Abstract

Background:

Drug eluting stents (DES) reduce the risk of restenosis in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, but their use necessitates prolonged dual anti-platelet therapy, which increases costs and bleeding risk, and which may delay elective surgeries. While >80% of patients in the U.S. receive DES, less than a third report that their physicians discussed options with them.

Methods and Results:

An individualized shared decision-making (SDM) tool for stent selection was designed and implemented at 2 U.S. hospitals. In the post-implementation phase, all patients received the SDM tool prior to their procedure, with or without decision coaching from a trained nurse. All patients were interviewed with respect to their knowledge of stents, their participation in SDM, and their stent preference. Between May 2014 and December 2016, 332 patients not receiving the SDM tool, 113 receiving the SDM tool with coaching, and 136 receiving the tool without coaching were interviewed. Patients receiving the SDM tool + coaching, as compared with usual care, demonstrated higher knowledge scores [mean difference +1.8 p<0.001], reported more frequent participation in SDM [OR=2.96; p<0.001], and were more likely to state a stent preference [OR 2.00 p<0.001]. No significant differences were observed between use of the SDM tool without coaching and usual care. For patients who voiced a stent preference, concordance between stent desired and stent received was 98% for patients who preferred DES and 50% for patients who preferred BMS. The SDM tool (with or without coaching) had no impact on stent selection or concordance.

Conclusions:

A SDM tool for stent selection was associated with improvements in patient knowledge and SDM only when accompanied by decision coaching. However, the SDM tool (with or without coaching) had no impact on stent selection or concordance between patients’ stent preference and stent received, suggesting that physician-level barriers to SDM may exist.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier – NCT02046902; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02046902

Journal Subject Terms: Coronary Artery Disease, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Stent, Restenosis, Revascularization

Keywords: coronary artery disease, percutaneous coronary intervention, drug-eluting stent, bare metal stent, shared decision-making

Background

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is performed >600,000 times/year in the US alone for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).1 Nevertheless, restenosis requiring target vessel revascularization (TVR) remains a concern. The use of drug-eluting stents (DES) is associated with a 50% reduction in TVR as compared with bare-metal stents (BMS).2, 3 However, DES do not improve survival or long-term quality of life4, 5 and the magnitude of benefit of DES in reducing restenosis is dependent on a patient’s underlying restenosis risk.6, 7 Importantly, DES use necessitates 6–12 months of dual anti-platelet therapy (DAPT) to minimize the risk of stent thrombosis, while as little as 1 month of DAPT may be safe for patients treated with BMS.8 DAPT represents an increased medication burden for patients, can be expensive, increases major and nuisance bleeding,9, 10 and can complicate future surgeries.8 When asked, the majority of patients equally value the benefits of TVR avoidance and the drawbacks of DAPT.11 However, despite these trade-offs, DES are used in >80% of PCI cases in the U.S., irrespective of patients’ risk for restenosis.12, 13

When more than one clinically acceptable treatment is available, engaging patients in shared decision-making (SDM) can improve the value of health care.14, 15 In the setting of PCI, stent selection should be a preference-sensitive decision because of the offsetting benefits of DES and the drawbacks of prolonged DAPT. However, only 10% of patients undergoing PCI are presented with other options, only 19% are presented with the “cons,” and only 16% are asked about their treatment preferences.16 Collectively, these data suggest that stent selection is an ideal situation in which to test strategies for implementing SDM into routine care. Therefore, we developed a SDM tool for stent selection and hypothesized that it would improve engagement in SDM for patients undergoing PCI.

Methods

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure; however the study investigators are open to collaborating with researchers who wish to consider further analysis of these data.

Study Design:

Creation of the SDM Tool:

The SDM tool was developed with input from the study team, Steering Committee, and providers. The DECIDE Tool was formulated using the criteria for International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS).17 Patient input was solicited through a series of focus groups. In their roles as Steering Committee members, patients and caregivers also assisted with the study design, outcome measures, study conduct, and interpretation of the results. Patients, caregivers, and patient advocates who contributed to this work are listed in the Acknowledgements below.

Using the Patient Risk Information Systems Manager (ePRISM), we implemented a personalized SDM tool to supplement personalized informed consent documents that were previously demonstrated to improve the informed consent process, patient satisfaction,18 and patient participation in SDM with respect to stent selection.19 The SDM tool included each patient’s estimated risks of TVR with BMS and DES by executing a previously published TVR risk model using each patient’s clinical risk factors, without angiographic variables.20 A graphic designer with experience in patient decision aid creation contributed to the visual appeal and layout of the tool. Through a series of presentations at subsequent patient focus groups, the tool evolved into the single-page self-contained DECIDE Tool for use with patients prior to the scheduled coronary angiography with possible revascularization procedure. The text and visual graphic on the 1-page paper form described, in lay terms, the nature of CAD, stents, the decision to be made related to stent type, TVR, DAPT obligations, costs, and risks, resulting in a personalized SDM tool that could be provided prior to angiography (Appendix A).

