Abstract

Fewer than 60,000 males—inclusive of all sexual identities—were prescribed HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) by mid-2017 in the United States. Efforts to increase PrEP uptake among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBM), in particular, are ongoing in research and practice settings, but few tools exist to support interventions. We aimed to develop and validate tools to support motivational interviewing interventions for PrEP. In 2017, a national sample of HIV-negative GBM of relatively high socioeconomic status (n = 786) was asked about sexual behaviors that encompass Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for PrEP use, a 35-item decisional-balance scale (i.e., PrEP-DB) assessing benefits and consequences of PrEP use, and questions assessing location on the motivational PrEP cascade and derivative—the PrEP contemplation ladder. Principal axis factoring with oblique promax rotation was used for PrEP-DB construct identification and item reduction. The final 20-item PrEP-DB performed well; eigenvalues indicating a 4-factor solution provided an adequate fit to the data. Factors included the following: health benefits (α = 0.91), health consequences (α = 0.82), social benefits (α = 0.72), and social consequences (α = 0.86). Ladder scores increased across the cascade (ρ = 0.89, p < 0.001), and health benefits (β = 0.50, p < 0.001) and health consequences (β = −0.37, p < 0.001) were more strongly associated with ladder location than social benefits (β = 0.05, p > 0.05) and social consequences (β = −0.05, p > 0.05) in the fully adjusted regression model. The PrEP-DB demonstrated good reliability and predictive validity, and the ladder had strong construct validity with the motivational PrEP cascade. PrEP uptake and persistence interventions and additional empirical work could benefit from the utility of these measures.

Keywords: HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis, motivational interviewing, men who have sex with men

Introduction

Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBM) continue to be disproportionately affected by the HIV epidemic in the United States (US).1 Younger GBM (≤29 years old) and GBM of color—particularly Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino GBM—had the highest rates of HIV incidence in 20161; these disparities persist despite biomedical advances in HIV treatment as prevention2 and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).3–8 Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA),9 PrEP offers a promising opportunity for primary HIV prevention among GBM. Demonstration projects have shown that PrEP provides a high level of prevention against HIV seroconversion in real-world settings,10–14 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends PrEP for HIV-negative GBM who have a sexual partner living with HIV or are in a nonmonogamous relationship with an HIV-negative male partner and report any condomless anal sex or bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the past 6 months.15,16

PrEP uptake remains modest among GBM in the United States. After release of iPrEx study results in 2010 and USFDA approval in 2012,5,9 PrEP uptake steadily increased overall from 2013 to 2015.17 In 2015, PrEP uptake among those identified as candidates for PrEP was estimated to be 9.1% in a nationwide sample of HIV-negative GBM targeted based on age, race/ethnicity, and geography of same-sex households in the United States.18 Among young (i.e., 16–29 years old) GBM, PrEP uptake was reported as low as 4.2% in Atlanta and as high as 12.2% in Chicago and Houston in sampling periods between 2014 and 2016,19,20 although PrEP was only approved for use by those younger than 18 years in May, 2018.21 Overall, fewer than 60,000 males were prescribed PrEP during the second quarter of 2017, defined by PrEP prescription for 1 day or greater during the 3-month period,22 although data on the sexual behavior and sexual identity of these men are unknown; thus, this number likely includes some who are not GBM. Despite a conservative estimate of 492,000 GBM meeting CDC criteria for PrEP use,23 the number of GBM eligible for PrEP could be greater than 60%18 of the nearly 4.3–5.4 million GBM in the United States.24 Interventions to support PrEP uptake among GBM at risk for HIV are warranted to further reduce HIV incidence in the United States. In addition, PrEP adherence support is important because of the mixed adherence findings in clinical trials3–8 and the association between adherence and PrEP efficacy,10 but early evidence from this study's sample and another suggests that GBM are maintaining adequate adherence to support HIV prevention18 or appropriately adjusting their next-day dosing or subsequent behavior.25

One mechanism to increase PrEP uptake among GBM is through motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing is an evidence-based strategy for enhancing internal motivation to engage in behavior change,26 which has been used successfully to increase many HIV prevention behaviors (e.g., increased condom use),27–38 by tailoring interventions to individuals' current readiness to adopt the behavior.37,38 A decisional balance is a technique associated with motivational interviewing that is used to weigh the pros and cons of behavioral change, which can provide an empirical assessment of cognitive and motivational aspects of decision making.39 The information-motivation-behavioral skills model40 posits the importance of motivation on behavioral skills and health behavior, which has been validated in prior HIV prevention research.41–44 As such, a decisional balance of the pros and cons of PrEP use can be used to measure motivation within this theoretical framework. However, prior research has not identified specific domains of motivational perceptions of PrEP use, which could further inform intervention development, better target specific at-risk groups by assessing differences by demographic characteristics, and measure intermediate outcomes to intervention effects.

The motivational PrEP cascade was developed based off the transtheoretical model45 to stage individuals into five distinct steps toward PrEP uptake and maintenance of daily dosing and regular testing for HIV and other STIs (i.e., persistence).18 These five stages of the PrEP cascade include the following: (1) PrEP precontemplation, (2) PrEP contemplation, (3) PrEParation, (4) PrEP action and initiation, and (5) PrEP maintenance. Each stage has two components with sometimes multiple items of assessment, creating a lengthy questionnaire, limiting utility in clinical practice settings and within brief survey research. As such, shortened measures are needed to assess patients' stage of change toward PrEP uptake and persistence. A brief assessment tool could be used to guide staging patients within the cascade for PrEP interventions more efficiently, while also reducing participant burden in survey research.

In this article, we evaluated two brief intervention and assessment tools using data collected in mid-2017 from participants in the One Thousand Strong cohort study. We aimed to develop and validate a PrEP decisional balance (i.e., PrEP-DB) and a brief PrEP cascade measure (i.e., the PrEP contemplation ladder) to support interventions using the motivational PrEP cascade, which was initially conceptualized by members of the authorship team with data from an earlier time point of this cohort study.18 We hypothesized correspondence between the brief PrEP contemplation ladder and the longer motivational PrEP cascade questionnaire, and we hypothesized PrEP-DB scores to increase and decrease across the PrEP cascade and ladder for constructs aligned with pros and cons of PrEP, respectively.

