Watch a video presentation of this article

Answer questions and earn CME

Abbreviations

- aHSC

activated hepatic stellate cell

- ARB

angiotensin type I–deficient receptor blocker

- CCL

chemokine (C‐C motif) ligand

- CCR2

chemokine (C‐C motif) receptor 2

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- HSC

hepatic stellate cell

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- LOXL2

lysyl oxidase‐like 2

- (PDGF‐β)

platelet‐derived growth factor β

- PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TGF‐β

transforming growth factor β

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Hepatic fibrosis results from repeated liver injury whereby the normal wound‐healing response leads to production and accumulation of connective tissue material, largely composed of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins such as collagen.1 This process may be as a response to infection, inflammation, or normal tissue repair. Resident and recruited cells contribute to this process, leading to excess collagen production and, if left unchecked, may progress to cirrhosis2 (Fig. 1). Recently, a more thorough understanding of the variety and complexity of cell–cell signaling and collagen modification has identified multiple exciting and novel targets for antifibrotic therapy.

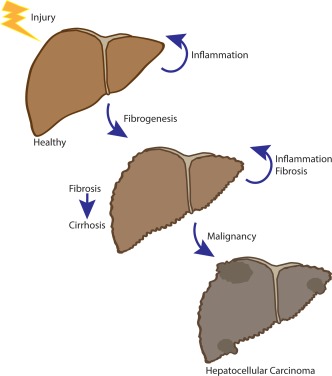

Figure 1.

Hepatic injury may be driven by a variety of insults including viral infection, alcohol, metabolic derangements associated with obesity and steatosis, or autoimmune processes. With repeated injury, the normal wound‐healing response results in profibrogenic and proinflammatory signaling. The tissue response to injury results in a variety of recruited cells that triggers a proinflammatory and profibrogenic signaling cascade that drives fibrosis. Unchecked, fibrosis can result in end‐stage liver disease and/or cirrhosis and, over time, lead to hepatocellular carcinoma.

Numerous injury responses may trigger the activation of resident macrophages (Kupffer cells) or injured hepatocytes, as well as the recruitment of other inflammatory cells (Fig. 2). This inflammatory milieu will, in turn, release reactive oxygen species (ROS) in addition to a variety of cytokines and other soluble factors. These extracellular factors will activate a signaling cascade within hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) that results in a profibrotic phenotype3 (Fig. 3). In normal liver tissue, HSCs are quiescent, located in the space of Disse (a space between sinusoidal endothelial cells and hepatocytes), and comprise approximately 5% of total liver cells.4, 5 Although well known for acting as a reservoir of retinoic acid, HSCs also function to maintain an ECM of different collagen types. Along with portal fibroblasts, activated HSCs (aHSCs) are implicated as cells of origin for myofibroblasts and are thus thought to drive scar formation.6 aHSCs have acquired profibrogenic properties secondary to a variety of inciting stimuli including the aforementioned inflammatory milieu and oxidative stress response. Interestingly, endothelial cells and cholangiocytes are also implicated in driving HSC activation.6 Kisseleva and Brenner7 nicely described targeting HSC activation as shifting the balance toward collagen degradation or halting profibrogenic signaling. Although the most efficacious strategy to date has been to eliminate the injurious cause (classically exemplified by viral hepatitis), new targets are increasingly coming to light. HSCs are an important population and because their activation is a key step in liver fibrosis, targeting their proliferation, migration, and recruitment of other proinflammatory cell types has been intriguing.8 In addition, as a key cell type in fibrosis, understanding the mechanism by which HSCs become activated has remained an area of ongoing interest with exciting therapeutic potential.

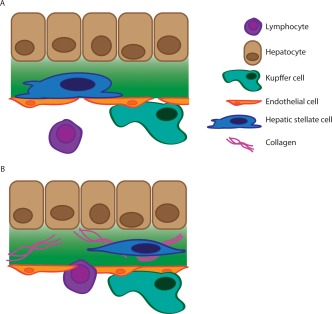

Figure 2.

