Abstract

This in-depth review of sex differences in advanced heart failure therapy summarizes the existing literature on implantable cardioverter defibrillators, biventricular pacemakers, mechanical circulatory support and transplantation with a focus on utilization, efficacy/clinical effectiveness, adverse events and controversies. One will learn about the controversies regarding efficacy/clinical effectiveness of implantable cardioverter defibrillators and understand why these devices should be implanted in women even if there are sex differences in appropriate shocks. One will also learn about the sex differences with biventricular pacemakers with respect to ventricular remodeling and reduction in heart failure hospitalizations/mortality as well as possible mechanisms. One will also learn about sex differences in heart transplantation and waitlist survival. Despite similar survival for women and men with left ventricular assist devices there are sex differences in adverse events. These devices do successfully bridge women and men to transplant yet women are less likely than men to have a left ventricular assist at time of listing and time of transplantation. Finally one will learn about the concerns regarding poor outcome for men who receive female donor hearts and discover this may not be due to sex but rather size. More research is needed to better understand sex differences and further improve advanced heart failure therapy for both women and men.

Keywords: sex, congestive heart failure, transplantation, ventricular assist device, pacemaker

Over 75,000 patients in the United States died from advanced heart failure in 2015 and 55% were women.1 Advanced heart failure refers to patients who have severe heart failure despite guideline directed medical therapy and compliance with medication, fluid restriction and diet. In the European Society of Cardiology guidelines these patients are defined as being in New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Class III-IV with significant fluid retention or low cardiac output, poor functional capacity, two or more heart failure hospitalizations per year, and objective evidence of advanced heart disease such as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <30%, pseudonormal or restrictive mitral inflow pattern, elevated natriuretic peptides, or volume overload (pulmonary capillary wedge pressure >16 mmHg or right atrial pressure >12 mmHg). Other important indicators of advanced heart failure include hyponatremia (serum sodium <133 mEq/L), hypotension (systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg) limiting titration of medications, rise in serum BUN and creatinine, frequent implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) shocks, cardiac cachexia, and shortness of breath or fatigue with minimal activity.2 This manuscript reviews sex differences in utilization, efficacy/clinical effectiveness, adverse events, and controversies of advanced heart failure therapies beyond guideline oral medical management and will include ICDs, biventricular pacemakers, mechanical circulatory support, and heart transplantation.

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator

Background:

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) improve survival by preventing sudden death from ventricular arrhythmias in high risk heart failure patients. Primary prevention with an ICD is recommended for symptomatic heart failure patients who, despite guideline driven medical therapy, have NYHA functional class II or III symptoms with an ischemic cardiomyopathy greater than 40 days after myocardial infarction or non-ischemic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular ejection fraction < 35% (Class I indication). It is also recommended for patients with more advanced heart failure who meet criteria for a biventricular pacemaker (NYHA Functional Class III-IV) or are candidates for heart transplantation and/or mechanical circulatory support.2 Although landmark trials have shown that ICDs reduce sudden death in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction, these studies were not designed to prospectively analyze the female cohort and women were under-represented.3

Utilization:

Prior studies, including registries and administrative data, have shown women less likely than men to have an ICD implanted even after adjusting for age and co-morbidities. These studies included all patients eligible for an ICD, but were not limited to patients with advanced heart failure.4–9 The reasons for sex differences in ICD utilization remain largely unknown but in one large analysis that included 21,059 patients admitted with heart failure, women eligible for an ICD with an ejection fraction ≤35% were less likely than men to receive ICD counseling (19.3% women vs 24.6% men, P<0.001, adjusted OR 0.84 [95% CI 0.78–0.91]). Among the 4,755 who received counseling, the majority (63%) underwent placement of an ICD or had one planned after discharge with no difference in utilization between women (63.1%) and men (62.3%).5

Efficacy/Effectiveness:

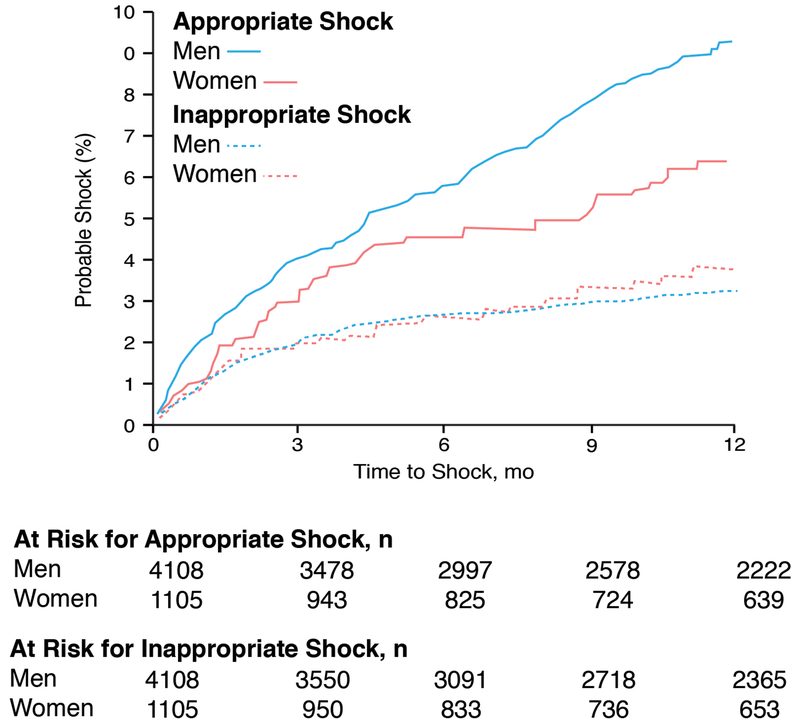

The efficacy of an ICD in women with heart failure is controversial. Several device trials show similar survival between women and men with no sex interaction identified.10–12 However, these studies were not powered to study sex differences. In one meta-analysis (934 women, 3,810 men) utilizing five primary prevention ICD trials (DEFINITE, SCD-HeFT, DINAMIT, MUSTT, and MADIT-II) that excluded patients with biventricular pacemakers, there was no survival benefit among the women randomized to ICD (HR 1.01 [95% CI, 0.76-1.33] P=0.95) yet there was a 22% reduction in mortality among men (HR 0.78 [95% CI, 0.70-0.87] P<0.001).13 In another meta-analysis by Santangeli and colleagues with 7,229 patients (22% women), women had similar survival compared to men, but were less likely to have an appropriate ICD shock for rapid sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. Because an ICD only prevents sudden death, the similar all-cause mortality between women and men in this meta-analysis was not entirely driven by sudden death (mortality ICD survival benefit in women: HR 0.78 [95% CI, 0.57-1.05] P=0.1).14 Sex differences in appropriate ICD shocks were also noted in a large Medicare population for primary and secondary prevention from sudden death 4 and international studies.15–17 In the EU-CERT-ICD project that included 957 women and 4,076 men implanted with an ICD for primary prevention in 11 European countries, women had fewer appropriate ICD shocks (8% vs 14%) and better survival than men even after adjusting for age, presence of ischemic cardiomyopathy and a biventricular pacemaker (adjusted HR 0.65 [95% CI 0.53-0.790], P <0.0001).15 In another international study with an ICD for primary and secondary prevention that included 216 women and 935 men, women had fewer appropriate ICD shocks for sustained ventricular arrhythmias and less appropriate antitachycardia pacing therapy than men (22.7% vs 35.4%, P=0.0003).16 Finally, in the Ontario ICD Database, a prospective population-based registry that included 1,105 women and 4,108 men with an ICD for primary and secondary prevention, women were 31% less likely than men to receive an appropriate ICD shock for ventricular arrhythmias (adjusted HR 0.69 [95% CI, 0.51-0.93, P=0.015]) and 27% less likely to receive appropriate antitachycardia pacing (adjusted HR 0.73 [95% CI, 0.59-0.90, P=0.003]) (Figure 1).17 In summary, there remains some controversy regarding the efficacy of an ICD in women with most heart failure studies showing no sex difference in all-cause mortality but a lower likelihood of appropriate ICD shocks in women compared to men.

Figure 1.