Methods

We used data from participants enrolled in the One Thousand Strong study, a national cohort of HIV-negative (confirmed with testing at baseline) GBM in the United States.46,47 Briefly, 1071 HIV-negative GBM were recruited to reflect census data on same-sex households in the United States based on age, race/ethnicity, and US geography in 2014 using a marketing firm (i.e., Community Marketing and Insights), which has a panel of over 22,000 GBM throughout the United States. Using the same aforementioned recruitment strategy, we enrolled another 133 non-White GBM (of n = 222, who were screened eligible) between November 2016 and February 2017. Expansion of the cohort at the 24-month assessment wave (baseline for new enrollees) was done to increase the diversity of non-White participants, given their disproportionate burden of the HIV epidemic in the United States.1 Enrollment procedures for new GBM in the sample included eligibility screening, providing informed consent, completing the computer-assisted survey interview, and participating in the at-home HIV and STI testing procedures [i.e., OraQuick In-Home HIV Test (with results submitted by a photo of the test paddle) and self-sampling of urine and rectal swab for mailing to a laboratory for analysis] with a confirmed rapid HIV-negative result (n = 133); these procedures were the same for the original cohort. Participants were sent an optional survey in 2017, which included measures relevant to this analysis. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the City University of New York.

Of the 1204 GBM enrolled in the cohort, 825 completed the optional survey between April 2017 and July 2017. An additional 38 men were excluded from analyses because of a technological error that resulted in partial survey completion, and another participant was excluded because he self-reported testing HIV positive in the interim since the last assessment wave. This resulted in a final analytic sample of 786 HIV-negative GBM.

Measures

Demographics

We asked participants to report their age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, employment status, and income.

PrEP-DB scale

Thirty-five items for the PrEP-DB were identified based on previously reported barriers and facilitators in extant literature.48–65 Men were asked to respond to 17 barriers and 18 facilitators to PrEP use with the following statement: “How important is each statement to you when making decisions to use or not use PrEP?” The order of item presentation was randomized for each participant with five-point response categories ranging from not at all important to extremely important. An example item of the scale is, “Taking PrEP would make me feel more in control of my sexual health.”

Motivational PrEP cascade

The motivational PrEP cascade is a staging process with five main stages based on the transtheoretical model;45 coding of the motivational PrEP cascade developed by our research team with data from an earlier survey follow-up is described elsewhere.18 Briefly, individuals were coded as meeting objective identification as a candidate for PrEP if they were HIV negative, sexually active with men, and met modified (i.e., 3-month sexual behavior recall compared to 6-month recall) CDC guidelines15,16 as candidates for PrEP. Men were coded as being in PrEP pre-contemplation if they were objectively identified, but unwilling to take PrEP, or did not perceive themselves to be a good candidate for PrEP. PrEP contemplation was assessed by willingness to take PrEP and self-identification as a candidate for PrEP. In a change from the original question of the motivational PrEP cascade (i.e., “Suppose that PrEP is at least 90% effective in preventing HIV when taken daily, how likely would you be to take PrEP if it were available for free?”), PrEP willingness was assessed by the following question: “How likely would you be to take PrEP if it were available for free?” Response categories ranged from I would definitely take it to I would definitely not take it, and men who responded that they would probably or definitely take PrEP were coded as willing.18,65–67 Men were coded as being in PrEParation if they reported having a potential PrEP provider and were intending to take PrEP. Men were coded as in the PrEP action and initiation stage if they reported having ever spoken to a medical provider about PrEP in the past 6 months and are currently prescribed PrEP. Finally, men were considered to be in PrEP maintenance and adherence if they were adequately adherent to their daily PrEP dosing schedule and consistent with PrEP maintenance activities, returning for quarterly HIV/STI testing. To assess adequate PrEP adherence consistent with the current state of science regarding sustained HIV protection even with several missed doses,68 men were asked the following question with a yes or no response: “In the last month (30 days), has there been a time when you did not take your PrEP for 4 or more days in a row?”

PrEP contemplation ladder

Based on the burdensome questionnaire and extensive data analysis syntax required for coding the motivational PrEP cascade, we sought to develop a brief assessment tool to improve utility in a clinical practice setting and reduce participant burden in study questionnaires. Men were provided the following statement: “Each statement below represents where people are in terms of their thinking about using PrEP to prevent HIV. Lower numbers indicate that you do not use PrEP to prevent HIV and are not really thinking of ever starting to use PrEP. Higher numbers indicate that you are using PrEP daily and returning for provider checkups and HIV/STI testing every 3 months, as recommended. Please check the number that best corresponds to your thinking about PrEP today.” Ten responses were presented ranging 1 (I will never need PrEP and have no interest in ever starting it) to 10 (I have been taking PrEP every day and am committed to HIV/STI testing and provider checkups every 3 months, as recommended).

Data analysis

Principal axis factoring with oblique promax rotation was used to identify dimensionality of the 35-item PrEP-DB. Construct item reduction was then conducted by removing items with a predetermined factor loading below 0.60. Spearman's rho was used to assess the nonparametric correlation of PrEP-DB construct scores across cascade stages, and we also reported one-way analysis of variance findings for comparison. Spearman's rho was similarly used to compare the PrEP cascade based on the full battery with the 10 steps of the PrEP ladder. We then tested for differences in PrEP-DB factors by race/ethnicity using analysis of variance with conservative, Scheffe-adjusted post hoc comparisons and significance threshold of α = 0.05. Finally, we examined associations of PrEP-DB constructs together on the PrEP cascade and ladder separately using fully adjusted multi-variable linear regression.

Results

Participants and stage of motivational PrEP cascade

Of the 786 HIV-negative GBM who completed the optional survey in mid-2017, most were white (65.4%) and had a bachelor's degree or higher education (62.1%; Table 1). Most (68.2%) were employed full time, roughly half (51.3%) made $50,000 or more in annual income, and the average age was 43.4 years (range, 20–82 years). The majority (69.3%) of men in the sample were objectively identified as candidates for PrEP using modified CDC guidelines; however, only two-thirds (64.6%) of men objectively identified considered themselves as candidates for PrEP, representing a notable drop-off early in the motivational PrEP cascade. Of the 545 men eligible for PrEP, 41.5% (n = 226) were in PrEP precontemplation, 21.1% (n = 115) in PrEP contemplation, 11.0% (n = 60) in PrEParation, 6.4% (n = 35) in PrEP action and initiation, and 20.0% (n = 109) in PrEP maintenance and adherence. Of those who had a potential PrEP provider and intending to take PrEP (i.e., all men who met PrEParation or a higher stage), 70.6% (n = 144) had spoken to a medical provider and were currently prescribed PrEP, representing 18.3% of the overall sample, and 26.4% of men objectively identified as candidates for PrEP. Among the men currently prescribed PrEP (i.e., all men in PrEP action and initiation and PrEP maintenance and adherence; n = 144), 75.7% (n = 109) of the men were considered to be in PrEP maintenance and adherence. Adherence to once-daily PrEP was high among users; 93.1% (n = 134) had indications of adequate adherence by not missing 4 days of PrEP dosing in a row within the past 30 days. Nonetheless, 21.1% (n = 29) of men currently prescribed PrEP were not returning for quarterly HIV/STI testing appointments as recommended.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Gay and Bisexual Men (n = 786)

