Abstract

The anion exchanger SAT-1 [sulfate anion transporter 1 (Slc26a1)] is considered an important regulator of oxalate and sulfate homeostasis, but the mechanistic basis of these critical roles remain undetermined. Previously, characterization of the SAT-1-knockout (KO) mouse suggested that the loss of SAT-1-mediated oxalate secretion by the intestine was responsible for the hyperoxaluria, hyperoxalemia, and calcium oxalate urolithiasis reportedly displayed by this model. To test this hypothesis, we compared the transepithelial fluxes of 14C-oxalate, 35, and 36Cl− across isolated, short-circuited segments of the distal ileum, cecum, and distal colon from wild-type (WT) and SAT-1-KO mice. The absence of SAT-1 did not impact the transport of these anions by any part of the intestine examined. Additionally, SAT-1-KO mice were neither hyperoxaluric nor hyperoxalemic. Instead, 24-h urinary oxalate excretion was almost 50% lower than in WT mice. With no contribution from the intestine, we suggest that this may reflect the loss of SAT-1-mediated oxalate efflux from the liver. SAT-1-KO mice were, however, profoundly hyposulfatemic, even though there were no changes to intestinal sulfate handling, and the renal clearances of sulfate and creatinine indicated diminished rates of sulfate reabsorption by the proximal tubule. Aside from this distinct sulfate phenotype, we were unable to reproduce the hyperoxaluria, hyperoxalemia, and urolithiasis of the original SAT-1-KO model. In conclusion, oxalate and sulfate transport by the intestine were not dependent on SAT-1, and we found no evidence supporting the long-standing hypothesis that intestinal SAT-1 contributes to oxalate and sulfate homeostasis.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY SAT-1 is a membrane-bound transport protein expressed in the intestine, liver, and kidney, where it is widely considered essential for the excretion of oxalate, a potentially toxic waste metabolite. Previously, calcium oxalate kidney stone formation by the SAT-1-knockout mouse generated the hypothesis that SAT-1 has a major role in oxalate excretion via the intestine. We definitively tested this proposal and found no evidence for SAT-1 as an intestinal anion transporter contributing to oxalate homeostasis.

Keywords: calcium oxalate urolithiasis, chloride, mouse, Slc26 gene family, Ussing chamber

INTRODUCTION

For mammals, the divalent anion oxalate is a nonfunctional end product of hepatic metabolism that is typically eliminated in the urine without complication. However, elevated urine oxalate (hyperoxaluria) is one of the main risk factors for the formation of insoluble calcium oxalate, the principal component of many kidney stones (5, 12, 72). In addition, the intestine can contribute to urinary oxalate output and hyperoxaluria through the absorption of dietary oxalate, but it is also capable of reducing urine oxalate levels by serving as a valuable extrarenal pathway for this waste metabolite (33, 34, 70, 88, 89). These important roles for the intestine in oxalate homeostasis and the pathophysiology of hyperoxaluria have therefore prompted investigations of the underlying transport mechanisms involved.

A combination of transcellular and paracellular pathways participate in the absorption and secretion of oxalate by the intestinal epithelium. The transcellular component depends on the coordination of secondary active membrane-bound transport proteins residing at the apical and basolateral poles of the enterocytes. Initial functional characterizations of these transport mechanisms suggested the involvement of several different anion exchangers (36–38, 47–49). Subsequent identification of the Slc26 gene family of multifunctional anion transporters, a number of which possess an affinity for oxalate and are expressed along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, have received the most attention thus far, raising the prospect of elucidating the individual transporters concerned (2, 34, 35, 70, 88).

With no selective pharmacological inhibitors for these transport proteins, knockout (KO) mice have been instrumental in revealing the contributions of several candidate Slc26s to intestinal oxalate transport and overall oxalate homeostasis. One of the first to be studied in this regard was Slc26a6, also known as PAT-1 [putative anion transporter 1], a chloride/bicarbonate (Cl−/) exchanger localized to the apical membrane (64, 82, 83). In two independently developed KO mouse strains, the absence of PAT-1 abolished net oxalate secretion by the small intestine, resulting in excess enteric oxalate absorption, which was associated with distinct hyperoxaluria in one model (22), in addition to hyperoxalemia and calcium oxalate urolithiasis in another (44). Both reports concluded that PAT-1 serves a major role in intestinal oxalate secretion.

Critical to oxalate moving across the intestinal epithelium from the blood into the gut lumen are the basolateral transporters operating in series with apical PAT-1. This is important because the basolateral membrane represents the first rate-limiting step for transcellular oxalate secretion, but to date the transport proteins involved have not been determined. Another member of the SLC26 gene family known as SAT-1 [sulfate anion transporter 1 (Slc26a1)] has been proposed to fulfill this key function (2, 41, 51, 58, 70). This is based on the characterization of the SAT-1-KO mouse, where oxalate uptake by basolateral membrane vesicles (BLMVs) from the distal ileum, cecum, and proximal colon of KO mice was reduced in vitro, and along with less oxalate measured within the cecal contents in vivo, the hyperoxaluria, hyperoxalemia, and calcium oxalate urolithiasis displayed by the SAT-1-KO model was linked to diminished intestinal oxalate secretion (17). However, almost a decade later, this proposed function for SAT-1 in the intestine has not been fully verified.

When expressed in vitro, SAT-1 can operate as a sulfate ()/ exchanger (27, 52, 67, 90), although this was not a characteristic of oxalate secretion across the mouse duodenum, and the SAT-1-KO mouse was subsequently used to rule against the participation of SAT-1 (51). Nevertheless, it remains an open question whether SAT-1 contributes to transepithelial oxalate secretion elsewhere along the GI tract, in particular the distal ileum and large intestine, where the SAT-1 protein was shown to be functionally expressed (17). The ileum is especially significant because this portion of the intestine is not only important for oxalate secretion, involving PAT-1 (22), but is also the main site of sulfate absorption (3, 6, 78). Recently, we demonstrated that the mechanism responsible for sulfate uptake by the mouse ileum was sensitive to serosal DIDS and Cl− dependent, consistent with basolateral /Cl− exchange (86), although whether SAT-1 also fulfils this function, as already proposed (2, 58, 84), has yet to be confirmed.

In addition to hyperoxaluria and hyperoxalemia, the SAT-1-KO mouse also displayed hypersulfaturia and hyposulfatemia, leading to the conclusion that SAT-1 is a key regulator of both oxalate and sulfate homeostasis (17). However, the mechanistic basis of these two critical functions are unknown, and there is no direct evidence specifically linking either of them to intestinal SAT-1 activity. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the contribution of SAT-1 to transepithelial oxalate and sulfate transport by the GI tract. In the following report, we present the results of Ussing chamber experiments comparing unidirectional oxalate, sulfate, and Cl− fluxes across the distal ileum, cecum, and distal colon from WT and SAT-1-KO mice, allowing us to formally test the hypothesis that intestinal SAT-1 functionally contributes to oxalate and sulfate homeostasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Animals

Breeding pairs of SAT-1-KO (Slc26a1−/−) mice on a C57BL/6 background were kindly provided by Dr. Peter Aronson (Yale University) and used to establish a colony at the University of Florida that was expanded and maintained by a homozygote × homozygote breeding scheme. Information on the targeting vector construction for the generation of SAT-1-KO mice has been described elsewhere (17). Genotyping of the offspring was confirmed by PCR analysis of DNA isolated from tail snips, as detailed previously (17). In the following experiments, wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice (Charles River) were used as contemporary controls to SAT-1-KO mice. All mice were housed in the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited animal facility in the Biomedical Sciences Building at the University of Florida, where they had free access to standard chow (diet 7912; Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN) and sterile drinking water. A total of 64 mice of both sexes were used in the following experiments, ranging in age from 4 to 14 mo with a mean body mass of 26.6 ± 0.9 g, n = 32, for SAT-1-KO and 28.6 ± 1.0 g, n = 32, for WT controls. All mice were euthanized by inhalation of 100% CO2 followed by exsanguination via cardiac puncture. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Transepithelial Flux Experiments

Oxalate fluxes were measured across intact isolated segments of the distal ileum, cecum, and distal colon under symmetrical short-circuit current conditions using [14C]oxalate. On another set of tissues from a separate group of mice, sulfate and Cl− fluxes were measured simultaneously across these same three intestinal segments using Na2 and H36Cl, respectively. The use of 36Cl− as a tracer for Cl− was included to determine whether SAT-1 might also contribute to intestinal Cl− fluxes, particularly since it has been reported to transport Cl− by some studies (55, 68, 90), but not all (32, 61, 91). Furthermore, because Cl− is one of the major substrates associated with intestinal oxalate transport, information on the resultant Cl− fluxes may also help to interpret the anticipated impacts on oxalate and sulfate fluxes in SAT-1-KO tissues relative to those from WT mice.

Following euthanasia and removal of the lower intestine (mid-ileum to distal colon) to ice-cold buffer, a pair of tissues was prepared from the distal ileum (a 4-cm length adjacent to the ileocecal valve), cecum, and distal colon (a 4-cm length immediately proximal to the peritoneal border representing the lower 30% of the large intestine) and mounted flat on a slider exposing a gross surface area of 0.3 cm2 (P2304; Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA), which was then secured between two halves of a modified Ussing chamber (P2300; Physiologic Instruments). Each tissue was bathed on both sides by 4 ml of buffered saline (pH 7.4), maintained at 37°C while simultaneously gassed, and stirred with 95% O2-5% CO2. These preparations were continuously voltage-clamped (VCCMC6; Physiologic Instruments).

