Abstract

Background

Cystoscopy is commonly performed for diagnostic purposes to inspect the interior lining of the bladder. One disadvantage of cystoscopy is the risk of symptomatic urinary tract infection (UTI) due to pre‐existing colonization or by introduction of bacteria at the time of the procedure. However, the incidence of symptomatic UTI following cystoscopy is low. Currently, there is no consensus on whether antimicrobial agents should be used to prevent symptomatic UTI for cystoscopy.

Objectives

To assess the effects of antimicrobial agents compared with placebo or no treatment for prevention of UTI in adults undergoing cystoscopy.

Search methods

We comprehensively searched electronic databases of the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, LILACS, and CINAHL. We searched the WHO ICTRP and ClinicalTrials.gov for ongoing trials. We used no language or date restrictions in the electronic searches. We searched the reference lists of identified articles and contacted authors for related information. The last search of the electronic databases was 4 February 2019.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs that compared any prophylactic antibiotic versus placebo, no treatment, or other non‐antibiotic prophylaxis in adults undergoing cystoscopy. There was no restriction on the dose, frequency, formulation, duration, or mode of administration of the antibiotics.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. Our primary outcomes were systemic UTI, symptomatic UTI (composite of systemic and/or localized UTI), and serious adverse events. Secondary outcomes were minor adverse events, localized UTI, asymptomatic bacteriuria, and bacterial resistance. We assessed the quality of evidence using GRADE.

Main results

We included 20 RCTs and two quasi‐RCTs with 7711 participants, all of which compared antibiotic prophylaxis with placebo or no treatment control. We found no studies comparing antibiotic prophylaxis with non‐antibiotic prophylaxis.

Primary outcomes

Systemic UTI: antibiotic prophylaxis may have little or no effect on the risk of systemic UTI compared with placebo or no treatment (risk ratio (RR) 1.12, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.38 to 3.32; 5 RCTs; 504 participants; low‐quality evidence); this corresponds to two more people (95% CI 12 fewer to 46 more) per 1000 people developing a systemic UTI. We downgraded the quality of the evidence for study limitations and imprecision.

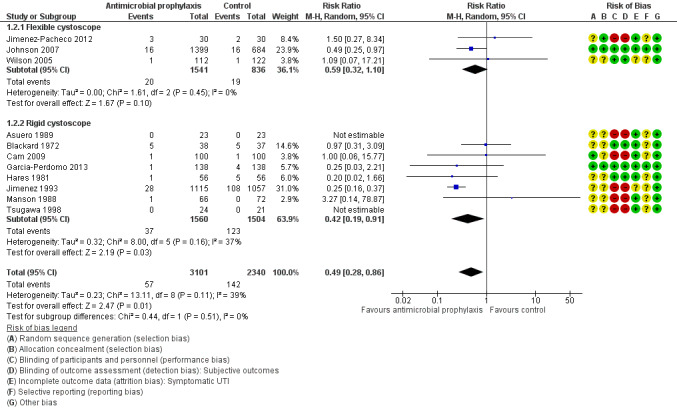

Symptomatic UTI: antibiotic prophylaxis may reduce the risk of symptomatic UTI (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.86; 11 RCTs; 5441 participants; low‐quality evidence); this corresponds to 30 fewer people (95% CI 42 fewer to 8 fewer) per 1000 people developing a symptomatic UTI when provided with antibiotic prophylaxis. We downgraded the quality of the evidence for study limitations and potential publication bias.

Serious adverse events: the studies reported no serious adverse events in either the intervention group or control group and no effect size could be calculated. Antibiotic prophylaxis may have little or no effect on serious adverse events (4 RCTs, 630 participants; very low‐quality evidence), but we are very uncertain of this finding. We downgraded the quality of the evidence for study limitations and very serious imprecision.

Secondary outcomes

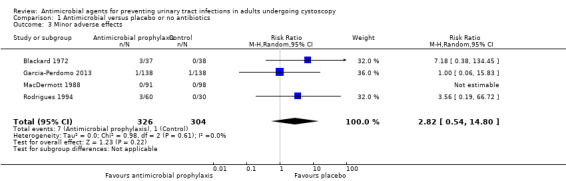

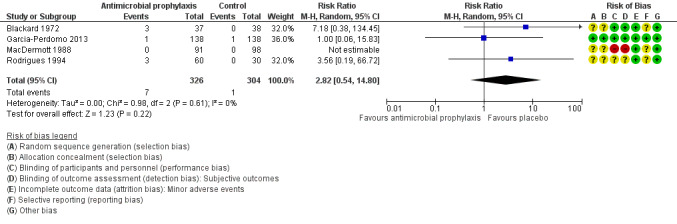

Minor adverse events: prophylactic antibiotics may have little or no effect on minor adverse events when compared with placebo or no treatment (RR 2.82, 95% CI 0.54 to 14.80; 4 RCTs; 630 participants; low‐quality evidence). We downgraded the quality of the evidence for study limitations and imprecision.

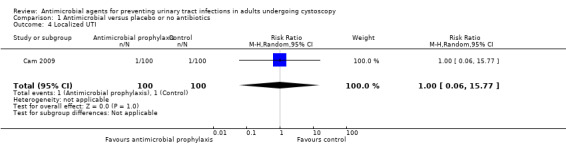

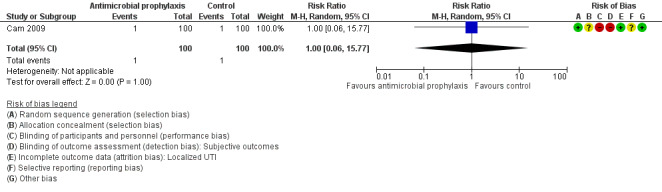

Localized UTI: prophylactic antibiotics may have little or no effect on the risk of localized UTI (RR 1.0, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.77; 1 RCT; 200 participants; very low‐quality evidence), but we were very uncertain of this finding. We downgraded the quality of the evidence for study limitations and very serious imprecision.

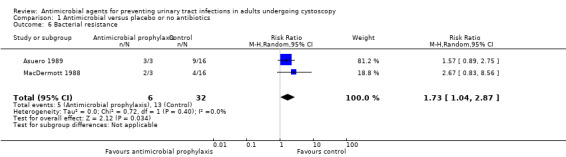

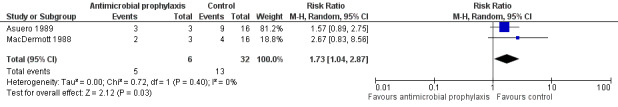

Bacterial resistance: prophylactic antibiotics may increase bacterial resistance (RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.87; 38 participants; 2 RCTs; very low‐quality evidence), but we were uncertain of this finding. We downgraded the quality of the evidence for study limitations, indirectness, and imprecision.

We were able to perform few secondary analyses; these did not suggest any subgroup effects.

Authors' conclusions

Antibiotic prophylaxis may reduce the risk of symptomatic UTI but not systemic UTIs. Serious and minor adverse events may not be increased with the use of antibiotic prophylaxis. The findings are informed by low‐ and very low‐quality evidence ratings for all outcomes.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Antibiotic Prophylaxis; Antibiotic Prophylaxis/adverse effects; Anti‐Infective Agents, Urinary; Anti‐Infective Agents, Urinary/adverse effects; Anti‐Infective Agents, Urinary/therapeutic use; Cystoscopy; Cystoscopy/adverse effects; Drug Resistance, Bacterial; Placebos; Placebos/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Urinary Tract Infections; Urinary Tract Infections/etiology; Urinary Tract Infections/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Antimicrobial agents for preventing urinary tract infections in adults undergoing cystoscopy

Review question

We reviewed the evidence for the benefits and harms of using antibiotics for cystoscopy (an examination of the inside of bladder) to prevent urinary tract infections (UTI).

Background

Cystoscopy may cause UTIs. This may cause bothersome symptoms like burning with urination due to an infection limited to the bladder or fevers and chills due to a more serious infection that has goes to the bloodstream, or a combination of burning, fevers, and chills. Antibiotics may prevent infections and reduce these symptoms but can also cause unwanted effects. It is uncertain whether people should be given antibiotics before this procedure.

Study characteristics

We found 22 studies with 7711 participants. These studies were published from 1971 to 2017. In these studies, chance decided whether people received an antibiotic or a placebo/no treatment. The evidence is current to 4 February 2019.

Key results

Antibiotics given for UTI prevention before cystoscopy may have had little or no effect on the risk of developing a more serious infection that went into the bloodstream.

They may have reduced the risk of infection when both serious infection that went into the bloodstream and infections limited to the bladder were taken together.

None of the people included in the trials had serious unwanted effects. Therefore, we concluded that antibiotics given for prevention of UTIs may not cause serious unwanted effects but we are very uncertain of this finding.

Antibiotics may also have had little or no effect on minor unwanted effects. They may also have had little or no effect on infections limited to the bladder taken alone, but we were very uncertain of this finding. People treated with antibiotics may have been more likely to have bacteria that were more resistant to antibiotics, but we are very uncertain of this finding.