| Categorical variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 80 | 10.2 |

| Latino | 121 | 15.4 |

| White | 514 | 65.4 |

| Other/multi-racial | 71 | 9.0 |

| Education | ||

| Less than Bachelor's degree | 298 | 37.9 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 488 | 62.1 |

| Employment | ||

| Unemployed | 137 | 17.4 |

| Part-time employment | 113 | 14.4 |

| Full-time employment | 536 | 68.2 |

| Income | ||

| Less than $50k per year | 383 | 48.7 |

| $50k or more per year | 403 | 51.3 |

| Continuous variables | M | SD |

| Age (range, 20–82) | 43.4 | 13.6 |

Factor structure and reliability of the PrEP-DB

We identified a four-factor structure using the scree plot and factor eigenvalues. Eigenvalues were 10.28, 4.75, 2.19, 1.47, 1.06, and 1.01 for factors 1–6, respectively. The PrEP-DB scale was reduced to 20 items after removal of items with a predetermined factor loading below 0.60. The factor loadings of the PrEP-DB scale items are presented in Table 2. All subscales had acceptable reliability measured by Cronbach's alpha with no cross-loading between final factors present. The four subscales of the PrEP-DB were as follows: (1) health benefits (α = 0.91), (2) health consequences (α = 0.82), (3) social benefits (α = 0.72), and (4) social consequences (α = 0.86).

Table 2.

Factor Loadings of Barriers and Facilitators to Using Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Among Gay and Bisexual Men (n = 786)

| Factor loadingsa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health benefits | Social benefits | Health consequences | Social consequences | |

| Scale items retainedb,c | ||||

| Taking PrEP would make me feel more in control of my sexual health | 0.83 | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP would be a reason to get tested for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections more often | 0.67 | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP would be an extra layer of protection against HIV | 0.77 | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP seems like the responsible thing to do | 0.87 | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP seems like the “normal” thing for an HIV-negative guy to do | 0.64 | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP would help me protect my sexual partners from HIV | 0.74 | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP makes testing for STIs part of routine health care (as opposed to only getting screened when something is wrong) | 0.63 | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP would help me discuss my sexual health with my medical provider | 0.61 | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP would make me feel like I am doing my part to control the HIV epidemic | 0.83 | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP would mean I have more freedom to decide when to use and not use condoms | — | 0.69 | — | — |

| Taking PrEP would help me feel less inhibited and “let go” | — | 0.70 | — | — |

| Taking PrEP means I no longer have to worry about asking my partner's HIV status | — | 0.62 | — | — |

| I may experience some side effects from PrEP | — | — | 0.77 | — |

| I may experience long-term health consequences from PrEP | — | — | 0.83 | — |

| I may develop resistance to certain HIV medications if I were to become HIV+ while taking PrEP | — | — | 0.68 | — |

| PrEP might not provide complete protection against HIV | — | — | 0.69 | — |

| People may think I'm HIV+ if they see that I'm taking HIV medications as PrEP | — | — | — | 0.84 |

| People may stereotype me if they know I'm on PrEP | — | — | — | 0.82 |

| Doctors may think I'm HIV+ if I tell them I'm taking PrEP | — | — | — | 0.86 |

| I don't want my medical record to show that I've been on PrEP | — | — | — | 0.61 |

| Scale items removedb,c | ||||

| Taking PrEP would help me to worry less about HIV | — | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP would make me feel more sexually confident | — | — | — | — |

| I would enjoy sex more if I were on PrEP | — | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP would make me less worried about having sex with men who are HIV+ | — | — | — | — |

| Telling guys I'm on PrEP would mean not having to discuss HIV any further | — | — | — | — |

| Taking PrEP would make me feel like part of a community | — | — | — | — |

| I would have to go to the doctor every 3 months to take PrEP | — | — | — | — |

| I may have to discuss my sex life with a doctor to get PrEP | — | — | — | — |

| I would have to remember to take a pill every day if I'm on PrEP | — | — | — | — |

| I'd still have to use condoms if I took PrEP | — | — | — | — |

| PrEP doesn't prevent other sexually transmitted infections | — | — | — | — |

| I don't know how to get the costs of PrEP covered | — | — | — | — |

| PrEP would feel like too much of a commitment | — | — | — | — |

| I'm worried I might stop using condoms if I were on PrEP | — | — | — | — |

| I don't think my behavior is risky enough to need PrEP | — | — | — | — |

| Percentage of total variance | 29.36% | 4.21% | 13.58% | 6.26% |

Pattern matrix loadings using principal axis factoring.

Response categories: “not at all important” to “extremely important”.

Scale items with factor loadings less than 0.600 are not reported for interpretation ease.

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Predictive validity of the PrEP-DB

