Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to describe methods used to recruit and retain high-risk, Spanish-speaking adults of Mexican origin in a randomized clinical trial that adapts Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) content into a community-based, culturally tailored intervention.

Methods

Multiple passive and active recruitment strategies were analyzed for effectiveness in reaching the recruitment goal. Of 91 potential participants assessed for eligibility, 58 participated in the study, with 38 in the intervention and 20 in the attention control group. The American Diabetes Association Risk Assessment Questionnaire, body mass index, and casual capillary blood glucose measures were used to determine eligibility.

Results

The recruitment goal of 50 individuals was met. Healthy living diabetes prevention presentations conducted at churches were the most successful recruiting strategy. The retention goal of 20 individuals was met for the intervention group. Weekly reminder calls were made by the promotora to each intervention participant, and homework assignments were successful in facilitating participant engagement.

Conclusions

A community advisory board made significant and crucial contributions to the recruitment strategies and refinement of the intervention. Results support the feasibility of adapting the DPP into a community-based intervention for reaching adults of Mexican origin at high risk for developing diabetes

Latinos have a disproportionate burden of type 2 diabetes, diabetes-related complications, and mortality compared with non-Latino whites.1 In addition, risk factors for developing diabetes are more common in Latinos than in non-Latino whites.2 The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) demonstrated that lifestyle modification that led to a modest weight loss could prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes.3 However, little is known about how to translate these findings into a community-based intervention and, specifically, how to recruit and retain this high-risk and difficult to reach population.4

Although it is challenging to recruit sufficient numbers of participants for research studies in general, it can be especially difficult to recruit Mexican Americans to participate.5 Factors such as language barriers, low levels of health literacy, lack of access to primary care providers, economic constraints, lack of transportation, fear of participating in research, and unacceptability of randomization can all act as barriers to recruitment.4–7 Addressing these barriers while understanding cultural values and beliefs and community cohesion is important to successfully recruit participants into a research study.8

This article describes the experience of successfully recruiting and retaining a sample of high-risk, Spanish-speaking Latinos of Mexican origin into a randomized clinical trial of a community-based diabetes prevention intervention, Estillo deVida Saludable (EVS). The development of a community advisory board and its role in informing the intervention and developing culturally appropriate recruitment strategies are described. The recruitment and retention strategies used, the challenges encountered, and successful solutions to achieve recruitment and retention goals, as well as demographic and clinical characteristics of the recruited sample, are presented.

Methods

EVS was a randomized 2-group, attention control trial to evaluate the feasibility of the EVS intervention by examining barriers and facilitators to recruitment and retention. The intervention adopted the DPP goals of weight loss and increased physical activity and built on the DPP Lifestyle in Balance program of healthy eating and minimum weekly physical activity of 150 minutes. The EVS intervention extended the DPP content to include culturally relevant material and used simple stories told in pictures (fotonovela) and small semistructured group discussions to deliver diabetes prevention information. The attention control group received general information on health promotion and disease prevention. The 5-month intervention consisted of an intensive phase comprised of 8 weekly 2-hour sessions followed by a maintenance phase of 3 monthly 2-hour sessions.

A recruitment goal of 50 Spanish-speaking adults of Mexican descent was set to allow for an attrition rate of 20% and yield a final sample size of 40. Individuals were eligible to participate in the study if they were 25 years of age or older, were self-identified as Mexican American, were overweight (body mass index [BMI] >25 kg/m2), were not pregnant, reported no medical restrictions related to the intervention physical activity or dietary goals (decrease fat intake, walk 150 minutes per week), and had casual (fasting or nonfasting) capillary blood glucose levels between 100 and 199.9,10 Individuals with a casual blood glucose in the diabetes range were referred to their primary care provider or a local clinic. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Arizona and University Physicians Health Systems.

Community Advisory Board and Community Partners

Community advisory boards (CABs) have long been used in community-based research. These boards link the researcher and the community, provide structure to guide the development and conduct of research, and give voice to community concerns and priorities.11 Time and effort are required to develop trusting community partnerships, which are critical considerations for translational research.

