Abstract

Background:

Chest physiotherapy techniques, such as percussion, postural drainage, and expiratory vibrations, may be employed in a critical care setting. Physiotherapists are primarily responsible for their provision; however, nurses have also traditionally implemented these treatments. It is unclear whether nurses consider chest physiotherapy to be a part of their role, or how they perceive their knowledge and confidence pertaining to these techniques.

Objective:

To investigate the attitudes of nurses towards traditional chest physiotherapy techniques.

Method:

A total of 1222 members of the Australian College of Critical Care Nurses were invited to participate in an anonymous online survey.

Results:

There were 142 respondents (12%) with the majority (n = 132, 93%) having performed chest physiotherapy techniques in clinical practice. Most of them considered that the provision of chest physiotherapy was a part of nurse's role. Commonly cited factors influencing nurses' use of chest physiotherapy techniques were the availability of physiotherapy services, adequacy of nursing staff training and skill, and perceptions of professional roles.

Conclusions:

Nurses working in critical care commonly utilised traditional chest physiotherapy techniques. Further research is required to investigate the reasons why nursing professionals might assume responsibility for the provision of chest physiotherapy techniques, and if their application of these techniques is consistent with evidence-based recommendations.

Keywords: critical care, nursing staff, physical therapy modalities, questionnaire

Introduction

Physiotherapy is an integral part of the management of people with respiratory dysfunction [1,2]. In order to address issues such as impaired alveolar ventilation and retention of pulmonary secretions, physiotherapists commonly prescribe and implement a variety of treatment techniques. Physiotherapy techniques used to treat respiratory dysfunction have traditionally included percussion, vibrations, postural drainage, deep breathing exercises, incentive spirometry, and positive expiratory pressure therapy [3,4]. Collectively, these have been referred to as ‘chest physiotherapy’ techniques.

Chest physiotherapy techniques are employed in numerous clinical settings including critical care. Critically ill intubated and mechanically ventilated patients are at a high risk of developing respiratory complications, such as pneumonia, pulmonary secretion retention, and atelectasis, due to periods of prolonged immobilisation, the presence of an artificial airway, and positive pressure mechanical ventilation [5–7]. All these factors contribute to impaired mucociliary clearance and reduced lung volume. In order to enhance secretion clearance, optimise oxygenation, improve lung compliance, and prevent further respiratory complications, physiotherapy techniques are frequently applied to this patient population [2,5,8].

Historically, chest physiotherapy techniques have been performed routinely as a prophylactic measure in the management of critically ill patients, regardless of their underlying pathophysiologic condition [9–11]. However, this has been shown to be of limited value and is, therefore, no longer recommended [2]. In recent years, there have been advancements in the evidence base regarding the use of chest physiotherapy techniques, resulting in subsequent changes in their application [4]. Physiotherapists also incorporate many other techniques, such as ventilator hyperinflation and early mobilisation, into their management of people in the critical care setting [6,12,13]. Physiotherapy professionals have adopted a more problem-based framework in which an intervention addresses the patient's problems arising from the underlying pathophysiology. Consequently, traditional chest physiotherapy techniques are now used less frequently, selectively, and only when specifically indicated. This has facilitated more individualised and targeted treatment selection, potentially contributing to optimised patient outcomes and more effective resource utilisation in critical care [5].

Although physiotherapists have been primarily responsible for the provision of chest physiotherapy techniques, other health professionals, particularly nursing staff, have also traditionally implemented these treatment modalities. As such, nurses may view chest physiotherapy delivery as a part of their role in routine respiratory care [14]. This may be, in part, due to the prior education and training nursing professionals have received in their original entry-level qualification. Alternatively, this could be due to limitations in physiotherapy service availability in the critical care setting [15]. It is possible that nursing staff have assumed the responsibility of providing ongoing physiotherapy treatment outside of usual weekday working hours.

If chest physiotherapy techniques are to be used in the critical care setting, it is vital that all healthcare professionals involved in their provision have a sound understanding of, and implement them, in accordance with current evidence-based practice to ensure optimal patient outcomes and safety. It is unclear whether nursing professionals continue to use traditional chest physiotherapy techniques as a part of their role in critical care, what their opinions are, and, additionally, how highly they regard their knowledge and confidence pertaining to these techniques. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the use of, and attitudes towards, traditional chest physiotherapy techniques by nursing professionals in critical care.

Methods

Design and setting

A cross-sectional national survey of critical care nurses working in Australia was conducted between March and July 2015. Approval for the study was granted by The University of Newcastle, Human Research Ethics Committee (Callaghan, Australia).

Survey instrument

In the absence of a published and/or validated instrument for the investigation of attitudes of nursing professionals regarding traditional chest physiotherapy techniques, a survey was custom designed. The survey content was developed by the research team and informed by the project aims and available literature.