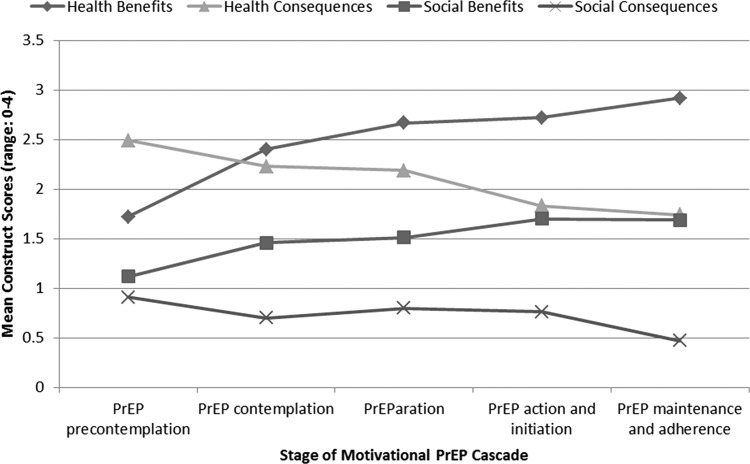

The PrEP-DB performed well in this sample (Table 3). Men at higher stages of the PrEP cascade had increasing scores (ρ = 0.49, p < 0.001) on the health benefit subscale; men currently taking PrEP had the highest perceptions of the health benefits associated with PrEP use. Similarly, scores on the social benefit subscale generally increased (ρ = 0.23, p < 0.001) across stages of the cascade. On the contrary and as expected, men at earlier locations of the motivational PrEP cascade reported greater concerns about the health and social consequences associated with PrEP use. Concerns about health consequences were highest among men in precontemplation and lowest among those in maintenance and adherence with decreasing scores (ρ = −0.27, p < 0.001) reported at each stage of the cascade. Concerns about social consequences were also highest among men in precontemplation and lowest among those in maintenance and adherence. While the correlation of social consequences across the cascade was significant (ρ = −0.13, p < 0.01), men in PrEP action and initiation had higher scores on the social consequences subscale of the PrEP-DB compared to those in contemplation and preparation; however, these differences were small. Health benefits had the highest correlation with the motivational PrEP cascade, followed by health consequences, social benefits, and social consequences. Illustrated in Fig. 1 is a visual representation of PrEP-DB construct scores across the five stages of the motivational PrEP cascade, which shows the expected pattern of progressive increases in perceived benefits and decreases in perceived consequences as the stage of change increases. PrEP-DB factor scores differed by race/ethnicity for health benefits and consequences, but no differences by race/ethnicity were observed for social benefits and consequences (Table 4). Specifically, individuals who did not identify as white reported higher average response scores on health benefits and consequences compared to white GBM. Black and Latino GBM had higher response means for health benefits compared to white GBM individually, but were not significantly different from each other. For health consequences, Latino and other/multi-racial GBM had higher response means compared to white GBM individually, but non-white GBM did not differ between race/ethnicity categories.

Table 3.

Stage of Motivational PrEP Cascade and Decisional Balance Construct Scores Among Gay and Bisexual Men Objectively Identified as Candidates for PrEP (n = 545)

| Health benefits, (range, 0–4; α = 0.91) | Social benefits, (range, 0–4; α = 0.72) | Health consequences, (range, 0–4; α = 0.82) | Social consequences, (range, 0–4; α = 0.86) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Stage 1: PrEP precontemplation | 226 | 41.5 | 1.72 (0.98) | 1.12 (0.97) | 2.49 (1.06) | 0.91 (1.08) |

| Stage 2: PrEP contemplation | 115 | 21.1 | 2.40 (0.87) | 1.46 (1.00) | 2.23 (1.02) | 0.70 (0.93) |

| Stage 3: PrEParation | 60 | 11.0 | 2.67 (0.73) | 1.51 (1.02) | 2.19 (1.06) | 0.80 (0.90) |

| Stage 4: PrEP action and initiation | 35 | 6.4 | 2.72 (0.95) | 1.70 (1.07) | 1.83 (1.10) | 0.76 (1.01) |

| Stage 5: PrEP maintenance and adherence | 109 | 20.0 | 2.92 (0.65) | 1.69 (1.02) | 1.74 (0.94) | 0.47 (0.71) |

| One-way analysis of variance | F(4, 540) = 44.03*** | F(4, 540) = 7.61*** | F(4, 540) = 10.90*** | F(4, 540) = 4.11** | ||

| Spearman's rho correlation | 0.49*** | 0.23*** | −0.27*** | −0.13** |

*p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

FIG. 1.

Stage of motivational PrEP cascade and decisional balance construct scores among gay and bisexual men objectively identified as candidates for PrEP (n = 545). PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Table 4.

PrEP Decisional Balance Construct Scores by Race/Ethnicity Among Gay and Bisexual Men Objectively Identified as Candidates for PrEP (n = 545)

| Health benefits (range, 0–4; α = 0.91) | Social benefits (range, 0–4; α = 0.72) | Health consequences (range, 0–4; α = 0.82) | Social consequences (range, 0–4; α = 0.86) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| Race/ethnicity | F(3, 541) = 5.54*** | F(3, 541) = 1.88 | F(3, 541) = 5.01** | F(3, 541) = 0.78 |

| Black | 2.56 (0.99)a† | 1.44 (1.17) | 2.28 (1.11)ab | 0.78 (1.11) |

| Latino | 2.45 (1.00)a | 1.39 (0.98) | 2.46 (1.06)a | 0.88 (1.06) |

| White | 2.14 (0.98)b | 1.33 (0.98) | 2.08 (1.05)b | 0.71 (0.92) |

| Other/multi-racial | 2.38 (1.02)ab | 1.68 (1.13) | 2.55 (1.06)a | 0.84 (0.93) |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Superscripts denote post hoc comparison tests using Scheffe multiple comparisons adjustment. For health benefits, black and Latino are not significantly (α = 0.05) different from each other, but black and Latino are significantly different than white individually, and other/multi-racial are not significantly different than any other category.

Construct validity of the PrEP contemplation ladder

The PrEP contemplation ladder—a single-item question (Table 5)—also performed well in comparison to the motivational PrEP cascade questionnaire. PrEP ladder scores increased across the PrEP cascade (ρ = 0.89, p < 0.001), and the multi-variable findings were congruent between the PrEP cascade and ladder discussed next.

Table 5.

The PrEP Contemplation Ladder by Stage of Change Among Gay and Bisexual Men Objectively Identified as Candidates for PrEP (n = 545)

| Motivational PrEP cascade stage of change | PrEP contemplation ladder items | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| PrEP Precontemplation | 1. I will never need PrEP and have no interest in ever starting it. | 27 | 5.0 |

| PrEP Precontemplation | 2. I am not willing to take PrEP and I currently have no plans start it. | 44 | 8.1 |

| PrEP contemplation | 3. I am willing to take PrEP but I don't think I'm a good candidate for it and have no plans to start it. | 101 | 18.5 |

| PrEP contemplation | 4. I am willing to take PrEP and think I'm a good candidate for it, but I currently have no plans to start it. | 133 | 24.4 |

| PrEParation | 5. I definitely plan to start taking PrEP, but I'm not yet ready to take any steps to get started. | 50 | 9.2 |

| PrEParation | 6. I definitely plan to start taking PrEP and I've talked to a doctor about getting started, but don't yet have a prescription. | 37 | 6.8 |

| PrEP action and initiation | 7. I've gotten a prescription for PrEP, but I'm having trouble getting it filled. | 9 | 1.7 |

| PrEP action and initiation | 8. I am on PrEP, but struggle to take it daily and am not sure I can see my provider for HIV/STI testing every 3 months, as recommended. | 1 | 0.2 |

| PrEP action and initiation | 9. I am on PrEP and take it nearly every day, but it's difficult to get to my provider for HIV/STI testing every 3 months, as recommended. | 13 | 2.4 |

| PrEP maintenance and adherence | 10. I have been taking PrEP every day and am committed to HIV/STI testing and provider checkups every 3 months, as recommended. | 131 | 23.9 |

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Due to similarity in findings of the fully adjusted multi-variable regression models of the motivational PrEP cascade and PrEP contemplation ladder (Table 6), we discuss findings, in this study, of the contemplation ladder only. Younger men were higher on the PrEP ladder as ladder scores decreased across age (β = −0.22, p < 0.001). Black men were significantly lower on the PrEP ladder compared to white men (β = −0.09, p < 0.01), but no other race/ethnicity differences were observed compared to white men. Men with more than $50,000 annual income were also higher on the PrEP ladder compared to those with less income (β = 0.57, p < 0.05); no significant differences were found based on educational attainment or employment status.

