Abstract

Patients with diabetes often develop gastrointestinal motor problems, including gastroparesis. Previous studies have suggested this gastric motor disorder was a consequence of an enteric neuropathy. Disruptions in interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) have also been reported. A thorough examination of functional changes in gastric motor activity during diabetes has not yet been performed. We comprehensively examined the gastric antrums of Lepob mice using functional, morphological, and molecular techniques to determine the pathophysiological consequences in this type 2 diabetic animal model. Video analysis and isometric force measurements revealed higher frequency and less robust antral contractions in Lepob mice compared with controls. Electrical pacemaker activity was reduced in amplitude and increased in frequency. Populations of enteric neurons, ICC, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor α+ cells were unchanged. Analysis of components of the prostaglandin pathway revealed upregulation of multiple enzymes and receptors. Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase-2 inhibition increased slow wave amplitudes and reduced frequency of diabetic antrums. In conclusion, gastric pacemaker and contractile activity is disordered in type 2 diabetic mice, and this appears to be a consequence of excessive prostaglandin signaling. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis may provide a novel treatment for diabetic gastric motility disorders.

Introduction

Diabetes is often accompanied by gastrointestinal (GI) motility dysfunction (1). The gastric complications of diabetes are frequently attributed to an enteric neuropathy, primarily due to loss or reduced expression of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS1) inhibitory neurons (2,3). Conversely, reduced populations of excitatory enteric neurons have also been reported (4). Disruption of gastric interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) has also been reported in animal models of diabetes (5,6) and in human patients (7,8). Studies have shown that ICC are the GI pacemaker cells that generate electrical slow waves that underlie phasic contractions throughout the GI tract (9–11). These cells also act as intermediaries in enteric neuroeffector transmission (12,13). Thus, defects or loss of ICC may be involved in the pathological motor activities in gastroparesis. Aberrant electrical activity (5), development of delayed gastric emptying, and loss of ICC have been observed concomitantly in animal models of diabetes (14,15). In contrast, an increase, rather than a decrease, in gastric emptying has been observed in ∼20% of patients with diabetes (16). Recently, an increase in gastric ICC numbers and increased cholinergic motor responses have been detected in female Leprdb mice, and these changes were associated with accelerated gastric emptying (17). Overall, the pathogenesis of the GI motor complications of diabetes remains poorly understood, and there is a paucity of studies examining changes in ICC, enteric neurons, and the functional deficits associated with type 2 diabetes.

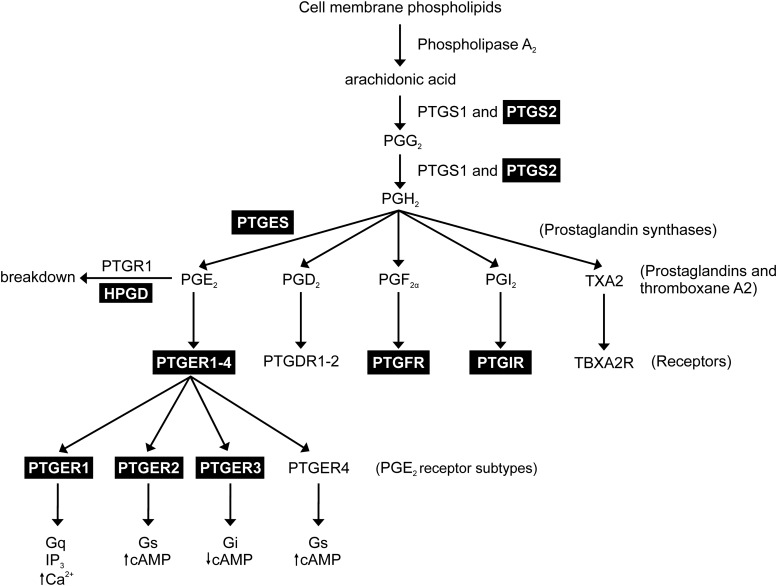

Prostaglandins are biologically active lipid derivatives of arachidonic acid that are synthesized in GI muscles (18). Arachidonic acid is liberated from membrane phospholipids by phospholipase A2 and subsequently converted to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) by the prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase (PTGS) enzymes (also known as cyclooxygenases). Two isoforms of PTGS exist: PTGS1 and PTGS2. PTGS1 is constitutively expressed, whereas PTGS2 expression is generally low under normal conditions but can be induced by inflammation (19). However, constitutive expression of PTGS2 has been observed in intramuscular ICC (ICC-IM) and enteric neurons of the GI tract (20,21). PGH2 is then converted to various prostaglandins and thromboxane (i.e., PGE2, PGD2, PGF2α, PGI2, and thromboxane A2; see Fig. 7) by several specific prostaglandin synthase enzymes (22). For example, PGE2 is produced by microsomal PGE2 synthase (PTGES or mPGES). Like PTGS, there are multiple isoforms of this enzyme (PTGES, PTGES2, and PTGES3), of which PTGES2 and PTGES3 are constitutively expressed and PTGES is induced by inflammatory mediators (19).

Figure 7.

Diagram depicting the prostanoid synthesis pathway and the effects of PGE2 on its receptor subtypes. Highlighted boxes identify prostaglandin-related genes that are upregulated in the gastric antrums of Lepob tissues. We hypothesize that upregulation of PTGES, encoding microsomal PGE2 synthase, results in increased levels of PGE2, which in turn results in abnormal antral slow wave and contractile activity. The PTGER1–3 receptors are also upregulated and likely play a role in the altered gastric motor activity. IP3, inositol triphosphate.

Endogenous prostaglandins (particularly PGE2) affect gastric motility. PGE2 affects pacemaker activity in the antrum by increasing the frequency and decreasing the amplitude of slow waves (23,24). PGE2 also inhibits phasic contractions in the antrum but enhances contractile tone in the proximal stomach (20,23). Consequently, this disrupts the coordination of gastric peristalsis in intact muscles (24). The effects of PGE2 on antral activity are absent in W/Wv mice, which lack gastric ICC-IM, suggesting that these effects are mediated by receptors on ICC-IM (24). The chronotropic receptor expressed by ICC is the EP3 subtype (PTGER3) (24,25).

We investigated gastric electrical and mechanical activities of Lepob mice and observed that the abnormal patterns of activity were similar to behaviors caused by PGE2 administration. Therefore, we investigated the hypothesis that the gastric motor abnormalities seen in this diabetic animal model might be related to overproduction of PGE2, working through receptors in ICC that affect pacemaker activity. We used immunohistochemical, molecular, and functional approaches to characterize enteric nerves, interstitial cell populations, and changes in the molecules that enhance PGE2 signaling and characterize electromechanical patterning of gastric muscles of Lepob mice. Our results show that Lepob mice have slow waves of increased frequency and decreased amplitude. Areas of antrum were found with no resolvable pacemaker activity, and these electrical anomalies were associated with abnormal contractile patterns. We also found increased expression of specific components of the prostaglandin pathway, including PTGES1 and PGE2 receptors, which may underlie the observed changes in gastric motility patterns.

