Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa secretes outer-membrane vesicles (OMVs) that fuse with cholesterol-rich lipid rafts in the apical membrane of airway epithelial cells and decrease wt-CFTR Cl− secretion. Herein, we tested the hypothesis that a reduction of the cholesterol content of CF human airway epithelial cells by cyclodextrins reduces the inhibitory effect of OMVs on VX-809 (lumacaftor)-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion. Primary CF bronchial epithelial cells and CFBE cells were treated with vehicle, hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD), or methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), and the effects of OMVs secreted by P. aeruginosa on VX-809 stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion were measured in Ussing chambers. Neither HPβCD nor MβCD were cytotoxic, and neither altered Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion. Both cyclodextrins reduced OMV inhibition of VX-809-stimulated Phe508del-CFTR Cl− secretion when added to the apical side of CF monolayers. Both cyclodextrins also reduced the ability of P. aeruginosa to form biofilms and suppressed planktonic growth of P. aeruginosa. Our data suggest that HPβCD, which is in clinical trials for Niemann-Pick Type C disease, and MβCD, which has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in solubilizing lipophilic drugs, may enhance the clinical efficacy of VX-809 in CF patients when added to the apical side of airway epithelial cells, and reduce planktonic growth and biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa. Both effects would be beneficial to CF patients.

Keywords: CFTR, cyclodextrin, cystic fibrosis, lumacaftor, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide ~80,000 people have cystic fibrosis (CF), and ~80% die from respiratory failure due to chronic bacterial infections of the lungs, primarily with the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa (31). In 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Orkambi, a combination of VX-809 (lumacaftor) and VX-770 (ivacaftor), for patients homozygous for the Phe508del mutation in CFTR (37, 38, 41). Although Orkambi increases lung function and significantly decreases pulmonary exacerbations, it does not significantly reduce the lung burden of P. aeruginosa (41). Therefore, new approaches are needed to reduce chronic P. aeruginosa lung infections in CF.

P. aeruginosa secretes outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) that fuse with cholesterol-rich lipid rafts in the apical plasma membrane of airway epithelial cells and deliver many virulence factors, including Cif, into the cytoplasm, where it reduces wt-CFTR Cl− secretion (3, 6, 7, 31, 32). Cif enhances the ubiquitination and lysosomal degradation of wt-CFTR, thereby reducing CFTR Cl− secretion, mucociliary transport by airway epithelial cells, and the ability of mouse lungs to clear P. aeruginosa (18, 31). P. aeruginosa also eliminates the stimulatory effect of VX-809 on Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion (32, 36). Filipin III, which disrupts lipid rafts, blocks OMV fusion with airway epithelial cells and eliminates the ability of OMVs to reduce apical plasma membrane wt-CFTR (6). Although filipin III is unlikely to be used clinically due to its cytotoxicity, noncytotoxic hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) also disrupt lipid rafts by reducing the cholesterol content of the plasma membrane (9, 10). HPβCD is in clinical trials for Niemann-Pick Type C disease (NCT02534844) (9, 10), and MβCD has been approved by the FDA for use in solubilizing lipophilic drugs (10). In addition, studies have demonstrated that cyclodextrins block internalization of P. aeruginosa into mouse lung epithelial cells in vivo (16), block the ability of OMVs to fuse with A549 cells (4), reduce the internalization of temperature-rescued Phe508del CFTR in primary human bronchial epithelial cells (8), and inhibit quorum sensing, a key regulator of antibiotic-resistant biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa (24). OMVs have been shown to stimulate the innate immune response by increasing cytokine secretion by airway epithelial cells (12).

Cholesterol metabolism is defective in CF (15). CF cells accumulate cholesterol but plasma levels of cholesterol are reduced (15). Cellular accumulation of cholesterol in CF causes defects in intracellular protein trafficking, increases inflammation, and reduces airway surfactant surface tension that may lead to alveolar collapse (9). In addition, cholesterol levels are elevated in CF bronchoalveolar fluid (BALF), which reduces surfactant surface tension and film stability (17). A reduction in BALF cholesterol with MβCD restores surface tension (17). Taken together, these observations suggest that a reduction in cholesterol in BALF and airway epithelial cells may have numerous beneficial effects. Accordingly, herein, we conducted studies 1) to determine whether P. aeruginosa inhibition of VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion is mediated by OMVs, 2) to test the hypothesis that reduction of the cholesterol content of airway epithelial cells with HPβCD and MβCD reduces the ability of OMVs to inhibit VX-809 stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion, and 3) to test the hypothesis that HPβCD and MβCD inhibit biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CF epithelial cells.

Primary CF (Phe508del/Phe508del) human bronchial epithelial cells (CF HBEC) were obtained from Dr. Scott Randell (University of North Carolina) and were maintained in culture, as described previously (14), and studied between passages 4–8. Results were independent of passage number. The Dartmouth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects has determined that the use of CF HBEC cells in this study is not considered human subject research because cells are taken from discarded tissue and contain no patient identifiers. CFBE41o cells (CFBE: Phe508del/Phe508del) were provided by Dr. J. P. Clancy (University of Cincinnati, OH). CF HBEC and CFBE cells were seeded at 500,000 onto 12-mm Snapwell permeable supports (Corning, Corning, NY) coated with either 50 μg/ml Collagen type IV (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for CF HBEC or fibronectin (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for CFBE cells and grown in an air-liquid interface (ALI) at 37°C for 3–4 wk for CF HBEC, or 7–8 days for CFBE cells to establish polarized monolayers, as described in detail previously (32, 34). VX-809 (3 μM) or vehicle was added to the basolateral media 48 h before experiments.

