Abstract

Merkel cells (MCs) constitute a very unique population of postmitotic cells scattered along the dermo-epidermal junction. These cells that have synaptic contacts with somatosensory afferents are regarded to have a pivotal role in sensory discernment. Several concerns exist till date as to their origin, multiplication, and relevance in skin biology. The article, a collective review of literature extracted from PubMed search and dermatology books, provides novel insights into the physiology of MCs and their recent advances.

Keywords: Epidermis/embryology, epidermis/ultrastructure, human skin, keratins, mechanoreceptors, Merkel cell, mucosa, nerve endings/ultrastructure

Introduction

Merkel, a German histopathologist, provided the very first detailed account of Tastzellen which exist in the skin of vertebrates. They were later termed by Robert Bonnet as “Merkel cells.”[1] He considered them as conductors of physical stimuli as they were proximate to intraepidermal neurites. Merkel cells (MCs) are postmitotic cells that account for <5% of the total cell population in the epidermis.[2] The origin is still debated that whether they differentiate from epidermal keratinocyte-like cells or emerge from the migrated stem cells of neural crest origin.[2,3] The functions have been uncertain, but they seem to be involved in neural development and tactile sensation. The cells require ultrastructural methods for their identification as they are difficult to be observed in light microscopy.[4,5] This article provides a review on the current thinking, distribution, origin, function, demonstration, and fate of the human MCs.

History

Friedrich S Merkel (1875) construed Tastkörperchen and Tastzellen (pertaining to touch) in dermis of birds, oral mucosa, and mammalian epidermis. Considering them to be mechanoreceptors, they were later termed Merkel'sche Tastko¨rperchen and Merkel'sche Tastzellen.[6] Later, the cells were named as MCs and the similar cells that are devoid of contact to nerve terminals also came to be known by the same term.[5,7,8]

Anatomic Distribution

MCs are distributed in both skin and mucosal tissues, the density of which is increasingly noted in the palms, finger pads, feet, and plantar surface of the toes.[9,10] They are comparatively more in the oral mucosa.[11] MCs are also discerned in the male prepuce, clitoris, and esophagus.[12,13] MCs are more distributed in the skin exposed to sun than in concealed skin.[14] Histologically, they appear clear and oval, localized in the basal cell layer of the epidermis.[15]

In hair follicles, MCs are located either close to the bulge area or near the skin surface in the upper infundibulum. According to the ultrastructural studies, distinct groups of MCs are identified at diverse locations in the body.[16]

Origin

Since the discovery, the origin of MCs has remained controversial.[17] Various hypotheses are proposed concerning the development of MCs.

The first hypothesis namely neural crest cell (NCC) origin theory is that MCs are derivatives of NCC, since they can secrete neuropeptides and transcription factors (similar to the cells derived from neural crest), can be excited, and can express presynaptic features.[18] In addition, Halata et al. concluded from their researches on chimeric/avians that MCs originate from neural components.[2,19]

In the epidermis developed from the embryos that were deprived of neural precursors, Tweedle identified MCs.[20] Moll et al. observed the presence of MCs in human epidermis, grafted over the dermis of mice which were hampered of neural components.[15] The above researches support the epidermal origin theory that is also substantiated by the expression of keratins of simple epithelia such as CK8, CK18, and CK20 by MCs.[21] The cells are detectable from 8th week of intrauterine life, not in the dermis but within the suprabasal positions of the epidermis. The population increase exponentially in the subsequent weeks.[22,23] Since MCs are recognizable and transplantable several weeks before other NCC derivatives reach the fetal epidermis, it was proposed that MCs do not originate from NCCs.[15,22]

One unifying view is that there is premature migration of the MCs both from the neural crest and the epidermis during the 6th or 7th week of intrauterine life and that these cells subsequently only undergo further differentiation once in the epidermis.[2] Their differentiation from the pleuripotent cells is governed by the essential transcription factor Atoh1 (Factor atonal hemolog 1).[24]

