Current language in the Food Safety Modernization Act Produce Safety Rule states no objection to a 90- or 120-day interval between application of untreated BSAAO and harvest of crops to minimize transfer of pathogens to produce intended for human consumption with the intent to limit potential cases of foodborne illness. This regional multiple season, multiple location field trial determined survival durations of Escherichia coli in soils amended with manure to determine whether this interval is appropriate. Spatiotemporal factors influence survival durations of E. coli more than amendment type, total amount of E. coli present, organic or conventional soil management, and depth of manure application. Overall, these data show poultry litter may support extended survival of E. coli compared to horse manure or dairy manure, but spatiotemporal factors like site and season may have more influence than manure type in supporting survival of E. coli beyond 90 days in amended soils in the Mid-Atlantic United States.

KEYWORDS: E. coli O157:H7, Escherichia coli, Mid-Atlantic, biological soil amendment, dairy manure, horse manure, manure, poultry litter, soil, spatiotemporal

ABSTRACT

Untreated biological soil amendments of animal origin (BSAAO), such as manure, are commonly used to fertilize soils for growing fruit and vegetable crops and can contain enteric bacterial foodborne pathogens. Little is known about the comparative longitudinal survival of pathogens in agricultural fields containing different types of BSAAO, and field data may be useful to determine intervals between manure application and harvest of produce intended for human consumption to minimize foodborne illness. This study generated 324 survival profiles from 12 different field trials at three different sites (UMES, PA, and BARC) in the Mid-Atlantic United States from 2011 to 2015 of inoculated nonpathogenic Escherichia coli (gEc) and attenuated O157 E. coli (attO157) in soils which were unamended (UN) or amended with untreated poultry litter (PL), horse manure (HM), or dairy manure solids (DMS) or liquids (DML). Site, season, inoculum level (low/high), amendment type, management (organic/conventional), and depth (surface/tilled) all significantly (P < 0.0001) influenced survival duration (dpi100mort). Spatiotemporal factors (site, year, and season) in which the field trial was conducted influenced survival durations of gEc and attO157 to a greater extent than weather effects (average daily temperature and rainfall). Initial soil moisture content was the individual factor that accounted for the greatest percentage of variability in survival duration. PL supported greater survival durations of gEc and attO157, followed by HM, UN, and DMS in amended soils. The majority of survival profiles for gEc and attO157 which survived for more than 90 days came from a specific year (i.e., 2013). The effect of management and depth on dpi100mort were dependent on the amendment type evaluated.

IMPORTANCE Current language in the Food Safety Modernization Act Produce Safety Rule states no objection to a 90- or 120-day interval between application of untreated BSAAO and harvest of crops to minimize transfer of pathogens to produce intended for human consumption with the intent to limit potential cases of foodborne illness. This regional multiple season, multiple location field trial determined survival durations of Escherichia coli in soils amended with manure to determine whether this interval is appropriate. Spatiotemporal factors influence survival durations of E. coli more than amendment type, total amount of E. coli present, organic or conventional soil management, and depth of manure application. Overall, these data show poultry litter may support extended survival of E. coli compared to horse manure or dairy manure, but spatiotemporal factors like site and season may have more influence than manure type in supporting survival of E. coli beyond 90 days in amended soils in the Mid-Atlantic United States.

INTRODUCTION

Biological soil amendments of animal origin (BSAAO), such as livestock manure, play an important role in conventional and organic agriculture. The application of BSAAO to soils provides essential nutrients of the soils over time, replenishing soil organic material (SOM), increasing bulk soil density, and enhancing soil water-holding capacity and soil structure (1, 2). The use of manure improves the soil nutrient status of eroded soils leading to higher yields of grain crops (1). Poultry litter (PL) and dairy manure are examples of useful organic fertilizers to supply levels of nitrogen (N) equivalent to chemical fertilizers to row and vegetable crops (3–6). Residual applications of poultry litter from previous years has also shown to increase release of plant available nutrients, indicating the long-term nutrient benefits which can be provided and potentially affect the soil microbiome (4, 7, 8). Ninety percent of poultry litter in the United States is applied to agricultural lands as the preferred method of animal manure management, simultaneously allowing crops to utilize nutrients and to prevent detrimental nutrient runoff to waterways (9, 10). Although there are many benefits derived from use of manure in crop production, there are also foodborne illness risks associated with use of raw or inadequately treated manure, which can harbor enteric pathogens that transfer to growing fruits and vegetables intended for human consumption (11). Manure from domesticated animals may contain numerous pathogens, including Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, Campylobacter spp., and Cryptosporidium parvum (12). Enteric pathogenic bacterial contamination on a variety of fruit and vegetable crops is difficult to remove completely, even with chemical and physical decontamination treatments (13, 14). Manure dust originating from a cattle feedlot can transfer E. coli O157:H7 to leafy green crops 180 m away (15). Manure dust can also serve to protect bacterial pathogens such as S. enterica from inactivation by UV components of sunlight, which can extend bacterial survival on leaves of growing spinach leaves (16). Human exposure to untreated animal manure or insect vectors can also lead to potential cases of infection with enteric pathogens (17, 18).

Almost 50% of cases of foodborne illness in the United States are associated with contaminated produce commodities (19). Outbreaks of bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections associated with contaminated produce have focused more attention on agricultural inputs like BSAAO used in fruit and vegetable production. An outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 infections in the United States sickened over 70 people and was associated with consumption of lettuce likely contaminated with manure runoff containing the pathogen from an adjacent cattle ranch (20). “Standards for the Growing, Harvesting, Packing and Holding of Produce for Human Consumption – Supplemental to the Proposed Rule” (Produce Safety Rule) from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have been issued to address the role of handling BSAAO to minimize contamination of growing fruit and vegetable crops (21). In the final rule, the FDA has specific criteria for use of BSAAO intended to grow fresh produce for human consumption, including that raw manure must not come into contact with produce during application. Currently, the FDA does not take exception to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Organic Program 90- or 120-day interval between application of manure to the field and the harvest of crops (22) while additional data are collected. However, field trials comparing different types of BSAAO as fertilizers to validate these 90- to 120-day intervals are lacking in the literature in the Mid-Atlantic United States.

While greenhouse experiments have shown that specific manure types support the survival of E. coli for longer durations compared to others (23, 24), field data on the survival of enteric pathogens in manure-amended soils in fields in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States are needed. The effect of manure amendment, depth (surface versus tilled), management (organic versus conventional), environmental factors, and climate variables remain undescribed in the literature. The results reported here use data from twelve field trials at three different geographic sites over 4 years to determine the survival duration of inoculated E. coli in manure-amended soils.

RESULTS

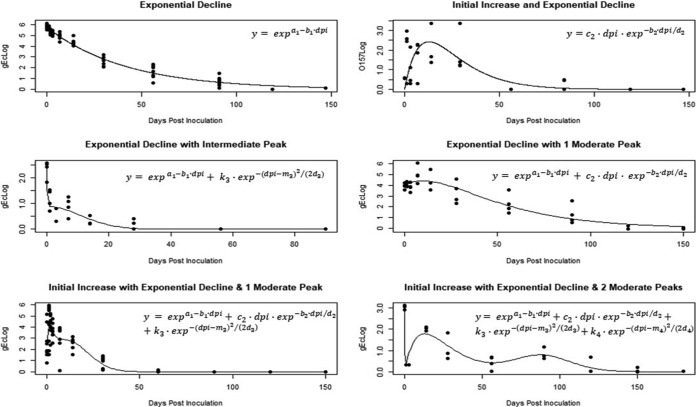

These results document the survival of a multistrain inoculum of nonpathogenic E. coli (gEc) and attenuated E. coli O157:H7 (attO157) in manure-amended or unamended soils at three different sites in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States during 12 different field trials spanning multiple seasons during a 4-year time period (2011 to 2015). The survival of gEc and attO157 was modeled by fitting one of six nonlinear regression curves (Fig. 1 and Table 1 ). The models were used to predict survival by estimating dpi100mort values, defined as the number of days postinoculation (dpi) in which the predicted log CFU (MPN)/gram dry weight (gdw) value reached 0.11 log MPN/gdw as a threshold of gEc and attO157 viability. Total observed variability in dpi100mort was characterized using analysis of variance (ANOVA)/analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) or random forest models to identify agricultural field factors, spatiotemporal factors, and/or weather factors that explained greatest proportions of the total variability.

FIG 1.

Statistical models for survival (log CFU/gdw) of gEc and attO157 in unamended soils or soils containing BSAAO.

TABLE 1.

Description of variables used in models describing survival of gEc and attO157

| Variable(s) | Description |

|---|---|

| expa1 | y intercept for the exponential decrease term |

| dpi | Day postinoculation |

| c2 | Rate of initial increase to maximum peak |

| b1, b2 | Rates of exponential decrease with respect to dpi |

| d2, d3, d4 | Peak shape parameters |

| m3, m4 | dpi estimates at first and second intermediate peaks (local maxima that occur at greater dpi than the initial maximum peak) |

| k3, k4 | Multipliers that increase or decrease the height (from base to peak) of the intermediate peaks |

Contribution of agricultural field, spatial temporal, and weather factors on survival of E. coli.

