ABSTRACT

Objective

To describe the availability of local mental health (MH) services in small MH catchment areas in Central Chile, using a bottom-up approach.

Methods

MH services of 19 small MH catchment areas in five health districts of Central Chile that provide health care to more than 4 million inhabitants were assessed using DESDE-LTC (Description and Evaluation of Services and Directories in Europe for Long-Term Care), a tool for standardized description and classification of LTC health services, in a study conducted in 2012 (“DESDE-Chile”) designed to complement other studies conducted in 2004 and 2012 at the national and regional level using the World Health Organization Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS). Key informants from national, regional, and local health authorities were contacted to compile a comprehensive list of MH services or facilities (health, social services, education, employment, and housing). The analysis of local care provision covered three criteria—service availability, placement capacity, and workforce capacity.

Results

The study detected disparities in all three criteria (availability and placement and workforce capacity) across the five health districts, between urban and rural areas, and between neighboring urban areas. Analysis of service availability revealed differences in the weight of residential services versus day and outpatient care. The Talcahuano area could be considered a benchmark of MH care in Central Chile, based on its service provision patterns, and the criteria of the community care model. The list of MH services identified in this study differed from the one generated in the 2012 WHO-AIMS study.

Conclusions

This survey of local MH service provision in small catchment areas using the DESDE-LTC tool provided MH service provision data that complemented information collected in other studies conducted at the national/regional level using the WHO-AIMS tool. The bottom-up approach applied in this study would also be useful for the assessment of equity and accessibility and local planning.

Keywords: Mental health, health services research, evidence-informed policy, health systems, Chile

RESUMEN

Objetivo

Describir, usando un enfoque de abajo arriba, la disponibilidad de servicios locales de salud mental en las pequeñas áreas de captación de salud mental de la zona central de Chile.

Métodos

En un estudio realizado en el 2012 (“DESDE-Chile”), se evaluaron los servicios de salud mental en 19 áreas pequeñas de captación de salud mental de cinco distritos de salud de la zona central de Chile que proporcionan atención de salud a más de 4 millones de habitantes utilizando DESDE-LTC (descripción y evaluación de servicios y guías en Europa para la atención a largo plazo), una herramienta para la descripción y la clasificación estandarizada de servicios de salud a largo plazo. Este estudio se diseñó para complementar otros estudios realizados en el 2004 y el 2012 a nivel nacional y regional usando el Instrumento de Evaluación para Sistemas de Salud Mental de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (IESM-OMS). Se contactó a informantes clave de las autoridades sanitarias nacionales, regionales y locales para compilar una lista integral de los servicios de salud mental o de los establecimientos (salud, servicios sociales, educación, empleo y vivienda). El análisis de la prestación de atención a nivel local abarcó tres criterios: disponibilidad de servicios, capacidad de colocación y capacidad de la fuerza laboral.

Resultados

En el estudio se detectaron disparidades en los tres criterios (disponibilidad, y capacidad de colocación y de fuerza laboral) en los cinco distritos de salud, entre las zonas urbanas y rurales, y entre las zonas urbanas vecinas. El análisis de la disponibilidad de servicios mostró diferencias de peso entre los servicios residenciales y la atención ambulatoria y de día. El área de Talcahuano podría considerarse un punto de referencia para la atención de la salud mental en la zona central de Chile, por su modelo de prestación de servicios y los criterios del modelo de atención comunitaria. La lista de los servicios de salud detectados en este estudio es diferente de la que se generó en el estudio de IESM-OMS del 2012.

Conclusiones

Esta encuesta sobre la prestación de servicios de salud mental a nivel local en áreas pequeña de captación usando la herramienta DESDE-LTC ha proporcionado datos sobre la prestación de servicios de salud mental que complementan la información recopilada en otros estudios realizados al nivel nacional y regional donde se usó la herramienta de IESM-OMS. El enfoque de abajo arriba que se aplicó en este estudio también podría ser útil para evaluar la equidad, la accesibilidad y la planificación local.

Palabras clave: Salud mental, investigación en servicios de salud, política informada por la evidencia, sistemas de salud, Chile

RESUMO

Objetivo

Descrever a disponibilidade de serviços locais de saúde mental em pequenas áreas de cobertura de saúde mental na região central do Chile com o uso de uma abordagem de baixo para cima (bottom-up).

Métodos

Os serviços de saúde mental de 19 pequenas áreas de cobertura de saúde mental em cinco distritos de saúde da região central do Chile que prestam assistência de saúde a mais de 4 milhões de habitantes foram avaliados com o uso da ferramenta DESDE-LTC (Description and Evaluation of Services and Directories in Europe for Long-Term Care – descrição e avaliação de serviços e diretórios na Europa para atenção a longo prazo). Trata-se de uma ferramenta para descrição padronizada e classificação dos serviços de saúde de assistência de longo prazo. Os dados desta avaliação foram comparados aos de um estudo de 2012 (DESDE-Chile) realizado com a finalidade de complementar outros estudos conduzidos em 2004 e 2012 ao nível nacional e regional com o uso do Instrumento de Avaliação dos Sistemas de Saúde Mental da Organização Mundial da Saúde (WHO-AIMS). Neste estudo, foi solicitado aos informantes-chave das autoridades de saúde ao nível nacional, regional e local que fizessem uma relação completa dos serviços ou instituições de saúde mental (das áreas da saúde, assistência social, educação, trabalho e habitação). A prestação de assistência local foi analisada segundo três critérios: disponibilidade de serviços, capacidade de vagas e capacidade da força de trabalho.

Resultados

O estudo verificou, nos cinco distritos de saúde, disparidades nos três critérios (disponibilidade e vagas e capacidade da força de trabalho) entre a zona urbana e rural e entre áreas urbanas vizinhas. A análise da disponibilidade de serviços revelou diferenças no peso entre os serviços residenciais e os serviços de assistência ambulatorial e atenção diária. Talcahuano poderia ser considerada a área de referência em atenção de saúde mental na região central do Chile, segundo os padrões de prestação de serviços e os critérios do modelo de atenção de base comunitária. A lista de serviços de saúde mental identificados no estudo difere da lista compilada no estudo de 2012 com o uso da WHO-AIMS.