Table 6.

Results of the Fully Adjusted Linear Regression Model Predicting Location on the Motivational PrEP Cascade and PrEP Cascade Ladder Among Gay and Bisexual Men (n = 545)

| Motivational PrEP cascade | PrEP contemplation ladder | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β |

| Age | −0.03 (0.00)*** | −0.24 | −0.05 (0.01)*** | −0.22 |

| Race/ethnicity (Ref: white) | ||||

| Black | −0.38 (0.16)* | −0.08 | −0.84 (0.31)** | −0.09 |

| Latino | −0.15 (0.15) | −0.03 | −0.26 (0.29) | −0.03 |

| Other/multi-racial | 0.07 (0.19) | 0.01 | 0.14 (0.36) | 0.01 |

| Education (Ref: less than Bachelor's degree) | ||||

| Bachelor's degree or more | 0.15 (0.11) | 0.05 | 0.32 (0.21) | 0.05 |

| Employment (Ref: unemployed) | ||||

| Part-time employment | −0.02 (0.19) | −0.00 | −0.11 (0.36) | −0.01 |

| Full-time employment | 0.06 (0.15) | 0.02 | 0.21 (0.28) | 0.03 |

| Income (Ref: less than $50k per year) | ||||

| $50k or more per year | 0.37 (0.12)** | 0.12 | 0.56 (0.23)* | 0.09 |

| Barriers and facilitators | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β |

| Health benefits | 0.77 (0.06)*** | 0.49 | 1.49 (0.11)*** | 0.50 |

| Social benefits | 0.06 (0.06) | 0.04 | 0.16 (0.11) | 0.05 |

| Health consequences | −0.53 (0.05)*** | −0.36 | −1.03 (0.10)*** | −0.37 |

| Social consequences | −0.08 (0.06) | −0.05 | −0.15 (0.11) | −0.05 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Regarding the PrEP-DB constructs, health benefits were the strongest correlate with PrEP ladder location in the fully adjusted model. Higher perceived importance of the health benefits of PrEP was associated with being higher on the PrEP ladder (β = 0.50, p < 0.001). Health consequences were the next strongest correlate with score on the PrEP ladder, with greater concerns about the health consequences of PrEP associated with a lower selected position on the PrEP ladder (β = −0.37, p < 0.001). The effects of social benefits and consequences diminished compared to the bivariate findings after accounting for health benefits and consequences in the multi-variable model. Social benefits and consequences were not significantly associated with location on the PrEP ladder.

Discussion

By mid-2017, 26.4% of GBM objectively identified as candidates for PrEP were prescribed once-daily PrEP in our US nationwide sample, with three-quarters of those maintaining adequate adherence and regular HIV/STI testing. This is an increase from 9.1% PrEP uptake among GBM objectively identified as candidates for PrEP in 2015,18 and this finding highlights the increase in PrEP uptake nationwide among GBM in the United States reported by others.22 Nonetheless, fewer than 60% of men objectively identified as a candidate for PrEP were willing and self-identified as a PrEP candidate, supporting prior research that indicated large discrepancies between objective and subjective HIV risk.69–71 Subsequent drop-offs also occurred through the rest of the motivational PrEP cascade. Interventions that facilitate movement across the cascade and up the ladder toward PrEP uptake are needed. In particular, interventions that increase knowledge of one's candidacy for PrEP are warranted, which could be supported by existing online tools to support objective candidacy such as the “check your PrEP score” feature offered on https://prephere.org and supported by empirical data.72 The promotion of other online tools to identify potential PrEP care providers—such as the geotargeted “PrEP locator” (https://preplocator.org/)73—could also be used to reduce drop-offs from PrEP contemplation to PrEParation. However, these online tools are limited without additional behavioral intervention support to increase willingness and intentions to initiate PrEP, navigating the discussion about PrEP with a health care provider, or maintaining PrEP dosing and HIV/STI testing adherence; a theory-based intervention using motivational interviewing is a plausible intervention modality in need of development and efficacy testing.

The PrEP-DB performed as expected in this sample of GBM, with increasing perceptions of the benefits and decreasing concerns about the consequences of PrEP across the motivational PrEP cascade and PrEP contemplation ladder. As highlighted in Fig. 1, individuals who are in precontemplation compared to contemplation have a reversal in the weighing of health benefits and consequences; perceptions switch from weighing health consequences more heavily in precontemplation to weighing health benefits higher in contemplation. A widening trend then occurs when health benefits are regarded as more important and the perceptions of health consequences decrease along the cascade through PrEParation, action and initiation, and maintenance and adherence. Our cross-sectional findings provide preliminary evidence that GBM weigh their option of whether to initiate PrEP or not more heavily based on an appraisal of health benefits and consequences, compared to social benefits and consequences, and we see this trend continue after uptake with persistence. In general, the magnitude and variation in reported means of social benefits and consequences across stages were smaller compared to health benefits and consequences, further suggesting lesser importance of social factors given the relatively low level of agreement with these items across the cascade. While individually important in our bivariate analyses, the effects of social benefits and consequences were diminished in our fully adjusted multi-variable models. Based on these findings, the PrEP-DB can be used by researchers to measure motivational factors associated with PrEP uptake and persistence across the four domains, particularly health benefits and consequences as the most important. We anticipate utility within motivational interviewing interventions conducted online, wherein a clinician is unable to elicit these barriers and facilitators in the typical one-on-one mode of motivational interviewing, but this PrEP-DB could also be used by clinicians as a starting point because we found these factors to be correlated with PrEP uptake and adherence. Moreover, PrEP uptake and adherence interventions using the information-motivation-behavioral skills model40 could focus on these factors within the motivation construct, and future work should determine how these factors correlate with information and behavioral skills to further support intervention development. Nonetheless, we suggest further research to test how these factors differ by adherence patterns among samples with adherence difficulties given the high level of adherence reported in this sample.

