Abstract

Laypersons and experts believe that wisdom is cultivated through a diverse range of positive and negative life experiences. Yet, not all individuals with life experience are wise. We propose that one possible determinant of growth in wisdom from life experience is self-reflection. In a lifespan sample of adults (N = 94) ranging from 26 to 92 years of age, we examined wisdom’s relationship to self-reflection by investigating ‘why’ people report reflecting on the past (i.e., reminiscence functions) and ‘how’ they reflect within autobiographical memories of difficult life events (i.e., autobiographical reasoning). We assessed wisdom using self-report, performance, and nomination approaches. Wisdom was unrelated to the frequency of self-reflection; however, wiser people differed from others in their (1) reasons for reminiscence and (2) mode of autobiographical reasoning. Across three methods for assessing wisdom, wisdom was positively associated with exploratory processing of difficult life experience (meaning-making, personal growth), whereas redemptive processing (positive reframing, event resolution) was associated with well-being. This study suggests that developmental pathways in the wake of adversity may be partially determined by how individuals self-reflectively process significant life experiences.

Keywords: wisdom, well-being, self-reflection, autobiographical reasoning, reminiscence functions, difficult life events

Wisdom is a hallmark of optimal human development—a rare personal resource that benefits both society in a broad sense and the individual who wields it. Despite its importance, the scientific study of wisdom is relatively young, with most of the work in the last 30 years dedicated to issues of definition and measurement, rather than understanding its development (see Ferrari & Weststrate, 2013; Staudinger & Glück, 2011). In the Western philosophical literature, wisdom has long been defined as the experience, knowledge, and judgment required for living ‘the good life’ (e.g., Aristotle, trans. 2002). In contemporary psychology, definitions of wisdom have ranged from a constellation of mature personality attributes (e.g., Ardelt, 2003; Webster, 2003, 2007) to expertise in fundamental life matters (e.g., Baltes & Smith, 1990; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000).

We define wisdom as a body of experience-based knowledge about the fundamental issues of human life that is both broad and deep, and implicit and explicit. Wisdom manifests outwardly in the form of exceptional advice-giving, decision-making, and problem-solving capacities. Wisdom is not exclusively cognitive—sufficient levels of certain non-cognitive resources (e.g., openness to experience, reflectivity, emotion regulation) are needed to confront the complexities of life experiences in ways that foster the development of wisdom (Glück & Bluck, 2013; see next section). Thus, wisdom is, and results from, the dynamic interaction of cognitive and non-cognitive resources. In order to assess these unique components of wisdom, in the current study we use multiple assessment methods. Consistent with the range of definitions available, approaches to the measurement of wisdom vary from self-report scales (e.g., Ardelt, 2003; Webster, 2003, 2007) to open-ended performance tasks (e.g., Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Mickler & Staudinger, 2008). Performance measures are particularly well suited for capturing the cognitive aspects of wisdom, whereas self-report scales more effectively assess the non-cognitive components. The use of multiple assessment techniques has the further advantage of eliminating method variance.

Becoming Wiser

When laypersons and experts are asked to comment on how individuals become wise, the resounding answer is ‘life experience’ (Glück & Bluck, 2011; Jeste et al., 2010). Dominant theoretical models propose (or assume) that wisdom is fundamentally based on life experience, rather than explicit training or instruction (e.g., Ardelt, 2005; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Glück & Bluck, 2013; Sternberg, 1998; Webster, 2003; Yang, 2013). Although appealing in its simplicity, Staudinger (1989, 2001) made the important distinction between experiencing a life event and gaining insight from it. Certainly, not all people with life experience are wise, which begs the question: What are the situational and personal resources or processes that nudge some people along the path to wisdom in the wake of life experience, rather than to some other outcome, such as happiness, sadness, or embitterment, to some combination of these, or to no change at all? The extant literature has largely failed to test possible psychological processes that might bolster the active construction of wisdom from life experience (for an exception see Staudinger, 2001), which is a gap that we address in the current study. A burgeoning literature points to a particular subset of characteristics that may be important to the development of wisdom, which we describe next.

The MORE Life Experience Model

Drawing on theory and research from the fields of wisdom, lifespan developmental psychology, and growth through adversity, Glück and Bluck (2013) proposed a theory of wisdom development named the MORE Life Experience Model. According to this framework, five personal resources dynamically interact with life experience to promote wisdom: Mastery, Openness, Reflectivity, Emotion regulation, and Empathy. Individuals who possess higher levels of these particular resources are more likely to (a) encounter wisdom-fostering experiences across their life course, (b) deal with life challenges in a wisdom-promoting manner, and (c) integrate life events into their evolving life story, including lessons and insights gained from those experiences. In the current study, we focus specifically on the reflectivity dimension of the MORE Life Experience Model, arguing that reflection, for now somewhat broadly defined, is especially relevant to how life events are cognitively and emotionally processed and integrated into the life story in wisdom-promoting ways.

Locating reflection in lay and expert theories of wisdom

Alongside life experience, reflection has featured prominently in lay (or implicit) theories and psychological models of wisdom and wisdom development. In the realm of implicit theories, Clayton and Birren (1980), pioneers in wisdom research, were the first to classify reflection as a core component of wisdom, based on a structural analysis of wisdom descriptors (e.g., introspective, intuitive) rated by everyday people. A review of the implicit theory research conducted since Clayton and Birren’s initial investigation found that reflectivity was among the top five defining characteristics of wisdom in the minds of laypeople (Bluck & Glück, 2005). Applying the implicit theory approach to a panel of wisdom researchers, Jeste et al. (2010) found that ‘self-reflection’ and ‘self-insight’ were among the descriptors most strongly associated with wisdom.

Consistent with this, reflection is central to Ardelt (2003) and Webster’s (2003, 2007) models of wisdom (see also Baltes & Staudinger, 2000; Brown & Greene, 2006; Greene & Brown, 2009), although the exact meaning of reflection differs significantly across these models. For example, Ardelt (2003) defines reflection as the ability and willingness to view “phenomena and events from many different perspectives” (p. 278) and the transcendence of one’s self-centeredness, subjectivity, projections, and distortions. This particular treatment of reflection is perhaps more accurately described as ‘reflective thinking’—a style of information processing or level of cognitive maturity that parallels the Neo-Piagetian notion of postformal operations, which has been associated with wisdom in other literature (e.g., Kitchener & Brenner, 1990; Kramer, 1990, 2000; Pascual-Leone, 1990).

Webster (2003, 2007), on the other hand, defines reflection as the tendency to look back on one’s personal past in order to gain insight from it, which can then be applied to future situations. For Webster, reflection is a mechanism or process through which wisdom is extracted from life experiences. Similarly, researchers from the Berlin Wisdom Paradigm proposed an ontogenetic model of wisdom that identified ‘life review’ as one of three central mediating mechanisms through which life experiences are transformed into wisdom (Baltes & Smith, 2008; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000). Consistent with the latter two viewpoints, in the current study, we define reflection as the process of looking back on one’s own life experiences, and the experiences of others, in particular ways and for particular reasons, not all of which are expected to be wisdom-promoting—an idea that we will develop further in the next section.

While few would doubt that reflection is a key node in wisdom’s nomological network, it is still somewhat unclear whether reflection is an antecedent, defining aspect, correlate, or outcome of wisdom. We consider reflection to be both a developmental precursor and component of wisdom. Initially, reflection is a mechanism or process that supports individuals on their developmental trajectory toward wisdom even before wisdom begins to emerge. After supporting the initial development of wisdom, deep and analytical modes of reflection remain a key behavior of the wise person. This viewpoint is generally consistent with psychological wisdom models. Ardelt (2003) and Webster (2003, 2007) both consider reflection to be a component of wisdom, and both models, with varying levels of explicitness, also acknowledge that reflection is necessary for the cultivation of wisdom. Webster (2003), for instance, proposes that reflection and wisdom are “mutually interdependent and develop in a dynamic, reciprocal fashion.” (p. 14). Similarly, Ardelt (2003) claims that the reflective component of wisdom is a “prerequisite” (p. 278) for the cognitive and affective dimensions, which round out her three-dimensional wisdom model. Finally, the Berlin paradigm’s ontogenetic model overtly considers life review to be a developmental precursor to wisdom and also a process in which wise people readily engage. For now, the precise association between reflection and wisdom remains somewhat speculative until longitudinal data are collected that will tease apart developmental sequencing. We maintain, however, that reflection is both developmentally important to wisdom and also a typical behavior of the wise person. In the current study, we test aspects of this theory by investigating how certain types or kinds of reflection are related to wisdom.

