Abstract

Background

NTRK1, NTRK2 and NTRK3 gene fusions (NTRK gene fusions) occur in a range of adult cancers. Larotrectinib is a potent and highly selective ATP-competitive inhibitor of TRK kinases and has demonstrated activity in patients with tumours harbouring NTRK gene fusions.

Patients and methods

This multi-centre, phase I dose escalation study enrolled adults with metastatic solid tumours, regardless of NTRK gene fusion status. Key inclusion criteria included evaluable and/or measurable disease, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0–2, and adequate organ function. Larotrectinib was administered orally once or twice daily, on a continuous 28-day schedule, in increasing dose levels according to a standard 3 + 3 dose escalation scheme. The primary end point was the safety of larotrectinib, including dose-limiting toxicity.

Results

Seventy patients (8 with tumours with NTRK gene fusions; 62 with tumours without a documented NTRK gene fusion) were enrolled to 6 dose cohorts. There were four dose-limiting toxicities; none led to study drug discontinuation. The maximum tolerated dose was not reached. Larotrectinib-related adverse events were predominantly grade 1; none were grade 4 or 5. The most common grade 3 larotrectinib-related adverse event was anaemia [4 (6%) of 70 patients]. A dose of 100 mg twice daily was recommended for phase II studies based on tolerability and antitumour activity. In patients with evaluable TRK fusion cancer, the objective response rate by independent review was 100% (eight of the eight patients). Eight (12%) of the 67 assessable patients overall had an objective response by investigator assessment. Median duration of response was not reached. Larotrectinib had limited activity in tumours with NTRK mutations or amplifications. Pharmacokinetic analysis showed exposure was generally proportional to administered dose.

Conclusions

Larotrectinib was well tolerated, demonstrated activity in all patients with tumours harbouring NTRK gene fusions, and represents a new treatment option for such patients.

ClincalTrials.gov number

Keywords: larotrectinib, adult, phase I, NTRK gene fusion, TRK fusion cancer

Key Message

Oncogenic NTRK gene fusions encoding constitutively activated TRK tyrosine kinases occur across a wide range of tumours. Larotrectinib is a first-in-class potent and highly selective inhibitor of TRK kinases. In this first-in-human, phase I dose-escalation study, we showed that larotrectinib was well tolerated and provided consistent and durable antitumour activity in adults with TRK fusion cancer.

Introduction

Chromosomal rearrangements involving the NTRK1, NTRK2 and NTRK3 genes (NTRK gene fusions), which encode a family of receptor tyrosine kinases (TRKA/B/C) involved in neuronal development [1, 2], have been identified in a broad range of adult and paediatric tumour types [3]. Typically in such rearrangements, the 5′ region of an unrelated gene expressed in the tumour cell is joined in frame with the 3′ region of the NTRK gene, with the fusion transcript encoding a protein comprising the N terminus of the fusion partner joined to the C-terminus of the TRK protein, including the tyrosine kinase domain [4].

NTRK gene fusions occur at high frequency in several uncommon tumours, including infantile fibrosarcoma [5], congenital mesoblastic nephroma [6], paediatric papillary thyroid carcinoma [7], secretory breast carcinoma [8] and mammary analogue secretory carcinoma the salivary gland [9]. In addition, NTRK gene fusions have been identified at low frequency in a wide range of common adult cancers, including non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), breast cancer, colorectal cancer, soft tissue sarcoma, papillary thyroid cancer, melanoma, and glioblastoma [3, 10–13]. NTRK gene fusions may therefore represent one of the first tissue-agnostic and age-agnostic oncogenic drivers.

Larotrectinib is a potent and highly selective ATP-competitive inhibitor of TRKA, B and C receptor tyrosine kinases, with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 5–11 nM [14]. In vitro analyses have shown that tumour cell lines harbouring different NTRK gene fusions are sensitive to larotrectinib with IC50 values in the low nanomolar range.

Robust and durable responses to larotrectinib in paediatric and adult patients with TRK fusion cancer were recently reported [14]. In this first-in-human, phase I dose-escalation study, which contributed patients to this combined analysis, we report the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetic properties, and preliminary activity of larotrectinib in adult patients with advanced solid tumours. These data determined the recommended phase II larotrectinib dose currently under clinical investigation.