P. aeruginosa and OMV isolation.

P. aeruginosa [strain PAO1 and clinical strain SMC1585 (23)] was grown overnight in lysogeny broth (LB) to an optical density of 1, and OMVs were isolated as described elsewhere in detail (3, 5–7, 19). Briefly, overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa were centrifuged for 1 h at 3,500 rpm (4°C) to pellet bacteria. The OMV-containing supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm and then a 0.22 μm PVDF membrane filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA) followed by centrifugation through an Amicon Ultra-15 filter (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to concentrate the supernatant. The concentrated liquid was resuspended in OMV buffer (20 mM HEPES, 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and ultracentrifuged for 2 h at 21,000 rpm (4°C) to pellet OMVs. The OMV pellet was resuspended in OptiPrep (Sigma-Aldrich), and a gradient was poured, followed by ultracentrifugation at 31,000 rpm for 16 h (4°C) to separate out the fractions. OMVs contained in the second, 500-µl fraction from the top of the OptiPrep gradient were quantified using BCA protein assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and with a NanoSight NS300 (Malvern Instruments, UK). To determine whether the number or size of OMVs were affected by cyclodextrins, isolated OMVs were treated with either vehicle, HPβCD (5 mM), or MβCD (5 mM) for 60 min, and the size and number of OMVs were determined by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) using the NanoSight NS300. The number of particles was similar across all treatment groups (5 × 1010/ml). Neither HPβCD nor MβCD had a significant effect on the size of OMVs, as determined by NTA (control: 121.4 ± 5.6 nm, HPβCD: 114.3 ± 10.7 nm, and MβCD: 105.7 ± 19.1 nm) in three replicate experiments, in agreement with previous studies demonstrating that MβCD has no effect on the size of P. aeruginosa OMVs (4). This is not unexpected since Pseudomonas aeruginosa does not synthesize cholesterol, and the major mechanism of action of cyclodextrins is to remove cholesterol from membranes (10).

Ussing chamber measurements of Phe508del-CFTR Cl− currents.

As described in detail elsewhere (31, 32, 35), cells on Snapwell filters were mounted in Ussing chambers. CF HBEC or CFBE cells were treated with vehicle, HPβCD (5 mM), or MβCD (5 mM) (Sigma) on the apical side or basolateral side of monolayers. For apical addition, drugs were added to 300 μl of DMEM (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) or ALI media for 30 min. For basolateral treatment, drugs were added to 1.5 ml of DMEM or ALI media. OMVs were added to the apical side of cells for 1 h in the presence of vehicle, HPβCD, or MβCD before the transepithelial voltage was clamped to 0 mV, and the short circuit current (Isc) was measured as described previously (31, 32, 35). Subsequently, amiloride (50 μM) was added to the apical solution to inhibit sodium reabsorption. Thereafter, Phe508del-CFTR Cl− secretion was stimulated with forskolin (10 μM; Sigma-Aldrich), followed by VX-770 (ivacaftor; 5 μM, Selleckchem, Houston, TX). Finally, thiazolidinone (CFTRinh-172, 20 μM; Millipore, Billerica, MA) was added to the apical solution to inhibit Phe508del-CFTR Cl− secretion. Data are expressed as the CFTRinh-172 inhibited Isc, which is presented as μA/cm2. Data were collected and analyzed using the Data Acquisition Software Acquire and Analyze (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA). Although there was some variability in the response of primary CF HBEC to VX-809 and the other experimental treatments in this study, cells from all donors responded in the same qualitative way, as shown previously (2). Similar variability was also observed in studies examining the clinical efficacy of lumacaftor/ivacaftor (41).

Cholesterol assay.

To confirm that HPβCD and MβCD reduced cell cholesterol, we measured cholesterol using the Amplex red cholesterol assay exactly as recommended by the manufacturer (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA).

Western blot analysis of Phe508del CFTR.

The amount of Phe508del CFTR in the apical plasma membrane of CFBE cells was measured by domain-selective cell surface biotinylation, as described in detail elsewhere (32, 33). Briefly, CFBE cells were treated with vehicle, VX-809 alone, VX-809 + HPβCD, VX-809 + MβCD, VX-809 + OMVs, VX-809 + HPβCD + OMV, or VX-809 + MβCD + OMV, as described above. Apical membrane proteins were biotinylated, isolated by streptavidin-agarose beads, eluted into SDS sample buffer, and separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE. The blots were probed for Phe508del CFTR using the CFTR 596 monoclonal antibody (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Bethesda, MD), an antibody that has been demonstrated to detect Phe508del CFTR (39).

Cytotoxicity.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release by CF HBEC was used to assess cytotoxicity of all treatments and was measured using the Promega (Madison, WI) CytoTox 96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay as recommended by the manufacturer.

P. aeruginosa biofilm formation and planktonic growth.

The effects of cyclodextrins on planktonic growth and biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa were examined as described previously in detail (1, 26). Briefly, a 1:100 dilution of an overnight culture of planktonic P. aeruginosa (2×106 CFU) in LB was added to each well of a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic 96-well microtiter plate. Either vehicle (LB), HPβCD, or MβCD was added to the wells, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Thereafter, the supernatant was carefully transferred to a 96-well plate and read in a plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT) at an OD of 600 nm for determination of planktonic P. aeruginosa. To measure biofilm formation, the plates, after removal of the supernatant, were gently washed with distilled water, and the water was then removed. A 1% solution of crystal violet was added to each well (crystal violet stains biofilms, but not the PVC) and incubated at room temperature for 15 min, rinsed twice with water and allowed to dry for a few hours or overnight. 30% acetic acid was added to each well to solubilize the crystal violet and the intensity of crystal violet was determined by an OD of 550 nm using a plate reader.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using the R language and environment for statistical computing version 3.5.0 (27). Statistical significance was calculated with mixed-effect linear models with donor or batch as a random effect using the R package “nlme” (27). N indicates the number of donors for CF HBEC or the number of monolayers for CFBE cells. Each experiment was performed with a minimum of three CF HBEC donors or CFBE cells from at least three passages. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

HPβCD and MβCD reduce OMV inhibition of PheF508del CFTR Cl− secretion.