Quality of the evidence

We rated the quality of the evidence as low or very low meaning that our confidence in the results was limited or very limited. The true effect of antibiotics for prevention of UTIs before cystoscopy may be quite different from what this review found.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Antimicrobial compared to placebo or no antibiotics for preventing urinary tract infections in adults undergoing cystoscopy.

| Antimicrobial compared to placebo or no antibiotics for preventing urinary tract infections in adults undergoing cystoscopy | |||||

| Patient or population: people undergoing cystoscopy Setting: various Intervention: antimicrobial Comparison: placebo or no antibiotics | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with placebo or no antibiotics | Risk difference with antimicrobial | ||||

| Systemic UTI Follow‐up: range 1–30 days | 504 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | RR 1.12 (0.38 to 3.32) | Study population | |

| 20 per 1000 | 2 more per 1000 (12 fewer to 46 more) | ||||

| Symptomatic UTI Follow‐up: range 1–30 days | 5441 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | RR 0.49 (0.28 to 0.86) | Study population | |

| 58 per 1000 | 30 fewer per 1000 (42 fewer to 8 fewer) | ||||

| Serious adverse events Follow‐up: range 1–30 days | 630 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,d | RR approximately 1 | 0/326 participants receiving prophylactic antibiotics and 0/304 participants receiving control had a serious adverse event. | |

| Minor adverse events Follow‐up: range 1–30 days | 630 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | RR 2.82 (0.54 to 14.80) | Study population | |

| 3 per 1000 | 6 more per 1000 (2 fewer to 46 more) | ||||

| Localized UTI Follow‐up: range 1–30 days | 200 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,d | RR 1.00 (0.06 to 15.77) | Study population | |

| 10 per 1000 | 0 fewer per 1000 (9 fewer to 152 more) | ||||

| Bacterial resistance Follow‐up: range 1–30 days | 38 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,d,e | RR 1.73 (1.04 to 2.87) | Study population | |

| 406 per 1000 | 297 more per 1000 (16 more to 760 more) | ||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; UTI: urinary tract infection. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

aDowngraded for study limitations (–1) related to unclear or high risk of selection, performance, detection, and selective reporting bias.

bDowngraded for imprecision (–1) due to wide confidence intervals that included both no effect and increased risk.

cDowngraded for publication bias (–1) detected by asymmetry funnel plot.

dDowngraded for imprecision (–2) due to wide confidence interval around the pooled estimate which included no effect, small sample size, and few events.

eDowngraded for indirectness (–2) due to urine culture being performed after cystoscopy, and antibiotic prophylaxis would kill sensitive bacteria, thus leaving the percentage of bacterial resistance higher than the control group. As a result, even the pooled result could not deduce that antibiotic prophylaxis may have increased bacterial resistance from current results.

Background

Description of the condition

Cystoscopy is a diagnostic technique which allows urologists to inspect the interior lining of the bladder. It is usually performed in the outpatient clinic for the evaluation of haematuria (blood in the urine), the diagnosis of tumours of bladder, and assessment of urinary tract benign diseases. It was estimated that more than one million cystoscopies were performed from 2009 to 2015 in the USA (Henry 2018). Two types of cystoscopes are now currently used in daily clinical practice in urology (i.e. rigid cystoscope and flexible cystoscope). The main and most concerning disadvantage of cystoscopy is the risk of urinary tract infection (UTI) due to pre‐existing colonization or by introduction of bacteria at the time of the procedure, even with appropriate periprocedural preparation (Schaeffer 2012). The most frequently implicated uropathogens in UTIs after cytoscopy are Escherichia coli (E coli) (58%), Enterococcus (17.6%), and Klebsiella (8.8%) (Jimenez‐Pacheco 2012). UTI symptoms reflect an inflammatory response of the urothelium to bacterial invasion, which is associated with bacteriuria and pyuria (pus in the urine). Bacteriuria can be asymptomatic or symptomatic, which describes the absence or presence of symptoms such as fever, dysuria, urinary frequency, and suprapubic pain (Schaeffer 2012). The incidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria after cystoscopy ranges from 2.8% to 21% (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013). In contrast, symptomatic UTI is less common after cystoscopy (Herr 2014). Whether antimicrobial agents should be used to prevent a less than 5% mean risk of symptomatic UTI after cystoscopy is controversial (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Herr 2012; Herr 2014; Herr 2015; Johnson 2007; Rané 2001).

Description of the intervention

Antimicrobial prophylaxis is a brief course antibiotics before intervention, intended to minimize the risk of postprocedural infections resulting from diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and aminoglycosides are generally considered efficacious and ideal antibiotics for prophylaxis praxis in the urinary tract (Wolf 2008). People with risk factors (i.e. advanced age, anatomic anomalies of the urinary tract, poor nutritional status, smoking, chronic corticosteroid use, and immunodeficiency) are reported to be inclined to have UTI after transurethral procedures (Burke 2002; Wolf 2008). Since the majority of people with bladder cancer have one or more of these risk factors, antibiotics are usually given before each outpatient cystoscopy (Herr 2014). However, unnecessary antimicrobial prophylaxis should be avoided as overuse of antibiotics prior to cystoscopy may contribute to adverse effects and multidrug bacterial resistance (Gross 2007). Antibiotics are associated with adverse events, including nausea, emesis, diarrhoea, headache, delirium, hallucinations, convulsions, rash, and pruritus (Wolf 2008). Meanwhile, given the numerous cystoscopies performed every year worldwide, and people with bladder tumours need to undergo repetitive cystoscopy for surveillance, there are concerns about the development of antibiotic‐resistant bacteria when routine antimicrobial prophylaxis is used (Herr 2014). For example, for ciprofloxacin, the most widely used antibiotic before urological procedures for preventing UTI, resistant infections are reported to be more than 30% (Bootsma 2008; Fillon 2012). The frequency of infectious complications after cystoscopy in healthy people with sterile preoperative urine is low (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Herr 2014). In view of the very large number of cystoscopic examinations, the low infectious risk, and the high risk of contributing to increasing antimicrobial resistance, latest practice guidelines of the European Association of Urology (EAU) strongly recommend that antibiotic prophylaxis should not be considered for people undergoing cystoscopy (flexible or rigid) (Bonkat 2018). Despite evidence‐based recommendations against routine prophylactic antibiotics for cystoscopy, antibiotic use has increased over time, with implications for antibiotic resistance and changes in normal microbial flora (Henry 2018).

How the intervention might work

Prophylactic antibiotics in urological procedures should meet the following requirements: long half‐life, high renal elimination, no hepatic biotransformation, broad‐spectrum coverage for the most commonly encountered organisms, and good tolerance. They can be classified as bactericidal drugs (e.g. fluoroquinolones) and bacteriostatic drugs (e.g. sulphonamides) (Sorlozano 2014; Wolf 2008). The mechanism of action for antibiotics commonly used for the urinary system varies: those that inhibit DNA replication (fluoroquinolones), or cell wall synthesis (cephalosporins), or essential bacterial enzymes (aminoglycoside) have bactericidal activities; those that inhibit folate synthesis (trimethoprim and sulphonamides) are usually bacteriostatic (Finberg 2004). Oral administration is as effective as intravenous antibiotics with sufficient bioavailability. The EAU proposed that oral antibiotic prophylaxis be given approximately one hour before the intervention, which allows antibiotic prophylaxis to reach peak concentration at the time of procedure (Grabe 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

Previous studies have shown that a single dose of prophylactic antibiotic can significantly reduce the risk of bacteriuria after cystoscopy (Johnson 2007; Rané 2001). Johnson 2007 also suggested that one dose of oral antibiotic could not only lower costs, but also reduce the risks of drug resistance. In contrast, Garcia‐Perdomo 2013 found prophylactic antibiotics did not significantly reduce UTIs of people undergoing cystoscopy compared with placebo. Even for people with asymptomatic bacteriuria before cystoscopy, the rate of symptomatic UTI after cytoscopy was just 3.7% (Herr 2015). Herr 2014 indicated that urologists may need to accept a less than 5% risk of symptomatic UTI after cystoscopy and avoid routine antibiotic prophylaxis, which might help to reduce the percentage of resistant bacteria. Antimicrobial prophylaxis should be recommended in clinical practice when the potential benefit outweighs the risks and anticipated costs. Injudicious use of the antibiotics may cause adverse effects, as well as multidrug bacterial resistance, result in treatment failure, and increase healthcare costs. At present, there is an epidemic of bacterial resistance due to overuse of antibiotics, with the susceptibility rates of antibiotics to E coli ranging from about 60% to nearly 70% (cefuroxime 67.8% to 86.4%, ciprofloxacin 61.2% to 69.8%, and cotrimoxazole 55.0% to 65.5%) (Bakken 2004; Sorlozano 2014). To preserve the continued antibacterial activity of these antibiotic drugs, urologists need to ensure that antibiotic prophylaxis is given to participants who need to be treated. As a result, a comprehensive and rigorous Cochrane systematic review is needed to assess the benefits and adverse events of using antimicrobial agents before cystoscopy for prevention of symptomatic UTI. We used GRADE to assess the quality of evidence, which will help inform future guidelines on this topic.

Objectives

To assess the effects of antimicrobial agents compared with placebo or no treatment for prevention of UTI in adults undergoing cystoscopy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐RCTs. We did not consider cluster‐randomized or cross‐over design trials as they were not directly applicable to this topic. We did not consider non‐randomized studies given that these would likely provide only low or very low quality of evidence and we knew of the existence of many relevant RCTs.

