Abstract

The subxiphoid approach to video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) has been introduced as an alternative to intercostal VATS. There is some evidence that avoiding intercostal incision and instrumentation leads to reduced pain and facilitates early mobilisation and enhanced recovery. Access of the pleural cavities and anterior mediastinal space through a subxiphoid incision presents some challenges, particularly when accessing posterior pulmonary lesions. With increasing experience, a large range of thoracic surgical operations performed through the subxiphoid approach have been reported including anatomical segmentectomies, thymectomies. Another attraction is that bilateral procedures can be performed through a single incision. The experience of several surgeons passing through the learning curve of subxiphoid VATS surgery has resulted in overcoming many of the early challenges faced. In this paper, a series of tips and tricks are presented to enable surgeons considering adopting this technique into their practice to do so safely and with an appreciation of the difficulties that they may face.

Keywords: Subxiphoid, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), learning curve, training

Introduction

The uniportal subxiphoid video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (SVATS) technique is becoming established as an alternative approach to performing thoracic surgery without making an incision in the intercostal spaces. There are now reports describing use of SVATS across a wide range of thoracic surgical procedures including thymectomy, metastasectomy, pneumothorax surgery and anatomical lung resections including lobectomy and segmentectomy (1-4). With experience and passing through the learning curve there have been modifications made to the technique through the experience of many surgeons and development of new instruments (1,4-7). This evolution has enabled SVATS to become faster, easier and more feasible even in some previously challenging conditions (6,7).

The aim of this paper is to present some tips and tricks starting from patient selection, going through surgical details and ending with postoperative care to provide a guide to thoracic surgeons interested in introducing the subxiphoid VATS approach into their practice in a safe and efficient manner.

General principles

Previous uniportal VATS experience and a good assistant

SVATS could be considered a modified version of the uniportal intercostal VATS technique as there are some similarities. However, there are important differences that introduce challenges that should be appreciated before embarking on SVATS techniques.

In particular, the subxiphoid access port restricts the range of motion that can be achieved with standard VATS instruments, and advanced bimanual dexterity is required of the operating surgeon. Furthermore, the different caudal-cranial and anterior to posterior views makes the view of the anatomical structures slightly different to that experienced in uniportal intercostal VATS requiring a very good knowledge of the three-dimensional anatomy of the hilar structures (3,8). Having said that, it is easy to appreciate that having previous experience with uniportal intercostal VATS will make the learning curve of SVATS much easier to climb.

It is advisable for surgeons to start working under the supervision of skilled surgeon in SVATS as a mentor, and to begin with minor surgeries like straightforward wedge pulmonary resections and thymectomies. After gaining more confidence and experience, moving to more complex procedures such as lobectomies then segmentectomies will be more straightforward (6).

It is also important to emphasise that presence of an experienced assistant is vital for success with SVATS. The assistant’s movement should be fully coordinated with the surgeon to view difficult angles specially at apical arterial trunks and posterior mediastinal structures. Having a full understanding of using a 30° operating telescope is essential to achieve the visualization necessary for SVATS procedures. It is important for the assistant to withdraw the camera each time a new instrument is introduced into the surgical field to ensure this is performed under vision to avoid inadvertent injury—especially to the heart in left sided procedures (7).

Case selection

Despite increasing popularity of SVATS approach in various thoracic surgical procedures, case selection is still a crucial prerequisite for a successful operation specially at the start of learning curve (4,6). Preoperative discussion should be held by the surgical team to select patients most suitable for the SVATS approach. It is advisable to follow the following inclusion and exclusion criteria that could be loosened after gaining experience and with progression of learning curve (6,7,9).

Inclusion criteria:

❖ for major lung resection, it is advisable to include only cases with lesions of T1 or T2 status of tumour <7 cm for lobectomy and lesions <2 cm for segmentectomy;

❖ N0 status for tumour;

❖ localized infectious lung disease;

Exclusion criteria:

❖ central masses;

❖ enlarged lymph nodes with confirmed N1 or N2 disease;

❖ chest wall involvement;

❖ previous thoracic surgery (reoperation);

❖ cardiomyopathy or impaired cardiac function;

❖ obese patients with body mass index <30 kg/m2 who may show difficulty in localization of xiphoid process in addition to the abundant pericardial and pleural fat which makes access to pleural space more difficult and time consuming (4,10).

