Abstract

Background:

Interleukin-15 (IL-15) is a cytokine that is involved in many inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Although alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease, serum levels of IL-15 have not been studied well in AA patients.

Aim of the Work:

We aims at evaluating the serum levels of IL-15 in active AA.

Subject and Methods:

This case-control study included 40 AA patients and 40 apparently healthy matched controls. Written informed consents were obtained from all the participants. The scalp was examined to assess sites, number, and size of alopecia patches, and the severity of AA lesions was assessed using the Severity of Alopecia Tool score (SALT score) which determine the percentage of hair loss in the scalp. The body was carefully examined to detect any alopecia patches in any hairy area. Nail examination was carried out to detect any nail involvement. Serum IL-15 levels were measured using an ELISA kits.

Results:

Serum levels of IL-15 in patients were significantly higher than those in the control group (P < 0.001). Serum levels in alopecia totalis were significantly higher than those with one or two patches, and serum levels in patients with both scalp and body involvement were significantly elevated than the levels of patients with either scalp or body involvement. There was a statistically significant positive correlation between SALT score and serum levels of IL-15 (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Serum IL-15 may be a marker of AA severity.

Key words: Alopecia, alopecia severity, interleukin-15

INTRODUCTION

Hair follicle is an immune-privileged structure. This immune privilege (IP) is not restricted to the matrix only but also extending to include the bulge region protecting the hair stem cells.[1] There are multiple features which contribute to the ability of the hair bulb to escape the immune system reactions against self keratinocyte and/or melanocyte peptides.[2] These features include the downregulation of the natural-killer group 2, member D (NKG2D) receptors on CD8+ cytotoxic T cells as well as the NK cells, and the NKG2D ligand UL16-binding protein 3 (ULBP3).[3] NKG2D is a receptor found on the surface of NK cells, CD8+ T cells, and subsets of CD4+ T cells. Stimulation of this receptor by its ligands has a stimulatory effect on these cells.[4]

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease targeting the hair follicles, forming patches of noncicatricial hair loss in any hairy area in the body. It is commonly associated with other autoimmune diseases, among them; atopy and autoimmune thyroiditis are the most common.[5] The pathogenesis of AA is not completely clear yet, however, it is well-established that genetic and environmental factors contribute to its development.[6] Now, the autoimmune attack of the hair follicles due to the collapse of the IP of the anagen hair bulb is considered to play the main role in AA development.[7]

Interleukin-15 (IL-15) is a pleiotropic cytokine which exerts the multiple biological effects on different body cell types. It affects the functions of the cells of the immune system, both innate and adaptive, and hence, it has an important role during inflammation and during the immune responses to infections and infestations.[8] The role of IL-15 in the pathogenesis of AA was suggested when the blocking of IL-15 receptor beta (IL-15Rβ) reduced the number of CD8+NKG2D+ T cells in the skin and prevented the development of AA in the mouse model of the disease.[9]

This work aims at evaluating the serum levels of IL-15 in different clinical presentations of AA and assessing its relationship to clinical parameters of the diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This case-control study included 40 patients with different clinical variants of AA. In addition, 40 apparently healthy individuals of matched age and sex as a control group were included in the study.

The included patients were recruited from the dermatology clinic of the Dermatology Department. Written informed consents were obtained from all the participants. The study was approved by the ethics committee on research involving human participants and was in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki declaration of 1975. Patients with other hair disorders, including AA patients suffering from concomitant infectious, inflammatory or autoimmune cutaneous or systemic disease, and pregnant and lactating female patients were excluded from this study.

All patients were subjected to complete history taking and general examination. Scalp was examined to assess sites, number, and size of alopecia patches, and the severity of AA lesions was assessed using the Severity of Alopecia Tool score (SALT score) which determine the percentage of hair loss in the scalp.[10] The body was carefully examined to detect any alopecia patches in any hairy area. Nail examination was carried out to detect any nail involvement.