(A) In normal liver tissue, HSCs are quiescent and reside in the space of Disse, the subendothelial space between hepatocytes and endothelial cells. (B) Liver injury results in HSC activation and in turn multiple inflammatory cells are recruited and migrate across the endothelial layer. Together these cells secrete profibrotic cytokines and result in collagen deposition and modification. As seen, the HSC has changed morphology and is now activated and surrounded by collagen fibrils.

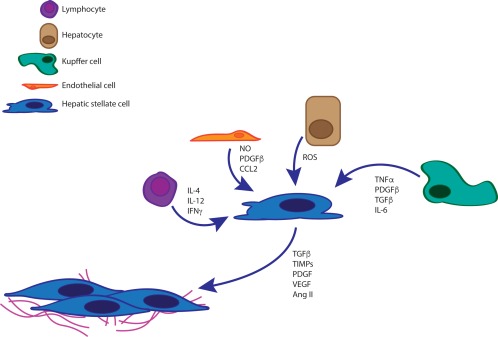

Figure 3.

Multiple cell types interact with HSCs and induce activation. Injury/damaged hepatocytes release ROS as well as other cytokines. Kupffer cells secrete pro‐inflammatory molecules such as TNF‐α, transforming growth factor β (TGF‐β), and interleukin (IL)‐6. Similarly, resident and recruited lymphocytes as well as endothelial cells will also secrete proinflammatory signaling molecules such as nitric oxide (NO), platelet‐derived growth factor β (PDGF‐β), and a variety of ILs including IL‐12 and IL‐4. In turn, aHSCs will become proliferative and adopt a myofibroblast phenotype with collagen production, modification and cross‐linking as a major driver of fibrogenesis. CCL, chemokine (C‐C motif) ligand; IFN, interferon; TIMP, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Recent studies have demonstrated the ability to use tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–related apoptosis‐inducing ligand to decrease collagen production from aHSCs in vitro and induce apoptosis, thus proving a potential therapeutic target to further decrease ECM production.9 Other strategies focus on returning aHSCs to a more quiescent state. One such focus has been peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), a nuclear receptor normally expressed in high amounts in quiescent HSCs. Recent in vitro studies have demonstrated decreased collagen expression in aHSCs when administered PPARγ ligands; however, clinical trials have resulted in mixed outcomes. Administration of pioglitazone, a PPARγ ligand, was associated with reduction in serum alanine and aspartate aminotransferase levels, as well as improvement in inflammation and hepatic steatosis; however without improvement in fibrosis scores in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.10

Recruited and resident inflammatory cells are thought to stimulate HSCs and trigger a profibrogenic signaling cascade. As such, macrophages are of great interest as potential therapeutic targets. Indeed, one ongoing study investigates use of cenicriviroc, a small molecule targeting chemokine receptors chemokine (C‐C motif) receptor 2 (CCR2) and CCR5. Studies in preclinical models of fibrosis and obesity‐associated steatohepatitis demonstrated that use of cenicriviroc was associated with decreased histological evidence of fibrosis and improved insulin resistance.11 Clinical trials are ongoing.

The renin angiotensin system is overexpressed in fibrotic livers, and prior in vivo studies demonstrated efficacy of angiotensin II in driving HSC activation. HSC‐specific angiotensin type I–deficient receptor blockers (ARBs) were studied in a rodent model of hepatic injury and demonstrated reduction in advanced liver fibrosis.12 ARBs are widely available and well studied for their antihypertensive effects, and thus are a promising strategy. Indeed, losartan administration was associated with reduced expression of inflammatory and ECM‐modifying genes in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection; however, long‐term effects on biopsy have yet to be seen.13, 14 Perhaps the most highly anticipated therapeutic has been collagen‐modifying enzymes. One such enzyme, lysyl oxidase‐like 2 (LOXL2), is strongly expressed in fibrotic liver tissue. In multiple mouse models of fibrosis (including both genetic and toxin mediated), the cohort that was treated with an anti‐LOXL2 monoclonal antibody demonstrated decreased fibrosis on histology.15 Interestingly, a small open‐label pilot trial was recently completed, and although the monoclonal antibody simtuzumab was well tolerated, there was no improvement in liver biopsy fibrosis scoring posttreatment.16 The cohort was small and the time course was short, so further studies are clearly indicated.