The CAB used in this study was incrementally developed over several years and builds on community partners—individuals and organizations—who participated in previous research studies conducted by the principal investigator (PI) with persons of Mexican origin. The original partnership established with a local community health center resulted in collaborative relationships with a promotora (community health worker) and a student worker at the clinic. These individuals served as culture brokers, providing insight and advice on working with members of the Mexican American culture, and introduced the PI to other key members of the community and organizations who became critical to conducting research in the community.12 An outcome of this collaboration was the conduct of 2 small studies that included the promotora and student as grant team members.13,14

Over several years, additional members were added to the CAB. Inclusion criteria for CAB membership included adults with close ties to the Mexican American community who had an interest in and experience with diabetes and were bilingual or English speaking. Ultimately, the CAB consisted of 8 members and included a diabetes educator, staff members from a grandparent support group and a faith-based community center, 2 lay people interested in diabetes prevention, a health care case manager, a promotora, and the PI. The majority of these individuals were of Mexican descent, and they were bilingual in Spanish and English.

During the start-up phase of the EVS study, the CAB assumed an active role in culturally tailoring the intervention. The CAB met monthly to discuss how to culturally tailor the intervention, refine the fotonovela story board and script, and develop recruitment strategies. Because the CAB was relatively small,11 much of the work in refining the study was done as a “committee of the whole,” although subcommittees were used for translation of the fotonovela into Spanish. The original fotonovela, developed in an earlier study, consisted of 5 episodes and told the story of a grandmother with prediabetes and the support she received from her family in making lifestyle changes necessary to lose weight. Two members of the CAB (the promotora and student) played the grandmother and granddaughter in the fotonovela. Based on the results of that previous study, the intensive phase of the intervention was lengthened to 8 weeks. The CAB reviewed the original fotonovela and revised it to consist of 8 episodes needed to be consistent with the 8-week intensive phase of the intervention. The CAB also revised some of the dialogue to be more culturally appropriate and engaging. Two CAB members translated the English script into Spanish and another checked the Spanish version against the English version for conceptual congruency.15

The CAB also reviewed all intervention and recruitment materials for cultural relevance for the target population. Potential data collection instruments were presented by the PI and discussed for cultural appropriateness and respondent burden. Initially, some members of the CAB were hesitant to critique research instruments, often stating, “I don’t know much about research.” However, with coaching, respectful listening, and creation of a safe environment for all to contribute to the discussion, CAB members eventually overcame any hesitation and actively participated in the discussions. Members often asked pertinent questions, such as “Why is there an attention control group? What is the purpose?” These questions provided an opportunity to explore assumptions about how to conduct the study and clarify study design or recruitment issues. Additionally, members identified potential candidates to serve as the promotora and the research assistant for the EVS study. Ultimately, one of these promotora candidates was hired for the study.

In conjunction with CAB members, the PI actively sought and developed partnerships with local community organizations. These included churches, community clinics, health care providers, and neighborhood recreation centers (YMCA and the city parks and recreation centers). Many of these organizations, especially the Catholic churches, were keenly aware of the problem of diabetes in the community and expressed interest in collaborating with the research team. Developing partnerships with churches was relatively easy because the PI and several members of the CAB had strong relationships within the faith-based community, especially with several Catholic churches.

The PI and members of the CAB approached church pastors or community outreach ministers and informed them of the study. Six Catholic churches and 6 Protestant churches were approached to discuss how the churches might participate or partner with the EVS study team. Decision makers at the Catholic churches were very enthusiastic, and 5 decided to participate. Decision makers at the Protestant churches contacted were more hesitant, expressing concern about spending resources on health rather than spiritual issues. Ultimately only 1 Protestant church, which had a very large Spanish-speaking population, agreed to participate in the study and hosted a presentation on healthy living and diabetes prevention.

Recruitment Strategies

A recruitment goal of 48 Spanish-speaking adults of Mexican descent was set to yield a final sample size of 40, allowing for an attrition rate of 20%.16,17 This sample size was adequate to determine the feasibility of community recruiting, assess factors such as recruitment time and effort, and estimate effect size.

