes. IRGM, immunity-related GTPase family M; CD, Crohn’s disease; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Covariates adjusted for were age, sex, tobacco use, and body mass index.

Our case-control study was nested within a larger EPR study population that by design included all subjects in the EPR who had answered “yes” to any of 10 autoimmune diseases (including CD and UC) plus controls without autoimmune disease. Consequently, autoimmune disease was overrepresented [prevalence, 697/2713 (25.69%)] in our CD control group (which was defined as all subjects who replied “no” to a CD diagnosis) compared with the overall non-Hispanic White EPR population [prevalence, 785/6169 (12.72%)]. To address the possibility that our findings for CD might somehow be driven by the excess of autoimmune disease among controls, we performed a sensitivity analysis, weighting all participants (controls and cases) with autoimmune disease to simulate the lower frequency of autoimmune disease in the overall EPR population. As is shown in Table 7, the relationship of the three IRGM SNPs to CD persisted in this weighted sensitivity analysis. In a second sensitivity analysis, we removed all subjects from the control group that had autoimmune disease and re-ran the logistic regression. The statistically significant increase in CD risk associated with the three IRGM SNPs again persisted (data not shown).

Table 7.

Sensitivity analysis of relationship of IRGM SNPs to CD

| SNP | OR | Lower Confidence Limit | Upper Confidence Limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs10065172 | 7.503 | 1.271 | 44.280 |

| rs13361189 | 7.503 | 1.271 | 44.280 |

| rs9637876 | 7.801 | 1.317 | 46.188 |

Logistic regression (adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, and smoking) of risk associated with homozygous minor allele genotype compared with heterozygous + homozygous major allele genotypes. Model was weighted to correct for increased frequency of autoimmune disease in study population as compared with overall Environmental Polymorphisms Registry. IRGM, immunity-related GTPase family; CD, Crohn’s disease; OR; odds ratio; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

DISCUSSION

Genetic association studies have linked allelic variants in autophagy genes to IBD pathogenesis (19, 38, 43). Autophagy, an evolutionarily conserved process that delivers endogenous and exogenous intracellular cargo to lysosomes for degradation, as well as autophagy-related processes, have been shown to mediate several key maintenance functions in the intestinal mucosa, including epithelial barrier integrity, intracellular pathogen clearance, Paneth cell and goblet cell secretion, and suppression of inflammation (25). Among autophagy genes that have been implicated in CD risk, IRGM has been proposed to serve as a master regulator by promoting the activation and assembly of several core autophagy proteins in response to microbial signals and other inflammatory stressors (7). IRGM thus promotes cellular clearance of CD-associated cell-invasive bacteria and suppresses cytokines during inflammation (7, 24).

Resequencing of the IRGM gene in large numbers of subjects has identified no nonsynonymous polymorphisms that modify IBD risk, suggesting that genetic variation in IRGM influences IBD only through regulating IRGM expression (39). Here, we investigated three CD-associated IRGM SNPs, rs10065172, rs13361189, and rs9637876, in relation to IRGM expression in GTEx and IBD risk in the NIEHS EPR. All three SNPs are in LD with a 20-kb deletion upstream of IRGM that has been proposed to be the causal variant through impacting gene expression (33). Contrary to this, one report indicates that allele-specific binding of miR-196 at rs10065172 during inflammatory conditions differentially regulates IRGM expression, suggesting that rs10065172 may be the causal risk locus in the haplotype (5).

Among the few studies to date that have investigated the relationship of this IRGM haplotype to IRGM expression, one monitored allele-specific expression of the exonic SNP rs10065172 (+313C>T) as a haplotype tag in a panel of cell lines and noted that allelic expression dominance was cell type dependent (33). Expanding upon this, we analyzed the relationship of each of the three IRGM SNPs to IRGM expression in primary human tissues relevant to IBD. We report that the minor alleles rs10065172 T and rs13361189 C are associated with reduced IRGM mRNA in whole blood. This is consistent with a prior report that the rs10065172 T allele had lower expression than rs10065172 C in peripheral blood lymphocytes from CD patients (41). In contrast to our finding, however, another report found that rs10065172 T was associated with higher IRGM protein expression in the intestinal mucosa of CD patients (5). We also found that a T (minor) allele at rs9637876, an IRGM promoter SNP that is in high LD with rs13361189 and rs10065172 in Europeans but not Africans, was associated with reduced IRGM expression, but this relationship fell short of statistical significance. While we are unaware of any prior publications that have correlated rs9637876 to IRGM expression in primary cells, a rs9637876 T promoter construct was previously noted to support higher expression of a luciferase reporter than its rs9637876 C counterpart in the human monocytic cell line THP1 (20).