Conclusões

Esta pesquisa sobre a prestação local de serviços de saúde mental em pequenas áreas de cobertura com o uso da ferramenta DESDE-LTC proporcionou dados que complementaram os dados coletados em outros estudos realizados ao nível nacional e regional com o uso da ferramenta WHO-AIMS. A abordagem de baixo para cima empregada neste estudo também poderia ser útil na avaliação de equidade e acessibilidade e do planejamento local.

Palavras-chave: Saúde mental, pesquisa sobre serviços de saúde, política informada por evidências, sistemas de saúde, Chile

There is growing interest in developing standardized descriptions of mental health (MH) services that allow for comparisons of MH care systems across regions and countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) was developed to improve comparative descriptions of national MH systems and to identify significant care gaps (1). The MH Atlases produced by WHO have greatly improved the knowledge base on service provision in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) (2–4), which previously consisted of mainly narrative accounts (5, 6). Use of a quantitative approach in the description of services is particularly useful in the context of the MH care reforms occurring in LAC, especially with regard to the integration of MH in community care occurring in countries such as Argentina, Belize, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Panama (6, 4).

However, top-down macro-level descriptions of health systems using national or regional data require complementary bottom-up information on health service availability, capacity, and access in local areas (7). This information needs to be collected from each existing service facility and should include a description of the social and demographic characteristics of the catchment areas.

The characteristics of the health care system in Chile have been extensively documented in the literature (2, 4; 8–10). Chile is organized into 28 autonomous health districts (“Health Services”) managed centrally by the Ministry of Health. A significant proportion of them, but not all, are organized by defined MH catchment areas where care provision is coordinated by a single reference community MH center.

National surveys using the WHO Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS) were carried out in 2004 and 2012. The 2014 WHO-AIMS Chile report included information on Chile's 28 health districts from a study conducted in 2012 (11). The study reported here consisted of three surveys carried out from 2004–2012 and was designed to complement the national/regional WHO-AIMS surveys. The first survey, conducted in 2004–2005, collected data on two MH catchment areas in the Biobío region, Talcahuano and Concepción (12). The second and third surveys—one in 2008–2009 (13) and one in 2012—collected data across five health districts in Central Chile. The first survey compared data on local MH service provision from Spain and Chile in order to identify Chilean care gaps and shortcomings in service provision (12). It also highlighted the feasibility of the bottom-up, meso-level approach for collecting local MH service data using standard procedures and tools such as the ESMS (European Service Mapping Schedule) (14) and the DESDE-LTC (Description and Evaluation of Services and Directories in Europe for Long-Term Care) (15). The three surveys on local MH service provision in Chile thus became known collectively as the “DESDE-Chile” study. The results reported below are from the third survey, conducted in 2012.

The goal of the 2012 DESDE-Chile survey was to describe the availability of local MH services in small MH catchment areas in Central Chile, using a bottom-up approach.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The 2012 DESDE-Chile survey was an ecological study of local MH care systems that used standardized MH service descriptions to compare service availability and capacity in Central Chile, one of three natural regions of continental Chile that comprises the metropolitan areas of Santiago, Valparaiso, and Concepción-Talcahuano. Two-thirds of the country's population lives in this geographic zone, mainly in Santiago.

Assessment and classification of services

The DESDE-LTC tool used in the survey is the extended version of the ESMS, which was designed to assess adult MH care services (14). DESDE-LTC expanded the original set of 32 codes to 91 to allow for coding of services for other 1) sectors (education, employment, and crime and justice); 2) population groups (children and adolescents, elderly, people with alcohol and other drug (AOD) problems); and 3) health targets (disability and long-term chronic care). ESMS and DESDE-LTC have shown high levels of feasibility, reliability, and validity (14–17). These instruments have been used in more than 13 countries for regional, national, and international comparisons of MH systems and LTC (15).

The ESMS/DESDE system identifies standard, minimum units of production of care called Basic Stable Inputs of Care (BSICs) that are coded according to their key function or Main Types of Care (MTCs) (15, 18). DESDE-LTC uses a tree taxonomy system to classify services in a defined catchment area by main care structure/activity offered and level of availability (DESDE-LTC section B) and use (section C). The mapping trees include six main branches: 1) information for care, 2) accessibility to care, 3) self-help and voluntary care, 4) outpatient care, 5) day care, and 6) residential care. The 2012 DESDE-Chile survey covered the last three service types because they are priority subjects for MH planning. The terms used by DESDE-LTC are described in the European Union REFINEMENT Project's Glossary of Terms (international terminology for mental health systems assessment).a A summary of the Glossary's most relevant terms and units of analysis are available elsewhere (19).

Study areas

The 2012 DESDE-Chile survey was carried out in three administrative regions in Central Chile: Biobío, Metropolitan (Santiago de Chile), and Maule. Five of the 12 health districts in those regions were selected for the study: two in the Biobío region (Concepción and Talcahuano) and two in the Santiago de Chile metropolitan region (Metropolitano Oriente and Metropolitano Sur) plus the sole health district of the rural Maule region (Maule district). The five districts were selected for their diversity, with the assistance of a group of public health experts and decision-makers, to reflect sociodemographic differences across the Central Chile region, so their service patterns may not be representative of those in other districts and/or the region as a whole.

The selection of study areas took into account the variability in social and demographic characteristics across the different jurisdictions; disparities in the local development of community care (organization and service provision); and the availability of local information on service utilization.

Following DESDE-LTC criteria, the five health districts were divided into 19 small MH catchment areas: Concepción (4), Talcahuano (3), Metropolitano Oriente (8), Metropolitano Sur (1), and Maule (3). It should be noted that Metropolitano Sur was divided into smaller catchment areas covered by community MH centers after 2012 but functioned as a single district when the data were collected during 2012.