The impact of the SDM tool was analyzed using a pre-post study design. Between May 2014 and December 2016, patients were recruited from 2 PCI centers, Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute (MAHI) and Truman Medical Center (TMC), following IRB approval at each site. Patients undergoing elective or urgent PCI or coronary angiography with possible PCI (including patients with acute coronary syndrome) were approached prior to their procedure to obtain informed consent for participation in the study at TMC, but MAHI’s IRB considered the study to be Quality Improvement and granted a waiver of written informed consent. Patients undergoing emergent procedures or who could not or did not wish to participate in an SDM discussion were excluded. The SDM tool was administered in the catheterization laboratory “preparatory” area prior to the patient’s procedure. While the SDM tool was designed to be used in conjunction with decision coaching, the allocation of hospital resources to provide decision coaching was a challenge. Therefore, the SDM tool was tested with or without decision coaching to define the best strategy with which to engage patients in SDM and to assess whether or not decision coaching was important, or if merely presenting a personalized SDM tool with the informed consent would suffice. Thus, the study was conducted in three sequential phases, as follows. Phase 1: No SDM tool, in which patients undergoing coronary angiography and possible PCI received an ePRISM consent form prior to their procedure with personalized risk estimates for mortality, bleeding, and TVR with BMS and DES, but neither the SDM tool nor decision coaching; Phase 2: SDM tool with coach, in which patients received the consent form, the SDM tool for stent selection, and decision coaching prior to their procedure; and Phase 3: SDM tool alone, in which patients received the consent form and the SDM tool prior to their procedure, but with no decision coaching. Although there was some variation between sites, Phase 1 lasted approximately 12 months in duration, while Phases 2 and 3 lasted approximately 5 months each in duration.

Decision Coaching Intervention:

The Ottawa Decision Support Framework21 and Motivational Interviewing communication principles were used to develop a 4-hour training curriculum for Decision Coaches. Motivational interviewing principles are well suited for use in SDM because motivational interviewing is considered person or patient-centered and the communication skills are designed to facilitate patient engagement, to elicit the patient’s views regarding the topic, and to express empathy and acceptance.22 Coaching techniques were engineered to facilitate patient understanding of the information contained in the SDM tool, to elicit patients’ questions, and to encourage patients to voice their preferences to their physician. A total of nine Registered Nurses (five bedside nurses from the Cath Lab Holding area and four clinical research nurses) completed the training. However, during the study, >90% of the coaching was done by clinical research nurses to allow for consistency in delivering the SDM tool and greater fidelity in the coaching intervention. Decision Coaches initiated the SDM process by sharing the SDM tool with patients pre-procedurally, before the attending physician obtained informed consent for PCI. The Decision Coaches used Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)/Option Grids to address commonly asked questions, thus blending supportive training to the coaches with personalized estimates for patients. Coaching sessions typically lasted 10–15 minutes in duration but ranged between 5–20 minutes in duration based on the level of patient engagement. At MAHI, decision coaching was performed by 3 research nurses, and when decision coaching was withdrawn, those nurses no longer interacted with patients. At TMC, decision coaching was performed by 3 clinical nurses in the catheterization laboratory, and when decision coaching was withdrawn, those nurses no longer routinely reviewed the SDM tool with patients. Fidelity of the coaching intervention was assessed through periodic site visits by the Study Coordinator, who was trained in the SDM Curriculum and MI communication principles. While feedback was provided, formal audits were not performed. In addition, Decision Coaches attended an Investigator Meeting during which a recorded coaching session and additional patient scenarios were reviewed, to promote consistency in delivery of the intervention.

As part of an implementation strategy to motivate physicians performing PCI procedures to engage in SDM with their patients, Physician Champions at each site were enlisted at each site to engage their colleagues to value SDM. These Physician Champions received training in Motivational Interviewing communication principles so that these techniques could be shared with their colleagues as well. Physicians performing PCI obtained informed consent after the SDM tool with or without coaching were provided to the patient. Physicians were educated on the rationale for the study and its design, but they were not provided with any information from Decision Coaches regarding their conversations with patients, and were not directed to discuss stent selection with patients. However, a copy of the SDM tool was included with the informed consent document for the physician to review, if desired. Patients treated by the Physician Champions at each site were not enrolled in this study, so as not to bias the results.

Study Outcomes

The process and outcomes of SDM were assessed through a post-procedure, pre-discharge interview (Appendix B). The primary outcome was whether or not patients participated in SDM regarding stent choice through a slight modification of a previously validated measure.23 Patients were categorized as having participated in SDM if they answered anything other than “doctor alone” in response to the question “Who chose the type of stent?” Secondary outcomes included patients’ recall of individual aspects of the stent discussion, stent knowledge score (based on number of correct answers to 6 questions assessing knowledge transfer), patient preference for stent type, perceived autonomy support (e.g., perceived interest in patient preferences, support for the patient to ask questions, and support for the patient to make choices) from their providers (6-item Health Care Climate Questionnaire (HCCQ); scored 0–7, with higher scores denoting greater autonomy support),24 and concordance of patient stent preference and type of stent received. Patients were categorized as having voiced a stent preference if they answered anything other than “I don’t care” or “I don’t know” in response to the question “After reviewing the risks and benefits of both types of stents, which type of stent did you want?” Patient socio-demographic, clinical and procedural characteristics were obtained from the study data collection form. Data were entered into REDCap and regularly audited for completeness. Although patients were consented and enrolled in the study prior to angiography, only those who ultimately underwent PCI were included in the analyses.