In the experiments measuring unidirectional oxalate fluxes, ∼10 min after mounting the tissue, 0.20 µCi [14C]oxalate (specific activity 115 mCi/mmol) was added to either the mucosal (M) or serosal (S) chamber, which was then designated as the “hot” side. For the experiments simultaneously measuring sulfate and Cl− fluxes, 0.27 µCi (specific activity 1,494 Ci/mmol) and 0.09 µCi 36Cl− (specific activity 571 µCi/mmol) were added to either the M or S chamber. Approximately 15 min after the addition of isotope(s) to the “hot” side, the appearance of these tracers was detected in 1-ml samples taken from the opposing “cold” side at 15-min intervals for 45 min. Each 1-ml sample taken was immediately replaced with 1 ml of warmed buffer. In addition, transepithelial potential difference (mV) and the short-circuit current (Isc; µA) were also recorded at each 15-min sampling interval. At the beginning and end of the flux period, 50-µl samples from the hot side were collected to calculate the specific activity of each isotope. The activities of [14C]oxalate, and 36Cl− in collected samples were determined by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry (Beckman LS6500; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) with quench correction. Using a series of external standards, the validity of counting dual-labeled samples was independently established, allowing the individual activities of 35S and 36Cl to be calculated on the basis of their relative counting efficiencies after minimizing and accounting for overlap in their energy spectra.

Urine and Blood Collections.

For the collection of urine, randomly selected age and sex-matched mice (WT, n = 12; SAT-1 KO, n = 12) were placed in individual metabolic cages for a 24-h urine collection. During this time, they had access to sterile drinking water and food. Urine was collected under mineral oil (75 µl), with 20 µl of 2% (wt/vol) sodium azide as a preservative. Within 48 h following urine collection, blood was obtained by cardiac puncture after CO2 narcosis and the intestine subsequently dissected out for flux studies. For the measurement of plasma sulfate, blood was collected using a 25-gauge needle attached to a syringe that had been flushed with 5% (wt/vol) Na2-EDTA as an anticoagulant, and the blood was transferred to a microcentrifuge tube containing 20 µl of Na2-EDTA and gently mixed by inversion. The amount of EDTA used equated to ∼1.9 mg (5.1 µmol)/ml blood. The blood was immediately centrifuged at 800 g for 10 min, and the plasma was carefully aspirated before being frozen at −20°C until analysis. For the measurement of plasma oxalate, blood was drawn by cardiac puncture into heparinized syringes. Blood samples were processed immediately, with precautions taken to prevent oxalogenesis, as described previously (31), and the plasma was spiked with [14C]oxalate (0.4 µCi) to trace and correct for the cumulative losses of oxalate that take place during subsequent sample preparation.

Urine and Plasma Analysis

Urine volume was determined following retrieval of the collected urine from the metabolic cages. Immediately, an aliquot of urine (250 µl) was acidified with 3 N HCl and stored at −20°C for the later determination of oxalate using an enzyme-based assay kit (Trinity Biotech, St. Louis, MO). The remaining volume was diluted, as appropriate, with ultrapure water before storage at −20°C for the measurement of creatinine, calcium, and sulfate. Creatinine was measured in urine and plasma using a modification of the Jaffe reaction as described previously (28). Urine calcium was measured using a commercial assay kit (Pointe Scientific, Canton, MI). Sulfate in the urine and plasma was determined by turbidimetric assay, as recently described (86). For the measurement of plasma oxalate, four plasma pools were generated for WT and SAT-1-KO mice with each pool containing plasma from five mice. Oxalate was determined using a commercially available assay kit (Trinity Biotech) and a correction factor applied based on the recovery of [14C]oxalate during processing to produce a final plasma oxalate concentration.

Fecal Oxalobacter Testing

Typically, laboratory rodents do not carry the commensal oxalate-degrading gut bacteria Oxalobacter formigenes. To confirm that all animals used in this study were not colonized with Oxalobacter, samples of digesta (∼20 mg) were collected from the large intestine at the time the tissue was being prepared for flux studies and inoculated into anaerobically sealed vials of Oxalobacter growth media containing 20 mmol/l sodium oxalate (1). These vials were incubated at 37°C for ∼7 days before the media concentration of oxalate was measured by enzymatic assay (Trinity Biotech). Loss of oxalate from the media was indicative of colonization by Oxalobacter sp. This method was used to determine that all mice were Oxalobacter-free before entering this study.

Buffer Solutions and Reagents

The standard bicarbonate buffer used in the flux experiments contained the following solutes (mmol/l): 139.4 Na+, 122.2 Cl−, 21 , 5.4 K+, 2.4 , 1.2 Ca2+, 1.2 Mg2+, 0.6 , and 0.5 , pH 7.4, with 10 d-glucose included in the serosal buffer and 10 d-mannitol added to the mucosal buffer. The radioisotope [14C]oxalate was a custom preparation from ViTrax Radiochemicals (Placentia, CA), was purchased as Na2 from Perkin-Elmer (Billerica, MA), and 36Cl− was purchased as H36Cl from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ).

Calculations and Statistical Analyses

Unidirectional, transepithelial fluxes of oxalate, sulfate, and chloride in the absorptive direction, mucosal-to-serosal (), and secretory direction, serosal-to-mucosal (), were calculated from the change in activity of [14C]oxalate, , and 36Cl− on the cold side of the chamber at each 15-min sampling point, having been corrected for dilution with replacement buffer between samples, as described by Schultz and Zalusky (77). These fluxes were expressed per square centimeter of tissue per hour. The recordings of Isc (µA/cm2) and potential difference (mV) were used to calculate transepithelial conductance (GT; mS/cm2), using Ohm’s Law, and Isc was subsequently converted to univalent electrical equivalents (µeq/cm2·h). The flux of each ion, along with Isc and GT, is presented as a single average value for the 45-min experimental period. Net flux was calculated as = − from paired tissues matched on the basis of conductance with no greater than a ±15% difference in GT between pairs of distal ileum and a ±25% difference in GT between pairs of cecum and distal colon. The following data are presented as means ± SE. Significant differences between WT and SAT-1-KO mice were tested for by unpaired t-test or the equivalent nonparametric Mann-Whitney test when the data failed to meet the assumptions of approximate normality and equality of variance. The results of all tests were accepted as significant at P ≤ 0.05. SigmaPlot 13 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) was used to draw the figures and perform the statistical analysis.

RESULTS

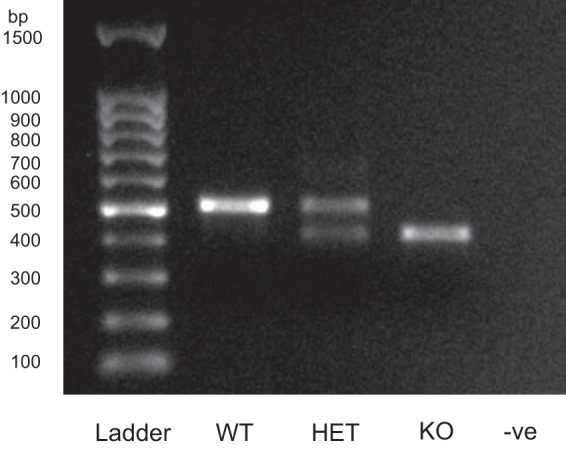

The genotypes of WT and SAT-1-KO mice were confirmed by PCR (Fig. 1), where primers amplified a ∼500-bp fragment of SAT-1 in DNA extracted from tail snips of WT and heterozygous (HET) mice, but not SAT-1-KO animals, where a ∼400-bp fragment of the neomycin resistance gene from the targeted allele was amplified. Due to the practicalities of distinguishing three β-emitting isotope tracers simultaneously ([14C]oxalate, , 36Cl−), oxalate fluxes were measured on a separate set of mice than sulfate and Cl−. Because there were no differences in the electrical characteristics between these two groups of mice, this justified combining their respective Isc and GT readings into a single value, which appears in panels D and E in Figs. 2, 3, and 4 .

Fig. 1.

A representative PCR analysis verifying the genotypes of wild-type (WT), heterozygous (HET), and sulfate anion transporter 1 (Slc26a1)-knockout (SAT-1-KO) mice with DNA extracted from tail snips, using the protocol described by Dawson et al. (17). A negative control (−ve) and molecular weight ladder (ladder) are also shown. In HET mice, the primers amplified 2 fragments, 1 from the normal SAT-1 allele (∼500 bp) and another from the targeted allele containing the neomycin resistance gene (∼400 bp). Only the SAT-1 allele fragment is present in WT mice, whereas the targeted allele was exclusively detected in homozygous KO mice.