Several recruitment strategies were used in this study. First, flyers and announcements in English and Spanish were placed in highly visible areas of participating community health clinics. These flyers were also placed in a variety of locations, such as senior centers, community centers, and local groceries, located in an area of the city with a high density of Mexican American residents. Additionally, these flyers were used at community health fairs and other community events to inform community members about the study.

Next, university communication channels, such as e-mail listserves, were used to disseminate information about the study to faculty and staff. The flyers and the university announcements contained a phone number for a dedicated voice mail where potential participants could leave their contact information. The university marketing office also sent public service announcements about the study to local media outlets.

The PI met with providers at collaborating community clinics to inform them about the study and request their help in referring potential participants to the study. Providers were given a brief overview of the study and the inclusion criteria to facilitate identification of potential participants. Providers were requested to give prospective participants a recruitment flyer and obtain permission to provide the PI with their contact information if they were interested in receiving more information about the study. If the participant agreed to be contacted, the provider supplied the research team with the name and contact information of the potential participant.

A recruitment strategy suggested by the Catholic church partners was to develop a presentation on healthy living and diabetes prevention. The research team and the CAB developed the 30-minute presentation that addressed diabetes risk factors and how to minimize these by eating healthfully and increasing activity. The churches provided a meeting space, announced the event in church bulletins, and provided audiovisual equipment. The presentation was delivered by bilingual research staff members at all 6 partnering churches. At the end of each presentation, the research staff informed attendees about the diabetes prevention study and instructed those who wished to learn more about the study to talk with the research staff. These events were held after Spanish-language church services were conducted in both English and Spanish, and refreshments were served.

The research team participated in several community health fairs and provided healthy living exhibits and recruiting materials at other community events, including a large multicultural festival, YMCA worksite wellness events, and a diabetes information fair. All of these partnerships were crucial to disseminating information about the study and thereby aiding in recruitment.

Screening Process, Enrollment, and Randomization

The majority of screening and baseline assessment was done after the healthy living and diabetes prevention presentations were held at the churches. All interested participants were asked to complete the 7-item American Diabetes Association (ADA) risk assessment questionnaire, and those with a score of 10 or greater were considered at risk for developing diabetes.18 These risk factors include overweight or obesity, ethnicity, family history of diabetes, and low level of physical activity.9,10 All individuals who completed the questionnaire were counseled by the PI about their risk status. All individuals interested in participating who were 25 years of age or older, were self-identified as of Mexican origin, were fluent in Spanish, had a ADA risk assessment score of 10 or greater, and had no exclusion criteria (pregnancy, history of diabetes or taking diabetes medication) were eligible to proceed to consenting and baseline data collection.

Interested individuals were taken to a private area in the church community room, where they gave consent and then had baseline data (BMI and casual capillary glucose) collected. Eligible individuals needed a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or more and a casual blood glucose between 100 and 199 mg/dL. Those who heard about the study through study marketing efforts and called the study telephone were screened by research staff for eligibility over the phone. An appointment for consenting and data collection was scheduled at a mutually convenient time at either one of the study’s faith-based sites or at the research office.

Retention Methods

The promotora, a member of the research staff, made weekly reminder phone calls to participants. The promotora provided participants with her cell phone number and encouraged them to call with questions or concerns. To facilitate participant engagement and retention, the promotora gave weekly homework assignments that emphasized content discussed during that session such as identifying a social cue that triggered overeating, walking 5 minutes longer each week, or trying a new stress management activity.