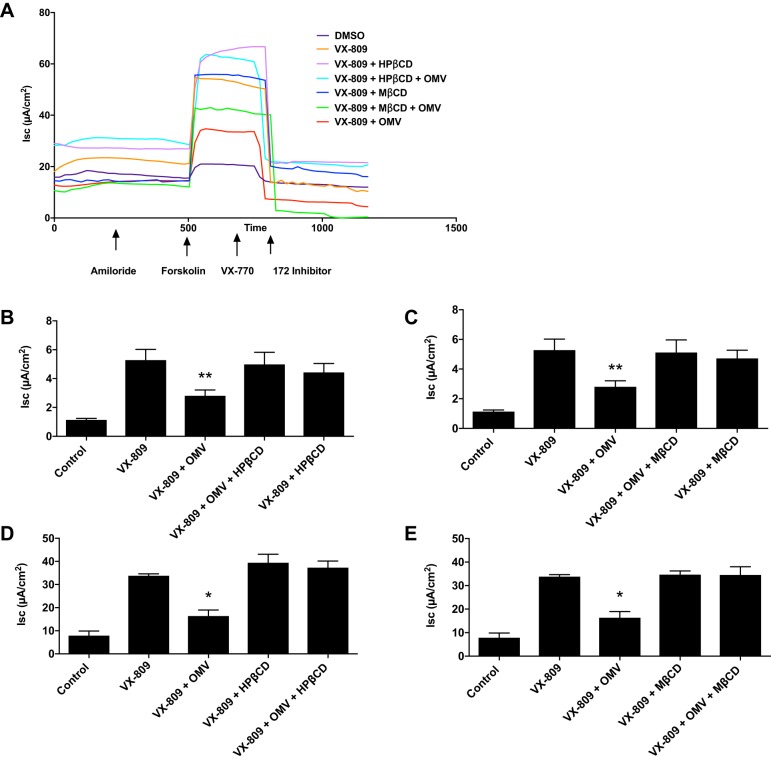

Previously, we demonstrated that VX-809 increased Phe508del CFTR plasma membrane density and Cl− secretion and that P. aeruginosa eliminated VX-809 stimulated Cl− secretion by CF HBEC and CFBE cells (32). Thus, experiments were conducted to determine whether the reduction of the VX-809 stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by P. aeruginosa was mediated by secreted OMVs and whether the inhibition could be eliminated when blocking OMV fusion through a reduction in membrane cholesterol with HPβCD or MβCD. We confirm our previous study demonstrating that VX-809 increased Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by CF HBEC and CFBE cells (Fig. 1). The addition of either HPβCD or MβCD alone to the apical side of monolayers, in the absence of OMVs, had no effect on VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by CF HBEC or CFBE cells (Fig. 1). OMVs inhibited VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by CF HBEC and CFBE cells. However, HPβCD and MβCD reduced the inhibitory effect of OMVs on VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by CF HBEC and CFBE cells (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A: representative current traces of CFBE cells. Amiloride (50 μM) was added to the apical solution to inhibit the short circuit current (Isc) attributed to sodium reabsorption, which is negligible in CFBE cells. Subsequently, Isc was stimulated with forskolin (10 μM), followed by VX-770 (5 μM), and thiazolidinone (CFTRinh-172, 20 μM), which rapidly inhibited Phe508del CFTR-mediated Isc. Note that all compounds were added to the apical solution at slightly different times in the protocol (the arrows signify the approximate “average” time when the compound was added). x-axis values are presented in seconds. B and C: effects of apical hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD; 5 mM) and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) CD (5 mM) alone and in combination with outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) on Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by primary CF HBEC. D and E: effects of apical HPβCD (5 mM) and MβCD (5 mM) alone and in combination with OMVs on Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by CFBE cells. Control is the addition of vehicle (DMSO). In each panel, all values are significantly different from control (P < 0.05). *P < 0.05 vs. all other groups; **P < 0.01 vs. all other groups. n = 5 for CF HBEC (B and C), n = 3 for CFBE cells (D and E).

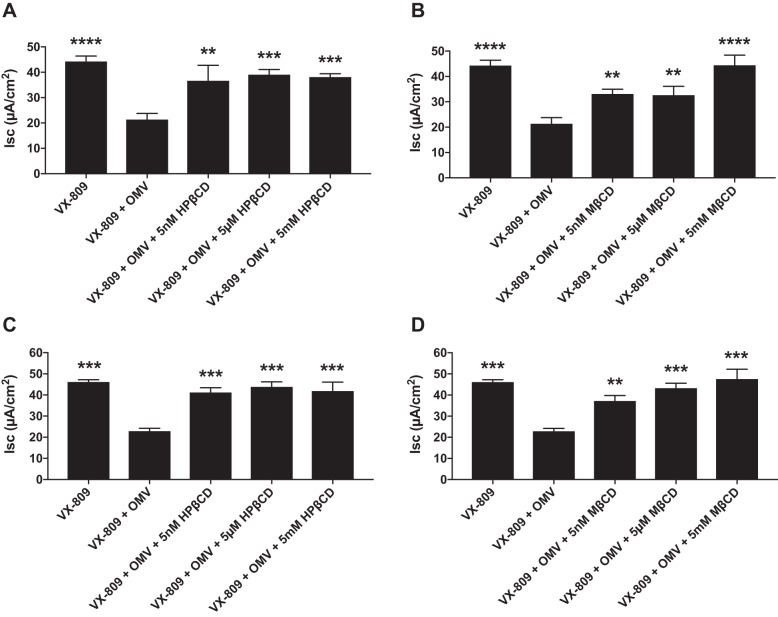

The next set of experiments was conducted to examine the dose-dependent effects of the cyclodextrins (5 nM, 5 μM, and 5 mM) on OMV inhibition of VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion. For these experiments, OMVs were isolated from PAO1 and a clinical strain of P. aeruginosa (SMC1585) (23). All concentrations of HPβCD and MβCD tested significantly reduced the ability of OMVs to reduce VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A and B: dose-dependent effects of apical hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) on Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by CFBE cells. Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) were isolated from PAO1. C and D: dose-dependent effects of apical HPβCD and MβCD on Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by CFBE cells. OMVs were isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain SMC1585. In each panel, OMVs alone significantly reduced Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion, and cyclodextrins significantly increased CFTR Cl− secretion compared with VX-809 + OMV at all concentrations tested. **P < 0.01 vs. VX-809 + OMV, ***P < 0.001 vs. VX-809 + OMV, ****P < 0.0001 vs. VX-809 + OMV. n = 6 for PAO1 OMV (A and B). n = 3 for SMC1585 OMVs (C and D).