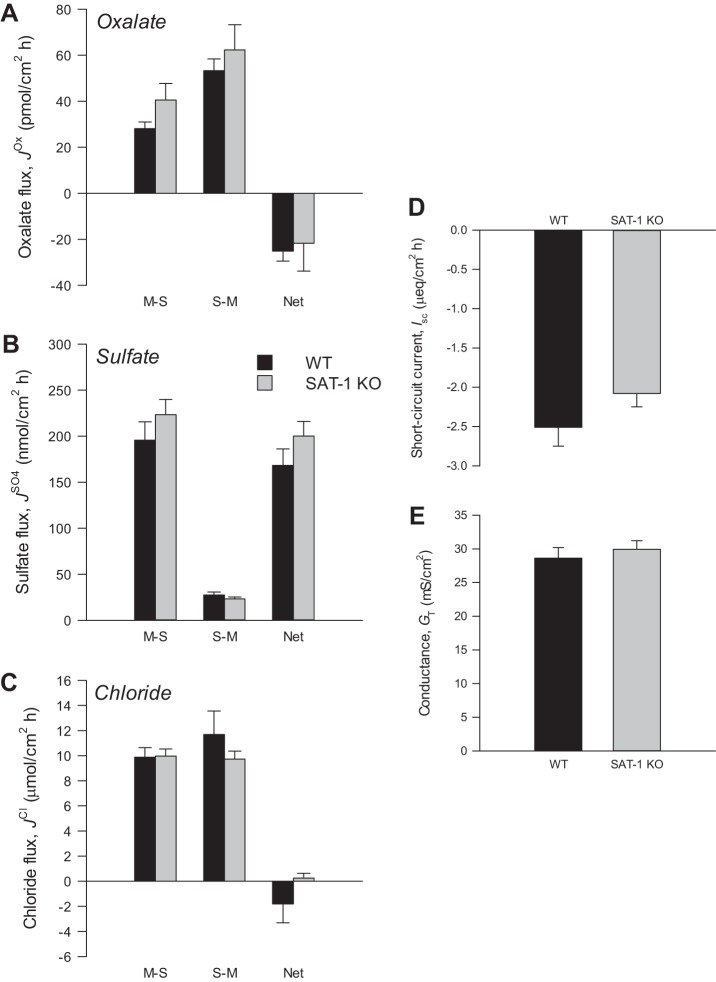

Fig. 2.

Oxalate (A), sulfate (B), and chloride (C) fluxes across the distal ileum from wild-type (WT) and sulfate anion transporter 1 (Slc26a1)-knockout (SAT-1-KO) mice under short-circuited, symmetrical conditions in vitro. Unidirectional mucosal-to-serosal (M-S), serosal-to-mucosal (S-M), and net oxalate fluxes were measured across n = 7 (WT) and n = 11 (SAT-1 KO) transepithelial conductance (GT)-matched tissue pairs. Sulfate and chloride fluxes were measured simultaneously across n = 9 (WT) and n = 7 (SAT-1-KO) GT-matched tissue pairs. D and E: short-circuit current (Isc) and GT, respectively, from all tissues combined (n = 32 WT and n = 36 SAT-1-KO). Values represent means ± SE.

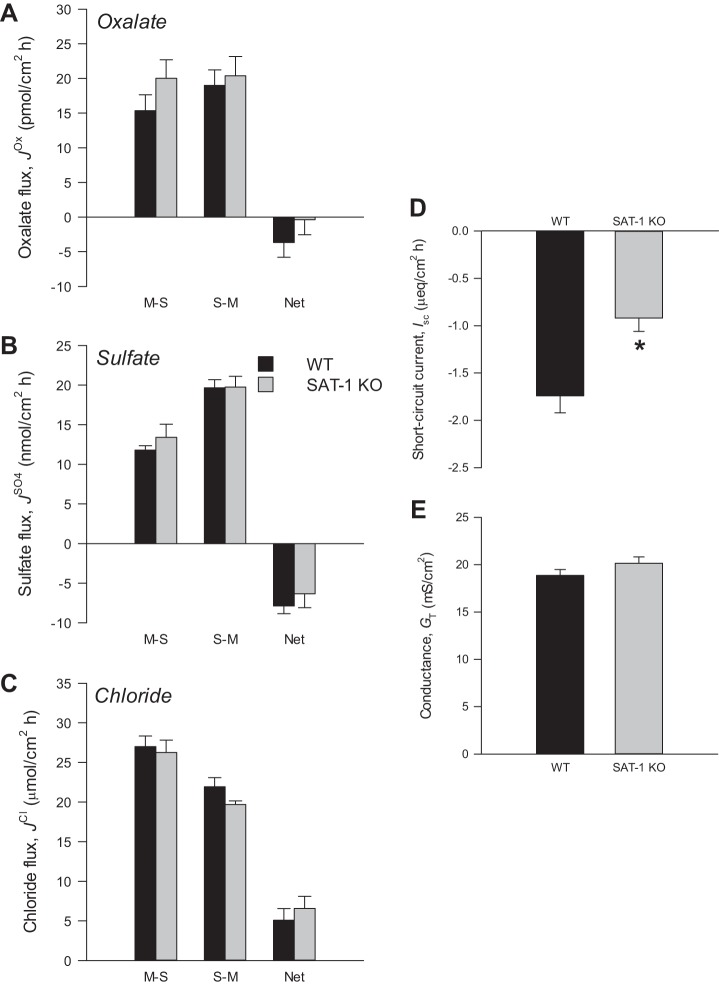

Fig. 3.

Oxalate (A), sulfate (B), and chloride (C) fluxes across the cecum from wild-type (WT) and sulfate anion transporter 1 (Slc26a1)-knockout (SAT-1-KO) mice under short-circuited, symmetrical conditions in vitro. Unidirectional mucosal-to-serosal (M-S), serosal-to-mucosal (S-M), and net oxalate fluxes were measured across n = 10 (WT) and n = 10 (SAT-1 KO) transepithelial conductance (GT)-matched tissue pairs. Sulfate and chloride fluxes were measured simultaneously across n = 10 (WT) and n = 10 (SAT-1 KO) GT-matched tissue pairs. D and E: short-circuit current (Isc) and GT, respectively, from all tissues combined (n = 40 WT and n = 40 SAT-1-KO). Values represent means ± SE. *Statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) as determined by independent t-test.

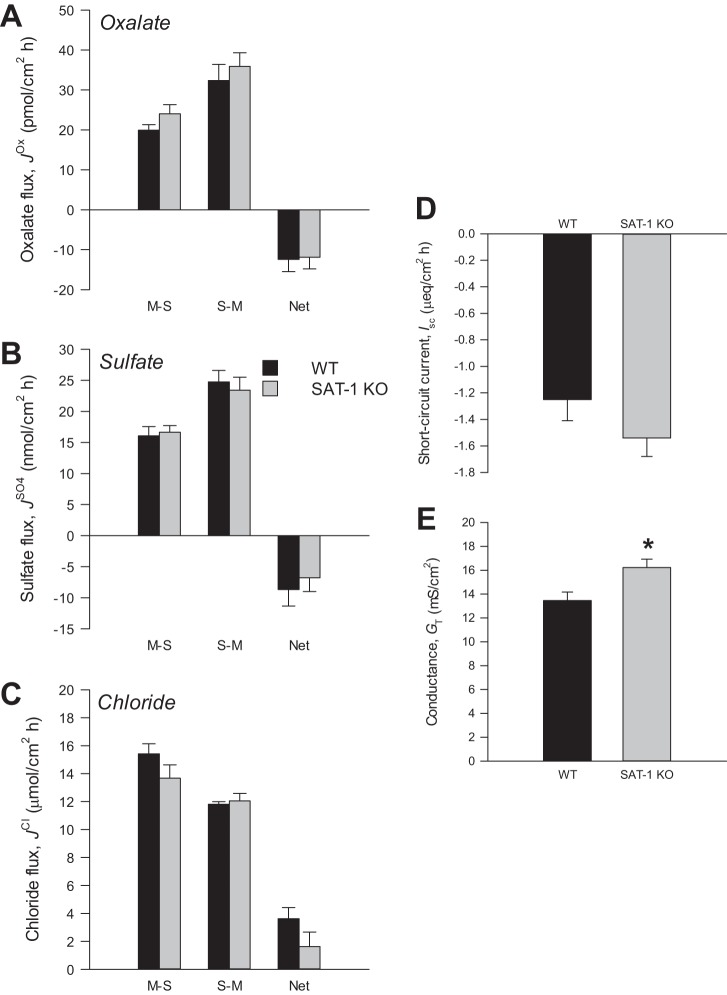

Fig. 4.

Oxalate (A), sulfate (B), and chloride (C) fluxes across the distal colon from wild-type (WT) and sulfate anion transporter 1 (Slc26a1)-knockout (SAT-1-KO) mice under short-circuited, symmetrical conditions in vitro. Unidirectional mucosal-to-serosal (M-S), serosal-to-mucosal (S-M), and net oxalate fluxes were measured across n = 9 (WT) and n = 10 (SAT-1-KO) transepithelial conductance (GT)-matched tissue pairs. Sulfate and chloride fluxes were measured simultaneously across n = 9 (WT) and n = 10 (SAT-1-KO) GT-matched tissue pairs. D and E: short-circuit current (Isc) and GT, respectfully, from all tissues combined (n = 38 WT and n = 40 SAT-1 KO). Values represent means ± SE. *Statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) as determined by independent t-test.

Distal Ileum

Figure 2 summarizes the oxalate, sulfate, and chloride fluxes, along with corresponding electrophysiological parameters, across the distal ileum. In WT mice, the unidirectional secretory flux of oxalate () was almost twofold greater than the corresponding absorptive flux (), resulting in a robust overall net secretion of oxalate (−25.2 ± 4.3 pmol/cm2·h). This pattern was strikingly similar in SAT-1-KO mice (Fig. 2A), where the absence of SAT-1 had no significant impact on oxalate fluxes across the distal ileum (, P = 0.205; , P = 0.717; , P = 0.526). There was a large net absorption of sulfate by the distal ileum in WT mice averaging 168.2 ± 17.8 nmol/cm2·h driven by a prominent absorptive flux (). Surprisingly, was undiminished by the loss of SAT-1 and almost 20% higher (Fig. 2B), although this increase was not statistically significant (P = 0.217). The distal ileum of either WT or SAT-1-KO mice did not support net Cl− absorption (Fig. 2C), where both unidirectional fluxes of Cl− were similar between genotypes (, P = 0.920; , P = 1.000). Short-circuit current (Fig. 2D) and transepithelial conductance (Fig. 2E) of the distal ileum were also very comparable between WT and SAT-1-KO mice (Isc, P = 0.360; and GT, P = 0.335).