Research Design and Methods

Animals

Lepob diabetic mice and wild-type littermates (C57BL/6) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Lepob mice (8–10 weeks old) had greater weights: 48 ± 3 g (n = 6) vs. 23 ± 1 g for wild-types (n = 5; P ≤ 0.0001). Animals were anesthetized by isoflurane (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) and exsanguinated after cervical dislocation. Blood glucose was measured from tail tips using an Ascensia-Contour Blood Glucose Monitoring System (Bayer HealthCare LLC, Mishawaka, IN). Lepob mice were hyperglycemic, 256 ± 30 mg/dL (n = 15) vs. 154 ± 7 mg/dL for wild-type mice (n = 10; P = 0.014). Stomachs from age-matched Lepob mice and wild-type controls were removed and opened along the lesser curvature, and the antral mucosa removed by sharp dissection. All experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at the University of Nevada, Reno approved procedures.

Electrophysiological Measurements

Antral muscles were pinned to the Sylgard elastomer floor of a recording chamber and perfused with 37°C Krebs-Ringer buffer. Circular muscle cells were impaled with KCl-filled glass microelectrodes (50–100 MΩ). Transmembrane potentials were measured using an amplifier (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA) and digitized (Digidata 1300 series; Axon Instruments). Slow waves were recorded from nine mapped regions of each antrum. Measurements of resting membrane potential (RMP), amplitude, frequency, half-maximal duration, and interslow wave period (ISWP) were made using Clampfit 10.0 (Axon Instruments).

Postjunctional neural responses were recorded in response to electrical field stimulation (0.3-ms pulse duration, 1–20 Hz, train durations of 1 s, 10–15 V) delivered by a Grass S48 stimulator (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA).

Isometric Force Measurements

Standard isometric force measurements were performed as previously described (20). Details are provided in the Supplementary Data.

Video Imaging of Gastric Peristalsis

Motility patterns of antrums were recorded as previously described (24). Specific details are provided in the Supplementary Data.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry of whole-mount gastric preparations was performed as previously described (26). Specific details are provided in the Supplementary Data and Supplementary Table 1 for antibodies used.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed using standard techniques and as previously described (27). Details are provided in the Supplementary Data.

RNA Isolation and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR (qPCR) performed using standard techniques (28). Details are provided in the Supplementary Data.

Solutions and Drugs

Details of solutions and drugs used are described in the Supplementary Data.

Statistical Analysis

Standard statistical analysis was performed using appropriate statistical tests. Details are described in the Supplementary Data.

Results

Disruption of Pacemaker Activity in Gastric Antrums of Lepob Diabetic Animals

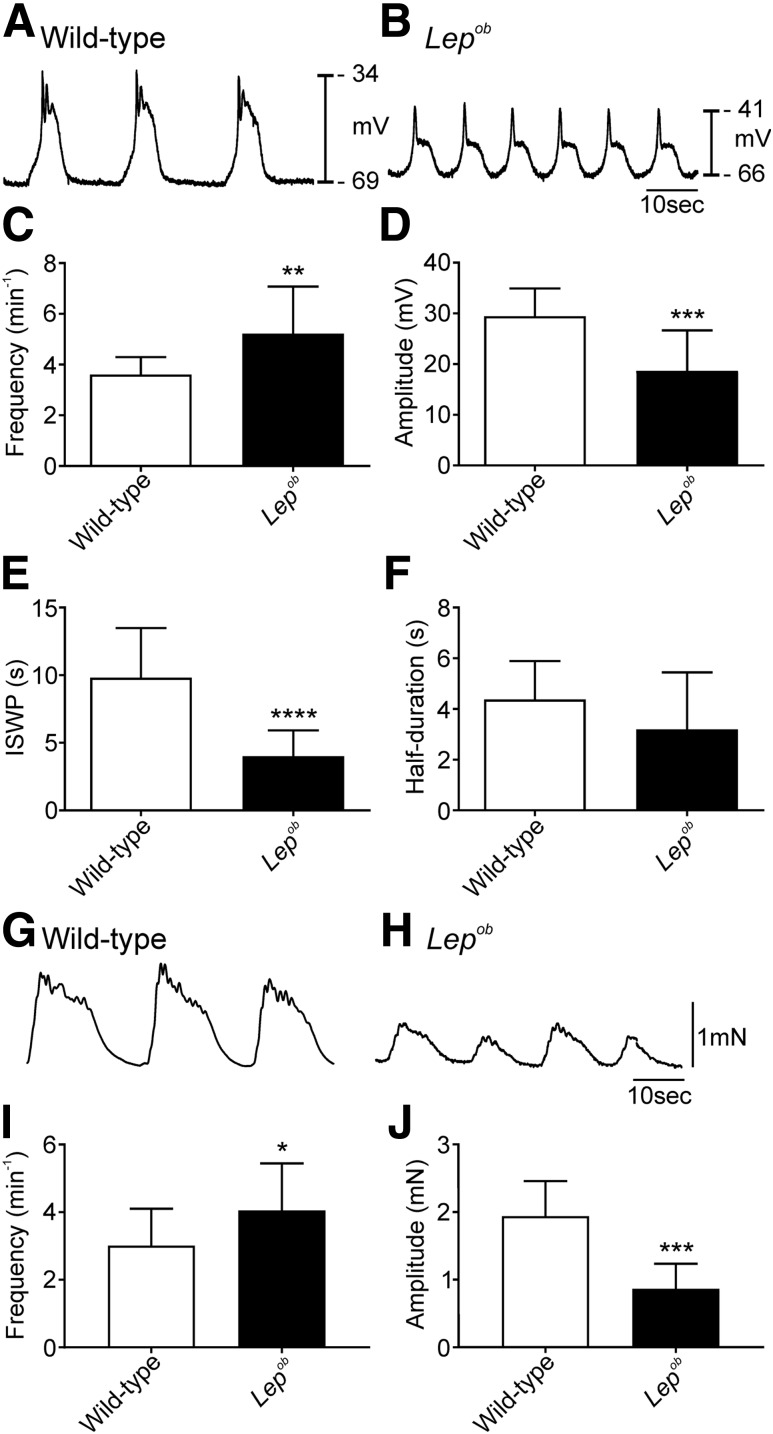

The RMP for gastric antrums of wild-type mice averaged −66 ± 4.0 mV (n = 14), whereas the antrums of Lepob mice were significantly depolarized at −60 ± 5.0 mV (n = 16; P = 0.001). Slow waves occurred in wild-type antrums with a frequency of 3.6 ± 0.7 min−1 (Fig. 1A and C) (n = 14), but the frequency of slow waves was increased in Lepob antral muscles to 5.2 ± 1.9 min−1 (Fig. 1B and C) (n = 16; P = 0.0049). Slow waves from wild-type mice had an average amplitude of 29 ± 6.0 mV (Fig. 1A and D) (n = 14) but were only 19 ± 8 mV in Lepob antral muscles (Fig. 1B and D) (n = 16; P = 0.0002). The ISWP was 9.8 ± 3.7 s in wild-type mice (Fig. 1A and E) (n = 14) and significantly reduced to 4 ± 1.9 s in Lepob mice (Fig. 1B and E) (n = 14; P < 0.0001). The half-duration of slow waves in wild-type (4.4 ± 1.5 s) (Fig. 1A and F) (n = 14) and Lepob antral muscles (3.2 ± 2.3 s) (Fig. 1B and F) was not significantly different (n = 16; P = 0.1085). Of the 16 Lepob antrums studied, 2 had slow wave frequencies, and 4 had amplitudes that were not different from the average values of slow waves in wild-type mice. All animals were included in the analysis of electrical parameters.