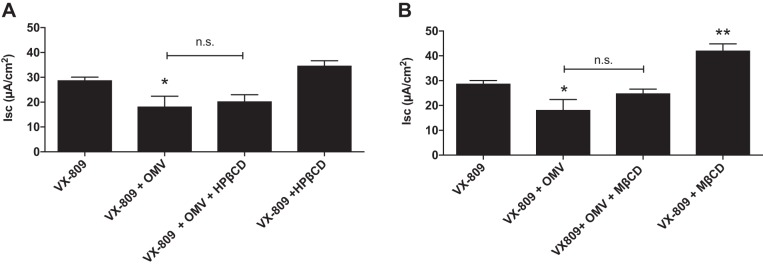

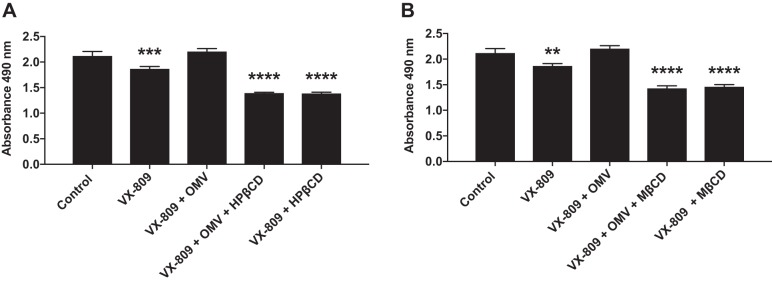

The effects of basolateral addition of HPβCD and MβCD were also examined. Whereas apical HPβCD and MβCD alone had no effect on Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion (Fig. 1), MβCD that was added to the basolateral side of CFBE monolayers increased VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion (Fig. 3). As shown previously in intestinal epithelial cells, this effect is most likely due to hyperpolarization of the basolateral membrane voltage, which increases the electrochemical driving force for Cl− secretion across the apical membrane (20). The addition of OMVs to the apical side of CFBE cells significantly decreased Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion (Fig. 3), confirming experiments presented in Fig. 1. HPβCD and MβCD added to the basolateral side of CFBE monolayers did not attenuate the ability of apical OMVs to reduce VX-809 stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion (Fig. 3). Thus, cyclodextrins reduce the ability of OMVs to inhibit Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion only when they are added to the apical side of CFBE cells.

Fig. 3.

Effects of basolateral addition of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD; A) and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD; B) alone and on the outer membrane vesicle (OMV)-mediated inhibition of Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by CFBE cells. n.s. = P > 0.05. *P < 0.05 vs. VX-809; **P < 0.01 vs. VX-809. n = 3.

HPβCD and MβCD reduce cholesterol in CFBE cells.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that filipin III, HPβCD, and MβCD reduce lipid rafts and the cholesterol content of cells (11, 21, 43). To confirm the ability of HPβCD and MβCD to reduce the cholesterol content of human bronchial epithelial cells, we measured the cholesterol content of CFBE cells by a biochemical assay, as described in materials and methods. HPβCD and MβCD dramatically reduced cell cholesterol in CFBE cells (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effects of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) (5 mM for 30 min) and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) (5 mM for 30 min) on the amount of cholesterol in CFBE cells, as determined by the Amplex Red cholesterol assay. *P < 0.05 vs. VX-809; **P < 0.01 vs. VX-809. n = 3.

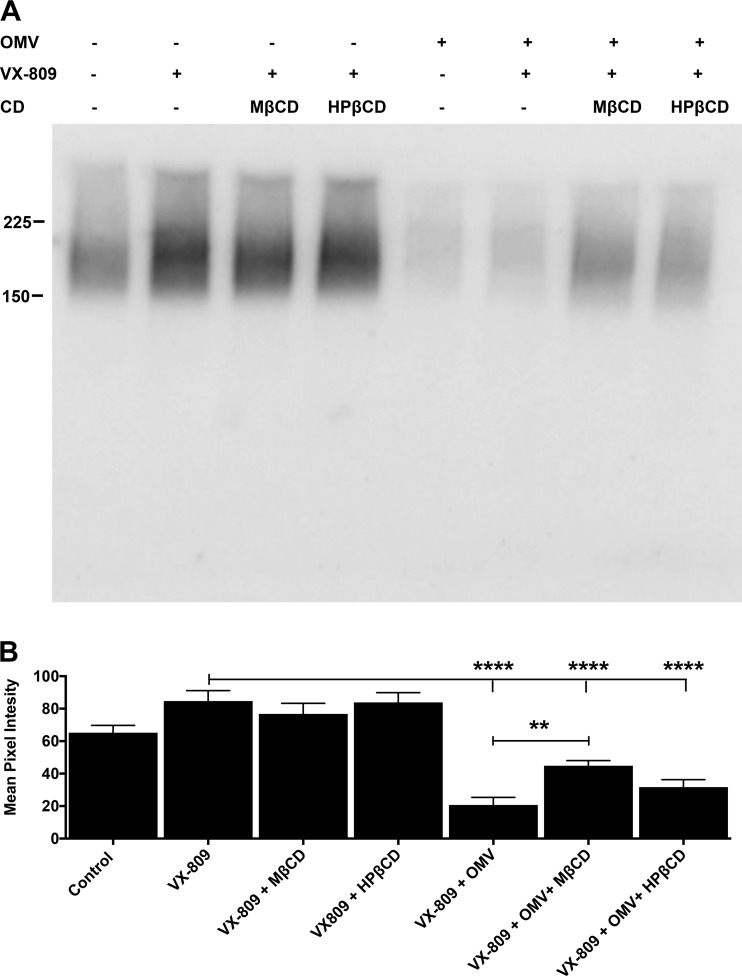

OMVs reduce apical membrane Phe508del CFTR in CFBE cells.

To begin to examine the mechanism whereby cyclodextrins reduce the ability of OMVs to decrease VX-809-rescued Phe508del-CFTR Cl- secretion, we measured Phe508del CFTR in the apical membrane by cell surface biotinylation, as described in materials and methods. As shown previously by others (32, 36, 38) and us (32, 36, 38), VX-809 increased apical membrane PheF508del CFTR, although in this study, the increase in apical plasma membrane Phe508del CFTR did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5). Neither HPβCD nor MβCD alone had any effect on VX-809-stimulated apical membrane Phe508del CFTR protein levels (Fig. 5). OMVs alone reduced apical membrane Phe508del CFTR protein (Fig. 5). HPβCD had a small effect on apical membrane Phe508del CFTR in cells exposed to OMVs, but the increase was not significant. MβCD significantly increased apical membrane Phe508del CFTR in cells exposed to OMVs, compared with the effect of OMVs alone (Fig. 5). This result was unexpected since both MβCD and HPβCD blocked the ability of OMVs to reduce VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion (Fig. 1). This lack of concordance between measured apical membrane Phe508del CFTR protein and Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion is discussed below.