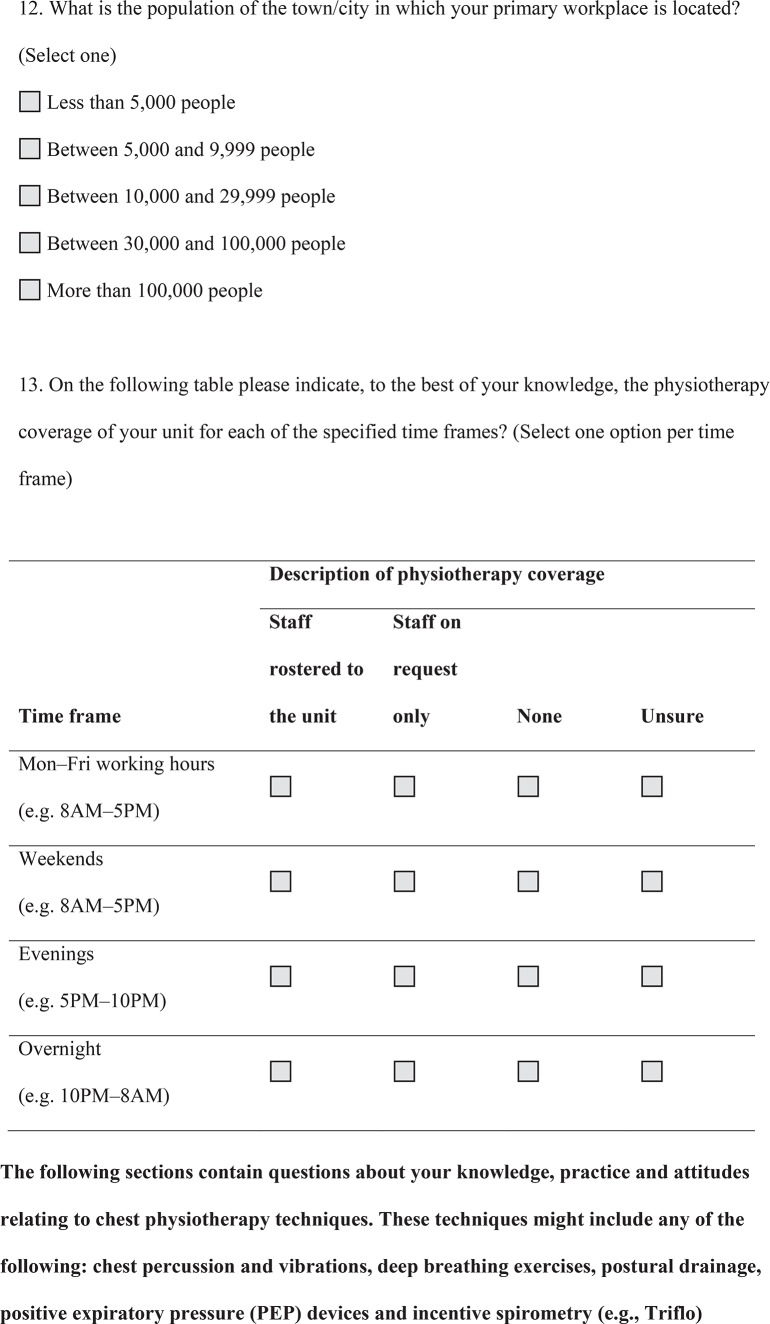

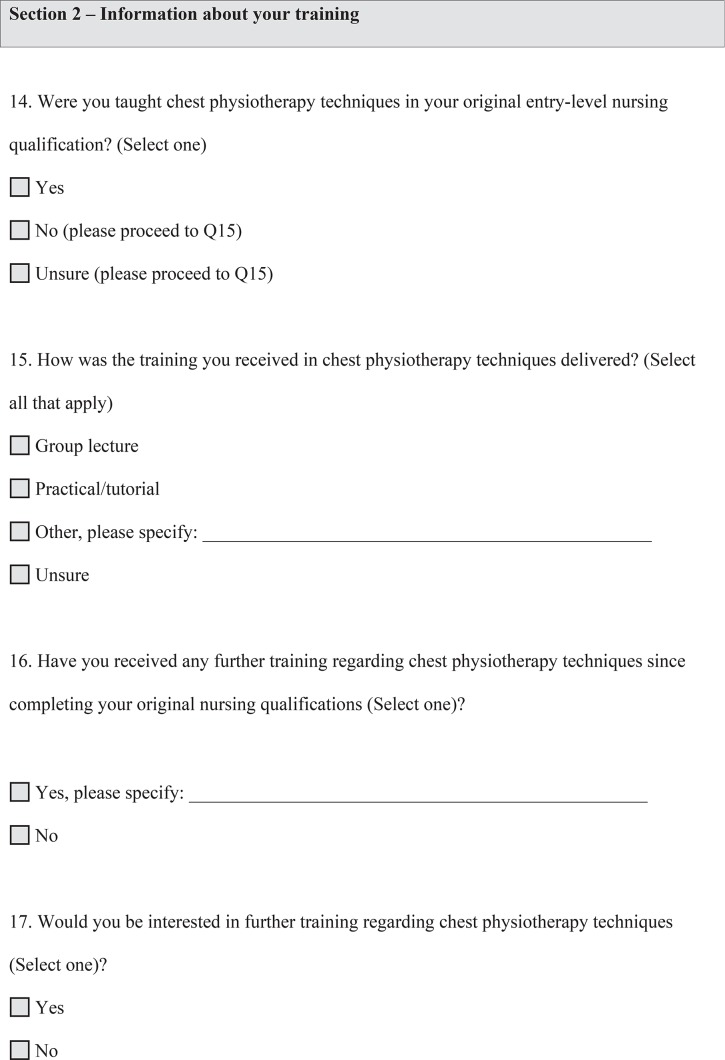

Prior to dissemination, two expert critical care nurses independent of the research team and main sample reviewed the survey content and utility. Feedback regarding readability and structure was provided and minor modifications were made accordingly. The final survey instrument (Appendix 1) consisted of 28 questions divided into five sections. Sections covered participant characteristics and workplace information, previous training and clinical use, and knowledge, confidence and understanding of chest physiotherapy techniques. Questions were largely closed categorical in form with several open-ended questions to allow participants to provide additional comments. The survey was administered online and hosted via Survey Monkey (www.surveymonkey.com).

Participants

Current members of the Australian College of Critical Care Nurses (ACCCN) association were invited to participate in the study. The ACCCN is a nonprofit membership-based organisation. Members of the ACCCN work across the critical care clinical spectrum, including intensive care and high dependency units, in clinical, educational, managerial, and research roles. Those members of the ACCCN who had indicated their willingness to be contacted for research purposes, as indicated on their group membership form, were eligible to participate (n = 1222). There were no exclusion criteria.

Data collection

An invitation to participate, a link to the online survey, and a participant information form were emailed to eligible group members by the General Manager of the ACCCN on behalf of the research team. Completion and submission of the online survey constituted informed participant consent. A single reminder email was sent 4 weeks after the initial invitation.

Data analysis

All data were analysed using the SPSS version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). All closed categorical responses were analysed descriptively using frequencies and percentages. Comparisons of categorical data between respondent current clinical use of chest physiotherapy techniques and years of clinical nursing experience, population of critical care setting, and degree of physiotherapy service availability were undertaken using chi-square or Fisher's exact test when cell counts were small. All tests were assessed at a significance level of p = 0.05. Responses to open-ended questions were transcribed verbatim, and simple content analysis was performed to identify recurring concepts.

Results

Respondent and workplace characteristics