To a large extent, we have been discussing reflection in fairly simplistic terms; however, reflection is a complex construct that has been studied from dispositional (e.g., Trapnell & Campbell, 1999), functional (e.g., Bluck, Alea, Habermas, & Rubin, 2005), cognitive (e.g., King & Kitchener, 2004), and narrative (e.g., McAdams, 2001; McAdams & McLean, 2013) perspectives. In the current study we are particularly interested in the (1) self-reported functional uses of reflection (i.e., ‘why’ a person reflects), and (2) behavioral tendencies in narrative processing (i.e., ‘how’ a person reflects). From this point onward, we use the term self-reflection to refer to both functional and behavioral aspects of reflection. We add the prefix self to convey our assumption that reflection directed at making sense of personal experiences, and one’s own role in them, is more conducive to wisdom development than reflection on events unrelated to one’s own life.

In summary, we argue that a key determinant of growth in wisdom from life experience is self-reflection. In the sections that follow, we further specify the relationship between self-reflection and wisdom by arguing that growth in wisdom depends on (a) the person’s underlying motivations for engaging in self-reflection and (b) how they approach self-reflection from a narrative or behavioral standpoint.

Reflecting on Self-Reflection: Why Looking Back (Sometimes) Means Moving Forward

We have argued that self-reflection is a significant source of wisdom when it is directed at making sense of momentous life experiences (Ferrari, Weststrate, & Petro, 2013; Glück & Bluck, 2013; Staudinger, 2001). Through self-reflection, individuals reconstruct, analyze, and interpret real-life sequences of thought, emotion, and action for meaning. The life lessons and insights arrived at through self-reflection lead to an ever-deepening and more complex appreciation of life, which we might call wisdom (Bluck & Glück, 2004).

‘Why’ people reflect on the personal past: Individual differences in reasons for reminiscence

An emergent focus in the field of autobiographical memory has been on the functions or reasons for remembering the personal past, also called ‘reminiscence functions.’ Bluck and her colleagues (Bluck & Alea, 2002, 2011; Bluck, Alea, Habermas, & Rubin, 2005) have proposed three functions of autobiographical remembering: self, directive, and social functions. The self-function involves reflecting on the past for the purpose of maintaining a coherent sense of self over time, despite situational and personal fluctuations across the lifespan (Bluck & Liao, 2013). The directive function involves reminiscing on past experience in order to guide present and future behavior, such as learning how to solve a problem. Finally, the social function involves sharing personal memories to create, maintain, or enhance social relationships (Alea & Bluck, 2003).

Reminiscence functions reflect distinct motivational concerns and functional uses of reflection. Studies have examined determinants of reminiscence functions (i.e., who reflects on the past for what reasons) across characteristics such as personality, age, and gender (Bluck & Alea, 2009, 2011). Research examining the psychological outcomes associated with each reminiscence function is less abundant (cf. Alea & Bluck, 2013; McLean & Lilgendahl, 2008). Since each function represents a distinct use of reflection that varies across individuals, exploring the consequences of reminiscing for various functions is an important direction for research.

In the current study, we examine relations among reminiscence functions and wisdom. Specifically, we focus on two reminiscence functions that are expected to be particularly relevant to gaining wisdom from difficult life experience—the self and directive functions. The social function may be related to wisdom to the extent that individuals sometimes share personal memories in order to teach or inform an advice-seeking person (Alea & Bluck, 2003). In this study, however, we are interested in reminiscence functions that concern private examination of one’s own life experience, rather than the social transmission of wisdom through autobiographical storytelling, although this is a promising direction for future research.

The directive function concerns wisdom to the extent that practically wise people are skilled at solving difficult life problems. As such, wise people are likely to report reflecting on past experiences for the purpose of learning behavioral lessons that can be applied to future situations. Therefore, we would expect the directive function to be positively related to wisdom. Individuals motivated by the self-function explore the meaning of their past experiences for the purpose of affirming an ongoing sense of self or explaining how an event may have led to self-change. The search for deeper self-understanding is likely to foster wisdom, and as a result, we expect the self-function and wisdom to be positively associated. In addition to the reasons that individuals report for engaging in self-reflection, a second objective of this study is to identify forms of narrative processing that are associated with wisdom.

‘How’ people reflect on the personal past: Individual differences in autobiographical reasoning

“The progressive momentum is from storymaking to meaning making to wisdom accumulation that provides individuals with surer and more graceful footing on life’s path.” (Singer, 2004, p. 446). While there are many ways to operationalize self-reflection, in Singer’s quote above, he refers to “storymaking” as the first step in a self-reflective process that ultimately leads to wisdom. A growing body of work has explored the importance of storymaking and storytelling processes in self-development (see McAdams, 2001; McAdams & McLean, 2013; McLean, Pasupathi, & Pals, 2007). To life story researchers, individuals retrospectively make sense of their life experiences by constructing coherent and meaningful autobiographical narratives—a process called autobiographical reasoning (Habermas & Bluck, 2000). By scoring autobiographical memories for individual differences in narrative content, structure, and reasoning process, life story researchers have found that some styles of personal narration are more adaptive and growth-promoting than others (Greenhoot & McLean, 2013; King, 2001; McLean & Mansfield, 2010). Based on this research, we expected that some types of autobiographical reasoning, but not others, would be associated with wisdom.

Varieties of autobiographical reasoning and their associated outcomes

There is burgeoning consensus across studies using factor-analytic techniques that two meta-processes organize lower-level autobiographical reasoning tendencies (King, Scollon, Ramsay, & Williams, 2000; Lodi-Smith, Geise, Roberts, & Robins, 2009; Pals, 2006b). Three studies each factor analyzed multiple narrative indictors of autobiographical reasoning and found two comparable factors. The first factor represents an exploratory, investigative, analytical, and interpretive approach to self-reflection on life events, which emphasizes meaning-making (i.e., extracting lessons and insights), complexity, and growth from the past. In the current study, we refer to this form of autobiographical reasoning as exploratory processing, which is a term used by Lodi-Smith et al. (2009; see also Pals, 2006b). The second factor concerns the tendency to redeem life experiences by transforming an initially negative event into an emotionally positive one, which in turn provides the narrator with a sense of emotional closure and event resolution. We refer to this form of autobiographical reasoning as redemptive processing, based on the work of McAdams, Reynolds, Lewis, Patten, and Bowman (2001). These processing modes differ in the degree to which they emphasize cognitive and affective facets of self-reflection: Exploratory processing involves going deeper into the meaning of the event, whereas redemptive processing concerns positively reframing and moving on from the event emotionally. We expected to replicate these two factors in our study, and test the extent to which they independently and interactively predict wisdom.

Importantly, different styles of autobiographical reasoning predict unique psychological outcomes. Exploratory forms of processing tend to predict psychological maturity, such as ego development and stress-related growth, whereas redemptive processes tend to predict happiness and emotional well-being (e.g., King et al., 2000; Lilgendahl & McAdams, 2011; Pals, 2006b). These differences reflect Staudinger and Kunzmann’s (2005) distinction between growth and adjustment pathways in adult personality development, suggesting that one pathway determinant is the type of autobiographical reasoning that one engages in (see also King, 2001; King & Hicks, 2006; Pals, 2006a). Based on this research, we hypothesized that exploratory processing would be positively correlated with both wisdom and a growth-related measure of well-being, whereas redemptive processing would be positively associated with an adjustment measure of well-being.