Fig. 5.

A: representative Western blot of Phe508del-CFTR in the apical membrane of CFBE cells treated with vehicle (control), VX-809 (lumacaftor) alone, VX-809 + methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), VX-809 + hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HβCD), outer membrane vesicles (OMV) alone, VX-809 + OMV, VX-809 + OMV + MβCD, and VX-809 + OMV + HPβCD. This blot reveals that Phe508del CFTR is present in the apical membrane of vehicle-treated cells, an observation consistent with data in Fig. 1, D and E, demonstrating that vehicle-treated CFBE cells have measurable Phe508del CFTR Cl− currents. B: summary of apical membrane Phe508del-CFTR. ****P < 0.0001; **P < 0.001. n = 5.

HPβCD and MβbCD are not cytotoxic.

Although numerous studies have shown that cyclodextrins are not cytotoxic [reviewed in (10)], LDH in the cell culture media was measured to determine whether any treatment, including HPβCD or MβCD, was cytotoxic to CF HBEC. As anticipated, on the basis of previous studies, neither HPβCD nor MβCD was cytotoxic (Fig. 6). In fact, VX-809 alone and the combinations of VX-809 + OMV + HPβCD, VX-809 + HPβCD, VX-809 + OMV + MβCD, and VX-809 + MβCD significantly reduced LDH release by CF HBEC compared with vehicle control. Thus, as shown previously by several groups, HPβCD and MβCD—cyclic oligosaccharides used in the pharmaceutical and food industries as solubilizing agents for poorly soluble chemicals, including lipophilic drugs—are not cytotoxic (reviewed in Ref. 10).

Fig. 6.

Effects of outer membrane vesicles (OMV), hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD; 5 mM) and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD; 5 mM) on lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release by cystic fibrosis (CF) human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEC) grown on Snapwell filters. LDH levels were measured at the end of each experiment, after 2 h of exposure to the cyclodextrins. A: HPβCD. B: MβCD. In preliminary studies, neither HPβCD nor MβCD (2.5, 5, 10, 15, and 20 mM) for 6 h were cytotoxic to CF HBEC or CFBE cells. **P < 0.01 vs. control; ***P < 0.001 vs. control; ****P < 0.0001 vs. control. n = 5.

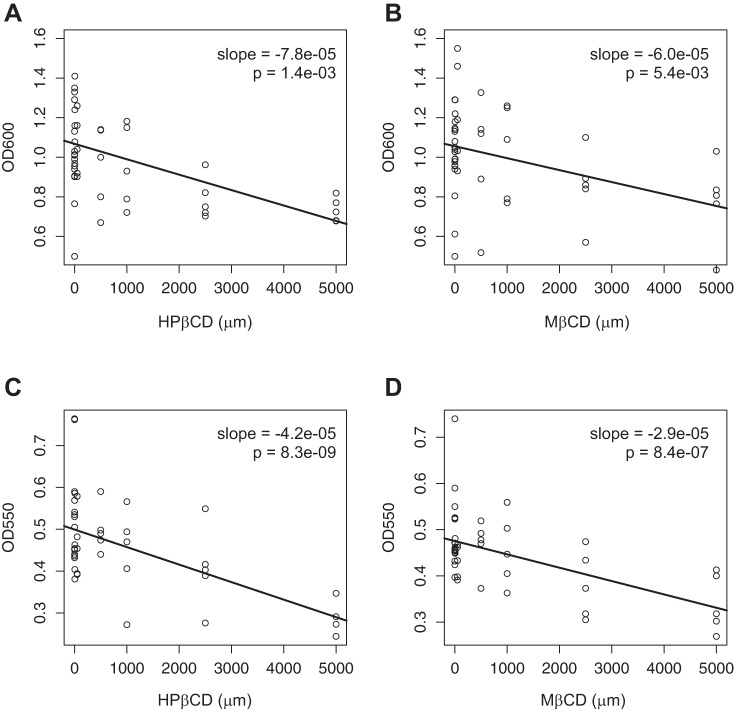

Cyclodextrins reduce P. aeruginosa planktonic growth and biofilm formation.

Cyclodextrins inhibit quorum sensing by Gram-negative bacteria, a key factor in the development of antibiotic resistance, which is a significant issue in the lungs of CF patients (24). Having shown that HPβCD and MβCD inhibit the OMV-induced reduction in Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion, we conducted studies to determine whether HPβCD and MβCD have additional benefits, such as the ability to reduce planktonic growth and biofilm development of P. aeruginosa. The dose-response relationships presented in Fig. 7 demonstrate that HPβCD and MβCD reduce both planktonic growth and biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa in a dose-dependent manner. Since many Gram-negative bacteria including P. aeruginosa and B. cepacia use quorum sensing to form biofilms in the lungs of CF patients, HPβCD and MβCD may also reduce biofilm formation by other pathogens.

Fig. 7.

Effects of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) on planktonic growth (A and B, respectively) and on biofilm formation (C and D) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Significance was established using a mixed-effect linear model with batch as random effect and HPβCD or MβCD as a continuous variable. Each data point represents one well of bacteria.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate for the first time that OMVs secreted by P. aeruginosa reduce VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by CF HBEC and CFBE cells and that apical addition of HPβCD and MβCD reduces cell cholesterol and the OMV-induced decrease in Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion. Previously, we demonstrated that the ability of OMV to reduce wt-CFTR Cl− secretion is primarily the result of OMV-mediated delivery of the virulence factor Cif into airway cells, which enhances the ubiquitination and lysosomal degradation of wt-CFTR, thereby reducing wt-CFTR Cl− secretion, mucociliary transport by airway epithelial cells, and the ability of mouse lungs to clear P. aeruginosa (3, 6, 7, 18, 31, 32). In addition, we also showed that filipin III, a compound that disrupts cholesterol-rich lipid rafts in the apical membrane of airway epithelial cells, reduced OMV fusion with CFBE cells, and prevented delivery of OMV-associated Cif into human bronchial epithelial cells (6, 31). Our results are in agreement with other studies demonstrating that HPβCD and MβCD reduce cell cholesterol and that MβCD reduces OMV fusion with lipid rafts in T84 and Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells, as well as A549 cells, an adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial cell line (4, 10, 13, 25, 29). However, we are reluctant to conclude that HPβCD and MβCD reduced the ability of OMVs to inhibit Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by disrupting cholesterol-rich lipid rafts since cyclodextrins have many nonspecific effects, including removing cholesterol from both raft and nonraft domains of plasma membranes, and altering the distribution of cholesterol between the plasma membrane and intracellular membranes (10, 25). Moreover, cyclodextrins have been reported to extract other hydrophobic molecules from plasma membranes, including phospholipids (25). Additional studies, beyond the scope of this report, are required to elucidate the mechanism(s), whereby HPβCD and MβCD reduce the ability of OMVs to inhibit Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion.