Figure 1.

Frequency of pacemaker activity was greater, and amplitude reduced, in Lepob antrums. Representative intracellular microelectrode recordings from the antrums of wild-type (A) and Lepob (B) mice. Note the depolarized membrane potential, increased frequency, and decreased amplitude of slow waves in Lepob antrums. Time scale in B applies to both A and B. C–F: Summarized data demonstrating differences in slow wave parameters between wild-type (white bars) and Lepob antrums (black bars). Increase in slow wave frequency (C), reduction in slow wave amplitude (D), reduction in ISWP (E), and reduction in half-maximal duration of slow waves (F) (unpaired Student t test). Representative isometric force recordings from the antrums of wild-type (G) and Lepob (H) mice. Summarized data showing increased frequency (I) and reduced amplitude (J) of contractions in Lepob, as compared with wild-type (unpaired Student t test). *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001; ****P ≤ 0.0001.

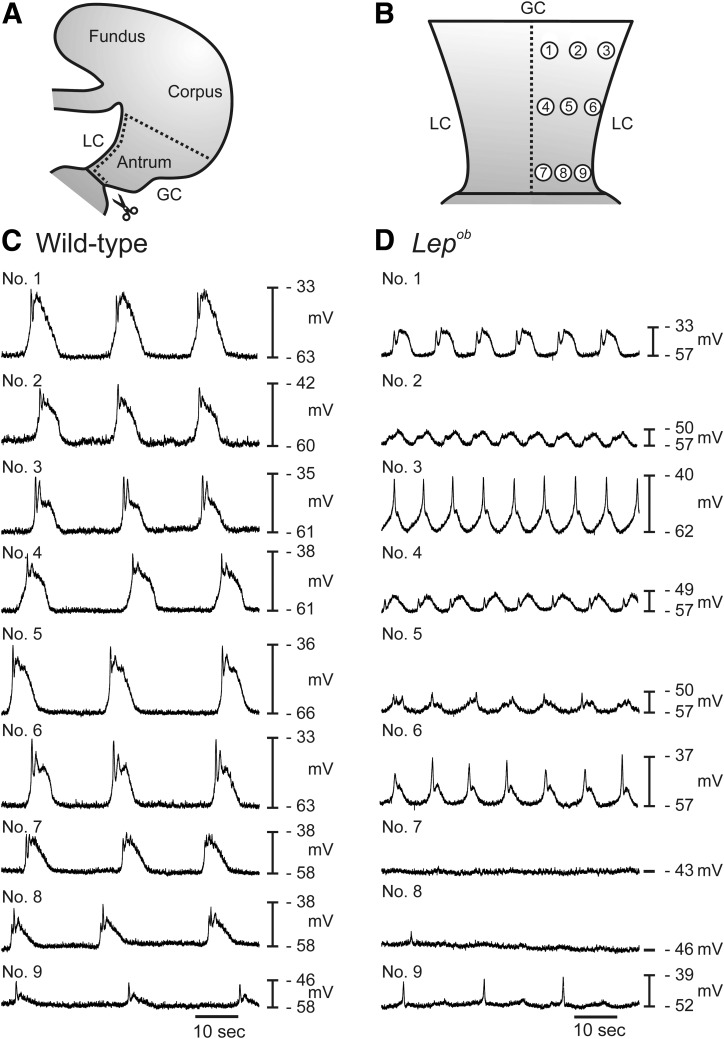

Intracellular recordings were made at nine specific regions along the antral wall from greater to lesser curvature to determine if the disruption in slow wave activity was widely distributed or a localized occurrence. Figure 2A and B shows a diagrammatic representation of the preparation and the location of each recording site. Typical slow waves from each region are shown in Fig. 2C and D. In the gastric antrums of wild-type animals, slow waves tended to have reduced amplitudes in the distal antrum compared with proximal regions (compare regions 7–9 with regions 1–3 in Fig. 2C). The slow wave pattern was more heterogeneous in Lepob antrums, with some regions (e.g., regions 7 and 8) displaying an absence of slow waves (Fig. 2D). Summary data reveal significantly increased slow wave frequencies and reduced amplitudes in numerous antral regions (Supplementary Fig. 3). Means ± SD from the nine recorded regions are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Figure 2.

Mapping of pacemaker activity throughout the antrums of wild-type and Lepob animals. A and B: Diagrammatic illustrations showing the gastric antrum muscle preparation and the regions from which electrical recordings were obtained. A: Antrums were separated from intact stomachs and opened along the lesser curvature (LC). B: Isolated antrums were pinned flat, the mucosa removed, and intracellular microelectrode recordings made from proximal antrum (regions 1–3), mid antrum (regions 4–6), and the terminal antrum (regions 7–9). Typical electrical activity recorded from the circular muscle layers of each of the nine regions of wild-type (C) and Lepob antrums (D). Note that membrane potentials were more depolarized and pacemaker activity was higher in frequency and decreased in amplitude in Lepob antrums compared with wild-type controls. In two regions of the Lepob antrum, no slow wave activity was recorded. GC, greater curvature.

Postjunctional Neural Responses in Gastric Antrums of Lepob Animals

We recorded postjunctional neural responses to electrical field stimulation of intrinsic neurons in wild-type and Lepob antrums. No significant differences were observed in responses at 1 and 10 Hz (see Supplementary Data and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Antral Mechanical Activity Is Decreased and Motility Is Disordered in Lepob Diabetic Mice

Isometric force measurements revealed that phasic contractions of Lepob antrums were reduced in amplitude and increased in frequency in comparison with antral muscles of wild-type mice. Circular muscle contractions occurred at 3.0 ± 1.1 min−1 (Fig. 1G and I) (n = 15) and generated 1.9 ± 0.51 mN of force in wild-type muscles (Fig. 1G and J) (n = 8). Contractions of Lepob antrums occurred at 4.1 ± 1.4 min−1 (Fig. 1H and I) (n = 14; P = 0.033) and generated significantly less force (0.85 ± 0.37 mN) (Fig. 1H and J) (n = 9; P ≤ 0.001).

Video imaging of antral muscles from wild-type or Lepob mice was also performed to determine changes in motility patterns (Supplementary Fig. 1A–C). Spatiotemporal maps were produced from video recordings (Supplementary Fig. 1D and E). Wild-type antral muscles demonstrated robust regular contractions at a frequency of 4 min−1 (Supplementary Fig. 1D). This activity was weakened, irregular, and occurred at a higher frequency of 5.5 min−1 in Lepob antrums (Supplementary Fig. 1E).