Procedure

Key informants from the National Department of Mental Health and regional and local health and social agencies were contacted for assistance in compiling a comprehensive list of all facilities providing MH services in each district (health services, social services, education, employment, and housing). Managers of those MH services then provided information on the structure and organization of their facility. This included location, administration, temporal stability, placement capacity, staff, governance, and financing mechanisms. Generic services (e.g., general primary and hospital care) were not included in the study unless they had specific BSICs for MH. The mapping also included services where at least 20% of users were assisted for an MH problem.

The assessment covered MH and AOD services for 1) adults and 2) children and adolescents. The information provided here covers services for each of the 19 small MH catchment areas and aggregated services at the district level. Social and demographic indicators relevant to MH care planning (20) were collected from Chile's National Statistics Institute based on the National Population and Housing Census of 2002 (21) and its projections to 2012 (22). “Service availability” was defined as the number of MTCs available per health district. “Placement capacity” refers to the number of beds in hospitals or residential facilities (“beds”) and assigned places in day care centers, day hospitals, and other support services (“places”) per health district. “Workforce capacity” refers to the number of professionals measured in full-time equivalents (FTEs) per health district. For comparison purposes, rates per 100 000 population per age group were calculated for the three measures.

The three branches of care selected from the DESDE-LTC (residential, day, and outpatient) were grouped into 14 categories based on MH service coding: acute hospital care, non-acute hospital care; community acute care alternatives to hospitalization, community non-acute care alternatives to hospitalization; acute day care, non-acute health-related day care (psychosocial rehabilitation units); work-related (ordinary and supported employment) day care, other types of day care; mobile acute outpatient care, non-mobile acute outpatient care; mobile non-acute outpatient care, non-mobile non-acute outpatient care; and high-intensity (services offering 24-hour support) non-hospital residential care and other types of non-hospital residential care.

In the last phase of the assessment, the data were aggregated at the district level and service availability compared across the five health districts. Testing of the semantic equivalence of the terms in the DESDE-LTC and WHO-AIMS instruments was carried out by the authors for comparisons of the service availability data that were generated using the two different approaches. ESMS, the precursor to the DESDE-LTC, was one of the tools used in the development of WHO-AIMS, which facilitated this process.

This research did not use individual patient data, was conducted in an ethical and responsible manner, and complied with all relevant legislation.

RESULTS

Social and demographic indicators

The five health districts studied have a population close to 4.2 million, which is 32.5% of the total population of Central Chile and 23.9% of the total population of Chile. Table 1 lists the five health districts and 19 small MH catchment areas and provides information on the social and demographic indicators in these jurisdictions. Metropolitano Oriente and Metropolitano Sur in Santiago de Chile and two small catchment areas of the Talcahuano health district (Talcahuano and Hualpén) are densely populated. Metropolitano Oriente had the highest aging index, the lowest illiteracy rate and unemployment rate, and the highest rate of one-person households and unmarried individuals. The Maule health district, which is rural, and encompasses three catchment areas, had the highest rate of illiteracy and unemployment and the highest dependency index.

TABLE 1. Socio-demographic data for 19 small mental health (MH) catchment areas in five health districts, Central Chile, 2012.

| Health district | Small MH catchment area | Surface area (km2) | Inhabitants | Population density (inhabitants/ km2) | Dependency ratio | Aging ratio | Non-married rate | Unemployment rate | Single household rate | Single-parent household rate | Illiteracy rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepción | Concepción | 2 275.9 | 419 468 | 184.3 | 51.53 | 30.89 | 48.36 | 7.08 | 10.83 | 10.59 | 3.61 |

| Coronel | 415.2 | 144 617 | 348.3 | 56.41 | 24.51 | 44.48 | 7.72 | 8.41 | 10.30 | 4.93 | |

| San Pedro | 112.5 | 80 447 | 715.1 | 53.65 | 19.65 | 45.10 | 7.53 | 7.69 | 11.42 | 3.52 | |

| Total | 2 803.6 | 644 532 | 229.9 | 52.75 | 27.62 | 47.1 | 7.3 | 9.9 | 10.6 | 3.9 | |

| Talcahuano | Penco | 107.6 | 46 016 | 427.7 | 51.55 | 23.55 | 45.95 | 7.80 | 8.21 | 10.36 | 4.10 |

| Talcahuano | 92.3 | 172 097 | 1 864.5 | 46.37 | 27.50 | 46.86 | 7.31 | 8.02 | 10.50 | 2.73 | |

| Tomé | 494.5 | 52 440 | 106.1 | 57.78 | 34.28 | 47.28 | 8.62 | 11.04 | 10.03 | 5.33 | |

| Hualpéna | 53.5 | 85 110 | 1 590.8 | 46.61 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Total | 747.9 | 355 663 | 466.4 | 52.79 | 28 | 48.8 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 10.4 | 3.3 | |

| Metropolitano Sur | Metro. Surb | 519.6 | 1 175 533 | 2 262.5 | 55.68 | 31.59 | 46.62 | 7.72 | 9.49 | 9.61 | 3.23 |

| Metropolitano Oriente | La Reina | 23.4 | 96 762 | 4 135.1 | 50.95 | 39.85 | 49.31 | 5.21 | 8.98 | 11.41 | 1.20 |

| Las Condes | 99.4 | 249 893 | 2 514.0 | 47.22 | 54.45 | 51.43 | 4.41 | 17.50 | 10.85 | 0.57 | |

| Lo Barnechea | 1 023.7 | 74 749 | 73.0 | 52.06 | 13.13 | 48.49 | 4.18 | 7.92 | 9.75 | 2.01 | |

| Macul | 12.9 | 112 535 | 8 723.6 | 50.37 | 44.53 | 49.45 | 7.12 | 11.24 | 10.82 | 2.12 | |

| Ñuñoa | 16.9 | 163 511 | 9 675.2 | 52.39 | 78.86 | 53.74 | 5.63 | 18.02 | 11.91 | 0.82 | |

| Peñalolén | 54.2 | 216 060 | 3 986.4 | 53.22 | 19.10 | 44.35 | 7.85 | 8.63 | 9.75 | 3.43 | |