We also observed in the present study that HPβCD and MβCD reduce planktonic growth and biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa. These observations are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that cyclodextrins inhibit quorum sensing by Gram-negative bacteria, a key factor in the development of biofilms and antibiotic resistance of bacteria in the CF lung (24). Since many Gram-negative bacteria, including P. aeruginosa and B. cepacia form biofilms in the lungs of CF patients, our biofilm data suggest that HPβCD and MβCD may also reduce biofilm formation by other Gram-negative pathogens, although this has yet to be experimentally verified. In addition, the apical addition of MβCD should be considered as a therapeutic approach since MβCD reduces monocyte chemotaxis (28); restores surfactant surface tension, which is impaired in CF; and reduces inflammation (10, 17). Thus, because cyclodextrins have been approved by the FDA for use in solubilizing lipophilic drugs, are considered safe and nontoxic, and reduce planktonic growth and biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa, our findings suggest that the apical administration of HPβCD or MβCD may be an effective therapeutic approach to mitigate the negative effects of P. aeruginosa OMVs to inhibit VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion by airway epithelial cells. Additional studies are required to examine the clinical utility of HPβCD and MβCD for CF.

There are several issues of potential concern with regard to the use of cyclodextrins in CF patients. Plasma levels of cholesterol are low in CF compared with healthy individuals (15); thus, systemic administration of HPβCD or MβCD may further reduce plasma cholesterol. However, the delivery of HPβCD or MβCD to the apical side of epithelial cells in the lungs is unlikely to reduce plasma cholesterol. Additional experiments are required to examine the effect of the route of administration of cyclodextrins on cholesterol in BALF and plasma. Several studies have also shown that cholesterol regulates CFTR; however, the effects of modulating the cholesterol content of the plasma membrane on CFTR activity varies. Some CFTR is present in cholesterol-rich lipid rafts in the apical membrane of epithelial cells, and cholesterol is essential for NHERF1 to activate CFTR Cl− secretion (30). COase, which reduces membrane cholesterol, decreases single-channel CFTR Cl− currents in human embryonic kidney 293 cells (30). By contrast, MβCD increases forskolin-stimulated anion efflux from fibroblasts expressing PheF508del CFTR (21). Furthermore, membrane cholesterol correlates with both genetic and pharmacological CFTR correction (22). By contrast, other studies have failed to show a correlation between cholesterol content of the apical membrane and CFTR Cl− secretion or abundance. For example, apical addition of MβCD had no effect on short-circuit current across mouse colon (20) and across CF HBEC and CFBE cells (Fig. 1). Apical MβCD reduced cholesterol levels in Calu-3 and T84 cells but had no effect on forskolin-stimulated CFTR Cl− secretion (42). Relevant to the present study, MβCD completely reduced internalization of temperature-rescued and VX-325-rescued PheF508del CFTR in primary CF HBEC (8). Thus, the data in the literature suggest that the effect of cyclodextrins and membrane cholesterol content on CFTR Cl− secretion depends on cell type and experimental conditions.

We note the dissociation between the observation that HPβCD and MβCD completely blocked the ability of OMVs to reduce Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion (Fig. 1) and the inability of HPβCD and MβCD to completely block the OMV-mediated reduction in apical membrane Phe508del CFTR measured by cell surface biotinylation (Fig. 5). It is not unreasonable to expect a one-to-one correlation between Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion and apical membrane Phe508del CFTR. For example, in a previous study, we observed that OMVs reduced apical plasma membrane wt-CFTR and that filipin III, which disrupts lipid rafts, completely inhibited the OMV-induced decrease in apical plasma membrane wt-CFTR (6). There are several possible explanations for the dissociation between Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion and the measured apical membrane Phe508del CFTR in the present study. First, HPβCD and MβCD may interfere with the ability to biotinylate CFTR in the apical membrane by a mechanism that has not yet been identified. Second, as noted above, cyclodextrins have nonspecific, off-target effects, since they have been shown to remove cholesterol from both raft and nonraft domains of the apical plasma membrane, alter the distribution of cholesterol between plasma and intracellular membranes and reduce membrane phospholipids (10, 25). Several studies have shown that ion channels have cholesterol-dependent activity and localize to lipid rafts. For example, MβCD redistributes calcium-activated K+ (BK) channels from detergent-insoluble, cholesterol-rich, lipid rafts into detergent-soluble fractions, which increases K+ channel activity, thereby increasing the cell-negative voltage that increases the electrochemical gradient for Cl− secretion across the apical membrane (20). It is possible that off-target effects of HPβCD and MβCD and/or changing the distribution of CFTR between cholesterol-rich lipid rafts and nonraft domains of the plasma membrane may account for the dissociation between Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion and the ability to detect apical membrane Phe508del CFTR by biotinylation. Elucidation of the dissociation between Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion and the amount of CFTR in the apical membrane as determined by biotinylation will require additional studies, which are beyond the scope of the present study.