Cecum

Figure 3A shows an extremely modest net secretion of oxalate () by the WT cecal epithelium (−3.7 ± 2.1 pmol/cm2·h), and this net transport was not significantly different from the SAT-1-KO cecum (−0.4 ± 2.2 pmol/cm2·h) (P = 0.295). Unlike the adjacent ileum, there was no overwhelming sulfate absorption by the WT or KO cecum, but instead this first portion of the large intestine maintained a small net secretion of sulfate under symmetrical, short-circuit conditions (Fig. 3B). The cecum absorbed Cl− on a net basis (Fig. 3C) and, in common with oxalate (, P = 0.186; , P = 0.701) and sulfate fluxes (, P = 0.970; , P = 0.962; , P = 0.458), Cl− fluxes were very similar between tissues from WT and SAT-1 KO mice (, P = 0.723; , P = 0.092; , P = 0.489). Interestingly, in Fig. 3D, Isc across the SAT-1 KO cecum (−0.92 ± 0.14 µeq/cm2·h) was approximately half of, and significantly different from, the current measured across the WT cecum (−1.74 ± 0.18 µeq/cm2·h) (P = <0.001). Figure 3E shows the ionic permeability of the cecum, indexed by GT, was unchanged between genotypes (P = 0.102).

Distal Colon

The distal portion of the colon supported a robust net secretion of oxalate (Fig. 4A) and sulfate (Fig. 4B), but the fluxes of either anion were not impacted by the absence of SAT-1 (, P = 0.206; , P = 0.206; , P = 0.900; , P = 0.838; , P = 0.645; , P = 0.589). On average, Fig. 4C shows that net Cl− absorption was 55% lower in the SAT-1-KO distal colon, but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.153). As shown in Fig. 4D, there were no alterations to Isc (P = 0.116), although GT (Fig. 4E) was significantly different, and this measure of ionic permeability was ∼20% higher in SAT-1-KO tissues (16.2 ± 0.7 mS/cm2) compared with WT distal colon (13.5 ± 0.7 mS/cm2) (P = <0.001).

Urine and Plasma Biochemistry

One of the most striking findings of this report is presented in Table 1 and shows that SAT-1-KO mice were not hyperoxaluric or hyperoxalemic as anticipated. Rather, the 24-h excretion of oxalate by SAT-1-KO mice was significantly lower than WT mice by 46%. Furthermore, urine sulfate and creatinine excretion were not significantly different in SAT-1-KO mice, whereas urine calcium was reduced 39% (Table 1). On average, SAT-1-KO mice were smaller in size, but this was not statistically significant; even so, these findings were unchanged after excretion rates were normalized to body mass (not shown). Whereas SAT-1-KO mice did not display the distinct hypersulfaturia expected, there was, however, a clear sulfate phenotype since plasma sulfate concentrations were considerably lower at just 0.34 mmol/l compared with 1.65 mmol/l in WT mice. Subsequent clearance calculations revealed an obvious renal wasting of sulfate by SAT-1-KO mice. The resulting sulfate-to-creatinine clearance ratios indicated that only a small fraction (∼13%) of filtered sulfate was eliminated in the urine of WT mice, and hence, the vast majority (∼87%) was reabsorbed along the nephron. This ratio was considerably skewed in the SAT-1-KO mouse, suggesting that renal sulfate reabsorption had been reduced to a mere 27%.

Table 1.

A summary of selected parameters measured in the urine and plasma collected from WT and SAT-1 KO mice

| WT | SAT-1-KO | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (males/females) | 6/6 | 6/6 | |

| Age, days | 141 ± 5 (12) | 139 ± 4 (12) | 0.664 |

| Body mass, g | 28.4 ± 1.5 (12) | 25.0 ± 1.2 (12) | 0.087 |

| Food consumed, g/24 h | 2.7 ± 0.6 (12) | 2.5 ± 0.5 (12) | 0.804 |

| Water consumed, ml/24 h | 3.70 ± 0.49 (12) | 4.04 ± 0.40 (12) | 0.589 |

| Urine volume, ml/24 h | 0.73 ± 0.10 (11) | 0.83 ± 0.16 (11) | 0.582 |

| Urine oxalate, µmol/24 h | 0.61 ± 0.09 (11) | 0.33 ± 0.08 (11)* | 0.036 |

| Urine sulfate, µmol/24 h | 37.31 ± 7.87 (9) | 30.45 ± 4.71 (9) | 0.466 |

| Urine calcium, µmol/24 h | 1.94 ± 0.24 (9) | 1.18 ± 0.16 (9)* | 0.016 |

| Urine creatinine, µmol/24 h) | 3.77 ± 0.41 (9) | 3.27 ± 0.44 (9) | 0.421 |

| Plasma oxalate, µmol/l† | 30.9 ± 7.5 (4) | 27.6 ± 4.7 (4) | 0.724 |

| Plasma sulfate, mmol/l | 1.65 ± 0.07 (12) | 0.34 ± 0.03* (12) | <0.001 |

| Plasma creatinine, µmol/l | 22.4 ± 1.8 (12) | 23.9 ± 0.9 (12) | 0.435 |

| Sulfate clearance, µl/min | 16.3 ± 3.2 (9) | 68.7 ± 10.1 (9)* | <0.001 |

| Creatinine clearance, µl/min | 132.0 ± 26.6 (9) | 93.7 ± 11.6 (9) | 0.205 |

| Clearance ratio | 0.13 ± 0.02 (9) | 0.73 ± 0.07* (9) | <0.001 |

Values are means ± SE (sample sizes in parentheses). SAT-1-KO, sulfate anion transporter 1 (Slc26a1)-knockout; WT, wild type.

Statistically significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) as determined by independent t-test.

Plasma oxalate was determined from pooled blood samples with 5 mice/pool; therefore, the associated sample size represents the no. of replicate pools analyzed.

DISCUSSION

The anion exchanger SAT-1, expressed in the intestine, liver, and kidney, has been described as a key regulator of oxalate and sulfate homeostasis, but we do not yet fully understand how. To probe the contribution of intestinal SAT-1, we compared the unidirectional transepithelial fluxes of oxalate, sulfate, and Cl− across the distal ileum, cecum, and distal colon from WT and SAT-1-KO mice in vitro. Contrary to expectation, we found SAT-1 was not involved in the transport of these anions by any segment. Also, SAT-1-KO mice were neither hyperoxaluric nor hyperoxalemic, unlike the original description of this model (17). Instead urinary oxalate excretion was reduced almost 50%. With no clear contribution from the intestine, we suggest this decrease in urine oxalate may reflect the loss of SAT-1 mediated oxalate efflux from the liver. SAT-1 KO mice also displayed a clear and profound hyposulfatemia, which could not be accounted for by changes to intestinal sulfate handling. Renal clearances indicated that lower rates of sulfate reabsorption by the SAT-1-KO proximal tubule were responsible, although there was no evidence to suggest that SAT-1 might be operating as a /oxalate exchanger in the kidney and simultaneously contributing to urinary oxalate excretion. Despite the proposed role of SAT-1 in oxalate secretion by the intestine, we have been unable to confirm this after measuring transepithelial fluxes across tissues from the SAT-1-KO mouse model. We conclude that SAT-1 is not required for oxalate, sulfate, or Cl− transport by the intestine, and its absence actually reduced urinary oxalate excretion rather than caused hyperoxaluria, hyperoxalemia, or calcium oxalate urolithiasis.

Oxalate Secretion and Sulfate Absorption by the Distal Ileum

On a net basis, the WT distal ileum supported oxalate secretion (Fig. 2A) and a robust absorption of sulfate (Fig. 2B) under symmetrical, short-circuited conditions in vitro, in agreement with our recent reports of oxalate (85, 87, 88) and sulfate (86) fluxes by this segment. Unexpectedly, SAT-1 was not required to sustain the transport of either anion, contrary to the notion of SAT-1 as a /oxalate exchanger facilitating intestinal oxalate secretion and sulfate absorption (58). This inference was based in part on finding reduced oxalate uptake by BLMVs from the SAT-1-KO intestine (17). However, we found that the 42% decrease reported by Dawson et al. (17) for the distal ileum was actually not statistically different from WT controls (T6 = 2.438, P = 0.129), and furthermore, these authors did not present any accompanying sulfate uptakes by these intestinal BLMVs. This is surprising, not least because SAT-1 is being vaunted as a /oxalate exchanger, but the ileum is the main site of sulfate absorption (3, 6, 78). The mechanism responsible is proposed to consist of the apical sodium-sulfate cotransporter NaSi (Slc13a1) operating in series with SAT-1 at the basolateral membrane (2, 58, 84). Evidence for the former comes from the near-complete abolition of Na+-dependent sulfate uptake by ileal brush-border membrane vesicles from the NaSi-KO mouse (16). However, there had been no similar appraisal for SAT-1 until now, where, much to our surprise, was maintained across the SAT-1-KO distal ileum (Fig. 2B), revealing that SAT-1 is not essential for sulfate absorption; thus another basolateral transporter(s) must be involved.