Blood sampling

Five milliliters of venous blood sample were collected from every participant in the study under complete aseptic precautions in the plain test tubes without anticoagulant. After coagulation, samples were centrifuged (at 1500 g for 15 min). The separated serum was aliquoted and stored at −20°C for subsequent assay of IL-15.

Serum levels of IL-15 were measured using the ELISA technique.

Quantification of interleukin-1

The test was carried out to quantify level of IL-15 in the sample. First microtiter plate was coated by purified human IL-15, then samples and standard were added to wells with a labeled antibody specific to IL-15, and then labeled horseradish peroxidase was added to the well. After washing completely, 3,3',5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate solution was added, TMB substrate became blue color in wells that contain antibody-antigen-enzyme-antibody complex, the reaction was terminated by the addition of a stop solution, and the color change was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm. The concentration of IL-15 in the samples is then determined by comparing the O. D. of the samples to the standard curve.

Statistical analysis of the data

Data were fed to the computer and analyzed using the IBM SPSS software package version 20.0. (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Qualitative data were described using number and percentage. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to verify the normality of distribution quantitative data were described using range (minimum and maximum), mean, standard deviation, and median. Significance of the obtained results was judged at the 5% level.

The used tests were Student's t-test for normally distributed quantitative variables, to compare between two studied groups and F-test (ANOVA) for normally distributed quantitative variables, to compare between more than two groups, and post-hoc test (Tukey) for pairwise comparisons. The Pearson's coefficient was used to correlate between two normally distributed quantitative variables, and Spearman's coefficient used to correlate between two distributed abnormally quantitative variables.

RESULTS

There was no statistically significant difference between patients and control participant's groups regarding sex (24 females vs. 20 females) and age (34.53 ± 10.23 vs. 34.47 ± 8.67), respectively.

History taking revealed that recurrence of the disease was reported by 21% of the patients, 38 patients had no family history of AA, and 15 patients only reported stress as a risk factor for AA development.

Results of examination are shown in Table 1. The mean SALT score in the studied patients was 21.39 ± 25.0.

Table 1.

Clinical findings in the studied patients and their correlation with IL-15 serum levels

| AA patches | n (%) | IL-15 | Test | P | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patches | |||||

| 1 | 17 (42.5) | 28.63±5.35 | F=11.323 | <0.001* |

F: ANOVA test #Excluded from the association due to small number of case (n=1)a Significant with 1b Significant with 2 |

| 2 | 12 (30.0) | 33.42±6.14 | |||

| 3 | 6 (15.0) | 38.23a±5.83 | |||

| 4 | 1# (2.5) | 41.73 | |||

| 6 | 1# (2.5) | 45.14 | |||

| Totalis | 2 (5.0) | 50.09a,b±1.01 | |||

| Universalis | 1# (2.5) | 54.94 | |||

| SALT score “scalp involvement (S)” (%) | |||||

| S0 (no hair loss) | 7 (17.5) | 28.24±3.88 | F=18.244 | <0.001* |

F: ANOVA testa Significant with 0b Significant with 1c Significant with 2 |

| S1 (<25 hair loss) | 13 (32.5) | 28.62±6.08 | |||

| S2 (25-49 hair loss) | 12 (30.0) | 35.41a,b±4.98 | |||

| S3 (50-74 hair loss) | 5 (12.5) | 41.87a,b±4.44 | |||

| S4 (75-99 hair loss) | 0 | - | |||

| S5 (100 hair loss) | 3 (7.5) | 51.71a,b,c±2.88 | |||

| Body involvement (B) (%) | |||||

| B0 (no body hair loss) | 25 (62.5) | 33.35±8.33 | t=0.097 | 0.923 | t: Student test |