Types of participants

We included adults (age 18 years or greater) who underwent outpatient rigid or flexible cystoscopy, with or without manipulation (e.g. biopsy, fulguration).

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies of people:

with a symptomatic UTI on the day of cystoscopy;

taking antibiotic prophylaxis for other health conditions (e.g. prosthetic cardiac valve, vascular);

currently taking other medication that may interact with antibiotics;

with allergies to antibiotics;

who are immunocompromised.

Types of interventions

We included the comparison of any prophylactic antibiotic versus placebo, no treatment, or other non‐antibiotic prophylaxis. There were no restrictions on the dose, frequency, formulation, duration, or mode of administration of the antibiotics. We investigated the following comparisons of experimental intervention versus comparator intervention.

Experimental intervention

Antibiotic prophylaxis.

Comparator interventions

Placebo.

No treatment.

Other non‐antibiotic prophylaxis.

Comparisons

Antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo or no treatment or other non‐antibiotic prophylaxis.

We allowed concomitant interventions that were the same in the experimental and comparator groups to establish fair comparisons.

Types of outcome measures

Measurement of outcomes assessed in this review was not used as an eligibility criterion.

Primary outcomes

Systemic UTI (sepsis, fever 38 °C or greater, and documented bacteruria). Bacteruria was defined as midstream urine culture with more than 105 colony‐forming units (CFU)/mL of uropathogens, or greater than 104 CFU/mL of a single organism cultured, or greater than 104 CFU/mL uropathogens in a midstream sample of urine in men, catheterized urine culture 102 CFU/mL or greater.

Symptomatic UTI defined as a composite of both systemic and localized UTI.

Serious adverse events (e.g. Stevens‐Johnson syndrome, anaphylaxis, renal toxicity, and hepatotoxicity).

Secondary outcomes

Minor adverse events (nausea, vomiting, dizziness).

Localized UTI (local symptoms such as urinary irritative symptoms, dysuria, suprapubic pain, and documented bacteruria).

Asymptomatic bacteruria (documented bacteruria with no local or systemic symptoms).

Bacterial resistance (urine bacteria that was resistant to primary antibiotic treatment).

Method and timing of outcome measurements

In routine clinical practice, methods and criteria of urine collection and culture may vary. In general, a urine culture before cystoscopy should be taken within one week and urine culture after cytoscopy should be performed within one month, except for participants who were required to have urine culture at the discretion of physician during follow‐up.

Postcystoscopy, a follow‐up questionnaire, telephone call, or appointment should have occurred within three months to determine if a participant was symptomatic or experiencing adverse effects.

Main outcomes for 'Summary of findings' table

We presented a 'Summary of findings' table reporting the following outcomes listed according to priority.

Systemic UTI.

Symptomatic UTI.

Serious adverse events.

Minor adverse events.

Localized UTI.

Bacterial resistance.

Search methods for identification of studies

We performed a comprehensive search with no restrictions on the language of publication or publication status. Studies reported in different languages were translated by review authors with the help of Google (https://translate.google.com/). We reran all searches within three months prior to publication and screened the results for eligible studies.

Electronic searches

We searched the following sources from inception of each database to 4 February 2019.

-

The Cochrane Library (see Appendix 1 for search strategy):

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE);

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA).

MEDLINE (PubMed; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed; see Appendix 2 for search strategy).

Embase (Elsevier; see Appendix 3 for search strategy).

LILACS (lilacs.bvsalud.org/en/; see Appendix 4 for search strategy).

CINAHL (EBSCOhost; see Appendix 5 for search strategy).

We searched the following.

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov/; see Appendix 6 for search strategy).

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch/), a meta‐register of studies with links to the numerous other trials registers (see Appendix 7 for search strategy).

Searching other resources

We tried to identify other potentially eligible trials or ancillary publications by searching the reference lists of retrieved included trials, reviews, meta‐analyses, and health technology assessment reports. We searched the proceedings of meetings from the American Urological Association (AUA; www.auanet.org/) and EAU (www.europeanurology.com/search/advanced) from April 2009 to May 2018.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

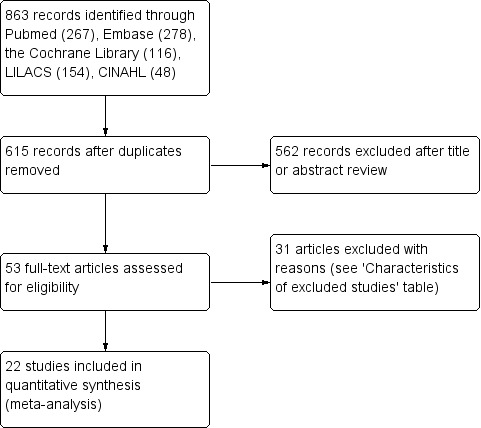

We used the reference management software EndNote to identify and remove potential duplicate records. Two review authors (SXZ, ZSZ) independently scanned the abstract, title, or both, of remaining records retrieved, to determine which studies should be further assessed. Two review authors (SXZ, ZSZ) investigated all potentially relevant records as full text, mapped records to studies, and classified studies as included studies, excluded studies, studies awaiting classification, or ongoing studies, in accordance with the criteria for each provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). We resolved any discrepancies through consensus or recourse to a third review author (YB). If resolution of a disagreement was not possible, we designated the study as 'awaiting classification' and we contacted study authors for clarification. We documented reasons for exclusion of studies that might have reasonably been expected to be included in the review in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We presented an adapted PRISMA flow diagram showing the process of study selection (Liberati 2009; Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

We developed a dedicated data abstraction form that we have pilot tested.

For studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, two review authors (SXZ, ZSZ) independently extracted the following information, which we provided in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study design.

Accrual dates.

Study settings and country.

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Participant details, baseline demographics.

Number of participants by study and by study arm.

Details of antibiotic prophylaxis and comparator interventions such as dose, route, frequency, and duration.

Definitions of relevant outcomes such as bacteriuria, symptomatic UTI, and method and timing of outcome measurement, as well as any relevant subgroups.

Details of outcomes relevant to this review, including the incidence of symptomatic UTI, asymptomatic bacteruria, adverse effects of antibiotics, bacterial resistance.

Study funding sources.

Declarations of interest by primary investigators.

We extracted outcome data relevant to this review as needed for calculation of summary statistics and measures of variance. For dichotomous outcomes, we attempted to obtain numbers of events and totals for population of a 2 × 2 table, as well as summary statistics with corresponding measures of variance. For continuous outcomes, we attempted to obtain means and standard deviations or data necessary to calculate this information.

We resolved any disagreements by discussion, or, if required, by consultation with a third review author (YB).

We provided information, including trial identifiers, about potentially relevant ongoing studies in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

We attempted to contact authors of included studies to obtain key missing data as needed.

Dealing with duplicate and companion publications

In the event of duplicate publications, companion documents, or multiple reports of a primary study, we maximized the yield of information by mapping all publications to unique studies and collating all available data and used the most complete data‐set aggregated across all known publications. If there was any uncertainty, we gave priority to the publication reporting the longest follow‐up associated with our primary or secondary outcomes.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SXZ, ZSZ) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study. We resolved disagreements by consensus, or by consultation with a third review author (YB).

We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane tool (Higgins 2011b). We assessed the following domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting.

Other sources of bias.

We judged 'Risk of bias' domains as 'low risk', 'high risk', or 'unclear risk' and evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b). We presented a 'Risk of bias' summary figure to illustrate these findings.

For performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel) and detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), we evaluated the risk of bias separately for each outcome, and we grouped outcomes according to whether measured subjectively or objectively when reporting our findings in the 'Risk of bias' table.

We also assessed attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) on an outcome‐specific basis, and grouped outcomes with similar judgements when reporting our findings in the 'Risk of bias' tables.

We further summarized the risk of bias across domains for each outcome in each included study, as well as across studies and domains for each outcome.

We defined the following endpoints as subjective outcomes.

Symptomatic UTI (systemic UTI or localized UTI), asymptomatic bacteruria, and adverse events.

We defined the following endpoint as objective outcomes.

Bacterial resistance defined as urine culture.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual participant. Should we have identified trials with more than two intervention groups for inclusion in the review, we planned to handle these in accordance with guidance provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011c).

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to obtain missing data from study authors to perform intention‐to‐treat analyses; if data were not available, we performed available‐case analyses. We tried to contact study authors of included trials to obtain critical missing data (e.g. dropouts, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals, randomization method). We received replies from Garcia‐Perdomo 2013 and Johnson 2007, and we received no reply or no email address available for contacting the corresponding author for further information in other studies, details were shown in the notes of Characteristics of included studies. We did not impute missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the event of excessive heterogeneity unexplained by subgroup analyses, we did not report outcome results as the pooled effect estimate in a meta‐analysis, but provided a narrative description of the results of each study.

We identified heterogeneity (inconsistency) through visual inspection of forest plots to assess the amount of overlap of CIs, and the I2 statistic, which quantifies inconsistency across studies to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003); we interpreted the I2 statistic as follows:

0% to 40%: may not be important;

30% to 60%: may indicate moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may indicate substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

If we found heterogeneity, we attempted to determine possible reasons for it by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

Assessment of reporting biases

We attempted to obtain study protocols to assess for selective outcome reporting.

