Abstract

Base-promoted C-H cleavage without transition metals opens a practical alternative for the one based on noble metals or radical initiators. The resulting carbanion can pass through radical addition to unsaturated bonds like C-N or C-C triple bonds, in which stoichiometric oxidants are needed. When in situ C-H cleavage meets catalytic carbanion-radical relay, it turns to be challenging but has not been accomplished yet. Here we report the combination of base-promoted benzylic C-H cleavage and copper-catalyzed carbanion-radical redox relay. Catalytic amount of naturally abundant and inexpensive copper salt, such as copper(II) sulfate, is used for anion-radical redox relay without any external oxidant. By avoiding using N-O/N-N homolysis or radical initiators to generate iminyl radicals, this strategy realizes modular synthesis of N-H indoles and analogs from abundant feedstocks, such as toluene and nitrile derivatives, and also enables rapid synthesis of large scale pharmaceuticals.

The synthesis of high value heterocycles from cheap starting materials remains challenging. Here, the authors develop a new strategy to realize practical and modular synthesis of N-H indoles and analogs from toluene and nitrile derivatives using naturally abundant copper salt as catalyst.

Introduction

Base-promoted C-H cleavage in the absence of transition metal catalysts, especially, without noble metals, such as rhodium, palladium, and iridium, has emerged near recently (Fig. 1a)1–4. This approach opens a practical and cheap alternative for previously established C-H cleavage based on noble metals or radical initiators. It has been well known that carbanion can pass through radical addition to unsaturated bonds like C-N or C-C triple bonds using a metal oxidant such as Cu(II) (Fig. 1b)5–15. Stoichiometric oxidants are needed for high turnovers5. The catalytic copper-mediated anion-radical relay is not possible unless an extra oxidant is presented. Thus problem emerges when in situ C-H cleavage meets carbanion-radical relay without stoichiometric high oxidation state metals or oxidants. To the best of our knowledge, the example of anion-radical oxidative relay using catalytic amount of copper salt has not been accomplished yet5.

Fig. 1.

Formation of iminyl radical from anion/radical redox relay other than N-O cleavage or initiators. a Base-promoted benzylic C-H cleavage in the absence of transition metal catalysts followed by an addition to alkenes. b Two steps/pots anion-radical relay using metal oxidants. c Methods for the generation of iminyl radicals. d This work: naturally abundant copper salt catalyzed redox C-H cyclization via iminyl radical from intermolecular anion-radical relay

On the other hand, iminyl radical has been well-established as intermediates for the construction of N-containing 5- and 6-membered heterocycles including indoles and pyridines16–21. Iminyl radical is normally generated from N-O bond cleavage using either light or initiators (Fig. 1c), which has attracted high interests of chemists with the renaissance of radical reactions in organic synthesis17,22–25. It has been barely reported that intermolecular carbanion-radical relay can furnish iminyl radical by catalytic transition metals. Therefore a strategy needs to be established for aforementioned challenges.

As a typical 5-memebrered N-containing rings, indoles are among the most widely existing skeletons in natural products as well as in pharmaceuticals. Despite that the approaches for the synthesis indoles have been well established26–31, actually, most methods are based on the derivatives of anilines26,32–64, where the C-N bonds have been generally preinstalled. Therefore, we envision that a strategy through benzylic C-H addition and iminyl radical relay can enable the cyclization of toluenes and nitriles to indoles. Herein, we report our recent results (Fig. 1d).

Herein, we report our recent results in the probe of the copper-catalyzed anion-radical redox relay, we initialize the reaction by a base-promoted benzylic C-H cleavage to generate the benzyl anion A, which passes through a Cu(II)-mediated oxidation to radical B5. The intermolecular radical addition of B to PhCN generates iminyl radial C, which is trapped by aryl ring to form D65–67. D is reduced by Cu(I) to indoles with the regeneration of Cu(II) (Fig. 2a). The reaction in the presence of 2 mol% CuSO4 affords 85% of 3a (Fig. 2b), whereas the radical trapping experiment shows that TEMPO totally inhibits the reaction with the observation of 1a-OTEMP adduct (Fig. 2c), suggesting the radical pathway should be rational. No Ullmann-type intramolecular cyclization further proves the radical pathway (Fig. 2d). Further investigation using palladium instead of copper salts proves no promotion effect. Therefore, CuSO4 herein plays a crucial role of redox catalyst to generate benzylic radical from benzylic anion and enables the efficient synthesis of N-H indoles and analogs from toluene and nitrile derivatives.