With this said, the idea that highly transformative stories combine cognitive and affective modes of processing is consistent with Labouvie-Vief’s (2009) dynamic integration theory, and further suggests that some individuals may coordinate both growth and adjustment responses to life events, in order to produce optimal developmental outcomes. To assess this possibility, in addition to examining the direct relationships between narrative processing mode and growth- and adjustment-related outcomes, we also tested potential interactive effects.

Wisdom and autobiographical reasoning

To date, few wisdom researchers have examined autobiographical reasoning. An early exception was Staudinger (1989, 2001), who proposed a model of ‘life reflection’ that was expected to facilitate the development of wisdom. According to Staudinger, there are two fundamental processes that comprise life reflection: remembering and further analysis. She further decomposed the analytical component of reflection into explanation and evaluation, suggesting that when reflecting on life, wise people examine how an event came to be, how the event relates to current life goals, how similar events can be avoided or sought out in the future, and so on. In a study of life reflection, Staudinger (2001) found that a sample of wisdom nominees and two comparison groups of young and old adults reported the same frequency of reflection on life events, but that wisdom nominees more often used reflection as an evaluative process, rather than simple reminiscence. The analytical stance that wisdom nominees took to self-reflection is akin to exploratory processing.

Bluck and Glück (2004) collected autobiographical memories of times when individuals saw themselves as being wise in thought or action (see also Glück, Bluck, Baron, & McAdams, 2005). They investigated how fully the wisdom-related event was integrated into the participants’ life stories, and found that most participants (60%) illustrated ‘causal coherence’ in their wisdom-related memories—that is, they made explanatory connections between the wisdom-related event and later life events or to the self in general (see Habermas & Bluck, 2000). They further found that most participants reported learning a lesson from the wisdom-related event—a lesson that was generalized to other events or aspects of the self by 80% of the sample. Also collecting autobiographical memories, Mansfield, McLean, and Lilgendahl (2010) examined the link between wisdom and autobiographical reasoning within the context of trauma and transgression memories, using Ardelt’s (2003) Three-Dimensional Wisdom Scale to measure wisdom. The authors found that an exploratory process called ‘personal growth’ in transgression memories predicted higher levels of wisdom. Of the studies available, this was the only study to measure wisdom and autobiographical reasoning quantitatively (see also Ardelt 2005, 2010 for related qualitative analyses).

Taken together, the available research strongly suggests a link between exploratory processing and wisdom. The current study aims to replicate and extend this literature by comprehensively assessing wisdom using three methods and scoring a diverse set of autobiographical reasoning processes in difficult-event memories.

Integrating Functional and Behavioral Perspectives on Self-Reflection

As was outlined earlier, reminiscence functions represent underlying motivations for engagement in self-reflection. Little research has examined the extent to which reminiscence functions are related to autobiographical reasoning (cf. McLean & Lilgendahl, 2008) and no research has examined reminiscence functions in relation to wisdom. We argue that a person’s reasons for self-reflection influences how they go about reflecting on the past from a behavioral perspective. Specifically, we propose that the basic motivational desire to explore the self (i.e., self-function) will induce an individual to engage in exploratory processing. If this is true, exploratory processing should mediate the positive relationship between the self-function and wisdom. Importantly, this mediational analysis will reveal how motivational and behavioral aspects of self-reflection work together to possibly promote the development of wisdom.

Summary of Hypotheses

This study is the first to comprehensively assess the relationship between self-reflection and wisdom. We examined individual differences in functional (i.e., reminiscence functions) and behavioral (i.e., autobiographical reasoning) aspects of self-reflection in a lifespan sample whose wisdom was assessed using three methods. Although each of the wisdom assessment methods may be tapping somewhat distinct aspects of the construct, we expect them to be positively associated (Glück et al., 2013), and with this common variance in mind, we present our hypotheses in a holistic manner, rather than presenting specific hypotheses for each of the wisdom measures. We expected that:

-

1

Frequency of self-reflection would be unrelated to wisdom.

-

2

Self and directive reminiscence functions would be positively associated with wisdom.

-

4

Exploratory processing, but not redemptive processing, would be positively associated with wisdom.

-

5

Exploratory processing and redemptive processing would interactively predict wisdom.

-

6

Exploratory processing, but not redemptive processing, would be positively associated with a measure of psychological well-being representing growth.

-

7

Redemptive processing, but not exploratory processing, would be positively associated with a measure of psychological well-being representing adjustment.

-

8

Exploratory processing would mediate the relationship between the self-function and wisdom.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 47 wisdom nominees and 47 parallel control participants matched for age and gender to the nominees (N = 94). The nomination procedure is described below. The wisdom nominees were 23 women and 24 men aged 26 to 92 years (M = 60.9, SD = 16.3). Of the nominees, 57.4% were married or living with a partner, 38.3% had a university degree, and 42.6% were retired. The parallel control group included 23 women and 24 men aged 26 to 84 years (M = 60.0, SD = 15.1), of whom 63.9% were married or living with a partner, 8.5% had a university degree, and 57.4% were retired. This dataset has been used in other publications to answer questions about wisdom (e.g., Glück et al., 2013; König & Glück, 2014).

Procedure

Participants came into the laboratory for two interview sessions, with exception to a few older participants who were interviewed at home or a place of their choice. Participants completed questionnaires before and between the two sessions. In the first session, they completed a wisdom performance task and an interview about the most difficult event in their life. For the present study, we did not use data collected at the second interview. Each interview lasted for an average of 1.5 hours, with a range of 1 to 4 hours. Participants were compensated €70 (about $100 USD) for completing both sessions.

Measures and Materials

All but two scales were translated into German for this study and then back-translated by native English and German speakers to optimize translation (the Three-Dimensional Wisdom Scale was translated to German by the scale author and the Psychological Well-Being Scale was translated for a previous study). Participants’ data were included in the computation of scale scores when they responded to at least 80% of the items.

Wisdom

There is debate in the literature concerning the best way to measure wisdom (see Glück et al., 2013). Researchers have approached the assessment of wisdom using self-report questionnaires, performance tasks, and nomination procedures. Given that no single operationalization is consensually recognized as dominant in the field, we assessed wisdom using all three methods, incorporating correlational and group-comparison approaches into our analytic strategy. Our first method for assessing wisdom involved comparisons across the wisdom nominee and parallel control groups. The second approach involved the administration of three self-report wisdom questionnaires. Finally, the third approach required participants to complete a performance task that was scored for wisdom-related knowledge. Self-report questionnaires assessed personal wisdom, whereas the performance measure that we used assessed general wisdom1 (Staudinger & Glück, 2011). This design provided maximum coverage of current measurement models and addressed the issue of method variance. Intercorrelations among the wisdom measures, internal consistencies of the wisdom scales, and inter-rater reliability coefficients for the scoring of wisdom performance are presented in Table 2 of Glück et al. (2013, p. 7).

Wisdom nomination. In newspaper articles and radio broadcasts about the research project, people who thought they knew a highly wise person were invited to contact the project team. We considered it important for the nomination procedure to be based on the nominators’ lay theories of wisdom, rather than on a definition of wisdom provided by the researchers, because we wanted to avoid circularity (if we had mentioned any particular criteria such as reflectivity, nominations would probably have been in line with those criteria). Therefore, the media calls emphasized that we did not have a fixed definition of wisdom. For the same reason, nominations were not screened for any specific criteria. The only exception was that self-nominations were not accepted. The most frequent reasons nominators gave for their nominations concerned cognitive competencies (e.g., knowledge, life experience, problem-solving, intelligence), concern for others (e.g., sensitivity, generosity, helping, guidance), positive attitudes (e.g., humor, trust, positive thinking), and transcendence (e.g., spirituality, feeling connected to nature). In total, 82 nominations were made and 47 of the nominees agreed to participate. Most control participants were recruited through a commercially available random sample of about 1,600 Carinthians (a few were recruited through personal contacts of students and colleagues).