Although Orkambi—a combination drug composed of VX-809 and VX-770—increases forced expiratory volume in 1 s and reduces exacerbations in CF patients homozygous for the Phe508del CFTR mutation, it does not significantly reduce the burden of P. aeruginosa in the CF lung (41). Because lung infections with P. aeruginosa cause excessive lung inflammation and damage, and are responsible for death in ~80% of CF patients, data from this and other studies from our laboratory suggest that administration of HPβCD or MβCD to the lungs of CF patients with P. aeruginosa lung infections may reduce inflammation, reduce biofilm formation, and increase the efficacy of VX-809 by reducing the negative effect of P. aeruginosa OMVs on Phe508del CFTR Cl− section and mucociliary clearance of bacteria from the lungs (41). One major caveat of the use of HPβCD in a chronic disease like CF, however, is that its long-term systemic use is accompanied by hearing loss (40). Thus, aerosolization into the lungs of either HPβCD or MβCD, which is FDA approved for the solubilizing of drugs, may be a valuable addition to the CF treatment regimen. Additional studies, including a full-dose response analysis of HPβCD or MβCD and longer, more clinically relevant times of exposure, are required to determine the clinical utility of HPβCD or MβCD for CF.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that P. aeruginosa inhibition of VX-809 stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion is mediated by OMVs, that a reduction of cell cholesterol with HPβCD and MβCD blocks the ability of OMVs to reduce VX-809-stimulated Phe508del CFTR Cl− secretion, and that HPβCD and MβCD inhibit biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa. Both effects would be beneficial to CF patients.