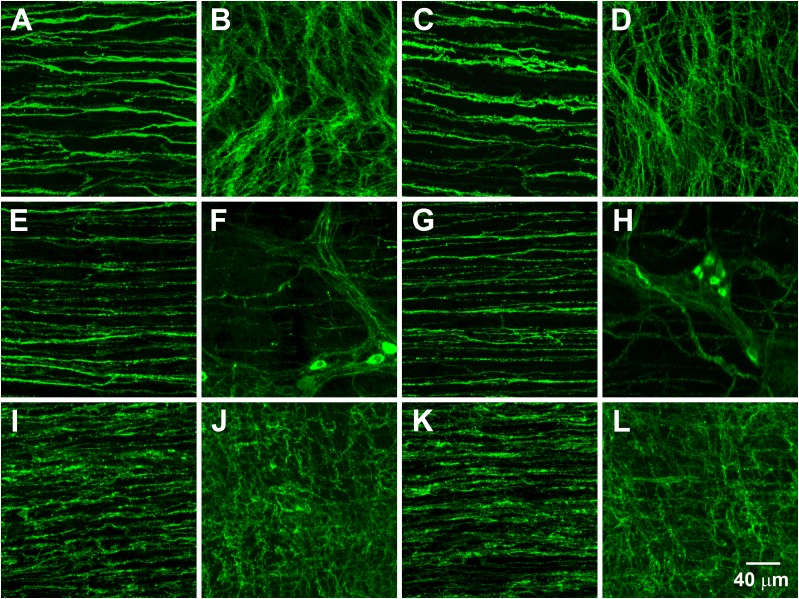

ICC Networks, NOS1+ Nerves, and PDGFRα+ Cells in Wild-Type and Lepob Mice

Images from the greater curvature are presented in Fig. 3. Supplementary Fig. 4 shows images from the lesser curvature. No differences were observed in ICC at the level of the myenteric plexus (ICC-MY) between wild-type (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 4B) (n = 7) and Lepob mice (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Fig. 4D) (n = 10) and ICC-IM in wild-type (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Fig. 4A) (n = 7) and Lepob antrums (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. 4C) (n = 10). Likewise, no differences were detected in the densities of NOS1+ nerve fibers in the circular muscle layer of wild-type (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. 4E) (n = 3) and Lepob mice (Fig. 3G and Supplementary Fig. 4G) (n = 6). NOS1+ neurons were also unchanged in the myenteric plexus of antrums of wild-type (Fig. 3F and Supplementary Fig. 4F) (n = 3) and Lepob mice (Fig. 3H and Supplementary Fig. 4H) (n = 6).

Figure 3.

Networks of ICC, NOS1+ nerves, and PDGFRα+ cells along the greater curvature of antrums from wild-type and Lepob animals. Representative images of ICC (A–D), NOS1+ neurons (E–H), and PDGFRα+ cells (I–L). A, E, and I show ICC, NOS1+ nerve fibers, and PDGFRα+ cells, respectively, within the circular muscle layer of a wild-type antrum. B, F, and J show ICC, NOS1+ neurons, and PDGFRα+ cells, respectively, in the myenteric plexus region of a wild-type antrum. C, G, and K show ICC, NOS1+ nerve fibers, and PDGFRα+ cells, respectively, within the circular muscle layer of a Lepob antrum. D, H, and L show ICC, NOS1+ neurons, and PDGFRα+ cells, respectively, in the myenteric plexus region of a Lepob antrum. Scale bar in L applies to all panels.

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor α+ (PDGFRα+) cells had similar densities in antral circular muscles of wild-type (Fig. 3I and Supplementary Fig. 4I) (n = 5) and Lepob mice (Fig. 3K and Supplementary Fig. 4K) (n = 4). No differences in PDGFRα + cells were detected in the myenteric region either (Fig. 3J and Supplementary Fig. 4J, n = 5; Fig. 3L and Supplementary Fig. 4L, n = 4).

Protein Expression in ICC, Enteric Neurons, and Smooth Muscle in Wild-Type and Lepob Mice