Analytic and Statistical Approaches

The target enrollment for this study was 600 patients. To evaluate the effect of the SDM intervention, we compared the above outcomes among patients in the no SDM tool, SDM tool alone, and SDM tool with coach groups. Unadjusted comparisons of continuous variables were made using one-way analysis of variance, and comparisons of categorical variables were made using chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. In addition, standardized differences were calculated for each pairwise comparison of groups. The standardized difference is the difference in group means divided by a pooled estimate of the within-group standard deviation, expressed as a percent. Being unitless, it can be used to compare the relative magnitude of between-group differences across variables with different scales, and unlike p-values does not depend on the sample size. Standardized differences >10% have been suggested as indicating imbalances between groups.25, 26 Adjusted comparisons were made using estimates from generalized linear models (normal distribution/identity link for mean differences, binomial or modified Poisson distribution with log link for rate ratios), adjusting for site and patient characteristics with standardized differences >10% (race, diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, prior CABG, prior PCI, admission status). Because patients’ correct recollection of the stent type received and of concordance with their stent preference was assessed after the procedure, comparisons of these two variables were further adjusted for stent type received to eliminate any potential confounding associated with stent received. Missing data were imputed using multiple imputation as implemented in the R package ‘mice’.27 The imputation model included all covariates and outcomes. Five imputed data sets were generated incorporating random perturbations in the imputed values to reflect uncertainty due to missingness. Models were fit on each of the five imputed data sets and results were pooled to obtain final effect estimates. Statistical significance was denoted by two-sided p-values <0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 3.3.1 (R Core Team).

Results

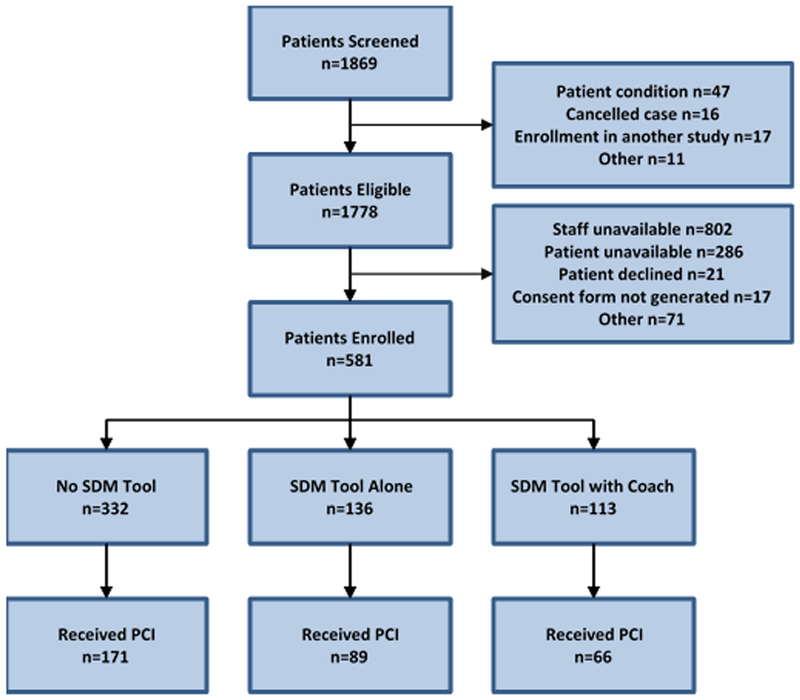

Patients’ experiences with stent selection were assessed in 332 patients in the no SDM tool group, 136 patients in the SDM tool alone group, and 113 patients in the SDM tool with coach group (Figure 1). Characteristics of patients enrolled in these three study phases were generally similar, although statistically significant differences were observed in site of enrollment, race, and history of peripheral arterial disease (Table 1).

Figure 1:

Patient Enrollment

Table 1.