We used funnel plots to assess small‐study effects when we included 10 or more studies investigating a particular outcome. Several explanations could be offered for the asymmetry of a funnel plot, including true heterogeneity of effect with respect to trial size, poor methodological design (and hence bias of small trials), and publication bias (Kicinski 2015). Therefore, we interpreted results carefully.

Data synthesis

We summarized data using a random‐effects model. We interpreted random‐effects meta‐analyses with due consideration of the whole distribution of effects. In addition, we performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). For dichotomous outcomes, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method. We used Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) software to perform analyses (Review Manager 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity, and planned to carry out subgroup analyses with investigation of interactions for the primary outcomes.

Rigid cystoscopy versus flexible cystoscopy, as they may be associated with different degrees of mucosal trauma.

Participants with manipulation (biopsy, fulguration, etc.) at cystoscopy versus those without manipulation.

Participants with presence of asymptomatic bacteriuria before cystoscopy versus those with no presence.

Men versus women.

We used the test for subgroup differences in Review Manager 5 to compare subgroup analyses (Review Manager 2014).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect sizes.

Restricting the analysis by taking into account risk of bias, by excluding studies at 'high risk' or 'unclear risk'.

'Summary of findings' table

We presented the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome according to the GRADE approach, which took into account five criteria related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias), and external validity (such as directness of results) (Guyatt 2008). For each comparison, two review authors (SXZ, ZSZ) independently rated the quality of evidence for each outcome as 'high', 'moderate', 'low', or 'very low' using GRADEproGDT; we resolved discrepancies by consensus, or, if needed, by arbitration by a third review author (YB). For each comparison, we presented a summary of the evidence for the main outcomes in a 'Summary of findings' table, which provided key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of the effect, in relative terms and absolute differences for each relevant comparison of alternative management strategies; numbers of participants and studies addressing each important outcome; and the rating of the overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome (Guyatt 2011; Schünemann 2011). We presented results in a narrative 'Summary of findings' table when meta‐analysis was not possible.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The flow of literature through the assessment process is shown in Figure 1. The electronic database search identified 615 citations after removal of duplicates, of which we selected 53 studies for full‐text review (searched 4 February 2019). We finally included 22 trials in the review (see Characteristics of included studies table) and excluded 31 trials that did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). We identified no unpublished studies that met the criteria for inclusion.

Included studies

The review included 22 studies, 20 RCTs and two quasi‐RCTs (Rané 2001; Vasanthakumar 1990). The trials published between 1971 to 2017 in five languages (English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Chinese), and took place in 11 countries: the UK (Hares 1981; Hart 1980; Johnson 2007; MacDermott 1988; Rané 2001; Vasanthakumar 1990), the USA (Blackard 1972; Manson 1988; Mendoza 1971), Spain (Asuero 1989; Jimenez 1993; Jimenez‐Pacheco 2012; Martinez Rodriguez 2017), Turkey (Cam 2009; Soydan 2012), Colombia (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013), Singapore (Goh 1982), France (Karmouni 2001), Brazil (Rodrigues 1994), China (Si 1997), Japan (Tsugawa 1998), and New Zealand (Wilson 2005). We have provided further details of the included studies in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Eight out of 22 trials included participants with asymptomatic bacteriuria or negative urine culture before cystoscopy for analysis (Asuero 1989; Blackard 1972; Hart 1980; Johnson 2007; Martinez Rodriguez 2017; Rané 2001; Soydan 2012; Wilson 2005), 13 trials excluded participants with asymptomatic bacteriuria before cystoscopy for analysis, and the information was unclear in one trial due to lack of information (Vasanthakumar 1990).

Five trials used flexible cystoscope for examination (Jimenez‐Pacheco 2012; Johnson 2007; Martinez Rodriguez 2017; Rané 2001; Wilson 2005); five trials used rigid cystoscope for examination (Cam 2009; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Karmouni 2001; Si 1997; Tsugawa 1998). We contacted the author of one trial for information about the type of cystoscope (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013). Twelve trials did not describe the type of cystoscope for examination and we were unable to contact these authors to get further information because we could not find their email contact address. The trials that did not describe the type of cystoscope were published between 1971 to 1994, and probably used rigid cystoscope.

Eight trials included participants with or without manipulation (biopsy, fulguration, etc.) during cystoscopy (Asuero 1989; Cam 2009; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Hares 1981; Johnson 2007; MacDermott 1988; Si 1997; Soydan 2012), five trials only included participants without manipulation during cystoscopy (Blackard 1972; Manson 1988; Martinez Rodriguez 2017; Rané 2001; Wilson 2005), and there was no information about manipulation during cystoscopy in the remaining nine trials.

Excluded studies

The most common reasons for exclusion was trial design (retrospective studies and non‐randomized trials). Details of excluded studies are given in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

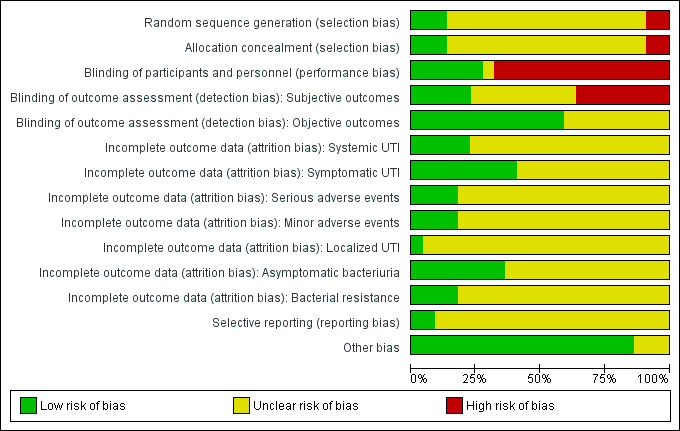

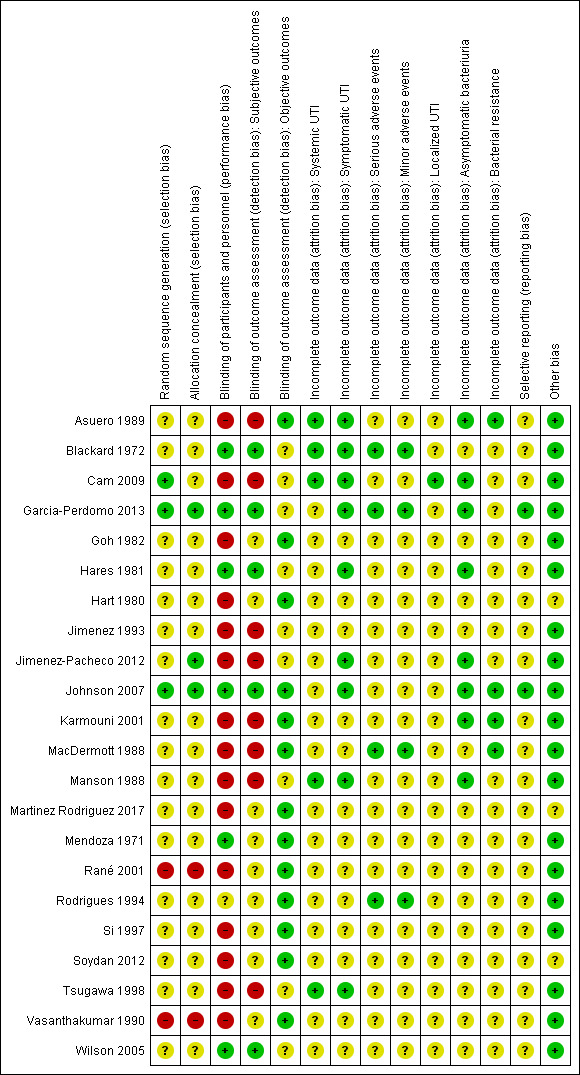

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2 for a summary of the risk of bias assessments for each trial and Figure 3 for a summary of the risk of bias assessments for the trials together. The 'Risk of bias' table within the Characteristics of included studies table gives detailed information.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Seventeen out of 22 trials were at unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation, three out of the 22 trials were at low risk for random sequence generation (Cam 2009; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Johnson 2007), and two trials used a quasi‐randomized method of sequence generation and were at high risk for random sequence generation (Rané 2001; Vasanthakumar 1990).

Allocation concealment

Seventeen out of 22 trials were at unclear risk of allocation concealment, three trials were at low risk of allocation concealment (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Jimenez‐Pacheco 2012; Johnson 2007), two trials used a quasi‐randomized method of sequence generation and were at high risk of allocation concealment (Rané 2001; Vasanthakumar 1990).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

Fifteen out of 22 trials were at high risk of performance bias due to non‐blinded study design, six trials had low risk of performance bias by blinding both participants and personnel (Blackard 1972; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Hares 1981; Johnson 2007; Mendoza 1971; Wilson 2005), and one trial was at unclear risk based on the data provided in the manuscript (Rodrigues 1994).

Blinding of outcome assessment

Subjective outcomes

Subjective outcomes were more likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. Due to non‐blinded study design, eight out of 22 trials were at high risk of detection bias for subjective outcomes such as symptomatic (systemic or localized, or both) UTI, adverse events caused by antibiotics, and asymptomatic bacteriuria (Asuero 1989; Cam 2009; Jimenez 1993; Jimenez‐Pacheco 2012; Karmouni 2001; MacDermott 1988; Manson 1988; Tsugawa 1998). Five trials showed low risk of detection bias for subjective outcomes due to proper blinding (Blackard 1972; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Hares 1981; Johnson 2007; Wilson 2005). The remaining trials were at unclear risk of bias because these subjective outcomes were not reported.