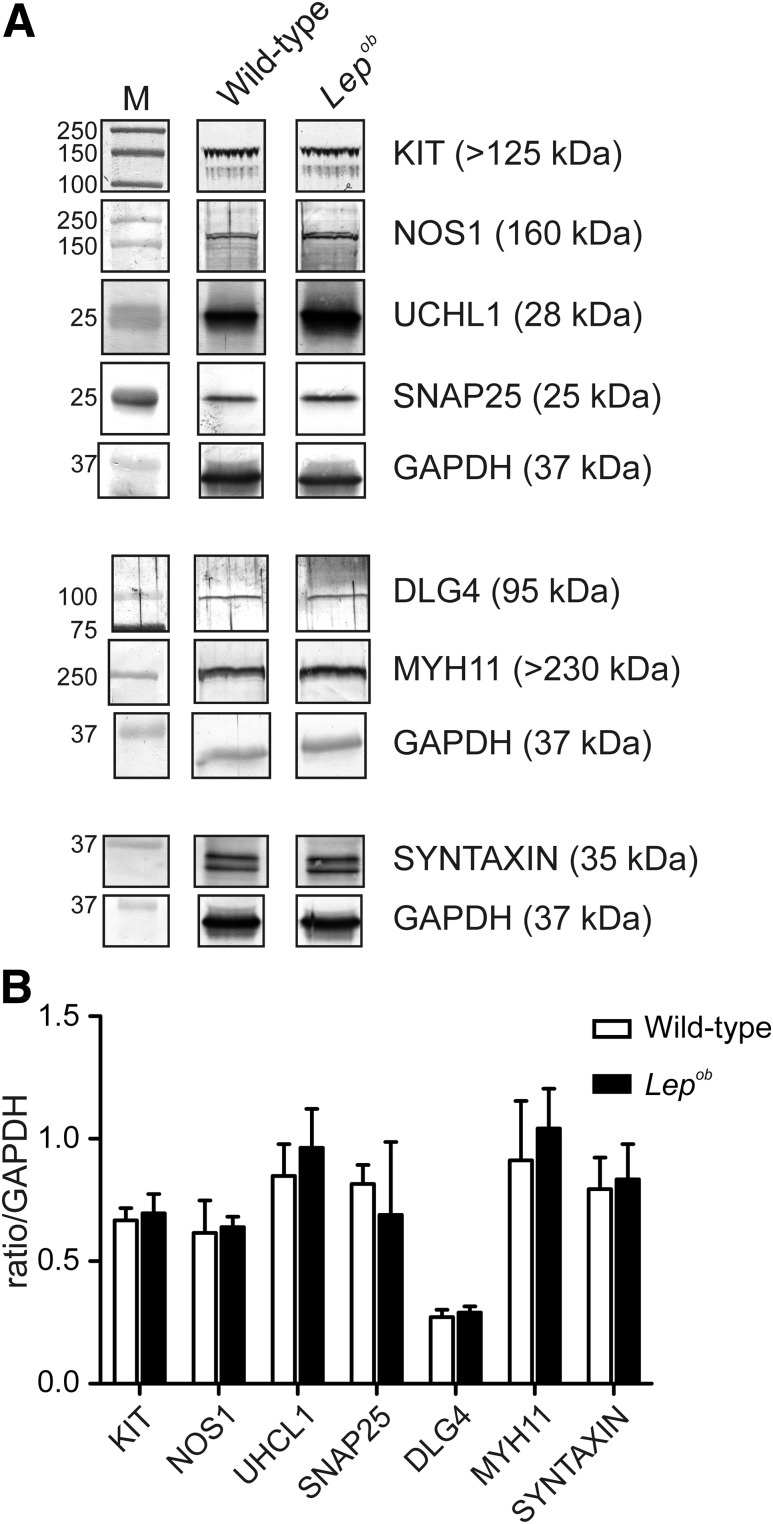

Western blot analysis was performed to quantify possible changes in cell-specific proteins expressed in ICC (KIT), enteric neurons (NOS1 and UCHL1), smooth muscle (MYH11), and in pre- and postsynaptic proteins (SNAP25, syntaxin, and DLG4). No significant differences were observed in any of these proteins between wild-type (n = 4) and Lepob antrums (n = 3) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis for proteins relating to ICC, enteric nerves, and MYH11 cells in antrums from Lepob and wild-type animals. A: Representative Western blots comparing the expression of various proteins associated with ICC (KIT; DLG4), enteric nerves (NOS1; UCHL1, SNAP25, and syntaxin), and MYH11 in wild-type and Lepob mice, respectively. Each band is demarcated by a boundary box to illustrate that they were from different gels or different parts of the same gel. Bands are the most representative from the gastric antrums of three different animals. GAPDH was used as a control housekeeping protein to which the other proteins were compared. Three separate GAPDH blots, one from each animal, are shown. B: Western blot analysis bands from wild-type and Lepob antrums were quantified by densitometry and expressed relative to GAPDH. The summary graph demonstrates that the major proteins associated with ICC, enteric neurons, and smooth muscle were unchanged in the antrums of Lepob compared with wild-type animals (unpaired Student t test). M, marker.

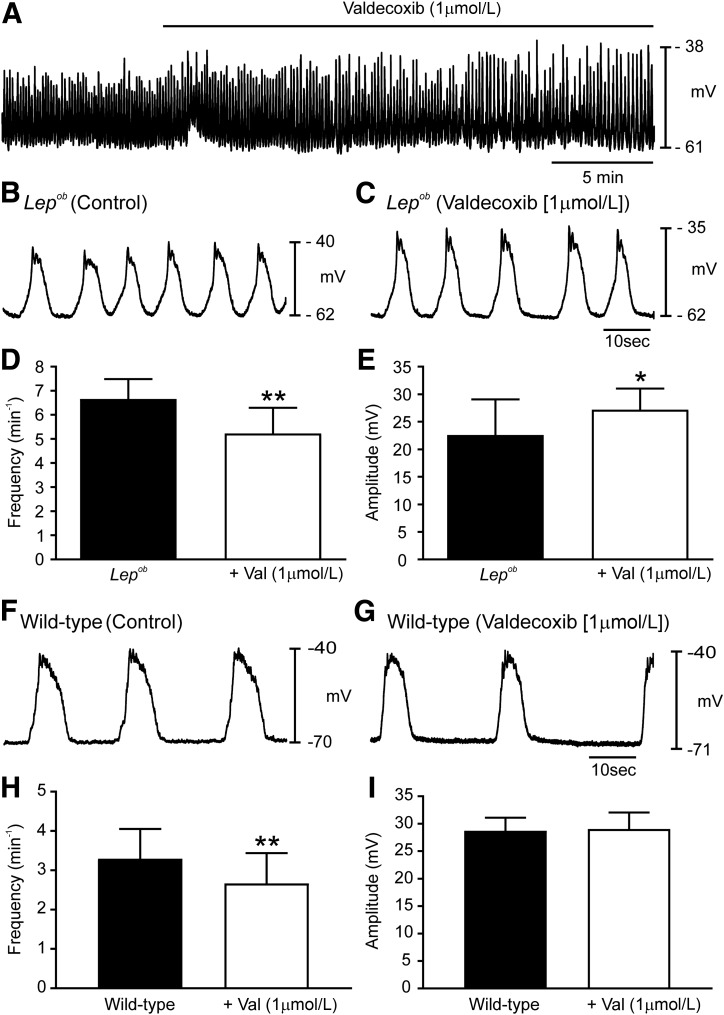

Effects of the PTGS2 Inhibitor Valdecoxib on Electrical and Mechanical Activities of Lepob Gastric Antrums

Slow waves from Lepob antrums are similar in waveform to wild-type slow waves after PGE2 application (23,24). Thus, we recorded slow waves from Lepob antrums before and in the presence of the PTGS2 inhibitor valdecoxib (Fig. 5A–C). Under control conditions, Lepob antrums exhibited slow waves with a frequency of 6.7 ± 0.8 min−1 and an amplitude of 23 ± 7.0 mV (Fig. 5B, D, and E) (n = 6). (Note: recordings were made from region 5.) Valdecoxib (1 µmol/L) reduced slow wave frequency to 5.2 ± 1.1 min−1 (Fig. 5C and D) (P = 0.0059), and slow wave amplitude increased to 27 ± 4.0 mV (Fig. 5C and E) (P = 0.0161). Half-maximal duration of slow waves, ISWP, and RMP were not significantly affected by valdecoxib. Like slow waves, the amplitudes of phasic contractions increased, and contraction frequency decreased after valdecoxib application. Contractile force generated by Lepob antrums averaged 1.04 ± 0.51 mN and occurred at 3.8 ± 1.5 min−1 (Supplementary Fig. 5A–D). In valdecoxib (1 µmol/L), contractile force increased to 2.15 ± 1.25 mN (Supplementary Fig. 5B and D) (P < 0.001; n = 4) and frequency decreased to 2.5 ± 0.8 min−1 (Supplementary Fig. 5B and C) (P = 0.001; n = 5).

Figure 5.

PTGS2 inhibition normalizes disrupted antral pacemaker activity in Lepob antrums. A: Continuous intracellular microelectrode recording from a Lepob antrum under control conditions (no drugs) and after the addition of the PTGS2 inhibitor valdecoxib (1 μmol/L). Slow waves increased in amplitude and decreased in frequency. Intracellular recordings at a faster sweep speed before (B) and in the presence of valdecoxib (C). Traces show the changes in slow wave parameters. Summary of slow wave changes in slow wave frequency (D) and slow wave amplitude (E). Typical recordings of wild-type antrum under control conditions (F) and after the addition of valdecoxib (G). H and I: Summary of the effects of valdecoxib (Val) on slow wave frequency amplitude. Valdecoxib decreased frequency but had no effect on amplitude (paired Student t test). *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01.