One of the limitations of the SVATS approach, particularly during early experience, is difficult access to posterior lesions (8) which require traction and experience to accomplish. So, it is better in the early experience not to select cases with posterior lesions that require either unilateral or synchronous wedge resection or segmentectomy. Careful examination of preoperative chest imaging is mandatory to localize the lesion accurately.

The subxiphoid approach is more difficult on the left side due to the cardiac pulsation with risk of intraoperative arrhythmia (4). So, it is better to omit left-side operations for patients with cardiac diseases, such as cardiomegaly and arrhythmia (6). In addition to routine preoperative investigations, preoperative echocardiogram (ECHO) evaluation and cardiac assessment are advised to exclude cardiac problems that preclude safe subxiphoid approach.

Invasive thymoma is less likely to be operated through SVATS in the early experience (1).

Instruments

With increasing demand for the subxiphoid approach along with the strong desire to make it feasible and easier, special self-made instruments for SVATS (Shanghai Medical Instruments Group Ltd., Shanghai, China) were designed to overcome the relatively longer track and different axis of the subxiphoid approach compared with the intercostal one. Those instruments are with double joints, longer, harder with a more curved tip. They include lung graspers, dissectors, stapler guider, electrocautery blades and others (Figure 1) (4,6,11).

Figure 1.

Instruments designed for SVATS (Shanghai Medical Instruments Group) (http://www.jzsf.com/en/index.aspx). SVATS, subxiphoid video-assisted thoracic surgery.

The instruments with their specific angles have helped in reducing instrument interference, reducing cardiac compression, whilst providing easier and more comfortable exposure, dissection and cauterization of tissues. Also, use of curved tip staplers facilitates easier division of different structures during the procedure (4,6,7,9,11). A thoracoscope which can provide a variable range of view could also help to examine the posterior aspect of the lung for posterior mediastinal lesions and lymph node (3).

General operative set up

One monitor is placed cranially above the head of the patient. The surgeon and the scrub nurse stand on either sides in case of supine position of the patient and on the abdominal side of the patient in case of the patient lying in the lateral decubitus position with the assistant standing opposite. A 10-mm, 30-degree angled high-definition video thoracoscope (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) is used. Usual VATS instruments plus the dedicated instruments specially designed for SVATS are used during the operations.

Anaesthesia

All cases are performed under general anaesthesia with double lumen tube. Alternating single lung ventilation is conducted in case of synchronous lesions. In case of subxiphoid thymectomy, injury and clamping of left brachiocephalic vein is a possible complication. So, it is advisable to initiate peripheral infusion in the right hand or foot to allow clamping of left brachiocephalic vein if it is injured (12).

Positioning of the patients

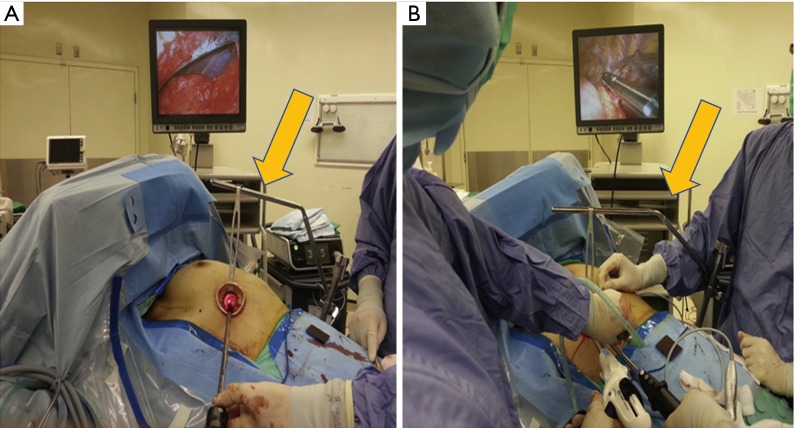

Positioning of the patients varies according to the site and laterality of the lesion. In the case of mediastinal, bilateral lesions or concomitant mediastinal and pulmonary lesions, it’s preferred to put the patient in the supine position with both upper limbs adducted beside the patient (3). Alternative 30° up tilting of the operated side may help getting more space and improving ergonomics to provide the surgeon more comfort in case of synchronous lesions (3). Some surgeons prefer to put small soft roll between the two scapula or use a sternal elevator (Figure 2) (13) to elevate the sternum to get more space during the procedure (1,13).