| Providencia | 14.4 | 120 874 | 8 394.0 | 46.35 | 117.96 | 57.85 | 4.62 | 30.24 | 9.56 | 0.43 | |

| Vitacura | 28.3 | 81 499 | 2 879.8 | 46.71 | 51.56 | 51.73 | 3.60 | 14.38 | 11.70 | 0.42 | |

| Total | 1 273.2 | 1 115 883 | 876.4 | 49.93 | 46.83 | 50.8 | 5.5 | 15.8 | 10.7 | 1.4 | |

| Maule | Curicó | 7 280.9 | 244 053 | 33.5 | 55.60 | 27.96 | 43.89 | 6.94 | 11.05 | 8.60 | 8.52 |

| Linares | 10 050.2 | 253 990 | 25.3 | 60.34 | 30.57 | 44.27 | 7.77 | 11.38 | 9.66 | 9.24 | |

| Talca | 12 965.0 | 410 054 | 31.6 | 57.96 | 28.59 | 45.13 | 8.09 | 11.82 | 9.60 | 7.76 | |

| Total | 30 296.1 | 908 097 | 30.0 | 57.97 | 28.99 | 44.6 | 7.7 | 11.5 | 9.4 | 8.4 |

Source: Prepared by the authors using data from the XVII National Population and Housing Census 2002 (21); and CELADE (ECLAC) 2002–2006 (22).

Talcahuano was divided into two municipalities in 2006 (Talcahuano and Hualpén), but no official, separate demographic data were available at the time of the study.

In 2012, Metropolitano Sur functioned as a single health district (after 2012, it was divided into smaller catchment areas covered by community MH centers).

Service distribution by health district

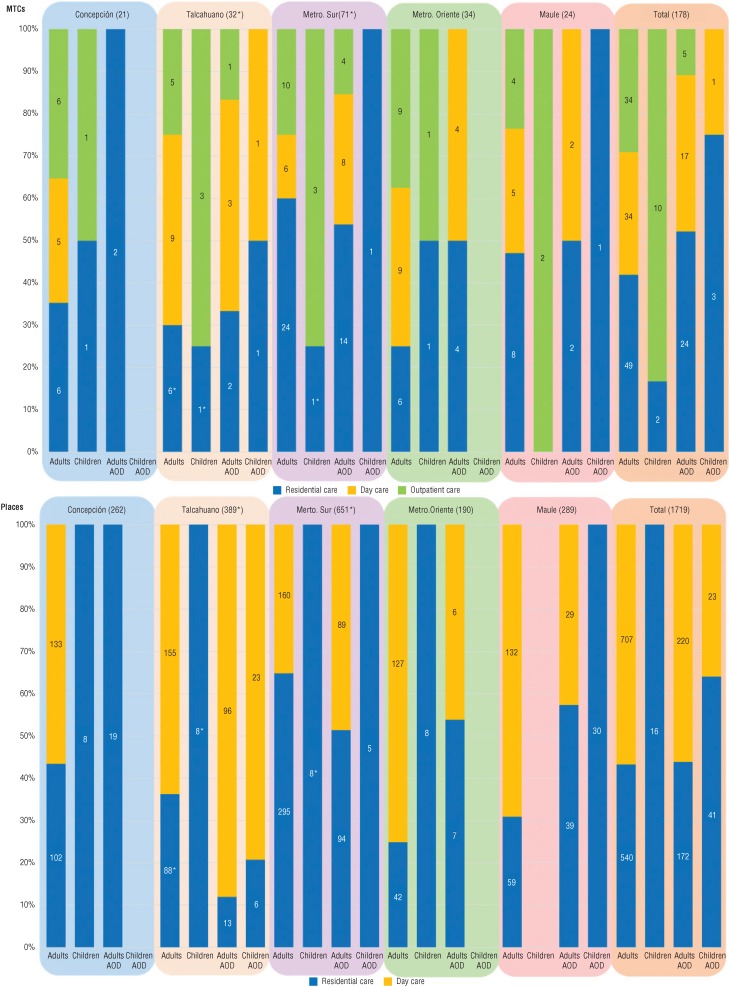

Figure 1 shows the number and proportion of services providing the three MH branches of care covered in this study (residential, day, and outpatient) and the places and beds in the five districts studied for four target populations: 1) adults, 2) children and adolescents, 3) adult AOD patients, and 4) child and adolescent AOD patients.

FIGURE 1. Service availability (number and proportion (%) of Main Types of Care (MTCs) in residential, day, and outpatient carea) and placement capacity (number of beds in hospitals and other types of residential carea and assigned places in day care, day hospitals, and other support servicesa) for four target populationsb in five health districts, Central Chile, 2012.

* Health districts with residential services outside the district boundaries.

a Defined by the DESDE-LTC (Description and Evaluation of Services and Directories in Europe for Long-Term Care) tool (14).

b Adults; children and adolescents (“children”); adult drug and alcohol patients (“adults AOD”); and child and adolescent AOD patients (“children AOD”).

Source: Prepared by the authors using data from this study.

Most facilities providing MTCs were in metropolitan areas. Metropolitano Sur had 39.3% of the MTC capacity, followed by Metropolitano Oriente and Talcahuano (with 19.1% and 16.9% respectively); Maule and Concepción had only 13.5% and 11.8% of the MTCs.

Balance of care was analyzed by comparing the proportion of MTCs for the three branches of care (residential, day, and outpatient) in each health district and major differences across the five health districts were revealed. Most local availability of MTCs for the adult population in Metropolitano Sur (60.0%) was residential care, which only represented 25.0% of MTCs in the neighboring district of Metropolitano Oriente. The reverse was true for adult outpatient care, which was 37.5% of all MTCs in Metropolitano Oriente, 25.0% in Metropolitano Sur, and the lowest—23.5%—in Maule. Day care comprised a low proportion of MH service provision in Metropolitano Sur (15.0%) and a high proportion in Talcahuano (47.4%).