Methods

Study design and participants

This multi-centre, open-label, phase I, dose-escalation study enrolled patients at eight investigative sites in the United States. Adult patients, at least 18 years of age, with a locally advanced or metastatic solid tumour refractory to standard therapies were eligible. Other major inclusion criteria included an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–2, life expectancy of at least 3 months, and adequate organ function (absolute neutrophil count ≥1.5 ×109/l independent of growth factor support for at least 7 days before screening; platelet count ≥100×109/l independent of transfusion support for at least 7 days before screening; alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase <2.5 ×the upper limit of normal (ULN) or <5×ULN with documented liver metastases; total bilirubin <1.5×ULN, and an estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥30 ml/min according to the Cockroft-Gault formula). NTRK gene fusion status determination was not an eligibility criterion for enrolment. Key exclusion criteria included receipt of an investigational or anticancer therapy within 2 weeks, or major surgery within 4 weeks, before enrolment, clinically significant active cardiovascular disease or history of myocardial infarction within 6 months before enrolment, or active, uncontrolled systemic infection. Patients with primary central nervous system (CNS) tumours or metastasis who were neurologically stable, and did not require steroid management of CNS symptoms within the 2 weeks before study entry, were allowed to enrol.

The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centres. The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol and the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before any study specific procedures were conducted.

Procedures

Patients were enrolled to six cohorts according to a standard 3 + 3 dose escalation scheme. A safe starting dose of 50 mg once daily (QD) was determined based on data from animal toxicity studies. Larotrectinib was administered orally, as a QD or twice daily (b.i.d.) dose for continuous 28-day cycles. Treatment was continued until disease progression, the occurrence of unacceptable toxicity, or the withdrawal of patient consent. Dose escalation was to proceed through planned dose levels (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online), according to the occurrence of dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) in cycle 1, until the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was reached. Expansion of the cohort treated at the MTD, or at a dose level deemed by the sponsor to provide significant TRK inhibition was permitted to better characterise safety and efficacy in specific patient groups. Dose interruptions of up to 4 weeks to allow for recovery were specified for clinically significant adverse events. Upon recovery, patients could either continue at the assigned dose of larotrectinib or have the dose reduced. Patients who had drug-related toxicity requiring a recovery period longer than 4 weeks were to be withdrawn from study drug administration, unless there was compelling evidence of response and no alternative treatment.

Study assessments

Disease status was assessed by investigators according Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 [15], at baseline and then on day 1 of every other cycle. Patients with a history of CNS metastases were to additionally have head computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging carried out at each tumour assessment. Response in one patient has previously been described [16]. Blinded independent central review of imaging was subsequently carried out in patients with tumours harbouring NTRK gene fusions. Adverse events were monitored throughout the study and for 28 days after treatment and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03. Laboratory monitoring for toxicity and symptom directed neurological examinations for close monitoring of neurological toxicities were carried out weekly during cycle 1 and every 4 weeks thereafter.

Serial blood samples were collected for pharmacokinetic analyses. Plasma concentrations of larotrectinib were determined by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. The lower limit of quantification was 1 ng/ml. The appropriate noncompartmental pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from the plasma concentration–time data with Phoenix® WinNonlin® Version 6.4. AUC0–24 was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule for QD cohorts. AUC0–24 was estimated as two times AUC0–12 for b.i.d. cohorts, with trough concentrations imputed from the pre-dose concentration. Actual sample times were used in the calculations.

Tumour NTRK gene status was assessed locally in a clinical laboratory improvement amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratory, before enrolment, by next generation sequencing, and was not centrally tested. If patients did not have tumour available for such analyses (n = 18), they were considered not to have NTRK gene fusions.

Outcomes

The primary end point was the safety of oral larotrectinib, including the MTD and recommended dose for further clinical investigation. Secondary end points included pharmacokinetics, objective response and duration of response. A post hoc analysis of the objective response rate (ORR) in patients with TRK fusion cancer was carried out.