Results

Screening and Recruitment Results

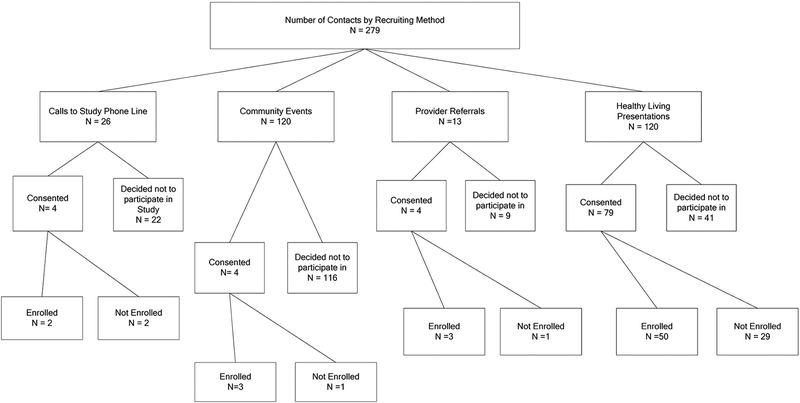

The number of individuals contacted and the number consented for each strategy were tracked. The research team members spoke to a total of 279 individuals through the various recruitment strategies (Figure 1). The majority of contacts came from the research team’s participation in community events (n = 120) and the healthy living/diabetes prevention presentations at the churches (n = 120). The other 39 contacts were through calls to the study phone line (n = 26) and provider referrals (n = 13). However, the best strategy was the healthy living/diabetes prevention presentations: 79 individuals viewing these presentations agreed to participate in the study and were consented.

Figure 1.

Recruiting methods.

There were 26 telephone calls to the study telephone line that were made after the caller saw the university listserve or a public service announcement. Four of these individuals chose to participate in the study and were consented. For those who chose not to participate, the most common reasons were that the person had diabetes or the time or place was inconvenient.

Members of the research team attended 5 community events and provided information about the study to approximately 120 individual attendees. These events included a multicultural festival, a diabetes awareness health fair, worksite wellness health fairs, and an open house for parents at a middle school. Most individuals expressed curiosity about the study and took flyers for friends or other family members, but only 4 chose to participate and were consented.

Health care providers referred 13 referrals potential participants. Research staff were able to contact 9 by telephone, and 4 of these chose to participate and were consented. Five individuals were not interested in participating due to the time commitments.

A total of 120 individuals attended the 6 presentations on healthy living and diabetes prevention conducted at churches. Seventy-nine of these individuals were consented, and 50 individuals (8.3 per event) met all eligibility criteria and were enrolled. Another 12 individuals were referred by friends who had seen information about the study or were participants, and 8 were enrolled in the study.

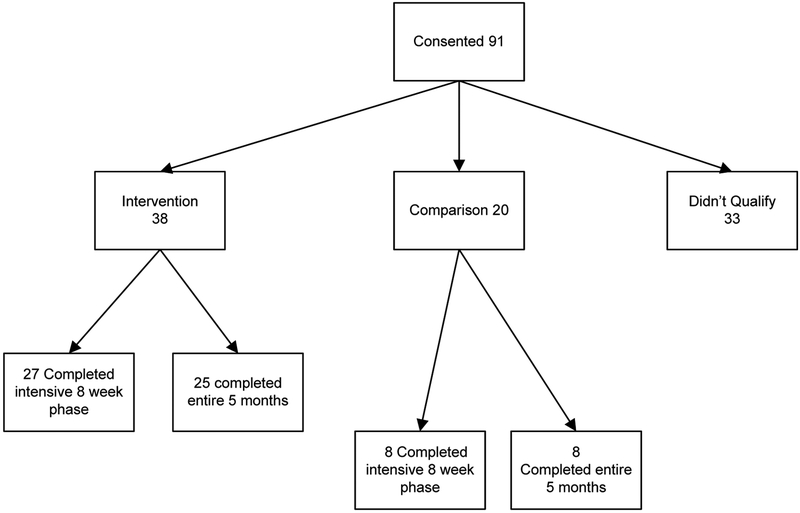

In total, 91 individuals were consented, but 33 were not enrolled as they did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 2). The majority of those not enrolled (n = 29) had casual capillary blood glucose levels below 100 mg/dL, and 1 person had a level indicating undiagnosed diabetes. Two individuals decided not to participate after being consented, and another was taking metformin. Subsequently 58 individuals were enrolled in the study: 38 individuals in the intervention condition and 20 in the control.

Figure 2.

Number of participants consented, group allocation, and completion.