The main reason for recruiting wisdom nominees was to increase the likelihood of reaching relatively wise individuals, who are rare by definition. Although the nomination variable is interesting in that it reflects lay rather than expert theories of wisdom, it is probably not a particularly valid indicator, given that the degree of familiarity between nominee and nominator was highly variable (ranging from one brief encounter to a father nominating his son) and the reasons for nomination were not always highly convincing. As a result, we give more credence to the full-sample analyses involving self-report and performance measures, which are described next.

Self-report measure of wisdom. Wisdom was measured with three Likert-style self-report questionnaires that asked respondents to rate various wisdom-related statements for their degree of self-descriptiveness. The three questionnaires included the Three-Dimensional Wisdom Scale (3D-WS; Ardelt, 2003), the Self-Assessed Wisdom Scale (SAWS; Webster, 2003, 2007), and the Adult Self-Transcendence Inventory (ASTI; Levenson, Jennings, Aldwin, & Shiraishi, 2005). The 39-item 3D-WS conceives of wisdom as the integration of cognitive (14 items; e.g., “You can classify almost all people as either honest or crooked”; reversed), reflective (12 items; e.g., “I always try to look at all sides of a problem”), and affective/compassionate (13 items; e.g., “Sometimes I feel a real compassion for everyone”) personality characteristics. The 40-item SAWS assesses wisdom according to five 8-item dimensions including: critical life experience (e.g., “I have overcome many painful events in my life”), emotional regulation (e.g., “I am good at identifying subtle emotions within myself”), reminiscence and reflectiveness (e.g., “I often think about my personal past”), humor (e.g., “I try to find the humorous side when coping with a major life transition”), and openness (e.g., “I like being around persons whose views are strongly different from mine”). For this study we excluded the reminiscence and reflectiveness subscale because it overlapped with aspects of our other self-reflection variables (e.g., reminiscence functions). Finally, the 25-item ASTI measures self-transcendent wisdom, which is defined as a self-expansive process entailing decreased self-concern and increased empathy, understanding, spirituality, and connectedness with past and future generations (e.g., “I feel that my individual life is part of a greater whole”). The three self-report measures were significantly correlated, r(3D-WS—SAWS) = .27, p = .009, r(SAWS—ASTI) = .67, p < .001, r(3D-WS—ASTI) = .41, p < .001. A principal component analysis with promax rotation showed that the scales loaded onto a single factor (eigenvalue of 1.90) that explained 63% of the variance. As a result, we computed the self-report wisdom variable by standardizing and averaging the overall scores on the three questionnaires (Cronbach’s alpha = .70). More information about structural relationships among scales and subscales is provided in Glück et al. (2013).

Performance measure of wisdom. Participants completed a performance measure of wisdom-related knowledge from the Berlin Wisdom Paradigm (BWP; e.g., Smith & Baltes, 1990; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000). Participants verbally responded to the following life dilemma: “In reflecting over their life, people sometimes realize that they have not achieved what they had once wanted to achieve. What could a person consider and do in such a situation?” Responses were transcribed verbatim and rated according to five criteria: factual knowledge, procedural knowledge, lifespan contextualism, value relativism, and recognition and management of uncertainty. Each criterion was rated by two students (10 students in total), who were trained in using the BWP manual (Staudinger, Smith, & Baltes, 1994) and received a payment of €300. They rated each response on a 7-point scale from 1 (“very little correspondence to an ideal response”) to 7 (“very strong correspondence to an ideal response”). The final score was computed as the average of the ten ratings (Cronbach’s alpha = .85). Information about interrater reliability for each wisdom criterion is presented in Glück et al. (2013).

Well-being

Well-being was assessed using the 18-item German short version of Psychological Well-Being Scale (Ryff & Keyes, 1995), used previously in BWP studies (Glück & Baltes, 2006; Staudinger & Baltes, 1996). According to this model, well-being has six facets (each measured with 3 items): autonomy, self-acceptance, positive relationships, environmental mastery, personal growth, and purpose in life. A principal component analysis with promax rotation indicated that the facets loaded onto two components (eigenvalues of 2.34 and 1.13), cumulatively accounting for 58% of the variance. The first component included self-acceptance, environmental mastery, positive relationships, and autonomy (39% of the variance). The second component included personal growth and purpose in life (19% of the variance). These two components reflect adjustment and growth, respectively, allowing us to differentiate between the two pathways of positive personality development discussed by Staudinger and Kunzmann (2005). Subscales for adjustment (Cronbach’s alpha = .71) and growth (Cronbach’s alpha = .60) were computed by averaging the well-being indicators that loaded on each component.

Reminiscence functions

Reminiscence functions were assessed using 10 items from the Thinking About Life Experiences Scale (Bluck & Alea, 2011). Nine of these items assessed participants’ self-reported reasons for reminiscence. For each reminiscence function item, participants responded to this stem, which was followed immediately by the reminiscence function: “I think back over or talk about my life or certain periods of my life when…” Responses were made on a scale from 1 (“almost never”) to 5 (“very frequently”). The self-function was assessed with 5 items (e.g., “…when I want to understand how I have changed from who I was before”; Cronbach’s alpha = .87), and the directive function with 4 items (e.g., “…when I want to learn from past mistakes”; Cronbach’s alpha = .88). A single item assessed frequency of self-reflection in general (“In general, how often do you think back over your life?”), using the same response scale.

Difficult life event interview and narrative coding

Trained graduate students interviewed participants about the most difficult event in their life. The interviewers first asked the participant to provide an event narrative, and then asked follow up questions concerning how the participant dealt with the situation, how they felt at the time, what impact the event had on their further life, what lessons they learned from the experience, what they would do differently today, what advice they would give someone else in their situation, how they feel about the event looking back on it, and how often they think and talk about the event in the present.

Three trained research interns scored the full interview transcripts (event narrative and follow-up prompts) for four autobiographical reasoning processes: meaning-making, personal growth, emotional processing, and resolution. Raters were unaware of the research hypotheses and participant characteristics (e.g., wisdom nominee or control group). The transcripts were coded in three waves with inter-rater reliability assessed after each wave to assess coder drift (Syed & Nelson, 2015; Wolfe, Moulder, & Myford, 2000). Within each wave, the transcript order was randomized across raters. The autobiographical reasoning processes were scored simultaneously. For each process, the average score of the three raters were used in the final analyses. Inter-rater reliability is reported in Table 1 (intraclass correlation coefficients using two-way random model). Two participants did not report a difficult life event, reducing the overall sample to 92. Narrative excerpts have been provided in Table 2 to illustrate high and low scores on the autobiographical reasoning processes.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics, Reliabilities, Intercorrelations, and Component Loadings for Autobiographical Reasoning Processes (N = 92).

| Autobiographical reasoning process | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M (SD) | Possible Range | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Meaning-making | - | 2.14 (.67) | 0-3 | .64 | |||

| 2. Personal growth | .65** | - | 1.58 (.87) | 0-3 | .80 | ||

| 3. Emotional processing | .11 | .23* | - | 3.24 (1.04) | 1-5 | .89 | |

| 4. Resolution | -.07 | -.01 | .57** | - | 4.10 (.94) | 1-5 | .77 |

| Component loadings | |||||||

| Exploratory processing | .91 | .90 | -.15 | .15 | - | - | - |

| Redemptive processing | -.07 | .07 | .90 | .87 | - | - | - |

Note.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ICC = Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (two-way random effects model using an absolute agreement definition).