| B1 (some body hair loss) | 14 (35.0) | 33.61±7.16 | |||

| B2 (100 body hair loss) | 1 (2.5) | 54.94 | |||

| Nail involvement (n) | |||||

| N0 (no nail involvement) | 40 (100.0) | 33.98±8.45 | |||

| N1 (some nail involvement) | 0 | - | |||

| Total involvement | |||||

| S0 Bn | 7 (17.5) | 28.24±3.88 | F=5.425 | 0.009* P1=0.273 P2=0.007* P3=0.048* |

F: ANOVA test P1: Comparison between S0 Bn and Sn B0 P2: Comparison between S0 Bn and Sn Bn P3: Comparison between Sn B0 and Sn Bn |

| Sn B0 | 25 (62.5) | 33.35±8.33 | |||

| Sn Bn | 8 (20.0) | 40.97±7.53 |

SALT – Severity of Alopecia Tool; AA – Although alopecia, *- Significant Difference

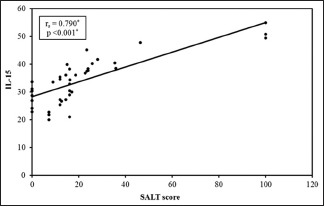

Serum levels of IL-15 in patients were significantly higher than those in the control group (33.98 ± 8.45 vs. 7.88 ± 1.86, respectively) (P < 0.001). Among the cases, serum levels in patients with alopecia totalis are significantly higher than those with one or two patches, and serum levels in patients with both scalp and body involvement were significantly elevated than levels of patients with either scalp or body involvement [Table 1]. There was a statistically significant positive correlation between SALT score and serum levels of IL-15 (P < 0.001) [Table 1 and Graph 1]. As shown in Table 2, gender, age, history of recurrence, family history, and stress as a risk factor did not seem to affect the serum levels of IL-15.

Graph 1.

Correlation between the Severity of Alopecia Tool score and interleukin-15 in the study group

Table 2.

Relation between interleukin-15 and demographic and history data

| IL-15 | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 34.03±7.34 | 0.046 | 0.964 |

| Female | 33.90±10.15 | ||

| Age | |||

| ≤34 | 31.72±8.68 | 1.832 | 0.075 |

| >34 | 36.48±7.65 | ||

| Recurrence | |||

| Negative | 32.31±9.02 | 1.191 | 0.241 |

| Positive | 35.48±7.81 | ||

| Family history | |||

| Negative | 34.29±8.56 | 1.019 | 0.314 |

| Positive | 28.05±1.23 | ||

| Stress | |||

| Negative | 32.61±8.82 | 1.335 | 0.190 |

| Positive | 36.26±7.52 |

P≤0.05 is significant. t – Student’s t-test. IL – Interleukin

DISCUSSION

AA is an autoimmune disease that presents as nonscarring hair loss patches. Any hairy area can be affected, but the scalp is the most commonly affected.[11] The exact pathogenesis of AA and the molecular mechanisms that lead to hair loss are not fully understood yet. However, it is now well-established that AA is an autoimmune inflammatory disease evoked by environmental factors in genetically predisposed patients. The collapse of the physiological state of anagen hair follicles immunoprivilege leading to perifollicular T-cell infiltrates and increase in inflammatory chemokines and cytokines may contribute to the disease development.[12]

IL-15 is a cytokine that plays a role in the innate and the adaptive immunity. In addition, it acts as a growth factor and promotes the survival of T, B, and NK cells by preventing apoptosis through the upregulation of anti-apoptotic and downregulation of pro-apoptotic factors. It is widely expressed by many cells.[13] It has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis,[14] SLE,[15] polymyositis, and dermatomyositis.[16] Its role in some dermatologic diseases has been investigated. Its expression in acute atopic dermatitis is decreased,[17] whereas it is highly expressed in psoriatic plaques[18] and in pustular palmoplantar psoriasis.[19]

IL-15 has an important role in the development, maintenance, and proliferation of memory CD8+ T cells, NK cells which are the main source of INF–γ[20] that is mainly responsible for IP collapse and the AA development.[21]