Fig. 2.

Iminyl radical from anion-radical redox relay. a Pathway for the copper-catalyzed anion-radical redox relay. b The anion-radical redox relay of 1a and 2a in the presence of 2 mol% CuSO4 affords 85% of 3a. c TEMPO inhibits the anion-radical redox was confirmed by the observation of 1a-OTEMP adduct. d No Ullmann-type intramolecular cyclization was observed

Results

Investigations of reaction conditions and scope

The reaction conditions were optimized. First, various copper salts were investigated as catalysts in the cyclization of toluene 1a with nitrile 2a (Table 1). CuO and Cu2O afford similar yields (entries 2 and 3), indicating that either Cu(II) or Cu(I) might be involved in this reaction. CuSO4 gives the best yield as 77% (entry 6). The reaction in octane is better than that in other solvents, such as dioxane, toluene, and DMF (entries 6, 9–11). Increasing the concentration results in the slight increase of yield to 81% (entries 6 and 12). Reducing the catalyst loading from 10 to 2 mol % also gives rise to the increase of yields (entries 12–13). The unreacted nitrile 2a was recovered almost quantitatively (entry 13). Palladium catalysts do not promote this reaction (entries 16–18). The reaction condition in entry 13 was chosen for the standard reaction conditions where 2 mol % of CuSO4 was used as catalyst.

Table 1.

Reaction conditions

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrya | [cat](mol %) | Base | Solvent | 3a(%)c |

| 1 | CuTC (10) | tBuOK | octane | 48 |

| 2 | Cu2O (10) | tBuOK | octane | 62 |

| 3 | CuO (10) | tBuOK | octane | 68 |

| 4 | CuCl (10) | tBuOK | octane | 57 |

| 5 | CuCl2 (10) | tBuOK | octane | 63 |

| 6 | CuSO4 (10) | tBuOK | octane | 77 |

| 7 | CuSO4 (10) | tBuONa | octane | 0 |

| 8 | CuSO4 (10) | KOH | octane | 0 |

| 9 | CuSO4 (10) | tBuOK | dioxane | 70 |

| 10 | CuSO4 (10) | tBuOK | toluene | 45 |

| 11 | CuSO4 (10) | tBuOK | DMF | 22 |

| 12b | CuSO4 (10) | tBuOK | octane | 81 |

| 13b, d | CuSO4 (2) | tBuOK | octane | 85 |

| 14 | Cu(300 mesh) | tBuOK | octane | 54 |

| 15 | none | tBuOK | octane | 11 |

| 16 | Pd2(dba)3 (5) | tBuOK | octane | 0 |

| 17 | Pd(PPh3)4 (10) | tBuOK | octane | 17 |

| 18 | Pd(OAc)2 (10) | tBuOK | octane | 15 |

aConditions: 1a (1 mmol), 2a (5 mmol), [cat] (x mol %), tBuOK (4 mmol), solvent (1 mL), 15 h, 90 °C, argon

bOctane (0.75 mL)

cDetermined by 1H NMR

dBy column purification, 4.1 out of 5 equiv of nitriles 2a was recovered

With the standard reaction conditions in hand, the scope of this method was investigated. Various 2-halotoluenes were subjected to the standard conditions and the corresponding indole products were obtained (Fig. 3). Halogen can survive under basic conditions (3b, 3c, 3d, 3i, and 3l). Such indoles are useful intermediates for further functionalization via cross coupling reactions. Starting materials with hydroxyl and carboxyl groups can directly undergo cyclization without protecting groups (3f and 3g). 7-Azoindoles 3q and 3r could also be achieved by these reactions. Functional groups and protecting groups, such as halogen (3b-d, 3j, 3l, 3u), (Ar)OH (3f), COOH (3g), MOM (3p), amide (3l), and ester (3t), are all tolerable in this reaction.

Fig. 3.