The PrEP contemplation ladder was also a reliable assessment tool for assessing location on the motivational PrEP cascade, suggesting the utility of a brief assessment for use in clinical intervention sessions and research surveys. Regarding location on the motivational PrEP cascade and PrEP contemplation ladder, notable differences were found by age, race/ethnicity, and income. Younger age was associated with higher position on the PrEP cascade and ladder, which adds to a body of evidence measuring PrEP uptake. Specifically, our findings indicate younger men—on average—were closer to PrEP uptake and maintenance compared to their older counterparts, yet prior research has found relatively low rates of PrEP uptake among young GBM19,20 which could change with PrEP now approved for adolescents.21 However, we did observe lower locations on the PrEP cascade and ladder for black men, supporting additional evidence of a disparity in PrEP uptake between white and black GBM.19,22,74,75 Black GBM are in need of additional intervention to support PrEP uptake, particularly because black GBM already have higher agreement in the health benefits of PrEP, yet this has not translated to a higher position on the PrEP cascade and ladder. Interventions to remove structural barriers to PrEP (e.g., increasing access to health care)76 are important because structural barriers are often outside the control of the individual. Health insurance is one noteworthy structural barrier tied to income, which can make obtaining a PrEP prescription and adhering to the ongoing maintenance activities challenging.76 Health care access barriers are indirectly supported by our findings based on PrEP cascade and ladder location by income; however, a structural intervention aimed at minimizing the financial burdens of PrEP was insufficient in substantially increasing PrEP uptake among young black GBM,20 indicating the need for combined strategies that remove structural barriers, while targeting health behavior theory constructs, including the PrEP-DB factors identified in our results. Specifically, intervention approaches combined with structural interventions are needed to move individuals from willing to initiating PrEP uptake by enhancing positive perceptions related to the health benefits of PrEP and reducing concerns about health consequences, which could be targeted through motivational interviewing or other theory-based interventions aimed at enhancing personal motivation for PrEP uptake and sustained adherence to follow-up maintenance care and PrEP dosing strategy. Nonetheless, further research is needed to identify the potential of various intervention strategies to increase PrEP uptake with adequate adherence and evaluated for intervention effects by race/ethnicity to ensure our PrEP response does not inadvertently exacerbate health disparities in PrEP use by race/ethnicity.

Our data highlight the need for researchers and practitioners to remain attuned to assisting GBM who initiate PrEP to maintain adequate adherence for HIV protection and engagement in quarterly HIV/STI screening. PrEP adherence was generally high in this sample, with only 6.9% (n = 10) missing 4 days or more of PrEP in a row, yet additional efforts are needed to reduce this further until long-acting dosing formulas become available.63,65,77 Maintaining quarterly HIV/STI screening practices is important for reducing missed bacterial infections,78 particularly with evidence of increasing STIs among PrEP users associated with decreasing condom use,79,80 and identifying acute HIV infections among those with adherence barriers. We found that many individuals who initiate PrEP have difficulty maintaining quarterly testing visits, which is supported by findings from a clinic in Chicago where only 15% of patients were able to adhere to four-out-of-four quarterly visits by the 12-month follow-up assessment,81 and PrEP discontinuation was common.82,83 Extending PrEP maintenance care outside of the clinic could be one avenue to increase PrEP persistence. Interest in home-based PrEP was high in this nationwide cohort of GBM, where 72.3% preferred a home-based PrEP program with at-home HIV/STI testing maintenance care to the standard clinic-based follow-ups,84 and additional work has identified the feasibility of this type of home-based PrEP maintenance care program.85

Limitations

Our findings should be understood in light of their limitations. First, we made preliminary assessments about the validity of the PrEP-DB based on cross-sectional data. Further research is needed to assess longitudinal behavior change based on changes in the PrEP-DB, motivational PrEP cascade, and PrEP contemplation ladder to increase the rigor of our findings. Second, we relied on the self-report of PrEP adherence, which could overreport actual adherence86; our findings may underestimate the number of individuals who would benefit from a PrEP adherence intervention. Nonetheless, we report data from a large, nationwide sample of GBM, which increases the generalizability of our findings in the United States. Finally, the One Thousand Strong cohort is a relatively high socioeconomic status group of men, despite its nationwide representation. The higher level of education, employment, and income of our sample could have influenced final factors retained in our PrEP-DB, particularly our item related to cost/insurance (i.e., “I don't know how to get the costs of PrEP covered”), which has been noted as a barrier for patients to use PrEP51,53,55,69,82,87 and for providers to prescribe it.88

In summary, the PrEP-DB performed well, indicating differences in the four construct scores across the PrEP cascade for health benefits, health consequences, social benefits, and social consequences. Ladder scores also increased across the PrEP cascade, and health benefits and health consequences were more strongly associated with PrEP ladder location than social benefits and consequences in the fully adjusted regression model. The PrEP-DB and ladder were reliable measures with preliminary indications of validity, providing brief assessment tools useful for PrEP uptake and persistence interventions. Complementing tools to determine PrEP candidacy, researchers and practitioners are now equipped to promote and evaluate PrEP uptake and persistence.

Acknowledgments

One Thousand Strong study was funded by a research grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA036466; MPIs: Parsons & Grov). H. Jonathon Rendina was supported by a Career Development Award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01-DA039030). Additional author support was provided from the National Institute of Mental Health (P30-MH052776, PI: Kelly). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the other members of the One Thousand Strong Study Team (Ana Ventuneac, Demetria Cain, Mark Pawson, Ruben Jimenez, Scott Jones, Brett Millar, Raymond Moody, and Thomas Whitfield) and other staff from the Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies and Training (Chris Hietikko, Andrew Cortopassi, Brian Salfas, Doug Keeler, and Carlos Ponton). We would also like to thank the staff at Community Marketing, Inc. (David Paisley, Heather Torch, and Thomas Roth). Finally, we thank Jeffrey Schulden at NIDA, the anonymous reviewers of this article, and all of our participants in the One Thousand Strong study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. CDC. HIV surveillance report, 2016, vol. 28. 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf (Last accessed January11, 2018)

- 2. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:399–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:2083–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2587–2599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2015;372:509–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2012;367:423–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:411–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. USFDA. FDA approves first medication to reduce HIV risk. 2012. Available at: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170406045106/https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm311821.htm (Last accessed September6, 2018)

- 10. Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: A cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:820–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoagland B, Moreira RI, De Boni RB, et al. High pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and early adherence among men who have sex with men and transgender women at risk for HIV Infection: The PrEP Brasil demonstration project. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20:1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal- and community-based sexual health services. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:75–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): Effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2016;387:53–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:1601–1603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. CDC. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States 2014. A clinical practice guideline. 2014. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf (Last accessed September6, 2018)