GRANTS

This study was supported by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Grants STANTO16G0 and STANTO19R0 and National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-074175 (to B. A. Stanton).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.B., K.K., and B.A.S. conceived and designed research; R.B. and K.K. performed experiments; R.B., K.K., and B.A.S. analyzed data; R.B., K.K., and B.A.S. interpreted results of experiments; R.B., K.K., and B.A.S. prepared figures; R.B., K.K., and B.A.S. drafted manuscript; R.B., K.K., and B.A.S. edited and revised manuscript; R.B., K.K., and B.A.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Victoria Holden reviewed the manuscript and provided valuable suggestions. We thank Charles and Melissa O’Brien and the Flatley Foundation for support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson GG, Moreau-Marquis S, Stanton BA, O’Toole GA. In vitro analysis of tobramycin-treated Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms on cystic fibrosis-derived airway epithelial cells. Infect Immun 76: 1423–1433, 2008. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01373-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awatade NT, Uliyakina I, Farinha CM, Clarke LA, Mendes K, Solé A, Pastor J, Ramos MM, Amaral MD. Measurements of functional responses in human primary lung cells as a basis for personalized therapy for cystic fibrosis. EBioMedicine 2: 147–153, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballok AE, Filkins LM, Bomberger JM, Stanton BA, O’Toole GA. Epoxide-mediated differential packaging of Cif and other virulence factors into outer membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol 196: 3633–3642, 2014. doi: 10.1128/JB.01760-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauman SJ, Kuehn MJ. Pseudomonas aeruginosa vesicles associate with and are internalized by human lung epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol 9: 26, 2009. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauman SJ, Kuehn MJ. Purification of outer membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their activation of an IL-8 response. Microbes Infect 8: 2400–2408, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bomberger JM, Maceachran DP, Coutermarsh BA, Ye S, O’Toole GA, Stanton BA. Long-distance delivery of bacterial virulence factors by Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane vesicles. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000382, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bomberger JM, Ye S, Maceachran DP, Koeppen K, Barnaby RL, O’Toole GA, Stanton BA. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa toxin that hijacks the host ubiquitin proteolytic system. PLoS Pathog 7: e1001325, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cholon DM, O’Neal WK, Randell SH, Riordan JR, Gentzsch M. Modulation of endocytic trafficking and apical stability of CFTR in primary human airway epithelial cultures. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L304–L314, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00016.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cianciola NL, Carlin CR, Kelley TJ. Molecular pathways for intracellular cholesterol accumulation: common pathogenic mechanisms in Niemann-Pick disease Type C and cystic fibrosis. Arch Biochem Biophys 515: 54–63, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.di Cagno MP. The potential of cyclodextrins as novel active pharmaceutical ingredients: A short overview. Molecules 22: E1, 2016. doi: 10.3390/molecules22010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudez T, Borot F, Huang S, Kwak BR, Bacchetta M, Ollero M, Stanton BA, Chanson M. CFTR in a lipid raft-TNFR1 complex modulates gap junctional intercellular communication and IL-8 secretion. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783: 779–788, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis TN, Leiman SA, Kuehn MJ. Naturally produced outer membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa elicit a potent innate immune response via combined sensing of both lipopolysaccharide and protein components. Infect Immun 78: 3822–3831, 2010. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00433-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elmi A, Watson E, Sandu P, Gundogdu O, Mills DC, Inglis NF, Manson E, Imrie L, Bajaj-Elliott M, Wren BW, Smith DG, Dorrell N. Campylobacter jejuni outer membrane vesicles play an important role in bacterial interactions with human intestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun 80: 4089–4098, 2012. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00161-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fulcher ML, Randell SH. Human nasal and tracheo-bronchial respiratory epithelial cell culture. Methods Mol Biol 945: 109–121, 2013. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-125-7_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelzo M, Sica C, Elce A, Dello Russo A, Iacotucci P, Carnovale V, Raia V, Salvatore D, Corso G, Castaldo G. Reduced absorption and enhanced synthesis of cholesterol in patients with cystic fibrosis: a preliminary study of plasma sterols. Clin Chem Lab Med 54: 1461–1466, 2016. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2015-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grassmé H, Jendrossek V, Riehle A, von Kürthy G, Berger J, Schwarz H, Weller M, Kolesnick R, Gulbins E. Host defense against Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires ceramide-rich membrane rafts. Nat Med 9: 322–330, 2003. doi: 10.1038/nm823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunasekara L, Al-Saiedy M, Green F, Pratt R, Bjornson C, Yang A, Michael Schoel W, Mitchell I, Brindle M, Montgomery M, Keys E, Dennis J, Shrestha G, Amrein M. Pulmonary surfactant dysfunction in pediatric cystic fibrosis: Mechanisms and reversal with a lipid-sequestering drug. J Cyst Fibros 16: 565–572, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hvorecny KL, Dolben E, Moreau-Marquis S, Hampton TH, Shabaneh TB, Flitter BA, Bahl CD, Bomberger JM, Levy BD, Stanton BA, Hogan DA, Madden DR. An epoxide hydrolase secreted by Pseudomonas aeruginosa decreases mucociliary transport and hinders bacterial clearance from the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 314: L150–L156, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00383.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koeppen K, Hampton TH, Jarek M, Scharfe M, Gerber SA, Mielcarz DW, Demers EG, Dolben EL, Hammond JH, Hogan DA, Stanton BA. A novel mechanism of host-pathogen interaction through sRNA in bacterial outer membrane vesicles. PLoS Pathog 12: e1005672, 2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam RS, Shaw AR, Duszyk M. Membrane cholesterol content modulates activation of BK channels in colonic epithelia. Biochim Biophys Acta 1667: 241–248, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim CH, Bijvelds MJ, Nigg A, Schoonderwoerd K, Houtsmuller AB, de Jonge HR, Tilly BC. Cholesterol depletion and genistein as tools to promote F508delCFTR retention at the plasma membrane. Cell Physiol Biochem 20: 473–482, 2007. doi: 10.1159/000107531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu B, Li L, Schneider M, Hodges CA, Cotton CU, Burgess JD, Kelley TJ. Electrochemical measurement of membrane cholesterol correlates with CFTR function and is HDAC6-dependent. J Cyst Fibros S1569-1993(18)30630-1, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moreau-Marquis S, Coutermarsh B, Stanton BA. Combination of hypothiocyanite and lactoferrin (ALX-109) enhances the ability of tobramycin and aztreonam to eliminate Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms growing on cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. J Antimicrob Chemother 70: 160–166, 2015. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morohoshi T, Tokita K, Ito S, Saito Y, Maeda S, Kato N, Ikeda T. Inhibition of quorum sensing in gram-negative bacteria by alkylamine-modified cyclodextrins. J Biosci Bioeng 116: 175–179, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Donoghue EJ, Krachler AM. Mechanisms of outer membrane vesicle entry into host cells. Cell Microbiol 18: 1508–1517, 2016. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Toole GA, Kolter R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol 28: 449–461, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014. (http://www.R-project.org/). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saha AK, Mousavi M, Dallo SF, Evani SJ, Ramasubramanian AK. Influence of membrane cholesterol on monocyte chemotaxis. Cell Immunol 324: 74–77, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaar V, de Vries SP, Perez Vidakovics ML, Bootsma HJ, Larsson L, Hermans PW, Bjartell A, Mörgelin M, Riesbeck K. Multicomponent Moraxella catarrhalis outer membrane vesicles induce an inflammatory response and are internalized by human epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol 13: 432–449, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheng R, Chen Y, Yung Gee H, Stec E, Melowic HR, Blatner NR, Tun MP, Kim Y, Källberg M, Fujiwara TK, Hye Hong J, Pyo Kim K, Lu H, Kusumi A, Goo Lee M, Cho W. Cholesterol modulates cell signaling and protein networking by specifically interacting with PDZ domain-containing scaffold proteins. Nat Commun 3: 1249, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stanton BA. Effects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on CFTR chloride secretion and the host immune response. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 312: C357–C366, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00373.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanton BA, Coutermarsh B, Barnaby R, Hogan D. Pseudomonas aeruginosa reduces VX-809 stimulated F508del-CFTR chloride secretion by airway epithelial cells. PLoS One 10: e0127742, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swiatecka-Urban A, Brown A, Moreau-Marquis S, Renuka J, Coutermarsh B, Barnaby R, Karlson KH, Flotte TR, Fukuda M, Langford GM, Stanton BA. The short apical membrane half-life of rescued ΔF508-cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) results from accelerated endocytosis of ΔF508-CFTR in polarized human airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 280: 36762–36772, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508944200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swiatecka-Urban A, Moreau-Marquis S, Maceachran DP, Connolly JP, Stanton CR, Su JR, Barnaby R, O’toole GA, Stanton BA. Pseudomonas aeruginosa inhibits endocytic recycling of CFTR in polarized human airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C862–C872, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00108.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talebian L, Coutermarsh B, Channon JY, Stanton BA. Corr4A and VRT325 do not reduce the inflammatory response to P. aeruginosa in human cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 23: 199–204, 2009. doi: 10.1159/000204108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trinh NT, Bilodeau C, Maillé É, Ruffin M, Quintal MC, Desrosiers MY, Rousseau S, Brochiero E. Deleterious impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function and rescue in airway epithelial cells. Eur Respir J 45: 1590–1602, 2015. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00076214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Cao D, Neuberger T, Turnbull A, Singh A, Joubran J, Hazlewood A, Zhou J, McCartney J, Arumugam V, Decker C, Yang J, Young C, Olson ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M, Negulescu P. Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 18825–18830, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904709106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Stack JH, Straley KS, Decker CJ, Miller M, McCartney J, Olson ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M, Negulescu PA. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 18843–18848, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105787108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Meegen MA, Terheggen SW, Koymans KJ, Vijftigschild LA, Dekkers JF, van der Ent CK, Beekman JM. CFTR-mutation specific applications of CFTR-directed monoclonal antibodies. J Cyst Fibros 12: 487–496, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vite CH, Bagel JH, Swain GP, Prociuk M, Sikora TU, Stein VM, O’Donnell P, Ruane T, Ward S, Crooks A, Li S, Mauldin E, Stellar S, De Meulder M, Kao ML, Ory DS, Davidson C, Vanier MT, Walkley SU. Intracisternal cyclodextrin prevents cerebellar dysfunction and Purkinje cell death in feline Niemann-Pick type C1 disease. Sci Transl Med 7: 276ra26, 2015. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wainwright CE, Elborn JS, Ramsey BW, Marigowda G, Huang X, Cipolli M, Colombo C, Davies JC, De Boeck K, Flume PA, Konstan MW, McColley SA, McCoy K, McKone EF, Munck A, Ratjen F, Rowe SM, Waltz D, Boyle MP; TRAFFIC Study Group; TRANSPORT Study Group . Lumacaftor-ivacaftor in patients with cystic fibrosis homozygous for Phe508del CFTR. N Engl J Med 373: 220–231, 2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang D, Wang W, Duan Y, Sun Y, Wang Y, Huang P. Functional coupling of Gs and CFTR is independent of their association with lipid rafts in epithelial cells. Pflugers Arch 456: 929–938, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zidovetzki R, Levitan I. Use of cyclodextrins to manipulate plasma membrane cholesterol content: evidence, misconceptions and control strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768: 1311–1324, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]