Objective outcomes

Four trials reported bacterial resistance assessed by urine culture (Asuero 1989; Johnson 2007; Karmouni 2001; MacDermott 1988). Ten trials reported bacteriuria (simply assessed by urine examination but without differentiating whether participants had symptoms or not) as their primary outcome (Goh 1982; Hart 1980; MacDermott 1988; Martinez Rodriguez 2017; Mendoza 1971; Rané 2001; Rodrigues 1994; Si 1997; Soydan 2012; Vasanthakumar 1990). We considered risk of detection bias for these objective outcomes to be low.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed risk of bias for incomplete outcome data on an outcome‐specific basis (see Characteristics of included studies table).

Systemic UTI: five trials reported systemic UTIs and the risk of attrition bias was low, because these trials had no postrandomization losses or few participants were excluded postrandomization, and the exclusions and reasons for exclusions were balanced between groups (Asuero 1989; Blackard 1972; Cam 2009; Manson 1988; Tsugawa 1998).

Symptomatic UTI: nine trials investigated symptomatic UTI and were at low risk of attrition bias (Asuero 1989; Blackard 1972; Cam 2009; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Hares 1981; Jimenez‐Pacheco 2012; Johnson 2007; Manson 1988; Tsugawa 1998). These trials had no postrandomization losses or few participants were excluded postrandomization, and the exclusions and reasons for exclusions were balanced between groups. We judged Wilson 2005 at unclear risk of attrition bias for symptomatic UTI, because 29 out of 263 participants were excluded because of incomplete data acquisition. There was no information about whether these withdrawals were before or after randomization or from which group the withdrawals came from. The study was stopped and interim analysis was performed because of low recruitment rate. We judged Jimenez 1993 at unclear risk of attrition bias for symptomatic UTI, because 2284 participants were randomized, 2172 participants were finally included for analysis of this outcome, 105 participants were excluded after randomization due to failure to meet inclusion criteria, and the reason for seven participants that were not included for analysis was not given.

Serious adverse events: four trials reported adverse events (serious and minor adverse events). The risk of attrition bias was low, because these trials had no postrandomization losses or few participants were excluded postrandomization, and the exclusions and reasons for exclusions were balanced between groups (Blackard 1972; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; MacDermott 1988; Rodrigues 1994).

Minor adverse events: four trials reported minor adverse events (Blackard 1972; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; MacDermott 1988; Rodrigues 1994). The risk of attrition bias was low, because these trials had no postrandomization losses or few participants were excluded postrandomization, and the exclusions and reasons for exclusions were balanced between groups.

Localized UTI: one trial reported localized UTI (Cam 2009). All participants included were analyzed for this outcome and the risk of attrition bias was low.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria: eight trials were at low risk of attrition bias for asymptomatic bacteriuria (Asuero 1989; Cam 2009; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Hares 1981; Jimenez‐Pacheco 2012; Johnson 2007; Karmouni 2001; Manson 1988). Two trials were at unclear risk of attrition bias for asymptomatic bacteriuria (Jimenez 1993; Wilson 2005) (reasons were mentioned above).

Bacterial resistance: four trials reported bacterial resistance. The risk of attrition bias was low because these trials had no postrandomization losses or few participants were excluded postrandomization, and the exclusions and reasons for exclusions were balanced between groups (Asuero 1989; Johnson 2007; Karmouni 2001; MacDermott 1988).

Selective reporting

We assessed 20 out of 22 trials to be at an unclear risk of reporting bias, although data reported on all outcomes specified in methods section, there was no access to trial protocol/registration to further assess selective reporting in these trials. Protocol documents of two trials were available for analysis, and their outcomes were reported in line with the protocol (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Johnson 2007).

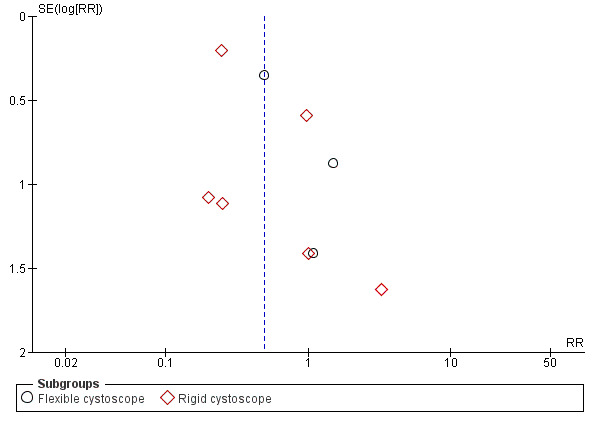

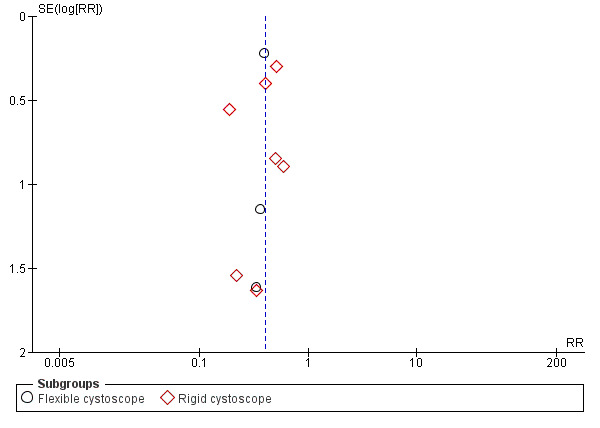

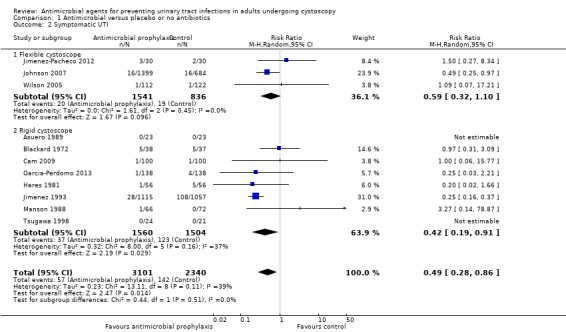

The publication bias was tested by funnel plots for outcomes of symptomatic UTI (Figure 4) and asymptomatic bacteriuria (Figure 5), there appear to have asymmetry which suggested publication bias.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, outcome: 1.2 Symptomatic urinary tract infection.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, outcome: 1.5 Asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Other potential sources of bias

There were no other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Antibiotic prophylaxis versus placebo or no treatment or other non‐antibiotic prophylaxis

Primary outcomes

See Table 1.

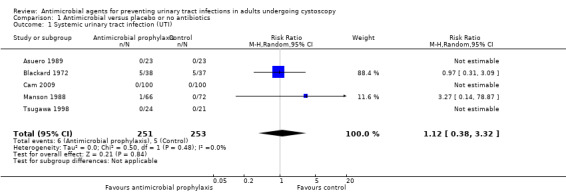

Systemic urinary tract infection

Five trials with 504 participants contributed to the analysis of systemic UTI (Asuero 1989; Blackard 1972; Cam 2009; Manson 1988; Tsugawa 1998). The incidence of systemic UTI was low in both antibiotic prophylaxis group (6/251, 2.39%) and control group (5/253, 1.98%). We found low‐quality evidence that antibiotic prophylaxis may have little or no effect on the risk of systemic UTI compared with the control group (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.38 to 3.32; Analysis 1.1; Figure 6). We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for study limitations and by one level for imprecision. This corresponds to two more people (95% CI 12 fewer to 46 more) per 1000 people having a systemic UTI when provided with antibiotic prophylaxis.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, Outcome 1 Systemic urinary tract infection (UTI).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, outcome: 1.1 Systemic urinary tract infection.

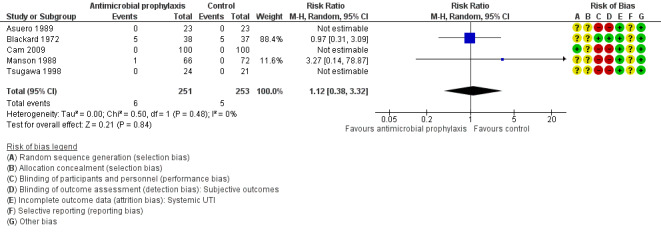

Symptomatic urinary tract infection

Six trials contributed to the analysis of symptomatic UTI (the six trials reported symptomatic UTI as their primary outcome without distinguishing systemic or localized UTI) (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Hares 1981; Jimenez 1993; Jimenez‐Pacheco 2012; Johnson 2007; Wilson 2005). Five trials reported systemic UTI or localized UTI, or both, separately as mentioned above (Asuero 1989; Blackard 1972; Cam 2009; Manson 1988; Tsugawa 1998). We pooled data from the 11 trials, with 5441 participants, for the analysis of symptomatic UTI. When compared to control group, participants receiving prophylactic antibiotics had fewer symptomatic UTIs (57/3101, 1.84%) than control group (142/2340, 6.07%).