Microscopy

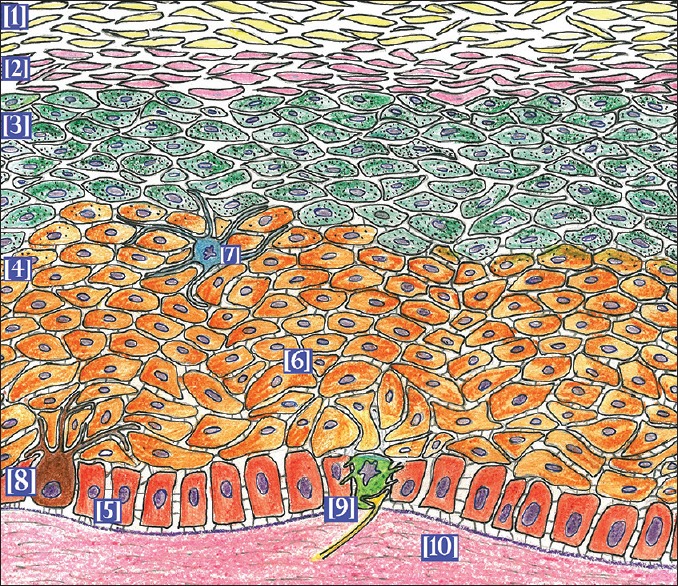

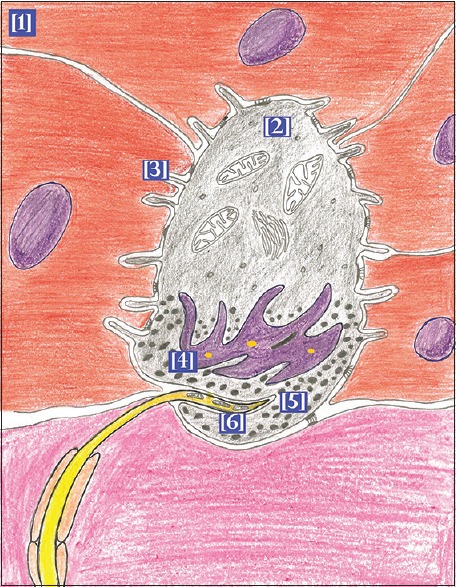

The morphologic description is figured principally by using electron microscopy. The cell is ovoid/elliptical, with length of about 10–15 μm. They exist in clusters at the stratum basale closely related to nerve endings[7] [Figure 1]. The surface has spine- or microvilli-like projections that number up to 50 and measure up to 2.5 μm in length.[9] They intertwine with the surrounding keratinocytes by comparatively small, few desmosomes.[25] The nucleus is large, pale, and lobulated with few nucleoli.[26] The most characteristic feature is the electron-dense granules in the cytoplasm, which is about 80–100 nm in diameter, surrounded by narrow electron-lucent spaces and bounded by simple membranes. They are situated away from the Golgi areas and are concentrated in the cytoplasmic areas closely associated with nerve terminations.[18] Intermediate filaments are discerned that may sometimes form tonofibril-like aggregates around the nucleus and neurofilaments.[26] Various zones of specialized synapses appose cytoplasmic membrane with axonal terminal.[27] Several dense core vesicles of about 50–110 nm are concentrated near the juncture with the nerve ending.[28] The MCs in apposition with the afferent sensory nerve endings is also referred to as Merkel's corpuscle/MC-neurite complex/Merkel ending.[26] The axon terminal (tactile meniscus) contains mitochondria and clear vesicles.[29] A single primary afferent type I nerve fiber innervates the complex.[2] Junctions between terminal axons and MCs are formed by adherens junctions/intermediate junctions/belt desmosomes.[30] The cells have a distinctive intranuclear rodlet and vesicles.[18] Sometimes, MCs contain melanosomes that are taken from the melanocytes similar to keratinocytes[31] [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Merkel cell in normal skin (1) Stratum corneum, (2) Stratum lucidum, (3) Stratum granulosum, (4) Stratum spinosum, (5) Stratum basale, (6) Keratinocyte, (7) Langerhans cell, (8) Melanocyte, (9) Merkel cell, (10) Dermis

Figure 2.

Merkels corpuscle (1) Keratinocyte, (2) Merkel cell, (3) Microvilli, (4) Lobulated nuclei with few nucleoli and intranuclear rodlet, (5) Dense core granules, (6) Tactile meniscus

Despite several neurosensitive components being identified by immunohistochemistry, the exact neurotransmitter in the Merkel's corpuscle could not be elucidated.[32] Since the oral mucosa, both in normalcy and pathology, displays numerous noninnervated MCs with secretory phenomena, it suggests that MCs have diverse subsets of cells with distinctive actions.[33]

Immunohistochemistry

MCs express both epithelial and neuroendocrine markers. The intermediate filaments stain positively for low-molecular-weight cytokeratins such as CK8, CK18, CK19, and CK20. CK20 is an active marker for those MCs in the normal skin.[9] However, cells of taste buds and various epithelia of the gastrointestinal tract also show CK20 positivity.[34,35]