An unbiased search in GTEx for differentially expressed genes between rs13361189 risk allele carriers and noncarriers yielded 3 genes in ileum and 29 genes in whole blood at FDR <0.05 (Tables 1 and 2). Of interest, there is no overlap between the two gene sets, suggesting, with the caveat of limited statistical power due to the relatively low sample size, that rs13361189 may in many cases act as a tissue-specific eQTL. The smaller gene list for ileum as compared with blood likely reflects, at least in part, the smaller n for this tissue in our analysis. Our identification of differentially expressed genes using a stringent statistical approach, among them, several that have previously been implicated in CD pathogenesis, suggests that the strategy of profiling gene expression in disease target tissues of genetically susceptible populations may afford disease insights even in cases of limited sample size.

A few differentially expressed genes are worthy of comment. Of interest, zinc finger protein 300 pseudogene 1 (ZNF300P1), upregulated specifically in ileum of risk allele carriers (Table 1), is located nearby the IRGM locus and, like IRGM, has been implicated in IBD risk on the basis of its proximity to risk SNPs in the region (21). Generally consistent with our findings in GTEx, a recent study of IBD patients found that rs11741861 (a SNP located in an intron of IRGM and associated with IBD risk; Ref. 21) was an intestine-specific cis-eQTL for ZNF300P1, with risk allele carriers exhibiting increased ZNF300P1 expression (12). ZNF300P1 is reported to encode a lincRNA that regulates polarity, proliferation, migration, and adhesion in ovarian cancer cells (16), perhaps suggesting that it may impact wound healing or other epithelial functions in IBD. ZNF300P1 has been shown to interact with chromatin-modifying proteins, suggesting that its primary function may be to regulate expression of other genes (22). Its genomic proximity to IRGM and inverse expression to IRGM in relation to rs13361189 suggests that expression of ZNF300P1 and IRGM may be coupled through shared regulatory elements. Alternatively, it is intriguing to consider that ZNF300P1 may itself regulate IRGM expression, perhaps mediating the observed relationship between regional SNPs and IRGM.

Also upregulated in intestine of risk allele carriers was lactotransferrin (i.e., lactoferrin) (Table 1). Of interest, fecal lactoferrin, likely deriving from neutrophils and/or intestinal glandular epithelial cells, is an established biomarker of CD diagnosis and activity (35, 52) that has antibacterial and anti-inflammatory function (45). It is interesting to consider that its upregulation in ileum of subjects with the CD risk allele may indicate preclinical increases in neutrophil burden and/or epithelial activation.

Several differentially expressed genes in blood are also of note (Table 2). Three genes of the adhesion G protein-coupled receptor (ADGR) family are upregulated in whole blood of risk allele carriers, perhaps suggesting coordinate regulation. Among these, ADGRB1 [also known as brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1 (BAI1)] is a receptor expressed by myeloid cells that plays a key role in anti-inflammatory engulfment of apoptotic cells and in bacterial clearance (4, 40). Of interest, BAI1 deficiency exacerbates colitis in mice, whereas BAI1 overexpression attenuates it (26). Also upregulated in blood of risk allele carriers was TYRO3, like BAI1, a receptor that plays a role in anti-inflammatory clearance of apoptotic cells (46). While the significance of upregulation of these two genes in whole blood of risk allele carriers is uncertain, TYRO3 is reportedly upregulated in human monocyte-derived macrophages in response to chronic NOD2 stimulation (54). Histamine receptor H4 (HRH4), downregulated in whole blood of risk allele carriers (Table 2), has been shown to promote clinical and histopathological signs, as well as local and systemic inflammation in rodent colitis models (48). Fasciculation and elongation protein zeta 1 (FEZ1), upregulated in whole blood of risk allele carriers, and guanylate binding protein 1 (GBP1), downregulated in whole blood of risk allele carriers (Table 2), have been reported to suppress and promote autophagic flux, respectively (2, 34).