A total of 142 members completed the online survey, a response rate of 12%. The majority of respondents (n = 123, 86%) were females with a mean age of 48 years (range 24–68, standard deviation = 9.78). Respondents were from all states and territories within Australia; however, Victoria (n = 53, 37%), New South Wales (n = 30, 21%), and Queensland (n = 25, 18%) had the highest representation. Most respondents (n = 116, 82%) worked in a public hospital with a small proportion (n = 17, 12%) working in a private health facility. Respondent and workplace characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Respondent characteristics and workplace information (n = 142).

| Respondents | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 123 (87) |

| Male | 18 (12) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

| Highest qualification | |

| Diploma | 22 (15) |

| Bachelor's degree | 53 (37) |

| Master's degree | 53 (37) |

| Doctorate | 9 (7) |

| Missing | 5 (4) |

| Location of entry-level training | |

| Australia | 121 (84) |

| UK | 9 (7) |

| Othera | 9 (7) |

| Missing | 3 (2) |

| Years of clinical nursing experience | |

| < 10 years | 17 (11) |

| 11–20 years | 35 (25) |

| > 20 years | 88 (63) |

| Missing | 2 (1) |

| Workplace | n (%) |

| Employment status | |

| Full time | 76 (53) |

| Part time | 59 (42) |

| Casual/agency | 6 (4) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

| Primary job classification | |

| Clinical | 118 (83) |

| Academia | 9 (7) |

| Research | 8 (5) |

| Otherb | 4 (3) |

| Missing | 3 (2) |

| Critical care setting | |

| Adult intensive care unit | 104 (73) |

| Paediatric/neonatal intensive care unit | 14 (10) |

| Specialist intensive care unitc | 4 (3) |

| High dependency unit | 3 (2) |

| Other unitd | 9 (7) |

| Missing | 8 (5) |

| Population of primary workplace location | |

| < 30,000 people | 15 (10) |

| Between 30,000 and 100,000 people | 22 (15) |

| > 100,000 people | 104 (73) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

Canada, Chile, France, Germany, India, Singapore, South Africa.

Administration, management, project officer, quality and safety.

Burns, coronary care, trauma.

Cardiothoracics, emergency, mixed adult/paediatric unit.

Training and clinical practice regarding traditional chest physiotherapy techniques

Nearly all respondents (n = 132, 93%) had performed traditional chest physiotherapy techniques at some stage during their clinical nursing practice. The majority of nursing professionals (n = 121, 85%) indicated that they utilised chest physiotherapy techniques in their current clinical practice, and the same number of respondents (n = 121, 85%) considered the provision of traditional chest physiotherapy techniques to be a part of a nurse's role.