Valdecoxib also affected wild-type muscles. Slow waves were reduced in frequency from 3.3 ± 0.8 min−1 to 2.7 ± 0.8 min−1 (Fig. 5F–H) (P = 0.003; n = 6). The ISWP increased from 11.9 ± 5.5 s to 18.5 ± 7.4 s (P = 0.016; n = 6). However, no differences were detected in amplitude (Fig. 5F, G, and I), half-maximal duration or RMP. Valdecoxib (1 µmol/L) also influenced contractile activity in wild-type animals, reducing the frequency from 3.2 ± 0.5 min−1 to 2.7 ± 0.4 min−1 (Supplementary Fig. 5E–G) (P = 0.001; n = 7). A small increase in contractile amplitude in Lepob antrums did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Fig. 5E, F, and H) (n = 6).

Video imaging revealed that PTGS2 inhibition also affected motility in Lepob antrums. The spatiotemporal map in Supplementary Fig. 5I shows that Lepob antrums exhibit frequent, weak contractions. After application of valdecoxib (1 µmol/L; 20 min), contractions became more robust and occurred at a frequency of 2.8 min−1 (Supplementary Fig. 5J).

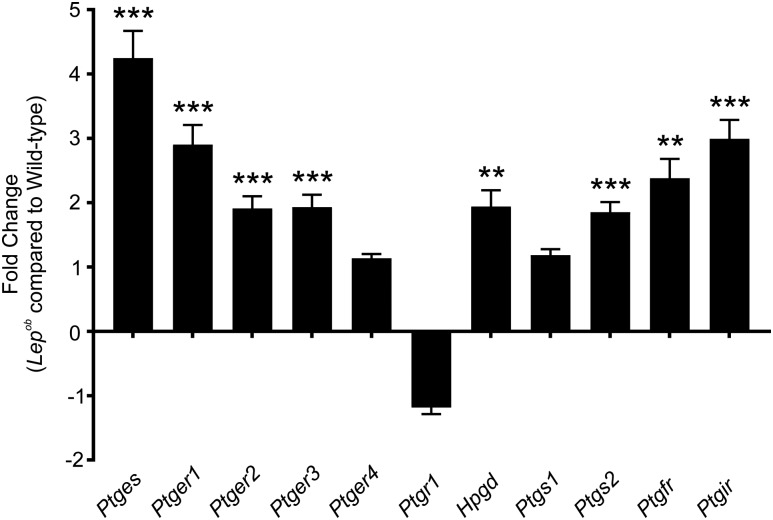

Changes in mRNA Expression of Key Genes Associated With Prostaglandin Signaling in Gastric Antrums from Lepob Mice

Chronic, subclinical inflammation is associated with type 2 diabetes, and chronic inflammation has been shown to underlie the development of insulin resistance in animal models of type 2 diabetes (29). As inflammation causes PTGS2 upregulation (30), qPCR was performed to determine whether PTGS2 and other enzymes involved in prostaglandin synthesis, its breakdown, and receptors involved in mediating its biological response were changed in Lepob antrums. Ptgs2 was significantly upregulated in Lepob antrums (Fig. 6) (n = 4; P = 0.0003). Likewise, expression of the terminal enzyme for PGE2 synthesis, Ptges, was also significantly increased (Fig. 6) (n = 4; P = 0.0004). Expression of PGE2 receptor subtypes EP1, EP2, and EP3 (Ptger1, Ptger2, and Ptger3) was also increased in Lepob antrums (Fig. 6) (n = 4; P = 0.0007, 0.0005, and 0.0007, respectively), whereas expression of Ptger4 (PGE2 receptor subtype EP4) was not altered. We also assessed the mRNA expression of Ptgfr and Ptgir, receptors for PGF2α and PGI2, and both were significantly increased in Lepob antrums (Fig. 6) (n = 4; P = 0.0019 and 0.0002, respectively). Finally, Hpgd (15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase), an enzyme involved in the breakdown of prostaglandins, was increased in diabetic antrums (Fig. 6) (n = 4; P = 0.0018). Other enzymes involved in production and breakdown of prostaglandins, Ptgs1 (prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1) and Ptgr1 (prostaglandin reductase 1), respectively, were not changed in Lepob antrums. Because valdecoxib, a specific PTGS2 inhibitor, had significant effects on antral electrical and contractile behavior of Lepob antrums (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 5), upregulation of gene transcripts likely plays a significant role in the changes in gastric motor activity in these diabetic animals.

Figure 6.

qPCR comparing the expression of several key genes involved in prostaglandin synthesis and signaling in antrums from wild-type and Lepob mice. Bar graph depicts the fold change in prostaglandin-related gene transcripts. Several gene products were shown to be significantly upregulated in Lepob antrums compared with wild-type controls: terminal Ptges, Ptger1, Ptger2, Ptger3, Ptgs2, PGF receptor (Ptgfr), Ptgir, and Hpgd. Ptger4, Ptgr1, and Ptgs1 did not differ significantly in gene transcript expression between Lepob antrums and wild-type controls (unpaired Student t test). **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Discussion

Patients with diabetes often suffer significant GI symptoms, including gastroparesis, which can significantly impair their quality of life (31). Previous studies suggested that an enteric neuropathy is the underlying cause of gastroparesis. A decrease in NOS1-containing inhibitory neurons, and changes in cholinergic excitatory neurons, have been reported in the GI tracts of diabetic animal models (2,32). Reduced numbers of ICC have also been observed in diabetic GI muscles (5,6,33). More recently, increased numbers of ICC have been reported in Leprdb mice with rapid gastric emptying (17). Thus, reports on the underlying changes in enteric nerves and ICC vary considerably. Despite the number of studies that have reported changes in neuronal or ICC populations, little information has been garnered on functional changes that underlie gastroparesis associated with type 2 diabetes.

In this study, we used Lepob mice, a type 2 diabetic animal model, to examine functional changes that occur in gastric electrical and mechanical activities. Electrical slow waves were increased in frequency and reduced in amplitude and associated contractions were more frequent and weaker in diabetic antrums compared with wild-type animals. Furthermore, electrical recordings made from nine defined antral recording sites revealed that slow waves were significantly reduced and, in some animals, could not be resolved at several sites in Lepob antral muscles. These data would suggest that slow wave generation in some sites becomes ineffective and propagation of slow waves, necessary for coordinated gastric peristalsis and efficient chemomechanical breakdown of gastric contents, does not occur normally. Such loss of function could lead to delayed gastric emptying. This information was only detected following systematic electrical recordings from an array of multiple sites and would be undetected if single-recording sites or larger tissue preparations were used (i.e., isometric force measurements).