The results of the current work showed that serum levels of IL-15 were significantly higher in patients with AA when compared to the serum levels of the healthy controls. This was in disagreement with Barahmani et al.[22] who did not find a significant difference between the serum levels of patients and controls. This may be because 54% of their patients were atopic. In atopic dermatitis, Th2 cytokines (e.g., IL-4 and IL-13) and IgE are elevated, whereas Th1 cytokine, Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in the peripheral blood, and acute skin lesions are decreased.[23] In atopic dermatitis, the elevated IgE and the inflammatory reaction may be due to decreased IL-15.[24]

The higher serum levels of IL-15 in patients with alopecia totalis when compared to those with one or two patches, and the higher levels in patients with more scalp surface area involvement. Moreover, the concomitant involvement of the scalp and the body was associated with significantly higher levels of serum IL-15 than the solitary involvement of one of them. These findings could suggest IL-15 as a marker of the disease severity reflecting the severity of the inflammatory process. IL-15 has been found to be a marker of different diseases severity, including Stevens–Johnson Syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis,[25] preeclampsia,[26] and knee osteoarthritis.[27]

As elevated IL-15 expression has been reported in many inflammatory autoimmune diseases, there were clinical trials targeting IL-15 pathway using agents blocking the soluble IL-15 receptor α chain, mutant IL-15, and antibodies directed against the IL-15 cytokine and against the IL − 2R/IL-15Rβ subunit used by IL − 2 and IL-15.[28] Targeting the IL-15 receptor blocks delayed-type hypersensitivity.[29] Clinical trials suggested that targeting IL-15 pathway could be beneficial in the treatment of many diseases, including plaque psoriasis,[30] rheumatoid arthritis,[31] and vitiligo.[32] Regarding AA, Xing et al.[9] reported the improvement of AA on using JAK inhibitors. They suggested that these drugs exert their action through multiple mechanisms, including blocking of IL-15–triggered pSTAT5 activation and IL-15-induced upregulation of Granzyme B and IFN-γ expression. From all these findings, it seems that targeting IL-15 by biologic therapy could be a novel treatment for many inflammatory conditions in which IL-15 is involved. Serum IL-15 could be useful as a marker of AA activity and severity. Targeting this molecule may be a promising treatment for this disease.

CONCLUSION

IL-15 is significantly elevated in AA patients when compared to the control subjects. It is also positively correlated with the number and the extent of the disease, making it a possible marker of AA severity.