Neuroendocrine immunohistochemical adjuncts such as chromogranin A, protein gene product 9.5, neuron-specific enolase, and synaptophysin are demonstrated.[7] The granules within the MCs are marked positive for opioid growth factor, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), somatostatin, pancreastatin, bombesin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), serotonin, Substance P(SP), glutamate, adenosine triphosphate, and enkephalin.[7,36]

Functions

Endocrine and nervous function

Endocrine function is attributed to the fact that the MC granules show striking features similar to the dense-core granules of amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation (APUD) system.[10] MCs located in the terminal hair follicles contain progenitor cells for both growth and regeneration of hair. It is presumed that they play a crucial role in the development of hair follicles and eccrine sweat glands.[37] Merkel's corpuscles may discharge endocrine constituents via autonomic neural regulation. A coexistence of MCs with Langerhans cells inside the bulge area of hair follicles is considered to be a putative reservoir of hair follicle stem cell.[38] Misery developed “Neuroimmunocutaneous system” concept where abundant cellular interactions occur amidst nerve fibers, immune cells, and epithelial cells permit molecular interactions by which functions of epidermal and dermal cells are moderated.[39] The immunohistochemical positivity for chromogranin A, Piccolo, cholecystokinin, Rab-3c, vesicular glutamate transporter 2 reflects the neuroendocrine character of MCs.[40,41] In the development of the subepidermal nerve plexus in the embryo, MCs are suggested to be involved.[42] Although it is hard to differentiate between the nervous and endocrine actions of MCs, it is recognized that they can perform both functions namely synthesis and storage of local hormones and neurotransmitters.[43]

Mechanotransduction function

Mechanotransduction refers to the conversion of mechanical energy into electric signals in the peripheral nervous system.[44] Recent researchers have revealed that MCs function as mechanical transducers, which produce impulses in the nerve endings via ionotropic receptors/ligand-gated ion channels. The somatosensory function of the MCs of palatine ridges is supported by the transduction through release of glutamate.[45] An increase in intracellular calcium concentration within the cells is recorded during mechanical stimulation.[46] Mechanical transduction function is validated by various electrophysiological data.[7] Gottschaldt andVahle-Hinz pointed out that the number of synapses is insufficient so as to generate action potential and hence it was the nerve endings themselves that functioned as transducers and not the MCs.[47] Positive immunohistochemical expression of anti-villin and Epsin antibodies in the micro villis of MCs validates the transduction property.[48,49] Researches by Woo et al. (2015) concluded that conduction of mechanical stimuli through Piezo 2 ion channels is fundamental for slowly adapting type 1 responses in cutaneous sensory nerve fibers.[50] García-Mesa et al. attributed the immunoreactivity to Peizo 2 to very fine and selective tactile perception but not to hard touch and vibration in afferent fibers.[44]

Nociceptive function

CGRP and SP released from Merkel's corpuscles are the active mediators for transferring nociceptive signals and are consistent in reaction to irritating substances.[51]

Solitary chemoreceptor cells (SCCs) are the specialized chemosensory cells in the olfactory epithelium that synapses with trigeminal afferent nerve fibers.[52] Functional studies indicate that they can detect inhaled noxious substances. Immunoreactivity for CK20 by both SCCs and MCs shows that they are correlated.[40]

Role in immunity and inflammation

CD200 protein, vital for inflammatory reactions and immune tolerance, is strongly expressed by MCs. Antigen presentation by Langerhans cells that reside in the stratum spinosum of epithelium is inhibited by CGRP produced by MCs. Met-enkephalin, VIP, and stomatin released by MCs are potent inflammatory mediators. Quantitative increase of MCs in psoriatic lesional skin signifies its role in cutaneous immunology.[53]

Presumptive functions

Though not widely accepted, the following roles are proposed, which can serve as a platform for further research. As MCs are dense within the epidermal ridges of nonhairy skin, they may be involved in fingerprint pattern. Electromagnetic fields for telekinesis may be generated by MCs on the basis of their efferent neural signaling capacity. The diverse distribution and neurocutaneous signaling may let MCs transduce environmental signals to oocytes so as to modify epigenetic imprinting. MCs are proposed to have magnetoreception property, i.e., production of a receptor potential due to movement of melanosome within changing electromagnetic field. This is hypothesized as MCs occasionally contain transferred melanosome which magnetize.[53,54]