DLT was assessed during the dose escalation phase and was defined as any of the following treatment-emergent adverse events, if they occurred during the first cycle: grade 3 or 4 non-haematological toxicity, with the exception of fatigue, asthenia, nausea or other manageable constitutional symptom; grade 3 or 4 vomiting or diarrhoea persisting for more than 24 h; any toxicity, regardless of grade, resulting in discontinuation or dose reduction of larotrectinib; grade 4 thrombocytopenia or grade 3 thrombocytopenia with grade 1 or worse bleeding; grade 4 anaemia lasting more than 7 days; or grade 4 neutropenia lasting more than 7 days.

Statistical considerations

Safety and antitumour activity data were summarised descriptively. Adverse events were summarised using the standardised preferred term assigned by the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 18.1. The safety population comprised all patients who received one or more doses of larotrectinib. It was anticipated that enrolment of up to 60 patients might be required to define the MTD of larotrectinib, with the actual number dependent on the safety profile. A safety review committee considered safety and pharmacokinetic data and rendered dose-escalation decisions before each dose escalation. Antitumour activity was assessed in all enrolled patients; the ORR was calculated as the proportion of patients with measurable disease at baseline by RECIST v1.1 with a complete or partial response. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS (version 9.4).

Results

Between 1 May 2014 and 24 August 2017, 70 patients with a median age of 59.5 years (IQR 50–66, range 19–82 years) were enrolled to 6 cohorts. Four patients were enrolled to cohort 1 (50 mg QD), five to cohort 2 (100 mg QD), 43 to cohort 3 (100 mg b.i.d.), 4 to cohort 3a (200 mg QD), 7 to cohort 4 (150 mg b.i.d.), and 6 to cohort 5 (200 mg b.i.d.). The trial profile is summarised in supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Patient characteristics at baseline are summarised in Table 1. Patients were in general heavily pre-treated, with 44 (63%) of 70 having at least three prior systemic therapies. The data cut-off date for the present analysis was 19 February 2018.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline

| All patients (N = 70) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Median (IQR) | 59.5 (50–66) |

| Range | 19–82 |

| Median (IQR) for patients with tumour NTRK gene fusions (n=8) | 48 (36–57.5) |

| Median (IQR) for patients without tumour NTRK gene fusions (n=62) | 61 (52–67) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 35 (50) |

| Female | 35 (50) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 21 (30) |

| 1 | 47 (67) |

| 2 | 2 (3) |

| NTRK gene fusion (n=8) | |

| ETV6-NTRK3 | 6 (9) |

| LMNA-NTRK1 | 1 (1) |

| TPR-NTRK1 | 1 (1) |

| Prior anticancer treatments | |

| Systemic therapy | 68 (97) |

| Surgery | 61 (87) |

| Radiotherapy | 40 (57) |

| Number of prior systemic therapies | |

| 0 | 2 (3) |

| 1–2 | 24 (34) |

| ≥3 | 44 (63) |

Data are n (%), unless otherwise stated.

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

NTRK gene fusions were identified in the tumours of eight patients; six were ETV6-NTRK3 fusions, one an LMNA-NTRK1 fusion, and one a TPR-NTRK1 fusion (Table 1). Additional oncogenic driver mutations were not identified in any of the TRK fusion tumours. Patients with 23 unique cancer diagnoses were included in this dose escalation study, as summarised in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online, according to NTRK gene fusion status.

All enrolled patients were assessable for safety. During the dose-escalation phase, no DLTs occurred at the first two dose levels. A DLT (dizziness) was reported in one of the first six patients treated at 100 mg b.i.d. and none were seen at 200 mg QD. DLTs occurred in one of seven patients treated at 150 mg b.i.d. (alanine aminotransferase increased and aspartate aminotransferase increased) and one of six patients treated at 200 mg b.i.d. (dizziness). The MTD was consequently not reached, and the 100 mg b.i.d. dosing schedule was chosen as the recommended phase II dose based on its tolerability and the durability of response in patients with NTRK gene fusions; cohort 3 was subsequently expanded to further explore the safety and efficacy of larotrectinib.

