Abstract

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction is a common complication following cardiac surgery. The incidence of cognitive dysfunction is more pronounced in patients receiving a cardiac operation than in those undergoing a non-cardiac operation. Clinical observations demonstrated that pulsatile flow was superior to nonpulsatile flow, and membrane oxygenator was superior to bubble oxygenator in terms of postoperative cognitive status. Nevertheless, cognitive assessments in patients receiving an on-pump and off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery have yielded inconsistent results. The exact mechanisms of postoperative cognitive dysfunction following coronary artery bypass grafting remain uncertain. The dual effects, neuroprotective and neurotoxic, of anesthetics should be thoroughly investigated. The diagnosis should be based on a comprehensive cognitive evaluation with neuropsychiatric tests, cerebral biomarker inspections, and electroencephalographic examination. The management strategies for cognitive dysfunction can be preventive or therapeutic. The preventive strategies of modifying surgical facilities and techniques can be effective for preventing the development of postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Investigational therapies may offer novel strategies of treatments. Anesthetic preconditioning might be helpful for the improvement of this dysfunction.

Keywords: Cognitive Dysfunction; Coronary Artery Bypass; Coronary Artery Bypass, Off-Pump; Postoperative Complications

| Abbreviations, acronyms & symbols | |

|---|---|

| βAP | = β-amyloid peptide |

| CABG | = Coronary artery bypass grafting |

| CAM | = Confusion Assessment Method |

| CFQ | = Cognitive Failures Questionnaire |

| CPB | = Cardiopulmonary bypass |

| isoP | = iso-prostane |

| MoCA | = Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| MMSE | = Mental Status Examination |

| NfH | = Neuro-filament heavy chain |

| NSE | = Neuron-specific enolase |

| POCD | = Postoperative cognitive dysfunction |

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), characterized by impairment of attention, concentration, and memory with possible long-term implications, is a frequent neurological sequela following cardiac surgery. According to duration, POCD can be classified into two types: short-term and long-term. The former is usually a transitory cognitive decline lasting up to 6 weeks after a cardiac operation with an incidence of 20-50%, whereas the latter can be a subtle deterioration of cognitive function occurring six months after an operation with an incidence of 10-30%[1]. However, POCD might occur several years after an operation. The incidence of POCD depends on the types of operation, and it is more pronounced in patients receiving a cardiac operation than in those undergoing a non-cardiac operation[2]. A retrospective study demonstrated that coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is the most common cause of POCD after a cardiac operation with an incidence of 37.6% in 7 days and 20.8% in the 3rd month of the postoperative period[3].

POCD should be distinguished with relevant concepts, such as postoperative delirium and vascular dementia. Postoperative delirium is an acute mental syndrome characterized by a transient fluctuating disturbance of consciousness, attention, cognition, and perception as a common complication of surgery, occurring in 36.86% of the surgical patients[4]. The significant risk factors responsible for postoperative delirium were peripheral arterial disease, preexisting cerebrovascular disorders, and a reduced preoperative Hasegawa-dementia score[5]. POCD is a subtler deficit affecting patients' cognition, including verbal, visual, language, visuospatial, attention, and concentration aspects[4]. A more delayed development of POCD may indicate a poorer prognosis. Associated POCD and delirium was noted in 77% of aortic surgical patients at discharge, which suggests that both conditions could share a common mechanism[4]. Vascular dementia, as a result of any vasculopathies, is the most common type of dementia in elderly patients, who often have significant impairment of social or occupational functions, usually accompanied by focal motor and sensory abnormalities[6].

Cognitive assessments between conventional CABG with the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) (on-pump) and CABG without CPB (off-pump) yielded inconsistent results. The exact mechanisms of development of POCD following CABG and cognitive impact of anesthetics remain uncertain. The diagnosis and treatment of POCD are still challenging. This article aims to present an overview of POCD following CABG.

Predictive Risk Factors

Predictive risk factors of POCD may include old age, preexisting cerebral, cardiac, and vascular diseases, alcohol abuse, low educational level, and intra- and postoperative complications[7]. A univariant analysis revealed that older age, female gender, higher bleeding episodes, and increased postoperative creatinine levels were more significantly associated with POCD[8]. Laalou et al.[9] described that POCD was age- and observational time-related, with an incidence of 23-29% in patients aged 60-69 and >70 years in one week, and 14% in those aged >70 years in the 3rd month of the postoperative period. Cerebral hypoperfusion is an important risk factor contributing to postoperative brain damage, especially in atherosclerotic patients due to hypoperfusion-induced impaired clearance of microemboli and worsened ischemic damage[10]. POCD can result from systemic or cerebral inflammation due to neuronal injuries[11]. Surgical operation might trigger brain mast cell degranulation, microglia activation, and release of inflammatory cytokines, thus, leading to neuronal damages, and activated brain mast cells might induce neuronal apoptosis[12]. The association between increased levels of plasma inflammatory mediators (interleukin-1, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and C-reactive protein) and cognitive dysfunction has been found in postoperative patients and could eventually predict future cognitive decline[13]. Autonomic nervous suppression in relation to neuroendocrine response as well as cytokine production to surgery and anesthesia might play an important role in the development of POCD[9]. Other conditions like increased plasma cortisol levels via stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis[9] and preexisting cerebrovascular disease[14] could be specific risk factors of POCD.