Merkel Cell-Like Cells

MCs have a striking resemblance to the endocrine-paracrine (APUD) cells of the epithelium of the genitourinary tract and bronchial mucosa.[7,10,54] Adjacent to the MCs, in the basal layer of the epidermis and in the mucosa of ectodermal origin, pale ovoid cells with dense core granules with multiple nuclear pores on the oval nuclei are detected. Those cells lack contact with nerve terminals, have minimal intercellular junctions, and are devoid of cytoplasmic processes. In a single cell profile, the granules are adjacent to the Golgi complex in the apical surface rather than the basal surface.[7,55]

Apprehensible information regarding their function is incomplete, and it is obscure whether these cells have the same origin as that of MCs.[7]

Fate of Merkel Cells

MCs degenerate and are significantly reduced in number after denervation, but they never disappear completely.[56] They continue to survive in transplanted cutaneous flaps and their sustenance is strongly correlated with the recovery of the tactile sensation.[57]

Merkel Cells and Skin Lesions

Serum autoantibodies against MCs are described in graft-versus-host disease and pemphigus vulgaris. MCs are undetected in lesional skin of active vitiligo which points to their neural involvement or autoimmune destruction. MC hyperplasia along with keratinocyte hyperproliferation is a frequent histological finding in adnexal tumors namely trichoblastomas, sebaceous nevus, and hidradenomas.[2,58] The increased cell number is often encountered with hyperplasia of nerve terminals that exist in neurilemmoma, neurofibroma, prurigo nodularis, and lichen simplex chronicus.[2] MC carcinoma is a very rare, rapidly growing, cutaneous neuroendocrine malignancy encountered in head-and-neck region with propensity to recur and metastasize which is believed to be derived from MCs due to its similarity in histopathology.[59,60,61]