Figure 2.

Patient positioned lateral decubitus position with use of a sternal elevator (yellow arrow).

In case of unilateral pulmonary lesion, the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with 30° backward inclination (Figure 3) (9) and the patient should be secured to the table to prevent a fall.

Figure 3.

Example of patient in lateral decubitus position with 30° backward inclination.

Although the supine position gives one access in case of bilateral or concomitant mediastinal and pulmonary lesions, some surgeons prefer to operate in the lateral decubitus position and change the patient’s position intraoperatively according to the operated lesion with new sterile drapes, i.e., placing the patient in alternating decubitus positions with 30° backward tilting in case of bilateral lesions (11) or alternating supine and decubitus positions in case of concomitant mediastinal and pulmonary lesions respectively (6).

The 30° posterior inclination in case of lateral decubitus position helps to displace the lung posteriorly giving a clearer view of the hilum, more space for instruments with less interference between them and the heart particularly on the left side. Moreover, it gives the surgeon’s hand more space to move and handle the instruments freely. We have noticed also that 30° backward inclination provides better ergonomics for the surgeon’s wrist as it makes hilar and fissural structures come at right angle when using the long curved tipped SVATS instruments which facilitates dissection with less effort (7).

Before deciding on the patients position to be used, the surgeon should review the preoperative imaging, particularly looking at the position of lesions requiring localised resections like small blebs or nodules. Posteriorly located lesions may be difficult to access in the supine position that may direct the surgeon to operate in the lateral decubitus position even if the patient has bilateral lesions for example.

The surgeon should also consider the possibility of unpredicted difficulty or complication like bleeding that require shifting the procedure to classic lateral approach or even conversion to thoracotomy. So, in case of operating upon bilateral pulmonary lesions and putting the patient in supine position, it is advisable to suspend both arms up in arm sling fixed to the operating table to keep arms away from lateral chest wall and to allow fast turning of the table into decubitus position to make the set immediately ready for lateral approach or thoracotomy without need to take off the sterile drape to reposition the arm. Also, the operative field should be sterilized widely to allow conversion to uniportal, multiple port approaches or thoracotomy once needed. In case of bleeding during thymectomy, extension of the subxiphoid incision into sternotomy is fast without need to change patient’s position.

General surgical technique

Incision

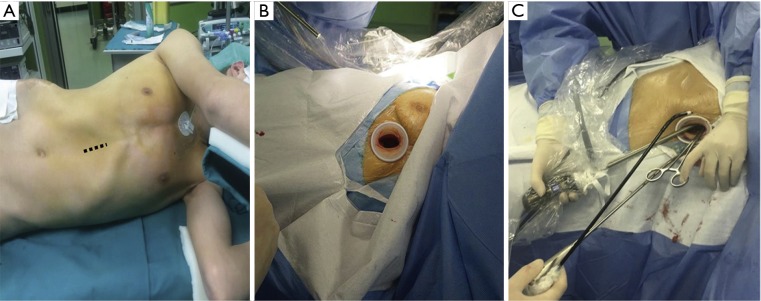

A 3–4 cm longitudinal incision is made extending from the xiphisternal junction to 1 cm below the xiphoid process (Figure 4A) (6). The subcutaneous tissue is dissected then the rectus abdominis muscle is exposed and its fibers dissected longitudinally to expose the xiphoid process that is completely resected to provide a widened operative access and to facilitate the instrumentation during the surgery. By index finger dissection, a retrosternal tunnel is created above the diaphragm with moving the index finger more toward the operated side in a trial to make a retrosternal space or to open the required pleura bluntly. A wound protector (Chinese Manufacture wound protector, Changzhou, China) (Figure 4B) (6) is inserted giving more space for the camera and instruments and even lessen the need for sternal lifter (8).

Figure 4.

Intraoperative photos demonstrating (A) the patient positioned in lateral decubitus position with black dashes indicate position of incision (B) subxiphoid port with wound protector; (C) arrangement of instruments through wound protector.