Time to first appropriate or inappropriate Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) shock for women and men implanted in Ontario, Canada for primary or secondary prevention between February 2007-July 2010. Adapted from MacFadden et al. with permission17

Adverse Events/Complications:

Complications related to ICD implantation include infection, bleeding, cardiovascular perforation, and inappropriate ICD shocks. Two large registries have reported sex differences in adverse events. In the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, a national database that includes all Medicare patients implanted with an ICD for primary prevention, women (n=9,750) had a higher occurrence than men (n=29,162) of 30 day device-related pneumothorax requiring chest tube (0.89% vs 0.47%, P<0.001), hematomas requiring transfusion or evacuation (0.37% vs 0.25%, P=0.047), cardiac tamponade (1.39% vs 0.45%, P <0.001), mechanical complications requiring revisions within 90 days of ICD implantation (2.40% vs 1.71%, P<0.001), and 30 day mortality (1.45% vs 1.05%, P=0.002). Even after adjusting for possible confounding variables, there remained sex differences in 30 and 90 day adverse events (women: adjusted odds ratio 1.39 [95% CI 1.26–1.53], P <0.001) including hospital readmission for heart failure within 6 months of ICD implantation (women: adjusted OR 1.32 [95% CI 1.23–1.42, P <0.001]).18 In the Ontario ICD Database that included 1,106 women and 4,107 men implanted with an ICD for primary or secondary prevention, women were 1.9 fold more likely than men to have a major complication and 1.6 fold more likely than men to have a minor complication within 1 year of implantation of an ICD after multivariable adjustment. The risk of lead dislodgement was among the most clinically significant adverse events occurring in women more than men. There was no sex difference in inappropriate shock (Figure 1) or mortality.17

Discussion:

Why do women have fewer appropriate shocks and more adverse events after implantation of an ICD? Many heart failure studies have shown that women are less likely to have ventricular arrhythmias than men which would account for the sex differences in appropriate ICD shocks.17–20 In fact, in one analysis that included 5 cohorts without an ICD, women (n=1,697) with heart failure were less likely to die than men (n=6,640) and mode of death was less likely due to sudden death (3.4%/year vs 4.8%/year).20 In fact, for any Seattle Heart Failure Score in that analysis women had a 24% lower risk of sudden death (P=0.02) and a 54% higher risk of pump failure (P=0.0004) when compared to men.20 Could sex differences in mortality reflect sex differences in underlying cause of heart disease or other factors such as hormones? Women are more likely than men to have a cardiomyopathy due to hypertension and less likely due to coronary artery disease3 which may affect total myocardial scar burden. However, in MADIT II, a randomized ICD study for patients with an ischemic cardiomyopathy including 192 women and 1,040 men, men still had more appropriate ICD therapy than women (50 vs 37 ICD therapies per 1,000 patient-months) although not statistically significant.10 If the study was appropriately powered to study sex differences and the myocardial scar burden was the same, would women be as likely as men to have ventricular arrhythmias? The answer is unknown, but sex hormones have been shown to affect regulation of myocardial ion channels resulting in fewer potassium channel subunits in female ventricles, weaker repolarization currents, longer action potentials durations, and longer QT intervals in women compared to men, which may account for a higher risk of Torsades de pointes and a lower risk of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation.21, 22 There also is evidence of sex-dependent alterations of calcium cycling from patients with heart failure due to cardiac hypertrophy with a lower leak of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium in ventricular myocytes isolated from women compared to men. Sarcoplasmic reticulum leak of calcium triggers delayed afterdepolarizations and may account for a lower occurrence of spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias in women with heart failure compared to men.23 Regardless of sex differences in risk of ventricular arrhythmias, it is important to emphasize that all appropriate ICD therapies prevent sudden death. The point estimate for ICD survival benefit in the meta-analysis by Santangeli and colleagues was HR 0.78 in women and HR 0.67 for men. Women benefited from appropriate ICD therapy in that study and the wide confidence intervals were due to small sample size.14 Therefore, ICDs prevent sudden death and better utilization will depend on identifying sex-specific risk factors for ventricular arrhythmias.

Why are there sex differences in adverse events after implantation of an ICD? The reason remains unknown. Hypotheses include difficulties with vascular access due to smaller vessels and body size in women compared to men, more bleeding in women compared to men during invasive procedures, and sex differences in severity of illness of heart failure at time of device implantation. All of these hypothesis are reasonable but none have been proven.17, 18

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy

Background:

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with a biventricular pacemaker has been shown in many randomized clinical trials to improve exercise capacity, quality of life, ejection fraction, ventricular remodeling and survival. Among patients with advanced heart failure (NYHA Functional Class III-IV), a CRT device should be implanted for patients with LVEF < 35%, sinus rhythm, left bundle branch block (LBBB) and QRS > 150 ms (Class I indication) because these patients have the greatest benefit. It may also be useful in heart failure patients with non-LBBB, QRS 120-140 ms, and sinus rhythm or atrial fibrillation with significant pacemaker dependency. However, it is not recommended for patients who have life expectancy less than one year (Class III indication). These ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines are based on landmark trials2 with the majority of studies showing that women benefit from CRT, possibly more than men.

Utilization:

Recent national and international studies have shown an underutilization of CRT in women compared to men with sex disparity in the United States increasing over time.24–29 Most of the CRT implantations in the United States are with an ICD (CRT-D) and women are less likely to have CRT-D than men if they are over 80 years old, have atrial fibrillation, or have chronic kidney disease.24 What remains unknown is whether the sex disparity persists among patients with advanced heart failure because ACC/AHA guidelines for CRT are not limited to this cohort.2 In one large analysis using the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Registry for patients with CRT-D between January 2006-June 2008, there were few patients with severe heart failure symptoms (8% NYHA Functional Class IV) and only 50% on guideline directed therapy with NYHA Functional Class III-IV symptoms, LVEF <35%, and QRS >120 ms.28

Efficacy/Effectiveness:

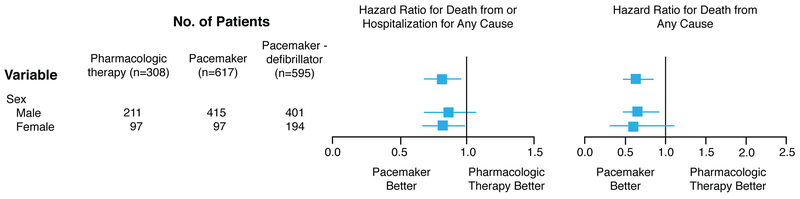

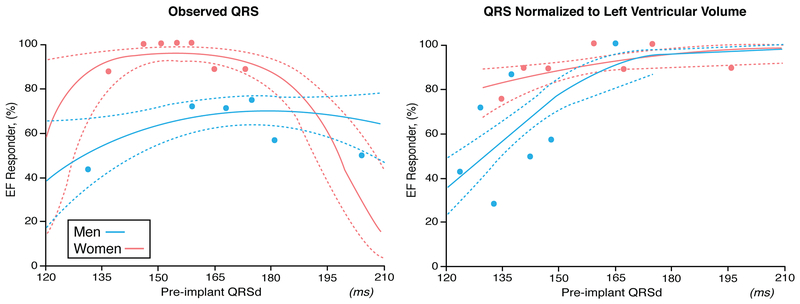

There are many studies assessing sex differences in efficacy/effectiveness for CRT in heart failure patients ranging from mortality benefits to improvements in quality of life, ventricular remodeling, and heart failure hospitalizations. Because an ICD can affect mortality (but less likely the other outcomes), the usage of CRT-D should be distinguished from CRT without an ICD (CRT-P) when evaluating this outcome. Among patients with advanced heart failure, two randomized clinical trials compared CRT to medical therapy and demonstrated benefits in women. In the Cardiac Resynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) trial involving 215 women and 597 men with LVEF < 35% and QRS > 120 ms, CRT-P reduced mortality and time to cardiovascular hospitalizations in women (HR 0.64 [95% CI 0.42–0.97]) and men (HR 0.62 [95% CI 0.49–0.79]) alike. In this trial the greatest benefit for CRT-P was among those with a QRS >160 ms.30 In the Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (COMPANION) trial, CRT-P when compared to pharmacologic treatment reduced the primary combined endpoint of death or hospitalization for women (Figure 2). The presence of a defibrillator (CRT-D) significantly improved survival in men but not women when CRT-D was compared to pharmacologic therapy (Figure 2), but the point estimate was the same, suggesting lack of significance related to smaller number of women than men in the trial. 31 In the Management of Atrial Fibrillation Suppression in AF-HF Comorbidity Therapy (MASCOT) study, an international multi-center study with 393 patients (82 women) with advanced heart failure (NYHA Functional Class III-IV), LVEF < 35% and QRS >130 ms, there was no sex difference for increased LVEF >5% with CRT, but women compared to men had a greater reduction in left ventricular end-diastolic dimension (−8.27 +/−11.14% vs −1.14 +/− 22.05%, P=0.02) and improvement in quality of life measured with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (−21.19 +/− 26.56 vs −16.20+/− 22.19, P<0.0001). After adjusting for cardiovascular history, women compared to men also had lower all-cause mortality (P = 0.008) despite a lower frequency of ICD usage (CRT-D 35% women, 62% men), lower cardiac mortality (P = 0.04), and fewer hospitalizations due to worsening heart failure (P = 0.045). This study included patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, CRT-P and CRT-D, and mainly patients with wide QRS (women QRS ms 168.25 +/− 36.06 vs men QRS ms 162.24 +/− 25.98).32 In another large study with advanced heart failure patients (90% NYHA Functional Class III-IV) limited to nonischemic cardiomyopathy and LBBB, women (n=105) had greater cardiac reverse remodeling benefits with CRT than men (n=107) even when QRS 120–149 ms (LV end-systolic dimension reduced by 0.85 +/− 1.2 cm in women vs 0.34 +/− 0.91 cm in men, P<0.01; LVEF increased by 12 +/− 13% in women vs 0.89 +/− 9.0 in % men , P=0.001).33 In fact, women have been shown to have a higher probability of CRT response than men with LBBB when QRS duration is < 150 ms (Figure 3).33–36 In summary, the majority of heart failure studies supports a greater CRT benefit in women compared to men.

Figure 2.

Sex differences in outcome comparing cardiac resynchronization therapy without an implantable defibrillator (CRT-P) and with an implantable defibrillator (CRT-D) to pharmacologic therapy in the Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (COMPANION) Study. Adapted from Bristow et al. with permission31

Figure 3.

Sex specific response to cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with left bundle branch block (LBBB ) based on QRS duration (left) and QRS duration normalized to left ventricular volume (right). Cohort includes 130 patients at the Cleveland Clinic with a median follow-up of 2 years. Response is defined as an increase in ejection fraction (EF) after CRT. Adapted from Varma et al. with permission36

Adverse Events/Complications:

There are sex differences in adverse events with the data mostly limited to CRT-D. In the MADIT-CRT trial, heart failure patients were randomized 3:2 ratio to CRT-D or ICD and major procedure related adverse events were 2.5 times more likely to occur in women with CRT-D compared to men with CRT-D. These adverse events were predominately due to sex differences in the frequency of pneumothorax/hemothorax (women 4.4% vs men 0.9%) and infection requiring reoperation (women 2.5% vs men 0.6%). In this analysis predictors of major adverse events in women were smaller body mass index (P=0.050), elevated serum blood urea nitrogen level (P=0.038), and elevated serum creatinine (P=0.039).37 In a smaller study that evaluated 123 consecutive patients (32 women, 91 men) requiring CRT‐D while on anticoagulation therapy versus usage of anticoagulation therapy after device implantation, hematomas were more common in women 13% compared to men 7%.38 Finally, in a large retrospective analysis using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database of CRT implantations between 2002–2010, in-hospital mortality was lower in women compared to men (0.71% vs 0.93%) with no significant sex difference in length of stay after implantation of a CRT device.27

Discussion:

The reason women benefit more than men from CRT remains unclear and may have to do with women more likely than men to have a “true LBBB” at lower QRS durations because women have a shorter QRS duration than men in the absence of any conduction disease22 or sex differences in heart size with women tending to have smaller hearts than men affecting distance of conduction travel across the myocardium.36 Sex differences in type of heart disease may also play a role, but most studies have adjusted for type of heart disease and still show sex differences in CRT benefit.

Mechanical circulatory support

Background:

Mechanical circulatory support can bridge heart failure patients to transplant and extend life for those who have failed medical management. Since 2006, over 20,000 devices have been implanted and about 40% were implanted as destination therapy. Almost all of these durable mechanical circulatory support devices are left ventricular assist devices (93%) with the majority implanted in men (79%).39 Ventricular assist devices (VADs) have evolved from large pulsatile devices that required the recipient to have a body surface area > 1.5 m2 to small (<1 lb) continuous flow devices with axial or centrifugal flow that are more durable and can be implanted in petite women.40

Utilization:

Utilization of mechanical circulatory support has increased over time for both women and men with advanced heart failure because the continuous flow VADs are smaller and better than the first generation pulsatile VADs. For instance, between 2006-2009 the total number of patients with mechanical circulatory support included 445 women and 1,711 men compared to usage of devices between 2014-2017 with 2,193 women and 7,958 men. The majority of devices for mechanical circulatory support were VADs (>95%) with the ratio of women to men similar over time (21% women and 79% men in 2006-2009 vs 22% women and 78% men in 2014-2017).39 The reason for these sex differences in utilization remains unknown.

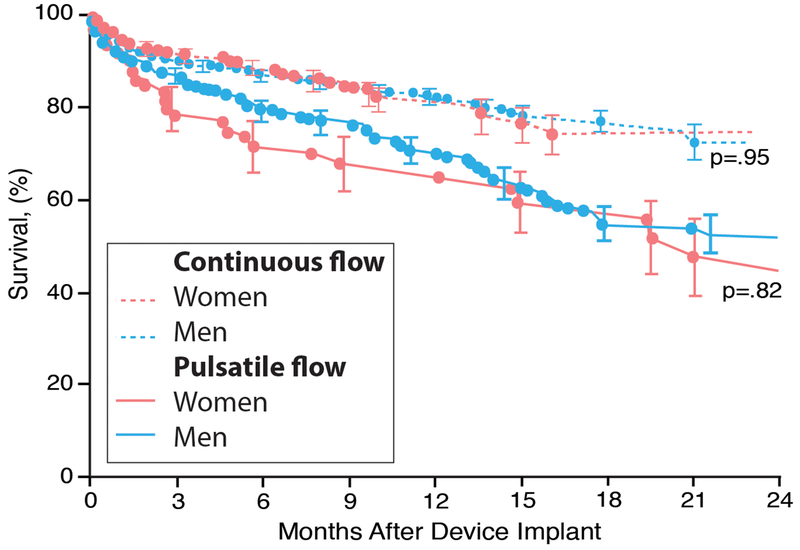

Efficacy/Effectiveness:

Survival has improved for both women and men implanted with ventricular assist devices, and there are no sex differences in mortality (Figure 4).41–45 Continuous flow devices are superior to pulsatile devices with 1, 2, and 4 yr survival 82%, 70%, and 50% compared with 64%, 40%, and 28% for pulsatile devices. Patients with left ventricular assist devices have a better survival than those with bi-ventricular assist devices and patients bridged with device to transplant have a better survival than those implanted with a ventricular assist device as destination therapy.39 Mortality for patients awaiting heart transplantation with a ventricular assist device has declined significantly since 2004 and is now slightly better than that of patients not having mechanical circulatory support.46

Figure 4.