Our genome-wide trans-eQTL analysis may be subject to both false-negative and false-positive findings. Like IRGM itself, TNF failed to display genome-wide statistical significance. Future, better-powered studies with larger numbers of risk allele homozygous subjects may be required to better define the relationship of these genes to IRGM SNPs. The potential limitations of our approach notwithstanding, profiling gene expression in target tissues in subjects with disease risk alleles may conceivably facilitate future development of pharmacogenomic or other “personalized medicine” approaches in CD. We speculate that IRGM polymorphisms induce subclinical molecular changes in tissue that predispose to CD in the context of additional gene × gene and/or gene × environment interactions.

We found that homozygous minor allele status at rs13361189 and rs10065172 were both (as expected given their very high LD) associated with increased risk for CD, but not for UC. Like us, several prior reports have found an association of rs13361189 with CD risk (3, 15, 27, 32, 36, 38, 41, 44, 47). On the other hand, rs10065172 has been found to associate with CD in some (15, 36, 41), but not all (27) studies. It has been proposed that differences in findings relating to IRGM across different study populations may arise from a combination of differences in allele frequency and effect size (29). Although some prior investigators, like us, found no association of rs13361189 or rs10065172 with UC (14, 15, 44, 47), others have found an association of these risk loci to UC (38). We also found that minor allele status at rs9637872 was associated with CD in our study population of White subjects. This is expected given its high LD with the two other IRGM loci in Europeans. One prior report has found an association of rs9637872 with CD in an Indian study population (3), but we are unaware of prior reports of this finding in White patients.

A notable difference between our report and others is that, although the homozygous minor allele genotype was aproximately sevenfold overrepresented among cases compared with controls, we did not find higher overall minor allele frequencies for rs13361189 or rs10065172 among cases. This appears largely to reflect substantial (>2-fold) overrepresentation of heterozygotes among controls, a finding that has not been previously noted, to our knowledge. Consequently, we found increased risk for CD using a recessive genetic model (minor versus heterozygote plus major), whereas no significant change in risk was found using a dominant model (minor plus heterozygote versus major) (data not shown).

Our analysis had some limitations. Because of the modest number of cases, statistical power to detect a relationship of the IRGM SNPs to UC was limited. The modest number of CD cases may have also reduced the precision of our point estimates of risk, which were significantly higher than most prior reports, which have generally calculated ORs of ~1.3–1.7 for rs13361189 in relation to CD (38, 41). Finally, we restricted our analysis to non-Hispanic White subjects due to the small number of cases in other racial/ethnic backgrounds. Thus our conclusions are limited to this demographic subset.