The proportions of dpi100mort variability (R2) explainable by specific combinations of three sets of factors—(i) agricultural field factors, including inoculum level (low or high), amendment type (dairy manure solids [DMS], dairy manure liquids [DML], horse manure [HM], poultry litter [PL], or unamended [UN]), management (organic or conventional), and depth (surface or tilled); (ii) spatiotemporal factors, including site, year, and season; and (iii) weather factors, including average daily rainfall and average daily temperature—determined by specific ANCOVA models are shown in Table 2 . Models solely containing weather effects (average daily rainfall, average daily temperature) accounted for 10% of dpi100mort variability for gEc and attO157, indicating that these factors had minor influence on dpi100mort values (survival durations) compared to agricultural field factors. An ANCOVA model composed of solely of initial soil moisture content (moisture content on day 0, day of manure application) accounted for the greatest percentage of dpi100mort variability for gEc (33%) and attO157 (29%) attributed to any single factor. Models containing agricultural field factors accounted for 41 and 35% of dpi100mort variability for gEc and attO157, respectively, roughly equivalent to models containing weather factors combined with initial moisture content (41 and 36%). Models consisting of spatiotemporal aspects of field location were responsible for explaining 40 and 32% of the experimental variance for gEc and attO157, respectively. Combinations of agricultural factors, spatiotemporal factors, and weather effects were able to account for the majority of the experimental variability better than the three individual groups themselves or than any individual group combined with initial moisture content. Combinations of agricultural factors, with weather effects and initial moisture content accounted for 59 to 68% of the observed dpi100mort variability, whereas the combinations of agricultural and spatiotemporal factors, along with initial moisture content, explained the greatest amount of variance (71 to 74%). Overall, the entire model, included nested effects, was able to explain approximately 98% of the variability. These results show that no single factor can explain the majority of the observed dpi100mort experimental variability. Instead, combinations of factors are needed to accurately assess the survival duration of E. coli in soils containing untreated BSAAO in field studies.

TABLE 2.

Percentage of variance (R2) accounted for by statistical models, including various combinations of agricultural field and weather effects

| Model | % variance (R2) |

|

|---|---|---|

| attO157 | gEc | |

| Avg daily temp and avg daily rainfall only | 10.0 | 10.7 |

| Initial moisture content only | 29.4 | 33.2 |

| Inoculum, amendment, management, and depth only | 35.1 | 41.4 |

| Avg daily temp and avg daily rainfall and initial moisture content | 36.9 | 41.4 |

| Inoculum, amendment, management, depth, and initial moisture content | 53.8 | 60.6 |

| Inoculum, amendment, management, depth, initial moisture content, avg temp, and avg rainfall | 59.9 | 68.3 |

| Site, yr, season | 40.1 | 32.7 |

| Site, yr, season, and initial moisture content | 51.9 | 48.9 |

| Site, yr, season, initial moisture content, inoculum, amendment, management, depth | 71.2 | 74.1 |

| Total variance (% explainable by saturated model), including all nested effects | 98 | 98.4 |

Table 3 shows the variability (R2) of dpi100mort values for gEc and attO157 associated with two models composed of agricultural field effects (separate models were needed to account for confounded variability). Table 3 shows both the weather effects/agricultural field effects model and the spatiotemporal effects/agricultural field effects accounting for dpi100mort of gEc and attO157. Average daily rainfall accounted for the greatest proportion of variability (16 to 26%) in Table 3. Average daily temperature accounted for a substantially greater percentage of dpi100mort variability for gEc (17%) than for attO157 (<1%). The effects of management and depth explained 11 to 21% and 10 to 15% of the variability, respectively, in the weather effects model. However, the residual variance (30 to 41%) was greater than the variance associated with any individual weather effect specified in the weather effects/agricultural effects model. In the spatiotemporal effects/weather effects model (Table 3), the greatest portion of variability (65 to 66%) was explained by year, a factor nested within site, followed by season (7 to 9%). Overall, the model with spatiotemporal effects explained a greater percentage of the variance (83 to 87%) compared to the model with weather effects (58 to 69%). In Table 3, individual factors which account for 0% of the variance indicated that these factors were either confounded with another model effect or their unique effects did not contribute to explaining any variability in dpi100mort values. Tables 2 and 3 indicate that weather effects may impact survival duration of gEc and attO157 in soils containing BSAAO less than spatiotemporal effects.

TABLE 3.

Percentages of the model’s total estimated dpi100mort covariance associated with each effect composing the weather effects or spatiotemporal effects nested agricultural field factors ANOVA model

| Model | % total estimated dpi100mort covariance |

|

|---|---|---|

| gEc | attO157 | |

| Weather effects | ||

| Avg daily temp | 17.8 | 0.9 |

| Avg daily rainfall | 16.7 | 26.5 |

| Min daily temperature | 0 | 0 |

| Max daily temperature | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Max daily rainfall | 0 | 0 |

| Initial moisture | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Inoculum (site) | 2.3 | 1.3 |

| Amendment (inoculum) | 0.5 | 1.7 |

| Management (inoculum, amendment) | 21.1 | 11.3 |

| Depth (inoculum, amendment, depth) | 10.6 | 15.9 |

| Residual | 30.4 | 41.9 |

| Total estimated covariance | 3,330.4 | 3,026.6 |

| Spatiotemporal effects | ||

| Site | 4.1 | 3 |

| Yr (site) | 66.8 | 65.5 |

| Season (site, yr) | 9.4 | 7.3 |

| Initial moisture | 0 | 0 |

| Inoculum (site, yr, season) | 3.6 | 3.8 |

| Amend (site, yr, season, inoculum) | 2 | 3.2 |

| Management (site, yr, season, inoculum, amendment) | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| Depth (site, yr, season, inoculum, management) | 0.4 | 0 |

| Residual | 12.9 | 17 |

| Total estimated covariance | 2,822.6 | 3,077.9 |

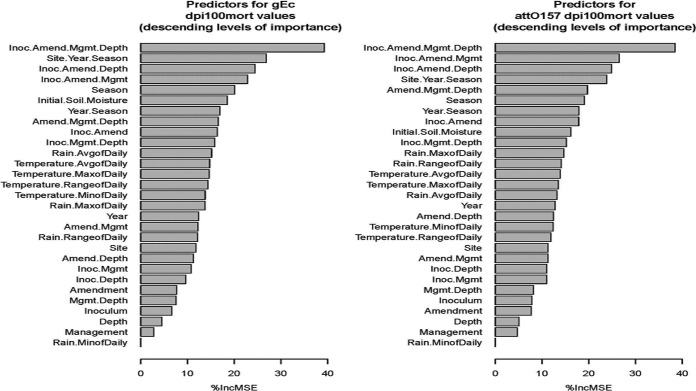

The relative importance of terms specified in a random forest model regarding the ability to accurately predict survival durations (dpi100mort) of gEc and attO157 are illustrated in Fig. 2. Terms used in the models included each agricultural factor, spatiotemporal factor, weather effect, and all combinations among agricultural factors and among spatiotemporal factors. Knowledge of the specific levels of all four agricultural factors (inoculum, amendment, management, and depth) resulted in the greatest improvement in the predictive accuracy of the random forest model for dpi100mort values for both gEc and attO157. Knowledge of the specific levels of only three of the four agricultural factors, either (i) inoculum, amendment, and depth or (ii) inoculum, amendment, and management, exhibited the ability to improve the accuracy of the random forest model in predicting dpi100mort values similar to the ability obtained from knowledge of the spatiotemporal factors (site, year, and season), or of initial soil moisture content (Table 2). Even though the importance rankings among the factor combinations specified in the random forest models (Fig. 2) differed slightly between gEc and attO157, the ten combinations of individual factors exhibiting the greatest ability to improve the models’ predictive accuracy of dpi100mort were all similar for gEc and attO157. Season and initial soil moisture content were the only individual factors identified among the 10 model terms that provided the greatest dpi100mort predictive accuracy. The random forest models confirmed the ANCOVA models (Tables 2 and 3), indicating that combined knowledge of all agricultural and spatiotemporal factors were better predictors of dpi100mort values than any individual factor or weather variable.

FIG 2.

Importance of agricultural and weather factors or combinations of factors in accurately predicting gEc or attO157 dpi100mort using random forest models.

Spatiotemporal factors.

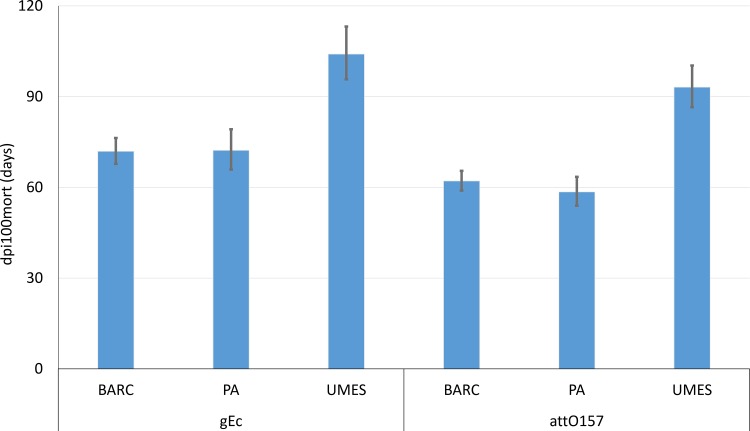

The random forest models identified combinations of several agricultural factors and spatiotemporal factors whose ability to improve predictive accuracy of dpi100mort warranted further exploration. The investigated agricultural factors (inoculum, amendment, depth, and management) were sequentially nested within each previous agricultural factor and the collection of all agricultural factors were nested within spatial temporal factors (site, year, and season), as documented in Table 3. For gEc and attO157, all agricultural and spatiotemporal ANOVA effects (Table 3) were significant (P < 0.0001; not shown) in affecting the dpi100mort values of gEc and attO157; the dpi100mort value at the UMES site was significantly greater than those at the two other sites (Fig. 3). For gEc, the mean (95% confidence interval) dpi100mort value at UMES (104.1 [95.7 to 113.2] days), the southernmost site, was greater than at PA (72.3 [65.9 to 79.2] days) or BARC (71.9 [67.8 to 76.3] days) (Fig. 3). For attO157, the dpi100mort values was significantly greater at UMES (93.2 [86.5 to 100.3] days) compared to either BARC (62.1 [59.0 to 65.5] days) or PA (58.5 [54.0 to 63.5] days) (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

dpi100mort values (survival duration) of nonpathogenic E. coli (gEc) and attenuated O157 E. coli (attO157) based on the site where field trials occurred. dpi100mort is defined as the shortest dpi at which predictions of log10(gEc+1) or log10(attO157 + 1) values dropped and remained below the viable threshold of 0.11 log CFU/gdw. dpi100mort values were determined by site regardless of inoculum, amendment, depth, or management. For both attO157 and gEc, survival durations at UMES were significantly (P < 0.0001) greater than survival at BARC or PA sites.