Table 2. Narrative Excerpts Illustrating High and Low Scores on the Exploratory Processing and Redemptive Processing Coding Systems.

| Coding system | Score | Quotation from participant |

|---|---|---|

| Exploratory processing | High | “I learned trust and acceptance. I am still learning. I am learning the whole time. I say very often that my oldest son is my greatest teacher. It is – it concerns the daily living, it concerns the direction in life, it concerns how we walk through life, yes. It is just how he lives, he needs so much time. He needs time for many things. And there I’m thinking – I’m just thinking, how we hustle through life, how we think everything is important, things that actually are not important for life at all. I just realize that with attending my son’s life, I am in a constant learning process… I think this gave me strength. Of course I think I had dispositions and I think I grew up in a very positive way. I mean, I have lost a lot – or most – of my fears. I really started to have trust in life. I know it sounds strange.” |

| Low | “I learned that I want to die healthy. But I would have had this goal even if this event had not occurred. So it maybe just reinforced or affirmed it… Consequences, yes, one thing changed. I still have a hard time moving into a residential home for the elderly.” | |

| Redemptive processing | High | “I have a very positive attitude. A positive attitude. I thank my organs that they are working well. Yes, you have to be grateful. It is not a matter of course. But in retrospect I am glad that I had cancer. I am thankful. Feelings of gratitude… I do not think about cancer itself anymore. That is done. It is in the past. It doesn’t make sense to give in to the fear it could come back.” |

| Low | “It is still very hard. And it comes up often [crying]. I am still sad. It is just – I miss them so much.” |

Indicators of exploratory processing. Exploratory processing scores were derived from two autobiographical reasoning processes: (1) meaning-making and (2) personal growth. Meaning-making was defined as a reflective process through which individuals gained self- or life-insight by exploring the significance of a life event. In our study, meaning was scored when the narrator described a conceptual shift in understanding as a result of their difficult life event. In reflection on the event, the narrator developed a deeper or broader perspective on his or her self, relationships, life, or the world. Meaning-making varied in its sophistication or development. This variation was scored on a 4-point scale according to how elaborate, impactful, reflective, and complex the meaning was. A score of 0 was assigned to participants who did not report any meaning gained from their difficult life event. Narratives that lacked meaning were purely descriptive, focusing solely on event reconstruction, rather than exploring potential lessons and insights gained from the experience. A score of 3 was assigned to meanings that were described in rich detail, reported as personally significant, involved explicit references to reflection, and were complex (e.g., examined from multiple perspectives). This approach to scoring meaning was heavily influenced by the work of McLean (e.g., McLean, 2005; McLean & Pratt, 2006; McLean & Thorne, 2003) and similar coding schemes (Blagov & Singer, 2004; Cox & McAdams, 2014).

Personal growth referred to any self-enhancing change, development, or transformation that was causally attributed to a life event. In narratives where personal growth was present, the narrator reported becoming stronger, healthier, better, or more mature as a result of the life event. The narrator openly explored how the life event led to positive self-development, such as the clarification of values or goals, the acquisition of new skills or abilities, or a positive shift in one’s personality. Personal growth did not require a positive emotional appraisal in order to be scored; the focus of this scheme was the elaboration and complexity of the growth, rather than the intensity of positive emotions associated with it. Personal growth was scored on a 4-point scale according to how elaborate, impactful, complex, and transformative it was. A score of 0 was assigned to participants who reported no personal growth whatsoever as a result of their difficult life event. A score of 3 meant that growth was a strong theme in the difficult life event, and was described in rich detail, reported as personally important, and led to significant positive self-development. This coding scheme was based on the work of Pals (2006b) and Lilgendahl and McAdams (2011).

Indicators of redemptive processing. Redemptive processing scores were derived from two autobiographical reasoning processes: (1) emotional processing (i.e., positive reframing) and (2) resolution. Emotional processing concerned how positively or negatively an individual interpreted the emotional impact of a life event from the standpoint of the present. This measure was purely concerned with affect—how positively or negatively the individual felt about the difficult life event when looking back on it today. The emotional processing score was based on the narrator’s own subjective characterization of the emotional impact of the event on the self, as reflected in their internal thoughts and feelings (e.g., happiness, pride, gratitude, regret, sadness, anger). Emotional processing did not concern the overall emotional tone of the narrative or the valence of the event itself. Emotional processing was scored on a 5-point bipolar scale from -2 (“very negative”) to +2 (“very positive”). A score of -2 or +2 meant that the expression of positive or negative emotion was vivid, elaborate, and strong—the event had a profound emotional impact on the narrator. A score of 0 was assigned to narratives that were neutral (no emotional impact reported) or mixed (equal parts positive and negative). This coding scheme was based on the work of Pals (2006b) and Lilgendahl and McAdams (2010).

Resolution concerned the extent to which an individual reported continued processing of the difficult life event in the present. When an event was resolved, the reporter communicated a sense of closure around the event. The narrator had ‘come to terms with’ or ‘moved on’ from the experience. The event was emotionally distant from the narrator, and any emotional wounds had long since healed. For unresolved events, the narrator was still actively trying to understand and come to terms with the event. They appeared ‘stuck’ in the event. They reported often thinking or talking about the difficult life event in the present, and were still grappling with the event emotionally. Resolution was scored on a 5-point bipolar scale from 1 (“very unresolved”) to 5 (“very resolved”). This coding scheme was based on the work of Mansfield, McLean, and Lilgendahl (2010) and Pals (2006b). An inspection of normality revealed that the resolution variable was negatively skewed; this was corrected with an appropriate logarithmic transformation.

Structural relationships among autobiographical reasoning processes. To assess shared variance among the four autobiographical reasoning processes, we conducted a principal component analysis with a promax rotation (see Table 1 for intercorrelations and component loadings based on the pattern matrix). We found that 82% of the variance was accounted for by two components (eigenvalues of 1.77 and 1.50). As expected, meaning-making and personal growth loaded on a component that we labeled exploratory processing (44% of variance), and emotional processing and resolution loaded on a second component that we labeled redemptive processing (38% of variance). This factor structure replicates the findings of King et al. (2000), Lodi-Smith et al. (2009), and Pals (2006b). To summarize, exploratory processing reflects the narrator’s attempt to understand the deeper personal meaning of an event, with an emphasis on positive self-transformation. The hallmark of exploratory processing is in the explanation, evaluation, and analysis of the event’s meaning, in contrast to a purely descriptive account of the event’s unfolding. Redemptive processing concerns the narrator’s effort to emotionally transform an initially negative experience into a positive one. By assigning a happy ending to the event, the narrator secures a sense of emotional closure and is able to move on from the event psychologically. Composite scores for exploratory and redemptive processing were computed by standardizing and averaging the two narrative indicators that loaded on each component. The meaning-making and personal growth indicators were positively correlated at a magnitude of r (92) = .65, p = < .001 (Cronbach’s alpha = .79 for exploratory processing scale), and the emotional processing and resolution indicators were positively correlated at r (92) = .57, p = < .001 (Cronbach’s alpha = .73 for redemptive processing scale).

Control variables

In addition to age, we collected measures of fluid and crystallized intelligence as potential covariates of wisdom and self-reflection. Fluid intelligence was assessed with a measure of inductive reasoning, specifically the 15-item Matrices subtest of the German CFT-20-R (Weiss, 2008). Crystallized intelligence was assessed using a 37-item multiple-choice vocabulary test from the German “Mehrfachwahl-Wortschatz-Intelligenztest” (Lehrl, 2005).

Results

Background Analyses

As reported in Glück et al. (2013), wisdom nominees scored higher on performance wisdom than control participants. Using the self-report wisdom composite that we constructed for this study, a univariate analysis of variance indicated that wisdom nominees also scored higher on self-report wisdom, F(1) = 13.58, p < .01, ηp2 = .13, than did control participants. The self-report wisdom composite had a moderate positive association with performance wisdom, r(94) = .30, p < .01. In summary, the three measures of wisdom were positively related to each other, suggesting that wisdom is a relatively coherent construct across methods, although not similar enough to justify the construction of an overall composite wisdom score that integrates the measurement approaches. There are also theoretical reasons to preserve the personal and general wisdom distinction. We did not control for group membership when conducting correlational analyses using the full sample, because we did not want to limit potentially meaningful variation in self-report and performance indicators of wisdom (i.e., even though wisdom nominees scored higher on average than control participants on self-report and performance wisdom, there was still variation in wisdom scores within each group). Our goal was to examine each of the three methods for assessing wisdom independent of the others.