Some surgeons prefer to perform a transverse incision, particularly in the case of operating in supine position for bilateral lesions or concomitant mediastinal and pulmonary lesions (14). The transverse incision is made at the level of xiphoid process between the two costal margins.

In our early experience we operated via a transverse incision if the infrasternal angle was ≥70° or via a vertical incision if the infrasternal angle was <70° (6,9). Now, a vertical subxiphoid incision is currently made routinely in almost all cases regardless the degree of infrasternal angle or bilaterality of the lesion. With time, it has been thought that a vertical incision with its upper end at the xiphi-sternal junction make the working port nearer to the hilum. In addition, the vertical incision goes with the same underlying dissected longitudinal planes of subcutaneous tissue, rectus muscle fibers and xiphoid process minimizing the degree of tissue trauma and giving an even and wider retraction by the wound retractor. As the incision is totally above the diaphragm, abdominal herniation is unlikely (7).

After the incision has been made, a 10-mm, 30° video thoracoscope is placed on the caudal side of the incision with the assistant holding the camera and pressing the camera slightly against the lower costal margin using it as a fulcrum. VATS instruments are placed from the cranial side of the incision (Figure 4C) (6). In case of transverse incision, the camera is placed in the angle toward the assistant’s side.

The pericardio-phrenic fat is removed which facilitates passage of instruments and staplers into the correct space. In case of pulmonary lesion, the pleura of the operated side is opened under thoracoscopic visualization. The pleural cavity is evaluated for unexpected pathology and the site of the lesion is confirmed. Working on mediastinal disease requires creation of a retrosternal space followed by introduction of the video scope and instruments to accomplish the job. This may be facilitated with the use of a sternal elevator as discussed above.

Individual surgical techniques

Lung resection: lobectomy and segmentectomy

The subxiphoid approach is considered convenient for performing lobectomy and segmentectomy particularly in the upper and middle lobes. It has the advantage of more convenient angles during introduction of staplers than the intercostal approach to these lobes. On the other hand, limited vision for lower lobes near the diaphragm, compression of the heart during left-sided operations and difficult access to posteriorly located lesions make the subxiphoid technique more challenging for those conditions (6,10).

Surgical steps

After entering the pleural cavity, the interlobar fissural status is assessed, upon which the approach towards the lobectomy is determined. The lung is retracted using specially designed long curved lung grasper held by the assistant and dissection is carried out by the surgeon using a suction instrument in their left hand and a long curved laparoscopic hook, electrocautery or 5 mm blunt tip LigaSure of 37 mm length (Covidien Ltd., Dublin, Ireland) in the right hand (7). Use of a long sucker with distal curvature can be beneficial to slightly retract the pericardium medially in order to optimize visualization, being careful not to disturb the cardiac function or venous return (6).

As usual, the order of stapling the artery first, vein then bronchus is followed. If the fissure is well developed, the surgeon should try to open it early to delineate the vascular anatomy, but if not well developed, the fissure could be left as the last step or follow the fissureless technique by stapling the interlobar arteries and fissure last.

The vessels, bronchus and fissures are exposed and divided with appropriate straight or articulated endostaplers. In some cases, a curved-tip stapler technology is used to facilitate the passage around the structures. To transect minor pulmonary arteries, usage of proximal and distal silk ligature or polymer clips (Click’a V® Endoscopic Polymer Clip Appliers 45°, Grena Ltd., Brentford, UK) then resection in between with LigaSure is a satisfactory alternative. A specimen pouch Endo Catch bag 10 mm (Covidien Ltd.) is used to remove the specimen, with prior removal of the wound protector.

The order of dissection and division of pulmonary vessels and bronchi had been followed classically by starting with the artery, vein then the bronchus particularly at the start of learning curve associated with precise selection of straightforward cases with classic anatomy and minimal or no adhesions. With experience, there has been acceptance of operating more challenging cases with more advanced adhesions or anatomical variations requiring the surgeon to follow the role of “whatever easy comes first”, making the surgeon no longer stick to a specific order in all cases including sometimes the fissureless technique the same as in intercostal approach (7,15).