There was high disparity in services for children and adolescents across the 19 small catchment areas. While urban areas offered residential and community services for this population group, the Maule district only offered outpatient care. The study did not identify any day care services for this population group.

Care designated for adults with AOD problems was found in all five districts, although only Talcahuano and Metropolitano Sur had MTCs of the three branches of care (residential, day, and outpatient) for this population group. Concepción only had residential services for AOD. Addiction services for children and adolescents were not available in Concepción and Metropolitano Oriente; Talcahuano had day care for this group.

There were substantial differences in placement capacity (beds/places) across the five districts. Metropolitano Sur had the highest percentage of residential beds for adults (64.8%) while Talcahuano had the highest proportion of day care places (63.8%). Balance of care was achieved in addiction services in all districts except Talcahuano, where day care placement capacity was higher than that of residential care (88.1%).

Rates of MH care provision

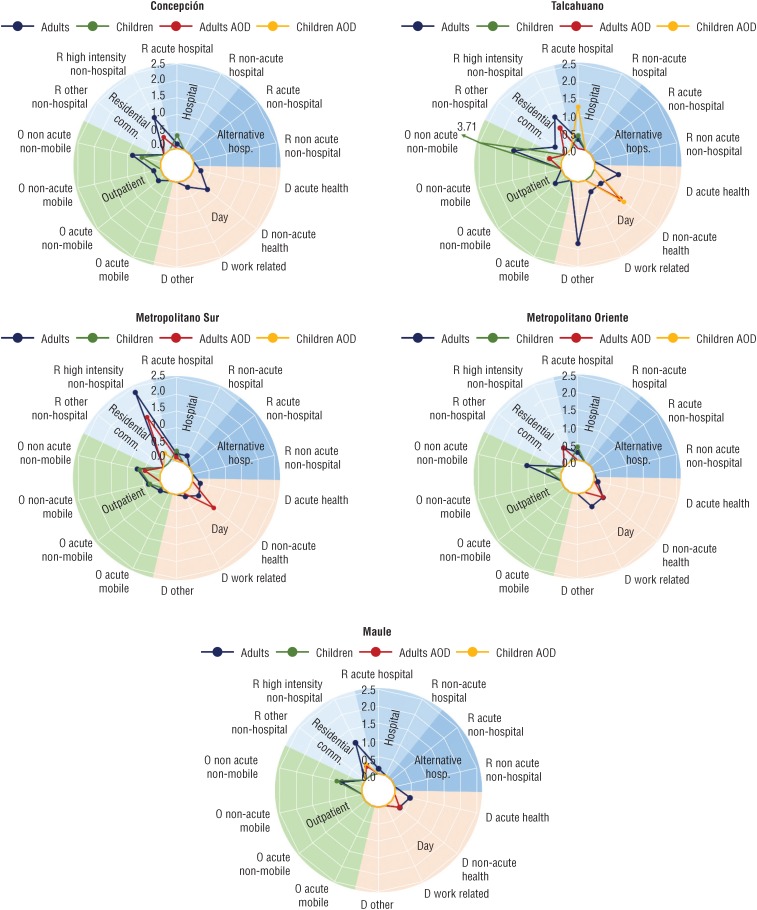

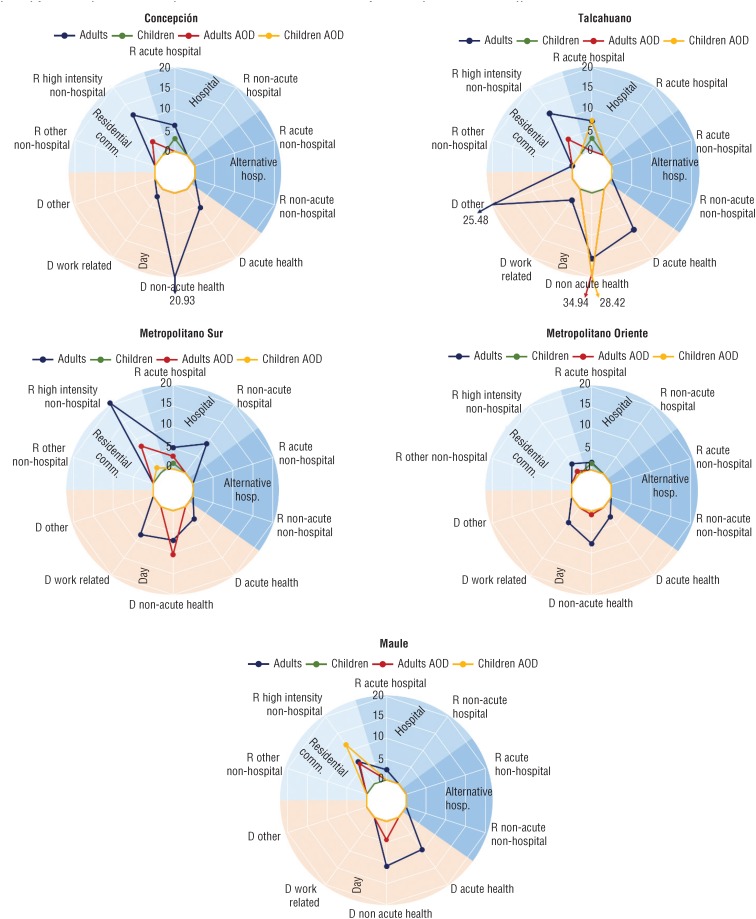

Figures 2–4 show service availability, placement capacity (beds/places), and workforce capacity (in FTEs) per 100 000 population for each of the three branches of care and four target groups.

FIGURE 2. Pattern of mental health (MH) service availability (ratea of Main Types of Care (MTCs) in groups of residential, day, and outpatient careb) for four target populations (adults; children and adolescents (“children”); adult alcohol and other drug (AOD) patients (“adults AOD”); and child and adolescent AOD patients (“children AOD”)) in five health districts, Central Chile, 2012.

a Number of MTCs per 100 000 population of adults (> 15 years old) and children and adolescents (≤ 15 years old).

b Groups defined by the DESDE-LTC (Description and Evaluation of Services and Directories in Europe for Long-Term Care) tool (14).