Antibiotic prophylaxis may reduce the incidence of symptomatic UTI (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.86; low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.2; Figure 7). We downgraded one level for study limitations and one level for publication bias. This corresponds to 30 fewer people (95% CI 42 fewer to 8 fewer) per 1000 people having a symptomatic UTI when provided with antibiotic prophylaxis.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, Outcome 2 Symptomatic UTI.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, outcome: 1.2 Symptomatic urinary tract infection.

Serious adverse events

Four trials with 630 participants reported adverse effects caused by antibiotics prophylaxis, but all of them were minor adverse events, that is, 0/326 participants in the antibiotic prophylaxis group and 0/304 participants in the control group had serious adverse events (Blackard 1972; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; MacDermott 1988; Rodrigues 1994). We could not calculate an absolute effect estimate but our best estimate is that there may be no difference (RR approximately 1; very low‐quality evidence), but we were very uncertain of this finding. We downgraded the quality of evidence one level for study limitations and one level for imprecision. We were unable to calculate an absolute effect size measure.

Secondary outcomes

See Table 1.

Minor adverse events

Four trials with 630 participants contributed to the analysis of minor adverse events caused by prophylactic antibiotic (Blackard 1972; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; MacDermott 1988; Rodrigues 1994). We found low‐quality evidence that prophylactic antibiotic may result in little or no difference in minor adverse events compared with placebo (RR 2.82, 95% CI 0.54 to 14.80; Analysis 1.3; Figure 8). We downgraded the quality of evidence one level for study limitations and one level for imprecision. This corresponds to six more (95% CI 2 fewer to 46 more) people with minor adverse events.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, Outcome 3 Minor adverse effects.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, outcome: 1.3 Minor adverse effects.

Localized urinary tract infection

We found one trial that contributed to the analysis of localized UTI (Cam 2009). Cam 2009 reported 1/100 localized UTI in the antibiotic prophylaxis group and 1/100 in the control group, Very low‐quality evidence suggests that antibiotic prophylaxis have little or no effect on localized UTI compared with control group (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.77; Analysis 1.4; Figure 9), but we are very uncertain of this finding. We downgraded the quality of evidence one level for study limitations and two levels for imprecision. This corresponds to zero more people (95% CI 9 fewer to 152 more) per 1000 people having a localized UTI when provided with antibiotic prophylaxis.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, Outcome 4 Localized UTI.

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, outcome: 1.4 Localized urinary tract infection.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

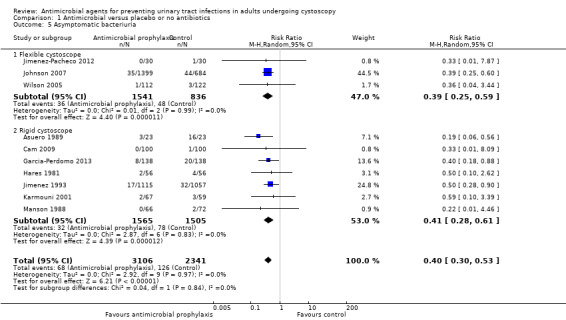

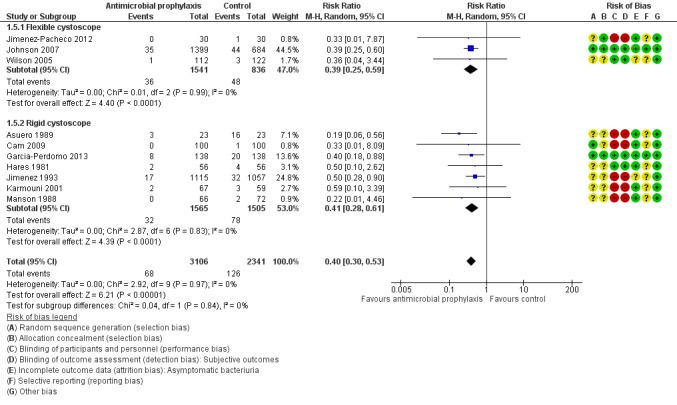

Ten trials with 5447 participants contributed to the analysis of asymptomatic bacteriuria (Asuero 1989; Cam 2009; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Hares 1981; Jimenez 1993; Jimenez‐Pacheco 2012; Johnson 2007; Karmouni 2001; MacDermott 1988; Wilson 2005). Asymptomatic bacteriuria was less frequent in the antibiotic prophylaxis group (68/3106, 2.19%) compared to control group (126/2341, 5.38%). Based on low‐quality evidence, antibiotic prophylaxis may reduce asymptomatic bacteriuria (RR 0.40, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.53; Analysis 1.5; Figure 10). We downgraded the quality of evidence one level for study limitations and one level for publication bias.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, Outcome 5 Asymptomatic bacteriuria.

10.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, outcome: 1.5 Asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Bacterial resistance

Four trials with 2444 participants reported bacterial resistance; however, only 89 participants contributed to the analysis (Asuero 1989; Johnson 2007; Karmouni 2001; MacDermott 1988). Only results from two studies were suitable for pooling (Asuero 1989; MacDermott 1988).

In Asuero 1989, 9/16 (56.3%) participants with bacteriuria in the control group showed no sensitivity to antibiotic, and 3/3 (100%) participants with bacteriuria showed no sensitivity to antibiotic in the treatment group post cystoscopy. Johnson 2007 reported organism was resistant to the antibiotic in 9/22 (40.1%) participants given trimethoprim and in 4/28 (14.3%) participants given ciprofloxacin post cystoscopy; however, the incidence of bacterial resistance in the control group was not available. Karmouni 2001 found one participant had multiresistant bacteria post cystoscopy, but did not specify whether they were in the intervention or control group. MacDermott 1988 reported 4/16 (25.0%) participants with bacteriuria in the control group, and 2/3 (66.7%) participants with bacteriuria in the treatment group showed no sensitivity to antibiotic post cystoscopy.

The results from Asuero 1989 and MacDermott 1988 were able to be pooled. Antibiotic prophylaxis may increase bacterial resistance (RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.87; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.6; Figure 11), but we are very uncertain of this finding. We downgraded the quality of evidence one level for study limitations, and two levels for indirectness and imprecision (Table 1). We downgraded for indirectness because urine cultures were performed after cystoscopy, and antibiotic prophylaxis would kill sensitive bacteria, thus leaving the percentage of bacterial resistance rate higher than that of the control group. This finding corresponds to 297 more people (16 more to 760 more) with bacterial resistance.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, Outcome 6 Bacterial resistance.

11.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, outcome: 1.6 Bacterial resistance.

Antibiotic prophylaxis versus other non‐antibiotic prophylaxis

We found no studies comparing antibiotic prophylaxis versus other non‐antibiotic prophylaxis.

Subgroup analysis

Rigid cystoscopy versus flexible cystoscopy

For systemic UTI and serious adverse events, we were unable to perform other planned subgroup analyses due to the limited number of studies included and paucity of data for primary outcomes.

For symptomatic UTI, eight trials with 3064 participants underwent rigid cystoscopy (Asuero 1989; Blackard 1972; Cam 2009; Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Hares 1981; Jimenez 1993; Manson 1988; Tsugawa 1998), and we found a reduction in symptomatic UTI in the antibiotic prophylaxis group in studies using rigid cystoscopy (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.91; P = 0.03; Analysis 1.2; Figure 7). Three trials with 2377 participants underwent flexible cystoscopy (Jimenez‐Pacheco 2012; Johnson 2007; Wilson 2005), but the difference regarding symptomatic UTI was not observed in these studies using flexible cystoscopy (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.10; P = 0.10; Figure 7). However, the subgroup interaction test indicated no evidence of a subgroup effect (Chi2 = 0.44, P = 0.51, I2 = 0%).

Participants with manipulation at cystoscopy versus those without manipulation

We were unable to perform the subgroup analyses due to paucity of data for this comparison.

Participants with presence of asymptomatic bacteriuria before cystoscopy versus those with no presence

We were unable to perform the subgroup analyses due to paucity of data for this comparison.

Men versus women

We were unable to perform the subgroup analyses due to paucity of data for this comparison.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not conduct sensitivity analyses for systemic UTI and serious adverse events, as we judged none of studies included in these comparison to be at low risk of bias overall.

We performed sensitivity analysis for symptomatic UTI in which we included only two studies with low risk of bias (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Johnson 2007). The pooled result was similar, indicating that antibiotic prophylaxis may have reduced the incidence of symptomatic UTI compared with control group (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.89; P = 0.02).

Discussion

Summary of main results

All findings of this review were limited to the comparison of antibiotics prophylaxis versus placebo or no prophylaxis (without use of placebo). We found no comparisons of antibiotic prophylaxis versus other forms of non‐antibiotic prophylaxis.

We found that antibiotic prophylaxis may reduce UTIs when analyzed as symptomatic UTI (defined as the composite of systematic UTI and localized UTI) based on low‐quality evidence. It may have little to no effect on each of these outcomes when analyzed in isolation based on low‐quality evidence (systemic UTI) and very low‐quality evidence (localized UTI). Antibiotics prophylaxis may have little or no effect on serious and minor adverse events, based on low‐quality evidence (serious) and very low‐quality evidence (minor). Antibiotic prophylaxis may increase bacterial resistance but we are very uncertain of this finding based on very low‐quality evidence.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Most trials pertained to antibiotics and regimens that are no longer used in current daily clinical practice, and were performed in the 1980s and 1990s; this limits the applicability of our findings. Although the settings of included trials varied, they do reflect common situations in the clinical practice and therefore the evidence appears applicable in that regard.