Sex-specific survival with pulsatile and continuous flow left ventricular assist devices based on the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) registry from June 23, 2006, and March 31, 2010. Adapted from Hsich et al. with permission42

Adverse Events/Complications:

Complications with mechanical circulatory support include device failure, bleeding, infection, and neurologic events. Sex-specific data regarding these complications are limited, retrospective, and usually based on the findings of a single center. One of the largest sex-specific studies involving 89 institutions utilized the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) database, a national registry for patients implanted with a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved mechanical circulatory device, and found no sex differences in time to first device malfunction, bleeding or infection among patients implanted with a left ventricular assist device between June 23, 2006 and March 31, 2010. However, there was a higher risk of neurologic events in women compared to men.42 A more recent INTERMACS update with 7,112 patients (22% female) implanted with a left ventricular assist device between May 1, 2012 to March 31, 2015, also found that occurrence of stroke was significantly higher for women than men (incidence rate ratio 1.53 [95% CI 1.32 −1.77] P<0.001). Among women with a stroke, 54% were hemorrhagic and 46% were ischemic. In a multivariable analysis of patients with a stroke within 2 weeks of left ventricular assist device implantation (16% of cohort), female sex had a HR 1.52 [95% CI 1.0021.013] P<0.0001.47 However, in a smaller multi-center study called the Mechanical Circulatory Support Research Network (MCSRN) involving 734 patients (20% women) implanted with a left ventricular assist device at 3 institutions between May 2004 and September 2014 there was no sex difference in time-related device complications including stroke.48 Why was the outcome different? Information on baseline characteristics, management of anticoagulation therapy and type of device in INTERMACS42, 47 and MCSRN48 was limited making it hard to determine if differences were due to sample size or other factors. Type of mechanical circulatory support utilized was also not mentioned and very relevant because the risk of stroke varies significantly with the type of continuous ventricular assist device utilized.

HeartMate II was an axial continuous-flow left ventricular assist device approved by the FDA for bridge to transplant on 4/21/08 and for destination therapy on 1/20/10. The initial FDA approval was based on a multi-center HeartMate II Study that included 44 women awaiting transplantation. Although the study was under-powered to study sex differences, there was concern regarding a higher occurrence of stroke in women compared to men (18% vs. 6%).49, 50 In a larger multi-center HeartMate II study with 104 women and 361 men that included the original cohort bridged to transplantation, there remained a higher risk of hemorrhagic stroke (0.10 vs 0.04 events/patient-year, P=0.006) despite no sex differences in ischemic stroke or average systolic blood pressure, mean INR, partial thromboplastin time, or platelet count.41 When the HeartMate II bridged to transplant cohort was combined with the destination therapy cohort, women (n=224) were at higher risk of both hemorrhagic stroke (HR 1.92) and ischemic stroke (HR 1.84). The risk of hemorrhagic stroke was highest among women less than 65 years old whereas for ischemic stroke the risk was higher among women older than 65 years old.51 Two smaller single center studies also reported a higher risk of stroke in women (HR >4) implanted with HeartMate II compared to men despite institutional difference in dose of aspirin (81 mg vs 325 mg daily).43, 44 The risk of stroke was slightly lower for all patients with longer time in therapeutic INR range.44

HeartWare and HeartMate 3 are contemporary centrifugal continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices with limited sex specific data. HeartWare was approved by the FDA for bridge to transplant on 12/4/12 and destination therapy on 9/27/17. In the ENDURANCE trial, when HeartWare was compared to HeartMate 2, there was a higher risk of stroke among all patients (women and men combined) with HeartWare (29.7% vs. 12.1%, P<0.001)52 that was significantly reduced with blood pressure control.53 Sex-specific data was not provided in that analysis. However, in the multi-center HeartWare Ventricular Assist Device for the Treatment of Advanced Heart Failure (ADVANCE) Bridge to Transplant and continued access protocol trials, there were 96 women and 236 men with no sex difference in risk of stroke or transient ischemic attacks (ischemic stroke 3% women vs 11% men, P=0.86; hemorrhagic stroke 5% women vs 17% men, P=0.97).45 HeartMate 3 received FDA approval for bridge to transplant on 8/3/17. In the Multicenter Study of MagLev Technology in Patients Undergoing Mechanical Circulatory Support Therapy with HeartMate 3 (MOMENTUM 3), HeartMate 3 was superior to HeartMate II in the primary endpoint of survival free of disabling stroke or reoperation to replace or remove the device in a cohort of patients with advanced heart failure (bridged to transplant and with destination therapy). There was no sex difference in stroke risk, but the HeartMate 3 cohort consisted of only 31 women.54, 55 Interestingly, the risk of stroke after 2 years of follow-up was much lower in the HeartMate 3 cohort than the HeartMate II cohort (HR 0.47 [95% CI 0.27–0.84], P=0.02).56

Discussion:

Why would type of continuous flow device affect rate of stroke and should women avoid implantation of continuous flow devices given concerns of higher risk of neurologic events? Differences in stroke risk may be related to axial vs centrifugal continuous flow, location for implantation (intra-abdominal vs intrapericardial), and anticoagulation management. The different continuous flows (axial vs centrifugal) and algorithms in the newer devices for pump speed change to enhance washing of the pump may affect risk of thrombosis and risk of embolic event. HeartMate II required an intra-abdominal pocket and took longer to implant than HeartWare and HeartMate 3 which are implanted in the pericardial space. Longer time in the operating room could lead to thrombus formation accounting for the higher risk of device thrombosis in HeartMate II when compared to HeartWare52 or HeartMate 3.55 Finally, the ideal therapeutic INR to prevent thrombosis for each device remains unknown and could also account for differences in stroke risk. Despite potential risk of neurologic events, the incidence of stroke remains low for women and men (estimated incidence rate of stroke in women: 0.0169 strokes per patient-year and in men 0.111 per patient-year).47 Therefore, the mortality benefits outweigh the risk of neurologic events and VADs should be implanted in eligible patients who have failed medical therapy.

Heart Transplantation

Background:

Heart transplantation provides the best outcome for eligible advanced heart failure patients with 1-year survival of 91%,57 median survival 11–12 years,58 and improved quality of life.59, 60 The number of new candidates added to the national heart transplant waitlist every year has increased from 2,240 in 2005 to 3,521 in 2016 with no significant difference in the percent of women (22%) and men (78%) awaiting transplantation. 46, 57 As of August 15, 2018 there were 1,038 women and 2,913 men awaiting heart transplantation in the United States.57 Although transplantation provides these advanced heart failure patients the best possible outcome, the number of patients on the waitlist still exceeds the number of available donor hearts, so many die waiting for an organ.61–63 Are there any sex differences in outcome and if so why?

Pre-transplantation:

There are many known sex differences in baseline characteristics and survival among patients listed for heart transplantation. At time of listing, women are more likely than men to be younger, non-Caucasians, and have lower body mass index, dilated cardiomyopathy, and Medicaid insurance but less likely than men to have an ischemic cardiomyopathy, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, tobacco usage, or an ICD.64, 65 Among those listed for urgent transplantation (UNOS Status 1), women are less likely than men to be on mechanical circulatory support and more likely to be on inotropic support as a bridge to transplantation.64, 65 Sex differences in use of left ventricular assist devices continue to exist even after FDA approval of smaller continuous flow devices that fit in both women and men.65 Among non-urgent patients (UNOS Status 2), women have been shown to have slightly worse functional capacity defined as lower peak oxygen consumption (women vs men: 11 vs 12 mL/kg/min) at time of listing, yet better hemodynamics (women vs men: mean pulmonary artery pressure 26 vs 28 mmHg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure 17 vs 19 mmHg, and cardiac index 2.2 vs 2.1 L/min).64 In summary, there are several sex differences in baseline characteristics and medical support among patients awaiting transplantation.

Sex differences in heart transplant waitlist survival also have been known for over a decade, with women having a higher mortality than men despite improvements in mechanical circulatory support and similar frequency of women initially listed at the highest waitlist priority (Status 1A women vs men: 23% vs 23%).64, 65 Waitlist survival is dependent on both waitlist priority (UNOS Status) at time of listing and use of mechanical circulatory support, with the highest mortality among UNOS Status 1A patients and those without a ventricular assist device implanted.46 In a recently published analysis involving all adults listed for heart transplant in the United States between 2004–2015, women had higher mortality than men when listed high priority (UNOS Status 1A and 1B) and lower mortality than men when listed as low priority (UNOS Status 2). When stratified by era, UNOS Status 1A women had higher mortality than men between 2004–2011 with no sex difference after 2012. Among UNOS Status 1B, women had a worse survival than men between 2004–2008 and 2012–2015 with no sex difference in survival between 2009–2011.64 After adjusting for more than 20 risk factors including year of listing, mechanical circulatory support, peak oxygen consumption, and hemodynamics, female sex was associated with a higher mortality risk among patients initially listed as UNOS Status 1A (adjusted HR 1.14 [95% CI 1.01–1.29]) and UNOS Status 1B (adjusted HR 1.17 [95% confidence interval 1.05–1.30]) and a lower mortality risk among patients initially listed as UNOS Status 2 (adjusted HR 0.85 [95% confidence interval 0.76–0.95]). Lower mortality among women compared to men listed non-urgently is likely due to sex differences in survival among patients with similar peak oxygen consumption. There are no sex-specific transplant candidacy criteria for peak oxygen consumption, yet two large single center studies have shown better survival in women than men at any given peak oxygen consumption value except for women with an ischemic cardiomyopathy because they have survival more similar to men.66, 67 In summary, there are sex differences in survival among patients awaiting transplantation and these exist even among patients with similar medical urgency.