Patient and Procedural Characteristics of Patients in the Pre-implementation and Post-implementation Phases

| Standardized Difference |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No SDM Tool n = 332 |

SDM Tool Alone n = 136 |

SDM Tool with Coach n = 113 |

P-Value | No SDM Tool vs SDM Tool Alone |

No SDM Tool vs. SDM Tool with Coach |

SDM Tool Alone vs. SDM Tool with Coach |

|

| Age - years | 66.1 ± 11.8 | 68.6 ± 11.6 | 67.6 ± 12.9 | 0.288 | 21.6 | 12.3 | 8.2 |

| Missing | 3 | ||||||

| Site | < 0.001 | 106.6 | 42.8 | 61.3 | |||

| MAHI | 187 (56.3%) | 131 (96.3%) | 86 (76.1%) | ||||

| Truman | 145 (43.7%) | 5 (3.7%) | 27 (23.9%) | ||||

| Sex | 0.974 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 0.3 | |||

| Male | 163 (63.7%) | 88 (64.7%) | 71 (64.5%) | ||||

| Female | 93 (36.3%) | 48 (35.3%) | 39 (35.5%) | ||||

| Missing | 76 | 3 | |||||

| Race | 0.030 | 26.0 | 14.0 | 14.7 | |||

| White/Caucasian | 248 (76.3%) | 115 (85.8%) | 91 (81.3%) | ||||

| Black/African-American | 77 (23.7%) | 18 (13.4%) | 21 (18.8%) | ||||

| Asian | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||||

| Missing | 7 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 5 (1.7%) | 3 (2.3%) | 2 (1.8%) | 0.911 | 4.0 | 0.4 | 3.6 |

| Missing | 43 | 5 | 1 | ||||

| Diabetes | 152 (45.9%) | 68 (52.3%) | 49 (43.4%) | 0.329 | 12.8 | 5.1 | 18.0 |

| Missing | 1 | 6 | |||||

| Hypertension | 264 (80.0%) | 106 (80.9%) | 92 (81.4%) | 0.938 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 1.3 |

| Missing | 2 | 5 | |||||

| Peripheral arterial disease | 29 (8.9%) | 20 (16.7%) | 22 (19.5%) | 0.004 | 23.5 | 30.8 | 7.3 |

| Missing | 5 | 16 | |||||

| Prior CABG | 53 (16.1%) | 28 (22.2%) | 20 (17.7%) | 0.305 | 15.7 | 4.4 | 11.3 |

| Missing | 2 | 10 | |||||

| Prior PCI | 137 (41.6%) | 66 (50.0%) | 50 (44.2%) | 0.262 | 16.8 | 5.3 | 11.5 |

| Missing | 3 | 4 | |||||

| Admission status | 0.299 | 16.1 | 6.2 | 9.9 | |||

| Inpatient | 118 (36.6%) | 57 (44.5%) | 44 (39.6%) | ||||

| Outpatient | 204 (63.4%) | 71 (55.5%) | 67 (60.4%) | ||||

| Missing | 10 | 8 | 2 | ||||

MAHI = Mid America Heart Institute; TMC = Truman Medical Center; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention

Continuous variables compared using one-way analysis of variance.

Categorical variables compared using chi-square or Fisher's exact test.

Stent knowledge score (0–6) increased from 2.3 ± 1.4 in patients in the no SDM tool group to 4.3 ± 1.5 in patients in the SDM tool with coach group (p<0.001). The proportion of patients who answered all 6 questions correctly increased from 1.8% in the no SDM tool group to 24.8% in the SDM tool with coach group (p<0.001). No differences were observed between patients in the no SDM tool group and those in the SDM tool alone group. In fully-adjusted analyses, patients in the SDM tool with coach group demonstrated a higher stent knowledge score [mean difference +1.8 (1.5, 2.1), p<0.001] and were more likely to answer all 6 questions correctly [RR 12.6 (5.3, 30.0), p<0.001].

Additionally, patients in the SDM tool with coach group reported higher perceived autonomy support from their nurse and physician than patients in the no SDM tool and SDM tool alone groups (Table 2). A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess for any interaction between receipt of PCI and knowledge transfer, process of SDM and participation in SDM. This analysis revealed that the positive impact of the SDM tool with decision coaching on perceived autonomy support from physician did not achieve statistical significance in patients who did not receive PCI, but remained statistically significant for all other variables in patients who did, and did not, receive PCI.

Table 2:

Adjusted analyses of knowledge transfer and shared decision making

| Effect Measure |

SDM Tool with Coach vs. No SDM Tool |

SDM Tool with Coach vs. SDM Tool Alone |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect (95% CI) | P-value | Effect (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Knowledge Transfer | |||||

| Total correct (out of 6) | Mean Difference | 1.8 (1.5, 2.1) | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.6, 2.3) | <0.001 |

| All questions correct | Risk Ratio | 12.6 (5.3, 30.0) | <0.001 | 8.8 (3.2, 24.5) | <0.001 |

| Process of SDM | |||||

| Discussed stent types with nurse | Risk Ratio | 3.6 (2.8, 4.7) | <0.001 | 9.9 (5.6, 17.6) | <0.001 |

| Perceived autonomy support from nurse (0-7) | Mean Difference | 0.7 (0.3, 1.1) | 0.002 | 2.2 (1.4, 3.1) | <0.001 |

| Discussed stent types with physician | Risk Ratio | 1.48 (1.25, 1.76) | <0.001 | 1.65 (1.28, 2.11) | <0.001 |

| Perceived autonomy support from physician (0-7) | Mean Difference | 0.7 (0.3, 1.1) | 0.002 | 2.5 (1.9, 3.1) | <0.001 |

| Participation in SDM | |||||

| Stated a stent preference | Risk Ratio | 2.00 (1.64, 2.44) | <0.001 | 3.61 (2.47, 5.29) | <0.001 |

| Shared/kept stent choice decision | Risk Ratio | 2.96 (1.90, 4.61) | <0.001 | 5.30 (2.56, 11.01) | <0.001 |

| Correctly recalled stent type received* | Risk Ratio | 1.37 (1.15, 1.64) | <0.001 | 1.26 (1.04, 1.54) | 0.021 |

| Stent preference concordant with actual*† | Risk Ratio | 0.97 (0.88, 1.07) | 0.53 | 0.92 (0.86, 1.00) | 0.041 |