The most commonly occurring treatment-emergent adverse events of any grade were fatigue, dizziness and anaemia (Table 2). Forty-two (60%) of 70 patients had grade 3 or worse treatment-emergent adverse events, with the most common being anaemia, fatigue and aspartate aminotransferase increased. Adverse events with an outcome of death were reported for five patients; all were related to disease progression. Most treatment-related adverse events were grade 1 or 2 (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online); 13 (19%) of the 70 patients experienced grade 3 treatment-related adverse events, the most common of which was anaemia [4 (6%) of 70 patients]. No patients had grade 4 or 5 treatment-related adverse events. Serious adverse events were reported in 32 (46%) of the 70 patients overall and in 17 (40%) of 43 patients in the 100 mg b.i.d. cohort. These were predominantly related to disease progression. Three (4%) of the 70 patients, none with an NTRK gene fusion, discontinued treatment due to larotrectinib-related adverse events (amylase increased, enterocutaneous fistula, lipase increased, and muscular weakness). Adverse events leading to dose interruption or modification were recorded in 30 (43%) of 70 patients; the most common were dizziness (5 patients; 7%) aspartate aminotransferase increased and pyrexia (3 patients; 4%). Utilising NTRK gene fusion status as a surrogate for safety related to long-term exposure, there was no meaningful difference in treatment-related adverse event profiles for patients with or without NTRK gene fusions (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent adverse events

| All patients, n = 70 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | |

| Fatigue | 28 (40) | 5 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 22 (31) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Anaemia | 12 (17) | 10 (14) | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 20 (29) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 17 (24) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnoea | 15 (21) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Cough | 16 (23) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 14 (20) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhoea | 13 (19) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 10 (14) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Oedema peripheral | 13 (19) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Myalgia | 11 (16) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 10 (14) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 11 (16) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 6 (9) | 4 (6) | 0 | 0 |

| Muscular weakness | 10 (14) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 7 (10) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 9 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Back pain | 8 (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 6 (9) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Blood alkaline phosphatase increased | 6 (9) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Gait disturbance | 6 (9) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | 6 (9) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Insomnia | 7 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Memory impairment | 7 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Paraesthesia | 7 (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data are n (%). Table shows adverse events occurring in ≥10% of patients at any grade.

Steady-state pharmacokinetic parameters for larotrectinib across the six dose escalation cohorts are summarised in supplementary Table S4 and Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. The rate and extent of exposure to larotrectinib following QD and b.i.d. administration at doses up to 200 mg increased with increasing dose. The estimates of exposure were generally proportional to the administered dose. Larotrectinib was rapidly eliminated from plasma and its half-life appeared to be independent of the administered dose. Following repeated administration of larotrectinib, minimal accumulation was evident in plasma, consistent with its short half-life.

Of the 70 patients enrolled, 67 patients were assessable for objective response, with measurable disease by RECIST 1.1 at enrolment; 3 patients without measurable disease were excluded from this assessment. The ORR among assessable patients as assessed by investigators was 12% (8 of the 67 patients); responses were seen in 7 of 8 patients with tumours harbouring NTRK gene fusions and in one patient with a tumour harbouring an NTRK1 gene amplification. The responding patient with the NTRK1 gene amplification had a single, small target lesion (11 mm) that shrank by 5 mm (45.5%) and a duration of response of 3.7 months. None of the patients with NTRK point mutations had an objective response, consistent with prior analyses suggesting that NTRK point mutations are generally not activating oncogenic events [17]. Following independent, central radiology review, eight (100%) of eight patients with tumours harbouring NTRK gene fusions were deemed to have had an objective response, including two with complete responses and six with partial responses (Table 3; supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 3.

Investigator and independent central assessments of response in patients with TRK fusion cancer

| Investigator assessment (n = 8) | Independent central assessment (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Objective response rate, % (95% CI) | 88% (47–100) | 100% (63–100) |

| Complete response, n (%) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) |

| Partial response, n (%) | 5 (63) | 6 (75) |

| Stable disease, n (%) | 1 (13) | 0 |

| Time to first response, median (min, max) | 1.8 months (1.0, 3.7) | 1.9 months (1.0, 14.5) |

| Duration of response, median (range), months | NR (14.7+ to 33.2+) | NR (8.2 to 33.1+) |

| Median follow-up, months | 26.9 | 27.0 |

NR, not reached.