In summary, liver fibrosis results from multiple different proinflammatory states. Unchecked, this may progress to end‐stage liver disease/cirrhosis and potentially result in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. The inflammatory milieu is composed of many different cell types including, but not limited to, HSCs, Kupffer cells, infiltrating lymphocytes, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells. The crosstalk between these populations occurs via cytokine release and other secreted enzymes. Multiple therapeutic targets have been identified and impact various cells types and signaling molecules within the liver, the most notable being HSCs. Because collagen deposition is a key feature of fibrosis, collagen‐modifying enzymes have been of great therapeutic interest, along with macrophage chemokine receptors and other targets; however, early clinical data are varied and clearly warrant further investigation. As our understanding and appreciation for the varied mechanisms that drive liver fibrosis advances, multipronged therapeutic approaches may prove the most effective. This is an exciting time in hepatology because numerous clinical trials, focused on different aspects of fibrosis and inflammation, are under way.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2005;115(2):209‐218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedman SL. Mechanisms of disease: mechanisms of hepatic fibrosis and therapeutic implications. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;1(2):98‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wu J, Zern MA. Hepatic stellate cells: a target for the treatment of liver fibrosis. J Gastroenterol 2000;35(9):665‐672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yin C, Evason KJ, Asahina K, Stainier DY. Hepatic stellate cells in liver development, regeneration, and cancer. J Clin Invest 2013;123(5):1902‐1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moreira RK. Hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2007;131(11):1728‐1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schuppan D, Kim YO. Evolving therapies for liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2013;123(5):1887‐1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. Hepatic stellate cells and the reversal of fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;21(suppl 3):S84‐S87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bataller R, Brenner DA. Hepatic stellate cells as a target for the treatment of liver fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis 2001;21(3):437‐451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arabpour M, Cool RH, Faber KN, Quax WJ, Haisma HJ. Receptor‐specific TRAIL as a means to achieve targeted elimination of activated hepatic stellate cells. J Drug Target 2017;25:360‐369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sanyal AJ, Chalasani N, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Diehl AM, Bass NM, et al. Pioglitazone, vitamin E, or placebo for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2010;362(18):1675‐1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krenkel O, Puengel T, Govaere O, Abdallah AT, Mossanen JC, Kohlhepp M, et al. Therapeutic inhibition of inflammatory monocyte recruitment reduces steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis. Hepatology; doi: 10.1002/hep.29544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moreno M, Gonzalo T, Kok RJ, Sancho‐Bru P, van Beuge M, Swart J, et al. Reduction of advanced liver fibrosis by short‐term targeted delivery of an angiotensin receptor blocker to hepatic stellate cells in rats. Hepatology 2010;51(3):942‐952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bansal R, Nagorniewicz B, Prakash J. Clinical advancements in the targeted therapies against liver fibrosis. Mediators Inflamm 2016;2016:7629724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Colmenero J, Bataller R, Sancho‐Bru P, Dominguez M, Moreno M, Forns X, et al. Effects of losartan on hepatic expression of nonphagocytic NADPH oxidase and fibrogenic genes in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2009;297(4):G726‐G734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ikenaga N, Peng ZW, Vaid KA, Liu SB, Yoshida S, Sverdlov DY, et al. Selective targeting of lysyl oxidase‐like 2 (LOXL2) suppresses hepatic fibrosis progression and accelerates its reversal. Gut 2017;66(9):1697‐1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meissner EG, McLaughlin M, Matthews L, Gharib AM, Wood BJ, Levy E, et al. Simtuzumab treatment of advanced liver fibrosis in HIV and HCV‐infected adults: results of a 6‐month open‐label safety trial. Liver Int 2016;36(12):1783‐1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]