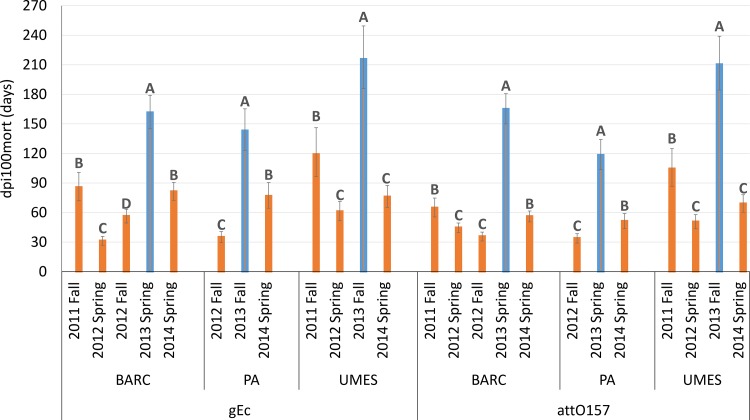

Season.

Within each site, the dpi100mort values for individual seasons were significantly different (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). Each site contained a different number of seasonal trials (BARC, n = 5; PA, n = 3; UMES, n = 4). Within each site, seasons in the year 2013 (BARC 2013 spring, PA 2013 fall, and UMES 2013 fall) had significantly greater dpi100mort values for gEc and attO157 than for all other seasons (Fig. 4). Estimates of survival durations (dpi100mort) for both gEc and attO157 in BARC 2013 spring were 161.1 (144.9 to 179.0) and 164.6 (149.9 to 180.7) days; those in PA 2013 fall were 142.7 (123.2 to 165.2) and 117.9 (103.5 to 134.2) days, and those in UMES 2013 fall were 215.3 (185.9 to 249.4) and 209.9 (184.3 to 239.0) days, respectively. Both trials conducted in the fall season at UMES (2011 fall and 2013 fall) had dpi100mort values for gEc and attO157 that exceeded 90 days, and the UMES site was the only site which had multiple seasons that supported dpi100mort values greater than 90 days. At the BARC and PA sites, the only seasons which had dpi100mort values greater than 120 days were BARC 2013 spring and PA 2013 fall.

FIG 4.

Within each inoculum (gEc or attO157) and site, seasonal dpi100mort values (survival durations) denoted by different capital letters are significantly (P < 0.0001) different from each other. dpi100mort values for 2013 seasons (blue bars) at each site had significantly greater dpi100mort values than seasons in other years.

Agricultural factors.

As described in Tables 2 and 3, along with site, year, and season, amendment type (P < 0.0001) and inoculum level (P < 0.0001) significantly influenced the survival durations of gEc and attO157 in various manure-amended soils. Inoculum level was also significant in affecting survival profiles, with high inocula of gEc and attO157 surviving for longer durations than low inocula in all amended soil treatments. These estimates of survival duration can be viewed individually for each of the 324 survival profiles (see Fig. 9, below).

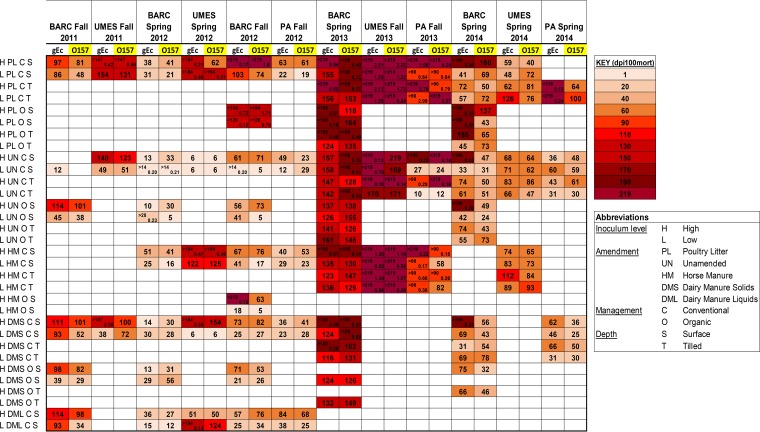

FIG 9.

Heat map illustrating model-predicted dpi100mort values (days) for the 324 observed survival profiles. Rows represent combinations of inoculum, amendment, management, and depth. Columns represent season and either gEc or attO157 (O157) E. coli inoculum. Cells split with a diagonal line identify profiles with model-predicted E. coli survival above the viable survival threshold (0.11 log MPN/gdw) at the largest dpi observed for that profile. The profile’s maximum observed dpi is listed in the upper half of a cell, with the model-predicted log MPN/gdw E. coli survival at this maximum observed dpi listed in a cell’s lower half. The color key facilitates interpretation of the dpi100mort (survival duration in days) values. Blank (white) spaces identify unobserved profiles.

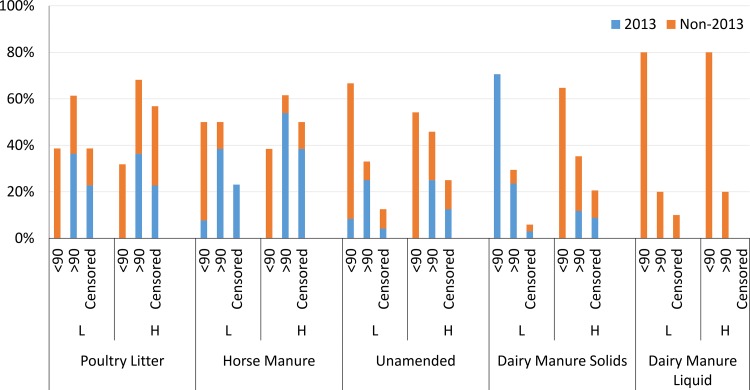

Examining survival durations of gEc and attO157 in trials conducted in specific years can clarify trends based on agricultural factors such as inoculum level and soil amendment type, depth, and management, while distinguishing the effect of year (seasons within a year). Since greater dpi100mort values were observed in all 2013 seasons at each site compared to others, survival trends in field trials conducted in 2013 (BARC 2013 spring, UMES 2013 fall, and PA 2013 fall) versus non-2013 season (all other nine seasons) were compared. Overall, 61% of the low-inoculum survival profiles in soils amended with PL (without regard to E. coli inoculum type, site, season, management, or depth) had dpi100mort values greater than 90 days, which was a greater percentage than those in the low inocula of HM (50%)-, UN (33%)-, DMS (25%)-, or DML (20%)-amended soils (Fig. 5). A greater proportion of survival profiles for low inocula in each amendment type which had dpi100mort values of >90 days came from the 2013 seasons compared to the non-2013 seasons (DML treatments were not evaluated in 2013 season). The percentages of low-inoculum profiles from 2013 seasons which had dpi100mort values of <90 days were 0, 7, 8, and 0% for PL-, HM-, UN-, and DMS-amended soils, respectively, showing that the majority of survival profiles which had dpi100mort values of <90 days came from non-2013 seasons. For the high-inoculum survival profiles, 68, 61, 45, 35, and 20% of survival profiles in PL-, HM-, UN-, DMS-, and DML-amended soils, respectively, had dpi100mort values of >90 days. For the high-inoculum treatments, no survival profile from a 2013 season in PL-, HM-, UN-, and DMS-amended soils had a dpi100mort value of less than 90 days. The censored category in Fig. 5 (see also Fig.S1 and S2 in the supplemental material) indicated the percentage of survival curves where the estimated log CFU value did not reach the detection limit—0.11 log CFU/gdw—by the maximum days postinoculation used in the model.

FIG 5.

Within each amendment type and inoculum level, the percentages of profiles (across all depths and management types) which had dpi100mort values of less than 90 (<90), greater than 90 (>90), or censored (not reaching the viable threshold of 0.11 log MPN/gdw by end of the sampling range) were determined. The blue/orange sections of each bar represent 2013/non-2013 profiles.

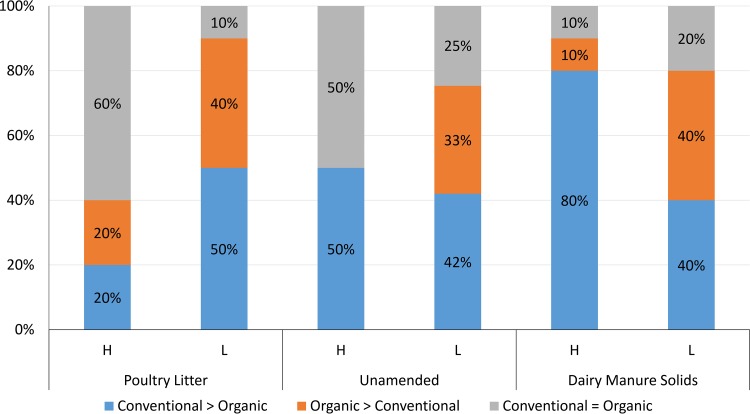

Management (organic or conventional) had a significant (P < 0.0001) effect on survival durations and was evaluated concurrently within the effect of amendment type (PL, UN, and DMS) and the inoculum level of gEc and attO157. Only the BARC site met criteria for the organic versus conventional management comparisons. The effect of management on dpi100mort values for gEc and attO157 was influenced by amendment type (Fig. 6). For PL-amended soils receiving a high inoculum (n = 10 comparisons), in 80% of the comparisons there were either no significant differences in dpi100mort values from conventionally and organically managed soils (60%), or the dpi100mort values were significantly greater in conventional than in organic soils (20%). For comparisons (n = 10) from poultry litter-amended soils receiving a low inoculum, dpi100mort values from conventionally managed soils were significantly greater than those for organically managed soils in 50% of the comparisons, and 10% of the comparisons showed no difference in dpi100mort values between conventional and organic soils. For unamended soils, in 50 and 42% of comparisons in high (n = 12) and low (n = 12) inoculum levels, respectively, dpi100mort values were greater in conventionally managed soils than organically managed soils. For high- and low-inoculum levels in unamended soils, 50 and 25% of the comparisons, respectively, had no significant differences between dpi100mort values for conventional and organic soils. In dairy manure-amended soils, 80 and 40% of the high-inoculum (n = 10) and low-inoculum (n = 10) comparisons, respectively, showed that dpi100mort values from conventional soils were greater than those from organic soils.