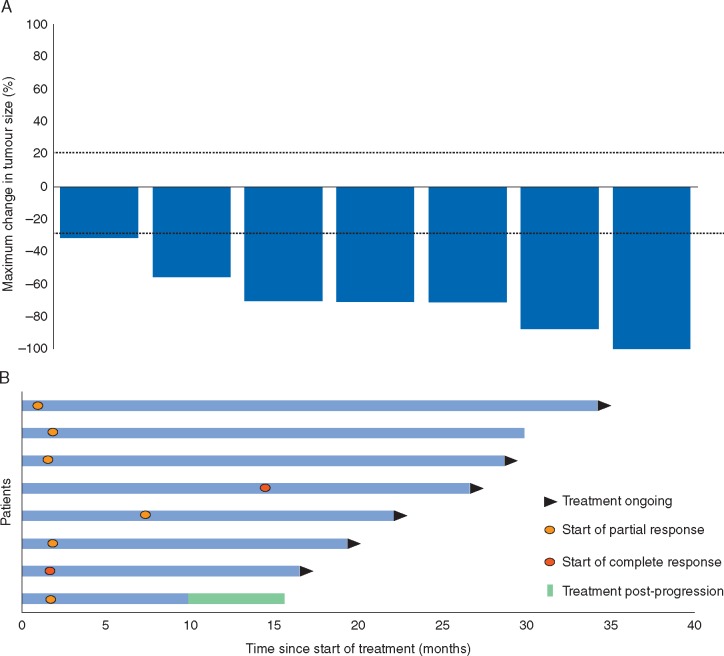

Reductions in tumour burden were observed in all patients with tumours harbouring an NTRK gene fusion. Figure 1A and supplementary Figure S4A, available at Annals of Oncology online show the best change in target lesion size in these patients according to independent assessment; Figure 1B and supplementary Figure S4B, available at Annals of Oncology online show the timing of response. Six of eight patients with TRK fusion cancer remained on treatment at 19 February 2018 cut-off. The median time on treatment of patients with TRK fusion cancer was 28.4 months (IQR 20.2–29.9) with a maximum of 35.2 months ongoing at the time of data analysis, compared with a median of 1.8 months (IQR 0.9–2.8) and a maximum of 27.0 months for patients whose tumours did not harbour an NTRK gene fusion. The median duration of follow up for patients with TRK fusion cancer on larotrectinib was 26.9 months; the median duration of response was not reached (supplementary Figure S5, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

Independent review committee assessment of response in patients with TRK fusion cancer. (A) Waterfall plot of maximum percentage change in tumour size of target lesions in patients with TRK fusion cancer. Outcome for one patient with a complete response is not shown as the independent review committee assessed this patient as having non-measurable disease at baseline. (B) Swimmer plot showing time on treatment and timing of objective response for patients with tumours harbouring NTRK gene fusions.

Following an initial response to treatment, a 29-year-old male with NSCLC and a 58-year-old male with a gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) progressed after developing acquired resistance mutations; solvent-front (TRKA G595R) and xDFG (TRKA G667S) mutations in the case of the patient with NSCLC, and a gatekeeper mutation (TRKC F617L) in the case of the patient with GIST.

Discussion

We found that in adults, larotrectinib was safe and well tolerated. Larotrectinib-related toxicities were most often grade 1 or 2, were reversible, and were easily managed. Since the MTD was not reached, 100 mg b.i.d. was set as the recommended phase II dose based on its tolerability and on the durability of response in patients with TRK fusion cancer. The 100 mg b.i.d. dosing regimen has since been investigated in a combined analysis of larotrectinib administered to 55 adult and paediatric patients with tumours harbouring NTRK gene fusions [14].

By independent radiology review, all eight patients with TRK fusion cancer were deemed to have had an objective response. One patient had punctate brain metastases at baseline that appeared to respond while on treatment, which suggests that larotrectinib can cross the blood–brain barrier. Indeed, the larotrectinib phase I paediatric study confirmed the presence of free drug within the CNS [18]. Six of eight patients are continuing on larotrectinib with a median time on treatment of 28.4 months, which is markedly longer than observed for patients whose tumours did not harbour NTRK gene fusions (1.8 months). These data demonstrate the significantly robust and prolonged durability of response to larotrectinib in patients with TRK fusion cancer, consistent with the findings of the paediatric phase I/II trial [18] and the ongoing phase II larotrectinib adult/adolescent basket trial (NCT02576431).