Glück et al. (2013) reported that wisdom nominees scored higher on a measure of crystallized intelligence (vocabulary) than control participants, but did not differ in fluid intelligence (inductive reasoning). As a result, we controlled for vocabulary in all analyses involving group comparisons. Also reported in Glück et al., performance wisdom was unrelated to age of the participant and both crystallized and fluid intelligence (see Glück et al. for more information). In our study, both types of intelligence and age were unrelated to self-report wisdom, the frequency of self-reflection, reminiscence functions, and autobiographical reasoning processes, obviating the need to control for any of these variables in subsequent analyses. Correlations among main study variables and control variables are summarized in Table 3. It is notable that autobiographical reasoning was unrelated to crystallized and fluid intelligence, since one could reasonably argue that the capacity for more complex types of self-reflection, such as exploratory processing, may require a certain degree of intelligence.

Table 3. Summary of Correlations Among Study Variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Frequency of self-reflection | - | |||||||||||

| Reminiscence functions | ||||||||||||

| 2. Self-function | .70** | - | ||||||||||

| 3.Directive function | .57** | .69** | - | |||||||||

| Autobiographical reasoning processes | ||||||||||||

| 4.Exploratory processing | .18 | .28** | .18 | - | ||||||||

| 5.Redemptive processing | -.36** | -.18 | -.08 | .08 | - | |||||||

| Wisdom | ||||||||||||

| 6. Self-report wisdom | .12 | .26* | .17 | .44** | .22* | - | ||||||

| 7. Performance wisdom | .19 | .22* | .22* | .30** | -.12 | .30** | - | |||||

| Psychological well-being | ||||||||||||

| 8. Growth pathway | .16 | .13 | .14 | .19 | .06 | .23* | .14 | - | ||||

| 9. Adjustment pathway | -.22* | -.22* | -.14 | .16 | .31** | .47** | .04 | .33** | - | |||

| Control variables | ||||||||||||

| 10. Age | .06 | .08 | .01 | -.15 | -.02 | -.10 | -.13 | -.33** | -.20 | - | ||

| 11. Crystallized intelligence | -.05 | .10 | -.04 | .01 | .04 | .16 | .16 | -.20 | -.14 | .46** | - | |

| 12. Fluid intelligence | -.16 | -.03 | .00 | -.01 | -.03 | .09 | .08 | .26* | -.03 | -.45** | .03 | - |

Note.

*p < .05.**p < .01.

Frequency of Self-Reflection and Wisdom

We first examined group differences in frequency of self-reflection across the wisdom nominee and parallel control group. Consistent with our hypothesis, a univariate analysis of variance, controlling for vocabulary, indicated that wisdom nominees reported equivalent levels of self-reflection to control participants, F(1) = .61, p = .437. Next we conducted correlational analyses using the self-report and performance measures of wisdom. Similar to the group-comparison analysis, we found that self-reported wisdom, r(89) = .12, p = .265, and performance wisdom, r(89) = .19, p = .081, were unrelated to the frequency of self-reflection. Together, these findings support our proposal that mere quantity of self-reflection is unrelated to wisdom.

Reminiscence Functions and Wisdom

Unexpectedly, wisdom nominees and control participants did not differ in their self-reported reasons for reminiscence. A multivariate analysis of variance indicated that the groups were equally likely to report reminiscing for the self-function, F(1) = .10, p = .753, and directive function, F(1) = .03, p = .868, controlling for vocabulary.

To predict self-report wisdom and performance wisdom from the two reminiscence functions, we ran stepwise regression analyses in order to identify the shared and unique variances contributed by each function (cf., Staudinger, Lopez, & Baltes, 1997). As the two reminiscence functions were highly correlated (r = .69, p < .001), it is not surprising that the main part of explained variance was shared by the two predictors. In the case of performance wisdom, each reminiscence function was a significant predictor when it was added into the equation first (self-function: 4.9% of the variance, p = .038; directive function: 4.7%, p = .042), but neither was significant when added second (self-function: 1.0%, p = .350; directive function: 0.8%, p = .402). Thus, the main part of the explained variance (3.9%) was shared by both predictors. For self-report wisdom, only the self-function was a significant predictor when included first (5.8%, p = .024), the directive function added zero explained variance in this case (p = .982). When the directive function was included first, it also explained only an insignificant share (2.7%, p = .125) of the variance. Thus, self-reported wisdom was predicted by the self-function (unique share: 3.1% of the variance), but not the directive function of wisdom.

Autobiographical Reasoning, Wisdom, and Well-Being

The next set of analyses examined the relations among autobiographical reasoning, wisdom, and two dimensions of well-being. First, exploratory and redemptive processing were uncorrelated, r(92) = .08, p = .465, suggesting that these are distinct, but not mutually exclusive, modes of processing the past. Next, we tested our hypothesis that wisdom would be positively related to exploratory processing and unrelated to redemptive processing. Using a multivariate analysis of variance, we examined mean differences in exploratory and redemptive processing across wisdom nominees and control participants, while controlling for vocabulary. Wisdom nominees scored higher on both exploratory processing, F(1) = 4.63, p = .034, η p2 = .05, and redemptive processing, F(1) = 6.92, p = .010, ηp2 = .07, than control participants. To examine the association between autobiographical reasoning and self-report and performance wisdom, we conducted two hierarchical multiple regression analyses, with exploratory and redemptive processing entered simultaneously in step one of the model and their interaction term entered in step two. Results are summarized in Table 4. As hypothesized, exploratory processing, but not redemptive processing, was positively associated with self-report and performance wisdom. Together, the exploratory and redemptive processing explained 23% of the variance in self-report wisdom and 11% of the variance in performance wisdom. The interaction term failed to predict self-report and performance wisdom.

Table 4. Hierarchical Multiple Regression Models Predicting Wisdom and Well-Being from Autobiographical Reasoning Processes.

| Self-report wisdom | Performance wisdom | Adjustment pathway | Growth pathway | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔR2 | B (SE) | β | ΔR2 | B (SE) | β | ΔR2 | B (SE) | β | ΔR2 | B (SE) | β | |

| Step 1 | .23** | .11** | .11** | .04 | ||||||||

| Exploratory processing | .47 (.10) | .43** | .35 (.11) | .31** | .09 (.07) | .14 | .15 (.09) | .18 | ||||

| Redemptive processing | .21 (.11) | .18 | -.16 (.11) | -.14 | .20 (.07) | .30** | .05 (.09) | .05 | ||||

| Step 2 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .00 | ||||||||

| Interaction | -.08 (.12) | -.06 | -.09 (.13) | -.07 | -.09 (.09) | -.12 | .03 (.11) | .03 | ||||

Note. *p < .05. **p < .01.

In an effort to contrast wisdom with an alternative, yet highly desirable developmental outcome, we examined the relations between autobiographical reasoning and two facets of psychological well-being, specifically, adjustment and growth. Following the same approach as the previous analyses, we conducted two hierarchical multiple regressions with adjustment and growth as criterion variables (see Table 4). Supporting our predictions, adjustment was positively associated with redemptive processing and unrelated to exploratory processing. Growth was unrelated to redemptive processing and, unexpectedly, also unrelated exploratory processing. Similar to wisdom, the interaction term failed to predict adjustment and growth.