Scope of methyl (het)arenes and nitriles. Reaction conditions: CuSO4 (2 mol%), 1 (1 mmol), 2 (5 mmol), tBuOK (5 mmol), octane (0.75 mL). Extra 1 mmol tBuOK was used for 3f and 3g. a2 (1.5 mL) was used as solvent. bOctane (3 mL). cCuSO4 (20 mol %) was used. a 2-Iodomethyl arenes were subjected to the standard conditions. b 2-Bromomethyl arenes were subjected to the standard conditions. c 2-Chloromethyl arenes were subjected to the standard conditions

Application in the synthesis of BACE1 inhibitor

This indoles synthesis from nitriles and toluenes is a synthetically practical and scalable method. By this method, a BACE1 inhibitor68 is synthesized from benzonitrile and 2-iodotoluene by our method in three steps in gram scale (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Gram-scale synthesis of pharmaceuticals. a BACE1 inhibitor is synthesized from 2-iodotoluene 1a and benzonitrile 2a in gram scale using anion-radical redox relay as the key step

Investigations of C3-substituted indoles and applications

C3-substituted indoles can also be synthesized by this method. Reaction conditions were further optimized on the basis of Table 1 (Table 2). Despite of the fact that even 1.5 equiv of nitrile affords 85% of 6d (entry 5), the conditions listed in entry 2 were chosen for the balance of yields and amounts of the base and nitriles.

Table 2.

Reaction conditions for the synthesis of 6

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrya | PhCN (equiv) | tBuOK (equiv) | t (h) | 6d (%) |

| 1b | 5 | 4 | 11 | 93 |

| 2 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 24 | 92 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 36 | 75 |

| 4 | 2 | 3 | 24 | 91 |

| 5 | 1.5 | 3 | 24 | 85 |

aConditions: 5d (1 mmol), 2a (1.5–5 mmol), CuSO4 (2 mol%), tBuOK (2–5 mmol), dioxane (0.75 mL), argon. Yields were determined by 1H NMR

bAt 60 °C

Indoles bearing both C3-substituents, such as phenyl, heteroaryl, phenoxyl, and phenylthio, were readily obtained (Figs. 5, 6a–d). These functionalized indoles are useful synthons or intermediates and are normally synthesized via C3-functionalization of indoles. For example, 2,3-diphenyl indole 6a is a key intermediate of a BACE1 inhibitor68. What should be mentioned is that the method for the synthesis of 3-sulfenylindoles is still limited69–73. Current method provides a powerful route to 3-sulfenylindoles (6d-6p, 6s-6t). Either aryl or alkyl substituted 3-sulfenylindoles could be achieved. C5-C7 bromo indoles are useful intermediates in organic synthesis, which were obtained in moderated to good yields (6m-6o). Plus the results in Fig. 4, most functional groups, such as halogen, OH, COOH, amide, ester, silyl protecting group, MOM, CF3, nitrile, pyridine, etc, have been tolerated in this reaction. Besides 2-halogen toluenes, 2-iodo ethyl benzene is also reactive to afford the desired 3-methyl indole 6r in 55% yield. Alkyl substituted 3-sulfenylindoles are normally difficult to generate due to the instability of aliphatic nitriles under strong basic conditions. To our delight, C2-alkyl indoles could also be prepared in moderate to good yields (Fig. 6, 6u–6z). The yields seem dependent on the steric hindrance of nitriles (6u, 6v vs 6w). Nevertheless, this reaction provides an efficient route to either aromatic or aliphatic substituted indoles.

Fig. 5.

Scope of C3-functionalized indoles. Reaction conditions: 5 (1 mmol), 2 (2.5 mmol), CuSO4 (2 mol %), tBuOK (2.5 mmol), dioxane (0.75 mL). a2 (5 mmol), tBuOK (4 mmol), octane (0.75 mL) instead of dioxane. b2 (1.5 mL) was used as solvent. cCuSO4 (10 mol %) was used. dDioxane (1.5 mL). e2 (15 mL) was used as solvent. fCuSO4 (20 mol %) was used. gDioxane (20 mL). htBuOK (4 mmol). itBuOK (4 mmol), no extra solvent. Brsm yield refers to the yield based on recovered starting material

Fig. 6.