Our next generation sequencing data suggest that patients with TRK fusion cancer are unlikely to harbour other actionable alterations within their tumours. This argues for careful consideration when screening patients. In particular, it is crucial that the specific platform chosen for genetic screening is able to capture the entire spectrum of NTRK gene fusions.

The combined results of the current study and the paediatric larotrectinib trial [18] show that larotrectinib is effective against TRK fusion cancer, regardless of patient age. These studies also demonstrate the robust efficacy of larotrectinib against 17 unique TRK fusion tumour types [14, 18], regardless of NTRK gene and 5′ fusion partner.

In conclusion, larotrectinib was well tolerated and provided consistent and durable antitumour activity in adults with TRK fusion cancer, giving an ORR of 100% (eight of eight patients) by independent central assessment. This first-in-class, highly selective TRK inhibitor is the only one of its kind, to our knowledge, that is currently in clinical development simultaneously for both adult and paediatric cancers. Larotrectinib offers a potential new standard of care for patients with TRK fusion cancer, which is contingent on effective tissue-agnostic routine screening to detect tumours harbouring NTRK gene fusions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the participating patients and their families and contributing clinical staff across all sites. This study is supported and funded by Loxo Oncology Inc., Stamford, CT and Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany. Alturas Analytics Inc. (Moscow, Idaho) provided bioanalytical assessments. Medical writing services were provided by Jim Heighway, PhD of Cancer Communications and Consultancy Ltd, Knutsford, UK and were funded by Loxo Oncology Inc. and Bayer AG. Kathrina Marcelo-Lewis, PhD of the Department of Investigational Cancer Therapeutics at The University of Texas: MD Anderson Cancer Center also assisted in the writing of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Loxo Oncology Inc. (no grant number is applicable).