At least two different sulfate transport mechanisms have been described at the basolateral membrane of the mammalian ileum: /Cl− exchange (29, 76) and / exchange (49). Only the latter was considered an oxalate transporter (47, 49, 76), whereas ileal sulfate absorption was shown to be mediated exclusively by basolateral /Cl− exchange (54, 78, 86). Therefore, SAT-1 may represent the / exchanger in the ileum, consistent with it being characterized as such in the liver (7, 67) and kidneys (45, 52, 59). Subsequent work, however, has been unable to verify intestinal SAT-1 as a / exchanger and a contributor to oxalate transport. This was specifically tested by Ko et al. (51), who concluded oxalate secretion across the mouse duodenum did not require , carbonic anhydrase (CA), or even SAT-1, thus refuting the hypothesis that SAT-1 is working in series with apical PAT-1 to facilitate transcellular oxalate secretion (2, 4, 41, 58, 70). It is noteworthy, however, that the role of PAT-1 in the duodenum (44) and distal ileum (22) was demonstrated with sulfate-free buffers, making it unlikely that oxalate secretion by PAT-1 is tied to a sulfate transporter. In addition, for the mouse distal ileum, we found that the absence of extracellular /CO2 and inhibition of CA activity (in the presence of sulfate) did not impact oxalate (85) or sulfate fluxes (86), indicating that neither was dependent on or competing with for transport. Now, contrary to expectation, we have determined that SAT-1, regardless of mechanism, is not required for oxalate secretion or sulfate absorption by the distal ileum.

Oxalate and Sulfate Secretion by the Cecum

The WT cecum supported only a very modest net secretion of oxalate and also secreted rather than absorbed sulfate on a net basis (Fig. 3). Again, this was consistent with our recent reports on the magnitude and direction of epithelial oxalate and sulfate transport by the mouse cecum (84, 87), but the fluxes of both these anions were also entirely independent of SAT-1. Dawson et al. (17) had previously shown a significant 47% reduction in oxalate uptake by BLMVs from the SAT-1-KO cecum in vitro, and in addition, the cecal contents of these KO mice contained 4.4 µmol/g more sulfate and 5.9 µmol/g less oxalate than their WT counterparts, which has been related to the absence of SAT-1 and /oxalate exchange (17). However, neither of these observations would appear to be directly due to the cecum because there is little to no net oxalate transport and an overall net secretion of sulfate by this epithelium under symmetrical, short-circuited conditions. Furthermore, if these changes to sulfate and oxalate in the cecal contents were due to the loss of secondary active /oxalate exchange in the preceding small intestine, then it implies that these two anions must be transported at near-equivalent rates, when they are in fact orders of magnitude apart. For example, in the distal ileum, net oxalate secretion was ∼25 pmol/cm2·h (Fig. 2A), whereas net sulfate absorption was ∼170 nmol/cm2·h (Fig. 2B). Using relative apparent permeability (Papp) to compare these fluxes in terms of their prevailing extracellular concentrations, the Papp for oxalate and sulfate was 4.6 × 10−6 and 9.4 × 10−5 cm/s, respectively. Based on this ratio, for every 1 µmol of sulfate absorbed there would be a corresponding secretion of only 0.05 µmol of oxalate, thus making /oxalate exchange by the ileum an unlikely source of these reported differences within the cecal contents. The only significant change in transport we found for the cecum was a 0.82 µeq/cm2·h increase in short-circuit current (Fig. 3D). This does not appear to be directly related to SAT-1 since Isc was unchanged across the distal ileum (Fig. 2D) and distal colon (Fig. 4D), plus SAT-1 has been determined to be an electroneutral transporter (52, 90). We are unable to account for this current in terms of changes to net Cl− flux (Fig. 3C), thus implicating a possible increase in net electrogenic cation (Na+, K+) absorption and/or anion () secretion.

Oxalate and Sulfate Secretion by the Distal Colon

The distal colon also supported a net secretion of oxalate (Fig. 4A) and sulfate (Fig. 4B) for which SAT-1 was not required. With no evidence of a role for SAT-1 in any segment examined so far, this led us to consider the existence and identity of alternate transporters. Many recent works have focused on the apical transport proteins such as Slc26a6/PAT-1 (22, 25, 39, 44, 84, 86), Slc26a3/DRA (downregulated in adenoma) (26, 84, 86), Slc26a2/DTDST (diastrophic dysplasia sulfate transporter) (40), and also the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) Cl− channel (20, 46). By comparison, the basolateral membrane has been conspicuously neglected. Our present understanding is limited to some of the first functional characterizations of transepithelial oxalate and sulfate fluxes by the rabbit distal colon that were shown to occur in parallel with Cl−, possibly sharing some of the same pathways. For example, the secretory fluxes of oxalate (38) and sulfate (23) were insensitive to serosal application of the classical anion exchange inhibitors DIDS and SITS at concentrations between 1 and 50 µmol/l. Oxalate and sulfate secretion, however, could be stimulated specifically by cAMP, alongside Cl−, and this response blocked with bumetanide or furosemide, implicating the basolateral Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter NKCC1 (Slc12a2), although pretreatment with either of these loop diuretics had no impact on basal oxalate or sulfate fluxes (23, 38). The same effect of cAMP and furosemide on oxalate and Cl− secretion was also demonstrated in rabbit proximal colon where, conversely, , could also be significantly reduced by the proabsorptive hormone epinephrine (37). Notably, these early studies characterizing colonic oxalate fluxes utilized sulfate-free buffers; hence, there would seem to be no absolute requirement for sulfate to stimulate transcellular oxalate secretion, at least in the rabbit large intestine.

SAT-1 Does Not Contribute to Intestinal Chloride Transport

Thus far, we have revealed SAT-1 is not required for oxalate and sulfate transport, thus prompting the question: what is the role of SAT-1 in the intestine? One possibility is whether SAT-1 may be directly, or perhaps indirectly, contributing to Cl− transport. For instance, oxalate and sulfate are frequently transported in parallel with Cl− (23, 24, 36–38), and with at least two basolateral sulfate antiporters described in the ileum, this arrangement may allow for sulfate recycling across the membrane to potentially facilitate Cl−/ exchange (49). Furthermore, when expressed in Xenopus oocytes, SAT-1 can also transport Cl− (55, 68, 90), and the experiments with BLMVs from the SAT-1 KO mouse intestine were performed with an outwardly directed Cl− gradient (17), thus depicting SAT-1 as an oxalate/Cl− exchanger. Having simultaneously measured Cl− fluxes in these experiments we were able to evaluate, for the first time, the contribution of SAT-1 to intestinal Cl− transport. Despite these prior associations, the absence of SAT-1 did not translate to any significant changes in Cl− fluxes across the native intestinal epithelium. Nevertheless, Cl− can still be part of the exchange mechanism on SAT-1, whether as a transported substrate or allosteric modulator (32, 52, 55, 61, 73, 90, 91), despite showing that it does not contribute to bulk transepithelial Cl− fluxes.

SAT-1 mRNA and Protein Expression in the Intestine

Having been unable to determine a role for SAT-1 in the transport of either oxalate, sulfate, or Cl−, this has raised another question: Is SAT-1 even expressed by the intestine? Early studies employing Northern blot analysis reported a very narrow distribution in rats with strong expression in the liver and kidney but a complete absence from the intestine (7, 73). In human tissues, however, a more ubiquitous presence was revealed, including the small intestine and colon, and this contrasting pattern was suggested to be due to the greater sensitivity offered by RT-PCR (68). Subsequent use of RT-PCR with the mouse model showed SAT-1 was restricted to the cecum only, and not the small intestine or colon (55), whereas other studies with mice went on to find it in the ileum (22) as well as the duodenum and proximal colon (51). Although Northern analysis failed to detect SAT-1 RNA in the mouse ileum, RT-PCR did reveal a weak signal restricted to the distal portion of this segment (17). In terms of the encoded protein, Dawson et al. (17) showed that SAT-1 was present in BLMVs from the distal ileum, cecum, and proximal colon of WT mice using a rat monoclonal antibody (45). However, when this same antibody was applied as part of an immunohistochemical survey of SAT-1 expression along the rat intestine, only select intracellular organelles were stained, not the cell membrane (9). More recently, a commercial polyclonal antibody showed widespread intracellular staining of SAT-1 in the rat ileum and colon (27). We attempted to address this question of SAT-1 protein expression for ourselves but have so far failed to find a consistently reliable antibody that is selective for SAT-1 despite extensive, rigorous, and repeated testing of numerous others, both commercially available and custom-made.

The Role of SAT-1 in Oxalate and Sulfate Homeostasis

The original SAT-1-KO mouse was characterized as hyperoxaluric and hyperoxalemic, with calcium oxalate deposits detected in the renal tubules, all of which were linked to the absence of SAT-1-mediated intestinal oxalate secretion (17). We have been unable to demonstrate any such phenotype. In our hands, urinary oxalate excretion by the SAT-1-KO model was reduced by 46% (Table 1) and not connected to oxalate transport by the intestine. With prominent expression of SAT-1 at the liver and kidney, we considered whether one or both of these sites might be responsible for this hypooxaluria. For instance, the majority of oxalate eliminated in the urine is derived from liver metabolism, where SAT-1 has been localized to the sinusoidal (basolateral) membrane of hepatocytes (8, 67), with the implication that it exchanges sulfate in the blood for intracellular oxalate (9, 70, 75). Prior to the original characterization of the KO mouse model, SAT-1 protein expression by the rat liver and kidney had been correlated with increased rates of hepatic and renal /oxalate exchange and, in turn, urinary oxalate excretion (10). Consistent with this, the uptakes of oxalate and sulfate by BLMVs from SAT-1-KO mouse hepatocytes were subsequently reduced by 50 and 84%, respectively (17). If these in vitro findings translated to less oxalate output from the liver to the blood in vivo, it could conceivably explain the decrease in urinary oxalate excretion by SAT-1-KO mice shown here (Table 1). However, this would be incompatible with the hyperoxaluric and hyperoxalemic phenotype attributed to diminished intestinal oxalate secretion (17) while consuming a very low (<0.4 µmol/g) oxalate chow (58).