Diagnosis

Neuropsychiatric Tests

POCD is verified by employing batteries of psychometric tests performed pre- and postoperatively to assess cognitive performance. Currently, there is no gold standard, but some tests (Rey auditory verbal learning test, Trail-making A, Trail-making B, and Grooved pegboard) were recommended as core tests as proposed by Murkin et al.[15] in 1995. Typically, a battery of tests is composed of a comprehensive assessment of the cognitive status, including memory, attention, language, executive function, and motor speed[14]. The Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE), a commonly used screening test for dementia with remarkable validity and reliability[16], is sometimes used to quantify POCD[17], and an MMSE value below 25 is regarded as POCD[18]. However, comparing cognitive function before operation and adjustment of age or education level is important before determining the POCD. In addition, the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) were used pre- and postoperatively to evaluate the cognitive status[18]. The neuropsychiatric tests that are used in clinical practice are shown in Table 1[8,15,16,18-21]. Habib et al.[8] noted that the McNair scale was more evident than MMSE. Proust-Lima et al.[21] found that MMSE and Benton Visual Retention Test showed a superior sensitivity over Isaacs Set Test and Digit Symbol Substitution Test.

Table 1.

Neuropsychiatric tests for cognitive assessment in clinical practice.

| Year | Author | Neuropsychiatric tests |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Murkin et al.[15] | Core tests (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, Trail Making A, Trail Making B, and Grooved Pegboard) |

| 2002 | Stroobant et al.[19] | Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) (verbal memory), Trail Making Test (TMT Part B) (speed for visual search, attention and mental flexibility), Grooved Pegboard Test (GPT) (finger and hand dexterity), Block Taps Test (TAPS) (non-verbal immediate memory and attention), Line Bisection Test (LBT) (unilateral visual inattention), Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) (word fluency), and Judgement of Line Orientation (JLO) (ability for angular relationships between line segments) |

| 2010 | Benabarre et al.[20] | Positive and Negative Symptom Scale, Global Assessment Functioning, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), Stroop Test, Trail Making Test (TMT), California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS), and Phonetic Verbal Fluency/Controlled Oral Word Association Tests |

| 2007 | Proust-Lima et al.[21] | Benton Visual Retention Test |

| 2012 | Jildenstål et al.[18] | Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) and Cognitive Failures Questionnaire (CFQ) |

| 2014 | Habib et al.[8] | McNair Scale |

| 2015 | Saraçlı et al.[16] | Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) |

Cerebral Biomarker Inspections

Biomarkers in relation to POCD have been described as β-amyloid peptide (βAP), tau, phospho-tau, apoE, interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, cortisol, S100β, and neuron-specific enolase (NSE). Increased serum tau level was seen in patients with cognitive decline after CPB, and increased cerebrospinal fluid βAP and tau levels were similar to those having Alzheimer's disease. Serum interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and NSE are important indicators of POCD following CABG[22]. NSE, S100, and S100β are more sensitive for detecting cerebral structural and functional damages in patients undergoing various cardiac operations, and all peaked at the end of CPB[23]. Alternative potential indicators for POCD include neuro-filament heavy chain (NfH), iso-prostane (isoP), and reduced cerebral perfusion/hypoxia[22].

Electroencephalography

Increased lower frequencies, reduced complex activities, and incoherent cortical regions/fast rhythms shown on the electroencephalogram may indicate POCD[22].