Disclosure

In relation to the work under consideration, DSH has received grant funding and non-financial support from Loxo Oncology. Outside of the submitted work, DSH has received grant funding from Bayer, Lilly, Genentech, Pfizer, Amgen, Mirati, Ignyta, Merck, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Adaptimmune, Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genmab, Infinity, Kite, Kyowa, Medimmune, Molecular Template, Novartis, Fate Therapeutics, MiRNA, Mologen, NCI-CTEP, Seattle Genetics, and Takeda, has received non-financial support for travel, accomodations, expenses from Mirna, and has consultancy/advisory roles with Bayer (Advisory Board), Baxter, Guidepoint global, Takeda, Janssen, Alpha Insights, Axiom, Adaptimmune, Genentech, GLG, Group H, Infinity, Merrimack, Medscape, Numab, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, and Trieza Therapeutics and an ownership interest in Molecular Match (Advisor), Presagia Inc (Advisor), and Oncoresponse (founder). TMB has consultancy/advisory roles with Ignyta, Guardant Health, Loxo Oncology, Pfizer, and Modern Therapeutics, his institution has received research funding from Daiichi Sanko, Medpacto Inc., Incyte, Mirati Therapeutics, MedImmune, Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Leap Therapeutics, MabVax, Stemline Therapeutics, Merck, Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Principa Biopharma, Genetech/Roche, Deciphera, Merrimack, Immunogen, Millennium, Ignyta, Calithera Biosciences Kolltan Pharmaceuticals, Peleton, Immunocore, Roche, Aileron Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, Moderna Therapeutics, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Astellas Pharma, Five Prime Therapeutics and Jacobio. In relation to the work under consideration, MSB’s institution has received grant funding from Loxo Oncology; outside of the submitted work MSB has received personal fees related to a consultancy role from Loxo Oncology and Bayer Healthcare. In relation to the work under consideration, AFF has received grant funding, personal fees and non-financial support from Bayer and Loxo Oncology. Outside of the submitted work, AFF has received grant funding, personal fees and non-financial support from Abbvie, Pharmamar, and Stemcentrx, grant funding from Ignyta, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck and Genentech, personal fees and non-financial support from Merrimack, and personal fees from Takeda and Foundation Medicine. Outside of the submitted work, MT has a consultancy role and has served on speakers bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Eisai Inc and has consultancy/advisory roles with Blueprint Medicines, Loxo Oncology, Novartis, Array Biopharma, Trillium and Arqule. In relation to the work under consideration, ATS has received research funding for the study and outside of the submitted work, has received personal fees related to consultancy/advisory roles from Ignyta, TP Therapeutics, Pfizer, Novartis, Takeda, Ariad, Roche/Genentech, Blueprint Medicines, KSQ Therapeutics, Foundation Medicine, Guardant, Natera and Loxo Oncology. SS and SC are consultants for Loxo Oncology. BBT and KE are employees of and own stock in Loxo Oncology. MCC is an employee of and owns stock in Loxo Oncology, holds a patent 62/318 041 issued to Loxo Oncology, and owns stock in Bayer AG. In relation to the work under consideration, RCD has received grant funding and personal fees from Loxo Oncology and personal fees from Bayer and outside of the submitted work, has received grant funding and personal fees from Ignyta and personal fees related to advisory roles and or travel expenses from AstraZeneca, Ariad, Takeda, Spectrum and Guardant Health. RCD has a patent PCT/US13/57495 with royalties paid by Abbott Molecular, and a patent PCT/US2016/058951 pending. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Nakagawara A. Trk receptor tyrosine kinases: a bridge between cancer and neural development. Cancer Lett 2001; 169(2): 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rubin JB, Segal RA.. Growth, survival and migration: the Trk to cancer. Cancer Treat Res 2003; 115: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amatu A, Sartore-Bianchi A, Siena S.. NTRK gene fusions as novel targets of cancer therapy across multiple tumour types. ESMO Open 2016; 1(2): e000023.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vaishnavi A, Le AT, Doebele RC.. TRKing down an old oncogene in a new era of targeted therapy. Cancer Discov 2015; 5(1): 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bourgeois JM, Knezevich SR, Mathers JA, Sorensen PH.. Molecular detection of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion differentiates congenital fibrosarcoma from other childhood spindle cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24(7): 937–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Knezevich SR, Garnett MJ, Pysher TJ. et al. ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusions and trisomy 11 establish a histogenetic link between mesoblastic nephroma and congenital fibrosarcoma. Cancer Res 1998; 58(22): 5046–5048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prasad ML, Vyas M, Horne MJ. et al. NTRK fusion oncogenes in pediatric papillary thyroid carcinoma in northeast United States. Cancer 2016; 122(7): 1097–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tognon C, Knezevich SR, Huntsman D. et al. Expression of the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion as a primary event in human secretory breast carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2002; 2(5): 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Skalova A, Vanecek T, Sima R. et al. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34: 599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hechtman JF, Benayed R, Hyman DM. et al. Pan-Trk immunohistochemistry is an efficient and reliable screen for the detection of NTRK fusions. Am J Surg Pathol 2017; 41(11): 1547–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lezcano C, Shoushtari AN, Ariyan C. et al. Primary and metastatic melanoma with NTRK fusions. Am J Surg Pathol 2018; 42(8): 1052–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ross J, Chung J, Elvin J. et al. Abstract P2-09-15: NTRK fusions in breast cancer: clinical, pathologic and genomic findings. Cancer Res 2018; 78 (Suppl 4): abstract P2-09-15. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vaishnavi A, Capelletti M, Le AT. et al. Oncogenic and drug-sensitive NTRK1 rearrangements in lung cancer. Nat Med 2013; 19(11): 1469–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S. et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion–positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(8): 731–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45(2): 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Doebele RC, Davis LE, Vaishnavi A. et al. An oncogenic NTRK fusion in a patient with soft-tissue sarcoma with response to the tropomyosin-related kinase inhibitor LOXO-101. Cancer Discov 2015; 5(10): 1049–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nanda N, Fennell T, Low J.. Identification of tropomyosin kinase receptor (TRK) mutations in cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(Suppl 15): abstract 1553. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laetsch TW, DuBois SG, Mascarenhas L. et al. Larotrectinib for paediatric solid tumours harbouring NTRK gene fusions: phase 1 results from a multicentre, open-label, phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19(5): 705–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.