Regarding segmentectomy, it was previously thought that posterior segments (S2, S6, S9, and S10) would not be accessible by SVATS (16). But, with increasing experience and familiarity to the approach in addition to development of specific SVATS instruments, surgeons started to perform all those previously challenging segmentectomies safely by subxiphoid approach. However, to reach to that point of proficiency, surgeons should first develop their learning curve in standard uniportal lung resection then move to performing SVATS segmentectomies of the more accessible and easy segments before attempting those challenging posteriorly located segmentectomies (6).

Anatomical thoracoscopic segmentectomy needs accurate demarcation of the inflation-deflation line in order to perform precise segmentectomy. In addition to the classic manoeuvre of differential inflation of the preserved segments around the desired segment to be resected after clamping the potential feeding bronchus to the resected segment, we use another innovative open insufflation technique during lung collapse. The technique includes accurate localization of the feeding bronchiole to the segment to be resected, proximal ligation by silk suture just after it’s take off from the lobar bronchus, creation of minute hole in the distal part of its membranous wall and insertion of small pore central venous catheter and insufflation of 30–40 mL of air slowly that allows inflation of the segment and delineation of intersegmental plan. Before air pushing, the surgeon should aspirate first to be sure that the tip of the catheter is outside a blood vessel not to cause air embolism.

In all indicated cases, systemic lymph node dissection of at least three N2 lymph nodes stations can be performed according to the IASLC/mountain classification. With early experience, surgeons can experience some difficulty in accessing particularly the posteriorly located subcarinal lymph nodes. Dissection of the posteriorly located subcarinal lymph nodes requires maintained anterior traction of the lung by a lung gasper held by the assistant along with simultaneous dissection by the surgeon. Tilting the patient more toward the lateral position while working posteriorly may facilitate more access to the posterior lesions and lymph nodes. With more experience and adjustment to using the special long curved instrument set, surgeons started to get more comfortable with lymph nodes dissection, including the subcarinal lymph nodes. Usage of energy sealing devices in lymph node dissection is preferred as it helps with extracapsular dissection along with ensuring optimum haemostasis (7,9).

After completion of the procedure, the bronchial stump is checked under water for air leak. In the subxiphoid approach, it is difficult to flood the surgical field with water to test air leak by the usual manner as the wound through which you pour the water is lower than the surgical field and not as high as that of lateral approach leading to getting the water back out of the incision or inability to fill the surgical field adequately. That is why a special metal pot with long nozzle was designed to deliver the water from outside the wound to deep inside the surgical field making that mission easy and feasible (Figure 5) (6,9).

Figure 5.

Specially designed metal pot with long nozzle to deliver the water inside the surgical field to check air leak (Shanghai Medical Instruments Group) (http://www.jzsf.com/en/index.aspx).

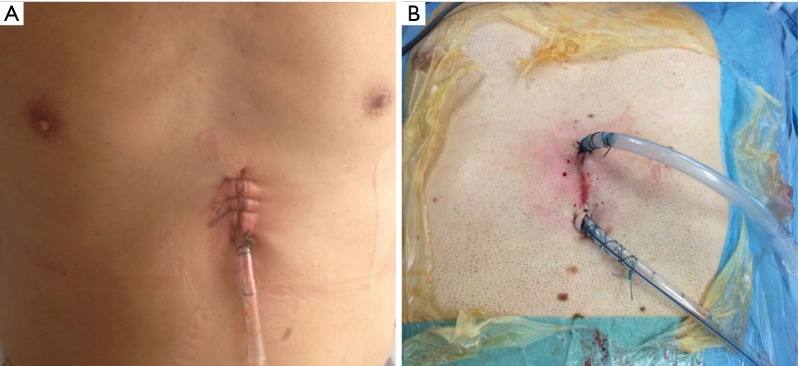

Wound closure and drainage

At the end of the procedure, a 28Fr pleural drainage tube is inserted at the inferior end of the incision passing laterally to the thoracic apex, and then connected to a drainage bottle (Figure 6A). A deep venous puncture catheter is inserted at the 8th intercostal space on the lateral chest wall then connected to a drainage bag as a basal drain. An additional drainage tube is inserted in the other end of the incision in patients with concomitant mediastinal lesion, bilateral lesions or associated opening of the pleura during thymectomy (Figure 6B). Only one drain is inserted on one side of the incision in case of isolated mediastinal lesion. The incision is closed in layers. All patients are extubated on table.