We found no evidence that the densities of NOS1+ neurons and ICC were altered in Lepob mice. Recently, it has been reported that gene transcripts for NOS1 and VAChT, biomarkers for inhibitory and excitatory neurons, were slightly increased in gastric tissues from patients with idiopathic gastroparesis without diabetes (34). This study also revealed no significant changes in gene transcripts specific for ICC (e.g., Kit and Ano1) in these patients, although decreased Pdgfra, a marker for PDGFRα+ cells, was observed. In Lepob mice, the density of PDGFRα+ cells, another specialized interstitial cell in GI muscles (35), appeared normal, as previously reported for gastric muscles of human patients with diabetes (36). Thus, considerable discrepancy exists in reports describing changes in enteric nerve and interstitial cell populations depending on the animal model or type of diabetes studied.

Rather than gross morphological or structural changes in neurons or interstitial cells, changes in slow wave activity in Lepob mice appear to be due to abnormal prostaglandin production and responses. The conclusion that prostaglandins are involved stems from the observation that PTGS2 inhibition by valdecoxib resulted in slow wave frequency and amplitude returning toward normal values and contractile activity becoming more robust, similar to wild-type controls. Valdecoxib, at the concentration used in the current study, is reported to be a potent and selective inhibitor of PTGS2 versus PTGS1 in vitro and in vivo (37). Thus, the normalization of slow wave activity in Lepob mice is likely be due to inhibition of PTGS2 rather than PTGS1. Application of PGE2 to wild-type antrums results in increased slow wave frequency and reduction in amplitude (23,24), mimicking Lepob antrum activity. The positive chronotropic effects of prostaglandins may occur via PTGER3, as specific agonists of this receptor increased pacemaker activity in isolated ICC and tissues (25). Stretch-dependent experiments on the gastric antrum revealed that length ramps produced membrane depolarization and chronotropic effects on pacemaker activity (38). These stretch-dependent responses were inhibited by indomethacin and absent in PTGS2-deficient mice. Stretch-dependent responses on W/Wv mice that lack gastric ICC-IM were absent. These data suggested that antral ICC-IM are mechanosensitive, and chronotropic responses to length ramps were mediated via prostaglandin production by these cells (38).

Diabetes is associated with chronic, subclinical inflammation and considered an inflammatory disease (29). Macrophage-derived inflammation in adipose tissue can trigger insulin resistance (39). Changes in macrophage populations are reported to occur in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. In the stomachs of these patients, there was loss of CD206+ anti-inflammatory macrophages and associated loss of ICC, suggesting that CD206+ macrophages are cryoprotective (40,41). However, we did not observe a loss of antral ICC in the current study and cannot say whether an inflammatory response exists in Lepob antrums. To explain the changes in gastric motor activity of Lepob stomachs, we examined the expression of genes involved in the synthesis and breakdown PGE2, and its receptors, as these components of the prostaglandin pathway affect gastric motor activity (20,23,24). We found that Ptgs2 gene transcripts were upregulated in Lepob antrums. Furthermore, Ptges, which encodes microsomal PGE2 synthase, is also highly augmented in Lepob antrums, providing an additional mechanism that could contribute to the apparent increase in PGE2 activity. PTGES is a terminal PGE synthase that converts PGH2 to PGE2 (Fig. 7). Unlike other PGE synthases (PTGES2 and PTGES3), which are constitutively expressed, PTGES is induced by proinflammatory stimuli and has been observed to be upregulated in various inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (42). In addition to PGE2 synthesis enzymes, we found that gene transcripts for multiple PGE2 receptors (Ptger1, Ptger2, and Ptger3) were also increased in diabetic antrums. This indicates that, along with increased PGE2 production, the tissue also has a greater capacity to respond to PGE2. Notably, Ptger3, encoding PTGER3, is one of the upregulated gene transcripts, and, as previously mentioned, it has been implicated as the receptor involved in the gastric motor effects of PGE2 (24,25). Additionally, Ptgfr and Ptgir, which encode the receptors for PGF2α and PGI2, respectively, were increased. Both PGF2α and PGI2 are known to affect gastric motor activity, but PGF2α does not affect gastric rhythmicity (43), and PGI2 had a much weaker effect on motility than PGE2 (44).

In this study, we did not observe changes in NOS1+ enteric neurons or ICC, contrasting with some previously published findings (2,6,45). An explanation for this disparity is the different approaches used to identify and quantify particular GI cell types. In previous studies, cross-section preparations of muscle tissues have simply been used to quantify cells of interest. This technique has received criticism and is currently generally not a well-accepted approach to determine changes in GI muscles (46). Our immunohistochemical analysis was performed using confocal microscopy on six randomly selected areas of whole mounts imaging the entire muscle thickness. Thus, the approach taken in this study should accurately reflect the genuine situation of cellular networks of Lepob antrums. Another possible reason is that we used an animal model of type 2 diabetes, whereas the majority of previously studies have investigated type 1 or streptozotocin-induced diabetes.

Although we have observed profound changes in the prostaglandin pathway in Lepob antrums, we also found that PTGS2 inhibition affected slow wave activity in wild-type mice. It has previously been shown that PTGS2 is constitutively expressed in antral tissues of wild-type mice (20). Because PTGS2 inhibition altered pacemaker activity and contractile responses in Lepob and wild-type antrums, this suggests ongoing PGE2 production in wild-type tissues, although production is upregulated in Lepob antrums.

In conclusion, pacemaker activity in the gastric antrum is disrupted in a type 2 diabetic mouse model. Slow waves were increased in frequency and reduced in amplitude, resulting in phasic contractions that were augmented in frequency and greatly reduced in amplitude. These changes may be involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic gastroparesis. The disruption in pacemaker activity is likely the result of increased prostaglandin synthesis enzymes and receptors for PGE2. These findings raise the exciting possibility of a novel treatment for diabetic gastroparesis by inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Nancy Horowitz (Department of Physiology and Cell Biology, University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine, Reno, NV) for maintaining and helping with the breeding of animals.

Funding. This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant DK-57236 and Diabetic Complications Consortium (DiaComp) Pilot Funding to S.M.W. and by P01-DK-41315 to K.M.S. and S.M.W. Confocal imaging was supported by an equipment grant from the National Center for Research Resources for the Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope (1-S10-RR16871).