In the kidney, SAT-1 is hypothesized to be a basolateral / (oxalate) exchanger, where it functions in the reabsorption of filtered sulfate from the proximal tubule and also represents a potential pathway for renal oxalate secretion (9, 45, 52, 69, 70). If correct, then the absence of SAT-1 from the kidney might explain not only the hyposulfatemia but also the associated hypooxaluria exhibited by SAT-1-KO mice (Table 1). The elevated sulfate clearance and sulfate-to-creatinine clearance ratio for KO mice, relative to their WT counterparts, was consistent with SAT-1 being critical to a large fraction of renal tubular sulfate reabsorption. Dawson et al. (17) reached a similar conclusion to account for the hyposulfatemia and renal sulfate wasting of their SAT-1-KO model, which was corroborated by near-complete abolition (95% decrease) of sulfate uptake by BLMVs from the kidney. A significant role for SAT-1 in renal oxalate handling cannot be discounted since oxalate transport by these same BLMVs was also substantially reduced by 87%, but it was difficult to reconcile this with the combined hyperoxaluria and hyperoxalemia exhibited by SAT-1-KO mice (17). Table 1 shows that there were no corresponding changes to plasma oxalate in the absence of SAT-1. These values were at least twofold higher than previously reported for this model (17). Because we took appropriate steps to prevent oxalogenesis, and with equivalence between the enzymatic and ion chromatography approaches to measuring oxalate (31), these divergent values may reflect the broad distribution of plasma/serum oxalate values for laboratory rodents, which span a two- to threefold range (22, 26, 31, 39). However, losses of oxalate during sample preparation can be considerable and highly variable, leading to substantial underestimates of the true oxalate concentration (31). We used [14C]oxalate to trace and correct for these cumulative losses, but it is not clear whether Dawson et al. (17) also did. We did not find any correlation between plasma sulfate and urinary oxalate excretion in WT mice (ρ = −0.025, P = 0.942, n = 11) to suggest that renal SAT-1 was a major determinant of oxalate in the blood and urine via /oxalate exchange. Since plasma oxalate was measured on pooled blood samples, it was not possible to calculate individual clearance ratios, as we have done for sulfate, although based on the mean values presented in Table 1, there was no difference in the oxalate-to-creatinine clearance ratios between WT and SAT-1-KO mice (0.10 and 0.09, respectively), which indicate high rates of net oxalate reabsorption taking place along the nephron.

In addition to oxalate, we also recorded a significant 39% reduction in urinary calcium excretion by SAT-1-KO mice (Table 1). The accumulation of circulating sulfate, for example, during chronic renal failure or following an infusion of sulfate (as Na2SO4 or MgSO4), can induce hypercalciuria and even hypocalcemia (13). Therefore, whether a significant decline in plasma sulfate might have the opposite effect and promote hypocalciuria, as exhibited by the SAT-1-KO mouse, is intriguing. Indeed, a missense variant in the human SLC26A1 gene has recently been associated with higher total serum calcium and lower bone mineral density (79). However, previous studies with the profoundly hyposulfatemic NaSi-KO (16) and SAT-1-KO (17) mouse models did not detect any significant changes to the calcium-to-creatinine ratios in the urine or (total) plasma calcium. Additionally, whereas sulfate has a role in cartilage and bone development (15, 53), femur and tibia samples from NaSi-KO mice did not display any respective changes in length or histological characteristics (16). Furthermore, if sulfate levels were presumably elevated within the lumen of the SAT-1-KO renal tubule due to its impaired reabsorption, this would be predicted to inhibit rather than enhance calcium reabsorption based on perfusions of the rat nephron (66).

Conflicting Phenotypical Characteristics of the SAT-1-KO Mouse Model

We have shown a considerable divergence in oxalate handling by the SAT-1-KO mouse compared with the original report by Dawson et al. (17). The underlying reasons are not clear, but alongside the points raised in the above discussion, there are some additional key differences between these two models and studies.

Genetic background.

The original SAT-1-KO mouse was studied on a mixed 129/JSv × CD1 background (17) before being transferred onto a C57BL background (51) and maintained as such for the present work. It is notable that SAT-1 was ruled out as a contributor to duodenal oxalate secretion, while on this latter background (51), consistent with our findings for the more distal segments of the intestine. The use of different strains was offered as a potential explanation for the differing phenotypes of two independently developed PAT-1-KO mice (35). For instance, one model, bred onto a 129S6/SvEv background, possessed significant hyperoxaluria and hyperoxalemia, as well as hypercalciuria, and went on to develop calcium oxalate urolithiasis (44), whereas on a C57BL background the PAT-1 KO mouse was hyperoxaluric only (22). Similarly, different rat strains (14, 56, 57) and even mouse substrains (80) have been shown to vary in their susceptibility to renal crystal formation, while electrogenic anion secretion by the mouse large intestine can be strain dependent (19). Therefore, it is not unreasonable that the contribution of SAT-1 to oxalate homeostasis might be modified by genetic background, similar to what was seen with CFTR-KO mice, where the severity of disease and survival can be profoundly influenced by strain (71).

Incomplete urine collections.

The hyperoxaluria ascribed to the SAT-1-KO mouse was based on the concentration of oxalate in a single spot sample of urine expressed as a molar ratio of creatinine (17). Although spot samples might be more straightforward, and sometimes necessary, 24-h collections are the recommended standard for defining overall oxaluria (63). This is because they are less susceptible to episodic variations in excretion related to factors such as time of day and food intake (42, 50, 81) that can potentially skew the interpretation of spot samples. Indeed, comparisons of these two measures have demonstrated that the oxalate-to-creatinine ratio in spot urine samples cannot directly substitute for a 24-h collection as part of a metabolic evaluation (11, 43, 62).

Sex differences.

In the present study we utilized both sexes, consistent with previous mouse studies from this laboratory, including characterizations of PAT-1-KO and DRA-KO models (22, 26, 84, 86), whereas Dawson et al. (17) focused exclusively on male mice. To date, we have not encountered any sex differences in oxalate transport by the mouse intestine (88). However, in rats, SAT-1 protein expression in the liver and kidney was greater in males than in females, alongside corresponding rates of /oxalate exchange by membrane vesicles, and this was linked to the higher rates of urinary oxalate excretion and propensity for calcium oxalate urolithiasis typically exhibited by males (10). Interestingly, SAT-1 protein in the liver (but not the kidney) of male rats was also negatively regulated by female sex hormones (10). Furthermore, although there was no relationship between renal SAT-1 expression patterns and ethylene glycol-induced hyperoxaluria in male rats (8, 21), this was not the case for females, where increased SAT-1 protein at the liver and kidney was actually considered beneficial for avoiding hyperoxaluria and mitigating the risk for urolithiasis (8).