Figure 6.

Position of drains postoperatively (A) drain is positioned at the inferior end of the incision in case of unilateral or isolated mediastinal lesion, and (B) 2 drains are positioned at both sides of the incision in case of concomitant mediastinal lesions, bilateral lesions or associated opening of the pleura during thymectomy.

Thymectomy

As usual, selection of cases is an important step for a successful procedure especially in the early experience. It is better to avoid cases with large or invasive tumours. Also, cardiomegaly, poor cardiac function or preoperative arrhythmia are high risk factors for poor intraoperative access, arrhythmia or cardiovascular instability as a result of instrumentation over the heart or the left hemithorax (1).

Some authors advise surgeons adopting SVATS thymectomy for the first time to start with performing subxiphoid dual-port thymectomy through insertion of a subxiphoid port initially and then adding a 5-mm port into the left, right, or bilateral fifth intercostal space(s) after dissection of mediastinal pleura and opening of the thoracic cavity. The additional intercostal port reduces interference between surgical instruments and improves surgical operability. Then, by getting more familiar with the view and technique, the additional lateral port can be omitted (17).

Surgical steps

After following the same previous general surgical technique and creating a retrosternal tunnel by blunt finger dissection, a wound protector is placed to allow suitable primary positioning of telescope and instruments. The surgeon holds a bent-tip grasping forceps specially designed for the subxiphoid approach in the left hand for tissue grasping and elevation and 5 mm LigaSure Maryland type (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) vessel sealing device or bent-tip endoscopic electrocautery in the right hand for dissection (1).

The subxiphoid approach gives the advantage of good visualization of both phrenic nerves (18). It’s advisable to start the procedure with bilateral opening of both mediastinal pleurae that makes the mediastinum drop dorsally giving more space for the surgical field and wide panoramic view between the two phrenic nerves (19). Then, all mediastinal fat is dissected up from the pericardium guiding the surgeon to underneath the thymus. Dissection of the thymus off the pericardium should go from the caudal to cranial direction and from right to left phrenic nerves till reaching the left brachiocephalic vein superiorly. Complete freeing of the thymus gland till the left brachiocephalic vein helps traction of the right lobe to the left and the left lobe to the right to help dissection of the thymus off the right and left halves of the left brachiocephalic vein respectively as well as dissection and downward traction of thymic horns (20). It is important to ensure complete haemostasis of the most cranial tip of thymic horns by LigaSure during separation of thyro-thymic connection while pulling down of thymic horns.

Lateral traction of the thymus gland makes the thymic tributaries more clearly visualised from the caudal view of the subxiphoid approach. They are mostly 2–4 in number, but anatomical variations are frequent and should be considered. Good circumferential dissection around thymic tributaries with subsequent distal clipping (towards left brachiocephalic vein) and proximal cutting by LigaSure (towards thymus gland) ensures good haemostasis and avoids accidental bleeding.

Use of the curved tip of LigaSure is very helpful in dissection of the thymic tissue off the pericardium and left brachiocephalic vein. Holding the convex surface of the LigaSure jaws during dissection facing towards vital structures like left brachiocephalic vein, phrenic nerve and pericardium helps to get cleaner dissection and to prevent injury to these structures. It is crucial not to hold, coagulate or cut any structure without clear vision.

How to deal with bleeding during thymectomy

Bleeding from left brachiocephalic vein is a common complication during thoracoscopic thymectomy. The first step to deal with bleeding is to apply pressure with a gauze piece for 10 minutes which can be changed again by another one for a further 10 minutes if the first one doesn’t stop the bleeding (21). Most bleeding cases are managed by compression in such way, but if it does not work, application of a ligaclip or placing a suture at the bleeding point may be required.

The main problem with the subxiphoid access is that the axis of the working instrument is perpendicular to the axis of left brachiocephalic vein making it difficult to deal with the bleeding. Sometimes, insertion of an extra right or left intercostal 10 mm port may help introduction of a clip applier or needle holder in an axis semi parallel to left brachiocephalic vein making it easier to deal with the bleeding. Of course, extension of the subxiphoid incision into sternotomy should be considered urgently in case of massive bleeding or failure of surgical control of the problem.