FIG 6.

Comparison of E. coli survival between conventionally and organically managed soils. Within each biological soil amendment type (PL, HM, UN, and DMS) and inoculum level (high or low), the percentages of survival profiles across five seasonal trials at the BARC site, E. coli type (gEc or attO157), and depth for which dpi100mort values of E. coli from conventional amended soils were significantly (P < 0.0001) greater than for organic amended soils (blue); or the organic amended soils were significantly greater than conventional soils (orange); or the conventionally and organically managed soils exhibited statistically similar survival durations (gray). The numbers of comparisons made for each amendment type and inoculum level (H and L) were as follows: poultry litter, H = 10, L =10; unamended, H = 12, L = 12; and dairy manure solids, H = 10, L = 10.

It is also useful to know how conventional and organic management of manure-amended soils affects dpi100mort relative to a 90-day interval, as previously discussed. The percentages of conventionally managed profiles that received a low inoculum of either gEc or attO157 that had dpi100mort values of >90 were 58, 30, and 17% for PL-, UN-, and DMS-amended soils, respectively; 70, 43, and 50% for PL-, UN-, and DMS-amended soils, respectively, receiving low inocula which were managed organically had dpi100mort values of >90 (Fig. S1). For profiles receiving a high inoculum of gEc and attO157 and which were conventionally managed, dpi100mort estimates were >90 in 61 and 50% of PL- and UN-amended soils, respectively; for those that were organically managed, dpi100mort values were >90 in 90 and 50% of PL- and UN-amended soils, respectively. Regardless of inoculum type, inoculum level, amendment type, or management type, no survival profile from the season BARC 2013 spring, the only year 2013 season included in the management comparison, had a dpi100mort value of <90 days.

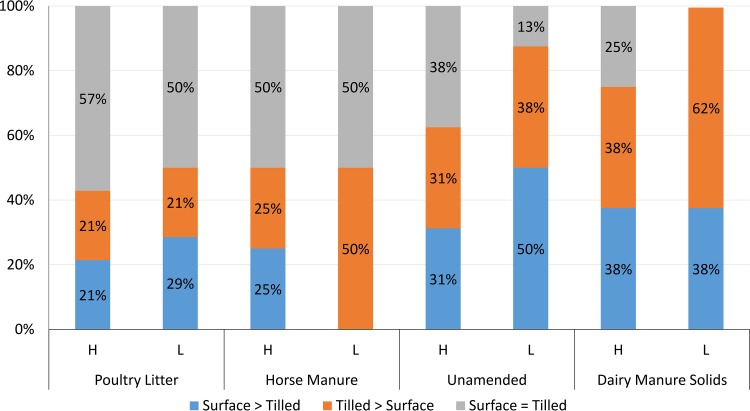

The effect of depth was evaluated similarly to the effect of management and was also significant (P < 0.0001), influenced greatly by specific amendment type and inoculum level. For all four amended soil types (PL, HM, UN, and DMS) receiving a high inocula of either gEc or attO157, the same trend was observed: the percentage of comparisons where dpi100mort values were greater in surface-amended soils compared to tilled soils and the percentage of comparisons where dpi100mort values were greater in tilled amended soils compared to surface-amended soils were equivalent (Fig. 7). In amended soils receiving a high inoculum of gEc and attO157, 57, 50, 33, and 25% of the comparisons in PL (n = 14)-, HM (n = 8)-, UN (n = 16)-, and DMS (n = 8)-amended soils, respectively, had dpi100mort estimates in surface and tilled amended soils that were not statistically different; in amended soils receiving a low inoculum, 50, 50, 13, and 0% of the comparisons in PL (n = 14)-, HM (n = 8)-, U (n = 16)-, and DMS-amended soils (n = 8), respectively, had dpi100mort for surface and tilled soils that were statistically equivalent. For low inocula in HM and DMS, in 50 and 62% of comparisons, respectively, the dpi100mort values were significantly greater in tilled soils compared to surface-amended soils.

FIG 7.

Comparison of E. coli survival between surface and tilled amendment application. Within each biological soil amendment type (PL, HM, UN, and DMS), inoculum level (high or low), the percentage of survival profiles across six seasonal trials at three field sites, E. coli type (gEc or attO157), and management type for which dpi100mort values of E. coli from surface soil amendment were significantly (P < 0.0001) greater than tilled soil amendment (blue); or the tilled amendments were significantly greater than the surface amendments (orange); or the surface and tilled amendments exhibited statistically similar survival durations (gray). The numbers of comparisons made in each amendment type and inoculum level (H and L) were as follows: poultry litter, H = 14, L =14; horse manure, H = 8, L = 8; unamended, H = 14, L = 14; and dairy manure solids, H = 8, L = 8.

Depth affected dpi100mort values for gEc and attO157 relative to 90 days in a fashion similar to those for the results reported in Fig. 5. PL- and HM-amended soil profiles, in general, supported gEc and attO157 dpi100mort values >90 compared to UN- and DM-amended soil profiles. The percentages of surface-amended profiles that received a low inoculum of either gEc or attO157 which had dpi100mort values of >90 were 64, 63, 38, and 50% for PL-, HM-, UN-, and DMS-amended soils, respectively; for those that were tilled, the percentage of profiles with dpi100mort values >90 were 69, 76, 38, and 50% for PL-, HM-, UN-, and DMS-amended soils, respectively (Fig. S2). The percentages of surface-amended survival profiles receiving a high inocula of gEc or attO157 where dpi100mort values were >90 were 86, 75, 50, and 38% for PL-, HM-, UN-, and DMS-amended soils, respectively; the percentages of tilled profiles where dpi100mort values were >90 were 63, 88, 50, and 25% for PL-, HM-, UN-, and DMS-amended soils, respectively. As observed with the results evaluating management, no survival profile conducted in the year 2013 had a dpi100mort of <90 days.

Weather effects.

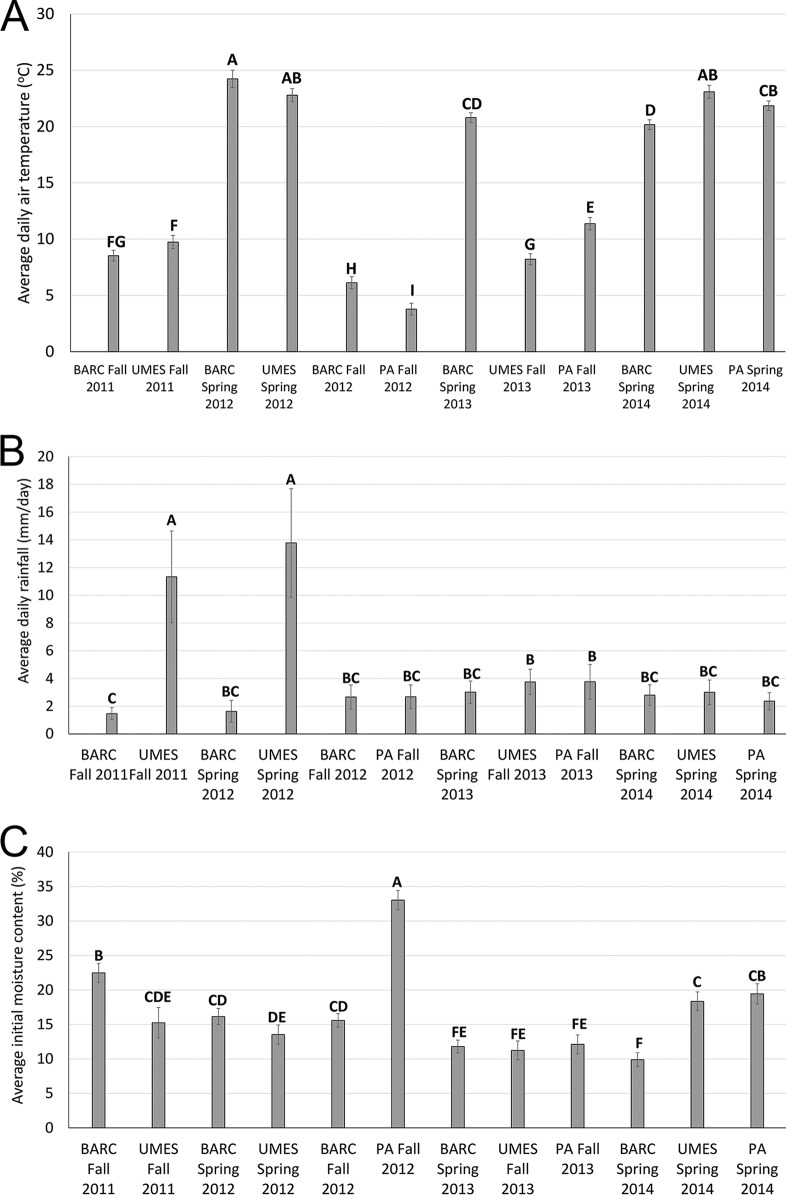

The findings for average daily air temperature, average daily rainfall, and initial soil moisture content for each of the 12 seasons evaluated are reported in Fig. 8. As expected, trials conducted during fall seasons had significantly lower mean daily air temperatures than those conducted during spring seasons (Fig. 8A). Two spring seasons, BARC 2012 spring and UMES 2012 fall, with high mean daily air temperatures (22.8 to 24.2°C) also had the shortest survival durations at their respective sites. The season with the lowest mean daily air temperature (PA 2012 fall) also had the shortest survival duration at the PA site. In general, the average daily rainfall values for most seasons were statistically similar with the exception of UMES 2011 fall and UMES 2012 spring seasons; however, the season with the highest average daily rainfall value (UMES 2012 spring) was also a season with the shortest survival duration at the UMES site (Fig. 8B). For initial soil moisture content evaluation (Fig. 8C), seasons in the year 2013 (BARC 2013 spring, UMES 2013 fall, and PA 2013 spring) which exhibited the longest survival durations compared to other seasons at each respective site, all had statistically similar initial moisture contents (11.2 to 12.1%), perhaps indicating this range of initial soil moisture content between 11 to 12% is associated with longer survival durations of gEc and attO157 populations, as Table 2 illustrates. PA 2012 fall had an initial moisture value content of 33%, which was significantly greater than all other seasons, but also had the shortest survival duration among the seasons evaluated at the PA site. All other seasons had initial moisture content values between 9.8 and 33.3%.