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. P.J.B., S.J.H., M.C.S., L.E.P., and Y.B. performed experiments. P.J.B. analyzed data and wrote and critically reviewed the manuscript. K.M.S. wrote and critically reviewed the manuscript. S.M.W. designed experiments and wrote and critically reviewed the manuscript. S.M.W. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db18-1064/-/DC1

References

- 1.Ebert EC. Gastrointestinal complications of diabetes mellitus. Dis Mon 2005;51:620–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wrzos HF, Cruz A, Polavarapu R, Shearer D, Ouyang A. Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) expression in the myenteric plexus of streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:2106–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stenkamp-Strahm CM, Kappmeyer AJ, Schmalz JT, Gericke M, Balemba O. High-fat diet ingestion correlates with neuropathy in the duodenum myenteric plexus of obese mice with symptoms of type 2 diabetes. Cell Tissue Res 2013;354:381–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballmann M, Conlon JM. Changes in the somatostatin, substance P and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide content of the gastrointestinal tract following streptozotocin-induced diabetes in the rat. Diabetologia 1985;28:355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ordög T, Takayama I, Cheung WK, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Remodeling of networks of interstitial cells of Cajal in a murine model of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes 2000;49:1731–1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang XY, Huizinga JD, Diamond J, Liu LW. Loss of intramuscular and submuscular interstitial cells of Cajal and associated enteric nerves is related to decreased gastric emptying in streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2009;21:1095–e92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forster J, Damjanov I, Lin Z, Sarosiek I, Wetzel P, McCallum RW. Absence of the interstitial cells of Cajal in patients with gastroparesis and correlation with clinical findings. J Gastrointest Surg 2005;9:102–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faussone-Pellegrini MS, Grover M, Pasricha PJ, et al.; NIDDK Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GpCRC) . Ultrastructural differences between diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. J Cell Mol Med 2012;16:1573–1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward SM, Burns AJ, Torihashi S, Sanders KM. Mutation of the proto-oncogene c-kit blocks development of interstitial cells and electrical rhythmicity in murine intestine. J Physiol 1994;480:91–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Klüppel M, Malysz J, Mikkelsen HB, Bernstein A. W/kit gene required for interstitial cells of Cajal and for intestinal pacemaker activity. Nature 1995;373:347–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaylor LA, Hwang SJ, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Convergence of inhibitory neural inputs regulate motor activity in the murine and monkey stomach. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2016;311:G838–G851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns AJ, Lomax AE, Torihashi S, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate inhibitory neurotransmission in the stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:12008–12013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung TS, Hwang SJ, Koh SD, et al. . The cells and conductance mediating cholinergic neurotransmission in the murine proximal stomach. J Physiol 2018;596:1549–1574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi KM, Gibbons SJ, Nguyen T V, Stoltz GJ, Lurken MS, Ordog T, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 protects interstitial cells of Cajal from oxidative stress and reverses diabetic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:2055–2064, 2064.e1–e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Yamamoto T, Watabe K, Nakahara M, et al. . Disturbed gastrointestinal motility and decreased interstitial cells of Cajal in diabetic db/db mice. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:660–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bharucha AE, Camilleri M, Forstrom LA, Zinsmeister AR. Relationship between clinical features and gastric emptying disturbances in diabetes mellitus. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009;70:415–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi Y, Toyomasu Y, Saravanaperumal SA, et al. . Hyperglycemia increases interstitial cells of Cajal via MAPK1 and MAPK3 signaling to ETV1 and KIT, leading to rapid gastric emptying. Gastroenterology 2017;153:521–535.e20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders KM, Northrup TE. Prostaglandin synthesis by microsomes of circular and longitudinal gastrointestinal muscles. Am J Physiol 1983;244:G442–G448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rådmark O, Samuelsson B. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 and 5-lipoxygenase: potential drug targets in cancer. J Intern Med 2010;268:5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porcher C, Horowitz B, Bayguinov O, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Constitutive expression and function of cyclooxygenase-2 in murine gastric muscles. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1442–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porcher C, Horowitz B, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Constitutive and functional expression of cyclooxygenase 2 in the murine proximal colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2004;16:785–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samuelsson B. Role of basic science in the development of new medicines: examples from the eicosanoid field. J Biol Chem 2012;287:10070–10080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanders KM. Role of prostaglandins in regulating gastric motility. Am J Physiol 1984;247:G117–G126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forrest AS, Hennig GW, Jokela-Willis S, Park CD, Sanders KM. Prostaglandin regulation of gastric slow waves and peristalsis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2009;296:G1180–G1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim TW, Beckett EA, Hanna R, et al. . Regulation of pacemaker frequency in the murine gastric antrum. J Physiol 2002;538:145–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang SJ, Blair PJ, Britton FC, et al. . Expression of anoctamin 1/TMEM16A by interstitial cells of Cajal is fundamental for slow wave activity in gastrointestinal muscles. J Physiol 2009;587:4887–4904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCann CJ, Hwang S-J, Hennig GW, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Bone marrow derived kit-positive cells colonize the gut but fail to restore pacemaker function in intestines lacking interstitial cells of Cajal. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;20:326–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Worth AA, Forrest AS, Peri LE, Ward SM, Hennig GW, Sanders KM. Regulation of gastric electrical and mechanical activity by cholinesterases in mice. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;21:200–216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest 2005;115:1111–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clària J. Cyclooxygenase-2 biology. Curr Pharm Des 2003;9:2177–2190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talley NJ, Young L, Bytzer P, et al. . Impact of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes mellitus on health-related quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:71–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LePard KJ. Choline acetyltransferase and inducible nitric oxide synthase are increased in myenteric plexus of diabetic guinea pig. Auton Neurosci 2005;118:12–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grover M, Farrugia G, Lurken MS, et al.; NIDDK Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium . Cellular changes in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1575–85.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herring BP, Hoggatt AM, Gupta A, et al. . Idiopathic gastroparesis is associated with specific transcriptional changes in the gastric muscularis externa. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;30:e13230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurahashi M, Zheng H, Dwyer L, Ward SM, Koh SD, Sanders KM. A functional role for the ‘fibroblast-like cells’ in gastrointestinal smooth muscles. J Physiol 2011;589:697–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grover M, Bernard CE, Pasricha PJ, et al. . Platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα)-expressing “fibroblast-like cells” in diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis of humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:844–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gierse JK, Zhang Y, Hood WF, et al. . Valdecoxib: assessment of cyclooxygenase-2 potency and selectivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005;312:1206–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Won KJ, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate mechanosensitive responses in the stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:14913–14918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, et al. . Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2003;112:1821–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernard CE, Gibbons SJ, Mann IS, et al.; NIDDK Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GpCRC) . Association of low numbers of CD206-positive cells with loss of ICC in the gastric body of patients with diabetic gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:1275–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grover M, Bernard CE, Pasricha PJ, et al.; NIDDK Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GpCRC) . Diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis is associated with loss of CD206-positive macrophages in the gastric antrum. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;29:e13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subbaramaiah K, Yoshimatsu K, Scherl E, et al. . Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 is overexpressed in inflammatory bowel disease. Evidence for involvement of the transcription factor Egr-1. J Biol Chem 2004;279:12647–12658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norstein J, Ertresvaag K, Gerner T, Haffner JF. Motor responses to prostaglandin F2 alpha in isolated guinea pig fundus and antrum. Scand J Gastroenterol 1983;18:151–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nitta H, Ishizawa M. Endogenous prostaglandins and spontaneous contractions in the circular muscle of the guinea-pig stomach. Jpn J Physiol 1980;30:815–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spångéus A, Suhr O, El-Salhy M. Diabetic state affects the innervation of gut in an animal model of human type 1 diabetes. Histol Histopathol 2000;15:739–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knowles CH, De Giorgio R, Kapur RP, et al. . Gastrointestinal neuromuscular pathology: guidelines for histological techniques and reporting on behalf of the Gastro 2009 International Working Group. Acta Neuropathol 2009;118:271–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.