Watch a video presentation of this article

Abbreviations

- DAA

direct‐acting antiviral

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

Direct‐acting antiviral (DAA) therapy is rightly touted by leading professional societies as an effective public health tool and an integral component of efforts to lower and ultimately eliminate hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s report, A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C, notes that treatment of all individuals with chronic HCV holds the promise of eradicating transmissions.1 Accordingly, a central recommendation of the National Academies’ strategy is that all payers should cover DAA therapy for patients with chronic HCV infections without restriction, save for narrow exceptions where treatment is not medically indicated.1 Despite this recommendation, many payers continue to limit access to DAAs via claims denials.2

Although open access should be offered by all payers, particular attention should be paid to safety net programs such as Medicaid. This is not only due to the fact that higher‐income earners have more control over the delivery of their health care but also because individuals with lower income levels and related socioeconomic determinants are more likely to have an increased risk for transmission and poorer prognosis.3 In the first years after US Food and Drug Administration approval, state Medicaid programs reacted to high introductory list prices by rationing treatment with sofosbuvir based on fibrosis stage, drug and/or alcohol use, and prescriber type.4 In November 2015, a federal agency issued clear guidance to the states, warning that these restrictions violate federal statutory requirements.5 Now, despite drastic reductions in list price, such restrictions on Medicaid coverage remain common.6

We evaluated Medicaid criteria in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. Information was collected via a form survey sent to Medicaid officials and consensus review of publicly available criteria. Data were collected regarding the level of fibrosis required, whether drug and/or alcohol screening or period of abstinence is required prior to authorization, and whether prescribing authority is limited to either a specialist physician or consultation thereof. Initial results were published in October 2017 and updated periodically to account for policy revisions (data and figures presented in this article are current as of April 2018; visit www.stateofhepc.org for the most current information on your state’s treatment criteria).

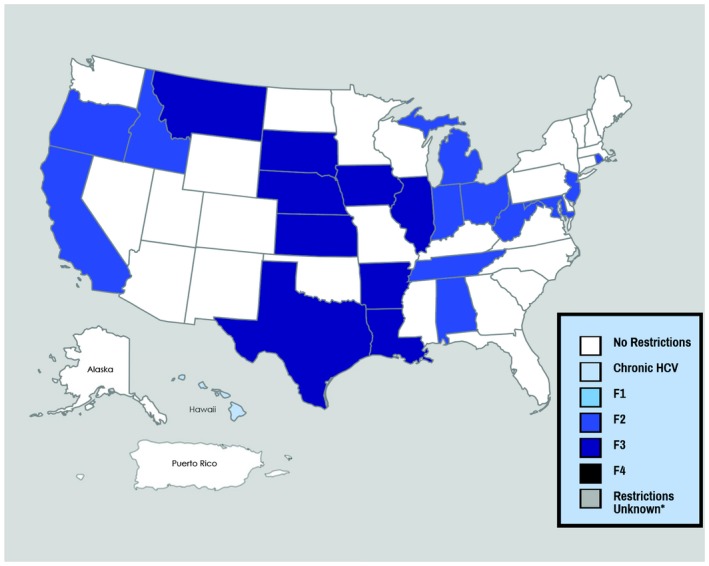

Fibrosis restrictions require patients to wait until HCV damages their liver to a particular degree as measured by the METAVIR fibrosis scale (Fig. 1). Our assessment revealed that 42% of Medicaid programs require a minimum fibrosis score, with the majority of these states requiring documentation of F2 (23%) or F3 (17%). By requiring patients to demonstrate a minimum level of fibrosis, Medicaid programs are forcing already diagnosed individuals to wait until their health declines. Aside from the ethical concerns associated with mandating this deterioration, this is directly counter to guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases/Infectious Diseases Society of America, which describes the standard of care as DAA treatment for all patients with chronic HCV infection without reference to fibrosis score.7 In addition, emerging research suggests that even forgoing treatment until acute HCV progresses to the chronic phase may be less effective, both clinically and economically, than immediate treatment.8

Figure 1.

Fibrosis restrictions.

Sobriety restrictions were found to be similarly prevalent (Fig. 2). Approximately 33% of states require individuals to submit to some form of screening for substance use, and approximately 49% require a period of abstinence from drugs and/or alcohol prior to treatment, with 6 months of abstinence being the most common policy (31%). As with fibrosis minimums, sobriety requirements conflict with the standard of care. Furthermore, because injection drug use is the foremost driving factor in the perpetuation of the HCV epidemic, postponing access to care for people who inject drugs not only allows the health of these individuals to deteriorate but also undermines public health objectives. Adherence concerns with this population are unfounded because people who inject drugs achieve similar cure rates as compared with patients who do not use drugs.9

Figure 2.

Sobriety restrictions.

Restrictions as to prescriber type were found in 73% of states, with 18% limiting reimbursement to specialists, whereas 55% of states require the prescriber to consult a specialist (Fig. 3). Restricting the ability to prescribe DAAs in this manner creates a prescriber bottleneck because specialists often have limited capacity, and patients residing in rural areas face practical access barriers to specialists.

Figure 3.

Prescriber restrictions.

Advances in treatment have presented a realistic possibility of eliminating new HCV transmissions if our health care system can distribute the cure to the populations most affected. However, Medicaid programs continue to deploy restrictive criteria that prevent us from achieving this goal. Physician input is crucial to aligning state Medicaid criteria with the standard of care. As responsible stewards of health, physicians cannot stand by while individuals diagnosed with a deadly infectious disease are forced to wait, suffer progressive liver damage, and risk infecting others.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gowda C, Lott S, Grigorian M, et al. Absolute insurer denial of direct‐acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C: A National Specialty Pharmacy cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018;5:ofy076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Omland LH, Osler M, Jepsen P, et al. Socioeconomic status in HCV infected patients – risk and prognosis. Clin Epidemiol 2013;5:163‐172. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S43926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barua S, Greenwald R, Grebely J, et al. Restrictions for Medicaid reimbursement of sofosbuvir for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:215‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Assuring Medicaid beneficiaries access to hepatitis C (HCV) drugs (Release No.172). Published November 5, 2015. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/hcv/index.html

- 6. New pricing marks potential HCV treatment landscape revolution . Published January 2018. https://www.healio.com/hepatology/hepatitis-c/news/print/hcv-next/%7B12ea032b-37f4-4cc5-8c11-735191858900%7D/new-pricing-marks-potential-hcv-treatment-landscape-revolution

- 7.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases/Infectious Diseases Society of America. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. https://www.hcvguidelines.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. Bethea ED, Chen Q, Hur C, Chung RT, Chhatwal J. Should we treat acute hepatitis C? A decision and cost‐effectiveness analysis. Hepatology 2018;67:837‐848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aspinall EJ, Corson S, Doyle JS, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who are actively injecting drugs: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:S80‐S89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]