Bilateral lesions

Bilateral wedge resection may be performed in patients with bilateral lung tumours or bilateral pneumothorax. Most common pitfalls in bilateral procedures are accessing posteriorly located lesions and lesions in the lower lobes and cardiac compression especially upon operating on the left side. So, careful examination of the preoperative imaging is crucial to localize the lesion precisely. Try to avoid cases with posteriorly located lesions in early experience. Also, selection of thin, young patients with no cardiac morbidity will ease the technique and lessen the incidence of cardiac complications.

Fortunately, most blebs or bullae are found in the apex of the upper lobes or superior segment of lower lobes. These locations can be easily seen and approached via the subxiphoid technique taking into consideration that back of the superior segment of upper lobes should be visualized carefully for any blebs. Additionally, patients with primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) are mostly slim and young with normal size of the heart. The heart can be less compressed, and intraoperative arrhythmia, even if it occurs, it might be better tolerated by those young and otherwise healthy patients (3).

Tilting the surgical table towards dead lateral position along with anterior traction of the lung facilitates the access and resection of posteriorly located lesions. Because intraoperative palpation is not possible as in the lateral thoracic VATS approach, hook wire marking will be helpful when resecting pulmonary nodules unless the mass is not directly beneath the pleura and near to the subxiphoid incision (22).

An important tip in order to shorten the operative time in case of bilateral lesions, is to operate while the patient in supine position with alternative upward 30° tilting of the operated side without need to change patient’s position in alternate decubitus positions (23). Also, SVATS can apply the same role in case of concomitant resection of anterior mediastinal masses and lung pathologies (19).

Bleeding, adhesions, conversion to uniportal lateral VATS approach

Sometimes in case of bleeding, extensive adhesions or technical difficulty, the surgeon may need to convert to intercostal approach through adding an intercostal incision at the 5th intercostal space between anterior and mid axillary lines which is then converted to anterior thoracotomy if needed. It is not helpful to extend the subxiphoid wound for major bleeding control except in thymectomy (5,8).

Management of bleeding generally starts as usual by compression, then attempt to control by placing a stitch or by clipping then conversion to thoracotomy if failure to control. With better instrumentation and experience, incidence of accidental intraoperative bleeding should decrease with more ability to control through SVATS if it occurs (7). Anyway, previously mentioned precautions during positioning in case of bleeding should be considered.

Left sided lesions

Cardiac compression and arrhythmia are challenges in left sided operations. Improved handling skills, backward tilting of the patient, longer and specially curved instruments making the concave edge of the instruments toward the heart during the operation have enabled surgeons to make better retraction and dissection of pulmonary structures with lesser compression on the heart. Some surgeons prefer usage of sternal elevators to increase the working space with subsequent reduction in instruments-heart interference (24).

Postoperative care

Postoperatively, all patients are requested to mobilize early and perform aggressive physiotherapy. It is recognised that the SVATS approach can lead to reduced postoperative pain than with intercostal VATS procedures (24,25) which helps with early mobilization, effective physiotherapy and better ability to get clear chest secretion and therefore reduced length of hospital stay (5).

Postoperative pain is managed using a patient-controlled analgesia pump, as required, with sufentanil citrate 1 mL: 50 µg, and regular medication with flurbiprofen 50 mg every 6 hours, alternating with paracetamol 1 g every 6 hours. Drains are removed when there is no air-leakage and fluid drainage less than 300 cc in 24 hours. Patients are usually discharged 1 day after tube removal and followed up at outpatient clinic as per scheduled.