There was considerable clinical heterogeneity meaning that the studies used different types of cystoscopes (flexible versus rigid), included manipulation or not, were performed in men and women with their different anatomy, and assessed for asymptomatic bacteriuria before cystoscopy or not. We were unable to complete many of our preplanned subgroup analysis to explore the observed heterogeneity because there were insufficient data from the included studies and most of the studies did not analyze these subgroups individually. We attempted to contact authors for additional clarifying information but only received replies from two of them (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Johnson 2007). Eleven trials that were published between 1971 to 1994 did not specify the type of cystoscope for examination; they were classified as rigid cystoscope in the subgroup analysis because flexible cystoscope was not widely used then, and some trials used spinal or general anaesthesia during procedure which was uncommon for flexible cystoscopy.

Although no serious adverse event was reported among studies, it should be noted that it was not possible to determine severe adverse events from such relatively small sample sizes, and the incidence and types of severe adverse events also varied between different antibiotics. Meropol 2008 reported that the incidence of any serious adverse events of ciprofloxacin ranged from 3.6 per 100,000 person‐days to 16.9 per 100,000 person‐days. Thornhill 2015 found that with amoxicillin there were no fatal reactions per million prescriptions and 22.62 non‐fatal reactions per million prescriptions.

Bacterial resistance analysis was only performed for few participants with positive urine culture in included studies, as a result the included trials were not well suited to show the association between antibiotic prophylaxis and bacterial resistance.

Quality of the evidence

We graded the quality of the evidence based on the GRADE approach (Table 1). We found that the level of evidence ranged from very low to low for all outcomes. The most common reasons for downgrading the quality of evidence was risk of bias due to study limitations and imprecision of data due to wide CI and low event rates. Figure 2 and Figure 3 showed that unclear risk of biases were often due to lack of reporting methodology and high risk of biases were often due to non‐blinded study design.

Potential biases in the review process

We reduced potential biases by using a comprehensive search strategy; however, it is possible that we could have missed trials that were not indexed in the commonly used databases. Should any such studies be identified, we will include them in updates of this review. We considered only RCTs for inclusion in this review. Eleven trials reported bacteriuria as the primary outcome without distinguishing whether they were accompanied by symptoms or not (Blackard 1972; Goh 1982; Hart 1980; MacDermott 1988; Martinez Rodriguez 2017; Mendoza 1971; Rané 2001; Rodrigues 1994; Si 1997; Soydan 2012; Vasanthakumar 1990). Bacteriuria was not consistently defined as prespecified for our primary and secondary outcomes. We considered pooling these trials that reported bacteriuria in such unspecified manner with symptomatic UTI or asymptomatic bacteriuria but concluded that this might result in misleading results. As a result, although these 11 trials were included for analysis of methodological quality, their data were not included for meta‐analysis. Two RCTs were published as conference abstracts (Martinez Rodriguez 2017; Soydan 2012), and we were unable to obtain additional information from the authors to better evaluate their methodological quality and to extract useful data. Since the boundaries between a localized UTI and a systemic UTI may be fluid in clinical practice and both matter to participants and their providers, we added symptomatic UTI as a primary outcome post hoc, because we considered this was also a patient‐important outcome.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We identified two published systematic reviews that addressed the topic of antibiotic prophylaxis in cystoscopy (Carey 2015; Garcia‐Perdomo 2015).

Carey 2015 pooled results from nine studies and found that the control group was more likely to have symptomatic UTIs post flexible cystoscopy than the antibiotic group. The number needed to treat to prevent one episode was 26. In the present review, we found antibiotic prophylaxis was unlikely to reduce the incidence of symptomatic UTI compared with the control group post flexible cystoscopy (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.10; P = 0.10; Figure 7). Carey 2015 considered three trials using flexible cystoscope for cystoscopy in their review (Garcia‐Perdomo 2013; Jimenez 1993; Mendoza 1971). However, we classified the trials conducted by Jimenez 1993 and Mendoza 1971 as rigid cystoscope in the present study because flexible cystoscope was not widely used at that time, and we obtained the information from the author of Garcia‐Perdomo 2013 that they used a rigid cystoscope in their study.

Garcia‐Perdomo 2015 included five trials for the analysis of symptomatic UTI and found that antibiotic prophylaxis might have reduced the incidence of symptomatic UTI (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.89; P = 0.02). In the present review, we found 11 trials contributed to the analysis of symptomatic UTI, and results also showed that antibiotic prophylaxis might have reduced symptomatic UTI, subgroup analysis suggested that antibiotic prophylaxis might have been effective in participants undergoing rigid cystoscopy, but appeared to be not effective for flexible cystoscopy; however, the subgroup interaction test indicated no evidence of a subgroup effect. We identified two prospective non‐randomized trials by Cano‐Garcia 2016 and Herr 2014 that suggested that antibiotic prophylaxis before flexible cystoscopy did not appear necessary for participants who had no clinical signs or symptoms of acute UTI.

The present systematic review associated with this topic was the only one with an a priori protocol and performed strictly along with the PRISMA principle, and a comprehensive search that included studies irrespective of language and publication status. We also use GRADE to rate the quality of the evidence.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Antibiotic prophylaxis may lead to a small reduction of urinary tract infections (UTIs) but only when considering systemic and localized UTIs together. This corresponds to 30 fewer (95% confidence interval (CI) 42 fewer to 8 fewer) symptomatic UTIs per 1000 people. Antibiotic prophylaxis does not appear to increase serious adverse events or minor adverse events, although we are very uncertain about the latter finding. We are also very uncertain whether it increases bacterial resistance.

Implications for research.

Additional high‐quality, adequately powered randomized controlled trials (RCTs) using proper blinding method, reporting outcomes in subgroups stratified by different types of cystoscope (rigid versus flexible), and by different risk of UTI (e.g. with asymptomatic bacteriuria before cystoscopy, manipulation is needed during cystoscopy) may help to clarify the ideal strategy of antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic UTI (systemic or localized UTI, or both) post cystoscopy, and provide a more definitive and robust evidence for this comparison. The incidence of severe adverse events of antibiotics is low (Meropol 2008; Thornhill 2015). Although there was no severe adverse event caused by antibiotic prophylaxis in the current review, future prospective observational studies with large sample size and standardized adverse reporting criteria will better inform this issue.

Notes

Parts of the Methods section and Appendix 1 of this review were based on a standard template developed by the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group that has been modified and adapted for use by the Cochrane Urology Group.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Chunbo Li, Director of the Chinese Satellite of Cochrane Schizophrenia Group, who kindly gave us advice on how to perform this systematic review and meta‐analysis. We wish to thank the staff and editors (Philipp Dahm, Molly Neuberger, Alea Miller, Robert Lane, Jim Tacklind, and Kourosh Afshar) of the Cochrane Urology Group for feedback to the draft protocol and review. We would like to thank Tommaso Cai, Magnus Grabe, and Harry Herr for their valuable comments to improve the draft protocol. We would also like to thank Franck Bruyere, Harry Herr, and Robert Pickard for their valuable comments to improve the manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix 1. The Cochrane Library search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Cystoscopy] explode all trees

#2 cystoscop* or cystourethroscop* or urethrocystoscop*

#3 #1 or #2

#4 MeSH descriptor: [Antibiotic Prophylaxis] explode all trees

#5 Antibioti* or anti‐bacterial* or antibacterial* or Probioti* or ofloxacin or levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin or metronidazole or azithromycin or clarithromycin or erythromycin or amoxicillin or penicillin or loracarbef or ceph* or trimethoprim or vancomycin or augmentin or chemoprophylaxis or Quinolone*

#6 #4 or #5

#7 #3 and #6

Appendix 2. MEDLINE (PubMed) search strategy

((((((((((("Controlled Clinical Trial" [Publication Type]) OR "Randomized Controlled Trial" [Publication Type]) OR (((((groups[Title/Abstract]) OR trial[Title/Abstract]) OR drug therapy[MeSH Subheading]) OR placebo[Title/Abstract]) OR random*[Title/Abstract])))) OR controll*[Title/Abstract]) OR blind*[Title/Abstract]) OR allocate*[Title/Abstract]) OR assign*[Title/Abstract]) OR volunteer*[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((Antibioti*) OR anti‐bacterial*) OR antibacterial*) OR Probioti*) OR ofloxacin) OR levofloxacin) OR ciprofloxacin) OR metronidazole) OR azithromycin) OR clarithromycin) OR erythromycin) OR amoxicillin) OR penicillin) OR loracarbef) OR ceph*) OR trimethoprim) OR vancomycin) OR augmentin) OR chemoprophylaxis) OR Quinolone*)) OR "Antibiotic Prophylaxis"[Mesh])) OR antimicrobial*) OR anti‐microbial*)) AND (((((cystoscop*) OR Cystourethroscop*) OR urethrocystoscop*)) OR "Cystoscopy"[Mesh])))