FIG 8.

(A) Average daily air temperature (°C); (B) average daily rainfall (mm/day); (C) average initial moisture (%) content of soils at 0 dpi. Seasons that contain different letters at the top of each bar are significantly (P < 0.05) different from each other.

Amendment effect.

The heat map (Fig. 9) shows the calculated dpi100mort estimates values (days) for both gEc and attO157 for each combination of inoculum, amendment, management, and depth for each site studied in each of the 12 seasons (324 profiles). There are two seasons (BARC 2013 spring and UMES 2013 fall) where none of the profiles (n = 76) evaluated had dpi100mort values of <116 days. In PA 2013 fall, only 6 of 24 profiles had dpi100mort values of <90 days, and 4 of these 6 profiles were from unamended treatments. In two seasons (BARC 2012 spring and PA 2012 fall), no survival profile (n = 48) had a dpi100mort value of >90 days. In two other seasons, UMES 2014 spring and PA 2014 spring, only 6 of 48 profiles had dpi100mort values that exceeded 90 days. When directly comparing survival durations of gEc and attO157 supported by different amendment types applied to the surface, PL supported longer survival durations more frequently than other amendment types (Table 4). Within each site, season, inoculum type (gEc or attO157), and inoculum level (low or high) in surface-amended soils, PL supported the longest duration of survival of gEc or attO157 in 60% of the comparisons (n = 48), followed by HM (27%), DMS (22%), and UN (20%). In some cases, more than one amendment type supported statistically equivalent durations of gEc or attO157.

TABLE 4.

Relative survival durations (dpi100mort) compared among biological soil amendments applied to conventional surfacesa

| Location | Season | Yr | gEc |

attO157 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High inoculum | Low inoculum | High inoculum | Low inoculum | |||

| BARC | Fall | 2011 | DML > DMS > PL | DML > DMS > PL | DML = DMS > PL | DML = DMS > PL |

| Spring | 2012 | HM > PL > DML > DMS > UN | UN > PL > DMS > HM > DML | PL = HM > DMS = UN = DML | UN = DMS > DML > PL > HM | |

| Fall | 2012 | PL > DMS > HM > UN > DML | PL > HM > DML > DMS > UN | PL > DMS = DML = HM = UN | PL > DML > DMS > HM > UN | |

| Spring | 2013 | PL = HM = DMS > UN | UN > PL > HM > DMS | PL = DMS = HM = UN | PL = DMS > UN > HM | |

| Spring | 2014 | DMS = PL = UN | DMS > PL > UN | PL > DMS > UN | PL > DMS > UN | |

| UMES | Fall | 2011 | DMS = PL > UN | PL > UN > DMS | PL > UN > DMS | PL > UN > DMS |

| Summer | 2012 | PL = DMS = HM > DML > UN | PL = DML > HM > DMS > UN | DMS > HM > PL > DML > UN | PL > DML = HM > DMS = UN | |

| Fall | 2013 | PL = HM = UN | PL = HM = UN | PL = HM = UN | PL > HM > UN | |

| Spring | 2014 | HM > PL > UN | HM > UN > PL | HM = UN > PL | PL = HM > UN | |

| PA | Fall | 2012 | DML > PL > UN > HM | DML > DMS > PL > UN | DML > PL > HM > DMS > UN | UN = DMS = DML = HM > PL |

| Fall | 2013 | PL = HM = UN | PL = HM > UN | PL = HM > UN | PL > HM > UN | |

| Spring | 2014 | PL > DMS > UN | PL > UN > DMS | PL > DMS > UN | PL > UN > DMS | |

Data are provided for within each site, year, and season at each level (low and high) of inoculum for gEc and attO157. “Greater than” symbols (>) separating amendments indicate significant (P < 0.0001) differences in the amendments’ model-predicted dpi100mort values. Equal signs (=) between amendments indicate no statistical difference between those amendments’ dpi100mort values. DML, dairy manure liquids; DMS, dairy manure solids; HM, horse manure; PL, poultry litter. High and low inoculum levels indicate that 6 or 4 log CFU/ml E. coli samples were applied to the plots.

DISCUSSION

The objective in this study was to determine factors and estimate durations of survival for E. coli introduced through the application of BSAAO to soils used to grow fruits and vegetables typically consumed raw. Since current metrics from the USDA National Organic Program and the proposed U.S. FDA FSMA Produce Safety Rule are expressed in number of days, we chose to analyze these results in terms of the survival duration (days, dpi100mort) of gEc and attO157.

Survival durations for E. coli in manure-amended soils in the Mid-Atlantic United States are affected by both spatiotemporal and agricultural factors, and both are required to accurately evaluate durations of bacterial pathogens in soils used for fresh fruit and vegetable crop production. Evaluating a single spatiotemporal or agricultural factor renders an incomplete assessment of survival of E. coli in manure-amended soils. The ANOVA model constructed here to account for E. coli survival in manure-amended soils (Table 2), using a combination of spatiotemporal factors site, year, and season, accounted for 32.7 to 40.1% of the variance in dpi100mort, which is roughly equivalent to the percentage of variance (35 to 41%) associated with the model only including agricultural factors of inoculum, amendment, management, and depth. The spatiotemporal effects/agricultural effects model accounts for a greater percentage of covariance than the weather effects/agricultural effects model (Table 3), with the effect year accounting for between 65.5 and 66.8% of the influence on the dpi100mort values of gEc and attO157. In contrast to several other studies examining survival of the same inoculated bacterial strains to manure-amended soils, the present study gives more weight to spatiotemporal factors and their effect on attenuated E. coli O157:H7 survival in manure-amended soils than do previous studies. Other investigators modeling E. coli survival in either unamended soils or soils amended with composted or thermally dried biosolids in three different seasonal trials showed that different factors (time after application of biosolids, soil moisture, and soil temperatures) had different levels of contribution to the survival of E. coli depending on the presence of amendments (25). In that study, a combination of time after application, soil moisture, and soil temperature explained 66.8 and 43% of the E. coli survival in unamended soils or in soils amended with composted or thermally dried biosolids, respectively. In that study, seasonal trials influenced how much soil moisture contributed to E. coli survival to a much greater extent in unamended soils (33%) compared to amended soils (3.2%) (25). Those results are in partial agreement with our findings which show that seasonality was a prominent factor extending survival duration of gEc and attO157 populations in specific seasons. However, the results presented here differ from those results with regard to soil moisture.

Seasons with lower initial soil moisture content (11.2 to 12.1%)—i.e., the BARC 2013 spring, PA 2013 fall, and UMES 2013 fall seasons—supported longer durations of survival compared to other seasons in our study (Fig. 4 and 8C). Conversely, seasons which had higher initial soil moisture contents supported shorter survival durations at each respective site. In 2012, four seasonal studies—BARC 2012 spring, UMES 2012 spring, BARC 2012 fall, and PA 2012 fall, which had initial moisture contents of 16.1, 13.5, 15.5, and 33.0%, respectively—supported the shortest durations of gEc and attO157 survival at each site. For all seasons in 2012, only the UMES 2012 spring had an initial moisture content statistically similar to the 2013 seasons; all other seasons in year 2012 had initial moisture content percentages that were significantly greater than those for the 2013 seasons at the same site. A statistical model consisting only of initial soil moisture content (Table 2) explained more (29.4 to 33.2%) of the variation in survival durations for gEc and attO157 than models containing average daily temperature and daily rainfall (10 to 10.7%). The addition of initial soil moisture content as a factor to a model consisting of inoculum, amendment, management, and depth increased the percentages of attributed variance from 35.1 to 53.8% and from 41.4 to 60.6%, respectively, for dpi100mort for attO157 and gEc; similarly, the addition of initial soil moisture content to a model of spatiotemporal factors (site, year, and season) increased the percentages of attributed variance from 40.1 to 51.9% and from 32.7 to 48.9%, respectively, for attO157 and gEc. The role of low soil moisture content in amended soils promoting attO157 and gEc survival is in agreement with an extensive review of 151 data sets from 70 publications which indicated that lower soil water content values (dry soils) promoted slower E. coli population declines compared to higher soil water content (wet soils) (26). The low moisture content of the soils may have provided E. coli cells in the gEc and attO157 inocula a survival advantage due to specific dessication stress responses (27). Previous work has shown that E. coli cells synthesized more trehalose under soil dessication conditions than hydrated conditions and that E. coli isolates from soil produced greater concentrations of trehalose compared to reference (laboratory) E. coli strains. Trehalose synthesis is controlled by the otsA and otsB genes in E. coli, and both genes are regulated within the rpoS-dependent response (28). E. coli O157:H7 isolates from a longitudinal examination of cattle manure-amended sandy soil showed that isolates that survived for the longest duration (>200 days) had fully functional rpoS genes, whereas isolates that survived for shorter durations (<200 days) had mutations within the rpoS gene, making them dysfunctional (29, 30). The level of expression of rpoS in E. coli O157:H7 was elevated 2.7-fold in sterile soil microcosms compared to Luria-Bertani media in other work (31). Survival of Salmonella enterica in turkey manure dust with a 5% moisture content was greater (291 days) than in manure with a 10% moisture content (88 days) or a 15% moisture content (68 days) (16), again indicating that drier conditions may support longer durations of enteric pathogen survival. E. coli populations isolated from soils have a broader growth range than laboratory strains, and specific proteins involved in periplasmic uptake and motility are upregulated, indicating their potential adaptability and predisposition to survive in nonhost conditions such as manure-amended soils (32, 33). In our study, using multiple E. coli isolates (TVS 353, 354, and 355) originating from agricultural environments may have allowed E. coli populations to decline more slowly and survive for longer durations under specific conditions of spatiotemporal and agricultural factors.