More than half of the respondents (n = 78, 55%) reported that they performed chest physiotherapy techniques both independently and under the direction of a physiotherapist. A small proportion of respondents (n = 8, 5%) indicated that they applied chest physiotherapy techniques only under the direction of a physiotherapist.

Most respondents (n = 102, 72%) had received some form of training regarding chest physiotherapy techniques in their entry-level nursing qualification with many (n = 73, 51%) subsequently participating in additional training.

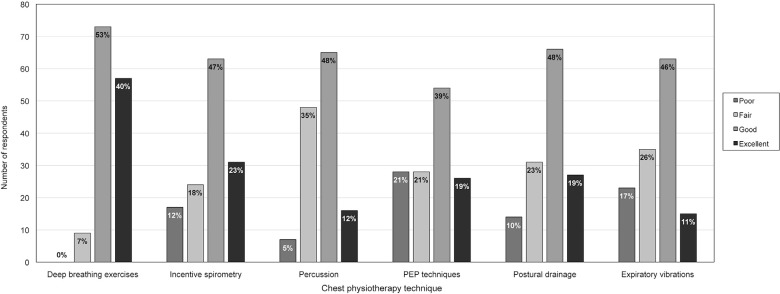

Data on respondents' use of individual chest physiotherapy techniques is presented in Figure 1. Although few respondents reported the use of “other” chest physiotherapy treatment techniques, 10 cited the use of manual and ventilator hyperinflation.

Figure 1.

Respondents' reported use of chest physiotherapy techniques in their clinical nursing practice (n = 142). PEP = positive expiratory pressure.