Literature Review

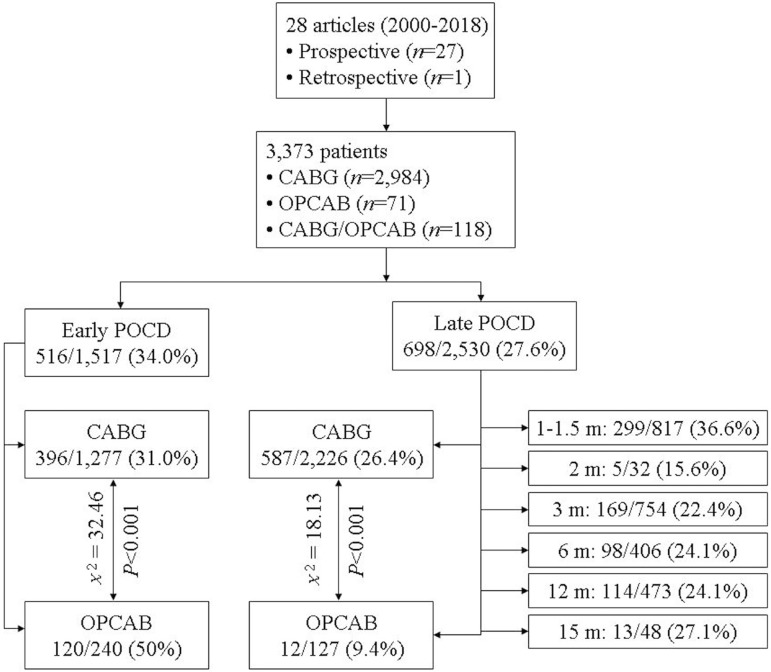

Pertinent literature was retrieved for articles published between 2000-2018. The search terms included "coronary artery bypass grafting", "on-pump", "off-pump", "cognitive decline", "postoperative cognitive dysfunction", "diagnosis", and "treatment". A total of 28 prospective or retrospective research articles were obtained which involved 3.373 patients[24-51]. The early and late rates of POCD were 34% and 27.6%, respectively. The statistical analysis made by Fisher's exact test for comparisons of frequencies showed that the early POCD rate was lower, but the late POCD rate was higher in CABG in comparison to OPCAB patients (Figure 1). The disparities in the early and late POCD incidences compared to the results reported in the literature were probably due to the differences in literature selection. Additionally, the literature review outstood some attenuators and intensifiers of POCD following CABG procedures (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

The outcomes of the review with a depiction of early and late postoperative cognitive dysfunctions following coronary artery bypass grafting.

*Comparisons of frequencies were made by Fisher's exact test.

CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting; m=months; OPCAB=off-pump coronary artery bypass; POCD=postoperative cognitive dysfunction

Table 2.

Literature review of representative publications on postoperative cognitive dysfunction following coronary artery bypass grafting.

| Author, year | Type of study | Patient number (CABG/OPCAB) | Intervention (parameter) | POCD, n (%) | Recommendation | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attenuator | Intensifier | ||||||

| Kumpaitiene et al.[24], 2018 | Prospective observational study | 59/0 | Erythromycin (rSO2, NSE and GFAP) | 22 (37) on POD10 | No significant changes in blood GFAP level occurred in any patients; decreased rSO2 and increased NSE level did not correlate with rate of POCD | Erythromycin | |

| Thomaidou et al.[25], 2017 | Prospective randomized pilot study | 40/0 | Erythromycin (25 mg/kg) vs. control (Serum IL-1, IL-6 and tau) | 19 (47.4) vs. 16 (76.2) just after hospital discharge, and 6 (31.6) vs. 38 (95.2) in 3 months | Erythromycin | ||

| Kok et al.[26], 2017 | Randomized clinical trial | 57 (CABG or OPCAB) | (Serum brain fatty acid-binding protein) | 15 (26) in 3 months, and 13 (27) in 15 months | Classical neuronal injury-related biomarkers had no prognostic value for POCD | ||

| Silva et al.[27], 2016 | Prospective observational study | 88/0 | (Serum S100β and NSE) | 23 (26.1) at 21 days, and 20 (22.7) in 6 months | Serum S100B was more accurate than NSE in the detection of POCD | ||

| ÖztÜrk et al.[28], 2016 | Prospective, randomized, double-blind study | 40/0 | Pulsatile vs. nonpulsatile flow (Serum 100β and NSE) | 3 (15) vs. 3 (15) on POD3 | No difference between types of pump flow for POCD | ||

| Oldham et al.[29], 2015 | Prospective observational cohort study | 102/0 | 14 (14) on POD2 through discharge | Cognitive and functional impairment independently predicted postoperative delirium and delirium severity | Preoperative cognitive and functional impairment | ||

| Hassani et al.[30], 2015 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 61/0 | Valerian capsule (containing 530 mg of valerian root extract/capsule) (1,060 mg/day) vs. placebo capsule each 12 h for 8 weeks | Valerian prophylaxis: reduced odds of POCD in comparison to placebo on POD10 and in 2 months | Valerian capsule | ||

| Dong et al.[31], 2014 | Prospective cohort study | 108/0 | (Plasma copeptin) | 35 (32.4) on POD7 | Postoperative plasma copeptin level may be a useful predictor of POCD | ||

| Trubnikova et al.[32], 2014 | Case-control study | 101/0 | MCI vs. non-MCI | 36 (72) vs. 40 (79) at early stage (P=0.5), and 36 (72) vs. 35 (70) in 1 year (P=0.8) | MCI was not a leading cause of early or long-term POCD | ||

| Kok et al.[33], 2014 | Randomized pilot study | 29/30 | CABG vs. OPCAB (Cerebral oximetry variable) | 11 (39) vs. 4 (14) at early stage (P=0.50), and 4 (14) vs. 0 (0) at 3 months (P=0.03) | There was no association between intraoperative cerebral oximetry variables and POCD at any stage | OPCAB | CABG |

| Szwed et al.[34], 2014 | Prospective observational single-surgeon trial | 0/74 | "No-touch" OPCAB vs. "traditional" OPCAB | 10 (28.6) vs. 20 (51.3) on POD7 (discharge) | "No touch" OPCAB | ||

| Fontes et al.[35], 2014 | Retrospective study | 118/0 (CABG or CABG + valve surgery with CPB) | Arterial hyperoxia during CPB | 53 (45) at 6 weeks | Arterial hyperoxia during CPB was not associated with neurocognitive decline after 6 weeks | ||

| Sirvinskas et al.[36], 2014 | Prospective study | 50/0 | Head-cooling vs. no head-cooling | 9 (36) vs. 16 (64) on POD10 (P=0.048) | Head-cooling technique during the aortic cross-clamp | ||