A study examining the survival of a nalidixic acid-resistant strain of attenuated E. coli O157:H7 (ATCC 700728, same as the PTVS 155 strain used in our experiments) at two geographically different sites, with different soil types, in Canada reported that site and depth were not determinative factors of E. coli O157:H7 survival in soils amended with dairy manure liquid (34). The extent to which the use of a single strain within a single season may have influenced these results is difficult to ascertain. In that study, survival durations for the attenuated strain of E. coli O157:H7 did not exceed 22 days with an approximate initial population of 5 log CFU/g. In our study, survival durations for attO157 applied as a low or high inoculum to soils amended with dairy manure liquids (Fig. 9, entries L DML C S and H DML C S, respectively) ranged between 12 and 154 days over five seasons evaluated, with, in general, longer survival durations observed for the treatments receiving high inocula (Fig. 9). The results observed from Bezanson et al. (34) would be among the shorter durations of attO157 survival found in results reported here. The preparation and composition of inoculum of E. coli O157:H7 may also account for longer survival durations observed in our study. The inoculum used in the present study consisted of multiple strains of both nonpathogenic E. coli (gEc) and attenuated E. coli O157:H7 (attO157) cultured in dairy manure or poultry litter extract, whereas the previous study only used a single strain cultured in tryptic soy broth, which may not endure nonhost conditions as well as other strains. The use of dairy manure or poultry litter extract to culture the E. coli strains in the inoculum (24), along with allowing them to achieve stationary phase during 24 h of incubation at 4°C, may have decreased potential nutritional and temperature shock of E. coli cells when introduced to soils. The choice of inoculum preparation methods are in accordance with recommendations previously presented in the literature on best practices for conducting experiments on survival of bacterial pathogens in soils containing untreated BSAAO (35). Our work shows the importance of using multiple strains in an inoculum to minimize the influence of a single strain and evaluating them over multiple seasons to truly gauge the effect of seasonal and site locations on survival duration of attenuated E. coli O157:H7.

Other studies evaluating the influence of spatial and temporal factors on persistence of nonpathogenic, indigenous populations of E. coli in bovine manure-amended soils have shown that different sites did not influence survival durations as much as time after application, depth, and manure application rate (36). Higher manure application rates, perhaps containing higher E. coli populations, supported longer survival durations than lower applications. This same study also showed that survival durations were greater in fall seasons (252 to 280 days) compared to summer seasons (56 to 112 days) and that soil and air temperatures were significantly lower in the fall (17 to 19°C) compared to the summer (26 to 27°C) season (36, 37). Two of the three seasons in our study which supported longest survival durations for attO157 and gEc were conducted in the fall—PA 2013 fall and UMES 2013 fall (Fig. 4)—and had air temperatures between 8 and 11°C (Fig. 8). However, a spring season (BARC 2013 spring) also supported longer survival durations of gEc and attO157 but had a mean air temperature of 22.7°C. These data and findings indicate that seasonality and temperature may drive survival duration of E. coli in soil containing untreated BSAAO, but these weather effects should be evaluated concurrently with spatiotemporal and agricultural factors.

Previous work did not find differences in the duration or level of E. coli survival in manure-amended soils based on location (34, 37). However, our work showed that site, in combination with year and season, was a major factor in accounting for variation in gEc and attO157 survival durations. In a previous greenhouse study, unamended silty loam soil from the BARC site supported statistically similar levels of attO157 and gEc survival as sandy loam soils from the UMES site (24). The previous greenhouse study shows that the intrinsic nutrient quality of soils may not differ enough to cause differences in survival of gEc; therefore, site-specific spatiotemporal factors and weather effects may account for longer survival durations of gEc and attO157 at specific locations. From the weather effects/agricultural effects model (Table 3), daily average rainfall accounted for a relatively small percentage of the variation in gEc (26.5%) and attO157 (21.1%) survival durations, indicating average daily rainfall is the weather effect that may contribute most to gEc and attO157 survival in all soils. In the agricultural factor model (Table 3), the nested factor year (within site) accounted for the greatest percentage of variation in survival duration (65.5 to 66.8%) of gEc and attO157, again indicating that temporal factors can greatly influence the survival duration of E. coli.

Other work evaluating the survival of a multistrain inoculum of nonpathogenic E. coli in soils flooded with diluted dairy manure runoff has shown that survival durations in a clay loam soil were longer in a fall season compared to spring season (38). In that study, slow die-off E. coli in manure-amended soils in the fall season compared to a spring season was attributed to lower temperatures and exposure to less UV (i.e., UV-B) radiation. Furthermore, less E. coli were transferred to growing spinach plants in the spring compared to the fall season due to the lower E. coli populations present in the soil. Similarly, E. coli and enterococci populations in grassland plots amended with dairy manure slurry had greater half lives in autumn and summer seasons compared to a spring season (39). Other researchers have shown that survival durations of E. coli O157:H7 differ in different spring seasons evaluated at the same site (40). These results support findings presented here showing that seasonality plays a large role in determining the extent of survival of E. coli populations in manure-amended soils, which can potentially affect transfer to edible portions of leafy green plants. As shown in Fig. 3 and 9, the season which supported the longest survival duration in was UMES 2013 fall for both gEc and attO157 inocula. Even gEc and attO157 in unamended treatments in UMES 2013 fall survived for durations equivalent to those that were amended, indicating the strong influence of seasonal variations on E. coli survival in amended and unamended soils.

As shown in Fig. 5 and 9, there were differences in survival duration based on the type of manure amendment applied to the soils. PL supported longer durations of survival compared to horse manure or dairy manure and was the only amendment type in which the majority of the low-inoculum profiles (61%) had dpi100mort values exceeding 90 days. The majority of PL (68%) and HM (62%) profiles receiving high inocula had dpi100mort values greater than 90 days. However, the high-inoculum survival profiles in HM were more affected by seasonality than the survival profiles in PL, as indicated by low percentage (8%) of HM profiles in non-2013 seasons, which had dpi100mort values of >90 days, compared to 32% of PL profiles in non-2013 seasons.

The cumulative results of Table 4 and Fig. 9 show that PL-amended soils extended the survival of gEc and attO157 more than HM-, UN-, DMS-, or DML-amended soils. Table 4 shows a relative comparison of dpi100mort values for gEc and attO157 between PL, HM, UN, DMS, and DML in surface-amended soils. Results presented here are supported by work in a previous greenhouse study which showed that PL-amended soils supported greater survival of gEc and attO157 compared to HM- or UN-amended soils (24), perhaps due to the greater nutrient concentrations (phosphorus or nitrogen) utilized by gEc and attO157 compared to HM- or UN-amended soils. Chemical characteristics of amendments used in the present field study were the same as reported previously (24). This differs from the findings of previous authors who found no difference in survival of E. coli O157:H7 in swine- and dairy manure-amended soils (40). Other researchers, examining dairy manure-amended soils, described high levels of dissolved organic carbon and carbon/nitrogen ratios in organic and conventional soils, respectively, extending the survival of E. coli O157:H7 in laboratory studies (41). As stated above, field trials conducted in the year 2013 promoted longer survival durations of gEc and attO157 at each site evaluated regardless of amendment and depth. Examining the survival in non-2013 years (Fig. 5 and 9) of a low inoculum applied to amended soils may provide a perspective which focuses on the effect of amendment while minimizing the influence of year and season on E. coli survival. In non-2013 seasons, PL-amended soils supported a greater percentage (25%) of survival profiles which had dpi100mort values greater than 90 compared to those of HM (11%)-, UN (8%)-, and DMS (5%)-amended soils receiving a low inoculum of gEc or attO157. For the high-inoculum survival profiles evaluated in non-2013 seasons, 31, 11, 20, 23, and 20% of those in PL-, HM-, UN-, DMS-, and DML-amended soils, respectively, had dpi100mort values exceeding 90 days. The results of these studies conducted in non-2013 years show that specific amendment types (e.g., PL) can promote survival of E. coli beyond a 90-day interval between manure application and harvest of fresh fruit or vegetable crop more frequently than other BSAAO types.