Comparison between the synthesis of 3 from 1 and that from 5. a Synthesis of 3 using a one-pot cyclization-deprotection from 5. b Synthesis of 3 from the cyclization of 1 and 2. c Comparison between Route 1 and Route 2

C3-phenylthio can be easily removed in the presence of 2-mercaptobenzoic acid and CF3CO2H74. Thus PhS-group can be used as a leaving group in organic synthesis. In Fig. 6, a one-pot cyclization-deprotection synthesis of 3 either from 5 or 1 is demonstrated. Both indoles 3a and 3b were obtained in high yields via both routes, whereas indoles 3v and 3w could only be afforded by route 1 in high yields. The radical addition to nitrile is a nucleophilic process, thus the electron rich nitriles are normally less reactive. If the stability of radical intermediates are better, it gives more chance. Thio-groups are better stabilizer for adjacent carbon radicals. As a result, thio-substrate 5 is much better than 1 and some unavailable indoles from 1 and 2 can be achieved via 5. Compound 3v is a key intermediate for a potential anti-breast cancer medicine.

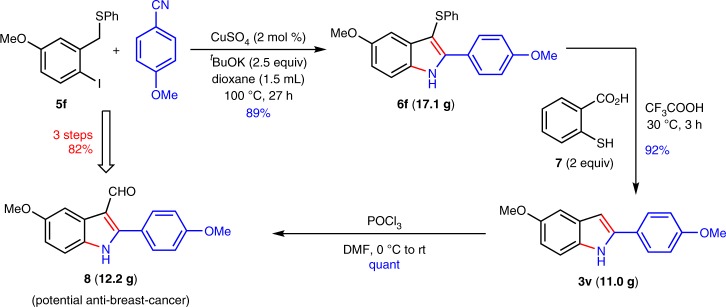

A potential anti-breast cancer reagent 8 is synthesized through three steps from 5f via the removal of the phenylthio in more than 10 gram-scale with overall 85% yield (Fig. 7)75.

Fig. 7.

Large-scale synthesis of pharmaceutical. A potential anti-breast cancer reagent 8 is synthesized from 5f in 10 gram-scale

Preliminary investigations of reaction mechanism

The reaction mechanism has been investigated with experimental evidence. In the reaction model in Fig. 2a, a Cu-catalyzed reaction cycle has been presented. The XPS experiments for the reaction using CuSO4 as catalyst demonstrated both Cu(II) and Cu(I), indicating that Cu-salts have been involved in the reaction (Fig. 8). The iodometric determination of Cu(II) in the reaction mixture was performed using a chloro-substrate to avoid the interruption of KI generated from the reaction. By the above titration, 65% Cu(II) was determined. Therefore the reaction could possibly pass through Fig. 1a via an iminyl radical addition to aryl rings.

Fig. 8.

Detection of Cu(II) and Cu(I) by XPS experiments. a To 3a when X = I and b to 3u when X = Cl. XPS Instrument type: Thermo ESCALAB 250Xi; X-ray excitation source: monochromatic Al Ka (hv = 1486.6 eV), power 150 W, X-ray beam 500 μm; Energy analyzer fixed transmission energy: 30 eV

Discussion

In conclusion, we have developed a catalytic approach for the in situ generation of iminyl radicals via an intermolecular carbanion-radical redox relay using a naturally abundant copper salt as catalyst. This strategy is realized by combining a base-promoted C-H cleavage and CuSO4-catalyzed carbanion-radical redox relay, where CuSO4 is a cheap and naturally abundant inorganic salt and as low as only 2 mol% catalyst loading is needed. By avoiding using N-O/N-N homolysis or radical initiators to generate iminyl radicals, this reaction provides a practical and noble metal-free access to indoles. What should be mentioned is that this method directly affords N-H indoles without any N-protecting groups, avoiding the irremovable or hard removable protecting groups in organic synthesis. This method is also a synthetically practical method, which has been readily applied in the modification of the large-scale pharmaceutical synthesis from abundant feedstocks using cheap and “green” reagents (CuSO4 and tBuOK).