The effort involved in recruiting was important to estimate for this feasibility study. Time spent in recruiting activities, including telephone calls, was tracked. The majority of recruitment effort (200 hours) was spent in arranging and conducting presentations on healthy living and diabetes prevention. Another 150 hours was spent in recruiting efforts at community events. Responding to telephone inquiries and contacting provider referrals accounted for approximately 15 hours. Recruitment efforts for the study totaled 365 hours, or 4 hours per participant consented. The estimated total number of recruiting contacts (telephone and individual) was 279, slightly less than 5 contacts per person enrolled in the study.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the sample. The majority of participants were female (77.6%), middle-aged (mean 50.9 years), and married (60.3%) and reported incomes of $20,000 per year or less (56.9%). The mean number of years of education was 11; the mean ADA risk assessment score was 13.97 and ranged from 10 (minimum eligibility score) to 24. All participants were overweight or obese with a mean BMI of 34.32, mean weight of 198.24 pounds, and a mean waist circumference of 43.17 inches. Mean casual blood glucose was 123.47 and ranged from the minimum enrollment criterion of 100 to a maximum of 183 mg/dL.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Risk Factors for Intervention and Control Participants

| Characteristic | Total | Intervention | Control | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 50.93 (12.049) | 49.97 (12.080) | 52.75 (12.087) | t56 = 0.832, P = .409 |

| Range | 29–84 | 29–84 | 31–76 | |

| n | 58 | 38 | 20 | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 13 (22.4) | 9 (23.7) | 4 (20.0) | χ21 = 0.102, P = .749 |

| Female | 45 (77.6) | 29 (76.3) | 16 (80.0) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Single | 7 (12.1) | 5 (13.2) | 2 (10.0) | χ23 = 1.888, P = .596 |

| Married | 35 (60.3) | 22 (57.9) | 13 (65.0) | |

| Separated/divorced | 13 (22.4) | 8 (21.1) | 5 (25.0) | |

| Widowed | 3 (5.2) | 3 (7.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Years of education | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 11 (4.527) | 10.37 (4.647) | 12.20 (4.137) | t56 = 1.480, P = .145 |

| Range | 1–19 | 1–19 | 4–17 | |

| n | 58 | 38 | 20 | |

| Income, n (%) | ||||

| $20,000 | 33 (56.9) | 22 (59.5) | 11 (55.0) | χ24 = 4.704, P = .319 |

| $20,001–30,000 | 9 (15.5) | 7 (18.9) | 2 (10.0) | |

| $30,001–40,000 | 9 (15.5) | 4 (10.8) | 5 (25.0) | |

| $40,001–50,000 | 5 (8.6) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (5.0) | |

| <$50,000 | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.0) | |

| ADA risk score | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 13.97 (2.877) | 13.37 (3.079) | 15.10 (2.075) | t52.41 = 2.54 P = .014 |

| Range | 10–24 | 10–24 | 10–20 | |

| n | 58 | 38 | 20 | |

| BMI | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 34.320 (6.238) | 34.599 (5.784) | 33.789 (7.151) | t56 = 0.466, P = .643 |

| Range | 25.8–51.0 | 25.8–46.7 | 26.5–51.0 | |

| n | 58 | 38 | 20 | |

| Weight, pounds | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 198.24 (40.583) | 200.11 (41.658) | 194.70 (39.258) | t56 = 0.479, P = .634 |

| Range | 132.8–321.2 | 140.6–321.2 | 132.8–280.2 | |

| n | 58 | 38 | 20 | |

| Waist circumference, inches | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.174 (6.222) | 43.355 (5.108) | 42.811 (8.161) | t55 = 0.309, P = .758 |

| Range | 29.6–63.8 | 35.5–56.0 | 29.6–63.8 | |

| n | 57 | 38 | 19 | |

| Casual blood glucose, mg/dL | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 123.47 (18.720) | 124.39 (21.731) | 121.70 (11.254) | t55.99 = 0.622, P = .536 |

| Range | 100–183 | 100–183 | 104–140 | |

| n | 58 | 38 | 20 |

Abbreviations: ADA, American Diabetes Association; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Of the 38 participants enrolled in the intervention group, 30 (79%) attended at least 1 of the 8 intensive phase sessions, whereas 8 (21%) never attended a single session. Of those participants who attended the first intervention session, 92.6% completed the entire 5-month intervention. Retention rates for the control group were somewhat lower. Of the 20 individuals enrolled in the control group, 15 (75%) attended at least 1 session but only 8 participants (40%) completed the entire 5-month program.