Conclusion

MCs are highly specialized nonkeratinocytes that are localized in touch-sensitive areas of the hairy and glabrous skin. It is still ambiguous whether the cellular origin is from epidermal elements or NCCs. They play pivotal roles in mechanoreceptor, neuro-endocrine, and nociceptive responses. Cells that are similar in morphology are identified, the exact functions of which are unclear. The cell proliferation is well documented in pathologies associated with neural and keratinocyte hyperplasia. Knowledge of the processes underlying MC specification will be relevant for a better understanding of the disease mechanisms implicated by the cells. It is very relevant in this era of high incidences of MC carcinoma that MCs should be explored in depth both functionally and phenotypically. Challenging and exciting years lay ahead of MC research community that can unveil the complex molecular mechanisms underpinning the human MC biology.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Erovic I, Erovic BM. Merkel cell carcinoma: The past, the present, and the future. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:929364. doi: 10.1155/2013/929364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGrath JA, Uitto J. Anatomy and organization of human skin. In: Burns T, editor. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 3.15–3.16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szeder V, Grim M, Halata Z, Sieber-Blum M. Neural crest origin of mammalian Merkel cells. Dev Biol. 2003;253:258–63. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowe R, Whitear M. Quinacrine fluorescence of Merkel cells in Xenopus laevis. Cell Tissue Res. 1978;190:273–83. doi: 10.1007/BF00218175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moll R, Moll I, Franke WW. Identification of Merkel cells in human skin by specific cytokeratin antibodies: Changes of cell density and distribution in fetal and adult plantar epidermis. Differentiation. 1984;28:136–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1984.tb00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szymonowicz L. Contributions to the knowledge of nerve ends in skin formations. Arch Mıcr Anat. 1895;45:624–53. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halata Z, Grim M, Bauman KI. Friedrich Sigmund Merkel and his “Merkel cell”, morphology, development, and physiology: Review and new results. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;271:225–39. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:107–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moll I, Roessler M, Brandner JM, Eispert AC, Houdek P, Moll R, et al. Human Merkel cells – Aspects of cell biology, distribution and functions. Eur J Cell Biol. 2005;84:259–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartschuh W, Grube D. The Merkel cell – A member of the APUD cell system.Fluorescence and electron microscopic contribution to the neurotransmitter function of the Merkel cell granules. Arch Dermatol Res. 1979;265:115–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00407875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boot PM, Rowden G, Walsh N. The distribution of Merkel cells in human fetal and adult skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:391–6. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmse JL, Carey FA, Baird AR, Craig SR, Christie KN, Hopwood D, et al. Merkel cells in the human oesophagus. J Pathol. 1999;189:176–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199910)189:2<176::AID-PATH416>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cold CJ, Taylor JR. The prepuce. Br J Urol. 1999;8:34–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacour JP, Dubois D, Pisani A, Ortonne JP. Anatomical mapping of Merkel cells in normal human adult epidermis. Br J Dermatol. 1991;125:535–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb14790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moll I, Lane AT, Franke WW, Moll R. Intra epidermal formation of Merkel cell in xenografts of human foetal skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;94:359–64. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12874488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eispert AC, Fuchs F, Brandner JM, Houdek P, Wladykowski E, Moll I, et al. Evidence for distinct populations of human Merkel cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;132:83–93. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boulais N, Misery L. Merkel cells. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:147–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winkelmann RK. The Merkel cell system and a comparison between it and the neurosecretory or APUD cell system. J Invest Dermatol. 1977;69:41–6. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12497864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halata Z, Grim M, Christ B. Origin of spinal cord meninges, sheaths of peripheral nerves, and cutaneous receptors including Merkel cells.An experimental and ultrastructural study with avian chimeras. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1990;182:529–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00186459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tweedle CD. Ultrastructure of Merkel cell development in aneurogenic and control amphibian larvae (Ambystoma) Neuroscience. 1978;3:481–6. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(78)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moll I, Paus R, Moll R. Merkel cells in mouse skin: Intermediate filament pattern, localization, and hair cycle-dependent density. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:281–6. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12340714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moll I, Moll R. Early development of human Merkel cells. Exp Dermatol. 1992;1:180–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1992.tb00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narisawa Y, Hashimoto K. Immunohistochemical demonstration of nerve-Merkel cell complex in fetal human skin. J Dermatol Sci. 1991;2:361–70. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(91)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Keymeulen A, Mascre G, Youseff KK, Harel I, Michaux C, De Geest N, et al. Epidermal progenitors give rise to Merkel cells during embryonic development and adult homeostasis. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:91–100. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polakovicova S, Seidenberg H, Mikusova R, Polak S, Pospisilova V. Merkel cells – Review on developmental, functional and clinical aspects. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2011;112:80–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tachibana T, Nawa T. Recent progress in studies on Merkel cell biology. Anat Sci Int. 2002;77:26–33. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-7722.2002.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen SY, Gerson S, Meyer J. The fusion of Merkel cell granules with a synapse-like structure. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;61:290–2. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12676510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iggo A, Muir AR. The structure and function of a slowly adapting touch corpuscle in hairy skin. J Physiol. 1969;200:763–96. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munger BL. The intraepidermal innervation of the snout skin of the opossum.A light and electron microscope study, with observations on the nature of Merkel's Tastzellen. J Cell Biol. 1965;26:79–97. doi: 10.1083/jcb.26.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe IS. Ultrastructures of mechanoreceptors in the oral mucosa. Anat Sci Int. 2004;79:55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-073x.2004.