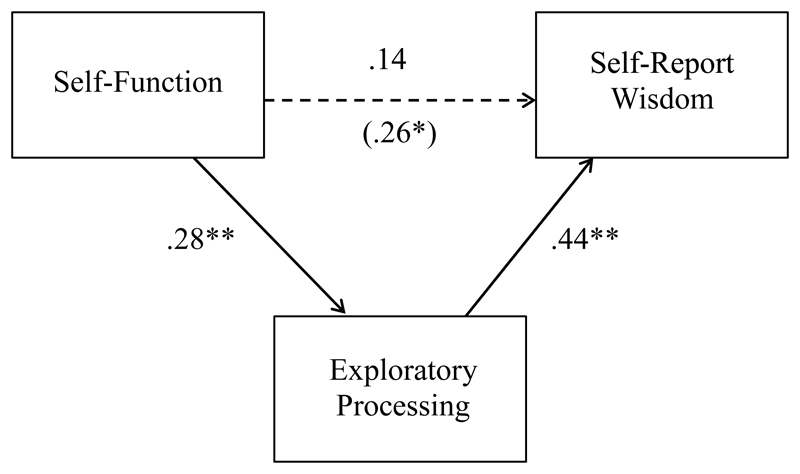

Mediation Analysis: Self-function, Exploratory Processing, and Wisdom

Integrating across analyses, we hypothesized that exploratory processing would mediate the positive association between the self-function and wisdom. We speculated that reflecting for the purpose of self-understanding might represent the motivational basis for engagement in exploratory processing, which was positively correlated with the self-function, r(87) = .28, p = .008. In other words, individuals who are motivated to inspect how they have changed as a result of a life experience would be more likely to engage in the type of self-reflective exploration that may eventually lead to wisdom. To test the indirect pathway we conducted a mediation analysis (see Baron & Kenny, 1986). The significant association between the self-function and self-report wisdom, β = .26, p = .014, was reduced to a non-significant level, β = .14, p = .163, when exploratory processing was entered into the model. Similarly, for performance wisdom, the relationship between the self-function and wisdom, β = .22, p = .040, became non-significant, β = .15, p = .175, when exploratory processing was entered as a mediator. Since the relations between the self-function and both indicators of wisdom were small to begin with, we conducted Sobel tests to determine if the modest reductions in size of the regression coefficients reflected a significant change. Sobel tests indicated that exploratory processing mediated the relationship between the self-function and self-report wisdom, Sobel z = 2.31, p = .021, but not performance wisdom, Sobel z = 1.82, p = .069 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mediation model depicting full mediation of the relationship between the self-function and self-report wisdom by exploratory processing. Values represent standardized regression coefficients. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Discussion

This study investigated relations among self-reflection and wisdom. Self-reflection was examined from functional and behavioral perspectives. Participants reported their reasons for reflecting on the past (i.e., self and directive reminiscence functions) and provided an autobiographical memory of a difficult life event, which was scored for different forms of autobiographical reasoning. Wisdom was assessed using self-report, performance, and nomination approaches. Across three methods for assessing wisdom, wisdom was unrelated to the frequency of self-reflection, but positively related to exploratory processing of difficult life experience. Wisdom nominees also scored higher on redemptive processing than control participants, which was unexpected. At zero-order, self-report wisdom was positively associated with redemptive processing, but this relationship became non-significant when exploratory processing was included in the regression model. Exploratory processing and redemptive processing did not interact to predict wisdom. Redemptive processing was positively related to psychological adjustment, but, surprisingly, exploratory processing was unrelated to growth. Self-report and performance wisdom were positively related to the self-function of reminiscence, but only performance wisdom was related to the directive function. Finally, exploratory processing mediated the relationship between the self-function and self-report wisdom.

The findings of this study are consistent with the proposal that self-reflective processes support growth in wisdom through life experience. Results showed that wisdom was unrelated to the general frequency of self-reflection, but positively associated with the self and directive reminiscence functions, and with exploratory and redemptive processing in autobiographical narratives of difficult life events. These findings support the idea that how and why individuals self-reflect matters more for wisdom than how much they reflect. Although the strength of some of these associations was relatively small, they should not be underestimated given the diverse self-report, performance (e.g., think-aloud task, narrative coding), and nomination methods used.

Results varied somewhat across three methods for assessing wisdom. For example, reminiscence functions did not differ across the wisdom nominee and control groups, but positive associations did exist between the reminiscence functions and the performance and self-report measures of wisdom. The divergences across methods may reflect discrepancies in how wisdom internally and externally manifests. That is, the criteria for what makes a person internally wise may differ from its outward expression, as perceived by others. The general public may, for example, consider the ability to redeem a negative life event to be quite emblematic of wisdom. Although this remains anecdotal, when nominators were asked about why they had nominated a particular person as wise, one of the recurring themes in their responses was that wisdom nominees had experienced terrible life events yet were still happy despite this hardship. This would also explain why wisdom nominees scored higher on redemptive processing than control participants. Although the question about ‘who knows who is wise’ is an important one (Redzanowski & Glück, 2013), we consider the nomination approach, at least in the way it was used in the current study, as somewhat more dubious than the other methods, given the inability to control for nomination criteria. With that said, Glück et al. (2013) found that, on average, wisdom nominees scored higher on wisdom measures than the parallel control group, which suggests that it has some validity as a method for identifying wisdom.

It was also surprising that, at zero-order, redemptive processing was positively related to self-report wisdom (as expected, it was unrelated to performance wisdom). This discrepancy may be due to the relative emphasis on affective processes, which are more prominent in self-report than performance methods (e.g., Ardelt, 2003; Levenson et al., 2005; Webster, 2007). Moreover, self-report wisdom measures may somehow capture an illusory positive self-view that is also related to redemptive processing. Individuals who respond in a socially desirable manner to the self-report measures may also be inclined to narrate a difficult life event in excessively positive terms. McAdams (2006a, b) has discussed the cultural pressure placed on individuals to tell redemptive stories, at least within the context of North American society, but this could be reasonably extrapolated to other Western cultures, such as Austria. Redemptive stories are the most culturally acceptable stories to tell, and could therefore be, in part, motivated by social desirability.

Across the self-report, performance, and nomination approaches, exploratory processing remained positively associated with wisdom, indicating a robust relationship. This finding represents a significant advancement in our understanding of the psychological processes that may support wisdom development. It empirically confirms the theorizing of many researchers who have pointed to the role of self-reflection in cultivating and exercising wisdom.

Positive Developmental Pathways Following Adversity

People respond to life events in a range of adaptive and maladaptive ways, and those responses, in combination with other personal and social factors, determine long-term psychological outcomes. Among the positive outcomes, theorists have differentiated between adjustment and growth (Staudinger & Kessler, 2009; Staudinger & Kunzmann, 2005). Adjustment entails the maintenance or promotion of happiness following a life event, whereas growth encompasses psychological maturation and elevated wisdom. In this study, we had two indicators of psychological well-being representing growth and adjustment, as well as three indictors of wisdom. Our study found that one predictor, and possible developmental predecessor, of wisdom is self-reflection, specifically, autobiographical reasoning. Redemptive processing may represent a pathway to adjustment, and exploratory processing a pathway to wisdom. Wisdom-fostering forms of self-reflection require that individuals explore their own role in the occurrence of negative life events, confront and examine negative feelings, and do the effortful work of finding meaning in the difficult experience. This type of self-reflection is rare, probably because it is less pleasant than other processing modes. In the longer-term, it is possible that exploratory processing might lead to increases in well-being; however, the more direct pathway to happiness would be redemptive processing, which, we speculate, poses less psychological risk to the person. Surprisingly, exploratory processing was unrelated to the psychological well-being subscale that represented the growth pathway. Growth was also uncorrelated with performance wisdom, which is inconsistent with past research (Staudinger, Lopez, & Baltes, 1997; Wink & Staudinger, 2015). This may reflect a limitation of self-report methods when it comes to assessing ambiguous constructs like growth or an artefact of method variance across the self-report measure of growth and narrative measure of exploratory processing. Alternatively, with a sample consisting of 50% wisdom nominees, the growth scores tended to be quite high, which may have resulted in restricted variability.

In general, these findings replicate other research in the field of narrative psychology that has similarly focused on difficult life events (King et al., 2000; King & Patterson, 2000; King & Raspin, 2004; Pals, 2006b), adding wisdom to the growing list of outcomes associated with exploratory forms of narrative processing (e.g., level of ego development, stress-related growth, clinical ratings of psychological maturity). Importantly, these findings are limited to difficult life experiences, because pathway determinants may differ according to event valence. We should be careful not to infer that exploring the meaning of positive life events will lead to wisdom in the same way as it does with negative life events—perhaps it is best to savor, rather than scrutinize, positive life events (Greenhoot & McLean, 2013; King & Hicks, 2009; Lyubomirsky, Sousa, & Dickerhoof, 2006).