The evaluation of gEc and attO157 dpi100mort values in relation to the 90-day interval is relevant to current rules pertaining to the use of BSAAO in soils considered by FDA and in current use by the USDA National Organic Program. Two distinct scenarios from our study representing short and long survival durations may be illustrative to represent the challenge of evaluating and predicting survival durations of gEc and attO157 in manure-amended soils. Studies conducted in 2013, specifically UMES 2013 fall, represent a scenario where gEc and attO157 survival in both low and high inocula of three different amendment types (PL, HM, and UN) was extended by a combination of spatiotemporal factors (site and year) and amendment type. In the UMES 2013 fall study, the minimum survival duration of gEc or attO157 was 169 days. PL-amended soils receiving a high inoculum of gEc or attO157 supported populations that were estimated 2.31 and 2.32 log CFU/gdw after 219 days (these treatments were censored, indicating that the populations did not decline to 0.11 log CFU/gdw detection limit by the maximum dpi observed in the model) which were the highest censored log CFU/gdw values in any of the 12 seasons in this study. In the three seasons evaluated in 2013 (BARC 2013 spring, UMES 2013 fall, and PA 2013 fall), 100 survival profiles were evaluated, only six gEc or attO157 survival profiles had dpi100mort values of <90 days. This finding is in contrast to the second scenario of the four field trials conducted in 2012. In these seasons, only 19/104 (18%) of the survival profiles exceeded 90 days, and 15/19 of those were for PL- or HM-amended soils. Eleven of these nineteen profiles had dpi100mort values exceeding 90 days and were from the UMES 2012 spring trial, which had a statistically similar initial soil moisture content compared to the field trials conducted in 2013. Neither the BARC 2012 spring trial nor the PA 2012 fall trial contained any survival profiles that exceeded 90 days. These findings reinforce the spatiotemporal (site, year, and season) influence on gEc and attO157 survival in manure-amended soils and also indicates that poultry litter- and horse manure-amended soils are more likely to support longer durations of survival compared to other BSAAO types even when the spatiotemporal effects are not favorable for E. coli survival. The potential influence of initial soil moisture content of manure-amended soils on E. coli survival duration deserves more examination. It should be noted that results presented here are applicable to the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, and differences in the spatiotemporal and amendment effects on survival duration may occur in other geographic regions.

With regard to management and depth, it is difficult to consider their independent effect on survival of gEc and attO157 without considering inoculum level or amendment type (Fig. 2). Management affected the survival of gEc and attO157 in PL-amended soils to lesser extent than in UN- and DMS-amended soils. In unamended and dairy manure-amended soils it was more frequently observed that gEc and attO157 in high inocula survived for longer durations in conventionally managed soils than organically managed soils (Fig. 6), findings that agree with those from other studies (42). When evaluating the effect of depth (Fig. 7), low gEc and attO157 inocula in HM-amended soils were the only amendment/inoculum treatment where no surface-amended profiles survived for greater durations than tilled-in profiles. Other work has shown that E. coli survival durations were greater in grassland soils injected with dairy manure slurry compared to soils where dairy manure was surface broadcast (39). Similarly, E. coli O157:H7 survival durations were also greater at a depth of 15 cm in swine and dairy manure-amended soils than in surface-amended soils (40).

In summary, the spatiotemporal effects significantly affected the duration of survival of E. coli in soils containing BSAAO more than other agricultural factors, such as the type of manure amendment, management, or depth in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. The initial soil moisture content at the date of BSAAO application may be inversely related to the survival duration of E. coli in soils containing in specific seasons and, in conjunction with other agricultural factors, may have potential as a predictor of E. coli survival duration in soils. In general, poultry litter and, to a lesser extent, horse manure were able to support longer survival durations of E. coli in soils containing BSAAO compared to dairy manure solids or liquids in specific seasons. The influence of spatiotemporal factors and manure amendment were responsible for extending the survival of nonpathogenic E. coli and attenuated E. coli O157 past 90 days. The survival of E. coli in soils containing BSAAO cannot solely be assessed using agricultural factors and must include the evaluation of spatiotemporal factors in specific geographic regions in the United States.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Locations.

Three field sites in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States were used in this study. All sites contained silt loam soils. The field site at the U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service Northeast Area (USDA ARS NEA) Beltsville Agricultural Research Center (BARC), Beltsville MD (39.0254895°N, –76.92339801°W) contained Keyport series soils (taxonomic class: fine, mixed, semiactive, mesic Aquic Hapladults) and Matawan series soils (taxonomic class: fine loamy, siliceous, semiactive, mesic Aquic Hapladults). The University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES, 38.2102166°N, –75.68480019999998°W) contained Othello series soils (taxonomic class: fine-silty, mixed, active, mesic Typic Endoaquults). The site located in Pennsylvania (PA) at the Southeastern Agricultural Research Center, State University of Pennsylvania, Landisville, PA (40.11383490920206°N, –76.42605476826174°W) contained Hagerstown series (taxonomic class: fine, mixed, semiactive, mesic Typic Hapladalfs). Table S1 lists the locations and seasons in which these experiments were conducted. Twelve different field trials were conducted over the course of this experiment.

Manure application.

Manure was collected from the following sources: dairy manure solids (DMS) and liquids (DML), USDA ARS, Beltsville, MD; horse manure (HM), University of Maryland; and poultry litter (PL), University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES) poultry houses. Unamended plots (UN), which received no manure amendments, were also included. Testing of physical and chemical properties of PL, HM, and DMS was conducted by commercial laboratories (Waypoint Analytical (Richmond, VA) by methods referenced previously (23, 24). At each site, manure was added to a 2-m2 (1- by 2-m) plot. PL (2.27 kg/2 m2) was added to plots based on an application rate equivalent to 5 tons/acre (4.54 metric tons per 0.4 ha), while HM (2.27 kg/2 m2), DML (38 liters/2 m2), and DMS (2.27 kg/2 m2) were added based on an application rate of 5 tons per acre. Manure was manually applied either the night before the beginning of the study (day 0) or the morning of the beginning of the study, based on weather conditions. Manure was evenly distributed over the entire 2-m2 area of the plot before spray inoculation with attenuated O157 or nonpathogenic Escherichia coli. A randomized complete block experimental design was used at each field site in each separate season with four replicate plots for each BSAAO treatment in each field trial.

Preparation of poultry litter extracts.

The preparation of poultry litter extract (PLE) for cultivation of E. coli strains to be inoculated to field plots is similar to the procedure described previously (24). Poultry litter (200 g) was diluted 1:10 into deionized water in a 4-liter sterile beaker, stirred manually and with a stir bar for 5 min before the slurry was filtered through two layers of cheese cloth in a Buchner funnel, and then collected in 4-liter flask. The extract was transferred to a 20-liter carboy (Nalgene, Rochester, NY), where an equal volume of deionized water was added prior to autoclaving for 1 h at 121°C, and the resulting sterile PLE was stored at 4°C until use.

Strains and culture conditions used.

Three rifampin-resistant (Rifr) nonpathogenic E. coli strains (TVS 353, 354, and 355, referred to here as gEc) and two Rifr attenuated E. coli O157:H7 strains (PTVS 154 and 155, referred to here as attO157) were provided by Trevor Suslow at the University of California Davis (43). Individual isolates were cultured from frozen stocks stored at –80°C on MacConkey agar (Neogen, Lansing, MI) supplemented with 80 μg/ml rifampin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (MACR) and incubated at 42°C for 24 h. Three to five colonies of each E. coli strain were inoculated to 200 ml of tryptic soy broth (Neogen) with 80 μg/ml rifampin (TSBR), followed by incubation at 37°C for 18 h with agitation; 200 ml of each culture was added to separate 7 liters of sterile PLE, followed by incubation at 37°C for 48 h, and then stored at 4°C for 24 h. Populations of each cultured strain were determined by plating serial dilutions in 0.1% peptone water (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) on sorbitol MacConkey agar (Neogen) with 80 μg/ml rifampin (SMACR). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 to 24 h. Populations of each individual E. coli strain used were enumerated and recorded. Specific volumes of cultures of each of the five E. coli strains in PLE stored at 4°C were added to sterile deionized water in a 20-liter carboy to yield populations of gEc and attO157 that were equal in both low and high inocula. For the low inocula, 1.67 × 103 CFU/ml of each gEc isolate or 2.5 × 103 CFU/ml of each attO157 isolate was added to sterile water to make the population of the low inoculum 1 × 104 CFU/ml. For the high inoculum, 1.67 × 105 CFU/ml of each gEc isolate or 2.5 × 105 CFU/ml of each attO157 isolate was added to sterile water to make an overall inoculum of 1 × 106 CFU/ml. The carboys were mixed by manual shaking and poured into a 13-liter battery-powered Backpack sprayer (H. D. Hudson Manufacturing Company, Chicago, IL) immediately prior to spray inoculation of 2-m2 plots.

Plot management.

Plots (2 m2) containing surface-applied animal manure were spray inoculated with 1 liter of either low or high inocula (sprayer volumes were calibrated to deliver 1 liter/2-m2 plot). Various combinations of PL, HM, DMS, DML, and UN (manure amendments) were used in various seasons at the three sites. After application of the inoculum to field plots, two different depths (surface [S] and tilled [T]) were examined. For surface-amended plots, inoculated manure-amended soil was removed for microbial analysis. For the tilled (T) plots, two adjacent 2-m2 (4- by 1-m) plots were inoculated simultaneously. One-half of the plot (2 m2) was left surface amended, and the other was tilled using a rototiller (Honda F220; American Honda Motor Co., Alpharetta, GA) to a depth of 10 cm. At the BARC site, two types of soil management were used: conventionally (C) and organically (O) managed plots.

Microbial analysis.