Perspectives and Summary

The original report by Dawson et al. (17) on the SAT-1-KO mouse phenotype generated not only enthusiasm about SAT-1 as an intestinal oxalate transporter and its critical role in oxalate homeostasis but also consideration of the human SLC26A1 gene as a risk factor and potential therapeutic target for nephrolithiasis (30, 58, 60, 65, 74). A number of studies so far have probed these possibilities without success. From a small survey of recurrent, idiopathic calcium oxalate stone-forming patients, at least two single-nucleotide variants of the SAT-1 gene were identified and predicted to impact the stability of the resulting protein (18). However, when functionally tested in Xenopus oocytes in vitro, these two missense mutations (either individually or in combination) did not affect oxalate transport, suggesting that they were not an etiological factor (90). The functional evaluation of two rare, compound, heterozygous variants of the SLC26A1 gene also indicated that SAT-1 was not a contributing factor to disease pathology in a patient with renal Fanconi syndrome (90). A further study has since attempted to link SAT-1 to nephrolithiasis in humans after detecting several mutations of this gene in two individual calcium oxalate stone formers (27). When these variants were recreated with a mouse SAT-1 clone and transfected into human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells, each demonstrated significant reductions in / exchange. The authors used this to definitively claim “that mutations in SLC26A1 cause an autosomal-recessive form of calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis” (27), even though they did not actually measure oxalate transport by these variants. In summary, oxalate and sulfate transport by the mouse intestine were not directly dependent on SAT-1 and did not contribute to the overall homeostasis of these anions, as originally suggested. Aside from a distinct sulfate phenotype, SAT-1-KO mice were neither hyperoxaluric nor hyperoxalemic, contrary to the initial characterization of this model. In conclusion, we found no evidence to support the hypothesis that intestinal SAT-1 contributes to oxalate and sulfate homeostasis.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-088892 and DK-108755 to M. Hatch.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M.W. and M.H. conception and design of research; J.M.W., C.E.S., and M.H. performed experiments; J.M.W. and M.H. analyzed data; J.M.W., C.E.S., and M.H. interpreted results of experiments; J.M.W. prepared figures; J.M.W. drafted manuscript; J.M.W., C.E.S., and M.H. edited and revised manuscript; J.M.W., C.E.S., and M.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maureen Mohan, Hope Fischer, Una Sijercic, Sammie Chavez, and Alexandra Hernandez for technical assistance and animal husbandry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison MJ, Dawson KA, Mayberry WR, Foss JG. Oxalobacter formigenes gen. nov., sp. nov.: oxalate-degrading anaerobes that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Microbiol 141: 1–7, 1985. doi: 10.1007/BF00446731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alper SL, Sharma AK. The SLC26 gene family of anion transporters and channels. Mol Aspects Med 34: 494–515, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anast C, Kennedy R, Volk G, Adamson L. In vitro studies of sulfate transport by small intestine of rat rabbit and hamster. J Lab Clin Med 65: 903–911, 1965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronson PS. Role of SLC26A6-mediated Cl−-oxalate exchange in renal physiology and pathophysiology. J Nephrol 23, Suppl 16: S158–S164, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asplin JR. Hyperoxaluric calcium nephrolithiasis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 31: 927–949, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8529(02)00030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batt ER. Sulfate accumulation by mouse intestine: influence of age and other factors. Am J Physiol 217: 1101–1104, 1969. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.217.4.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bissig M, Hagenbuch B, Stieger B, Koller T, Meier PJ. Functional expression cloning of the canalicular sulfate transport system of rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 269: 3017–3021, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breljak D, Brzica H, Vrhovac I, Micek V, Karaica D, Ljubojević M, Sekovanić A, Jurasović J, Rašić D, Peraica M, Lovrić M, Schnedler N, Henjakovic M, Wegner W, Burckhardt G, Burckhardt BC, Sabolić I. In female rats, ethylene glycol treatment elevates protein expression of hepatic and renal oxalate transporter sat-1 (Slc26a1) without inducing hyperoxaluria. Croat Med J 56: 447–459, 2015. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2015.56.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brzica H, Breljak D, Burckhardt BC, Burckhardt G, Sabolić I. Oxalate: from the environment to kidney stones. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol 64: 609–630, 2013. doi: 10.2478/10004-1254-64-2013-2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brzica H, Breljak D, Krick W, Lovrić M, Burckhardt G, Burckhardt BC, Sabolić I. The liver and kidney expression of sulfate anion transporter sat-1 in rats exhibits male-dominant gender differences. Pflugers Arch 457: 1381–1392, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clifford-Mobley O, Tims C, Rumsby G. The comparability of oxalate excretion and oxalate:creatinine ratio in the investigation of primary hyperoxaluria: review of data from a referral centre. Ann Clin Biochem 52: 113–121, 2015. doi: 10.1177/0004563214529937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coe FL, Evan A, Worcester E. Kidney stone disease. J Clin Invest 115: 2598–2608, 2005. doi: 10.1172/JCI26662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole DEC, Evrovski J. The clinical chemistry of inorganic sulfate. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 37: 299–344, 2000. doi: 10.1080/10408360091174231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruzan G, Corley RA, Hard GC, Mertens JJ, McMartin KE, Snellings WM, Gingell R, Deyo JA. Subchronic toxicity of ethylene glycol in Wistar and F-344 rats related to metabolism and clearance of metabolites. Toxicol Sci 81: 502–511, 2004. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson PA. Sulfate in fetal development. Semin Cell Dev Biol 22: 653–659, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson PA, Beck L, Markovich D. Hyposulfatemia, growth retardation, reduced fertility, and seizures in mice lacking a functional NaSi-1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 13704–13709, 2003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2231298100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson PA, Russell CS, Lee S, McLeay SC, van Dongen JM, Cowley DM, Clarke LA, Markovich D. Urolithiasis and hepatotoxicity are linked to the anion transporter Sat1 in mice. J Clin Invest 120: 706–712, 2010. doi: 10.1172/JCI31474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawson PA, Sim P, Mudge DW, Cowley D. Human SLC26A1 gene variants: a pilot study. Sci World J 2013: 1–7, 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/541710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flores CA, Cid LP, Sepúlveda FV. Strain-dependent differences in electrogenic secretion of electrolytes across mouse colon epithelium. Exp Physiol 95: 686–698, 2010. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.051102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freel RW, Hatch M. Enteric oxalate secretion is not directly mediated by the human CFTR chloride channel. Urol Res 36: 127–131, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00240-008-0142-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freel RW, Hatch M. Hyperoxaluric rats do not exhibit alterations in renal expression patterns of Slc26a1 (SAT1) mRNA or protein. Urol Res 40: 647–654, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00240-012-0480-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freel RW, Hatch M, Green M, Soleimani M. Ileal oxalate absorption and urinary oxalate excretion are enhanced in Slc26a6 null mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G719–G728, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00481.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freel RW, Hatch M, Vaziri ND. cAMP-dependent sulfate secretion by the rabbit distal colon: a comparison with electrogenic chloride secretion. Am J Physiol 273: C148–C160, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.1.C148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freel RW, Hatch M, Vaziri ND. Conductive pathways for chloride and oxalate in rabbit ileal brush-border membrane vesicles. Am J Physiol 275: C748–C757, 1998. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.3.C748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freel RW, Morozumi M, Hatch M. Parsing apical oxalate exchange in Caco-2BBe1 monolayers: siRNA knockdown of SLC26A6 reveals the role and properties of PAT-1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G918–G929, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00251.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freel RW, Whittamore JM, Hatch M. Transcellular oxalate and Cl− absorption in mouse intestine is mediated by the DRA anion exchanger Slc26a3, and DRA deletion decreases urinary oxalate. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 305: G520–G527, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00167.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gee HY, Jun I, Braun DA, Lawson JA, Halbritter J, Shril S, Nelson CP, Tan W, Stein D, Wassner AJ, Ferguson MA, Gucev Z, Sayer JA, Milosevic D, Baum M, Tasic V, Lee MG, Hildebrandt F. Mutations in SLC26A1 cause nephrolithiasis. Am J Hum Genet 98: 1228–1234, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green ML, Hatch M, Freel RW. Ethylene glycol induces hyperoxaluria without metabolic acidosis in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F536–F543, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00025.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagenbuch B, Stange G, Murer H. Transport of sulphate in rat jejunal and rat proximal tubular basolateral membrane vesicles. Pflugers Arch 405: 202–208, 1985. doi: 10.1007/BF00582561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halbritter J, Seidel A, Müller L, Schönauer R, Hoppe B. Update on hereditary kidney stone disease and introduction of a new clinical patient registry in Germany. Front Pediatr 6: 47, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris AH, Freel RW, Hatch M. Serum oxalate in human beings and rats as determined with the use of ion chromatography. J Lab Clin Med 144: 45–52, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasegawa K, Kato A, Watanabe T, Takagi W, Romero MF, Bell JD, Toop T, Donald JA, Hyodo S. Sulfate transporters involved in sulfate secretion in the kidney are localized in the renal proximal tubule II of the elephant fish (Callorhinchus milii). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 311: R66–R78, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00477.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatch M. Intestinal adaptations in chronic kidney disease and the influence of gastric bypass surgery. Exp Physiol 99: 1163–1167, 2014. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2014.078782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatch M, Freel RW. Intestinal transport of an obdurate anion: oxalate. Urol Res 33: 1–16, 2005. doi: 10.1007/s00240-004-0445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hatch M, Freel RW. The roles and mechanisms of intestinal oxalate transport in oxalate homeostasis. Semin Nephrol 28: 143–151, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hatch M, Freel RW, Goldner AM, Earnest DL. Oxalate and chloride absorption by the rabbit colon: sensitivity to metabolic and anion transport inhibitors. Gut 25: 232–237, 1984. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.3.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatch M, Freel RW, Vaziri ND. Characteristics of the transport of oxalate and other ions across rabbit proximal colon. Pflugers Arch 423: 206–212, 1993. doi: 10.1007/BF00374396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatch M, Freel RW, Vaziri ND. Mechanisms of oxalate absorption and secretion across the rabbit distal colon. Pflugers Arch 426: 101–109, 1994. doi: 10.1007/BF00374677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatch M, Gjymishka A, Salido EC, Allison MJ, Freel RW. Enteric oxalate elimination is induced and oxalate is normalized in a mouse model of primary hyperoxaluria following intestinal colonization with Oxalobacter. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300: G461–G469, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00434.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heneghan JF, Akhavein A, Salas MJ, Shmukler BE, Karniski LP, Vandorpe DH, Alper SL. Regulated transport of sulfate and oxalate by SLC26A2/DTDST. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 298: C1363–C1375, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00004.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heneghan JF, Alper SL. This, too, shall pass—like a kidney stone: a possible path to prophylaxis of nephrolithiasis? Focus on “Cholinergic signaling inhibits oxalate transport by human intestinal T84 cells”. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 302: C18–C20, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00389.