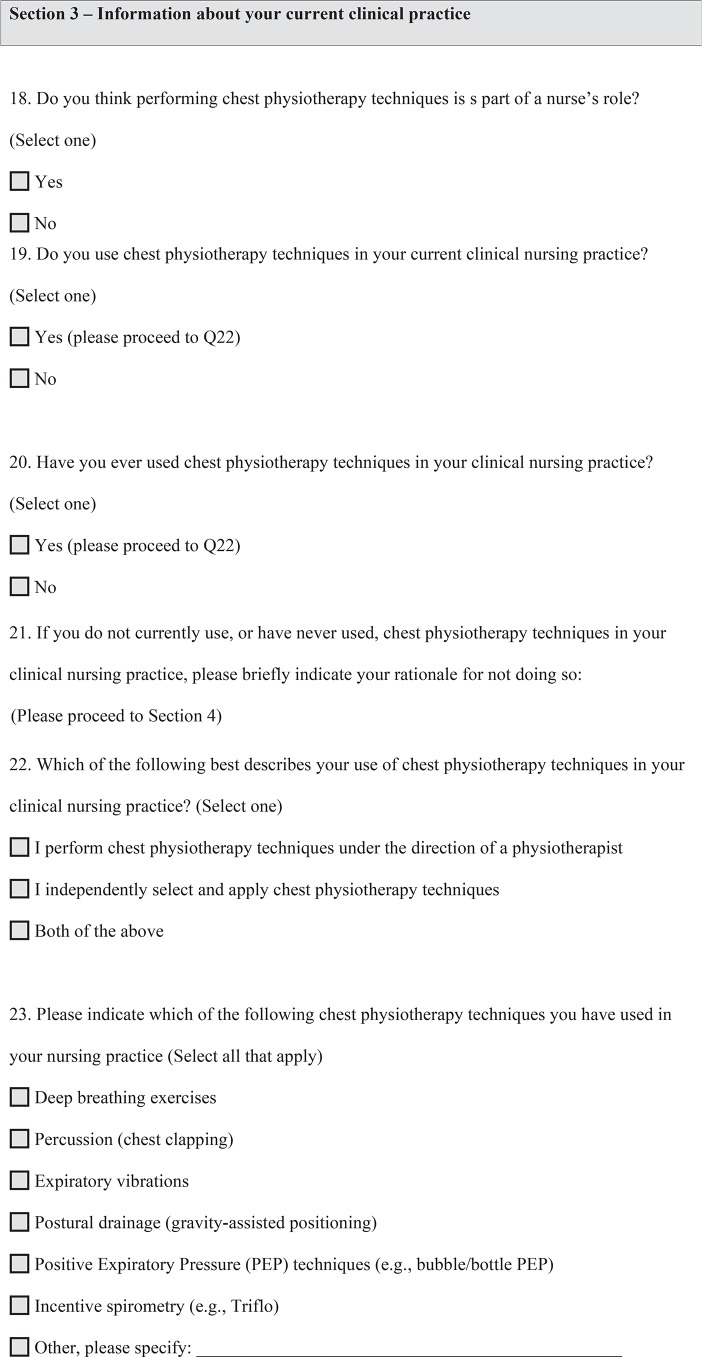

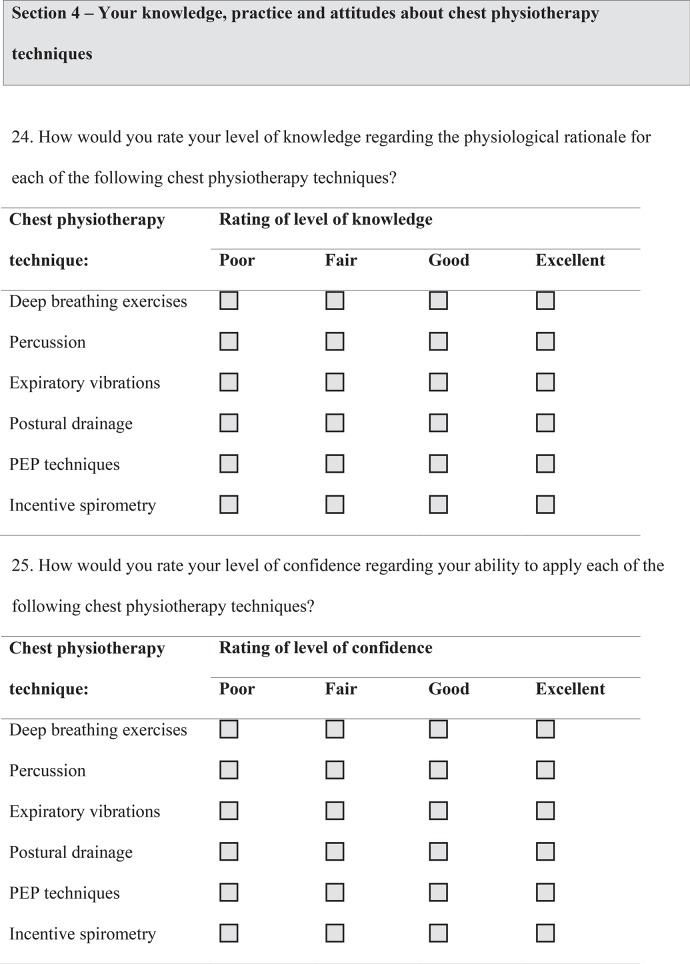

Knowledge, confidence, and understanding regarding traditional chest physiotherapy techniques