Summary

The use of the subxiphoid VATS approach has been increasing over the past few years. Case selection should be taken seriously into consideration especially at the start of learning curve. Growing adoption of SVATS by many surgeons has contributed to evolution of the surgical technique with many tips and tricks that make the procedure easier and more feasible. With growing experience and following those tips and tricks, many previously addressed challenges have been overcome.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Weaver H, Ali JM, Jiang L, et al. Uniportal subxiphoid video-assisted thoracoscopic approach for thymectomy: a case series. J Vis Surg 2017;3:169. 10.21037/jovs.2017.10.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu CC, Wang BY, Shih CS, et al. Subxyphoid single-incision thoracoscopic pulmonary metastasectomy. Thorac Cancer 2015;6:230-2. 10.1111/1759-7714.12189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu CY, Lin CS, Liu CC. Subxiphoid single-incision thoracoscopic surgery for bilateral primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Videosurgery Miniinv 2015;10:125-8. 10.5114/wiitm.2015.48572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez-Arenas LA, Guido W, Jiang L. Learning curve and subxiphoid lung resections most common technical issues. J Vis Surg 2016;2:117. 10.21037/jovs.2016.06.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez-Arenas LA, Lin L, Yang Y, et al. Initial experience in uniportal subxiphoid video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for major lung resections. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:1060-6. 10.1093/ejcts/ezw189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali J, Haiyang F, Aresu G, et al. Uniportal Subxiphoid Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Anatomical Segmentectomy: Technique and Results. Ann Thorac Surg 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z, Ali JM, Xu H, et al. Anesthesia and enhanced recovery in subxiphoid video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2018 doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.11.90. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez-Rivas D, Yang Y, Lei J, et al. Subxiphoid uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic middle lobectomy and anterior anatomic segmentectomy (S3). J Thorac Dis 2016;8:540-3. 10.21037/jtd.2016.02.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aresu G, Wu L, Lin L, et al. The Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital subxiphoid approach for lobectomies. J Vis Surg 2016;2:135. 10.21037/jovs.2016.07.09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akar FA. Subxiphoid Uniportal Approach is it Just a Trend or the Future of VATS. MOJ Surg 2017;4:00076. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aresu G, Weaver H, Wu L, et al. Uniportal subxiphoid video-assisted thoracoscopic bilateral segmentectomy for synchronous bilateral lung adenocarcinomas. J Vis Surg 2016;2:170. 10.21037/jovs.2016.11.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suda T. Subxiphoid single-port thymectomy procedure: tips and pitfalls. Mediastinum 2018;2:15 10.21037/med.2018.02.01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu CC, Wang BY, Shih CS, et al. Subxiphoid single-incision thoracoscopic left upper lobectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:3250-1. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song N, Zhao DP, Jiang L, et al. Subxiphoid uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for lobectomy: a report of 105 cases. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S251-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Rivas D, Lirio F, Sesma J, et al. Subxiphoid complex uniportal video-assisted major pulmonary resections. J Vis Surg 2017;3:93. 10.21037/jovs.2017.06.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aresu G, Weaver H, Wu L, et al. The shanghai pulmonary hospital uniportal subxiphoid approach for lung segmentectomies. J Vis Surg 2016;2:172. 10.21037/jovs.2016.11.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suda T, Ashikari S, Tochii D, et al. Dual-port thymectomy using subxiphoid approach. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;62:570-2. 10.1007/s11748-013-0337-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suda T, Kaneda S, Hachimaru A, et al. Thymectomy via a subxiphoid approach: single-port and robot-assisted. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S265-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argueta AJ, Cañas SR, Abu Akar F, et al. Subxiphoid approach for a combined right upper lobectomy and thymectomy through a single incision. J Vis Surg 2017;3:101. 10.21037/jovs.2017.06.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu L, Lin L, Liu M, et al. Subxiphoid uniportal thoracoscopic extended thymectomy. J Thorac Dis 2015;7:1658-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suda T, Hachimaru A, Tochii D, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy versus subxiphoid single-port thymectomy: initial results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49 Suppl 1:i54-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suda T. Subxiphoid Uniportal Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery Procedure. Thorac Surg Clin 2017;27:381-6. 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu CH, Chao YK, Liu YH. Subxiphoid approach for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: an update. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:S1662-5. 10.21037/jtd.2018.04.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang BY, Chang YC, Chang YC, et al. Thoracoscopic surgery via a single-incision subxiphoid approach is associated with less postoperative pain than single-incision transthoracic or three-incision transthoracic approaches for spontaneous pneumothorax. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S272-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L, Tian H, Yue W, et al. Subxiphoid vs intercostal single-incision video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for spontaneous pneumothorax: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg 2016;30:99-103. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]