| Joung et al.[37], 2013 | Randomized pilot study | 0/70 | rIPC vs. control | 10 (28.6) vs. 11 (31.4) on POD7 (P=0.794) | rIPC did not reduce the incidence of POCD | ||

| Mu et al.[38], 2013 | Prospective cohort study | 166/0 | (Serum cortisol) | 66 (39.8) on POD7 | High serum cortisol level on POD1 | ||

| Kadoi et al.[39], 2011 | Prospective study | 124/0 | Normal vs. medium vs. impaired cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity | 20 (30) vs. 10 (25) vs. 11 (57) on POD7, and 16 (24) vs. 9 (23) vs. 5 (26) at 6 months | Impaired cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity | ||

| de Tournay-Jettéet al.[40], 2011 | Prospective study | 61 (CABG or OPCAB) | (rSO2) | 46 (80.7) on POD4-7, and 23 (38.3) in 1 month | Intraoperative rSO2 desaturation | ||

| Slater et al.[41], 2009 | Prospective controlled study | 240/0 | (rSO2 saturation) | 70 (29) in 3 months | Patients with rSO2 desaturation score >3,000%-second had a significantly higher risk of POCD | rSO2 desaturation score >3,000%-second | |

| Haljan et al.[42], 2009 | Prospective study | 32/0 | Erythropoietin vs. placebo | 2 (8.3) vs. 3 (38) in 2 months (P=0.085) | Erythropoietin | ||

| Silbert et al.[43], 2008 | Prospective study | 282/0 | (Apolipoprotein genotype) | 33 (12) in 3 months, and 31 (11) in 12 months | There was no relationship between presence of the apolipoprotein epsilon4 allele or any of the six genotypes and POCD | ||

| Jensen et al.[44], 2008 | Prospective randomized study | 47/43 | CABG vs. OPCAB | 4 (9) vs. 8 (19) in 12 months (P=0.18) | No significant differences in the incidence of POCD between CABG and OPCAB group | ||

| Hogue et al.[45], 2008 | Prospective study | 113/0 (CABG/CABG+ valve operation) | (Apolipoprotein epsilon4 genotype) | 28 (25) in 4-6 weeks | Mild atherosclerosis of the ascending aorta, CPB time, aortic cross-clamping time and length of hospitalization, but not apolipoprotein epsilon4 genotype were risks for POCD | ||

| Puskas et al.[46], 2007 | Prospective study | 525/0 | Hyperglycemic vs. nonhyperglycemic | 157 (40) vs. 38 (29) at 6 weeks (P=0.017) | Intraoperative hyperglycemia | ||

| Kadoi and Goto[47], 2007 | Prospective study | 106/0 | Sevoflurane vs. non-sevoflurane | 13 (22) vs. 11 (23) in 6 months | Sevoflurane did not have any significant effects on POCD | ||

| Kadoi and Goto[48], 2006 | Prospective study | 88/0 | 24 (27.3) in 6 months | Age, diabetes mellitus and renal failure were associated with POCD at 6 months | |||

| Jensen et al.[49], 2006 | Prospective randomized study | 51/54 | OPCAB vs. CABG | 4 (7.4) vs. 5 (9.8) in 3 months (P=0.7) | No significant difference in the incidence of POCD between OPCAB and CABG | ||

| Silbert et al.[50], 2006 | Prospective randomized study | 326/0 | High-dose fentanyl vs. low-dose fentanyl | 22 (13.7) vs. 40 (23.6) in 1 week (P=0.03) | High-dose fentanyl | Low-dose fentanyl | |

| Wang et al.[51], 2002 | Prospective randomized study | 88/0 | Lidocaine vs. placebo | 8 (18.6) vs. 18 (40.0) at early stage (?) (P=0.028) | Intraoperative administration of lidocaine | ||

CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting; CO2=carbon dioxide; CPB=cardiopulmonary bypass; GFAP=glial fibrillary acidic protein; IL=interleukin; MCI=mild cognitive impairment; NSE=neuron-specific enolase; OPCAB=off-pump coronary artery bypass; POCD=postoperative cognitive dysfunction; POD=postoperative day; rIPC=remote ischemic preconditioning; rSO2=regional cerebral oxygen

Aykut et al.[52] prospectively compared the effect of pulsatile and nonpulsatile flow on cognitive functions of patients undergoing CABG. The cognitive performance was evaluated with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test one day before and one month after the operation. They observed an overall POCD rate of 17.3% in pulsatile and 35.6% in nonpulsatile flow group. Besides, mild cognitive impairment was seen more in the nonpulsatile than in the pulsatile flow group. This result was interpreted as pulsatile flow ensuring a lower systemic vascular resistance and higher oxygen consumption. The pulsatile flow might increase cerebral blood flow, aerobic metabolism, and oxygen delivery, and reduce cerebral vascular resistance[53]. On the contrary, the nonpulsatile flow does not possess these advantages[54]. Pulsatile perfusion preserves microcirculatory perfusion over the conventional nonpulsatile perfusion during CPB. The latter is associated with altered microvascular blood flow, increased leukocyte activation, endothelial dysfunction, and increased microvascular resistance along with elevated lactate as an indicator of tissue hypoxia[55,56].