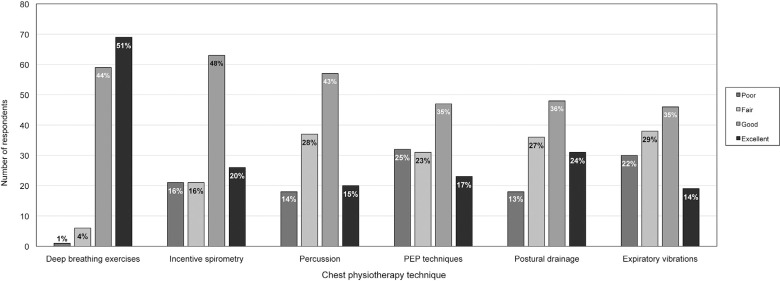

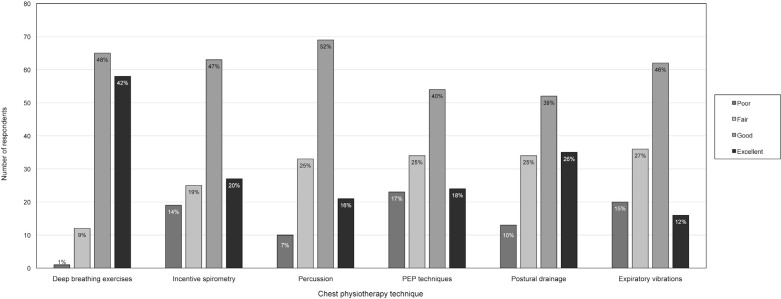

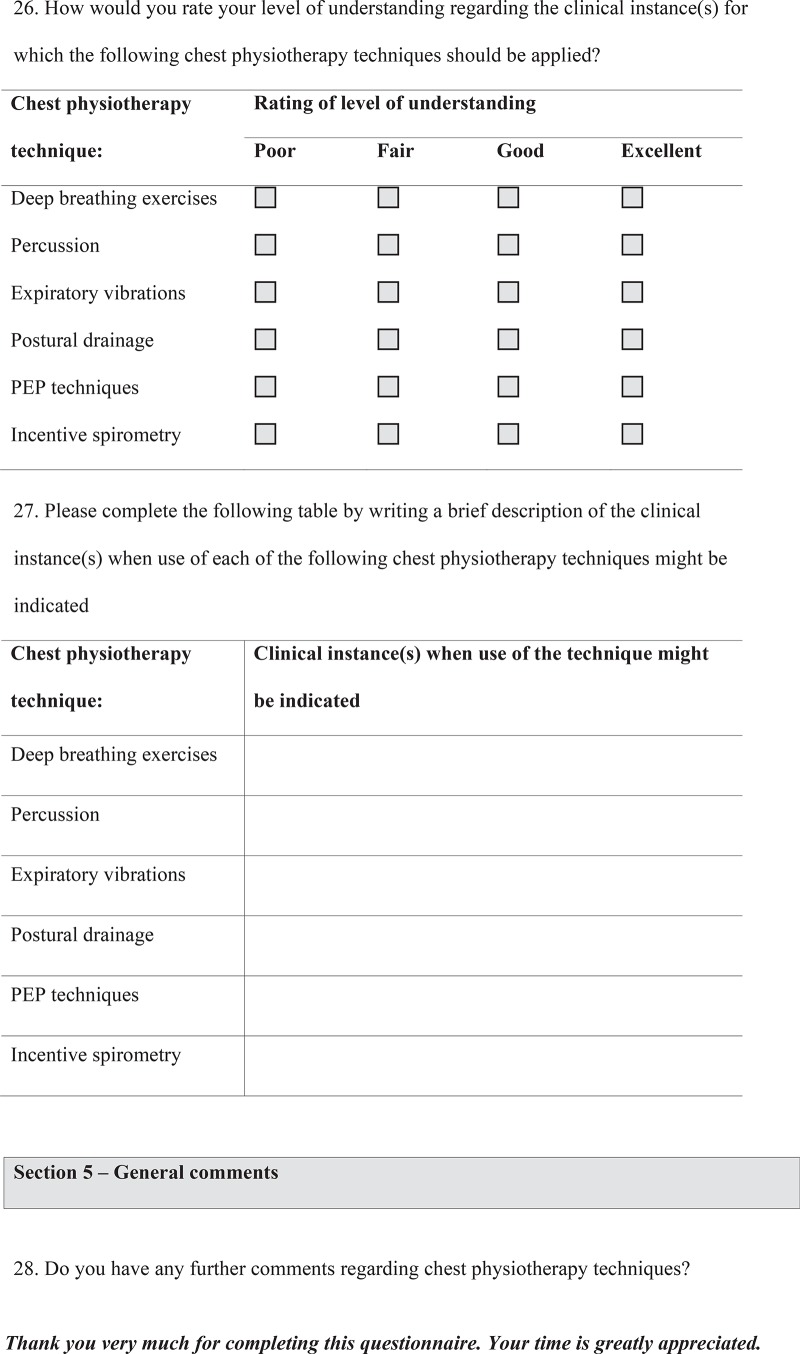

Respondent self-rated knowledge, confidence, and understanding regarding the pathophysiological rationale and application of chest physiotherapy techniques are presented in Figures 2, 3 and 4 respectively.

Figure 2.

Respondents' self-rated level of knowledge regarding the physiological rationale of chest physiotherapy techniques (n = 142). PEP = positive expiratory pressure.

Figure 3.

Respondents' self-rated level of confidence regarding their ability to apply chest physiotherapy techniques in clinical practice (n = 142). PEP = positive expiratory pressure.

Figure 4.

Respondents' self-rated level of understanding regarding their ability to apply chest physiotherapy techniques in clinical practice (n = 142). PEP = positive expiratory pressure.

Physiotherapy service availability within critical care

Respondents were asked to report the degree of physiotherapy service availability within their critical care unit across four different time frames. The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Respondents' reported degree of physiotherapy service availability within their critical care unit.

| Physiotherapy availability | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Weekdays (e.g., 8AM–5PM) | |

| Physiotherapy staff rostered to the unit | 127 (89) |

| Physiotherapy staff on request/call only | 12 (9) |

| Missing | 3 (2) |

| Weekends (e.g., 8AM–5PM) | |

| Physiotherapy staff rostered to the unit | 86 (61) |

| Physiotherapy staff on request/call only | 50 (35) |

| Unsure of physiotherapy coverage | 2 (1) |

| Missing | 4 (3) |

| Evenings (e.g., 5PM–10PM) | |

| Physiotherapy staff rostered to the unit | 11 (8) |

| Physiotherapy staff on request/call only | 48 (34) |

| No physiotherapy staff rostered or on request/call | 53 (37) |

| Unsure of physiotherapy coverage | 11 (8) |

| Missing | 19 (13) |

| Overnight (e.g., 10PM–8AM) | |

| Physiotherapy staff rostered to the unit | 2 (1) |

| Physiotherapy staff on request/call only | 45 (32) |

| No physiotherapy staff rostered or on request/call | 68 (48) |

| Unsure of physiotherapy coverage | 9 (6) |

| Missing | 18 (13) |

There was no significant difference between respondent current clinical use of traditional chest physiotherapy techniques and years of clinical nursing experience, population of critical care setting, or degree of physiotherapy service availability.

Responses to open-ended questions

Participants were asked to provide general written comments regarding their use of traditional chest physiotherapy techniques in the critical care setting. The four key concepts identified are described below.

Availability of physiotherapy services

Many respondents commented that the availability of physiotherapy services impacted on the application of chest physiotherapy techniques by nursing professionals in the critical care setting. Nurses indicated that in the absence of physiotherapy coverage, they were required to provide chest physiotherapy treatments.