Why have current studies not identified the cause of the sex differences in pre-transplant survival? The reason is that the national transplant database is limited to certain variables and that the explanation for sex differences is likely complex. Transplant centers across the nation collect large amounts of data to determine candidacy but are only required to enter some of these variables into the national database. For instance, laboratory values like serum sodium and natriuretic peptides are not collected despite their known prognostic value. 2, 68 Certain hemodynamics like right atrial pressure and central venous pressure are also not captured making it difficult to determine when a candidate is not thriving because of right sided heart failure. Sensitized patients with pre-formed antibodies after pregnancy or blood transfusions have limited donor options and longer waiting times for transplantation.69, 70 However, data for panel of reactive antibodies (PRA) was not standardized until the end of 2009, when standardized calculated PRA was required to be entered into the national database). Other data like peak oxygen consumption is entered but due to a high degree of missingness (>30%) is not always used when adjusting for possible risk factors to predict survival. Finally, more than 10 simple sex-interactions have been identified for predicting pre-transplant survival and their relationship to survival is likely complex.66 The standard Cox proportional hazard model is commonly used for survival analyses yet limited by assumptions and ability to handle only simple interactions with imputation for only small to moderate levels of missing data. To overcome this barrier, machine learning methods will be necessary. For example, Random Survival Forest is a robust machine learning method that identifies risk factors without assuming parametric relationships (linear or nonlinear) to mortality or prior knowledge of interactions among variables. It can handle large degrees of missingness and complex interactions to establish interactions such as those published between sex, peak oxygen consumption and type of heart disease.66

Transplantation:

There are several sex differences in heart transplantation. Women are less frequently transplanted than men despite shorter waiting times for transplantation.46 In 2017, there were 3,244 heart transplantations involving 922 women and 2,322 men. To date, among patients transplanted yearly, women receive 26% and men 74% of the donor hearts.57 Factors affecting transplantation include sex of the donor and recipient, blood type, human leukocyte antigens (HLA) matching, body size, and heart transplant waitlist priority (UNOS Status).46 Ideally, the sex of the donor is matched to the sex of the recipient. Patients with AB blood type have the shortest waiting time while patients with blood type O have the longest, yet there are no sex differences in the frequency of blood types.64, 65 Patients with prior antibodies against different HLA groups occurring after blood transfusions or pregnancies would need to wait longer for an ideal match. Women are more likely to be sensitized than men but research in this area is limited. Matching the size of the donor to the recipient is recommended to prevent poor outcomes. The ideal method to match size of donor/recipient is controversial with many centers choosing organs within 20–30% of recipient body’s weight or matching by total heart mass predicted with age, height, weight and sex. 71 These requirements limit the available donors for a given patient and may contribute to sex differences in rate of transplantation. Finally, transplantation is dependent on waitlist priority with the shortest waiting time among those listed urgently (UNOS Status 1A) and the longest among those listed as non-urgent (UNOS Status 2).46 Although there is no significant difference in the frequency of women and men initially listed urgently, there are significant sex differences in the rate of transplantation.64

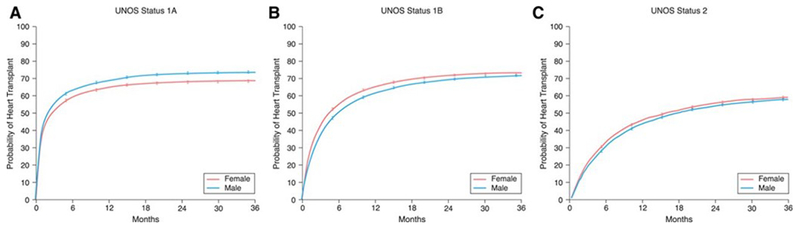

Women are less likely than men to be transplanted as UNOS Status 1A (most urgent) and more likely than men to be transplanted as UNOS Status 1B and 2 (Figure 5). When evaluating different eras, the probability of women being transplanted urgently (UNOS Status 1A) has not significantly changed between 2004-2015 yet has dropped for men, narrowing the sex difference gap. For those listed as UNOS Status 1B, the probability of transplantation has dropped for both women and men comparing 2004-2008 to 2012-2015, with women in the more recent era more likely than men to undergo transplantation. Among those listed as UNOS Status 2 (non-urgent), the probability for both women and men to be transplanted has dropped since 2004-2008 compared with 2012-2015 with no significant changes in the rate between women and men. Finally, machine learning statistical methods have identified more than 10 sex-interactions associated with the probability of transplantation, including body mass index, age, blood type O, hemodynamics, functional capacity, serum albumin and renal function and these interactions are likely to be complex.64

Figure 5.

Sex differences in heart transplantation based on initial United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Status. Sex-specific cumulative incidence curves were generated for all adults in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients initially listed as (A) UNOS Status 1A, (B) UNOS Status 1B, and (C) UNOS Status 2 between 2004-2015. Adapted from Hsich et al. with permission64

So why are women transplanted less frequently than men in the United States (26% women) and internationally (21% women)?57, 58 The reason remains unclear but may reflect known sex differences in heart failure or selection bias. Using Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure that included 99,930 patients admitted across the United States for heart failure, only 37% of women compared with 59% of men were admitted for acute decompensated heart failure with reduced ejection fraction <40% and women tended to be older than men (age median, IQR: women 74 years [62-83 years] vs men 69 years [57-79 years]).72 Therefore, although nearly 50% of heart failure patients in the United States are women, few are likely to be eligible for transplant due to sex differences in age among patients with reduced ejection fraction.

Post-transplantation:

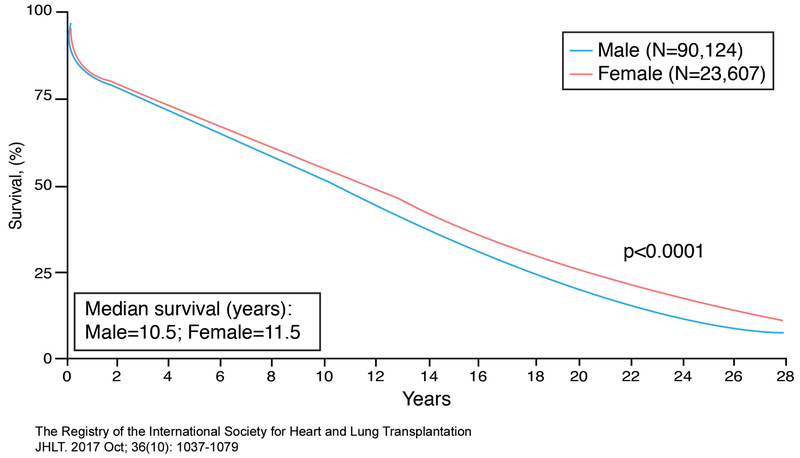

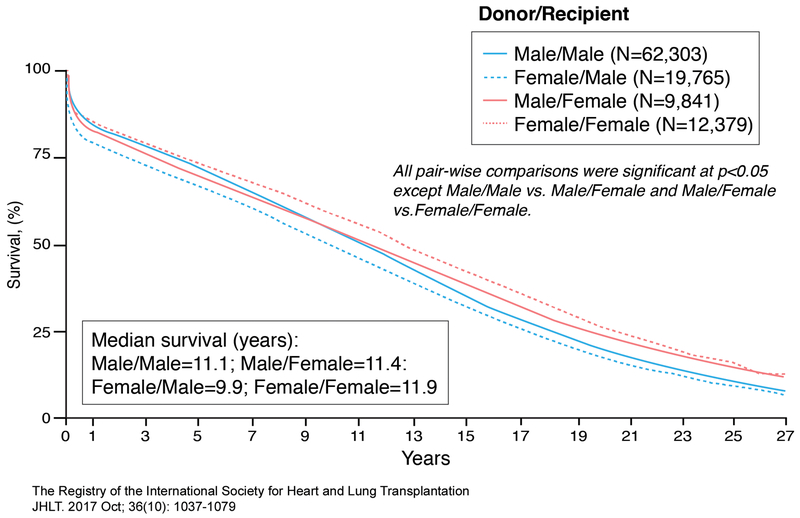

Women tend to have better long-term survival than men post-transplantation, lower risk of coronary allograft vasculopathy and malignancy, but a higher risk of antibody-mediated rejection.58, 73–75 The median survival for women is 11.5 yrs while for men is 10.5 years (Figure 6).58 Sex differences in outcome have been known for years and are dependent on time post-transplantation, sex of the donor, and sex of the recipient.58, 76 Early post-transplant mortality (< 1 year) is mainly due to graft failure, infection, and multi-organ failure while late post-transplant mortality (>3-5 years) is mainly due to malignancy, graft failure, and coronary allograft vasculopathy. Acute rejection causing death is less common and risk declines after the first 3 years post transplantation. Based on data between January, 1982 and June, 2015 from an international transplant registry that included the United States (Figure 7), 1 year unadjusted survival was best for male recipients receiving male donor hearts, intermediate for female recipients receiving either female or male donor hearts, and worst for male recipients receiving female donor hearts. Between 5-10 year post-transplantation unadjusted survival was notable for a change in the advantage of male recipients receiving male donor hearts with best survival among female recipients receiving female donor hearts compared to all other groups. Beyond 11 years post-transplantation, survival of female recipients was better than that of male recipients regardless of the sex of the donor. Although sex differences in post-transplant survival depend on time of assessment, patients do better when recipients receive donor hearts matched for sex rather than mismatched.58

Figure 6.

Sex-specific survival in adult heart transplant recipients. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were derived for women and men in the International Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) database who underwent heart transplantation between January 1982-June 2015. Adapted from ISHLT Registry with permission58

Figure 7.

Sex-specific Donor/Recipient survival in adult heart transplant patients. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were derived for women and men in the International Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) database who underwent heart transplantation between January 1982-June 2015. Adapted from ISHLT Registry with permission58

Discussion:

Why are there sex differences in mortality post-transplantation especially when sex of donor and recipient are mismatched? There are many hypothesis including hormonal factors, immunologic factors, and cardiac size mismatch but no clear answers. The ideal donor heart should be of adequate size to maintain the needs of the recipient but it is hard to predict the size of the donor heart by weight +/− height of the organ donor. In addition, hearts of females tend to be smaller than hearts of males raising the concern of possible cardiac size mismatch when the sex of the donor differs from the recipient. To investigate these concerns, a study using the national transplant registry between October 1989 and June 2011 assessed 1 and 5 year outcome based on predicted heart mass calculated from the weight, height, age and sex of the donor and recipient. Male recipients receiving female donor hearts often led to under-sizing of the heart in the recipient while female recipient receiving male donor hearts often led to over-sizing of the heart. Worst survival was among the male recipients of female donor hearts and those with undersized hearts. In a multivariable survival model, the sex difference in outcome for male recipient receiving female donor hearts was no longer present when adjusted for cardiac mass but was still a concern when comparing male recipients receiving male donor hearts to female recipients receiving female donor hearts suggesting that sex differences in outcome of the recipient is independent of cardiac mass.71

Conclusions

Based on the current literature with advanced heart failure and reduced ejection fraction there are many sex differences including less appropriate ICD shocks in women compared to men, greater benefit with CRT, similar survival benefits with left ventricular assist device but higher risk of neurologic adverse events, and worse survival while awaiting heart transplantation but slightly better survival than men after transplantation. Physiologic sex differences that may account for these finding include lower occurrence of ventricular arrythmias in women compared to men, sex differences in normal cardiac conduction, sex hormones affecting cardiac regulation of proteins,22 and sex differences in body size that could account for sex differences in adverse events and inappropriate size matching of donors to recipients. Limitations include under-representation of women in clinical trials and lack of prospective design to properly study sex differences. More research (Table 1) is needed to advance the field and improve care for both women and men.

Table 1.

Areas of Future Heart Failure Research Due to Gaps in Sex Specific Knowledge

| ICD | 1. Given the known sex differences in appropriate ICD shocks, what are the sex-specific risk factors for ventricular arrhythmias? |

| 2. Why do women have more adverse events after implantation of an ICD compared to men? | |

| CRT | 1. Given the known sex differences in utilization of CRT-P and CRT-D among all heart failure patients, are there similar sex differences among patients with advanced heart failure? |

| 2. Why do women have more adverse events after implantation of an ICD compared to men? | |

| MCS | 1. Given the improvement in VADs performance that now can be implanted in more petite patients, why has the ratio of women and men utilizing these devices remained unchanged? |

| 2. How can we reduce the risk of stroke for both women and men with MCS and should this be device specific? | |

| Transplantation | 1. Do the percent of women (22%) and men (78%) that undergo transplantation in the United States truly reflect the sex-differences in eligible heart failure patients with advanced disease given the fact that women are more likely than men to develop heart failure at advanced ages and with more co-morbidities than men? |

| 2. Why are women less likely than men to be bridged to transplantation with mechanical circulatory support? | |

| 3. Given the known sex differences in survival for any given peak oxygen consumption value, what are the sex specific values that best predict mortality and do these need to be dependent on underlying heart disease? | |

| 4. Why are women less frequently transplanted than men? | |

| 5. Why do sex differences in outcome of the recipient persistent even after adjustment for cardiac mass of the donor? |

ICD=Implantable cardioverter defibrillator, CRT= cardiac resynchronization therapy, CRT-D= cardiac resynchronization therapy with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, CRT-P= cardiac resynchronization therapy without an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, MCS=mechanical circulatory support, VADs=ventricular assist devices