Source: Prepared by the authors using data from this study.

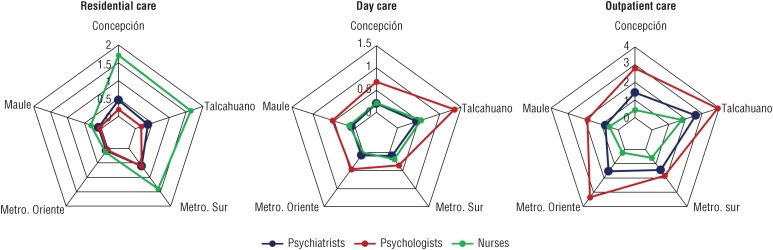

FIGURE 4. Workforce capacity (ratea of psychiatrists, psychologists, and nurses in groups of residential, day, and outpatient careb) for adults in five health districts, Central Chile, 2012.

a Number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) per 100 000 population (> 15 years old).

b Groups defined by the DESDE-LTC (Description and Evaluation of Services and Directories in Europe for Long-Term Care) tool (15).

Source: Prepared by the authors using data from this study.

Residential care

Residential MH care for adults is shown in Figure 1. Talcahuano had two acute hospital units (0.27 per 100 000 population) but one was located in the neighboring district of Concepción. Only Metropolitano Sur offered non-acute hospital care. The majority of the residential MTCs were provided through non-acute residential care facilities with high supervision (labeled as “R high intensity, non-hospital” in Figure 2). The district with the highest placement capacity was Metropolitano Sur (2.34) while the one with the lowest was the neighboring district of Metropolitano Oriente (0.46) (Figure 3). The highest capacity of acute hospital beds was in the districts of Talcahuano (7.27), Concepción (6.19), and Metropolitano Sur (5.14).

FIGURE 3. Pattern of mental health (MH) service placement capacity (ratea of beds in groups of residential careb and assigned places in groups of day careb) for four target populations (adults; children and adolescents (“children”); adult alcohol and other drug (AOD) patients (“adults AOD”); and child and adolescent AOD patients (“children AOD”)) in five health districts, Central Chile, 2012.

a Number of MH service beds/assigned places available per 100 000 population of adults (> 15 years old) and children and adolescents (≤ 15 years old).

b Groups defined by the DESDE-LTC (Description and Evaluation of Services and Directories in Europe for Long-Term Care) tool (14).

Source: Prepared by the authors using data from this study.

The data for residential care for children and adolescents shown in Figure 2 do not include an acute care hospital unit assigned to Maule but located in Concepción (according to DESDE-LTC criteria, facilities outside the borders of a jurisdiction are only included when they are within 100 km of the catchment area, and services are used on a routine basis). The acute unit in Concepción also delivers care to Talcahuano, which is within the 100-km range, so it was included in the data for that district. Metropolitano Oriente and Metropolitano Sur also share an acute care unit for children and adolescents. The highest rates of bed availability for children and adolescents in acute care hospitals were in Concepción and Talcahuano (3.11 for both).

Metropolitano Sur was the only one of the five health districts with acute hospital care for adults with AOD problems. High-intensity non-acute residential care for this population group was available in all districts, with the highest availability and placement capacity in Metropolitano Sur (1.52 and 7.94 respectively), and a very low rate for this service in Metropolitano Oriente (0.81). Talcahuano had acute hospital services designated for children and adolescents with AOD problems, and Metropolitano Sur and Maule had low-intensity non-acute residences. Maule had the highest bed availability rate for this target group (11.61).

Day care

Day care was available in all districts. Talcahuano had a high availability of acute day care for adults (0.73) and was the only district with non-health-related and non-work-related services for this type of care (labeled as “D other” in Figure 2). Availability of health-related day care was higher in Concepción (0.64), while work-related day care was higher in Metropolitano Oriente (0.46). Talcahuano showed a high placement capacity for acute health-related day care (12.01) and non-acute health-related day care (15.65), although placement capacity for this latter type of care was highest in Concepción (20.93). Work-related day care was more prominent in Metropolitano Sur (8.18).

Talcahuano was the sole district with day care for children and adolescents, and it included AOD care. Non-acute health-related day care for adults with addictions was available in all districts except Concepción. Talcahuano had the highest service availability (1.09) and placement capacity (34.94), while Metropolitano Oriente had the lowest placement capacity (0.70).

Outpatient care

All five districts offered outpatient care in community MH centers. Talcahuano and Metropolitano Oriente had the highest availability rate (1.46 and 1.04 respectively). Non-acute mobile services were available in Concepción and Metropolitano Sur. Acute outpatient non-mobile care was available in all districts except Metropolitano Oriente and Maule.

Non-mobile outpatient care for children and adolescents was also provided in all five districts, with more availability in Talcahuano (3.71). Mobile outpatient care for children and adolescents was only available in Metropolitano Sur. Non-acute and non-mobile outpatient facilities for substance abuse were only available in Talcahuano and Metropolitano Sur. No outpatient services were designated for children and adolescents with AOD problems.

Workforce capacity

Figure 4 shows workforce capacity in FTEs per 100 000 population for each health district and by type of care. Concepción, Talcahuano, and Metropolitano Sur had the highest rates of psychiatrists, psychologists, and nurses working in residential care, with the last area having the highest proportion of all three. Talcahuano had better workforce capacity in day care and, with Metropolitano Oriente, the highest workforce capacity in outpatient care.

Comparison with national data

To allow for comparison, the DESDE-LTC data were aggregated into eight groups and matched with semantically equivalent services described in the 2014 WHO-AIMS Chile report (11). Placement and workforce capacity could not be compared due to the lower level of granularity and lack of information on FTEs at the macro-level in the WHO-AIMS data. This information is shown in Table 2. Although the results of this comparison should be interpreted with caution, major differences can be seen in the comparison of acute hospital care,b community residential care, health-related day care, and outpatient care. There were also differences in the data for outpatient care, with the WHO-AIMS numbers for Metropolitano Oriente higher than those from the DESDE study.