For patients who received a stent;

For patients who voiced a stent preference

SDM = shared decision making

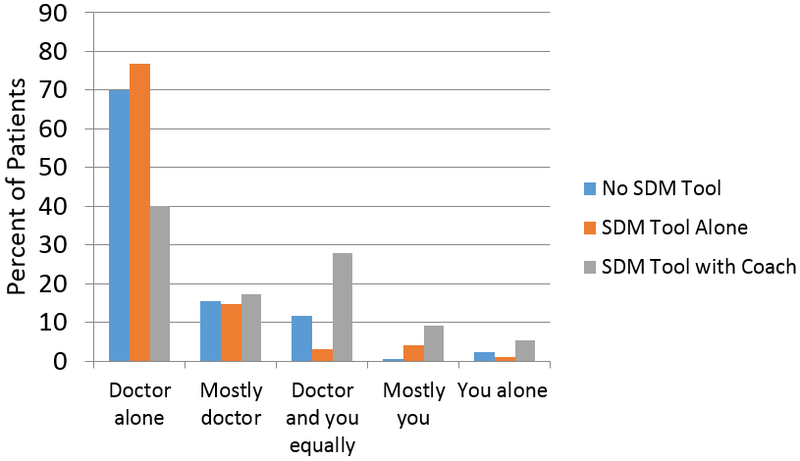

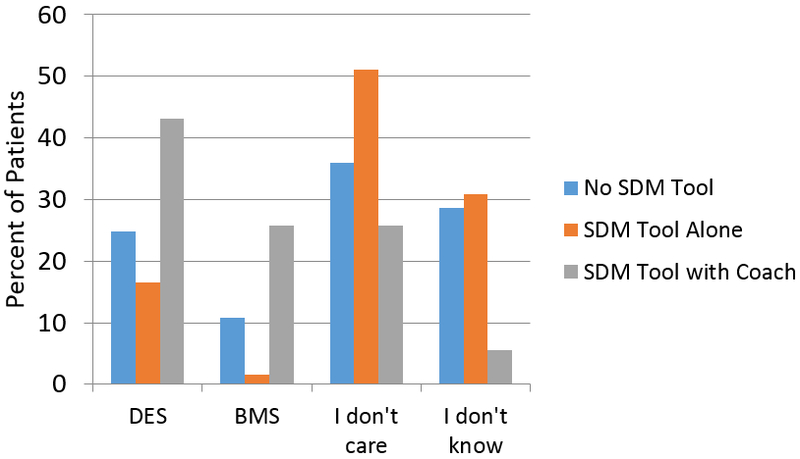

Patients in the SDM tool with coach group were more likely to participate in SDM regarding stent selection (60.0% vs 30.1%, p<0.001) and to state that they had a preference for the stent type they would like to receive (68.9% vs 35.6%, p<0.001), as compared with patients in the no SDM tool group (Figures 2A and 3). There was no difference in these parameters between patients in the no SDM tool group and those in the SDM tool alone group. In fully-adjusted analyses (Table 2), patients in the SDM tool with coach group were significantly more likely to participate in decision making regarding stent selection [OR 2.96 (1.90, 4.61), p<0.001] and to state a stent preference [OR 2.00 (1.64, 2.44), p<0.001].

Figure 2:

Patients’ participation in decision making regarding stent selection: Answer to the question, “Who chose the type of stent?”

Figure 3:

Patients’ stated stent preference: Answer to the question, “After reviewing the risks and benefits of both types of stents, which type of stent did you want?”

A greater proportion of patients preferred to receive DES as compared to BMS in all three phases of the study (24.8% vs. 10.8%, 16.5% vs. 1.5%, and 43.1% vs. 25.7% in the no SDM tool, SDM tool, and SDM tool with coach groups, respectively). In the entire study cohort, DES were used in 86.5% of cases. DES were used in 98% of patients who preferred DES (concordance 98%), in 79% of patients who did not have a stent preference, and in 50% of patients who preferred BMS (concordance 50%). No differences in the concordance of preference and treatment were observed across phases of the study (p-value for interaction = 0.77).