Some authors reported significant cognitive improvement in the first year follow-up period[57], less cognitive impairment in one week[58], less deteriorated cognitive scores in one and 10 weeks[59], and better neuropsychological performance six months after surgery[19] in OPCAB patients. Emmert et al.[60] reported that on-pump CABG showed an increased risk of postoperative stroke. In contrast, the incidence of stroke was low in patients receiving a standardized OPCAB with no-touch techniques for a proximal anastomosis. They hypothesized that the underlying mechanisms of POCD were probably in virtue of cerebral mircroembolic, inflammatory, and non-physiological perfusion of CPB. However, reports revealed no difference in early postoperative cognitive impairment and late cognitive recovery between on-pump CABG and OPCAB procedures[61-63]. Such inconsistent results were explained by different patient selection criteria and low cardiac output during distal anastomoses in OPCAB[62]. Thus, van Dijk et al.[64] concluded that POCD was insignificantly influenced by CPB. In line with this statement, Selnes et al.[14] claimed that the late POCD was more likely resulted from preexisting cerebrovascular disorders other than from CPB. The possible explanation for this pervasive inconsistency was that different measures were taken concerning the use of unspecified diagnostic criteria for the assessment of POCD[65], incongruousness of definition of cognitive decline, disparity of statistical methods, and lack of randomized control studies[14].

Management

Preventive Measures

Preoperative cognitive screening is a cost-effective way of preventing POCD[14]. Intraoperative monitoring of regional cerebral oxygen saturation against prolonged brain desaturation could be associated with an induced incidence of POCD[66]. The measures for preventing POCD by modifying surgical facilities, such as reducing particulate and gaseous microemboli (by using cardiotomy, cell-saver, arterial line filtration, anastomotic devices and cannulae with modified blood entry and less shear stress, and membrane oxygenator other than bubble oxygenator), hemostasis (by glucose management, temperature regulation and pH management) and surgical techniques, including OPCAB technique, minimized aortic manipulation with single other than multiple aortic clamping[67,68], no-touch technique[34], and pulsatile rather than non-pulsatile CPB[69].

Therapeutic Strategies

Potential pharmacologic strategies include investigational (such as piracetam, cholinesterase inhibitors, glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists, glutamate α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor modulators, γ-aminobutyric acid-B antagonists, nicotinic receptor agonists, dopamine/norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors, Ginkgo biloba, coenzyme Q, antioxidants, and growth factors) and therapeutic agents with neuroprotective effects for immediate treatment of POCD (such as sedatives, acetylcholine sterase inhibitor, stimulants, statins, calcium channel antagonist and N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist)[69]. However, these agents warrant further evaluations with regard to their long-term efficacies[70]. Moreover, investigations have proved that anesthetic preconditioning managements may improve POCD incidence. Royse et al.[71] investigated the influence of propofol or desflurane on POCD incidence and found that desflurane was associated with a reduced incidence of early POCD in comparison to propofol (49.4% vs. 67.5%, P=0.018). This was interpreted as those anesthetics being potentially neurotoxic but sometimes neuroprotective for ischemia-reperfusion injury[72].

The evaluation of anesthetics on cognitive outcome seems to be difficult. This is because anesthetics showed dual neurological impacts: neuroprotective and neurotoxic[73]. Mechanistic studies have been concentrated on ion channels of the nerve cells, particularly on receptors including α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid, γ-aminobutyric acid type A, glycine, 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3, and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors[74]. The neuroprotective effects of anesthetics may rely on the reduction of neuronal excitation and enhancement of γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor function[75]. Anesthetic-induced cognitive impairment probably depends on the type and dose of anesthetics, the mode and route of drug delivery, and observational time[2].

CONCLUSION

The underlying etiologies of POCD following CABG can be complex. A comprehensive postoperative cognitive evaluation with neuropsychiatric tests, cerebral biomarker inspections, and electroencephalographic examination should be performed to assess patients' cognitive status. Inconsistent results of POCD between OPCAB and on-pump CABG warrant further evaluations in well-designed prospective studies. The preventive strategies of modifying surgical facilities and techniques can be effective for preventing the development of POCD. Investigational therapies may offer novel strategies of treatments for POCD. Anesthetic preconditioning might be helpful for the improvement of POCD.

| Authors' roles & responsibilities | |

|---|---|

| SMY | Conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published |

| HL | Conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published |

Footnotes

This study was carried out at The First Hospital of Putian, Teaching Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Putian, Fujian Province, People's Republic of China.

No financial support.

No conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B, Gaver V, Grocott H, Jones RH, et al. Neurological Outcome Research Group and the Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology Research Endeavors Investigators Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(6):395–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jungwirth B, Zieglgänsberger W, Kochs E, Rammes G. Anesthesia and postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009;9(14):1568–1579. doi: 10.2174/138955709791012229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ge Y, Ma Z, Shi H, Zhao Y, Gu X, Wei H. Incidence and risk factors of postoperative cognitive dysfunction in patients underwent coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2014;39(10):1049–1055. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryson GL, Wyand A, Wozny D, Rees L, Taljaard M, Nathan H. A prospective cohort study evaluating associations among delirium, postoperative cognitive dysfunction, and apolipoprotein E genotype following open aortic repair. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58(3):246–255. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Otomo S, Maekawa K, Goto T, Baba T, Yoshitake A. Pre-existing cerebral infarcts as a risk factor for delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;17(5):799–804. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McVeigh C, Passmore P. Vascular dementia: prevention and treatment. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1(3):229–235. doi: 10.2147/ciia.2006.1.3.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rundshagen I. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(8):119–125. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Habib S, Khan Au, Afridi MI, Saeed A, Jan AF, Amjad N. Frequency and predictors of cognitive decline in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2014;24(8):543–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laalou FZ, Carre AC, Forestier C, Sellal F, Langeron O, Pain L. Pathophysiology of post-operative cognitive dysfunction: current hypotheses. J Chir (Paris) 2008;145(4):323–330. doi: 10.1016/s0021-7697(08)74310-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polunina AG, Golukhova EZ, Guekht AB, Lefterova NP, Bokeria LA. Cognitive dysfunction after on-pump operations: neuropsychological characteristics and optimal core battery of tests. Stroke Res Treat. 2014;2014:302824–302824. doi: 10.1155/2014/302824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Harten AE, Scheeren TW, Absalom AR. A review of postoperative cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation associated with cardiac surgery and anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(3):280–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.07008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Dong H, Li N, Zhang S, Sun J, Zhang S, et al. Activated brain mast cells contribute to postoperative cognitive dysfunction by evoking microglia activation and neuronal apoptosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1):127–127. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0592-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kudoh A, Takase H, Katagai H, Takazawa T. Postoperative interleukin-6 and cortisol concentrations in elderly patients with postoperative confusion. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2005;12(1):60–66. doi: 10.1159/000082365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selnes OA, Gottesman RF, Grega MA, Baumgartner WA, Zeger SL, McKhann GM. Cognitive and neurologic outcomes after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(3):250–257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murkin JM, Newman SP, Stump DA, Blumenthal JA. Statement of consensus on assessment of neurobehavioral outcomes after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59(5):1289–1295. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00106-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saraçli Ö, Akca AS, Atasoy N, Önder Ö, Senormanci Ö, Kaygisiz I, et al. The relationship between quality of life and cognitive functions, anxiety and depression among hospitalized elderly patients. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):194–200. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2015.13.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helkala EL, Kivipelto M, Hallikainen M, Alhainen K, Heinonen H, Tuomilehto J, et al. Usefulness of repeated presentation of Mini-Mental State Examination as a diagnostic procedure: a population-based study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002;106(6):341–346. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2002.01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jildenstål PK, Hallén JL, Rawal N, Berggren L. Does depth of anesthesia influence postoperative cognitive dysfunction or inflammatory response following major ENT surgery? J Anesth Clin Res. 2012;3(6):220–220. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroobant N, Van Nooten G, Belleghem Y, Vingerhoets G. Short-term and long-term neurocognitive outcome in on-pump versus off-pump CABG. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22(4):559–564. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benabarre A, Vieta E, Martínez-Arán A, Garcia-Garcia M, Martín F, Lomeña F, et al. Neuropsychological disturbances and cerebral blood flow in bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(4):227–234. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proust-Lima C, Amieva H, Dartigues JF, Jacqmin-Gadda H. Sensitivity of four psychometric tests to measure cognitive changes in brain aging-population-based studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(3):344–350. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reis HJ, Oliveira AC, Mukhamedyarov MA, Zefirov AL, Rizvanov AA, Yalvaç ME, et al. Human cognitive and neuro-psychiatric bio-markers in the cardiac peri-operative patient. Cur Mol Med. 2014;14(9):1155–1163. doi: 10.2174/1566524014666140603114655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan SM. Biomarkers of cerebral injury in cardiac surgery. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2014;14(7):638–645. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.5321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumpaitiene B, Svagzdiene M, Drigotiene I, Sirvinskas E, Sepetiene R, Zakelis R, et al. Correlation among decreased regional cerebral oxygen saturation, blood levels of brain injury biomarkers, and cognitive disorder. J Int Med Res. 2018;46(9):3621–3629. doi: 10.1177/0300060518776545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomaidou E, Argiriadou H, Vretzakis G, Megari K, Taskos N, Chatzigeorgiou G, et al. Perioperative use of erythromycin reduces cognitive decline after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: a pilot study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2017;40(5):195–200. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0000000000000238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kok WF, Koerts J, Tucha O, Scheeren TW, Absalom AR. Neuronal damage biomarkers in the identification of patients at risk of long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction after cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia. 2017;72(3):359–369. doi: 10.1111/anae.13712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva FP, Schmidt AP, Valentin LS, Pinto KO, Zeferino SP, Oses JP, et al. S100B protein and neuron-specific enolase as predictors of cognitive dysfunction after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a prospective observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016;33(9):681–689. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Öztürk S, Saçar M, Baltalarli A, Öztürk I. Effect of the type of cardiopulmonary bypass pump flow on postoperative cognitive function in patients undergoing isolated coronary artery surgery. Anatol J Cardiol. 2016;16(11):875–880. doi: 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2015.6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oldham MA, Hawkins KA, Yuh DD, Dewar ML, Darr UM, Lysyy T, et al. Cognitive and functional status predictors of delirium and delirium severity after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: an interim analysis of the Neuropsychiatric Outcomes After Heart Surgery study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(12):1929–1938. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215001477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hassani S, Alipour A, Darvishi Khezri H, Firouzian A, Emami Zeydi A, Gholipour Baradari A, et al. Can Valeriana officinalis root extract prevent early postoperative cognitive dysfunction after CABG surgery? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232(5):843–850. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong S, Li CL, Liang WD, Chen MH, Bi YT, Li XW. Postoperative plasma copeptin levels independently predict delirium and cognitive dysfunction after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Peptides. 2014;59:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trubnikova OA, Mamontova AS, Syrova ID, Maleva OV, Barbarash OL. Does preoperative mild cognitive impairment predict postoperative cognitive dysfunction after on-pump coronary bypass surgery? J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(Suppl 3):S45–S51. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kok WF, van Harten AE, Koene BM, Mariani MA, Koerts J, Tucha O, et al. A pilot study of cerebral tissue oxygenation and postoperative cognitive dysfunction among patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting randomised to surgery with or without cardiopulmonary bypass. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):613–622. doi: 10.1111/anae.12634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szwed K, Pawliszak W, Anisimowicz L, Bucinski A, Borkowska A. Short-term outcome of attention and executive functions from aorta no-touch and traditional off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2014;15(5):397–403. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2013.824611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fontes MT, McDonagh DL, Phillips-Bute B, Welsby IJ, Podgoreanu MV, Fontes ML, et al. Neurologic Outcome Research Group (NORG) of the Duke Heart Center Arterial hyperoxia during cardiopulmonary bypass and postoperative cognitive dysfunction. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28(3):462–466. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sirvinskas E, Usas E, Mankute A, Raliene L, Jakuska P, Lenkutis T, et al. Effects of intraoperative external head cooling on short-term cognitive function in patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Perfusion. 2014;29(2):124–129. doi: 10.1177/0267659113497074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joung KW, Rhim JH, Chin JH, Kim WJ, Choi DK, Lee EH, et al. Effect of remote ischemic preconditioning on cognitive function after off-pump coronary artery bypass graft: a pilot study. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;65(5):418–424. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2013.65.5.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mu DL, Li LH, Wang DX, Li N, Shan GJ, Li J, et al. High postoperative serum cortisol level is associated with increased risk of cognitive dysfunction early after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kadoi Y, Kawauchi C, Kuroda M, Takahashi K, Saito S, Fujita N, et al. Association between cerebrovascular carbon dioxide reactivity and postoperative short-term and long-term cognitive dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Anesth. 2011;25(5):641–647. doi: 10.1007/s00540-011-1182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Tournay-Jetté E, Dupuis G, Bherer L, Deschamps A, Cartier R, Denault A. The relationship between cerebral oxygen saturation changes and postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2011;25(1):95–104. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slater JP, Guarino T, Stack J, Vinod K, Bustami RT, Brown 3rd JM, et al. Cerebral oxygen desaturation predicts cognitive decline and longer hospital stay after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(1):36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haljan G, Maitland A, Buchan A, Arora RC, King M, Haigh J, et al. The erythropoietin neuroprotective effect: assessment in CABG surgery (TENPEAKS): a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, proof-of-concept clinical trial. Stroke. 2009;40(8):2769–2775. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.549436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silbert BS, Evered LA, Scott DA, Cowie TF. The apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele is not associated with cognitive dysfunction in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(3):841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen BØ, Rasmussen LS, Steinbrüchel DA. Cognitive outcomes in elderly high-risk patients 1 year after off-pump versus on-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. A randomized trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34(5):1016–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hogue CW, Fucetola R, Hershey T, Freedland K, Dávila-Román VG, Goate AM, et al. Risk factors for neurocognitive dysfunction after cardiac surgery in postmenopausal women. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(2):511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puskas F, Grocott HP, White WD, Mathew JP, Newman MF, Bar-Yosef S. Intraoperative hyperglycemia and cognitive decline after CABG. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84(5):1467–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kadoi Y, Goto F. Sevoflurane anesthesia did not affect postoperative cognitive dysfunction in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Anesth. 2007;21(3):330–335. doi: 10.1007/s00540-007-0537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kadoi Y, Goto F. Factors associated with postoperative cognitive dysfunction in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Surg Today. 2006;36(12):1053–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jensen BO, Hughes P, Rasmussen LS, Pedersen PU, Steinbrüchel DA. Cognitive outcomes in elderly high-risk patients after off-pump versus conventional coronary artery bypass grafting: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2006;113(24):2790–2795. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.587931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silbert BS, Scott DA, Evered LA, Lewis MS, Kalpokas M, Maruff P, et al. A comparison of the effect of high- and low-dose fentanyl on the incidence of postoperative cognitive dysfunction after coronary artery bypass surgery in the elderly. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(6):1137–1145. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang D, Wu X, Li J, Xiao F, Liu X, Meng M. The effect of lidocaine on early postoperative cognitive dysfunction after coronary artery bypass surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;95(5):1134–1141. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200211000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aykut K, Albayrak G, Guzeloglu M, Hazan E, Tufekci M, Erdogan I. Pulsatile versus non-pulsatile flow to reduce cognitive decline after coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomized prospective clinical trial. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4(2):127–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jcdr.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Undar A, Eichstaedt HC, Bigley JE, Deady BA, Porter AE, Vaughn WK, et al. Effects of pulsatile and nonpulsatile perfusion on cerebral hemodynamics investigated with a new pediatric pump. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124(2):413–416. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.125209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hickey PR, Buckley MJ, Philbin DM. Pulsatile and nonpulsatile cardiopulmonary bypass: review of a counterproductive controversy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1983;36(6):720–737. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)60286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koning NJ, Vonk AB, van Barneveld LJ, Beishuizen A, Atasever B, van den Brom CE, et al. Pulsatile flow during cardiopulmonary bypass preserves postoperative microcirculatory perfusion irrespective of systemic hemodynamics. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012;112(10):1727–1734. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01191.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'Neil MP, Fleming JC, Badhwar A, Guo LR. Pulsatile versus nonpulsatile flow during cardiopulmonary bypass: microcirculatory and systemic effects. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(6):2046–2053. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee JD, Lee SJ, Tsushima WT, Yamauchi H, Lau WT, Popper J, et al. Benefits of off-pump bypass on neurologic and clinical morbidity: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diegeler A, Hirsch R, Schneider F, Schilling LO, Falk V, Rauch T, et al. Neuromonitoring and neurocognitive outcome in off-pump versus conventional coronary bypass operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69(4):1162–1166. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01574-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zamvar V, Williams D, Hall J, Payne N, Cann C, Young K, et al. Assessment of neurocognitive impairment after off-pump and on-pump techniques for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: prospective randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325(7375):1268–1268. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Emmert MY, Seifert B, Wilhelm M, Grünenfelder J, Falk V, Salzberg SP. Aortic no-touch technique makes the difference in off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142(6):1499–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taggart DP, Browne SM, Halligan PW, Wade DT. Is cardiopulmonary bypass still the cause of cognitive dysfunction after cardiac operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;118(3):414–420. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vedin J, Nyman H, Ericsson A, Hylander S, Vaage J. Cognitive function after on or off pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30(2):305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Dijk D, Jansen EW, Hijman R, Nierich AP, Diephuis JC, Moons KG, et al. Octopus Study Group Cognitive outcome after off-pump and on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2002;287(11):1405–1412. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Dijk D, Moons KG, Keizer AM, Jansen EW, Hijman R, Diephuis JC, et al. Octopus Study Group Association between early and three month cognitive outcome after off-pump and on-pump coronary bypass surgery. Heart. 2004;90(4):431–434. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2002.010173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beratis IN, Papageorgiou SG. Heart surgery and the risk of cognitive decline. Arch Hellenic Med. 2014;31(2):186–190. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Colak Z, Borojevic M, Bogovic A, Ivancan V, Biocina B, Majeric-Kogler V. Influence of intraoperative cerebral oximetry monitoring on neurocognitive function after coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomized, prospective study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47(3):447–454. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hammon JW, Stump DA, Butterworth JF, Moody DM, Rorie K, Deal DD, et al. Single crossclamp improves 6-month cognitive outcome in high-risk coronary bypass patients: the effect of reduced aortic manipulation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131(1):114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ates M, Yangel M, Gullu AU, Sensoz Y, Kizilay M, Akcar M. Is single or double aortic clamping safer in terms of cerebral outcome during coronary bypass surgery. Int Heart J. 2006;47(2):185–192. doi: 10.1536/ihj.47.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Whitaker DC, Stygall J, Newman SP. Neuroprotection during cardiac surgery: strategies to reduce cognitive decline. Perfusion. 2002;17(Suppl):69–75. doi: 10.1191/0267659102pf572oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Raja PV, Blumenthal JA, Doraiswamy PM. Cognitive deficits following coronary artery bypass grafting: prevalence, prognosis, and therapeutic strategies. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(10):763–772. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900022409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Royse CF, Andrews DT, Newman SN, Stygall J, Williams Z, Pang J, et al. The influence of propofol or desflurane on postoperative cognitive dysfunction in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Anaesthesia. 2011;66(6):455–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Piriou V, Chiari P, Gateau-Roesch O, Argaud L, Muntean D, Salles D, et al. Desflurane-induced preconditioning alters calcium-induced mitochondrial permeability transition. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(3):581–588. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200403000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wei H, Inan S. Dual effects of neuroprotection and neurotoxicity by general anesthetics: role of intracellular calcium homeostasis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;47:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sonner JM, Antognini JF, Dutton RC, Flood P, Gray AT, Harris RA, et al. Inhaled anesthetics and immobility: mechanisms, mysteries, and minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(3):718–740. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000081063.76651.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou C, Liu J, Chen XD. General anesthesia mediated by effects on ion channels. World J Crit Care Med. 2012;1(3):80–93. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v1.i3.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]