- 16. CDC. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States - 2017. update. A clinical practice guideline. 2018. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf (Last accessed April4, 2018)

- 17. Mera R, McCallister S, Palmer B, Mayer G, Magnuson D, Rawlings K. Truvada (TVD) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the United States (2013–2015). 21st International AIDS Conference, abstract TUAX0105LB; July 18–22, 2016; Durban, Africa [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Lassiter JM, Whitfield TH, Starks TJ, Grov C. Uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74:285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Schneider J, Garofalo R, Fujimoto K. Use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in young men who have sex with men is associated with race, sexual risk behavior and peer network size. AIDS Behav 2017;21:1376–1382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rolle CP, Rosenberg ES, Siegler AJ, et al. Challenges in translating PrEP interest into uptake in an observational study of young Black MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:250–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gilead Sciences, Inc. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves expanded indication for Truvada® (emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) for reducing the risk of acquiring HIV-1 in adolescents. 2018. Available at: www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180515006187/en/U.S.-Food-Drug-Administration-Approves-Expanded-Indication (Last accessed June1, 2018)

- 22. Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, et al. Distribution of active PrEP prescriptions and the PrEP-to-need ratio, US, Q2 2017. 25th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, abstract 1022LB; March 4–7, 2018; Boston, MA [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith DK, Van Handel M, Wolitski RJ, et al. Vital signs: Estimated percentages and numbers of adults with indications for preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1291–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Purcell DW, Johnson CH, Lansky A, et al. Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men in the United States to obtain HIV and syphilis rates. Open AIDS J 2012;6:98–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grov C, D'Angelo AB, Flynn AWP, et al. How do gay and bisexual men make up for missed PrEP doses, and what impact does missing a dose have on their subsequent sexual behavior? AIDS Educ Prev 2018;30:275–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. CDC. Compendium of HIV prevention interventions with evidence of effectiveness. 2018. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/index.html (Last accessed April4, 2018)

- 27. Parsons JT, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Botsko M, Golub SA. A randomized controlled trial utilizing motivational interviewing to reduce HIV risk and drug use in young gay and bisexual men. J Consult Clin Psychol 2014;82:9–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parsons JT, Golub SA, Rosof E, Holder C. Motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral intervention to improve HIV medication adherence among hazardous drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;46:443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Naar-King S, Parsons JT, Johnson AM. Motivational interviewing targeting risk reduction for people with HIV: A systematic review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2012;9:335–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen X, Murphy DA, Naar-King S, et al. A clinic-based motivational intervention improves condom use among subgroups of youth living with HIV. J Adolesc Health 2011;49:193–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Murphy DA, Chen X, Naar-King S, Parson JT, for the Adolescent Trials Network. Alcohol and marijuana use outcomes in the Healthy Choices motivational interviewing intervention for HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2012;26:95–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parsons JT, John SA, Millar BM, Starks TJ. Testing the efficacy of combined motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral skills training to reduce methamphetamine use and improve HIV medication adherence among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 2018;22:2674–2686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Starks TJ, Millar BM, Lassiter JM, Parsons JT. Preintervention profiles of information, motivational, and behavioral self-efficacy for methamphetamine use and HIV medication adherence among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:78–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Naar-King S, Outlaw AY, Sarr M, et al. Motivational Enhancement System for Adherence (MESA): Pilot randomized trial of a brief computer-delivered prevention intervention for youth initiating antiretroviral treatment. J Pediatr Psychol 2013;38:638–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Outlaw AY, Naar-King S, Tanney M, et al. The initial feasibility of a computer-based motivational intervention for adherence for youth newly recommended to start antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Care 2014;26:130–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Pachankis JE, Gamarel KE, Surace A, Golub SA, Parsons JT. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a live-chat social media intervention to reduce HIV risk among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2015;19:1214–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Naar-King S, Outlaw A, Green-Jones M, Wright K, Parsons JT. Motivational interviewing by peer outreach workers: A pilot randomized clinical trial to retain adolescents and young adults in HIV care. AIDS Care 2009;21:868–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Outlaw AY, Naar-King S, Parsons JT, Green-Jones M, Janisse H, Secord E. Using motivational interviewing in HIV field outreach with young African American men who have sex with men: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health 2010;100(S1):S146–S151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Brandenburg N. Decisional balance measure for assessing and predicting smoking status. J Pers Soc Psychol 1985;48:1279–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull 1992;111:455–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Horvath KJ, Smolenski D, Amico KR. An empirical test of the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills model of ART adherence in a sample of HIV-positive persons primarily in out-of-HIV-care settings. AIDS Care 2014;26:142–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. John SA, Walsh JL, Weinhardt LS. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills model revisited: A network-perspective structural equation model within a public sexually transmitted infection clinic sample of hazardous alcohol users. AIDS Behav 2017;21:1208–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kalichman SC, Picciano JF, Roffman RA. Motivation to reduce HIV risk behaviors in the context of the Information, Motivation and Behavioral Skills (IMB) model of HIV prevention. J Health Psychol 2008;13:680–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shrestha R, Altice FL, Huedo-Medina TB, Karki P, Copenhaver M. Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): An empirical test of the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model among high-risk drug users in treatment. AIDS Behav 2017;21:1299–1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The Transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997;12:38–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Grov C, Cain D, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Parsons JT. Characteristics associated with urethral and rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia diagnoses in a US national sample of gay and bisexual men: Results from the One Thousand Strong panel. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:165–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Grov C, Cain D, Whitfield TH, et al. Recruiting a U.S. national sample of HIV-negative gay and bisexual men to complete at-home self-administered HIV/STI testing and surveys: Challenges and opportunities. Sex Res Soc Policy 2016;13:1–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Grov C, Whitfield TH, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Parsons JT. Willingness to take PrEP and potential for risk compensation among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 2015;12:2234–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ayala G, Makofane K, Santos GM, et al. Access to basic HIV-related services and PrEP acceptability among men who have sex with men worldwide: Barriers, facilitators, and implications for combination prevention. J Sex Transm Dis 2013;2013:953123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Calabrese SK, Underhill K. How stigma surrounding the use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis undermines prevention and pleasure: A call to destigmatize “truvada whores”. Am J Public Health 2015;105:1960–1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, Charles V. Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2015;29:102–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu AY, Hessol NA, Vittinghoff E, et al. Medication adherence among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV infection in the United States: Implications for pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2014;28:622–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. King HL, Keller SB, Giancola MA, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis accessibility research and evaluation (PrEPARE Study). AIDS Behav 2014;18:1722–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, et al. High interest in preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV infection: Baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;68:439–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kubicek K, Arauz-Cuadra C, Kipke MD. Attitudes and perceptions of biomedical HIV prevention methods: Voices from young men who have sex with men. Archives Sex Behav 2015;44:487–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Smith H, Conway-Washington C, White D, Cherry C. Psychosocial factors related to willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among Black men who have sex with men attending a community event. Sex Health 2014;11:244–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Brooks RA, Landovitz RJ, Regan R, Lee SJ, Allen VC., Jr. Perceptions of and intentions to adopt HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among black men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. Int J STD AIDS 2015;26:1040–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Carlo Hojilla J, Koester KA, Cohen SE, et al. Sexual behavior, risk compensation, and HIV prevention strategies among participants in the San Francisco PrEP Demonstration Project: A qualitative analysis of counseling notes. AIDS Behav 2015;20:1461–1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mantell JE, Sandfort TG, Hoffman S, Guidry JA, Masvawure TB, Cahill S. Knowledge and attitudes about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among sexually active men who have sex with men (MSM) participating in New York City gay pride events. LGBT Health 2014;1:93–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Flash CA, Stone VE, Mitty JA, et al. Perspectives on HIV prevention among urban black women: A potential role for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2014;28:635–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pérez-Figueroa RE, Kapadia F, Barton SC, Eddy JA, Halkitis PN. Acceptability of PrEP uptake among racially/ethnically diverse young men who have sex with men: The P18 study. AIDS Educ Prev 2015;27:112–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gamarel KE, Golub SA. Intimacy motivations and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adoption intentions among HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in romantic relationships. Ann Behav Med 2015;49:177–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. John SA, Whitfield THF, Rendina HJ, Parsons JT, Grov C. Will gay and bisexual men taking oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) switch to long-acting injectable PrEP should it become available? AIDS Behav 2018;22:1184–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Underhill K, Morrow KM, Colleran C, et al. A qualitative study of medical mistrust, perceived discrimination, and risk behavior disclosure to clinicians by U.S. male sex workers and other men who have sex with men: Implications for biomedical HIV prevention. J Urban Health 2015;92:667–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Whitfield TH, Grov C. Familiarity with and preferences for oral and long-acting injectable HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national sample of gay and bisexual men in the US. AIDS Behav 2016;20:1390–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. John SA, Starks TJ, Rendina HJ, Grov C, Parsons JT. Should I convince my partner to go on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? The role of personal and relationship factors on PrEP-related social control among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 2018;22:1239–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rendina HJ, Whitfield TH, Grov C, Starks TJ, Parsons JT. Distinguishing hypothetical willingness from behavioral intentions to initiate HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Findings from a large cohort of gay and bisexual men in the US. Soc Sci Med 2017;172:115–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:151ra125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wilton J, Kain T, Fowler S, et al. Use of an HIV-risk screening tool to identify optimal candidates for PrEP scale-up among men who have sex with men in Toronto, Canada: Disconnect between objective and subjective HIV risk. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:20777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kesler MA, Kaul R, Myers T, et al. Perceived HIV risk, actual sexual HIV risk and willingness to take pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in Toronto, Canada. AIDS Care 2016;28:1378–1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gallagher T, Link L, Ramos M, Bottger E, Aberg J, Daskalakis D. Self-perception of HIV risk and candidacy for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men testing for HIV at commercial sex venues in New York City. LGBT Health 2014;1:218–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Beymer MR, Weiss RE, Sugar CA, et al. Are Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for preexposure prophylaxis specific enough? Formulation of a personalized HIV risk score for pre-exposure prophylaxis initiation. Sex Transm Dis 2017;44:48–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Siegler AJ, Wirtz S, Weber S, Sullivan PS. Developing a web-based geolocated directory of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis-providing clinics: The PrEP locator protocol and operating procedures. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2017;3:e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hoots BE, Finlayson T, Nerlander L, Paz-Bailey G. Willingness to take, use of, and indications for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men-20 US cities, 2014. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:672–677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mayer KH, Grasso C, Levine K, et al. Increasing PrEP uptake, persistent disparities in at-risk patients in a Boston Center. Paper presented at: 25th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, abstract 1014; March 4–7, 2018; Boston, MA [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kelley CF, Kahle E, Siegler A, et al. Applying a PrEP continuum of care for men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:1590–1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Landovitz RJ, Kofron R, McCauley M. The promise and pitfalls of long-acting injectable agents for HIV prevention. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016;11:122–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Golub SA, Peña S, Boonrai K, Douglas N, Hunt M, Radix A. STI data from community-based PrEP implementation suggest changes to CDC guidelines. Paper presented at: 23rd Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, abstract 869; February 22–25, 2016; Boston, MA [Google Scholar]