“If physios wish to do all treatments, they need to be funded over 24 hours—ICU is a 24-hour service, not just Monday–Friday 08.00–17.00.”

“Physios are there for a short time during the day. They might see a patient once or twice a week…once a day. A small period with physio. Registered Nurses (RNs) are there 24*7, and this care should occur 24*7.”

Need for training

Many respondents acknowledged the expertise of physiotherapists in this area of practice and also highlighted the need for nursing professionals to receive more training regarding physiotherapy techniques.

“It would be really great if the physios could run short courses or classes for nurses (and medical staff) on the techniques and uses so we can continue therapy after hours to ensure the patient does not lose the benefits they gain.”

“…if physiotherapy techniques change, it should be the physiotherapists' responsibility to update/re-educate…the nursing staff.”

The multiprofessional team

The benefits of taking a multiprofessional approach to the management of people with respiratory dysfunction requiring physiotherapy in critical care were acknowledged by many respondents.

“With team work, we can all work towards a better outcome for the patient.”

“Chest physiotherapy techniques can and should be applied using a multidisciplinary approach and sharing of skills and expertise.”

Scope of professional practice

This key concept pertains to the role of nursing and physiotherapy professionals in the provision of chest physiotherapy. This concept encompasses notions of ‘ownership’ and the shifting of professional roles over time. Some respondents considered the provision of chest physiotherapy to be the responsibility of nurses and within their scope of practice. Others indicated that it was the responsibility of the physiotherapist. Many respondents also commented on how the assumption of responsibility for providing this service had changed over time.

“Other than deep breathing, chest physio should be prescribed by a physio.”

“It seems to be something we were taught (and did) years ago, however I think the more recently qualified nurses tend to leave it to the physiotherapists now.”

“I feel that ‘older’ nurses… are happy to do physio as we have done this many times and consider it part of our role.”

“Having grown up in an era where the responsibility for physiotherapy was in fact a nurse's responsibility, the current role of physios and nurses…is interesting. Nurses, in my view, have abdicated their responsibility over the last 10 years or so…physios have become more academic, which is great, but has altered their view of their clinical roles.”

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the knowledge, clinical practice and attitudes of nursing professionals regarding traditional chest physiotherapy techniques. Several main findings emerged from this research: (1) most nursing professionals working in critical care continued to utilise traditional chest physiotherapy techniques in clinical practice, and the majority of these respondents viewed the provision of chest physiotherapy techniques as a part of nursing role; and (2) nursing professionals were confident with their clinical application of chest physiotherapy techniques and possessed a high level of perceived knowledge and clinical skill regarding the provision of chest physiotherapy techniques.

Although participants were not explicitly asked, there may be several reasons that nursing professionals are continuing to utilise traditional chest physiotherapy techniques in their clinical practice and perceive these to be a part of their role. Nursing professionals may be employing traditional chest physiotherapy techniques prophylactically in the management of critically ill patients. Nursing professionals may be performing the techniques as a part of routine nursing care in conjunction with other techniques, such as positioning, manual hyperinflation, and suctioning. Considering that a large proportion of respondents possessed greater than 20 years of clinical experience, many nursing professionals may come from a period where chest physiotherapy techniques were performed for all intubated and mechanically ventilated patients, regardless of their presenting condition. This is no longer recognised as the best practice [2].

Most respondents self-reported a high level of knowledge and understanding pertaining to the physiological rationale of individual chest physiotherapy techniques, and were confident in their ability to safely and effectively apply selected chest physiotherapy techniques in the clinical setting. Respondents may have acquired clinical knowledge and confidence in their ability to employ chest physiotherapy techniques as a result of their extensive clinical nursing experience. In addition, the complex nature of the critical care environment requires nursing professionals to be responsible for independent clinical decision-making to ensure optimal management of critically ill patients [14]. This is likely to extend to the delivery of chest physiotherapy techniques as nursing professionals working in critical care may be able to recognise signs of deteriorating respiratory status and be confident to implement chest physiotherapy techniques accordingly using assessment findings.

Physiotherapists are extensively trained and assessed on the theory and application of chest physiotherapy techniques as a part of their entry-level qualifications. It is unclear if the theoretical understanding, clinical reasoning, and practical skills of nursing staff related to chest physiotherapy techniques are of a similar standard to that of physiotherapists. The respondents in this study reported low levels of formal training in this area of practice. The application of these techniques in the absence of adequate training may lead to adverse patient outcomes. While it is possible for physiotherapists to institute training for nursing professionals, physiotherapists already possess the required knowledge and skill set. Physiotherapists should take an active role in promoting their ability to provide an individualised, evidence-based approach to managing patients in the critical care setting. Continued advocacy for the unique professional capabilities of physiotherapists through ongoing performance and dissemination of research and via interprofessional education is warranted. Further research to investigate how the role and clinical practice of the physiotherapist is perceived by other health professionals may be necessary.