Financial support and sponsorship

This is an authors' own work. Laboratory investigations were done in clinical and chemical pathology laboratory.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meyer KC, Klatte JE, Dinh HV, Harries MJ, Reithmayer K, Meyer W, et al. Evidence that the bulge region is a site of relative immune privilege in human hair follicles. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1077–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang EHC, Yu M, Breitkopf T, Akhoundsadegh N, Wang X, Shi FT, et al. Identification of autoantigen epitopes in Alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:1617–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Berker D, Higgins CA, Jahoda C, Christiano AM. Biology of hair and nails. In: Jean B, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, editors. Dermatology. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. pp. 1081–99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanier LL. NKG2D receptor and its ligands in host defense. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:575–82. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seetharam KA. Alopecia areata: An update. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:563–75. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.116725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darwin E, Hirt PA, Fertig R, Doliner B, Delcanto G, Jimenez JJ, et al. Alopecia areata: Review of epidemiology, clinical features, pathogenesis, and new treatment options. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:51–60. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_99_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paus R, Bulfone-Paus S, Bertolini M. Hair follicle immune privilege revisited: The key to alopecia areata management. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2018;19:S12–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perera PY, Lichy JH, Waldmann TA, Perera LP. The role of interleukin-15 in inflammation and immune responses to infection: Implications for its therapeutic use. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:247–61. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, Cerise JE, Higgins CA, Gong W, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med. 2014;20:1043–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen EA, Hordinsky MK, Price VH, Roberts JL, Shapiro J, Canfield D, et al. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines – Part II. National alopecia areata foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:440–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasserman D, Guzman-Sanchez DA, Scott K, McMichael A. Alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:121–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertolini M, Uchida Y, Paus R. Toward the clonotype analysis of alopecia areata-specific, intralesional human CD8+T lymphocytes. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2015;17:9–12. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2015.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. Interleukin 15: Biology and relevance to human disease. Blood. 2001;97:14–32. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McInnes IB, Leung BP, Sturrock RD, Field M, Liew FY. Interleukin-15 mediates T cell-dependent regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med. 1997;3:189–95. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aringer M, Stummvoll GH, Steiner G, Köller M, Steiner CW, Höfler E, et al. Serum interleukin-15 is elevated in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:876–81. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.8.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiura T, Harigai M, Kawaguchi Y, Takagi K, Fukasawa C, Ohsako-Higami S, et al. Increased IL-15 production of muscle cells in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Int Immunol. 2002;14:917–24. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grewe M, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, Schöpf E, Thepen T, Langeveld-Wildschut AG, Ruzicka T, et al. A role for th1 and th2 cells in the immunopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Immunol Today. 1998;19:359–61. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rückert R, Asadullah K, Seifert M, Budagian VM, Arnold R, Trombotto C, et al. Inhibition of keratinocyte apoptosis by IL-15: A new parameter in the pathogenesis of psoriasis? J Immunol. 2000;165:2240–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lesiak A, Bednarski I, Pałczyńska M, Kumiszcza E, Kraska-Gacka M, Woźniacka A, et al. Are interleukin-15 and -22 a new pathogenic factor in pustular palmoplantar psoriasis? Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:336–9. doi: 10.5114/ada.2016.62838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vannucchi AM. From palliation to targeted therapy in myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1180–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1005856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azzawi S, Penzi LR, Senna MM. Immune privilege collapse and alopecia development: Is stress a factor. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4:236–44. doi: 10.1159/000485080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barahmani N, Lopez A, Babu D, Hernandez M, Donley SE, Duvic M, et al. Serum T helper 1 cytokine levels are greater in patients with alopecia areata regardless of severity or atopy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:409–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jujo K, Renz H, Abe J, Gelfand EW, Leung DY. Decreased interferon gamma and increased interleukin-4 production in atopic dermatitis promotes IgE synthesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:323–31. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(05)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong PY, Hamid QA, Travers JB, Strickland I, Al Kerithy M, Boguniewicz M, et al. Decreased IL-15 may contribute to elevated IgE and acute inflammation in atopic dermatitis. J Immunol. 2002;168:505–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su SC, Mockenhaupt M, Wolkenstein P, Dunant A, Le Gouvello S, Chen CB, et al. Interleukin-15 is associated with severity and mortality in Stevens-Johnson syndrome/Toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1065–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Baradie SM, Mahmoud M, Makhlouf HH. Elevated serum levels of interleukin-15, interleukin-16, and human chorionic gonadotropin in women with preeclampsia. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31:142–8. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun JM, Sun LZ, Liu J, Su BH, Shi L. Serum interleukin-15 levels are associated with severity of pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Dis Markers. 2013;35:203–6. doi: 10.1155/2013/176278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waldmann TA. Targeting the interleukin-15/interleukin-15 receptor system in inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:174–7. doi: 10.1186/ar1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim YS, Maslinski W, Zheng XX, Stevens AC, Li XC, Tesch GH, et al. Targeting the IL-15 receptor with an antagonist IL-15 mutant/Fc gamma2a protein blocks delayed-type hypersensitivity. J Immunol. 1998;160:5742–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villadsen LS, Schuurman J, Beurskens F, Dam TN, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Skov L, et al. Resolution of psoriasis upon blockade of IL-15 biological activity in a xenograft mouse model. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1571–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI18986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baslund B, Tvede N, Danneskiold-Samsoe B, Larsson P, Panayi G, Petersen J, et al. Targeting interleukin-15 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A proof-of-concept study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2686–92. doi: 10.1002/art.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richmond JM, Strassner JP, Zapata L, Jr, Garg M, Riding RL, Refat MA, et al. Antibody blockade of IL-15 signaling has the potential to durably reverse vitiligo. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:pii: eaam7710. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]