- 79. Newcomb ME, Moran K, Feinstein BA, Forscher E, Mustanski B. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use and condomless anal sex: Evidence of risk compensation in a cohort of young men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;77:358–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Beymer MR, DeVost MA, Weiss RE, et al. Does HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis use lead to a higher incidence of sexually transmitted infections? A case-crossover study of men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, California. Sex Transm Infect 2018;94:457–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rusie LK, Orengo C, Burrell D, et al. PrEP Initiation and Retention in care over five years, 2012–2017: Are quarterly visits too much? Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:283–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Whitfield THF, John SA, Rendina HJ, Grov C, Parsons JT. Why I quit pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? A mixed-method study exploring reasons for PrEP discontinuation and potential re-initiation among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 2018. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1007/s10461-018-2045-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shover CL, Javanbakht M, Shoptaw S, Bolan R, Gorbach P. High discontinuation of pre-exposure prophylaxis within six months of initiation. Paper presented at: 25th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, abstract 1009; March 4–7, 2018; Boston, MA [Google Scholar]

- 84. John SA, Rendina HJ, Grov C, Parsons JT. Home-based pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) services for gay and bisexual men: An opportunity to address barriers to PrEP uptake and persistence. PLoS One 2017;12:e0189794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Siegler AJ, Mayer KH, Liu AY, et al. Developing and assessing the feasibility of a home-based PrEP monitoring and support program. Clin Infect Dis 2018. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciy529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Baker Z, Javanbakht M, Mierzwa S, et al. Predictors of over-reporting HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) in self-reported versus biomarker data. AIDS Behav 2018;22:1174–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Marks SJ, Merchant RC, Clark MA, et al. Potential healthcare insurance and provider barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis utilization among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:470–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Krakower DS, Ware NC, Maloney KM, Wilson IB, Wong JB, Mayer KH. Differing experiences with pre-exposure prophylaxis in Boston among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender specialists and generalists in primary care: Implications for scale-up. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]