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Dr. Hsich is supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institute of Health under Award Number R01HL141892 to study disparities in survival among heart transplant candidates and recipients. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O’Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2018;137:e67–e492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr., Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013. accf/aha guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsich EM, Pina IL. Heart failure in women: A need for prospective data. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:491–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtis LH, Al-Khatib SM, Shea AM, Hammill BG, Hernandez AF, Schulman KA. Sex differences in the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death. JAMA. 2007;298:1517–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hess PL, Hernandez AF, Bhatt DL, Hellkamp AS, Yancy CW, Schwamm LH, Peterson ED, Schulte PJ, Fonarow GC, Al-Khatib SM. Sex and race/ethnicity differences in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator counseling and use among patients hospitalized with heart failure: Findings from the get with the guidelines-heart failure program. Circulation. 2016;134:517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Khatib SM, Hellkamp AS, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC, Thomas KL, Al-Khalidi HR, Heidenreich PA, Hammill S, Yancy C, Peterson ED. Trends in use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy among patients hospitalized for heart failure: Have the previously observed sex and racial disparities changed over time? Circulation. 2012;125:1094–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaPointe NM, Al-Khatib SM, Piccini JP, Atwater BD, Honeycutt E, Thomas K, Shah BR, Zimmer LO, Sanders G, Peterson ED. Extent of and reasons for nonuse of implantable cardioverter defibrillator devices in clinical practice among eligible patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:146–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacFadden DR, Tu JV, Chong A, Austin PC, Lee DS. Evaluating sex differences in population-based utilization of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: Role of cardiac conditions and noncardiac comorbidities. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1289–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel NJ, Edla S, Deshmukh A, Nalluri N, Patel N, Agnihotri K, Patel A, Savani C, Bhimani R, Thakkar B, Arora S, Asti D, Badheka AO, Parikh V, Mitrani RD, Noseworthy P, Paydak H, Viles-Gonzalez J, Friedman PA, Kowalski M. Gender, racial, and health insurance differences in the trend of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (icd) utilization: A united states experience over the last decade. Clin Cardiol 2016;39:63–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zareba W, Moss AJ, Jackson Hall W, Wilber DJ, Ruskin JN, McNitt S, Brown M, Wang H. Clinical course and implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy in postinfarction women with severe left ventricular dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2005;16:1265–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russo AM, Stamato NJ, Lehmann MH, Hafley GE, Lee KL, Pieper K, Buxton AE. Influence of gender on arrhythmia characteristics and outcome in the multicenter unsustained tachycardia trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2004;15:993–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russo AM, Poole JE, Mark DB, Anderson J, Hellkamp AS, Lee KL, Johnson GW, Domanski M, Bardy GH. Primary prevention with defibrillator therapy in women: Results from the sudden cardiac death in heart failure trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2008;19:720–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghanbari H, Dalloul G, Hasan R, Daccarett M, Saba S, David S, Machado C. Effectiveness of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in women with advanced heart failure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1500–1506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santangeli P, Pelargonio G, Dello Russo A, Casella M, Bisceglia C, Bartoletti S, Santarelli P, Di Biase L, Natale A. Gender differences in clinical outcome and primary prevention defibrillator benefit in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:876–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sticherling C, Arendacka B, Svendsen JH, Wijers S, Friede T, Stockinger J, Dommasch M, Merkely B, Willems R, Lubinski A, Scharfe M, Braunschweig F, Svetlosak M, Zurn CS, Huikuri H, Flevari P, Lund-Andersen C, Schaer BA, Tuinenburg AE, Bergau L, Schmidt G, Szeplaki G, Vandenberk B, Kowalczyk E, Eick C, Juntilla J, Conen D, Zabel M. Sex differences in outcomes of primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy: Combined registry data from eleven european countries. Europace. 2018;20:963–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seegers J, Conen D, Jung K, Bergau L, Dorenkamp M, Luthje L, Sohns C, Sossalla ST, Fischer TH, Hasenfuss G, Friede T, Zabel M. Sex difference in appropriate shocks but not mortality during long-term follow-up in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Europace. 2016;18:1194–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacFadden DR, Crystal E, Krahn AD, Mangat I, Healey JS, Dorian P, Birnie D, Simpson CS, Khaykin Y, Pinter A, Nanthakumar K, Calzavara AJ, Austin PC, Tu JV, Lee DS. Sex differences in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator outcomes: Findings from a prospective defibrillator database. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russo AM, Daugherty SL, Masoudi FA, Wang Y, Curtis J, Lampert R. Gender and outcomes after primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation: Findings from the national cardiovascular data registry (ncdr). Am Heart J 2015;170:330–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lampert R, McPherson CA, Clancy JF, Caulin-Glaser TL, Rosenfeld LE, Batsford WP. Gender differences in ventricular arrhythmia recurrence in patients with coronary artery disease and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:2293–2299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rho RW, Patton KK, Poole JE, Cleland JG, Shadman R, Anand I, Maggioni AP, Carson PE, Swedberg K, Levy WC. Important differences in mode of death between men and women with heart failure who would qualify for a primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Circulation. 2012;126:2402–2407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tadros R, Ton AT, Fiset C, Nattel S. Sex differences in cardiac electrophysiology and clinical arrhythmias: Epidemiology, therapeutics, and mechanisms. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:783–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillis AM. Atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias: Sex differences in electrophysiology, epidemiology, clinical presentation, and clinical outcomes. Circulation. 2017;135:593–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer TH, Herting J, Eiringhaus J, Pabel S, Hartmann NH, Ellenberger D, Friedrich M, Renner A, Gummert J, Maier LS, Zabel M, Hasenfuss G, Sossalla S. Sex-dependent alterations of ca2+ cycling in human cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Europace. 2016;18:1440–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatterjee NA, Borgquist R, Chang Y, Lewey J, Jackson VA, Singh JP, Metlay JP, Lindvall C. Increasing sex differences in the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1485–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Randolph TC, Hellkamp AS, Zeitler EP, Fonarow GC, Hernandez AF, Thomas KL, Peterson ED, Yancy CW, Al-Khatib SM. Utilization of cardiac resynchronization therapy in eligible patients hospitalized for heart failure and its association with patient outcomes. Am Heart J 2017;189:48–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lund LH, Braunschweig F, Benson L, Stahlberg M, Dahlstrom U, Linde C. Association between demographic, organizational, clinical, and socio-economic characteristics and underutilization of cardiac resynchronization therapy: Results from the swedish heart failure registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2017;19:1270–1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sridhar AR, Yarlagadda V, Parasa S, Reddy YM, Patel D, Lakkireddy D, Wilkoff BL, Dawn B. Cardiac resynchronization therapy: Us trends and disparities in utilization and outcomes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2016;9:e003108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider PM, Pellegrini CN, Wang Y, Fein AS, Reynolds MR, Curtis JP, Masoudi FA, Varosy PD. Prevalence of guideline-directed medical therapy among patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator implantation in the national cardiovascular data registry during the years 2006 to 2008. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:2052–2056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alaeddini J, Wood MA, Amin MS, Ellenbogen KA. Gender disparity in the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy in the united states. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2008;31:468–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi L. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1539–1549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, Carson P, DiCarlo L, DeMets D, White BG, DeVries DW, Feldman AM. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2140–2150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuchert A, Muto C, Maounis T, Frank R, Ella RO, Polauck A, Padeletti L. Gender-related safety and efficacy of cardiac resynchronization therapy. Clin Cardiol 2013;36:683–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varma N, Manne M, Nguyen D, He J, Niebauer M, Tchou P. Probability and magnitude of response to cardiac resynchronization therapy according to qrs duration and gender in nonischemic cardiomyopathy and lbbb. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:1139–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zusterzeel R, Selzman KA, Sanders WE, Canos DA, O’Callaghan KM, Carpenter JL, Pina IL, Strauss DG. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in women: Us food and drug administration meta-analysis of patient-level data. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1340–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zusterzeel R, Curtis JP, Canos DA, Sanders WE, Selzman KA, Pina IL, Spatz ES, Bao H, Ponirakis A, Varosy PD, Masoudi FA, Strauss DG. Sex-specific mortality risk by qrs morphology and duration in patients receiving crt: Results from the ncdr. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:887–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varma N, Lappe J, He J, Niebauer M, Manne M, Tchou P. Sex-specific response to cardiac resynchronization therapy: Effect of left ventricular size and qrs duration in left bundle branch block. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2017;3:844–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jamerson D, McNitt S, Polonsky S, Zareba W, Moss A, Tompkins C. Early procedure-related adverse events by gender in madit-crt. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014;25:985–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghanbari H, Feldman D, Schmidt M, Ottino J, Machado C, Akoum N, Wall TS, Daccarett M. Cardiac resynchronization therapy device implantation in patients with therapeutic international normalized ratios. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2010;33:400–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Intermacs quarterly statistical report: 2017 q3. Available at https://www.Uab.Edu/medicine/intermacs/images/federal_quarterly_report/federal_partners_report_2017_q3.Pdf last assessed august 13, 2018.

- 40.Hsich EM. Does size matter with continuous left ventricular assist devices? JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:132–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bogaev RC, Pamboukian SV, Moore SA, Chen L, John R, Boyle AJ, Sundareswaran KS, Farrar DJ, Frazier OH. Comparison of outcomes in women versus men using a continuous-flow left ventricular assist device as a bridge to transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2011;30:515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsich EM, Naftel DC, Myers SL, Gorodeski EZ, Grady KL, Schmuhl D, Ulisney KL, Young JB. Should women receive left ventricular assist device support?: Findings from intermacs. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:234–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherazi S, Kutyifa V, McNitt S, Papernov A, Hallinan W, Chen L, Storozynsky E, Johnson BA, Strawderman RL, Massey HT, Zareba W, Alexis JD. Effect of gender on the risk of neurologic events and subsequent outcomes in patients with left ventricular assist devices. Am J Cardiol 2017;119:297–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morris AA, Pekarek A, Wittersheim K, Cole RT, Gupta D, Nguyen D, Laskar SR, Butler J, Smith A, Vega JD. Gender differences in the risk of stroke during support with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34:1570–1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Birks EJ, McGee EC Jr., Aaronson KD, Boyce S, Cotts WG, Najjar SS, Pagani FD, Hathaway DR, Najarian K, Jacoski MV, Slaughter MS. An examination of survival by sex and race in the heartware ventricular assist device for the treatment of advanced heart failure (advance) bridge to transplant (btt) and continued access protocol trials. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34:815–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colvin M, Smith JM, Hadley N, Skeans MA, Carrico R, Uccellini K, Lehman R, Robinson A, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Kasiske BL. Optn/srtr 2016 annual data report: Heart. Am J Transplant 2018;18 Suppl 1:291–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Acharya D, Loyaga-Rendon R, Morgan CJ, Sands KA, Pamboukian SV, Rajapreyar I, Holman WL, Kirklin JK, Tallaj JA. Intermacs analysis of stroke during support with continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices: Risk factors and outcomes. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:703–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meeteren JV, Maltais S, Dunlay SM, Haglund NA, Beth Davis M, Cowger J, Shah P, Aaronson KD, Pagani FD, Stulak JM. A multi-institutional outcome analysis of patients undergoing left ventricular assist device implantation stratified by sex and race. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heartmate ii left ventricular assist device: Fda summary of safety and effectiveness data. Available at https://www.Accessdata.Fda.Gov/cdrh_docs/pdf6/p060040b.Pdf last accessed august 13, 2018.