TABLE 2. Number of services providing adult mental health (MH) care identified in DESDE-Chilea and WHO-AIMSb surveys in five health districts, Central Chile, 2012.

| Type of adult MH care | Survey | Health district | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepción | Talcahuano | Metro. Sur | Metro. Oriente | Maule | |||

| Residential | |||||||

| Acute hospital | DESDE-Chile | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| WHO-AIMS | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Non-acute hospital | DESDE-Chile | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| WHO-AIMS | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other residential | DESDE-Chile | 5 | 4 | 20 | 4 | 7 | |

| WHO-AIMS | 4 | 6 | 24 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Day | |||||||

| Acute | DESDE-Chile | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| WHO-AIMS | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Health-related | DESDE-Chile | 3 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| WHO-AIMS | 3 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Outpatient | |||||||

| Community | DESDE-Chile | 6 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 4 | |

| WHO-AIMS | 8 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 8 | ||

Source: Prepared by the authors using data from this study (“DESDE-Chile”) and the WHO-AIMS Chile report (11).

Study of local MH care provision using the DESDE-LTC (Description and Evaluation of Services and Directories in Europe for Long-Term Care) survey instrument.

World Health Organization Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems.

DISCUSSION

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the DESDE-Chile study is the most extensive regional analysis of MH service availability and capacity based on a bottom-up comparison of small MH catchment areas (meso-level) and health districts (macro-level) in LAC. The study is also aligned with the WHO Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020, which recommends the development of comprehensive community-based MH and social care services (23). Detailed analysis of health districts and services for specific population groups such as children and adolescents is also a main recommendation of the 2014 WHO-AIMS Chile report (11). The WHO-AIMS surveys for 2004 and 2012 and bottom-up analysis carried out by the DESDE-Chile surveys in 2005, 2009, and 2012 coincided with an intensive planning effort carried out in Chile and provided complementary evidence on the overall increase in MH service availability and capacity. Determining the rate of improvement in equity and access will, however, require additional, specially designed research, with a focus on rural areas.

The survey results showed significant variability in service provision across the five health districts, including between neighboring districts such as Metropolitano Sur and Oriente in Santiago, and between Talcahuano and Concepción. There was also significant disparity between the urban areas and the rural district of Maule. The Talcahuano health district, on the other hand, showed a pattern of service provision closer to the basic community MH care model (24).

The use of both a top-down (6, 11) and bottom-up (12, 13) approach strengthened the study for several reasons. First, the use of national data for the description of service provision is subject to bias due to the ecological effect (25). Second, information at the macro-level cannot be used for local resource allocation and planning. Third, top-down information is hampered by commensurability and transferability biases. Commensurability bias is produced by the lack of a common unit of analysis to allow like-with-like comparisons in the evaluation of services. Transferability bias can occur due to terminology variance and the fact that the names of the services do not always correspond to the activity they provide in the real world (18). The ESMS/DESDE system helps minimize commensurability bias by describing standard units of analysis (BSICs) that can be compared across different jurisdictions and settings. Transferability bias was addressed with the use of the DESDE taxonomy coding using the standardized MTCs. The ESMS/DESDE approach uses these codes and standardized terms/categories to provide an operational description of the local system based on “what is done” (MTCs) by every “functional unit of provision of care” (BSIC) identified in the local health area. This approach allows for aggregation of data at different levels of the health system (meso and macro).

Limitations

A number of study limitations should be taken into account. First, the service provision mapping did not include primary care or care provided by the private sector (i.e., out-of-pocket payments and private insurance). Second, only selected areas of Central Chile were mapped, so no assertions can be made about patterns of service provision for Central Chile overall. Third, the analysis of MH services for specific population groups was limited to children and adolescents, and AOD patients; it did not include any other target groups (e.g., first nation/indigenous populations or persons with intellectual disabilities and MH disorders).

Conclusions

This local survey of MH service provision in small catchment areas in Central Chile generated useful information and new organizational learning on the provision of MH care, complementing data collected in other surveys at the national and regional level. Use of the DESDE-LTC and the ESMS/DESDE tools allows for comparison of identified patterns of care in selected areas of Chile with those found in selected areas in Europe (20) and Australia (26). This bottom-up approach is useful for assessing health service equity and accessibility, and for local planning.

Recommendations

Standard descriptions of local context for MH services can provide data for new service research studies that help support evidence-informed MH policy (7). The results from this study may be relevant for MH service policy in LAC, given the leading role of Chile, with Brazil and Panama, in regional MH planning (5). The data reported here could also be used in combination with data on service utilization to produce bottom-up key performance indicators, and for the development of decision support systems to guide evidence-informed policy (24, 27, 28).

Acknowledgments

This study was coordinated by members of the Psicost Research Association (Spain). The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Olga Toro, Claudia Carniglia, Marcela Ormazabal, and Edith Albornoz. The study was developed within the framework of FONDECYT (National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development) research project #1030605 (Evaluación de patrones de uso de servicios y costos asociados, en dos muestras de pacientes con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia), funded by CONICYT (National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research), and the Inter-Cooperation Program projects #A/013204/07 and #A/019376/08 (Comparación de la disponibilidad y utilización de servicios de salud mental en áreas sanitarias de Chile y España), funded by the AECID (Spanish Cooperation Agency for International Development). The authors also thank the Chilean Ministry of Health for the additional financial support.

Footnotes

Suggested citation Salinas-Perez JA, Salvador-Carulla L, Saldivia S, Grandon P, Minoletti A, Romero Lopez-Alberca C. Integrated mapping of local mental health systems in Central Chile. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2018;42:e144. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2018.144

One acute hospital in Talcahuano identified in this study did not appear in the WHO-AIMS inventory.