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmes RP, Ambrosius WT, Assimos DG. Dietary oxalate loads and renal oxalate handling. J Urol 174: 943–947, 2005. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000169476.85935.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong YH, Dublin N, Razack AH, Mohd MA, Husain R. Twenty-four hour and spot urine metabolic evaluations: correlations versus agreements. Urology 75: 1294–1298, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang Z, Asplin JR, Evan AP, Rajendran VM, Velazquez H, Nottoli TP, Binder HJ, Aronson PS. Calcium oxalate urolithiasis in mice lacking anion transporter Slc26a6. Nat Genet 38: 474–478, 2006. doi: 10.1038/ng1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karniski LP, Lötscher M, Fucentese M, Hilfiker H, Biber J, Murer H. Immunolocalization of sat-1 sulfate/oxalate/bicarbonate anion exchanger in the rat kidney. Am J Physiol 275: F79–F87, 1998. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.1.F79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knauf F, Thomson RB, Heneghan JF, Jiang Z, Adebamiro A, Thomson CL, Barone C, Asplin JR, Egan ME, Alper SL, Aronson PS. Loss of Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator impairs intestinal oxalate secretion. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 242–249, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016030279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knickelbein RG, Aronson PS, Dobbins JW. Oxalate transport by anion exchange across rabbit ileal brush border. J Clin Invest 77: 170–175, 1986. doi: 10.1172/JCI112272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knickelbein RG, Aronson PS, Dobbins JW. Substrate and inhibitor specificity of anion exchangers on the brush border membrane of rabbit ileum. J Membr Biol 88: 199–204, 1985. doi: 10.1007/BF01868433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knickelbein RG, Dobbins JW. Sulfate and oxalate exchange for bicarbonate across the basolateral membrane of rabbit ileum. Am J Physiol 259: G807–G813, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.5.G807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knight J, Holmes RP, Assimos DG. Intestinal and renal handling of oxalate loads in normal individuals and stone formers. Urol Res 35: 111–117, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00240-007-0090-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ko N, Knauf F, Jiang Z, Markovich D, Aronson PS. Sat1 is dispensable for active oxalate secretion in mouse duodenum. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C52–C57, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00385.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krick W, Schnedler N, Burckhardt G, Burckhardt BC. Ability of sat-1 to transport sulfate, bicarbonate, or oxalate under physiological conditions. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F145–F154, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90401.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Langford R, Hurrion E, Dawson PA. Genetics and pathophysiology of mammalian sulfate biology. J Genet Genomics 44: 7–20, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Langridge-Smith JE, Field M. Sulfate transport in rabbit ileum: characterization of the serosal border anion exchange process. J Membr Biol 63: 207–214, 1981. doi: 10.1007/BF01870982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee A, Beck L, Markovich D. The mouse sulfate anion transporter gene Sat1 (Slc26a1): cloning, tissue distribution, gene structure, functional characterization, and transcriptional regulation thyroid hormone. DNA Cell Biol 22: 19–31, 2003. doi: 10.1089/104454903321112460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y, McLaren MC, McMartin KE. Involvement of urinary proteins in the rat strain difference in sensitivity to ethylene glycol-induced renal toxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F605–F615, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00419.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y, McMartin KE. Strain differences in urinary factors that promote calcium oxalate crystal formation in the kidneys of ethylene glycol-treated rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F1080–F1087, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90727.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Markovich D. Slc13a1 and Slc26a1 KO models reveal physiological roles of anion transporters. Physiology (Bethesda) 27: 7–14, 2012. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Markovich D, Bissig M, Sorribas V, Hagenbuch B, Meier PJ, Murer H. Expression of rat renal sulfate transport systems in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Functional characterization and molecular identification. J Biol Chem 269: 3022–3026, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mohebbi N, Ferraro PM, Gambaro G, Unwin R. Tubular and genetic disorders associated with kidney stones. Urolithiasis 45: 127–137, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00240-016-0945-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakada T, Zandi-Nejad K, Kurita Y, Kudo H, Broumand V, Kwon CY, Mercado A, Mount DB, Hirose S. Roles of Slc13a1 and Slc26a1 sulfate transporters of eel kidney in sulfate homeostasis and osmoregulation in freshwater. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R575–R585, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00725.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ogawa Y, Yonou H, Hokama S, Oda M, Morozumi M, Sugaya K. Urinary saturation and risk factors for calcium oxalate stone disease based on spot and 24-hour urine specimens. Front Biosci 8: a167–a176, 2003. doi: 10.2741/1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pearle MS, Goldfarb DS, Assimos DG, Curhan G, Denu-Ciocca CJ, Matlaga BR, Monga M, Penniston KL, Preminger GM, Turk TM, White JR; American Urological Assocation . Medical management of kidney stones: AUA guideline. J Urol 192: 316–324, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Petrovic S, Wang Z, Ma L, Seidler U, Forte JG, Shull GE, Soleimani M. Colocalization of the apical Cl−/HCO3− exchanger PAT1 and gastric H-K-ATPase in stomach parietal cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 283: G1207–G1216, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00137.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Policastro LJ, Saggi SJ, Goldfarb DS, Weiss JP. Personalized intervention in monogenic stone formers. J Urol 199: 623–632, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.09.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Quamme GA. Effects of intraluminal sulfate on electrolyte transfers along the perfused rat nephron. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 59: 122–130, 1981. doi: 10.1139/y81-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Quondamatteo F, Krick W, Hagos Y, Krüger MH, Neubauer-Saile K, Herken R, Ramadori G, Burckhardt G, Burckhardt BC. Localization of the sulfate/anion exchanger in the rat liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G1075–G1081, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00492.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Regeer RR, Lee A, Markovich D. Characterization of the human sulfate anion transporter (hsat-1) protein and gene (SAT1; SLC26A1). DNA Cell Biol 22: 107–117, 2003. doi: 10.1089/104454903321515913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Regeer RR, Markovich D. A dileucine motif targets the sulfate anion transporter sat-1 to the basolateral membrane in renal cell lines. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C365–C372, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00502.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Robijn S, Hoppe B, Vervaet BA, D’Haese PC, Verhulst A. Hyperoxaluria: a gut-kidney axis? Kidney Int 80: 1146–1158, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rozmahe R, Wilschanski M, Matin A, Plyte S, Oliver M, Auerbach W, Moore A, Forstner J, Durie P, Nadeau J, Bear C, Tsui LC. Modulation of disease severity in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator deficient mice by a secondary genetic factor. Nat Genet 12: 280–287, 1996. [Erratum in: Nat Genet 13: 129, 1996.] 10.1038/ng0396-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sakhaee K, Maalouf NM, Sinnott B. Clinical review. Kidney stones 2012: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: 1847–1860, 2012. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Satoh H, Susaki M, Shukunami C, Iyama K, Negoro T, Hiraki Y. Functional analysis of diastrophic dysplasia sulfate transporter. Its involvement in growth regulation of chondrocytes mediated by sulfated proteoglycans. J Biol Chem 273: 12307–12315, 1998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sayer JA. Progress in understanding the genetics of calcium-containing nephrolithiasis. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 748–759, 2017. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016050576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schnedler N, Burckhardt G, Burckhardt BC. Glyoxylate is a substrate of the sulfate-oxalate exchanger, sat-1, and increases its expression in HepG2 cells. J Hepatol 54: 513–520, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schron CM, Knickelbein RG, Aronson PS, Dobbins JW. Evidence for carrier-mediated Cl-SO4 exchange in rabbit ileal basolateral membrane vesicles. Am J Physiol 253: G404–G410, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schultz SG, Zalusky R. Ion transport in isolated rabbit ileum I. Short-circuit current and Na fluxes. J Gen Physiol 47: 567–584, 1964. doi: 10.1085/jgp.47.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smith PL, Orellana SA, Field M. Active sulfate absorption in rabbit ileum: dependence on sodium and chloride and effects of agents that alter chloride transport. J Membr Biol 63: 199–206, 1981. doi: 10.1007/BF01870981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tise CG, Perry JA, Anforth LE, Pavlovich MA, Backman JD, Ryan KA, Lewis JP, O’Connell JR, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Shuldiner AR. From genotype to phenotype: Nonsense variants in SLC13A1 are associated with decreased serum sulfate and increased serum aminotransferases. G3 (Bethesda) 6: 2909–2918, 2016. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.032979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Usami M, Okada A, Taguchi K, Hamamoto S, Kohri K, Yasui T. Genetic differences in C57BL/6 mouse substrains affect kidney crystal deposition. Urolithiasis 46: 515–522, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00240-018-1040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vahlensieck EW, Bach D, Hesse A. Circadian rhythm of lithogenic substances in the urine. Urol Res 10: 195–203, 1982. doi: 10.1007/BF00255944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang Z, Petrovic S, Mann E, Soleimani M. Identification of an apical Cl(−)/HCO3(−) exchanger in the small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 282: G573–G579, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00338.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang Z, Wang T, Petrovic S, Tuo B, Riederer B, Barone S, Lorenz JN, Seidler U, Aronson PS, Soleimani M. Renal and intestinal transport defects in Slc26a6-null mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C957–C965, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00505.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Whittamore JM, Freel RW, Hatch M. Sulfate secretion and chloride absorption are mediated by the anion exchanger DRA (Slc26a3) in the mouse cecum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 305: G172–G184, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00084.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Whittamore JM, Frost SC, Hatch M. Effects of acid-base variables and the role of carbonic anhydrase on oxalate secretion by the mouse intestine in vitro. Physiol Rep 3: e12282, 2015. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Whittamore JM, Hatch M. Loss of the anion exchanger DRA (Slc26a3), or PAT1 (Slc26a6), alters sulfate transport by the distal ileum and overall sulfate homeostasis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 313: G166–G179, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00079.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Whittamore JM, Hatch M. Oxalate transport by the mouse intestine in vitro is not affected by chronic challenges to systemic acid-base homeostasis. Urolithiasis. In press. doi: 10.1007/s00240-018-1067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Whittamore JM, Hatch M. The role of intestinal oxalate transport in hyperoxaluria and the formation of kidney stones in animals and man. Urolithiasis 45: 89–108, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00240-016-0952-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Worcester EM. Stones from bowel disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 31: 979–999, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8529(02)00035-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu M, Heneghan JF, Vandorpe DH, Escobar LI, Wu BL, Alper SL. Extracellular Cl(-) regulates human SO4 (2−)/anion exchanger SLC26A1 by altering pH sensitivity of anion transport. Pflugers Arch 468: 1311–1332, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00424-016-1823-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xie Q, Welch R, Mercado A, Romero MF, Mount DB. Molecular characterization of the murine Slc26a6 anion exchanger: functional comparison with Slc26a1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F826–F838, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00079.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]