Discussion

We found that patients who received a SDM tool and decision coaching were significantly more likely to participate in SDM with respect to stent selection, to voice a stent preference, and to demonstrate knowledge about stents. However, when the tool was provided without coaching, there were no benefits observed over usual care. Prior studies have also demonstrated the benefits of decision coaching, both as an alternative to usual care, and as a supplement to patient decision aids.28 Taken together, these data clearly suggest that for the highest-quality SDM to occur, a personalized, evidence-based SDM tool needs to be supplemented with decisional coaching. Importantly, in this study, participation in SDM did not significantly impact physicians’ use of DES and BMS. A particularly striking finding is that while concordance between stent preference and stent received was nearly universal (98%) for patients who preferred DES, it was significantly lower (50%) for patients who preferred BMS. These findings suggest that even when patients participate in SDM and voice a preference for treatment, physicians often resort to their own preferences when making final treatment decisions.

While physician engagement in SDM is essential for the process to work as intended, prior research has suggested that several physician-level barriers exist to the incorporation of personalized risk models into clinical care.29 Such findings suggest that formal medical education regarding approaches to risk stratification, shared decision-making and cost effectiveness is needed, to promote evidence-based decision-making and improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care in the United States. To honor patients’ preferences and for patients to participate in treatment decisions, a transformation in the process of PCI and stent selection is needed. Importantly, one of the goals of healthcare is to improve quality while limiting costs. While reducing costs was not a primary goal of this intervention, aligning treatment with patients’ preference may, indirectly, lower the costs of PCI through the use of fewer DES, which are more expensive than BMS. In a prior analysis,12 we calculated that if the rate of DES use was cut in half (from 74% to 37%) in patients at low risk for restenosis, an estimated $205,000,000/year could be saved in the U.S. alone when adding the cost savings for stents and DAPT and subtracting the costs of repeat procedures. Interestingly, even if DES were entirely withheld from low-risk patients, the absolute increase in TVR would be <1%, with a savings of >$400,000,000/year. Accordingly, we postulate that a higher-quality SDM process might not only improve patients’ participation in SDM, but that if patients less likely to benefit from DES preferred and received BMS, SDM might result in significant health care savings, as observed in prior studies.30, 31

While the SDM tool with decision coaching had significant benefits on SDM in this study, we observed no benefit of the SDM tool to patients without decision coaching. In fact, perceived autonomy support was lowest in patients who received the SDM tool without decision coaching, raising the possibility that the provision of the SDM tool without coaching might reduce patients’ perceived autonomy support, perhaps because no nurse or physician is present while the patient reviews the material or to answer questions that arise from it. These data suggest that if the SDM tool is to be implemented in clinical practice, it is also important to invest in the infrastructure of decision coaching. This may prove to be a barrier in adoption, given that considerable effort will likely be needed to convince clinic and hospital administrators to provide the necessary resources for coaching. Alternatively, innovative approaches with telemedicine or web-based educational presentations could prepare patients for a more limited face-to-face discussion of the personalized information provided in the SDM tool. Ideally, this could be accomplished through payers providing a payment to offset the resources required to redesign care. An even bolder initiative might be to withhold reimbursement for elective PCI if SDM is not undertaken, as Medicare is doing for lung cancer screening with CT scans,32 left atrial appendage closure and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement.33 In any scenario, nurse and physician training in motivational interviewing communication principles should be considered to train providers on the importance of respecting patients’ preferences and methods to best engage patients in SDM. Regardless of the specific implementation strategy employed, significant investment may be necessary to bring about the changes in care desired by patients, patient advocates and professional societies.34

Future Research

As the results of this study appeared largely positive, novel implementation strategies might allow for this information to be shared with more patients. Furthermore, patients and providers voiced, in focus groups, that it would be preferable to provide information about stent options upstream of the procedure; however, we were not able to do so due to the rapidity with which patients referred for angiography are scheduled to undergo their procedures. Had we been able to provide the information sooner, patients would have had more time to reflect on the information and become even more engaged in SDM. On the other hand, it is possible that if the discussion was held too far in advance of the procedure, patients would forget the information over time and knowledge transfer would have been negatively impacted. Importantly, our finding that stent concordance was 98% for patients who preferred to receive DES and only 53% for patients who preferred to receive BMS suggests that physicians are prone to use DES and may be reluctant to change their decision-making when patient preferences differ from their own.29 This finding warrants further investigation, to better understand and overcome such physician biases, and to better engage physicians in SDM to deliver treatment that is preferred by patients.