- 50.Dhruva SS, Redberg RF. Sex-specific outcomes for heartmate ii. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1285; author reply 1285-1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyle AJ, Jorde UP, Sun B, Park SJ, Milano CA, Frazier OH, Sundareswaran KS, Farrar DJ, Russell SD. Pre-operative risk factors of bleeding and stroke during left ventricular assist device support: An analysis of more than 900 heartmate ii outpatients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:880–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogers JG, Pagani FD, Tatooles AJ, Bhat G, Slaughter MS, Birks EJ, Boyce SW, Najjar SS, Jeevanandam V, Anderson AS, Gregoric ID, Mallidi H, Leadley K, Aaronson KD, Frazier OH, Milano CA. Intrapericardial left ventricular assist device for advanced heart failure. N Engl J Med 2017;376:451–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Milano CA, Rogers JG, Tatooles AJ, Bhat G, Slaughter MS, Birks EJ, Mokadam NA, Mahr C, Miller JS, Markham DW, Jeevanandam V, Uriel N, Aaronson KD, Vassiliades TA, Pagani FD. Hvad: The endurance supplemental trial. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:792–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldstein DJ, Mehra MR, Naka Y, Salerno C, Uriel N, Dean D, Itoh A, Pagani FD, Skipper ER, Bhat G, Raval N, Bruckner BA, Estep JD, Cogswell R, Milano C, Fendelander L, O’Connell JB, Cleveland J. Impact of age, sex, therapeutic intent, race and severity of advanced heart failure on short-term principal outcomes in the momentum 3 trial. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018;37:7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mehra MR, Naka Y, Uriel N, Goldstein DJ, Cleveland JC Jr., Colombo PC, Walsh MN, Milano CA, Patel CB, Jorde UP, Pagani FD, Aaronson KD, Dean DA, McCants K, Itoh A, Ewald GA, Horstmanshof D, Long JW, Salerno C. A fully magnetically levitated circulatory pump for advanced heart failure. N Engl J Med 2017;376:440–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mehra MR, Goldstein DJ, Uriel N, Cleveland JC Jr., Yuzefpolskaya M, Salerno C, Walsh MN, Milano CA, Patel CB, Ewald GA, Itoh A, Dean D, Krishnamoorthy A, Cotts WG, Tatooles AJ, Jorde UP, Bruckner BA, Estep JD, Jeevanandam V, Sayer G, Horstmanshof D, Long JW, Gulati S, Skipper ER, O’Connell JB, Heatley G, Sood P, Naka Y. Two-year outcomes with a magnetically levitated cardiac pump in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1386–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Organ procurement and transplantation network: National data. Available at https://optn.Transplant.Hrsa.Gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/ last accessed on august 20, 2018.

- 58.International thoracic organ transplant registry 2017 data slides: Heart. Available at https://ishltregistries.Org/registries/slides.Asp last accessed on august 20,2018.

- 59.Diaz-Molina B, Lambert JL, Vilchez FG, Cadenas F, Bernardo MJ, Velasco E, Martin M, Moris C. Quality of life according to urgency status in de novo heart transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 2016;48:3024–3026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Emin A, Rogers CA, Banner NR. Quality of life of advanced chronic heart failure: Medical care, mechanical circulatory support and transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stevenson LW, Kormos RL, Young JB, Kirklin JK, Hunt SA. Major advantages and critical challenge for the proposed united states heart allocation system. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016;35:547–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stevenson LW. Crisis awaiting heart transplantation: Sinking the lifeboat. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1406–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Unos transplant trends. Available at https://unos.Org/data/transplant-trends/ last assessed on august 20, 2018.

- 64.Hsich EM, Blackstone EH, Thuita L, McNamara DM, Rogers JG, Ishwaran H, Schold JD. Sex differences in mortality based on united network for organ sharing status while awaiting heart transplantation. Circ Heart Fail 2017;10: p e003635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morris AA, Cole RT, Laskar SR, Kalogeropoulos A, Vega JD, Smith A, Butler J. Improved outcomes for women on the heart transplant wait list in the modern era. J Card Fail 2015;21:555–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hsich E, Chadalavada S, Krishnaswamy G, Starling RC, Pothier CE, Blackstone EH, Lauer MS. Long-term prognostic value of peak oxygen consumption in women versus men with heart failure and severely impaired left ventricular systolic function. Am J Cardiol 2007;100:291–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elmariah S, Goldberg LR, Allen MT, Kao A. Effects of gender on peak oxygen consumption and the timing of cardiac transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:2237–2242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, Cropp AB, Anand I, Maggioni A, Burton P, Sullivan MD, Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Mann DL, Packer M. The seattle heart failure model: Prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1424–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alba AC, Tinckam K, Foroutan F, Nelson LM, Gustafsson F, Sander K, Bruunsgaard H, Chih S, Hayes H, Rao V, Delgado D, Ross HJ. Factors associated with anti-human leukocyte antigen antibodies in patients supported with continuous-flow devices and effect on probability of transplant and post-transplant outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015;34:685–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morris AA, Cole RT, Veledar E, Bellam N, Laskar SR, Smith AL, Gebel HM, Bray RA, Butler J. Influence of race/ethnic differences in pre-transplantation panel reactive antibody on outcomes in heart transplant recipients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:2308–2315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reed RM, Netzer G, Hunsicker L, Mitchell BD, Rajagopal K, Scharf S, Eberlein M. Cardiac size and sex-matching in heart transplantation : Size matters in matters of sex and the heart. JACC Heart Fail 2014;2:73–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hsich EM, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Hernandez AF, Eapen ZJ, Xian Y, Schwamm LH, Bhatt DL, Fonarow GC. Relationship between sex, ejection fraction, and b-type natriuretic peptide levels in patients hospitalized with heart failure and associations with inhospital outcomes: Findings from the get with the guideline-heart failure registry. Am Heart J 2013;166:1063–1071 e1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Eifert S, Kofler S, Nickel T, Horster S, Bigdeli AK, Beiras-Fernandez A, Meiser B, Kaczmarek I. Gender-based analysis of outcome after heart transplantation. Exp Clin Transplant 2012;10:368–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sorabella RA, Guglielmetti L, Kantor A, Castillero E, Takayama H, Schulze PC, Mancini D, Naka Y, George I. Cardiac donor risk factors predictive of short-term heart transplant recipient mortality: An analysis of the united network for organ sharing database. Transplant Proc 2015;47:2944–2951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grupper A, Nestorovic EM, Daly RC, Milic NM, Joyce LD, Stulak JM, Joyce DL, Edwards BS, Pereira NL, Kushwaha SS. Sex related differences in the risk of antibody-mediated rejection and subsequent allograft vasculopathy post-heart transplantation: A single-center experience. Transplant Direct. 2016;2:e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaczmarek I, Meiser B, Beiras-Fernandez A, Guethoff S, Uberfuhr P, Angele M, Seeland U, Hagl C, Reichart B, Eifert S. Gender does matter: Gender-specific outcome analysis of 67,855 heart transplants. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;61:29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.