Discussion

We have reported the recruitment and retention strategies, baseline characteristics of the participants, and outcomes of this randomized 2-group trial to evaluate the feasibility of translating the DPP into a community-based intervention with Mexican American adults. Through an inclusive process, active engagement, and coaching, all members of the CAB learned about the research process and made significant and crucial contributions to the recruitment strategies and refinement of the intervention. The study recruitment goal of 48 adults was achieved. The research team spoke to 279 individuals and enrolled 58, or approximately 1 enrollee for every 5 contacts. This is a somewhat lower ratio than the 1 enrollee per every 7 to 9 contacts reported in other studies.19,20

The most effective of the multiple recruitment methods used in the EVS (Figure 2) was the healthy living and diabetes prevention presentations conducted at churches. Fifty of the 58 (86%) participants were recruited this way. The effectiveness of using churches for community outreach recruiting is supported by several studies.21–23 Recruitment was facilitated at these presentations by conducting them in familiar locations (church halls) at convenient times, such as after a Spanish-language Mass, and each presentation was conducted by bilingual research team members of Mexican descent. These strategies helped to minimize cultural and contextual barriers to recruitment and have been widely used in other studies.4,13,22,24–28 Relationships, communication, trust, and respect are important in working with any population but particularly important when working with Mexican Americans4,21,27 and when conducting an intervention trial.28

Recruitment flyers alone were completely ineffective but when included as part of a mass e-mail to university members resulted in 4 participants (7%). The ineffectiveness of flyers as a recruitment strategy is supported by other studies.13,22 Although research team members spoke to a significant number of potential participants at community events, the yield was low, with only 3 participants recruited this way (5%). Provider referrals were also a disappointing strategy for recruitment. Providers referred only 13 potential participants out of the 279 individuals contacted. Of these 13 referrals, only 3 participants (5.2%) enrolled in the study. Providers are busy and may not think about referring a potential participant during a patient visit as their attention is likely to be focused on patient care. The relatively high refusal rate of 9 of the 13 (69%) referrals may reflect the importance of personal relationships in the Mexican culture.4,21,27 These potential participants received a telephone call from study personnel but had no personal relationship with the caller. Face-to-face contact, personal relationships, and grant staff from the target community are important recruitment strategies in the Mexican American population.4,13,21,25,27

The retention goal of 40 individuals completing the 5-month program was not met. Only 33 of the 58 enrolled individuals completed the study, for a retention rate of 57%. However, the attrition rate for the control group was substantially higher than for the intervention group, with only 40% of control participants completing the entire 5-month program. Many control participants complained about being in the control condition despite saying that they understood about the randomization process. Participant resistance to being in a control group and subsequent attrition have been reported by other studies.25 This raises questions about the consenting process and the need to explore additional approaches to ensure that potential participants understand what is being asked of them as a participant in the study. Members of the first cohort of control participants lobbied the PI to have access to diabetes prevention content. To accommodate this strong preference and maintain the integrity of the control condition, the study design was revised to provide an opportunity for control participants to cross over to an abbreviated intervention once the 5-month control program was completed. This strategy was successful, and most participants expressed that they came to value what they learned in the control and appreciated having an opportunity to also learn diabetes prevention content.

One major unanticipated barrier to recruitment emerged during the study and adversely affected recruitment. Passage of a strict anti–illegal immigration law occurred as the EVS study was beginning. This created an atmosphere of fear and anxiety in the Mexican American community, and many potential participants stated they were afraid to participate in groups. Having CAB members and study personnel who were of Mexican American descent and familiar with the community and using churches as study sites helped to limit the detrimental effect of this legislation.

This study has several limitations, including the relatively small sample size and the low participation rate of men. Although the study included an attention control group, most control participants wanted diabetes prevention information and this desire affected the control group retention rate. Although the study was designed to focus on Spanish-speaking adults of Mexican origin, this limits generalizability. Further research is needed to examine recruitment and retention strategies for bilingual or English-speaking adults of Mexican origin.

Advancing the science for decreasing diabetes health disparities among Mexican Americans requires their participation in community-based intervention research studies. The findings from the EVS study further support the use of active and culturally congruent recruitment and retention strategies to facilitate translation of the DPP with this minority population.