Study Limitations

The lack of randomization with respect to the provision of the SDM tool and decision coaching was a limitation of this study. Because implementation of the tool altered the processes of care, it was decided to use a pre-post, as opposed to a randomized, study design. The concern in doing a randomized study was that, once participating, physicians would discuss stent options with patients randomized to both the intervention and control groups because they would become accustomed to doing so as part of the consent process. However, the fact that the improvements in SDM observed with the SDM tool and decision coaching reverted to baseline when decision coaching was withheld suggests that the observed improvements were not due to secular trends. Nevertheless, a cluster randomized trial design would be a desirable approach for future research in this area, albeit with the added complexity that more centers would be needed to complete such a study. In addition, a strategy of decision coaching alone was not tested in this study because without the SDM tool a personalized SDM discussion would be less consistent; therefore, it is unknown whether decision coaching in the absence of the SDM tool would have an impact on the outcomes measured in this study. A second limitation involves the use of ePRISM to construct the personalized SDM tool to be used in this study, as it may not be available at all hospitals and any impact of a non-personalized SDM tool cannot necessarily be extrapolated from the results of this study. A third limitation involves the estimation of TVR risk in the SDM tool without the availability of angiographic data. However, the inclusion of angiographic variables in the model only marginally improved its predictive power20 and, in the majority of cases in the U.S., PCI is performed “ad hoc,” making it impossible to include angiographic data in the estimation of TVR risk as the time that SDM could occur. Physicians were not provided with information regarding patients’ stent preference, if a preference was indeed voiced during the conversation with a Decision Coach. While the intent of this study was to educate patients and to engage them in SDM, the intent was not to dictate the type of stent used or for Decision Coaches to serve as a mouthpiece for patients. In addition, physicians were not surveyed for additional variables that impacted their stent selection; however, such surveys could introduce substantial bias, as “cognitive dissonance” could play a role in physicians’ justification of their medical decision-making. Finally, the information contained in the SDM tool was current at the time of the study, but can and should be updated as clinical knowledge evolves. For example, information regarding the cost of medications should be updated as costs change. Similarly, the DAPT duration recommendations following DES and BMS need to be updated as guidelines change.

Conclusions

A SDM tool for stent selection, in conjunction with decision coaching, is associated with significant improvements in the processes of, and patients’ engagement in, SDM and greater knowledge transfer. However, no benefits were observed when the SDM tool was provided to patients without decision coaching. No significant differences in the proportion of DES and BMS were observed in the study, and while patients who preferred to receive DES nearly always received DES, patients who preferred BMS often received DES, suggesting that physician-level barriers to SDM may exist.

Supplementary Material

What is Known.

Drug eluting stents (DES) reduce restenosis following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), but necessitate prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy

While the majority of patients undergoing PCI in the U.S. receive DES, only a minority report that stent options were discussed with them

What the Study Adds.

Use of a shared decision-making (SDM) tool for stent selection improved patient knowledge transfer and engagement in SDM only when accompanied by decision coaching

Concordance between stent desired and stent received was high (98%) when patients preferred DES, and considerably lower (50%) when patients preferred bare metal stents (BMS)

The SDM tool with or without decision coaching did not impact patient stent preference or concordance between stent desired and stent received

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jacque Sawyer, Robby Toops, Montague (Monty) Brown, Marilyn Mann, and John Carney along with 35 focus group participants for their time and assistance in completing this study.

Sources of Funding

Research reported in this publication was partially funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (CE-1304–6448). The statements in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. The researchers of this study are independent from PCORI.