Methods

General procedure

The Schlenk tube charged with tBuOK (2.5–5 mmol) and CuSO4 (0.02 mmol, 3.2 mg) was dried under high vacuum for 15 min. Octane (0.75 mL), 1 or 5 (1 mmol), and 2 (2.5–5 mmol) were added under argon and stirred at 90 °C. The resulting reaction mixture was monitored by TLC. Upon completion of the starting materials, the reaction mixture was directly purified by silica gel column to give the desired product.

Procedure for XPS experiments

A Schlenk tube charged with tBuOK (4 mmol, 449 mg) and CuSO4 (0.1 mmol, 16 mg) was dried under high vacuum for 15 min. Octane (0.75 mL), 1 (1 mmol), and 2a (5 mmol) were added under argon and stirred at 90 °C for 8 h. The mixture was concentrated under vacuum and the solid was measured by XPS tests.

Iodometric determination of Cu(II) in the reaction mixture

A Schlenk tube charged with tBuOK (4 mmol, 449 mg) and CuSO4 (0.1 mmol, 16 mg) was dried under high vacuum for 15 min. Octane (0.75 mL), 1u (1 mmol) and 2a (5 mmol) were added under argon and stirred at 90 °C. The reaction was stirred for 8 h and quenched by CH2Cl2 and extracted with H2O. The aqueous phase were combined. When the pH was adjusted to 7–8, KI (8 mmol) and 5 ml of 0.5 wt% starch solution were sequentially added. Sodium thiosulfate standard titration solution [c(Na2S2O3) = 0.05 mol/L] was used to titrate until the solution blue disappeared. Cu(II) was determined as 0.065 mmol (65% based on 10 mol% CuSO4).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21672196, 21602001, 21831007) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB20000000) for financial support.

Author contributions

X-H.S., H-X.Z., B.Y., L.T. and J-L.F. performed experiments and characterization. Y-B.K. and J-P.Q. conceived and supervised the project and research plan. Y-B.K. and J-P.Q. wrote the manuscript and secured funding.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting this study are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jian-Ping Qu, Email: ias_jpqu@njtech.edu.cn.

Yan-Biao Kang, Email: ybkang@ustc.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-08849-z.