Taken together, we report that IRGM rs13361189, rs10065172, and rs9637876 are associated with altered expression of IRGM and other IBD-related genes in humans, and we confirm prior reports of these three polymorphic sites as risk loci for CD in Caucasian subjects. Future studies are warranted to better define whether IRGM protein expression is differentially regulated within specific cell types in the intestine and bloodstream. We propose that IRGM polymorphisms should be examined in relation to additional inflammatory diseases, and that an improved understanding of how these loci interact with the cell-specific microenvironment may potentially uncover novel strategies for manipulating IRGM expression during human disease.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant Z01-ES-102005. The GTEx Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health and by National Cancer Institute; National Human Genome Research Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institute of Mental Health; and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.R., R.F., and J.C. conceived and designed research; T.A., C.L.I., S.A.G., P.R., R.F., and J.A.M. performed experiments; T.A., C.L.I., S.A.G., P.R., J.C., X.W., D.A.B., J.A.M., S.H.S., and M.B.F. analyzed data; T.A., C.L.I., S.A.G., P.R., J.C., X.W., D.A.B., J.A.M., S.H.S., and M.B.F. interpreted results of experiments; S.A.G., P.R., and M.B.F. prepared figures; T.A., C.L.I., S.A.G., and M.B.F. drafted manuscript; T.A., C.L.I., S.A.G., P.R., J.C., X.W., D.A.B., J.A.M., S.H.S., and M.B.F. edited and revised manuscript; T.A., C.L.I., S.A.G., P.R., R.F., J.C., X.W., D.A.B., J.A.M., S.H.S., and M.B.F. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agus A, Denizot J, Thévenot J, Martinez-Medina M, Massier S, Sauvanet P, Bernalier-Donadille A, Denis S, Hofman P, Bonnet R, Billard E, Barnich N. Western diet induces a shift in microbiota composition enhancing susceptibility to Adherent-Invasive E. coli infection and intestinal inflammation. Sci Rep 6: 19032, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep19032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Zeer MA, Al-Younes HM, Lauster D, Abu Lubad M, Meyer TF. Autophagy restricts Chlamydia trachomatis growth in human macrophages via IFNG-inducible guanylate binding proteins. Autophagy 9: 50–62, 2013. doi: 10.4161/auto.22482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baskaran K, Pugazhendhi S, Ramakrishna BS. Association of IRGM gene mutations with inflammatory bowel disease in the Indian population. PLoS One 9: e106863, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billings EA, Lee CS, Owen KA, D’Souza RS, Ravichandran KS, Casanova JE. The adhesion GPCR BAI1 mediates macrophage ROS production and microbicidal activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Sci Signal 9: ra14, 2016. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aac6250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brest P, Lapaquette P, Souidi M, Lebrigand K, Cesaro A, Vouret-Craviari V, Mari B, Barbry P, Mosnier JF, Hébuterne X, Harel-Bellan A, Mograbi B, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Hofman P. A synonymous variant in IRGM alters a binding site for miR-196 and causes deregulation of IRGM-dependent xenophagy in Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet 43: 242–245, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ng.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadwell K. Crosstalk between autophagy and inflammatory signalling pathways: balancing defence and homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol 16: 661–675, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chauhan S, Mandell MA, Deretic V. IRGM governs the core autophagy machinery to conduct antimicrobial defense. Mol Cell 58: 507–521, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chulada PC, Vahdat HL, Sharp RR, DeLozier TC, Watkins PB, Pusek SN, Blackshear PJ. The Environmental Polymorphisms Registry: a DNA resource to study genetic susceptibility loci. Hum Genet 123: 207–214, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chulada PC, Vainorius E, Garantziotis S, Burch LH, Blackshear PJ, Zeldin DC. The Environmental Polymorphism Registry: a unique resource that facilitates translational research of environmental disease. Environ Health Perspect 119: 1523–1527, 2011. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen BL, Sachar DB. Update on anti-tumor necrosis factor agents and other new drugs for inflammatory bowel disease. BMJ 357: j2505, 2017. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deretic V. Autophagy in leukocytes and other cells: mechanisms, subsystem organization, selectivity, and links to innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol 100: 969–978, 2016. doi: 10.1189/jlb.4MR0216-079R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Narzo AF, Peters LA, Argmann C, Stojmirovic A, Perrigoue J, Li K, Telesco S, Kidd B, Walker J, Dudley J, Cho J, Schadt EE, Kasarskis A, Curran M, Dobrin R, Hao K. Blood and intestine eQTLs from an anti-TNF-resistant Crohn’s disease cohort inform IBD genetic association loci. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 7: e177, 2016. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29: 15–21, 2013. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher SA, Tremelling M, Anderson CA, Gwilliam R, Bumpstead S, Prescott NJ, Nimmo ER, Massey D, Berzuini C, Johnson C, Barrett JC, Cummings FR, Drummond H, Lees CW, Onnie CM, Hanson CE, Blaszczyk K, Inouye M, Ewels P, Ravindrarajah R, Keniry A, Hunt S, Carter M, Watkins N, Ouwehand W, Lewis CM, Cardon L; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium; Lobo A, Forbes A, Sanderson J, Jewell DP, Mansfield JC, Deloukas P, Mathew CG, Parkes M, Satsangi J. Genetic determinants of ulcerative colitis include the ECM1 locus and five loci implicated in Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet 40: 710–712, 2008. doi: 10.1038/ng.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glas J, Seiderer J, Bues S, Stallhofer J, Fries C, Olszak T, Tsekeri E, Wetzke M, Beigel F, Steib C, Friedrich M, Göke B, Diegelmann J, Czamara D, Brand S. IRGM variants and susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease in the German population. PLoS One 8: e54338, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gloss B, Moran-Jones K, Lin V, Gonzalez M, Scurry J, Hacker NF, Sutherland RL, Clark SJ, Samimi G. ZNF300P1 encodes a lincRNA that regulates cell polarity and is epigenetically silenced in type II epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer 13: 3, 2014. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham DB, Xavier RJ. From genetics of inflammatory bowel disease towards mechanistic insights. Trends Immunol 34: 371–378, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haldar AK, Piro AS, Finethy R, Espenschied ST, Brown HE, Giebel AM, Frickel EM, Nelson DE, Coers J. Chlamydia trachomatis is resistant to inclusion ubiquitination and associated host defense in gamma interferon-primed human epithelial cells. MBio 7: e01417-16, 2016. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01417-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hampe J, Franke A, Rosenstiel P, Till A, Teuber M, Huse K, Albrecht M, Mayr G, De La Vega FM, Briggs J, Günther S, Prescott NJ, Onnie CM, Häsler R, Sipos B, Fölsch UR, Lengauer T, Platzer M, Mathew CG, Krawczak M, Schreiber S. A genome-wide association scan of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for Crohn disease in ATG16L1. Nat Genet 39: 207–211, 2007. doi: 10.1038/ng1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Intemann CD, Thye T, Niemann S, Browne EN, Amanua Chinbuah M, Enimil A, Gyapong J, Osei I, Owusu-Dabo E, Helm S, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Horstmann RD, Meyer CG. Autophagy gene variant IRGM -261T contributes to protection from tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis but not by M. africanum strains. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000577, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, Lee JC, Schumm LP, Sharma Y, Anderson CA, Essers J, Mitrovic M, Ning K, Cleynen I, Theatre E, Spain SL, Raychaudhuri S, Goyette P, Wei Z, Abraham C, Achkar JP, Ahmad T, Amininejad L, Ananthakrishnan AN, Andersen V, Andrews JM, Baidoo L, Balschun T, Bampton PA, Bitton A, Boucher G, Brand S, Büning C, Cohain A, Cichon S, D’Amato M, De Jong D, Devaney KL, Dubinsky M, Edwards C, Ellinghaus D, Ferguson LR, Franchimont D, Fransen K, Gearry R, Georges M, Gieger C, Glas J, Haritunians T, Hart A, Hawkey C, Hedl M, Hu X, Karlsen TH, Kupcinskas L, Kugathasan S, Latiano A, Laukens D, Lawrance IC, Lees CW, Louis E, Mahy G, Mansfield J, Morgan AR, Mowat C, Newman W, Palmieri O, Ponsioen CY, Potocnik U, Prescott NJ, Regueiro M, Rotter JI, Russell RK, Sanderson JD, Sans M, Satsangi J, Schreiber S, Simms LA, Sventoraityte J, Targan SR, Taylor KD, Tremelling M, Verspaget HW, De Vos M, Wijmenga C, Wilson DC, Winkelmann J, Xavier RJ, Zeissig S, Zhang B, Zhang CK, Zhao H; International IBD Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC); Silverberg MS, Annese V, Hakonarson H, Brant SR, Radford-Smith G, Mathew CG, Rioux JD, Schadt EE, Daly MJ, Franke A, Parkes M, Vermeire S, Barrett JC, Cho JH. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 491: 119–124, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khalil AM, Guttman M, Huarte M, Garber M, Raj A, Rivea Morales D, Thomas K, Presser A, Bernstein BE, van Oudenaarden A, Regev A, Lander ES, Rinn JL. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 11667–11672, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904715106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai L, Azzam KM, Lin WC, Rai P, Lowe JM, Gabor KA, Madenspacher JH, Aloor JJ, Parks JS, Näär AM, Fessler MB. MicroRNA-33 regulates the innate immune response via atp binding cassette transporter-mediated remodeling of membrane microdomains. J Biol Chem 291: 19651–19660, 2016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.723056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lapaquette P, Bringer MA, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Defects in autophagy favour adherent-invasive Escherichia coli persistence within macrophages leading to increased pro-inflammatory response. Cell Microbiol 14: 791–807, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lassen KG, Xavier RJ. Genetic control of autophagy underlies pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol 10: 589–597, 2017. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee CS, Penberthy KK, Wheeler KM, Juncadella IJ, Vandenabeele P, Lysiak JJ, Ravichandran KS. Boosting apoptotic cell clearance by colonic epithelial cells attenuates inflammation in vivo. Immunity 44: 807–820, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Feng ST, Yao Y, Yang L, Xing Y, Wang Y, You JH. Correlation between IRGM genetic polymorphisms and Crohn’s disease risk: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Genet Mol Res 13: 10741–10753, 2014. doi: 10.4238/2014.December.18.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30: 923–930, 2014. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, Ng SC, Alberts R, Takahashi A, Ripke S, Lee JC, Jostins L, Shah T, Abedian S, Cheon JH, Cho J, Dayani NE, Franke L, Fuyuno Y, Hart A, Juyal RC, Juyal G, Kim WH, Morris AP, Poustchi H, Newman WG, Midha V, Orchard TR, Vahedi H, Sood A, Sung JY, Malekzadeh R, Westra HJ, Yamazaki K, Yang SK; International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium; International IBD Genetics Consortium; Barrett JC, Alizadeh BZ, Parkes M, Bk T, Daly MJ, Kubo M, Anderson CA, Weersma RK. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet 47: 979–986, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ng.3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15: 550, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowe JM, Nguyen TA, Grimm SA, Gabor KA, Peddada SD, Li L, Anderson CW, Resnick MA, Menendez D, Fessler MB. The novel p53 target TNFAIP8 variant 2 is increased in cancer and offsets p53-dependent tumor suppression. Cell Death Differ 24: 181–191, 2017. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y, Li CY, Lin SS, Yuan P. IRGM rs13361189 polymorphism may contribute to susceptibility to Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med 8: 607–613, 2014. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarroll SA, Huett A, Kuballa P, Chilewski SD, Landry A, Goyette P, Zody MC, Hall JL, Brant SR, Cho JH, Duerr RH, Silverberg MS, Taylor KD, Rioux JD, Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Xavier RJ. Deletion polymorphism upstream of IRGM associated with altered IRGM expression and Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet 40: 1107–1112, 2008. doi: 10.1038/ng.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKnight NC, Jefferies HB, Alemu EA, Saunders RE, Howell M, Johansen T, Tooze SA. Genome-wide siRNA screen reveals amino acid starvation-induced autophagy requires SCOC and WAC. EMBO J 31: 1931–1946, 2012. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ministro P, Martins D. Fecal biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease: how, when and why? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 11: 317–328, 2017. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2017.1292128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moon CM, Shin DJ, Kim SW, Son NH, Park A, Park B, Jung ES, Kim ES, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Associations between genetic variants in the IRGM gene and inflammatory bowel diseases in the Korean population. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19: 106–114, 2013. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orholm M, Munkholm P, Langholz E, Nielsen OH, Sørensen TI, Binder V. Familial occurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med 324: 84–88, 1991. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101103240203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palomino-Morales RJ, Oliver J, Gómez-García M, López-Nevot MA, Rodrigo L, Nieto A, Alizadeh BZ, Martín J. Association of ATG16L1 and IRGM genes polymorphisms with inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis approach. Genes Immun 10: 356–364, 2009. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parkes M, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ, Tremelling M, Anderson CA, Fisher SA, Roberts RG, Nimmo ER, Cummings FR, Soars D, Drummond H, Lees CW, Khawaja SA, Bagnall R, Burke DA, Todhunter CE, Ahmad T, Onnie CM, McArdle W, Strachan D, Bethel G, Bryan C, Lewis CM, Deloukas P, Forbes A, Sanderson J, Jewell DP, Satsangi J, Mansfield JC; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium; Cardon L, Mathew CG. Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Nat Genet 39: 830–832, 2007. doi: 10.1038/ng2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penberthy KK, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell recognition receptors and scavenger receptors. Immunol Rev 269: 44–59, 2016. doi: 10.1111/imr.12376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prescott NJ, Dominy KM, Kubo M, Lewis CM, Fisher SA, Redon R, Huang N, Stranger BE, Blaszczyk K, Hudspith B, Parkes G, Hosono N, Yamazaki K, Onnie CM, Forbes A, Dermitzakis ET, Nakamura Y, Mansfield JC, Sanderson J, Hurles ME, Roberts RG, Mathew CG. Independent and population-specific association of risk variants at the IRGM locus with Crohn’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 19: 1828–1839, 2010. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Racine A, Carbonnel F, Chan SS, Hart AR, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Oldenburg B, van Schaik FD, Tjønneland A, Olsen A, Dahm CC, Key T, Luben R, Khaw KT, Riboli E, Grip O, Lindgren S, Hallmans G, Karling P, Clavel-Chapelon F, Bergman MM, Boeing H, Kaaks R, Katzke VA, Palli D, Masala G, Jantchou P, Boutron-Ruault MC. Dietary patterns and risk of inflammatory bowel disease in europe: results from the EPIC study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 22: 345–354, 2016. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rivas MA, Beaudoin M, Gardet A, Stevens C, Sharma Y, Zhang CK, Boucher G, Ripke S, Ellinghaus D, Burtt N, Fennell T, Kirby A, Latiano A, Goyette P, Green T, Halfvarson J, Haritunians T, Korn JM, Kuruvilla F, Lagacé C, Neale B, Lo KS, Schumm P, Törkvist L; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium (NIDDK IBDGC); United Kingdom Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium; International Inflammatory Bowel Disease Genetics Consortium; Dubinsky MC, Brant SR, Silverberg MS, Duerr RH, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Lettre G, Franke A, D’Amato M, McGovern DP, Cho JH, Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Daly MJ. Deep resequencing of GWAS loci identifies independent rare variants associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet 43: 1066–1073, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ng.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts RL, Hollis-Moffatt JE, Gearry RB, Kennedy MA, Barclay ML, Merriman TR. Confirmation of association of IRGM and NCF4 with ileal Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort. Genes Immun 9: 561–565, 2008. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosa L, Cutone A, Lepanto MS, Paesano R, Valenti P. Lactoferrin: a natural glycoprotein involved in iron and inflammatory homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci 18: E1985, 2017. doi: 10.3390/ijms18091985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rothlin CV, Carrera-Silva EA, Bosurgi L, Ghosh S. TAM receptor signaling in immune homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol 33: 355–391, 2015. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rufini S, Ciccacci C, Di Fusco D, Ruffa A, Pallone F, Novelli G, Biancone L, Borgiani P. Autophagy and inflammatory bowel disease: Association between variants of the autophagy-related IRGM gene and susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis 47: 744–750, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schirmer B, Rezniczek T, Seifert R, Neumann D. Proinflammatory role of the histamine H4 receptor in dextrane sodium sulfate-induced acute colitis. Biochem Pharmacol 98: 102–109, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson NP, Driscoll R, Pounder RE, Wakefield AJ. Genetics versus environment in inflammatory bowel disease: results of a British twin study. BMJ 312: 95–96, 1996. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tysk C, Lindberg E, Järnerot G, Flodérus-Myrhed B. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in an unselected population of monozygotic and dizygotic twins. A study of heritability and the influence of smoking. Gut 29: 990–996, 1988. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.7.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uniken Venema WT, Voskuil MD, Dijkstra G, Weersma RK, Festen EA. The genetic background of inflammatory bowel disease: from correlation to causality. J Pathol 241: 146–158, 2017. doi: 10.1002/path.4817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright EK, Kamm MA, De Cruz P, Hamilton AL, Ritchie KJ, Keenan JI, Leach S, Burgess L, Aitchison A, Gorelik A, Liew D, Day AS, Gearry RB. Comparison of fecal inflammatory markers in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 22: 1086–1094, 2016. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yadav P, Ellinghaus D, Rémy G, Freitag-Wolf S, Cesaro A, Degenhardt F, Boucher G, Delacre M; International IBD Genetics Consortium; Peyrin-Biroulet L, Pichavant M, Rioux JD, Gosset P, Franke A, Schumm LP, Krawczak M, Chamaillard M, Dempfle A, Andersen V. Genetic factors interact with tobacco smoke to modify risk for inflammatory bowel disease in humans and mice. Gastroenterology 153: 550–565, 2017. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng S, Hedl M, Abraham C. TAM receptor-dependent regulation of SOCS3 and MAPKs contributes to proinflammatory cytokine downregulation following chronic NOD2 stimulation of human macrophages. J Immunol 194: 1928–1937, 2015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]