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toyoshima K, Seta Y, Nakashima T, Shimamura A. Occurrence of melanosome-containing Merkel cells in mammalian oral mucosa. Acta Anat (Basel) 1993;147:145–8. doi: 10.1159/000147495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tachibana T. The Merkel cell: Recent findings and unresolved problems. Arch Histol Cytol. 1995;58:379–96. doi: 10.1679/aohc.58.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tachibana T, Yamamoto H, Takahashi N, Kamegai T, Shibanai S, Iseki H, et al. Polymorphism of Merkel cells in the rodent palatine mucosa: Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Arch Histol Cytol. 1997;60:379–89. doi: 10.1679/aohc.60.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moll I, Kuhn C, Moll R. Cytokeratin 20 is a general marker of cutaneous Merkel cells while certain neuronal proteins are absent. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:910–5. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12606183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witt M, Kasper M. Distribution of cytokeratin filaments and vimentin in developing human taste buds. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1999;199:291–9. doi: 10.1007/s004290050229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang W, Kanda H, Ikeda R, Ling J, DeBerry JJ, Gu JG, et al. Merkel disc is a serotonergic synapse in the epidermis for transmitting tactile signals in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E5491–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1610176113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim DK, Holbrook KA. The appearance, density, and distribution of Merkel cells in human embryonic and fetal skin: Their relation to sweat gland and hair follicle development. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;104:411–6. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12665903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taira K, Narisawa Y, Nakafusa J, Misago N, Tanaka T. Spatial relationship between Merkel cells and Langerhans cells in human hair follicles. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(02)00104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Misery L. Neuro-immuno-cutaneous system (NICS) Pathol Biol (Paris) 1996;44:867–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lucarz A, Brand G. Current considerations about Merkel cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2007;86:243–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haeberle H, Fujiwara M, Chuang J, Medina MM, Panditrao MV, Bechstedt S, et al. Molecular profiling reveals synaptic release machinery in Merkel cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14503–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406308101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Narisawa Y, Hashimoto K, Nihei Y, Pietruk T. Biological significance of dermal Merkel cells in development of cutaneous nerves in human fetal skin. J Histochem Cytochem. 1992;40:65–71. doi: 10.1177/40.1.1370310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maksimovic S, Nakatani M, Baba Y, Nelson AM, Marshall KL, Wellnitz SA, et al. Epidermal Merkel cells are mechanosensory cells that tune mammalian touch receptors. Nature. 2014;509:617–21. doi: 10.1038/nature13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.García-Mesa Y, García-Piqueras J, García B, Feito J, Cabo R, Cobo J, et al. Merkel cells and Meissner's corpuscles in human digital skin display piezo2 immunoreactivity. J Anat. 2017;231:978–89. doi: 10.1111/joa.12688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nunzi MG, Pisarek A, Mugnaini E. Merkel cells, corpuscular nerve endings and free nerve endings in the mouse palatine mucosa express three subtypes of vesicular glutamate transporters. J Neurocytol. 2004;33:359–76. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000044196.45602.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tazaki M, Suzuki T. Calcium inflow of hamster Merkel cells in response to hyposmotic stimulation indicate a stretch activated ion channel. Neurosci Lett. 1998;243:69–72. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gottschaldt KM, Vahle-Hinz C. Merkel cell receptors: Structure and transducer function. Science. 1981;214:183–6. doi: 10.1126/science.7280690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toyoshima K, Seta Y, Takeda S, Harada H. Identification of Merkel cells by an antibody to villin. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:1329–34. doi: 10.1177/002215549804601113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sekerková G, Zheng L, Loomis PA, Changyaleket B, Whitlon DS, Mugnaini E, et al. Espins are multifunctional actin cytoskeletal regulatory proteins in the microvilli of chemosensory and mechanosensory cells. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5445–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1279-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woo SH, Lumpkin EA, Patapoutian A. Merkel cells and neurons keep in touch. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tachibana T, Endoh M, Nawa T. Immunohistochemical expression of G protein alpha-subunit isoforms in rat and monkey Merkel cell-neurite complexes. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;116:205–13. doi: 10.1007/s004180100318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gulbransen BD, Finger TE. Solitary chemoreceptor cell proliferation in adult nasal epithelium. J Neurocytol. 2005;34:117–22. doi: 10.1007/s11068-005-5051-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xiao Y, Williams JS, Brownell I. Merkel cells and touch domes: More than mechanosensory functions? Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:692–5. doi: 10.1111/exd.12456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Irmak MK. Multifunctional Merkel cells: Their roles in electromagnetic reception, finger-print formation, Reiki, epigenetic inheritance and hair form. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75:162–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tachibana T, Kamegai T, Takahashi N, Nawa T. Evidence for polymorphism of Merkel cells in the adult human oral mucosa. Arch Histol Cytol. 1998;61:115–24. doi: 10.1679/aohc.61.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.English KB. The ultrastructure of cutaneous type I mechanoreceptors (Haarscheiben) in cats following denervation. J Comp Neurol. 1977;172:137–63. doi: 10.1002/cne.901720107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vesper M, Houdek P, Moll I. Merkel cells in human transplanted flaps. In: Baumann K, editor. The Merkel Cell: Structure-Development-Function-Cancerogenesis. 1st ed. The Merkel Cell: Structure-Development-Function-Cancerogenesis; 2003. pp. 25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sidhu GS, Chandra P, Cassai ND. Merkel cells, normal and neoplastic: An update. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2005;29:287–94. doi: 10.1080/01913120590951284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang TS, Byrne PJ, Jacobs LK, Taube JM. Merkel cell carcinoma: Update and review. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maugeri R, Giugno A, Giammalva RG, Gulì C, Basile L, Graziano F, et al. Athoracic vertebral localization of a metastasized cutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma: Case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:190. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_70_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Müller-Richter UD, Gesierich A, Kübler AC, Hartmann S, Brands RC. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Recommendations for diagnostics and treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3430–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5993-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]