References

- 1.Zhai DD, Zhang XY, Liu YF, Zheng L, Guan BT. Potassium amide-catalyzed benzylic C−H bond addition of alkylpyridines to styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:1650–1653. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu YF, Zhai DD, Zhang XY, Guan BT. Potassium-zincate-catalyzed benzylic C−H bond addition of diarylmethanes to styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:8245–8249. doi: 10.1002/anie.201713165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamashita Y, Suzuki H, Sato I, Hirata T, Kobayashi S. Catalytic direct-type addition reactions of alkylarenes with imines and alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:6896–6900. doi: 10.1002/anie.201711291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, Zheng Z, Xu X, Mao J, Walsh PJ. One-pot aminobenzylation of aldehydes with toluenes. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3365–3372. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05638-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rathke MW, Lindert A. Reaction of ester enolates with copper(II) salts. Synthesis of substituted succinate esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971;93:4605–4606. doi: 10.1021/ja00747a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito Y, Konoike T, Saegusa T. Reaction of ketone enolates with copper dichloride. Synth. 1,4-diketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:2912–2914. doi: 10.1021/ja00843a057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito Y, Konoike T, Harada T, Saegusa T. Synthesis of 1,4-diketones by oxidative coupling of ketone enolates with copper(II) chloride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:1487–1493. doi: 10.1021/ja00447a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paquette LA, Bzowej EI, Branan BM, Stanton KJ. Oxidative coupling of the enolate anion of (1R)-(+)-verbenone with Fe(III) and Cu(II) salts. Two modes of conjoining this bicyclic ketone across a benzene ring. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:7277–7283. doi: 10.1021/jo00127a037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baran PS, Richter JM. Direct coupling of indoles with carbonyl compounds: short, enantioselective, gram-scale synthetic entry into the hapalindole and fischerindole alkaloid families. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7450–7451. doi: 10.1021/ja047874w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baran PS, DeMartino MP. Intermolecular oxidative enolate heterocoupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:7083–7086. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo F, Konkol LC, Thomson RJ. Enantioselective synthesis of biphenols from 1,4-diketones by traceless central-to-axial chirality exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18–20. doi: 10.1021/ja108717r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heiba EAI, Dessau RM. Oxidation by metal salts. XI. Formation of dihydrofurans. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:3456–3457. doi: 10.1021/jo00937a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frazier RH, Harlow RL. Oxidative coupling of ketone enolates by ferric chloride. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:5408–5411. doi: 10.1021/jo01314a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baran PS, Guerrero CA, Ambhaikar NB, Hafensteiner BD. Short, Enantioselective total synthesis of stephacidin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:606–609. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baran PS, Hafensteiner BD, Ambhaikar NB, Guerrero CA, Gallagher JD. Enantioselective total synthesis of avrainvillamide and the stephacidins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8678–8693. doi: 10.1021/ja061660s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walton JC. Synthetic strategies for 5-and 6-membered ring azaheterocycles facilitated by iminyl radicals. Molecules. 2016;21:660–684. doi: 10.3390/molecules21050660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun X, Yu S. Visible-light-promoted iminyl radical formation from vinyl azides: synthesis of 6-(fluoro)alkylated phenanthridines. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:10898–10901. doi: 10.1039/C6CC05756J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka K, Kitamura M, Narasaka K. Synthesis of α-carbolines by copper-catalyzed radical cyclization of β-(3-indolyl) ketone O-pentafluorobenzoyloximes. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2005;78:1659–1664. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.78.1659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies J, Booth SG, Essafi S, Dryfe RAW, Leonori D. Visible-light-mediated generation of nitrogen-centered radicals: metal-free hydroimination and iminohydroxylation cyclization reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:14017–14021. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang H, et al. Visible-light-promoted iminyl-radical formation from acyl oximes: a unified approach to pyridines, quinolines, and phenanthridines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:4055–4059. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies J, Svejstrup TD, Fernandez Reina D, Sheikh NS, Leonori D. Visible-light-mediated synthesis of amidyl radicals: transition-metal-free hydroamination and N-arylation reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:8092–8095. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Z, Ren R, Zhu C. Combination of a cyano migration strategy and alkene difunctionalization: the elusive selective azidocyanation of unactivated olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:10821–10824. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larraufie MH, et al. Radical migration of substituents of aryl groups on quinazolinones derived from N-acyl cyanamides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4381–4387. doi: 10.1021/ja910653k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaume A, Courillon C, Derat E, Malacria M. Unprecedented aromatic homolytic substitutions and cyclization of amide/iminyl radicals: experimental and theoretical study. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:1238–1252. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Servais A, Azzouz M, Lopes D, Courillon C, Malacria M. Radical cyclization of N-acylcyanamides: total synthesis of luotonin A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:576–579. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Humphrey GR, Kuethe JT. Practical methodologies for the synthesis of indoles. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2875–2911. doi: 10.1021/cr0505270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taber DF, Tirunahari PK. Indole synthesis: a review and proposed classification. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:7195–7210. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leitch JA, Bhonoah Y, Frost CG. Beyond C2 and C3: transition-metal-catalyzed C–H functionalization of indole. ACS Catal. 2017;7:5618–5627. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b01785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inman M, Moody CJ. Indole synthesis–something old, something new. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:29–41. doi: 10.1039/C2SC21185H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiri M. Indoles in multicomponent processes (MCPs) Chem. Rev. 2012;112:3508–3549. doi: 10.1021/cr2003954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cacchi S, Fabrizi G. Update 1 of: synthesis and functionalization of indoles through palladium-catalyzed reactions. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:PR215–PR283. doi: 10.1021/cr100403z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer E, Jourdan F. Ueber die hydrazine der brenztraubensäure. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1883;16:2241–2245. doi: 10.1002/cber.188301602141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegedus LS, Allen GF, Waterman EL. Palladium assisted intramolecular amination of olefins. A new synthesis of indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:2674–2676. doi: 10.1021/ja00425a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larock RC, Yum EK. Synthesis of indoles via palladium-catalyzed heteroannulation of internal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:6689–6690. doi: 10.1021/ja00017a059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagaw S, Yang BH, Buchwald SL. A palladium-catalyzed strategy for the preparation of indoles: a novel entry into the fischer indole synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:6621–6622. doi: 10.1021/ja981045r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tokuyama H, Yamashita T, Reding MT, Kaburagi Y, Fukuyama T. Radical cyclization of 2-alkenylthioanilides: a novel synthesis of 2,3-disubstituted indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:3791–3792. doi: 10.1021/ja983681v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei Y, Deb I, Yoshikai N. Palladium-catalyzed aerobic oxidative cyclization of N-aryl imines: indole synthesis from anilines and ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:9098–9101. doi: 10.1021/ja3030824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, et al. A copper-catalyzed aerobic [1,3]-nitrogen shift through nitrogen-radical 4-exo-trig cyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:15436–15440. doi: 10.1002/anie.201709894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernini R, Fabrizi G, Sferrazza A, Cacchi S. Copper-catalyzed C−C bond formation through C−H functionalization: synthesis of multisubstituted indoles from N-aryl enaminones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:8078–8081. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu B, Song C, Sun C, Zhou S, Zhu J. Rhodium(III)-catalyzed indole synthesis using N–N bond as an internal oxidant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:16625–16631. doi: 10.1021/ja408541c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao D, Shi Z, Glorius F. Indole synthesis by rhodium(III)-catalyzed hydrazine-directed C-H activation: redox-neutral and traceless by N-N bond cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:12426–12429. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cui SL, Wang J, Wang YG. Synthesis of indoles via domino reaction of N-aryl amides and ethyl diazoacetate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13526–13527. doi: 10.1021/ja805706r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trost BM, McClory A. Rhodium-catalyzed cycloisomerization: formation of indoles, benzofurans, and enol lactones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2074–2077. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi Z, et al. Indoles from simple anilines and alkynes: palladium-catalyzed C-H activation using dioxygen as the oxidant. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:4572–4576. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fra L, Millán A, Souto JA, Muñiz K. Indole synthesis based on a modified koser reagent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:7349–7353. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang QQ, et al. Synthesis of indoles through highly efficient cascade reactions of sulfur ylides and N-(ortho-chloromethyl)aryl amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:9137–9140. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhuo CX, Wu QF, Zhao Q, Xu QL, You SL. Enantioselective functionalization of indoles and pyrroles via an in situ-formed spiro intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:8169–8172. doi: 10.1021/ja403535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang L, Dai LX, You SL. Enantioselective synthesis of indole-annulated medium-sized rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:5793–5796. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stokes BJ, Dong H, Leslie BE, Pumphrey AL, Driver TG. Intramolecular C−H amination reactions: exploitation of the Rh2(II)-catalyzed decomposition of azidoacrylates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7500–7501. doi: 10.1021/ja072219k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abbiati G, Marinelli F, Rossi E, Arcadi A. Synthesis of indole derivatives from 2-alkynylanilines by means of gold catalysis. Isr. J. Chem. 2013;53:856–868. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201300040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuart DR, Bertrand-Laperle M, Burgess KMN, Fagnou K. Indole synthesis via rhodium catalyzed oxidative coupling of acetanilides and internal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16474–16475. doi: 10.1021/ja806955s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Würtz S, Rakshit S, Neumann JJ, Dröge T, Glorius F. Palladium-catalyzed oxidative cyclization of N-aryl enamines: from anilines to indoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:7230–7233. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perea-Buceta JE, et al. Cycloisomerization of 2-alkynylanilines to indoles catalyzed by carbon-supported gold nanoparticles and subsequent homocoupling to 3,3′-biindoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:11835–11839. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allegretti PA, Huynh K, Ozumerzifon TJ, Ferreira EM. Lewis acid mediated vinylogous additions of enol nucleophiles into an α,β-unsaturated platinum carbene. Org. Lett. 2015;18:64–67. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qu C, Zhang S, Du H, Zhu C. Cascade photoredox/gold catalysis: access to multisubstituted indoles via aminoarylation of alkynes. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:14400–14403. doi: 10.1039/C6CC08478H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ilies L, Isomura M, Yamauchi S, Nakamura T, Nakamura E. Indole synthesis via cyclative formation of 2,3-dizincioindoles and regioselective electrophilic trapping. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;139:23–26. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watanabe T, Mutoh Y, Saito S. Ruthenium-catalyzed cycloisomerization of 2-alkynylanilides: synthesis of 3-substituted indoles by 1,2-carbon migration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:7749–7752. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b04564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maity S, Zheng N. A visible-light-mediated oxidative C-N bond formation/aromatization cascade: photocatalytic preparation of N-arylindoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:9562–9566. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Y, et al. Copper-catalyzed synthesis of multisubstituted indoles through tandem ullmann-type C–N formation and cross-dehydrogenative coupling reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2018;83:5288–5294. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.8b00353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ning XS, et al. Pd-tBuONO cocatalyzed aerobic indole synthesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018;360:1590–1594. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201701512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barluenga J, Jiménez-Aquino A, Aznar F, Valdés C. Modular synthesis of indoles from imines ando-dihaloarenes oro-chlorosulfonates by a Pd-catalyzed cascade process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4031–4041. doi: 10.1021/ja808652a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim JH, Lee S. Palladium-catalyzed intramolecular trapping of the blaise reaction intermediate for tandem one-pot synthesis of indole derivatives. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1350–1353. doi: 10.1021/ol200045q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clagg K, et al. Synthesis of indole-2-carboxylate derivatives via palladium-catalyzed aerobic amination of aryl C–H bonds. Org. Lett. 2016;18:3586–3589. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.For Cu-catalyzed intramolecular Ullmann-type cyclization: Melkonyan FS, Kuznetsov DE, Yurovskaya MA, Karchava AV. One-pot synthesis of substituted indoles via titanium(iv) alkoxide mediated imine formation–copper-catalyzed N-arylation. RSC Adv. 2013;3:8388–8397. doi: 10.1039/c3ra40389k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leardini R, McNab H, Minozzi M, Nanni D. Thermal decomposition of tert-butyl ortho-(phenylsulfanyl)- and ortho-(phenylsulfonyl)phenyliminoxyperacetates: the reactivity of thio-substituted iminyl radicals. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2001;1:1072–1078. doi: 10.1039/b009843o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li X, Fang X, Zhuang S, Liu P, Sun P. Photoredox catalysis: construction of polyheterocycles via alkoxycarbonylation/addition/cyclization sequence. Org. Lett. 2017;19:3580–3583. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leardini R, Nanni D, Pareschi P, Tundo A, Zanardi G. α-(Arylthio)imidoyl radicals: [3 + 2] radical annulation of aryl isothiocyanates with 2-cyano-substituted aryl radicals. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:8394–8399. doi: 10.1021/jo971128a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Asso V, et al. α-Naphthylaminopropan-2-ol derivatives as BACE1 inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:1530–1534. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang FX, Zhou SD, Wang C, Tian SK. N-hydroxy sulfonamides as new sulfenylating agents for the functionalization of aromatic compounds. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:5284–5288. doi: 10.1039/C7OB01390F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rahaman R, Barman P. Iodine-catalyzed mono- and disulfenylation of indoles in PEG400 through a facile microwave-assisted process. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017;42:6327–6334. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201701293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.He Y, Jiang J, Bao W, Deng W, Xiang J. TBAI-mediated regioselective sulfenylation of indoles with sulfonyl chlorides in one pot. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017;58:4583–4586. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.10.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yi S, et al. Metal-free, iodine-catalyzed regioselective sulfenylation of indoles with thiols. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016;57:1912–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.03.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sang P, Chen Z, Zou J, Zhang Y. K2CO3 promoted direct sulfenylation of indoles: a facile approach towards 3-sulfenylindoles. Green. Chem. 2013;15:2096–2100. doi: 10.1039/c3gc40724a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hamel P, Zajac N, Atkinson JG, Girard Y. Nonreductive desulfenylation of 3-indolyl sulfides. Improved syntheses of 2-substituted indoles and 2-indolyl sulfides. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:6372–6377. doi: 10.1021/jo00100a045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gastpar R, Goldbrunner M, Marko D, von Angerer E. Methoxy-substituted 3-formyl-2-phenylindoles inhibit tubulin Polymerization. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:4965–4972. doi: 10.1021/jm980228l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting this study are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information files.