For microbial analysis of inoculated manure-amended or unamended plots, soil samples were taken on 0, 1, 3, 7, 14, 28, 56, 90, 120, and 150 days postinoculation (dpi) or until quantitative populations of gEc and attO157 fell below the MPN detection limit (see below). For all studies, surface (S) samples were collected by inverting a round metal drying tin (7-cm diameter by 4-cm depth) into the soil surface at a depth of 1 cm, demarcating the sample (which included both soil and the manure amendment) in the container, and then using a sanitized plastic spoon or the tin itself to transfer soil/manure to a 710-ml Whirl-Pak sampling bags (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI). On each day of microbial analysis, soil from five different locations from each inoculated 2-m2 plot were combined into one sampling bag. Plastic color-coded stakes were placed at the site of collection to prevent resampling at the same site in plots over the duration of the field study. From this composite field sample, 30 g was weighed and then transferred to filtered Whirl-Pak bags (Nasco), to which 120 ml of buffered peptone water (BPW; Neogen, Lansing, MI) was added (1:5 dilution), and bags were manually mixed for 1 min. The filtered homogenate was either serially diluted in sterile 0.1% peptone water (Becton Dickinson) or directly plated (50 μl, in duplicate) onto SMACR. Homogenates or serial dilutions were spiral plated (WASP2; Don Whitley, Frederick MD), and plates were incubated at 42°C for 24 h. In some instances, 1 ml of homogenates were spread plated on four SMACR plates (0.25 ml/plate) to increase the detection limit of the direct plating assay. After 24 h, gEc (sorbitol-positive) colonies and attO157 (sorbitol-negative) colonies were counted and recorded. When colony counts from spread-plated samples on SMACR fell below the detection limit (0.7 log CFU/g), a mini-most probable number (mini-MPN) method was used for quantitative determination of gEc and attO157 populations. Homogenates (1 ml) were then diluted to 1:2 in 2× TSBR in a 48-deep-well plate (VWR, Radnor, PA) and then serially diluted to 1:10 in 1.8 ml 1× TSBR. Each dilution was replicated eight times. Deep-well plates containing MPN dilutions were incubated at 42°C for 24 h, after which 2-μl aliquots from each well were streaked onto ChromagarO157 (DRG International, Springfield, NJ) supplemented with 80 μg/ml rifampin to determine the presence of gEc or attO157. The detection limit for MPN assay was –0.24 log MPN/gdw. When gEc and attO157 populations fell below the mini-MPN detection limit, bag enrichment was performed by incubating the original 1:5 homogenates of soil/BPW at 37°C for 24 h and then isolating 2-μl portions of the homogenates on to SMACR to determine the presence or absence of gEc and attO157. The detection limit for the bag enrichment was –0.52 log CFU/gdw.

For direct plating and MPN analyses, population values in soil were calculated on a dry-weight basis from 5 g of manure-amended soil. Soil samples were weighed and then placed in a drying oven (105°C) overnight to determine dry weights, represented as CFU/gdw or MPN/gdw. Populations were then log10 transformed before statistical analysis. Four replicate plots of each manure treatment in each field trial were used.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses consisted of a two-stage process. First, the replicate field plot data (see the supplemental material, raw data supplement: nonlinear models) were used to obtain a nonlinear regression model specific to each observed experimental condition that accurately predicted and characterized gEc and attO157 survival, relative to the dpi. Subsequently, predictions from the nonlinear regression models were used to examine influence of environmental and agricultural field factors on the survival of gEc and attO157.

To characterize the survival of gEc and attO157, a total of 162 profiles (environments and agricultural field conditions) of gEc and attO157 were observed in this study, defined by combinations of the experimental factors: site, year, season, inoculum level, amendment, management, and depth. For each of the 162 profiles, gEc and attO157 were measured on soil samples taken from (at least) duplicate field plots at 0, 1, 3, 7, 14, 28, 56, 90, 120, and 150 dpi or until quantitative populations of gEc and attO157 fell below the quantitative plate detection limit or the MPN detection limit. Measurements from subsamples obtained from the same field plot at the same time occurred in 40 field plots and were averaged for the parameters log10(gEc), log10(attO157), bag-enriched gEc, bag-enriched attO157, and moisture values, yielding 6,659 data observations. gEc and attO157 values were replaced with bag enrichment (MPN/g) values when available. Because values were observed in the range of 0.30 CFU/gdw ≤ gEc and attO157 CFU/gdw ≤ 1 CFU/gdw, 1 was added to all gEc and attO157 CFU/gdw values to ensure that all log10(gEc+1) and log10(attO157 + 1) values were >0 and to allow the use of nonlinear survival models, which are asymptotic at zero (44).

Based on visual examination of the 324 graphs of log10(gEc + 1) and log10(attO157 + 1) versus dpi (see data sets in the supplemental material), six candidate nonlinear regression models were identified as a necessary and sufficient set of models to accurately describe the observed survival trends. All six candidate models were fit to the observed log10(gEc+1) and log10(attO157 + 1) data for all 162 profiles. Graphs of model residuals and of the fitted models overlaid onto observed data values were visually examined to select which one of the six candidate models best fit the relationship for each profile (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The model chosen for each profile provided: (i) an accurate prediction of log10(gEc+1) and log10(attO157 + 1) (and associated variability) at any dpi within the observed dpi range and (ii) an estimate of dpi100mort, defined as the shortest dpi at which the model’s prediction of log10(gEc+1) or log10(attO157 + 1) dropped and remained below the threshold [i.e., log10(0.30 + 1) = 0.11] (see data sets in the supplemental material [mpss, raw data supplement, and dpi100mort). For profiles with log10(gEc+1) or log10(attO157 + 1) remaining above the threshold for the entire observed range of dpi, the dpi100mort value was set to 220 days (the maximum dpi observed for any profile).

To examine effects of field management conditions, weather, and both the spatial (site) and temporal (year and season) aspects of field location on survival of gEc and attO157 (as measured by the dpi100mort), it was necessary to estimate the variability associated with each profile’s dpi100mort prediction. The primary action to begin this second stage of the statistical analysis process was to obtain resampled (45, 46) estimates (i.e., pseudoreplicates) of each profile’s dpi100mort. Each pseudoreplicate was obtained by (i) resampling (with replacement) the ni replicate values of log10(gEc+1) or log10(attO157 + 1) observed at dpi = i to obtain a resampled set of ni replicate log10(gEc+1) or log10(attO157 + 1) values at dpi = i, and by doing this for all dpi at which log10(gEc+1) and log10(attO157 + 1) values were measured, and then (ii) refit the profile’s chosen nolinear regression model to this instance of the profile’s resampled data (across all observed dpi), and use the resulting model to predict one pseudoreplicate estimate of dpi100mort. This process was repeated to obtain either one pseudoreplicate estimate of dpi100mort for each replicate of initial soil moisture content observed for the profile or a minimum of four pseudoreplicate estimates. Weather covariates, each having only 12 unique values (one value for each observed site, year, and season), were also merged into this consolidated data set for use in conducting analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to examine the effect of each experimental (environmental and agricultural) factor on gEc and attO157 survival. All ANOVA and ANCOVA models examined the relationship between dpi100mort and combinations of the agricultural field factors, weather, and the spatial and temporal field location factors.

In ANOVA and ANCOVA models, the agricultural field factors were examined in a nested structure, indicating that all levels of each factor were not combined with all levels of all other factors. Therefore, each treatment effect is said to be “nested within” levels of the other treatment factors in a hierarchical manner. The hierarchy of factors is as follows, with the nested factor listed before the parentheses: site, season (site), inoculum level × season (site), manure amendment (site, season, and inoculum level), management (site, season, inoculum level, and amendment), and depth (site, season, inoculum level, manure amendment, and management).

To estimate the proportion of dpi100mort variability (R2) explainable by specific combinations of (i) agricultural field factors, (ii) spatial and temporal aspects of field location (i.e., site, year, and season), and/or (iii) weather variables. The consolidated data set was used to fit several ANCOVA models (Table 2). The weather variables (daily rainfall averages and maxima; and daily temperature averages, minima and maxima) (see data sets in the supplemental material [BARC PA UMES daily temp]) and the initial soil moisture content (data sets in the supplemental material [raw data supplement and initial soil moisture]) were included in the ANCOVA models as linear regressors (i.e., covariates). Because dpi100mort values were a measure of time duration, the ANCOVA models were specified, using SAS Proc GLIMMIX, to be generalized linear mixed-effects models with a gamma distribution and a log link function (47, 48). The R2 statistic of each ANCOVA model was calculated as R2 = 1 – exp[–2(LLANCOVA – LL0)/N], where LLANCOVA and LL0 are the log likelihood values for the ANCOVA model and the intercept-only model, and N is the total number of data values used to fit each model (49). Because generalized linear models cannot capture sampling variance (i.e., R2 will not reach 100%), the R2 statistic calculated for each ANCOVA model was corrected to represent proportion of explainable (i.e., nonsampling) variance by dividing it by the R2 for the ANCOVA (i.e., saturated) model containing all nonconfounded model effects.

To estimate the variability in dpi100mort (i.e., variance component) associated with each individual agricultural field, location, and weather factor, a random-effects ANOVA model was specified. Because weather and location factors shared some (i.e., confounded) variability, two separate ANOVA models were specified: (i) weather + agricultural field factors and (ii) location (site/year/season) + agricultural field factors (Table 3). Normal distribution properties of random-effects models allowed 100% of variability present in the observed data to be characterized by ANOVA, capturing any variability associated with effects not explicitly specified in the model in the residual variance component.

To identify combinations of factors most important in facilitating accurate prediction of dpi100mort, the randomForest R package (50, 51; H. Pang, A. Mokhtari, Y. Chen, D. Oryang, D. T. Ingram, and J. V. Van Doren, unpublished data) was used to fit random forest models separately to gEc and attO157 data (Fig. 2). Independent variables specified in the random forest models were (i) a factor whose unique levels were the combinations of all observed levels of the four agricultural field factors (i.e., “Inoc.Amend.Mgmt.Depth”); (ii) four different factors whose unique levels were combinations of the levels of three of the four agricultural field factors (i.e., Inoc.Amend.Mgmt, Inoc.Amend.Depth, Inoc.Mgmt.Depth, and Amend.Mgmt.Dept); (iii) six different factors whose unique levels were combinations of the levels of two of the four agricultural field factors (i.e., Inoc.Amend, Inoc.Mgmt, Inoc.Depth, Amend.Mgmt, Amend.Depth, and Mgmt.Depth); (iv) combinations of site, year, and seasons factors (i.e., Year.Season and Site.Year.Season); and (v) all individual factors (site, year, season, inoculum, amendment, management, depth, and initial soil moisture) and the average, minimum, maximum, and range of daily temperatures and of daily rainfall. Seventy percent of the dpi100mort data values were randomly chosen to train the random forest models, and the remaining 30% of the dpi100mort values were used to assess the models’ fit.