Disclaimer. Authors hold sole responsibility for the views expressed in the manuscript, which may not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of the RPSP/PAJPH or the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization . mhGAP Mental Health Gap Action Programme. Scaling up care for mental, neurological and substance use disorders [Internet] Geneva: WHO; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap_final_english.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Mental Health Atlas 2005 [Internet] Geneva: WHO; 2005. [[cited 2013 Aug 21]]. 82 p. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/mhatlas05/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saxena S, Lora A, van Ommeren M, Barrett T, Morris J, Saraceno B. WHO's Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems: collecting essential information for policy and service delivery. Psychiatr Serv. 2007 Jun;58(6):816–821. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saxena S, Lora A, Morris J, Berrino A, Esparza P, Barrett T, et al. Mental health services in 42 low- and middle-income countries: a WHO-AIMS cross-national analysis. Psychiatr Serv. 2011 Feb;62(2):123–125. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.2.pss6202_0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minoletti A, Galea S, Susser E. Community mental health services in Latin America for people with severe mental disorders. Public Health Rev. 2012;34(2) doi: 10.1007/BF03391681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razzouk D, Gregório G, Antunes R, Mari JDEJ. Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in Latin American and Caribbean countries. World Psychiatry. 2012 Oct;11(3):191–195. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2012.tb00130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewin S, Oxman AD, Lavis JN, Fretheim A, Garcia Marti S, Munabi-Babigumira S, et al. SUPPORT tools for evidence-informed policymaking in health 11: Finding and using evidence about local conditions. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2009;7(Suppl 11):S11–S11. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-7-S1-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araya R, Alvarado R, Minoletti A. Chile: an ongoing mental health revolution. 9690. Vol. 374. Lancet; London, England: 2009. Aug, pp. 597–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . Mental Health Atlas 2011 [Internet] Geneva: WHO; 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/mental_health_atlas_2011/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . Mental Health Atlas 2014 [Internet] Geneva: WHO; 2015. [[cited 2013 Aug 21]]. 82 p. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/mental_health_atlas_2014/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minoletti A, Alvarado R, Rayo X, Minoletti M. Evaluación del Sistema de Salud Mental en Chile. Santiago: Ministerio de Salud, Gobierno de Chile; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvador-Carulla L, Saldivia S, Martinez-Leal R, Vicente B, Garcia-Alonso C, Grandon P, et al. Meso-level comparison of mental health service availability and use in Chile and Spain. Psychiatr Serv. 2008 Apr;59(4):421–428. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romero C, Salinas JA, Saldivia S, Grandón P, Poole M, Salvador-Carulla L, et al. Comparative study of mental health services availability and use in Chile and Spain. Int J Integr Care. 2009 Jun;9(Suppl):e62 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson S, Kuhlmann R. The European Service Mapping Schedule (ESMS): development of an instrument for the description and classification of mental health services. Acta Psychiatr Scand; 2000;102(Suppl. 405):14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvador-Carulla L, Alvarez-Galvez J, Romero C, Gutiérrez-Colosía MR, Weber G, McDaid D, et al. Evaluation of an integrated system for classification, assessment and comparison of services for long-term care in Europe: the eDESDE-LTC study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013 Jun;13:218–218. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salvador-Carulla L, Romero C, Martínez A, Haro JM, Bustillo G, Ferreira A, et al. Assessment instruments: standardization of the European Service Mapping Schedule (ESMS) in Spain. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102(Suppl 405):24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salvador-Carulla L, Poole M, Gonzalez-Caballero JL, Romero C, Salinas JA, Lagares-Franco CM, et al. Development and usefulness of an instrument for the standard description and comparison of services for disabilities (DESDE) Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(Suppl. 432):19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvador-Carulla L, Amaddeo F, Gutiérrez-Colosía MR, Salazzari D, Gonzalez-Caballero JL, Montagni I, et al. Developing a tool for mapping adult mental health care provision in Europe: the REMAST research protocol and its contribution to better integrated care. Int J Integr Care. 2015;15:e042. doi: 10.5334/ijic.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montagni I, Salvador-Carulla L, Mcdaid D, Straßmayr C, Endel F, Näätänen P, et al. The REFINEMENT Glossary of Terms: An International Terminology for Mental Health Systems Assessment. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2018;45(2):342–351. doi: 10.1007/s10488-017-0826-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutierrez-Colosia MR, Salvador-Carulla L, Salinas-Perez JA, Garcia-Alonso CR, Cid J, Salazzari D, et al. Standard comparison of local mental health care systems in eight European countries. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S2045796017000415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas Chile National Population and Housing Census 2002 [Internet] 2002. [[cited 2018 Aug 18]]. Available from: https://redatam-ine.ine.cl/redbin/RpWebEngine.exe/Portal?BASE=CENSO_2002&lang=esp.

- 22.Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean - ECLAC Population and development division - CELADE [Internet] 2006. [[cited 2018 Aug 18]]. Available from: https://www.cepal.org/en/work-areas/population-and-development.

- 23.World Health Organization . Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salvador-Carulla L, García-Alonso CR, Gonzalez-Caballero JL, Garrido-Cumbrera M, González-Caballero JL, Garrido-Cumbrera M. Use of an operational model of community care to assess technical efficiency and benchmarking of small mental health areas in Spain. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2007;10(2):87–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blakely T, Woodward A. Ecological effects in multi-level studies. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54(5):367–374. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.5.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez A, Gillespie JA, Smith-Merry J, Feng X, Astell-Burt T, Maas C, et al. Integrated mental health atlas of the Western Sydney Local Health District: gaps and recommendations. Aust Heal Rev. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Chung Y, Salvador-Carulla L, Salinas-Pérez JA, Uriarte-Uriarte JJ, Iruin-Sanz A, García-Alonso CR. Use of the self-organising map network (SOMNet) as a decision support system for regional mental health planning. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018 Dec 25;16(1):35–35. doi: 10.1186/s12961-018-0308-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torres-Jiménez M, García-Alonso CR, Salvador-Carulla L, Fernández-Rodríguez V. Evaluation of system efficiency using the Monte Carlo DEA: The case of small health areas. Eur J Oper Res. 2015;242(2):525–535. [Google Scholar]