Limitations in physiotherapy service availability in critical care may result in nursing professionals regarding the provision of physiotherapy techniques as a shared responsibility with physiotherapists. Physiotherapy services are generally provided during normal weekday working hours, and only a small number of units have the provision for a 24-hour or after-hours physiotherapy coverage, which is in line with the findings of this study [15–17]. In addition, it is common for a physiotherapist working in a critical care unit to be responsible for the management of patients across various other clinical settings within the hospital. Nursing professionals are primarily staffed on a nurse to patient ratio of 1:1 for intensive care unit beds and 1:2 in high dependency units [16]. It is this difference in service availability that may lead to nursing staff being considered a convenient professional group to provide physiotherapy techniques in critical care. Consideration should be given to providing additional funding to address identified limitations in physiotherapy service availability.

The main limitation of this study was the low response rate. Despite this, a considerable amount of valuable data was collected and useful insights into the topic can be drawn. The respondents had a wide range of clinical experience, were from all Australian states, territories, metropolitan, and regional areas and were working in a variety of critical care settings. Therefore, they would appear to be generally representative of nursing professionals currently working in critical care in Australia. Sampling participants from a special interest group such as the ACCCN may have resulted in a potential response bias. It is possible that those who chose to participate by completing the survey might have a particular interest in this area. A wider survey using a larger sample size with a more thorough exploration of specialised critical care populations (such as neonatal intensive care) is necessary, as is investigation of the international context. The use of a nonvalidated survey instrument is an additional study limitation. However, this was a preliminary investigation, and the survey content was judged to be acceptable on review by experienced critical care nurses prior to dissemination.

This study has provided insight into the utilisation of traditional chest physiotherapy techniques by nursing professionals in Australian critical care settings. Further research should focus on investigating the reasons why nursing professionals might assume responsibility for the provision of chest physiotherapy techniques and whether their application of these techniques is consistent with evidence-based recommendations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Lynn Herson, General Manager of the Australian College of Critical Care Nurses, for assistance with the conduct of this study.

Appendix 1. Online survey

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Funding/support: No financial or material support of any kind was received for the work described in this article.

Author contributions: CJN, JAS, and CLJ participated in the following: study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of study data; manuscript drafting and critical revision for publication; manuscript final editing and approval for submission.

References

- 1. Gosselink R, Bott J, Johnson M, Dean E, Nava S, Norrenberg M, et al. . Physiotherapy for adult patients with critical illness: recommendations of the European Respiratory Society and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Task Force on physiotherapy for critically ill patients. J Intensive Care Med 2008;34:1188–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stiller K. Physiotherapy in intensive care: an updated systematic review. Chest 2013;144:825–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Osadnik C, McDonald C, Jones A, Holland A. Airway clearance techniques for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(Issue 3):CD008328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strickland S, Rubin B, Drescher G, Haas C, O'Malley C, Volsko T, et al. . AARC clinical practice guideline: effectiveness of nonpharmacologic airway clearance therapies in hospitalized patients. Respir Care 2013;58:2187–2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berney S, Haines K, Denehy L. Physiotherapy in critical care in Australia. Cardiopulmonary Phys Ther 2012;23:19–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kayambu G, Boots R, Paratz J. Physical therapy for the critically ill in the ICU: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1543–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pathmanathan N, Beaumont N, Gratrix N. Respiratory physiotherapy in the critical care unit. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain 2014;15:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Castro A, Calil S, Freitas S, Oliveira A, Porto E. Chest physiotherapy effectiveness to reduce hospitalization and mechanical ventilation length of stay, pulmonary infection rate and mortality in ICU patients. Respir Med 2013;107:68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jenkins S. Recent advances and future challenges in cardiopulmonary physiotherapy. Physiother Theory Pract 1998;14:177–181. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones A, Hutchinson R, Oh T. Chest physiotherapy practice in intensive care units in Australia, the UK and Hong Kong. Physiother Theory Pract 1992;8:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wallis C, Prasad A. Who needs chest physiotherapy? Moving from anecdote to evidence. Arch Dis Child 1999;80:393–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grimandi R, Paupy H, Prot H, Giroux-Metges M, Giacardi C. Early mobilization in ICU: about new strategies in physiotherapy's care. Crit Care Med 2015;43:e400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sommers J, Engelbert R, Dettling-Ihnenfeldt D, Gosselink R, Spronk P, Nollet F, et al. . Physiotherapy in the intensive care unit: an evidence-based, expert driven, practical statement and rehabilitation recommendations. Clin Rehabil 2015;29:1051–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baid H, Creed F, Hargreaves J. Oxford Handbook of Critical Care Nursing. 2nd ed Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chaboyer W, Gass E, Foster M. Patterns of chest physiotherapy in Australian intensive care units. J Crit Care 2004;19:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Skinner E, Warrillow S, Denehy L. Organisation and resource management in the intensive care unit: a critical review. Int J Ther Rehabil 2015;22:187–197. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Norrenberg M, Vincent J. A profile of European intensive care unit physiotherapists. Intensive Care Med 2000;26:988–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]