Footnotes

Disclosures

JS reports significant equity interest in Health Outcomes Sciences. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D and Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics−−2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Holmes DR, O’Shaughnessy C, Caputo RP, Kereiakes DJ, Williams DO, Teirstein PS, Jaeger JL and Kuntz RE. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1315–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cox DA, Hermiller J, O’Shaughnessy C, Mann JT, Turco M, Caputo R, Bergin P, Greenberg J, Popma JJ and Russell ME. A polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:221–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonaa KH, Mannsverk J, Wiseth R, Aaberge L, Myreng Y, Nygard O, Nilsen DW, Klow NE, Uchto M, Trovik T, Bendz B, Stavnes S, Bjornerheim R, Larsen AI, Slette M, Steigen T, Jakobsen OJ, Bleie O, Fossum E, Hanssen TA, Dahl-Eriksen O, Njolstad I, Rasmussen K, Wilsgaard T and Nordrehaug JE. Drug-Eluting or Bare-Metal Stents for Coronary Artery Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1242–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhatriwalla AK, Venkitachalam L, Kennedy KF, Stolker JM, Jones PG, Cohen DJ and Spertus JA. Relationship between stent type and quality of life after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2015;170:796–804 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone GW, Parise H, Witzenbichler B, Kirtane A, Guagliumi G, Peruga JZ, Brodie BR, Dudek D, Mockel M, Lansky AJ and Mehran R. Selection criteria for drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents and the impact of routine angiographic follow-up: 2-year insights from the HORIZONS-AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;56:1597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tu JV, Bowen J, Chiu M, Ko DT, Austin PC, He Y, Hopkins R, Tarride JE, Blackhouse G, Lazzam C, Cohen EA and Goeree R. Effectiveness and safety of drug-eluting stents in Ontario. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grines CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE Jr., Gardner TJ, Lockhart PB, Moliterno DJ, O’Gara P and Whitlow P. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, American College of Surgeons, and American Dental Association, with representation from the American College of Physicians. Circulation. 2007;115:813–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt DL, Fox KAA, Hacke W, Berger PB, Black HR, Boden WE, Cacoub P, Cohen EA, Creager MA, Easton JD, Flather MD, Haffner SM, Hamm CW, Hankey GJ, Johnston SC, Mak K-H, Mas J-L, Montalescot G, Pearson TA, Steg PG, Steinhubl SR, Weber MA, Brennan DM, Fabry-Ribaudo L, Booth J and Topol EJ. Clopidogrel and Aspirin versus Aspirin Alone for the Prevention of Atherothrombotic Events. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354:1706–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amin AP, Bachuwar A, Reid KJ, Chhatriwalla AK, Salisbury AC, Yeh RW, Kosiborod M, Wang TY, Alexander KP, Cohen DJ, Spertus JA and Bach RG. Nuisance Bleeding With Prolonged Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Acute Myocardial Infarction and its Impact on Health Status. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;61:2130–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qintar M, Chhatriwalla AK, Arnold SV, Tang F, Buchanan DM, Shafiq A, Pokharel Y, deBronkart D, Ashraf JM and Spertus JA. Beyond restenosis: Patients’ preference for drug eluting or bare metal stents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;90:357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amin AP, Spertus JA, Cohen DJ, Chhatriwalla A, Kennedy KF, Vilain K, Salisbury AC, Venkitachalam L, Lai SM, Mauri L, Normand SL, Rumsfeld JS, Messenger JC and Yeh RW. Use of drug-eluting stents as a function of predicted benefit: clinical and economic implications of current practice. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1145–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krone RJ, Shaw RE, Klein LW, Blankenship JC and Weintraub WS. Ad hoc percutaneous coronary interventions in patients with stable coronary artery disease--a study of prevalence, safety, and variation in use from the American College of Cardiology National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC-NCDR). Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2006;68:696–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, Tuzcu EM, Webb JG, Fontana GP, Makkar RR, Brown DL, Block PC, Guyton RA, Pichard AD, Bavaria JE, Herrmann HC, Douglas PS, Petersen JL, Akin JJ, Anderson WN, Wang D and Pocock S. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Committee on Quality Health Care in America IoM. Crossing the quality chasm : a new health system for the 21st century: Washington, D.C. : National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garavalia L, Garavalia B, Spertus JA and Decker C. Exploring patients’ reasons for discontinuance of heart medications. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;24:371–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, Volk R, Edwards A, Coulter A, Thomson R, Barratt A, Barry M, Bernstein S, Butow P, Clarke A, Entwistle V, Feldman-Stewart D, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Moumjid N, Mulley A, Ruland C, Sepucha K, Sykes A, Whelan T and International Patient Decision Aids Standards C. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spertus JA, Gialde E, Chhatriwalla AK, Gosch K, Jones PG, McCartan J, McNulty EJ, Guerrero M, Kugelmass AD, Bach RG, Curtis J, Bethea C, Shelton M, Leonard B, Ting HH and Decker C. Testing an Evidence-Based, Individualized Informed Consent Form to Improve Patients’ Experiences with PCI. Circulation. 2011;124:2368. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spertus JA, Bach R, Bethea C, Chhatriwalla A, Curtis JP, Gialde E, Guerrero M, Gosch K, Jones PG, Kugelmass A, Leonard BM, McNulty EJ, Shelton M, Ting HH and Decker C. Improving the process of informed consent for percutaneous coronary intervention: patient outcomes from the Patient Risk Information Services Manager (ePRISM) study. Am Heart J. 2015;169:234–241 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh RW, Normand SL, Wolf RE, Jones PG, Ho KK, Cohen DJ, Cutlip DE, Mauri L, Kugelmass AD, Amin AP and Spertus JA. Predicting the restenosis benefit of drug-eluting versus bare metal stents in percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2011;124:1557–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Legare F, Ratte S, Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Gravel K, Graham ID and Turcotte S. Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD006732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller WR and Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deber RB, Kraetschmer N and Irvine J. What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1414–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams GC, McGregor HA, Sharp D, Levesque C, Kouides RW, Ryan RM and Deci EL. Testing a self-determination theory intervention for motivating tobacco cessation: supporting autonomy and competence in a clinical trial. Health Psychol. 2006;25:91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin PC. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flury B and Riedwyl H. Standard distance in univariate and multivariate analysis. The American Statistician. 1986;40:249–251. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Buuren S and Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. MICE: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Bennett C, Murray MA, Mullan S and Legare F. Decision coaching to prepare patients for making health decisions: a systematic review of decision coaching in trials of patient decision AIDS. Med Decis Making. 2012;32:E22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Decker C, Garavalia L, Garavalia B, Gialde E, Yeh RW, Spertus J and Chhatriwalla AK. Understanding physician-level barriers to the use of individualized risk estimates in percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2016;178:190–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barry MJ and Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oshima Lee E and Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dobler CC, Midthun DE and Montori VM. Quality of Shared Decision Making in Lung Cancer Screening: The Right Process, With the Right Partners, at the Right Time and Place. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1612–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merchant FM, Dickert NW Jr. and Howard DH. Mandatory Shared Decision Making by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for Cardiovascular Procedures and Other Tests. JAMA. 2018;320:641–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P and Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.