Acknowledgments:

This study was funded by the National Institute of Health, NIDDK, 1R34DK085195–01. Special thanks are given to Leticia Martinez, Susana Alfaro, Alva Espiriti, Maria Figueroa, and Yolanda Garcia for their contributions in recruiting study participants.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: National Estimates and General Information on Diabetes and Prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers of Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Alliance for Hispanic Health. The State of Diabetes. Washington, DC: National Alliance for Hispanic Health Publications; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or Metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosal M, White MJ, Borg A, et al. Translational research at community health centers: challenges and successes in recruiting and retaining low-income Latino patients with type 2 diabetes into a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(5):733–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald A, Treweek S, Shakur H, et al. Using a business model approach and marketing techniques for recruitment to clinical trials. Trials. 2011;12:74 http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/12/1/74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ejiogu N, Norbeck J, Mason M, Cromwell B, Zonderman A, Evans M. Recruitment and retention strategies for minority poor clinical research participants: lessons from the Healthy Aging in neighborhoods of diversity across the lifespan. Gerontologist. 2011;51(suppl):S33–S45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Free C, Hoile E, Robertson S, Knight R. Three controlled trials of interventions to increase recruitment to a randomized controlled trial of mobile phone based smoking cessation support. Clin Trials. 2010;7:265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dilworth-Anderson P Introduction to the science of recruitment and retention among ethnically diverse populations. Gerontologist. 2011;51(suppl 1):S1–S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(suppl 1):S11–S61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruggiero L, Oros S, Choi YC. Community-based translation of the diabetes prevention program’s lifestyle intervention in an under-served Latino population. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(4):564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman S, Andrews J, Magwood G, Jenkins C, Cox M, Williamson D. Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: a synthesis of best processes. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(3):A70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crist J, Escandon-Dominguez S. Identifying and recruiting Mexican American partners and sustaining community partnerships. J Transcult Nurs. 2003;14(3):266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vincent D, Pasvogel A, Barrera A. A feasibility study of a culturally tailored diabetes intervention for Mexican-Americans. Biol Res Nurs. 2007;9(2):130–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent D, McEwen M, Pasvogel A. The validity and reliability of a Spanish version of the summary of diabetes self-care activities questionnaire. Nurs Res. 2008;57(2):101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones E, Mallinson R, Phillips L, Kang Y. Challenges in language, culture, and modality. Nurs Res. 2006;55(2):75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ackermann RT, Finch E, Brizendine E, Zhou H, Marrero DG. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into the community: the DEPLOY study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(4):357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittemore R, Melkus G, Wagner J, Dziura J, Northrup V, Grey M. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program to primary care.Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):2–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diabetes Risk Test. American Diabetes Association Web site. http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/prevention/risk-factors/. Accessed May 5, 2012.

- 19.Seidel M, Powell R, Zgibor J, Siminerio L, Piatt G. Translating the diabetes prevention program into an urban medically under-served community. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):684–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincent D Culturally tailored education to promote lifestyle change in Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21(9):520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crist J, Parson M, Warner-Robbins C, Mullins MV. Pragmatic action research with 2 vulnerable populations. Fam Community Health. 2009;32(4):320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez MD, Rodriguez J, Davis M. Recruitment of first-generation Latinos in a rural community: the essential nature of personal contact. Fam Process. 2006;45(1):87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.UyBico S, Pavel S, Gross C. Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: a systematic review of recruitment interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;22:852–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crist J, Woo SH, Choi M. A comparison of the use of home care services by Anglo-American and Mexican American elders. J Transcult Nurs. 2007;18(4):339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gul R, Parveen A. Clinical trials: the challenge of recruitment and retention of participants. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kluding P, Singh R, Goetz J, Rucker J, Barcciano S, Curry N. Feasibility and effectiveness of a pilot health promotion program for adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(4):595–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McEwen MM, Pasvogel A, Gallegos G, Barrera L. Diabetes self-management social support intervention in the U.S.-Mexico border. Public Health Nurs. 2010;27(4):310–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yancey A, Ortega A, Kumanyika S. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Ann Rev Public Health. 2006;27:1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]