Appendix 3. Embase (Elsevier) search strategy

#1 antibacterial*

#2 antimicrobial*

#3 antibioti*

#4 premedication

#5 probioti*

#6 ofloxacin

#7 levofloxacin

#8 ciprofloxacin

#9 metronidazole

#10 azithromycin

#11 clarithromycin

#12 erythromycin

#13 amoxicillin

#14 penicillin

#15 loracarbef

#16 ceph*

#17 trimethoprim

#18 vancomycin

#19 augmentin

#20 chemoprophylaxis

#21 'antibiotic prophylaxis'/exp

#22 or/1‐21

#23 'cystoscopy'/exp

#24 cystoscop*

#25 cystourethroscop*

#26 urethrocystoscop*

#27 or/23‐26

#28 random*:ab,ti

#29 groups:ab,ti

#30 trial:ab,ti

#31 placebo:ab,ti

#32 controll*:ab,ti

#33 blind*:ab,ti

#34 allocate*:ab,ti

#35 assign*:ab,ti

#36 volunteer*:ab,ti

#37 randomized controlled trial

#38 controlled clinical trial

#39 'controlled clinical trial'/exp

#40 randomized controlled trial

#41 'randomized controlled trial'/exp

#42 or/28‐41

#43 #22 and #27 and #42

Appendix 4. LILACS search strategy

(tw:((tw:(groups OR trial OR placebo OR random* OR assign* OR allocate* OR blind* OR controll* OR volunteer*)))) AND (tw:((tw:( (tw:(Antibioti* or anti‐bacterial* or antibacterial* or Probioti* or ofloxacin or levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin or metronidazole or azithromycin or clarithromycin or erythromycin or amoxicillin or penicillin or loracarbef or ceph* or trimethoprim or vancomycin or augmentin or chemoprophylaxis or Quinolone*)))) AND (tw:(cystoscop* OR Cystourethroscop* OR urethrocystoscop*))))

Appendix 5. CINAHL (EBSCOhost) search strategy

TX ( Antibioti* or anti‐bacterial* or antibacterial* or Probioti* or ofloxacin or levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin or metronidazole or azithromycin or clarithromycin or erythromycin or amoxicillin or penicillin or loracarbef or ceph* or trimethoprim or vancomycin or augmentin or chemoprophylaxis or Quinolone* ) AND TX ( cystoscop* OR Cystourethroscop* OR urethrocystoscop* ) AND AB ( randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR groups OR trial OR placebo OR random* OR assign* OR allocate* OR blind* OR controll* OR volunteer* )

Appendix 6. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

cystoscopy OR cystoscopic OR Cystourethroscopy OR Cystourethroscopic OR urethrocystoscopy OR urethrocystoscopic

Appendix 7. WHO ICTRP search strategy

cystoscop* OR Cystourethroscop* OR urethrocystoscop*

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Systemic urinary tract infection (UTI) | 5 | 504 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.38, 3.32] |

| 2 Symptomatic UTI | 11 | 5441 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.28, 0.86] |

| 2.1 Flexible cystoscope | 3 | 2377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.32, 1.10] |

| 2.2 Rigid cystoscope | 8 | 3064 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.19, 0.91] |

| 3 Minor adverse effects | 4 | 630 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.82 [0.54, 14.80] |

| 4 Localized UTI | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.06, 15.77] |

| 5 Asymptomatic bacteriuria | 10 | 5447 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.30, 0.53] |

| 5.1 Flexible cystoscope | 3 | 2377 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.25, 0.59] |

| 5.2 Rigid cystoscope | 7 | 3070 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.28, 0.61] |

| 6 Bacterial resistance | 2 | 38 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.73 [1.04, 2.87] |

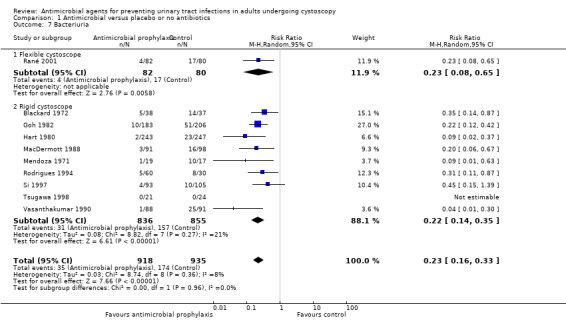

| 7 Bacteriuria | 10 | 1853 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.23 [0.16, 0.33] |

| 7.1 Flexible cystoscope | 1 | 162 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.23 [0.08, 0.65] |

| 7.2 Rigid cystoscope | 9 | 1691 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.22 [0.14, 0.35] |

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antimicrobial versus placebo or no antibiotics, Outcome 7 Bacteriuria.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Asuero 1989.

| Methods |

Study design: prospective randomized control study Study dates: not available Setting: 1 hospital Country: Spain |

|

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: people with negative preoperative urine cultures Exclusion criteria: allergy to penicillins, indwelling catheter, easily bleeding during manipulation Sample size: 46 Age (years): overall median: 65 (51–78) Sex: not available |

|

| Interventions |

Group 1 (n = 23): no antibiotic prophylaxis Group 2 (n = 23): cefuroxime 750 mg intravenously 1 hour preoperatively and 2 more doses administered at 12 and 24 hours after surgery |

|

| Outcomes |

Systemic UTI How measured: not reported Time points measured: not reported Time points reported: not reported Outcomes: no participant had symptoms suggestive of a UTI Asymptomatic bacteriuria How measured: not reported Time points measured: urine cultures performed on 5th day and 1 month postoperatively Time points reported: not reported Outcomes: control group: 16/23 participants had bacteriuria 5 days after cystoscopy, and 2/23 had bacteriuria 1 month after cystoscopy; treatment group: 3/23 had bacteriuria 5 days after cystoscopy, and 5/23 had bacteriuria 1 month after cystoscopy Bacterial resistance How measured: not reported Time points measured: bacteria cultures from urine performed 5 days after cystoscopy Time points reported: not reported Outcomes: control group: 16 participants with positive urine cultures, 9 of them they showed no sensitivity to cefuroxime; treatment group, 3 participants were all resistant |

|

| Funding sources | No information about funding | |

| Declarations of interest | No information about conflict and interest | |

| Notes | In the antibiotic prophylaxis group, all participants with negative blood cultures in the 3rd postoperative day, and 4 participants in the control group had bacteraemia. 3 participants showed an acute epididymitis after cystoscopy, but this study did not report which group they came from. No email address available for contacting the corresponding author for further information. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "We have carried out a prospective study on 46 patients, these 46 patients were randomly divided into two groups." Comment: method for generation of random sequence not given. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: no information regarding the concealment of randomization. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "A first control group of 23 patients who were not administered antibiotic prophylaxis, a second group of 23 patients who were administered 750 mg." Comment: participants in control group were not administered antibiotic prophylaxis, while the treatment group receive intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis. Unlikely that participants and personnel were blinded to intervention. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Subjective outcomes | High risk | Quote: "A first control group of 23 patients who were not administered antibiotic prophylaxis, a second group of 23 patients who were administered 750 mg." Comment: participants were not blinded to their treatment, the risk of detection bias for subjective outcomes, i.e. symptoms suggestive of UTI after cystoscopy was high. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Objective outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "When cultures were positive postoperative urine, the sensitivity of the germ to cefuroxime titrated were tested." Comment: since bacterial resistance was evaluated by urine culture from laboratory, results were objective and probably not influenced by blinding or not. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Systemic UTI | Low risk | Quote: "no participant had symptoms suggestive of a urinary tract infection." Comment: 46/46 participants (23 participants in each arm) included for analysis of this outcome, this risk of bias was low. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Symptomatic UTI | Low risk | Quote: "no participant had symptoms suggestive of urinary tract infection." Comment: 46/46 participants (23 participants in each arm) included for analysis of this outcome, this risk of bias was low. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Serious adverse events | Unclear risk | Comment: outcome not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Minor adverse events | Unclear risk | Comment: outcome not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Localized UTI | Unclear risk | Comment: outcome not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Asymptomatic bacteriuria | Low risk | Quote: "Urine cultures performed the 5th postoperative day were positive in three patients in the prophylaxis group (13%) remain negative in the remaining 20 (87%). By contrast, in the control group, these cultures were positive in 16 (69.6%) and negative in 7 of them (30.4%)." Comment: 46/46 participants (23 participants in each arm) included for analysis of this outcome, this risk of bias was low. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) Bacterial resistance | Low risk | Quote: "Three patients in the prophylaxis, isolated germs were resistant, whereas in the control group of 16 patients with positive urine cultures 9 of them they showed no sensitivity." Comment: all included participants were included for analysis of this outcome. 46/46 participants (23 participants in each arm) included for analysis of this outcome, this risk of bias was low. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: data reported on all outcomes specified in methods section, but there was no access to trial protocol/registration to further assess selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Comment: no other bias detected. |

Blackard 1972.

| Methods |

Study design: parallel‐group, double‐blind randomized trial Study dates: 1 January 1969 to 31 December 1969 Setting: 1 hospital Country: USA |

|

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: no fever or clinical UTI; required no antibacterial agents during the preceding 2 weeks; no retention type urethral catheter; no need for immediate operation; no allergy to sulphonamide Exclusion criteria: not available Sample size: 75 men Age (years): overall median 74 (44–82) Sex: all men |

|

| Interventions |

Group 1 (n = 37): placebo, oral, started 2 days before cystoscopy and maintained 10 days following cystoscopy Group 2 (n = 38): sulphamethoxazole 500 mg + phenazopyridine 100 mg, oral, started 2 days before cystoscopy and maintained 10 days following cystoscopy |

|

| Outcomes |