Does Self-Reflection Make Wise People or Do Wise People Self-Reflect?

Given the cross-sectional nature of this study, it is impossible to empirically determine whether self-reflection or wisdom comes first. It is likely the case that self-reflection and wisdom have a corresponsive relationship (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). Self-reflection leads to wisdom, and wisdom in turn promotes adaptive self-reflection. Glück and Bluck (2013) have argued that self-reflection, like the other personal resources in the MORE Life Experience Model, is an antecedent of wisdom, coming online long before wisdom actually develops. This makes strong theoretical sense, but to address the circularity of this relationship empirically, longitudinal research is required. The need for longitudinal studies in this area represents both a limitation of the current study and a future direction for this research.

Limitations

The correlational analyses were somewhat underpowered in this study; however, this was offset by two factors. First, collecting wisdom nominees meant that rates of wisdom were comparably higher in our study than other studies with larger sample sizes, meaning there was greater variance in wisdom that could be predicted by self-reflection variables. Second, incurring a cost to power allowed us to examine our research questions quasi-experimentally. Our sample size was limited by the matching procedure used to formulate the parallel control group. Despite this constraint, we view the integration of both correlational and group-comparison approaches to be a significant strength of our study.

Future Directions

This study examined self-reflection as a naturally occurring individual difference. The question remains open as to whether or not self-reflection can be taught. One potential inroad to cultivating wisdom in our society could be to teach individuals how to go about making sense of their life experience in wisdom-fostering ways, such as exploratory processing. Staudinger, Kessler, and Dörner (2006) have conducted some preliminary research in this area, showing that training in structured self-reflection leads to immediate increases in personal wisdom. Future research is needed to address the size and sustainability of this effect over time, and the plasticity of self-reflection in general.

Another line of future research will be to explore the dynamic interactions between self-reflection and other wisdom-related resources. For instance, a degree of openness to experience is likely required to initiate exploratory processing of difficult life experience, and emotion regulation skills are probably necessary to examine adversity from a distanced, yet emotionally-attuned, perspective (Kross & Grossmann, 2012). Thus, the effects of exploratory processing are probably both limited and optimized by the other resources. To understand these interactions, future research should explore the MORE resources dynamically over time. In addition to these internal resources, future research should also examine the extent to which certain external resources contribute to the cultivation of wisdom. For instance, talking with others about important life experiences may help to scaffold wisdom-development processes and provide a context for the social transmission of wisdom. This applies to both everyday conversations and to more structured relationships, such as mentorship and advice-giving scenarios.

Finally, our study utilized a performance measure of general wisdom, which is assessed in think-aloud responses to a hypothetical life dilemma. While unavailable at the time that our study was designed, Staudinger and colleagues (Mickler & Staudinger, 2008; Staudinger, 2013; Staudinger, Dörner, & Mickler, 2005) have since proposed a model of personal wisdom, which concerns the application of wisdom to one’s own life, rather than a fictitious person’s life. We believe that self-reflection should be relevant to both general and personal wisdom, given that reflecting on events in one’s own life should assist one in reasoning wisely about other people’s situations as well, although it may not work the other way around—reflecting on life in general may not lead to increases in personal wisdom. Giving wise advice may be much easier than following that same advice oneself. Future research should explore self-reflection in relation to both general and personal wisdom.

Conclusion

We have great need for wisdom in our world today. Yet, few studies have examined the psychological processes that potentially facilitate its development. Most agree that wisdom is forged from life experience, yet life experience does not guarantee wisdom. The current study suggests that self-reflection is critical to the construction of wisdom from the past. We have shown that levels of wisdom vary as a function of how individuals reflectively process challenging life experiences. Wiser individuals process life challenges in an exploratory manner that emphasizes meaning and growth, even if that process may sometimes be unpleasant. These findings open a new and exciting line of thinking about the development of wisdom, and more broadly, about mechanisms and processes that support growth through personal hardship.

Footnotes

Mickler and Staudinger (2008) have since developed a performance-based measure of personal wisdom that was not available at the time this study began.

References

- Alea N, Bluck S. Why are you telling me that? A conceptual model of the social function of autobiographical memory. Memory. 2003;11:165–178. doi: 10.1080/741938207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alea N, Bluck S. When does meaning making predict subjective well-being? Examining young and older adults in two cultures. Memory. 2013;21:44–63. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2012.704927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardelt M. Empirical assessment of a three-dimensional wisdom scale. Research on Aging. 2003;25:275–324. doi: 10.1177/0164027503025003004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardelt M. Wisdom as expert knowledge system: A critical review of a contemporary operationalizations of an ancient concept. Human Development. 2004;47:257–285. doi: 10.1159/000079154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardelt M. How wise people cope with crises and obstacles in life. ReVision: A Journal of Consciousness and Transformation. 2005;28:7–19. doi: 10.3200/REVN.28.1.7-19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ardelt M. Are older adults wiser than college students? A comparison of two age cohorts. Journal of Adult Development. 2010;17:193–207. doi: 10.1007/s10804-009-9088-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle . In: Nicomachean ethics. Broadie S, Rowe C, translators. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Staudinger UM. A metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. American Psychologist. 2000;55:122–136. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Kunzmann U. The two faces of wisdom: Wisdom as a general theory of knowledge and judgment about excellence in mind and virtue vs. wisdom as everyday realization in people and products. Human Development. 2004;47:290–299. doi: 10.1159/000079156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Lindenberger U, Staudinger UM. Life span theory in developmental psychology. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development. 6th ed. New York, NY: Wiley; 2006. pp. 569–664. [Google Scholar]

- Baron MR, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagov PS, Singer JA. Four dimensions of self-defining memories (specificity, meaning, content, and affect) and their relationships to self-restraint, distress, and repressive defensiveness. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:481–511. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluck S, Alea N. Exploring the functions of autobiographical memory: why do I remember the autumn? In: Webster JD, Haight BK, editors. Critical advances in reminiscence: From theory to application. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bluck S, Alea N. Thinking and talking about the past: Why remember? Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2009;23:1089–1104. doi: 10.1002/acp.1612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bluck S, Alea N. Crafting the TALE: Construction of a measure to assess the functions of autobiographical remembering. Memory. 2011;19:470–486. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2011.590500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluck S, Alea N, Habermas T, Rubin DC. A tale of three functions: The self-reported uses of autobiographical memory. Social Cognition. 2005;23:91–117. doi: 10.1521/soco.23.1.91.59198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bluck S, Glück J. Making things better and learning a lesson: Experiencing wisdom across the lifespan. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:543–572. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluck S, Glück J. From the inside out: People’s implicit theories of wisdom. In: Sternberg RJ, Jordan J, editors. A handbook of wisdom: Psychological perspectives. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 84–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bluck S, Liao H-W. I was therefore I am: Creating self-continuity through remembering our personal past. The International Journal of Reminiscence and Life Review. 2013;1:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL. Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:453–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox K, McAdams DP. Meaning making during high and low point story episodes predicts emotion regulation two years later: How the past informs the future. Journal of Research in Personality. 2014;50:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2014.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M, Weststrate NM, editors. The scientific study of personal wisdom: From contemplative traditions to neuroscience. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; 2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M, Weststrate NM, Petro A. Stories of wisdom to live by: Developing wisdom in a narrative mode. In: Ferrari M, Weststrate NM, editors. The scientific study of personal wisdom: From contemplative traditions to neuroscience. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; 2013. pp. 137–164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glück J, Baltes PB. Using the concept of wisdom to enhance the expression of wisdom knowledge: Not the philosopher’s dream but differential effects of developmental preparedness. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21:679–690. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]